Abstract

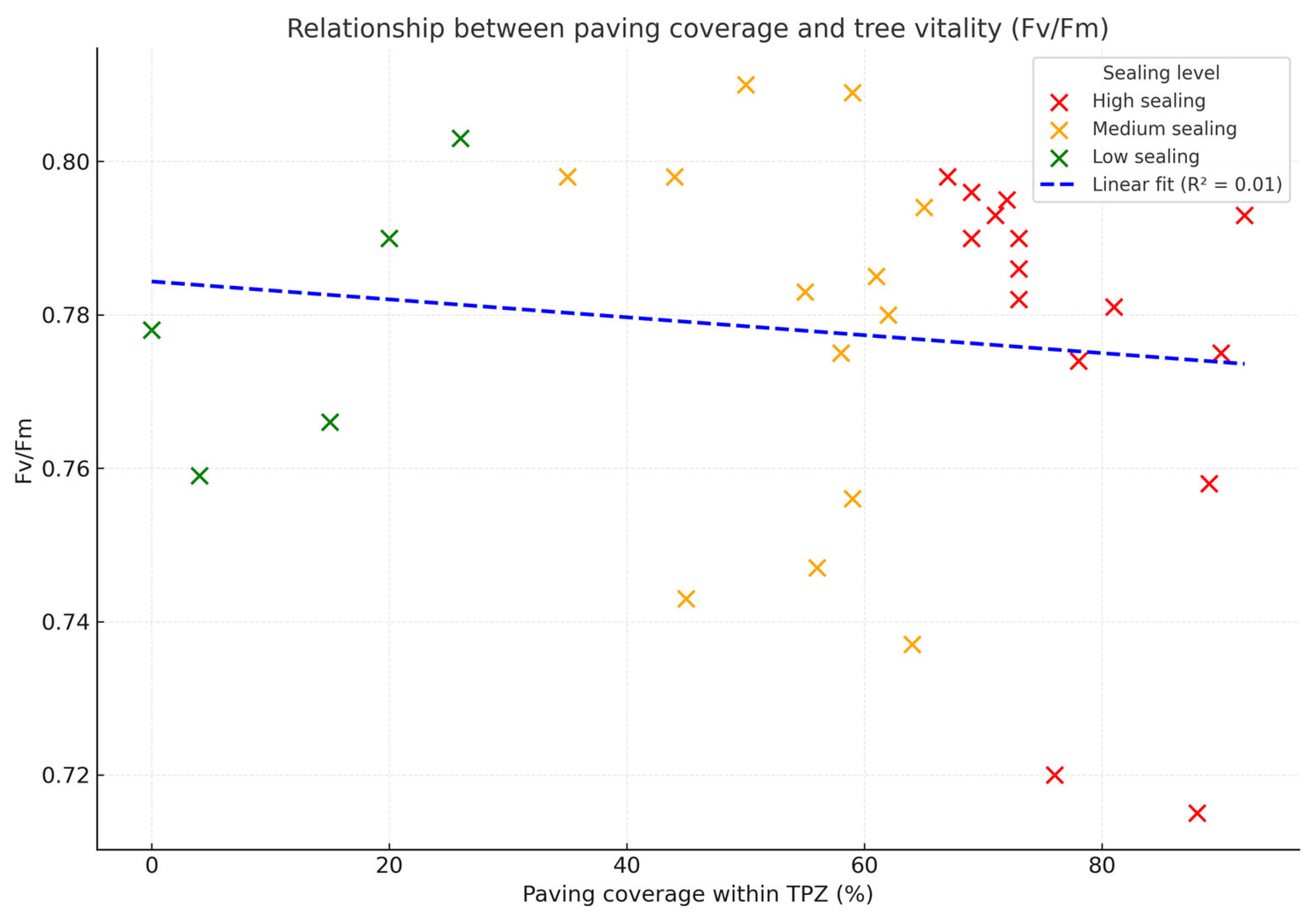

Within the current administrative boundaries of the city of Lublin, fragments of roadside tree avenues of various historical origins and periods of establishment have been preserved, including former tree-lined roads leading to rural and suburban residences from the 18th and 19th centuries. This avenue once led to the manor in Konstantynów and now serves as the main road through the campus of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski—KUL). As one of the last surviving elements of the former rural landscape, the Konstantynów avenue represents a symbolic link between past and future. The research combines acoustic tomography and chlorophyll fluorescence analysis, providing a precise and non-invasive evaluation of the internal structure and physiological performance of 34 small-leaved linden trees (Tilia cordata Mill.). This methodological approach allows for early detection of stress symptoms and structural degradation, offering a significant advancement over traditional visual assessments. The study area is an intensively used urban campus, where extensive surface sealing beneath tree canopies restricts rooting space. The degree of surface sealing (paving) directly beneath the tree canopies was also measured. Based on the statistical analysis, a weak a non-significant weak negative correlation (r = −0.117) was found between the proportion of sealed surfaces within the Tree Protection Zone (TPZ) and the Fv/Fm vitality index, indicating that higher levels of surface sealing may reduce tree vitality; however, this relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.518). The study provides an evidence-based framework for conserving historic trees by integrating advanced diagnostic tools and quantifying environmental stress factors. It emphasizes the importance of improving rooting conditions, integrating heritage trees into urban planning strategies, and developing adaptive management practices to increase their resilience. The findings offer a model for developing innovative conservation strategies, applicable to historic green infrastructure across Europe and beyond.

1. Introduction

Over the course of seven centuries, the city of Lublin has undergone profound economic, demographic, and planning transformations. Population growth, urban expansion, and the synergies generated by these processes have had a direct impact on spatial development and the natural environment of suburban areas. The urbanization of former rural settlements led to significant changes in land use and land cover, an aspect of particular relevance to the present study. Villages and manorial estates were gradually incorporated into the urban fabric, their landscapes transformed by impermeable or semi-impermeable surfaces.

A particularly valuable remnant of this transformation is the historic lime avenue that once led to the suburban manor of the Gałecki family. Today, it functions as the main communication axis within the campus of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, situated in the Konstantynów district in the eastern part of the city. This site offers a unique case study of how historical green structures persist within intensively urbanized environments.

Old trees in urban environments possess exceptional value [1,2,3,4]. Their expansive crowns significantly contribute to the hygrothermal comfort of surrounding spaces, while also providing protection for humans against ultraviolet (UV) radiation [5,6]. Trees reduce ambient temperatures, offering visual comfort and psychological well-being, and at the same time safeguard biodiversity [7,8].

The urban habitat, however, is stressful for trees and far from the optimal conditions of forests or designed parks. Despite this, urban vegetation is expected to perform at its maximum in all aspects—from ecosystem services and environmental regulation to social and aesthetic functions. Unfortunately, urban conditions (reflected and radiated heat, polluted air and soil, compaction, poor drainage, lack of systematic maintenance, heavy traffic load, restricted rooting space, extreme temperatures, and insufficient growing areas) result in roadside and avenue trees living under constant stress [9,10,11,12,13].

Construction activities, road modernizations, underground infrastructure installations, and traffic vibrations frequently cause serious damage to both the above-ground and below-ground structures of trees. This degradation limits growth and, in extreme cases, may lead to the phenomenon known as the “death spiral” [14]. Due to the ecological transformation of formerly rural and suburban habitats into urban ones, accompanied by a decline in habitat quality, it is often difficult, or even impossible, to maintain mature trees in good condition.

It is also important to note that the stressors affecting trees in urban environments (light, humidity, temperature, wind, water, and nutrition) are increasingly similar to those affecting city inhabitants themselves as urbanization progresses [15,16,17].

In Poland, the tradition of planting trees along roads in the open landscape dates back to the 16th century. Initially, these were primarily private roads connecting landed estates—manor houses with farmyards, farmyards with mills, and so forth. Over time, avenues that once carried only light traffic were transformed into municipal and national roads. With the growth of motorization, the development of modern road infrastructure has placed aging roadside trees under significant pressure. Due to their age and size, their ability to adapt to changing environmental conditions is limited [18,19,20,21,22].

Large and old “veteran” trees provide the greatest ecosystem benefits, often equaling the environmental impact of dozens of newly planted saplings [23]. They play a key role in biocenosis and phytoremediation, acting as natural barriers that reduce the spread of particulate matter (PM) and absorb gaseous pollutants such as NOx, CO, SO2, and O3 [24]. Aging trees also support rich microbiological habitats [25].

Deciduous trees significantly influence the urban microclimate by reducing UV, visible, and infrared radiation, improving thermal comfort and mitigating heat stress [6,26,27,28]. Shaded areas encourage longer outdoor activity and more frequent walking.

Green elements along pedestrian routes enhance the aesthetic quality of streets, promote positive landscape perception, increase the sense of safety, and have a calming effect on both pedestrians and drivers [29,30,31,32]. Vegetation also influences noise perception by providing acoustic masking and reducing stress. These effects align with restoration theories emphasizing the role of nature in cognitive recovery and stress reduction [33,34,35].

The management of historic trees involves conservation, maintenance, and protection. Modern arboriculture is increasingly grounded in research highlighting the stimulation of trees’ natural defense mechanisms and the improvement of habitat conditions to enhance longevity and vitality [36]. With the acceleration of urbanization and growing environmental degradation, proactive measures for the protection and care of old trees have become indispensable. Contemporary strategies for managing ancient and veteran trees are increasingly framed within the concept of nature-based solutions, underscoring that the preservation and maintenance of monumental specimens represent not only nature conservation, but also an investment in quality of life and urban resilience [37,38,39]. This represents an innovative and interdisciplinary approach, integrating ecological, social, spatial, and cultural dimensions into a modern model for managing heritage green infrastructure.

Therefore, this study aims to address existing knowledge gaps by conducting a comprehensive health assessment of this historic linden avenue through the integration of sonic tomography, chlorophyll fluorescence analysis, and quantification of surface sealing. The ultimate goal is to develop an evidence-based monitoring and management framework applicable to historic green infrastructure in urban environments.

Avenues in the Historical Landscape of Poland—Origins and Development

The noble manor constituted an inseparable part of Poland’s historical landscape. In addition to the convenient and often picturesque setting of the manor house itself and its farmstead buildings, considerable attention was devoted to the arrangement of its surroundings. A long, representative tree-lined avenue usually marked the entrance to the residence.

Avenues have for centuries been an important component of the rural landscape, fulfilling both practical and compositional functions. They were created not only to facilitate communication but also to emphasize visual axes and the spatial layouts of estates. Avenues often linked manor houses with key elements of the surroundings, such as the village, the church, or the mill [40]. Initially, native species such as linden, maple, rowan, and poplar were planted, followed later by poplar hybrids and horse chestnuts. At the beginning of the 20th century, trends favored fruit trees, green ash, and black locust [41]. As noted by Szwarc–Bronikowski [42], avenues are relics of the rural landscape, “…remnants of the native countryside, which today no one knows how to plant or properly maintain. The most beautiful of them, once carefully laid out by our ancestors, are now decimated, often leading… nowhere. (…) Linking manor houses, villages, towns, and cities, they traced the main routes along which tidings of joy or fear once traveled. Along them, too, Polish history often galloped.”

Across Europe, in various historical periods—particularly during the Baroque era—avenue trees were highly valued, especially linden species. For example, Tilia × europaea and Tilia platyphyllos were commonly planted in avenues in England, France, and Germany [43,44]. In Poland, the small-leaved linden (Tilia cordata), a native species, was frequently used as an avenue tree in the Lublin region.

Roads that once primarily served horse-drawn carriages and experienced only light traffic have gradually transformed into heavily used transport routes. The old avenue trees growing along these roads, both within urbanized areas and in rural settings, are now exposed to numerous adverse impacts. Among the most serious threats are soil compaction and the use of impermeable surfaces within the zone of their root systems. Compacted soil represents one of the greatest dangers to roadside trees, as it restricts the availability of air, water, and nutrients to the roots, leading to a decline in physiological condition and, consequently, to the gradual dieback of trees [45].

2. Materials and Diagnostic Methods

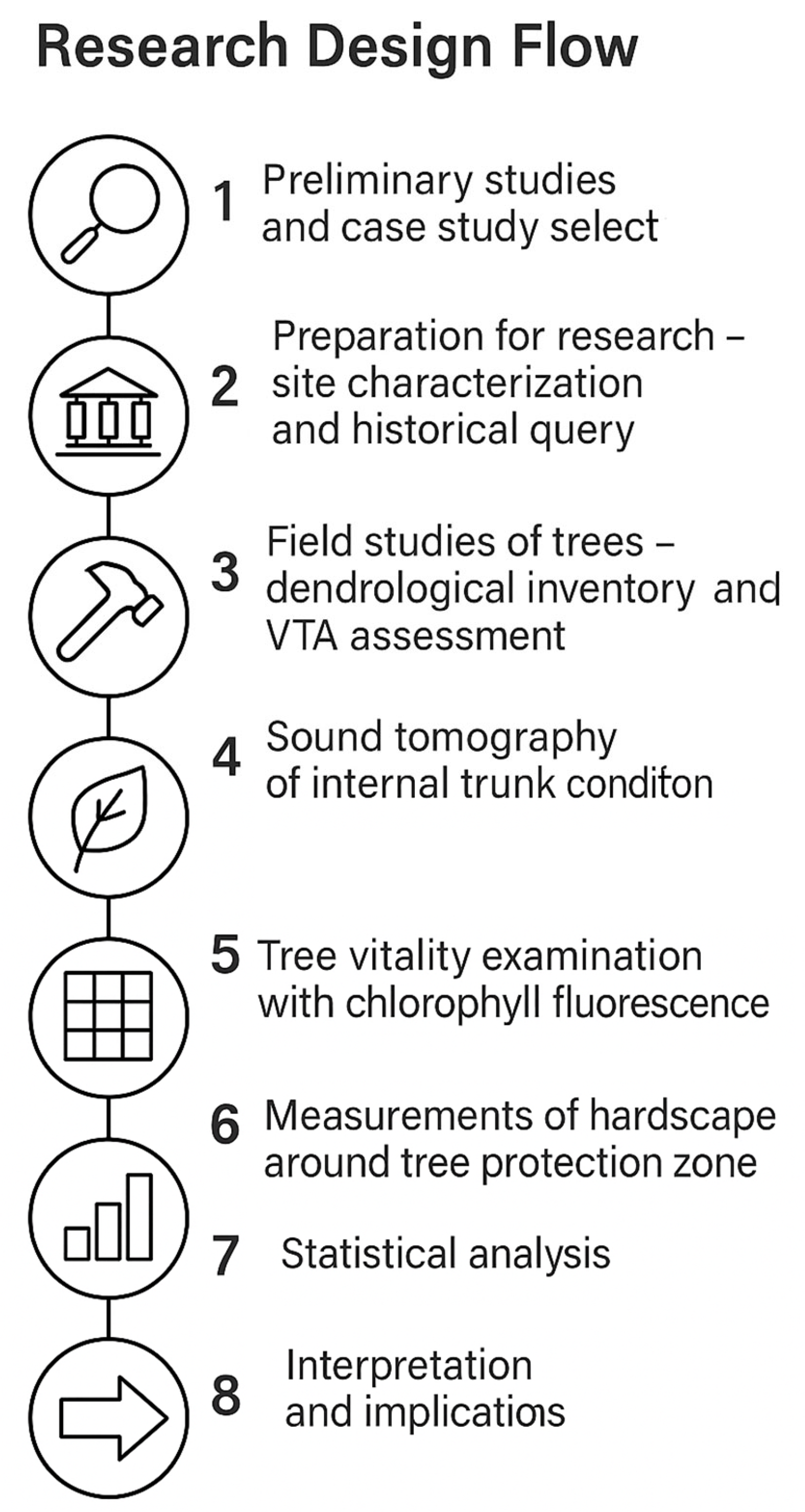

To ensure a systematic approach, the research design was structured into a sequence of eight methodological steps (Figure 1). The process begins with a detailed characterization of the case study area, establishing the spatial and environmental context of the avenue. This is followed by an in-depth analysis of spatial transformations in its immediate surroundings. In the subsequent stages, specialised diagnostic tools—including a tomograph and a fluorimeter—were employed to obtain precise biophysical measurements. Surface sealing beneath the tree canopies was then assessed to evaluate the degree of ground imperviousness and its potential impact on tree vitality. The collected data underwent statistical analysis to strengthen the reliability, objectivity, and robustness of the results. Finally, the findings were interpreted to uncover their broader dendrological and socio-cultural implications, providing a foundation for evidence-based urban landscape management and conservation strategies.

Figure 1.

Research design and methodological framework illustrating the sequential research process (authors’ own elaboration).

2.1. Material

Field studies in situ were also carried out. These included on-site surveys, dendrological inventory, and photographic documentation. A total of 34 specimens of small-leaved linden (Tilia cordata Mill.) were inventoried, growing in a single row over a length of ca. 300 m. The geographical coordinates of the study area are as follows: 51°14′16.075″ N and 22°30′4.044″ E.

The study area is located in Lublin, which lies within a humid continental climate zone, characterized by the absence of a distinct dry season, warm summers, and cold, snowy winters. Mean monthly temperatures range from approximately −4 °C in January to 24–25 °C in July–August, with precipitation distributed fairly evenly throughout the year, peaking in late spring and summer [46]. The dominant soil types are brown and luvisolic soils (WRB: Cambisols, Luvisols), developed on loess deposits and of high agricultural quality. In river valleys, particularly along the Bystrzyca River and its tributaries, alluvial and organic soils prevail, while rendzinas occur on carbonate bedrock, and podzolic soils are present on sandy substrates [47]. The potential natural vegetation is mainly subcontinental hornbeam–oak–linden forests (Tilio-Carpinetum), with patches of thermophilus oak woods (Potentillo albae–Quercetum), and riparian alder and willow–alder communities (Circaeo-Alnetum, Ribo nigri–Alnetum) along watercourses [48].

2.2. Study Area Characteristics–The Linden Avenue in Konstantynów, Lublin

Lublin constitutes the largest urban center in eastern Poland and serves as a key administrative, academic, cultural, and economic hub of the region. With a population of approximately 330,000, the city plays a pivotal role in higher education and research, owing to the presence of several universities, most notably the Catholic University of Lublin and Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. Lublin is distinguished by its long historical continuity, reaching back to the Middle Ages, and by the preservation of its historic Old Town. Within the city’s contemporary structure, Konstantynów represents a district located in the western sector of Lublin.

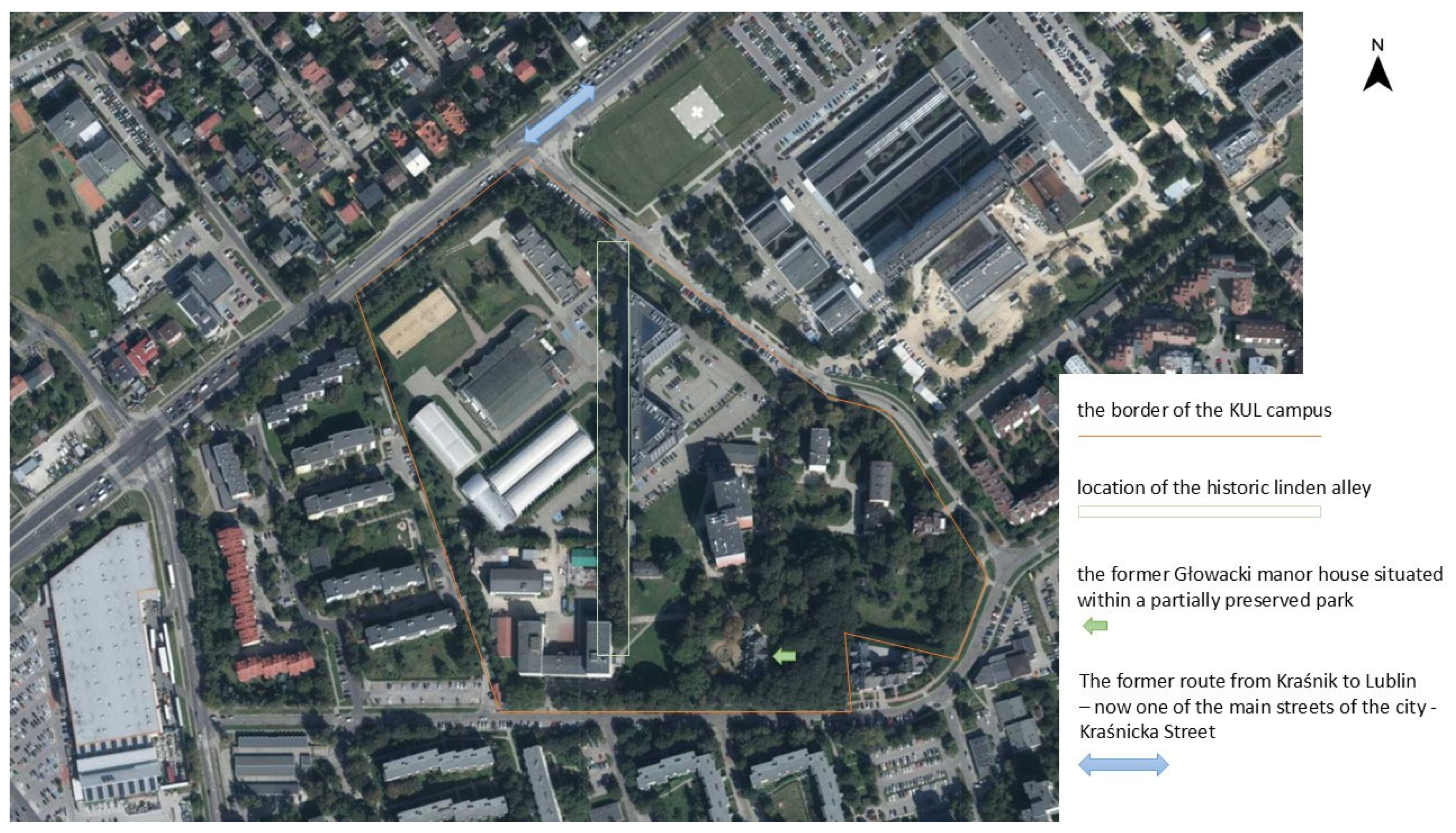

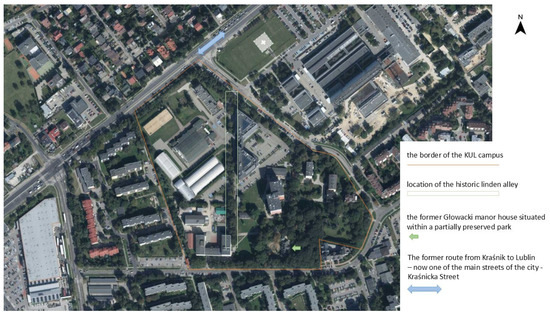

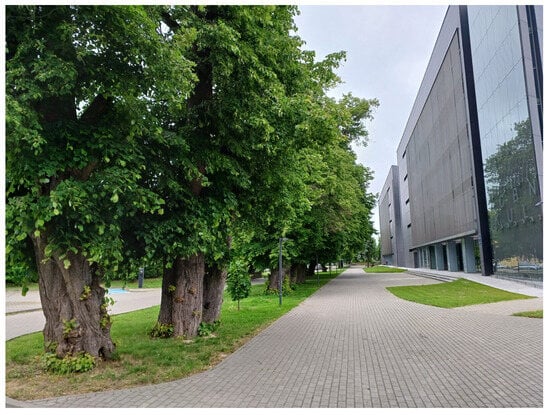

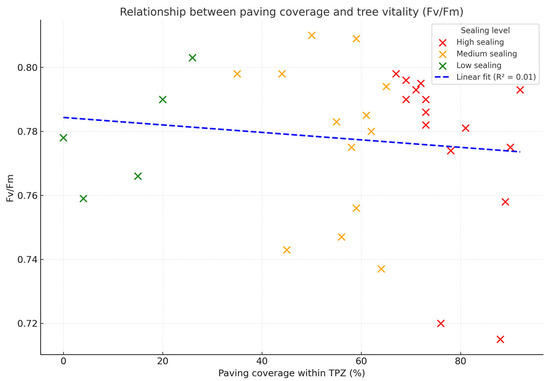

The analyzed linden avenue is located on the campus of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin along Konstantynów Street in Lublin (Figure 2). The remnant linden avenue, preserved as a single row of trees, runs only on one side of the communication route leading from the entrance to the campus toward the former Gałecki manor house (Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7). The manor is situated within the remains of a small fragment of the historic park.

Figure 2.

Linden avenue against the background of the KUL campus (https://mapy.geoportal.gov.pl/imap/Imgp_2.html, accessed on 5 May 2025) [49].

Figure 3.

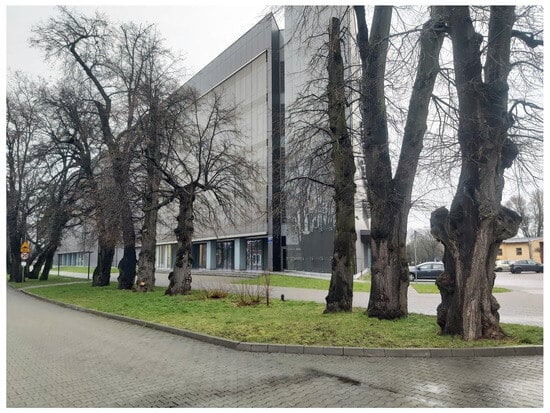

Linden avenue at the Interdisciplinary Research Centre of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin (KUL), accessed on 5 May 2025 (photo M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

Figure 4.

The linden avenue leading towards the building of the Faculty of Natural and Technical Sciences, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, accessed on 5 May 2025 (photo M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

Figure 5.

The linden avenue at the Interdisciplinary Research Centre, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, accessed on 5 February 2024 (photo M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

Figure 6.

The linden avenue leading towards the building of the Faculty of Natural and Technical Sciences, John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, accessed on 5 February 2024 (photo M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

Figure 7.

The beginning of the linden avenue at the entrance to the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin campus, accessed on 5 February 2024 (photo M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

The origins of Konstantynów can be traced to the establishment of a manor farm (folwark) in 1857 on land formerly belonging to the Jesuit estate of Rury. The founder of the estate was Ignacy Bukowski, who had acquired the post-Jesuit property. The manor farm was situated near the road leading to Kraśnik and Bełżyce, with convenient access to the Warsaw highway and the route to Nałęczów. By 1865, Konstantynów had developed a complete set of farmstead buildings. Initially integrated within the Rury estate and leased for extended periods, the property was formally separated only in 1880, when it was purchased by Władysław Gałecki.

Cartographic evidence from 1880 indicates that the core of the settlement was concentrated near the western boundary of the estate, in a location corresponding to the present-day complex of buildings belonging to the Catholic University of Lublin. Archival inventories from 1868 and 1885 describe the development as comprising a single-story wooden manor house accompanied by a range of wooden utility buildings, including a granary-storehouse, barns, cowsheds, and a multifunctional structure housing a stable, oxen shed, and carriage house. These service buildings, arranged in a semicircular formation in front of the manor, created an enclosed courtyard composition [50,51].

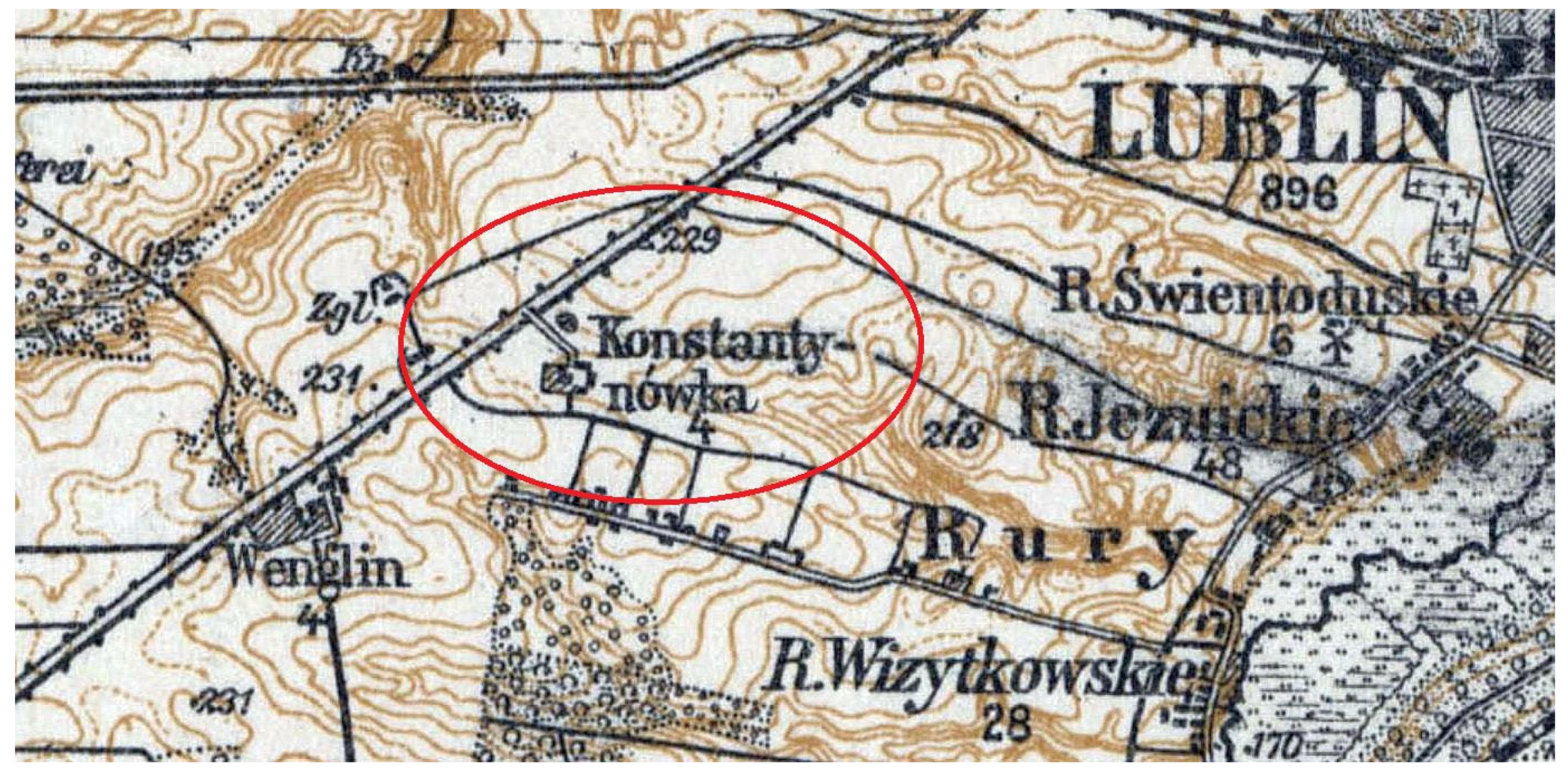

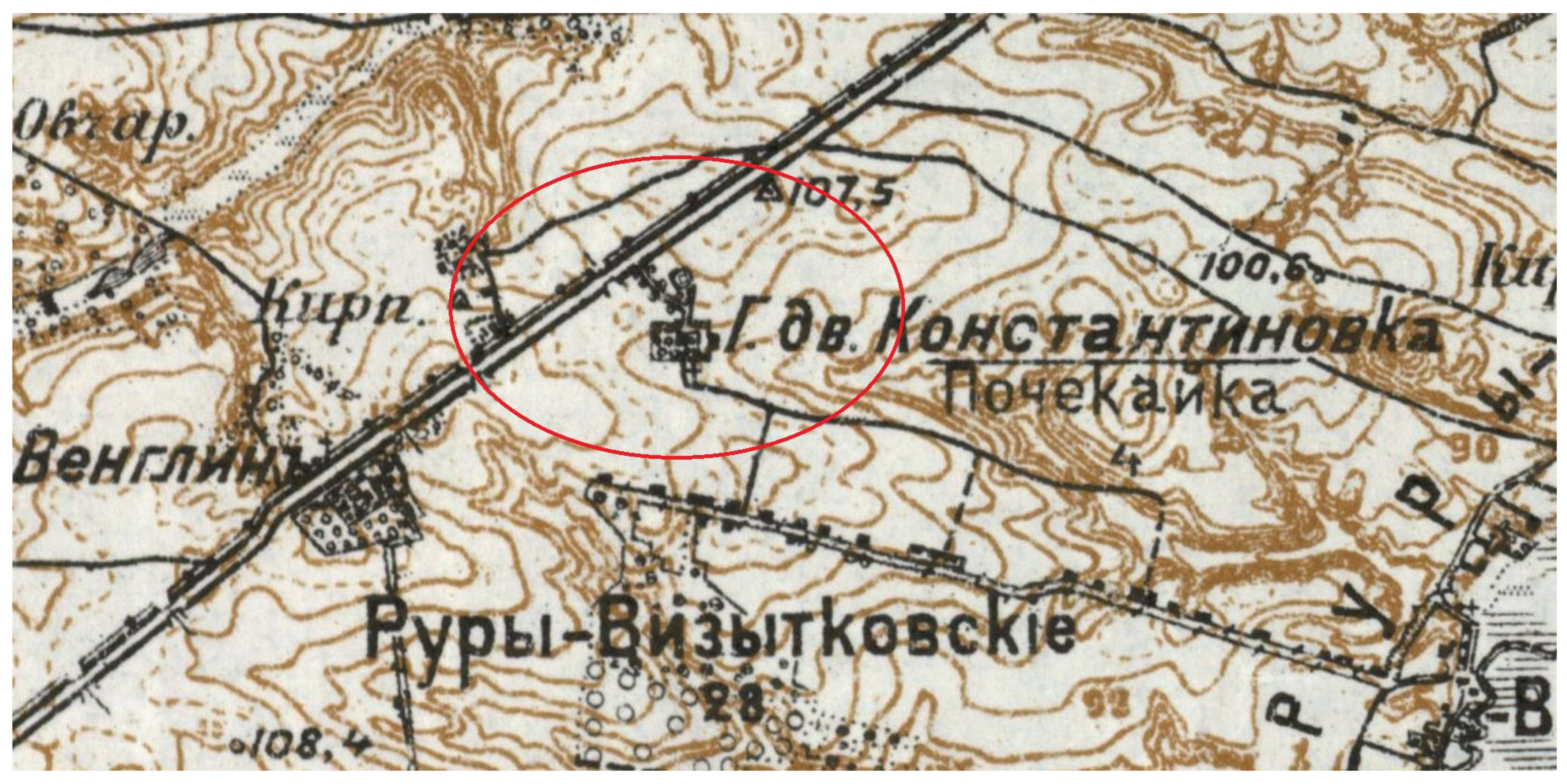

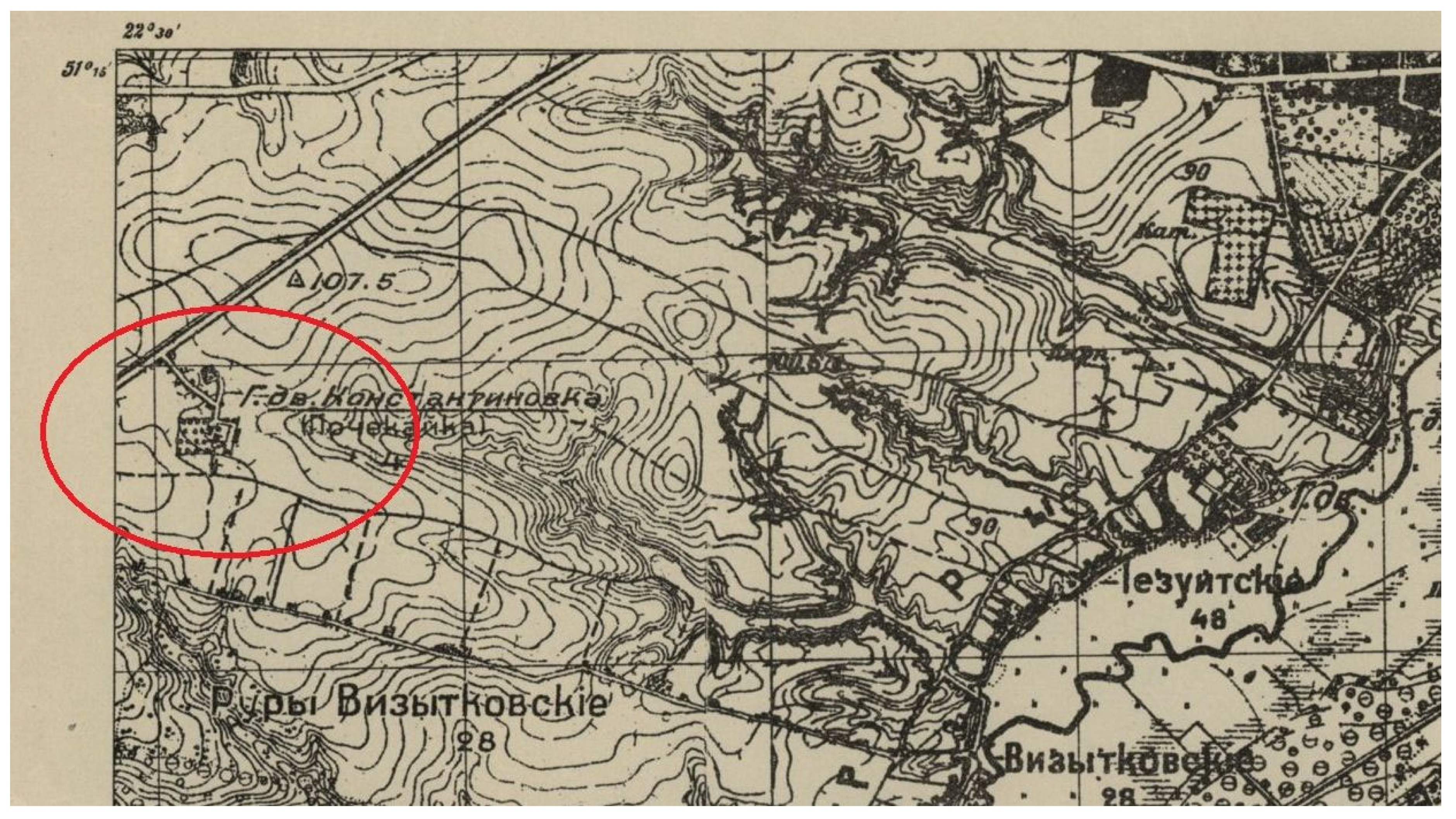

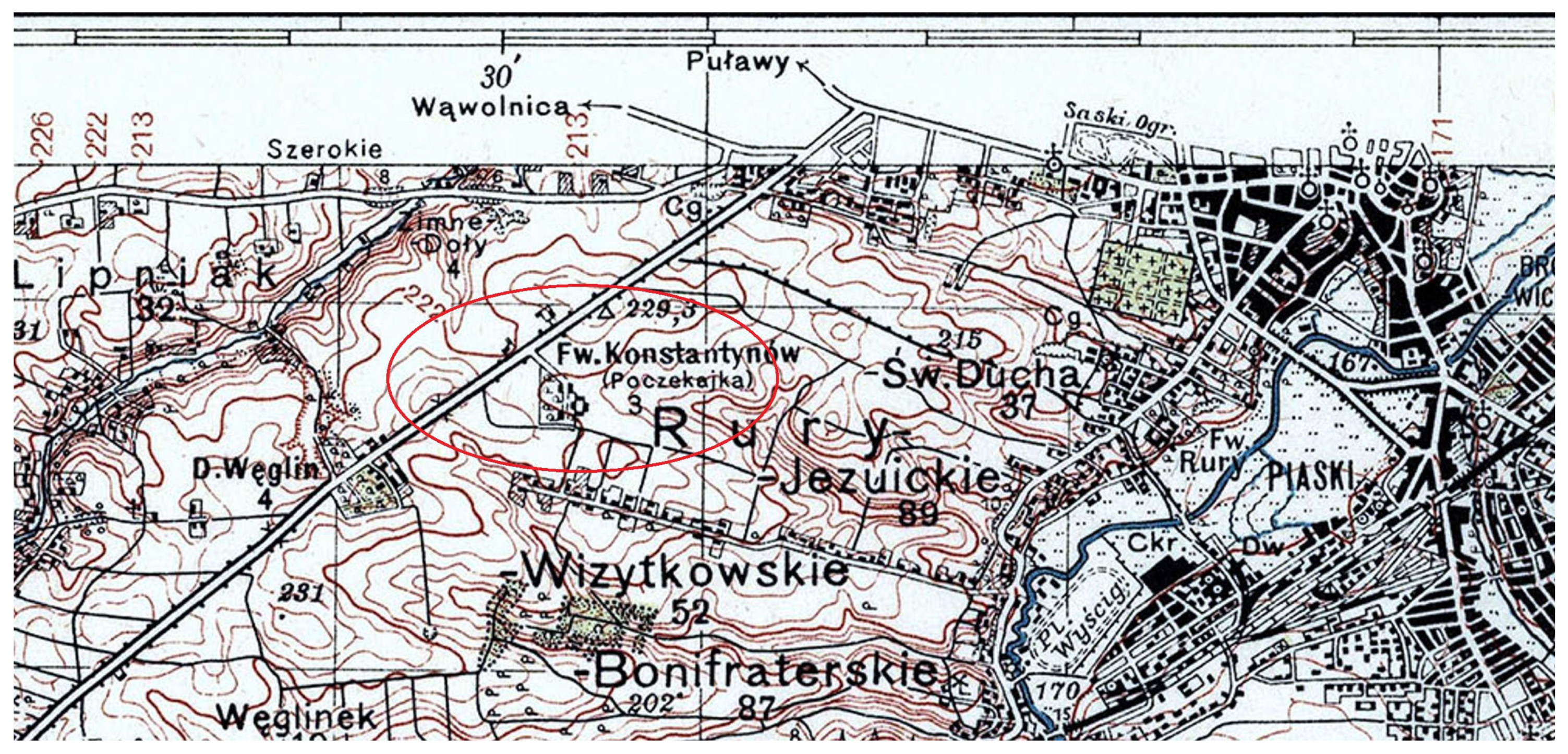

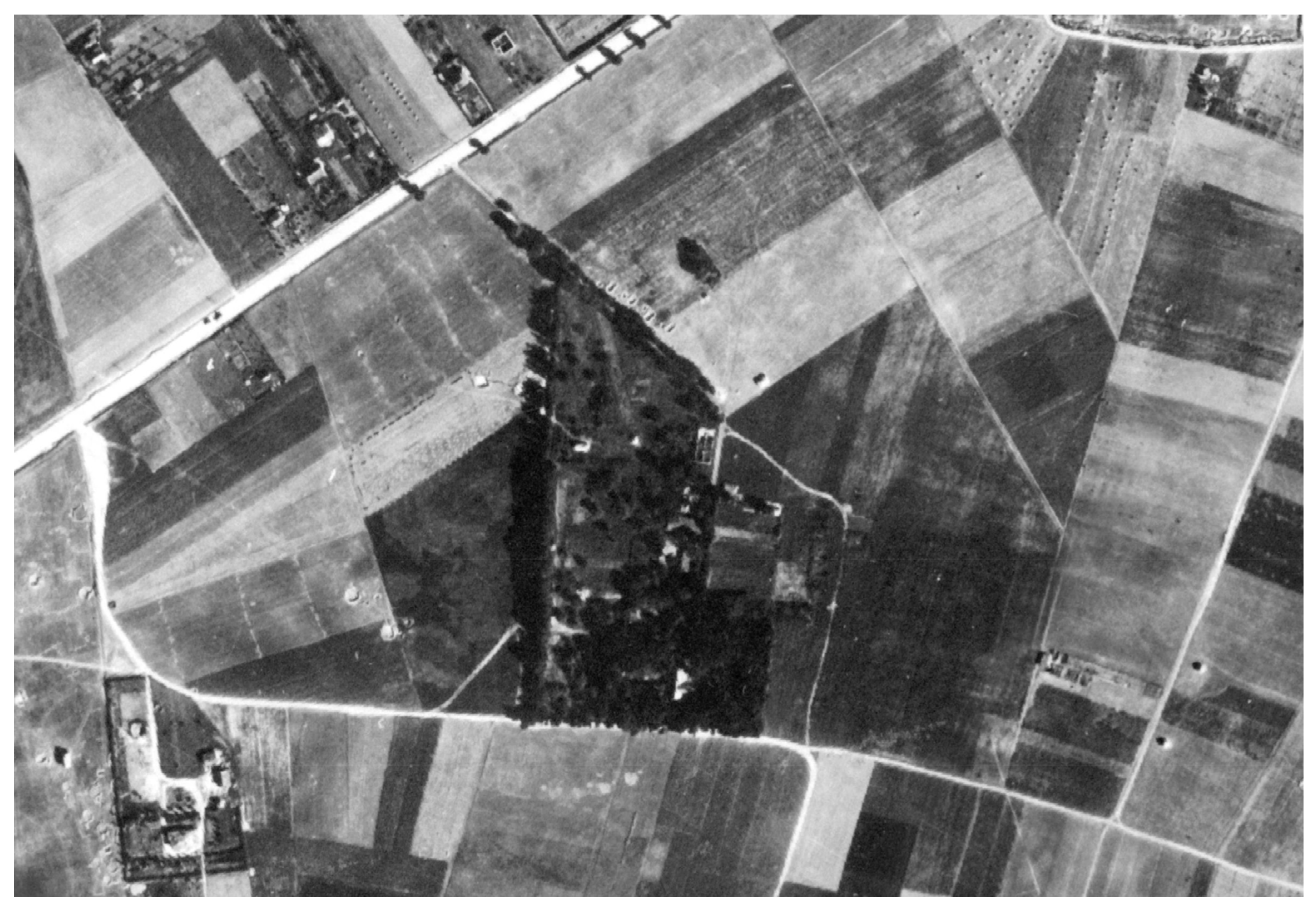

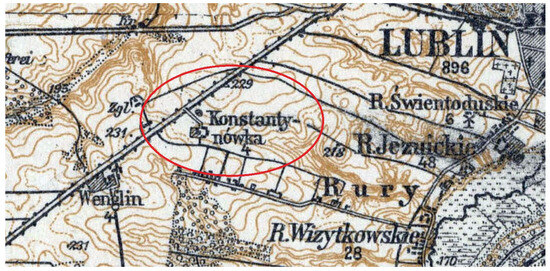

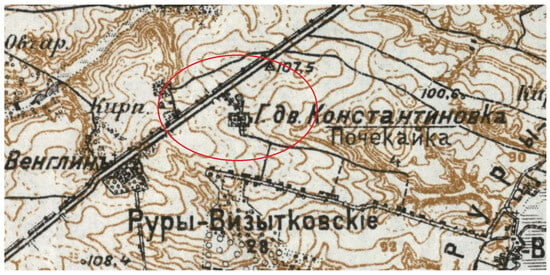

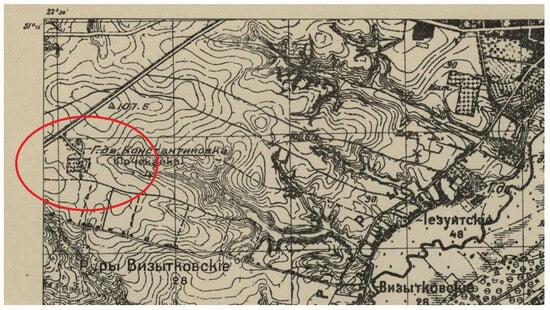

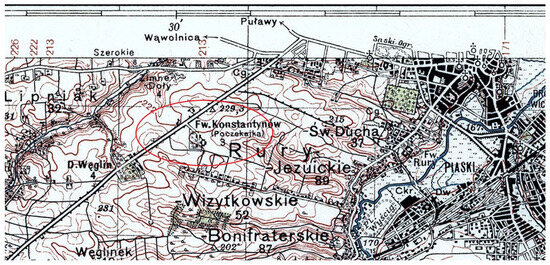

Maps from 1914 (Figure 8 and Figure 9) depict the manor farm known as Konstantynówka, situated along the Kraśnik–Lublin route. The spatial arrangement of buildings organized around the central courtyard is clearly visible, together with a small adjoining landscaped park. Figure 10 further documents the presence of avenue plantings leading toward the manor complex. By 1937, the property had been expanded with several additional structures (Figure 11), while by 1955, the estate had become embedded within the growing residential fabric of the Konstantynów district (Figure 12).

Figure 8.

Location of the Konstantynów manor farm along the Lublin–Kraśnik route, 1914 [52].

Figure 9.

The Konstantynów manor farm on the outskirts of the city of Lublin, 1914 [53].

Figure 10.

Location of the Konstantynów manor farm along the Kraśnik–Lublin route, 1931 [54].

Figure 11.

The Konstantynów manor farm on the outskirts of the city of Lublin, 1937 [55].

Figure 12.

The Konstantynów manor farm within the boundaries of the city of Lublin, 1955 [56].

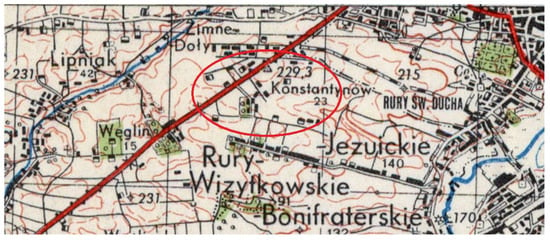

The original wooden farm buildings of Konstantynów have not survived to the present day, having gradually deteriorated over time and been replaced with masonry structures. The only surviving element is a single-story wooden manor house, now situated at the rear of modern development at 1D Konstantynów Street. In 1865, the building was described as a residential house “constructed on a foundation with joints and posts, with log walls,” and covered with wooden shingles. Following later alterations—replacement of the roof covering and plastering of the walls—it unfortunately lost its stylistic purity. Nonetheless, the decorative porch with carved columns, already recorded in the 1865 description, has been preserved.

Dating back to the 1860s, the manor represents a now-rare architectural type, and for this reason merits attention and continued protection. Historically, it is also associated with the writer Andrzej Strug, who resided here in his youth, during the period when Konstantynów belonged to his family [47] (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

The Gałecki manor house—view of the western façade and the circular lawn at the driveway, accesed on 20 July 2025 (photo by M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

Figure 14.

The Gałecki manor house—view of the eastern façade, accesed on 20 July 2025 (photo by M. Dudkiewicz-Pietrzyk).

In 1948, the remaining part of the Konstantynów manor estate was purchased by Rev. Antoni Słomkowski, Rector of the Catholic University of Lublin. At that time, the present-day campus covered an area of approximately 10 hectares and included farm buildings, a park, a vegetable and fruit garden, and the mid-19th-century Gałecki manor house, which accommodated around 50 female students. The administration of the estate was entrusted to the Ursuline Sisters. In the following years, two new dormitories were constructed on the site. This proved a significant step in light of the considerable increase in student enrollment at the Catholic University of Lublin during the 1950s. In 1964, a small house in the garden (the so-called gardener’s house) was completed, providing accommodation for approximately 20 nuns from various congregations studying at the University. In the 1980s, a ten-story dormitory named Konstantyna was erected, offering places for about 800 residents [57].

An aerial photograph from 1939 illustrates the spatial arrangement typical of a rural estate (Figure 15). The manor house is situated within a densely wooded park, accessed by a tree-lined avenue extending from the Lublin–Kraśnik road. The avenue branched into two routes: one of them—depicted in this manuscript—formerly encircled the estate from the west. This was most likely the representational approach, extending nearly to the far end of the park before turning eastward toward the courtyard in front of the manor house. The second branch also led to the manor but passed through the farm buildings, suggesting a more functional and utilitarian purpose. At that time, the estate was surrounded by fields and meadows.

Figure 15.

The Konstantynów manor farm in 1939 [49].

A photograph from 1983 documents the period of campus and dormitory construction (Figure 16). By then, employee allotment gardens had occupied a significant portion of the former manor estate. The avenue remained largely unchanged, while the surroundings of the estate underwent considerable transformation. On the north-eastern side, in the location of a former field pond, the Provincial Hospital was established.

Figure 16.

The Konstantynów manor farm in 1983 [49].

An aerial photograph from the late 1990s illustrates the major transformations that had occurred within the former suburban estate (Figure 17). The park had been substantially reduced in size to make way for new buildings. The linden tree avenue still retained its unpaved surface. At that time, the avenue plantings were relatively dense, and the trees displayed broad crowns. No significant gaps or losses in the avenue structure are visible. In comparison with the present condition, however, the avenue has since become thinned out, and the crowns of the trees have been heavily pruned.

Figure 17.

The Konstantynów manor farm in 1998 [49].

A comparison of the spatial layout of Konstantynów in 1939 with its present form in 2025 reveals significant transformations of the cultural landscape resulting from intensive urbanization and the expansion of the Catholic University of Lublin campus (Table 1). The former manor farm, once characterized by a clearly defined composition of the Gałecki Manor, a representative access avenue, farm buildings, and an adjoining park, has been largely converted into an urban structure with an entirely different functional character. The preserved wooden manor, now hidden among contemporary development, remains a relic of the original spatial arrangement, while the former access avenue functions today as an internal campus road. The farmstead layout has undergone a complete transformation, with the original agricultural buildings replaced by academic and educational facilities. Only fragments of the historic park have survived, while the surrounding fields and meadows have been replaced by dense residential development in the Konstantynów district (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparative schematic of the spatial structure of Konstantynów/KUL—1939 and 2025 (Authors’ own elaboration).

Table 2.

Changes in the surroundings of the historic linden avenue in Konstantynów (1939–1983–2025) (Authors’ own elaboration).

The following study was conducted in Lublin in the years 2024–2025. An assessment of the health status of a historic linden tree avenue was performed using classical research methods applied in landscape architecture and arboriculture. Each component of the research relied on different methodologies and sources of data.

For the historical analysis of the site, archival query techniques were employed. A detailed search was carried out in the municipal archives to identify situational and construction plans. Scientific databases and digital resources were also used: BazHum, CEJSH, JSTOR, SpringerLink (articles in the fields of architecture, art history, and conservation); Polona (iconographic sources and historical maps); and Geoportal.gov.pl (contemporary spatial data compared with historical datasets). Based on archival maps, changes in the urban structure surrounding the avenue were analyzed over time. This interdisciplinary and integrated research approach bridges historical, spatial and environmental aspects.

The dendrological inventory comprised a general description of each tree, including basic dendrometric features: tree height, crown base, trunk circumference, trunk diameter, and crown diameter. The general condition of the root system, trunk, and crown was also assessed. Five aspects of each tree were evaluated: A—root system and planting site conditions; B—trunk condition; C—crown condition, including crown base and overall structure; D—tree vitality; E—degree of maintenance and care. Visual examination of the area within the root system (A) was crucial for assessing root health without excavation. The form and changes in the root collar, as well as visible injuries, were taken into account. Trunk condition (B) is essential for overall tree health: decay compromises wood stability and restricts nutrient and water transport. In addition, the crown base and root collar were considered, as they are highly vulnerable parts of the tree. Crown structure (C) was evaluated, while vitality (D) was assessed based on infections, overall tree health, and the state of roots and trunk. The level of maintenance (E) provided recommendations for future conservation.

To assess tree vitality, the method developed by Roloff, 2016 [11] was applied. This four-stage scale (0–3) identifies phases of tree vitality: from the exploration phase (phase 0) to the resignation phase—dieback (phase 3) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Tree vitality scale [11].

2.3. Instrumental Research Methods

To comprehensively assess the health condition of the historic linden tree avenue, a combination of classical dendrological methods and advanced diagnostic techniques was applied. The research included dendrometric measurements as well as specialized analyses of trunk integrity and physiological condition. In order to comprehensively assess the health condition of the historic lime tree avenue, a combination of classical dendrological methods and advanced diagnostic techniques was applied. The research included dendrometric measurements as well as specialized analyses of trunk integrity and physiological condition.

This integrated and interdisciplinary approach allowed not only for the evaluation of external growth parameters but also for the early detection of internal changes invisible through traditional visual assessments. The use of advanced diagnostic methods represents an innovative aspect of the study, enhancing the precision and predictive value of the results and supporting more effective conservation and adaptive management of historic tree avenues.

Basic field measurements were conducted using measuring tapes and laser rangefinders. The Leica DISTO 5 (Leica Geosystems AG, Heerbrugg, Switzerland) was used to determine crown spread and distances, while the Nikon Forestry PRO (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) allowed precise measurement of tree heights.

The assessment of trunk integrity and the detection of internal defects were performed by means of acoustic tomography. For this purpose, a Picus Sonic Tomograph 3 (IML Instrumenta Mechanik Labor Electronic, Rostock, Germany) was employed. This non-destructive technique records the propagation of sound waves in wood, enabling the identification of decayed areas, cavities, and changes in wood density.

In parallel, the physiological condition of the trees was evaluated using chlorophyll fluorescence analysis. Measurements were carried out with an OS5p+ fluorometer (OPTI SCIENCES Inc., Hudson, NY, USA). This method provides insight into photosynthetic efficiency and plant stress levels caused by environmental factors.

Additionally, the share of impermeable surfaces within the crown projection zone was analyzed. This factor is crucial for understanding site conditions, as it directly influences root development and water management.

The application of multi-aspect methods allowed for a comprehensive evaluation of the studied specimens and identification of major threats to their long-term vitality.

The sonic tomograph used in the study enables a non-invasive assessment of the internal structure of tree trunks, focusing on the occurrence of decay, cavities, and hollows. This technology is based on the analysis of sound wave propagation in wood, eliminating the need for invasive drilling that could damage tree tissues [58,59].

The sonic tomography system consists of a central processing unit, sensors placed around the tree trunk (connected via shallowly driven nails), and dedicated software. The sensors record the travel time of a sound wave induced by an electronic hammer strike. Typical sound propagation velocities in living linden (Tilia cordata Mill.) wood range from 940 to 1183 m·s−1 [60].

The height of sensor installation depends on the presumed location of internal damage, which can be preliminarily identified using the mallet sounding method. A dull resonance suggests possible internal defects such as cavities, chimney-shaped hollows with thin walls, or fungal decay. In such cases, tomographic measurements are performed directly in these areas. For a more comprehensive picture, tomography may also be conducted at multiple trunk levels, allowing determination of the direction of infection spread and the extent of internal damage.

The distances between sensors are measured using a PiCUS caliper (IML Instrumenta Mechanik Labor Electronic, Rostock, Germany), a specialized caliper connected to the measurement system via Bluetooth, enabling precise mapping of the trunk shape. Based on the collected and processed data, the software generates a color tomogram, visualizing internal structural changes in the tree trunk.

When analyzing the tomographic image, special attention is paid to the color map of wood density, which reflects differences in sound wave velocity depending on tissue elasticity and density. Colors ranging from light brown to black correspond to velocities of 60–100%, indicating healthy and intact wood structure. Various shades of green represent velocities in the range of 40–60%, interpreted as a slight deterioration in wood quality. Pink coloration corresponds to velocities of 20–40%, while colors from blue to white (0–20%) identify zones of severe damage or advanced wood decay [61,62].

The trunk circumference was measured conventionally at breast height (1.30 m above ground level) using a measuring tape with an accuracy of 1 cm, while the diameter was measured with a mechanical caliper in two directions (N–S and E–W) at a height of 100 cm. For crown projection, the diameter was measured from four cardinal directions, and the mean value was calculated to represent crown spread.

The Tree SA method is based on the static triangle, which incorporates three elements: material, shape, and load. This approach is a tomographic equivalent of the Static Integrated Assessment (SIA) method, developed and described by Wessolly and Erb (2016) [63,64]. The Tree SA calculations are integrated with the Picus Q74EXP software (IML Instrumenta Mechanik Labor Electronic, Rostock, Germany) operating the tomograph. In this method, a safety factor of 1.5–2.0 is adopted, which corresponds to values of 150–200 in the SIA method. This represents a factor 50–100% higher than the basic safety coefficient (equal to 1, or 100 in the SIA method), ensuring sufficient resistance to the strongest winds typical of the studied geographical region.

For this safety factor, the required percentage of residual strength of the solid wood is calculated and compared with the percentage of mechanically intact wood obtained from the tomographic analysis. Based on all measurements, the minimal wall thickness of the tree trunk can be determined and mapped on the tomogram. The geometric moment of inertia is then calculated, serving as the basis for defining the bending strength index of the trunk cross-section. In addition to precise height measurements, the nominal diameter of the trunk at 100 cm is also measured, allowing a more accurate reconstruction of the morphological longitudinal section characteristic of the tree species under study.

A complement to structural studies is chlorophyll fluorescence, a non-invasive technique that allows for the assessment of the physiological condition of plants. A fluorometer is a device that enables rapid and non-invasive measurement of the photosynthesis process. Chlorophyll fluorescence measurement is particularly useful for assessing plant health and for monitoring their response to various environmental stress factors [65,66,67,68]. The procedure involves placing a special clip with a closed window on the leaf blade for approximately 20–30 min (the dark-adaptation time required for measurement). Afterwards, the probe sensor is inserted into the clip, the window is opened, and the measurement is taken. The display shows the results, indicating the levels of specific parameters. One of these parameters (Fv/Fm) is widely recognized as a reliable diagnostic indicator, particularly for evaluating the effects of stress conditions on plants [69,70,71]. Under full growth and in the absence of stress factors, this value typically ranges, depending on the species, from about 0.79–0.83 [72,73] up to 0.85 relative units [74]. The impact of biotic and abiotic stress factors reduces the quantum efficiency of photosystem II (PSII) and lowers its value. Very low values of this parameter—at the level of 0.20–0.30—indicate irreversible damage to the PSII structure [75]. On the leaves of each tree, seven clips with observation windows were installed, and measurements were subsequently taken. Based on the obtained results, the mean value of the Fv/Fm index was calculated.

To provide a broader context for interpreting the physiological measurements, the study further incorporated an assessment of site conditions affecting tree vitality. This analysis was expanded to include a detailed evaluation of the degree of surface sealing beneath the tree canopies. Therefore, the area of the Tree Protection Zone (TPZ—defined as the canopy projection plus 1 m) was determined. During the site inspection, the layout of transportation infrastructure (pedestrian and vehicular routes, parking areas) located within the canopy projection zones, with an additional 1 m buffer, was mapped. The “canopy projection + 1 m” rule is widely applied in municipal standards in Poland (Wrocław, Kraków, Płock) and confirmed in Warsaw’s official guidelines as a practical approximation of the root system’s extent [76,77,78,79,80]. Subsequently, using AutoCAD 2025 software, the percentage share of paved surfaces in relation to the TPZ area was calculated.

3. Results

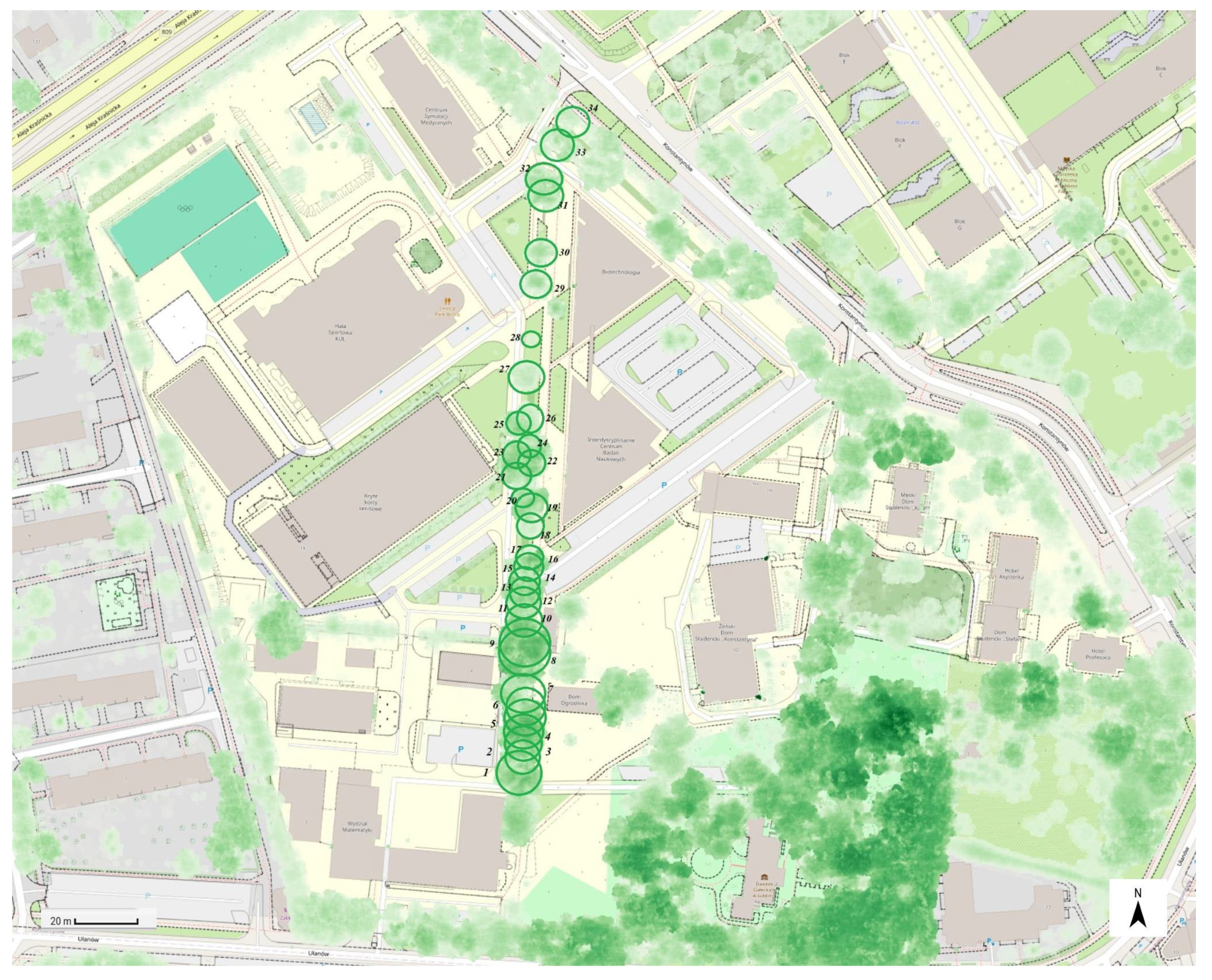

3.1. Detailed Dendrological Inventory

During the field survey, 34 specimens of Tilia cordata Mill. (small-leaved linden) were inventoried, forming a single-row avenue approximately 300 m in length (Figure 18, Table A1). The avenue begins at the main entrance to the Catholic University of Lublin campus. Near the first linden trees, growing on a slope, there is a roadside shrine with a statue of the Virgin Mary. The next trees are planted in elevated concrete basins, situated in front of the façade of the newly constructed KUL Research Center.

Figure 18.

Inventory map of the linden avenue—KUL campus (prepared by the authors).

Along the subsequent specimens, a pedestrian walkway has been routed in very close proximity to the trunks. Here, the trees occupy small rectangular plots covered with lawn grass. The entire surface of the avenue has been paved with concrete blocks, and beneath the trees adjacent to the Faculty of Natural and Technical Sciences, a parking bay has been introduced. The avenue, subject to heavy pedestrian and vehicular traffic, constitutes the main axis of circulation between the university buildings.

The trees were most likely planted during the establishment of the manor farm in the 1860s–1880s. Over the years, a number of specimens have been removed, as evidenced by vacant spaces subsequently filled with new plantings.

The most distinctive trees are those located at both ends of the avenue, characterized by trunk circumferences exceeding 300 cm.

3.2. Tomographic Examination

Based on visual inspection and percussion of tree trunks with a diagnostic hammer at different heights, specimens were identified in which destructive processes inside the trunk were suspected, or in which structural defects, invisible externally, might be present. Ultimately, 16 trees were selected for tomographic examination. The results, processed with specialized software, determined the percentage of internal trunk damage across the cross-section and assessed the trunk’s mechanical strength against fracture. Each assessment produced a color tomogram accompanied by a detailed description. Four cases showing the most severe internal degradation are presented below. The complete set of tomographic results is included in Appendix B, Table A2.

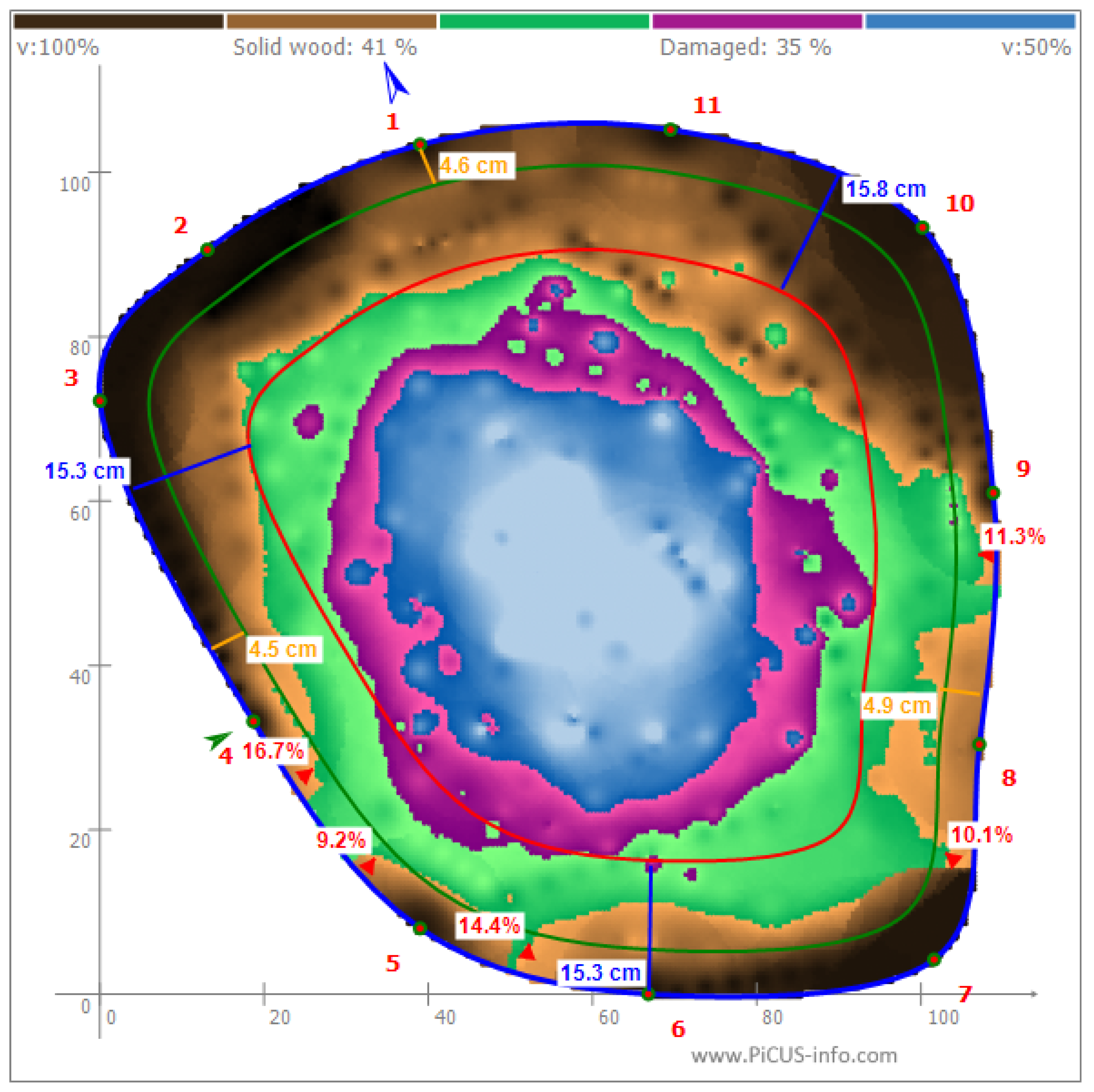

For the trunk of Tilia cordata (inventory no. 6), 11 measuring points were positioned at a height of 1.7 m by inserting small nails into the bark. Sensors attached to these nails recorded the velocity of sound waves across the trunk cross-section, generated by impacts of an electronic hammer. The analysis revealed substantial damage to the internal wood structure. The decayed zone (damaged wood) accounted for 67% of the trunk cross-section (depicted in colors from pink to blue), while sound, mechanically functional wood represented only 15% (brown color). The remaining 18% consisted of transitional wood, which was not yet damaged but susceptible to decay processes. It had a tendency to transform into defective wood over time, thereby enlarging the decayed zone.

The mechanical resistance of the trunk to fracture was found to be severely reduced due to the disproportionately low percentage of healthy wood. There is also a considerable risk of radial internal cracking (indicated by yellow lines) propagating in all directions. The measured velocity of acoustic wave propagation inside the trunk ranged from 314 m·s−1 to 1006 m·s−1, depending on the degree of degradation. These lower values significantly deviate from the typical sound velocities in healthy linden wood, which usually range between 940 and 1183 m·s−1 [43].

On the tomogram, the red line marks the critical wall thickness required to ensure minimal mechanical stability of the trunk. In this specimen, the calculated average wall thickness was 11 cm, while the computed t/R ratio—defined as the proportion of sound wood thickness (t) to the tree trunk radius (R), and commonly used to assess fracture resistance—was 0.21. This value falls considerably below the safety threshold, as the coefficient should not be lower than 0.30 [81,82,83,84,85].

The t/R ratio alone is not fully reliable for the final assessment of fracture risk. To achieve a more precise evaluation, the slenderness ratio (h/D)—the ratio of tree height to trunk diameter—is additionally considered. In the case under examination, this coefficient equals 14.7, which, in comparison to the t/R ratio, allows for a more accurate estimate of trunk failure risk. This is of particular importance for public safety. An optimal slenderness ratio is generally considered to be <30, although the value also depends on the growing conditions (habitat). Isolated trees, avenue trees, and those growing in dense stands are assessed differently. European solitary trees usually present h/D values between 25 and 30, whereas in specimens with umbrella-shaped crowns, the optimum is closer to 15 [86,87].

Thus, with relatively thin walls but a larger trunk diameter and a lower overall tree height, fracture resistance will be higher than in a specimen with the same wall thickness but a smaller trunk diameter and greater height. Considering the value obtained and assuming a columnar (pear-shaped) crown, the specimen appears structurally safe. Nevertheless, the significant internal decay—exceeding the norm—reduces overall stability, increasing the risk of trunk failure during extreme weather events.

The geometric moment of inertia calculated in various directions, measured at the weakest points of the cross-section, ranged from 0.1% to 6.8% of maximum strength. The minimum safe wall thickness, as calculated by the TreeSA method, averaged 7.2 cm (green line on the tomogram). The required minimum residual strength of the solid trunk wood should amount to 13%, while tomographic analysis confirmed that the proportion of fully sound wood was slightly higher, at 15%.

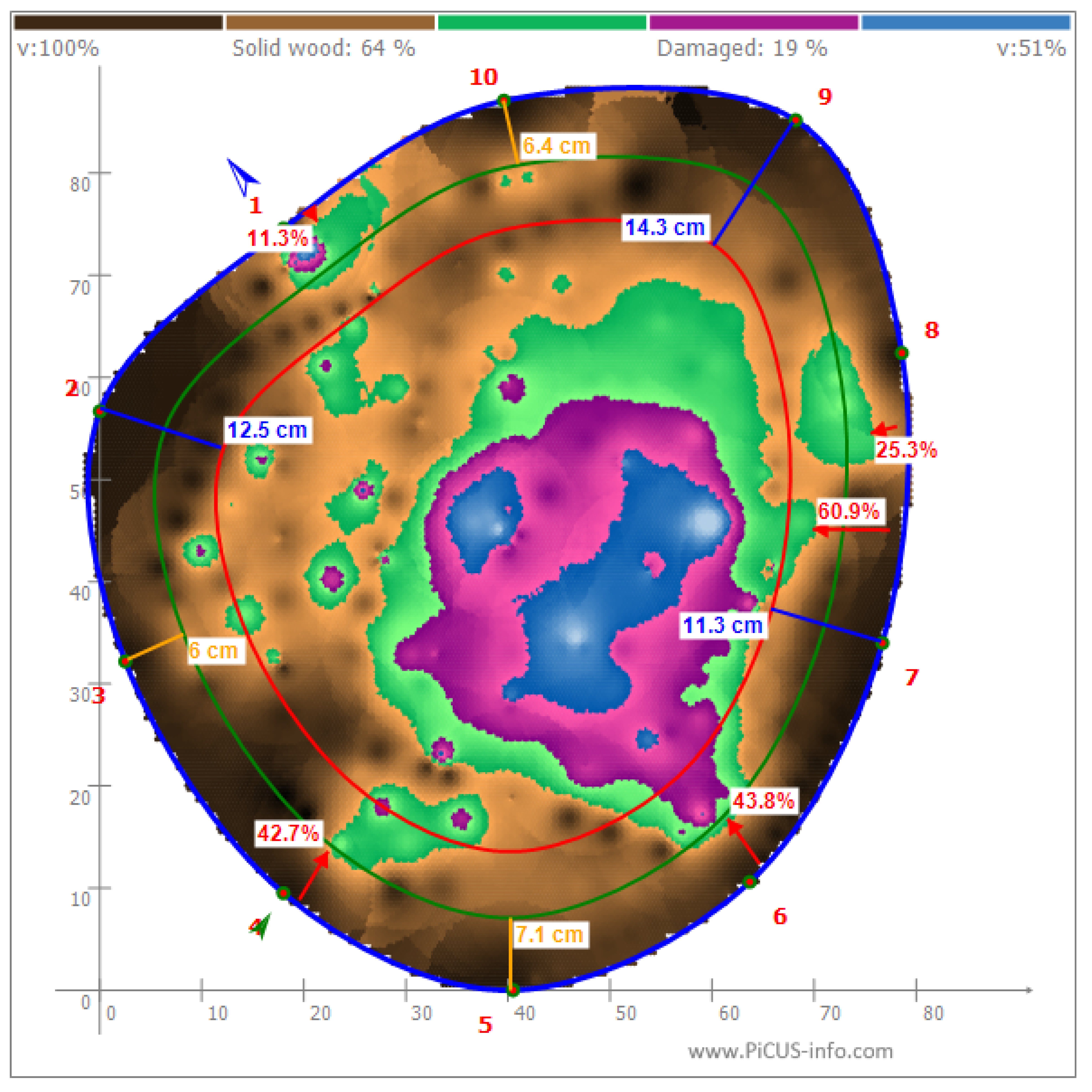

For Tilia cordata no. 17, nine sensors were placed at a height of 1.3 m. The analysis revealed, as in the previous case, severe internal degradation, particularly expanding toward the eastern side. Damaged wood accounted for 74% of the trunk cross-section, sound wood for 16%, and the remainder was transitional wood. The velocity of acoustic waves within the trunk ranged from 433 to 1562 m·s−1. The average minimum safe wall thickness was determined to be 9.1 cm. The t/R ratio equaled 0.26, and the extent of internal damage exceeded the safety threshold. The slenderness ratio (h/D) was calculated at 11.0, below the general average. Due to reduced tree height caused by crown breakage, the risk of failure was assessed as low. The geometric moment of inertia, measured at the weakest points, ranged from 0.3% to 8.3% of maximum strength. The TreeSA-calculated minimum safe wall thickness was 3.8 cm, while the required minimum residual strength was 3%. Tomography indicated that fully sound wood represented 30% of the cross-section. Despite severe internal decay, the tree does not pose a significant safety hazard, primarily due to its lowered center of gravity (Appendix B, Table A2).

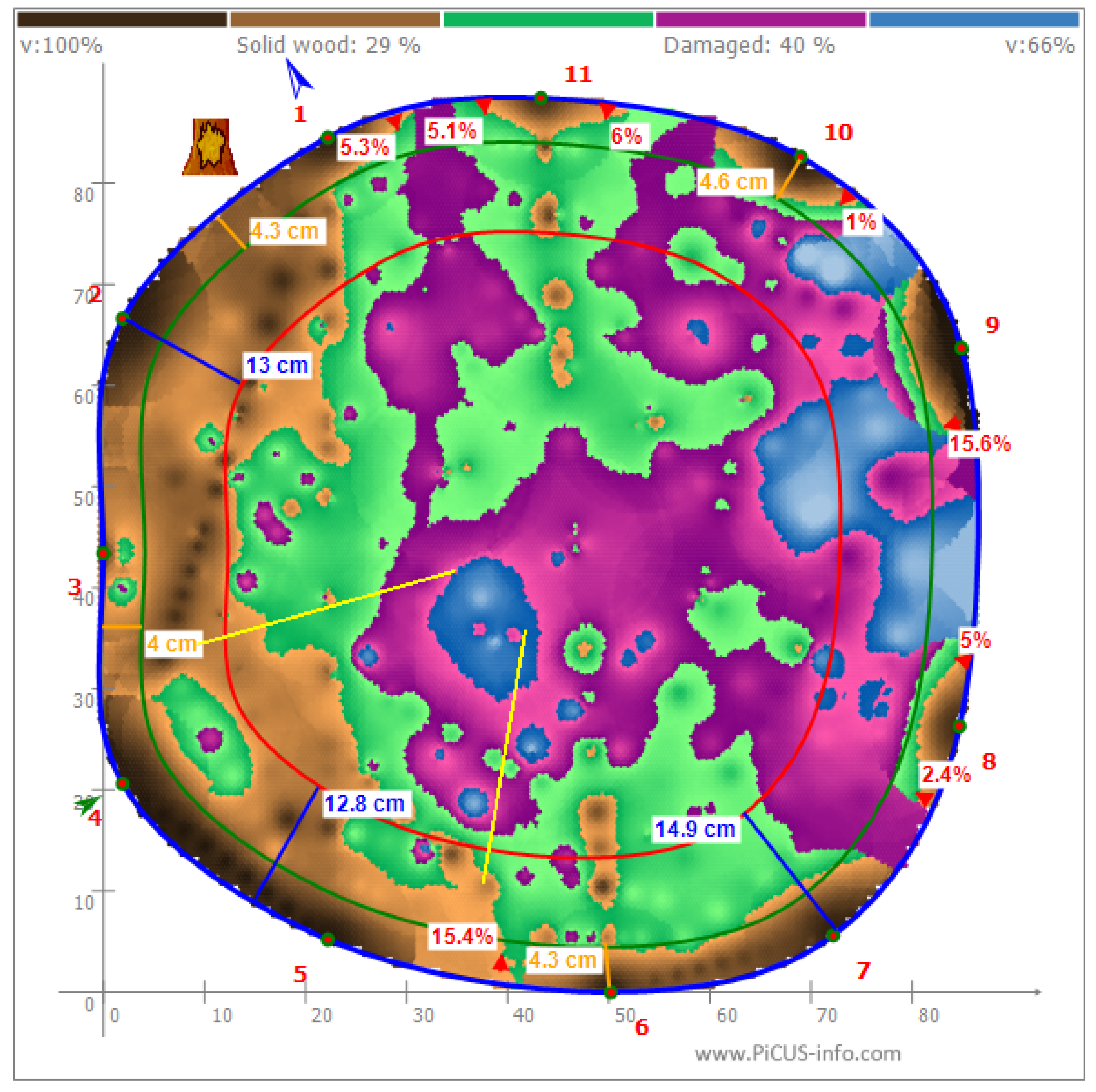

For Tilia cordata no. 29, eight measuring points were positioned at 1.1 m above ground. The tomographic assessment confirmed advanced internal decay: 58% of the cross-section was damaged, 19% sound, and the remainder transitional wood. Acoustic wave velocities ranged from 811 to 1916 m·s−1. The minimum safe wall thickness was estimated at 8.7 cm. The t/R ratio equaled 0.27, slightly below the threshold, suggesting increased fracture risk. However, the slenderness ratio (h/D) was calculated at 13.8, indicating that the risk was not as critical as implied by the t/R ratio alone. Reduced tree height significantly contributed to this lower risk. The geometric moment of inertia at the weakest points ranged between 1.5% and 29.7% of maximum strength. The TreeSA-calculated minimum safe wall thickness averaged 3.8 cm, while the required minimum residual strength was 7%. Tomography revealed that the proportion of fully sound wood was nearly three times higher than the required level, at 19% (Appendix B, Table A2).

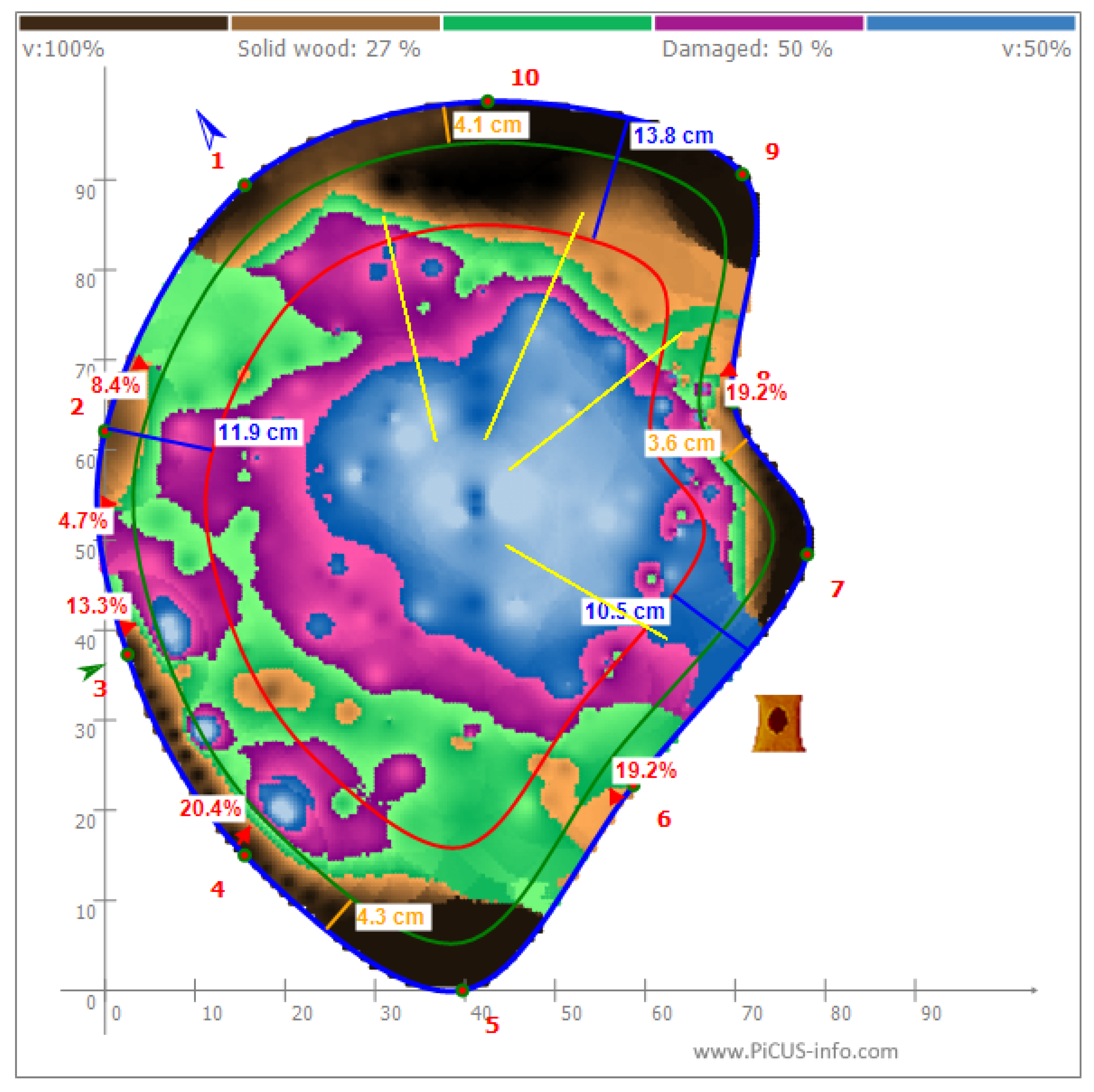

The next specimen analyzed was Tilia cordata no. 34, with 12 sensors placed at a height of 0.3 m. The results indicated advanced decay, with 80% of the cross-section damaged, 10% sound, and 10% transitional wood. Acoustic wave velocities ranged from 212 m·s−1 to 1092 m·s−1; the lowest values indicated a very high level of internal degradation. The minimum safe wall thickness (red line on the tomogram) averaged 22.1 cm, yet decay processes across nearly the entire circumference exceeded safety thresholds. The t/R ratio equaled 0.33, while the slenderness ratio was 0.13, highlighting elevated fracture risk despite a favorable t/R value.

The tree, therefore, requires regular monitoring, and its crown should be reduced to improve safety. Yellow lines visible on the tomogram suggest the presence of potential radial cracks. The geometric moment of inertia at the weakest points ranged from 0.9% to 16.9% of maximum strength. The TreeSA-calculated minimum safe wall thickness was 7.5 cm, while the minimum required residual strength was 9%. Tomography showed that the share of fully sound wood was slightly higher, at 10% (Appendix B, Table A2).

Table 4 presents a comparative summary of tomographic examination results for four trees, including key parameters such as the proportion of sound and decayed wood, t/R and h/D ratios, minimum wall thickness, and risk assessment.

Table 4.

Comparative summary of tomographic assessment results for selected Tilia cordata specimens.

3.3. Results of Physiological Condition Assessment of Trees

To evaluate the physiological state of the assessed tree stand, measurements were carried out using a stress meter. For this purpose, a Fluorometer OS5p+ was applied, enabling an assessment of tree health under the influence of various environmental stress factors. The study results are expressed as chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. The Fv/Fm coefficient, widely used as a diagnostic indicator of plant stress, was adopted as a reliable measure. Optimal values, indicative of good plant condition, range between 0.79 and 0.85 relative units. As noted earlier, both biotic and abiotic stress factors can reduce this coefficient. Values between 0.20 and 0.30 are considered critical, reflecting irreversible physiological changes.

The conducted measurements showed no significant deviations from the norm. The obtained Fv/Fm values were slightly below the optimal range but did not approach the critical threshold at which structural changes in Photosystem II (PSII) become irreversible.

On each tree, seven shaded clips were placed on leaves in different parts of the crown. After 30 min, chlorophyll fluorescence was measured. The lowest values of the physiological indicator were recorded in linden no. 12 (Fv/Fm = 0.715), 32 (Fv/Fm = 0.720), and 16 (Fv/Fm = 0.737) (Appendix A, Table A1). These results suggest that the mentioned trees are growing under stress conditions and that their vitality is unsatisfactory.

In the case of linden no. 12, this finding is supported by data in the basic diagnostic form (Appendix A, Table A1) and visual inspection: more than 40% branch dieback, chlorotic and small leaves, several cavities, and probable root system damage caused by paving works carried out a few years earlier. The tree is located at the entrance to a parking area, within a partly paved zone. According to the Roloff classification, the tree was rated at level II, i.e., reduced growth and poor vitality.

For linden no. 15, the presence of bilateral trunk cracks stabilized with a rigid brace indicates a weakened condition (Roloff class I). Despite limited branch dieback, most of the tree’s energy is directed toward wound closure and regeneration. This is evidenced by abundant callus tissue development at the damage sites. Consequently, chlorophyll fluorescence values were lower compared to other trees, reflecting stress symptoms and reduced growth.

Linden no. 32 represents a typical example of stress-inducing growth conditions. The strong limitation of root development due to extensive paving within the crown projection zone, along with probable root damage from soil level alterations during the construction of a large concrete basin, resulted in significantly reduced Fv/Fm values. Such unfavorable conditions contribute to the decline in vitality. It should be emphasized that any works within the crown projection area inevitably lead to some degree of root damage, which may manifest years later as reduced tree health.

The best physiological condition, considering stressful growth conditions, was recorded for lindens no. 20, 22, and 24. Their chlorophyll fluorescence values were 0.810, 0.808, and 0.809 relative units, respectively, placing them within the optimal range. This indicates good physiological condition despite minor injuries. Relatively small branch dieback and effective wound healing suggest that these trees are coping well with stress.

Other trees displayed variable physiological states. For 17 trees, the Fv/Fm indices were below the optimal lower limit, whereas 12 specimens exceeded 0.790.

In summary, the majority of the examined trees are not growing under ideal site conditions, and their physiological condition is consequently reduced. The main contributing factors include heavily paved surfaces, restricted root development space, advanced age of some specimens, and progressive internal wood decay.

The results of chlorophyll fluorescence in the trees forming the linden row are presented in Appendix A, Table A1, Column 7.

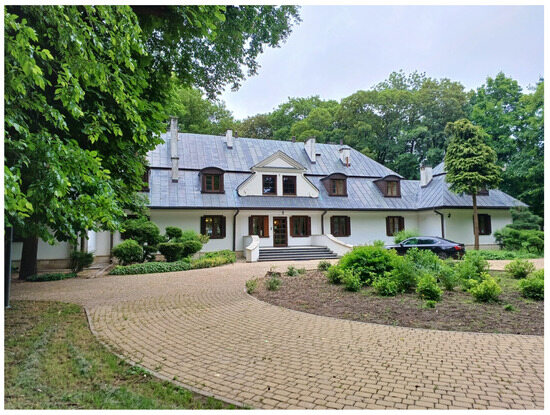

3.4. Correlation Analysis

A correlation analysis was performed based on the collected data. The Pearson correlation coefficient between the proportion of sealed surfaces within the TPZ (Tree Protection Zone) and the Fv/Fm index (tree vitality) was −0.12. This indicates a weak negative relationship: the higher the degree of surface sealing around the trees, the lower their physiological vitality, although the effect is not strong. The scatter plot clearly shows the distribution of points and a red regression line with a slight downward slope, which confirms the direction of this relationship (Figure 19, Table 5).

Figure 19.

Correlation between paving coverage and Fv/Fm in linden avenue.

Table 5.

Mean Fv/Fm values by degree of surface sealing (TPZ).

Pearson’s correlation analysis yielded a coefficient of r = −0.117 with p = 0.518, indicating no statistical significance (p > 0.05). This means that, although the trend suggests lower tree vitality with increasing soil sealing, the relationship is not statistically significant in this dataset.

The results indicate that trees growing in zones with high surface sealing (>75%) exhibit the lowest mean vitality values (Fv/Fm = 0.759), whereas trees in medium and low sealing zones show similar, higher values (~0.782). These differences are consistent with expectations, reflecting the negative impact of impermeable surfaces on tree physiological performance. Highly sealed surfaces limit soil water infiltration, gas exchange, and root expansion, which in turn exacerbate physiological stress and reduce photosynthetic efficiency. However, the observed relationship remains statistically weak, suggesting that additional factors, such as tree age, microclimatic variation, or past management practices, may also influence the measured vitality indices. This indicates that, while surface sealing is an important stress factor, tree vitality results from a combination of multiple interacting environmental and biological variables. Given the sample size and environmental complexity, this study primarily focused on the direct correlation between surface sealing and the vitality index, while future research could incorporate more covariates for multivariate analysis.

Although Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated a negative trend between the proportion of sealed surfaces and the Fv/Fm index (r = −0.117), this relationship was not statistically significant (p = 0.518). The statistical analysis confirmed a weak negative correlation between the proportion of sealed surfaces within the Tree Protection Zone (TPZ) and the Fv/Fm vitality index, suggesting that higher levels of surface sealing may reduce tree vitality. The analysis of mean values showed that trees growing in areas with high surface sealing (>75%) exhibited lower Fv/Fm values (0.759) compared to trees in areas with medium (0.782) and low (<50%) sealing (0.783). This trend aligns with expectations regarding the negative impact of soil sealing on tree physiological condition; however, the differences were not pronounced enough to be considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

This integrated diagnostic study of a historic linden avenue revealed that, while the trees exhibited widespread internal structural degradation (tomography results), their overall physiological stress levels remained within a manageable range (chlorophyll fluorescence results). This contrast reflects a well-documented phenomenon in urban tree populations: advanced internal decay does not necessarily translate into immediate physiological decline. At the same time, environmental stressors—particularly a high degree of surface sealing—showed a negative trend impacting tree vitality.

The observed correlation between surface sealing and Fv/Fm was negative but statistically insignificant. Several factors may explain this result. First, a sample size of only a few dozen trees combined with the narrow Fv/Fm range (approximately 0.71–0.81) reduces statistical power to detect weak effects. Detecting subtle physiological declines would likely require larger sample sizes and multi-season measurements [88,89].

Second, numerous co-variables may mask the effect of surface sealing during a single growing season. These include tree age, pruning history, previous damage, soil volume in the tree pit, shading and façade energy balance, water and mycorrhiza availability, and minor genetic differences. Previous research confirms that surface sealing affects key soil properties and ecological functions—including soil moisture, root architecture, growth dynamics, and ecosystem services [90].

Third, a tree may exhibit advanced internal heartwood decay while maintaining photosynthetic activity within a normal range due to compartmentalization and the leaf–root balance. This explains why substantial internal degradation sometimes coexists with still “acceptable” Fv/Fm values [91,92]. By nature, chlorophyll fluorescence provides an early signal of physiological stress but does not always correlate immediately with the mechanical properties of the trunk.

Research on urban street trees, including Tilia, has shown that internal decay and cavities are common and often develop without dramatic crown symptoms. Sonic/acoustic tomography has proven effective in visualizing decay zones and cavities and in assessing cross-sectional integrity. Its results correspond well with other diagnostic methods and load tests [1,4,92].

Our tomographic findings—indicating extensive but spatially heterogeneous degradation—are consistent with reports from other European cities. Field studies in Northern Europe (e.g., Helsinki) have documented frequent cavities and heartwood decay in “problematic” Tilia trees. Polish case studies have also demonstrated the usefulness of PiCUS technology for assessing aging linden trees in historic avenues. This background supports the conclusion that advanced decay observed in part of the population is not an anomaly but reflects a broader trend in mature urban tree stands [92,93].

Although the correlation between “% surface sealing” and Fv/Fm was weak, the direction of the effect is consistent with findings reported in the literature on the impact of surface sealing on urban tree condition. Combining sonic tomography with chlorophyll fluorescence provides a complementary approach, integrating early physiological warning (chlorophyll fluorescence analysis) with objective structural risk assessment (tomography).

This integrated diagnostic strategy enables more nuanced and adaptive management decisions. A tree with high structural risk and reduced Fv/Fm should be prioritized for stabilizing measures or crown load reduction. In contrast, a tree with poor tomographic results but still good Fv/Fm qualifies for monitoring rather than automatic removal. Furthermore, if the Fv/Fm trend deteriorates with increasing surface sealing (as observed here—a weak negative trend), there is a clear basis for interventions such as loosening sealed surfaces, increasing the share of permeable materials, and applying mycorrhiza. Repeated CF measurements can also assess whether interventions (e.g., watering) actually improve tree physiology before any visible canopy decline occurs.

Urbanization induces profound transformations in environmental systems, including changes in radiation balance and local meteorological conditions, due to land-cover alteration and modification of the physical environment. Cities generate specific microclimates arising from the heterogeneity of the urban fabric. The occurrence of impermeable surfaces is a direct and unequivocal indicator of human activity [89]. Impermeable surfaces—typically asphalt, concrete, brick, steel, and aluminum [90]—reduce biologically active areas, promote urban heat island formation [91], and limit water infiltration and gas exchange critical for root health.

Historically, the surface of the studied avenue was unpaved or occasionally reinforced with gravel and stones. Currently, the average level of paving around the 34 trees is 60%. Over the past five years, new walkways have been placed too close to the trunks, and parking bays have been introduced between trees, directly within the crown projection zone. Research confirms that ground cover significantly affects tree condition [92,93,94,95]. Celestian and Martin (2004) [96] demonstrated that in summer, soil temperature at 1 m from asphalt exceeds 40 °C—a critical threshold for root tissues, resulting in direct and indirect physiological damage. Proximity to the road also correlates with poorer crown health, while mechanical injuries caused by vehicles, pedestrians, and construction activities exacerbate stress [97,98].

Construction processes further modify local microclimates, typically making them less favorable for tree development [99]. In this case, two modern glass-façade buildings were constructed only a few dozen meters from the avenue. Reflective surfaces such as façades, pavements, and parked vehicles significantly increase local temperatures on sunny days. Post-construction, trees often remain in small, enclosed spaces surrounded by buildings, exposed to both direct and reflected radiation [100,101,102].

Although the preserved trees continue to provide significant visual, ecological, and cultural value, most require targeted maintenance and site improvements. The most critical negative factor is the extensive impermeable paving over the root zones. Many trees show signs of crown dieback, while some lean toward the light, compromising structural stability. In several cases, dead branches overhang traffic routes, posing safety risks.

Effective management should include regular monitoring of tree health, ideally through annual VTA inspections supported by instrumental diagnostics such as sonic tomography and chlorophyll fluorescence analysis. Cyclical arboricultural treatments (deadwood removal, sucker pruning, crown correction) should aim to improve structural stability. In trees with cavities or reduced mechanical stability, the use of bracing systems or rigid supports is recommended.

Improving site conditions by replacing impermeable surfaces with permeable materials is crucial for enhancing gas exchange and water retention in the root zone. Additional measures, such as mycorrhizal inoculation, targeted fertilization, and soil aeration, can further support tree vitality. Protection against erosion and mechanical damage, particularly in areas exposed to traffic, is also essential. From a planning perspective, integrating the historical and ecological value of the avenue into urban development strategies is critical to ensuring its preservation. Educational and community engagement initiatives can further reinforce its role as both a landscape element and a living cultural heritage.

The historical value of linden avenues is deeply embedded in the European landscape tradition. The oldest known avenue in Europe—and probably worldwide—was established between 1615 and 1619 in Hellbrunn near Salzburg. Of the nearly 700 trees originally planted, only a dozen Tilia cordata survive today [99]. In Poland, the linden avenue in Margonin (Greater Poland Voivodeship), dating back to 1765, is among the oldest preserved [99,100,101,102,103], while the monumental “Great Avenue” in Gdańsk–Oliwa, planted between 1768 and 1770 with 1416 linden trees imported from the Netherlands, remains one of the most recognizable historic green structures [104,105].

This historical context underscores both the cultural and ecological significance of avenues as living heritage and key components of urban green infrastructure. Their preservation requires a combination of advanced diagnostic tools, evidence-based arboricultural care, and adaptive planning strategies.

Table 6 below presents the species composition of historical avenues in selected regions of the world, illustrating how tree selection varied across different landscape traditions and historical periods (from the Baroque era to the 19th and 20th centuries).

Table 6.

Historic avenues around the world—species composition [compiled by the authors based on [106,107,108,109,110,111]].

Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

It is important to acknowledge certain limitations of this study. The research covered a single avenue and a relatively short observation period (2024–2025), which constrains the ability to draw broader generalizations. The analysis did not include a full identification of fungal pathogens or pests that may significantly affect tree condition. Although modern diagnostic tools provided valuable data, they reflect only a single point in time and do not allow for long-term projections of tree health dynamics. Future work will focus on establishing a long-term monitoring program to track the rate of degradation processes over multiple years. Special emphasis will be placed on soil parameters such as water-air properties and organic matter content, as well as microclimatic conditions, including the impact of the urban heat island. Another key direction is the development of computational models to predict tree stability under extreme weather events. Comparative studies involving other historic avenues in Poland would provide a broader perspective, helping to identify common challenges and develop more universal conservation strategies.

5. Conclusions

The preservation of old roadside trees in urbanized areas presents both challenges and opportunities for sustainable urban planning. The results emphasize that maintaining such trees requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates green microbiology, landscape architecture, and environmental protection strategies.

Based on the health assessment of the small-leaved linden (Tilia cordata) avenue located on the Catholic University of Lublin campus at 1 Konstantynów Street, it was determined that the trees are generally in moderate condition. Both visual assessments (VTA—Visual Tree Assessment) and advanced diagnostic tools (Picus 3 sonic tomography and OS5p+ fluorometer) revealed that most specimens show varying levels of internal decay, branch dieback, and other defects. Their condition is strongly influenced by unfavorable soil and habitat conditions: intensive land use, heavy paving within the crown projection zone, and restricted root development space. These factors contribute to growth suppression, increased branch dieback, and elevated stress.

Tomographic analyses, performed on nearly half of the trees, confirmed advanced internal decay at different stages. Despite their evident deterioration, the trees should be preserved and maintained in the best possible condition. The species’ natural predispositions further complicate the situation: lindens have soft wood highly susceptible to biocorrosion, brittle branches prone to breakage, and high vulnerability to mechanical stress under extreme weather. This underscores the importance of timely and appropriate arboricultural interventions, including dynamic or static bracing, or in extreme cases, rigid bracing through-bolting.

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements confirmed stress conditions: trees in the most heavily paved zones exhibited the lowest Fv/Fm values. Special attention should be given to trees growing in concrete basins, where poor habitat conditions have weakened their vitality. Improvement measures—such as mycorrhizal inoculation and targeted fertilization—are recommended to restore root systems that may have been reduced during past construction works. The use of advanced diagnostic methods (chlorophyll fluorescence, tomography) combined with targeted habitat enhancement measures represents an innovative approach to the conservation and management of historic tree avenues in urban environments.

Large trees growing on the slope at the campus entrance face additional stress from soil erosion and root exposure. For example, the linden beside the roadside shrine has severely reduced roots due to erosion, necessitating corrective measures such as crown reduction to improve stability.

Other trees exhibit trunk and crown deformities, leaning toward streets or sidewalks, often due to asymmetric growth, poor pruning, or nearby construction. Inadequate arboricultural practices increase susceptibility to fungal infections and gradual decline, raising the risk of branch or limb failure. Therefore, maintenance of old trees must be carried out with great care, and health monitoring should occur at regular intervals to detect concerning changes early.

The main conservation guidelines for further care of the linden avenue in Konstantynów are as follows:

- Annual tree health inspections at the beginning of the growing season—in response to the widespread internal decay and the need for continuous monitoring of structural risk.

- Cyclical arboricultural treatments, such as deadwood and basal sprout removal, aimed at mitigating the effects of crown dieback and crown deformation observed in many trees.

- Crown correction, monitoring of main branches, and, where necessary, installation of flexible bracing systems—intended to reduce risks associated with hollow trunks and asymmetric crown loading, which increase the likelihood of mechanical failure.

- Mycorrhizal treatments and improvement of rooting conditions—in response to limited rooting space, soil compaction, and reduced physiological vitality resulting from a high degree of surface sealing.

Such a problem-oriented approach allows for more targeted, cost-effective, and adaptive actions, ensuring both public safety and the long-term vitality of the trees (Table 7).

Table 7.

Maintenance measures in historic tree avenues (prepared by the authors).

Green infrastructure management should be an integral part of urban development policy and incorporated into relevant planning documents, whether through dedicated strategies or complementary frameworks. The protection of urban tree populations requires cross-disciplinary cooperation between microbiologists, environmental scientists, landscape architects, and urban planners. Collaboration among researchers, policymakers, and local communities is essential to developing effective tree protection and greening strategies. Such interdisciplinary approaches must support long-term monitoring of both the environment and tree health.

The interdisciplinary significance of the findings highlights their potential contribution to several research and practical fields, including landscape architecture, urban ecology, heritage conservation, and environmental planning. By integrating ecological, cultural, and spatial perspectives, this research provides a valuable framework for the sustainable management of historic tree avenues within contemporary urban landscapes.

The integration of heritage conservation, arboriculture, and environmental monitoring offers a robust and transferable model of sustainable management for urban green spaces. Historic tree avenues, as both cultural artifacts and ecological assets, require management strategies that transcend traditional sectoral divisions. By combining conservation values with evidence-based arboricultural practice and long-term environmental monitoring, cities can strengthen ecological resilience while safeguarding cultural identity.

Such an interdisciplinary framework not only enables early detection of stress factors and structural risks but also supports adaptive management in response to changing climatic and urban pressures. In this way, historic greenery becomes an active driver of sustainable urban and rural development, contributing simultaneously to biodiversity preservation, climate adaptation, and landscape continuity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.D. and M.D.-P.; methodology, W.D. and M.D.-P.; software, W.D., M.D.-P. and P.S.; formal analysis, W.D., M.D.-P. and P.S.; investigation, W.D., M.D.-P. and P.S.; data curation, W.D., M.D.-P. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation M.D.-P.; writing—review and editing, W.D.; supervision, W.D. and M.D.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The research was not supported by any external funding. The publication of the research was financed from the own funds of the Institute of Horticultural Production.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Applendix A. Results of the Detailed Dendrological Inventory of the Linden Avenue on the KUL Campus at Konstantynów Street in Lublin

Table A1.

Results of the detailed dendrological inventory of the linden avenue on the campus of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Konstantynów Street, Lublin (compiled by the authors).

Table A1.

Results of the detailed dendrological inventory of the linden avenue on the campus of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Konstantynów Street, Lublin (compiled by the authors).

| No. | Latin Name | Trunk Circumference at 130 cm | Height (m) | Crown Spread +1 m (m), Tree Protection Zone (TPZ) (m2), and Paved Surface Within TPZ (%) | GPS Location | Mean Fv/Fm Index Value Fv/Fm | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 456 | 20.0 | 18.3 × 14.4 TPZ~210 m2 73% TPZ | 51°14′11.7″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.790 | The trunk branches at a height of 1.6 m into three leaders. The western leader is inclined at an angle of 30°. The fork is U-shaped. Within the fork, there is a recessed cavity measuring 0.2 × 0.2 m, extending down to the trunk base. On the southern leader, at the fork, there is a recessed cavity of 0.2 × 0.1 m with callused edges. Numerous basal shoots are present. On the southern side, there is an open recessed cavity with visible internal decay and callused edges, measuring 0.8 × 0.3 m. Traces of sanitary pruning are visible. Leaves are typical of the species, though smaller in the upper crown. Minor branch dieback is observed (10%). Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches. |

| 2 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 156 + 200 | 16.0 | 13.2 × 6.9 TPZ~80 m2 73% TPZ | 51°14′12.1″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.786 | A twin-stemmed tree, branching at a height of 1.16 m with a U-shaped base. The western leader is strongly inclined to the south, becoming vertical at a height of 4 m. Leaves are typical of the species, though smaller in the upper crown. In the crown apex, on the northern leader, there are large dead branches. Branch dieback amounts to 10%. Numerous basal shoots are present at the trunk base. On the northern side, at a height of 0.6 m, there is an open recessed cavity reaching down to the trunk base, measuring 0.23 × 0.05 m. Partial bark losses are visible, mostly callused. The crown is markedly asymmetric. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches. |

| 3 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 310 | 16.4 | 16.4 × 7.4 TPZ~111 m2 72% TPZ | 51°14′12.2″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.795 | A tree branching at a height of 2.5 m into three leaders. The crown is asymmetric. On the western side, at a height of 2.3 m, there is an open recessed cavity measuring 0.2 × 0.2 m. On the northern leader, traces of large branch removal are visible. Foliage is normal, except for the upper crown where the leaves are smaller. Minor branch dieback is present. At the site of a pruned limb, fungal fruiting bodies are observed. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches. |

| 4 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 225 | 17.8 | 16.6 × 6.9 TPZ~108 m2 69% TPZ | 51°14′12.3″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.790 | A large open cavity on the western side at a height of 0.7 m, measuring 0.8 × 0.3 m. The wound edges are callused, but with a tendency toward decay. The cavity interior shows traces of chiseling, reaching deep into the trunk core. The trunk forks at a height of 3.4 m. A slight crown asymmetry is present. Leaves in the upper crown are smaller and chlorotic. Minor branch dieback is observed. Evidence of previous maintenance treatments is visible. Numerous basal shoots occur at the trunk base. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches and basal shoots. |

| 5 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 335 | 18.0 | 18.7 × 8.0 TPZ~140 m2 67% TPZ | 51°14′12.4″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.798 | A tree branching into two leaders at a height of 1.6 m. The northern leader shows a crack on its northern side, callused to a depth of 0.1 m. Traces of removed branches are visible, with well-callused edges. The crown is narrow, extending east–west. The trunk has numerous swellings and thickenings. Leaves are normal, very abundant in the lower crown; in the upper crown, foliage is sparser and smaller. Branch dieback is at the level of 10–15%. Few basal and epicormic shoots occur at the trunk base and at sites of major branch removal. The crown base is V-shaped. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches and installation of crown bracing. |

| 6 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 332 | 15.6 | 16.2 × 9.2 TPZ~127 m2 55% TPZ | 51°14′12.5″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.783 | Traces of previous maintenance treatments are visible. On the north-western side, at a height of 1.5 m, there is an open recessed cavity measuring 0.4 × 0.15 m with signs of internal decay. Numerous chiseling marks are present. Numerous basal shoots occur at the trunk base. On the southern side, two hollows are present: one at 2.1 m (0.5 × 0.15 m) and another at 3.6 m (0.3 × 0.3 m). The trunk branches at a height of 3.3 m. In the crown, at a height of 10 m, a rope bracing connects the northern and western limbs. Minor branch dieback is observed (10%). The crown is symmetrical, extending in an east–west direction. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches. |

| 7 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 269 | 13.8 | 19.8 × 12.5 TPZ~205 m2 73% TPZ | 51°14′12.8″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.782 | Numerous epicormic shoots on the trunk and at the base. On the western side, at 3.2 m, a scar from a removed large leader with partially callused edges shows signs of heartwood decay extending downward, most likely forming a chimney-type cavity. In the crown, numerous branch breakages are visible. On the eastern side, several dead branches are present. The crown is well foliated up to approximately half its height, above which foliage becomes sparse. Most limbs and branches are oriented east–west. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches, corrective and sanitary pruning. |

| 8 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 345 + 277 | 18.8 | 20.0 × 18.2 TPZ~286 m2 81% TPZ | 51°14′13.0″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.781 | A twin-stemmed tree branching at 0.9 m in a V-shape. The southern leader is slightly inclined southward at a 25° angle. The crown is densely foliated up to mid-height. Leaves are normal, typical of the species, though smaller in the upper crown. Branch dieback amounts to 15%, with numerous dead branches. The crown is symmetrical. In the southern part of the crown, several suspended dead branches are present. On the southern leader, branch junctions are V-shaped. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches and installation of crown bracing. |

| 11 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 300 | 15.4 | 12.7 × 9.7 TPZ~99 m2 78% TPZ | 51°14′13.5″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.774 | Bark peeling on the northern side at 2 m. The trunk forks in a V-shape at 2.5 m. On the western side, an open recessed cavity measuring 0.15 × 0.15 m is present. At the junction of the main limbs, a bark inclusion is visible. The tree trunk stands 1–1.5 m from the curb of a traffic route. Leaves are small. Significant branch dieback (25%), mainly in the upper crown, with numerous dead branches. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 2. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches; application of mycorrhiza and soil fertilisation. |

| 12 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 270 | 13.0 | 13.4 × 7.4 TPZ~85 m2 88% TPZ | 51°14′13.9″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.715 | Tree slightly inclined southward (10°). Numerous swellings at the trunk base. At the root collar, a large open cavity (0.23 × 0.32 m) extends into the entire trunk interior. Numerous traces of removed branches are visible. The trunk stands 0.8 m from the curb. Very high branch dieback (40–45%) with numerous dead branch tips. Leaves in the crown apex are small and chlorotic. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 1. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches. |

| 13 | Tilia cordata Mill. | 268 | 20.6 | 14.3 × 9.3 TPZ~110 m2 90% TPZ | 51°14′14.1″ N 22°30′03.8″ E | 0.775 | A tree branching at 3.3 m into two leaders. On the southern side, bark is partly peeling with a callused crack extending from the trunk base to 3 m. The trunk is straight with limbs oriented south and west. Traces of sanitary pruning are visible in the crown. Branch dieback is 30%, with numerous dead branches. Foliage is average, smaller, and chlorotic in the crown apex. On the southern limb, signs of fungal infection are observed above and below the site of a removed branch. Vitality according to Roloff’s scale: 2. Recommendations: Removal of dead branches; application of mycorrhiza and soil fertilisation. |