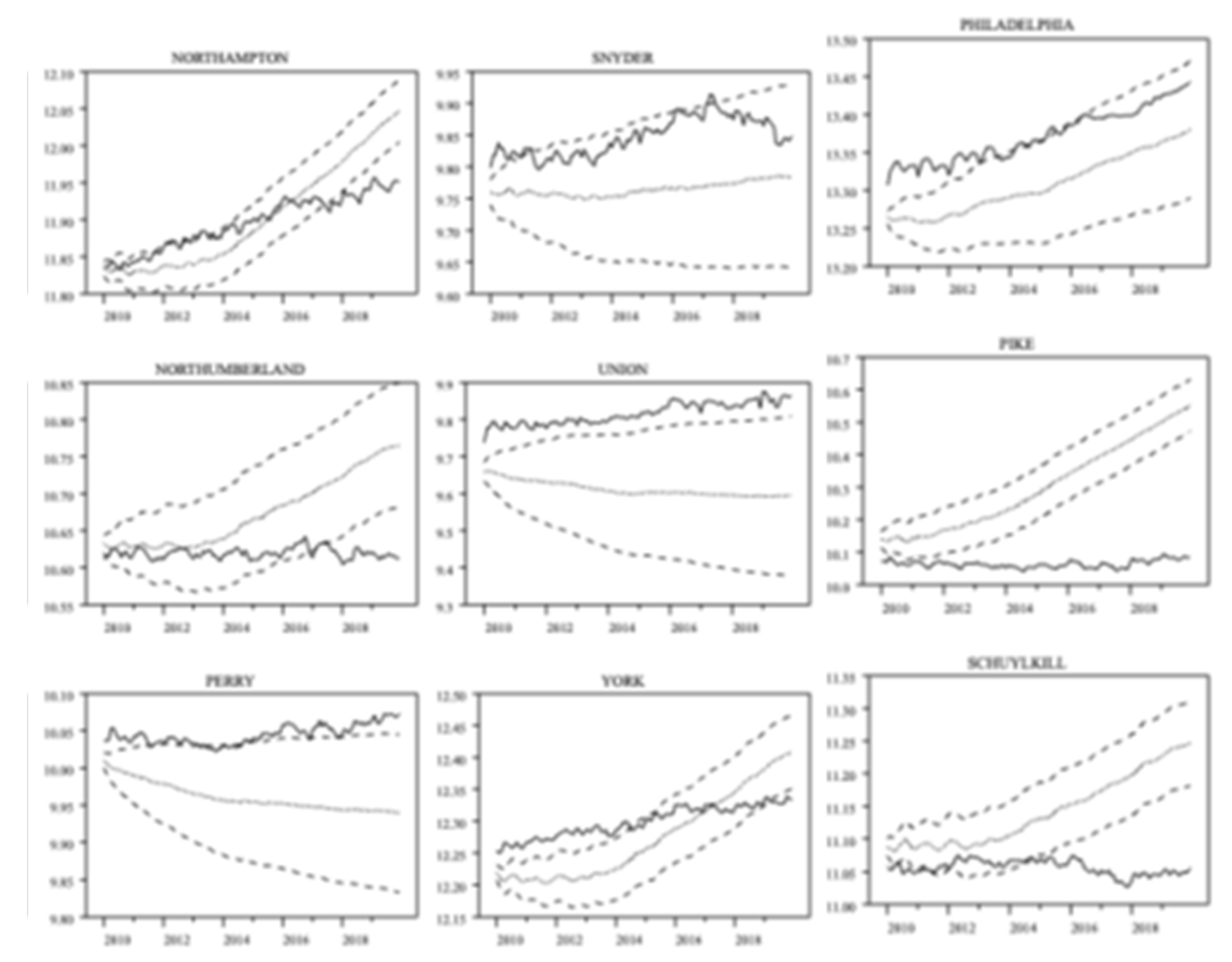

4.1. County Employment Relative to Forecast, 2010–2019

The results of the VAR models forecasted employment compared to actual employment are shown for each of the counties. To assist in seeing general patterns across the counties, these VARs are placed into bins. The 40 counties with drilling are grouped into five bins based on the total number of wells drilled reported in

Table 1: 90th, 75th–89th, 50th–74th, 25th–49th, and 1st–24th percentiles. These VARs are found in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 below. Lastly, the VARs are shown for the 27 counties with no drilling, see

Figure 8 below and

Appendix A Figure A1. To aid readers in interpreting the VAR results and related analysis,

Table 4 provides several descriptive statistics for each of the groupings. There is much more drilling activity in the top quartile of drilling counties, especially within the top decile, than in the bottom 75 percent of drilling counties, so we expect positive employment effects to be most likely found in the top quartile.

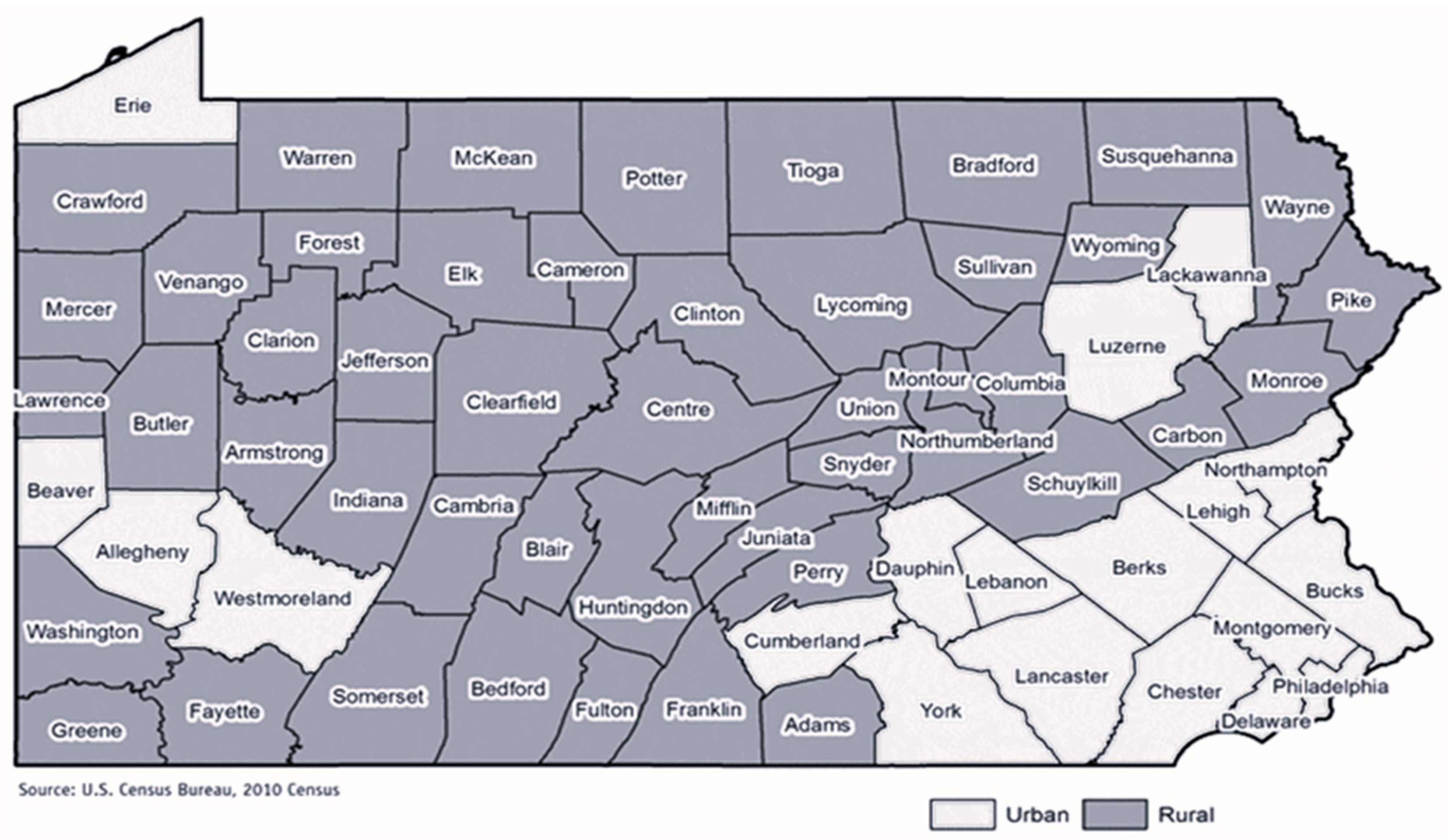

Figure 3 presents the actual time path of the log of employment for each county in the 90th percentile and above in drilling intensity (shown by the solid line) against its forecast and associated standard error bands, shown by the dashed lines. Washington county, which had the most unconventional wells developed over the relevant time period, did see employment levels consistently above forecast from around mid-2011 through the end of 2015 and saw employment above the upper standard error band from late 2011 to late 2013. Bradford and Susquehenna saw employment levels rise above the upper standard error band—briefly in 2011 for Bradford and in 2012 for Susquehenna—before ultimately falling back below forecast by 2014–2015. Greene county had employment levels well below forecast for most the months from 2010–2019, save for a three-year period from 2011–2014, in which its employment levels were above forecast, even breaking through the upper confidence band in 2012 and the first half of 2013. The results in

Figure 3, taken as a whole, do seem to paint a picture that PA counties in the upper decile of unconventional drilling activity did have employment levels above forecast, some decidedly so, for at least some of the period from 2010–2019, usually during the 2011–2014 range and more consistently for Washington county.

Figure 4 presents the same information for the counties lying in the 75th–89th percentile for unconventional drilling activity. The two most heavily drilled counties in this grouping, Tioga and Lycoming, saw employment levels relative to forecast that were perhaps even better than that seen among the top decile of counties. For at least a few years, both experienced employment numbers that were comfortably above the forecast’s upper bound, meaning we can say these levels were higher than forecast and these deviations were indeed statistically significant. For Tioga, this positive difference occurred from roughly mid-2010 through mid-2013, whereas Lycoming had a longer such stretch, running from the beginning of 2011 through early 2015. Butler’s employment stayed very close to forecast for the entire sample period. Wyoming and Westmoreland experienced employment that exceeded forecast for most of the period in question, with Westmoreland eclipsing the forecast’s upper bound from 2012–2013. Fayette’s employment stayed substantially below even the lower bound the employment forecast every month from 2010–2019.

Figure 5 presents employment levels versus forecast for the ten counties in the 50th–74th percentile for number of unconventional wells drilled. Allegheny stands out in having employment levels above forecast in a statistically significant way for essentially the entire forecast period. It should be noted that Allegheny is the county housing the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s second largest city and its urban anchor in the western part of the state. Armstrong, Elk, Cameron, and Potter saw employment eclipse the upper bound of the forecast interval for at least some portion during the first few years of the forecast horizon. Clinton and Beaver counties saw employment exceed forecast for substantial periods from 2011 to 2015 (2016 for Beaver) before falling below forecast for the latter part of the forecast period. Sullivan and McKean closely tracked their employment forecasts until 2015, when they began to lag substantially behind. Clearfield is the only county in this grouping whose actual employment levels were always below forecast for the entire 2010–2019 sample.

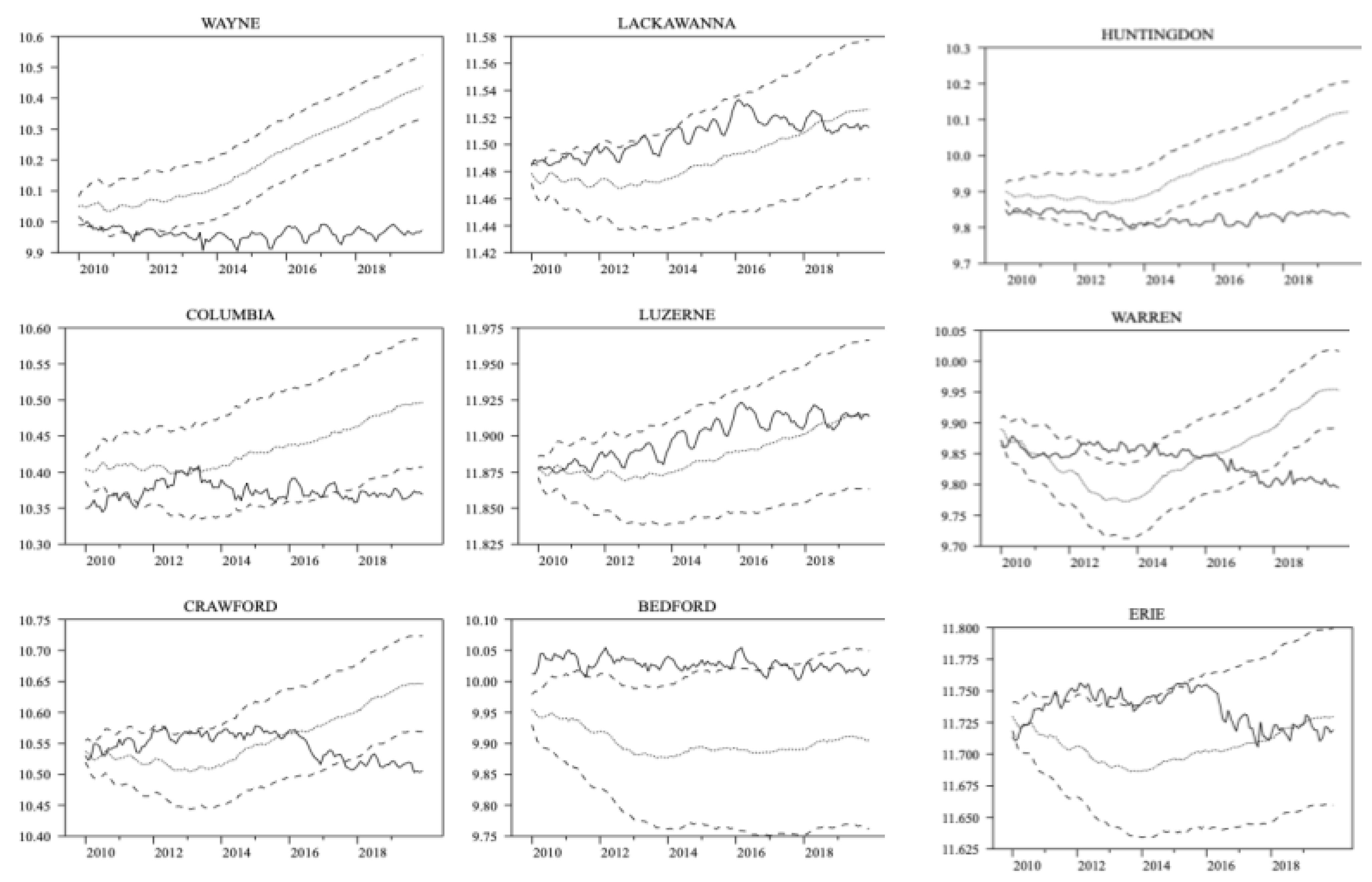

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are, of course, analogous to

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 but for the twenty counties in PA with the lowest number of unconventional wells drilled (but that did at least have one such well).

Figure 6 presents findings for the 11 counties in the 25th–49th percentile for drilling activity and

Figure 7 shows the same for the 9 counties in the 1st–24th percentile group. For all of the twenty counties combined in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, eight experienced employment levels that were consistently above forecast: Mercer, Centre, Crawford, Warren, Bedford, Luzerne, Erie, and Lackawanna. Of these eight, Mercer, Bedford, and Erie had employment levels above the upper standard error band for substantial periods of time. Nine of the remaining twelve counties had employment levels within the standard error bands for the first 4–5 years of the forecast period before falling below the lower bound for roughly the latter half of the horizon. Blair and Jefferson counties are seen to stay near their forecasts for most of the forecast period.

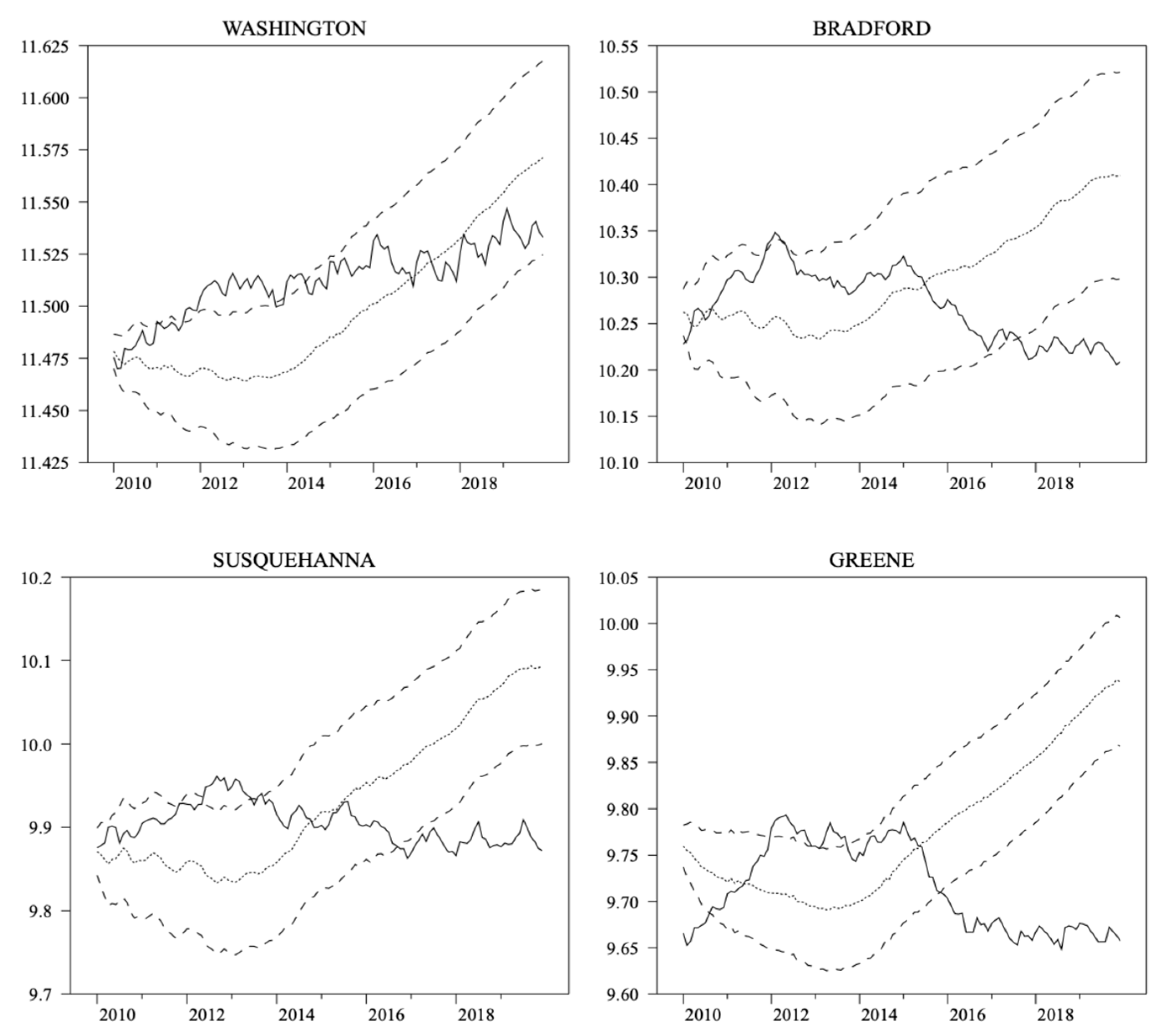

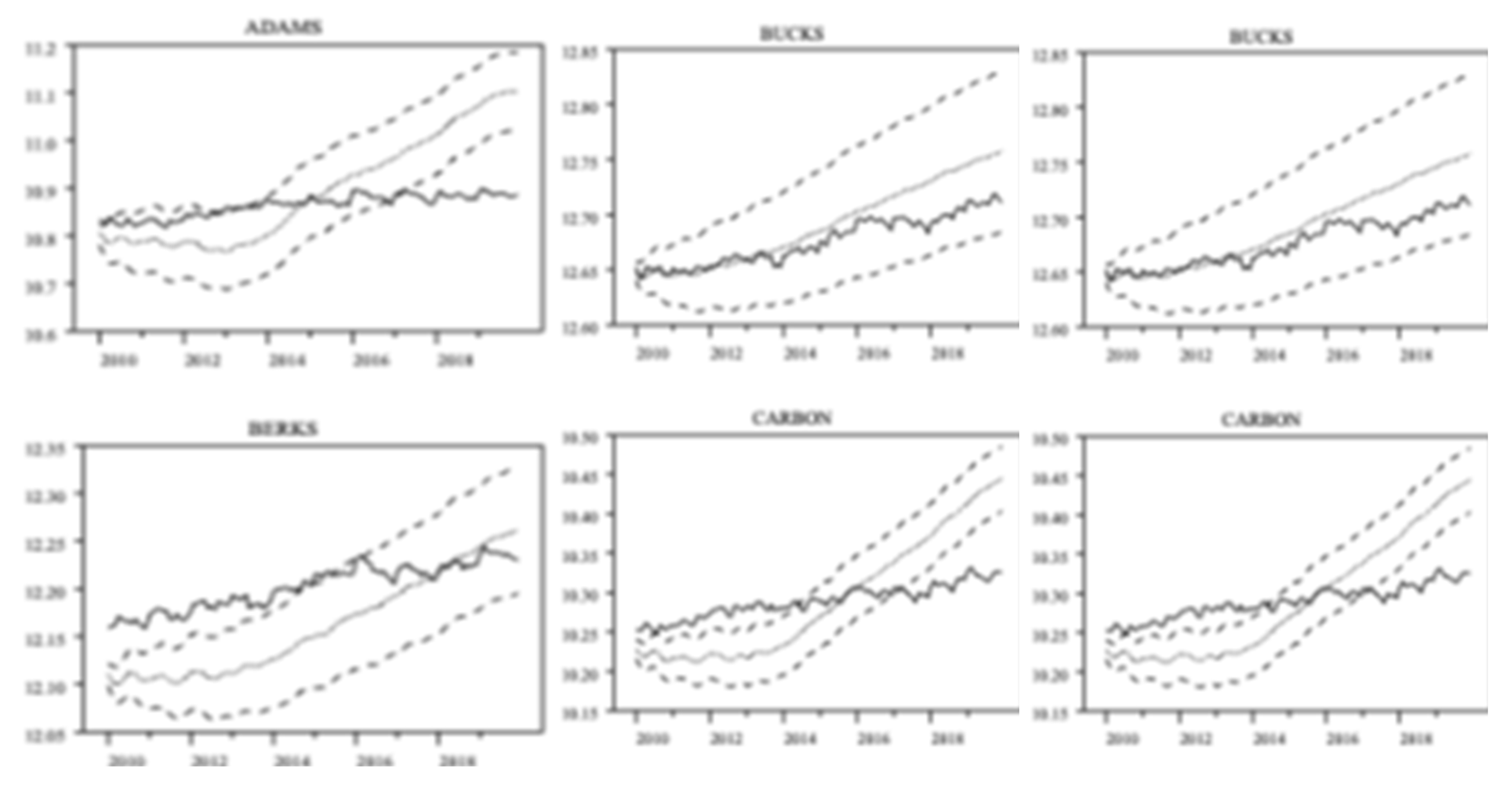

Finally,

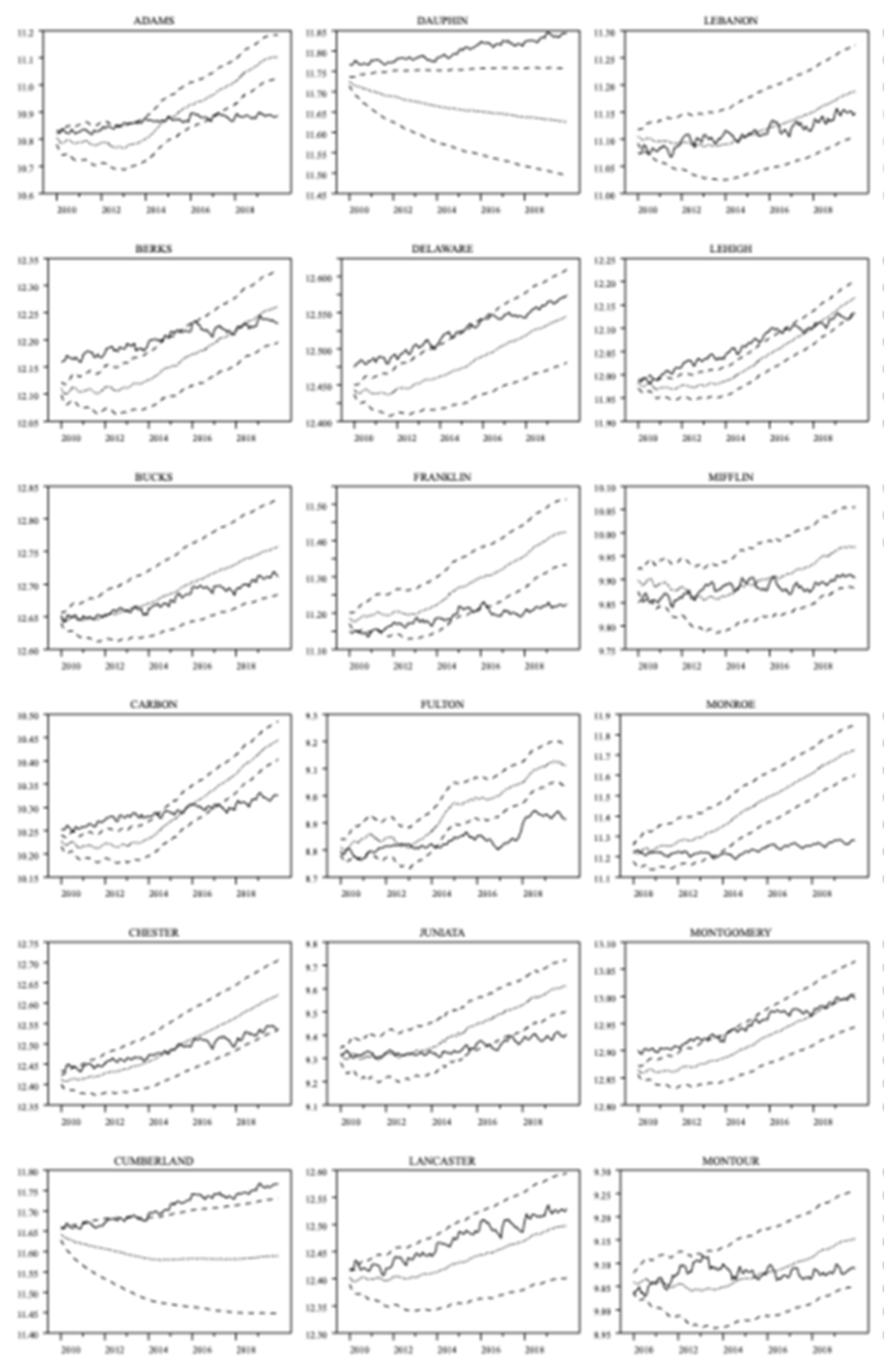

Figure 8 shows employment levels relative to forecast from 2010–2019 for 6 of the 27 counties in the state that had no drilling activity (all 27 counties shown in

Appendix A,

Figure A1). As before, a number of these counties have employment levels within the standard error bands until the latter portions of the forecast horizon. Others were seen to be above forecast for the entire sample, notably the urban counties in the southeast portion of the state: Berks, Delaware, Lehigh, and Philadelphia. The worst-performing counties relative to forecast among this group are Pike, Monroe, and Schuylkill, whose employment levels stayed consistently below forecast for the entire sample period and were often below the lower standard error band.

Figure 9 takes a portion of the information presented in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 and presents it in a different way. The results shown thus far seem to indicate that most of the positive response from the fracking boom occurs in the first few years after the increase in exploration took place. Indeed, the information presented in

Table 5 indicates that after 2014, activity in the industry within the state began to sharply decline. We see that state GDP in NAICS 211 industries (oil and natural gas extraction) decreased by over 39% from 2014 to 2015. By 2020, such activity was only 37% of what it was at its peak. Similarly, state employment in NAICS 21 decreased by over 25% from 2014 to 2015 and stayed relatively subdued. Data on state employment in NAICS 211 was unavailable over the full 2010–2020 period, so we used NAICS 21, which also includes employment in mining. Moreover,

Table 5 reports that the number of new unconventional wells drilled in the state fell by over 42% from 2014 to 2015, and by 2020, the number of new wells drilled was less than one-fourth what it was in 2011. As shown in

Figure 9, we therefore decided to focus our attention on the first five years after the fracking boom. Specifically, we took each county’s employment deviation from forecast at various horizons (6, 12, 18, 24, 30, 36, 48, and 60 months) and computed the average deviation at each time horizon for the various percentile groupings for the drilling activity reported in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 (90th and above, 75th–89th, 50th–74th, 25th–49th, 1st–24th, and ‘no drilling’). For example,

Figure 9 shows that for counties with no drilling activity, the average employment deviation from forecast at the 6-month forecast horizon (June 2010) was just under 0.02 (2%). For the counties in the 90th+ percentile for drilling activity, the average employment deviation from forecast at the 24-month forecast horizon (which would amount to January 2012) was roughly 0.065 (6.5%). If one takes ‘no-drilling’ as the benchmark, then the percentile groups that consistently had a higher average employment deviation from forecast than counties with no drilling are the counties in the top half (50th percentile and above) of unconventional drilling activity. We present the results for non-drilling counties here for comparison purposes only, which is not to say that drilling counties should be expected to match the performance of their non-drilling counterparts. There are many other differences between drilling and non-drilling counties that could alter employment dynamics, not least of which is urban/rural designation. This study addresses this issue in more detail in

Section 3.2. For the 90th percentile group and the 50th–75th percentile group, this over-performance takes place beginning at the 12-month forecast horizon. It takes until the 18-month horizon for the 75th–89th percentile group to outpace the non-drilling counties.

Figure 9 illustrates that counties in the 1st–24th and the 25th–49th percentile groups never outperformed the non-drilling benchmark at any forecast horizon within five years after the fracking boom took place. Additionally, note that the relative employment benefit to fracking clearly seems to dissipate at the four-to-five-year forecast horizon, consistent with the findings presented thus far and of those uncovered by others.

To gain further insight into the relationship between drilling activity and county employment levels relative to what would have otherwise been forecast, we next take each county and examine the extent to which its actual employment was different from forecast for both the full ten-year span from 2010–2019 and the five-year span from 2010–2014. Specifically, for each county, for the ten-year forecast horizon, there are 120 monthly observations of employment deviations from forecast. Once we have these 120 observations for a specific county, we test the null hypothesis that the average of these deviations is different from zero and obtain the associated t-statistic. We then take the average of this t-statistic for the counties in each of the aforementioned percentile groupings based on drilling intensity and report them in

Figure 10.

Figure 10 also reports similar t-statistics for the smaller 5-year forecast horizon, which is obviously based on 60 observations of employment deviations from forecast for each county.

Figure 10 shows that for the 5-year forecast horizon, every percentile group among drilling counties, save the 25th–49th percentile grouping, had positive t-statistics for this particular test, and these employment deviations were statistically significant at the 5% level. It should be noted, however, that the non-drilling group also had a positive t-statistic over this same hypothesis test and that the t-statistic for this group was actually higher than that for any of the drilling groups. For the full 10-year forecast horizon, the 75th–89th, 50th–74th, and the 1st–24th percentiles all had positive average t-statistics, but, once again, none of these values were higher than that for the non-drilling group of counties.

The results presented in

Figure 10 are consistent with the general story told by

Figure 9 and the numerous graphs of county employment level versus forecasts in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8: in terms of having actual employment levels post-fracking that were different from what would have otherwise been forecasted before the boom took place, counties that seemed to benefit from engaging in horizontal drilling were generally those in the upper half (50th percentile and above) in drilling activity in the state and that the relative employment benefit seemed to be more pronounced in the first five years of the initial increase in drilling activity. These results match those of Wrenn et al. [

19], who found that only the most intensely drilled counties in PA saw an employment increase, and Komarek [

23], who revealed that such employment benefits dissipated after three years. Recall that Jaenicke [

20] and Gittings and Roach [

21] also found modest positive employment effects from fracking in the Marcellus regions (although the response was muted when only local residents were counted in the employment numbers). Finally, these results also comport with Mayfield [

22], who illustrate that most of the employment benefits of horizontal drilling in the Appalachian Basin accrued to rural areas but that such positive effects were generally short-lived.

4.2. Further Regression Analysis

For a final examination into the impact fracking had on employment deviations from forecast in Pennsylvania, we next perform a few straightforward ordinary least squares regressions. For each regression, the dependent variable is the estimated t-statistic for each county obtained from testing the hypothesis that the county’s employment deviation from forecast was different from zero. As before, we perform this for both the shortened 5-year forecast horizon from 2010–2014 (

Table 5) and for the full 10-year forecast horizon from 2010–2019 (

Table 6). We, of course, have one such t-statistic for each county, so our sample size for each regression is

. The larger the t-statistic is for a county, the more confident we can be that the county’s employment level over the forecast period was significantly different from forecast. Of course, large negative values for the t-statistic imply employment levels far below forecast. We wish to stress that our initial goal in these regressions is not to fully explain these t-statistics. There are myriad reasons why a specific county may or may not have outperformed its employment forecast over a 5- or 10-year period, and examining and modelling these factors would make up an entirely different project. We instead wish to see just how much of the deviation in these test statistics can be explained by fracking alone. Our first model is therefore extremely straightforward:

where

is the t-statistic for county

for the test of whether the county’s employment deviation from forecast over the relevant forecast horizon (either 5 or 10 years) was statistically significant, the

are coefficients,

is a dummy variable that equals ‘1’ if county

engaged in any drilling at all and ‘0’ otherwise, and

is a Gaussian error term. The results from the estimation are presented in column ‘I’ of

Table 6 and

Table 7 (

Table 6 for the 5-year forecast horizon and

Table 7 for the full 10-year span). The results in Column I of

Table 6 and

Table 7 only tell us if a dummy indicating whether or not a county engaged in fracking activity can explain, in any meaningful way, its deviation from forecast over the specified forecast horizon. Examining the estimation results, we can see that the coefficient on the dummy variable indicating the presence of some drilling activity versus none is negative and statistically significant for both the full and shortened forecast horizons. Also, whether or not a county engaged in drilling accounted for only 9.2% of the variance in the t-statistic for whether its employment deviated from forecast over the 5-year forecast sample and only 4.7% over the full 10-year forecast span. This tells us that whether or not a county fracked or not can explain very little regarding its deviation from forecast over the specified time horizons. While the negative sign may be surprising, this simple model is surely suffering from omitted variable bias, as many other factors can influence a county’s employment relative to forecast other than simply whether or not it engaged in horizontal drilling.

The next regression model we estimate simply adds another dummy variable to the model: one that is equal to ‘1’ if the county is labeled as ‘urban’ by the Center for Rural PA or ‘0’ otherwise:

Column ‘II’ in

Table 6 and

Table 7 shows that adding the ‘urban’ dummy increases the

to 0.1912 and 0.1359 (0.1659 and 0.1088, adjusted), respectively, for the 5-year and 10-year forecast horizon models. Furthermore, the coefficient on the new variable is positive and significant at the 1% level for both forecast horizons. The coefficient estimate on the drilling dummy loses its statistical significance once urban status is accounted for, indicating that some of the negative relationship between the drilling dummy and performance against forecast was reflecting the general under-performance of rural counties relative to urban ones in the state.

Next, to account for overall drilling intensity instead of simply whether or not a county had any drilling at all, we replace

with the number of wells drilled per 100 thousand residents in the county according to the 2010 U.S. Census (

):

These results are reported in Column ‘III’ of

Table 6 and

Table 7 and once again show the strong, positive employment response a county in PA had from 2010–2019 if it was urban instead of rural. The coefficient on drilling intensity is positive and statistically significant at the 10% level if only the first 5 years of the forecast horizon are analyzed. For the full 10-year horizon, the coefficient is positive but not statistically different from zero. These results indicate a modest but positive impact on employment deviations from forecast from increased drilling activity. As noted in

Table 6’s heading, heteroskedasticity was detected in Equation (3)’s (as well as Equation (4)’s) specification, so White-heteroskedasticity-consistent standard errors were calculated. The low

s in these models underscore that only a small percentage of the variation in the dependent variable is accounted for by only drilling activity and urban/rural status, so clearly there are other factors that played a role in these employment deviations from forecast.

Finally, we add one more variable to the analysis that may be able to proxy for many exogenous factors that can influence whether or not a county outperformed its employment forecast: the county’s percentage change in its population over the 2010–2019 forecast horizon (reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2). The rationale is that if a county was experiencing population growth over this span, it may have been benefiting from some other outside factor that would have impacted its employment deviation. If its population shrunk over this span, it could have been suffering from some other negative factor that would have caused its employment to under-perform relative to forecast. Note that this approach is much more straightforward that that taken by researchers such as Cutler et al. [

38], who use cointegration analysis to uncover underlying similarities between regional industry structures. This would allow for a potentially more informative control variable, but we leave such an exercise to future research. This new model is spelled out in Equation (6) and allows us to examine the extent to which drilling intensity increased employment relative to forecast when accounting for a county’s overall population change.

The estimation results when OLS is applied to Equation (6) can be found in Column IV of

Table 6 and

Table 7. One can see that when the shortened forecast horizon (

Table 6) is utilized, drilling intensity is now positive and statistically significant at the 5% level. Urban status is still seen to impart a positive employment effect relative to forecast, but this impact is relatively lower once overall population growth is accounted for. There, of course, could be a degree of collinearity in play here, as the correlation between population growth and urban status is 0.684. When the full 10-year forecast horizon is analyzed, however, drilling intensity remains statistically insignificant, lending further evidence to the claim that any positive employment benefit from fracking tends to dissipate after 4–5 years.

While we are clearly not accounting for the myriad factors that may explain why counties may have had employment levels that were different from forecast from 2010–2019, we can use the results in Column ‘IV’ in

Table 7 to perform a simple thought experiment. To be at least 95% sure a county had employment levels that were greater than forecast, one would need to see its t-statistic be 1.96. The results above reveal that an urban county with no drilling and a stable population would have a predicted t-statistic of

, clearly above that needed for a

p-value of 0.05. How about for a rural county? Our results indicate that each well drilled per one hundred thousand residents would raise the t-statistic by 0.002 (ignoring, for the moment, that this coefficient is not statistically significant from zero for when the full 10-year forecast horizon is employed). This finding means that a rural county with a stable population would have needed 1433 wells drilled per one hundred thousand residents to have a t-statistic of 1.96. This would have placed it 7th out of 40 drilling counties in wells drilled per one hundred thousand residents, further illustrating that only counties with very extensive drilling activity could have expected employment levels that were greater than would have otherwise been predicted had the fracking boom never taken place.

4.3. Limitations and Potential Future Research

This study’s use of parsimoneous VAR models allowing for lag structures unique to each county permits the labor market dynamics to vary across each county and examining the pattern of forecasted employment to actual employment across counties by their drilling activity is informative. The need for estimating and analyzing 67 separate VARs, however, limits the practicality of running several different versions of the VAR model for each county. One potentially fruitful area for future research using VAR models of employment would be to first restrict the analysis to just the counties with the most drilling activity. For these counties, a variety of VAR models could be employed, such as county-level controls related to age–structure, educational attainment, and industry composition; and macro-level controls, such as interest rates, consumer confidence, producer confidence, or national labor market variables. Alternatively, multiple contiguous counties with active drilling could be combined into a single VAR model that tests for spillover employment effects across counties from drilling.

Another approach would be to restrict the initial base period to end five years earlier in December 2004 and then forecast employment from 2005–2010, halting just before the drilling boom commenced in Pennsylvania. These “pre-boom” forecasts could be compared against actual employment and the results compared to those found in this paper. With regards to interpretation of the findings in this paper, a possible limitation is that no formal corrections are made for multiple testing adjustments for reported

p-values. Fortunately, the pattern of which drilling counties ever show actual employment above the 95% confidence upper bound is unlikely to be materially impacted by Type-I errors. With 40 drilling counties, we can expect that two counties (0.05 × 40) falsely show actual employment above forecasted. Even if these two random outcomes happened to counties most actively drilled, it would not alter our main findings. First, drilling counties that ever showed actual employment above forecasted were more prevalent in high-drilling counties. Reviewing

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, seven of the ten counties with the most wells drilled had actual employment that exceeded forecast at some point, while only nine of the thirty remaining drilling counties had this result. Attributing two of the seven most drilled counties to Type-I error does not alter this pattern. Additionally, these types of Type-I errors are unlikely to impact the strong pattern that nearly all the positive employment effects dissipate within five years.