Acceptance of Automated Cars and Shared Mobility Services: Towards a Holistic Analysis for Sustainable Mobility Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

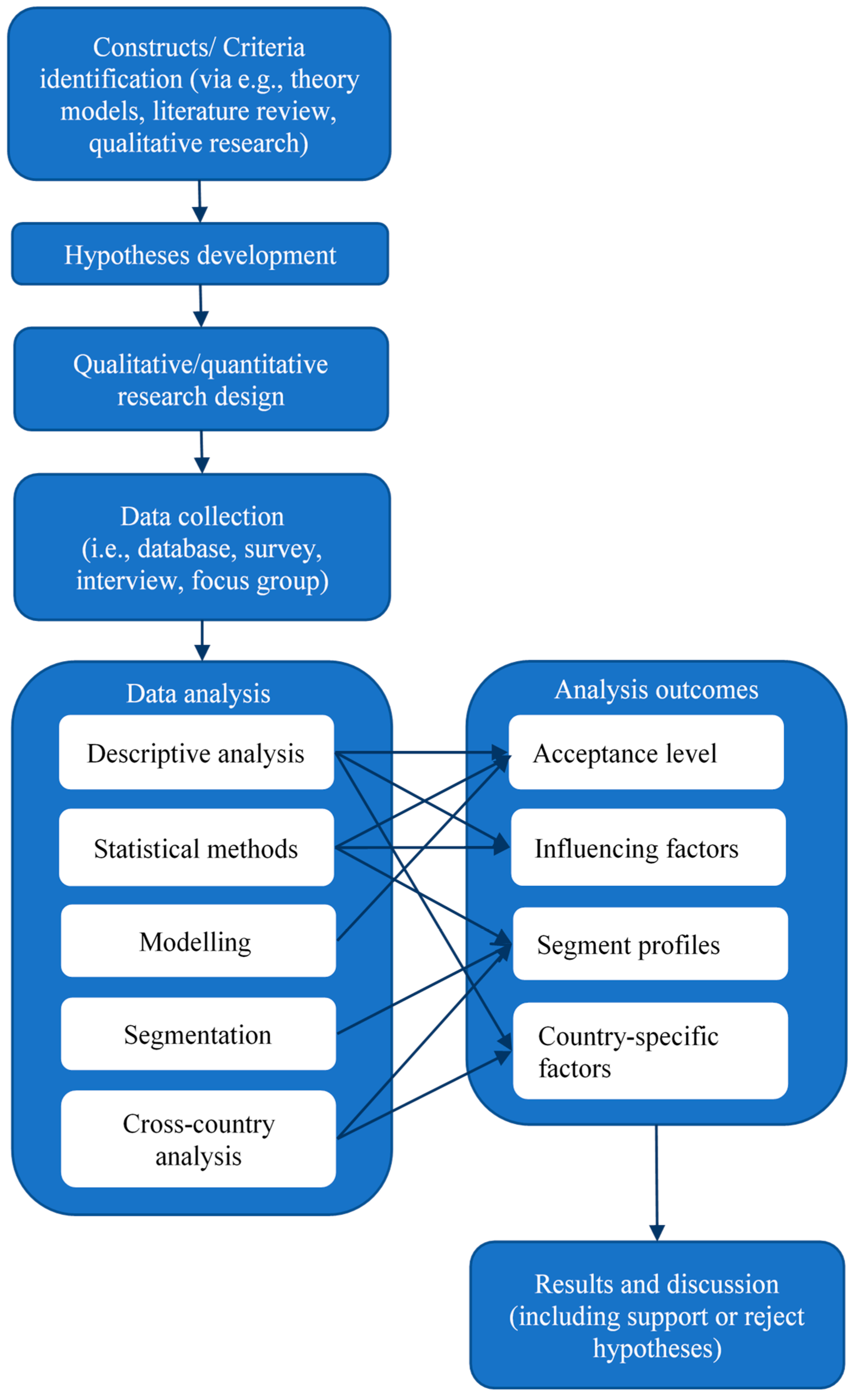

3.1. Holistic Framework

3.2. Survey Design and Acceptance by Category

3.3. Dataset Description

3.4. Cross-Country Analysis

3.5. Statistical Tests

4. Results and Discussion

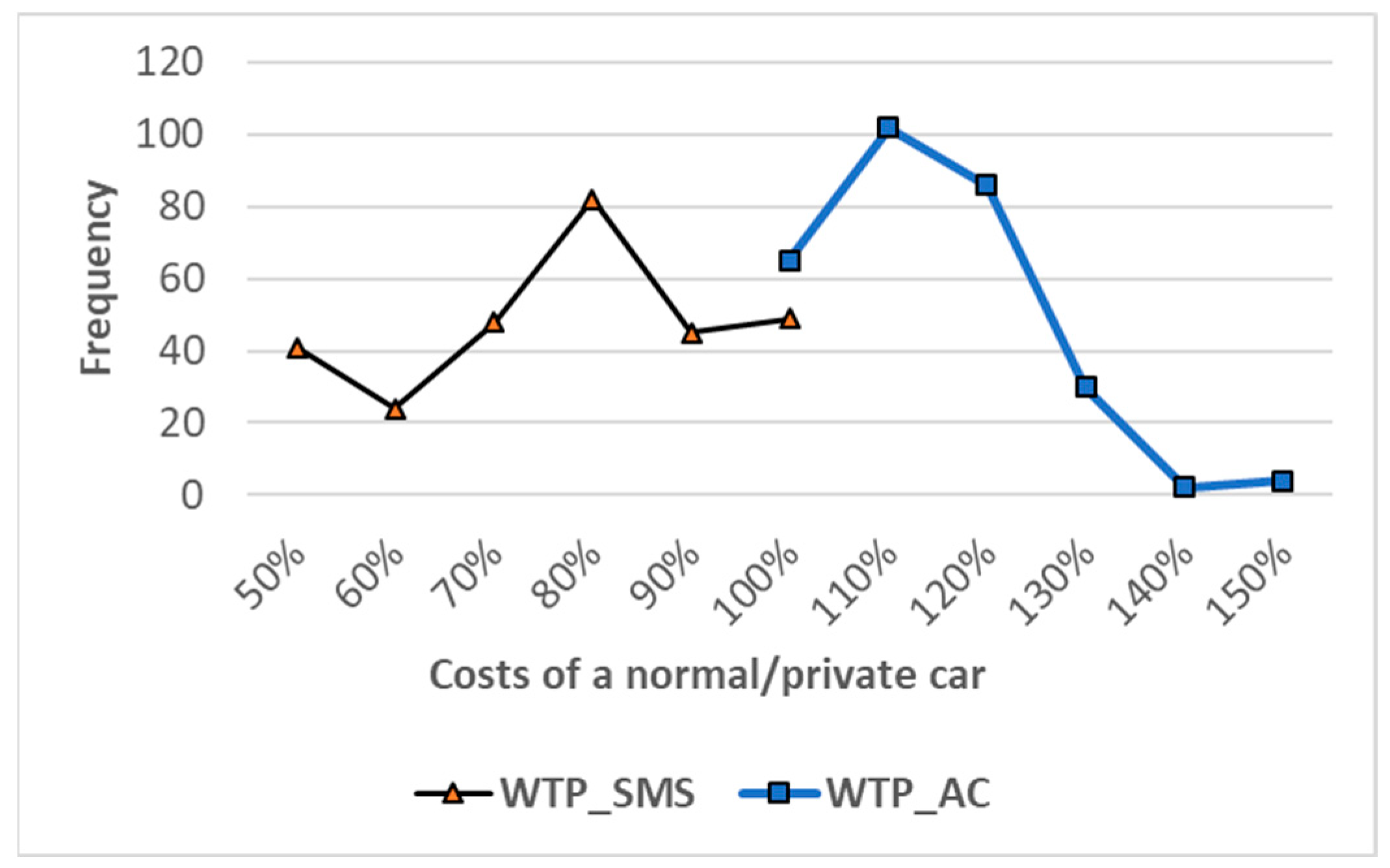

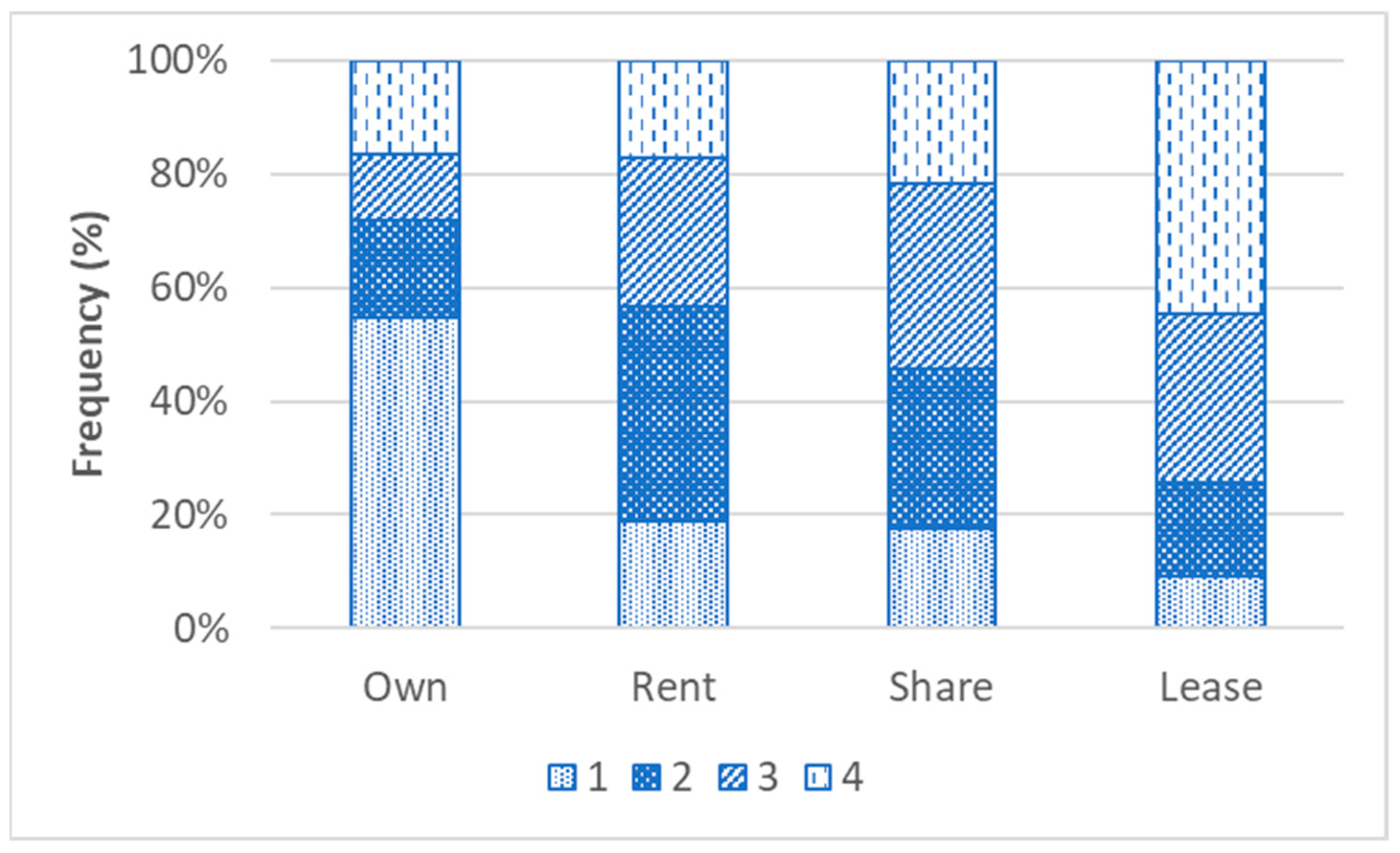

4.1. General Acceptance

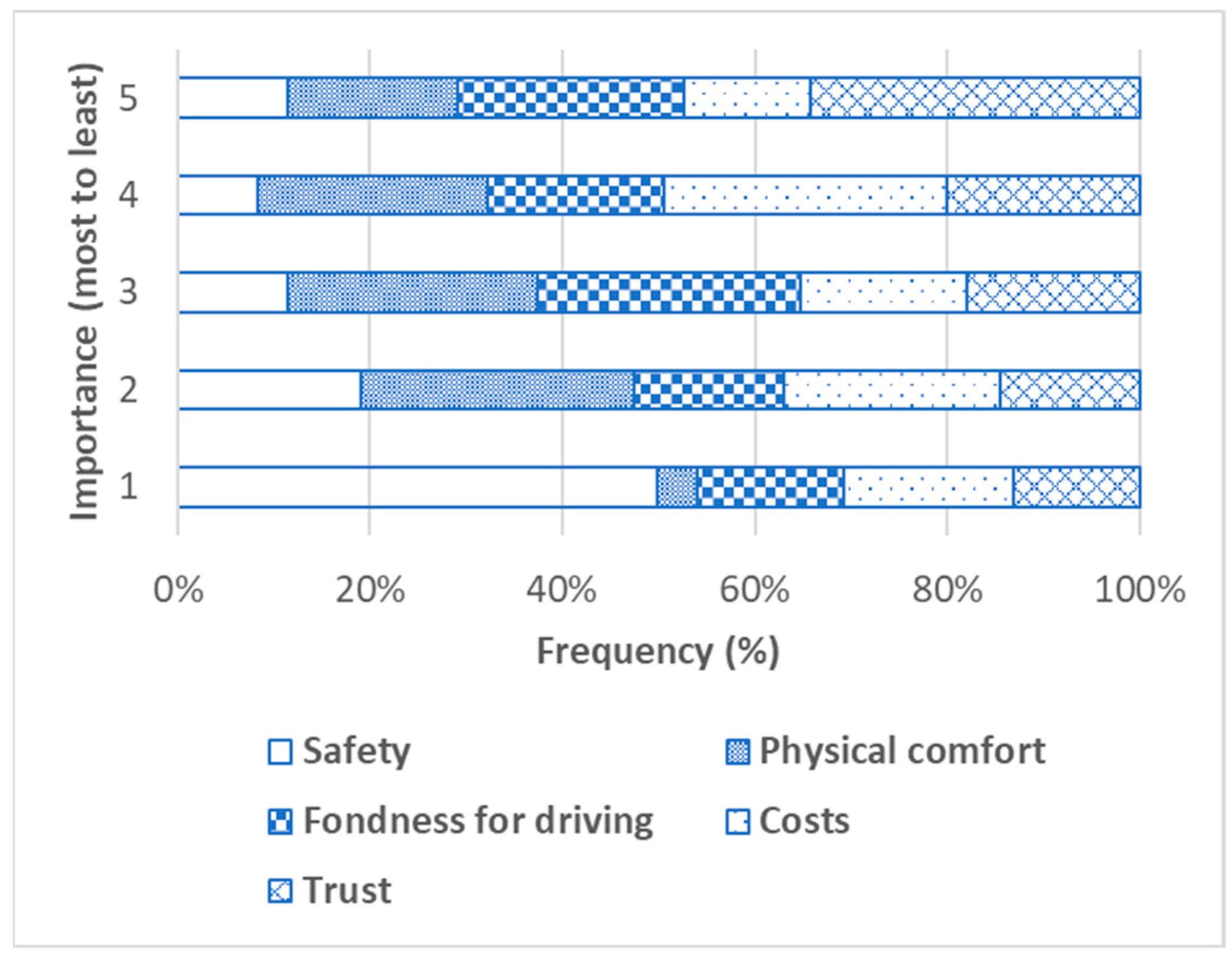

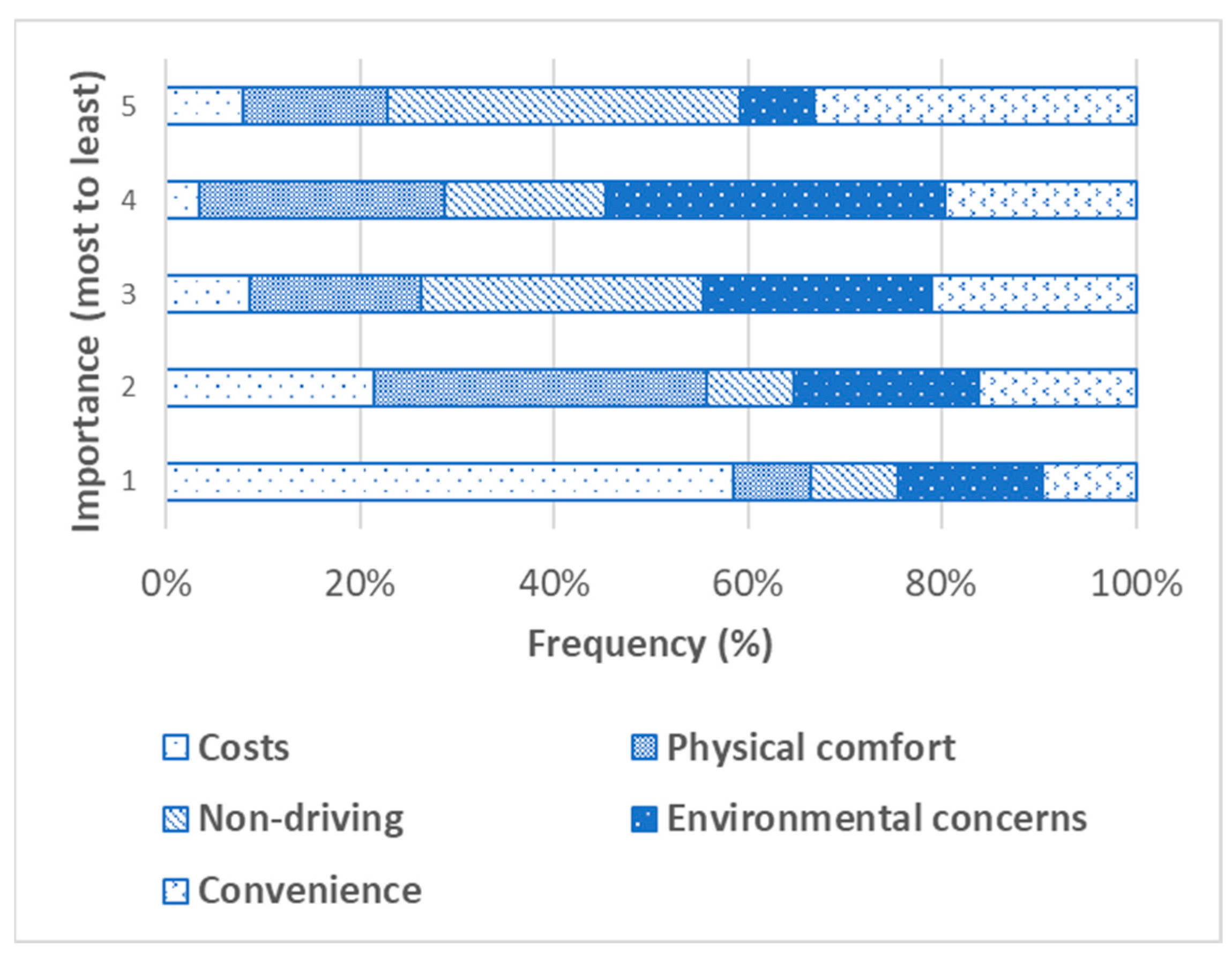

4.2. Influencing Factors on Acceptance of AC and SMS

4.3. Cross-Country Aspects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMS | Shared Mobility Services |

| AC | Automated Car |

| AV | Automated Vehicle |

| WTU | Willingness to Use |

| CCAM | Cooperative, Connected, and Automated Mobility |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| PT | Public Transport |

| CS | Car Sharing |

| WTP | Willingness to Pay |

| EV | Electric Vehicles |

| FFCS | Free-Floating Car Sharing |

| BI | Behavioral Intention to Use |

| UTAUT | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology |

| ECS | Electric Car Sharing |

| AECS | Automated Electric Car Sharing |

| WTB | Willingness to Buy |

| SAV | Shared Automated Vehicles |

| EC | Electric Cars |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| RS | Ridesharing |

| FCU | Frequency of Car Sharing Use |

| CR | Car Rental |

| EFTA | European Free Trade Association |

| RH | Ride hailing |

| CP | Carpooling |

| WTT | Willingness to Try |

| ACC | Adaptive Cruise Control |

| UI/UX | User Interface/User Experience |

| VOT | Value-of-time |

| EPV | Events-per-variable |

Appendix A

| Parameters for Chi-Square Test | p-Value | Parameters for Chi-Square Test | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTU_AC | Living area | 0.596 | WTU_SMS | Living area | 0.491 |

| Gender | 0.030 * | Gender | 0.077 | ||

| Driving license | 0.937 | Driving license | 0.076 | ||

| Accident experience | 0.956 | Accident experience | 0.051 | ||

| Education | 0.560 | Education | 0.918 | ||

| Physical disadvantages | 0.321 | Physical disadvantages | 0.094 | ||

| Useful_AC | 0.000 *** | Useful_AC | 0.000 *** | ||

| ETU_AC | 0.000 *** | ETU_AC | 0.219 | ||

| Used_CR | 0.004 ** | Used_CR | 0.313 | ||

| Used_CS | 0.155 | Used_CS | 0.002 ** | ||

| Used_CP | 0.526 | Used_CP | 0.001 ** | ||

| Used_RH | 0.000 *** | Used_RH | 0.000 *** | ||

| Preference_SMS | 0.001 *** | Preference_SMS | 0.001 ** | ||

| Useful_SMS | 0.002 ** | Useful_SMS | 0.000 *** | ||

| ETU_SMS | 0.069 | ETU_SMS | 0.005 ** | ||

| Drivetrain | 0.002 ** | Drivetrain | 0.000 *** | ||

| Parameters for Spearman’s Rank Correlation Test | r | Ts | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WTU_AC | Age group | −0.022 | 0.375 | 0.708 |

| Commute distance | −0.140 (vw) | 2.391 | 0.017 * | |

| No_people/household | −0.022 | 0.368 | 0.713 | |

| No_cars/household | 0.001 | 0.022 | 0.983 | |

| Car mileage | 0.057 | 0.975 | 0.330 | |

| FreqUse_PT | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.980 | |

| Mobility costs | 0.013 | 0.220 | 0.826 | |

| Knowledge_AC | 0.227 (w) | 3.951 | 0.000 *** | |

| FreqUse_AC | 0.336 (w) | 6.046 | 0.000 *** | |

| WTP_AC | 0.090 | 1.522 | 0.129 | |

| FreqUse_SMS | 0.054 | 0.909 | 0.364 | |

| WTU_CombiPT | 0.127 (vw) | 2.169 | 0.031 * | |

| WTP_SMS | 0.042 | 0.715 | 0.475 | |

| WTU_SMS | 0.262 (w) | 4.593 | 0.000 *** | |

| WTU_SMS | Age group | 0.001 | 0.011 | 0.991 |

| Commute distance | −0.170 (vw) | 2.927 | 0.004 * | |

| No_people/household | −0.046 | 0.774 | 0.439 | |

| No_cars/household | −0.317 (w) | 5.656 | 0.000 *** | |

| Car mileage | −0.158 (vw) | 2.715 | 0.007 ** | |

| FreqUse_PT | 0.170 (vw) | 2.916 | 0.004 ** | |

| Mobility costs | −0.091 | 1.554 | 0.121 | |

| Knowledge_AC | 0.074 | 1.257 | 0.210 | |

| FreqUse_AC | 0.049 | 0.830 | 0.407 | |

| WTP_AC | 0.096 | 1.630 | 0.104 | |

| FreqUse_SMS | 0.262 (w) | 4.593 | 0.000 *** | |

| WTU_CombiPT | 0.276 (w) | 4.864 | 0.000 *** | |

| WTP_SMS | 0.628 (m) | 13.680 | 0.000 *** | |

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| GenderMale | 1.373 | 0.943–2.001 | 0.0983 |

| GenderOther | 21.922 | 1.661–553.664 | 0.0225 * |

| CommuteD | 0.967 | 0.926–1.010 | 0.1302 |

| Transport_bikeYes | 1.613 | 1.062–2.457 | 0.0253 * |

| Transport_carYes | 1.133 | 0.762–1.686 | 0.5379 |

| Know_ACKnow a lot | 2.165 | 1.426–3.301 | 0.0003 * |

| Know_ACNo knowledge | 2.254 | 0.738–6.858 | 0.1504 |

| Know_ACStudy and research | 1.844 | 0.813–4.175 | 0.1412 |

| FreqUse_ACFew times per week | 0.591 | 0.336–1.035 | 0.0668 |

| FreqUse_ACNever | 0.022 | 0.006–0.072 | 0.0000 * |

| FreqUse_ACOnce per month | 0.337 | 0.155–0.726 | 0.0057 * |

| FreqUse_ACOnce per week | 0.382 | 0.203–0.712 | 0.0026 * |

| FreqUse_ACRarely | 0.132 | 0.058–0.297 | 0.0000 * |

| WTU_SS.L | 11.377 | 5.092–26.053 | 0.0000 * |

| WTU_SS.Q | 2.035 | 1.037–4.033 | 0.0398 * |

| WTU_SS.C | 1.090 | 0.649–1.841 | 0.7456 |

| WTU_SS^4 | 0.938 | 0.657–1.338 | 0.7226 |

| Preference_SSYes | 0.468 | 0.317–0.688 | 0.0001 * |

| Predictor | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CarTyp_MSYes | 0.678 | 0.380–1.202 | 0.1845 |

| CarTyp_SmulYes | 0.666 | 0.173–2.566 | 0.5510 |

| Preference_SSYes | 1.920 | 1.204–3.076 | 0.0063 * |

| DrivetrainYes, I would prefer electric cars | 1.838 | 1.109–3.062 | 0.0187 * |

| No_C | 0.737 | 0.547–0.990 | 0.0431 * |

| TbC> 20,000 km | 1.980 | 0.525–7.578 | 0.3146 |

| TbC0 | 3.141 | 0.336–34.023 | 0.3194 |

| TbC10,001–15,000 km | 0.662 | 0.359–1.217 | 0.1849 |

| TbC15,001–20,000 km | 0.414 | 0.157–1.083 | 0.0727 |

| TbC5001–10,000 km | 0.591 | 0.337–1.032 | 0.0648 |

| FreqUse_PTNever | 1.265 | 0.229–6.501 | 0.7825 |

| FreqUse_PTRarely | 1.489 | 0.693–3.216 | 0.3088 |

| FreqUse_PTSeveral times per month | 1.837 | 0.967–3.508 | 0.0640 |

| FreqUse_PTSeveral times per week | 1.479 | 0.798–2.745 | 0.2137 |

| WTU_AC.L | 8.564 | 3.732–20.094 | 0.0000 * |

| WTU_AC.Q | 1.437 | 0.684–3.010 | 0.3360 |

| WTU_AC.C | 1.129 | 0.634–2.016 | 0.6803 |

| WTU_AC^4 | 1.146 | 0.764–1.723 | 0.5104 |

| FreqUse_SSFew times per week | 0.368 | 0.139–0.975 | 0.0437 * |

| FreqUse_SSNever | 0.055 | 0.012–0.242 | 0.0001 * |

| FreqUse_SSOnce per month | 0.405 | 0.139–1.177 | 0.0966 |

| FreqUse_SSOnce per week | 0.335 | 0.126–0.890 | 0.0277 * |

| FreqUse_SSRarely | 0.257 | 0.091–0.724 | 0.0100 * |

| WTP_SS1–10% less than the costs of using your own car | 1.728 | 0.756–3.979 | 0.1961 |

| WTP_SS10–20% less than the costs of using your own car | 1.652 | 0.733–3.748 | 0.2272 |

| WTP_SS20–30% less than the costs of using your own car | 3.225 | 1.385–7.604 | 0.0069 * |

| WTP_SS30–40% less than the costs of using your own car | 3.475 | 1.231–9.906 | 0.0189 * |

| WTP_SSSame as the costs using your own car | 2.564 | 1.065–6.232 | 0.0364 * |

References

- Springer India-New Delhi. Automotive Revolution & Perspective Towards 2030. Auto. Tech. Rev. 2016, 5, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Rust, A.; Brunner, H.; Bachler, J.; Hirz, M. Potential for CO2 Emission Reduction in Future Passenger Car Fleet Scenarios in Europe. In Proceedings of the Resource Efficient Vehicles Conference (rev2021), Stockholm, Sweden, 14–16 June 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Raposo, M.; Ciuffo, B. The Future of Road Transport—Implications of Automated, Connected, Low-Carbon and Shared Mobility; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnert, F.; Stürmer, C.; Koster, A. Five Trends Transforming the Automotive Industry. 2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/automotive/assets/pwc-five-trends-transforming-the-automotive-industry.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Nguyen, T.T.; Mahringer, G.; Brunner, H.; Hirz, M.; Landschützer, C. Potential Pathways for Carbon Emission Reduction in Road Passenger and Freight Transport. In Proceedings of the 12th International Scientific Conference on Mobility and Transport (mobil.TUM 2022), Singapore, 5–7 April 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D.; Dai, D. Public Perceptions of Self-Driving Cars: The Case of Berkeley, California. In Proceedings of the 93rd Annual Meeting of the Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2014; p. 01503729. [Google Scholar]

- Thurner, T.; Fursov, K.; Nefedova, A. Early Adopters of New Transportation Technologies: Attitudes of Russia’s Population towards Car Sharing, the Electric Car and Autonomous Driving. Transp. Res. Part A 2022, 155, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Hirz, M. Effects of Automated Cars on CO2-Equivalent Emissions of European Passenger Car Fleet: A Life Cycle Perspective. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 79, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE International. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsalu, J.; Arffman, V.; Bellone, M.; Ellner, M.; Haapamäki, T.; Haavisto, N.; Josefson, E.; Ismailogullari, A.; Lee, B.; Madland, O.; et al. State of the Art of Automated Buses. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, R. Introducing Autonomous Buses and Taxis: Quantifying the Potential Benefits in Japanese Transportation Systems. Transp. Res. Part A 2019, 126, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.A.S.; de Salles Hue, N.P.M.; Berssaneti, F.T.; Quintanilha, J.A. An Overview of Shared Mobility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaksson, C.; Pongolini, M. Do We Really Consider Their Concerns? User Challenges with Electric Car Sharing. Mobilities 2023, 19, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, P.; Melo, S.; Rolim, C. Energy, Environmental and Mobility Impacts of Car-Sharing Systems: Empirical Results from Lisbon, Portugal. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 111, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansubuga, B.; Kowalkowski, C. Carsharing: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2021, 32, 55–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastjuk, I.; Herrenkind, B.; Marrone, M.; Brendel, A.; Kolbe, L. What Drives the Acceptance of Autonomous Driving? An Investigation of Acceptance Factors from an End-User’s Perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Orviska, M.; Hunady, J. People’s Attitudes to Autonomous Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A 2019, 121, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintersberger, S.; Azmat, M.; Kummer, S. Are We Ready to Ride Autonomous Vehicles? A Pilot Study on Austrian’s Consumer Perspective. Logistics 2019, 3, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennevik, E.M.; Dijk, M.; Arnfalk, P. How Do New Mobility Practices Emerge? A Comparative Analysis of Car-Sharing in Cities in Norway, Sweden, and the Netherlands. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 82, 102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhua, G.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Y. Acceptance of Free-Floating Car Sharing: A Decomposed Self-Efficacy-Based Value Adoption Model. Transp. Lett. 2022, 14, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, T.; Rose, G.; Johnson, M. “Don’t You Want the Dream?”: Psycho-Social Determinants of Car Share Adoption. Transp. Res. Part F 2021, 78, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtale, R.; Liao, F.; Rebalski, E. Transitional Behavioral Intention to Use Autonomous Electric Car-Sharing Services: Evidence from Four European Countries. Transp. Res. Part C 2022, 135, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Feng, T.; Timmermans, H.J.; Yao, B. Using Autonomous Vehicles or Shared Cars? Results of a Stated Choice Experiment. Transp. Res. Part C 2021, 128, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S.; de Winter, J.; Kyriakidis, M.; van Arem, B.; Happee, R. Acceptance of Driverless Vehicles: Results from a Large Cross-National Questionnaire Study. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 5382192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J. Public Opinion on Automated Driving: Results of an International Questionnaire among 5000 Respondents. Transp. Res. Part F 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.A.S.; Haustein, S. On Sceptics and Enthusiasts: What Are the Expectations towards Self-Driving Cars? Transp. Policy 2018, 66, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigeon, C.; Alauzet, A.; Paire-Ficout, L. Factors of Acceptability, Acceptance and Usage for Non-Rail Autonomous Public Transport Vehicles: A Systematic Review. Transp. Res. Part F 2021, 81, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, T. Recent Trends in the Public Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles: A Review. Vehicles 2025, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanou, F.P.; Vlahogianni, E.I.; Yannis, G.; Mitsaki, E. Humanizing Autonomous Vehicle Driving: Understanding, Modeling and Impact Assessment. Transp. Res. Part F 2022, 87, 477–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrao, G.; Lehtonen, E.; Innamaa, S. The gender gap in the acceptance of automated vehicles in Europe. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2024, 101, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Guo, Q.; Ren, F.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Willingness to Pay for Self-Driving Vehicles: Influences of Demographic and Psychological Factors. Transp. Res. Part C 2019, 100, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Kockelman, K. Forecasting Americans’ Long-Term Adoption of Connected and Autonomous Vehicle Technologies. Transp. Res. Part A 2017, 95, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.H.; Shyr, O.F.; Chen, T.S. Ageing and Mobility: Towards Age-Friendly Public Transport in Taiwan. In Planning for Greying Cities, 1st ed.; Stessa Chao, T.-Y., Ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2017; p. 192. ISBN 9781315442884. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, K.; van Lierop, D. How Will Older Adults Use Automated Vehicles? Assessing the Role of AVs in Overcoming Perceived Mobility Barriers. Transp. Res. Part A 2022, 133, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Chng, S.; Cheah, L. Understanding Acceptance of Shared Autonomous Vehicles among People with Different Mobility and Communication Needs. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjeret, F.; Bjorvatn, A.; Innamaa, S.; Lehtonen, E.; Malin, F.; Nordhoff, S.; Louw, T. Willingness to Pay for Conditional Automated Driving among Segments of Potential Buyers in Europe. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 8953109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, F.Y.; Currie, G.; Kamruzzaman, M. Understanding the value of autonomous vehicles—An empirical meta-synthesis. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 1058–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigolon, A.; Garritsen, K.; Geurs, K. Willingness to pay for shared mobility hubs: A stated choice joint-survey in four European cities. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schluter, J.; Weyer, J. Car Sharing as a Means to Raise Acceptance of Electric Vehicles: An Empirical Study on Regime Change in Automobility. Transp. Res. Part F 2019, 60, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartenì, A.; Cascetta, E.; de Luca, S. A Random Utility Model for Park & Carsharing Services and the Pure Preference for Electric Vehicles. Transp. Policy 2016, 48, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paundra, J.; Rook, L.; van Dalen, J.; Ketter, W. Preferences for Car Sharing Services: Effects of Instrumental Attributes and Psychological Ownership. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 53, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.K. Impact of Carsharing on the Mobility of Lower-Income Populations in California. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 24, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenegrachts, E.; Vanelslander, T.; Verhetsel, A.; Beckers, J. Analyzing shared mobility markets in Europe: A comparative analysis of shared mobility schemes across 311 European cities. J. Transp. Geogr. 2024, 118, 103918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, C.; Dong, X. Understanding the Characteristics of Car-Sharing Users and What Influences Their Usage Frequency. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haustein, S. What Role Does Free-Floating Car Sharing Play for Changes in Car Ownership? Evidence from Longitudinal Survey Data and Population Segments in Copenhagen. Travel Behav. Soc. 2021, 24, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julagasigorn, P.; Banomyong, R.; Grant, D.B.; Varadejsatitwong, P. What Encourages People to Carpool? A Conceptual Framework of Carpooling Psychological Factors and Research Propositions. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 12, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, N.; Yuen, K.F. Can Autonomy Level and Anthropomorphic Characteristics Affect Public Acceptance and Trust towards Shared Autonomous Vehicles? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 189, 122–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zheng, Z.; Whitehead, J.; Washington, S.; Perrons, R.K.; Page, L. Preference Heterogeneity in Mode Choice for Car-Sharing and Shared Automated Vehicles. Transp. Res. Part A 2020, 132, 633–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; So, K.K.F.; Hudson, S. Inside the Sharing Economy: Understanding Consumer Motivations behind the Adoption of Mobile Applications. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Understanding Consumers’ Willingness to Use Ride-Sharing Services: The Roles of Perceived Value and Perceived Risk. Transp. Res. Part C 2019, 105, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efthymiou, D.; Antoniou, C.; Waddell, P. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Vehicle Sharing Systems by Young Drivers. Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.Y.; Matsumoto, M.; Tahara, K.; Chinen, K.; Endo, H. Exploring Factors Affecting Car Sharing Use Intention in the Southeast-Asia Region: A Case Study in Java, Indonesia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Martin, E.; Hoffman-Stapleton, M. Shared Mobility and Urban Form Impacts: A Case Study of Peer-to-Peer (P2P) Carsharing in the US. J. Urban Des. 2021, 26, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, M.; Baltas, G.; Stan, V. Car Sharing Adoption Intention in Urban Areas: What Are the Key Sociodemographic Drivers? Transp. Res. Part A 2017, 101, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, K.; Piscicelli, L.; Boon, W.; Frenken, K. Different Business Models, Different Users? Uncovering the Motives and Characteristics of B2C and P2P Carsharing Adopters in The Netherlands. Transp. Res. Part D 2019, 73, 276–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaris, L.; Danielis, R. The Role for Carsharing in Medium to Small-Sized Towns and in Less-Densely Populated Areas. Transp. Res. Part A 2018, 115, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeVine, S.; Lee-Gosselin, M.; Sivakumar, A.; Polak, J. A New Approach to Predict the Market and Impacts of Round-Trip and Point-to-Point Carsharing Systems: Case Study of London. Transp. Res. Part D 2014, 32, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Shaheen, S. The Impact of Carsharing on Public Transit and Non-Motorized Travel: An Exploration of North American Carsharing Survey Data. Energies 2011, 4, 2094–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costain, C.; Ardron, C.; Habib, K.N. Synopsis of Users’ Behaviour of a Carsharing Program: A Case Study in Toronto. Transp. Res. Part A 2012, 46, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Kong, X.; Li, M.; Wang, J.; Shen, G.; Wang, X. VISOS: A Visual Interactive System for Spatial-Temporal Exploring Station Importance Based on Subway Data. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 42131–42141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Ko, J.; Park, Y. Factors Affecting Electric Vehicle Sharing Program Participants’ Attitudes about Car Ownership and Program Participation. Transp. Res. Part D 2015, 36, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, G.; Viegas, J.M. Carpooling and Carpool Clubs: Clarifying Concepts and Assessing Value Enhancement Possibilities Through a Stated Preference Web Survey in Lisbon, Portugal. Transp. Res. Part A 2011, 45, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Z.; Nie, Q.; Zhang, W. Research on Travel Behavior with Car Sharing Under Smart City Conditions. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 6693899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payre, W.; Cestac, J.; Delhomme, P. Intention to Use a Fully Automated Car: Attitudes and A Priori Acceptability. Transp. Res. Part F 2014, 27, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.; Ciari, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Comparing Car-Sharing Schemes in Switzerland: User Groups and Usage Patterns. Transp. Res. Part A 2017, 97, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoettle, B.; Sivak, M. Public Opinion About Self-Driving Vehicles in China, India, Japan, the U.S., the U.K. and Australia; Transportation Research Institute, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, S.; Worrall, C.; Talati, Z.; Fritschi, L.; Norman, R. Dimensions of Attitudes to Autonomous Vehicles. Urban Plan. Transp. Res. 2019, 7, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraedrich, E.; Cyganski, R.; Wolf, I.; Lenz, B. User Perspectives on Autonomous Driving: A Use-Case-Driven Study in Germany. Arbeitsberichte 2016, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, N.; Rüssmann, M.; Mei-Pochtler, A.; Dauner, T.; Komiya, S.; Mosquet, X.; Doubara, X. Self-Driving Vehicles, Robo-Taxis, and the Urban Mobility Revolution; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Kockelman, K. Opportunities for and Impacts of Carsharing: A Survey of the Austin, Texas Market. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2011, 5, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parab, S.; Bhalerao, S. Choosing Statistical Test. Int. J. Ayurveda Res. 2010, 1, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statista. Estimated Population of Selected European Countries in 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/685846/population-of-selected-european-countries/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Glenn, D.I. Determining Sample Size; University of Florida—IFAS Extension: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Medallia. CheckMarket. Available online: https://www.checkmarket.com/how-to-estimate-your-population-and-survey-sample-size/ (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Drew, J. How to Calculate Sample Size for a Survey. Available online: https://www.tenato.com/market-research/what-is-the-ideal-sample-size-for-a-survey/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- The World Bank. World Bank Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.ZS?locations=NO-IS-LI-CH-GB (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- The Global Economy. Percent Urban Population—EFTA. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/Percent_urban_population/EFTA/ (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Lagadic, M.; Verloes, A.; Louvet, N. Can Carsharing Services Be Profitable? A Critical Review of Established and Developing Business Models. Transp. Policy 2019, 77, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Objective and Location | Methods | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | AV Germany | Mixed: qualitative research, TAM and online survey (N = 316) | Attitude → Usage intention (+) Perceived usefulness → attitude (+) Perceived ease of use → attitude (+) Subjective norm → Perceived usefulness (+) Trust → Intention to use (+) Personal innovativeness → Perceived usefulness (+) Personal innovativeness → Perceived ease of use (+) Perceived relative advantage → Perceived usefulness (+) Perceived relative advantage → Attitude (+) Compatibility of AVs with mobility needs → Perceived usefulness (+), Attitude (+), Intention to use (+) Perceived enjoyment → Perceived ease of use (+) (Positive) price evaluation → Intention to use (+) |

| [17] | AV Europe | Regression analysis, factor analysis | Attitude to robots, individual self-interest → Attitude to AVs Age → Attitude (−) Male → Attitude (+) City residents → Attitude (+) High Education → Attitude (+) Accident rate → Attitude (+) |

| [18] | AV Austria | Online survey (N = 192), Spearman’s rank correlation and Mann–Whitney U test | Female → Concern (+) Automation level → Safety (+) Concern → WTU (−) Automation level → WTU (+) |

| [22] | ECS AECS France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain | Survey (N = 2154), The extended UTAUT and safety construct | ECS: Age → Behavioral intention to use (BI) (−) High education → BI (+) City size → BI (+) AECS: Female → BI (−) Age → BI (−) High income → BI (+) BI ECS → BI AECS (+) Impacts of psychological factors and socio-demographic characteristics differ across countries |

| [23] | AV, CS, SAV Dalian, China | The random utility theory, survey (N = 542) | Age (<50 years old) → Willingness to buy (WTB) AV (+) Income (>90,000 CNY/year) → WTB AV (+) Number of people in household (>1) → WTB AV (+) Number of cars in household (>0) → WTB AV (−) Driving experience → WTU AV (+) Male → WTU CS (+) Age → WTU CS (−) Income → WTU CS (−) Employment → WTU CS (−) Number of cars in household (>0) → WTU CS (−) |

| [36] | SAV Singapore | Online survey (N = 300), focus group (N = 53) | Attitude (+) Safety → Attitude (−) |

| [48] | SAV Singapore | Survey (N = 451), three-factor model, UTAUT model, trust theory, structural equation modeling | SAV anthropomorphism → Trust in SAVs (+) Human trust propensity → Trust in SAVs (+) Human trust propensity → Acceptance SAVs (+) SAV autonomy → Trust in SAVs (+) SAV autonomy → Acceptance SAVs (+) Effort expectancy → Trust in SAVs (+) Effort expectancy → Acceptance SAVs (+) Human-SAV facilitating condition → Acceptance SAVs (+) Social influence → Trust in SAVs (+) Social influence → Acceptance SAVs (+) Trust in SAVs → Acceptance SAVs (+) The effect of SAV anthropomorphism on Acceptance SAVs is mediated by Trust in SAVs The effect of human trust propensity on Acceptance SAVs is mediated by Trust in SAVs The effect of SAV autonomy on Acceptance SAVs is mediated by Trust in SAVs The effect of effort expectancy on Acceptance SAVs is mediated by Trust in SAVs |

| [7] | CS, EV, AV Russia | Survey (N = 1671), logistic regression, segmentation | Age → WTT (−) Driving license → WTT EV (+), WTT AC (−), WWT CS (−) Male → WTT AC (+), WTT EV (+), WTT CS (+) Female → WTT AC (−), WTT EV (−) City residents → WTT AC (+), WTT EV (+), WTT CS (+) Number of people in household → WTT CS (+), WTT AC (+) Higher education does not affect attitudes towards CS, EV, AV CS is attractive to all users regardless of income, education, gender |

| [27] | AV Denmark | Online survey (N = 3040), cluster analysis (k-means algorithm) | Enthusiasts: male, younger, metropolitan occupants Skeptics: older, non-metropolitan occupants Indifferent drivers: no cars, negative feelings towards driving Expected advantages of AVs and behavioral change are different among the various segments |

| [26] | AV Global | Online survey (N = 4886) | Income, driving frequency → WTP (+) Mileage → WTP (+) Current use of ACC (adaptive cruise control) → WTP (+) A wide spectrum of acceptance towards AVs 22% do not want to pay more for level 5 AVs 5% WTP more than 30,000 USD 33% perceive AVs as highly enjoyable 69% estimate AVs will reach 50% market share by 2050 A large share of users would not like to pay anything extra for AVs, eps. for higher automation levels Concerns about software hacking/misuse, legal issues, and safety |

| [32] | AV Tianjin and Xi’an, China | Surveys (N = 586 (Tianjin), N = 769 (Xi’an)) | Awareness of AVs → WTP (+) Age → WTP (−) Income → WTP (+) Education → WTP (+) Trust, perceived benefit → WTP (+) Perceived risk, dread → WTP (−) Participants with awareness of AVs have higher WTP and trust, also perceived higher benefits, lower risks and dread About 26% do not want to pay more for AVs |

| [24] | AV Global | Online survey (N = 7755), factor analysis | Perceived usefulness, intention to use, ease of use, pleasure, trust in AVs, mobility-related knowledge, thrill seeking, exert manual control, car-free preference, comfortable with technology → Attitude AVs Higher GDP → lower WTU Higher GDP → less supportive car-free atmosphere Higher GDP → less comfortable with technology Lower GDP → higher thrill seeking |

| [49] | CS, SAV Australia | Survey (N = 1500), Logit model | Household income → WTU CS (−), WTU SAV (+) Age → WTU CS (−), WTU SAV (−) Environmentally conscious → WTU CS (+) Household car ownership → WTU CS (−) Male → WTU CS (+) Female, Non-drivers → WTU SAV (−) Current travel mode → WTU CS Trip purposes → WTU CS |

| [19] | CS Oslo, Norway, Malmö, Sweden, Rotterdam, Netherlands | Interview (N = 58), workshops (3 half-day) | New digital technologies, regulation → business models and social aspect of mobility → acceptance CS Usage of private cars → WTU CS (−) EVs combined with CS → CS (+) |

| [20] | FFCS Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, China | Online survey (N = 318) | Economic value, functional value, comparative value, emotional value → Perceived value of FFCS Economic value is the greatest determinant of overall value perception Comparative value is vital: adoption of FFCS only when relative advantages can offset costs/risks of mode switching Functional value is not the main component in perceived value of FFCS Improvement in social value, epistemic value: not significant |

| [51] | RS China | Survey (N = 378, purely non-users), structural equation model | Perceived value → WTU RS (+) Perceived risk → WTU RS (−) Perceived risk moderates the effect of perceived value on WTU RS positively |

| [50] | RS Beijing, China | Survey (N = 314) | Self-efficacy → Perceived value → Behavioral intentions Functional value, emotional value, social value → Overall perceived value of RS Learning effort, risk perception are not significant perceived costs for RS users |

| [13] | ECS A small municipality in suburban area, Sweden | Interview (N = 11, participants of the CS trial) | Interrelated: Making the technology understandable and useful; Integrating carsharing in everyday practices; Negotiations and communications about the proper way to share a car. Highlighted: The environmental advantages of sharing; The social benefits and how it might enrich everyday life |

| [45] | CS Beijing, China | CS order data and users’ trajectory data, multi-factor influence model | Female → higher FCU than male Female → CS preference (+) Age → FCU (−) (main users 25–39 years old) Male → CS usage (+) Weekday → CS usage (+) Commute distance → CS user (−) Coupon to join CS → CS user (+) Travel distance and duration, Weekday usage, Station location → FCU |

| [21] | CS Melbourne, Australia | Theory of Planned Behavior, focus group (N = 5), semi-structed interview (N = 18) | Key motivators: cost saving, environment, convenience Other motivators: sharing with the community, reducing/avoiding car-related hassles (e.g., maintenance, parking), a desire to possess less Barriers: normative beliefs about car ownership, perceived difficulties in using CS (e.g., families with children), effort to plan, book and use CS |

| [46] | FFCS Copenhagen, Denmark | Surveys (2.5 years apart, N = 776 FFCS users, 720 non-users), multinomial regression | FFCS users → Reduction in car ownership (+), Changed household composition, private parking space, the initial number of cars in the household → Changed car ownership |

| [43] | CS California, US | Statistical data, structural equation model | CS membership enhances mobility for lower/higher-income households The effect of CS membership is significantly larger on lower-income households. |

| [29] | AV Global | Review of recent studies (2018–2024); synthesis of acceptance drivers | Trust → Acceptance (+) Perceived safety, cybersecurity → Acceptance (+) UI/UX clarity, transparency → Acceptance (+) Media/policy context → Attitudes and intentions Demographics (age, gender) → Mixed/Context-dependent |

| [31] | AV Europe; eight countries | Cross-country survey analysis; regression models; cross-level comparisons | Male → Acceptance (+) (heterogeneous across countries) Higher GDP per capita, Gender Equality Index → Larger gender gap Country effects (culture/policy) → Significant Overall acceptance varies strongly by national context |

| [37] | AV Europe | Online stated-preference survey; segmentation; WTP estimation | Perceived usefulness, trust → WTP (+) Heterogeneous segments: some high WTP, others low/zero Safety and cost perceptions → WTP (±) Not all willing to pay a premium despite positive attitudes |

| [38] | AV Global | Quantitative synthesis/meta-review of empirical studies (value, costs, VOT) | Private AVs → Lower perceived value-of-time (VOT) (on average) Benefits/costs vary by context and study design Significant heterogeneity by user characteristics Evidence base growing but uneven across settings |

| [39] | SMS Europe; 4 cities | Stated-choice joint survey; WTP estimation for hub attributes | Physical integration (PT within walking distance, placemaking) → WTP (+) Digital/platform integration → WTP (0/−) Implication: back-end services may need public/operational funding Design features can shift acceptance and usage |

| Code | Hypothesis | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | WTU ACs and WTU SMSs have a positive connection | [7,22,23] |

| H2 | Regarding ACs, WTU has a connection to WTP | [32] |

| H3 | Regarding SMSs, WTU has a connection to WTP | [23] |

| H4a | People considering ACs useful and easy to use are more willing to use AC | [16,24] |

| H4b | People considering SMSs useful and easy to use are more willing to use SMS | [20,51] |

| H5 | People who prefer to use the combination of SMSs and PT over their private vehicle have higher acceptance of SMSs than people who prefer their private vehicle | [45,46] |

| Country | WTU/Would Take a Ride (% of Sample) | Unwillingness to Pay More (% of Sample) |

|---|---|---|

| Global | 58% [70] 56% [26] About 50% [33,65] | 22% [26] |

| China | 75% [70] | 22% [67] 26% [32] |

| France | 58% [70] | - |

| Germany | 44% [70] | - |

| India | 85% [70] | 30% [67] |

| Japan | 36% [70] | 68% [67] |

| Netherlands | 41% [70] | - |

| Singapore | 62% [70] | - |

| UAE | 70% [70] | - |

| UK | 49% [70] | 60% [67] |

| US | 52% [70] | 59% [33] 55% [67] |

| Australia | - | 55% [67] |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency | Percentage | WTU_AC | WTU_SMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 141 | 48.8% | 28.4% | 17.0% |

| Female | 146 | 50.5% | 21.9% | 24.7% | |

| Others | 2 | 0.7% | 100.0% | 50.0% | |

| Living area | City | 190 | 65.7% | 27.9% | 23.2% |

| Suburb | 58 | 20.1% | 17.2% | 17.2% | |

| Countryside | 41 | 14.2% | 26.8% | 17.1% | |

| Age (years old) | <18 | 1 | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 18–24 | 101 | 34.9% | 23.8% | 20.8% | |

| 25–34 | 138 | 47.8% | 29.0% | 22.5% | |

| 35–44 | 36 | 12.5% | 19.4% | 13.9% | |

| 45–54 | 8 | 2.8% | 37.5% | 50.0% | |

| 55–64 | 5 | 1.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Driving license | Yes | 245 | 84.8% | 26.1% | 18.4% |

| No | 44 | 15.2% | 22.7% | 36.4% | |

| Car accident experience | Yes | 140 | 48.4% | 26.4% | 15.7% |

| No | 149 | 51.6% | 24.8% | 26.2% | |

| Highest education | High school diploma | 61 | 21.1% | 21.3% | 19.7% |

| Completed higher education studies | 216 | 74.7% | 26.9% | 21.3% | |

| Pupil, student, apprentice | 12 | 4.2% | 25.0% | 25.0% | |

| Physical disadvantages | Yes | 51 | 17.6% | 19.6% | 9.8% |

| No | 238 | 82.4% | 26.9% | 23.5% | |

| Commute distance (km) | <5 | 117 | 40.5% | 31.6% | 29.1% |

| 5–10 | 106 | 36.7% | 24.5% | 17.0% | |

| 10–20 | 36 | 12.5% | 16.7% | 16.7% | |

| >20 | 30 | 10.4% | 16.7% | 10.0% | |

| Number of people in a household | 1 | 39 | 13.5% | 15.4% | 33.3% |

| 2 | 71 | 24.6% | 31.0% | 16.9% | |

| 3 | 84 | 29.1% | 33.3% | 25.0% | |

| 4 | 66 | 22.8% | 15.2% | 13.6% | |

| 5 | 22 | 7.6% | 31.8% | 18.2% | |

| >5 | 7 | 2.4% | 14.3% | 28.6% | |

| Number of cars in a household | 0 | 55 | 19.1% | 21.8% | 41.8% |

| 1 | 119 | 41.3% | 27.7% | 24.4% | |

| 2 | 77 | 26.7% | 26.0% | 10.4% | |

| 3 | 29 | 10.1% | 31.0% | 3.4% | |

| >3 | 8 | 2.8% | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| Car mileage/year (km) | 0 | 5 | 0.0% | 20.0% | 40.0% |

| <5000 | 87 | 30.3% | 23.6% | 39.3% | |

| 5001–10,000 | 95 | 33.1% | 27.4% | 13.7% | |

| 10,001–15,000 | 65 | 22.6% | 20.0% | 12.3% | |

| 15,001–20,000 | 22 | 7.7% | 40.9% | 0.0% | |

| >20,000 | 13 | 4.5% | 30.8% | 23.1% | |

| Frequency usage of PT | Daily | 45 | 15.6% | 26.7% | 17.8% |

| Several times per week | 93 | 32.2% | 23.7% | 31.2% | |

| Several times per month | 85 | 29.4% | 22.4% | 17.6% | |

| Rarely | 57 | 19.7% | 29.8% | 15.8% | |

| Never | 9 | 3.1% | 44.4% | 0.0% | |

| Mobility costs (incl. car-related expenses) (% of income) | 1–5% | 91 | 31.5% | 22.0% | 24.2% |

| 5–10% | 133 | 46.0% | 25.6% | 21.8% | |

| 10–15% | 49 | 17.0% | 36.7% | 16.3% | |

| 15–20% | 14 | 4.8% | 7.1% | 14.3% | |

| >20% | 2 | 0.7% | 50.0% | 0.0% |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency | Percentage | WTU_AC | WTU_SMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge of AC | No idea | 8 | 2.8% | 12.5% | - |

| Aware, little knowledge | 177 | 61.2% | 17.5% | - | |

| Know a lot | 88 | 30.4% | 39.8% | - | |

| Study or research about | 15 | 5.2% | 35.7% | - | |

| Develop | 1 | 0.3% | 100.0% | - | |

| No experience | 25 | 8.7% | - | 8.0% | |

| Experience with SMS | Car rental (CR) | 151 | 37.7% | - | 23.2% |

| Car sharing (CS) | 111 | 27.7% | - | 28.8% | |

| Carpooling (CP) | 77 | 19.2% | - | 36.4% | |

| Ride hailing (RH) | 62 | 15.5% | - | 40.3% |

| Area | WTU_AC | WTU_SMS | WTP the Same as a Normal/Private Car | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| For AC | For SMS | |||

| The studied EU region | 25.6% | 21.1% | 22.5% | 17.0% |

| Austria | 31.7% | 11.0% | 34.1% | 18.3% |

| UK | 22.9% | 25.0% | 27.1% | 27.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.T.; Ratz, F.; Hirz, M. Acceptance of Automated Cars and Shared Mobility Services: Towards a Holistic Analysis for Sustainable Mobility Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219610

Nguyen TT, Ratz F, Hirz M. Acceptance of Automated Cars and Shared Mobility Services: Towards a Holistic Analysis for Sustainable Mobility Systems. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219610

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Thu Trang, Florian Ratz, and Mario Hirz. 2025. "Acceptance of Automated Cars and Shared Mobility Services: Towards a Holistic Analysis for Sustainable Mobility Systems" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219610

APA StyleNguyen, T. T., Ratz, F., & Hirz, M. (2025). Acceptance of Automated Cars and Shared Mobility Services: Towards a Holistic Analysis for Sustainable Mobility Systems. Sustainability, 17(21), 9610. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219610