Abstract

Plastic is a key industrial innovation with wide ranging applications. However, its extensive production, consumption, and inadequate disposal practices have created a complex environmental challenge, resulting in escalating ecological and public health impacts. This study examines plastic waste management practices in the rural coastal communities of Kendwa, Nungwi, Paje, and Michamvi, located near tourist hotels in Zanzibar’s Northern and Southern districts, Tanzania. Structured interviews, observation checklists, and participatory workshops were used to assess the types of plastic waste generated and the level of community engagement in disposal practices. Findings indicate that single-use polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) packaging, particularly beverage bottles and other disposable items from hotels, dominate the waste stream. Nungwi and Kendwa demonstrate proactive responses, supported by a professional waste management company and NGO-led awareness programs promoting sustainable practices. In contrast, Paje and Michamvi continue to face challenges from tourism-linked waste, highlighting disparities in local management capacity. Despite positive initiatives in Nungwi and Kendwa, persistent littering remains a problem due to weak enforcement, limited infrastructure, and inconsistent community compliance. To address these gaps, the study recommends implementing waste bank programs alongside financial sustainability measures and community empowerment initiatives, to reinforce existing efforts and advance more sustainable waste management.

1. Introduction

Tourism is a major global industry that generates substantial economic benefits, including increased production, income, and employment [1,2,3]. However, it also exerts considerable environmental pressure, particularly through the hotel sector, which accounts for approximately 21% of the ecological footprint of the tourism and hospitality industry due to high energy consumption, water use, and waste generation [4,5,6]. These challenges are more pronounced in the Global South, where recycling systems, extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes, and reuse initiatives often fail due to limited policy resources and institutional capacity. Consequently, effective solid waste management has become essential both to safeguard natural resources and to advance sustainable practices [6,7,8,9].

In Zanzibar, tourism is not only a cornerstone of the economy but also a vital source of livelihoods, contributing nearly 28% of GDP and 82% of foreign exchange earnings [10]. With an annual growth rate of 15%, the sector is generating rising volumes of waste that place immense strain on local management systems and threaten the ecosystems upon which the industry depends [10,11,12,13]. Whereas organic waste once dominated, plastics and hazardous materials now constitute a growing proportion of the waste stream. The convenience-driven nature of tourism and hospitality has accelerated this trend, with widespread use of single-use plastics such as bottles, food wrappers, and bags. The resulting accumulation of plastic waste threatens the island’s natural beauty, pollutes coastal ecosystems, and endangers marine life through ingestion, entanglement, habitat disruption, and micro plastic contamination [6]. Public health risks also arise, as discarded containers provide breeding sites for disease vectors [6,11].

Addressing these risks requires systemic reform of waste management practices in Zanzibar. Such reform must involve a redefinition of both the tourism and waste management value chains while integrating evidence-based and innovative approaches [6,14]. Eco-innovative strategies that combine environmental protection with multi-stakeholder participation are particularly vital for developing policies capable of mitigating environmental degradation [15,16,17]. In contexts where formal systems are weak, community engagement plays a central role in achieving waste management objectives. Active involvement in clean-up campaigns, waste sorting, and small-scale recycling enhances efficiency, builds local ownership, and fosters behavioral change toward sustainable practices [18,19]. Evidence shows that women and youth are often at the forefront of these initiatives, bridging gaps between communities and authorities and ensuring more inclusive outcomes [18,19].

A growing body of research highlights the significance of women’s participation in waste prevention, emphasizing the importance of socially inclusive strategies for equitable resource management [20]. Initiatives that prioritize waste reduction, reuse, and recycling are key pillars of a circular economy, and women are often central to these efforts. The European Union’s Horizon 2020 Urban Waste project [15] demonstrates how circular economy principles can effectively reduce waste and improve resource efficiency in tourism contexts. Similarly, refs. [18,19] underline the role of youth entrepreneurship and innovation in advancing circular practices, arguing that entrepreneurial approaches not only promote economic growth but also catalyze sustainable waste management [14,18]. Supported by robust policy frameworks, such strategies can significantly reduce the ecological footprint of tourism while enhancing resource efficiency [15,21].

Despite these promising directions, waste generation in tourism remains disproportionately high. In 2018, tourism-related waste in Zanzibar was estimated at 1.5–2 kg per tourist per day, three to four times greater than local waste generation rates [16]. Much of this waste consists of single-use plastics and toiletries. However, systematic waste segregation strategies are largely absent, and data on plastic generation and disposal remain limited [16], constraining the design of effective interventions and policies. As a result, plastic litter is widespread across beaches, coastal waters, and other natural areas, with severe ecological and economic consequences [14,16,18]. Contributing factors include limited technical expertise, inadequate recycling infrastructure, low levels of public awareness, and weak enforcement of regulations [14,16].

At the same time, Zanzibar has witnessed the emergence of community-based and entrepreneurial initiatives that provide important pathways toward sustainable plastic waste management. Organizations such as the Zanzibar Scraps and Environment Association (ZASEA) promote collection and recycling, while social enterprises like CHAKO, in partnership with the TUI Care Foundation, pioneer upcycling models that empower women and youth by converting waste into marketable products. Other initiatives, including recycling at OZTI, the HDPE recycling program, and the youth-led efforts of ZAYEDESA and KAWA, combine environmental stewardship with education and capacity-building. Informal reuse practices, such as repurposing PET bottles, further reflect a culture of resourcefulness that could be scaled for broader impact (unpublished NGO data, Zanzibar, 2023). Together, these initiatives underscore the potential of community-centered strategies to transform waste challenges into opportunities for social, economic, and environmental benefits.

Nevertheless, comprehensive studies that examine the intersection of tourism, waste generation, and community-driven sustainability strategies in Zanzibar and other small island contexts remain limited [16,17]. Prior research has demonstrated the effectiveness of strategies focused on reducing, reusing, and recycling plastics in addressing the global plastic crisis [18]. However, gaps persist in understanding how these approaches can be adapted to tourism-dependent islands with weak formal infrastructures. Research also points to the importance of cultural, economic, and policy factors in shaping consumer behavior and influencing the success of circular economy initiatives [22,23]. Collaboration among policymakers, businesses, and consumers is therefore critical for advancing sustainable practices [23].

In this context, Zanzibar represents a compelling case for exploring community-driven, tourism-focused approaches to plastic waste management. Existing systems remain predominantly linear, characterized by the generation, collection, and disposal of waste with little emphasis on reduction or resource recovery. This model is increasingly unsustainable, particularly as waste volumes rise. Integrating circular economy principles offers a pathway toward sustainability, supported by emerging technologies such as biodegradable plastics, advanced recycling, and waste-to-energy solutions [24,25]. However, the effectiveness of such interventions depends on empowering local communities to actively shape waste governance while simultaneously addressing the political and economic constraints that hinder the scaling of grassroots initiatives. Evidence from Guatemala [17] illustrates how expanding localized actions can strengthen plastic governance, yet also highlights the structural barriers that must be negotiated for such efforts to achieve broader systemic impact.

Recent policy initiatives reflect this growing momentum. The Zanzibar Commission for Tourism (ZCT) launched the Zanzibar Declaration for Sustainable Tourism in 2023, calling on the tourism industry to adopt practices that benefit people, the planet, and the economy. The declaration emphasizes waste reduction and resource efficiency, aligning the island’s efforts with global sustainability frameworks. By strengthening waste management and ecosystem restoration, Zanzibar is positioning itself as a regional leader in responsible tourism.

Building on earlier work, this study examines innovative and context-specific approaches to plastic waste management in Zanzibar’s rapidly expanding tourism sector, with the dual aim of addressing local challenges and aligning practices with global sustainability frameworks. Previous research on coastal environments has largely concentrated on household and industrial sources of plastic leakage [26], while more recent studies highlight tourism as an increasingly important driver of marine plastic pollution [27]. At the policy level, international sustainability agendas provide important points of reference: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [28], the Global Tourism Plastics Initiative [29], and the One Planet Network [30] all emphasize waste reduction, circular economy strategies, and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Global analyses further confirm that local waste management interventions can significantly reduce plastic leakage into coastal ecosystems. Despite these insights, interventions specifically tailored to tourism remain scarce, with research calling for systemic, behavioral, and circular approaches to address this gap [31,32,33,34].

The Zanzibar case study builds on this literature by foregrounding tourism-specific, community-driven strategies. Unlike studies that focus primarily on quantifying waste flows or household recycling [35,36,37,38], which highlight seasonal and infrastructural pressures on small islands [39,40], prior work has not engaged with grassroots innovation. By contrast, the Zanzibar case illustrates how resort-based collection cooperatives and local upcycling enterprises can embed circular economy practices within local cultural contexts, while simultaneously aligning with international frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the Global Tourism Plastics Initiative. In addition, the recent literature on the politics of plastic governance in the Global South underscores the need for justice-oriented and context-sensitive approaches [41], reinforcing the value of locally embedded and socially responsive models such as those emerging in Zanzibar. Through this holistic perspective, the study generates actionable recommendations for stakeholders ranging from local authorities to community organizations. The findings contribute to strengthening ongoing initiatives, such as the Zanzibar Declaration on Sustainable Tourism, and to advancing global debates on sustainable waste governance in tourism-dependent economies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopted a qualitative design to examine community-based plastic waste management practices in Zanzibar. A mixed strategy combining case studies and descriptive surveys was applied to capture both the details of community-level practices and the scope of sector-wide dynamics. Case studies of selected communities provided insights into local practices and challenges, while descriptive surveys generated broader contextual data on waste management patterns. This triangulated approach enhanced the robustness of findings, ensuring greater validity while maintaining a qualitative orientation. Secondary data from government and institutional reports were also incorporated to situate primary findings within wider policy and sectoral dynamics.

2.2. Description of the Study Area

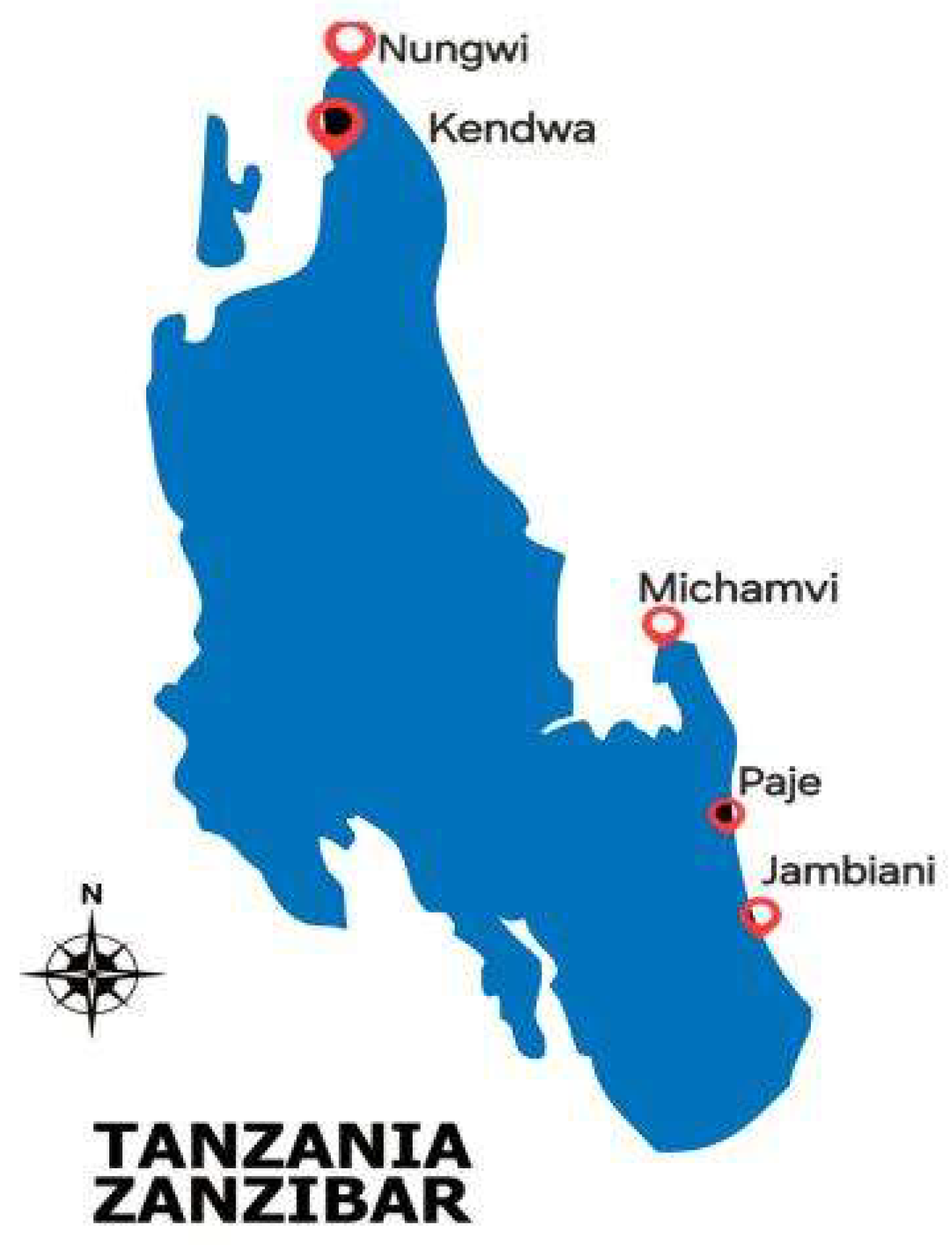

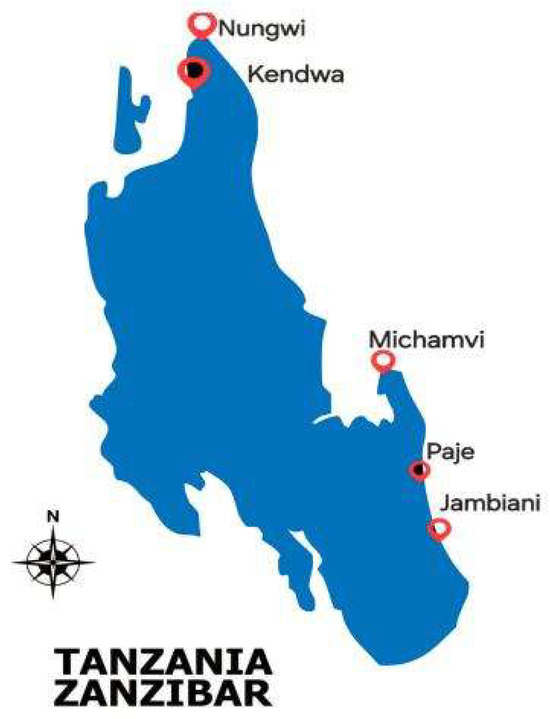

This research was conducted in four coastal sites of Unguja Island: Nungwi, Kendwa, Paje, and Michamvi (Figure 1), chosen for their concentration of hotels, close interface with local communities (0.2–0.5 km), and evident beach littering, particularly plastics. These locations represent Zanzibar’s primary tourism corridors, where rapid growth in hospitality infrastructure has intensified plastic waste generation. Collectively, they host around 140 hotels, ranging from one-to five-star establishments, comprising 4375 rooms and 8197 beds (unpublished, report report, ZCT, 2024). Notably, 38% of higher-grade hotels are situated in these areas (unpublished report, ZCT, 2024), many under international ownership, with correspondingly higher tourist volumes and plastic waste output due to higher tourist occupancy and service standards. The intersection of dense tourism activity, community proximity, and visible plastic pollution makes these locations representative settings for examining hospitality-driven plastic waste management in Zanzibar.

Figure 1.

A map of the Study Area.

2.3. Data Collection Methods

A qualitative methodology was employed, combining structured interviews, direct observations, and participatory workshops. This design enabled the study to capture both the practical dimensions of plastic waste management and the lived experiences and perceptions of community members.

2.3.1. Direct Observations

Observations were made to document actual waste management behaviors, practices, and environmental conditions in the study areas. This method was essential for discovering patterns or practices not easily expressed through interviews, such as informal waste handling methods and real-world challenges in waste disposal. The observation data complemented the interview findings and helped to ground the research in actual behaviors.

2.3.2. Structured Interviews

Structured interviews were conducted between October 2023 and March 2024 with a total of 80 participants selected for their involvement in plastic waste management. Participants included 60 community members (15 from each of the four study sites: Kendwa, Nungwi, Paje, and Michamvi), 10 hotel managers, 4 community leaders, 2 waste contractors, 2 recyclers, and 2 representatives from district councils operating in the study area. A predefined interview guide with structured questions was used to ensure consistency while allowing flexibility to accommodate feedback and emerging themes. The guide focused on seven key areas, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Themes and sample questions from the structured interview guide with community members.

2.3.3. Participatory Workshops

Two participatory workshops were conducted in the study area: one in the northern district (Kendwa/Nungwi) and one in the southern district (Paje/Michamvi), each engaging 25 participants, for a total of 50 participants. Participants were selected with support from local leaders to ensure representation across different demographic groups. The workshops brought together local government representatives, community members, hotel representatives, waste collection companies, and two recycling enterprises operating in the study area, providing a multi-stakeholder perspective on plastic waste management.

Each session included brief presentations on plastic waste sources, impacts, and eco-conscious practices, followed by guided discussions and interactive activities to foster dialogue and co-create community-driven solutions. Facilitators ensured that all participants, including women, youth, elders, and local leaders, had a voice. Activities were documented through field notes and audio recordings, and insights were used to inform eco-innovative, locally tailored waste management strategies (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sample guiding questions and purposes from stakeholder participatory workshops.

2.4. Sampling Strategy

A combination of sampling strategies was employed to select participants for both structured interviews and participatory workshops. For the structured interviews, a simple random sampling approach was used to select households within a 500-m to 1-km radius of selected hotels in each of the four study sites. This spatial criterion was chosen to capture households likely exposed to tourism-related plastic waste.

To enhance relevance and reliability, local leaders (Shehas) assisted in identifying household members actively involved in or knowledgeable about local waste management systems. This purposive element complemented the random selection by ensuring participants could provide informed perspectives on community-level practices, challenges, and opportunities.

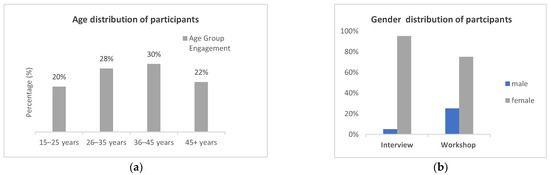

The sample was notably gendered: 95% of interview participants and 75% of workshop attendees were women. This distribution reflects the high level of female engagement in grassroots waste management efforts in Zanzibar. The smaller male sample is therefore representative of the target population and provides meaningful insights within the study context. Similar gendered patterns have been documented across the Global South, where women frequently assume leading roles in environmental stewardship and informal recycling economies.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data from the structured interviews, participatory workshops, and field observations were analyzed using thematic analysis. All audio recordings and notes from the interviews and workshops were transcribed and manually coded to identify recurring patterns and emerging themes aligned with the study objectives. Selected interview responses were further quantified, with frequencies and percentages calculated to complement the qualitative analysis and illustrate patterns of engagement in waste management practices.

Observation data were systematically reviewed and categorized to corroborate and enrich findings from verbal accounts. Themes were developed inductively and compared across the three data sources, thereby ensuring triangulation. This analytical approach facilitated a comprehensive understanding of participants’ experiences, collective perspectives, and observable practices within their contextual settings.

3. Results

3.1. Participants Profile by Age Group and Gender

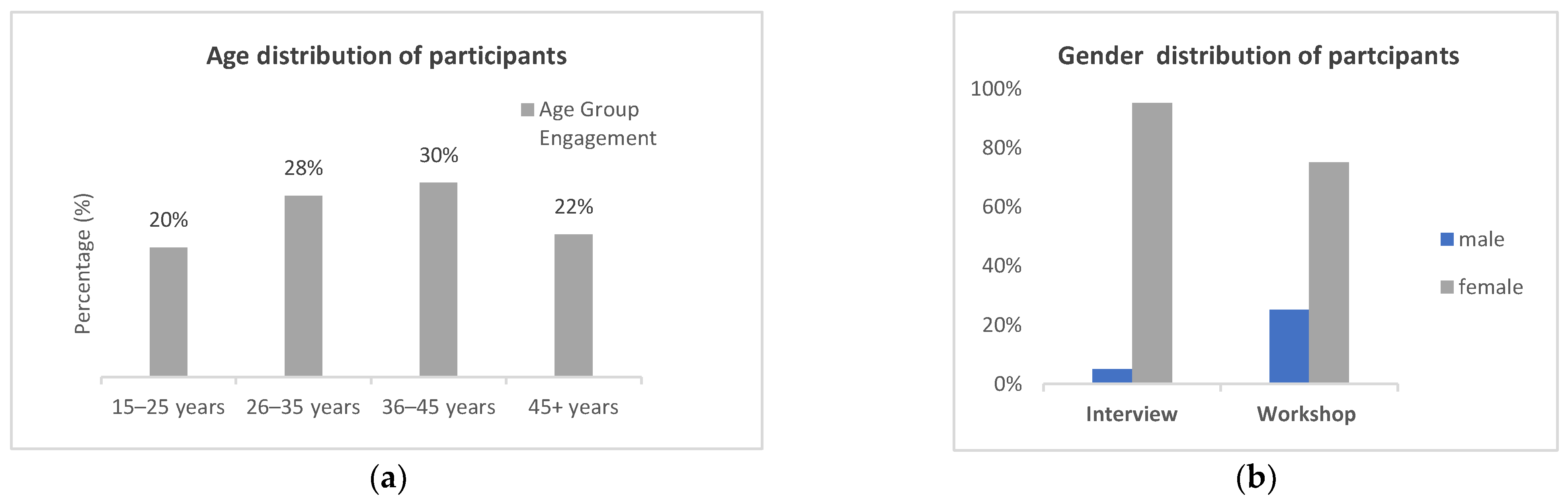

Findings from the community interviews indicated a relatively balanced age distribution among participants, with 20% aged 15–25 years, 28% aged 26–35 years, 30% aged 36–45 years, and 22% aged 45 years and above (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

(a): Participants distribution by age group. (b): Participants distribution by gender.

The majority of individuals engaged in plastic waste management were women, comprising 95% of interview respondents and 75% of workshop participants (Figure 2b). These results underscore the pivotal role of women in local plastic waste management and suggest that community-based interventions should prioritize their engagement to strengthen participation and overall effectiveness.

3.2. Types of Plastic Waste in Local Communities

The tourism sector in Zanzibar is a major source of local plastic waste. Single-use plastics especially bottled water, food packaging, and disposable utensils from hotels dominate the waste stream, with minimal segregation or recycling. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) bottles transferred to households are reused to store liquids (water, oil, milk, honey, soap) and dry goods (tea, spices). Despite extending their utility, limited durability and the lack of recycling infrastructure mean most PET bottles eventually enter dumpsites or coastal areas (Figure 3 and Figure 4). High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) plastics, mainly from packaging, are the second most prevalent waste type. These patterns reflect the short-term convenience of tourism-driven plastics and highlight systemic challenges in local waste management.

Figure 3.

Plastic waste accumulation on Kendwa beach (Source: Property common).

Figure 4.

Disposal of waste at the nearby collection point in Paje (Source: Author, 2024).

3.3. Waste Collection and Transportation Systems in the Study Area

In rural coastal areas such as Kendwa, Nungwi, Jambiani, Paje, and Michamvi, district councils are responsible for waste collection and disposal. Larger hotels generally manage their waste through contracts with private contractors hired by the councils, who transport it to the designated landfill at Kibele or other designated dumpsites. However, a clear gap exists once waste enters the community. Many smaller hotels, restaurants, and households lack access to formal waste services. They often rely on informal collectors or dispose of waste in unregulated open spaces, such as roadside pits, vacant plots, or beaches, without proper oversight.

Even with formal contracts in place, field observations reveal that waste collection trucks often operate uncovered and carry mixed waste, undermining efforts to separate recyclables and manage waste responsibly (Figure 5). Additionally, some local waste collectors, constrained by long distances to official dumpsites and operational limitations such as insufficient or unreliable vehicles, poor road access, fuel shortages, and lack of maintenance resort to open or illegal dumping. Although such practices are prohibited, they persist, reflecting systemic shortcomings in the waste management framework (Figure 6). This disconnection between formal waste management at larger hotels and informal community-level practices presents significant challenges for effective waste control in these coastal villages.

Figure 5.

Uncovered truck transporting waste from Michamvi to the disposal site (Source: Author, 2024).

Figure 6.

Hotel waste improperly disposed in nature at Nungwi (Source: ZANREC).

Interviews with contractors suggest that insufficient compensation for transportation costs to official dumpsites exacerbates inefficiencies, prompting some to resort to informal dumping. Transporting waste to official sites is often considered cost-ineffective. District councils, responsible for overseeing hotel waste collection, set collection fees based on hotel size. As a result, hotel owners incur higher waste management costs but often negotiate lower service fees that do not fully cover transport and disposal expenses. This financial imbalance can create incentives for waste collection companies to engage in improper disposal practices with contractors suggest that insufficient compensation for transportation costs to official dumpsites exacerbates inefficiencies, prompting some to turn to informal dumping methods. This occurs because transporting waste to official sites is considered cost-ineffective. District councils, responsible for overseeing waste collection from hotels, set collection fees based on the size of the hotel. As a result, hotel owners incur higher waste management costs, yet they often negotiate lower service fees that do not fully cover transport and disposal expenses. This financial imbalance can create incentives for waste collection companies to engage in improper disposal practices.

3.4. Waste Recovery, Reuse, and Treatment Practices

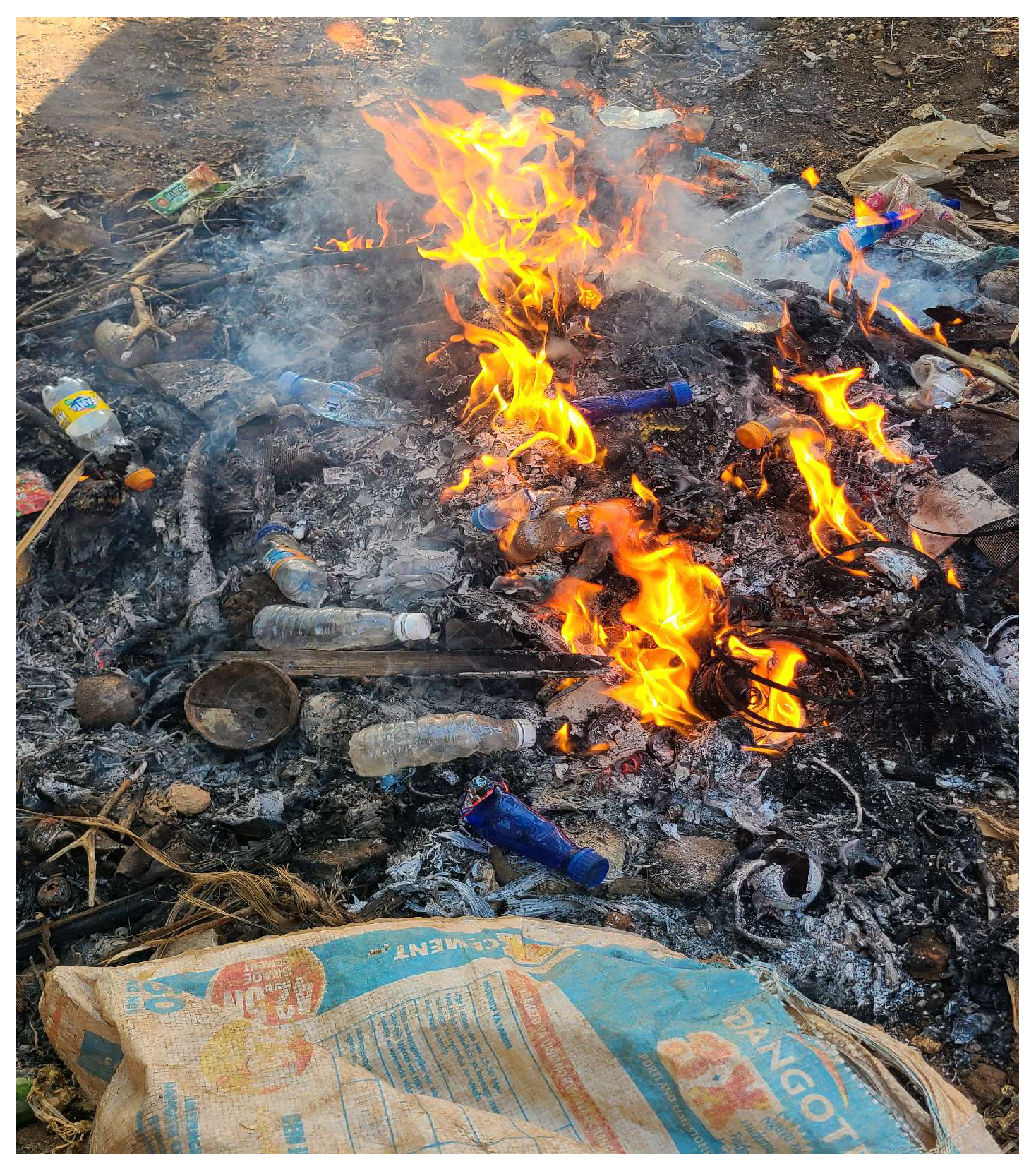

Field observations identified several common practices for managing plastic waste, including open burning (Figure 7), reuse, disposal in pits, indiscriminate backyard dumping, and open dumping. However, emerging efforts in Nungwi and Kendwa show promise: community groups collect discarded plastics to transform them into handcrafted items, and children participate in swop-shops, collecting plastics and exchanging them for valuable materials through a program supported by a professional waste management company.

Figure 7.

Open burning of plastic in a backyard in Kendwa (Source: Author, 2024).

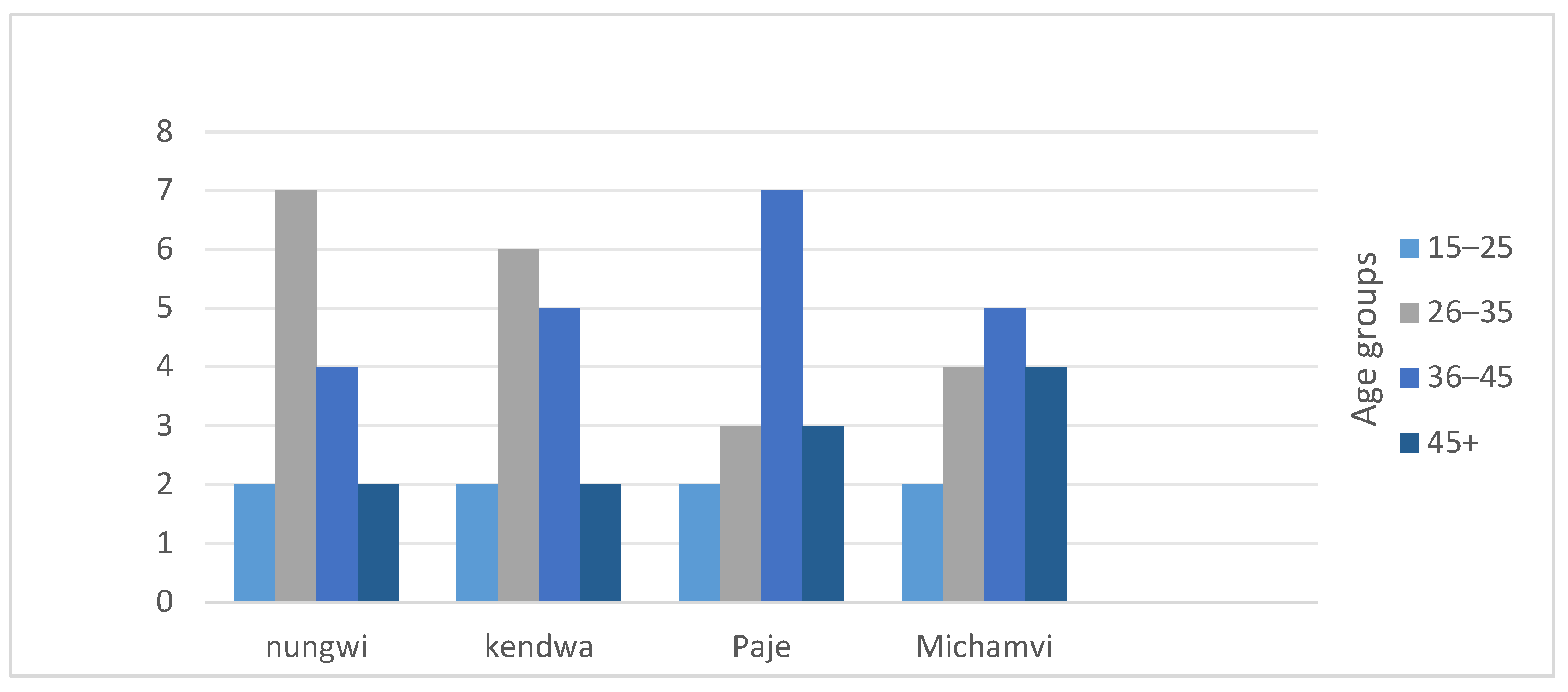

3.5. Community Participation Across Locations and Age Groups

Patterns of engagement across the study sites showed some geographic variation. In Nungwi and Kendwa, the most active groups were young adults aged 26–35 and adults aged 36–45, reflecting the overall age profile of the sample. In Paje, engagement was highest among adults aged 36–45, followed closely by older adults aged 45 and above, suggesting a stronger role for senior community members in local waste initiatives (Figure 8). By contrast, Michamvi exhibited generally low and uneven participation across all age groups, with particularly limited involvement from youth aged 15–25. These variations highlight how age and location influence participation dynamics, underscoring the need for tailored engagement strategies that reflect local demographic realities. Observations with a structured checklist revealed notable differences in plastic collection and recycling practices across the four study villages (Table 3).

Figure 8.

Community Engagement in Plastic Waste Collection and Recycling across communities.

Table 3.

Observational Checklist Results on Plastic Collection and Recycling Activities in Study Villages.

In Nungwi, plastic waste management appeared deeply embedded in daily routines, supported by a strong presence of NGOs and proactive involvement from the district council. Community-led initiatives were also highly visible and frequent. Kendwa showed a similarly high level of activity, with swop-shops, partnerships between hotels and local communities, and youth-driven education efforts all contributing to an active waste management culture. Paje reflected a more moderate level of engagement, with occasional clean-up events, school involvement, and some support from swop-shops. By contrast, Michamvi exhibited limited activity: there were no visible recycling programs or community incentives, and little evidence of infrastructure to support organized plastic collection. While promising, these initiatives are limited to specific areas, and neighboring communities lack access to similar services, highlighting disparities in waste management practices across the study sites (Table 3).

3.6. Disposal and Final Treatment Methods

Few environmentally conscious hotels in the study area are working alongside local communities and environmental initiatives to address the growing issue of plastic waste. These hotels collaborate with organizations such as Chako Zanzibar, Kawa Environmental Club, Recycle at OZTI, and Zanrec to implement sustainable waste management practices. Chako Zanzibar focuses on waste sorting, turning waste into art, raising awareness, spreading knowledge, and promoting female empowerment through its programs. Kawa Environmental Club organizes community clean-ups and educational initiatives to foster a deeper understanding of waste reduction. Recycle at OZTI collects plastic waste from hotels and neighboring communities for recycling, while Zanrec manages and processes waste, providing collection and recycling services.

Despite these efforts, challenges remain, including community perceptions of plastic waste, limited space for sorting and recycling infrastructure, and inadequate waste management systems. Many respondents in interviews expressed the view that plastic waste is simply something to be collected and taken to landfills. One middle-aged woman reflected, “We need to rethink our mindset of plastic and find better ways to manage it.” Another commented, “It’s somehow disappointing. Instead of benefiting from hotel investments, we witness improper hotel waste management.” A young woman added, “Waste is waste as far as it is not needed anymore, regardless of whether it’s plastic or something else. The best option is to do away with it.” Another participant expressed frustration: “I wonder what the district is doing. The hoteliers pay for the waste to be properly collected; why should it be us doing it?”

In response to such concerns, the CEO of Zanrec explained, “The company has taken proactive steps by setting up collection points in various locations where locals can exchange plastic waste for school items such as books, uniforms, and school bags, thereby fostering community participation in waste reduction while addressing local needs.” However, this approach has drawn criticism from some community members. These contrasting views underscore the complexities and challenges of promoting effective waste management strategies that are both sustainable and inclusive of community needs and concerns.

3.7. Challenges and Opportunities in Managing Plastic Waste in the Study Area; Insight from Participatory Workshop

Key challenges observed include weak strategic planning, insufficient recycling facilities, and logistical and operational barriers, such as inadequate infrastructure and high transportation costs particularly for long-distance routes from Michamvi and Paje to the Kibele landfill or recycling firms, most of which are located in urban areas. As one waste management personnel remarked, “We would like to establish a recycling facility nearby, but we lack a suitable location. Despite several discussions with district officials, they don’t seem to support our idea.”

In line with this view, a young entrepreneur in her thirties added, “If municipalities and district councils could facilitate relationships among different stakeholders in waste management, plastic waste issues could be significantly reduced.” Despite these challenges, significant opportunities exist within the growing ecosystem of local solutions, demonstrating the potential for more sustainable and community-driven plastic waste management.

3.8. Insights from Participatory Workshops

During participatory workshops, several key themes emerged regarding strategies to enhance local waste management. First, the importance of community education was strongly emphasized. Educating communities to promote sustainable waste practices and forming partnerships with local businesses and NGOs were viewed as critical for increasing recycling and upcycling rates. Approximately 20% of workshop participants highlighted that empowering residents through community-led initiatives could substantially improve local waste management outcomes. Participants also underscored the need for targeted incentives to encourage businesses to adopt sustainable practices and invest in recycling technologies. Specific recommendations included:

3.8.1. Establishment of Training Programs for the Waste Management Workforce

Participants recommended that district councils partner with existing waste initiatives in Zanzibar, drawing inspiration from the UNICEF–UNDP WasteX Lab model at the State University of Zanzibar (SUZA), which offers infrastructure, mentorship, and a circular economy curriculum to strengthen local initiatives. This approach was considered promising for supporting locally adapted training for waste collectors, informal workers, and council staff, especially in under-served areas like Michamvi and Paje, to improve skills in plastic waste sorting and small-scale recycling.

3.8.2. Enhancement of Public Awareness Campaigns

Drawing on initiatives led by existing recycling efforts such as Recycle at OZTI, Kawa, Chako, and Zanrec, participants recommended replicating these models across Unguja and rural communities. They emphasized investing in Swahili radio, village meetings, and school curricula to effectively communicate the importance of plastic segregation and proper disposal.

3.8.3. Investment in Local Technologies

Support for small-scale recycling and up-cycling units was seen as vital for reducing waste and creating value from recycled materials. In Zanzibar, initiatives like Chako involve communities in collecting and transforming plastic waste into handcrafted products, providing both environmental and economic benefits. Similarly, the Destination Zero Waste project by the TUI Care Foundation establishes small recycling hubs that train local entrepreneurs to upcycle plastic into marketable goods. Scaling such models through collaboration with local authorities and NGOs was identified as a crucial platform for reducing waste and creating economic opportunities within local communities.

3.8.4. Promotion of Eco-Friendly Packaging Solutions

Participants recommended using local materials such as banana leaves, palm fronds, and cassava starch to develop biodegradable packaging. In Zanzibar, banana leaves are already used informally and could be scaled for wider use. Participants cited similar approaches in Thailand and Vietnam, where supermarkets adopt banana leaf packaging, while innovations from India have extended the durability of such materials for commercial use. Adapting these models locally—particularly within food markets, street vending, and hotel supply chains—was linked to reducing plastic waste, supporting green entrepreneurship, and aligning with Zanzibar’s sustainable tourism goals.

3.8.5. Implementation of Low-Cost Waste Sorting Machines

Participants recognized low-cost waste sorting machines as effective tools for improving segregation efficiency and separating recyclable plastics from other waste types. They proposed introducing such machines at community-level or informal collection centers to reduce contamination and increase recycling rates. Using innovation hubs at technical institutions such as the Karume Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) and the Institute of Tourism at SUZA, locally appropriate prototypes could be designed, fabricated, and piloted. Drawing from successful examples in Kenya and India, participants emphasized the potential for replicating similar technologies in areas like Michamvi and Paje.

3.8.6. Development of Mobile Messaging Platforms or Apps

Participants suggested utilizing existing digital platforms and services provided by major telecom companies such as Tigo, Mixx by Yas, Halotel, and Airtel, as well as other locally available mobile network operators, to promote waste segregation and recycling. These platforms could disseminate timely information on waste collection schedules, recycling points, and recyclable materials, while encouraging responsible consumer behavior and fostering a culture of sustainability.

A recurring theme among participants was the critical role of waste sorting. It was widely agreed that sorting waste constitutes a vital first step toward sustainable waste management, even in areas lacking formal recycling infrastructure. Sorting reduces landfill burden, conserves resources, and lays the foundation for future recycling initiatives. Evidence from other contexts shows that while sorting may not immediately translate into recycling due to infrastructural limitations, it remains a critical precursor for the eventual establishment of local recycling industries. For instance, a study in China by Tan et al. [13] demonstrates that waste sorting enhances recycling rates, resource recovery, and pollution reduction but is only effective when adapted to local characteristics and resources. Building on these insights, there is an urgent need to advance closed-loop, community-driven circular economy models by scaling up local initiatives to strengthen plastic governance, reduce environmental pollution, and generate livelihood opportunities.

- Proposed Hybrid Waste Bank Model

This study proposes establishing a hybrid waste bank model integrated with existing swop-shops, supported by capacity-building initiatives to enable recycling or upcycling of sorted waste.

A waste bank is a community-based waste management system where households deposit sorted recyclable materials (e.g., paper, plastics, glass, and metals) that are weighed, valued, and recorded as savings. Administrators manage storage and resale of recyclables to larger buyers or central banks, while residual waste is directed to landfills or occasionally repurposed. In this way, waste banks integrate household participation with local recycling markets and incentivize circular-economy practices.

Waste banks have emerged as a practical and sustainable approach to improving municipal solid waste (MSW) management through recycling, while simultaneously enhancing environmental and economic outcomes when aligned with local initiatives [42]. Evidence from low- and middle-income countries demonstrates that such programs effectively strengthen waste management systems and promote active community participation. For example,

In Tanga City, Tanzania, the Waste Banks project, led by the Taka Ni Ajira Foundation and the UNDP Accelerator Lab, supports marginalized waste pickers and promotes a circular economy through digital tools and social incentives [43].

In Lagos, Nigeria, Wecyclers collects recyclables from households using low-cost cargo bicycles; residents earn points redeemable for goods and services, increasing recycling participation [44].

In Cairo, Egypt, the Zabbaleen community operates decentralized waste banks, recycling up to 80% of waste and creating upcycled products, providing income and improving local waste management [45].

In Indonesia, the Bank Sampah system encourages residents to separate recyclables and deposit them at local waste banks, with transactions recorded in customer accounts or bank lists [46].

In Thailand, school-based waste bank initiatives have successfully changed recycling habits, engaging students and communities for long-term participation [47].

These examples demonstrate that waste bank systems can be adapted to diverse contexts, effectively supporting both environmental and social goals, and serve as a practical model for the region. The operation and sustainability of the waste bank model are grounded in core activities, including waste collection, sorting, storage, and resale. Table A1 in the Appendix A presents a financial analysis of a waste bank system, using prices from existing initiatives in mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar [48,49]. This analysis illustrates potential funding sources, revenue streams, costs, and savings, providing a practical framework for assessing economic feasibility and sustainability. By consistently supplying high-quality recyclable materials to buyers and maintaining efficient logistics, the waste bank can strengthen financial stability while fostering long-term community participation.

- Strategies to Enhance Waste Bank Programs

- 1.

- Community Engagement & Education

- Conduct awareness campaigns in schools, local markets, and cultural/religious gathering spaces to teach the importance of waste segregation and recycling.

- Organize household-level sorting workshops to equip individuals with practical waste management skills.

- Responsible: Waste bank coordinators, local leaders through sheha committees, and volunteers.

- 2.

- Youth and School Involvement

Establish school Eco-clubs and youth groups to collect and deposit recyclables, fostering responsibility and environmental stewardship.

- Responsible: Teachers, school eco-club leaders, student volunteers.

- 3.

- Environmental Clean-ups

Organize beach clean-ups to maintain a continuous supply of materials while reducing environmental pollution.

- Responsible: Community volunteers, youth groups, NGOs, local authorities, hoteliers.

- 4.

- Practical Recycling & Up-cycling

- Implement small-scale plastic shredding and baling for easier sale to recyclers.

- Conduct upcycling workshops to transform waste into crafts, furniture, and bricks, drawing on successful experiences from Kenya [48] and Ivory Coast [49,50].

- Responsible: Waste bank administrators, local artisans, technical trainers.

- 5.

- Youth-Led Waste-to-Wealth Initiatives

Engage young people in transforming waste into useful products, generating income, building skills, and supporting environmental sustainability, as demonstrated in the Maldives [51].

- Responsible: Youth entrepreneurs, NGOs.

By implementing these strategies, the waste bank can strengthen financial viability, maximize environmental impact, and empower youth and women as active participants in sustainable waste management.

4. Discussion

This study examined the dynamics of plastic waste management in Zanzibar’s tourism-dependent economy, focusing on community participation, gender equity, material-specific challenges, private sector engagement, and the role of tourism as a driver of plastic pollution. By situating local practices within global sustainability frameworks, the findings highlight both context-specific insights and their transferability to other small island developing states (SIDS). The discussion is organized around key thematic areas that emerged from the study.

4.1. Community Participation and Socioeconomic Drivers

Participation in plastic waste management is strongly influenced by the interplay of socioeconomic ties to tourism, prevailing cultural norms, and the availability of structured interventions. Initiatives such as Swop Shops demonstrate the potential to embed sustainable practices into daily routines; however, their long-term effectiveness depends on accessibility, program continuity, and alignment with local cultural values. The study revealed age-related differences in engagement: younger adults were primarily motivated by economic incentives, whereas older adults were guided by a sense of custodianship and responsibility for community well-being. These findings suggest that interventions integrating both economic and cultural motivations may achieve broader participation and sustainability. Comparable evidence from the Maldives [50] and the Pacific Islands [52] indicates that these insights may be transferable to other tourism-dependent coastal regions. Collectively, these observations highlight the importance of multi-sectoral strategies that leverage cultural values and livelihood opportunities to strengthen ownership, long-term commitment, and applicability beyond Zanzibar.

4.2. Gender Equity in Waste Management

Zanzibar’s waste sector reflects global gendered divisions, with women often engaged in low-paying, labor-intensive sorting, while men occupy supervisory positions. This pattern mirrors evidence from Ghana [52,53] and other contexts [54], where systemic inequalities limit women’s economic gains from waste work. Data from the 2024 National Bureau of Statistics indicate that women remain underrepresented at managerial levels, accounting for only 28% of senior and middle managers [55]. Empowering women through leadership opportunities, targeted training, and inclusive decision-making enhances equity and overall system effectiveness. Comparable initiatives in Mauritius [56], where women play central roles in community-based recycling enterprises, suggest that gender-responsive strategies can be applied in other tourism-dependent economies. These findings underscore the importance of integrating gender equity considerations into policy and program design to promote inclusivity and sustainable waste management outcomes.

4.3. Material-Specific Challenges: PET and HDPE

PET bottles dominate Zanzibar’s waste stream, largely due to tourism-related consumption of bottled water. While widely used, PET is poorly suited for long life cycles and poses health and environmental risks when reused [57]. In contrast, HDPE plastics are more durable and safer for reuse but remain under-recovered due to weak collection systems and contamination. Addressing these challenges requires targeted awareness campaigns, differentiated recycling strategies, and promotion of safer material alternatives. Similar PET–HDPE dynamics have been observed in the Maldives [50], where high bottled water imports contribute to PET accumulation, and in Fiji, where HDPE recovery is constrained by inadequate infrastructure [52,53]. These parallels suggest that material-specific waste management strategies, tailored to the characteristics of dominant polymers, may be transferable across SIDS experiencing tourism-driven plastic pollution.

4.4. Private Sector and Multi-Sector Partnerships

Private initiatives by organizations such as Zanrec, Chako, Recycle at OZTI and Kawa complement formal waste management systems in Zanzibar but face challenges in scaling without supportive policies. Key enablers include subsidies for recycling infrastructure, tax incentives for businesses using recycled materials, and development of markets for secondary products [58,59]. Cross-sector partnerships involving government agencies, private enterprises, NGOs, and research institutions are critical to integrated solutions. Experiences in Mauritius, where hotel–recycler collaborations have strengthened waste recovery, and in the Maldives [50], where resort-level segregation is promoted through policy incentives, illustrate the broader applicability of these approaches. Zanzibar’s public–private partnership models provide transferable insights for other SIDS seeking effective, integrated strategies for sustainable waste management.

4.5. Tourism as a Driver of Plastic Pollution

These findings extend existing knowledge by demonstrating that the tourism sector, due to its rapid growth in Zanzibar, is an emerging and significant contributor to plastic pollution. Single-use plastics in hotels, particularly bottled water, food packaging, and disposable utensils accounted for the largest proportion of waste generated on-site, with limited segregation or recycling. This contrasts with earlier studies on coastal environments, which primarily emphasized household and industrial sources of plastic leakage. The prevalence of these materials highlights the need for sector-specific interventions, including hotel-based waste reduction strategies, adoption of reusable alternatives, and stakeholder engagement initiatives.

4.6. Linking Local Insights to Global Frameworks

By situating these results within global sustainability frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Global Tourism Plastics Initiative, this study emphasizes the value of integrating local knowledge with international best practices. Linking cultural, economic, and institutional realities with these frameworks can guide context-sensitive strategies that are effective locally and adaptable to other tourism-dependent economies.

4.7. Synthesis and Implications

Zanzibar’s case demonstrates that effective plastic waste management requires integrated strategies that combine community participation, gender and youth inclusion, material-specific handling, and behavior-change interventions supported by multi-sectoral collaborations. When aligned with local institutional capacities and governance structures, these strategies become more feasible and sustainable. Furthermore, linking these approaches with international frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Global Tourism Plastics Initiative provides additional guidance and legitimacy, offering actionable insights for designing resilient and sustainable waste management systems in tourism-dependent economies and other small island developing states.

5. Conclusions

Effective management of plastic waste in Zanzibar requires a coordinated, context-sensitive, and inclusive framework. Socio-demographic and institutional conditions strongly influence levels of participation, underscoring the necessity of strategies that meaningfully engage diverse population groups. Addressing entrenched gendered divisions in waste-related tasks is particularly important for advancing equity and harnessing the full potential of the available workforce. Moreover, material-specific challenges, such as those associated with PET and HDPE, highlight the need for differentiated technical solutions and tailored policy measures. Operational inefficiencies, including fragmented collection networks and inconsistent sorting practices point to an urgent requirement for standardized procedures and enhanced institutional capacity. In parallel, gaps between community perceptions and sustainable waste practices emphasize the importance of targeted awareness programs and behavior change interventions. Although several innovative, locally driven initiatives demonstrate promising results, their broader impact will depend on the establishment of robust partnerships among public authorities, private operators, and civil society organizations. A systems-thinking approach, grounded in collaboration, inclusivity, and adaptability, is therefore essential to building resilient and scalable frameworks for plastic waste governance in Zanzibar. Complementary developments, such as the Sustainable Tourism Declaration, the Greener Zanzibar Campaign, and the 1 July directive, signal a positive shift toward embedding sustainability within the tourism sector. However, achieving these ambitions will require stronger policy enforcement, greater clarity in regulatory frameworks, and the introduction of meaningful incentives to encourage circular waste practices. With targeted investment and coordinated implementation, these initiatives hold the potential to transcend symbolic action and catalyze systemic transformation toward a greener and more sustainable Zanzibar.

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study generates both theoretical and practical insights for advancing plastic waste management in tourism-dependent contexts such as Zanzibar. From a theoretical perspective, it challenges the adequacy of top-down or standardized interventions, instead lending support to participatory governance frameworks that emphasize inclusion and local agency. The findings demonstrate how socio-cultural factors—including local knowledge, gendered responsibilities, and inter-generational relations—shape waste practices. In doing so, the study extends community-based environmental management models by highlighting the importance of treating communities as active co-creators rather than passive recipients in the transition toward a circular economy.

From a practical standpoint, the results provide actionable guidance for policymakers, non-governmental organizations, and tourism stakeholders. Programs are shown to be more effective when designed collaboratively with communities, carefully attuned to local needs, spatial realities, and social structures. Ensuring that under-served areas such as Michamvi receive investment in basic infrastructure and communication systems emerges as a critical priority. Furthermore, connecting waste practices to income-generation opportunities exemplified by initiatives like Swop-shops—can strengthen participation, stimulate local pride, and reinforce behavioral change. Actively empowering women, alongside engaging both younger and older generations in program design, enhances inclusivity and contributes to the long-term sustainability of interventions. Collectively, these insights offer a road-map for developing inclusive, circular waste systems that can be adapted and transferred to other coastal or tourism-reliant regions.

6.1. Limitations & Delimitation

This study focused on the northern and southern districts of Unguja Island, specifically Kendwa, Nungwi, Paje, and Michamvi (Figure 1), deliberately targeting high-tourism coastal areas and prioritizing hotels, restaurants, and local communities as units of analysis. While these sites provide valuable insights into tourism-driven waste challenges, the concentration on four areas limits the generalizability of the findings across Zanzibar. The absence of detailed tourist arrival data necessitated the use of hotels, rooms, and beds as proxies for tourism intensity, and the relatively short study period restricted the ability to capture seasonal variations. Other sectors and less tourism-intensive regions were excluded to ensure analytical depth within the available time-frame and resources. Nonetheless, these limitations do not diminish the contribution of the study, which offers the first systematic account of plastic waste governance in Zanzibar’s tourism-dependent coastal zones and provides actionable insights for policy and practice.

6.2. Future Research Directions

Future research should adopt longitudinal designs to better capture seasonal dynamics and integrate detailed tourism indicators such as arrivals and occupancy rates. Expanding to regions with lower hotel density and cross-island comparisons would enhance generalizability. Further studies should also assess policy enforcement, economic instruments, and behavioral incentives to support inclusive, circular waste systems.

Author Contributions

A.A., A.R., S.H. and B.A. conceptualized the study. A.A., B.A. and F.S. designed the study. A.A. and B.A. collected field data. A.A. performed data analysis and wrote the original draft. F.S., A.R. and S.H. supervised the study and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was part of a PhD project funded by Danida, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, through the Building Stronger Universities Phase 3 project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Zanzibar Health Research Ethical Committee (ZAHREC/03/PR/Nov/20/19/003) on 11 November 2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants following a comprehensive explanation of the study. Verbal consent was obtained rather than written, as the majority of participants opted for verbal consent despite their recognition that the written consent form had been prepared.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The researcher would like to express sincere gratitude to all the participants and stakeholders who contributed to this research study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Waste Bank Financial Analysis.

Table A1.

Waste Bank Financial Analysis.

| 1. Capital Investment (Initial Costs) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Estimated Cost (USD) | ||||||

| Collection Points | 1200 | ||||||

| Sorting Area Setup | 2000 | ||||||

| Digital/Manual Logbook | 500 | ||||||

| Protective Equipment | 300 | ||||||

| Transportation | 3500 | ||||||

| Total Initial Cost | 7500 | ||||||

| 2. Operating Costs (Annual) | |||||||

| Item | Annual Cost (USD) | ||||||

| Staff Wages | 4800 | ||||||

| Fuel & Transport Maintenance | 2000 | ||||||

| Utilities | 600 | ||||||

| Supplies & Consumables | 400 | ||||||

| Communication | 300 | ||||||

| Marketing & Awareness | 500 | ||||||

| Total Annual Operating Cost | 8600 | ||||||

| 3. Potential Funding Sources | |||||||

| |||||||

| 4. Revenue Streams | |||||||

| |||||||

| 5. Revenue Projection (Year 1–3) | |||||||

| Assuming each household sells 2 kg per day | |||||||

| Year | Households | Waste Collected (kg/year) | Sale of Recyclables (USD) | Membership Fees (USD) | Other Income (USD) | Total Revenue (USD) | |

| 1 | 300 | 219,000 | 6800 | 3600 | 500 | 10,900 | |

| 2 | 400 | 292,000 | 9100 | 4800 | 1000 | 14,900 | |

| 3 | 500 | 365,000 | 11,300 | 6000 | 1500 | 18,800 | |

| 6. Break-even Analysis | |||||||

| Annual operating cost: USD 8600 | |||||||

| Year 1 revenue: USD 10,900 | |||||||

| Break-even achieved in Year 1 if prices & participation are stable. | |||||||

| The price ranges used in this analysis were obtained from [40,41] | |||||||

References

- Faber, B.; Gaubert, C. Tourism and economic development: Evidence from Mexico’s coastline. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 2245–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Travel & Tourism Global Economic Impact & Trends; WTTC: London, UK, 2023; Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook Update, July 2024: The Global Economy in a Sticky Spot; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Santos, R.A.; Méxas, M.P.; Meiriño, M.J.; Sampaio, M.C.; Costa, H.G. Criteria for assessing a sustainable hotel business. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 121347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xie, X.; Wang, S.; Lv, L.; Luo, H. Measurement of tourism-related CO2 emission and the factors influencing low-carbon behavior of tourists: Evidence from protected areas in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, I.R.; Maniruzzaman, K.M.; Dano, U.L.; AlShihri, F.S.; AlShammari, M.S.; Ahmed, S.M.S.; Al-Gehlani, W.A.G. Environmental sustainability impacts of solid waste management practices in the Global South. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hira, A.; Pacini, H.; Attafuah-Wadee, K.; Vivas-Eugui, D.; Saltzberg, M.; Yeoh, T.N. Plastic waste mitigation strategies: A review of lessons from developing countries. J. Dev. Soc. 2022, 38, 336–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrah, J.; Teye, G.; Dinis, M. Barriers and challenges to waste management hindering the circular economy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Urban Sci. 2022, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, N.; Maalouf, J. A review of plastic waste circular actions in seven developing countries to achieve sustainable development goals. Waste Manag. Res. 2023; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Zanzibar Tourism Satellite Account: Estimating the Contribution of Tourism to the Economy of Zanzibar; UN ECA: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022; Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10855/47591 (accessed on 18 May 2024).

- UNICEF. Impact of Tourism on Communities and Children in Zanzibar; UNICEF: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/tanzania/media/2196/file/Impact%20of%20Tourism%20on%20Children%20and%20Communities%20in%20Zanzibar.pdf (accessed on 28 July 2023).

- World Bank. Zanzibar: A Pathway to Tourism for All: Integrated Strategic Action Plan; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; pp. 1–58. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/9937015652505/77192Zanzibar-A-Pathway-to-Tourism-for-All-Integrated-Strategic-Action-Plan (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Tan, S.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M. Exploring paths underpinning the implementation of municipal waste sorting: Evidence from China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukali, I. Enhancing Circular Economy and Waste Management in Zanzibar by Leveraging Young Entrepreneurship and Innovation. Master’s Thesis, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden, 2023. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1769359/fulltext01.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- European Commission. Horizon Projects Supporting the Zero Pollution Action; Mission Soil Platform: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://mission-soil-platform.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-08/horizon%20projects%20supporting%20the%20zero%20pollution%20action-KI0622125ENN.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Down to Earth. In hope of a plastic waste-free island. Down To Earth. 2018. Available online: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/waste (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Dauvergne, P.; Poole Lehnhoff, K. The power of biojustice environmentalism in the Global South: Insights from the politics of reducing single-use plastics in Guatemala. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, N.I.; Masuk, M.; Safayet, R. Plastic waste: Challenges and opportunities to mitigate pollution and effective management. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2023, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, D. Community engagement in waste management and recycling: Best practices and success stories [Short communication]. J. Environ. Waste Manag. Recycl. 2023, 6, 128. Available online: https://www.alliedacademies.org/articles/community-engagement-in-the-waste-management-and-recycling-best-practices-and-success-stories-26057.html (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Oppong, C.; Mathibe, M.S. Women’s role in promoting sustainable development through stakeholder engagement and environmental policy: African perspectives on the circular economy. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2024, 7, e70051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maione, C. Quantifying plastics waste accumulations on coastal tourism sites in Zanzibar, Tanzania. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 168, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen, L.F.; Pedersen, S.; Thøgersen, J. Drivers of and barriers to consumers’ plastic packaging waste avoidance and recycling—A systematic literature review. Waste Manag. 2022, 141, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Wang, H.; Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Vatin, N.I.; Mohamed, A.M.; Deifalla, A.F.; Mehmood, I. Plastic waste management strategies and their environmental aspects: A scientometric analysis and comprehensive review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, M.; Dhiman, A.; Kansal, A.; Subudhi, S.P. Plastic waste management for sustainable environment: Techniques and approaches. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2023, 5, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Azad, N.; Dutta, D.; Yadav, B.; Kumar, S. A critical review and future perspective of plastic waste recycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deus, B.C.T.; Costa, T.C.; Altomari, L.N.; Brovini, E.M.; Brito, P.S.D.; Cardoso, S.J. Coastal plastic pollution: A global perspective. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 203, 116478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP); One Planet Network. Global Tourism Plastics Initiative; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021; Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/sites/default/files/2021-12/GTPI_Report2021_veryfinal.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- One Planet Network. Global Tourism Plastics Initiative 2023 Report; One Planet Network: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.oneplanetnetwork.org/programmes/sustainable-tourism (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Gutberlet, J.; Besen, G.R.; de Morais, L.C. Participatory solid waste governance and the role of social and solidarity economy: Experiences from São Paulo, Brazil. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentina, T.R.; Putera, R.E.; Salsabila, L. Collaborative governance in handling the waste crisis: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2025, 20, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatan, O.S.; Adeboyejo, A.T.; Akindele, A.O. The role of stakeholders and technological innovations in enhancing waste governance and service delivery. Pan Afr. J. Health Environ. Sci. 2025, 4, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Local waste management successfully reduces coastal plastic pollution. One Earth 2022, 5, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwadipe, S.; Purchase, D.; Garelick, H.; McCarthy, S.; Jones, H. Mixed method analysis of household recycling challenges and the development of a sustainable recycling indicator. Waste Manag. 2025, 208, 115170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozhikkodan Veettil, B.; Hua, N.T.A.; Van, D.D.; Quang, N.X. Coastal and marine plastic pollution in Vietnam: Problems and the way out. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2023, 292, 108472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.C.M.; Le, P.C.; Quyen, H.H. A study on plastic waste generation and disposal habits in riverside and coastal households towards the promotion of reducing plastic leakage into the ocean in Da Nang City, Vietnam. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 3034–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusba, J.; Pacheco Vélez, C.; Espinosa, L.; Laude, C.; Fuerst, L.; Madera, P.; Valencia, F.; Ángel, N. Plastic pollution in marine coastal areas: Quantifying leakage and evaluating management responses. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 222, 118677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbulú, I.; Rey-Maquieira, J.; Sastre, F. The impact of tourism and seasonality on different types of municipal solid waste (MSW) generation: The case of Ibiza. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Kumar, H.; Nag, A.; Kumar, V. Managing seasonality and overtourism for sustainable tourism development: Challenges and strategies. Int. J. Res. Rev. 2025, 12, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvergne, P.; Poole Lehnhoff, K. The politics of plastic governance in the Global South: Towards justice-oriented approaches. Glob. Environ. Polit. 2024, 24, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R.; Horita, M.; Tasaki, T. Integration of community-based waste bank programs with the municipal solid-waste-management policy in Makassar, Indonesia. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2020, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Tanga City Waste Banks Project: Empowering Waste Pickers Through a Circular Economy; United Nations Development Programme: Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2023; Available online: https://www.tz.undp.org (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Makina, A. Wecyclers Waste Collection: Providing Waste Collection Services in Low-Income Communities; Infrahub Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2023; Available online: https://www.infrahub.africa/case-studies/wecyclers-waste-collection (accessed on 27 April 2025).

- Condé Nast Traveler. Cairo’s Christian Zabbaleen Community Turns Trash into Treasure. 15 March 2023. Available online: https://www.cntraveler.com/story/cairo-egypt-christian-zabbaleen-community (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Project Planet ID. From Trash to Treasure: The Rise of Waste Banks in Indonesia. 2023. Available online: https://www.projectplanetid.com/post/from-trash-to-treasure-the-rise-of-waste-banks-in-indonesia (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- SAIS Perspectives. One Man’s Trash Is Another Man’s Treasure: The Success of Thailand’s Waste Bank Initiative. SAIS Perspectives 2020. Available online: https://www.saisperspectives.com/2020-issue/2020/2/10/one-mans-trash-is-another-mans-treasure-the-success-of-thailands-waste-bank-initiative (accessed on 13 June 2024).

- Honeyguide Foundation. Tanzania Waste Directory: Your Trash Friend; Honeyguide Foundation: Arusha, Tanzania; Available online: https://www.honeyguide.org/seminar_downloads/Tanzania%20Waste%20Directory-%20your%20trash%20friend.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Climate Chance. Plastic Recycling Project and Youth Empowerment (PREYO); Climate Chance: Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://climate-chance.org (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- World Bank. Maldives Is Turning Waste to Wealth, Energizing Youth to Safeguard Its Future. 22 July 2022. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/07/22/maldives-is-turning-waste-to-wealth-energizing-youth-to-safeguard-its-future (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Circle Economy. Smart, Scalable Eco-Brick Schools Made Out of Plastic for Côte d’Ivoire; Knowledge Hub: West Chester, PA, USA, 2022; Available online: https://knowledge-hub.circle-economy.com/cec/article/799 (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Amoah, J.O.; Britwum, A.O.; Essaw, D.W.; Mensah, J. Solid waste management and gender dynamics: Evidence from rural Ghana. Res. Glob. 2023, 6, 100111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Plastic Action Partnership. Gender Analysis of the Plastics and Plastic Waste Sectors in Ghana: Baseline Analysis Report; Global Plastic Action Partnership: Cologny, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Why Gender Dynamics Matter in Waste Management; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2022; Available online: https://www.unep.org/ietc/news/story/why-gender-dynamics-matter-waste-management (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Waste Management World. Breaking Gender Barriers in the Circular Economy. 8 March 2024. Available online: https://waste-management-world.com/resource-use/breaking-gender-barriers-in-the-circular-economy/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Wittmer, J. Dirty work in the clean city: An embodied urban political ecology of women informal recyclers’ work in the ‘clean city’. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2023, 6, 1343–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathicq, B.; Sabatino, R.; Di Cesare, A.; Eckert, M.; Fontaneto, D.; Rogora, M.; Corno, G. PET particles raise microbiological concerns for human health while tyre wear micro-plastic particles potentially affect ecosystem services in waters. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 429, 128397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matee, N.; Kenyan Startup Founder Nzambi Matee Recycles Plastic to Make Bricks That Are Stronger Than Concrete. World Architecture 12 February. 2021. Available online: https://worldarchitecture.org/architecture-news/egmeg/kenyan-startup-founder-nzambi-matee-recycles-plastic-to-make-bricks-that-are-stronger-than-concrete.html (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- UNICEF. UNICEF Breaks Ground on Africa’s First-of-Its-Kind Recycled Plastic Brick Factory in Côte d’Ivoire. 29 July 2019. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/wca/press-releases/unicef-breaks-ground-africas-first-its-kind-recycled-plastic-brick-factory-c%C3%B4te (accessed on 16 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).