Breaking Barriers to Sustainable and Decent Jobs: How Do Different Regulatory Areas Shape Informal Employment for Persons with Disabilities Under SDG 8?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

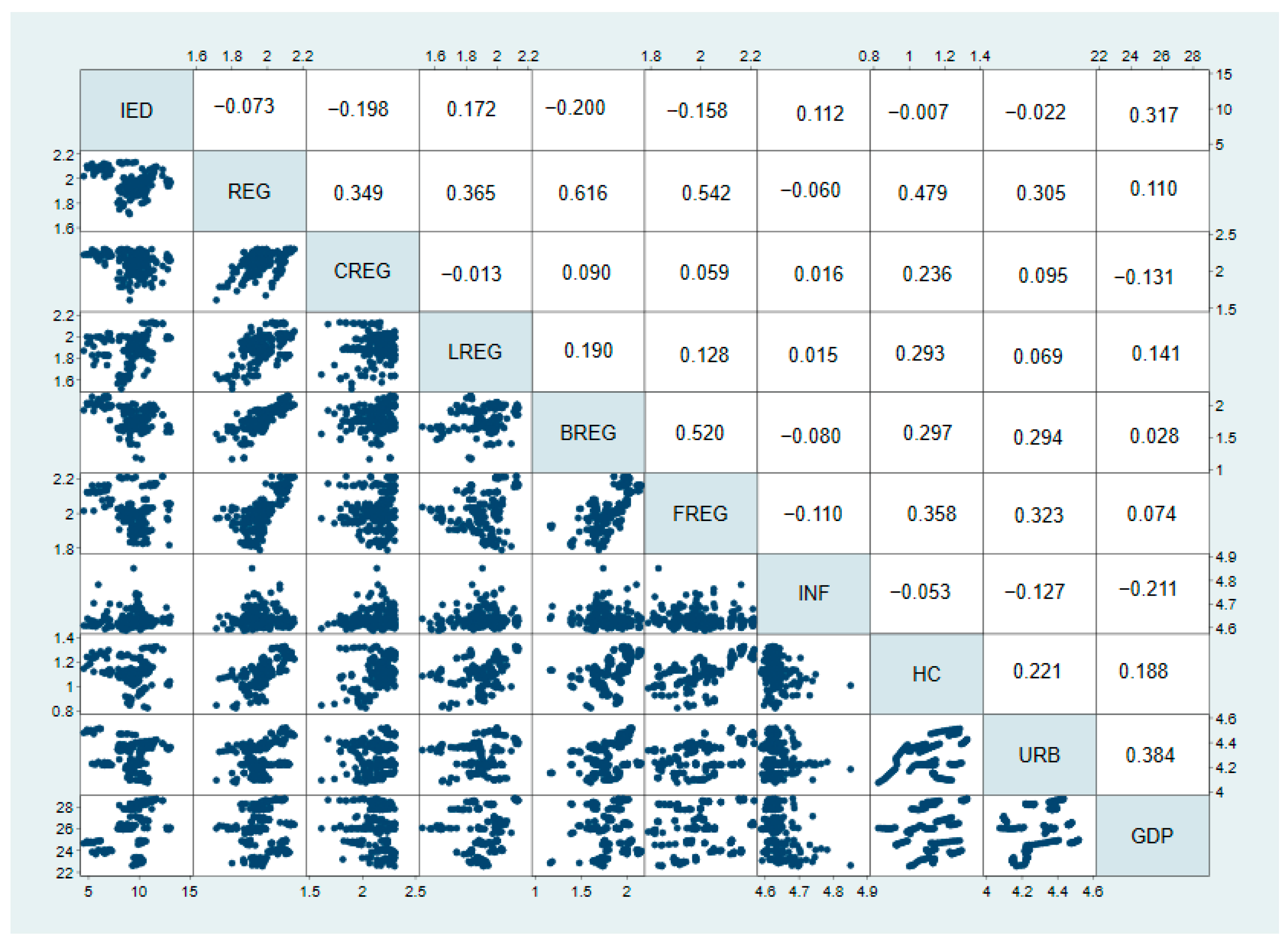

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Model Specification

- Model 1: Aggregate regulation

- Model 2: Credit market regulation

- Model 3: Labor market regulation

- Model 4: Business regulation

- Model 5: Freedom to compete

3.3. Econometric Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Regulation and Aggregate Informal Employment of PWDs

4.2. Regulation and Informal Employment of PWDs by Age Cohort

4.3. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of the Findings

6.2. Policy Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Area of Regulation | Components |

|---|---|

| A. Credit market regulation | Ownership of banks |

| Private sector credit | |

| Interest rate controls/negative real interest rates | |

| B. Labor market regulation | Labor regulations and minimum wage |

| Hiring and firing regulations | |

| Flexible wage determination | |

| Hours’ regulation | |

| Costs of worker dismissal | |

| Conscription | |

| Foreign labor | |

| C. Business regulation | Regulatory burden |

| Bureaucracy costs | |

| Impartial public administration | |

| Tax compliance | |

| D. Freedom to compete | Market openness |

| Business permits | |

| Distortion of business environment |

References

- Berghs, M.; Dyson, S.M. Intersectionality and employment in the United Kingdom: Where are all the Black disabled people? Disabil. Soc. 2022, 37, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinta, N.; Kolanisi, U. Overcoming barriers for people with disabilities participating in income-generating activities: A proposed development framework. Afr. J. Disabil. 2023, 12, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, B. Intersectionality of gender, race, class, sexuality, disability and other social identities in shaping the experiences and opportunities of marginalized groups in Ukraine. Int. J. Gend. Stud. 2024, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Ch_IV_15.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Santilli, S.; Ginevra, M.C.; Nota, L.; Soresi, S. Decent work and social inclusion for people with disability and vulnerability: From the soft skills to the involvement of the context. In Interventions in Career Design and Education; Cohen-Scali, V., Pouyaud, J., Podgórny, M., Drabik-Podgórna, V., Aisenson, G., Bernaud, J.L., Abdou Moumoula, I., Guichard, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, D.L.; Henly, M. Job quality for Americans with disabilities. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2019, 50, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, R.; Li, S. Smart nations for all, disability and jobs: A global perspective. J. Knowl. Econ. 2022, 13, 1635–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuoka, F. Disability and Employment: Towards a Humanistic Economy; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. New ILO Database Highlights Labour Market Challenges of Persons with Disabilities. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/blog/new-ilo-database-highlights-labour-market-challenges-of-persons-with-disabilities (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics Summary. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.nr0.htm (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- World Bank. Disability Inclusion. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/disability (accessed on 18 February 2025).

- Lecerf, M. Employment and Disability in the European Union; European Parliament: Strasbourg, France, 2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/651932/EPRS_BRI(2020)651932_EN.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- International Labour Organization. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/Women_men_informal_economy_statistical_picture.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- OECD/ILO. Tackling Vulnerability in the Informal Economy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/tackling-vulnerability-informal-economy (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Linh, B.K. Vulnerability of the informal sector in an emerging economy: A multi-level analysis. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 2024, 39, 74–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimatussadiah, D.A.; Nuryakin, C. Mapping persons with disabilities (PWDs) in Indonesia labor market. Econ. Financ. Indones. 2017, 63, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizunoya, S.; Mitra, S. Is there a disability gap in employment rates in developing countries? World Dev. 2013, 42, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemma, T.; Sharma, M. Socioeconomic advancement of women in the informal sector in Hosanna City, Ethiopia. Cities 2025, 156, 105580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.R.; Behera, D.K. Barriers to women’s empowerment in India’s informal sector: Structural and socio-economic constraints. Discover Sustain. 2025, 6, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, G.; Urrutia, C. Informality, labor regulation, and the business cycle. J. Int. Econ. 2020, 126, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deléchat, C.; Medina, L. The Global Informal Workforce: Priorities for Inclusive Growth; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, C.; Papaccio, A. Does Regulatory Quality Reduce Informal Economy? A Theoretical and Empirical Framework. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 172, 543–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpur, P.; Blanck, P. Gig workers with disabilities: Opportunities, challenges, and regulatory response. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2020, 30, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulyssea, G. Regulation of entry, labor market institutions and the informal sector. J. Dev. Econ. 2010, 91, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, Y.; Kovalenko, K.; Kovalenko, N. Regulación legal del emprendimiento de personas con discapacidad. Dilemas Contemp. Educ. Política Y Valores 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerud, K.L.; Vedeler, J.S. Disability and regulatory approaches to employer engagement: Cross-national challenges in bridging the gap between motivation and hiring practice. Soc. Policy Soc. 2024, 23, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’erasmo, P.N. Access to credit and the size of the formal sector. Economía 2016, 16, 143–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Salha, O.; Zmami, M. The effect of economic growth on employment in GCC countries. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2021, 68, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liotti, G. Labour market regulation and youth unemployment in the EU-28. Ital. Econ. J. 2022, 8, 77–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, N.F.; Nugent, J.B.; Zhang, Z. Labor Market Regulations and Female Labor Force Participation. In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics; Zimmermann, K.F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Salha, O.; Mrabet, Z. Is economic growth really jobless? Empirical evidence from North Africa. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2019, 61, 598–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bezooijen, E.; van den Berge, W.; Salomons, A. The young bunch: Youth minimum wages and labor market outcomes. ILR Rev. 2024, 77, 428–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, P.C. Toward a theory of the informal economy. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 231–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, R.M., Jr.; Miller, T.; Hitt, M.A.; Salmador, M.P. The interrelationships among informal institutions, formal institutions, and inward foreign direct investment. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 531–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Salha, O.; Zmami, M. Does the business climate affect private domestic and foreign investment? Empirical evidence from the MENA region. Ann. Financ. Econ. 2019, 14, 1950020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vornholt, K.; Villotti, P.; Muschalla, B.; Bauer, J.; Colella, A.; Zijlstra, F.; Corbière, M. Disability and employment–overview and highlights. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Iwanaga, K.; Grenawalt, T.; Mpofu, N.; Chan, F.; Lee, B.; Tansey, T. Employer Practices for Integrating People with Disabilities into the Workplace: A Scoping Review. Rehabil. Res. Policy Educ. 2023, 37, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.J. The impact of legislation and conventions on disability employment outcomes in Australia. Adv. Neurodev. Disord. 2024, 8, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla-Roncancio, M.; Rodríguez Caicedo, N. Legislation on disability and employment: To what extent are employment rights guaranteed for persons with disabilities? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schur, L.; Han, K.; Kim, A.; Ameri, M.; Blanck, P.; Kruse, D. Disability at work: A look back and forward. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2017, 27, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Disability and Development Report 2024; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4504319 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Darbi, W.P.K.; Hall, C.M.; Knott, P. The informal sector: A review and agenda for management research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Li, P. Employment legal framework for persons with disabilities in China: Effectiveness and reasons. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, D.; Schur, L. Employment of people with disabilities following the ADA. Ind. Relat. 2003, 42, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroto, M.; Pettinicchio, D. The limitations of disability antidiscrimination legislation: Policymaking and the economic well-being of people with disabilities. Law Policy 2014, 36, 370–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szerman, C. The Labor Market Effects of Disability Hiring Quotas. SSRN 4267622, 2022. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4267622 (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Matsumoto, K. Impact sourcing for employment of persons with disabilities. Soc. Enterp. J. 2020, 16, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandratilaka, M.A.N. Impact of legal and policy framework governing organizational practices on employment of Sri Lankans with disabilities. Sri Lankan J. Bus. Econ. 2023, 12, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichner, T.; Cologna, A.; Cvilak, L.; Zacca, R. Exploring the Challenges and Opportunities of Employing Persons with Disabilities. F1000Research 2024, 13, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Baek, Y.; Sohn, H. The effects of mandatory quota policy on employment of disabled workers in Korea: A regression discontinuity design approach. J. Asian Public Policy 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlinski, S.G.; Gagete-Miranda, J. Enforcement spillovers under different networks: The case of quotas for persons with disabilities in Brazil. J. Dev. Econ. 2025, 176, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Indicators. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Feenstra, R.C.; Inklaar, R.; Timmer, M.P. The Next Generation of the Penn World Table. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 3150–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltagi, B.H. Econometric Analysis of Panel Data, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005; Available online: https://library.wbi.ac.id/repository/27.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Meschi, E.; Taymaz, E.; Vivarelli, M. Trade, technology and skills: Evidence from Turkish microdata. Labour Econ. 2011, 18, S60–S70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Salha, O. Does economic globalization affect the level and volatility of labor demand by skill? New insights from the Tunisian manufacturing industries. Econ. Syst. 2013, 37, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmami, M.; Ben-Salha, O. Exchange rate movements and manufacturing employment in Tunisia: Do different categories of firms react similarly? Econ. Change Restruct. 2015, 48, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M. Does economic, financial and institutional developments matter for environmental quality? A comparative analysis of EU and MEA countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J. 2009, 9, 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Ben-Salha, O.; Gasmi, K.; Alnor, N.H.A. Modelling for disability: How does artificial intelligence affect unemployment among people with disability? An empirical analysis of linear and nonlinear effects. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2024, 149, 104732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Ben-Salha, O.; Gasmi, K.; Alnor, N.H.A. The impact of artificial intelligence on unemployment among educated people with disabilities: An empirical analysis. J. Disabil. Res. 2024, 3, 20240008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artieda, L.; Allan, M.; Cruz, R.; Shah, S.; Pineda, V.S. Access and Persons with Disabilities in Urban Areas; Institute for Transportation & Development Policy: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://itdp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Full-Report-jun21.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Lindstrom, L.; Kahn, L.G.; Lindsey, H. Navigating the early career years: Barriers and strategies for young adults with disabilities. J. Vocat. Rehabil. 2013, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abille, A.B.; Meçik, O. Macro-determinants of current account balance performance in selected African countries. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2024, 26, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.F.; Singer, D. Financial Inclusion and Legal Discrimination Against Women: Evidence from Developing Countries; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; No. 6416; Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2254240 (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S. Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19; World Bank Report; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099818107072234182/pdf/IDU06a834fe908933040670a6560f44e3f4d35b7.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- D’Aguilar, A. Young Adults with Disabilities Financial Skills and Goals: A Mixed Methods Strengths and Needs Assessment. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiya, A.N.; Opoku, M.P.; Nketsia, W.; Dogbe, J.A.; Adusei, J.N. Achieving financial inclusion for persons with disabilities: Exploring preparedness and accessibility of financial services for persons with disabilities in Malawi. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2022, 33, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Porto, E.; Elia, L.; Tealdi, C. Informal work in a flexible labour market. Oxford Econ. Pap. 2016, 69, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Verdugo, L.E.; Furceri, D.; Guillaume, D. Labor market flexibility and unemployment: New empirical evidence of static and dynamic effects. Comp. Econ. Stud. 2012, 54, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, J.; Assaad, R. Flexible labor regulations and informality in Egypt. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2017, 21, 962–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I. Labor market flexibility and unemployment: A study of the United States. Int. J. Econ. 2024, 9, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, Z.; Kwan, L.Z.; Shu Shin, L. Unraveling the threads: A comprehensive analysis of government policies on unemployment, worker empowerment, and labor market dynamics. Law Econ. 2022, 16, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akande, R.S.; Kareem, H.K.A.; Sulaimon, T.T. Gender, regulation efficiency and informal employment in Sub-Saharan Africa. Pak. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Buehn, A.; Montenegro, C.E. New estimates for the shadow economies all over the world. Int. Econ. J. 2010, 24, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweidan, O. Economic freedom and the informal economy. Glob. Econ. J. 2017, 17, 20170002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, J.G. Labour market participation for young people with disabilities: The impact of gender and higher education. Work Employ. Soc. 2020, 34, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, R.; Keskin, A.; Keskin, A. The impact of economic growth, unemployment and inflation on informal employment in Turkey: An ARDL bounds test approach. J. Soc. Policy Conf. 2021, 80, 451–474. [Google Scholar]

- Pollin, R.; wa Gĩthĩnji, M.; Heintz, J. An Employment-Targeted Economic Program for Kenya; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwartney, J.; Lawson, R.; Murphy, R. Economic Freedom of the World, 2024 Annual Report; Fraser Institute: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Abb. | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||||

| Informal employment of persons with disabilities | IED | 9.363 | 1.772 | 4.532 | 13.092 |

| Informal employment of youth with disabilities | IED15–24 | 7.173 | 1.820 | 0.000 | 10.813 |

| Informal employment of adults with disabilities | IED25+ | 9.331 | 1.743 | 4.532 | 13.000 |

| Regulation | |||||

| Aggregate regulation index | REG | 1.981 | 0.090 | 1.711 | 2.152 |

| Credit market regulation index | CREG | 2.140 | 0.138 | 1.612 | 2.302 |

| Labor market regulation index | LREG | 1.907 | 0.123 | 1.518 | 2.135 |

| Business regulation index | BREG | 1.812 | 0.186 | 1.161 | 2.155 |

| Freedom to enter markets and compete | FREG | 2.014 | 0.116 | 1.788 | 2.214 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gross domestic product | GDP | 25.886 | 1.860 | 22.556 | 28.797 |

| Inflation rate | INF | 4.635 | 0.035 | 4.587 | 4.851 |

| Urbanization rate | URB | 4.297 | 0.119 | 4.073 | 4.520 |

| Human capital | HC | 1.118 | 0.117 | 0.824 | 1.328 |

| Dep. Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIF | IED | 1.55 | 1.28 | 1.33 | 1.31 | 1.49 |

| IED15–24 | 1.81 | 1.29 | 1.40 | 1.40 | 1.63 | |

| IED25+ | 1.54 | 1.27 | 1.34 | 1.31 | 1.49 | |

| Tolerance | IED | 0.64 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.67 |

| IED15–24 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.61 | |

| IED25+ | 0.47 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.67 |

| Variables | MODEL 1 | MODEL 2 | MODEL 3 | MODEL 4 | MODEL 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | |

| IETt−1 | 0.461 *** | 0.505 *** | 0.327 * | 0.448 ** | 0.394 ** |

| (0.178) | (0.175) | (0.204) | (0.207) | (0.189) | |

| INF | 6.448 ** | 6.320 ** | 6.523 ** | 5.881 ** | 6.605 ** |

| (2.782) | (2.825) | (2.627) | (2.816) | (2.737) | |

| HC | 0.322 | 0.109 | −2.347 *** | 0.178 | −0.030 |

| (0.416) | (0.426) | (0.859) | (0.352) | (0.425) | |

| GDP | 0.213 ** | 0.188 ** | 0.249 *** | 0.218 ** | 0.239 *** |

| (0.085) | (0.084) | (0.090) | (0.096) | (0.089) | |

| URB | −1.001 ** | −1.064 ** | −0.927 ** | −0.742 * | −0.852 * |

| (0.488) | (0.528) | (0.465) | (0.431) | (0.495) | |

| REG | −1.526 ** | - | - | - | - |

| (0.777) | |||||

| CREG | - | −0.867 ** | - | - | - |

| (0.338) | |||||

| LREG | - | - | 2.928 *** | - | - |

| (0.755) | |||||

| BREG | - | - | - | −1.360 * | - |

| (0.699) | |||||

| FREG | - | - | - | - | −1.417 *** |

| (0.542) | |||||

| Constant | −23.363 ** | −23.179 * | −29.245 ** | −22.237 * | −24.543 ** |

| (11.520) | (11.880) | (11.828) | (11.869) | (11.539) | |

| AR (1) test | 0.020 | 0.017 | 0.067 | 0.020 | 0.035 |

| AR (2) test | 0.741 | 0.800 | 0.531 | 0.748 | 0.635 |

| Sargan test | 0.525 | 0.507 | 0.484 | 0.418 | 0.474 |

| Variables | Youth | Adult | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | |

| IETt−1 | −0.406 (0.275) | −0.224 (0.265) | −0.081 (0.336) | −0.311 (0.394) | −0.199 (0.358) | 0.479 ** (0.194) | 0.530 *** (0.191) | 0.439 ** (0.215) | 0.447 ** (0.223) | 0.347 (0.250) |

| INF | 15.120 *** (3.177) | 17.424 *** (3.964) | 12.025 *** (3.728) | 16.359 *** (4.249) | 16.632 *** (4.160) | 8.415 *** (3.028) | 8.256 *** (3.079) | 7.266 *** (2.810) | 8.010 *** (2.975) | 9.828 *** (3.534) |

| HC | −7.978 *** (2.184) | −4.436 *** (1.201) | −6.188 *** (2.002) | −3.608 *** (1.377) | −7.570 *** (2.317) | 0.649 (0.402) | 0.452 (0.386) | −1.329 * (0.776) | 0.415 (0.332) | 0.088 (0.424) |

| GDP | 0.526 *** (0.088) | 0.477 *** (0.089) | 0.344 *** (0.076) | 0.515 *** (0.120) | 0.502 *** (0.118) | 0.196 ** (0.087) | 0.169 * (0.086) | 0.198 ** (0.093) | 0.211 ** (0.099) | 0.256 ** (0.113) |

| URB | 2.759 ** (1.123) | 3.047 ** (1.336) | 2.824 * (1.703) | 4.745 ** (2.077) | −0.354 (1.144) | −1.149 ** (0.558) | −1.171 * (0.605) | −1.001 * (0.551) | −0.991 ** (0.493) | −1.373 ** (0.680) |

| REG | 6.119 ** (3.008) | - | - | - | - | −1.427 * (0.806) | - | - | - | - |

| CREG | - | −0.695 (0.709) | - | - | - | - | −0.833 ** (0.345) | - | - | - |

| LREG | - | - | 6.067 ** (2.558) | - | - | - | - | 2.034 *** (0.695) | - | - |

| BREG | - | - | - | −2.432 ** (0.988) | - | - | - | - | −1.166 * (0.703) | - |

| FREG | - | - | - | - | 6.407 ** (2.561) | - | - | - | - | −0.856 * (0.509) |

| Constant | −87.863 *** (17.509) | −90.336 *** (20.976) | −73.272 *** (21.048) | −91.081 *** (24.511) | −83.659 *** (22.421) | −32.100 *** (12.228) | −31.871 ** (12.645) | −31.541 ** (12.300) | −31.436 ** (12.245) | −38.461 *** (14.242) |

| AR (1) test | 0.296 | 0.801 | 0.898 | 0.682 | 0.705 | 0.018 | 0.014 | 0.030 | 0.022 | 0.100 |

| AR (2) test | 0.012 | 0.103 | 0.051 | 0.039 | 0.100 | 0.811 | 0.896 | 0.731 | 0.793 | 0.647 |

| Sargan test | 0.216 | 0.101 | 0.139 | 0.388 | 0.298 | 0.459 | 0.423 | 0.479 | 0.427 | 0.620 |

| Panel A. Aggregate Population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | |||||

| INF | 13.771 *** (3.416) | 14.722 *** (3.389) | 9.595 *** (2.803) | 11.680 *** (3.194) | 12.445 *** (3.420) | |||||

| HC | 1.469 * (0.856) | 1.110 (0.788) | −2.926 *** (0.849) | 1.019 * (0.545) | 0.801 (0.646) | |||||

| GDP | 0.534 *** (0.061) | 0.517 *** (0.060) | 0.481 *** (0.058) | 0.515 *** (0.059) | 0.555 *** (0.061) | |||||

| URB | −2.456 *** (0.633) | −2.656 *** (0.547) | −2.435 *** (0.451) | −2.428 *** (0.632) | −2.472 *** (0.651) | |||||

| REG | −2.559 * (1.342) | - | - | - | - | |||||

| CREG | - | −1.716 *** (0.650) | - | - | - | |||||

| LREG | - | - | 3.466 *** (0.583) | - | - | |||||

| BREG | - | - | - | −2.503 *** (0.531) | - | |||||

| FREG | - | - | - | - | −1.816 * (0.972) | |||||

| Constant | −54.332 *** (16.872) | −58.435 *** (16.636) | −40.353 *** (13.775) | −44.353 *** (15.649) | −49.373 *** (16.856) | |||||

| Panel B. Population by Age Group | ||||||||||

| Variables | Youth | Adult | ||||||||

| REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | REG | CREG | LREG | BREG | FREG | |

| INF | 12.955 *** (3.390) | 14.189 *** (3.283) | 10.956 *** (2.909) | 13.544 *** (3.299) | 12.552 *** (3.346) | 14.353 *** (3.366) | 15.185 *** (3.312) | 10.263 *** (2.776) | 12.598 *** (3.152) | 13.278 *** (3.397) |

| HC | −2.172 (1.355) | −2.361 *** (0.868) | −4.190 *** (0.794) | −2.134 ** (0.925) | −1.921 (1.217) | 1.424 * (0.828) | 1.067 (0.756) | −2.724 *** (0.828) | 0.893 * (0.527) | 0.711 (0.648) |

| GDP | 0.346 *** (0.056) | 0.366 *** (0.054) | 0.381 *** (0.056) | 0.385 *** (0.057) | 0.334 *** (0.058) | 0.548 *** (0.060) | 0.531 *** (0.058) | 0.506 *** (0.057) | 0.540 *** (0.057) | 0.571 *** (0.060) |

| URB | 2.519 ** (1.012) | 2.229 ** (0.963) | 2.780 *** (0.948) | 3.368 *** (1.015) | 2.615 ** (1.171) | −2.589 *** (0.613) | −2.809 *** (0.517) | −2.704 *** (0.426) | −2.527 *** (0.601) | −2.743 *** (0.636) |

| REG | −0.471 (2.144) | - | - | - | - | −2.586 ** (1.300) | - | - | - | - |

| CREG | - | −0.398 (0.508) | - | - | - | - | −1.712 *** (0.630) | - | - | - |

| LREG | - | - | 4.560 *** (0.982) | - | - | - | - | 3.100 *** (0.551) | - | - |

| BREG | - | - | - | −1.600 ** (0.695) | - | - | - | - | −2.520 *** (0.514) | - |

| FREG | - | - | - | - | −0.948 (1.604) | - | - | - | - | −1.652 * (0.943) |

| Constant | −69.197 *** (16.998) | −74.075 *** (16.808) | −69.345 *** (15.177) | −74.738 *** (16.781) | −66.777 *** (17.213) | −56.777 *** (16.619) | −60.305 *** (16.260) | −42.566 *** (13.612) | −48.728 *** (15.431) | −53.189 *** (16.710) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben-Salha, O.; Abid, M.; Alnor, N.H.A.; Gheraia, Z. Breaking Barriers to Sustainable and Decent Jobs: How Do Different Regulatory Areas Shape Informal Employment for Persons with Disabilities Under SDG 8? Sustainability 2025, 17, 9727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219727

Ben-Salha O, Abid M, Alnor NHA, Gheraia Z. Breaking Barriers to Sustainable and Decent Jobs: How Do Different Regulatory Areas Shape Informal Employment for Persons with Disabilities Under SDG 8? Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219727

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen-Salha, Ousama, Mehdi Abid, Nasareldeen Hamed Ahmed Alnor, and Zouheyr Gheraia. 2025. "Breaking Barriers to Sustainable and Decent Jobs: How Do Different Regulatory Areas Shape Informal Employment for Persons with Disabilities Under SDG 8?" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219727

APA StyleBen-Salha, O., Abid, M., Alnor, N. H. A., & Gheraia, Z. (2025). Breaking Barriers to Sustainable and Decent Jobs: How Do Different Regulatory Areas Shape Informal Employment for Persons with Disabilities Under SDG 8? Sustainability, 17(21), 9727. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219727