Abstract

As the EU is funding collective self-consumption, European research focuses on legal, technical, economic and social aspects of energy communities. In this study we draw insight from the Portuguese scholars and recent developments to promote a better understanding about the rollout guidelines for energy communities in the North of Portugal and neighbor Galician province of Ourense in Spain. The project COMENERG for the energy transition has been playing active roles in Galicia and Portugal, with the Portuguese municipality of Ponte da Barca in participation by co-steering. A pilot project portfolio collected for benchmarking, as well as engagement data and cost/revenue streams common to eight business models, are gathered to serve as policy support for the energy transition office established in the Galician city of Ourense. The roles and barriers to overcome before and after this project finalizes are analyzed, and it appears critical to develop the demonstration pilot landmark, as well to preview the contingencies ahead for successful implementation of the renewable energy communities in this Euroregion.

1. Introduction

It was by the early twentieth century, after the centralized utilities abandoned the less attractive lands to make their business, that the first energy communities (ECs) were forged to give villagers social access to electricity by initiative of local authorities and civic cooperatives [1]. Since the legal issue of the fourth Energy Package (2018–2019)—Clean Energy for All Europeans, this early business concept was recovered. The Directive (EU) 2018/2001—known as the Renewable Energy Directive (RED II)—defining and mandating support for renewable energy communities (CERs), and the Directive (EU) 2019/944—also known as the Internal Electricity Market Directive (IEMD), defining Citizen Energy Communities (CCEs in Portuguese), promoting their market access and participation, were fully transposed in the EU countries. There are now 1.5 million citizens who actively participate in the energy transition in the EU, which was transposed by Member States in different ways. In Portugal, by the Decree-Law No. 15/2022 which gave finally legal harmonization to the National Electricity System (SEN) [2]. The Portuguese broad concept of collective self-consumption (ACC) represents the scope of energy communities that we will discuss and which is becoming, in many European regions, a major evolution from a more centralized model to a decentralized approach. ACC either defined preferentially by CER or CCE is demonstrating local participation grounded in democracy and response to climate challenges, with renewable energies and technological efficiency [3,4]. In Portugal and decurrent from legal status, a microgrid can be used in a Citizen Energy Community (CCE) but not in a renewable energy community (CER), despite both being part of collective self-consumption (ACC). Detailed comments on this new legal regime in Portugal have also been published [5]. To facilitate the understanding and application of these new rules, a practical legislative guide on self-consumption and CERs has been made available by ADENE and the DGEG [6]. More recently, the framework has been further amended by Decree-Law No. 99/2024 to adapt to the evolution of the sector [7]. The Energy Services Regulatory Entity (ERSE) has also played principal normative role. It has published Directive No. 12/2022, which defines the general conditions of contracts for the use of networks for self-consumption [8], as well as the Self-Consumption Regulation (RAC) No. 815/2023 [9] and other regulations of the SEN like last-resort prices and grid access tariffs [10]. To encourage innovation, ERSE has approved a rollout of pilot projects under the regulatory framework [11]. In addition, the strategic Portuguese National Energy and Climate Plan 2030 (PNEC 2030) defined the national ambitions for this decade [12], recognizing the growing role of the energy communities.

CERs are seen as a multiplier of energy justice, as shown by a study of 71 European cases and also as a part of a co-created social future [13,14]. In Portugal, the exemplary setup of the cooperative CER in Telheiras/Lumiar aids to make the process of CER open to the broad population [15]. However, their implementation is not without obstacles. Studies have identified barriers and impacts related to their deployment [16] and highlighted gaps and delays in the application of European frameworks in several countries, including Portugal [17]. The issue of the responsibility of intermediaries in large-scale deployment was also analyzed [18].

At the economic level, the viability of the business models, challenges, and trends was also explored [19]. Comparative techno-economic analyses, for example, between Portugal and Italy, have provided a better understanding of self-consumption patterns [20,21], while Portuguese case studies have focused on specific models such as wind/solar energy communities [22,23]. Optimized energy sharing is fundamental to raise the attractiveness of the investment to local producers, consumers, and partners. Many management platforms are being tested for this goal as well as monitoring systems [24,25]. Guides have been published to support citizens and organizations in creating communities, such as the “Energy for Citizens” guide [26] and another practical guide inspired by the example of the Telheiras/Lumiar CER [27]. A list of EC promoters is available to the public [28]. Self-consumption macrostatistics are available for Portugal [29], yet neighboring Spain provides much more detail through a national observatory of EC [30].

In the light of the ongoing cross-border project COMENERG for the local replication of energy communities in Alto Minho (PT) and Ourense (ES), a new municipality for the Portuguese pilot project has been indicated to the project’s consortium by the intermunicipal community. As part of the involved academics in the projects, our research objective is to provide a snapshot of Portuguese and Galician implementation of renewable energy communities, for Alto Minho and Ourense. We discuss the results of our materials in the light of the roles that Ponte da Barca municipality as to play to rollout the energy communities with cross-border synergies. We finally direct our conclusions toward a synthesis of the discussion with a policy recommendation for the municipal policymakers and the energy transition support office that is being supported.

2. Materials and Methods

Science documents.

Our research started to use the Portuguese science databases Library of Knowledge (b-ON) and Portuguese Open Access Science Repository (RCAAP) where we found the complete work of Portuguese universities and other countries with a focus on the Portuguese written manuscripts both not peer-reviewed and peer-reviewed, most times disregarded by scholars from other non-Portuguese-speaking countries. Secondly, we looked in SCOPUS and Web of Science. The exact query of keywords differed. We also used backwards chaining to find additional relevant documents for our research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Keyword blocks for this study.

Legal documents. We used the Google search engine and looked for the Portuguese keyword blocks: (comunidade* de energia) E legislação. We collected the main legal documents from the study of the contents available the legal authorities’ websites.

Benchmarking. We drew significant data from the ERSE pilot studies by compiling information available in their respective webpages and completed the data through phone and email requests, sometimes through our own calculation for the specific conditions of the pilot with the missing data.

Ponte da Barca characterization. We used the results of COMENERG and from the projects where the COMENERG partners participated before as a standard of good practices, plus the previous knowledge of the involvement of Ponte da Barca in the Covenant of Mayors and CIM Alto Minho strategic plans, as our main sources of information.

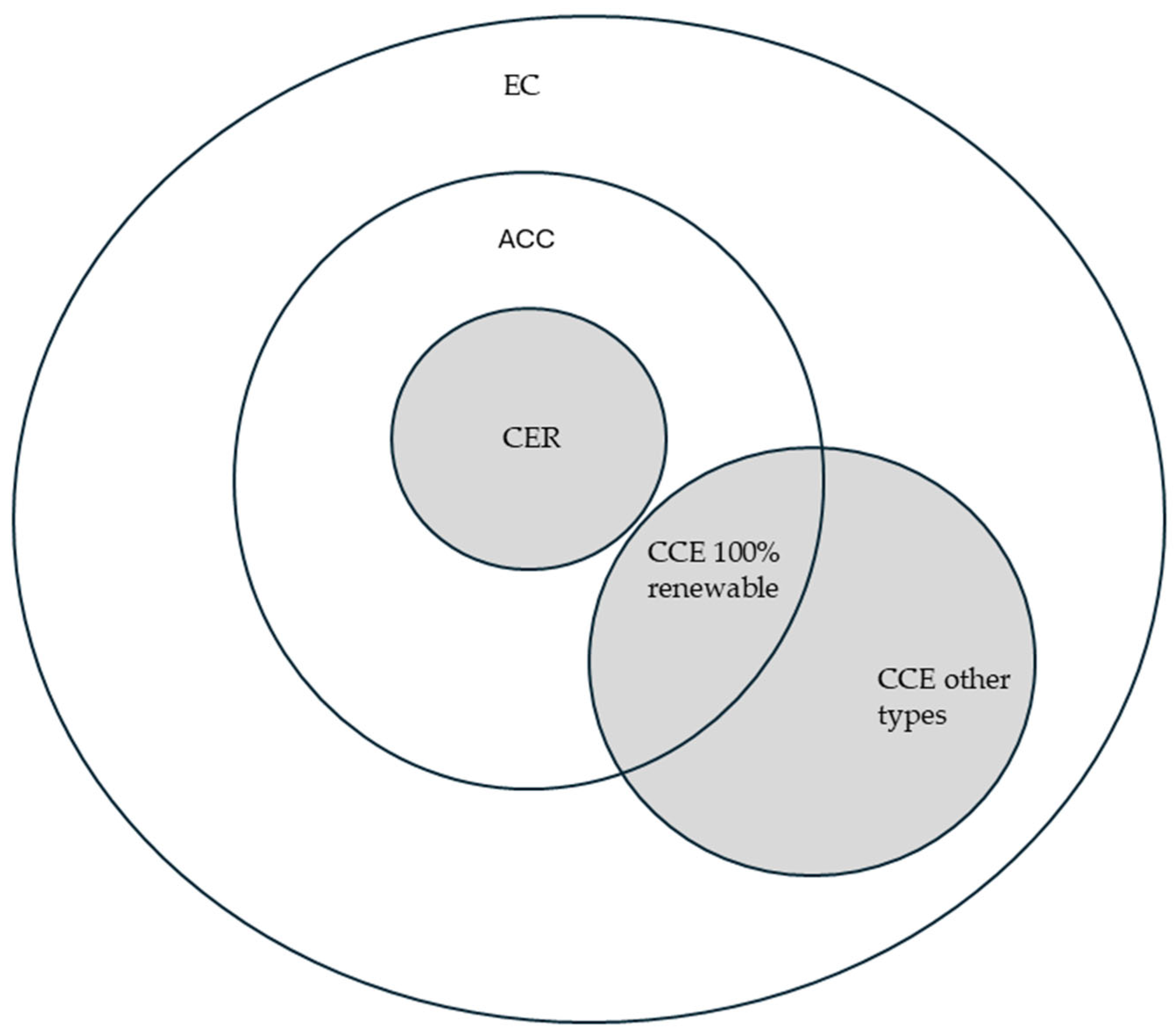

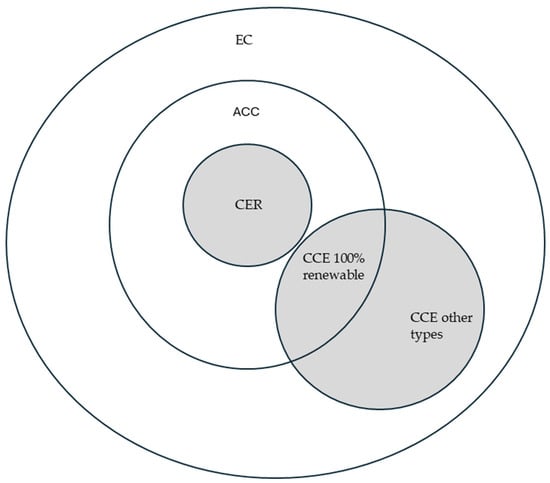

Materials. ACC, CER and CCE Definition. The current EC models were fully transposed to the Portuguese normative from the REDII and IEMDs. Both are sub-types of collective self-consumption (ACC), in contrast with individual self-consumption (ACI). All ACC must not have the distributed energy generation as this primary economic activity. ACC can be held accountable directly to a collective person. A CER or a CCE both apply to that accountability, with very few differences. Their common aim is to not reclaim financial profit but instead to reap environmental, economic and social benefits for the EC. CER is a collective person with autonomy rights and not for profit objectives. Its participants can be public or private and adhere open and voluntarily as members, associates, or shareholders. Their eligibility arises by proximity criterion to UPACs held by them or if they are active on renewable energy projects of that CER. CERs are characterized by a cumulative set of conditions for their support in terms of public funding, contracting, procedure simplification, among other things [16]. CCE shares most of the conditions with CER, except notably that geographic proximity is not necessary, the grid may be private, and non-renewable energies may be used (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Framework of energy community types. Source: own study. EC—energy community (with and without self-consumption, renewable and non-renewable); ACC—collective self-consumption (white, legally represented by an individual person; gray, legally represented by a collective person); CER—renewable energy community—a legal collective person for an ACC with connection to public grid only and other specific rules); CCE—Citizen Energy Collective—a legal collective person for an ACC that shares all rules of CER. CCE also allows private grids and non-renewables. Note: in energy communities more legal types of collective personality exist.

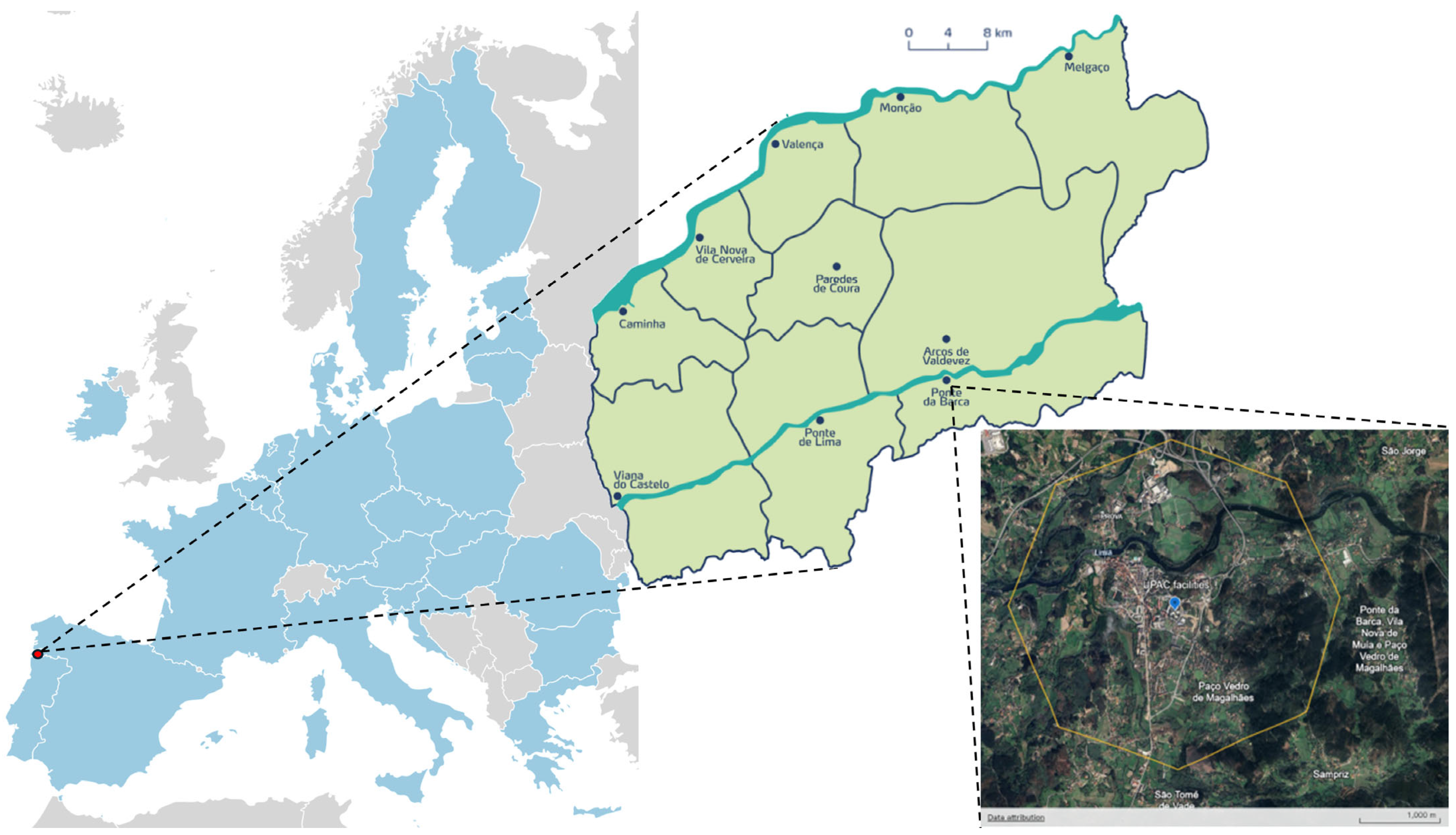

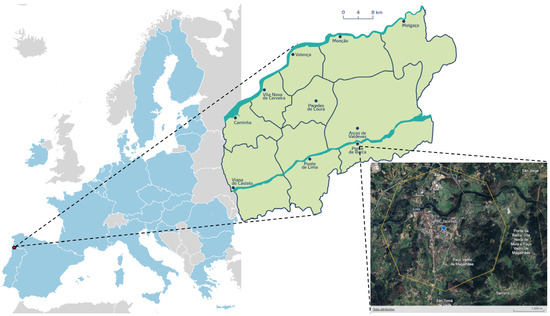

Ponte da Barca is one of the ten counties forming the NUTS 3 Alto Minho region, with an area of 182.1 km2, total population of 11,210, and population density of 61 people/km2). About 70% of the county remains inside the Parque Nacional da Peneda-Gerês, the most emblematic Portuguese protected area. The pilot project location was chosen close to the town of Ponte da Barca (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographical position of Alto Minho, Ponte da Barca and the EC pilot project. Source: own study. The red dot shows the localization of the ten municipalities in Alto Minho (green image) relative to the EU.

The capital town of Ponte da Barca has an area of 8.84 km2 and a population of 4192 with a density of 474 people/km2. The estimated number of families is 1676 [31,32]. The population decrease in Alto Minho has been preoccupant between 2011 and 2021, an average decrease of −6.72% and of −8.3% for Ponte da Barca. A retention of the inhabitants becomes urgent to maintain the territorial identification as traditionally built by centuries. The projections until 2050 show aggravation scenarios (Table 2).

Table 2.

Population scenarios in Ponte da Barca. Source: Ref. [31].

The territory is occupied by multi-family residential buildings in the town center where a pilot shared energy community will be tested. The energy communities are a tool for resilience. In 2019, the share of the municipal and service buildings on the total electricity consumption raised was 38%, residential buildings was 49%, and industry was to 7%. The average electricity consumption per family was 5.21 MWh/y (2024).

The energy transition with ACC is only beginning to be disseminated in Portugal, as almost every UPAC (self-consumption production unit) is for individual self-consumption. In the region of Alto Minho, the number of people divided by the number of UPAC is 34 people/UPAC. Almost 100% of existing UPAC belong to the capacity 0–30 kWp. The average power capacity per UPAC is 6.5 kWp (Table 3). The Energy Regulator Authority (ERSE) opened a rollout for testing pilots of energy communities with different types of business models. All cover various types of users and sectors (housing, companies, public institutions). Production is based on renewable sources but only solar photovoltaics. The essential objective is to test the allocation coefficients for the energy-sharing rules. The power capacity ranges from 40 to 347 kWp, and the kWh/kWp annual yield varies from 1415 to 1823. The number of UPAC assembled for collective self-consumption starts from 2 to 39 units. Projects offer storage solutions for several purposes as shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Alto Minho status for PV Distributed Generation in 2025. The ten municipalities are represented here, and the one were the pilot project will occur, Ponte da Barca, is in bold. Source: own study.

Table 4.

Some metrics of the pilots approved by ERSE to test advanced energy-sharing algorithms. Source: own study.

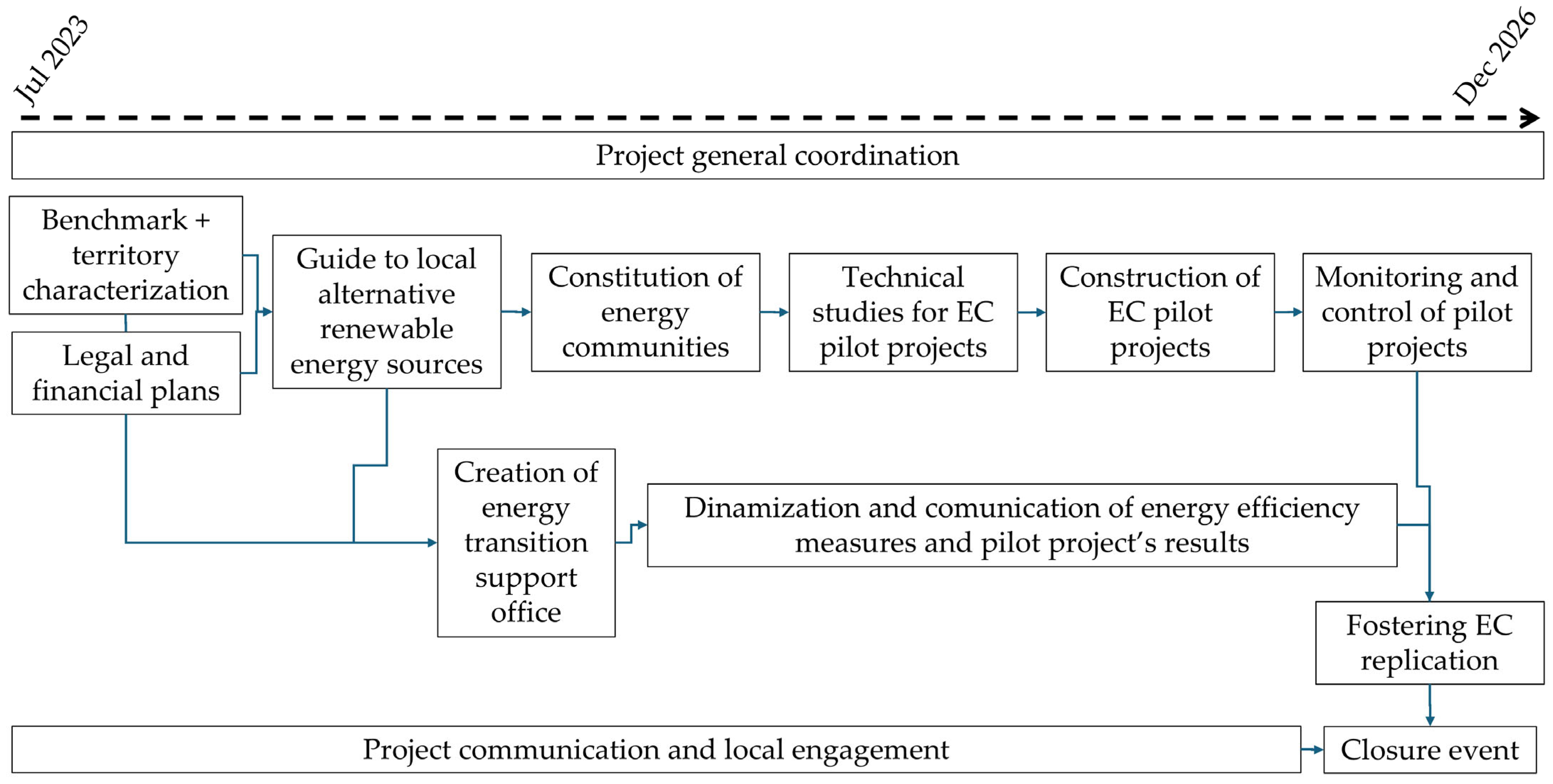

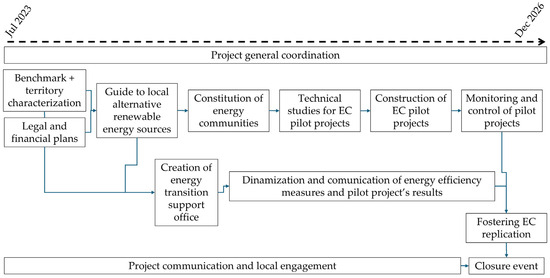

The “Cross-border energy community for the transition to energy autonomy and sustainability of the Raia localities” is an INTERREG VI-A (POCTEP) project with the name COMENERG. Spanish NUTS2 Galicia, represented by NUTS3 Ourense, and the Portuguese NUTS2 Norte, represented by NUTS3 Alto Minho are working together during 2023–2026 [33]. The demographic decrease in towns and villages is seen as the driver for implementing energy communities, particularly in the inner parts of the regions. The use of decentralized renewable energy production, lowering energy losses, and economic efficiencies are necessary to improve conditions for the population. PV generation is essential to include, but other renewable energy sources will be studied. A fair business model should be found. Each regional area of both countries is working on the same workflow in parallel on the pilot project and a common support office for the energy transition (Figure 3). The regional administrations, energy agencies and universities will demonstrate these solutions [33]. The energy transition support office is a key component to gather all the project findings and benefit the local communities from both regions.

Figure 3.

Time and workflow approved for COMENERG project. Source: own study.

3. Results and Discussion

The expansion of energy community business models (ECBMs) across Europe has been gaining momentum due to their potential to democratize energy access, enhance local sustainability, and reduce dependence on centralized utilities. According to Ref. [19], eight different archetypes of ECBM emerged in Europe: energy cooperatives, community prosumerism, collective generation, third party-sponsored BM, community flexibility aggregation, community Energy Service Company (ESCO), e-mobility cooperatives, and local energy markets. All these archetypes have the potential to be applied to the energy communities (Table 5).

Table 5.

Grouping of energy community business models from [19]. Source: own study.

The legal, economic, social and technical details are fully intertwined in every item of cost and revenue stream, which tend to be analog to all ECBMs. Therefore, we follow this integrated analogy to focus on the practical form that serves simultaneously as a policy recommendation, and, therefore, we decided to use an integrated analysis base, which we discuss in this manuscript, sorting them by cost/revenue item as a list. The cost structure and revenue streams tend to share a similar checklist [19].

Technology and Infrastructure Items. Energy production equipment, batteries, and ICT infrastructure—are important costs, as well as land purchase or rental and interest in financing the land agreement, and depreciation of physical assets over time. This situation is exacerbated by the long investment payback periods and limited access to consistent sources of financing throughout the project’s lifetime. These factors deter private investors and can make projects appear financially unattractive without supportive financing frameworks. Cost for physical assets of facilities >1 MW is about EUR 150/kW (Community Solar Farm of 5 MW close to Évora Historic Center), and, for facilities of the range 100 kW, it is ten times the cost (Évora Historic Center) [34].

As the COMENERG project is ongoing, pilot technology and assembly of physical assets also benefit from co-funding. Also, in the project the land expenditure is not cost, as the municipality gives the land for a long-term agreement between the community members.

For the acquisition and installation of technology, the EU provides subsidies and government incentives granted by the Portuguese government, especially those aimed at promoting the adoption of renewable energies. The Portuguese Environmental Fund had five call windows opened during 2024. In comparison with the actual small-scale distributed generation capacity of 1.3 MW in Alto Minho, the fund aimed to subsidize 93 MW distributed generation of ACC and CER at a national level to be operational until 2025T4. The Spanish institute for energy saving and diversification (IDEA) managed six funding rounds between 2022 and 2024 from the “CE IMPLEMENTA” fund. Besides national funding, Spanish provinces published additional funding opportunities (Xunta de Galicia).

Energy communities depend on robust ICT infrastructure, real-time metering, and automated control systems. In Portugal, the major Portuguese distributed generation operator, E-Redes, covering 99.5% of the territory, develops robust algorithms for monitoring and control optimization. The interoperability, data security, and communication technologies raises both costs and implementation complexity. While blockchain promises decentralized trading, its energy intensity and scalability remain unresolved concerns. In contrast, simpler self-consumption cooperatives face fewer technological demands and are less constrained by this barrier. Ponte da Barca will delegate this job on teamwork derived from COMENERG partner “CITIN—(Industrial Technology Interface Center—IPVC), assuming the further exploration of more than one algorithm, if possible, in the pilot. Legal ERSE regulations allow hierarchical and dynamic sharing rules, but theoretical models remain contradictory for decision making because of a lack of stability. Only the algorithms with fixed and proportional have the guarantee of application. Advanced sharing rules will augment the responsibilities of energy communities’ governance in the business models where prosumers and consumers must share decision power. The technical barriers to energy sharing are also being overcome by the COMENERG project. The IPVC institute CITIN has already developed an experimental pilot of the monitoring and control system of the local EC. This is the phase where we will test it in real-time pilot case studies. This is clearly an advantage as it was tailored by local academia within the project budget. The result of this technological development will be a tool for the energy transition office in Ourense to disseminate in all the local ECs, as it was benchmarked for maximum efficiency within a medium-term time span.

Energy trade cost and revenue item. Significant costs faced by energy communities come by contracting with companies for the electricity supply, to give course to their energy surplus, and for accessing the energy grid. Although the sale of surplus energy from entrepreneur members to other community members and the provision of energy efficiency (EE) services and e-mobility solutions is a potential revenue from the ACC, local energy markets did not appear in Portugal or Spain yet, so ECs have to turn towards ESCOs or to last-resort traders, which involves a necessary commercial agreement between the parties. The elements of the contract with third parties are crucial to determine the monthly savings for the prosuming and the consuming agents [35].

Several ERSE pilot projects involve e-vehicle charging and energy storage with e-vehicle batteries. Demand-side management locally could well justify the scalability of ACC by shared citizen investment or ESCO-led cost support and flexibility services such as e-vehicle sharing or centralized storage units. While ACC may enhance local grid efficiency and reliability, it poses a challenge to existing market structures by also creating operational disturbances (e.g., voltage imbalances) and lead to tariff inequities. Many existing ECBMs find themselves struggling with newly emerging national regulations. Cogeneration, wave energy and electric mobility are out of scope of the SEN legal framework. Complexity of authorizations increases with capacity of generation. In ACC, UPAC size must be fitted to collective consumption to minimize energy surplus. This landscape presents another hurdle to the revenue stream from energy trade. In Portugal no pilot projects of ERSE are licensed yet as CER up to now. Only 12% of CER in Spain are operational, principally due to delays in project dissemination and bureaucratic obstacles. Regulatory uncertainty affects investor confidence and operational continuity across all ECBM archetypes. In practice, the ACC cannot manage their own distribution networks or offer grid services—with the role of aggregators, distribution-level energy cooperatives, or multi-service community energy companies.

Community steering cost and decision making. Community members must endorse their legal duties. The legal organization that they will adopt is a long-term decision, as the PV equipment lifetime is between 25 and 35 years. An informal way to start an EC can be a good way to build trust and responsibility among members of the future legal community. In the island of Culatra (NUTS2 Algarve), the citizens started to develop collective action assuming their responsibilities in the energy consumption by mid-2019, initiating a path towards a cooperative with energy sharing formed in September 2022. Legal ownership of an ACC can be individual (condominium managers), a third-party entity offering the procurement of that ownership (EGAC), or the collective of participants in the EC (CER or CEC). If the ACC constitution is CER or CCE, then legal representatives are all the members of the CER or CEC, unless they contract their representation with an EGAC. The designated representative of ACC endorses the practice of the operational management of the current activity, including managing the internal grid, when existing, the rapport with the online platform of the legal authorities and licensing, the connection to the public service electric network and the liaison with the due operators, namely, in the matters of production sharing and its respective coefficients, and, when applied, the commercial behavior to adopt with the energy surplus, as compelled by their self-consumption collective. This representative must also communicate to the general directorate of energy and geology (DGEG) the internal rules of the EC, for up to 3 months after receiving the operation certificate. The internal rules will contain the requirements for access by new members and withdrawal by existing participants, the required decision-making majorities, the way in which the electricity produced for self-consumption is shared and the due tariffs paid, as well as the destination of self-consumption surpluses and the commercial relations policy to be adopted and, where appropriate, the application of the respective revenue. The support of day-to-day functioning of the EC adds costs for staff wages, operation and maintenance activities, and administrative or marketing tasks. This may retract engagement for EC responsibilities.

A lack of awareness of duties, resistance to change, or skepticism about renewable technologies may also lead to poor participation rates. Dynamic management of EC is essential to boost engagement by its members and willingness to invest. Initiatives also often depend on volunteers for their initial momentum, yet engagement tends to decline over time. Many ECBMs, especially those rooted in local, grassroots initiatives, depend on community involvement and trust. Some BMs allow the sale of ownership shares, which can be a source of revenue if the transaction adds value to the EC wealth, and promotes membership turnover. Sometimes geographic proximity presents a hurdle to that form of leaving the EC so that the establishment of a CCE would be more adequate. Sometimes the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) effect, where communities resist local infrastructure development, further complicates deployment.

Ponte da Barca should draw upon the resources of the energy transition support office in Ourense to promote the necessary support to members of the energy community.

The associative model in Galicia have opted to build 19 CER in the region, and the CER are legal embodied as an association (78.9%) or as a cooperative (21.1%). These would also be possible in Portugal as well as other figures, keeping in mind that the financial profit cannot be the aim of the EC. Galician CER are participated by citizen members (95%), municipalities (45%), local commerce (42%), companies from industrial parks (28%) and civil society organizations (28%). Purpose is also a key factor in the ECBM choice. For instance, energy poverty is the prism most regard for the constitution of CER is Galicia (32% of CER have this aim in their statutes).

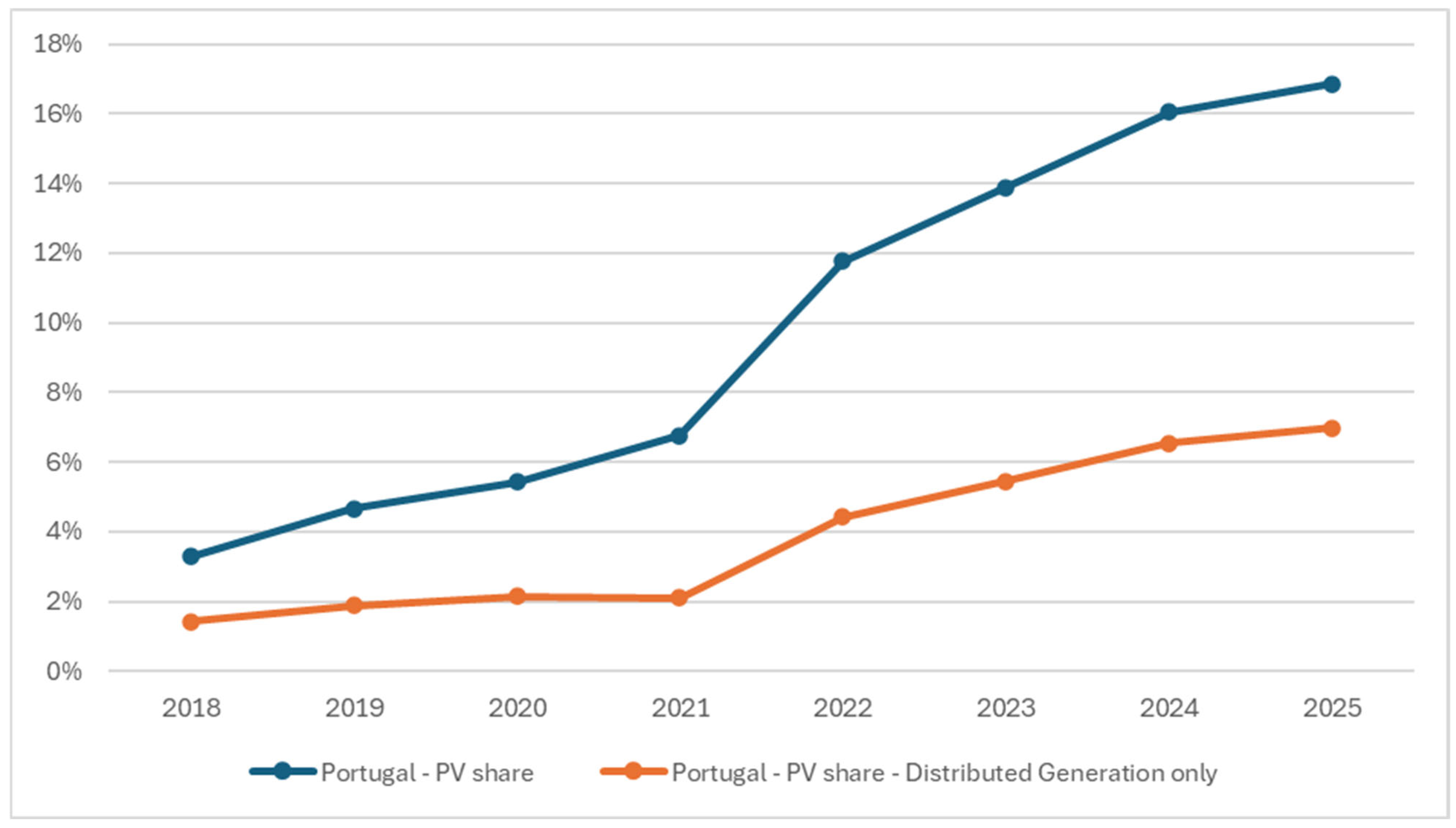

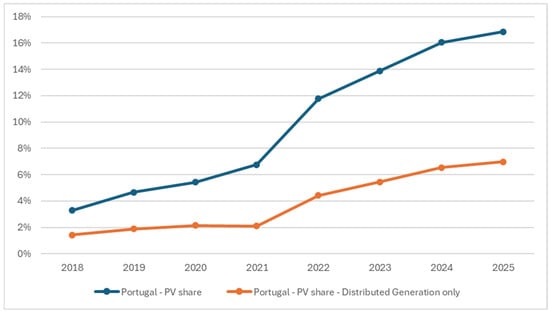

Policy communication for the energy transition. The last officially published data from renewable energy production of Alto Minho dates to 2018: 2692 GWh/y produced by energy utilities from hydro, wind and biomass centrals and no solar energy. Currently, energy utilities are not building solar centrals in the region. When compared to Alto Minho totals, the PV capacity of distributed generation is 1.3 MW—assuming that PSH is of 1650 kWh/m2/year for this region, and performance ratio is 0.8—which represents a minuscule contribution (0.064%). Nevertheless, the distributed generation, in particular PV, continues to grow overall in Portugal, in Alto Minho, and in other regions of Portugal, and central PV utilities are growing even faster (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Share of solar PV for Portuguese renewable energy production. Total PV and PV from DG only. Source: own study.

Alto Minho is investing in other major centralized renewable energy sources such as wind and hydro. Despite this, the effort to raise the small-scale distributed generation must continue for several reasons. Since a few years until now, European funding is available. In 2022, an Alto Minho report claimed that distributed generation with CER or CCE is a regional SWOT opportunity to reduce the territory’s energy dependence and strengthen the commitment to renewable energy. Public administration (local/regional articulation with national authorities) and businesses DGEG; CIM Alto Minho; and AREA Alto Minho were identified as the key partners for this process. This is why the project COMENERG is happening, and the trial in Ponte da Barca as local authority is being prepared. Moreover, this effort is framed within the strategic context of the transition towards net-zero cities in 2050.

From that planning, the estimated cost of EUR 250 M is expected to drive the spread of distributed generation for the time scale 2021–2030. The output indicators would be n. of established renewable energy communities; n. of people/businesses that benefited from support; energy savings (expressed in MWh/year); renewable energy production (expressed in MWh/year)—all of which were zero in 2022. However, there were no estimates about the expected results of these indicators in 2030, nor were there eligible candidates initially identified for this opportunity, despite the fact that the EU funding mechanisms were identified. Some techno-economical studies on the national scale must be considered by government authorities of regions such as Alto Minho at the regional scale [20,21]. These studies are important to derive concrete milestones, not only by energy utilities but by local authorities; otherwise, the use of the indicators is questionable. They also guide us to decide which business model every leading actor should adopt.

Partnerships between ESCOs and municipalities was preferentially directed towards the refitting and refurbishment or public lighting and municipal sport facilities in Alto Minho [36]. It is a favorable risk to continue these kinds of partnerships, as long as the business model remains positive for the municipality, the ESCO, and now also to the consuming families as major beneficiaries of the bill savings. Municipalities like Ponte da Barca should comprehend the whole possibilities on this subject of ECs and ECBMs, in defense of themselves and their citizens. If they prioritize their citizens, they must improve their bottom-up policies instead of top-down partnerships with companies that will not reinvest their profits in the region.

Meanwhile, in Spain, energy utilities and ESCOs have moved forward to explore their other ECBM with prosumers like SME’s and condominiums, and it is paying off. Iberdrola, the main electricity business in that country, has brought together 751 solar communities, 10 within the Province of Ourense, the Galician partner of the COMENERG project. Their purpose is to match citizens’ available rooftops with their will to adhere to Iberdrola ECBM. Iberdrola assumes the leading role of the EC, builds the energy facilities, manages the participation of more citizens for sharing available capacity of the facilities and contracts with each member of the solar communities. The local municipality is mostly nonparticipant in Galician CERs. At the same time, there are EU funds available for CER constitution, so the regions and citizens push forward to adopt a more involved ECBM and must take responsibility for it. In the Galician CERs, 94% used governmental subsidies, and 36% used their own capital, in some proportion. In all of Spain, public awareness on new CER regulation already resulted in registered 353 CERs in 2023 (19 in Galicia). The resemblance in technology and monitoring is evident among ECBMs; thus, an unaware customer may think that the business model is only one. In Portugal, the ERSE pilots belong to several ECBMs; therefore, one sees a common quest between ESCOs, major utilities, and energy cooperatives, all proposing their business models to the local authorities/lands where the pilot is held.

To manage these trade-offs, the goal of creating a cross-border office to support the energy transition has been achieved by COMENERG. The contract for its creation was awarded in November 2024, and the office was inaugurated on 30 January 2025. Located in Ourense, it began providing technical services to municipalities, businesses, associations, and individuals, completing the Galician office offer in other provinces of Pontevedra, Lugo and A Coruña—and extending the service to a non-existing public office in the North of Portugal. Currently, communication and awareness campaigns on energy savings and efficiency have been launched. In addition, the office provides advice on available grants and subsidies, including European funds, to finance projects. It also provides information on important regulatory developments. As an extension, several public meetings have been held, such as the one in San Cristovo, to explain the concept of local ECs, the participation and financing mechanisms, and to answer citizens’ questions. These meetings brought together mayors, local representatives, and dozens of residents in the province of Ourense. The Province of Ourense’s goal is to deploy 17 local ECs in 17 municipalities. The most advanced local ECs project is in A Peroxa, whose energy community is expected to be operational before the end of 2025.

As a demonstration, pilot projects are continuing to be developed. Technical designs for solar photovoltaic installations have been officially approved in A Gudiña and Muíños (Ourense). Each Spanish installation will have a capacity of 100 kW and will be located on municipal rooftops. The process for the transfer of rooftop use by the town halls to the local EC is underway, and procedures for connection to the electricity grid have begun.

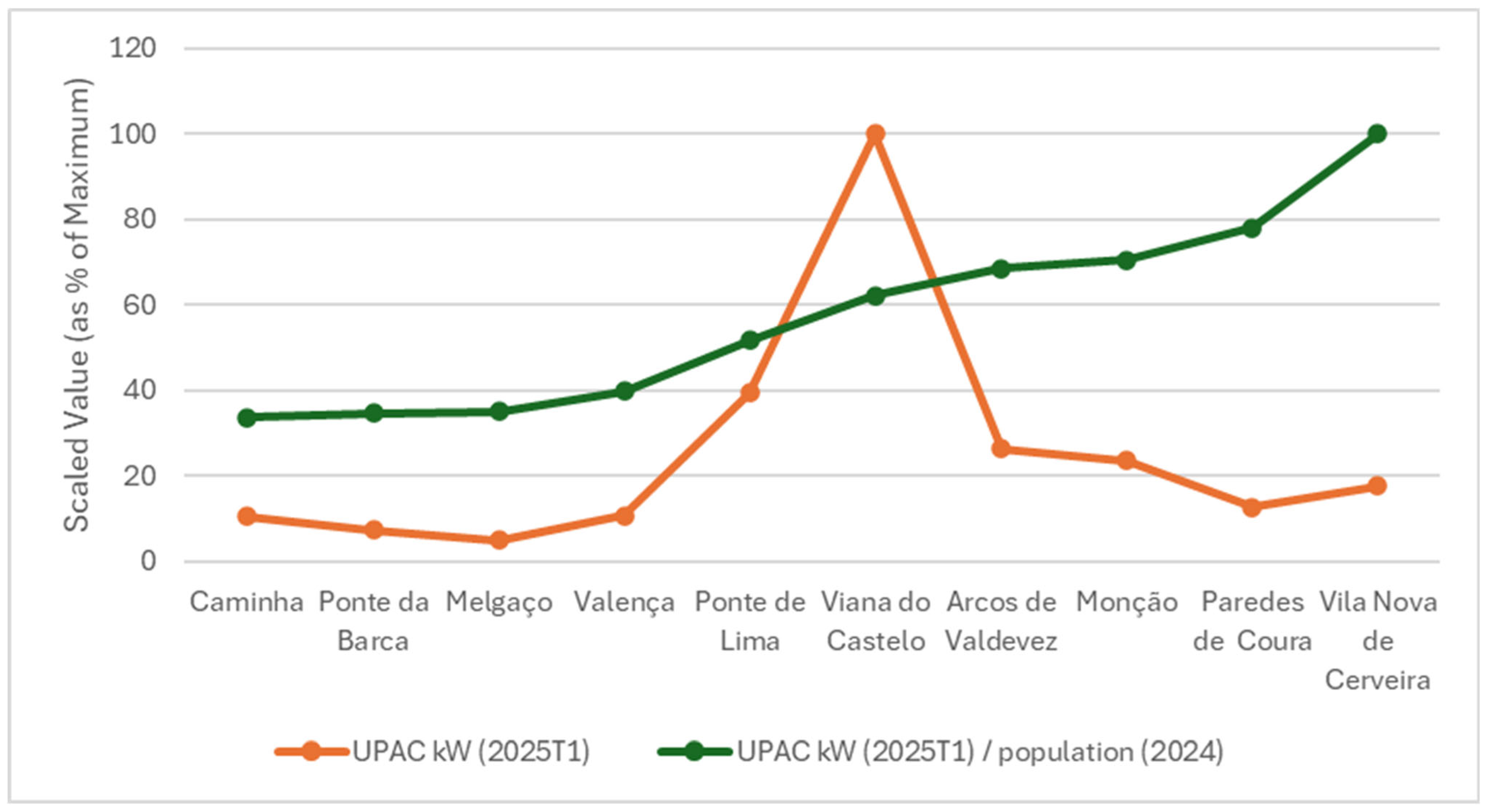

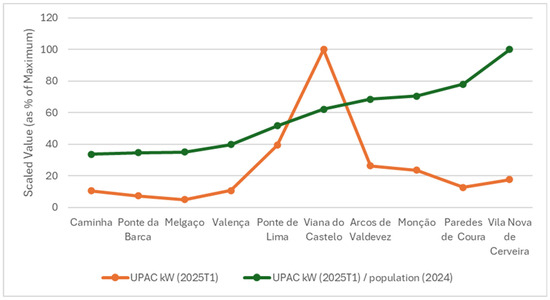

In Ponte da Barca, the location of the pilot project has been determined. Like all other counties in the region, Ponte da Barca suffers a population decrease. Moreover, the total small-scale energy distributed is one of the least productive per person in Alto Minho (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

PV self-consumption development in NUTS3 Alto Minho.

From 218 UPACs in the county, 87% are rooftop systems of an average 2 kW house. The power capacity size of the pilot project in Ponte da Barca, 100 kWp, represents 12.8% of the county capacity, which will have a mediatic impact. The consumption savings obtained by the school center will extend to other families in the Freguesia, especially the ones in energy poverty status. The project pilot will look for consumers and not prosumers families. It is expected that the number of CER members will be in the 20–30 range, which is like the Galician CER (less than 20 in 73% of the 19 CER).

To drive the replication process, one can start right now in Portugal, as Spain is doing. The cross-border office to support the energy transition can call a dissemination campaign for videoconferences with the interested families of Ponte da Barca and is held accountable for early organization of the local EC process up to its conclusion, as is happening for the local EC of Ourense. Namely, the process can involve organizing the community, designing the project and checking its viability, finding funding and subsidies, installing the infrastructure and managing the energy, and monitoring and supporting the project long-term.

The municipal authority of Ponte da Barca needs to find its right balance and preview the financial resources for long-term maintenance of the cross-border office as a valuable extension of the knowledge synthesis acquired during the COMENERG project. This strategy must involve the Norte NUTS 2 and Galica NUTS 3, Ourense and Alto Minho, sharing investment among each one of their municipalities/counties. There are multiple possibilities for the involvement of a municipality that are also related to the type of partnership and business model to adopt (Table 6).

Table 6.

Roles of local municipality in a CER. Source: Ref. [30].

The role of each municipality that is involved in the Euroregion Galicia–North of Portugal must be customized. There is an opportunity that the joint cross-border office for the energy transition represents for the whole of the policies of each municipality and their respective customers.

Ponte da Barca opted to engage into the CER constitution to enter the COMENERG opportunities of development. However, the future EC prosumers and consumers should have the choice from all the possible business models and another ACC commitment level rather than CER. All the business models possibilities should be explored by the support office for energy transition. Many consumers may not be aware of the choice possibilities according to the intensity of involvement and of financial investment. It is not a question of the absolute best but the best trade-offs especially for (1) consumers, (2) municipalities (3) utilities/ESCOs, and the knowledge transferred to the support office by the academia must be clear and not biased towards any of the ECBMs. The lack of the ECBMs is patent on the information that was collected about the ERSE pilot studies, except for the cooperative model, which was clearly explained.

The path for local energy communities with the municipality participation as active member may shift adrift from the subsidized model with proactive leadership from the local municipality as actually in Galicia. Eventually the rollout of the EC will be achieved through several business model archetypes (Table 7).

Table 7.

Citizens and business models participation overview.

4. Conclusions

This study is limited because the technical data about the energy community business model and on the regulatory framework implementation is scarce in Spain and even more in Portugal. We tried to give an overall picture of the most advanced progresses in Portugal and Spain, for the region of Alto Minho and the Province of Ourense.

The implementation of local energy communities in Spain and Portugal is progressing, strongly supported by EU, regional, and local funding. These funding opportunities often act as triggers, encouraging the rapid formation of citizen groups seeking to benefit from both investment savings and return on investment. This top-down incentive has led to a bottom-up mobilization of citizens, even though many decisions were made without the support of local advisory offices.

The constitution of a EC with ACC is relatively easy; however, significant challenges remain. One of the key issues is the ongoing test phase of energy-sharing rules in both Portugal and Spain. There is currently little confidence that optimal decisions will emerge from this phase, but this uncertainty is not a major barrier to the creation of ACC at this point.

Citizens are the main drivers and end-users of autonomous ACC models such as CERs ad CCEs. Where ACCs are fully citizen-owned, governance depends on achieving consensus and equal participation. When other stakeholders are involved—such as utilities or local authorities—the governance process becomes more complex and time-consuming due to differing roles and consumption profiles.

In high-intensity participation models, where all members co-own the equipment, it is crucial to establish legal safeguards. These include prohibiting the withdrawal of physical assets and ensuring long-term commitment. Long-term considerations like the resale of energy shares are often overlooked, yet they are essential for sustainability.

Business models (BMs) vary. In cases of limited funding, partnerships with ESCOs or utilities may be necessary. While this may deviate from the original citizen-led spirit of CERs, such partnerships can still generate significant energy savings. If the ESCO is local, or if bulk energy efficiency services are added (e.g., to fight energy poverty), this model could still align with community goals. Bulk acquisitions could follow sharing coefficients similar to energy-sharing rules and allow municipalities to subsidize energy bills for vulnerable families.

However, in Portugal, the Court of Auditors has blocked municipalities from joining CERs due to public procurement regulations. This raises questions about the constitutionality of such decisions, as CERs are based on voluntary participation.

Another challenge is the long licensing process, driven by the need to ensure grid security. Moreover, there is concern about the sustainability of CERs once EU funding ends. There is a risk that citizen-led CERs will be replaced by corporate solar communities focused solely on cost savings—like those promoted by Iberdrola—where citizens are not the primary actors.

Most energy communities (ECs), and particularly CERs, rely heavily on subsidies and incentives, which are often directed at entities other than citizens. The last national funding call in 2024 included all stakeholders and encouraged the formation of both ACCs and CERs. This led many groups to quickly recruit members to meet funding deadlines.

Although statistics on the number of CERs and ACCs are lacking, ACCs are generally easier to implement and can still reduce energy costs and alleviate energy poverty, especially in cases where long-term citizen engagement is limited.

To ensure informed participation, citizens must be given the freedom to choose their business models and legal structures. Public support offices should be maintained as long-term services to help citizens understand energy community business models (ECBMs) and support the creation of legal CERs. At present, there is a clear lack of accessible information to identify who will actually use the energy produced.

The return on investment (ROI) for CERs like the Telheiras Cooperative is estimated at 5 to 7 years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.d.A. and A.C.; methodology, P.d.A. and A.C.; validation, P.d.A. and A.C.; formal analysis, P.d.A. and A.C.; investigation, P.d.A. and A.C.; resources, P.d.A. and A.C.; data curation, P.d.A. and A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.d.A. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, P.d.A. and A.C.; visualization, P.d.A. and A.C.; supervision, A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Programa de Cooperación Interreg VI A España—Portugal (POCTEP) 2021–2027, de Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)”, grant number 0052_COMENERG_1_E. A.C was supported by proMetheus, Research Unit on Energy, Materials and Environment for Sustainability—UIDP/05975/2020, funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia. This article was developed within the framework of the COMENERG Project–Cross-border Energy Community for the Transition towards Energy Autonomy and Sustainability in the Raia Region, funded by the Interreg Spain–Portugal Programme (Project Code No. 947_COMENERG_1_E).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author P.d.A. used a Chat GPT version 5 free plan, for the purpose of summarizing text and proposing tables. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC | Collective Self-consumption (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| ADENE | Portuguese Energy Agency |

| BM | Business Model |

| CER | Renewable Energy Community (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| CCE | Citizen Energy Community (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| ECBM | Energy Community Business Model |

| EC | Energy Community |

| EGAC | Self-consumption Management Entity (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| ERSE | Portuguese Energy Regulator |

| ESCO | Energy Service Company |

| ORD | Distribution System Operator (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| RES | Renewable Energy Source |

| SEN | National Electric System (Portuguese abbreviation) |

| UPAC | Self-consumption Production Unit (Portuguese abbreviation) |

References

- Koltunov, M.; De Vidovich, L. Energy Communities in Social Sciences: A Bibliometric Analysis and Systematic Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 220, 115871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decreto-Lei No 15/2022; Estabelece a Organização e o Funcionamento do Sistema Elétrico Nacional, Transpondo a Diretiva (UE) 2019/944 e a Diretiva (UE) 2018/2001. Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- Soeiro, S.; Ferreira Dias, M. Community Renewable Energy: Benefits and Drivers. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispim, J. Introdução. In Comunidades de Energia Renovável; Crispim, J., Gomes Mendes, J., Eds.; UMinho Editora: Braga, Portugal, 2023; pp. 9–14. ISBN 978-989-8974-93-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, R.J. Representing Renewable Energy Communities: A Social Psychological Approach to Imagining the Future. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, P.; Ferreira, R.; Ferreira, C.; de Abreu, J.; Afonso, M.; Graça, D.; Ettner, D.; Lima, R.; de Brito, M.; Vieira, I.; et al. O Novo Regime Jurídico Do Setor Elétrico. Comentários Ao Decreto-Lei n.o 15/2022, de 14 de Janeiro; Baptista, C., Krupenski, M., Patrício, R., Eds.; Instituto Miguel Galvão Teles: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- ADENE; DGEG. Autoconsumo e Comunidade de Energia Renovável—Guia Legislativo (Manual Digital); Agência para a Energia: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Decreto-Lei No 99/2024; Altera o Quadro Regulatório Aplicável Às Energias Renováveis. Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2024.

- Diretiva n.o 12/2022; Condições Gerais Dos Contratos de Uso Das Redes Para o Autoconsumo Através RESP. Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2022.

- Regulamento n.º 815/2023; Aprova o Regulamento do Autoconsumo do Setor Elétrico e revoga o Regulamento n.º 373/2021, de 5 de maio. Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023.

- Regulamento n.º 827/2023; Aprova o Regulamento das Relações Comerciais dos Setores Elétrico e do Gás e Revoga o Regulamento n.º 1129/2020, de 30 de Dezembro. Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023.

- ERSE. Projetos-Piloto Aprovados Ao Abrigo Do Regulamento Do Autoconsumo 1. Available online: https://www.erse.pt/media/c4yh2b3g/lista_site_projetos_piloto_pt_.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Resolução Do Conselho de Ministros n.o 53/2020; Aprova o Plano Nacional Energia e Clima 2030 (PNEC 2030). Diário Da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2020.

- Ferreira, E.C.C. Renewable Energy Communities: Concepts, Approaches and the Case Study of Telheiras Neighborhood in Lisbon. Master’s Thesis, University Nova of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, F.; Guyet, R.; Feenstra, M. Do Renewable Energy Communities Deliver Energy Justice? Exploring Insights from 71 European Cases. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 80, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, D.F. Impactos e Barreiras para a Implementação de Comunidades de Energia. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, M.; Di Nucci, M.R.; Schwarz, L.; Alonso, I.; Azevedo, I.; Bastiani, M.; Dyląg, A.; Laes, E.; Hinsch, A.; Klāvs, G.; et al. Implementing European Union Provisions and Enabling Frameworks for Renewable Energy Communities in Nine Countries: Progress, Delays, and Gaps. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharnigg, R.; Sareen, S. Accountability Implications for Intermediaries in Upscaling: Energy Community Rollouts in Portugal. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 197, 122911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, I.F.; Gonçalves, I.; Lopes, M.A.; Antunes, C.H. Business Models for Energy Communities: A Review of Key Issues and Trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 111013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, M.B. Techno-Economic Analysis of Energy Communities and Self-Consumption Schemes in Portugal and Italy. Master’s Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lage, M.; Castro, R.; Manzolini, G.; Casalicchio, V.; Sousa, T. Techno-economic analysis of self-consumption schemes and energy communities in Italy and Portugal. Sol. Energy 2024, 270, 112407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.M. The Business Model of Solar Energy Communities: A Case Study from Portugal. Master’s Thesis, Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Calhau, F.; Pintassilgo, P.; Guerreiro, J. Comunidades Energéticas Sustentáveis: Estudo de Implementação de Uma Comunidade Eólica No Algarve; Universidade do Algarve Editora: Faro, Portugal, 2020; ISBN 978-989-8859-91-1. [Google Scholar]

- Godinho, A. Desenvolvimento de Plataforma Para Gestão de Comunidades de Energia Renovável. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Nova of Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, I.F.G.D. Modeling Energy Communities: A Multiagent Framework. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro, D.; Chediek, J.; Cardoso, L.; Faria, M.; Campos, P.F. Energia para os Cidadãos Guia Para a Criação de Comunidades de Energia Em Portugal; Instituto Jurídico da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sequeira, M.M.; Ferreira, E.; Pereira, L.K.; Cachinho, L.; Martins, H.; Gouveia, J.P.; Antunes, A.R.; Bernardes, B.; Boucinha, A. Guia Prático: Desenvolvimento de Comunidades de Energia Por Cidadãos, Associações e Autarquias—O Exemplo Da Comunidade de Energia Renovável de Telheiras/Lumiar; Universidade Nova of Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- ADENE. Promotores Comunidades de Energia—Poupa Energia. Available online: https://poupaenergia.pt/promotores-comunidades-de-energia (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- DGEG. Estatísticas Rápidas das Renováveis; nº 245; Direção Geral de Energia e Geologia: Lisboa, Portugal, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fundación Ecología y Desarrollo. Observatorio Nacional de Comunidades Energéticas. Informe de Indicadores 2023; Fundación Ecología y Desarrollo: Zaragoza, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ponte da Barca. Plano Municipal de Ação Climática de Ponte da Barca—Versão Preliminar; GeoAtributo: Braga, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- CM Ponte da Barca. Plano de Ação para as Energias Sustentáveis—Ponte da Barca; CM Ponte da Barca: Ponte da Barca, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Diputación de Ourense; CIM do Alto Minho; Instituto Politécnico de Viana do Castelo; AREA Alto Minho; Instituto Enerxético de Galicia (INEGA); Universidade de Vigo COMENERG. Cross-Border Energy Community for the Transition to Energy Autonomy and Sustainability of the Raia Localities—Application Document. In INTERREG VI A España Portugal (POCTEP) 2021–2027; European Commission: Badajoz, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- POCITYF. Objectivos POCITYF—Évora; Labelec Estudos Desenvolvimento e Actividades Laboratoriais SA: Lisboa, Portugal; Alkmaar, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. Grid Integration of Electric Vehicles within Electricity and Carbon Markets: A Comprehensive Overview. eTransportation 2025, 25, 100435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIM Alto Minho; AREA Alto Minho. Alavancar Investimentos de Eficiência Energética. Contratos de Gestão de Eficiência Energética. A Experiência Do Alto Minho; CIM Alto Minho: Ponte de Lima, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).