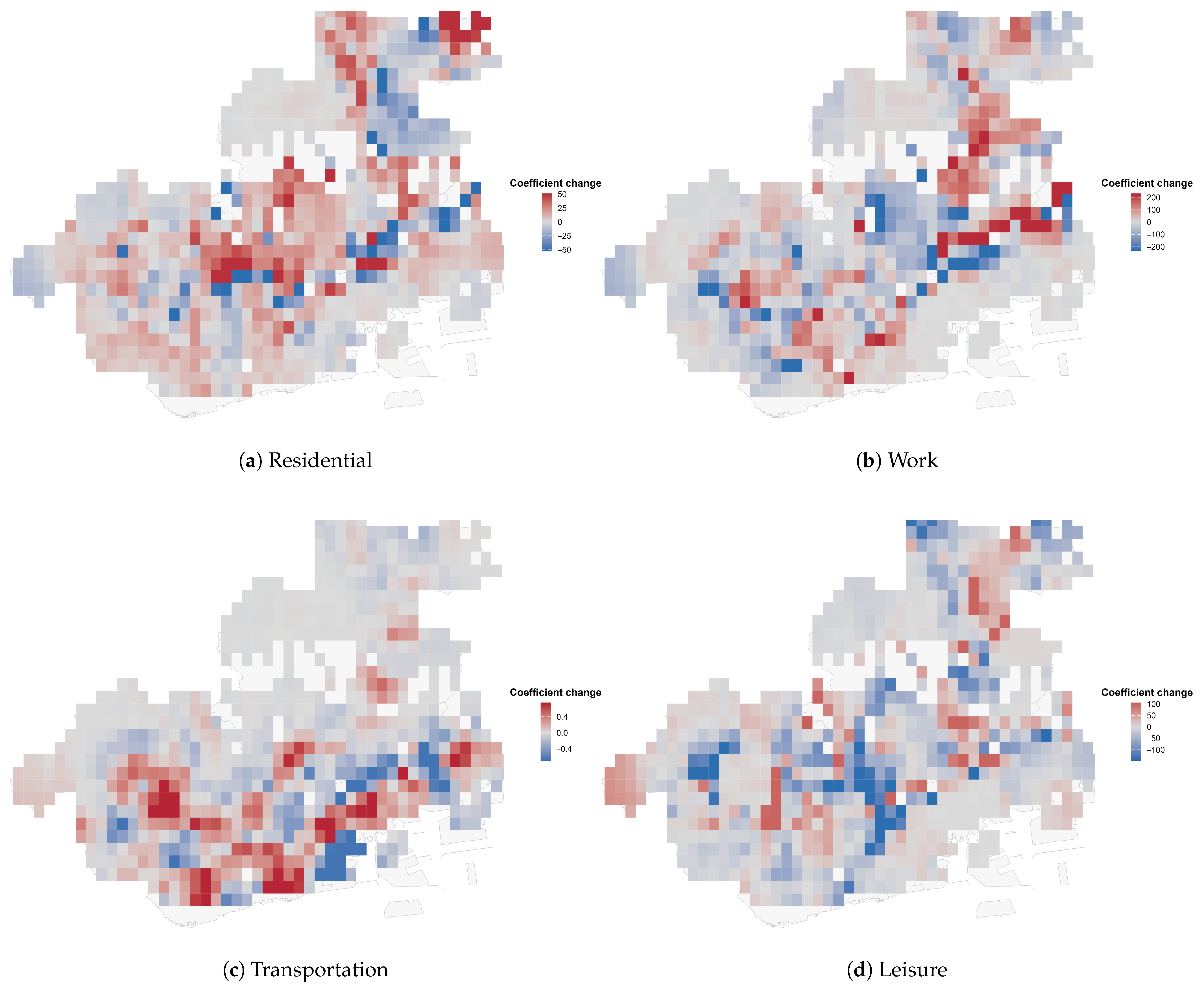

4.1. GWR Estimation

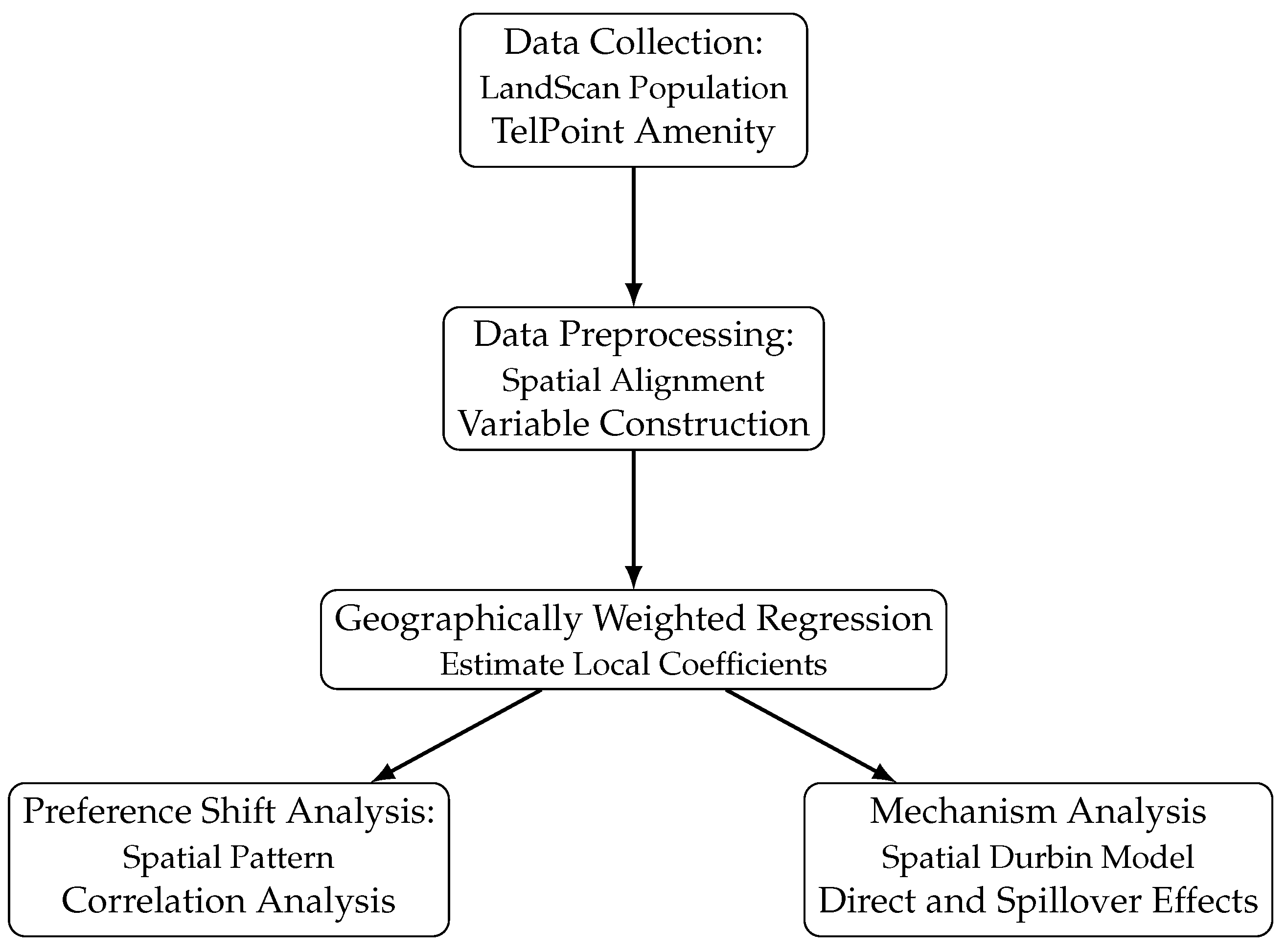

The evolution of amenity preferences is summarized by the GWR coefficient estimates across three groups: the full-sample average, the top cities, and the other cities. We report the group-wise average of the local coefficients in corresponding areas, as shown in

Figure 6. Each figure shows the average coefficient over time, with shaded bands representing the 10% confidence interval.

Overall, the GWR estimations reveal that top cities have experienced significant shifts in all preferences, while other cities only exhibit significant preference changes for the residential amenity, which has the most notable and consistent preference shift among all amenity types. Preference for residential functions shows a steady increase prior to the pandemic, and this trend intensifies following the COVID-19 outbreak. Specifically, in top cities, the average coefficient rises from 26.4 in 2019 to 31.7 in 2020, while in other cities, it increases from 26.8 to 28.8 during the same period. Notably, this elevated preference for residential amenities continues even after the relaxation of public health regulations in 2021, suggesting a persistent shift in urban residential preferences.

The evolution of the work preference coefficient reveals distinct patterns between the two city groups. In the top cities, a steady decline in preference for work-related amenities is evident even before the pandemic, with the average coefficient falling from 8.9 in 2016 to 4.9 in 2019. The outbreak of COVID-19 further accelerates this trend, as the coefficient drops to 2.8 in 2020 and reaches 1.9 by 2022. In contrast, the other cities exhibit a more moderate trend. The average coefficient for work amenities rises slightly from 2019 to 2020 and continues to increase modestly through 2022. This suggests that, in less dense or more peripheral cities, the decline in work-related preference is less pronounced, possibly reflecting different degrees of telework adoption or structural change.

The transportation amenity represents a key component of urban infrastructure, particularly in highly developed cities. The coefficients for transportation are expected to be negative, reflecting the population concentration whereby population density decreases as the distance from the transportation amenity increases (This coefficient is often referred to as a gradient, representing the extent of population concentration around a transportation amenity). As shown in

Figure 6, there is a notable divergence between the two city groups in terms of both intensity and temporal dynamics.

From 2016 to 2019, the population further concentrated around the transportation amenities in top cities, revealing a stronger demand for the transportation amenity, while such a trend cannot be observed among other cities. Following the outbreak of COVID-19, the preference for transportation accessibility drops sharply in the top cities, falling even below 2016 levels. While the coefficients partially recover from 2020 to 2022, they remain lower than the 2019 level. In contrast, the other cities experience only modest fluctuations, and overall preference for transportation remains relatively stable.

Turning to the leisure amenity, the estimated coefficients are initially negative in both groups. While this may appear unanticipated, given that amenities such as leisure, work, and transit are expected to increase utility, similar patterns have been documented in past research. For instance, Li et al. [

39] find that government amenities are negatively associated with population density in Xi’an, and Zeng et al. [

40] also report negative coefficients from GWR estimates.

The negative coefficient for leisure may be attributed to collinearity with other amenity types and limitations of the population data. In many cities, leisure, residential, and transportation functions co-locate within mixed-use centers rather than forming distinct zones [

43], making it difficult to isolate their individual effects. Additionally, the LandScan dataset captures 24-h ambient population without separating day and night. If interpreted primarily as residential presence, areas with active nightlife or entertainment functions may appear less populated, leading to a downward bias.

Between 2016 and 2019, the preference for the leisure amenity remains relatively stable, with a slight decrease in the top group and a modest increase in the other group. However, following the pandemic, a dramatic shift occurs: in top cities, the coefficient declines from 10.1 in 2019 to −18.2 in 2020, and, similarly, in other cities, it drops from −3.5 to −7.1. These results indicate that leisure-related spaces became substantially less preferred as residential locations during the COVID-19 period, likely due to reduced mobility, behavioral caution, or structural adjustments in urban lifestyles.

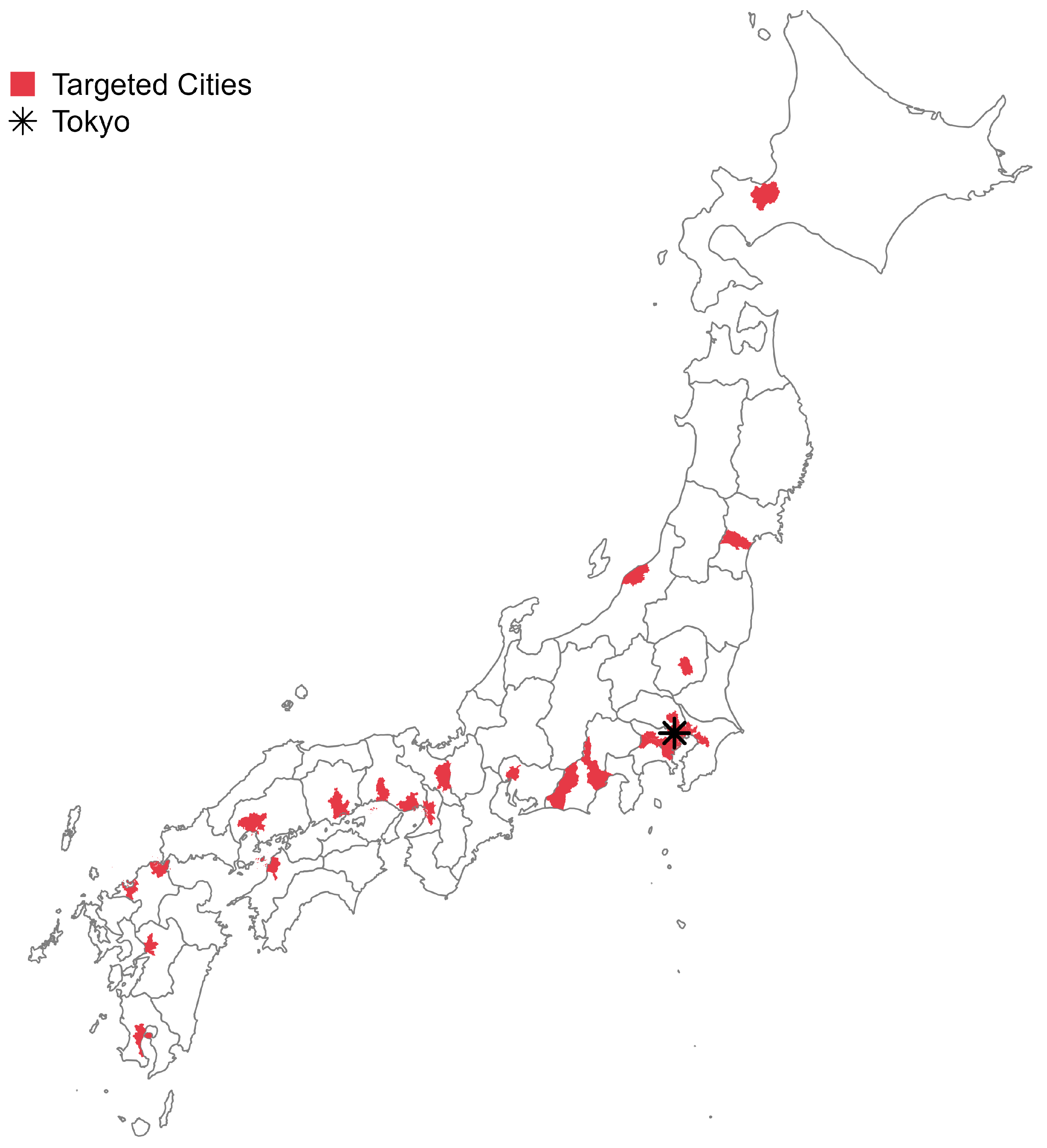

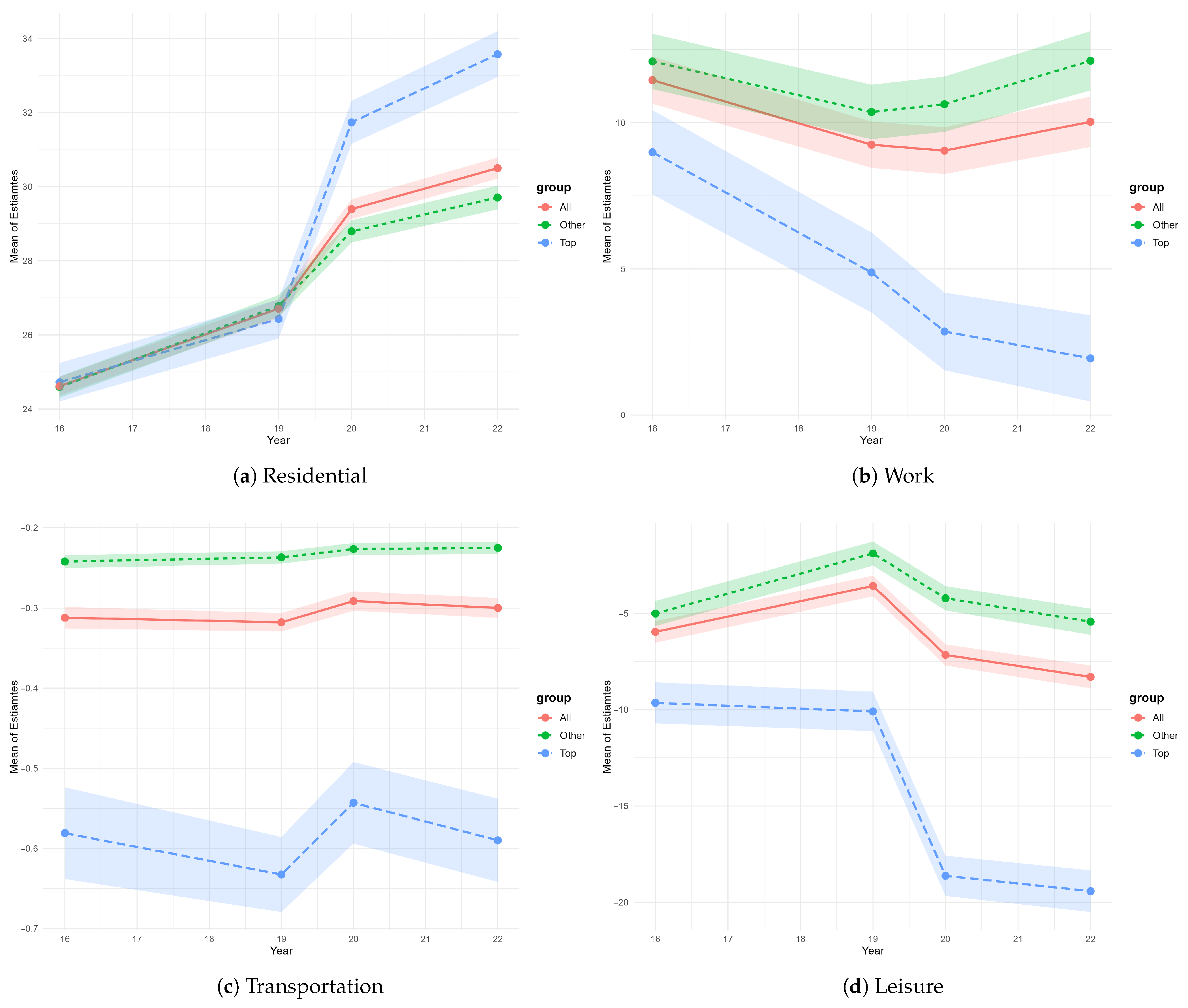

In addition, in

Figure 7, we document the geography of preference changes across Tokyo’s 23 special wards between 2019 and 2020. The estimated coefficient changes exhibit clear spatial clustering for all four amenity types. For residential, the changes are predominantly positive and significantly clustered, with the eastern (e.g., Edogawa ward) and southern (e.g., Ōta ward) wards, which are well-connected residential areas, showing particularly strong increases. In contrast, the central business districts of Chuo, Minato, and Chiyoda wards exhibit neutral patterns. Further, the dynamics for work-related amenities reveal an opposing spatial pattern. Preferences remain largely neutral in the central areas but generally decline in the suburban wards. Notably, the preference for transportation accessibility weakens in both the city center and distant suburban areas (e.g., Nerima in the northwest and Katsushika in the east). This decline in the suburbs, which typically rely heavily on transportation amenities for commuting, suggests that the widespread adoption of remote work may have reduced the demand for proximity to transportation amenities. Meanwhile, changes in preferences for leisure amenities are generally neutral to negative across the metropolitan area, with some residential wards experiencing more pronounced declines. Collectively, these spatial patterns provide implicit evidence of a major behavioral shift driven by the spread of remote work in megacities like Tokyo, indicating a population rebalancing from work-oriented to life-oriented priorities.

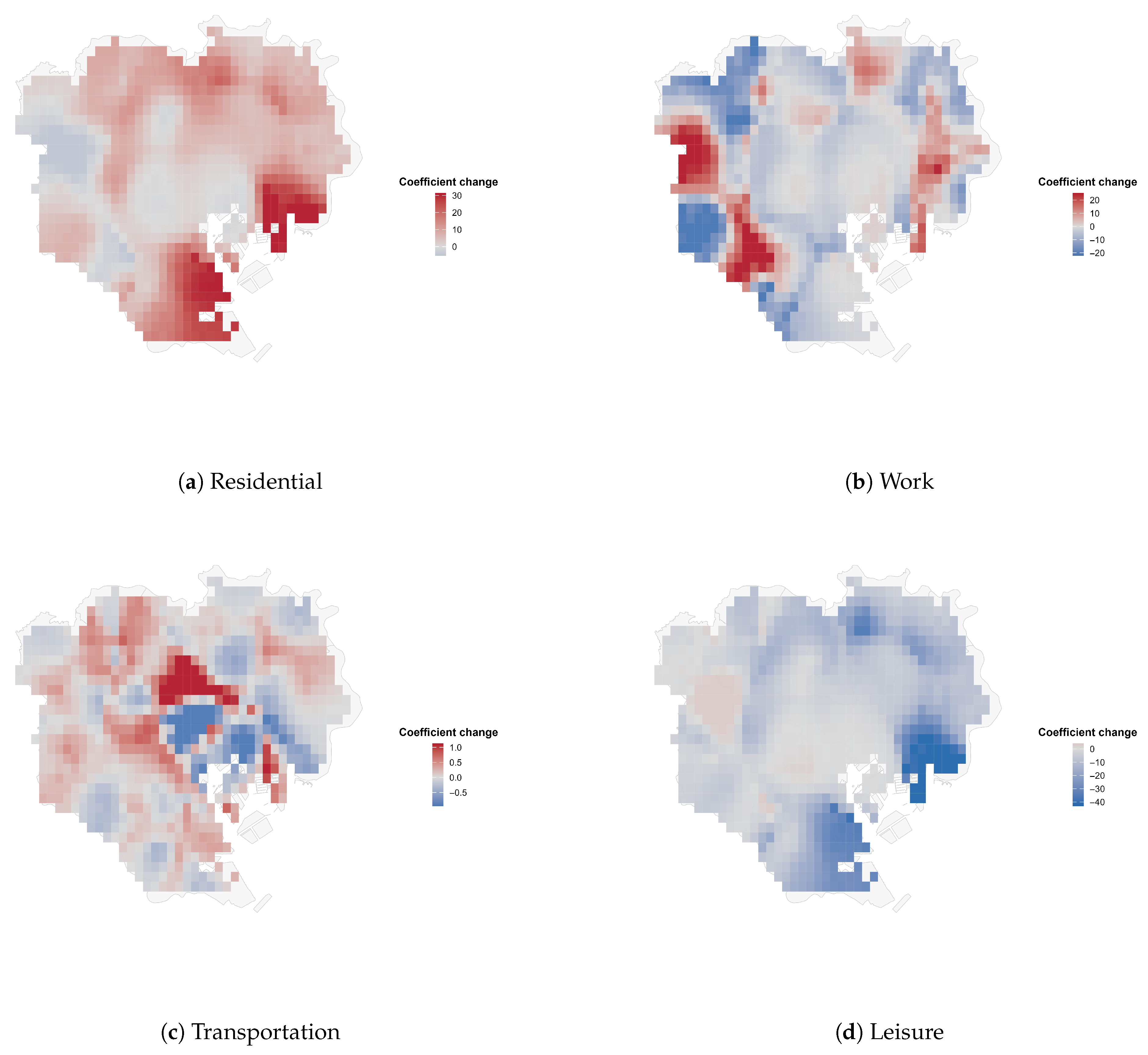

In contrast to Tokyo, we examine the changes over the same period in Kobe city, which is an important city in Japan, distinct from megacities like Tokyo and Osaka. The majority of activities and population are concentrated in the south of Kobe, and the Kita ward, namely the northern area, is predominantly residential.

Figure 8 exhibits Kobe’s preference shifts. The blank areas appear on the map due to data transformation and spatial merging procedures across different years. We observe that the preference shifts are mainly located in the southern areas, whereas the changes in the northern areas are less pronounced. Though the spatial autocorrelation in preference changes is also observable in Kobe, the patterns are substantially more random and less clustered than those observed in Tokyo. For instance, zones showing considerable decreases in preference are frequently adjacent to zones of increase, and vice versa, indicating a fragmented and heterogeneous pattern.

While the preceding analysis captures general statistical patterns, taking Tokyo and Kobe as examples to show the spatial heterogeneity of preference shifts within cities, substantial variation exists across individual cities. To illustrate this heterogeneity, we present the coefficient evolution over time for six top cities in

Appendix A.2, selected to represent diverse preference shifts.

4.2. Patterns of Preference Changes

The previous subsection highlighted overall shifts in amenity preferences and the spatial pattern of preference changes in Tokyo. Although we observe general preference shifts for corresponding amenity types, it is not necessary that these changes systematically co-occur. From

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, we can find significant spatial autocorrelation, and seemingly co-occurrence between changes in different preferences. Given such context, this section further examines the spatial patterns of these changes, focusing on the clustering of single preference changes and co-occurrence between preference changes at a more micro level.

To assess the spatial clustering of specific preference changes, Moran’s I statistics are computed for each amenity type. The index ranges from −1 to 1, where positive values indicate spatial clustering (similar values located near one another), negative values suggest dispersion (dissimilar values nearby), and values near zero imply random spatial distribution.

As shown in

Table 3, Moran’s I values are reported separately for the top, other, and full-sample groups. The results indicate that preference changes in the top group exhibit stronger spatial clustering, especially for residential, work, and leisure amenities. In contrast, changes in preference for transportation accessibility show weaker spatial autocorrelation in the top group than in the other group.

Although the average Moran’s I values across amenity types appear similar, notable variation exists at the city level.

Appendix A.3 provides examples from Tokyo and Osaka that illustrate this inter-city divergence.

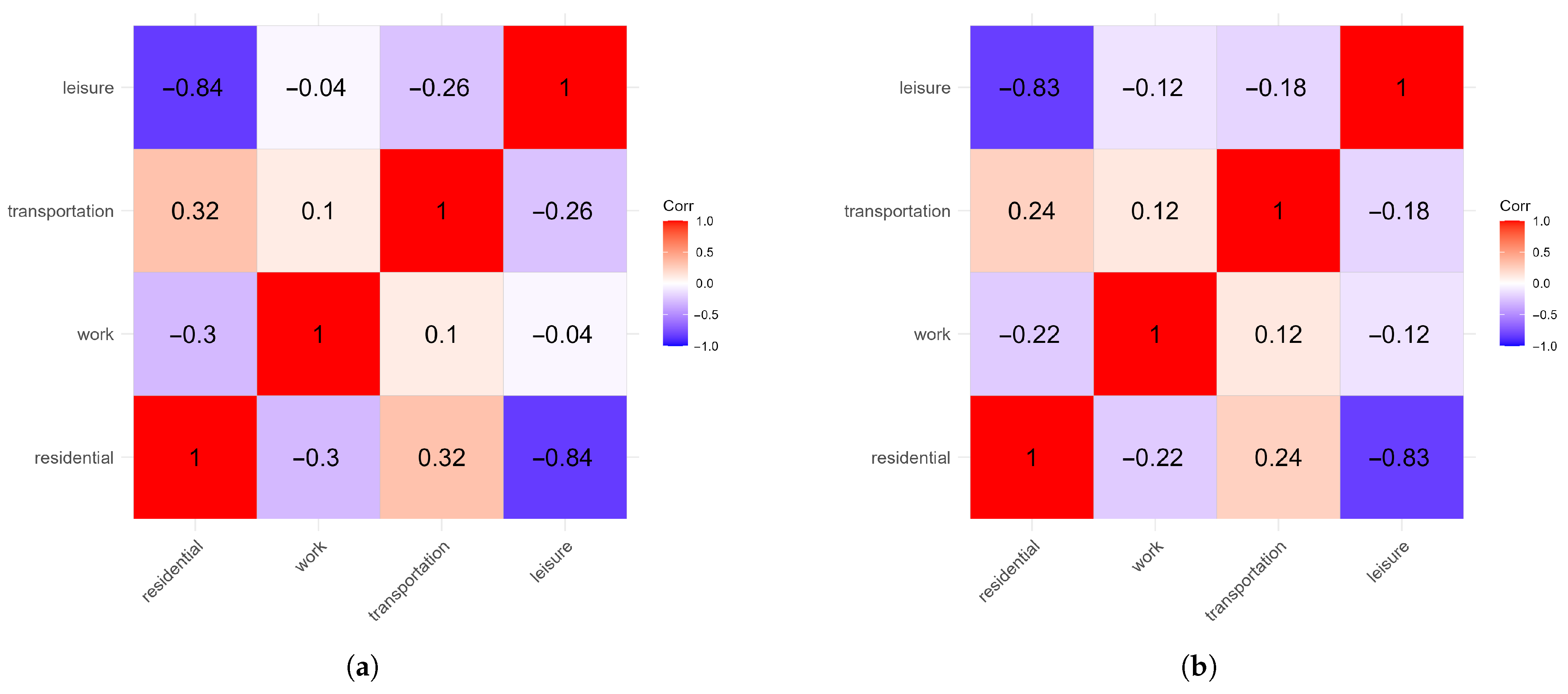

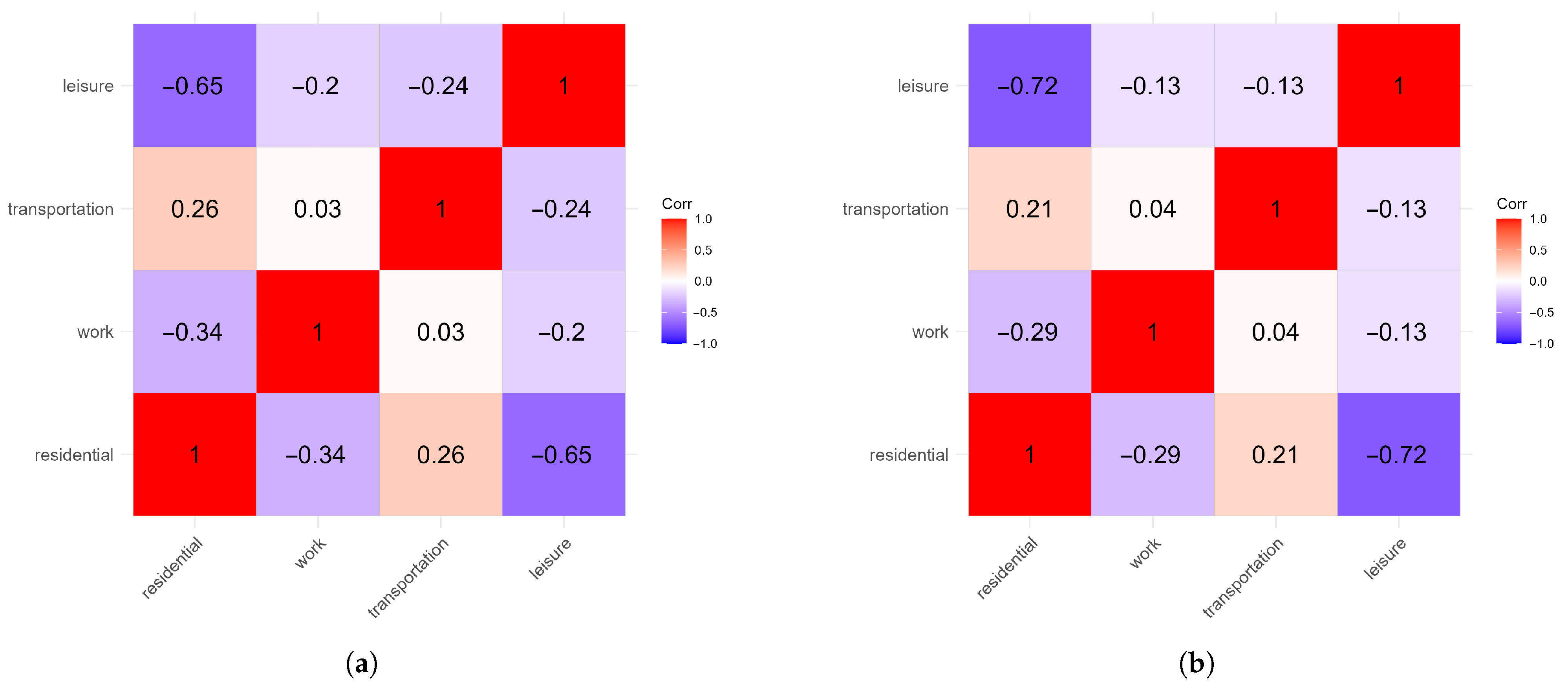

After examining spatial autocorrelation, we investigate the interdependence of preference changes using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. This metric captures linear relationships between variables, with values ranging from −1 to 1. A positive value indicates a direct correlation, while a negative value suggests an inverse relationship. The correlation matrices, presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, are symmetrical, with diagonal entries equal to 1, reflecting perfect self-correlation. Correlations above 0.7 are considered strong, those between 0.3 and 0.7 are moderate, and values below 0.3 are weak.

In the case of the top group, three pairs of variables exhibit at least moderate correlations in the short run, all involving the residential amenity. The strongest is the negative correlation between residential and leisure, indicating that areas with increasing preference for the residential amenity tend to show declining preference for the leisure amenity. This pattern aligns with the GWR estimates. Additionally, a moderate positive correlation is observed between residential and transportation, and a moderate negative correlation is observed between residential and work. In the long run, only the negative correlation between residential and leisure remains strong, while the other associations weaken considerably.

Compared with the top group, correlations between preference dynamics in the other group are generally weaker, suggesting that preference changes occur more randomly in these cities. As shown in

Figure 10, only two pairs of variables exhibit at least moderate correlations: residential and leisure, and residential and work. In the long run, the correlation between residential and work decreases slightly to 0.29, falling just below the moderate threshold, while the negative correlation between residential and leisure becomes even more pronounced.

Although our results in the previous subsection confirm substantial preference changes overall, they do not necessarily indicate that these preference changes occur in tandem. Notably, Pearson correlation coefficients reveal that preference changes in the residential amenity are closely aligned with those of other types. This pattern underscores the centrality of residential considerations in shaping urban preferences, reflecting consistent and comprehensive changes in lifestyle after the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.3. Mechanism of Preference Changes

After identifying the spatial patterns of preference changes, we next investigate the underlying mechanisms. According to the Lagrange multiplier (LM) test and the robust LM test, there is evidence of significant spatial autocorrelation in both the independent variables and the dependent variables. Therefore, we apply the SDM to account for these spatial dependencies. The model is specified as follows:

where

denotes the post-pandemic preference change at location

i for a specific amenity type, and

represents the local amenity vector. The terms

and

capture spatial lags of the dependent and independent variables, respectively. The spatial weight matrix

W is constructed using the 4-nearest neighbors. Since observations from cities in the same group are estimated together, unobservable city-specific factors may exist. To control for such heterogeneity, city fixed effects

are included. Given that the dependent variable is derived from GWR-based preference estimates, the model is exploratory in nature. It aims to uncover correlations rather than establish causal relationships and provides insights into the spatial structure of amenity-related preference changes.

Following LeSage’s introduction [

44], the coefficients in the explanatory variables can be interpreted through a decomposition framework. The direct effect reflects the influence of local variables, while the indirect effect (or spillover effect) is captured by the spatial lag terms. Furthermore, the coefficient

in the spatially lagged dependent variable represents residual spatial autocorrelation, often arising from omitted variables (That is, if the dependent variable is sufficiently explained by the direct and indirect effects of the independent variables,

should be small or statistically insignificant [

45]).

From the SDM results, we focus on two key aspects: the spatial autocorrelation intensity of the preference changes and the direct and indirect effects of local amenity conditions on these changes. The estimation results are collected in

Table 4 and

Table 5.

Consistently positive spatial autocorrelation appears across all estimates. Moreover, the estimated values are systematically higher in the top cities than in the other cities. This suggests stronger unobserved spatial linkages in large urban regions. Such latent factors likely reflect the complexity of urban systems in top-tier cities, including denser infrastructure networks and more intricate socioeconomic interdependencies. Given these dynamics, the explanatory power of observable amenity indicators may be limited, with the residual spatial patterns captured by . In contrast, the urban structure of smaller cities tends to be less complex, making the role of observed amenities more suitable for explaining preference changes. As a result, the spatial autocorrelation that cannot be explained by the model is generally weaker in the other group.

Regarding the coefficients of amenity variables, we observe a consistent pattern across both amenity types and city groups: the local amenity is negatively associated with corresponding preference changes while the surrounding amenity is positively correlated. This result can be explained by the mechanism of saturation, whereby the marginal utility of an amenity declines as its local concentration increases; that is, residents in already amenity-rich locations may not perceive additional value, whereas those in amenity-scarce areas gain more.

Conversely, the positive coefficients in surrounding amenities suggest a spatial spillover effect: areas adjacent to amenity-rich zones tend to experience stronger increases in preference over time. This reflects the benefits of amenity proximity: residents in nearby areas enjoy access to amenities without bearing the full burden of congestion, noise, or other associated costs (Current studies suggest that local amenities and accessibility do not always lead to stronger preferences [

46], and that the costs of rich amenities, such as congestion and noise, can sometimes reduce residential attractiveness [

47]).

Furthermore, we find that the magnitudes of both local and neighboring coefficients are larger in the other group. This suggests that amenity distribution has a greater influence on preference changes in smaller cities. Two factors may explain this pattern. First, as noted previously, top-tier cities possess richer amenity resources, which likely lead to saturation effects, reflected in the smaller coefficients. Second, recognizing that coefficient magnitude does not necessarily imply explanatory power, this finding is consistent with the larger values observed in the top group. In contrast, preference changes in the other group are more effectively explained by both local and surrounding amenity conditions.

In summary, the SDM analysis reveals several important insights. First, spatial autocorrelation remains significant, particularly in top cities, where unobserved spatial structures appear more complex. Second, consistent local saturation and positive spillover effects are observed in both city groups, while the coefficients of both local and spillover effects in other cities show a larger magnitude. These findings underscore the heterogeneous nature of preference evolution and emphasize that the complex social and economic connections in top cities make preference changes more unpredictable.