Effects of Humic Acids, Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Derived Cuttlebones: Performance and Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Synthesis of the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples

2.3. Extraction of Humic Acids from Different Soils

2.4. Adsorption Experiment

2.5. Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging Experiment

2.6. Characterization Methods of the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples and the Self-Extracted HAs

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization Analysis of the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples and the Self-Extracted HAs

3.2. Effects of HAs on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples

3.2.1. Adsorption Performance of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples with HAs

3.2.2. Adsorption Kinetics of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples with HAs

3.2.3. Adsorption Isotherms and Thermodynamics of Cd (II) in the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples with HAs

3.2.4. Adsorption Mechanism and Process of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples with HAs

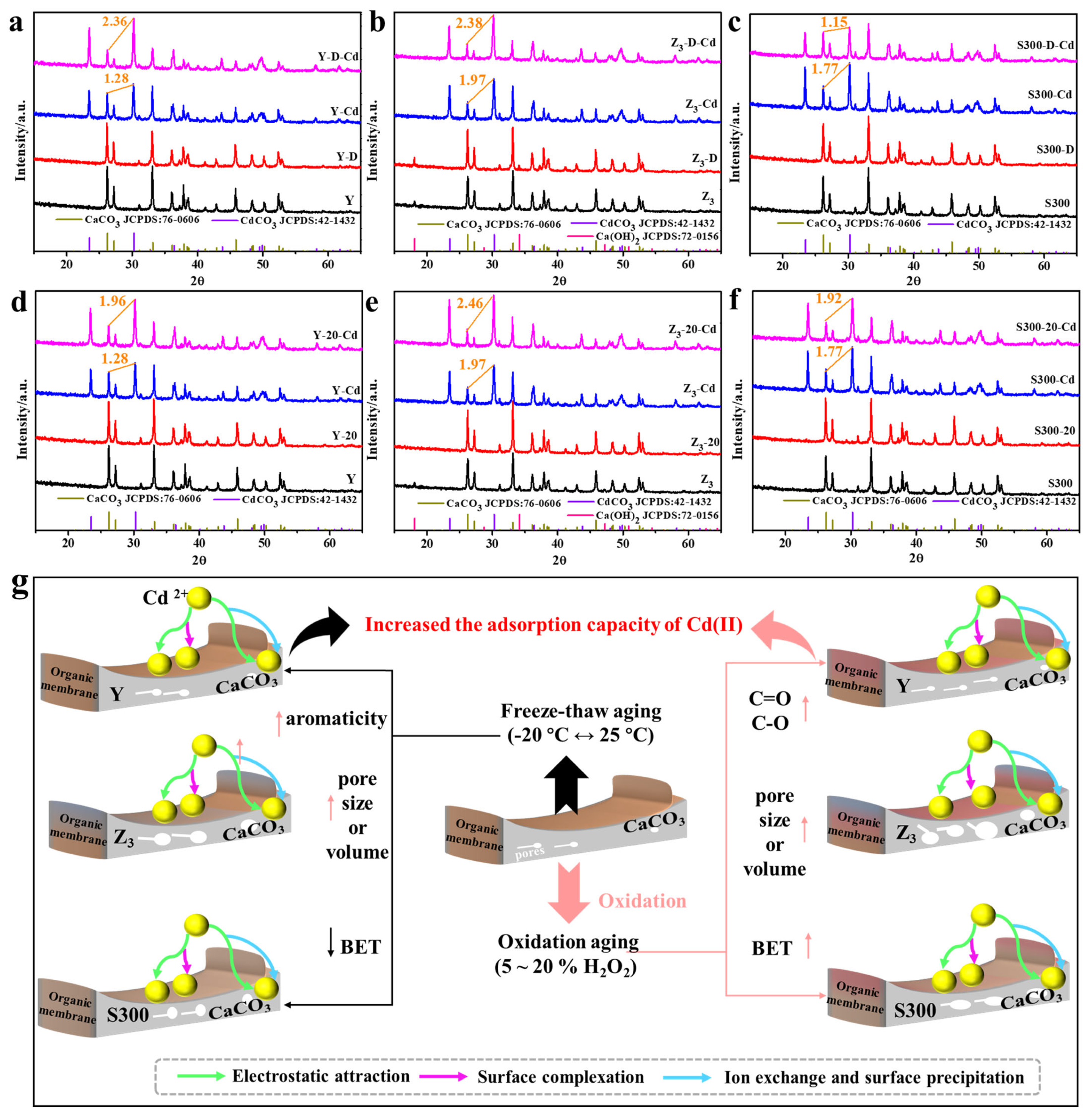

3.3. Effects of Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples

3.3.1. Adsorption Performance of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples After Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging

3.3.2. Adsorption Mechanism of Cd(II) by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples After Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging

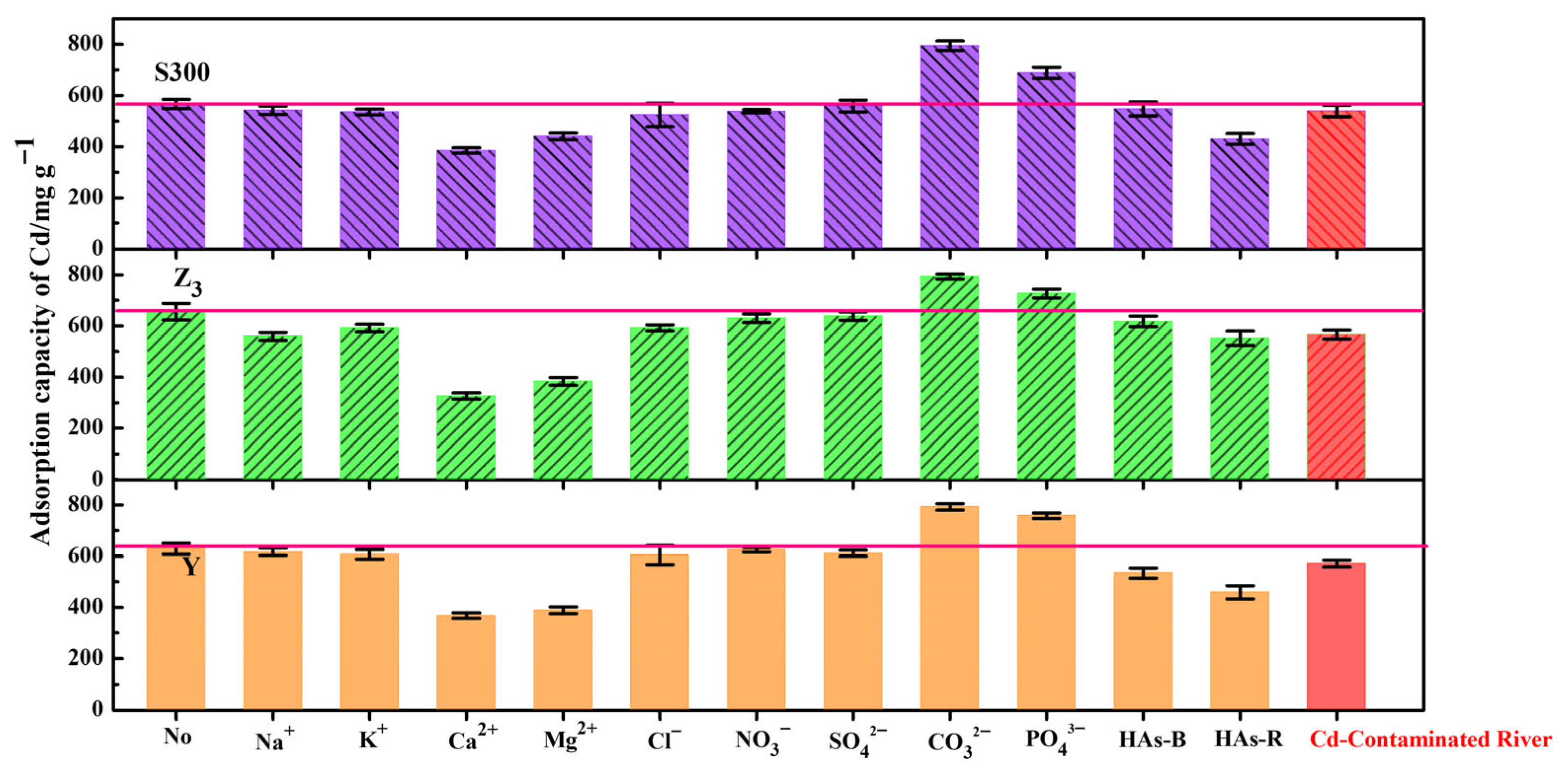

3.4. Remediation of the Natural Cadmium-Contaminated River by the Cuttlebone-Derived Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, W.P.; Han, L.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, W.Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, H.P.; Hou, S.L.; Li, J.; Chen, M.F. The impact of heteroaggregation between nZVI and SNPs on the co-transport of Cd (II) in saturated sand columns. Water Res. 2024, 258, 121822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Q.; Lawluvy, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ighalo, J.O.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.J.; Yap, P.S. Adsorption of cadmium and lead from aqueous solution using modified biochar: A review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.D.; Xu, R.H.; Ma, C.L.; Yu, J.; Lei, S.; Han, Q.Y.; Wang, H.J. Potential functions of engineered nanomaterials in cadmium remediation in soil-plant system: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 336, 122340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Jeyakumar, P.; Wang, Z.; Sun, S.Y.; Qiu, T.Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, J.; Huang, M.; et al. Unveiling the impacts of microplastics on cadmium transfer in the soil-plant-human system: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 477, 135221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazkhani, S.; Aminsharei, F.; Hassanzadeh-Tabrizi, S.A.; Malekzadeh, A.; Ameri, E. Synthesis and modification of nanofiltration membranes with dendrimer-modified graphene oxide to remove lead and cadmium ions from aqueous solutions. Cleaner Eng. Technol. 2024, 23, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marszałek, M.; Knapik, E.; Piotrowski, M.; Chruszcz-Lipska, K. Removal of cadmium from phosphoric acid in the presence of chloride ions using commercially available anion exchange resins. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2023, 118, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.M.; Liao, C.H.; Venkatesan, S.; Liu, Y.T.; Tzou, Y.M.; Jien, S.H.; Lin, M.C.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Osman, A.I. Sulfur-functionalized sawdust biochar for enhanced cadmium adsorption and environmental remediation: A multidisciplinary approach and density functional theory insights. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Singha, T.; Nambissan, P.M.G. Defect characteristics of cadmium oxide nanocrystallites synthesized via a chemical precipitation method. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2023, 181, 111513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.X.; Zhao, J.T.; Ding, Z.D.; Xiong, F.; Liu, X.Q.; Tian, J.; Wu, N.F. Cadmium-absorptive Bacillus vietnamensis 151-6 reduces the grain cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.): Potential for cadmium bioremediation. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 254, 114760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, L.; Chen, W.D.; Tong, Y.J.; Wang, X.S. Controllable synthesis of coral-like hierarchical porous magnesium hydroxide with various surface area and pore volume for lead and cadmium ion adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 416, 125922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.W.; Chen, K.P.; Wu, J.C.; Li, P. Reactive transport of Cd2+ in porous media in the presence of xanthate: Experimental and modeling study. Water Res. 2024, 266, 122402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.F.; Wang, D.; Cao, R.Y.; Sun, F.W.; Li, J.X. Magnetically separable h-Fe3O4@phosphate/polydopamine nanospheres for U(VI) removal from wastewater and soil. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egbosiuba, T.C.; Egwunyenga, M.C.; Tijani, J.O.; Mustapha, S.; Abdulkareem, A.S.; Kovo, A.S.; Krikstolaityte, V.; Veksha, A.; Wagner, M.; Lisak, G. Activated multi-walled carbon nanotubes decorated with zero valent nickel nanoparticles for arsenic, cadmium and lead adsorption from wastewater in a batch and continuous flow modes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 126993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, K.; Wei, C.Z.; Liang, B.; Huang, H.L.; Huang, G.; Li, S.H.; Liang, J.; Huang, K. Thiol and amino co-grafting modification of sugarcane bagasse lignin nanospheres to enhance the adsorption capacity of cadmium ion. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2024, 222, 119982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmonem, H.A.; Hassanein, T.F.; Sharafeldin, H.E.; Gomaa, H.; Ahmed, A.S.A.; Abdel-lateef, A.M.; Allam, E.M.; Cheira, M.F.; Eissa, M.E.; Tilp, A.H. Cellulose-embedded polyacrylonitrile/amidoxime for the removal of cadmium (II) from wastewater: Adsorption performance and proposed mechanism. Colloid. Surf. A 2024, 684, 133081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalajiolyaie, A.; Jian, C. Advancing wastewater treatment from cadmium contamination via functionalized graphene nanosheets. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yin, J.; Ma, Q.; Baihetiyaer, B.; Sun, J.X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.J.; Wang, J.; Yin, X.Q. Montmorillonite-reduced graphene oxide composite aerogel (M−rGO): A green adsorbent for the dynamic removal of cadmium and methylene blue from wastewater. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 296, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.K.; Khatoon, S.; Nizami, G.; Fatma, U.K.; Ali, M.; Singh, B.; Quraishi, A.; Assiri, M.A.; Ahamad, S.; Saquib, M. Unleashing the power of bio-adsorbents: Efficient heavy metal removal for sustainable water purification. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 64, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Mondal, A.; Hinkley, C.; Kondaveeti, S.; Vo, P.H.N.; Ralph, P.; Kuzhiumparambil, U. Influence of pyrolysis time on removal of heavy metals using biochar derived from macroalgal biomass (Oedogonium sp.). Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 414, 131562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.C.; Jabeur, F.; Pontoni, L.; Mechri, S.; Jaouadi, B.; Sannino, F. Sustainable removal of arsenic from waters by adsorption on blue crab, Portunus segnis (Forskål, 1775) chitosan-based adsorbents. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2024, 33, 103491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.F.; Cao, R.; Li, M.S.; Chen, G.X.; Tian, J.F. Superhydrophobic and superoleophilic cuttlebone with an inherent lamellar structure for continuous and effective oil spill cleanup. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 420, 127596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, D.; Yang, M.Y.; Li, F.F.; Zhao, J.F.; He, Z.H.; Bai, Y.W. New discovery of extremely high adsorption of environmental DNA on cuttlefish bone pyrolysis derivative via large pore structure and carbon film. Waste Manag. 2024, 175, 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.T.; Chen, C.Y.; Shiao, J.C.; Lin, S.; Wang, C.H. Temperature-dependent fractionation of stable oxygen isotopes differs between cuttlefish statoliths and cuttlebones. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C.; Ou, X.W.; Tian, C.; Lin, Z.; Dang, Z. Biogenic calcium carbonate with hierarchical organic-inorganic composite structure enhancing the removal of Pb(II) from wastewater. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 35785–35793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, H.; Bouzid, T.; Naboulsi, A.; Grich, A.; Mountassir, E.M.; Regti, A.; El Himri, M.; El Haddad, M. Adsorption of malachite green using waste marine cuttlefish bone powder: Experimental and theoretical investigations. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagyaraj, S.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Khan, M.; Kasak, P.; Krupa, I. Modified os sepiae of Sepiella inermis as a low cost, sustainable, bio-based adsorbent for the effective remediation of boron from aqueous solution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2022, 29, 71014–71032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.Q.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Bai, X.A.; He, Z.H. Adsorption of Cd(II) from Wastewater by Cuttlebone and Its Derived Materials. In Advances in Watersheds Water Pollution and Ecological Restoration; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Qin, P.R.; Sun, X.; Yin, M.N.; He, Z.H.; Wang, B. Adsorption of Pb(II) by cuttlebone-derived materials and its stability. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 490, 01011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakootian, M.; Shiri, M.A. Investigating the removal of tetracycline antibiotic from aqueous solution using synthesized Fe3O4@Cuttlebone magnetic nanocomposite. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 221, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salati, S.; Papa, G.; Adani, F. Perspective on the use of humic acids from biomass as natural surfactants for industrial applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Shao, T.; Karanfil, T.J. The effects of dissolved natural organic matter on the adsorption of synthetic organic chemicals by activated carbons and carbon nanotubes. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Li, Z.W.; Chen, J.; Jin, C.S.; Cao, W.C.; Peng, B. Humic-like components in dissolved organic matter inhibit cadmium sequestration by sediment. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 150, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.X.; Li, J.X.; Ren, X.M.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, X.K. Few-Layered graphene oxide nanosheets as superior sorbents for heavy metal ion pollution management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 10454–10462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.D.; Shen, L.; Cao, Y.Q. Animal or plant waste-derived biochar for Cd(II) immobilization: Effects of freeze-thaw-wet-dry cyclic aging on adsorption behavior in tea garden soils. Desalin. Water Treat. 2020, 182, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of chitosan with ultra high molecular weight. Carbohyd. Polym. 2016, 148, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.F.; Cao, J.M.; Li, Y.X.; Howard, A.; Yu, K.W. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on characteristics of biochars derived from different feedstocks: A case study on ammonium adsorption capacity. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.M.; An, T.T.; Chi, F.Q.; Wei, D.; Zhou, B.K.; Hao, X.Y.; Jin, L.; Wang, J.K. Evolution over years of structural characteristics of humic acids in Black Soil as a function of various fertilization treatments. J. Soil. Sediment. 2018, 19, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Hodson, M.E. The impact of varying abiotic humification conditions and the resultant structural characteristics on the copper complexation ability of synthetic humic-like acids in aquatic environments. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 165, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.P.; Yang, Z.P.; Zhang, Q.X.; Fu, D.J.; Chen, P.; Li, R.B.; Liu, H.J.; Wang, Y.L.; Liu, Y.; Lv, W.Y.; et al. Effect of tartaric acid on the adsorption of Pb (II) via humin: Kinetics and mechanism. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2020, 107, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, P.; Huang, Q.Y.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, D.H.; Zhou, X.Y.; Rong, X.M.; Liang, W. Effects of low-molecular-weight organic ligands and phosphate on DNA adsorption by soil colloids and minerals. Colloid. Surf. B 2007, 54, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.T.; Zheng, Y.M.; Chen, J.P. Enhanced adsorption of arsenate onto a natural polymer-based sorbent by surface atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2011, 356, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, W. Effects of macromolecular humic/fulvic acid on Cd(II) adsorption onto reed-derived biochar as compared with tannic acid. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, R.Q.; Li, X.; Song, J.F.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y.T.; Ou, D.L. Comparison of the removal and adsorption mechanisms of cadmium and lead from aqueous solution by activated carbons prepared from Typha angustifolia and Salix matsudana. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 16092–16103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.T.; Li, G.X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Q.S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, D.D. Adsorption mechanism of arsenic(V) on aged polyethylene microplastics: Isotherms, kinetics and effect of environmental factors. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 18, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, S.; Wongrod, S.; Simon, S.; Guibaud, G.; Vinitnantharat, S. Simultaneous sequestration of cadmium and lead in brackish aquaculture water by biochars: A mechanistic insight. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 16, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Chen, H.Y.; Zhang, J.F.; Li, J.X. Easily synthesized mesoporous aluminum phosphate for the enhanced adsorption performance of U(VI) from aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 432, 128675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.X. Efficient remediation and synchronous recovery of uranium by phosphate-functionalized magnetic carbon-based flow electrode capacitive deionization. Water Res. 2025, 281, 123707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S.X.; Wang, Y.N.; Liu, X.; Shao, D.D.; Hayat, T.; Alsaedi, A.; Li, J.X. Removal of U(VI) from aqueous solution by amino functionalized flake graphite prepared by plasma treatment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4073–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, W.; Xiong, L.; Xu, N.; Ni, J. Influence of pH, ionic strength and humic acid on competitive adsorption of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Cr(III) onto titanate nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 215, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Ouyang, X.X.; Weng, L.P.; Chen, Y.L.; Li, Y.T. Enhanced cadmium removal by biochar and iron oxides composite: Material interactions and pore structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.Z.; Guo, Y.Y.; Li, B.; Xue, Z.L.; Jin, Z.W.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, L.X.; Zhao, C.H.; Yin, K.; Jouha, J.; et al. Highly efficient capture of cadmium ions by dual-layer calcium sulfide-calcium carbonate-loaded kelp biochar: Synthesis, adsorption and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 138842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, D.J.; Xu, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, X.Y.; Song, B.Q.; Xu, N. Biochar nanoparticles with different pyrolysis temperatures mediate cadmium transport in water-saturated soils: Effects of ionic strength and humic acid. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.T.; Weng, L.P. Enhanced cadmium immobilization in saturated media by gradual stabilization of goethite in the presence of humic acid with increasing pH. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toprak, M.; Yıldız, B.; Zaman, B.T.; Bozyiğit, G.D.; Temuge, İ.D.; Çetin, G.; Bakırdere, S. Microwave-assisted hydrothermal synthesis of zinc-tin based nanoflower for the adsorptive removal of cadmium from synthetic wastewater. Water Air Soil Poll. 2024, 235, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, D.O.; Silva, M.A.; Faria, D.N.; Cipriano, D.F.; Freitas, J.C.C.; Santos, F.S.; Lima, T.M.; Vasconcelos, S.C.; Pietre, M.K. Zeolite/calcium carbonate composite for a synergistic adsorption of cadmium in aqueous solution. Next Mater. 2025, 6, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Zhang, S.Y.; Li, Q.Y.; Li, A.Y.; Gan, W.X.; Hu, L.N. Efficient removal of lead, cadmium, and zinc from water and soil by MgFe layered double hydroxide: Adsorption properties and mechanisms. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Hu, L.; He, N.; Jiang, Z.P.; Gong, J.Y.; Jiang, C.Y.Z.; Zhao, H.B. Lead and cadmium adsorption by phanerochaete chrysosporium under the protection of phosphorus-containing biochar: Effects and mechanisms. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.X.; Zhu, B.W.; Yu, J.X.; Wang, X.T.; Zhang, C.; Qin, Y. A biomass carbon prepared from agricultural discarded walnut green peel: Investigations into its adsorption characteristics of heavy metal ions in wastewater treatment. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2022, 13, 12833–12847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.M.; Rivera-Hernández, M.; Álvarez, L.H.; Acosta-Rodríguez, I.; Ruíz, F.; Compeán-García, V.D. Biosynthesis and characterization of cadmium carbonate crystals by anaerobic granular sludge capable of precipitate cadmium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 246, 122797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.Y.; Liu, J.H.; Li, S.M.; Yang, W.H.; Wang, W.Y.; Li, K.; Sun, Y.Z.; Han, W.P.; Li, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. Effects of steady magnetic fields on NiRuO2 nanofibers for the electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 31585–31591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Petrović, J.; Šoštarić, T.; Ercegović, M.; Milojković, J.; Lopičić, Z.; Kojić, M. A mechanism assessment and differences of cadmium adsorption on raw and alkali-modified agricultural waste. Processes 2022, 10, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xv, C.H.; Zhao, Z.R.; Wang, F.Y.; Lei, W.; Xia, M.Z.; Wang, Z.H. The facile preparation of polydopamine-modified sepiolite and its adsorption properties and microscopic mechanism for cadmium ion. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.T.; Xu, Y.; Gu, L.T.; Zhu, M.Q.; Yang, P.; Gu, C.H.; Liu, Z.; Feng, X.H.; Tan, W.F.; Huang, Q.Y.; et al. Elucidating phosphate and cadmium cosorption mechanisms on mineral surfaces with direct spectroscopic and modeling evidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 20211–20223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adsorbents | pH | T/K | Dosage/g L−1 | CHAs/mg L−1 | qmax/mg g−1 | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KAC@CaS-CaCO3 | 5.0 | 298 | 0.4 | - | 368.4 | [51] |

| MWCNTs@NiNPs | 5.5 | 303 | 0.03 | - | 415.8 | [13] |

| Zinc-tin nanoflowers | 6.0 | 298 | 2.0 | - | 10.9 | [54] |

| Zeolite/CaCO3 | 5.2 | 298 | 0.4 | - | 113.2 | [55] |

| MgFe-LDHs | 6.0 | 298 | 1.0 | - | 869.6 | [56] |

| Goethite@sand | 7.5 | 298 | 1.0 | 20 | ~0.16 | [53] |

| Biochar and iron Oxides | 7.0 | 298 | 0.002 | 40 | 34.64 | [50] |

| Titanate nanotubes | 5.0 | 298 | 0.2 | 5.0 | ~60 | [49] |

| Straw biochar | 8.8 | 298 | 0.2 | 10 | 61.5 | [52] |

| Reed biochar | 5.0 | 298 | 1.0 | 100 | 195.57 | [42] |

| Y | 7.5 | 298 | 0.048 | 10 | 476.60 (570.89) | This work |

| Z3 | 7.5 | 298 | 0.048 | 10 | 569.98 (617.37) | |

| S300 | 7.5 | 298 | 0.048 | 10 | 426.70 (529.48) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Wang, D.; Shi, L.; Xie, H.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, D. Effects of Humic Acids, Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Derived Cuttlebones: Performance and Mechanism. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219628

He Z, Wang D, Shi L, Xie H, Xiong Y, Zhang D. Effects of Humic Acids, Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Derived Cuttlebones: Performance and Mechanism. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219628

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhaohui, De Wang, Lin Shi, Hongqi Xie, Yanqing Xiong, and Di Zhang. 2025. "Effects of Humic Acids, Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Derived Cuttlebones: Performance and Mechanism" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219628

APA StyleHe, Z., Wang, D., Shi, L., Xie, H., Xiong, Y., & Zhang, D. (2025). Effects of Humic Acids, Freeze–Thaw and Oxidative Aging on the Adsorption of Cd(II) by the Derived Cuttlebones: Performance and Mechanism. Sustainability, 17(21), 9628. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219628