Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations

Abstract

1. Introduction

Modern Approaches to Sustainable Development in the Context of Salutogenesis

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identifying the Impact of Interior Building Features on Physical and Mental Health

2.1.1. Indoor Air Quality (IAQ)

2.1.2. Natural and Artificial Lighting

2.1.3. Interior Acoustics (Noise and Acoustic Comfort)

2.1.4. Interior Aesthetics and Color Design

2.1.5. Ergonomics and Spatial Layout

2.1.6. Spatial Layout and Interior Organization

2.2. Identification of Salutogenic Design Factors

- F1

- Access to nature and restorative environments,

- F2

- Access to daylight,

- F3

- Thermal comfort and air quality,

- F4

- Space for social support,

- F5

- Control over the environment and a sense of privacy,

- F6

- Acoustic comfort,

- F7

- Sensory stimulation,

- F8

- Spatial legibility and navigation,

- F9

- Diversity and encouragement of physical activity,

- F10

- Sense of identity and meaning of place.

2.3. Analysis of Legal Regulations and Industry Guidelines

3. Results

3.1. The Impact of Building Interior Features on Physical and Mental Health

3.1.1. Case Studies and Post-Occupancy Evaluations (POE)

3.1.2. Results of Empirical Research Published in 2015–2025

3.2. Comparison of Legal Requirements and Salutogenic Design Factors

- (a)

- is strictly required by national legislation (or normative acts with legal force),

- (b)

- is recommended or indirectly required by industry standards,

- (c)

- is not present in any official legal or professional requirements.

3.3. Identification of Gaps and Opportunities for Improvement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Domaradzki, J. O skrytości zdrowia. O problemach z koncepcją zdrowia. Hygeia Public Health 2015, 50, 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 1946. Available online: https://www.globalhealthrights.org/instrument/constitution-of-the-world-health-organization-who/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Jadczyk, M. Zdrowie Jako Kategoria Filozoficzna i Pedagogiczna; Oficyna Wydawnicza Uniwersytetu Zielonogórskiego Publishing: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: A systematic review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Golembiewski, J.A. Salutogenic Architecture in Healthcare Settings. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis; Mittelmark, M.B., Sagy, S., Eriksson, M., Bauer, G.F., Pelikan, J.M., Lindström, B., Espnes, G.A., Eds.; Springer Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Dilani, A. Psychosocially Supportive Design: A Salutogenic Approach to the Design of the Physical Environment. Des. Health Sci. Rev. 2008, 1, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Izadpanah, S.; Majedi, H.; Zabihi, H. Wprowadzenie zmiennych architektonicznych zdrowych szkół, zgodnych z teorią salutogeniczną w poprawie jakości umysłowej uczennic szkół średnich w mieście Gorgan. J. Conserv. Archit. Iran 2024, 14, 103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, T.; Zhang, G.; Sun, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, T.; Duan, H. Effects of Indoor Air Quality on Human Physiological Impact: A Review. Buildings. 2025, 15, 1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagare, R.; Woo, M.; MacNaughton, P.; Plitnick, B.; Tinianov, B.; Figueiro, M. Access to Daylight at Home Improves Circadian Alignment, Sleep, and Mental Health in Healthy Adults: A Crossover Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landvreugd, A.; Nivard, M.G.; Bartels, M. The Effect of Light on Wellbeing: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Happiness Stud. 2025, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Q.; Kang, J. Influence of the Acoustic Environment in Hospital Wards on Patient Physiological and Psychological Indices. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, E.J.; Marques, C.; Birt, J.; Stead, M.; Baumann, O. Open-Plan Office Noise Is Stressful: Multimodal Stress Detection in a Simulated Work Environment. J. Manag. Organization. 2021, 27, 1358–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, Y. Effects of Postural Changes Using a Standing Desk on the Craniovertebral Angle, Muscle Fatigue, Work Performance, and Discomfort in Individuals with Forward Head Posture. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, T. Color in Health Care: How Mindful Design Can Improve Clinical Spaces. Psychiatry Advisor. 2024. Available online: https://www.psychiatryadvisor.com/features/color-in-health-care-design-spaces/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Dawood, S. Filling Hospitals with Art Reduces Patient Stress, Anxiety and Pain. 2019. Available online: https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/22-28-july-2019/chelsea-westminster-hospital-arts-research// (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ustawa z Dnia 7 Lipca 1994 r.–Prawo Budowlane (Tekst Jednolity: Dz.U. 2023 poz. 682 z późn. zm.). 2023. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20230000682 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Infrastruktury z dnia 12 Kwietnia 2002 r. w Sprawie Warunków Technicznych, Jakim Powinny Odpowiadać Budynki I Ich Usytuowanie (Tekst Jednolity: Dz.U. 2022 poz. 1225 z późn. zm.). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20220001225 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- International WELL Building Institute (IWBI). WELL Building Standard v2. IWBI: Nowy Jork. 2020. Available online: https://www.wellcertified.com/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S.; Simons, R.F.; Losito, B.D.; Fiorito, E.; Miles, M.A.; Zelson, M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol. 1991, 11, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berto, R. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. Effect of forest bathing trips on human immune function. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.U.; James, L.M.; Archer, S.N.; Dijk, D.J. Blue-enriched white light in the workplace improves self-reported alertness, performance and sleep quality. Scandinavian. J. Work. Environ. Health 2008, 34, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.B.; Smallman, H.S.; Lacson, F.C.; Manes, D.I. Situation displays for dynamic UAV replanning: Intuitions and performance for display formats. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2010, 54, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiro, M.G.; Plitnick, B.; Lok, A.; Steverson, B. Tailored lighting intervention improves sleep and mood in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Sleep Health 2017, 3, 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, C.A. Perspective: Casting light on sleep deficiency. Nature 2013, 497, S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P.; Sundell, J.; Clausen, G.; Fanger, P.O. The effects of outdoor air supply rate in an office on perceived air quality, sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms and productivity. Indoor Air 2000, 10, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Kim, D.; Buchberger, E.; Bauman, F.; Huizenga, C. Comfort, perceived air quality, and work performance in a low-power task–ambient conditioning system. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontczak, M.; Wargocki, P. Literature survey on how different factors influence human comfort in indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2011, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W. The built environment and mental health. J. Urban Health 2003, 80, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kaplan, R. Physical and psychological factors in sense of community: New urbanist Kentlands and nearby Orchard Village. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, B.-S.; Sullivan, W.C.; Wiley, A.R. Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environ. Behav. 1998, 30, 832–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, I. The Environment and Social Behavior: Privacy, Personal Space, Territory, Crowding; Brooks/Cole Publishing: Monterey, CA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, G.W.; Wener, R.E. Crowding and personal space invasion on the train: Please don’t make me sit in the middle. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, E. Privacy protection in a behavioral world. J. Soc. Issues 1978, 34, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calhoun, J.B. Gęstość zaludnienia i patologia społeczna. Sci. Am. 1962, 206, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haapakangas, A.; Hongisto, V.; Varjo, J.; Lahtinen, M. Benefits of quiet workspaces in open-plan offices–Evidence from two office relocations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burry, M. Wrażenie Barwne–Wpływ Kolorów Na Ruch I Emocje. In Konsekwencje Pracy Nad Świadomością Ciała: Podejścia, Doświadczenia, Praktyki; Tatar, M., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego Publishing: Katowice, Poland, 2020; pp. 114–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ziat, M.; Balcer, C.A.; Shirtz, A.; Rolison, T. The hue-heat hypothesis: Does color truly affect temperature perception? Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Art Therapy and Health Care; Guilford Press Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carpman, J.R.; Grant, M.A. Design That Cares: Planning Health Facilities for Patients and Visitors; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press Publishing: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Passini, R. Wayfinding design: Logic, application and some thoughts on universality. Des. Stud. 1996, 17, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpman, J.R.; Grant, M.A. Design That Cares: Planning Health Facilities for Patients and Visitors, 3rd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Frumkin, H.; Bratman, G.N.; Breslow, S.J.; Cochran, B.; Kahn, P.H.; Lawler, J.J.; Levin, P.S.; Tandon, P.S.; Varanasi, U.; Wolf, K.L.; et al. Nature contact and human health: A research agenda. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 075001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengen, C.; Kistemann, T. Sense of place and place identity: Review of neuroscience evidence. Health Place 2012, 18, 1162–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C. For better or worse: Exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, R.J.; Valdebenito, M.J. The importation of building environmental certification systems: International usages of LEED. Build. Res. Inf. 2013, 41, 662–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhao, Z.Y. Green building research–current status and future agenda: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mfon, I.E. Aesthetic considerations in architectural design: Exploring pleasure, arousal, and dominance. Int. J. Res. Publ. Rev. 2023, 4, 923–935. [Google Scholar]

- Rezafar, A.; Turk, S.S. Czynniki urbanistyczne wpływające na ocenę estetyczną nowo wybudowanych środowisk i ich uwzględnienie w ustawodawstwie: Przykład Stambułu. Urbani Izziv 2018, 29, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartanian, O.; Navarrete, G.; Chatterjee, A.; Fich, L.B.; Leder, H.; Modroño, C.; Skov, M. Wpływ konturu na osądy estetyczne i decyzje o podejściu lub unikaniu w architekturze. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110 (Suppl. S2), 10446–10453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, A.M. The interior as interiority: Architecture, affect, and the aesthetics of experience. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.; Moore, S.; Thompson-Lake, D.; Salih, S.; Beck, B. Atrakcyjność estetyczna percepcji synestetycznych słuchowo-wzrokowych u osób bez synestezji. Perception 2008, 37, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Environment and Health Risks: A Review of the Influence and Effects of Social Inequalities. WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2010. Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/ca617634-4487-40f0-a5b9-7babeb66bc82/content (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Deuble, M.P.; de Dear, R.J. Czy tu jest gorąco, czy tylko ja tak mam? Walidacja oceny poeksploatacyjnej. Intell. Build. Int. 2014, 6, 112–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T.; Korpela, K.; Evans, G.W.; Gärling, T. A measure of restorative quality in environments. Scand. Hous. Plan. Research. 1997, 14, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagowska, B. Wyniki Badań i Oceny Hałasu, Oświetlenia i Mikroklimatu na Wybranych Stanowiskach Pracy. Cent. Inst. Ochr. Pr.–Państwowy Inst. Badaw. (CIOP-PIB). 2018. Available online: https://m.ciop.pl/CIOPPortalWAR/file/91827/NA_hlalas_oswietlenie_mikroklimat_na_wybranych_stanowiskach_pracy_wyniki_badan.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Carpman, J.R.; Grant, M.A. Design That Cares: Planning Health Facilities for Patients and Visitors, 2nd ed.; American Hospital: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Joarder, M.A.R.; Price, A.D.F.; Mourshed, M. Systematic Study of the Therapeutic Impact of Daylight Associated with Clinical Recovery. In Proceedings of the PhD Workshop of HaCIRIC’s International Conference 2009: Improving Healthcare Infrastructures Through Innovation, HaCIRIC, Brighton, UK, 2 April 2009; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Uścinowicz, P.; Bogdan, A.; Szyłak-Szydłowski, M.; Młynarczyk, M.; Ćwiklińska, D. Subjective assessment of indoor air quality and thermal environment in patient rooms: A survey study of Polish hospitals. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szuba, A.; Martynowicz, H.; Zatońska, K.; Iłów, R.; Regulska-Iłów, B.; Różańska, D.; Zatoński, W. Częstość występowania nadciśnienia tętniczego w populacji polskiej badania PURE Poland. J. Health Inequalities 2017, 2, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czałczyńska-Podolska, M.; Rzeszotarska-Pałka, M. Ogród szpitalny jako miejsce terapii i rekonwalescencji. Kosmos. Probl. Nauk. Biol. 2016, 65, 609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, C.; Higgs, J.; McCray, S.; Utter, J. Implementation and Impact of Health Care Gardens. J. Integr. Med. 2024, 30, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RESTORE COST Action CA16114. Rethinking Sustainability Towards a Regenerative Economy: Report on Regenerative Design and Assessment; European Cooperation in Science and Technology: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://www.eurestore.eu (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Ildiri, N.; Bazille, H.; Lou, Y.; Hinkelman, K.; Gray, W.A.; Zuo, W. Impact of WELL certification on occupant satisfaction and perceived health, well-being, and productivity: A multi-office pre-versus post-occupancy evaluation. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzban, S.; Candido, C.; Avazpour, B.; Mackey, M.; Zhang, F. The potential of high-performance workplaces for boosting worker productivity, health, and creativity: A comparison between WELL and non-WELL certified environments. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

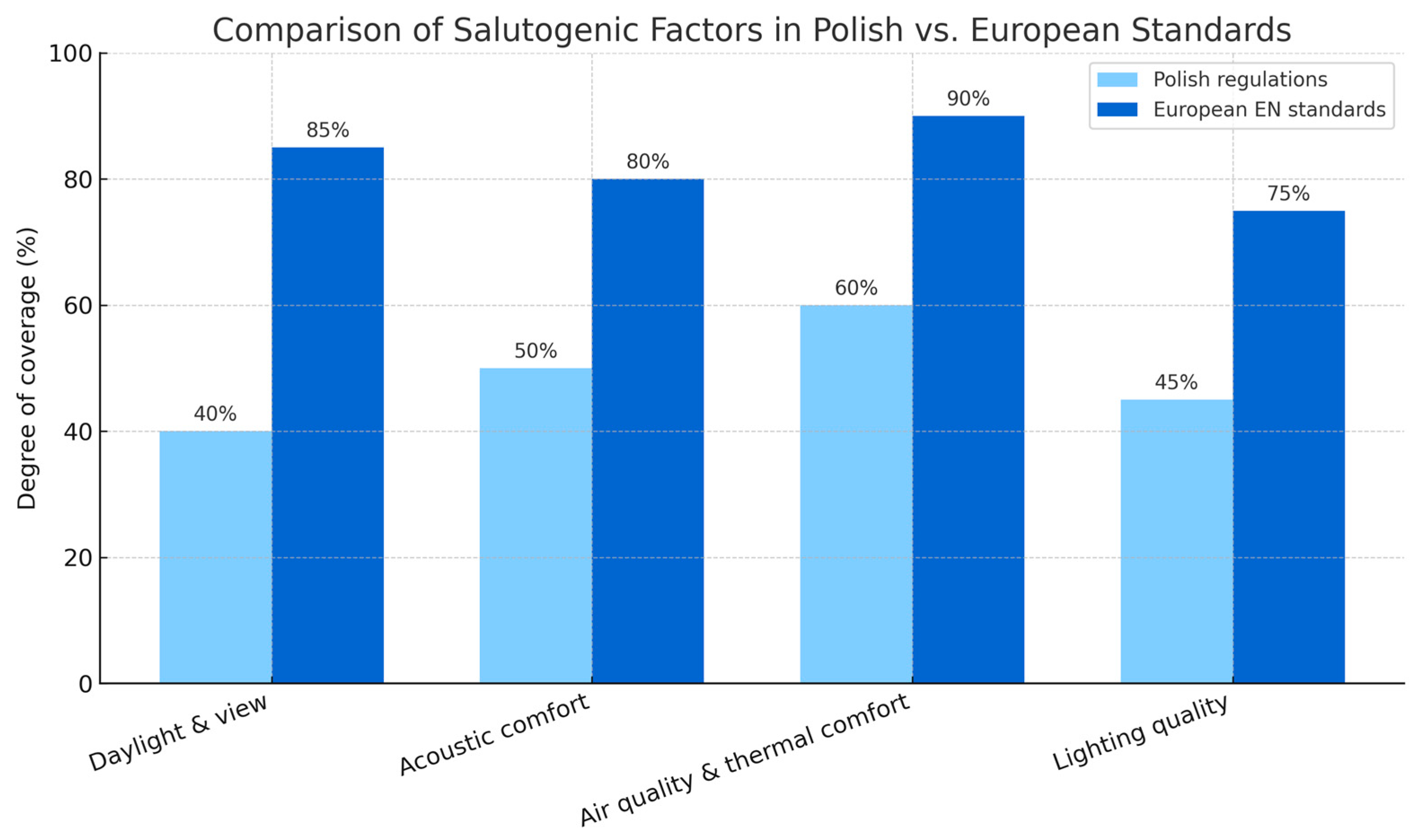

- EN 17037:2018; Daylight in Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings–Ventilation for Buildings–Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN ISO 3382-1:2009; Acoustics–Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters–Part 1: Performance Spaces. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- EN ISO 3382-2:2008; Acoustics–Measurement of Room Acoustic Parameters–Part 2: Reverberation Time in Ordinary Rooms. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

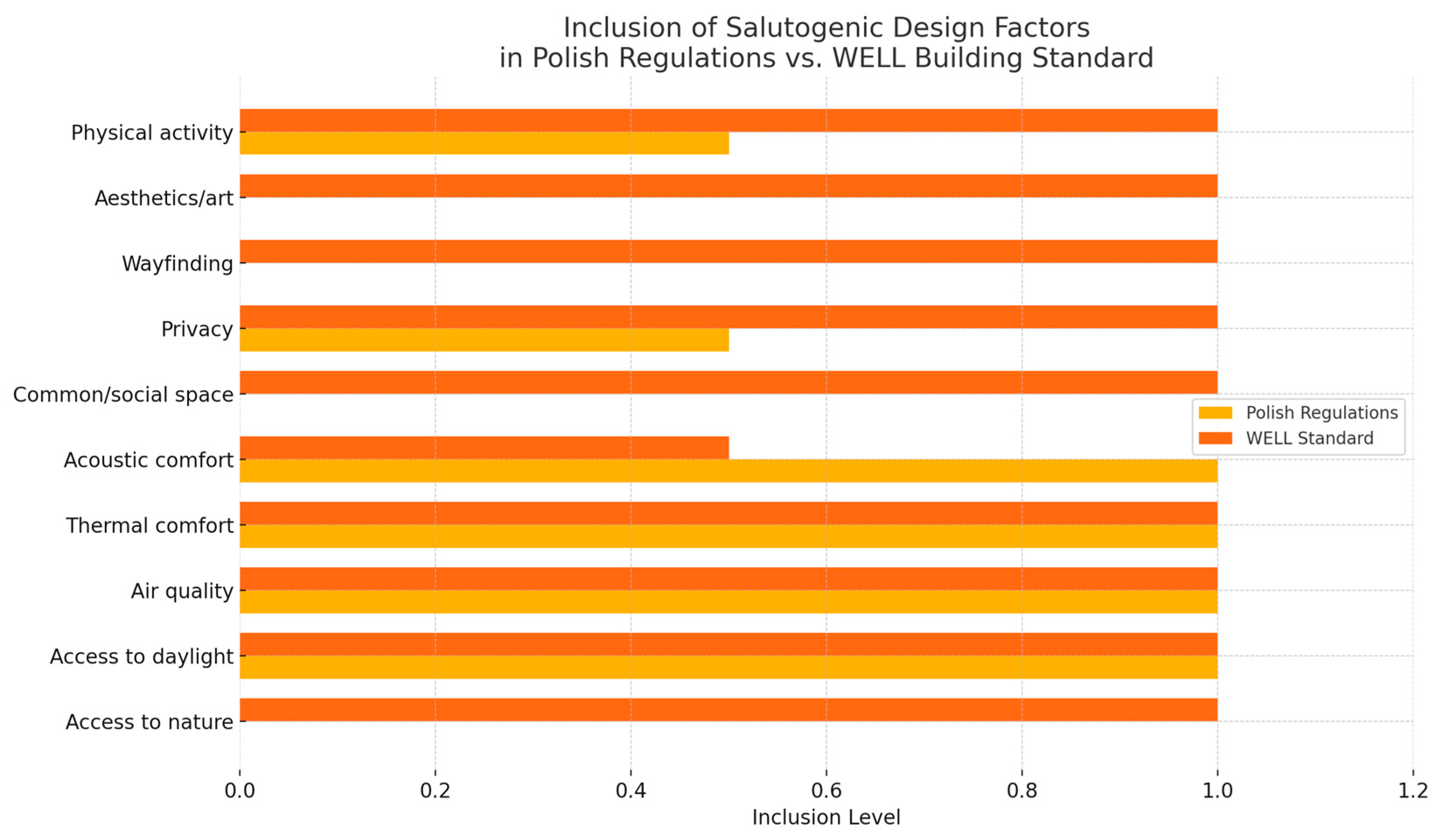

| No. | Salutogenic Factors | Inclusion in Polish Mandatory Regulations (Construction Law, Technical Conditions) | Inclusion in Industry Standards (e.g., WELL Building Standard) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Access to nature and restorative environments | No—direct requirements (there is no obligation to have internal greenery or a view to the outside, apart from the standards regarding plot sunlight). | Yes—the standards recommend biophilic elements (e.g., WELL Feature Biophilia). |

| 2 | Access to daylight | Yes—requirement for daylighting of rooms intended for people (condition: minimum window area and sunlight). | Yes—emphasis placed on access to daylight (WELL Light category) |

| 3 | Air quality | Yes—mandatory requirements regarding natural or mechanical ventilation, pollution limits (CO2, other) in rooms. | Yes—very strongly emphasized (WELL Air category—air quality control, filtration, etc.). |

| 4 | Thermal comfort | Yes—requirements regarding thermal insulation and heating; minimum temperature in utility rooms (e.g., 20 °C) specified in the regulations. | Yes—recommendations regarding thermal comfort (WELL Thermal Comfort—compliance with comfort standards). |

| 5 | Acoustic comfort | Yes—standards for acoustic insulation of partitions and permissible noise levels in residential and public buildings. | Partially—the standards recommend good acoustics (e.g., WELL Sound), although not always obligatory. |

| 6 | Common and social space | No—the regulations do not require the creation of additional integration spaces (apart from, for example, the requirement for a common room in boarding schools or a playground in larger housing estates). | Yes—WELL and other recommendations promote recreational spaces and common areas for users (impact on the Community). |

| 7 | Possibility of privacy, avoiding crowds | Partially—indirectly through the standards of minimum living space per person (e.g., at least 8 m2 per person in a living room), but the lack of regulations regarding the subjective sense of privacy. | Yes—the standards suggest designing taking into account various zones (public, semi-private, private) for the comfort of users. |

| 8 | Readability of orientation (wayfinding) | No—apart from the requirements regarding marking escape routes, there are no regulations regarding orientation facilities (e.g., there is no requirement for “landmarks”). | Yes—good layout design and space marking recommended (e.g., Design for mind in WELL). |

| 9 | Aesthetics, colors, art | No—aesthetic and color issues are not subject to legal standards (except, for example, safety colors for occupational health and safety markings). | Yes—e.g., WELL in the Mind category encourages you to include art, biophilic design, and elements that improve the mood of user. |

| 10 | Physical activity and movement | Partially—the regulations require infrastructure for activities only in specific cases (e.g., playgrounds at schools). Generally, there is no requirement, e.g., to encourage the use of stairs. | Yes—the standards (WELL Fitness) promote solutions that encourage exercise: availability of stairs, physical activity zones in buildings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rek-Lipczyńska, A. Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219661

Rek-Lipczyńska A. Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219661

Chicago/Turabian StyleRek-Lipczyńska, Agnieszka. 2025. "Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219661

APA StyleRek-Lipczyńska, A. (2025). Salutogenic Factors and Sustainable Development Criteria in Architectural and Interior Design: Analysis of Polish and EU Standards and Recommendations. Sustainability, 17(21), 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219661