Does ESG Washing Increase Abnormal Audit Fees? Research Based on the Chain Mediating Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review, Theoretical Analysis, and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Literature Review

2.1.1. Abnormal Audit Fees

2.1.2. ESG Washing

2.1.3. Main Contributions

2.2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

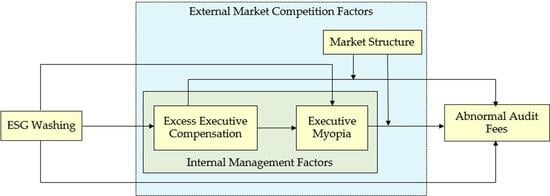

2.2.1. ESG Washing and Abnormal Audit Fees: Analytical Framework

2.2.2. The Mediating Role of Excess Executive Compensation

2.2.3. The Mediating Role of Executive Myopia

2.2.4. The Chain Mediating Role of Excess Executive Compensation and Executive Myopia

2.2.5. The Moderating Role of Market Structure

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data Sources

3.2. Variable Definitions

3.2.1. Independent Variable: ESG Washing (ESGW)

3.2.2. Dependent Variable: Abnormal Audit Fees (ABAUFE)

3.2.3. Mediating Variables: Excess Executive Compensation and Executive Myopia

3.2.4. Moderating Variable: Market Structure (MAST)

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Model Specification and Empirical Strategy

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Analysis of Regression Results

4.2.1. Total Effect Path Analysis

4.2.2. Direct Effect Path Analysis

4.2.3. Mediating Effect and Chain Mediating Effect Path Analysis

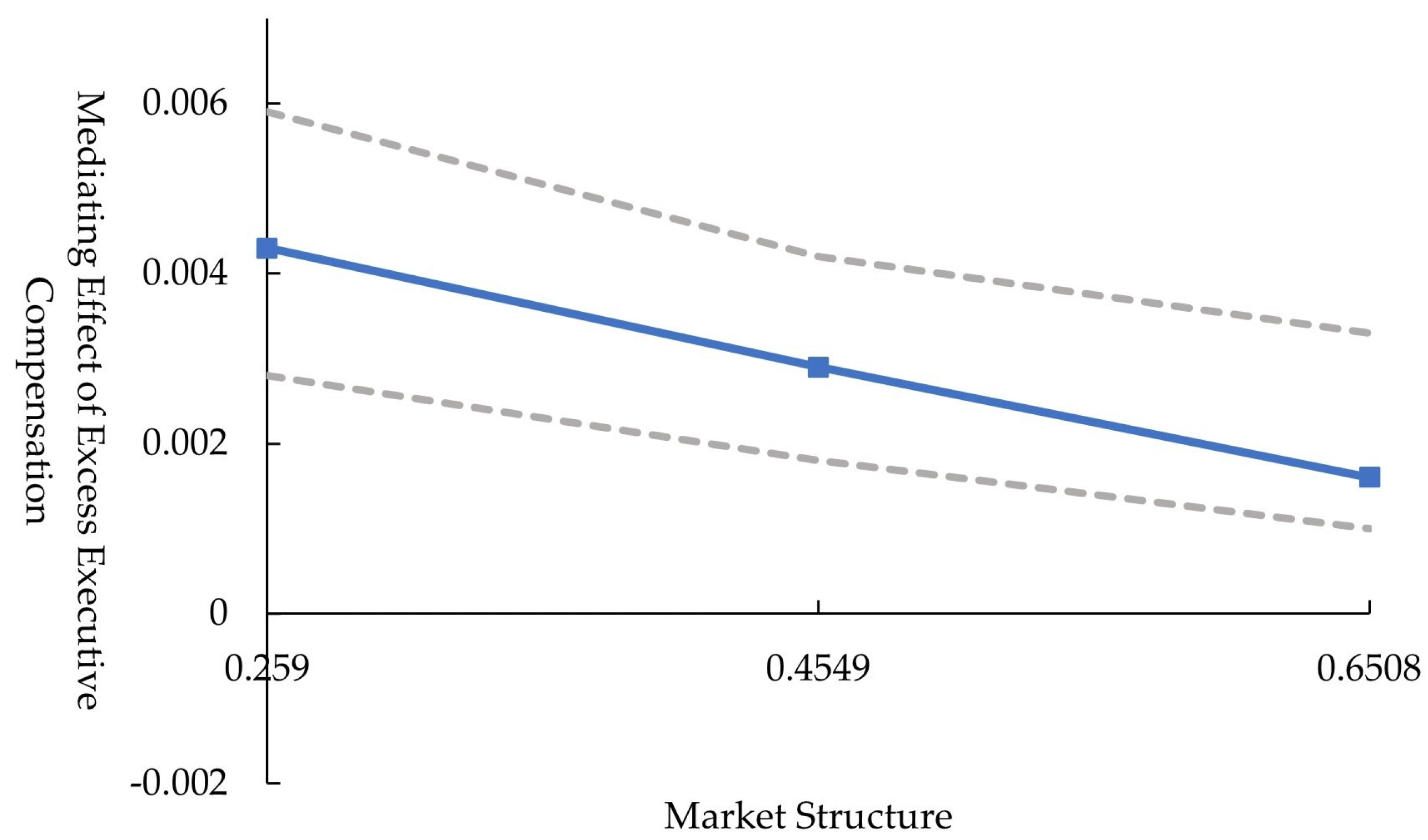

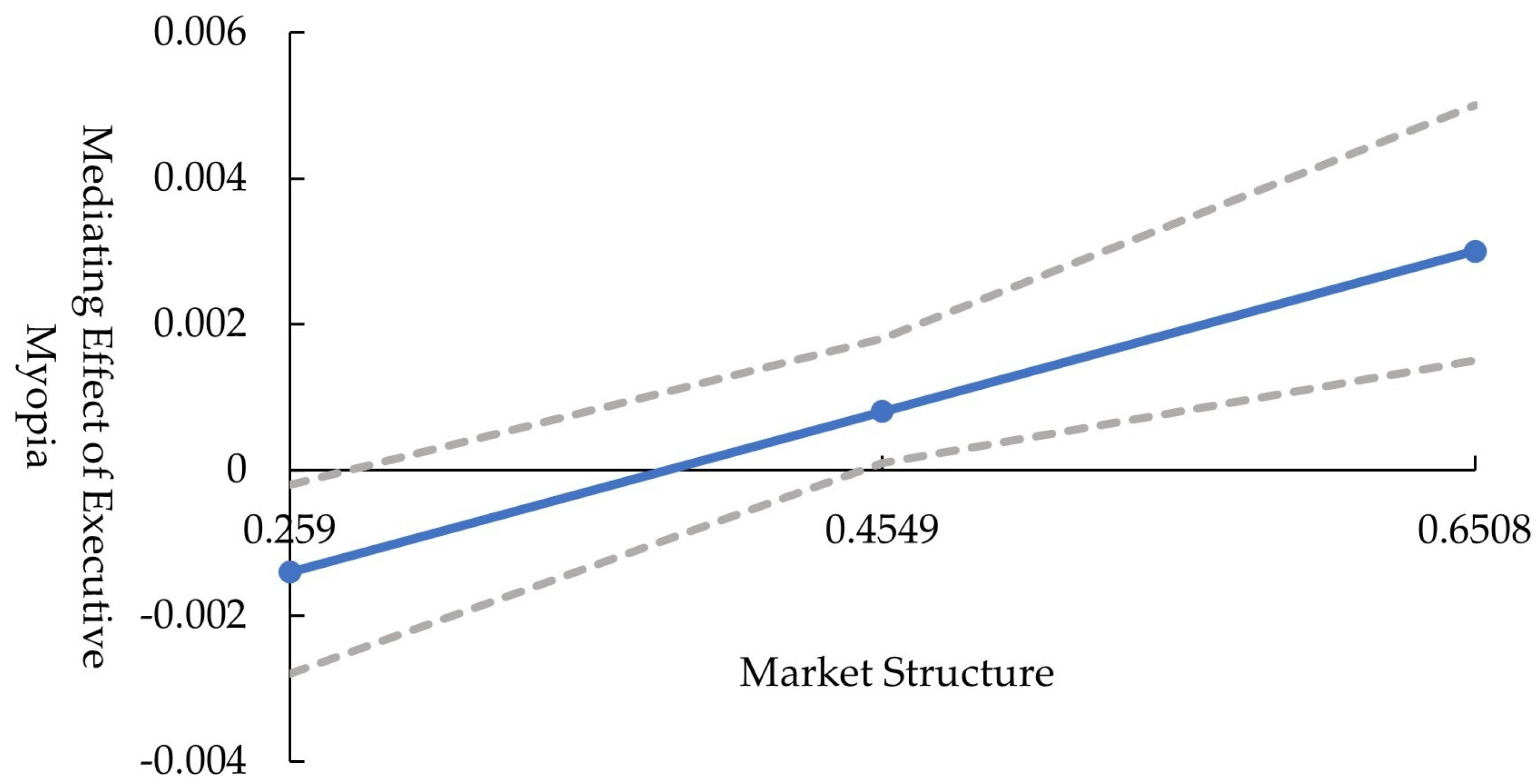

4.2.4. Moderated Mediating Effect Test

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Alternative Dependent Variable

4.3.2. Lagged Explanatory Variable

4.3.3. Grouped Test by Managerial Tone

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of the Total Effect

5.2. Discussion of the Direct Effect

5.3. Discussion of Mediating and Chain Mediating Effects

5.4. Discussion of Moderated Mediating Effects

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Research Conclusions

Extraction of Principal Components

6.2. Managerial Implications

6.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walker, K.; Wan, F. The harm of symbolic actions and green-washing: Corporate actions and communications on environmental performance and their financial implications. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudłak, R. Greenwashing or Striving to Persist: An Alternative Explanation of a Loose Coupling Between Corporate Environmental Commitments and Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 197, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Ee, M.S.; Hasan, I.; Huang, H. Asymmetric reactions of abnormal audit fees jump to credit rating changes. Br. Account. Rev. 2024, 56, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. Voluntary agreements to improve environmental quality: Symbolic and substantive cooperation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Miroshnychenko, I.; Barontini, R.; Frey, M. Does it pay to be a greenwasher or a brownwasher? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, B.P.; Wang, D. The earnings quality information content of dividend policies and audit pricing. Contemp. Account. Res. 2016, 33, 1685–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R.M.; Smith, A.J. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 32, 237–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, C.L.; Nicolai, A.T.; Covin, J.G. Are founder-led firms less susceptible to managerial myopia? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2020, 44, 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porumb, V.A.; Zengin-Karaibrahimoglu, Y.; Lobo, G.J.; Hooghiemstra, R.; De Waard, D. Expanded auditor’s report disclosures and loan contracting. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 38, 3214–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, C.E.; Wilkins, M.S. Evidence on the audit risk model: Do auditors increase audit fees in the presence of internal control deficiencies? Contemp. Account. Res. 2008, 25, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, C.W. Directors’ and officers’ liability insurance and the sensitivity of directors’ compensation to firm performance. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 45, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, K.L.; Cunningham, L.M.; Myers, L.A. Small audit firm membership in associations, networks, and alliances: Implications for audit quality and audit fees. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 767–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, H.G.; Qiao, P.; Yau, J.; Zeng, Y. Leader narcissism and outward foreign direct investment: Evidence from Chinese firms. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.H.; Chen, G. CEO narcissism and the impact of prior board experience on corporate strategy. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015, 60, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Soileau, J. Enterprise risk management and accruals estimation error. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2020, 16, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.A.; Wu, D.; Yang, Z. Do individual auditors affect audit quality? Evidence from archival data. Account. Rev. 2013, 88, 1993–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Raman, K.K.; Sun, L.; Wu, D. The effect of ambiguity in an auditing standard on auditor independence: Evidence from nonaudit fees and SOX 404 opinions. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2017, 13, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFond, M.L.; Subramanyam, K.R. Auditor changes and discretionary accruals. J. Account. Econ. 1998, 25, 35–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copley, P.; Douthett, E.; Zhang, S. Venture capitalists and assurance services on initial public offerings. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wu, H.; Ma, Y. Does ESG performance affect audit pricing? Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2023, 90, 102890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simunic, D.A. The pricing of audit services: Theory and evidence. J. Account. Res. 1980, 18, 161–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, I.; Sulistiyo, U.; Diah, E.; Rahayu, S.; Hidayat, S. The influence of internal audit, risk management, whistleblowing system and big data analytics on the financial crime behavior prevention. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2022, 10, 2148363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doxey, M.M.; Lawson, J.G.; Lopez, T.J.; Swanquist, Q.T. Do investors care who did the audit? Evidence from Form AP. J. Account. Res. 2021, 59, 1741–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohwasser, E.; Zhou, Y. Earnings Management, Auditor Changes and Ethics: Evidence from Companies Missing Earnings Expectations: E. Lohwasser, Y. Zhou. J. Bus. Ethics 2024, 191, 551–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, D.M.; Serafeim, G.; Sikochi, A. Why is corporate virtue in the eye of the beholder? The case of ESG ratings. Account. Rev. 2022, 97, 147–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Nezlobin, A. Information disclosure, firm growth, and the cost of capital. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 123, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Strategic responses to institutional processes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 145–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M.; El Ghoul, S.; Gomes, M. Greenwashing and product market competition. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 42, 101927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lan, H. Dynamics of public opinion: Diverse media and audiences’ choices. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul. 2021, 24, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Lyon, T.P. Greenwash vs. brownwash: Exaggeration and undue modesty in corporate sustainability disclosure. Organ. Sci. 2015, 26, 705–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Francoeur, C.; Brammer, S. What drives and curbs brownwashing? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2022, 31, 2518–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Van Luu, B.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, M.P.; Vincent, J.D. Professional investor relations within the firm. Account. Rev. 2014, 89, 1421–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Huang, M.; Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Ning, L. Environmental legitimacy, green innovation, and corporate carbon disclosure: Evidence from CDP China 100. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 1089–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Toffel, M.W.; Zhou, Y. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher-Vanden, K.; Thorburn, K.S. Voluntary corporate environmental initiatives and shareholder wealth. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 62, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, A.; Lyon, T.P.; Martin, S. Salience games: Private politics when public attention is limited. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 88, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, Y.M.; Yang, S.L. Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance-like effects? Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of environmental practices and institutional complexity: Can stakeholders pressures encourage greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Su, K. Economic policy uncertainty and corporate financialization: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Xu, Y.; Yu, L.; Qiu, R. Sustainability needs trust: The role of social trust in driving corporate ESG performance. Econ. Anal. Policy. 2025, 86, 1492–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Quilice, T.; Hernández-Maestro, R.M.; Duarte, R.G. Corporate sustainability transitions: Are there differences between what companies say and do and what ESG ratings say companies do? J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 414, 137520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, P.S.; Joshi, M.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A.; Phan, D. Greenwashing and ESG: Bibliometric analysis and future research agenda. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2025, 93, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Matousek, R.; Meyer, M.; Tzeremes, N.G. Does corporate social responsibility impact firms’ innovation capacity? The indirect link between environmental & social governance implementation and innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaya, A.J.; Saleh, N.M. The moderating effect of IR framework adoption on the relationship between environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure and a firm’s competitive advantage. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 2037–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, U.; Hirshleifer, D. Opportunism as a firm and managerial trait: Predicting insider trading profits and misconduct. J. Financ. Econ. 2017, 126, 490–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A.; Gabaix, X. Executive compensation: A modern primer. J. Econ. Lit. 2016, 54, 1232–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E.F. Agency problems and the theory of the firm. J. Political Econ. 1980, 88, 288–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, N.S.; Mohebshahedin, M.; Tripathy, A.K.; Mahajan, A.; Gupta, A.K. On the relevance of mandatory executive pay ratio disclosure: Evidence from India. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 196, 115401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, E.J.; Campbell, D.T.; Schwartz, R.D.; Sechrest, L. Unobtrusive Measures: Nonreactive Research in the Social Sciences; Rand McNally: Chicago, IL, USA, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.T.; Ross, M. Self-serving biases in the attribution of causality: Fact or fiction? Psychol. Bull. 1975, 82, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Mehl, M.R.; Niederhoffer, K.G. Psychological aspects of natural language use: Our words, our selves. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003, 54, 547–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nadkarni, S. It’s about time! CEOs’ temporal dispositions, temporal leadership, and corporate entrepreneurship. Adm. Sci. Q. 2017, 62, 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varas, F. Managerial short-termism, turnover policy, and the dynamics of incentives. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2018, 31, 3409–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chung, J. Women in top management teams and their impact on innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 183, 121883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.S.; Carter, M.Z.; Zhang, Z. Leader–team congruence in power distance values and team effectiveness: The mediating role of procedural justice climate. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, S. Corporate social responsibility, product market competition, and firm value. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 98, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Harvey, C.R.; Rajgopal, S. The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. J. Account. Econ. 2005, 40, 3–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C.; Bansal, P. Does a long-term orientation create value? Evidence from a regression discontinuity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1827–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, F.A.; Chen, C.J.; Tsui, J.S. Discretionary accounting accruals, managers’ incentives, and audit fees. Contemp. Account. Res. 2003, 20, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubaker, S.; Saffar, W.; Sassi, S. Product market competition and debt choice. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 49, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Petit, A. The weighting of CSR dimensions: One size does not fit all. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 919–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L.C.; Carcello, J.V.; Li, C.; Neal, T.L.; Francis, J.R. Impact of auditor report changes on financial reporting quality and audit costs: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 1501–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Cho, S.Y.; Arthurs, J.; Lee, E.K. CEO pay inequity, CEO-TMT pay gap, and acquisition premiums. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wan, S.; Zhou, Y. Executive compensation, internal governance and ESG performance. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Judge, W.Q.; Li, Y.H. Voluntary disclosure, excess executive compensation, and firm value. J. Corp. Financ. 2015, 32, 64–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochet, F.; Loumioti, M.; Serafeim, G. Speaking of the short-term: Disclosure horizon and managerial myopia. Rev. Account. Stud. 2015, 20, 1122–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Shivakumar, L. The role of accruals in asymmetrically timely gain and loss recognition. J. Account. Res. 2006, 44, 207–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, L.; Li, X. Why Do ESG Rating Differences Affect Audit Fees?—Dual Intermediary Path Analysis Based on Operating Risk and Analyst Earnings Forecast Error. Sustainability 2025, 17, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gul, F.A.; Veeraraghavan, M.; Zolotoy, L. Executive equity risk-taking incentives and audit pricing. Account. Rev. 2015, 90, 2205–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghamolla, C.; Hashimoto, T. Managerial myopia, earnings guidance, and investment. Contemp. Account. Res. 2023, 40, 166–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Code | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | ||

| Abnormal Audit Fees | ABAUFE | The difference between actual and normal audit fees; see Equations (2) and (3) for calculation. |

| Independent Variable | ||

| ESG Washing | ESGW | The industry-standardized difference between ESG disclosure and ESG performance; see Equation (1) for calculation. |

| Mediating Variables | ||

| Excess Executive Compensation | EXPAY | The difference between the actual total compensation of the top three executives and the expected compensation; see Equations (4) and (5) |

| Executive Myopia | MSSB | Constructed following Brochet et al. (2015) [71] and Schuster et al. (2024) [8], using data from the WinGo Financial Text Data Platform. |

| Moderating Variable | ||

| Market Structure | MAST | The proportion of total industry revenue accounted for by the top four firms in the industry. |

| Control Variables | ||

| Executive Shareholding Ratio | EXSH | The proportion of shares held by executives relative to the firm’s total outstanding shares |

| Return on Assets | ROA | =Net profit ÷ average total assets |

| Gross Profit Margin | GPM | =(Total operating revenue—total operating cost) ÷ total operating revenue |

| Financing Constraints | FICO | =Total assets ÷ total liabilities |

| Asset Turnover | ASTU | =Total operating revenue ÷ average total assets |

| Firm Size | SIZE | =ln(total assets) |

| Ownership Nature | NPR | = |

| Shareholding Balance | SHBA | The sum of the shareholding ratios of the 2nd to 5th largest shareholders divided by that of the largest shareholder |

| Employee Intensity | EMIN | =Number of employees ÷ total operating revenue (in million RMB) |

| Book-to-Market Ratio | B/M | =Shareholders’ equity ÷ company market value |

| Accounting Conservatism | ACRO | Incremental sensitivity of accruals to negative operating cash flows relative to positive cash flows; ACRO > 0 indicates accounting conservatism. (The accounting conservatism coefficient (ACRO) is calculated following the ACF model developed by Ball and Shivakumar [72] (2006), using regressions by industry and year in the CSMAR database. The regression model is specified as: , where ACC represents total accruals, CFO is net cash flow from operating activities, and DR equals 1 if CFO < 0, and 0 otherwise. The coefficient is the accounting conservatism coefficient (ACRO).). |

| Year | Year | Year dummy variable |

| Industry | Ind | Industry dummy variable |

| Main Variables | N | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABAUFE | 9400 | 0 | 0.0170 | 0.7833 | −16.09 | 3.55 |

| ESGW | 9400 | 0.3911 | 0.3187 | 1.2305 | −3.86 | 4.19 |

| EXPAY | 9400 | 0.0497 | 0.0729 | 0.7594 | −1.91 | 1.82 |

| MSSB | 9400 | 0.0824 | 0.0661 | 0.0710 | 0 | 0.855 |

| MAST | 9400 | 0.4549 | 0.4451 | 0.1959 | 0 | 1 |

| EXSH | 9400 | 4.901 | 0.0208 | 11.631 | 0 | 79.07 |

| ROA | 9400 | 0.0426 | 0.0364 | 0.0758 | −1.68 | 0.96 |

| GMP | 9400 | 0.2708 | 0.2339 | 0.1870 | −1.62 | 1.15 |

| FICO | 9400 | 0.4859 | 0.4965 | 0.2014 | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| ASTU | 9400 | 0.6725 | 0.5577 | 0.5433 | 0.01 | 7.79 |

| SIZE | 9400 | 23.4539 | 23.34 | 1.3477 | 18.32 | 28.70 |

| NPR | 9400 | 0.55 | 1 | 0.497 | 0 | 1 |

| SHBA | 9400 | 0.6640 | 0.4799 | 0.5808 | 0 | 3.62 |

| EMIN | 9400 | 1.0085 | 0.7531 | 1.1629 | 0.01 | 53.01 |

| B/M | 9400 | 0.6616 | 0.6542 | 0.3040 | 0.03 | 1.64 |

| ACRO | 9400 | −0.6926 | −0.6144 | 0.9589 | −7.40 | 18.26 |

| Variables | (1) ABAUFE | (2) EXPAY | (3) MSSB | (4) ABAUFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW | 0.0196 *** (0.007) | 0.0513 *** (0.005) | −0.0033 *** (0.001) | 0.0165 ** (0.007) |

| EXPAY | −0.0058 *** (0.001) | 0.0408 *** (0.013) | ||

| MSSB | −0.2726 ** (0.115) | |||

| EXSH | −0.0028 *** (0.001) | −0.0052 *** (0.001) | −0.0003 *** (0.0001) | −0.0026 *** (0.001) |

| ROA | −2.5960 *** (0.673) | 8.2126 *** (0.535) | −0.5699 *** (0.061) | −3.0995 *** (0.684) |

| GPM | −0.0717 (0.057) | 0.7062 *** (0.045) | −0.0261 *** (0.005) | −0.1087 (0.058) |

| FICO | −0.0921 (0.056) | 0.5612 *** (0.444) | 0.0035 (0.005) | −0.1150 ** (0.056) |

| ASTU | 0.0968 *** (0.017) | 0.2095 *** (0.013) | −0.0075 *** (0.002) | 0.0859 *** (0.017) |

| SIZE | 0.0238 *** (0.008) | −0.1516 *** (0.007) | −0.0048 *** (0.001) | 0.0289 *** (0.009) |

| NPR | −0.2280 *** (0.019) | −0.4908 *** (0.015) | 0.0111 *** (0.002) | −0.2041 *** (0.020) |

| SHBA | 0.0845 *** (0.014) | 0.1442 *** (0.011) | −0.0028 ** (0.001) | 0.0776 *** (0.014) |

| EMIN | 0.0338 *** (0.007) | −0.0299 *** (0.006) | 0.0035 *** (0.001) | 0.0361 *** (0.007) |

| B/M | −0.1195 *** (0.036) | −0.3850 *** (0.029) | 0.0160 *** (0.003) | −0.0988 *** (0.037) |

| ACRO | 0.0196 ** (0.008) | 0.0291 *** (0.007) | −0.0022 *** (0.001) | 0.0178 ** (0.008) |

| cons | −0.4152 ** (0.176) | 3.5841 *** (0.140) | 0.1812 *** (0.016) | −0.5177 *** (0.184) |

| Year | Yse | Yse | Yse | Yse |

| Ind | Yse | Yse | Yse | Yse |

| n | 9400 | 9400 | 9400 | 9400 |

| 3.90% | 35.48% | 6.30% | 4.07% | |

| F | 29.33 *** | 396.97 *** | 45.10 *** | 26.55 *** |

| Effect Type | Path | Effect Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ESGW→ABAUFE | 0.0165 ** | 0.001 | 0.0036 | 0.0295 |

| Indirect Effect | ESGW→EXPAY→ABAUFE | 0.0021 *** | 0.001 | 0.0010 | 0.0033 |

| ESGW→MSSB→ABAUFE | 0.0009 *** | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0019 | |

| Chain Mediating Effect | ESGW→EXPAY→MSSB→ABAUFE | 0.0001 *** | 0.000 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Total Effect | ESGW→ABAUFE | 0.0196 *** | 0.007 | 0.0067 | 0.0325 |

| Variable | (2) EXPAY | (3) MSSB | (5) ABAUFE |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW | 0.0513 *** (0.005) | −0.0036 *** (0.001) | 0.0184 *** (0.007) |

| EXPAY | 0.1188 *** (0.028) | ||

| MSSB | 1.2149 *** (0.312) | ||

| MAST | 0.5748 *** (0.065) | ||

| EXPAY×MAST | −0.1353 *** (0.053) | ||

| MSSB×MAST | −3.1552 *** (0.611) | ||

| EXSH | −0.0052 *** (0.001) | −0.0002 *** (0.000) | −0.0023 *** (0.001) |

| ROA | 8.2126 *** (0.535) | −0.6177 *** (0.060) | −2.5172 *** (0.686) |

| GPM | 0.7062 *** (0.045) | −0.0302 *** (0.005) | −0.0515 (0.058) |

| FICO | 0.5612 *** (0.044) | 0.0002 (0.005) | −0.0925 (0.056) |

| ASTU | 0.2095 *** (0.013) | −0.0087 *** (0.002) | 0.0845 *** (0.017) |

| SIZE | −0.1516 *** (0.007) | −0.0039 *** (0.001) | 0.0196 ** (0.009) |

| NPR | −0.4908 *** (0.015) | 0.0139 *** (0.002) | −0.2095 *** (0.020) |

| SHBA | 0.1442 *** (0.011) | −0.0037 *** (0.001) | 0.0801 *** (0.014) |

| EMIN | −0.0299 *** (0.006) | 0.0037 *** (0.001) | 0.0302 *** (0.008) |

| B/M | −0.3850 *** (0.029) | 0.0183 *** (0.003) | −0.0898** (0.037) |

| ACRO | 0.0291 *** (0.007) | −0.0023 *** (0.001) | 0.0164 ** (0.008) |

| Year | Yse | Yse | Yse |

| Ind | Yse | Yse | Yse |

| cons | 3.5841 *** (0.140) | 0.1604 *** (0.016) | −0.5836 *** (0.187) |

| n | 9400 | 9400 | 9400 |

| 35.48% | 6.05% | 4.96% | |

| F | 396.97 *** | 46.53 *** | 27.17 *** |

| Path | Index Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW→EXPAY→ABAUFE | −0.0069 *** | 0.003 | −0.0123 | −0.0018 |

| ESGW→MSSB→ABAUFE | 0.0112 *** | 0.003 | 0.0056 | 0.0183 |

| Path | MAST | Effect Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW→EXPAY→ABAUFE | +1SD | 0.0016 *** | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 |

| Mean | 0.0029 *** | 0.001 | 0.0018 | 0.0042 | |

| −1SD | 0.0043 *** | 0.001 | 0.0028 | 0.0059 | |

| ESGW→MSSB→ABAUFE | +1SD | 0.0030 *** | 0.001 | 0.0015 | 0.0050 |

| Mean | 0.0008 *** | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0018 | |

| −1SD | −0.0014 *** | 0.001 | −0.0028 | 0.0002 |

| Variables | (1) EXPAY | (2) MSSB | (3) ABAUFE | (4) ABAUFEt+1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW | 0.0196 *** (0.007) | |||

| ESGWt−1 | 0.0531 *** (0.006) | −0.0038 *** (0.001) | 0.0212 *** (0.007) | |

| EXPAY | −0.0045 *** (0.001) | 0.0397 *** (0.013) | 0.1077 *** (0.028) | |

| MSSB | −0.2028 ** (0.119) | 1.0513 *** (0.308) | ||

| MAST | 0.5123 *** (0.065) | |||

| EXPAY × MAST | −0.1346 ** (0.053) | |||

| MSSB × MAST | −2.4829 *** (0.601) | |||

| Year | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ind | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| cons | 3.6842 *** (0.148) | 0.1654 *** (0.017) | −0.3866 ** (0.185) | −0.5897 *** (0.188) |

| n | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 | 8460 |

| 35.98% | 5.85% | 4.62% | 5.79% | |

| F | 365.07 *** | 37.50 *** | 27.28 *** | 28.81 *** |

| Path | Index Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW→EXPAY→ABAUFEt+1 | −0.0074 *** | 0.003 | −0.0133 | −0.0015 |

| ESGW→MSSB→ABAUFEt+1 | 0.0092 *** | 0.003 | 0.0048 | 0.0150 |

| Path | Market Structure (MAST) | Effect Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESGW→EXPAY→ABAUFEt+1 | +1SD | 0.0011 | 0.001 | −0.0007 | 0.0029 |

| Mean | 0.0025 *** | 0.001 | 0.0014 | 0.0038 | |

| −1SD | 0.0040 *** | 0.001 | 0.0025 | 0.0056 | |

| ESGW→MSSB→ABAUFEt+1 | +1SD | 0.0021 *** | 0.001 | 0.0011 | 0.0034 |

| Mean | 0.0003 | 0.001 | −0.0003 | 0.0010 | |

| −1SD | −0.0015 *** | 0.001 | −0.0029 | −0.0003 |

| Effect Type | Path | Effect Value | Std. Error | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ESGWt−1→ABAUFE | 0.0212 ** | 0.001 | 0.0080 | 0.0344 |

| Indirect Effect | ESGWt−1→EXPAY→ABAUFE | 0.0021 *** | 0.001 | 0.0009 | 0.0034 |

| ESGWt−1→MSSB→ABAUFE | 0.0008 *** | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0017 | |

| Chain Mediating Effect | ESGWt−1→EXPAY→MSSB→ABAUFE | 0.0001 *** | 0.000 | 0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Total Effect | ESGWt−1→ABAUFE | 0.0242 *** | 0.001 | 0.0110 | 0.0373 |

| Variables | Managerial Tone | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Tone | Positive Tone | |

| ESGW | 0.025 *** (3.02) | 0.015 ** (1.97) |

| cons | −0.4152 ** (0.176) | 3.5841 *** (0.140) |

| Controls | Yse | Yse |

| Year | Yse | Yse |

| Ind | Yse | Yse |

| n | 4700 | 4700 |

| 15.4% | 14.1% | |

| F | 7.32 *** | 6.72 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, X.; Yao, Y.; Han, J. Does ESG Washing Increase Abnormal Audit Fees? Research Based on the Chain Mediating Effects. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219668

Sun X, Yao Y, Han J. Does ESG Washing Increase Abnormal Audit Fees? Research Based on the Chain Mediating Effects. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219668

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Xiaoyan, Yuan Yao, and Jie Han. 2025. "Does ESG Washing Increase Abnormal Audit Fees? Research Based on the Chain Mediating Effects" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219668

APA StyleSun, X., Yao, Y., & Han, J. (2025). Does ESG Washing Increase Abnormal Audit Fees? Research Based on the Chain Mediating Effects. Sustainability, 17(21), 9668. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219668