1. Introduction

The development of local leadership competencies in Ecuador represents a multidimensional challenge that spans sociopolitical, educational, and institutional domains. Over the past decade, decentralization in Latin America, particularly in Ecuador, has expanded the autonomy of local governments, placing greater demands on territorial leadership capacities. Yet, disparities in institutional resources and capacities across regions have created unequal conditions for leadership development and performance.

Previous studies in Ecuador have examined leadership in diverse domains such as the civil service [

1], school management [

2], and community organizations [

3]. These analyses consistently highlight competencies such as strategic vision, communication, adaptability, and teamwork as critical to organizational effectiveness [

4,

5]. However, most of this research remains sector-specific and fragmented, offering limited insights into the broader landscape of municipal or decentralized governance.

Local leadership is also shaped by territorial inequalities. Urban leaders generally benefit from stronger institutional support and better access to formal training programs, while rural leaders often depend on community legitimacy and informal governance structures. This divide underscores the importance of understanding leadership competencies not only as individual attributes but also as outcomes of institutional and contextual interactions.

To illustrate the scope of previous research,

Table 1 summarizes representative studies on leadership competencies in Latin America. These works employ a variety of methodological approaches—ranging from participatory learning frameworks to systematic reviews—but converge on the recognition that leadership development is a complex, multidimensional process.

In light of these gaps, this study adopts a competency-based approach to examine leadership among municipal actors in Ecuador. Using Principal Component Analysis (PCA), we seek to identify latent competency dimensions and clusters that structure leadership profiles across different territorial contexts.

Strengthening local leadership competencies is not only a matter of administrative efficiency but also a prerequisite for achieving socially and institutionally sustainable governance. Prior studies have shown that leadership plays a crucial role in shaping institutions capable of implementing sustainable development agendas, particularly through participatory and inclusive decision-making [

10]. Scholars also emphasize that visionary and ethical leadership is essential for realizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as it enables multi-stakeholder collaboration and long-term commitment [

11]. This connection places leadership capacity at the core of international agendas such as the SDGs, particularly Goals 11, 16, and 17.

This study addresses the following research question: what are the underlying dimensions that characterize local leadership competencies in Ecuador, and how do they cluster among different territorial profiles? To respond, the general objective is to analyze the structure of leadership competencies among Ecuadorian local leaders through multivariate techniques, identifying dominant patterns and profiles. The working hypothesis proposes that these competencies are organized along two main axes: one associated with strategic–institutional capacity and the other with interpersonal–adaptive skills, both influenced by territorial and institutional contexts. Framing this dual-axis model within the broader agenda of sustainable governance highlights that strengthening leadership capacities is not only critical for organizational effectiveness but also essential for building resilient and inclusive institutions aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical background on leadership and decentralization.

Section 3 describes the research design and analytical procedures.

Section 4 presents the empirical results, followed by

Section 5, which discusses the findings in light of the theoretical framework. Finally,

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions and implications for policy and practice.

2. Theoretical Framework

In recent decades, leadership has increasingly been understood not as an innate attribute but as a set of competencies that can be learned, measured, and developed over time. Transformational leadership theory, as proposed by Bass and Avolio [

12], emphasizes the importance of strategic vision, charisma, and inspirational motivation in mobilizing people toward shared goals. These elements are particularly relevant in the public sector, where institutional legitimacy often depends on perceptions of leadership effectiveness.

Behavioral approaches, in turn, highlight what leaders do rather than who they are, focusing on observable practices such as communication, team facilitation, and conflict resolution [

13]. Yukl [

14] further argues that effective leadership behaviors must be contingent upon environmental demands, requiring adaptability and diagnostic capacity.

Table 2 presents a synthesis of how different leadership dimensions align with supporting theoretical frameworks.

In Latin America, the decentralization reforms of the late 20th century placed new demands on local governments and their leadership structures. The emphasis shifted from compliance-based administration to participatory governance, requiring leaders to manage scarce resources, engage with civil society, and foster inclusive development processes [

20,

21]. However, the uneven distribution of technical and human capacities across territories generates significant differences in the performance of local governments [

22,

23]. This is especially visible in rural or marginalized areas, where institutional density is limited and leadership often emerges from within the community with little access to formal training opportunities.

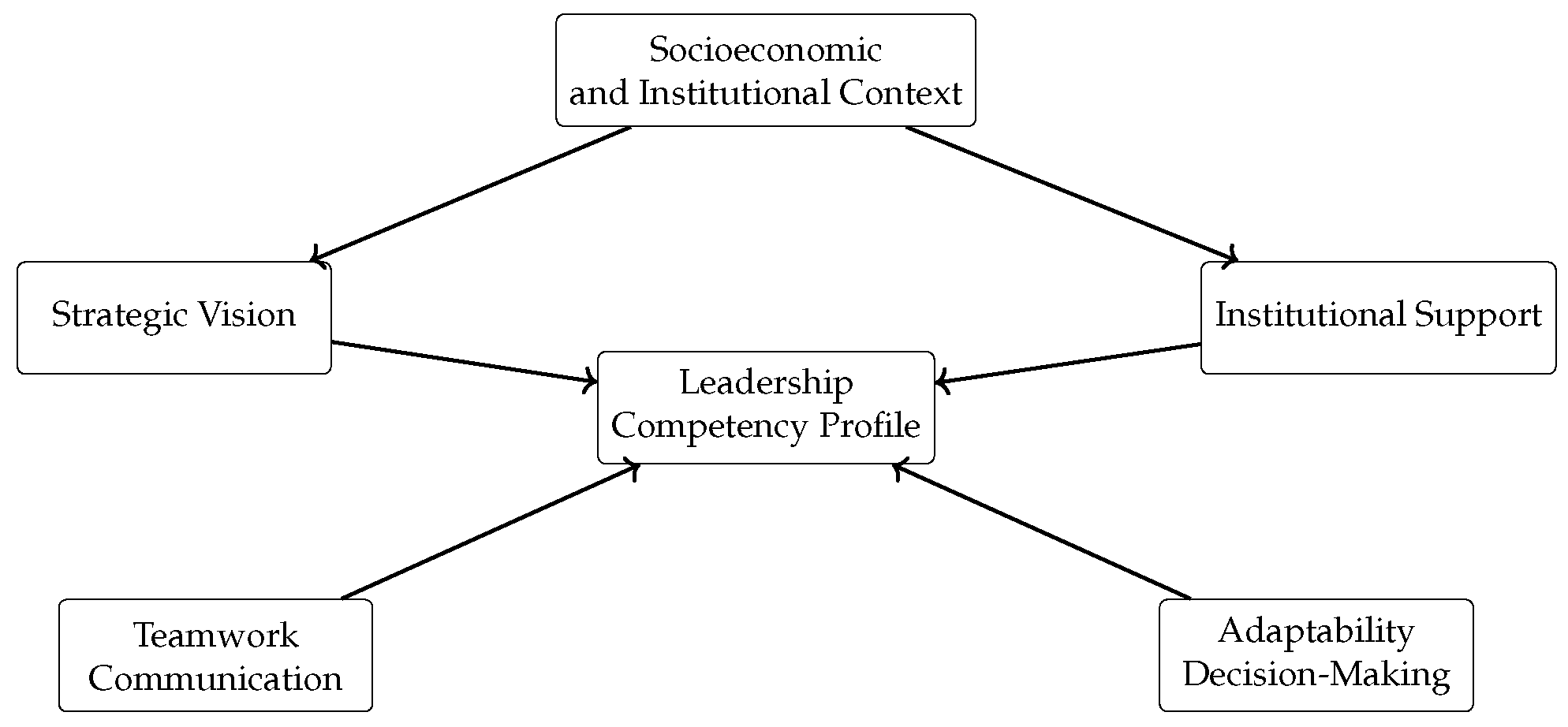

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of the interaction of leadership competency in local contexts. It highlights how external conditions, such as the socioeconomic and institutional context, interact with strategic vision and institutional support to shape a central leadership competency profile. Interpersonal skills such as teamwork and communication, together with adaptive capacities such as adaptability and decision-making, reinforce this profile, creating feedback loops between individual competencies and enabling conditions. To emphasize the sustainability perspective, the model also indicates that these competencies contribute to sustainable governance outcomes aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals.

In the context of sustainable governance, these dimensions go beyond organizational performance, as they shape institutions capable of ensuring equity, resilience, and inclusiveness. Effective governance is essential to achieve such transformations and to ensure inclusion, equity, and resilience [

18]. Contemporary research also underscores that by integrating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) principles, leaders can enhance resilience, promote sustainability initiatives, and positively impact communities [

19]. This theoretical foundation not only frames leadership as a set of measurable competencies but also situates these competencies within the broader agenda of sustainable governance. Linking local leadership to the SDGs provides a conceptual bridge between individual capacities and global development objectives.

3. Methodology

This study employed a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling strategy. A total of 60 individuals were selected based on their active participation in leadership roles within municipal governments, rural parishes, community organizations, or territorial development units. Participants were recruited from both urban and rural areas across multiple Ecuadorian provinces, ensuring diversity of institutional realities and resource access. Ethical approval was obtained from an academic review board, and informed consent was secured from all participants. Each dimension was operationalized through one or more indicators, using Likert-type or categorical response scales. Although the study employed a purposive non-probabilistic sampling strategy due to feasibility constraints, this design is aligned with the exploratory nature of our objectives. However, we acknowledge that the relatively small sample size may limit the statistical generalizability of the findings and potentially introduce selection bias. This limitation is explicitly recognized and further discussed in

Section 5.

3.1. Instrument and Variables

The survey instrument was designed around six leadership dimensions derived from the theoretical framework: strategic vision, communication, teamwork, decision-making, adaptability, and institutional support.

Table 3 summarizes the observed variables and their measurement criteria. These variables were chosen not only for their theoretical grounding in leadership studies but also for their practical relevance in assessing competencies that enable sustainable governance, in line with the SDGs framework.

Each theoretical dimension was operationalized with a single indicator to minimize respondent burden in municipal fieldwork and to align with the exploratory aim of this study. This 1:1 mapping preserves face and content validity while acknowledging a trade-off: single-item measures do not permit internal-consistency estimates. We therefore interpret our findings as indicative patterns that motivate more granular, multi-item instruments in subsequent confirmatory research.

We used a five-point Likert scale coded 0–4 for attitudinal items, with anchors from “not at all” (0) to “very high” (4). This design reduces respondent burden and harmonizes coding for subsequent standardization. Because all variables were standardized prior to PCA, the qualitative component structure is unaffected by rescaling.

All quantitative variables were standardized prior to analysis (mean = 0, variance = 1) to ensure comparability between scales. Furthermore, the inclusion of urban and rural leaders ensured variation in institutional density and resource access, which are critical to analyzing competencies related to socially and institutionally sustainable governance.

The instrument was developed with the support of two local-governance practitioners and three academics in public management. It was refined through a pilot test with 12 municipal staff to ensure clarity and contextual relevance. The final questionnaire is presented in anonymized form in

Appendix A.

3.2. Analytical Strategy

To reduce data complexity and uncover latent patterns, we applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA is widely used to identify dominant structures in datasets with correlated variables and enables the joint visualization of individuals and variable loadings through biplots [

24,

25]. Beyond statistical parsimony, PCA also facilitates the identification of leadership structures that can be operationalized as indicators of sustainable governance capacity.

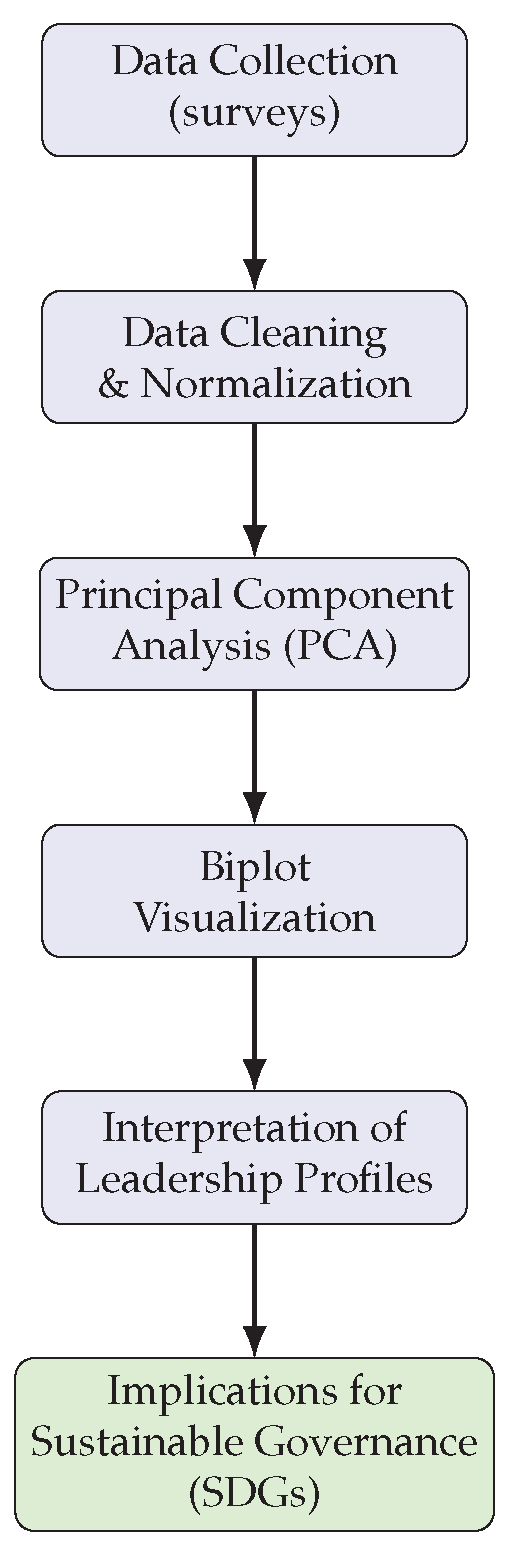

The methodological workflow is summarized in

Figure 2, implemented in TikZ. The process included data collection, cleaning, standardization, PCA computation, and the interpretation of leadership profiles.

3.3. Analytical Steps

The procedure was implemented in the following steps:

- 1.

Data Cleaning: Survey responses were reviewed for completeness. Missing values were addressed through pairwise deletion during PCA computation;

- 2.

Standardization: All variables were normalized to zero mean and unit variance to avoid scale bias;

- 3.

PCA Computation: PCA was conducted using the FactoMineR and psych packages in R (version 4.3.1);

- 4.

Component Retention: The Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues ) and a cumulative variance threshold of 80% were applied to retain principal components;

- 5.

Biplot Interpretation: A biplot was generated to visualize individuals and variable loadings simultaneously, facilitating the identification of clustered competency profiles.

PCA was estimated based on the correlation matrix using pairwise deletion, given the very low proportion of missing responses. As a robustness check, we re-estimated the analysis with listwise deletion and obtained highly similar results: the dominant first component explained 53.0% of the variance and the second component 15.0%, yielding a cumulative variance of 68.0%. This confirms that the two-dimensional structure reported in

Table 4 is stable regardless of the missing data treatment. The methodological design ensures both statistical rigor and conceptual clarity, while also generating evidence that can inform sustainable governance practices and contribute to monitoring progress toward the SDGs.

4. Results

This section reports the empirical results obtained from the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the competency data from 60 local leaders in Ecuador. Two dominant components explain over 90% of the total variance, enabling a compact yet informative representation of the latent structure of leadership competencies and providing insights into their implications for sustainable governance.

4.1. Principal Components and Explained Variance

Table 4 presents the eigenvalues and the percentage of explained variance for the six principal components. The first component (PC1) has an eigenvalue of 3.226, capturing 53.77% of the total variance. The second component (PC2) explains an additional 6.72%, bringing the cumulative variance of the first two dimensions to 60.49%. This indicates that a substantial share of the variability in the observed leadership competencies can be summarized along a single dominant latent dimension, which is strongly associated with strategic vision, institutional support, and decision-making, while a complementary second axis reflects additional variation linked to interpersonal and adaptive skills.

The second component (PC2) explains an additional 10.07% of the variance, bringing the cumulative proportion of explained variance for the first two dimensions to

90.73%. This satisfies the conventional threshold of retaining components that together explain at least 70 to 80% of the total variance [

25], suggesting that the PCA solution is both statistically robust and interpretable.

In contrast, the third and fourth components (PC3 and PC4) account for only marginal amounts of variance (5.43% and 3.84%, respectively), with eigenvalues well below 1. According to the Kaiser criterion, these components should not be retained for interpretation, as they represent noise rather than meaningful structure.

Taken together, the results justify the focus on the two-dimensional solution, which is sufficient to uncover the underlying structure of local leadership competencies in Ecuador. This parsimonious representation balances explanatory power with interpretability and reflects two complementary dimensions that are critical for sustainable governance: institutional resilience and community adaptability.

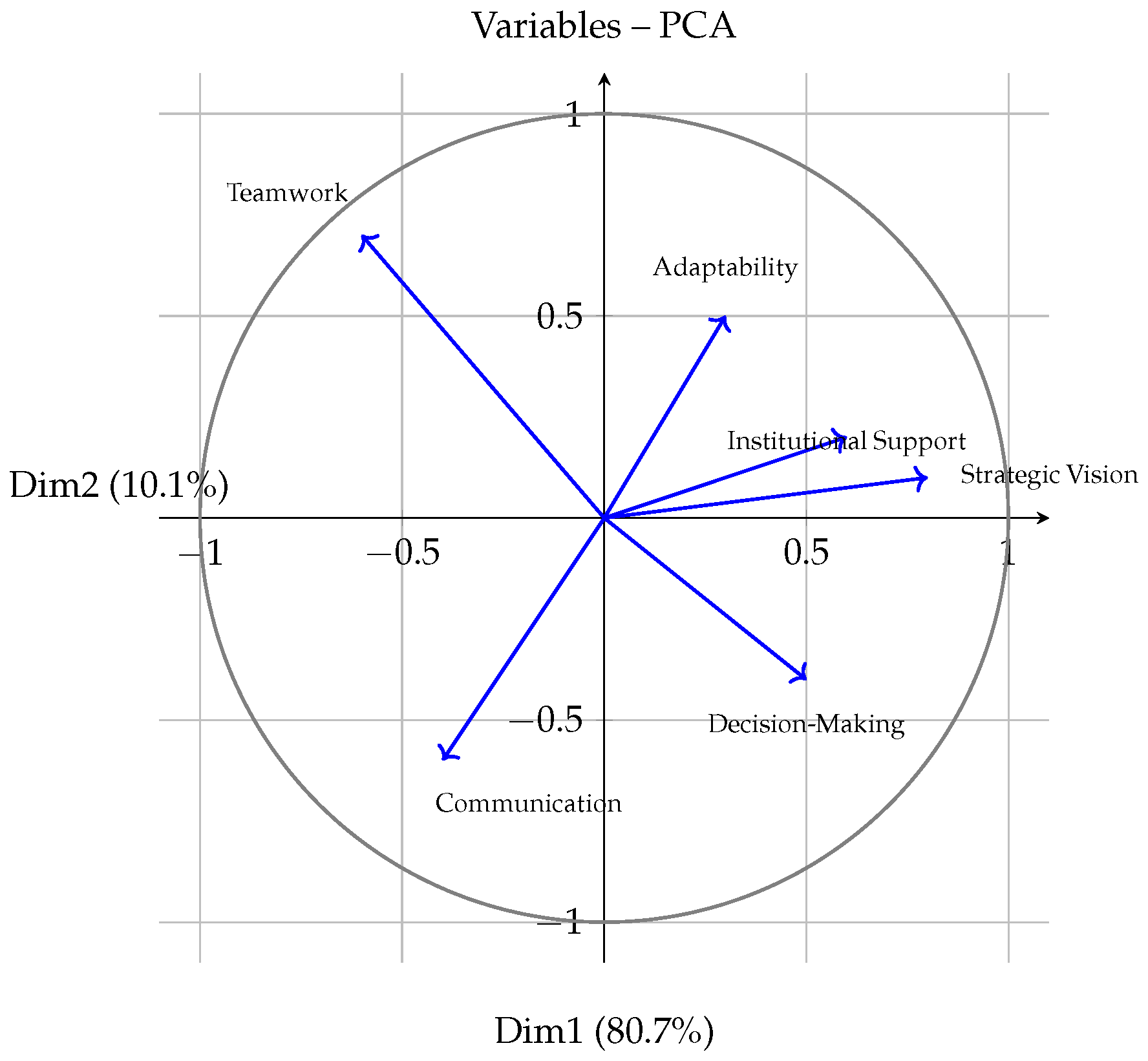

4.2. Contribution of Variables to PCA Dimensions

Figure 3 presents the correlation circle, which projects the six competency variables onto the first two principal components. In this visualization, variables are represented as vectors radiating from the origin, and their proximity to the unit circle reflects the strength of their correlation with the components. Vectors closer to the circle indicate a stronger contribution, while shorter vectors suggest weaker influence [

24,

25].

The results reveal two distinct patterns. First, Strategic Vision and Institutional Support are highly aligned with PC1, highlighting the dominant role of strategic and institutional factors in explaining the variance of leadership competencies. Decision-Making also contributes positively to PC1, though with a more moderate loading. Together, these variables define a strategic and institutional dimension, consistent with the theoretical expectation that effective local leadership requires long-term planning and institutional capacity, in line with the SDG objective of building strong institutions (Goal 16).

Second, Teamwork, Communication, and Adaptability show stronger alignment with PC2, forming an interpersonal and adaptive dimension. This suggests that leaders operating in resource-constrained or uncertain environments rely more on relational and adaptive competencies to maintain legitimacy and foster collective action, which resonates with the SDG focus on resilient and inclusive communities (Goal 11). The near orthogonality between the two sets of variables supports the interpretation of a dual-axis model, where institutional and interpersonal competencies complement each other rather than overlap. This correlation structure justifies the two-dimensional solution retained from the PCA and provides empirical support for theories of adaptive and distributed leadership in decentralized governance contexts.

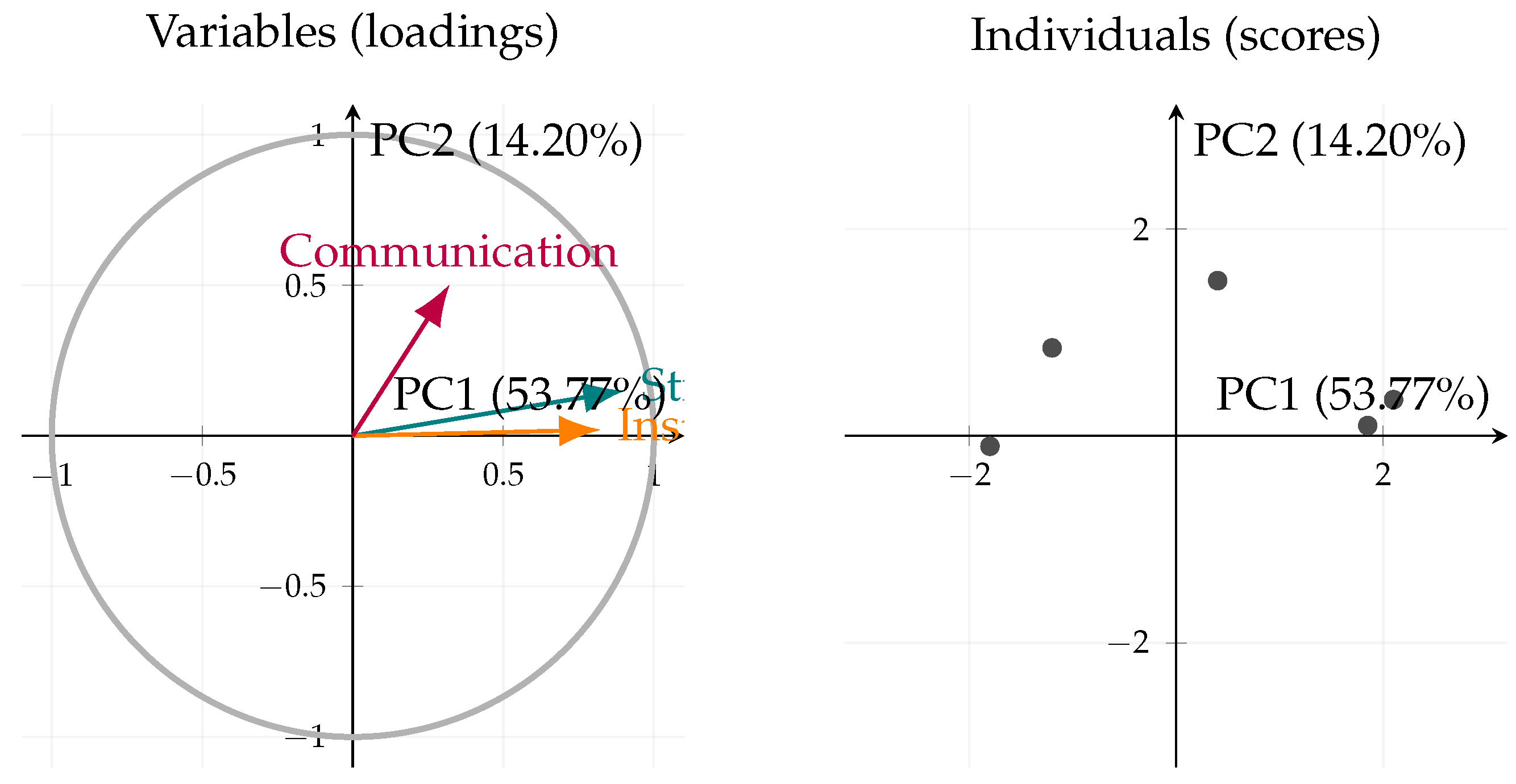

4.3. Biplot of Individuals and Variables

Figure 4 presents a two-panel biplot. The left panel shows the six competency variables as colored vectors within the unit circle, illustrating their relative contributions to the principal components. The right panel displays the individual leaders as points projected onto the PC1–PC2 plane, allowing the identification of clustering patterns in leadership profiles. This separation between variables and individuals improves interpretability by avoiding scale distortions, while still capturing the joint structure of the data [

24,

25].

The interpretation follows two principles. First, the orientation and length of the vectors indicate the contribution of each variable to the components: longer arrows close to the unit circle represent stronger correlations, while shorter ones suggest weaker explanatory power. As seen in the figure, Strategic Vision and Institutional Support vectors extend strongly along PC1, underscoring the dominance of institutional factors. In contrast, Teamwork, Communication, and Adaptability vectors are oriented toward PC2, highlighting the interpersonal and adaptive axis.

Second, the position of the individual dots reflects the competency profiles of local leaders. Dots located in the upper-right quadrant, near the Strategic Vision and Institutional Support vectors, represent leaders whose competencies are predominantly institutional, often linked to urban or well-resourced contexts. In contrast, dots positioned toward the upper part of the PC2 axis, closer to Teamwork and Communication, correspond to leaders whose strengths lie in interpersonal coordination and adaptive practices, profiles more typical of rural or community-embedded contexts. Leaders distributed in intermediate positions can be interpreted as mixed profiles, combining institutional capacity with interpersonal engagement.

In general, the biplot validates the existence of two complementary competency profiles: institutional leaders, geared toward strategic vision and supported by formal structures, and community-based leaders, oriented toward adaptability and interpersonal coordination. This empirical typology illustrates how contextual differences translate into different leadership trajectories, consistent with adaptive and distributed leadership theories, and highlights their respective contributions to achieving sustainable governance.

The visualization of profiles also reinforces the urban–rural divide observed in the descriptive statistics. Leaders clustered along the institutional axis (PC1) are predominantly from urban municipalities, where access to technical staff and training programs is more frequent. In contrast, leaders located near the interpersonal–adaptive axis (PC2) correspond largely to rural territories, where relational legitimacy compensates for limited institutional density. This urban–rural differentiation highlights systemic inequalities in governance capacity and reflects the broader challenge of ensuring equitable access to resources for sustainable leadership development.

4.4. Summary of Key Findings

The PCA results yield the following insights that structure leadership profiles across territorial contexts:

PC1 (80.66%) captures a strategic and institutional dimension, strongly associated with Strategic Vision, Institutional Support, and Decision-Making, which aligns with SDG 16 on strong institutions;

PC2 (10.07%) captures an interpersonal and adaptive dimension, with higher loadings for Teamwork, Communication, and Adaptability, reflecting conditions of resilience consistent with SDG 11 on sustainable communities;

The biplot reveals distinct clusters: (i) institutional leaders (often urban, with access to training and resources) and (ii) community-based leaders (often rural, emphasizing interpersonal coordination and adaptability);

The two-component solution (PC1 and PC2) explains 90.73% of total variance, supporting a compact representation suitable for policy and training design;

The dual-axis model provides an empirical foundation to link leadership competencies with sustainable governance outcomes, bridging institutional resilience and community adaptability as complementary dimensions of the SDGs.

5. Discussion

The results of the PCA confirm the existence of a dual-axis competency structure among local leaders in Ecuador. In this section, we interpret the key findings in relation to the theoretical framework and prior empirical evidence, highlighting their implications for leadership development, public policy, and sustainable governance.

5.1. Dominance of Strategic and Institutional Dimensions

The first principal component (PC1), which explains more than 80% of the variance, was largely shaped by strategic vision, institutional support, and decision-making capacity. This reinforces the idea that effective local leadership in the decentralized governance contexts is closely tied to competencies that enable leaders to set clear development goals, align institutional resources, and manage complex administrative environments [

12,

14,

15]. The strong association between institutional capacity and strategic leadership resonates with previous findings on Latin American municipalities, where the density of technical staff and the availability of financial resources are directly linked to higher leadership performance [

22,

23].

5.2. Interpersonal Competencies as a Complementary Axis

The second principal component (PC2), although explaining only about 10% of the variance, aggregates interpersonal competencies such as communication, teamwork, and adaptability. These skills become particularly relevant in environments where institutional capacity is weaker and leaders must rely on relational and adaptive strategies to maintain legitimacy and achieve community goals [

13,

17]. Recent advances in leadership research underscore the importance of adaptability and interpersonal competencies in uncertain governance contexts [

26].

5.3. Correlation Patterns and Leadership Profiles

The correlation patterns revealed by the PCA biplot suggest two dominant leadership profiles: (i) institutional leaders, associated with strong alignment to strategic vision and institutional support, typically located in urban or better-resourced municipalities; and (ii) community-based leaders, whose competencies emphasize teamwork, communication and adaptability, often observed in rural or socially cohesive contexts.

Table 5 summarizes these profiles, detailing the core competencies that characterize each group and the contexts where they are most frequently found.

These findings illustrate how disparities in institutional support not only affect the availability of technical resources but also shape the very structure of leadership competencies. Urban leaders, benefiting from stronger institutional scaffolding, develop profiles aligned with strategic vision and formal decision-making, whereas rural leaders rely more heavily on adaptability, teamwork, and community legitimacy. This structural divide suggests that strengthening rural leadership requires policy interventions that go beyond individual training, addressing systemic inequalities in institutional infrastructure.

5.4. Alignment with Theoretical Models

The two-dimensional competency model identified in this study aligns with complexity and adaptive leadership theories, which argue that leaders must combine administrative and relational skills to navigate uncertain environments [

13,

27]. The findings also resonate with distributed leadership perspectives, which emphasize collaboration and participatory governance as key to sustaining effectiveness in decentralized systems [

16].

5.5. Practical Implications and Policy Recommendations

The identification of two complementary leadership profiles has direct implications for practice and policy. For training institutions, the results suggest that curricula should integrate both strategic–institutional competencies (e.g., strategic vision, decision-making, institutional support) and interpersonal–adaptive skills (e.g., teamwork, communication, adaptability). Training programs designed exclusively around administrative and technical competencies risk neglecting the relational dimensions that are crucial in rural and community contexts.

From a policy perspective, our findings emphasize the need to reduce territorial disparities in access to training and resources. Policymakers should prioritize targeted programs for rural and community-based leaders, ensuring equitable access to professional development opportunities. Furthermore, leadership development initiatives could be aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by explicitly linking training content to institutional resilience (SDG 16), community resilience (SDG 11), and multi-stakeholder partnerships (SDG 17).

Finally, development agencies and government institutions should consider designing hybrid programs that combine formal training with community-based learning experiences. Such initiatives can simultaneously strengthen institutional capacities and preserve the relational legitimacy that characterizes community-based leaders, thus fostering more sustainable and inclusive governance outcomes.

5.6. Practical Implications and Future Research

The dual-axis model of leadership competencies has several implications. Training programs for local leaders should integrate both strategic and interpersonal dimensions, ensuring that technical instruction is complemented with modules on communication, teamwork, and adaptability. Public policies aimed at strengthening local governance should address territorial disparities in access to training and resources, with particular emphasis on supporting rural leaders. Future research should expand this analysis using longitudinal designs to explore how leadership competencies evolve over time, particularly in response to decentralization reforms or external shocks. Comparative studies across Latin American countries may also shed light on common patterns and divergences, offering a broader regional perspective.

An important limitation of this study concerns the restricted external validity of the findings. The purposive sample of 60 leaders, while diverse in territorial distribution, cannot be considered representative of all local leaders in Ecuador. Moreover, the cross-sectional design prevents causal inference and restricts the analysis to a single moment in time. The focus on Ecuador, although justified by the importance of territorial decentralization in this context, further narrows the applicability of the results. We therefore recommend interpreting these findings as indicative patterns rather than definitive evidence.

5.7. Implications for Sustainable Governance

Beyond their organizational relevance, the two dimensions identified in this study have direct implications for sustainable governance. Strategic and institutional competencies support the development of resilient institutions that can design and implement inclusive policies, contributing to SDG 16. Interpersonal and adaptive competencies reinforce community resilience and collective action, consistent with SDG 11. Together, they promote multi-stakeholder collaboration and partnerships that are at the heart of SDG 17. Beyond their organizational relevance, the two dimensions identified in this study have direct implications for sustainable governance. Strategic and institutional competencies support the development of resilient institutions that can design and implement inclusive policies, contributing to SDG 16. Interpersonal and adaptive competencies reinforce community resilience and collective action, consistent with SDG 11. Together, they promote multi-stakeholder collaboration and partnerships that are at the heart of SDG 17.

Table 6 further details the alignment between the leadership competencies identified in this research and specific SDG targets, highlighting their contribution to sustainable governance.

By empirically linking leadership competencies with sustainable governance outcomes, this study provides evidence that local leadership development is not only a matter of administrative efficiency but also an essential condition to achieve socially inclusive and institutionally resilient communities aligned with the SDGs. By explicitly linking these leadership profiles with the Sustainable Development Goals, the study shows that reducing institutional support disparities is essential not only to achieve SDG 16 (effective institutions) but also to promote SDG 11 (sustainable communities) and promote SDG 17 (partnerships for goals).

6. Conclusions

This study analyzed the competency structure of local leadership in Ecuador using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) applied to survey data from 60 leaders across urban and rural contexts. The findings highlight a two-dimensional model of leadership competencies that integrates strategic and institutional capacities together with interpersonal and adaptive skills.

The first principal component (PC1), which explains more than 80% of the variance, reflects a strategic and institutional axis that emphasizes strategic vision, institutional support, and decision-making capacity;

The second principal component (PC2), accounting for an additional 10% of the variance, represents an interpersonal and adaptive axis associated with teamwork, communication and adaptability;

The biplot revealed distinct leadership profiles: institutional leaders, often based in urban areas with better access to training and resources, and community leaders, more common in rural territories where legitimacy is grounded in interpersonal competencies.

Together, these results provide robust empirical evidence for a dual-axis model of local leadership competencies, consistent with contemporary leadership theories that emphasize the need to balance strategic capacity with relational engagement in decentralized governance contexts.

From a practical perspective, the study suggests that leadership training programs should integrate both technical and relational modules, ensuring that leaders are equipped to design strategic plans, mobilize institutional resources, foster collaboration, and build trust. Policymakers should prioritize equitable access to training opportunities and resources, particularly in rural and marginalized territories, where institutional capacity remains limited.

Most importantly, this study demonstrates that strengthening local leadership competencies is not only relevant for organizational performance but also a prerequisite to advance socially inclusive and institutionally resilient governance. By explicitly linking competencies with the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goals 11, 16, and 17, the findings underscore the crucial role of local leadership in building sustainable, equitable, and resilient communities. Future research could extend this analysis through longitudinal designs and comparative studies in Latin America to provide more insight into how leadership competencies evolve and contribute to sustainable governance.

Future research should expand the scope of analysis by including larger and more representative samples, ideally using probabilistic strategies and comparative multi-country designs across Latin America. Such studies would improve external validity, enable cross-national comparisons, and provide deeper insights into how leadership competencies vary across different institutional and cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.-N. and C.V.-S.; methodology, C.V.-S. and N.M.; software, C.V.-S.; validation, L.C.-N., J.C.-C. and E.Y.-R.; formal analysis, C.V.-S. and N.M.; investigation, L.C.-N., J.C.-C., E.Y.-R. and L.O.-P.; resources, L.C.-N. and J.C.-C.; data curation, E.Y.-R. and L.O.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V.-S. and N.M.; writing—review and editing, L.C.-N., J.C.-C., E.Y.-R., L.O.-P., N.M. and C.V.-S.; visualization, N.M. and C.V.-S.; supervision, L.C.-N. and C.V.-S.; project administration, L.C.-N.; funding acquisition, L.C.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and confidentiality was guaranteed under the institutional ethical framework of UNEMI.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request. Due to confidentiality agreements with participating institutions and respondents, individual-level survey responses cannot be publicly shared. The aggregated data and analytical code used for the PCA and biplot visualizations are available upon request to promote transparency and reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the local leaders and institutions in Ecuador who generously participated in this study and shared their time and insights. Special appreciation is extended to the Universidad Estatal de Milagro and collaborating universities for their support in data collection and logistical coordination. The authors also thank colleagues who provided feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript, which helped to refine the analysis and strengthen the discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Instrument (Anonymized)

Strategic Vision (0–4): “Clarity of long-term territorial goals”;

Communication (0–4): “Confidence in public speaking with stakeholders”;

Teamwork (0–4): “Collaborative decision-making within the team”;

Decision-Making (0/1): “Have you led a formal conflict resolution in the last year?”;

Adaptability (0–4): “Ability to respond to institutional change”;

Institutional Support (0–2): “Access to training programs (0 = none, 1 = occasional, 2 = regular)”.

References

- Rowe, W.E.; Chamorro, P.; Hayes, G.; Corak, L. Collective Leadership and Its Contribution to Community Resiliency in Salinas, Ecuador. In Handbook of Global Leadership and Followership; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinson, R. Impacts of Remote Learning Measures: Educational Equity Challenges in Ecuador. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2022, 24, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friley, B.L. Influencing health through communication theory: Development of a persuasive campaign for a nonprofit community health center. Commun. Teach. 2024, 38, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercader, V.; Galván-Vela, E.; Ravina-Ripoll, R.; Popescu, C.R.G. A Focus on Ethical Value under the Vision of Leadership, Teamwork, Effective Communication and Productivity. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, T.P.; Afroze, R.; Sarker, M.A.R. The Impact of Leadership, Communication, and Teamwork Practices on Employee Trust in the Workplace. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 12, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottafava, D.; Cavaglià, G.; Corazza, L. Education of sustainable development goals through students’ active engagement: A transformative learning experience. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyarov, D.V. Development of bilingual education in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China at the present stage. Vostok (Oriens) 2023, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellan-Santana, L.A.; Salvatierrra-Carranza, M.A.; Vera-Santana, A.d.R.; Garcia-Vera, F.M. Pedagogical transformational leadership for Ecuadorian education. Epistem. Koin. 2022, 5, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.C.C.; Gondhalekar, A.R.; Choa, G.; Rashid, M.A. Adoption of problem-based learning in medical schools in non-Western countries: A systematic review. Teach. Learn. Med. 2024, 36, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, F. The Essence of Leadership for Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals; SDG Knowledge Hub, International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2018; Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/generation-2030/the-essence-of-leadership-for-achieving-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Bass, B.M.; Avolio, B.J. Transformational Leadership: Industrial, Military, and Educational Impact, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse, P.G. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 9th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yukl, G.A. Effective Leadership Behavior: What We Know and What Questions Need More Attention. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Enhancing Innovation Capacity in City Government; OECD Publication: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bolden, R. Distributed Leadership in Organizations: A Review of Theory and Research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukl, G.; Mahsud, R. Why Flexible and Adaptive Leadership Is Essential. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2010, 62, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. UNDP Strategic Plan 2022–2025; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rosário, A.T. How Sustainable Leadership Can Leverage Resilience and ESG to Drive Community Impact. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.Y.M.; Delgado, N.G.; Romano, J.O. Territorial Approach and Rural Development Challenges: Governance, State and Territorial Markets. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Vizuete, G.; Robalino-López, A. A Systematic Roadmap for Energy Transition: Bridging Governance and Community Engagement in Ecuador. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A.; Niftiyev, I. E-government and Petty Corruption in Public Sector Service Delivery. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2024, 36, 3987–4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeri, I.; Gutman, M.A.; Luzer, J. Municipal Territoriality: The Impact of Centralized Mechanisms and Political and Structural Factors on Reducing Spatial Inequality. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Williams, L.J. Principal component analysis. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2010, 2, 433–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. Principal Component Analysis, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nöthel, S.; Nübold, A.; Uitdewilligen, S.; Schepers, J.; Hülsheger, U. Development and validation of the adaptive leadership behavior scale (ALBS). Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1149371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esenyel, V. Evolving Leadership Theories: Integrating Contemporary Theories for VUCA Realities. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).