Abstract

This research examines the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and perceived financial performance (FP) in the Saudi Arabian banking industry using the mediating variables of employee engagement (EE) and green creativity (GC). This study is based on the Social Identity Theory and considers CSR as an engine to produce ethical and social results and promote environmental innovation and sustainable competitiveness. According to a survey of 650 banking employees and structural equation modeling (SEM), the results show that CSR significantly and positively affects EE, GC, and FP, with EE having the strongest mediating role. These conclusions highlight the strategic consequence of CSR in advancing sustainability by balancing financial performance, employee welfare, and environmental innovation. This study adds value to the existing body of research because it provides information on the CSR-FP relationship in a developing economy, where such information is scarcely available. Consistent with the definition of sustainability, this study indicates how CSR activities combine social, environmental, and economic aspects to foster long-term organizational sustainability and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives help banks sustain a good reputation by portraying their responsibility to social and environmental issues [1]. The implementation of CSR principles minimizes the reputational risk associated with unethical conduct and environmental failures [2], and it improves resilience through ethical behavior [3]. CSR also enhances the workplace by increasing employees’ morale, motivation, and engagement [4]. Employees are involved in enhancing productivity and performance, leading to improved financial results [5]. Furthermore, Imran et al. (2022) [5] claimed that CSR stimulates banks to be creative and to embrace sustainable operations. These developments could result in cost savings and efficiency improvements, which would positively affect financial performance.

The link between CSR and perceived financial performance is discussed comprehensively [6]. CSR is the corporation’s obligation for stakeholders, the community, and sustainable development to address environmental and social concerns [7]. CSR practices are crucial for business survival and offer strategic benefits [1]. Research on the CSR–perceived financial performance relationship has yielded inconsistent results. Some studies indicate a positive relationship [8,9], while others report negative or insignificant findings [10,11]. The impacts of CSR on performance have been proposed to be context dependent [2,6]. Based on the context-dependent nature of CSR and the different expectations of society, academics propose that the CSR–performance relationship should be investigated [12,13]. Most CSR analyses have centered on Western economies, and minimal evidence has been found for underdeveloped economies, leading to the question of the relevance of this relationship [14,15].

Given these inconsistent results, academics suggest that mediation mechanisms might justify the connection between CSR and perceived financial performance better [12,15]. CSR requires procedures to convey its impact on performance outcomes—a factor overlooked in earlier studies that potentially leads to skewed conclusions [14,16,17]. Employee engagement (EE) refers to employees’ emotional and cognitive bonds with their work and organization, which influence their involvement and performance [18]. The financial performance of Saudi Arabia’s banking industry faces serious challenges. Such problems are linked to the reduced performance of employees, which consequently affects the industrial stability and overall economy of Saudi Arabia [19]. An increased level of employee participation may result in increased operational expenses, loss of morale, and reduction in productivity, thus undermining the level of customer service [20]. Poor employee engagement in banking institutions is harmful in terms of profitability, erosion of customer faith, and loss of efficiency within organizations [21]. In contrast, staff-based corporate social responsibility would tend to increase employee engagement and loyalty, which is beneficial to banks. These dynamics affect profitability and competitive positioning [22]. It follows that this is important when trying to inculcate these qualities in employees. However, it cannot be said that all banking employees are highly engaged, and only 50 per cent of workers are not at risk of loss. Employers with attentive employees record reduced levels of staff turnover, which could affect the ability of financial institutions to involve competent employees. The decreased commitment of employees may endanger the bank’s perceived financial performance [22].

An employee’s ability to come up with creative ideas relevant to eco-friendly products, processes, or practices is referred to as Green Creativity (GC) [23]. With increased environmental apprehension and the interdependency between CSR and financial performance, green creativity has become one of the options for dealing with these aspects and improving the performance of firms [14,24]. Green creativity in the banking sector prevails when employees can develop green solutions to various environmental challenges in the operations of a financial institution, such as the development of green financial inventions (e.g., green bonds or green stock portfolios) [25], digitization of operations that will limit paper usage, climate-conscious lending, and encouraging green funding (e.g., loans to renewable energy) [26]. As a result, in a manner in which green creativity is nurtured, banks can build a sense of sustainability into their primary operations and achieve a sense of cost savings, elevated stakeholder confidence, and a sense of financial performance due to increased operational resilience and competitiveness in the market [5]. Furthermore, CSR allows organizations to engage in GC, which makes it appear legitimate in terms of ecology and improves performance [17]. It has been proposed that GC can be used to evaluate the correlation between CSR and outcome variables [12,14]. Therefore, it is worthwhile investigating the role of GC in the CSR–perceived financial performance relationship. Nevertheless, the theory of social responsibility contributes to sustainable development [27]. However, the effect of CSR applies on GC has not been studied extensively [14]. Dynamic capabilities in complex environments contribute to business learning about CSR practices and making goods that meet consumer demands [15], which results in financial performance. Following social identity theory (SIT), GCs integrate resources for environmental preservation [28]. Promoting EE and GC provides management and structural theories. The indirect influence of EE and GC on CSR and perceived financial performance (FP) connections merits exploration because of limited research.

Studies have examined the variables that affect the Saudi banking system. The factors affecting employee performance include rewards, motivation, stress, burnout, internal marketing, HR strategies, job satisfaction, and emotional intelligence [29,30]. Limited research exists on the association between EE and GC as mediators in the link between CSR and FP [31]. This study proposes using EE and GC as mediators to understand the relationship between CSR and FP because investigation on their mediating roles is limited. The mediating roles of EE and GC on CSR and FP in the Saudi Arabian banking industry remain unclear. Understanding the theoretical and practical aspects of the CSR-FP connection and its influencing factors such as EE and GC is essential. This raises the primary research question.

- (1)

- Does CSR influence EE, GC, and FP?

- (2)

- Does EE influence FP?

- (3)

- Does GC influence FP?

- (4)

- Do EE and GC mediate the relationship between CSR and FP?

Data from 650 banking employees in Saudi Arabia were collected to address these questions, and structural equation modelling was conducted. The outcome of this research contributes to literature in three respects. First, it answers the call for research on the necessity of further research on CSR in developing economies [15,16] and the chains of CSR effects on financial performance [6,11]. This study determined that CSR practices, either directly or indirectly, through EE and GC, enhance the perceived financial performance of Saudi Arabian banks. First, attracting on the social identity theory, our conclusions propose that CSR practices enhance FP by fostering employee and stakeholder identification with an organization’s socially responsible values. This identification promotes sustainable behaviors, such as green creativity and employee engagement, which contribute to reduced environmental degradation and carbon emissions. Consequently, these efforts help banks comply with emerging environmental regulations, such as those under the Saudi Green Initiative and voluntary carbon crediting schemes, thereby mitigating potential compliance costs and achieving improved financial outcomes through enhanced operational efficiency and stakeholder trust. Second, this study surveyed the intervening influences of EE and GC on the connection between CSR and FP. This result not only contributes to the development of SIT by proposing smart utilization of resources to achieve improved environmental results [32] but also offers a paradigm tying CSR to EE and GC by augmenting firm capabilities. Finally, the study established that CSR can positively affect the connection between EE and FP, which offers a clue as to the influence of CSR, EE, GC, and perceived environmental volatility on firms perceived financial performance.

The article is organized as follows for the rest of its content: Section 2 examines the literature, and Section 3 details the research methodology, including the samples and techniques. Section 4 focuses on analyzing and interpreting the research results, Section 5 discusses the hypothesis testing outcomes and Section 6 discusses the theoretical and managerial implications and concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Underpinning Theory

Social Identity Theory (SIT), created in 1979, presents a psychological explanation for how the self-perception of individuals is influenced by belonging to a group [33]. The impacts of CSR on organizational commitment, EE, and perceived financial performance are often studied using SIT [34,35]. According to this theory, people acquire part of their identity because they belong to groups such as their workplace, which guides their behavior and choice of decisions [36]. When employees feel that their organization is socially accountable, they are expected to recognize with the company. With this recognition, increased degrees of involvement, inspiration, and achievement ensue, contributing to the eventual prosperity of the organization financially [37].

Boundary Conditions and Vision 2030 Alignment in the CSR–FP Relationship

Although prior investigations have supported the understanding of the impacts of CSR and FP in terms of moderating effects, including EE and GC [38,39,40,41], little focus has been placed on considering the contextual boundaries within which these relationships are applicable, especially in the banking industry. This study advances this line of research by theorizing and operationalizing a group of borderline restrictions that determine the association involving CSR and FP in the Saudi Arabian banking sector. The industry is characterized by an effusive institutional landscape characterized by regulatory intensity [42], Shariah-compliance construction [43], disparities in bank size and capitalization, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) exposure [44]. Such contextual elements not only define the visibility and legitimacy of CSR practices but also the level of internalization and responsiveness of employees to practice through engagement and creativity [38,39].

Based on Social Identity Theory (SIT), which holds that organizational classification is empowered through the presence of visible, legitimate, and socially expected values [45], we hold that the CSR-FP relationship is subject to the above speculative boundary features of banking. When the regulated environment is very high, as in Saudi Arabia, as establish via Saudi Central Bank (SAMA) and the Capital Market Authority, CSR compliance is no longer symbolic but decides the strategy [46]. Regulatory intensity amplifies the significance of CSR initiatives, which enables employees to perceive them as believable and institutionally endorsed, strengthening engagement and commitment [47]. In Shariah-compliant banks, ethical behavior and social responsibility are part and parcel of financial legitimacy; hence, CSR acquires even greater moral power, which enhances the connection between CSR and green creativity [48]. Employees do not regard CSR as merely discretionary but as a religious and social responsibility, and this further identification with the organizational environmental and social mission [4]. Furthermore, bank size and capitalization serve as facilitators of CSR performance: the more significant and well-capitalized a bank is, the more slack resources it has to invest in sustainability initiatives, green technologies, and employee-led innovation that will contribute to the indirect influence of CSR on FP [49,50,51]. In the same vein, banks that are well exposed to ESG attract more scrutiny from stakeholders, and this is a motivating factor in translating CSR principles into high-impact practices [26].

Notably, the reflectivity of such dynamics aligns with the national strategies of Saudi Arabia, particularly Vision 2030, which includes the use of sustainable finance, green innovation, and human capital development as the pillars of national change [52]. CSR is a channel through which banks internalize and implement the priorities of Vision 2030 that places sustainability metrics in lending portfolios, a workforce dedicated to the achievement of environmental and social objectives, and the development of green financial instruments, including sustainable lending, green sukuk, and carbon credit arrangements [53]. Consequently, by linking firm-level CSR behavior to these macro policy-level objectives, this study will put CSR not as a moral or reputational activity, but as a strategic tool that helps in supporting the Vision 2030 agenda. Thus, it transcends existing CSR-FP moderation research by offering a theoretical and institutional context-sensitive framework that embodies the contingent and institutionally permeated nature of CSR outcomes in the Saudi banking business.

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Engagement

Recent study has emphasized the effects of CSR activities on EE [54]. Ali et al. (2020) [16] demonstrated that employees’ involvement in CSR has a significant impact on engagement, because it enhances organizational aspects. Studies show that employee pride and commitment as well as job satisfaction improve when CSR facilitates perceived company ethics [55]. This association is in harmony with social identity theory (SIT), according to which people define themselves based on their membership in social groups. Employees, when embracing an organization, identify with the organization when they have common values; hence, their engagement increases [45,55]. Commitment is enhanced by rate comparison between workforce and the organization’s CSR [35]. CSR programs build loyalty, improve employee attitudes, and increase productivity [56]. CSR and employee outcomes have a positive relationship that is more significant in terms of psychological and emotional reactions than job behaviors [33]. Value congruence mediates the interaction between CSR and EE, and internal CSR practices further increase its impact [29]. Bouraoui et al. (2019) [35] show that well-being and community-based CSR programs develop a positive culture and engage in better engagement. This engagement improves individual performance and organizational success as employees engage more actively and identify with company ideals. Kaul (2024) [57] analyzed the employee engagement strategies of the Bhilai Steel Plant and CSR. This study indicates that employee participation increases when employees recognize the alignment between their values and those of the firm, especially in internal CSR projects. Research shows that effective engagement techniques improve CSR outcomes by cultivating ownership and commitment. Therefore, established on social identity theory, we suggest the subsequent hypotheses:

H1.

CSR is positively and substantially associated to EE in the Saudi banking industry.

2.3. Employee Engagement and Financial Performance

Employee engagement (EE) within organizations primarily aims to enhance performance [58,59]. Recently, EE has gained prominence in human resource research because of its links with employee well-being, productivity, and organizational sustainability. Studies have shown that EE boosts job satisfaction, commitment and performance [60]. This connection can be explained through SIT, which suggests that people develop part of their self-concept from participation in social clusters, involving organizations [45]. When employees classify with their corporation, particularly when sharing their values, they experience pride, commitment, and belonging [45]. This identification encourages intrinsic motivation, which is a key factor for driving engagement and performance [34]. Employees who are engaged in and see an alignment between their values and the organization’s mission are more likely to put in discretionary effort, innovate, and support their strategic goals. Therefore, organizational identification, a core element of SIT, is a psychological mechanism that links EE to improved organizational outcomes [55]. Employees who identify with their company internalize the organization’s goals on their own, enhancing overall financial performance. Consequently, grounded on social identity theory, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H2.

EE is positively and significantly related to FP in the Saudi banking industry.

2.4. Corporate Social Responsibility and Green Creativity

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) represents a company’s dedication to ethical behavior, sustainability, and social welfare [61]. In the banking sector, CSR efforts, such as eco-friendly banking, climate-aware lending, and managing environmental risks, align financial activities with global sustainability goals [51,62]. Green creativity (GC) is a consequence of these endeavors and the capacity of organizations to develop innovative, sustainable solutions that are environmentally friendly. These practices increase reputation, create trust among stakeholders, maintain regulatory compliance, and improve financial performance [63]. The link between CSR and GC is well clarified by the social identity principle, which implies that individuals define themselves in relation to their group associations and embrace their values [45]. Employees and stakeholders are more probable to identify with the group, especially when their behaviors reflect societal values, such as sustainability, when banks promote CSR and environmentally responsible practices [36]. Such a perception of organizational identification increases individuals’ motivation to engage in activities, such as green innovation, and the process is in line with the identity and intentions of the group [64]. In this respect, CSR is a strategic management strategy and symbolic act that promotes an identity that revolves around environmental value [65]. Employees who adopt this identity tend to take green and creative initiatives. In addition, being more affiliated with a CSR-oriented organization will increase dedication to environmental missions by generating innovative solutions to problems. Hence, established on social identity assumption, this study hypothesizes the following.

H3.

CSR has a positive effect on GC in the Saudi banking industry.

2.5. Green Creativity and Financial Performance

Chen et al. (2023) [66] highlights the importance of green creativity in achieving sustainable business performance. According to Przychodzen et al. (2018) [67], creative thinking is the only way to transform ideas into products and services. Adomako and Nguyen (2023) [68] explained that such thinking is enabled by a company’s awareness of the environment and its stakeholders. Ecologically, creativity in relation to the environmental expectations of parties serves as a source of innovative concepts in the domains of green products, service providers, processes, and practices [66]. Green creativity in the banking sphere is reflected in the form of creative and innovative financial services such as green bonds and environmentally friendly loans, online banking services with minimal carbon footprints through paperless transactions, and eco-friendly systems [51]. Green creativity can be used in the Saudi banking sector to stimulate competitive advantage by ensuring sustainability in financing and adhering to regulations in line with the sustainability objectives of Vision 2030, which will increase profitability [49,69]. Therefore, the social identity theory can be applied to interpret the affiliation concerning green creativity and sustainable business implementation. According to the SIT, people identify themselves by group membership, thereby reflecting their values [45]. Accordingly, by associating themselves with an organization that practices environmental responsibility, employees adopt it and create a sense of psychological ownership, which leads to sustainable behavior. Green practices and environmental management systems cannot be implemented without green creativity [66]. According to Imran et al. (2022) [5], green creativity is crucial for pursuing sustainable production, which promotes performance and competitive advantage, resulting in green production and competitive advantage, and consequently improves financial performance. Companies that prioritize green creativity can anticipate more environmental value, increased stakeholder approval, green credit, and investor attraction, and thus, sustainable business performance [70]. Thus, this study hypothesizes the following.

H4.

GC is positively and substantially associated with FP in the Saudi banking industry.

2.6. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance

The relationship between CSR and FP has been extensively studied [9,10]; however, the findings remain inconsistent, necessitating context-specific investigations such as those in the Saudi banking sector. In some studies, a positive CSR-FP relationship has been attributed to indicate that CSR increase in profitability in terms of increased stakeholder trust, greater marketing efficiency, and market competitiveness. For instance, Siueia et al. (2019) [71] found that CSR programs in the banks of sub-Saharan Africa enhance financial performance through customer loyalty and adherence to regulations. Similarly, Galdeano et al. (2019) [72] demonstrated that CSR practices in Bahraini banks positively influence profitability by improving their relationships with stakeholders. However, other researchers found a low or non-significant correlation [10,11]. These inconsistencies can be attributed to differences in CSR practices, FP measurements, or contextual differences in regulatory settings and cultural demands [31]. The correlation between CSR and FP is under-investigated in the Saudi banking sector and there is minimal evidence to offer clarity [50]. Nevertheless, the distinctive situation in Saudi Arabia, with Shari-ah-compliant banking, the focus on meeting the sustainability targets of Vision 2030, and a gradual increase in regulatory attention to the practice of CSR implies a greater possibility of a positive CSR-FP relationship [69]. For example, Alshebami (2021) [73] stated that green banking and responsible lending CSR efforts increase stakeholder trust and are aligned with the national sustainability goals of Saudi Arabia, which may enhance financial performance. In addition, reputational risks can be diminished through CSR practices in Saudi banks, which leads to investor concerns about the environment, thereby promoting long-term profitability [71].

The Social Identity Theory (SIT) provides a theoretical lens to explain this relationship [45]. SIT assumes that people acquire their self-concept as a result of being part of groups, such as being in socially responsible groups [28]. The Saudi banking market is no exception, as CSR initiatives imply ethical and sustainable principles that enhance recognition among stakeholders (e.g., employees, customers, and investors). Through this recognition, the commitment level, level of customer loyalty, and investor confidence are increased, which ultimately have an indirect impact on financial performance [55]. Employees who maintain that their bank is socially responsible would tend to support pro-organizational behaviors such as innovation and engagement, which leads to operational efficiency and profitability [54]. Correspondingly, customers and investors who perceive the CSR values of a bank will be more inclined to stay loyal and supply capital, respectively, thereby increasing FP [51]. Despite the inconsistent results worldwide, the strong performance of the Saudi banking sector (including its orientation to the Vision 2030 and the focus on ethical operations and increasing scrutiny of the ESG) suggests the assumption of a positive CSR-FP relationship. Consequently, we present the following hypothesis:

H5.

CSR is positively and substantially linked to perceived financial performance in the Saudi banking industry.

2.7. The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement and Green Creativity

The key processes by which CSR impacts FP in the banking industry are Employee Engagement (EE) and Green Creativity (GC) [49,73]. According to SIT, CSR creates a sense of identification of employees with the socially responsible values of an organization that increases commitment and innovativeness, which in turn leads to financial outcomes [28,45]. EE is the mediator between CSR-FP and FP relationships, which transforms the impact of CSR-induced organizational identification into enhanced productivity and performance. SIT indicates that staff who recognize their establishment as socially responsible cultivate greater emotional and cognitive attachments, thereby enhancing their engagement [55]. According to Kim et al. (2023) [74], CSR positively affects FP in companies, as it contributes to EE, leading to increased productivity and commitment, lower turnover, and better service quality. In the Saudi banking context, CSR initiatives aligned with Saudi Vision 2030’s sustainability objectives can enhance EE by increasing national goals pride and consequently improving FP through greater operational performance [73]. This is also supported by Farrukh et al. (2020) [75], who indicate that EE can mediate the CSR-FP relationship in manufacturing, which would also be relevant to the banking business, where a direct connection between employee performance, client satisfaction, and profitability would be observed.

Green Creativity (GC) mediates the CSR-FP relationship by allowing the development of innovative, environmentally sustainable solutions that increase competitiveness and efficiency; [23] green banking and other environmentally friendly financial products are CSR-related programs that motivate employees to share innovative ideas that are consistent with environmental objectives [17]. According to SIT, employees belonging to an organization with a CSR-oriented orientation tend to venture into GC because their values are in line with the sustainability mission of the firm [76]. Homayoun et al. (2023) [31] established that green innovation mediates the CSR-FP relationship through cost reduction and appeal to environmentally friendly stakeholders, which is applicable to Saudi banks in the Vision 2030 sustainability agenda. Indeed, in the case of GC in the development of green bonds or in the formulation of paperless processes, this may reduce the cost of operation and increase the market share and, hence, FP [77]. According to Baron and Kenny’s (1986) [78] mediation model, CSR has an influence on EE and GC, which in turn has an effect on FP. These pathways are reinforced by the cultural focus on ethical approaches and regulatory pressure to comply with ESG in Saudi Arabia [30]. Thus, we propose the following:

H6.

EE serves as a mediator between CSR and FP in the banking industry.

H7.

GC mediates the association between CSR and FP in the banking industry.

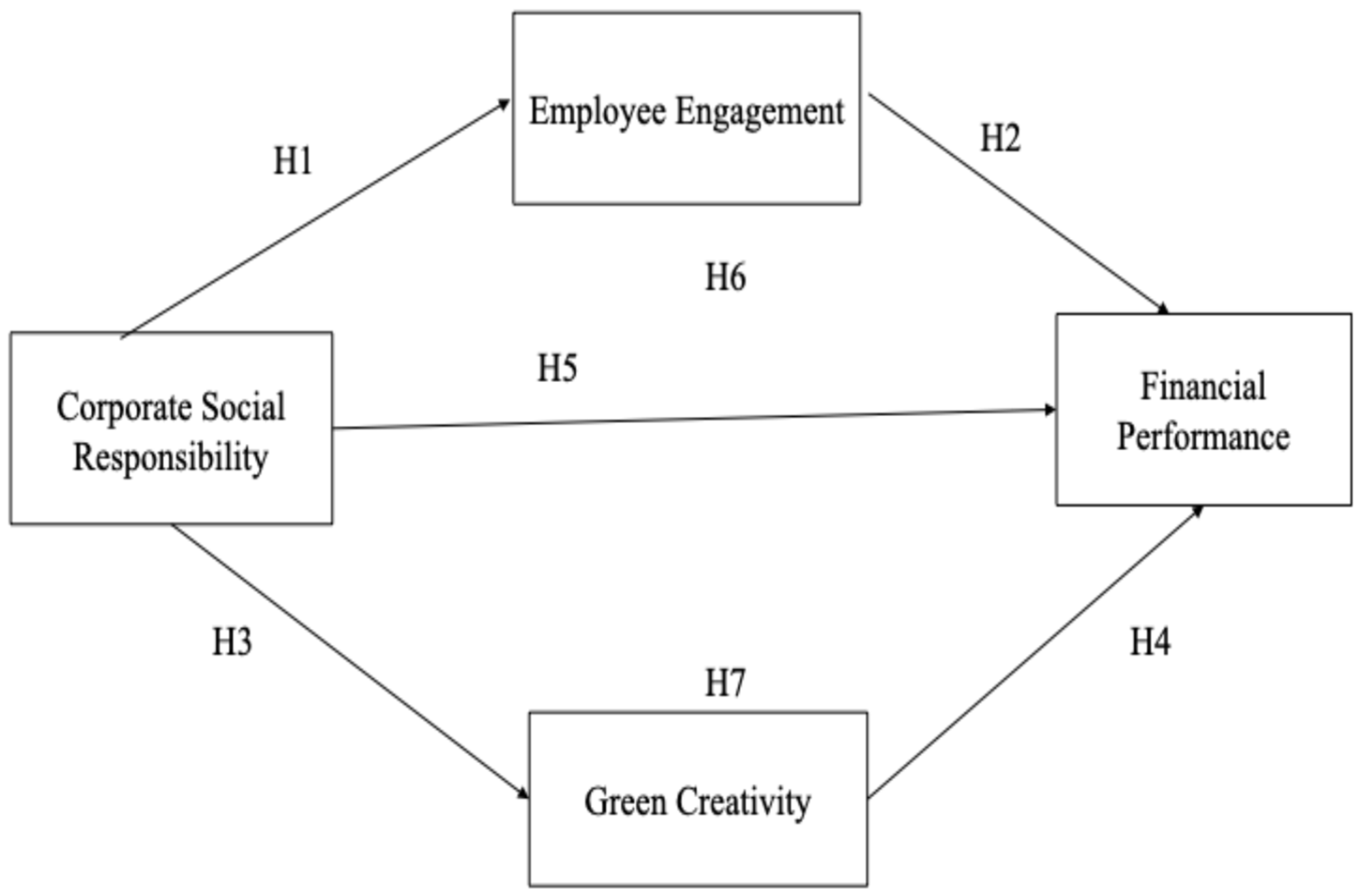

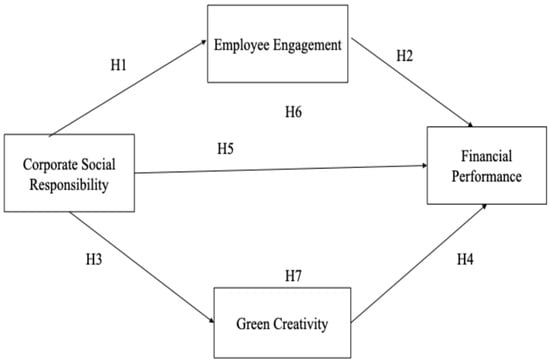

Figure 1 illustrates the survey research organization and hypotheses. EE and GC mediate the connection involving CSR and FP in the Saudi banking segment.

Figure 1.

The author’s conceptualization. Source(s): The authors own this creation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model and Techniques

This was a quantitative cross-sectional analysis. From theory to conclusion, quantitative research methods might be linear according to Bryman and Bell (2007) [79]. This study addressed demographics, CSR, EE, GC, and FP. The study found that asking identical respondents about all variables without differentiation increases the common method variance, jeopardizing internal validity [80,81]. This study used several methods to decrease procedural variance. Separate questionnaire sections were designed for each variable to avoid asking participants about all the factors simultaneously [82]. We also began each segment with specific introductory comments to set the context and emphasize the importance of queries. This study guaranteed the confidentiality and privacy of the respondents to reduce social desirability bias. Further, this study received expedited approval from the Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Institutional Review Board (IRB Log Number: 25-0529), confirming minimal risk to participants and adherence to national regulations for the protection of human subjects. We used factor examination and covariance pattern assessment to identify and reduce data analysis bias. Measurements are conceptually distinguished involving independence, mediator, and dependent variables, lowering approach difference, and boosting internal validity.

3.2. Research Sample

A three-step method was used to gather the data. Initially, a pilot test improved the validity of the questionnaire. Ten percent of the sample was gathered from bank employees to evaluate their knowledge of the survey. Later testing, the data ordinariness and quality were acceptable, involving no changes. An online questionnaire was distributed to Saudi bank employees through social media platforms. The survey was fulfilled by employees participating in strategic decision making. Convenience sampling was employed because of the limited access to a comprehensive list of bank employees. The screening questions ensured the eligibility of participants. The information was gathered from July 2024 to February 2025. The G-power test was used to determine the minimum sample size for analysis [83]. Questionnaires were distributed to 1000 bank employees, most of whom were mid- to senior-level staff directly engaged in customer service, operations, and managerial roles, thus supporting the study’s focus on CSR, employee engagement, and green creativity. Ordered follow-ups via emails and phones guaranteed highest responses; 681 responses were obtained. After excluding 31 responses with missing data, the valid sample size was 650, which is adequate for identifying anticipated associations, according to Hair et al. (2019) [84]. A total of 650 participants provided their informed consent. The participants were 86.6% males and 13.4% females. Similarly, singles were 69% and married couples were 31%. The majority represented age group was 26–30 years (28.7%), and 61.5% held a bachelor’s degree. Moreover, 40% of employees have experience within the range of 11 to 15 years.

In the present study, a high response rate was achieved. Ethical informed consent was acquired from all respondents. Previous studies emphasized the prevention of common approach bias (CMB) throughout and afterwards data gathering [80]. The respondents were informed of the research purpose, procedures, and privacy policies. The CMB was evaluated using the method described by Kock and Gaskin (2015) [85]. However, future studies could further mitigate common method bias through temporal separation, multi-source data collection, or longitudinal research designs that reduce same-time self-reporting effects. Notably, Harman’s test showed that components loaded onto a single factor, accounting for 21% of the total variance, below the 50% threshold, indicating no significant CMB. Following Kock (2015) [85], the VIF values across the integrated constructs are less than 3.3, confirming the absence of CMB. An independent sample t-test showed no significant differences between the participant groups. These methods were aligned to those used in previous studies [70].

3.3. Scales

This section includes three demographic characteristics: gender, age, and educational attainment. The present study utilized both the Arabic and English versions of the questionnaire. To ensure linguistic and conceptual equivalence between the Arabic and English versions of the instrument, we implemented a rigorous translation and back-translation protocol, consistent with Brislin (1986) [86] and van de Vijver and Leung (2021) [87]. The original English instrument was translated into Arabic by two bilingual academics specializing in management and sustainability research. An independent bilingual expert, unaware of the original instrument, back translated the Arabic description into English language. Discrepancies between the two versions were reviewed and adjudicated by a three-member academic panel to ensure their semantic and conceptual consistency. The final Arabic version was pilot tested with 10% of the target respondents to assess clarity, comprehension, and cultural appropriateness. Feedback from the pilot resulted in minor linguistic refinements, confirming the suitability of the Arabic version for administrative purposes. The investigation instrument was established utilizing present literature, and entirely factors were scored on a 5-point Likert scale. Al-Ghamdi and Badawi (2019) [88] established a five-item survey to investigate employee perspectives on CSR. EE was determined by employing a four-item scale established by Tsourvakas and Yfantidou (2018) [89] to measure employees’ mental, emotional, and physical engagement levels. To assess GC, four questions were selected and modified from prior research by Nguyen et al. (2023) [11]. Following Lin et al. (2013) [90], we used four items to assess a bank’s FP. Banks’ revenues and profit margins reduce the cost per revenue and net return on assets over five years.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement of the Model

The measurement model exhibits properties of reliability, internal consistency, discriminant validity and convergent validity. Table 1 shows that each item’s outer loading exceeded 0.50 [84], thus meeting this condition. Chin (2010) [91] investigated the internal consistency reliability of Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and composite reliability (CR). Table 1 demonstrates that all the structures had Cronbach’s alpha and CR values larger than 0.70, indicating excellent internal consistency, except for GC2. During the measurement validation stage, the item GC2 (“Bank employees propose new green ideas to improve environmental performance”) was excluded due to its low outer loading (<0.70) and conceptual overlap with GC1 and GC3. This overlap potentially blurred the distinction between ideation and advocacy behaviors within the Green Creativity construct. Sensitivity analyses were conducted with and without GC2, and the results showed no material differences in reliability, validity, or structural path significance, confirming that its exclusion did not affect the study’s conclusions. The item overlaps conceptually with GC1 (“Bank employees suggest new ways to achieve environmental goals”) and GC3 (“Bank employees promote and champion new green ideas to colleagues”), leading to potential redundancy and interpretive ambiguity. Specifically, “propose new green ideas” may have been interpreted by respondents as either ideation or implementation behavior, blurring the distinction between creative and active advocacy. This overlap is likely to reduce the discriminant contribution to the Green Creativity construct [23,68].

Table 1.

Assessing Reliability & Validity.

To ensure construct robustness, sensitivity analyses were conducted by re-estimating the measurement and structural models, with and without GC2. The comparative results showed no material changes in reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.86 with GC2; 0.90 without), composite reliability (CR = 0.93–0.94), or AVE (0.76–0.84). The structural relationships between CSR, GC, and FP also remained stable (β < 0.02; R2 < 0.01), confirming that the removal of GC2 enhanced the clarity and parsimony of the GC construct without compromising content validity or model integrity. Convergent validity exists for the linked construct assessments [92]. Convergent validity requires constructs’ Average Variance Extracted (AVE) to be at least 0.50, according to Hair et al. (2021) [93]. Table 1 shows that the building’s average variance exceeded 0.50. 2 Initially, one can compare the square root of the AVE to the correlational data. Next, we compared the AVE and squared correlation coefficients. As shown in Table 2, the diagonal values surpassed the column and row values. We applied two complementary checks for discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker and HTMT). Initially, one can compare the square root of the AVE to the correlational data. Next, we compared the AVE and squared correlation coefficients. In this regard, Garson (2016) [94] presented the Fornell and Larcker correlation criterion to evaluate discriminant validity. Our results were consistent with the Fornell and Larcker criteria (Table 2). We assessed discriminant validity ensuring each construct is distinct from others in the model using the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations. This stricter criterion, recommended by Henseler et al. (2015) [95], has gained traction in recent financial management studies. Table 3 reports HTMT values for all construct pairs, ranging from 0.378 to 0.640 and falling well below the 0.85 threshold. These results confirm strong discriminant validity, indicating that each construct measures unique aspects not captured by others, thereby upholding the distinctiveness of the theoretical concepts under examination. Table 4 reports the inner VIF values used to assess multicollinearity among the predictor constructs. All VIF values ranged between 1.000 and 1.368, well lower than the normal threshold of 5 (or the more conservative cutoff of 3.3), indicating that multicollinearity is not a worry in the structural model. Early late-wave and non-response bias diagnostics indicated no significant mean differences across the core constructs (p > 0.05), and the marker variable and full collinearity (VIF < 3.3) tests confirmed the absence of common method bias, with model-fit deltas within acceptable thresholds. Although a convenience sampling approach was employed because of the absence of a centralized employee directory, the study drew participants from multiple Saudi commercial and Islamic banks identified through professional and institutional networks, ensuring adequate heterogeneity across bank size and ownership type. Nonetheless, the male-dominant sample reduces the generalizability of our conclusions to a wider banking workforce.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity using the Fornell–Lacker Criterion.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity using HTMT.

Table 4.

Inner VIF values.

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized owing to the analysis’s prediction-oriented objective to explain the variance in perceived financial performance (R2 = 0.742) and the non-normal distribution of several indicators, where skewness and kurtosis exceeded ±1.0. This approach is appropriate for complex models involving multiple endogenous constructs (EE, GC, and FP) and the mediating effects under non-normal conditions [84,93].

All constructs in the research were modeled as reflective, in harmony with hypothetical assumptions and observed inter-item correlations. No formative constructs were specified as each indicator was conceptualized to reflect, rather than form, the underlying latent variable. The bootstrapping procedure used 5000 subsamples with two-tailed testing and bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) confidence intervals to ensure robust significance estimation. The model established substantial descriptive power, with R2 values of 0.236 (EE), 0.110 (GC), and 0.742, for EE, and (FP). The effect sizes (f2) indicated that EE (1.262) exerted a large influence on FP, whereas GC (0.236) and CSR (0.037) had medium and small effects, respectively. The predictive relevance (Q2) obtained through blindfolding confirmed a strong predictive validity for FP (Q2 = 0.481) and small-to-moderate values for EE and GC (Q2 = 0.119 and 0.089, respectively). The PLS-Predict results further support the model’s out-of-sample predictive accuracy.

Table 5 describes the model adequate and predictive indices of the saturated and estimated models. Regarding the model fit indices, the SRMR values for the appeased and projected models (0.100 and 0.109, respectively) fall marginally acceptable for a prediction-oriented PLS-SEM model, as the primary focus is on maximizing predictive relevance (Q2, PLSpredict) rather than achieving strict model fit criteria. Ref. [96], and the d_ULS (1.373/1.605) and d_G (0.786/0.807) values indicate minor discrepancies between the models. The NFI value (≈0.63) denotes a modest comparative fit, which is typical for prediction-oriented PLS models that emphasize variance explanation rather than covariance-based model fit. Because we adopt PLS-SEM with a predictive focus, we emphasize R2/Q2 and out-of-sample indicators when interpreting model performance.

Table 5.

Model fit/predictive indices.

These results confirm that PLS-SEM is methodologically appropriate and that the model exhibits adequate reliability, validity, and predictive strength in explaining perceived financial performance outcomes in the Saudi banking context.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing Results

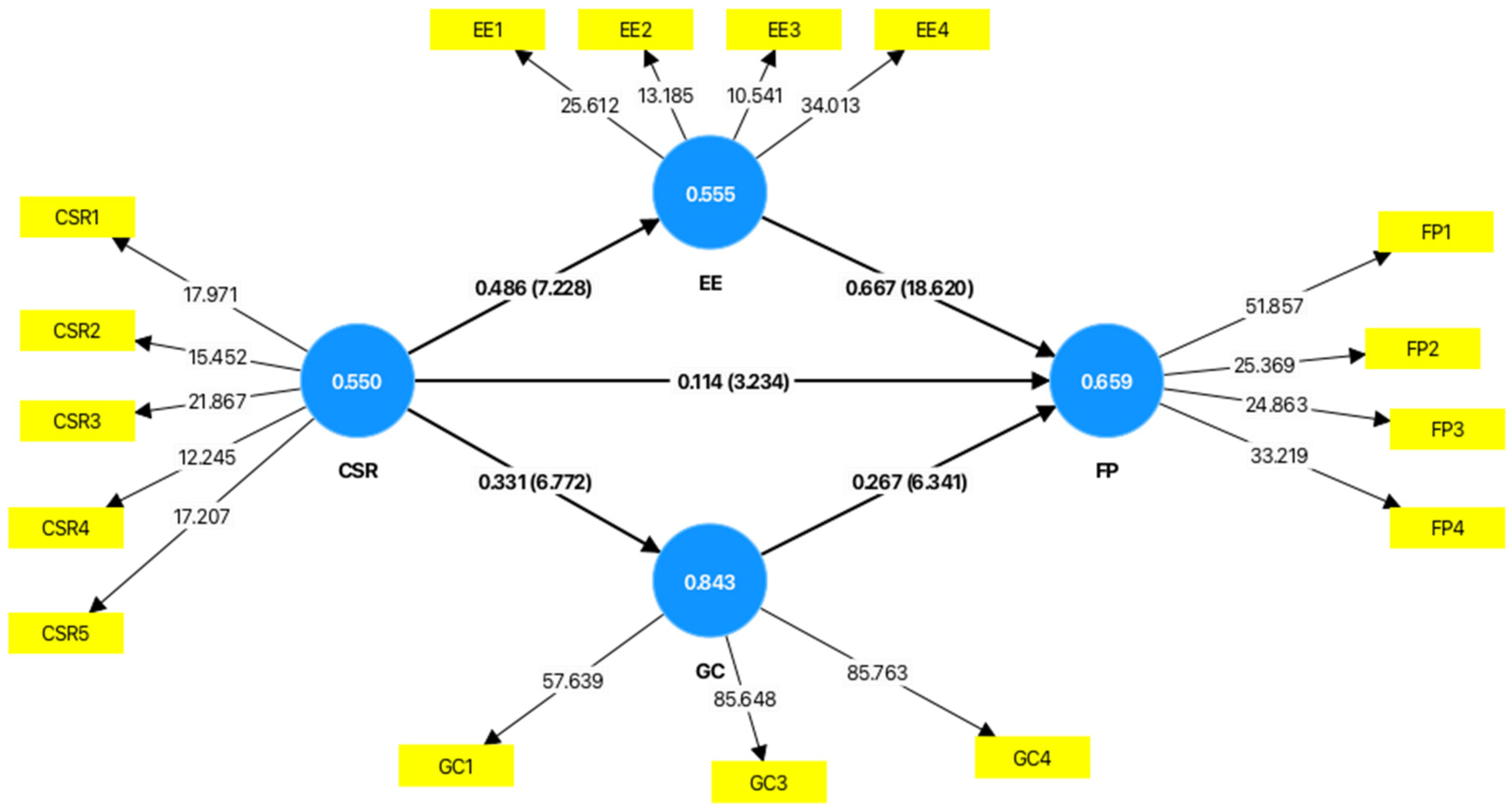

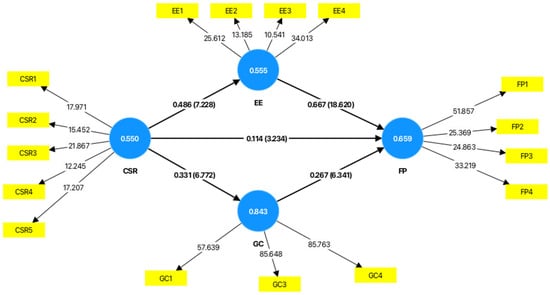

This section presents an assessment of our proposed hypotheses. Table 3 presents the values and p-values for assessing the hypotheses and guiding their acceptance and rejection. This section presents a structural model to estimate the anticipated assumptions. The investigators used a operational model to measure the value and the p-value to assess the assumptions. The overall structural relationships are summarized in Figure 2 and detailed numerically in Table 6 and Table 7. The hypothesis is acceptable when the t-value exceeds 1.96 or the p-value falls below 0.05. Table 6 shows the association involving direct and indirect hypotheses. The structural model in Figure 2 demonstrates the significance of p-values and t-values. These outcomes afford insights into the connections connecting CSR, EE, GC, and FP, offering perspectives that build upon earlier discoveries. As shown in Figure 2 and Table 7, both the direct path (CSR → FP) and the mediated paths via EE and GC are statistically significant. This study shows that employee engagement improves through CSR initiatives (H1: Î2 = 0.492, p < 0.001, supported). Studies in the Saudi banking sector show that CSR positively influences EE, indicating that ethical practices foster employee commitment. For Hypothesis 2, the results reveal that EE directly influences the FP of Saudi banks (β = 0.669, p < 0.001). Organizations can cultivate environmental skills through CSR initiatives (H3: β = 0.336, p < 0.001, supported). Organizations that obtain assistance are predisposed to embrace sustainable methodologies and ecological advancements.

Figure 2.

SEM model. Source(s): Software output.

Table 6.

Results of hypothesis testing: direct effects.

Table 7.

Results of hypothesis testing: direct and indirect effects.

The effectiveness of entities allocating resources to GC tends to improve FP (H4: β = 0.267, p < 0.001, supported). Studies suggest that EE and fostering GC alleviate this phenomenon, although CSR directly contributes to improved FP (H5: Î2 = 0.114, p = 0.001, supported). For H6 and H7, the indirect effects were significant. The bootstrapped 95% CIs for CSR → EE → FP (β = 0.329, CI [0.243, 0.418]) and CSR → GC → FP (β = 0.090, CI [0.052, 0.142]) did not include zero, confirming mediation. The variance accounted for (VAF) was 74% for the EE mediation path and 44% for the GC mediation path, indicating partial mediation in both cases since the direct effect (CSR → FP, β = 0.114, p < 0.01) remained significant. Thus, CSR influences FP both directly and indirectly, with the strongest pathway operating through employee engagement (See Appendix A). The f2 value indicates the influence of an exogenous construct on an endogenous one [97]. Cohen (1992) [98,99] defined three f2 value ranges: smaller (0.02), medium (0.15), and larger (0.35) effects. The findings indicate that empirical values influence FP. EE has a larger effect on FP (f2 = 1.262) than CSR, which has a minor influence on FP (f2 = 0.037). The GC value (f2 = 0.236) substantially affected FP, as illustrated in Table 4. These findings confirm the influence of CSR on EE and GC, which improves FP. This aligns with previous studies showing the need to embed CSR in business strategies for sustainable success. R2 showed a strong predictive accuracy, with EE, GC, and FP values of 0.236, 0.110, and 0.742, correspondingly (Table 8). R2 values above 0.26, between 0.13 and 0.26, and below 0.02 indicate Strong, moderate, and weak predictions, respectively [98]. Table 9 reports the Q2 values obtained through blindfolding to assess the predictive relevance. Q2 values above zero imply the analytical capability of the model. As shown, CSR (p < 0.001) has no predictive relevance, whereas EE (0.119) and GC (0.089) have small predictive relevance. FP (0.481) demonstrates strong predictive relevance, highlighting the model’s ability to explain the variance in financial performance.

Table 8.

F2 and R2 values.

Table 9.

Q2 Values.

5. Discussion

The outcomes highlight the substance of CSR as a strategic instrument for increasing organizational performance while simultaneously contributing to sustainable development. First, the findings verify that CSR has a favorable influence on EE, consistent with SIT. When workforce recognizes their organization, they become further motivated, committed, and satisfied with their jobs, because they feel that their organization is socially responsible. This conclusion corresponds to other studies [16,18,73] that indicate that CSR programs make employees feel more emotionally attached to their workplace, decrease employee turnover, and improve their work outcomes. Notably, the insightful mediation effect of EE indicates that employee-driven CSR activities are essential for transforming social responsibility activities into better financial results. Second, CSR was identified as having a positive impact on GC, indicating that socially responsible practices contribute to the innovation of environmentally sustainable products, services, and processes. This result expands the research of Kraus et al. (2020) [14], who emphasize CSR as a source of ecological innovation. In keeping with SIT, employees who align themselves with a socially accountable corporation are more likely to support green initiatives, thus strengthening environmental legitimacy. FP is also directly enhanced by GC, which supports Imran et al. (2022) [5] and Chen et al. (2023) [66], who underline that green innovation represents the power to reduce costs, gain a competitive edge, and ensure the resilience of an organization. Third, the findings indicate that both EE and GC mediate the CSR-FP relationship, but EE has a stronger influence. This emphasizes the two-way channel through which CSR can be converted into financial performance by enhancing the commitment of employees and the other by encouraging environmentally innovative practices.

Although the direct path from CSR to FP is statistically substantial (β = 0.114, p < 0.01), the relatively modest coefficient suggests that CSR produces incremental improvements only in financial outcomes (see Table 6 and Figure 2 for standardized coefficients). By contrast, the indirect channels of employee engagement (β = 0.669) and green creativity (β = 0.267) exert much stronger effects, highlighting that CSR initiatives translate into meaningful financial gains primarily when they enhance workforce commitment and foster innovation. From a managerial perspective, banks should use CSR to lift employee engagement (EE) and green creativity (GC), which in turn drive financial performance (FP). With EE accounting for approximately 74% of the variance (VAF) and GC contributing around 44%, these mediation pathways represent critical levers for translating CSR efforts into tangible financial benefits. This approach implies that banks should not expect immediate, large-scale financial returns from CSR activities in isolation but rather should focus on leveraging CSR to strengthen EE and promote GC as the primary drivers of FP.

Standardized coefficients confirm these relative magnitudes: the effect of EE on FP is almost six times greater than that of the direct CSR → FP path, whereas GC’s effect of GC on GC is more than double. This comparative interpretation underscores the practical importance of embedding CSR into human capital strategies and green innovation agendas. While we report standardized effects for comparability, unstandardized estimates further highlight that the economic impact of CSR becomes substantial only when it is mediated by EE and GC. Future research may further enhance interpretation by plotting marginal effects with confidence intervals to visually demonstrate the strength and certainty of these relationships.

These findings reinforce that, while CSR has a direct but modest effect on FP, its economic significance is greatly amplified through its mediating channels. EE accounts for the majority of the mediated variance, consistent with Social Identity Theory’s emphasis on employee identification as a driver of organizational outcomes. GC provides an additional, but smaller channel, demonstrating that CSR-induced innovation also contributes meaningfully. Both mediations are partial given that the direct CSR → FP path remains significant. Although we adopted a parallel mediation framework, future research could extend this work by testing sequential effects, such as CSR → EE → GC → FP, which may capture the dynamic linkages between employee identification and innovation.

This study’s results have several implications. First, it yields a substantial theoretical involvement to the current body of novel by observing the characters of EE and GC as mediators in the connection relating CSR and FP and turnover intention among Saudi Arabian banking industry employees. This study introduces a new perspective on how CSR initiatives can boost employees’ emotional attachment to their work environment, turnover, and overall job satisfaction by incorporating the Social Identity Theory (SIT) lens [40,86]. CSR plays a fundamental function in influencing customers’ and employees’ perceptions in the banking industry. The sustainable and moral procedures of banks are likely to lead to long-term customer loyalty and trust. According to SIT, in organizations that experience a high CSR program, there is a higher probability that employees will demonstrate pro-organizational behaviors, including innovation and environmental sustainability commitment [34]. This study uses this theoretical base to explain why CSR influences EE, GC, and FP in Saudi banks. Although SIT pays much attention to the benefits of EE as an organizational agile company, the present investigation emphasizes the fundamental role of EE and GC as mediating variables between CSR and FP. This finding offers theoretical perceptions into the determinants of employee performance and business purpose in the banking business in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Second, this study offers meaningful information to the banking industry in Saudi Arabia, especially regarding the design and execution of CSR systems. Implementing CSR in their fundamental strategies allows banks to not only increase worker performance, but also decrease turnover intentions, which sustains organizational stability. This evidence highlights the principal role of developing a great sense of managerial character and dedication among employees, which is the result of staff members viewing their institution as socially and ecologically responsible. In this context, CSR can go beyond the sphere of a reputational tool to create loyalty, motivation, and long-term involvement in the workforce. Moreover, the findings highlight the importance of tailor-made training and development interventions that incorporate CSR principles. These programs may be aimed at creating awareness of sustainability issues, promoting employees’ involvement in the realization of green programs, and providing the necessary knowledge to develop innovative and more environmentally friendly solutions. Through training that is linked to organizational needs, banks will be able to create a culture in which employees do not merely identify with organizational values but also feel like they are active participants in the social and environmental causes of the organization. These insights have implications for policy and regulatory agencies in Saudi Arabia on a larger scale. Incentives, guidelines, or reporting structures can be used to encourage banks to institutionalize CSR so that CSR is not considered a voluntary or secondary business activity, but rather a pillar of the business strategy. This study contributes by extending CSR–FP mediation research to the underexplored Saudi banking context, where Shariah governance, regulatory oversight, and ESG exposure shape outcomes differently than in prior settings. The findings show that CSR’s financial value is realized mainly through employee engagement and green creativity, thus clarifying the inconsistencies in earlier studies. We also propose boundary conditions such as regulatory intensity and bank size that may moderate these effects. Finally, by linking CSR mechanisms to Vision 2030 priorities, this study highlights how CSR can drive sustainable finance and human capital advancement in line with the national policy objectives.

6. Conclusions

This study explores the connection concerning corporate social responsibility (CSR) and perceived financial performance (FP) in the Saudi Arabian banking industry by considering the mediating variables of employee engagement (EE) and green creativity (GC). The study was guided by Social Identity Theory (SIT) to establish (1) the effect of CSR on EE, GC, and FP; (2) the direct effect of EE and GC on FP; and (3) the mediation of the association linking CSR and FP by EE and GC. A quantitative, cross-sectional plan was utilized to achieve these objectives. A total of 650 banking employees were surveyed using a bilingual instrument. The constructs were measured using established scales, and the measurement and organizational models were calculated operating Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), which guaranteed validity, consistency, and sturdy hypothesis testing.

These findings provide strong evidence that CSR significantly enhances EE, GC and FP. Both EE and GC act as mediators, with EE exerting a stronger effect and highlighting its importance in translating CSR initiatives into tangible financial outcomes. These results confirm CSR’s considered function in advancing organizational resilience, encouraging innovation, and aligning financial goals with social and environmental responsibilities. This study advances the CSR performance debate in developing economies by offering empirical evidence from Saudi Arabia, a country where such research remains limited. Despite its contributions, this investigation involves a number of limitations that warrant acknowledgment and have to be carefully considered in guiding potential research endeavors. First, the perceived financial performance reflects employees’ perceptions rather than audited bank-level outcomes. While this approach captures valuable internal insights, it may introduce an ecological fallacy. Future research could triangulate these perceptions with archival indicators such as ROA, ROE, or cost-to-income ratios to validate and enrich the findings. Additionally, as the conclusions were received from single-source, cross-sectional data using convenience sampling, the generalizability of the findings is limited. Upcoming analyses are encouraged to adopt multi-source and longitudinal designs incorporating objective performance measures to enhance their generalizability. Second, while this study provides valuable insights into the mediating functions of employee involvement and green creativity in the CSR–perceived financial accomplishment association, its scope is confined to empirically measured constructs. Although the discussion touched on broader organizational outcomes such as turnover intention and employee well-being, these variables were not directly tested in our model. Future research could extend the framework to incorporate such outcomes, thereby suggesting a more inclusive interpretation of how CSR initiatives influence organizational sustainability.

Third, a key limitation of this study is that perceived financial performance (FP) was measured using employee perceptions rather than objectively audited financial data. While subjective measures are commonly used in CSR–FP studies, where organizational-level financial data are inaccessible, they may still introduce bias, particularly when respondents are asked to recall multiyear trends. Future research should triangulate perceptual FP measures with objective accounting- or market-based indicators to validate and extend the present findings. Lastly, we acknowledge that the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) represents an important robustness check when comparing subgroups in PLS-SEM models. However, MICOM was not used in the current analysis because cross-group assessments were beyond the scope of our analytical objectives. Our analysis focused on testing the hypothesized structural relationships at the pooled sample level rather than examining potential differences in means or path coefficients across subgroups, such as language, gender, or managerial level. Future research could extend our findings by incorporating MICOM-based multigroup analysis to explore whether the observed relationships hold consistently across diverse demographic and organizational segments. Overall, this study demonstrates that CSR, when effectively implemented, not only strengthens financial outcomes but also enhances employee commitment and fosters green innovation. In doing so, it highlights the central role of CSR in advancing economic, social, and environmental sustainability, fully aligning with the mission of sustainability to promote research that supports long-term development and organizational resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.A.B. and S.D.G.; methodology, S.D.G. and R.E.E.H.; software, R.E.E.H. and R.H.J.; validation, A.O.A.B.; formal analysis, A.O.A.B.; investigation, R.E.E.H.; resources, A.O.A.B.; data curation, R.E.E.H. and M.Z.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Z.A.; writing—review and editing, A.O.A.B., S.D.G., R.E.E.H., R.H.J., M.Z.A. and A.S.A.; visualization, A.O.A.B.; supervision, R.E.E.H.; project administration, S.D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman, grant number PNURSP2025R863.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University (protocol code 25-0529 and date of approval: 21 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was secured from all participants in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R863), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors agree that this research was conducted in the absence of any self-benefits, commercial or financial conflicts.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurement of scales.

Table A1.

Measurement of scales.

| Section 1 | Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| CSR 1 | This bank is socially responsible. | Al-Ghamdi and Badawi (2019) [88] |

| CSR 2 | This bank protects the environment. | |

| CSR 3 | This bank contributes to the welfare of society. | |

| CSR 4 | This bank contributes to the donation programs. | |

| CSR 5 | This bank always meets customer’s expectations. | |

| Section 2 | Employee Engagement (EE) | Tsourvakas and Yfantidou (2018) [89] |

| EE 1 | I love to work for this organization. | |

| EE 2 | I feel proud to work for this organization. | |

| EE 3 | I feel I can make a difference in this organization. | |

| EE 4 | I believe I can make a valuable contribution to the success of this organization. | |

| Section 3 | Green creativity (GC) | |

| GC 1 | Bank employees suggest new ways to achieve environmental goals. | Nguyen et al. (2023) [11] |

| GC 2 | Bank employees propose new green ideas to improve environmental performance. | |

| GC 3 | Bank employees promote and champion new green ideas to colleagues. | |

| GC 4 | Bank employees implement green ideas into a comprehensive plan | |

| Section 4 | Perceived financial performance (FP) | |

| FP1 | Our bank’s revenue is continuously increasing over the past five years | Lin et al. (2013) [90] |

| FP2 | Our bank profit is continuously increasing over the past five years | |

| FP3 | Our bank has been continuously reducing cost per revenue unit over the past five years | |

| FP4 | Our bank’s net return on assets has been increasing over the past five years |

Table A2.

VIF Inner model.

Table A2.

VIF Inner model.

| Relationship of Latent Variable | VIF |

|---|---|

| CSR EE | 1.000 |

| CSR FP | 1.368 |

| CSR GC | 1.000 |

| EE FP | 1.366 |

| GC FP | 1.172 |

Table A3.

Outer Loading Values.

Table A3.

Outer Loading Values.

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR1 | 0.750 | 0.750 | 0.042 | 17.971 | 0.001 |

| CSR2 | 0.732 | 0.728 | 0.047 | 15.452 | 0.001 |

| CSR3 | 0.786 | 0.784 | 0.036 | 21.867 | 0.001 |

| CSR4 | 0.713 | 0.706 | 0.058 | 12.245 | 0.001 |

| CSR5 | 0.724 | 0.723 | 0.042 | 17.207 | 0.001 |

| EE1 | 0.812 | 0.811 | 0.032 | 25.612 | 0.001 |

| EE2 | 0.705 | 0.702 | 0.054 | 13.185 | 0.001 |

| EE3 | 0.663 | 0.656 | 0.063 | 10.541 | 0.001 |

| EE4 | 0.790 | 0.792 | 0.023 | 34.013 | 0.001 |

| FP1 | 0.852 | 0.852 | 0.016 | 51.857 | 0.001 |

| FP2 | 0.803 | 0.801 | 0.032 | 25.369 | 0.001 |

| FP3 | 0.783 | 0.782 | 0.032 | 24.863 | 0.001 |

| FP4 | 0.808 | 0.808 | 0.024 | 33.219 | 0.001 |

| GC1 | 0.904 | 0.903 | 0.016 | 57.639 | 0.001 |

| GC3 | 0.922 | 0.922 | 0.011 | 85.648 | 0.001 |

| GC4 | 0.929 | 0.929 | 0.011 | 85.763 | 0.001 |

Table A4.

Cross-Loading Values.

Table A4.

Cross-Loading Values.

| CSR | EE | FP | GC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR1 | 0.750 | 0.393 | 0.431 | 0.282 |

| CSR2 | 0.732 | 0.336 | 0.359 | 0.336 |

| CSR3 | 0.786 | 0.451 | 0.458 | 0.211 |

| CSR4 | 0.713 | 0.289 | 0.280 | 0.149 |

| CSR5 | 0.724 | 0.296 | 0.389 | 0.228 |

| EE1 | 0.325 | 0.812 | 0.623 | 0.321 |

| EE2 | 0.263 | 0.705 | 0.494 | 0.414 |

| EE3 | 0.415 | 0.663 | 0.444 | 0.244 |

| EE4 | 0.427 | 0.790 | 0.780 | 0.086 |

| FP1 | 0.425 | 0.693 | 0.852 | 0.492 |

| FP2 | 0.491 | 0.654 | 0.803 | 0.314 |

| FP3 | 0.474 | 0.637 | 0.783 | 0.306 |

| FP4 | 0.332 | 0.647 | 0.808 | 0.572 |

| GC1 | 0.353 | 0.335 | 0.506 | 0.904 |

| GC3 | 0.258 | 0.269 | 0.446 | 0.922 |

| GC4 | 0.294 | 0.297 | 0.488 | 0.929 |

Table A5.

Confidence Interval Values.

Table A5.

Confidence Interval Values.

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | 2.5% | 97.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR EE | 0.486 | 0.492 | 0.360 | 0.620 |

| CSR FP | 0.114 | 0.114 | 0.044 | 0.182 |

| CSR GC | 0.331 | 0.336 | 0.236 | 0.427 |

| EE FP | 0.667 | 0.669 | 0.599 | 0.738 |

| GC FP | 0.267 | 0.267 | 0.184 | 0.352 |

References

- Meng, X.; Imran, M. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Organizational Performance with the Mediating Role of Employee Engagement and Green Innovation: Evidence from the Malaysian Banking Sector. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2024, 37, 2264945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, G.; Kalia, Y.; Arora, N. Sustainability in the Deepfake Era—The Role of CSR and Ethical Leadership in Mitigating Risks. In Navigating the Deepfake Conundrum: A Manager’s Roadmap; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 44, pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sarto, N. The Evolution of Sustainability: From CSR to Sustainable Finance. In ESG Factors and Financial Outcomes in Banks; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y. Driving Employee Engagement through CSR Communication and Employee Perceived Motives: The Role of CSR-Related Social Media Engagement and Job Engagement. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2024, 61, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Jingzu, G. Green Organizational Culture, Organizational Performance, Green Innovation, Environmental Performance: A Mediation-Moderation Model. J. Asia-Pac. Bus. 2022, 23, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, O.; Ahmad, B.S. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on the Financial Performance of Banks in Pakistan: Serial Mediation of Employee Satisfaction and Employee Loyalty. J. Public Aff. 2022, 22, e2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 15, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Misra, M. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Organizational Performance: The Moderating Effect of Corporate Reputation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.C.T. The Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Financial Performance: Firm-Level Evidence from Taiwan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Liu, C.; Teng, W. The Heterogeneous Effects of CSR Dimensions on Financial Performance: A New Approach for CSR Measurement. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.T.; Nguyen, L.T.; Nguyen, N.Q. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: The Case in Vietnam. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2075600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.F.; Long, H.; Wang, H.J.; Chang, C.P. Environmental, Social and Governance, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Stock Returns: What Are the Short- and Long-Run Relationships? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1884–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Omrane, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Overall Effects on Financial Performance: Empirical Evidence from Indian Companies. J. Afr. Bus. 2022, 23, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Environmental Strategy and Green Innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahta, D.; Yun, J.; Islam, M.R.; Ashfaq, M. Corporate Social Responsibility, Innovation Capability and Firm Performance: Evidence from SME. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 840–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.Y.; Asrar-ul-Haq, M.; Amin, S.; Noor, S.; Haris-ul-Mahasbi, M.; Aslam, M.K. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement in the Manufacturing Sector of Pakistan. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2908–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Lozano, C.P.; Collazzo, P. Corporate Social Responsibility, Green Innovation and Competitiveness—Causality in Manufacturing. Compet. Rev. 2022, 32, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Bunchapattanasakda, C. Employee Engagement: A Literature Review. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 2019, 9, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, C.H.; Ibrahim, H.; Tang, S.M. The Determinants of Turnover Intention among Bank Employees. J. Bus. Econ. Anal. 2022, 3, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M Falahat, G.K. A Model for Turnover Intention: Banking Industry in Malaysia. Asian Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 24, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, W.; Yapa, P.; Safari, M.; Watts, S. The Influence of Earnings Management on Bank Efficiency: The Case of Frontier Markets. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Rasool, Z.; Sarmad, M.; Ahmed, A.; Ahmed, U. Strategic Attributes and Organizational Performance: Toward an Understanding of the Mechanism Applied to the Banking Sector. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 855910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. The Determinants of Green Product Development Performance: Green Dynamic Capabilities, Green Transformational Leadership, and Green Creativity. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 116, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad Mubarak Hussien, M.; Abubkr Ahmed Elhadi, A.; Abbas Abdelrahman, A. Factors Affecting Climate Change Accounting Disclosure Among SaudiPublicly List Firms on the Saudi Stock Exchange Market. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2023, 10, 0099–0108. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcahyo, S.A.; Wikaningrum, T.; Thoha, A.M. Green Banking Practices and HRM in Enchancing Innovation Capability: A Knowledge Management Perspective on Sharia Banking Performance. Diponegoro Int. J. Bus. 2025, 8, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktadir-Al-Mukit, D.; Hossain, M.A. Sustainable Development and Green Financing: A Study on the Banking Sector in Bangladesh. In Social Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Development; Routledge: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.A.A.; Alodat, A.Y.; Salleh, Z.; Al-Ahdal, W.M. The Effect of Audit Committee Effectiveness, Internal Audit Size and Outsourcing on Greenhouse Gas Emissions Disclosure. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2025, 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.C.; Nie, J.; Ran, R.; Gu, Y. Corporate Social Responsibility, Social Identity, and Innovation Performance in China. Pac. -Basin Financ. J. 2020, 63, 101415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherif, F. The Role of Human Resource Management Practices and Employee Job Satisfaction in Predicting Organizational Commitment in Saudi Arabian Banking Sector. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2020, 40, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrab, M.; Al-Mamary, Y.H.S.; Alwaheeb, M.A.; Alshammari, N.G.M.; Balhareth, H.; Al-Shammari, S.A. Mediating Role of Strategic Orientations in the Relationship between Entrepreneurial Orientation and Performance of Saudi SMEs. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2021, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, S.; Mashayekhi, B.; Jahangard, A.; Samavat, M.; Rezaee, Z. The Controversial Link between CSR and Financial Performance: The Mediating Role of Green Innovation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H.; Aftab, J.; Ishaq, M.I.; Atif, M. Achieving Business Competitiveness through Corporate Social Responsibility and Dynamic Capabilities: An Empirical Evidence from Emerging Economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 386, 135820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewstone, M. Intergroup Conflict Group Perspectives on Intergroup. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 35, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The Psychological Microfoundations of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Person-Centric Systematic Review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M.; Russo, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective CommitmentA Multiple Mediation Model. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, E.G.; Saxe, R. The power of being heard: The benefits of ‘perspective-giving’ in the context of intergroup conflict. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alketbi, M.S.; Ahmad, S.Z. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability Practices: Mediating Effect of Green Innovation and Moderating Effect of Knowledge Management in the Manufacturing Sector. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2024, 32, 1369–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesari, A.E.; Shadiardehaei, E.; Shahrabi, B. The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Brand Performance with the Mediating Role of Corporate Reputation, Resource Commitment and Green Creativity. Teh. Glas. 2021, 15, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides-Velasco, C.A.; Quintana-García, C.; Marchante-Lara, M. Total quality management, corporate social responsibility and performance in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatila, K.; Martínez-Climent, C.; Enri-Peiró, S. The Mediating Roles of Corporate Reputation, Employee Engagement, and Innovation in the CSR—Performance Relationship: Insights from the Middle Eastern Banking Sector. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrabiah, A. Optimal Regulation of Banking System’s Advanced Credit Risk Management by Unified Computational Representation of Business Processes across the Entire Banking System. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1486685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Sohail, M.S.; Munshi, M.M.R. Sharīʿah Governance and Agency Dynamics of Islamic Banking Operations in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. ISRA Int. J. Islam. Financ. 2022, 14, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, R. The Effectiveness of Green Banking in Saudi Arabia. Access Justice East. Eur. 2023, 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F.A. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouna, Y.; Benlaria, A.; Benzidi, A.; Mediani, M.; Bennaceur, M.Y. The Impact of Capital Adequacy on Bank Market Value: Evidence from Islamic and Conventional Banks in Saudi Arabia. Lex Localis—J. Local Self-Gov. 2025, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karassin, O.; Bar-Haim, A. How Regulation Effects Corporate Social Responsibility: Corporate Environmental Performance under Different Regulatory Scenarios. World Political Sci. 2019, 15, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, S.E.; Rafiki, A. Comparative Analysis of Customers’ Awareness toward CSR Practices of Islamic Banks: Bahrain vs Saudi Arabia. Soc. Responsib. J. 2022, 18, 1142–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibe-enwo, G.; Igbudu, N.; Garanti, Z.; Popoola, T. Assessing the Relevance of Green Banking Practice on Bank Loyalty: The Mediating Effect of Green Image and Bank Trust. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladapo, I.A. Examining the Factors That Influence Green Banking Practices among Saudi Arabian Islamic Banks. Int. J. Technol. Learn. Innov. Dev. 2025, 16, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazi, M.A.I.; Masud, A.A.; Kabir, S.b.; Chaity, N.S.; Senathirajah, A.R.b.S.; Rahman, M.K.H. Impact of Green Banking Practices on Green CSR and Sustainability in Private Commercial Banks: The Mediating Role of Green Financing Activities. J. Sustain. Res. 2024, 6, e240072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshashai, D.; Leber, A.M.; Savage, J.D. Saudi Arabia Plans for Its Economic Future: Vision 2030, the National Transformation Plan and Saudi Fiscal Reform. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2020, 47, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laallam, A.; Alsubayt, F.M.; Kashi, A.; Nomran, N.M. Exploring the Impact of Green Banking Practices on Environmental Performance: The Case of Saudi Arabia and Vision 2030. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Agarwal, A.; Madan, P.; Kautish, P. How Do Green CSR Initiatives Influence Green Employee Engagement among Tourism and Hospitality Employees? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employee Engagement: Enabling Employees to Employ More of Their Whole Selves at Work. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 183377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, A.A.; Salleh, Z.; Alahdal, W.M.; Hussien, A.M.; Bajaher, M.; Baatwah, S.R. The Effect of the Board of Directors, Audit Committee, and Institutional Ownership on Carbon Disclosure Quality: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Committee. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 2254–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, N.; Kapse, M.; Alagarsamy, S.; Sharma, V. Responsible Leadership and Task Performance: Understanding Intrinsic CSR Attribution as a Mediating Mechanism. In Responsible Corporate Leadership Towards Attainment of Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]