What Do We Focus on? Investigating Chinese Public Preferences for CSR Initiatives in Professional Sports Clubs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Theoretical Foundations of CSR Preferences

2.2. Research Progress on Public Preferences for CSR

2.3. Analytical Framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Levels of Different Attributes of Corporate Social Responsibility in Professional Sports Clubs

3.2. Joint Experimental Design and Procedure

3.3. Data Collection and Sample Description

4. Data Analysis

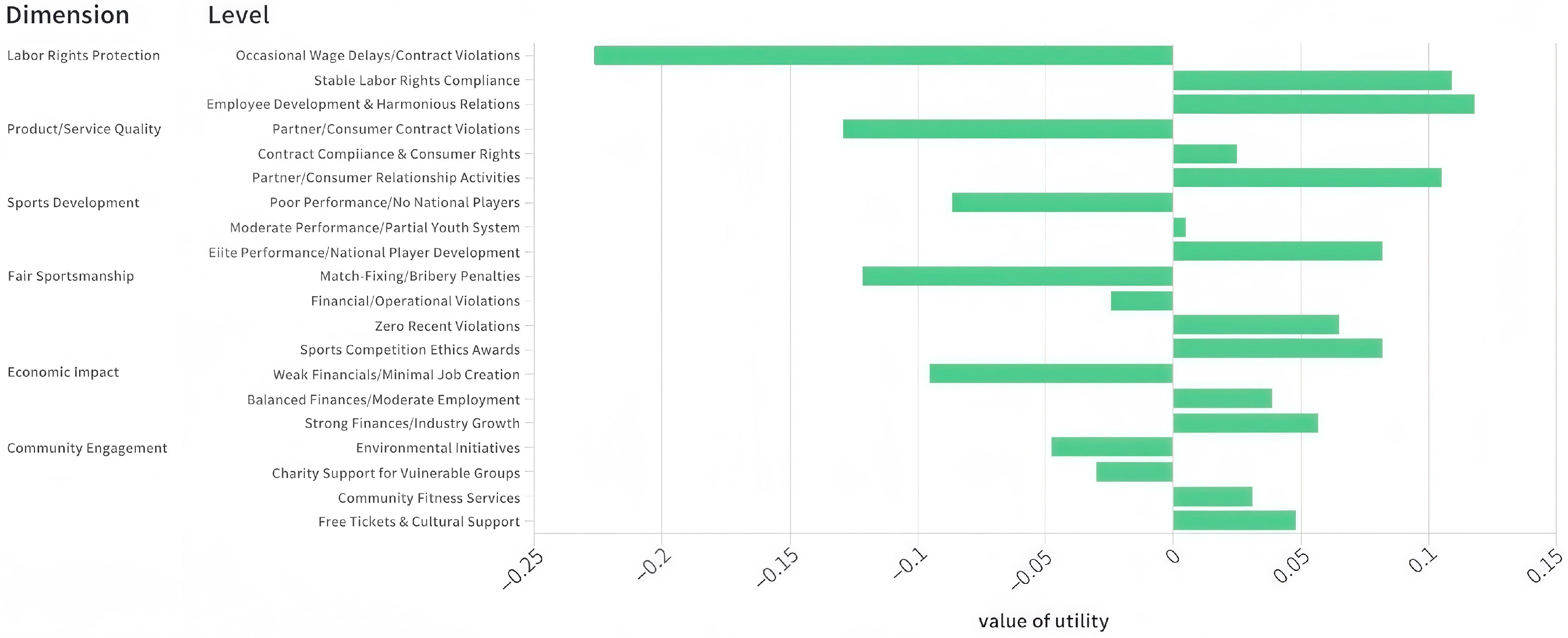

4.1. Analysis of the Public’s Preference for CSR of Professional Sports Clubs

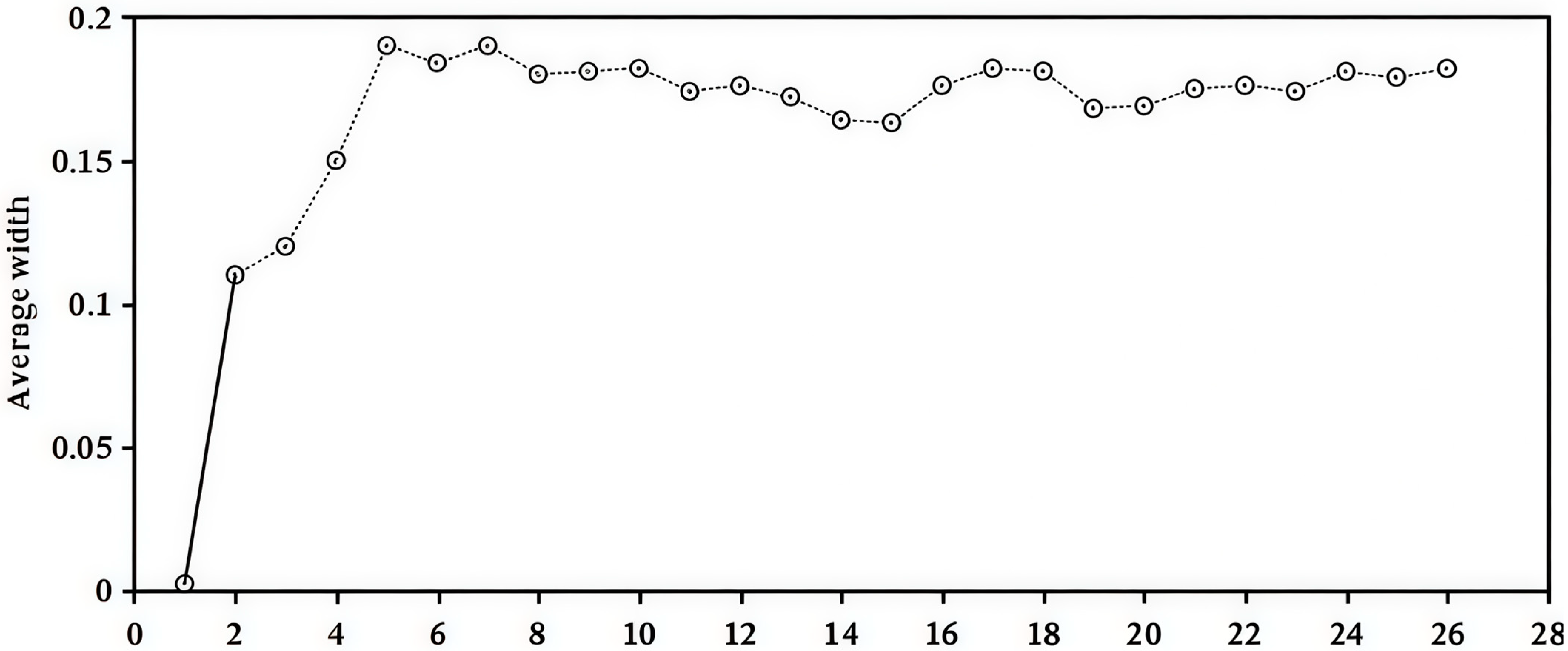

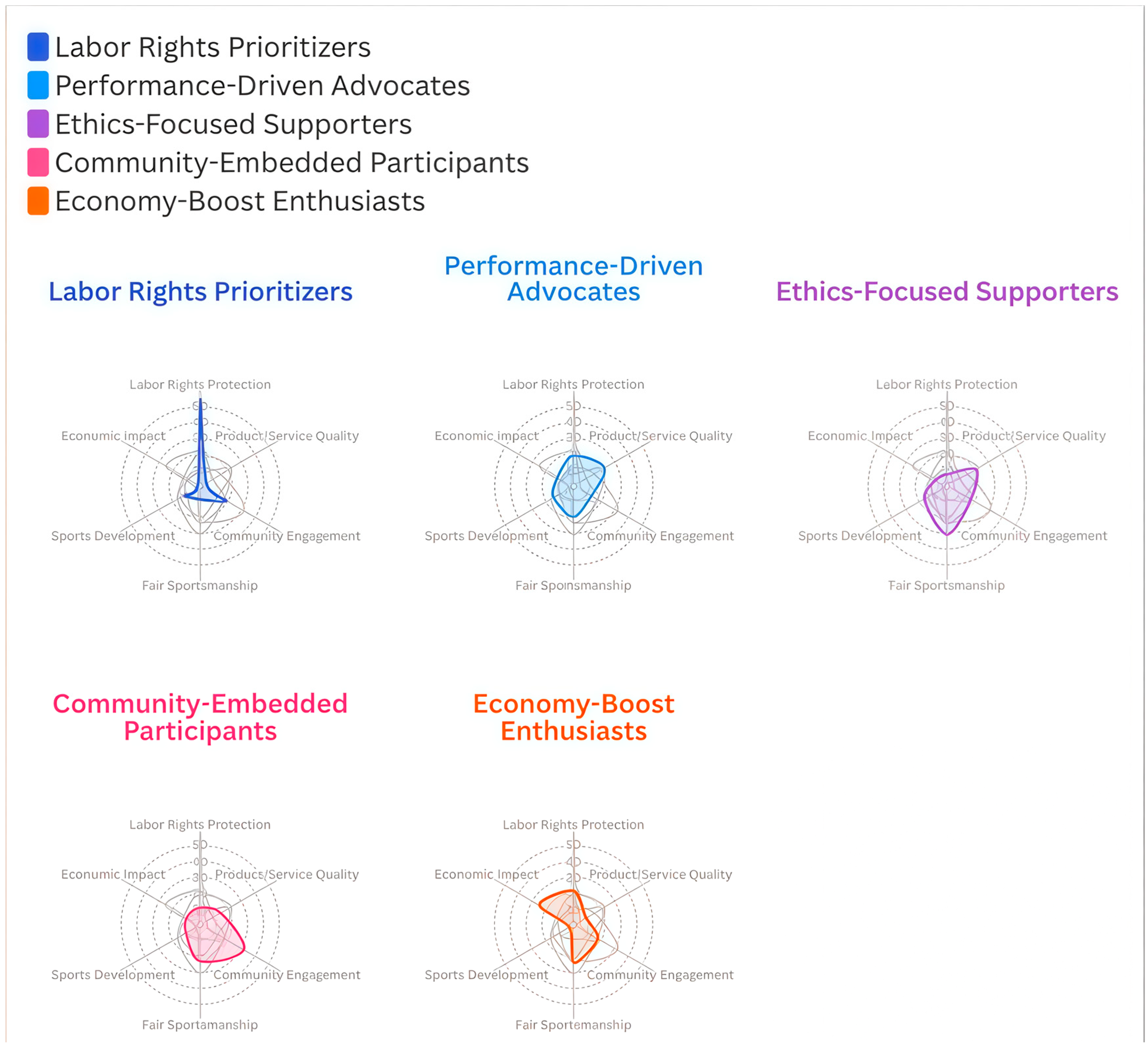

4.2. Cluster Analysis of CSR Preferences Among Different Groups of Professional Sports Clubs

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Empirical Interpretations

5.2. Cross-National Comparison and Contextual Implications

5.3. Theory Contribution

5.4. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Glynn, M.A.; Davis, G.F. Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 925–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.T.; Westerbeek, H.M. Sport as a vehicle for deploying corporate social responsibility. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2007, 25, 43–54. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/jcorpciti.25.43 (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Oeckl, S.J.S.; Morrow, S. CSR in professional football in times of crisis: New ways in a challenging new normal. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2022, 10, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumrodt, J.; Desbordes, M.; Bodin, D. Professional football clubs and corporate social responsibility. Sport Bus. Manag. Int. J. 2013, 3, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczycki, W.; Koenigstorfer, J. Doing good in the right place: City residents’ evaluations of professional football teams’ local (vs. distant) corporate social responsibility activities. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2016, 16, 502–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, A.J. Strategic options in fair trade retailing. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2002, 30, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.J.; Peirce, E.; Hartman, L.P.; Hoffman, W.M.; Carrier, J. Ethics, CSR, and sustainability education in the Financial Times top 50 global business schools: Baseline data and future research directions. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 73, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misener, L.; Mason, D.S. Fostering community development through sporting events strategies: An examination of urban regime perceptions. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 770–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; Pickett, G. How materialism affects environmental beliefs, concern, and environmentally responsible behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaaland, T.I.; Heide, M.; Grønhaug, K. Corporate social responsibility: Investigating theory and research in the marketing context. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskentli, S.; Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of CSR domains. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, A.; Yadav, R. Understanding the impact of CSR domain on brand relationship quality. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2021, 39, 559–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Rong, S.J. Corporate social responsibility in professional sports organizations: Concept, characteristics, and key components. J. Shandong Sport Univ. 2018, 34, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, Z.; Hao, F. An exploration of the social responsibility of professional sport clubs in China under the background of a harmonious society. J. Chengdu Sport Univ. 2012, 38, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamil, S.; Morrow, S. Corporate social responsibility in the Scottish Premier League: Context and motivation. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 143–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Tan, J. A theoretical framework of social responsibility in professional sports organizations. J. Cap. Univ. Phys. Educ. Sports 2013, 25, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B. A study on the social public service of professional football clubs under the theory of corporate social responsibility. J. Sport Sci. 2013, 33, 52–56, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Wu, L. Conceptual examination and reconstruction of corporate social responsibility in professional sport clubs in the Chinese context. J. Tianjin Univ. Sport 2023, 38, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.N. Evolution of social responsibility of Chinese professional sports clubs: Comprehensive review, in-depth perspective and future trend. J. Chengdu Sport Univ. 2022, 48, 40–45, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Cho, H.; Won, D. The knowledge structure of corporate social responsibility in sport management: A retrospective bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2023, 24, 771–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangham, L.J.; Hanson, K.; McPake, B. How to do (or not to do)… Designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan. 2009, 24, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerro, M.; Vecchio, R.; Caracciolo, F.; Pascucci, S.; Cembalo, L. Consumers’ heterogeneous preferences for corporate social responsibility in the food industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthong, S.; Taecharungroj, V. Which CSR activities are preferred by local community residents? Conjoint and cluster analyses. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wilson, R.; Plumley, D.; Chen, X. Perceived corporate social responsibility performance in professional football and its impact on fan-based patronage intentions: An example from Chinese football. Int. J. Sports Mark. Spons. 2019, 20, 353–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral Managment of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Managment: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing Inc.: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W.G., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Barbarossa, C.; Chen, Y.; Romani, S.; Korschun, D. Not all CSR initiatives are perceived equal: The influence of CSR domains and focal moralities on consumer responses to the company and the cause. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiganis, A.; Chrysochou, P.; Mitkidis, P.; Krystallis, A. Social order or social justice? The relationship of political ideology with consumer preferences for corporate social responsibility. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Kent, A. Do fans care? Assessing the influence of corporate social responsibility on consumer attitudes in the sport industry. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 743–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lin, Y.H. Comparison between various corporate social responsibility initiatives based on spectators’ attitudes and attendance intention for a professional baseball franchise. Sport Mark. Q. 2021, 30, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, I.P.; de Frutos Madrazo, P.; Rodriguez-Prado, B.; Martin-Cervantes, P.A. A gravity model to explain the flows away of football fans: A panel data analysis. Soc. Sci. J. 2023, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. Spectator demand, uncertainty of results, and public interest: Evidence from the English Premier League. J. Sports Econ. 2018, 19, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feddersen, A.; Rott, A. Determinants of demand for televised live football: Features of the German National Football Team. J. Sports Econ. 2011, 12, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainmueller, J.; Hangartner, D.; Yamamoto, T. Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2395–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H. Chinese football urgently needs to eliminate chronic problems. Workers’ Daily, 1 February 2023; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. The theory and practice of corporate social responsibility in Chinese professional sports clubs. Sport Sci. 2013, 33, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. General Administration of Sport of China and Ministry of Public Security Deepen Special Rectification of Match-Fixing, Gambling, and Gang-Related Issues in Professional Football Leagues. 14 January 2015. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n20001280/n20745751/c28089461/content.html (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Jing, M.; Guo, J.; Hu, B. Analysis and governance of deviant behavior among professional athletes. J. Sports Cult. Guide 2020, 5, 67–72, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, S. Youth basketball talent development in China under the revitalization of the “three major ball games”: Lessons from the U.S. experience and directions for Chinese practice. J. Shenyang Sport Univ. 2023, 42, 102–108, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, A.; Tele, A.; Kumar, M. Mental health service preferences of patients and providers: A scoping review of conjoint analysis and discrete choice experiments from global public health literature over the last 20 years (1999–2019). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, H.S.; Rapeli, L. Immediate rewards or delayed gratification? A conjoint survey experiment of the public’s policy preferences. Policy Sci. 2021, 54, 63–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.; Voss, D. (Eds.) Design and Analysis of Experiments; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidai, S.; Shafir, E. Are ‘nudges’ getting a fair shot? Joint versus separate evaluation. Behav. Public Policy 2020, 4, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.M. Theoretical frontiers: A preliminary exploration of the professionalization of sports. China Sports Daily, 28 April 2017. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n20001280/n20745751/n20767279/c21261116/content.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Wang, B.; Pyun, D.Y.; Piggin, J. Developing a conceptual model of corporate social responsibility of the Chinese Super League clubs. Quest 2024, 76, 382–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, H.; Babiak, K.M. Beyond the game: Perceptions and practices of corporate social responsibility in the professional sport industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudis, A.; Evangelinos, K.; Malesios, C. Priorities and perceptions for corporate social responsibility: An NGO perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, S. National culture and social desirability bias in measuring public service motivation. Adm. Soc. 2013, 48, 444–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Lu, H.; Cai, J.; Zhang, S. Constructing a social responsibility system for professional sports clubs based on the perspective of China. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2025, 34, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Bratslavsky, E.; Finkenauer, C.; Vohs, K.D. Bad is stronger than good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 5, 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Kaplanidou, K. How corporate social responsibility and social identities lead to corporate brand equity: An evaluation in the context of sport teams as brand extensions. Sport Mark. Q. 2021, 30, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P. How expectations and perceptions of corporate social responsibility impact NBA fan relationships. Sport Mark. Q. 2016, 25, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.P. Sports-based economic development. Econ. Dev. Rev. 1997, 15, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

| CSR Attributes | CSR Attribute Levels |

|---|---|

| Labor Rights Protection | Level 1: The club has delayed salaries and used dual contracts; Level 2: The club operates stably, meeting basic labor and contractual obligations; Level 3: The club maintains strong labor relations and provides employee development opportunities. |

| Product/Service Quality Enhancement | Level 1: The club has exhibited contractual violations with partners and consumer rights infringement cases; Level 2: The club demonstrates strict contractual compliance with partners and consistent consumer rights protection; Level 3: The club cultivates sustainable relationships with sponsors and consumers through year-round engagement initiatives. |

| Community Engagement | Level 1: The club provides subsidized, high-quality fitness training services to the community; Level 2: The club demonstrates sustained commitment to vulnerable groups through poverty relief and disability support programs; Level 3: The club institutionalizes environmental initiatives including low-carbon lifestyle promotion and waste management campaigns Level 4: The club facilitates local sports culture development through complimentary game ticket distribution. |

| Fair Play Promotion | Level 1: The club has been penalized by state authorities for match-fixing and bribery violations; Level 2: The club received league sanctions for operational misconduct including match violations and financial misreporting; Level 3: The club maintains full compliance with league regulations without recent violations; Level 4: The club has consistently earned the league’s Sportsmanship Award for exemplary management practices. |

| Sport Development | Level 1: The club demonstrates suboptimal competitive performance with no youth training system and zero national team selections; Level 2: The club maintains average performance with a partial youth training system and occasional national team call-ups; Level 3: The club achieves top-tier performance through its well-developed youth training system, and has consistently multiple players for national team. |

| Economic development contribution | Level 1: The club operates with constrained finances, demonstrating minimal impact on local employment and supply chain development; Level 2: The club maintains financial stability while generating moderate employment, although with limited collaboration with local industries; Level 3: The club is in good financial condition, generates considerable employment opportunities, and collaborates with local businesses to boost the development of sectors such as catering and tourism. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Song, J.; Wang, Z. What Do We Focus on? Investigating Chinese Public Preferences for CSR Initiatives in Professional Sports Clubs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9648. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219648

Wang C, Song J, Wang Z. What Do We Focus on? Investigating Chinese Public Preferences for CSR Initiatives in Professional Sports Clubs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9648. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219648

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chenxu, Jiatong Song, and Zhiwen Wang. 2025. "What Do We Focus on? Investigating Chinese Public Preferences for CSR Initiatives in Professional Sports Clubs" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9648. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219648

APA StyleWang, C., Song, J., & Wang, Z. (2025). What Do We Focus on? Investigating Chinese Public Preferences for CSR Initiatives in Professional Sports Clubs. Sustainability, 17(21), 9648. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219648