Towards an Education for a Circular Economy: Mapping Teaching Practices in a Transitional Higher Education System

Abstract

1. Introduction

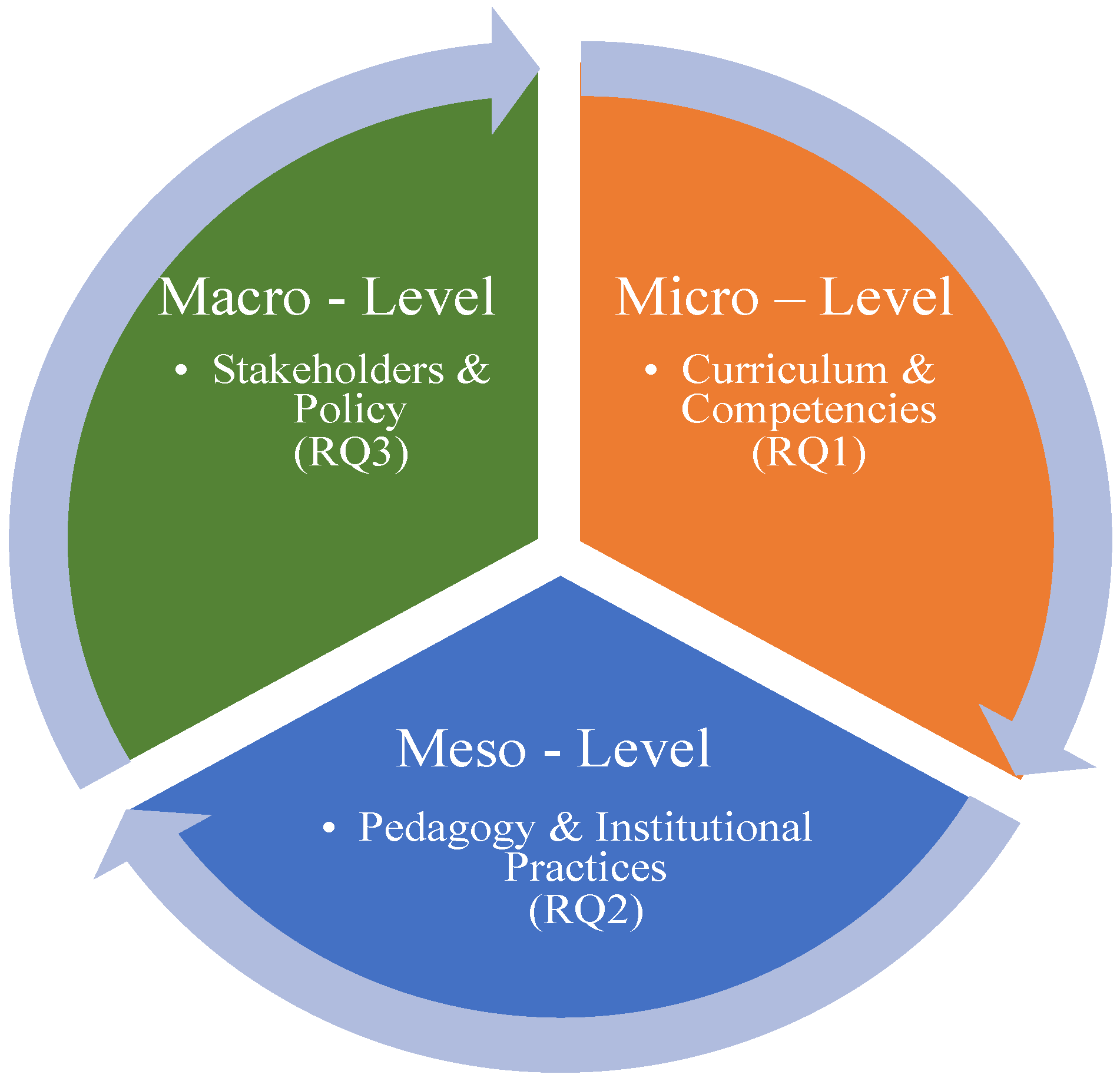

- RQ1. To what extent are CE-related content and competencies incorporated into HEIs’ curriculum?

- RQ2. What teaching and learning approaches are employed to deliver this content?

- RQ3. What challenges and opportunities do educators face in integrating a circular mindset, skills, and attitudes?

2. Study Background

2.1. Conceptual Underpinning of Education for Circular Economy

2.2. ECE: Competencies, Teaching and Learning Approaches, and Challenges

- Resource management and circular design is a group of competencies related to the design of circular products, services, and processes, such as follows: eco-design; design thinking; lifecycle assessment (LCA); circular product design; upcycling; remanufacturing; sustainable product development; closing material loops; waste prevention strategies; system design and innovation; and circular product–service systems.

- Systems thinking competencies needed to comprehend and model systemic interactions and closed-loop industrial systems, such as the following: systems optimization; interdisciplinary thinking; resource flow analysis; resilience thinking; macro-systemic and intersectoral understanding; life-cycle thinking; resilience thinking; and critical systems reflection.

- Business models and entrepreneurship competencies shape and appraise sustainable, circular business opportunities, such as the following: circular business model innovation; strategic planning in circular contexts; business modelling tools; value creation and delivery in circular systems; feasibility analysis; decision-making under sustainability constraints; entrepreneurial opportunity recognition; and financing for circular ventures.

- Collaboration, leadership, and critical thinking are cross-cutting competencies that are essential to lead, contemplate, and move in uncertain sustainability contexts, such as follows: teamwork and collaboration; leadership for sustainability transitions; critical and strategic thinking; ethical reflection and systems ethics; interdisciplinary collaboration; conflict negotiation and facilitation; communication and team leadership; self-direction and adaptive learning; and reflective practice and lifelong learning.

- Active and experiential methods, including teaching and learning approaches by using practical, real-world, reflection, and immersion in context methods, which combine the theoretical part with practical application, such as learning by doing; experiential learning; field trips; studio work; design class; active learning; post-qualitative inquiry; laboratory exercise; and ethnography.

- Simulation-based teaching and learning approaches equip students with comprehensive reflection abilities and skills to connect amongst diverse stakeholders by taking into consideration the macro-level implications of decision-making, which stipulate students’ experimentation under diverse scenarios, understanding systemic complexity, and practicing long-term planning and decision-making in a safe environment, through methods such as follows: gaming; serious gaming; business gaming; scenario building; board games; and tournaments.

- Team-based and collaborative teaching and learning approaches are pivotal in advancing knowledge transfer and dissemination, as students are exposed to integrative and multidisciplinary teams to boost their exposure to a variety of viewpoints and promote in-depth understanding. The teaching and learning approaches for this method are as follows: collaborative learning; project-based learning; challenge-based learning; participatory learning; group discussions; workshops; report writing; and essays; these are mainly implemented to promote co-learning and build up the collaborative perspective that is critical in developing circular practices.

- Co-learning environments and industry cooperation emphasize teaching and learning practices that are frequently held outside of the classroom by interacting with the industry, experts, and real-world settings. Internships, mentoring, industry interviews and engagement, masterclasses, guest speakers, open educational resources, living labs, stakeholder discussion and engagement, excursions, expert panels, exhibitions, and factory tours are among the approaches implemented to connect HEIs with industry.

2.3. Overview of the Albanian Context and the Research Gap

3. Methodology

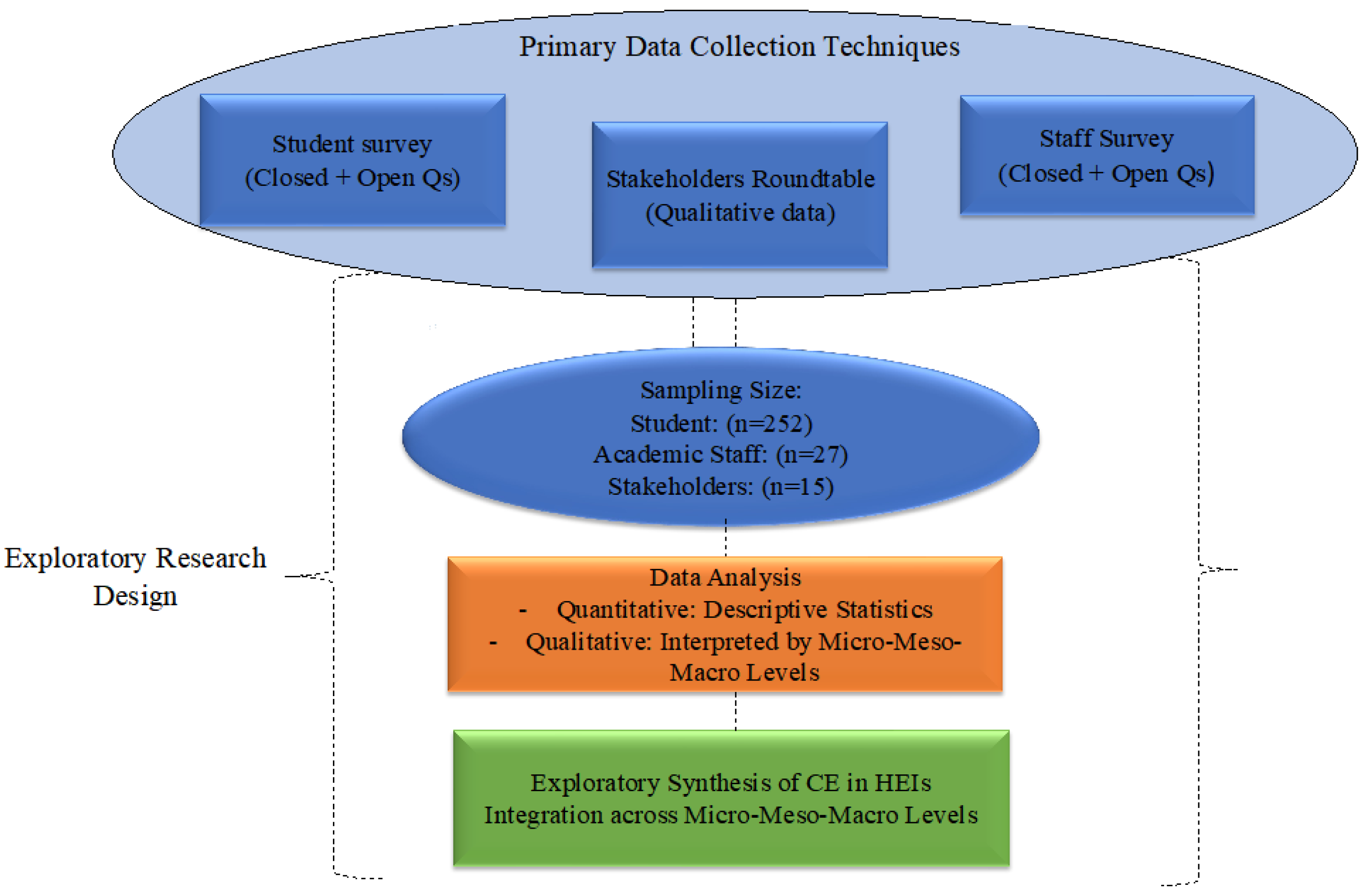

3.1. Research Design and Rationale

3.2. Sampling Strategy

3.3. Data Collection Techniques

3.4. Survey Validation and Reliability

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Findings from Student Responses

4.2. Findings from Academic Staff Responses—Academics’ Practices of ECE

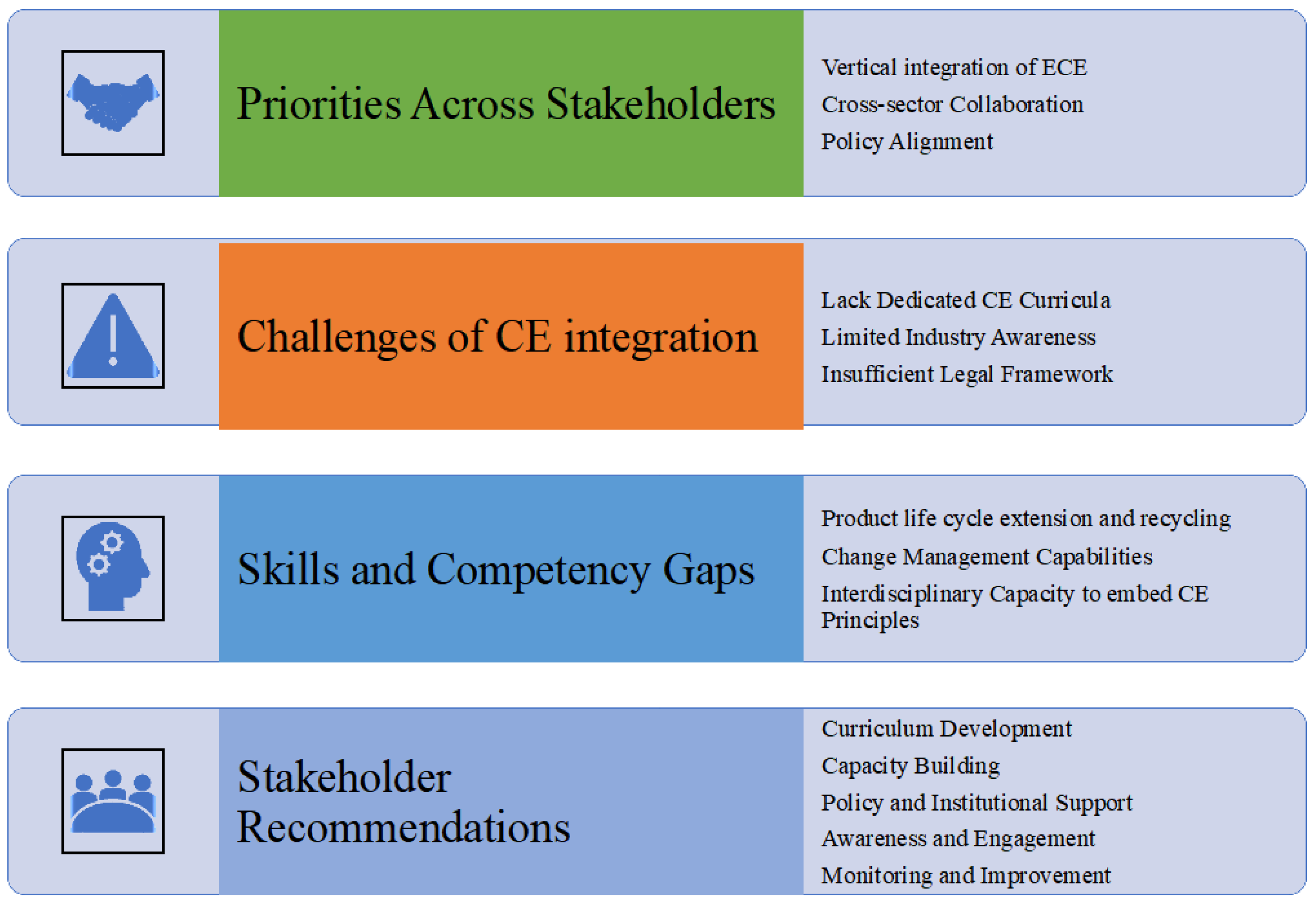

4.3. Results of the Quadruple Helix Synergies for Circular Economy and Sustainability Roundtable

- -

- HEIs lack dedicated CE curricula. CE contentment is mainly provided through initiatives such as workshops or guest lectures, lacking consolidation into formal courses or study programme offerings.

- -

- Industry representatives noted an awareness of CE principles and emphasized the necessity for technological advancement and structural reshaping to support circular business models.

- -

- Vacancy of legal frameworks was recognized from a policy perspective and underlined the necessity of purposeful incentives to encourage HEIs and industry to engage with CE undertakings.

- -

- Resource management and product design competencies, especially needed for product life extension, reuse, and recycling.

- -

- Leadership and management competencies regarding change, which are perceived as crucial for leading organizational and behavioural transformation.

- -

- Multidisciplinary competencies to implement CE principles into non-technical domains, such as law, business, and urban planning.

- -

- Curriculum Development: Establish CE-focused modules and integrate local case studies.

- -

- Capacity Building:

- -

- Policy and Institutional Support:

- -

- Awareness and Engagement:

- -

- Monitoring and Improvement:

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Student Survey on Circular Economy Education

- Gender

- ◦

- Male

- ◦

- Female

- Age: _______

- Level of Studies

- ◦

- Bachelor

- ◦

- Master

- ◦

- PhD

- Study Program: _______

- Year You Started Your Studies: _______

- University Name: _______

- Employment Status

- ◦

- Employed

- ◦

- Unemployed

- ◦

- Self-Employed

- If employed, is your work related to Circular Economy concepts?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No

- Have you heard of the terms “linear economy” and “circular economy” before?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No

- If yes, which of the following best describes your understanding of the circular economy?

- ◦

- A system to minimise waste and maximize resource efficiency

- ◦

- A way to design product for use, recycling, or recovery

- ◦

- An approach to reducing environmental impact by reshaping consumer habits

- ◦

- Other:__________________

- In three words, what do you think the term Circular Economy means? _______

- Have you been exposed to the subject of Circular Economy at your university?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No

- If yes, how effective do you think your education has been helping you understand CE principles?

- ◦

- Very important

- ◦

- Important

- ◦

- Moderately important

- ◦

- Slightly important

- ◦

- Not important at all

- What courses or subjects related to Circular Economy have you attended?

- ◦

- Through course projects/assignments or thesis

- ◦

- Through course projects/assignments or thesis

- ◦

- Case studies and real-world examples

- ◦

- Guest lectures or industry experts

- ◦

- Through extracurricular activities

- ◦

- Through personal interest/research

- ◦

- Other: _______

- How did you first learn about Circular Economy concepts? (select all that apply)

- ◦

- Through university courses

- ◦

- Through course projects/assignments or thesis

- ◦

- Case studies and real-world examples

- ◦

- Guest lectures or industry experts

- ◦

- Through extracurricular activities

- ◦

- Through personal interest/research

- ◦

- Other: _______

- How important is sustainability in your discipline?

- ◦

- Very important

- ◦

- Important

- ◦

- Moderately important

- ◦

- Slightly important

- ◦

- Not important at all

- How do you feel about the inclusion of sustainability topics in your study program?

- ◦

- Very important

- ◦

- Important

- ◦

- Moderately important

- ◦

- Slightly important

- ◦

- Not important at all

- Which of the following sustainable product design principles do you think can be applied in your field? (Mark all that apply)

- ◦

- Design for durability (creating economic systems that ensure long-term value and resilience)

- ◦

- Design for reuse and recycling (developing economic models that support resource reuse and recycling)

- ◦

- Use of sustainable materials (promoting the use of renewable and low-impact resources in economic activities)

- ◦

- Energy efficiency (designing economic systems that reduce energy consumption and promote efficiency)

- ◦

- Minimizing waste in production (creating policies and practices that reduce waste in economic processes)

- ◦

- Modular design (developing flexible and upgradeable economic systems or models)

- ◦

- End-of-life solutions (establishing mechanisms to reintegrate products into the economy after use)

- ◦

- Use of renewable energy sources (integrating clean energy solutions into economic development)

- ◦

- Other (please specify): ___________________________

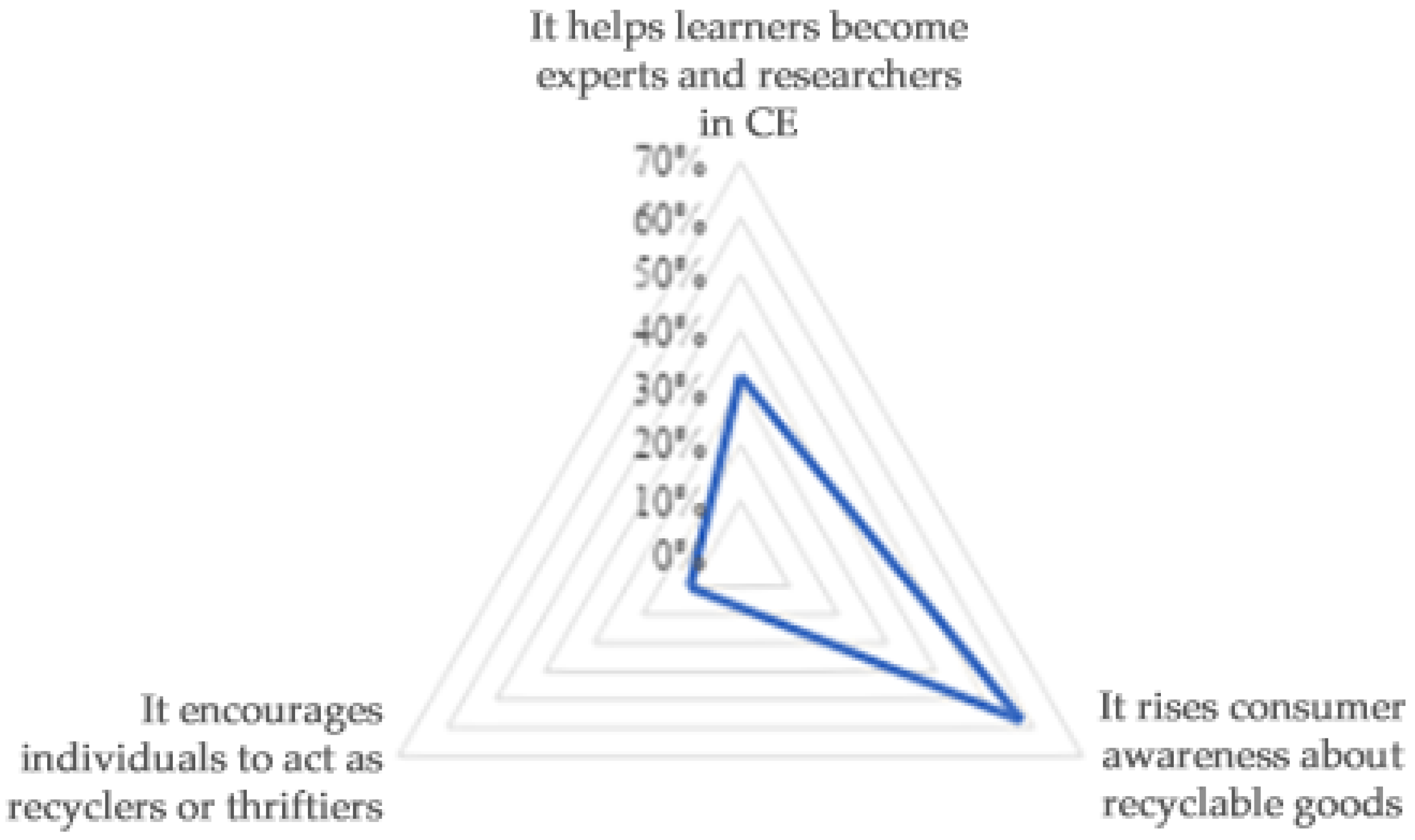

- What role do you believe education plays in promoting the circular economy?

- ◦

- It helps learners become experts and researchers in CE

- ◦

- It rises consumer awareness about recyclable goods

- ◦

- It encourages individuals to act as recyclers or thrifters

- ◦

- Other:________________

- To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements about Circular Economy education at your university?(1 = Totally Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Totally Agree, 6 = I Don’t Know)

- (1)

- Circular Economy education is an integral part of the curriculum.

- (2)

- Circular Economy education is integrated in some of the course syllabuses and projects.

- (3)

- Circular Economy is integrated into extracurricular activities.

- (4)

- Circular Economy is part of the university’s development plan and vision for the future.

- (5)

- Circular Economy topics are inadequately or ineffectively covered in lessons.

- (6)

- Circular Economy is taught in an interdisciplinary or cross-curricular way.

- (7)

- Circular Economy fosters values such as responsibility, stewardship, and resilience.

- (8)

- Circular Economy education encourages collaboration with the local community.

- (9)

- I feel confident in applying Circular Economy concepts to real-world problems.

- In your view, what are the main challenges affecting the teaching of Circular Economy in universities?

- ◦

- Lack of qualified instructors

- ◦

- Insufficient resources and materials

- ◦

- Limited integration into the curriculum

- ◦

- Lack of interdisciplinary approaches

- ◦

- Other: _______

- What systemic changes do you believe are necessary for a circular economy transition?

- ◦

- Better education and awareness campaigns

- ◦

- Improved recycling infrastructure

- ◦

- Stronger policies and regulations

- ◦

- Encouragement of sustainable production by business

- ◦

- Other: __________________

- What improvements would you suggest for better integrating Circular Economy education in universities?----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- Are there any specific tools, resources, or platforms that you think could support the teaching of Circular Economy?----------------------------------------------------------------------

Appendix B. Survey on Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education Curricula

- Name of the institution: _____________________

- Faculty/Department:

- ◦

- Business and Economics

- ◦

- Engineering

- ◦

- Environmental Sciences

- ◦

- Design and Architecture

- ◦

- Social Sciences

- ◦

- Other:____________

- Position:

- ◦

- Professor

- ◦

- Associate Professor

- ◦

- Assistant Professor

- ◦

- Lecturer/Instructor

- ◦

- Other (please specify): ___________

- Years of teaching experience:

- ◦

- Less than 5 years

- ◦

- 5–10 years

- ◦

- More than 10 years

- 5.

- Do you incorporate Circular Economy (CE) topics in your courses?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No (skip to Question 8)

- 6.

- If yes, what are the teaching practices that you implement? (Select all that apply):

- ◦

- Dedicated course on Circular Economy

- ◦

- CE topics integrated into other subjects (e.g., economics, management, engineering)

- ◦

- Case studies related to CE

- ◦

- Projects-based learning approaches to CE

- ◦

- Simulations-based learning approaches to CE

- ◦

- Team-based learning approaches to CE

- ◦

- Graduation Projects or Thesis on CE

- ◦

- Guest speakers from the CE industry or academia

- ◦

- Field trips or practical exposure to CE practices

- ◦

- Other (please specify): ___________

- 7.

- Which Circular Economy topics do you cover in your teaching? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Resource efficiency and waste management

- ◦

- Eco-design and product lifecycle

- ◦

- Recycling and reuse strategies

- ◦

- Business models for a circular economy

- ◦

- Policy and regulation on CE

- ◦

- Circular supply chain management

- ◦

- CE in energy and water use

- ◦

- Other (please specify): ___________

- 8.

- If no, what are the main reasons for not including Circular Economy in your courses? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Lack of expertise or resources

- ◦

- Curriculum restrictions or lack of flexibility

- ◦

- Lack of awareness about the importance of CE

- ◦

- Not relevant to the course content

- ◦

- Other (please specify): ___________

- 9.

- Do you include Environmental Sustainability topics in your teaching?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No (skip to Question 13)

- 10.

- If yes, in which ways do you integrate Environmental Sustainability into your teaching? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Dedicated course on Environmental Sustainability

- ◦

- Sustainability topics integrated into other subjects

- ◦

- Case studies related to sustainability challenges

- ◦

- Assignments or projects focusing on sustainable development

- ◦

- Practical workshops or simulations

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 11.

- Which Environmental Sustainability topics do you cover in your teaching? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Climate change and its impact

- ◦

- Renewable energy sources

- ◦

- Sustainable consumption and production

- ◦

- Environmental policies and regulations

- ◦

- Biodiversity and ecosystem protection

- ◦

- Carbon footprint reduction

- ◦

- Sustainable urban development

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 12.

- If no, what are the main reasons for not including Environmental Sustainability in your courses? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Lack of expertise or resources

- ◦

- Curriculum restrictions or lack of flexibility

- ◦

- Lack of awareness about the importance of sustainability

- ◦

- Not relevant to the course content

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 13.

- What types of teaching methods do you use to teach Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Lectures

- ◦

- Group discussions or debates

- ◦

- Case studies or real-world examples

- ◦

- Projects and research assignments

- ◦

- Field trips or experiential learning

- ◦

- Guest lectures from experts

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 14.

- Which resources or materials do you use to teach Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Academic textbooks

- ◦

- Research articles and journals

- ◦

- Online courses or MOOCs

- ◦

- Case studies from businesses or organizations

- ◦

- Government reports and policy documents

- ◦

- Videos or multimedia resources

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 15.

- What are the biggest challenges in incorporating Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability into your teaching? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Lack of time or curriculum flexibility

- ◦

- Insufficient teaching materials or resources

- ◦

- Lack of training or expertise

- ◦

- Insufficient institutional support

- ◦

- Limited student interest or engagement

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 16.

- What opportunities do you see for improving the integration of Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability into university curricula? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- More training or professional development for faculty

- ◦

- Increased collaboration with industry or NGOs

- ◦

- Curriculum reform to allow more flexibility

- ◦

- Greater institutional support and incentives

- ◦

- Development of interdisciplinary courses

- ◦

- Use of innovative teaching methods (e.g., simulations, project-based learning

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 17.

- Does your institution support the inclusion of Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability in the curriculum?

- ◦

- Yes

- ◦

- No

- ◦

- Not sure

- 18.

- If yes, how does your institution support these efforts? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Providing funding for research or projects

- ◦

- Offering training or workshops for faculty

- ◦

- Collaborating with industries or external experts

- ◦

- Offering grants or incentives for curriculum development

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 19.

- What additional support would you need to better integrate Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability into your teaching?

- 20.

- How do you assess student learning and engagement with Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability topics? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Exams and quizzes

- ◦

- Research papers or essays

- ◦

- Group projects or presentations

- ◦

- Practical assignments or fieldwork

- ◦

- Student reflection or feedback

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

- 21.

- In your experience, how has the inclusion of Circular Economy and Environmental Sustainability topics impacted students? (Select all that apply)

- ◦

- Increased awareness and understanding of sustainability issues

- ◦

- Encouraged critical thinking and problem-solving skills

- ◦

- Inspired students to pursue sustainability-related careers

- ◦

- Increased student engagement and motivation

- ◦

- Other (please specify):

References

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Pigosso, D.C.; Parida, V. Towards the smart circular economy paradigm: A definition, conceptualization, and research agenda. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugallo-Rodríguez, A.; Vega-Marcote, P. Circular economy, sustainability and teacher training in a higher education institution. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1351–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panait, M.; Hysa, E.; Raimi, L.; Kruja, A.; Rodriguez, A. Guest editorial: Circular economy and entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Opportunities and challenges. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022, 14, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, C.; Hysa, E.; Kruja, A.; Mansi, E. Social innovation, circularity and energy transition for environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices—A comprehensive review. Energies 2022, 15, 9028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop-An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy, Com (2015) 614 Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 2, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Beamond, M.T.; Schmitz, M.; Cordova, M.; Ilieva, M.V.; Zhao, S.; Panina, D. Sustainability in business education: A systematic review and future research agenda. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Caeiro, S. Sustainable development goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.; Nicholson, D.T.; Dunk, R.; Lawler, C.; Carney, M.; Vargas, V.R.; Mottram, S. Enabling change agents for sustainable development: A whole-institution approach to embedding the UN Sustainable Development Goals in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 1333–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Zint, M. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L. Towards an education for the circular economy (ECE): Five teaching principles and a case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalabrino, C.; Navarrete Salvador, A.; Oliva Martínez, J.M. A theoretical framework to address education for sustainability for an earlier transition to a just, low carbon and circular economy. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 735–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D. The circular economy, design thinking and education for sustainability. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hysa, E.; Kruja, A.; Rehman, N.U.; Laurenti, R. Circular economy innovation and environmental sustainability impact on economic growth: An integrated model for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowasch, M. Circular economy, cradle to cradle and zero waste frameworks in teacher education for sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1404–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Skene, K.; Haynes, K. The circular economy: An interdisciplinary exploration of the concept and application in a global context. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Chueca, J.; Molina-García, A.; García-Aranda, C.; Pérez, J.; Rodríguez, E. Understanding sustainability and the circular economy through flipped classroom and challenge-based learning: An innovative experience in engineering education in Spain. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renfors, S.M. Education for the circular economy in higher education: An overview of the current state. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024, 25, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, P.; Sassanelli, C.; Urbinati, A.; Chiaroni, D.; Terzi, S. Assessing relations between Circular Economy and Industry 4.0: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 1662–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halog, A.; Anieke, S. A review of circular economy studies in developed countries and its potential adoption in developing countries. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2021, 1, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Nazzal, M.A.; Darras, B.M.; Deiab, I.M. A comprehensive multi-level circular economy assessment framework. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 700–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndou, V.; Manta, O.; Ndrecaj, V.; Hysa, E. Exploring the Role of Universities in Entrepreneurship Education; MDPI Book: Basel, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Merrill, M.Y.; Sammalisto, K.; Ceulemans, K.; Lozano, F.J. Connecting competences and pedagogical approaches for sustainable development in higher education: A literature review and framework proposal. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, R.; Onggo, B.S.; Corlu, C.G.; Nogal, M.; Juan, A.A. The role of simulation and serious games in teaching concepts on circular economy and sustainable energy. Energies 2021, 14, 1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Campbell, D.F.; Grigoroudis, E. Helix trilogy: The triple, quadruple, and quintuple innovation helices from a theory, policy, and practice set of perspectives. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 2272–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Fadeeva, Z. Competences for sustainable development and sustainability: Significance and challenges for ESD. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoccaro, I.; Ceccarelli, G.; Fraccascia, L. Features of higher education for the circular economy: The case of Italy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, L.; Kuppens, T.; Van Schoubroeck, S. Competences of the professional of the future in the circular economy: Evidence from the case of Limburg, Belgium. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Stavropoulos, S.; Ramkumar, S.; Dufourmont, J.; van Oort, F. The heterogeneous skill-base of circular economy employment. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumter, D.; de Koning, J.; Bakker, C.; Balkenende, R. Key competencies for design in a circular economy: Exploring gaps in design knowledge and skills for a circular economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De las Mercedes Anderson-Seminario, M.; Alvarez-Risco, A. Better students, better companies, better life: Circular learning. In Circular Economy: Impact on Carbon and Water Footprint; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, M.; Järvenpää, E. Social sustainability and continuous learning in the circular economy framework. In Responsible Consumption and Production; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas-Navarro, D.E.; Palma-Mendoza, J.A.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E. Integrating Circular Supply Chains into Experiential Learning: Enhancing Learning Experiences in Higher Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavado-Anguera, S.; Velasco-Quintana, P.J.; Terrón-López, M.J. Project-based learning (PBL) as an Experiential Pedagogical Methodology in Engineering Education: A review of the literature. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergani, F.; Lisco, M.; Sundling, R. Circular economy competencies in Swedish architecture and civil engineering education. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2024; Volume 1389, No. 1; p. 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.C.; Moreira, F.; Leão, C.P.; Carvalho, M.A. Sustainability and circular economy through PBL: Engineering students’ perceptions. In WASTES–Solutions, Treatments and Opportunities II; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 409–415. [Google Scholar]

- Bakırlıoğlu, Y.; Ramirez Galleguillos, M.L.E.; Bensason, I.; Yantaç, A.E.; Coşkun, A. Connecting the dots: Understanding professional development needs of Istanbul’s makers for circular economy. In Proceedings of the 10th Engineering Education for Sustainable Development Conference, Cork, Ireland, 14–16 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, G.M.; Moreira, N.; Bouman, T.; Ometto, A.R.; Van der Werff, E. Towards circular economy for more sustainable apparel consumption: Testing the value-belief-norm theory in Brazil and in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2022, 14, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, J.; Sánchez-Barroso, G.; Zamora-Polo, F.; García-Sanz-Calcedo, J. Application of circular economy techniques for design and development of products through collaborative project-based learning for industrial engineer teaching. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kioupi, V.; Vakhitova, T.V.; Whalen, K.A. Active learning as enabler of sustainability learning outcomes: Capturing the perceptions of learners during a materials education workshop. MRS Energy Sustain. 2022, 9, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Green-washing or best case practices? Using circular economy and Cradle to Cradle case studies in business education. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Exploring posthuman ethics: Opening new spaces for postqualitative inquiry within pedagogies of the circular economy. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 38, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Born, R.; Heimdal, A. Experiences from teaching circular economy concepts to engineering students. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (E&PDE 2022), London, UK, 8–9 September 2022; London South Bank University: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehill, S.; Hayles, C.S.; Jenkins, S.; Taylour, J. Engagement with higher education surface pattern design students as a catalyst for circular economy action. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, M.; Evans, B.; Chen, O.; Chen, A.S.; Vamvakeridou-Lyroudia, L.; Savic, D.A.; Mustafee, N. NEXTGEN: A serious game showcasing circular economy in the urban water cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 391, 136000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Romaguera, V.; Dobson, H.E.; Tomkinson, C.B.; Bland Tomkinson, C. Educating engineers for the circular economy. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Engineering Education for Sustainable Development, Bruges, Belgium, 4–7 September 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Summerton, L.; Clark, J.H.; Hurst, G.A.; Ball, P.D.; Rylott, E.L.; Carslaw, N.; McElroy, C.R. Industry-informed workshops to develop graduate skill sets in the circular economy using systems thinking. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2959–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandl, A.; Balz, V.; Qu, L.; Furlan, C.; Arciniegas, G.; Hackauf, U. The circular economy concept in design education: Enhancing understanding and innovation by means of situated learning. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whalen, K.A.; Berlin, C.; Ekberg, J.; Barletta, I.; Hammersberg, P. ‘All they do is win’: Lessons learned from use of a serious game for Circular Economy education. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagrasta, F.P.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Circular economy business models for the Tanzanian coffee sector: A teaching case study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manshoven, S.; Gillabel, J. Learning through play: A serious game as a tool to support circular economy education and business model innovation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosta, B.; Memaj, F. Business models for the circular economy–Case of Albania. In Proceedings of the IAI Academic Conference Proceedings, Roma, Italy, 17 September 2019; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxha, G. Albania between a Circular Development and Activism. In Proceedings of the Circular Economy, International Conference “Circular Economy: Opportunities and Challenges”, Tirana, Albania, 17–18 November 2022; Central European Initiative (CEI): Trieste, Italy, 2022. ISBN 978-606-533-587-5. [Google Scholar]

- Kruja, A.D.; Bedo, N. Building circular economy business models in Albania: What can further be improved. In Proceedings of the XVIII. IBANESS Congress Series on Economics, Business and Management, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 26–27 November 2022; pp. 665–672. [Google Scholar]

- Çerpja, T.; Kola, F. The link between public investment strategy and public debt: An empirical assessment. Corp. Bus. Strategy Rev. 2024, 5, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedej, Z.; Beer, L.; Dushku, E.; Dykmann, S.; Eckelmann, J.; Hysi, A.; Mariaux, L.; Xhebexhia, E. Fostering Potentials of Circular Economy in Albania; Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hoda, O.; Angjeli, G. Navigating sustainable development: Albania’s path to green, circular and blue economies. In IAI Academic Conference Proceedings, Vienna, Austria, 21 June 2024; International Academic Institute: Moscow, Russia, 2024; ISSN 2671-3179. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. A Roadmap towards Circular Economy of Albania. 2024. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/a-roadmap-towards-circular-economy-of-albania_8c970fdc-en/full-report.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bici, A.; Kasimati, M. Tirana Universities Innovative Approach towards Environmental Sustainability. In Proceedings of the Circular Economy, International Conference “Circular Economy: Opportunities and Challenges”, Tirana, Albania, 17–18 November 2022; Central European Initiative (CEI): Trieste, Italy, 2022. ISBN 978-606-533-587-5. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Municipal Waste Management in Western Balkan Countries-Albania, EEA, Denmark. 2021. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/themes/waste/waste-management/municipal-waste-management-country/albania-municipal-waste-factsheet-2021 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Revisiting mixed methods research designs twenty years later. Handb. Mix. Methods Res. Des. 2023, 1, 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Azorín, J.F.; Fetters, M.D. Mixed Methods Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Ormazabal, M.; Jaca, C.; Viles, E. Key elements in assessing circular economy implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Ormazabal, M. Towards a consensus on the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 179, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nano, X.; Mulaj, D.; Kripa, D.; Duraj, B. Entrepreneurial Education and Sustainability: Opportunities and Challenges for Universities in Albania. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Educational Research Association. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research; British Educational Research Association: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The Circular Economy in Cities and Regions: Synthesis Report; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chertow, M.R. Uncovering industrial symbiosis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, J.A.; Tan, H. Circular economy: Lessons from China. Nature 2016, 531, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J. The Effects of an Integrated Curriculum with Embedded Sustainability Themes on Teaching and Learning Experiences at a Primary School; St. John’s University: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Circular Economy Action Plan: For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Competency | Key Elements | Description | Teaching and Learning Approaches | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Management and Circular Design | Eco-design, design thinking, LCA, upcycling, remanufacturing, sustainable product development, closing material loops, and waste elimination. | Focus on sustainable product development, material flow optimization, recycling, and resource efficiency. | Project-based learning, experiential learning, design class, studio work, workshops, serious gaming, simulation, and field trips. | [16,18,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Systems Thinking | Systems optimization, life-cycle thinking, resilience thinking, complexity and interconnectedness, and critical systems reflection. | Understanding interrelations in material, energy, and waste systems; decision-making based on system-wide perspectives. | Simulation-based learning, scenario building, participatory learning, flipped classroom, and collaborative and challenge-based learning. | [11,26,34,47,48,49,50,51] |

| Business Models and Entrepreneurship | Circular business models, supply chain and value chain innovation, entrepreneurship, market creation, and financial and impact assessment. | Developing competence in designing, implementing, and scaling CE business solutions across industries. | Problem-based learning, business gaming, internships, mentoring, masterclasses, guest speakers, industry engagement, and pitching. | [11,34,39,48,51,52,53] |

| Collaboration, Leadership, and Critical Thinking | Teamwork, leadership, stakeholder engagement, ethical reflection, policy literacy, governance, creativity, problem-solving, and critical thinking. | Fostering collaborative and reflective capacities to lead transitions and engage diverse stakeholders in CE contexts. | Collaborative learning, ethnography, expert panels, report writing, essays, panel debates, stakeholder engagement, living labs, and excursions. | [11,18,41,44,47,48,49,50] |

| Category | Subcategory | Frequency (n = 252) | Percentage % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 81 | 32.1% |

| Female | 171 | 67.9% | |

| Age Group | <20 | 21 | 8.3% |

| 20–21 | 190 | 75.3% | |

| 22+ | 41 | 16.3% | |

| Level of studies | Bachelor | 241 | 95.6% |

| Master | 11 | 4.4% | |

| Study Programme | Business Informatics | 186 | 73.8% |

| Business Admin/Marketing | 32 | 12.7% | |

| International Marketing and Logistics | 22 | 8.7% | |

| Software Engineering | 7 | 2.8% | |

| Economics/Banking and Finance | 5 | 3.2% |

| Indicator | Answers | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Exposed to CE at the University | Yes | 57.1% |

| No | 42.9% | |

| Courses or subjects related to Circular Economy attended. | Through university courses | 35.7% |

| Through course projects/assignments or thesis | 13.1% | |

| Case studies and real-world examples | 19.8% | |

| Guest lectures or industry experts | 14.3% | |

| Through extracurricular activities | 4% | |

| Through personal interest/research | 13.1% | |

| Importance of education in helping understanding CE principles | Very important | 14.7% |

| Important | 34.1% | |

| Moderately important | 34.9% | |

| Slightly important | 7.9% | |

| Not at all important | 8.3% | |

| Importance of Sustainability in Field | Very important | 38.9% |

| Important | 40.9% | |

| Moderately important | 17.5% | |

| Slightly important | 2.7% | |

| Not at all important | 0% |

| Attribute | Category | Frequency (N) |

|---|---|---|

| Institution | Private University | 10 |

| Public Universities | 8 | |

| Other | 9 | |

| Faculty/ Discipline | Business and Economics | 21 |

| Engineering | 3 | |

| Social Sciences/Humanities | 3 | |

| Academic Position | Lecturer | 17 |

| Assistant Professor | 7 | |

| Associate Professor | 3 | |

| Teaching Experience | Less than 5 years | 6 |

| 5–10 years | 11 | |

| More than 10 years | 10 |

| Variable | Category/Response | Frequency (N) |

|---|---|---|

| CE Topics Incorporated into Courses | Yes | 10 |

| No | 17 | |

| ES Topics Incorporated Into Courses | Yes | 18 |

| No | 9 | |

| Teaching Practices Implemented | CE topics integrated into other subjects | 8 |

| Case studies related to CE | 7 | |

| Guest speakers from the CE industry or academia | 7 | |

| Graduation Projects or Theses on CE | 4 | |

| Project-based learning approaches to CE | 2 | |

| Team-based learning approaches to CE | 1 | |

| Field trips or practical exposure to CE practices | 1 | |

| Circular Economy Topics Covered | Business models for a circular economy | 7 |

| Recycling and reuse strategies | 4 | |

| Resource efficiency and waste management | 4 | |

| Policy and regulation on CE | 2 | |

| CE in energy and water use | 2 | |

| Eco-design and product lifecycle | 1 | |

| Circular supply chain management | 1 | |

| Assessment Methods | Group projects/presentations | 14 |

| Research papers or essays | 11 | |

| Student reflection/feedback | 11 | |

| Exams and quizzes | 6 | |

| Practical assignments/fieldwork | 6 | |

| Teaching Resources Used | Research articles and journals | 14 |

| Case studies from industry | 14 | |

| Academic textbooks | 9 | |

| Government policy documents, reports | 6 | |

| Videos or multimedia resources | 8 | |

| Online courses or MOOCs | 2 | |

| Main Barriers to Integration | Lack of time/curriculum flexibility | 16 |

| Insufficient teaching materials or resources | 13 | |

| Lack of expertise or training | 11 | |

| Curriculum restrictions/irrelevance | 14 | |

| Limited student interest | 9 | |

| Insufficient institutional support | 3 | |

| Opportunities for Improvement | Training for faculty | 17 |

| Development of interdisciplinary courses | 17 | |

| Collaboration with industry or NGOs | 15 | |

| Use of innovative teaching methods | 14 | |

| Curriculum reform to allow more flexibility | 11 | |

| Greater institutional support and incentives | 10 | |

| Institutional Support | Yes | 14 |

| No | 1 | |

| Not sure | 12 |

| Category | Institutional Input | Challenges/Barriers | Opportunities for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Courses and Modules | Mainly integrated as part of other courses. | Lack of dedicated modules, rigid curricula, and limited staff expertise. | Develop new elective or core CE courses; co-design interdisciplinary modules. |

| Teaching Methods | Academics mostly use case studies, guest speakers, graduation projects, or theses as main teaching methods for CE. | Insufficient teaching materials or resources. | Diversify approaches and develop more accessible teaching materials and resources. |

| Capacity Building for Staff | Academics reported a lack of training and expertise as a barrier. | Limited professional development opportunities. | Develop CE-specific staff training programmes, possibly through EU projects. |

| Institutional Support and Policy | Weak or unclear support is perceived by staff. | Absence of explicit strategic frameworks. | Develop CE and sustainability strategy; allocate funding; create a sustainability hub. |

| Impact Assessment | Not practiced systematically; no formal assessment reported by staff. | Lack of metrics and evaluation frameworks. | Develop CE learning outcome assessment tools; track student interest in green careers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kruja, A.; Ndrecaj, V.; Çela, A.; Morina, F.; Hysa, E. Towards an Education for a Circular Economy: Mapping Teaching Practices in a Transitional Higher Education System. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219787

Kruja A, Ndrecaj V, Çela A, Morina F, Hysa E. Towards an Education for a Circular Economy: Mapping Teaching Practices in a Transitional Higher Education System. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219787

Chicago/Turabian StyleKruja, Alba, Vera Ndrecaj, Arjona Çela, Fatbardha Morina, and Eglantina Hysa. 2025. "Towards an Education for a Circular Economy: Mapping Teaching Practices in a Transitional Higher Education System" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219787

APA StyleKruja, A., Ndrecaj, V., Çela, A., Morina, F., & Hysa, E. (2025). Towards an Education for a Circular Economy: Mapping Teaching Practices in a Transitional Higher Education System. Sustainability, 17(21), 9787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219787