Abstract

Nowadays, with the continuous development of corporate ESG ratings, greenwashing has occurred continuously. In order to clarify the influence of the environmental protection tax (EPT) on corporate ESG greenwashing, this paper employs the implementation of the Environmental Protection Tax Law (EPTL) as a quasi-natural experiment, based on the sample data of Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share listed companies during 2015–2022. Using a Difference-in-Differences model to analyze the effect and mechanism of the EPT on corporate ESG greenwashing, we obtain the following findings: (1) The EPT can curb corporate ESG greenwashing, and this effect is more obvious in non-state-owned enterprises, non-labor-intensive enterprises, low-competitive industries, and enterprises located in the east-central region of China. (2) From a mechanistic perspective, reducing information asymmetry and promoting green transformation are two important paths. (3) Higher ESG ratings increase the inhibition of the EPT towards corporate ESG greenwashing.

1. Introduction

In recent years, global economic development has begun to face serious challenges alongside global warming, prompting countries to look for new drivers of economic growth. For China, since the Reform and Opening-Up Policy, China has witnessed substantial economic development, garnering international attention. The nation has successfully transitioned from a planned economy to a market-driven model. This has led to its emergence as the world’s second largest economy. However, this period of growth has coincided with significant environmental challenges, including atmospheric pollution, desertification, and soil erosion. Further, from “ecoenvironmental progress along with economic, political, cultural and social progress in the Five-Sphere Integrated Plan as the goals for building Chinese socialism” put forward by the 18th CPC National Congress to “actively and prudently work toward peaking carbon dioxide emissions and achieving carbon neutrality” put forward by the 20th CPC National Congress, the issue of environmental protection has been taken seriously. In order to promote ecological construction, China passed the Environmental Protection Tax Law (EPTL) on 25 December 2016, which came into effect on 1 January 2018. The abolition of sewage fees and the establishment of an environmental protection tax (EPT) system indicated a greater commitment to environmental protection in China. This is because the implementation of the EPT has placed significant pressure on enterprises. This includes the pressure to transform and comply with regulations. This has played a crucial role in restraining them.

Meanwhile, ESG is also evolving. From “the concept of innovative, coordinated, green, open and shared development” put forward by the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee to the report of the 20th CPC National Congress, which further pointed out that “the development of green finance is an inevitable requirement for promoting green development”, green finance has emerged as a pivotal catalyst in China’s pursuit of sustainable development and the preservation of the ecological environment. In order to achieve economic globalization and high-quality development of our economy, China has further integrated ESG funds into the green financial system [1], where “E” stands for environmental, “S” stands for social, and “G” stands for governance. However, this trend has also given rise to greenwashing. Corporate ESG greenwashing refers to the fact that companies make superficial improvements in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards without actually taking substantive improvement measures [2]. Therefore, this study intends to use the implementation of the EPTL as a quasi-natural experiment, using the Difference-in-Differences model to analyze the effect and mechanisms of the EPT towards corporate ESG greenwashing.

The marginal contributions are as follows. First, this paper provides a novel micro-level analysis by examining the EPT’s efficacy in curbing corporate greenwashing, a critical yet under-explored aspect of ESG compliance. Second, this paper moves beyond establishing mere correlation by testing dual mechanisms: an external channel that reduces information asymmetry for investors, government, and society; and an internal channel that incentivizes green transformation within the firm’s production behaviors. This integration of internal and external perspectives offers a more comprehensive understanding of the EPT’s micro effects. Third, studying the micro effect of EPT implementation from the perspective of corporate ESG greenwashing will be helpful for the improvement of China’s tax system as well as the realization of the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals.

There are six remaining sections of the paper. In Section 2, we conduct a literature review. In Section 3, we carry out policy ground and formulate the research hypothesis. In Section 4, we design the research. In Section 5, we represent the results. In Section 6, we carry out further study. In Section 7, we state the conclusion and make corresponding policy recommendations.

2. Literature Review (Theoretical Review)

Research on the EPT originated in Europe. On the basis of the theory of external economy, Pigou first proposed the concept of Pigou tax in 1920, which means that enterprises or individuals should bear the corresponding tax burden based on the amount of pollutants emitted. Since then, the EPT has continued to develop and gradually focused on the comprehensive management and utilization of resources.

At the macro level, for a long time, most experts and scholars have believed that taxation can be one of the important means to protect the environment [3]. Moreover, they have proposed the double-dividend hypothesis based on this. The double-dividend hypothesis is mainly reflected at the environmental and economic levels. From the environmental perspective, the collection of the EPT can directly minimize the emission of pollutants [4], so as to maintain the ecological balance. Through the introduction of the EPT, the government and the community can better recognize the value of environmental resources and, thus, be more positive in protecting and managing the environment. From the economic perspective, the EPT can motivate businesses to produce and live in a more environmentally sustainable manner, thereby driving economic structural transformation and upgrading [5]. Meanwhile, the revenue from the EPT can also be used to support environmental protection projects and compensate groups affected by the environment. In addition, some scholars believe that the EPT has different impacts in the short and long term, as well as in developed and developing countries [6]. They consider that the EPT may hinder economic growth when developing countries are just beginning to reap tax benefits. Therefore, some scholars further suggest using the EPT as a fiscal incentive measure to address issues such as unemployment faced by some developing countries [7].

At the meso level, the impact from the EPT varies among enterprises in different industries. In heavy-polluting industries, enterprises that disclose their high pollution status or provide environmental information in their reports may face higher regulatory costs [8]. In manufacturing industries, the EPT aims to motivate businesses to promote green innovation, thereby improving their carbon efficiency [9].

At the micro level, after the implementation of the policy, scholars have carried out progressive research on it. First of all, as regards the impact of the EPT towards corporate green innovation, scholars have yet to reach a consensus on the relationship between the two. Most scholars believe that the EPT promotes green innovation. In terms of before and after implementation, the implementation of the EPTL in 2018 has significantly reduced pollution emissions at the provincial level [10]. In terms of the impact mechanism, Lu and Zhou [11] verify this green innovation effect by utilizing DID, DDD, and PSM-DID. Moreover, they also suggest that the EPT can enhance corporate green innovation by changing the management mode. Some articles have also shown that the EPT has no effect or even inhibits corporate green innovation. The collection of the EPT increases the corporate operating costs. Moreover, these additional costs may crowd out the resources that enterprises would otherwise use for green innovation, leading to insufficient investment in innovation by enterprises [12]. Deng et al. [13] find that this motivation is insignificant for non-state-owned enterprises and stagnant firms, and that the EPT discourages green innovation by firms in mature and less-developed areas. Second, the impact of the EPT towards the total factor productivity (TFP) of companies was investigated. In terms of the impact mechanism, Sun and Zhang [14] use the DDD model to conclude that the EPT can noticeably increase the TFP by promoting technological innovation and effective resource allocation. From the perspective of the time dimension, this facilitation effect increases over time [15].

ESG principles were introduced to China relatively late, and their development in China can be divided into three stages: first, when China joined the WTO, companies were influenced by the world economy and gradually accepted the obligation of information disclosure [16]; second, the Guidance on Establishing a Green Financial System, released in 2016, focuses on sustainable development and social responsibility, increasing the use of ESG ratings in China’s markets [17]; and third, China’s clearly stated mission of achieving carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals has made the transition to a green and low-carbon economy an unavoidable path to achieving the target [18].

The original intent of promoting ESG principles was to guide companies toward pursuing sustainable development. However, this has also given rise to some companies engaging in ESG greenwashing to gain reputational advantage. The reason for this is that, first, ESG standards and disclosure requirements are not consistent globally. There is a lack of uniform standards and regulatory frameworks [19], which gives companies the opportunity to choose the highest rated organization to report on, thus covering up actual malpractices. Second, due to the incomplete development of regulatory and enforcement frameworks concerning ESG principles, there exists a gray area that complicates the effective prevention or punishment of greenwashing practices [20]. Third, ESG disclosure of listed companies in China is still in the stage of “semi-mandatory + voluntary” [21]. For listed companies that are not subject to mandatory disclosure requirements, they may choose not to disclose or only partially disclose ESG information for reasons of cost, time, and resources. This can result in incomplete and inaccurate disclosure, which may have a subsequent impact on the decisions made by investors.

Scholars mainly study the impact of the EPT towards corporate greenwashing, with few studies on its impact on corporate ESG greenwashing. Although the current academic circle has recognized that the proposal of the EPT can affect the greenwashing of enterprises, there is still no consensus. Meanwhile, with today’s increasing ESG development, corporate ESG performance offers a broader and more comprehensive view of greenwashing. On the one hand, corporate ESG performances help enterprises adjust their internal management system in a timely manner based on the report. In addition, they also provide important support for potential investors to effectively assess the risks of the corporation [22]. On the other hand, corporate ESG performances make enterprises aware of the importance of environmental protection. When they are motivated by short-term profitability or out of their own capacity, they will choose to falsely advertise, leading to the emergence of corporate ESG greenwashing [23].

3. Policy Background and Research Hypothesis

3.1. Policy Background

To address this problem, the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, issued in September 1979, legally established China’s sewage fee system. In February 1982, the State Council issued “The Interim Measures for the Collection of Sewage Fees.” Then, in July 1988, it issued another document: “The Interim Measures for the Reimbursable Use of Special Funds for the Control of Pollution Sources.” These two measures helped establish and improve China’s sewage fee system. However, the sewage fee system was not fully implemented. This was mainly due to several factors, including the lack of formal sewage declarations and adequate regulatory mechanisms. Additionally, China passed the EPTL on 25 December 2016. It came into effect on 1 January 2018. It is used for balancing environmental protection and sustainable economic development as well as solving various problems with the sewage fee system. So far, the reform of environmental fee-to-tax has been implemented.

3.2. EPT and ESG Greenwashing

The EPT is levied according to the quantity and type of pollutants discharged and is more refined and differentiated than the sewerage fee [24]. Companies that emit more pollutants need to pay higher taxes, which directly increases their operating costs. This has a further incentive effect on optimizing resource allocation, promoting the improvement of resource utilization efficiency, helping companies adopt more efficient production tools and more accurate monitoring tools, further promoting the development of heavy-polluting companies towards a more environmentally friendly direction, and reducing pollutant emissions. This tax mechanism provides incentives for companies to pay more attention to reducing greenwashing in their practical actions.

The EPT is significantly more heavily audited than the sewerage fee [25]. At this stage, when a corporation pays the EPT, the amount of pollution emitted during the production process and its performance in environmental protection are open and transparent. This not only enhances supervision of corporate environmental behavior by the tax authority but also discourages ESG report fraud and greenwashing. At the same time, the collection of the EPT is closely integrated with the environmental regulatory mechanism, so that government departments can better monitor the environmental performance of companies through tax data, detect and correct greenwashing at source in time, and enhance the effectiveness of environmental governance.

In summary, implementing the EPT can reduce the level of ESG greenwashing among enterprises and mitigate environmental risks by encouraging enterprises to allocate more resources towards environmental friendliness. This can be achieved by increasing auditing intensity and improving environmental regulatory mechanisms. These measures will promote enterprises’ movement towards sustainable development. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

The EPT contributes to the reduction in corporate ESG greenwashing.

3.3. EPT, Information Asymmetry and ESG Greenwashing

Prior to the implementation of the EPTL, the sewerage fee was a way for the government to manage and regulate businesses environmentally, usually charging a certain percentage of the company’s sales or profits as a fee. Compared with the EPT, some companies may take advantage of regulatory loopholes and use false reporting and concealment to evade the payment of sewerage fees. This is because the sewerage fees of companies are calculated based on their declared sales or profit indicators to relevant departments, and the phenomenon of information asymmetry is more prominent. But the EPT can strictly audit and compare the data declared by companies, so as to improve the authenticity and accuracy of the data and further reduce the degree of information asymmetry. Compared to sewage fee, the EPT is more direct and explicit, imposing economic costs on corporate emissions behavior [26]. This type of tax is more incentive-based. Companies that engage in greenwashing face strict penalties, which can lead to reductions in pollutant emissions and resource consumption. Further, these companies will turn to innovative activities, increase their investment and promotion of innovation, and accelerate the digital transformation of their companies [19]. This, in turn, improves their environmental performance and demonstrates their willingness to go green in the marketplace. As a result, after the implementation of the EPTL, companies that used to have a fluke mentality will change their attitudes. They will start to produce from the perspective of green development under the incentives of the tax rebate and subsidy mechanism, which in turn led to a re-decision of production. Compared with the period of sewage fees, the degree of information asymmetry between internal and external companies has been reduced. This helps effectively curb corporate greenwashing [27]. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2.

The EPT can curb corporate ESG greenwashing by alleviating information asymmetry.

3.4. EPT, Green Transformation and ESG Greenwashing

The EPTL differs from the intervention of local governments in the sewage fee. It forcibly incorporates the EPT into the tax collection and management system. This increases the production costs of companies, ensuring the effective implementation of the EPT system, thereby putting greater pressure on production costs for companies. The internalization of this environmental cost has prompted firms to take measures to reduce pollutant emissions as well as resource consumption [28]. The green transformation of firms is a key part of reducing production costs and improving productivity. According to the Porter’s Hypothesis, the increasing intensity of environmental protection prompts companies to introduce green technology and independent innovation. This, in turn, drives their green transformation. Meanwhile, implementing the EPT strengthens environmental regulations for enterprises, which need to undergo green transformations and adopt more environmentally friendly measures. This effectively reduces EPT payments and helps enterprises avoid reputational loss [29]. Green transformation needs to rely on advanced technology and innovation capabilities, which requires companies to continuously explore and apply advanced environmental monitoring equipment, intelligent control systems, and other innovative technologies [30,31]. Therefore, the EPT not only enables companies to emit fewer pollutants and effectively improve the quality of the external environment, but also effectively improves productivity. All of this will help reduce the greenwashing of companies, promoting the development of companies and the economy towards a more environmentally friendly and sustainable direction. Meanwhile, it will also help enhance the environmental awareness and ecological civilization level of the whole society. Thus, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3.

The EPT can curb corporate ESG greenwashing by promoting corporate green transformation.

4. Research Design

4.1. Data and Sample

In this paper, the listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen A-shares from 2015 to 2022 are taken as the research sample. In accordance with the Environmental Protection Law, which was formally implemented in 2015, the initial period of the sample was set to 2015. This is performed to avoid the impact of significant changes in China’s environmental protection policies before and after the implementation of this policy. This paper defines heavy-polluting companies based on two official documents. The first is the 2012 version of the Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies, revised by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). The second is the Management Directory of Industry Classification for Environmental Verification of Listed Companies, issued by the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP). The classification follows their secondary industry categories. This specifically includes companies belonging to the B06, B07, B08, B09, C15, C17, C18, C19, C22, C25, C26, C27, C28, C29, C31, C32, D44, and D45 industries in the treatment group. The others are included in the control group. Other than that, the initial data are obtained from the CSMAR and Wind Databases. In order to effectively estimate the parameters, the raw data are subjected to the following data processing: (1) financial listed companies such as banks and securities are excluded; (2) samples with too many missing financial indicators are excluded; (3) samples with ST, ST*, and PT during the sample period are excluded; and (4) all continuous variables in this paper are subjected to an upper and lower 1% shrinkage to eliminate the anomalous effects of extreme values.

4.2. Model and Variables

Because the Difference-in-Differences model can effectively estimate the treatment effects of policies, it is widely used in the evaluation of policies. After conducting theoretical analysis on the relationship between the EPT and corporate ESG greenwashing, this article concludes that a DID model should be chosen. Using the implementation of the EPTL as a quasi-natural experiment, we consider whether there is a significant change in corporate ESG greenwashing before and after the implementation when there is no significant difference in the impact of other factors on the treatment and control groups. The specific model is as follows:

where represents the ESG greenwashing index of corporation in year ; is the policy effect of the implementation of the EPTL; represents all control variables used in this paper; represents industry fixed effects; represents time fixed effects; represents the random error term; is the constant term; and are the estimated coefficients.

4.2.1. ESG Greenwashing Index

The explained variable is the corporate ESG greenwashing index (GW). In this paper, we refer to Zhang [32] and construct the following formula to calculate the ESG greenwashing index of a corporation relative to other companies in the same industry.

where represents the disclosure score of corporation ’s ESG rating in year ; and represent the average environmental disclosure score and environmental performance score; and, and represent the standard deviations of the environmental disclosure score and environmental performance score, respectively. In short, the contents of the first and second parentheses denote the standardized treatment of companies in the distribution of environmental disclosure scores and environmental performance scores relative to other companies in the same industry, respectively. Bloomberg is utilized for its unparalleled global ESG data transparency and disclosure verification. It provides extensive, standardized data from thousands of companies, ensuring that claims are credible and aligned with international standards like the EU Taxonomy. This is used to represent environmental disclosure scores, meaning that the data for the variables in the first bracket are all from Bloomberg. Conversely, Huazheng is a leader in providing performance benchmarks within Chinese markets. Its specialized green indices track the real-world financial and environmental performance of companies, validating whether their operations deliver tangible ecological benefits. The Huazheng Rating Index is used to represent environmental performance scores, meaning that the data for the variable in the second bracket are all from Huazheng. To summarize, represents the score of ESG greenwashing of corporation in year . The magnitude of the positive value is directly proportional to the severity of the corporate ESG greenwashing behavior.

4.2.2. Dummy Variables for EPT

The core explanatory variable is , which is expressed as the cross-multiplication term between the treatment group dummy variable and the time dummy variable. , where stands for treatment group dummy variables, which take the value of 1 if the enterprise is a heavy-polluting company and 0 otherwise; and stands for the time variable, which takes the value of 1 if the year is 2018 or later and 0 otherwise.

4.2.3. Control Variables

Moreover, in this paper, firm size (Size), firm age (Age), debt capacity (Lev), equity concentration (Top10), cashflow ratio (Cashflow), growth capacity (Tobin), net profitability of total assets (Roa), and growth rate of total assets (Assetgrowth) are selected as control variables. Based on previous research, the larger the firm size, the higher the return on industrial investment, and the larger the growth rate of total assets, the more prone it is to greenwashing. Moreover, the older the firm, the more profitable it is, and the more concentrated its equity, the less prone it is to greenwashing.

Specific definitions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 demonstrates the descriptive statistics of the variables mentioned above explicitly. The total sample size selected for this paper is 5832, among which there are 2155 heavy-polluting companies and 3677 non-heavy-polluting companies. The standard deviation of GW is 1.1897, indicating that there is a large gap in ESG greenwashing among A-share listed companies in the sample. Among the control variables, the standard deviation of Size is 1.1727, indicating the presence of firms of different sizes in the sample. The standard deviation of Age is 7.2349, and the mean is 14.4294, which indicates that there is a large age gap between the firms. Lev is the gearing ratio, which has a mean of 0.4675, a minimum of 0.0723, and a maximum of 0.8605. Those indicate that the firms in the sample have a low level of financial risk, and all of them are in the normal range. In addition, all other control variables are within the normal range and remain generally consistent with the statistical findings of the existing literature.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

5.2. Parallel Trend Test

The Difference-in-Differences model is conditional on the parallel trend assumption, which implies that the ESG greenwashing of heavy-polluting companies and other companies should be consistent before the policy is implemented. This paper utilizes the event study method proposed by Jacobson et al. [33] to develop the following model:

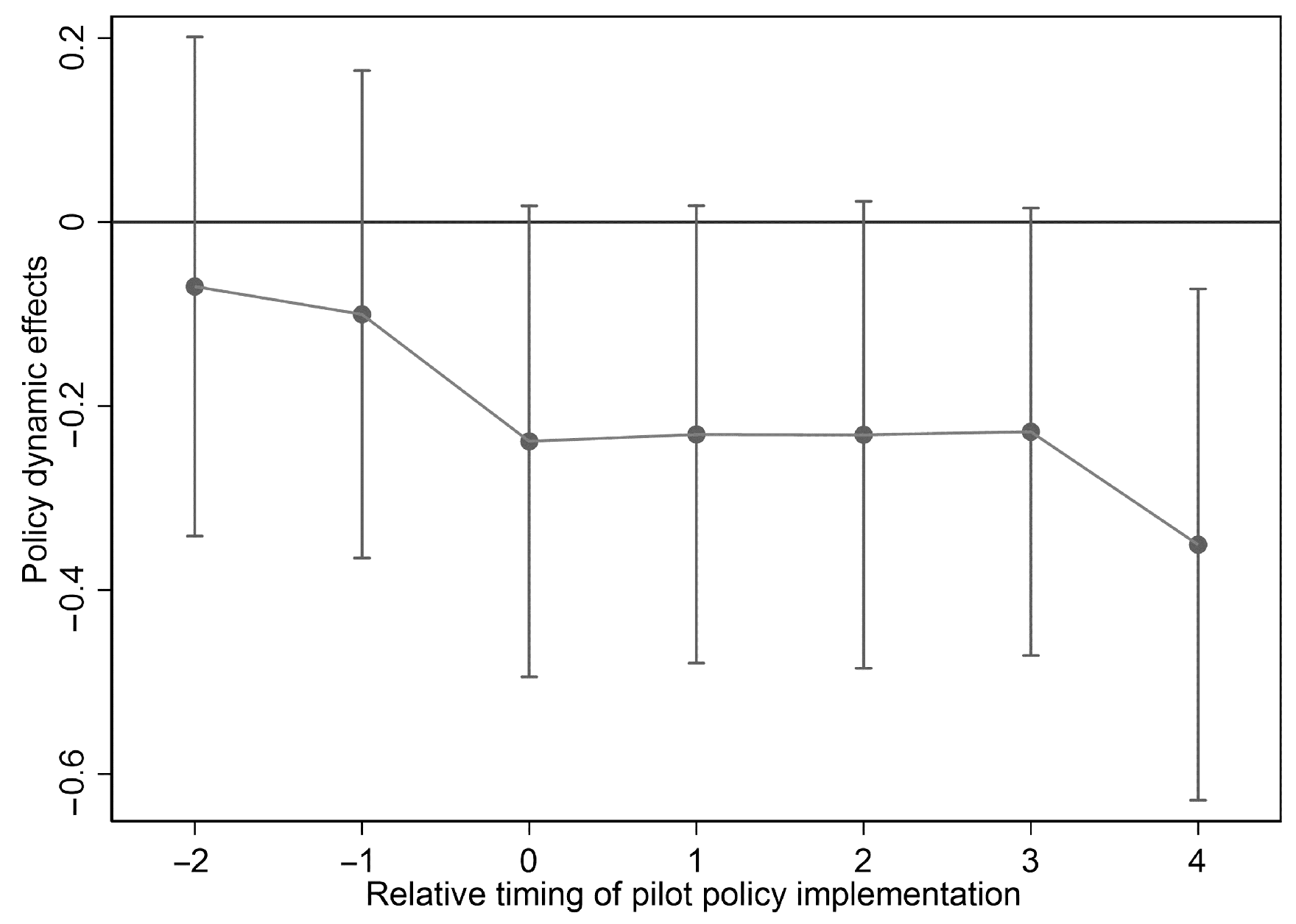

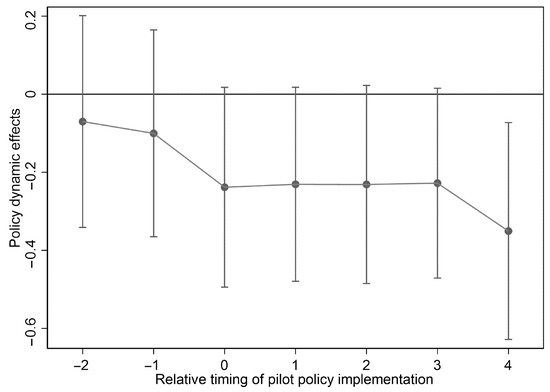

where indicates that if the company belongs to the heavy-polluting industry, and at the same time the EPTL is implemented in year t with year 2018 as the benchmark, it takes the value of 1, and 0 otherwise; is the constant term; and is the estimated coefficient; is the focus of this model, which reflects the difference between the heavy-polluting companies and the non-heavy-polluting companies in the ESG greenwashing index in the year t of the implementation of the EPTL. The result of the parallel trend test is shown in Figure 1. The figure shows that the regression coefficients of the policy effects are not significant before the event, indicating that there is no significant difference in the development trend of heavy-polluting companies and other companies before the implementation of the policy. Therefore, the model passes the parallel trend test. After the implementation of the policy, the significance of the estimated coefficient has changed. In the fourth year after the implementation of the policy, the coefficient is significant at the 5% level, indicating that the EPT has a certain lagging effect on the inhibition of corporate ESG greenwashing. This may be because companies need time to assess their tax burden, adjust their strategies, and implement substantive environmental technology upgrades. This transmission mechanism from cost impacts to behavioral changes naturally requires a certain period of time.

Figure 1.

Parallel trend test.

5.3. Main Results

Table 3 reports the benchmark regression results of model (1), namely the degree of impact of the EPT on corporate ESG greenwashing. Column (1) presents the estimation results when industry and year fixed effects are added without control variables. Columns (2) and (3) present the results of progressive regressions when the relevant control variables are added sequentially. The results suggest that the estimated coefficients of the policy effects of the implementation of the EPTL are significant and decreasing, which indicates that the use of a fixed effects model is more effective in eliminating the endogeneity problem caused by industry and time factors. Column (3) presents the estimation results with all control variables, industry fixed effects, and year fixed effects added. The estimated coefficient of DID decreases by 24.14% compared to the results with no control variables, but remains significantly negative at the 1% level, implying that the EPT decreased ESG greenwashing by 18.87%. These prove that H1 is valid. In addition, the estimated coefficients of Size, Tobin, and Assetgrowth are all greater than zero and significant at the 1% level, indicating that the larger the corporate size, the higher the return on industrial investment, and the larger the total asset size, the more corporate ESG greenwashing there is. Furthermore, the estimated coefficients of Age, Lev, and Top10 are significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the older the firm, the more profitable it is, and the more concentrated its equity, the more corporate ESG greenwashing there is.

Table 3.

Main results.

5.4. Robustness Tests

5.4.1. Placebo Test

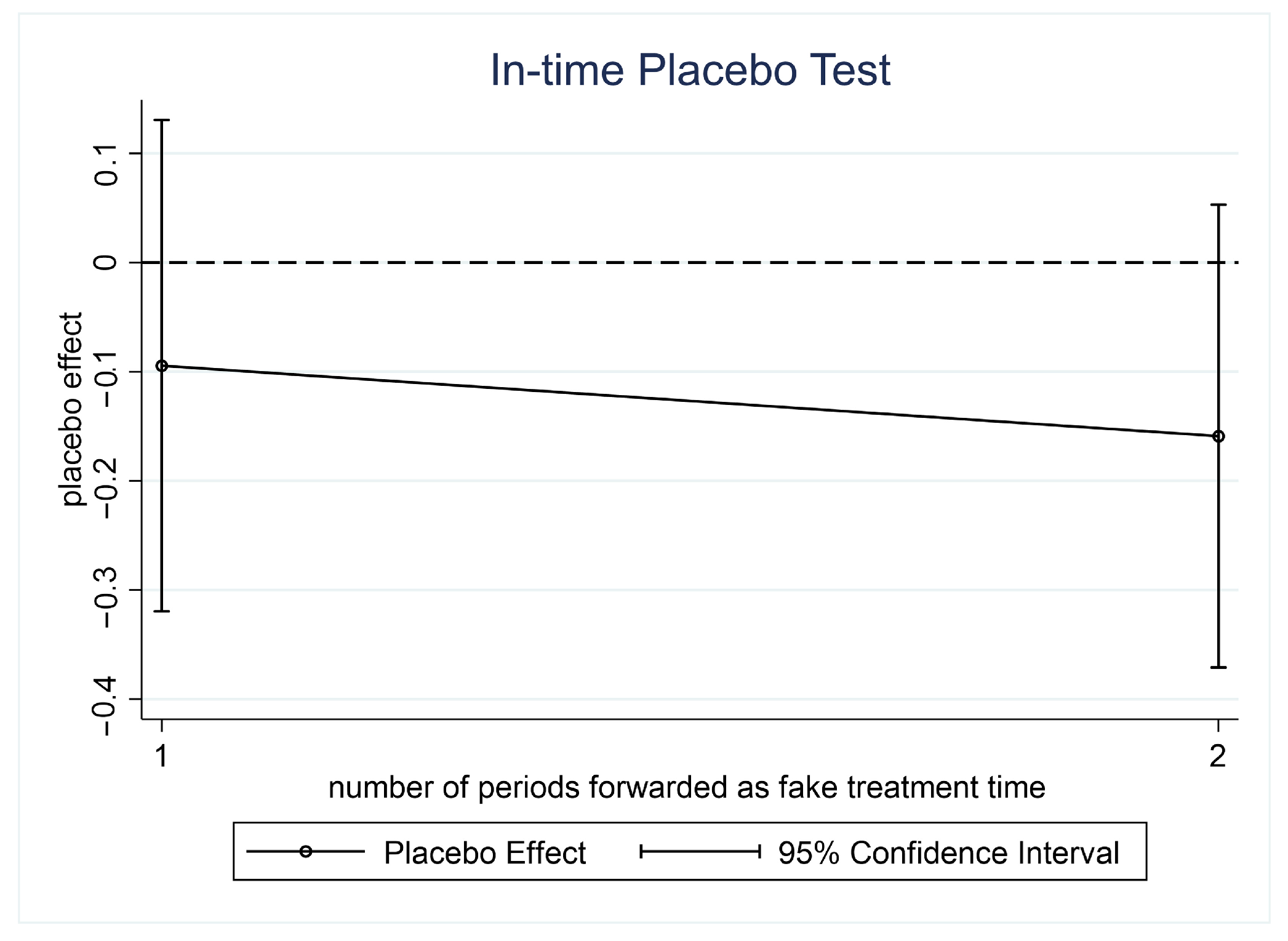

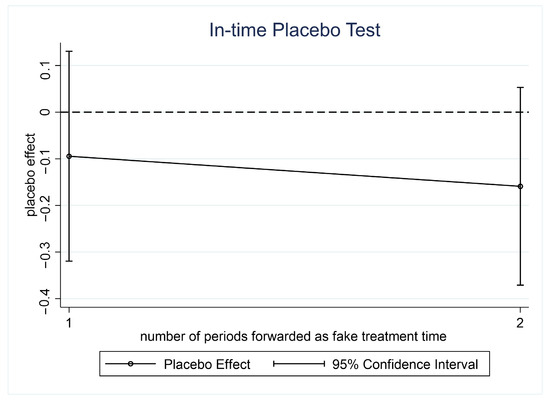

To avoid the effects of time on the results of the benchmark regression on reducing corporate ESG greenwashing behavior, we conduct a in-time placebo test. We create two virtual policy times, and , which denote advancing the implementation of the EPTL by one and two years, respectively. The results are shown in Figure 2. The result shows that none of the estimated coefficients of and are significant at the 10% level, indicating that there is no significant difference in the time trend between heavy-polluting companies and non-heavy-polluting companies. In summary, the in-time placebo test passes, confirming the robustness of H1.

Figure 2.

In-time placebo test.

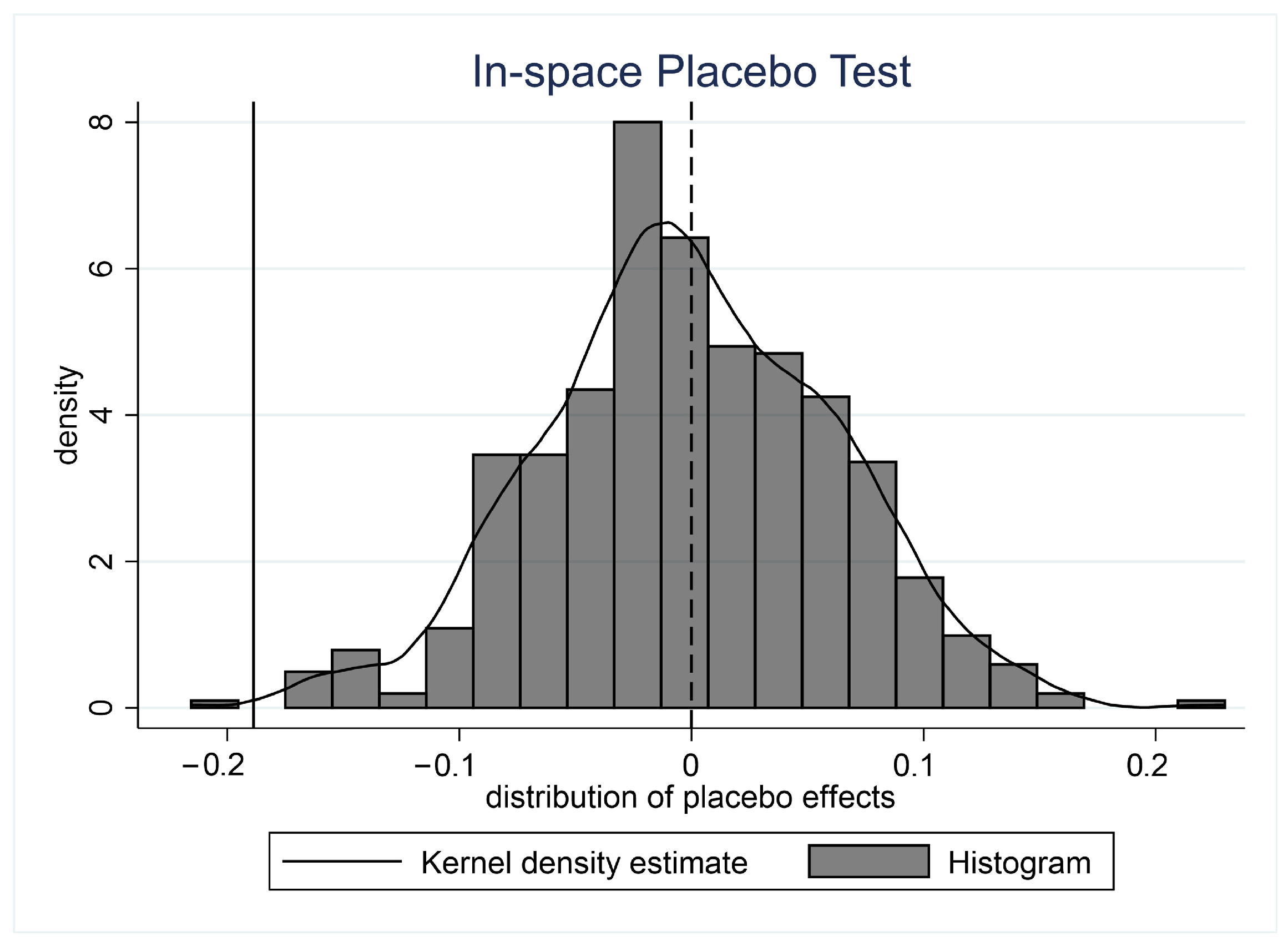

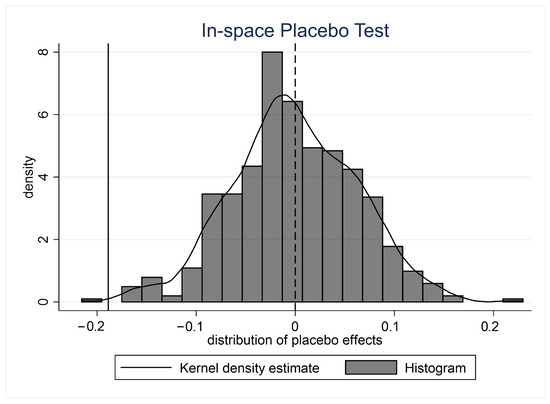

In order to avoid other unobservable omitted variables affecting the results of the benchmark regression, a in-space placebo test was also conducted. Its principle is to randomly determine the group affiliation of individuals within the sample while maintaining the same policy implementation time and sample structure. Then, we estimate model (1) again to obtain the estimated coefficient on ESG greenwashing under the implementation of the in-space placebo. After repeating the above steps five hundred times, five hundred estimated coefficients and p-values can be obtained. The result is shown in Figure 3. The result shows that the standardized regression coefficients all follow an asymptotic normal distribution near zero and are not significant. At the same time, the estimated coefficient value of −0.1887 obtained in the benchmark regression is located in the left long tail of this distribution, which belongs to a low probability event. This indicates that the omitted variables do not affect the benchmark regression results, confirming the robustness of H1.

Figure 3.

In-space placebo test.

5.4.2. PSM-DID

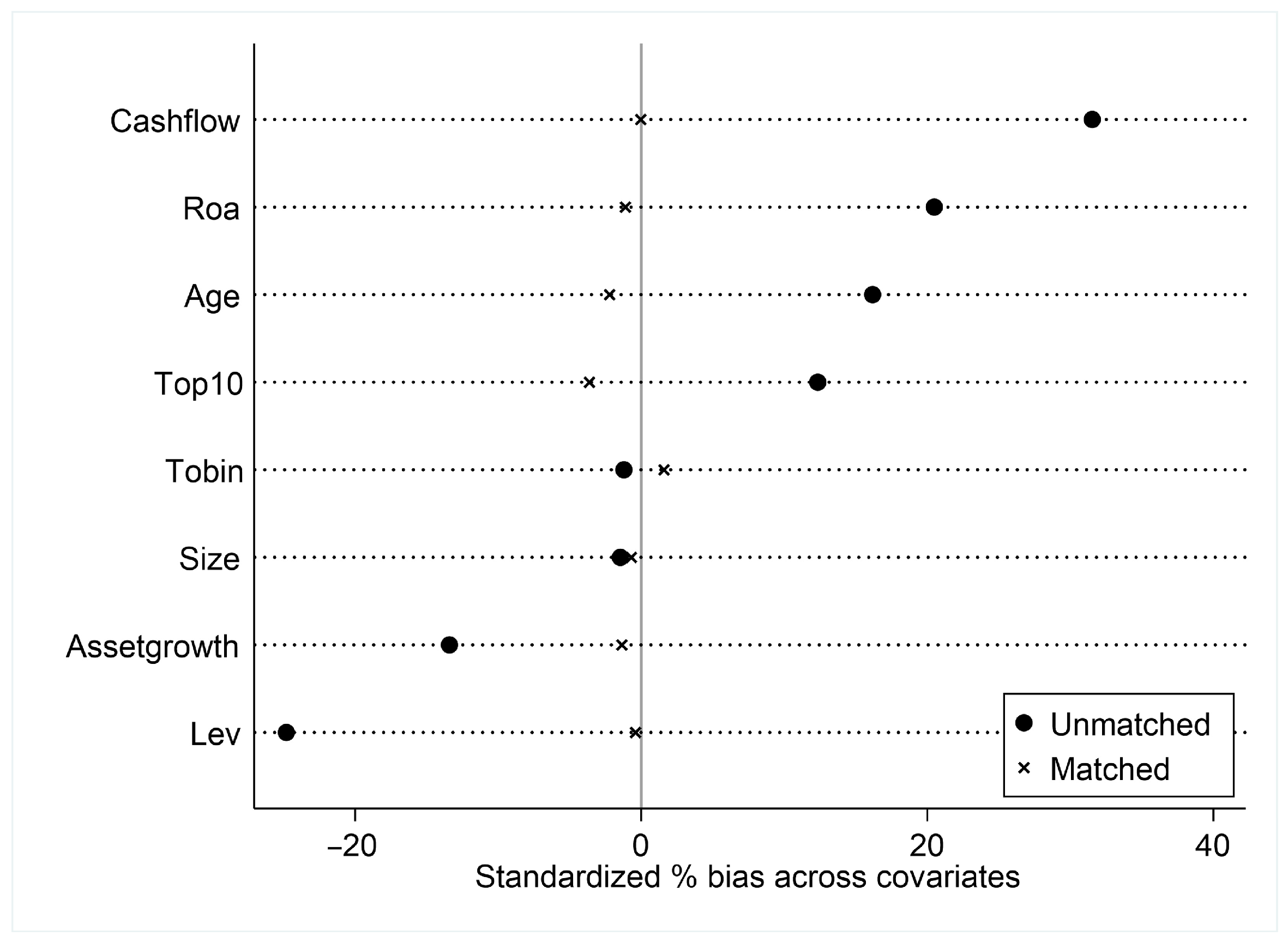

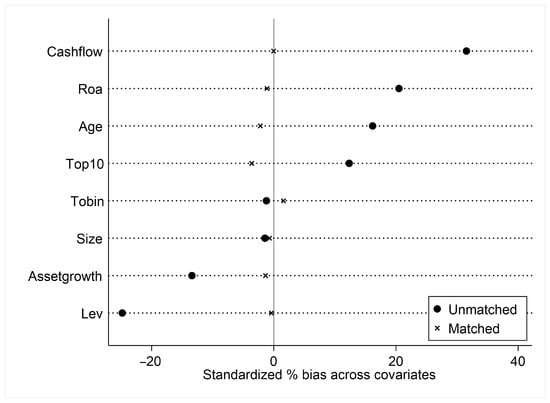

To avoid the problem of endogeneity, we further opt for the propensity score-matching method to match the control and the treatment groups. This is because, although it is difficult for corporate ESG greenwashing to affect the implementation of the EPT, the problem of sample selection bias will occur. In order to avoid such problems affecting the estimation results of the regression, it is necessary to conduct a robustness test with the PSM-DID model. In this paper, a 1:1 matching method without put-back is chosen. The results of the PSM validity test are shown in Table 4. According to the results of the t-test, it can be seen that there is no significant difference between the control and treatment group after matching, which verifies the validity of the matching and satisfies the premise of DID. The DID model can be used for regression. The results of the balance test are also shown in Figure 4. They indicate that after propensity score matching, the standard differences between the control and treatment group samples are significantly reduced, falling within the 10% range. Further, Table 5 is consistent with the findings of Figure 4, which allows for regression using the DID model. Column (1) of Table 5 represents the result of the benchmark regression using this method, and it can be seen that the magnitude of the estimated coefficient is similar to that of the coefficient when only the DID model is used. It is significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the results obtained from the benchmark regression are not significantly related to endogeneity, and that H1 still holds.

Table 4.

PSM validity test results.

Figure 4.

Balance test results of PSM.

Table 5.

Robustness tests.

5.4.3. Shorter Sample Period

In order to avoid the impact of other policies on corporate ESG greenwashing due to a long time span, this article further narrows the sample interval to 2015–2019 in the robustness test. This excludes not only the influence of the sewage fee, but also various policies proposed by China in 2020, which can more accurately analyze the impact of the EPT on corporate ESG greenwashing. The results are shown in column (2) of Table 5, where the estimated coefficient of the policy effect is significantly negative, again demonstrating the robustness of the paper’s conclusion.

5.4.4. Sample Data Screening

In order to avoid bias in the regression results caused by the emergence of extreme values, the data are shrink-tailed by 1% up and down under the precondition that the sample size of this paper is large enough. However, due to the presence of a high number of outliers in the data, an additional 2% reduction in the top and bottom is performed to further exclude the effect of extreme values, and the model (1) is re-regressed. As shown in column (3) of Table 5, the estimated coefficient of DID is numerically similar to the benchmark regression results, with the same level of significance.

5.4.5. Control Province Fixed Effects

Beyond industry and time, ESG greenwashing may also be linked to the region in which it occurs. At the same time, there are significant differences among provinces in terms of policy environments, resource endowments, and infrastructure. To this end, this paper incorporates province fixed effects in the robustness tests to further enhance the accuracy of the model estimates. The regression result is shown in column (4) of Table 5.

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.5.1. Internal Firm Heterogeneity Analysis

Based on the screening of the nature of the actual controller, the firms in the sample are categorized into state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) for heterogeneity analysis. Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6 show the estimated results of the EPT on corporate ESG greenwashing for different ownership. From the perspective of SOEs, it does not pass the significance test, indicating that the EPT has no significant impact on the greenwashing of SOEs. From the perspective of non-SOEs, the estimated coefficient of the policy effect is −0.2615, which passes the significance test at the 1% level, indicating that the EPT significantly reduces the ESG greenwashing of SOEs by 26.15%. This may be because the interests of SOEs and the government are more closely linked, and the government usually has greater control and decision-making power over SOEs, which makes it easier to supervise the production behavior of companies; therefore, the EPT has little impact on its greenwashing. Non-SOEs have more flexibility and autonomy in government regulation, and it is difficult for the government to play a role in the implementation of regulatory measures of the same intensity, such as the implementation of sewage fees. However, the implementation of the EPTL, which has a high level of law enforcement, can effectively curb corporate ESG greenwashing.

Table 6.

Internal firm heterogeneity analysis.

As a result of the implementation of the EPTL, the production function of a enterprise will undergo certain changes. The relationship between various factors of production and the maximum output of the enterprise will be changed under certain conditions. In this paper, the firms are categorized by factors of production, and the results are shown in Table 6. They fail the significance test among labor-intensive enterprises, while in non-labor-intensive enterprises, the estimated coefficient of the policy effect is −0.2707, which is significant at the 1% level, indicating that the EPT significantly reduces the corporate ESG greenwashing by 27.07%. This may be due to the fact that labor-intensive firms rely more on manual labor in the production process than non-labor-intensive firms, suggesting that different types of firms will face different levels of increased tax burden under the EPT. Labor-intensive enterprises usually have outstanding adaptive ability and flexible adjustment ability. They are able to carry out industrial structure transformation and upgrading more flexibly under the EPT, so it has no obvious impact on corporate ESG greenwashing. Other enterprises, which are more sensitive to ESG performance as they are more reliant on market and investor support, may be more willing to invest resources to improve their ESG performance and reduce greenwashing in order to attract more investors and consumers.

5.5.2. External Firm Heterogeneity Analysis

In this paper, we take the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) measured by operating revenue to indicate the degree of competition for heterogeneity analysis. The bigger the HHI, the greater the degree of competition in the industry. We use the median of the HHI as the cut-off point to group the sample into high- and low-competitive industry groups for heterogeneity analysis, and the results are shown in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7. It can be seen that the estimated coefficient is negative in industries where competition is moderated and passes the significance test at the 1% level. This may be due to the fact that enterprises with moderate competition are more focused on long-term planning and development, with relatively less market pressure and competitive threats. Under the implementation of the EPTL, the cost of violating the law for companies has increased, thus making such enterprises more willing to invest more in environmental protection, further curbing the occurrence of corporate ESG greenwashing. Moreover, in a highly competitive industry, the complexity of market behavior makes it more difficult for regulators to monitor and combat ESG greenwashing.

Table 7.

External firm heterogeneity analysis.

Since the developed regions are mainly concentrated in the east-central region and the underdeveloped regions are concentrated in the western region, this paper divides the provinces where the listed companies are located into the east-central region and the western region according to the level of regional economic development and geographic location. The results are shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 7. It can be seen that, in the western region, the EPT has no significant effect on corporate ESG greenwashing. In contrast, in the east-central region, the estimated coefficient is significantly negative at the 1% level, with a significant inhibitory effect. This may be due to the fact that it is a more economically developed region in China, so the government attaches greater importance to its environmental protection and sustainable development. Meanwhile, the implementation of the EPTL provides clear guidelines for companies to follow, thereby helping reduce the occurrence of corporate ESG greenwashing.

5.6. Mechanism Tests

Through the analysis of the previous literature, it is concluded that the EPT has a driving role in reducing information asymmetry and promoting the green transformation of companies. But whether it can further reduce the greenwashing of companies is the issue to be studied in this paper. In order to explore the internal mechanism of the EPT on the influence of corporate ESG greenwashing, the specific model is constructed as follows:

where represents the mechanism variables, namely asymmetric information (ASY) and green transformation (Green). First, in this paper, with reference to Bharath et al. [34], the firm’s liquidity ratio indicator, illiquidity ratio indicator, and yield reversal indicator are extracted for principal component analysis. The first principal component is taken as a proxy variable for information asymmetry between banks and firms, denoted as ASY, with larger values of this indicator indicating greater information asymmetry between firms internally and externally. Second, since green transformation is an important way for companies to realize sustainable development, and total factor productivity measures the comprehensive index of production efficiency, this paper adopts the OP method proposed by Olley and Pakes [35] to estimate the corporate total factor productivity (Green) to measure the degree of corporate green transformation. The OP method is chosen due to the use of unbalanced panel data and the existence of firm exits during the sample period., Consequently, the OP method can better address the problem of selectivity bias compared to the LP method. Moreover, the ACF method is based on the premise that “labor is not a free variable”, but in terms of China’s actual situation, labor can be regarded as a free variable due to the relative lag of the labor protection system. In this paper, the OP method is used to study the total factor productivity of a firm, where operating revenue is used to measure total output, investment in net fixed assets, and the number of employees are used to measure capital and labor inputs, respectively. The amount of long-term assets purchased is treated as an intermediate goods input. By regressing the above variables, the residual obtained is the total factor productivity of the firm.

5.6.1. Information Asymmetry Mechanism

Information asymmetry is one of the key factors affecting the reduction in greenwashing of companies. The reduction in information asymmetry indicates that it not only enhances the efficiency of internal management of companies but also strengthens the competitiveness of companies in the market and promotes the sustainable development of companies. The existing literature suggests that several measures can reduce information asymmetry. These include lowering bond yields in the green bond market [36], strengthening environmental regulation, enhancing public and media monitoring capabilities [37], and improving the internal governance mechanism of the enterprise. Together, these can effectively reduce the corporate ESG greenwashing and promote the healthy development of green economy.

This paper further considers the impact of the EPT towards information asymmetry. Column (1) of Table 8 shows the result of the test of the information asymmetry mechanism. The result shows that the estimated coefficient of the EPT towards information asymmetry is −0.0714 and passes the test of significance at the 1% level. This indicates that the implementation of the EPTL effectively alleviates the problem of less access to truthful information faced by the relevant departments outside the corporation and the investor. It shows that the implementation of the EPTL has prompted companies to provide real environmental, social, and governance performance, prompted companies to continuously strengthen ESG management, and enhanced their profitability and solvency, which in turn has led to the reduction in greenwashing. In summary, the EPT reduces greenwashing through strict regulation, digital transformation, and tax incentives to alleviate the information asymmetry of companies, thus proving H2.

Table 8.

Mechanism tests.

5.6.2. Green Transformation Mechanism

Green transformation is one of the key factors affecting the reduction in corporate ESG greenwashing. An increase in the degree of green transformation indicates an increase in the overall competitiveness of the corporation and promotes sustainable economic development. The existing literature suggests that green transformation effectively inhibits corporate ESG greenwashing by strengthening the coordination between policy regulation and environmental information disclosure laws, enhancing public awareness of environmental protection [38], and actively seeking green investments and partners.

Column (2) in Table 8 shows the test result of the green transformation mechanism. The result shows that the estimated coefficient of the EPT on green transformation is 0.0472 and passes the test of significance at the 10% level, indicating that the implementation of the EPTL effectively promotes the green transformation. This may be due to the fact that the collection of the EPT is more standardized and stringent than that of the sewage fee. Under this system, companies can better demonstrate their ESG efforts and achievements. This enhanced transparency, in turn, helps enhance their awareness of environmental protection and their sense of responsibility. Therefore, we can optimize their governance structure and operational efficiency and thus enable them to reduce their greenwashing. To summarize, the EPT promotes corporate green transformation by enhancing their environmental and social responsibility image, thus curbing corporate ESG greenwashing and proving H3.

6. Further Study

6.1. Corporate ESG Performance and Greenwashing

The benchmark regression results in the previous section show that the EPT can help curb corporate ESG greenwashing, but it has not yet been compared between companies with different ESG performances. Therefore, in order to test the moderating effect of ESG performance on greenwashing, this paper introduces the interaction term between policy effects and moderating variables for empirical testing. The model is constructed as follows:

The results are shown in column (1) of Table 9. With the known significant negative correlation between the EPT and corporate ESG greenwashing, the cross-multiplier of policy effect and ESG performance is also significantly positively correlated with corporate ESG greenwashing. This indicates that the higher the ESG rating of the corporation, the stronger the inhibiting effect of the EPT towards corporate ESG greenwashing.

Table 9.

Further study.

6.2. Corporate ESG Rating Uncertainty and Greenwashing

At present, the ESG rating system has not yet formed the unity of the rating results. Different rating agencies have different rating methods and standards, and the ESG rating system varies greatly, which in turn leads to a weak correlation between the ESG ratings of different agencies for the same underlying company. On the one hand, the uncertainty of ESG ratings provides companies with room for greenwashing, so that companies may choose to exaggerate their ESG performance or adopt some superficial environmental protection measures to meet the requirements of rating agencies in the face of rating pressure. On the other hand, companies can take this opportunity to gain an in-depth understanding of the evaluation criteria and indicators of different rating agencies to identify their own shortcomings and potential for improvement in ESG compliance. In order to further study the impact of ESG rating uncertainty towards corporate ESG greenwashing, this paper constructs the following model:

This paper draws on Avramov et al. [39] to construct an indicator of ESG rating uncertainty (EU), and the estimation result is shown in column (2) of Table 9. The result shows that the estimated coefficient of the interaction term of the policy effect of the implementation of the EPTL and the uncertainty of ESG ratings do not pass the significance level test, indicating that the uncertainty of ESG ratings does not have a significant effect on corporate ESG greenwashing.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

7.1. Conclusions

Under the new development philosophy, exploring the micro effects of the implementation of the EPTL will be of great help to the improvement of China’s tax system and the realization of the carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals. This paper provides a basis for further promoting the improvement and development of the EPT in practice while accumulating an empirical basis for the next step of environmental regulation development. In order to clarify the impact of the EPT towards corporate ESG greenwashing, this paper takes the A-share listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen from 2015 to 2022 as the research sample for analysis. Based on the results of the study, the following conclusions can be drawn.

First, the EPT can curb corporate ESG greenwashing. Compared with before, the corporate ESG greenwashing has decreased by an average of 18.87% after the policy implementation. Moreover, this inhibitory effect is more obvious in non-SOEs, non-labor-intensive companies, low-competitive industries, and the east-central region. Second, the EPT can effectively curb corporate ESG greenwashing through two channels: reducing information asymmetry and promoting corporate green transformation. The implementation of the EPTL has effectively alleviated the problem of having less truthful information available to external authorities and investors, thereby enabling companies to reduce their corporate ESG greenwashing. Meanwhile, it effectively promotes the green transformation of companies, enhances their sense of responsibility, and equips them with strategies and capabilities to achieve sustainable development. Third, the higher the ESG rating, the stronger the inhibition effect of the EPT towards corporate ESG greenwashing. Moreover, the uncertainty of ESG rating does not affect the inhibiting effect of the EPT on corporate ESG greenwashing. In theory, it extends signaling theory by revealing how the EPT reduces information asymmetry and refines legitimacy theory by showing how existing ESG ratings strengthen the policy’s inhibitory effect on greenwashing.

7.2. Policy Implications

Based on these findings, the following policy implications are made. First, we should optimize the legal reward and punishment mechanism to promote the healthy development of companies. The EPT can effectively promote the reduction in corporate ESG greenwashing, but it must be ensured that the rate of reduction is appropriate. If a corporate ESG rating is to remain steadily improving at a certain rate, it will require a large number of in-house technicians to innovate and introduce state-of-the-art equipment while regularly training and supervising employees. In the short term, there is a relatively large increase in business operating costs and operating pressure. However, in the long term, companies will maximize profits. If a company excessively raises its ESG rating, resulting in a significant increase in its production volume, there may be potential problems, including a decline in product quality. Therefore, the legal reward and punishment mechanism must be continuously optimized. This involves addressing potential issues from the very source, at the stage of policy design. We should provide certain tax incentives to companies that meet environmental protection requirements to further encourage them to increase environmental protection investment and improve production efficiency and strengthen supervision and punishment for companies that do not meet environmental requirements and are heavy-polluting companies. This helps avoid quality problems at the service or product level and promote the healthy development of companies.

Second, we should alleviate information asymmetry to promote the comprehensive development of companies. On the one hand, we must vigorously develop ESG concepts, wildly promote the importance of ESG concepts through social media, and increase public awareness to ESG. On the other hand, ESG awareness and competence of investors should be continuously improved. We should encourage banks and other financial organizations to set up teams to research ESG investments. These teams should look into ESG investment strategies and methods and provide professional investment advice to investors. Meanwhile, China should actively participate in international ESG cooperation and exchange activities, learn from international advanced experience, and promote the international development of China’s ESG concept.

Third, we must accelerate the green transformation of companies to promote the sustainable development of companies. Green transformation requires efforts from both the government and companies. From an external perspective, the government should provide tax incentives for companies that have completed their green transformation and continue to encourage them to use advanced green technologies and digital platforms. From an internal perspective, although green transformation is a certain trend for companies at present, the specific path and method need to be determined by companies themselves. This requires them to invest a large amount of funds in green technology innovation. Promoting the green transformation of companies can improve the efficiency and comprehensiveness of supervision. In the digital age, this approach helps tackle critical challenges. It enables companies to promptly identify problems, minimize their environmental footprint, and avoid ESG greenwashing. Consequently, this contributes to the enhancement of total factor productivity and the realization of sustainable development for enterprises.

7.3. Discussion and Outlook

Our findings on China’s EPT offer a distinct perspective compared to Western regulatory models. We demonstrate that the EPT directly curbs corporate ESG greenwashing by creating a financial disincentive for pollution. This contrasts with the primary approach in many Western economies. They often focus on mandating and standardizing ESG disclosures to reduce information asymmetry for investors, such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). However, both approaches encourage businesses to align their actions with their environmental commitments.

A primary limitation of our quasi-natural experiment design is the focus on A-share listed companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen. This sample may not fully represent the vast number of unlisted or smaller enterprises in China, which may respond to the EPT differently. Furthermore, “ESG greenwashing” is a complex concept to measure. While this study provides a robust analysis, the metrics used to quantify greenwashing may not capture all its facets. Future research could develop more granular, industry-specific metrics for greenwashing.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.J.; Data curation, H.J.; Writing – original draft, J.L.; Writing—review & editing, J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund Project (23BRK002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhang, C.; Farooq, U.; Jamali, D.; Alam, M.M. The role of ESG performance in the nexus between economic policy uncertainty and corporate investment. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 70, 102358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobande, F. Woke-washing: “intersectional” femvertising and branding “woke” bravery. Eur. J. Market. 2020, 54, 2723–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Zhou, C.M.; Ma, Y.N. Impact mechanism of environmental protection tax policy on enterprises’ green technology innovation with quantity and quality from the micro-enterprise perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 80713–80731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.Z. Modelling the role of eco innovation, renewable energy, and environmental taxes in carbon emissions reduction in E-7 economies: Evidence from advance panel estimations. Renew. Energy 2022, 190, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchorzewska, K.B.; Garcia-Quevedo, J.; Martinez-Ros, E. The heterogeneous effects of environmental taxation on green technologies. Res. Policy 2022, 51, 104541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.; Oueslati, W.; Rousselière, D. Environmental taxes, reforms and economic growth: An empirical analysis of panel data. Econ. Syst. 2020, 44, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmenci, T.; Aydin, M. The effects of environmental taxes on environmental pollution and unemployment: A panel co-integration analysis on the validity of double dividend hypothesis for selected African countries. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.J.; Yue, X.G.; Liu, W.; Crabbe, M.J.C. Valuation impacts of environmental protection taxes and regulatory costs in heavy-polluting industries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.M.; Sun, S.F. Can environmental protection tax drive manufacturing carbon unlocking? Empirical evidence from China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1274785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.F.; Liao, L.X.; Yu, C.X.; Yang, Q.S. Re-examining the governance effect of China’s environmental protection tax. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 62325–62340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Zhou, W. The impact of green taxes on green innovation of enterprises: A quasi-natural experiment based on the levy of environmental protection taxes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 92568–92580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.L.; Meng, X. Environmental protection tax and green innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 56670–56686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.Q.; Yang, J.Y.; Liu, Z.Y.; Tan, Q.Y. Environmental protection tax and green innovation of heavily polluting enterprises: A quasi-natural experiment based on the implementation of China’s environmental protection tax law. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.K.; Zhang, C.Y. Environmental protection tax and total factor productivity-Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhu, X.B.; Zheng, H. The influence of environmental protection tax law on total factor productivity: Evidence from listed firms in China. Energy Econ. 2022, 113, 106248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H. China’s changing perspective on the WTO: From aspiration, assimilation to alienation. World Trade Rev. 2022, 21, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.T.; Lin, H.H.; Han, W.Q.; Wu, H.Y. ESG in China: A review of practice and research, and future research avenues. China J. Account. Res. 2023, 16, 100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.B.; Jin, G.; Tan, K.Y.; Liu, X. Can low-carbon city construction reduce carbon intensity?Empirical evidence from low-carbon city pilot policy in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 332, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Lin, Y.E. ESG, ESG rating divergence and earnings management: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3328–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.H.; Wang, Z.L.; Wang, G.; Zuo, J.; Wu, G.D.; Liu, B.S. To be green or not to be: How environmental regulations shape contractor greenwashing behaviors in construction projects. Sust. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A.; Robinot, É.; Trespeuch, L. The use of ESG scores in academic literature: A systematic literature review. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2023, 19, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, P.R.; Yu, T. A survey on ESG: Investors, institutions and firms. China Financ. Rev. Int. 2024, 14, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.X.; Li, X.X.; Xu, Q.F.; Liu, J.H. Does environmental protection tax impact corporate ESG greenwashing? A quasi-natural experiment in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 84, 774–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Zeng, T. Environmental “fee-to-tax” and heavy pollution enterprises to de-capacity. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.L.; Wang, S.J.; Cheng, X.; Zeng, H.X. Can environmental tax reform curb corporate environmental violations? A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s “environmental fees to taxes”. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 171, 114388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.Y.; Chen, Z.M.; Shen, Z.F.; Shabbir, M.S.; Bokhari, A.; Han, N.; Klemes, J.J. The effect of cleaner and sustainable sewage fee-to-tax on business innovation. J. Clean Prod. 2022, 361, 132287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, J.W.; Dai, Y. Analyst following and greenwashing decision. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugal, N.D.; Portugal, P.D.; Reis, R.P. Internalization of environmental costs in the financial management of organizations: A proposition to be applied in agribusiness. Custos Agronegocio 2012, 8, 171–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Fang, Q.; Wu, H.Y. Environmental tax and highly polluting firms’ green transformation: Evidence from green mergers and acquisitions. Energy Econ. 2023, 127, 107046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zou, W.D.; Zhong, K.Y.; Aliyeva, A. Machine learning assessment under the development of green technology innovation: A perspective of energy transition. Renew. Energy 2023, 214, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wen, J.; Wang, X.Y.; Ma, J.; Chang, C.P. Green innovation, natural extreme events, and energy transition: Evidence from Asia-Pacific economies. Energy Econ. 2023, 121, 106638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.Y. Green financial system regulation shock and greenwashing behaviors: Evidence from Chinese firms. Energy Econ. 2022, 111, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.S.; Lalonde, R.J.; Sullivan, D. Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1992, 83, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Bharath, S.T.; Pasquariello, P.; Wu, G.J. Does Asymmetric Information Drive Capital Structure Decisions? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 3211–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olley, G.S.; Pakes, A. The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 1996, 64, 1263–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.; Park, D.; Tian, S. The price of frequent issuance: The value of information in the green bond market. Econ. Chang. Restruct. 2023, 56, 3041–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, W.N.; Seppänen, V.; Koivumäki, T. Effects of greenwashing on financial performance: Moderation through local environmental regulation and media coverage. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2023, 32, 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Esposito, L.; Gatto, A. Energy transition and public behavior in Italy: A structural equation modelling. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, D.; Cheng, S.; Lioui, A.; Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 145, 642–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).