Abstract

The statistics indicate a significant growth in the global organic food industry. This growth impacts rural economies, employment, and the rural landscape, affecting the structure, services, and amenities available to the rural population. Most of the Bulgarian municipalities have rural characteristics. The primary objective of this study is to analyze and assess the impact of organic farming on rural development and to formulate recommendations for fostering a stronger relationship between organic agriculture and rural regions in Bulgaria. Due to the complexity and comprehensiveness of this study’s primary objective, the authors employ a combination of three methods: statistical analysis (correlation, regression, and chi-squared), a survey focused on consumer attitudes towards organic products, and a SWOT analysis. There is a strong correlation between the expansion of organic production, the demand for such products, and the rural regions’ development. A significant positive correlation (r = 0.678044) has been demonstrated between the number of enterprises and the number of people employed in rural regions. The frequency of purchasing organic products is increasing, with 28% of consumers using these products in 2014 and over 45% expected to do so in 2024. Based on the SWOT analysis, the authors outline key recommendations in four areas in the context of strategic rural policy: stimulating demand, stimulating supply, stimulating and expanding production, and improving the legislative framework.

1. Introduction

The organic food industry has witnessed significant growth worldwide, particularly in the European Union (EU) and the United States. This growth has influenced rural economies, employment, and the rural landscape as structure, services, and amenities for the rural population. Between 2012 and 2020, the EU saw a more than 50% increase in organic farmland, reaching 9.1% of the total agricultural area [1]. This expansion was supported by policies such as the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), which incentivized farmers to adopt organic practices. Countries like France, Spain, Italy, and Germany accounted for the largest share of organic land use [1]. Similarly, in the United States, organic food sales exceeded $60 billion in 2022, reflecting a strong consumer preference for organic products [2].

The organic food industry has made significant contributions to environmental sustainability and rural economic development [3,4,5,6,7]. Organic farming plays a crucial role in this by enhancing soil health, mitigating land degradation, and fostering biodiversity. However, challenges related to productivity, regulation, and market stability persist. Increased investment in research, improved policy frameworks, and consumer education are essential for the continued growth and impact of the organic and bio food sectors.

The organic and bio food industries significantly impact rural economies by generating employment and increasing farm incomes. Organic farming often fosters local supply chains, supporting small-scale farmers and reducing dependency on global agribusiness corporations [5]. Studies have shown that organic farms tend to be larger and are more frequently managed by younger farmers compared to conventional farms [1]. Furthermore, the organic food market has experienced significant growth, with the global sector valued at over $120 billion in 2022 [8].

Between 2007 and 2022, the area used for organic farming increased in all EU countries, but Bulgaria’s increase was among the lowest [9,10]. According to Eurostat data for Bulgaria on organic crop area by agricultural production methods and crops as a percentage of total utilised agricultural area, including total fully converted and under conversion to organic farming for the period 2014–2020, the rate increased from 0.3% in 2014 to 1.91% in 2020 [9]. The increase in the share of land fully converted to organic agriculture is a positive trend; however, the growth rate is very low. There is a steady upward trend in the percentage of the arable land fully converted to organic production, from 0.18% in 2014 to 1.08% in 2019 [11,12]. In 2023, the share of total areas under organic production methods in Bulgaria was 2.95% of the utilized agricultural area [12]. By 2023, the areas fully converted to, or in the process of conversion to, organic farming had increased from 47,914 thousand hectares to 147,798 thousand hectares, representing a 99,884 thousand hectares increase, or a 3.1-fold increase. The average annual growth in regions that have been completely converted or are in the process of conversion to organic farming over the period is 11,098 thousand ha, with an average annual growth rate of 13.33% [10,12].

In the context of global climate change, Bulgaria is transitioning from a temperate continental to a subtropical climate, altering the potential for agricultural production. On the other hand, due to the country’s geographical characteristics, agriculture is a significant sector of Bulgaria’s economy, closely tied to rural areas. Two-thirds of Bulgaria’s municipalities are rural. Naturally, food is produced there, and the arable land used for organic farming is growing. At the same time, Bulgaria has a strategic location between Europe and Asia, and due to climate change, there will be a growing demand for food in parts of Asia and Africa. Bulgaria can actively participate in global food supply chains that maintain food security. On the other hand, Bulgaria has been slower than other European countries to adopt organic farming, which makes it an interesting subject for study. The development of organic farming in Bulgaria has seen significant growth in the years since the country joined the EU, as there are high-quality land resources, suitable climatic conditions, traditions in agricultural production, ecologically preserved areas, and, on the other hand, opportunities to support organic producers through the Rural Development Programs in Bulgaria. Most economic activities related to the production of organic products are located in rural municipalities and areas across Bulgaria. Therefore, it is essential to examine the relationship between growth in organic production and the development of rural regions in Bulgaria. This sector is entirely focused on rural areas, which have the opportunity to strengthen their role and position in the national economy, thereby improving their socio-economic situation. In the Bulgarian and global scientific literature, there is insufficient research on the impact of organic farming on rural areas. Specifically, there is a lack of studies analyzing the correlation between organic agriculture and rural areas in Bulgaria.

As part of the Common Agricultural Policy and the implementation of the European Green Deal, organic farming plays a vital role in the circular economy of agriculture [13,14,15,16]. Green economy and related policy measures not only protect the environment but also provide essential economic benefits through resource security, economic stability, and the creation of green jobs [15]. Due to the breadth of this topic, the authors focus on organic agriculture in Bulgaria in the context of European integration and convergence. Of course, organic farming is one element of the overall policy for building a green economy in rural areas. More broadly, this concept promotes the sustainable development of regions, especially rural ones. In line with the new green policy, the EU is transforming food chains into sustainable models. This model suggests that a shift in consumer attitudes is necessary to increase the consumption of organic food [17,18].

Consumer demand for organic products must be seen through the prism of sustainable development, where economic activities are being modified to achieve high environmental standards, and on the other hand, these products are linked to improving the quality of life and health of the population, which can be taken into account in changing their attitudes towards this type of food [19,20,21].

An essential instrument in rural development policy (essentially regional policy) is the creation of conditions for the development of organic farming. In this sense, regional policy for rural areas must create conditions and opportunities for the development of organic agriculture and demographic strengthening. This targeted policy is complemented and multiplied by local policies that aim to create a favorable environment by providing basic services such as infrastructure and communications, electricity and water supply, education, healthcare, and others. Here, we would like to pay special attention to water supply and water resource management, which are crucial for both population reproduction in rural areas and the development of organic farming. That is why water-sector management in rural areas is critical for sustaining the organic food market and promoting sustainable regional development [22]. These are some of the global challenges in implementing regional policy for rural development [23]. The sustainable development of European and Bulgarian regions is crucial for combating climate change, alleviating poverty, and retaining populations in rural areas. Sustainable regional development in rural regions encompasses a set of measures and activities designed to enhance demographic growth and improve the quality of life for rural populations across Europe. The biggest challenge facing this policy is the persistent trend of depopulation and aging in rural areas of the EU. This process is even more pronounced in Bulgaria, which lags significantly behind in its development. In this sense, one of the instruments to reverse the trends at the European and Bulgarian levels is by applying a targeted policy for regional sustainable rural development.

The research focuses on analyzing rural areas and their transformation driven by the growth of organic production in Bulgaria. More specifically, the authors examine the correlation between organic agriculture and rural development in Bulgaria as a tool for influencing change. Thus, the above research field requires an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing the regional development of rural areas in Bulgaria. Based on the accumulated theoretical experience, the authors systematize three main research approaches and methods—the analysis of the organic agriculture-rural areas relationship; the study of changing attitudes towards the consumption of organic products; and the application of SWOT analysis for the formulation and implementation of the most effective policies to stimulate organic agriculture and rural areas. The authors therefore employ all three methods to cover the main aspects. First, the status and changes in socio-economic and demographic terms in rural areas, driven by organic farming, are identified using specific indicators. Secondly, the authors analyse how changes in the market for Tacoma products stimulate organic agriculture and rural areas. Finally, policy improvement measures are logically proposed based on the strengths and weaknesses of this sector and the rural regions.

The information for the analysis of the leading indicators for organic production in Bulgaria and for some key indicators for the economic development of rural areas during the study period is based on official statistical information from the Ministry of Agriculture and Food [12] (the national register of producers, processors, and traders of agricultural products and organically produced food), Eurostat [9] (organic crop area, organic crop production, organic livestock production, Research Institute of Organic Agriculture [10], National Institute of Statistics [11] (main economic indicators at NUTS 2 and NUTS 3 level.

2. Context of This Study

In Bulgaria, interest in healthy food has been growing significantly in recent years, accompanied by a corresponding increase in demand. This has led to a growing need to expand organic farming and produce high-quality, safe, and environmentally friendly food. A retrospective study of the development of organic farming in Bulgaria reveals that it has experienced significant growth since the country’s accession to the EU. Its development is due, on the one hand, to the availability of quality land resources, suitable climatic conditions, and the traditions of agricultural production, as well as the preservation of ecologically sensitive areas. On the other hand, it is also due to opportunities to support organic producers under the Rural Development Programmes. The development of organic farming meets the requirements of environmental protection and the effects of food production, promoting the sustainable development of the agricultural sector and aligning with the objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy and the Green Pact.

For the period 2014–2020, organic cereal production exhibited a steady upward trend, increasing from 7671 thousand tons in 2014 to 48,079 thousand tons in 2019. Notably, almost half of the 2014 production (3014 thousand tons) came from wheat and rye [9]. Organic production of industrial crops also increased, from 6572 thousand tons in 2014 to 34,985 thousand tons in 2020. Organic fresh vegetable production in 2014 was 9,705 thousand tonnes, rising to 20,179 thousand tonnes, then decreasing to 13,185 thousand tonnes in the following years. Compared to 2014 values, organic fruit production quadruples from 3.622 thousand tonnes to 19.995 thousand tonnes in 2020; however, the trend then decreases, reaching 15.874 thousand tonnes in 2023. According to Eurostat data available for Bulgaria on processed organic products for 2018, 2019, and 2020, the following stand out: processed and preserved fruit and vegetables 6162 tonnes, 5700 tonnes, and 9725 tonnes respectively, production of vegetable and animal oils and fats 336 tonnes, 3449 tonnes, and 63344 tonnes respectively.

The number of organic operators in the country in 2007 was 339, with significant growth in the following years, reaching 7262 in 2016. Since 2017, there has been a downward trend in the number of organic operators, with 6405 in 2019, a decrease of 857 (11.8%) from 2016 [12]. The reasons for the reduction in the number of organic operators are multifaceted—from bureaucratic difficulties to high costs for certification, control, training and equipment, insufficient level of information on funding opportunities, etc., and ending up with COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in significant restrictions leading to changes in work organization, disruption of supply chains, problems with product sales, a deteriorating economic environment, and other factors that have had a negative impact despite the support measures taken with national and European funds [24].

That is why, in the study, the authors note that the number of people moving to larger urban centers has increased significantly. Rural regions are being abandoned by young, educated individuals seeking greater job opportunities and better living conditions, resulting in an aging population [25]. To reverse these negative trends and effect change, long-term planning, strategies for sustainable development and smart growth, promotion of local initiatives, regional cooperation, and improvements to transportation and social infrastructure are needed.

People migrate from rural areas due to lagging economic development, weak entrepreneurial activity, insufficient investment, and limited opportunities for education, employment, professional fulfillment, and career development. One opportunity for sustainable rural development is organic farming, which encompasses a variety of agricultural products, including aquaculture and yeast production. In practice, organic farming development covers all stages of the production process, from seed production to the final processing of agricultural products intended for consumption. Ahlmeyer and Volgmann’s analyses of rural area development trends and opportunities confirm these conclusions. These analyses demonstrate how various indicators, including economic, technological, social, environmental, and others, impact rural development. The studies also show that these differences have led to significant differentiation between rural areas, which underlies their distinction into prosperous and underdeveloped regions [26]. The authors consider the transition to a green economy a significant challenge for rural areas but also an opportunity, as many industries do not heavily pollute these areas. Organic production utilizes technologies with minimal environmental impact and relies on renewable energy sources. Transport links to economic centers are essential for rural areas. These centers are not only potential markets for organic products, but customers can also visit organic farms, observe the growth of the products, sample them, and make purchases. Visitors can also explore other sites in the area. These activities contribute to improving socioeconomic conditions in rural areas by increasing employment and income, as well as improving access to education, healthcare, and social activities [27]. Strengthening the links between rural areas and economically developed centers creates favorable conditions for expanding trade, stimulating local economies, and reducing regional disparities and inequalities [28].

3. Opportunities for the Application of Organic Farming for Rural Development in Bulgarian Conditions Under European Integration

There is limited research in the global scientific literature that analyzes the relationship between organic production and rural development. This argument is strengthened by the fact that the Bulgarian case is particularly unique and necessitates a distinct approach to researching and analyzing the literature. The focus of the theoretical analysis is on reviewing the literature that examines the relationship between organic production and rural areas within the context of ongoing regional policy in Bulgaria. Few studies in the world’s scientific literature analyze the relationship between organic production and rural development. This argument is strengthened by the fact that the Bulgarian case is particularly unique and necessitates a distinct approach to research and literature analysis. The focus of the theoretical analysis is a review of the literature examining the relationship between organic production and rural areas in the context of regional policy in Bulgaria.

Several Bulgarian scholars, including Doitchinova, Nikolova, Stoyanova, Petrova, and Stanimirova, have conducted research on rural development issues in Bulgaria. Their studies have examined employment, human resources, demographic processes, agricultural income sources and levels, integrated and balanced regional development, territorial balance, and agricultural land use [29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. In Bulgaria, the impact of economic centers on the development potential of rural areas in the northwest and north-central regions has been empirically demonstrated. Indicators such as the age dependency ratio, population density, average annual wage of employees under labor and civil service contracts, and unemployment rate are higher in municipalities within these centers, and the business environment is more favorable [36]. The problems outlined above that affect rural development are characteristic not only of Bulgaria but also of many other countries. Their assessment must be based on a comprehensive analysis of an indicator system that characterizes economic, demographic, social, and environmental phenomena and processes. This study focuses on analyzing key indicators of demographic processes and economic development.

The development of the organic food industry in Bulgaria has been the subject of several research studies, particularly concerning its impact on rural areas. These studies highlight the interplay between institutional frameworks, market dynamics, and rural development [26].

One significant study by Slavova, Moschitz, and Georgieva examines the evolution of organic agriculture in Bulgaria from 1990 to 2012 [37]. The research indicates that the sector’s initial growth was predominantly driven by consultancy NGOs and academic institutions, with limited direct involvement from farmers. This top-down approach resulted in policies that were politically motivated rather than grounded in the economic and social realities of rural communities. The study suggests that the inclusion of farmers in policy networks, especially following the introduction of EU subsidies, was crucial for the sector’s development [38].

Similarly, Stoeva examines the institutional development of organic agriculture in Bulgaria, highlighting the challenges associated with a top-down approach [38]. The research indicates that, despite the implementation of supportive policies and financial instruments, only approximately 1.1% of Bulgaria’s agricultural land was organically managed during the study period. Moreover, a significant portion of organic produce was destined for export, indicating a lagging domestic market. The study emphasizes the importance of policies that not only offer financial support but also foster local market development and community engagement in rural areas [26,39].

Terziev and Arabska explore the potential of organic production and community-supported agriculture (CSA) in promoting sustainable rural development [40]. They argue that organic farming, when integrated with CSA models, can enhance food quality and safety while simultaneously bolstering rural economies. The study emphasizes the importance of alternative food networks and community engagement in promoting sustainable agricultural practices that benefit rural communities.

Furthermore, Otouzbirov, Atanasova, and Nencheva discuss the state and opportunities for the sustainable development of organic farming in Bulgaria [41]. They highlight that, despite favorable conditions such as ecologically preserved areas and growing consumer awareness, the sector’s growth is hindered by challenges, including limited institutional support and underdeveloped local markets. The authors advocate comprehensive policies to address these challenges and fully realize the potential of organic farming to enhance rural development.

Collectively, these studies suggest that while Bulgaria’s organic food industry holds promise for rural development, its success depends on inclusive policymaking, robust local market development, and active community participation. All the above-mentioned studies emphasize the role of organic farming in promoting sustainable rural development through policy frameworks, market dynamics, and community involvement. Here are the main research topics and discussions concerning the interplay between organic farming (organic value chain) and rural development:

Arabska examines the opportunities for sustainable rural development in Bulgaria by encouraging organic production [42]. The study highlights the importance of integrating organic farming into state and local strategies to enhance rural economies and promote environmental sustainability.

Arabska discusses improvements to the national strategic framework for organic production and management in Bulgaria [43]. The research identifies the main factors influencing the growth of the organic sector and its contribution to sustainable rural development, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive policy approach. Arabska, Dimitrov, and Ivanova examine the trends in organic farming development in Bulgaria by applying circular economy principles to sustainable rural development [42,44]. The study examines the growth of organic operators and areas, offering recommendations to promote the organic sector as a sustainable business model.

Petrova proposes an innovative organic agriculture model for the sustainable development of rural areas in Bulgaria [45]. The study suggests that organic farming can unlock untapped potential in rural areas, thereby contributing to socioeconomic development and resource conservation.

The organic food industry makes a significant contribution to environmental sustainability by enhancing soil health and biodiversity. Organic farming practices, including crop rotation, composting, and the use of natural fertilizers, improve soil fertility and mitigate land degradation [46]. Additionally, reducing synthetic chemicals helps preserve local ecosystems and enhance biodiversity, which is crucial for maintaining balanced, resilient rural environments.

By eliminating synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, bio food production minimizes water and air pollution, leading to cleaner environments in rural communities [19]. Moreover, organic farming has been linked to lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional agriculture. However, some studies indicate that organic systems may require more land to achieve the same yield as traditional farming, potentially offsetting the environmental benefits [20].

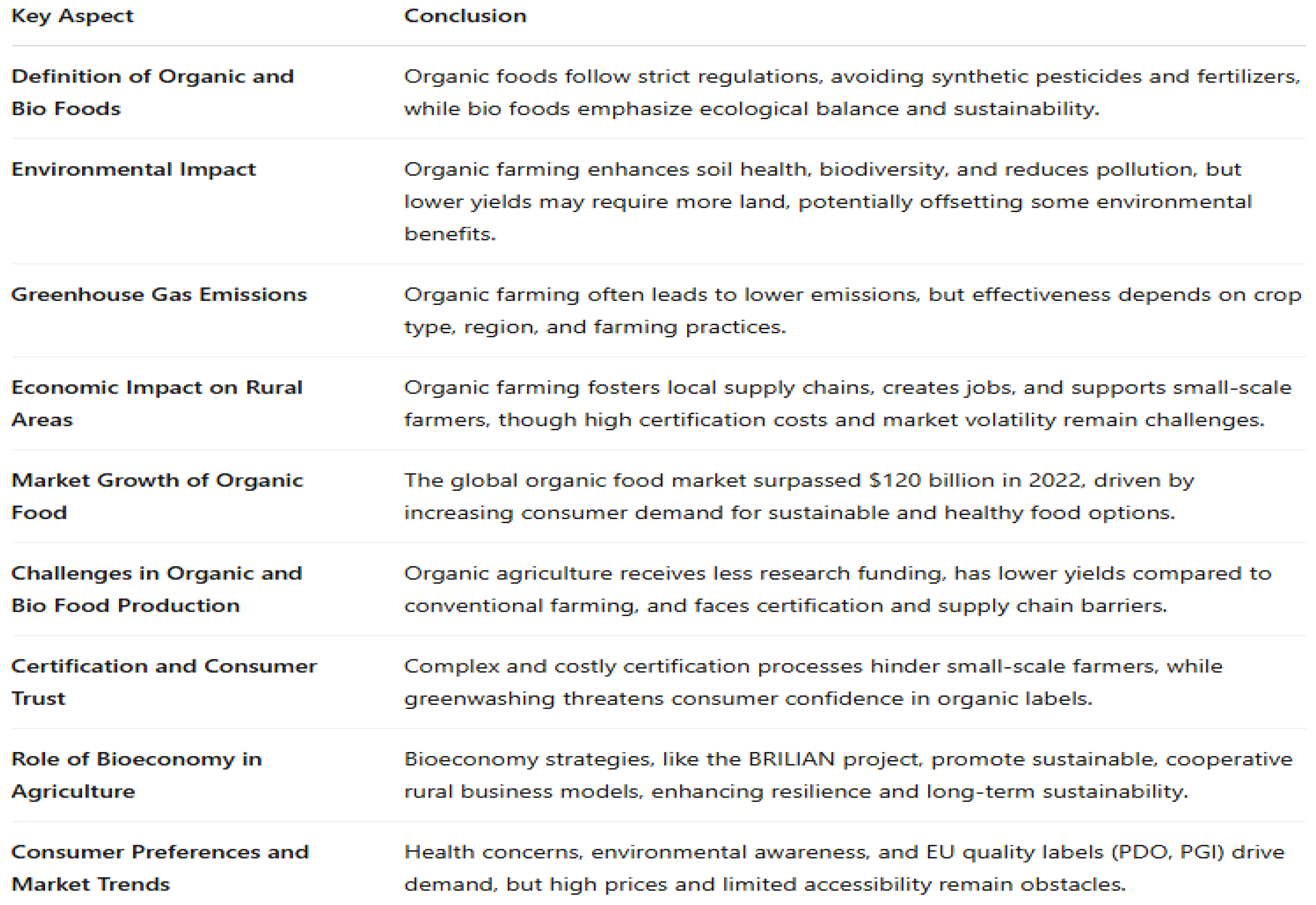

Collectively, these studies suggest that the organic food industry in Bulgaria has the potential to make a significant contribution to sustainable rural development. However, this potential can be fully realized through comprehensive policy support, market development, and active community participation. The organic food industry has become a crucial component of sustainable agricultural systems and rural economies. It plays a significant role in promoting environmental conservation, economic resilience, and social well-being in rural areas. The following topics in Figure 1 examine the interplay between the biofood industry and rural development, focusing on environmental, economic, and social dimensions.

Figure 1.

Key aspects in the interplay between the organic food industry and rural development. Source: own interpretation, based on literature review.

Due to the specific nature of this study, which examines the interaction between organic production and rural regions through the prism of Bulgarian conditions, it is logical to analyze mainly Bulgarian authors, with references to studies from other countries. It is striking that there are not many similar publications. Nevertheless, Figure 1 highlights the main points of contact between the development of organic farming and rural areas. A thorough analysis of similar studies reveals that some authors acknowledge the importance of organic agriculture and view it as a means to promote rural development. In a similar study, the authors classify European countries into clusters based on the interaction between environmental sustainability and socioeconomic development [47,48]. Thus, the main challenges facing Bulgaria are related to the socio-economic sustainability of its territories, mainly rural areas. Socio-economic development in rural regions can be achieved by stimulating organic production. This circumstance is reinforced by the agricultural nature of much of Bulgaria’s regions [26].

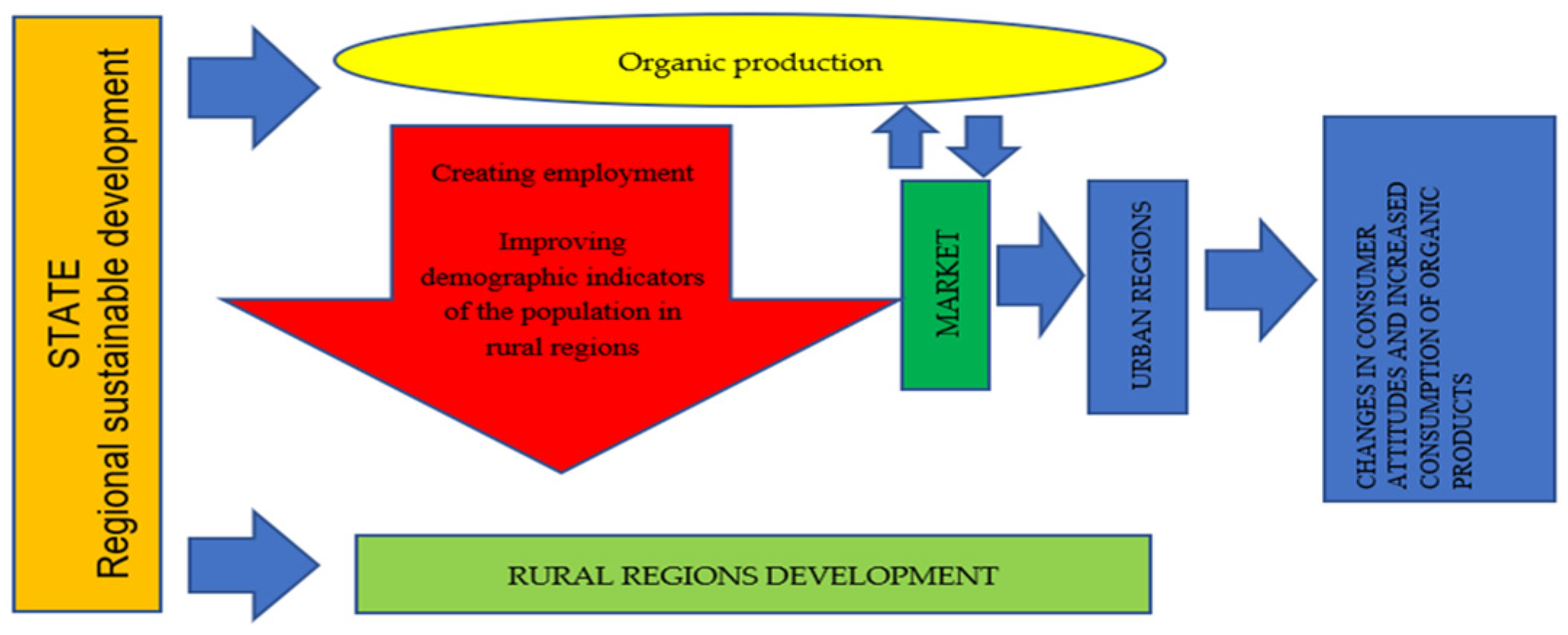

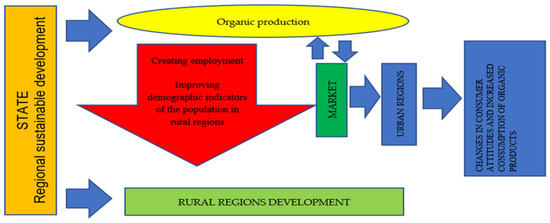

The bio food industry provides significant economic opportunities for rural populations. Organic farming tends to be labor-intensive, requiring more hands-on management than conventional farming, thereby creating jobs and reducing rural unemployment [49,50]. Additionally, the industry supports local economies by encouraging small-scale farming, reducing reliance on global agribusiness corporations, and fostering local supply chains [51]. In Figure 2, the authors present their interpretation of the systemic link between organic production, government policies promoting organic farming in rural areas, changes in consumer attitudes, the dynamics of the organic product market, increased production, and sustainable development in rural areas. State, regional, and municipal policies impact the economic ecosystem and stimulate economic activity (including organic farms in rural areas) [52]. The scheme illustrated in Figure 2 outlines new directions for regional policy that could be implemented in rural areas [53]. The figure is a synthesis of several studies from other countries that examine the relationship between organic farming and sustainable development in rural areas [51,54,55,56,57]. Organic farming influences processes in rural areas by increasing the attractiveness of areas that require additional investment and reducing regional disparities [56,58,59,60]. This investment policy is part of a broader strategy to create a circular economy [55]. However, it is impossible to develop rural areas through the promotion of alternative agriculture without an active, targeted policy in both regions by the state [51,54].

Figure 2.

The theoretical framework of the interaction between organic agriculture and rural development. Authors’ theoretical interpretation.

Based on the literature review and selected set of research methods, the authors formulate three research hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1.

There is a significant difference in the demographic characteristics of the population living in rural and urban municipalities.

The demographic characteristics of the population in rural and urban areas differ significantly. Severely deteriorated demographic indicators characterize the population in rural areas. The regional differences between the two groups of territories are significant [61,62,63].

Hypothesis 2.

The influence of the socio-demographic characteristics of the population by place of residence, age, and education on the consumption of organic products.

The active population and those living in large cities are the primary consumers of organic products. This trend indicates a shift in consumer attitudes toward organic products, which in turn has a positive impact on the development of rural areas [64,65,66]. Identifying consumer attitudes is an integral part of research related to the development of organic production and the stimulation of rural regions [64,67].

Hypothesis 3.

The development of organic farming has a substantial positive impact on rural development.

Based on several studies, the authors assess and verify the extent to which the development of organic production and targeted policies influence the revitalization of rural areas. Economic indicators are examined to evaluate the relationship between organic production and the rural regions [57,68,69,70,71,72]. Here, we can refer to studies on Denmark, where there has been an increase in employment in 16 peripheral municipalities in the country, thanks to the increased production of biofuels in these areas [69,73]. A similar study analyzes small and medium-sized enterprises in agriculture in Uzbekistan. In it, the authors define “bio-regional policies” aimed at rural development [74]. The authors observe an increase in agricultural enterprises and organic food production, which they attribute to government policy and rural development. Similar initiatives and policies should be developed and implemented in rural areas to support their maintenance and development. These policies are innovative and promising from the perspective of applying sustainable development concepts and advancing the bioeconomy on a global scale [75,76]. In this sense, one opportunity for rural development is to use the concept of bioeconomy as an innovative approach to stimulating rural areas [62,77].

Theoretically, this study is based on three main conceptual strands. In practice, the topic of exploring the relationship between rural development and the expansion of organic production has not been widely analyzed in Bulgaria. Some studies in this field focus on analyzing demographic, territorial, and economic indicators to understand the dynamics of organic farming and its impact on rural development [24,30]. Our study examines the relationships between the organic sector and demographic and economic dynamics in rural communities. The second area encompasses a theoretical framework that examines consumer attitudes and market development for organic products [64,65,66]. The third area of research consists of the use of SWOT analysis. Organic food production in Bulgaria is stimulated not only by increased government funding but also by the growing demand for this type of food. Concerns about health, sustainability, and food quality stimulate consumer demand for organic and organically produced food.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Methodology

The primary objective of this study is to analyze and assess the impact of organic farming on rural development and to formulate recommendations for fostering a stronger relationship between organic agriculture and rural areas. Due to the interdisciplinary nature of this study, the authors use a combination of three research methods: statistical analysis of demographic and economic indicators related to organic production and rural areas; sociological research on consumer attitudes towards organic products and the development of the organic market, and thirdly, a SWOT analysis to identify problems and outline not only opportunities for growth but also recommendations for the implementation of policies to stimulate the organic sector in rural municipalities in Bulgaria.

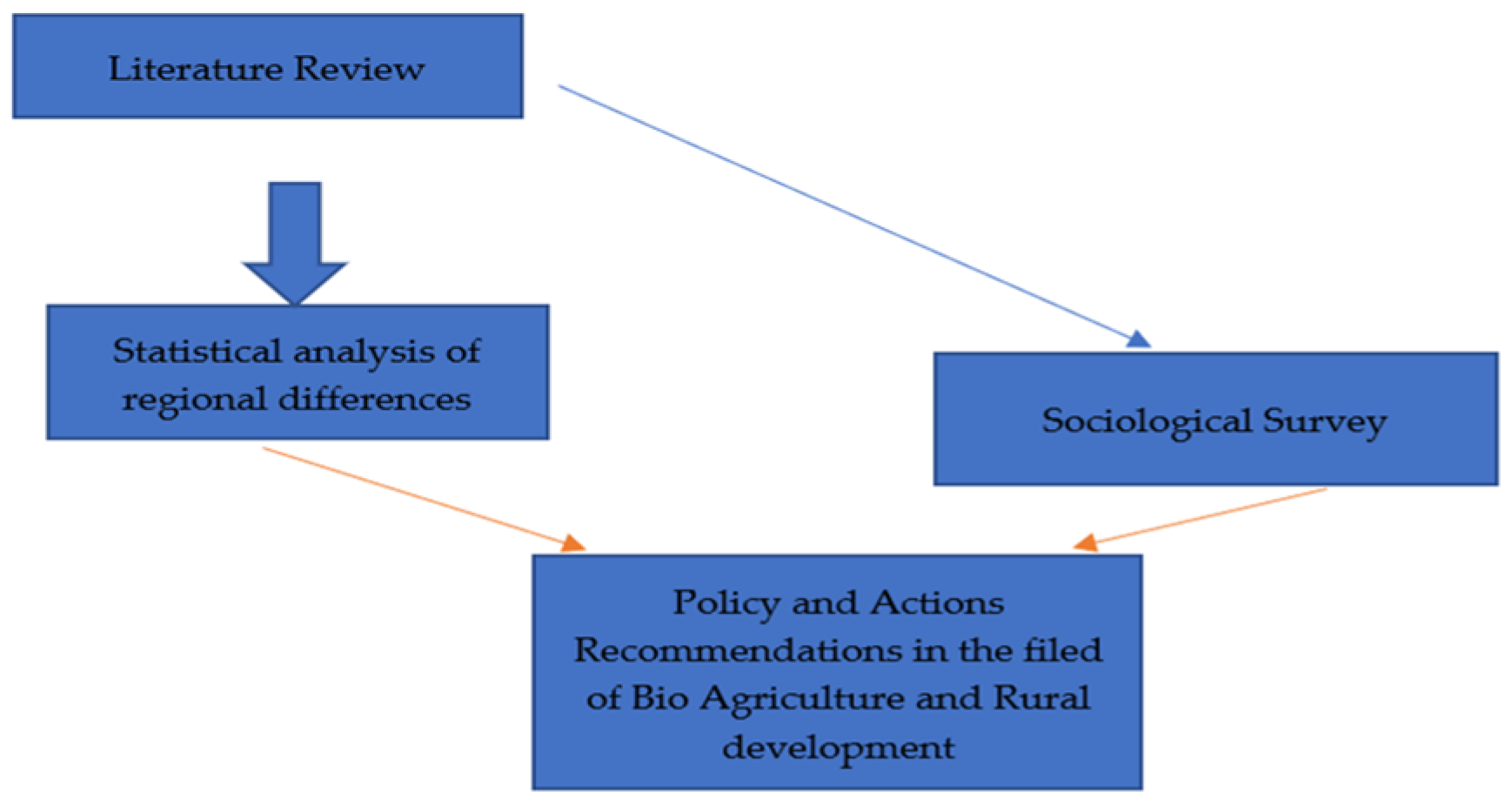

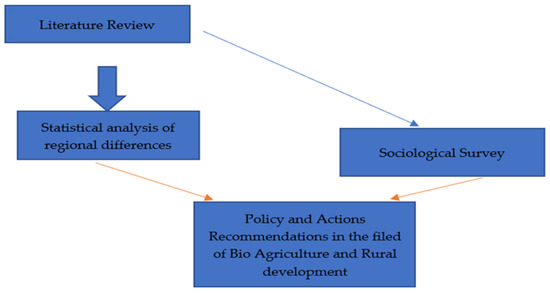

The methodological approach of this study is original mainly because the authors follow a working algorithm they have developed themselves (Figure 3). Based on the theoretical review, a synthesis of the main trends and problems in development is made, and the most appropriate demographic and economic indicators are selected to highlight regional differences in rural areas.

Figure 3.

Research methodology and research approach to the topic.

The second stage of this study analyzed the dynamics of the organic product market and consumer attitudes. Changes in consumer attitudes and market developments are assessed by comparing the same questions asked in 2014 and 2024. Market dynamics and changes in consumer attitudes toward organic food are essential to both promoting organic farming and developing rural areas. Based on statistical analysis and the results of the sociological survey, the authors systematized the questions addressed to experts in organic farming and rural areas in Bulgaria. The experts completed a SWOT matrix that not only identified problems and opportunities for the development of organic agriculture and, consequently, rural areas, but also systematized recommendations for the state to implement targeted policies and actions in both areas (Figure 3).

4.2. Statistical Methods of Analysis

Statistical methods, including time-series analysis, single- and multiple-linear regression, and correlation, are employed in the paper. The trend in indicator changes is analyzed using time-series statistics that meet the requirements for comparability in terms of time, place, unit of measurement, method of calculation, methodology used, and chronological consistency, as well as the inclusion of a sufficient number of years. For the analysis period 2014–2023, the average absolute growth and the average growth rate have been calculated. The presence of a trend in the time series was assessed using the first-order autocorrelation coefficient (r1), and the trend was modeled using the least-squares method [46,78,79].

Regression and correlation analysis are used to assess the strength and form of the dependence between the phenomena and processes under study. The factor and outcome variables analyzed are quantitative (variational), and therefore single- and multiple-linear regression and correlation are applied. Single correlation coefficients, coefficients of determination, and multiple correlation coefficients are calculated. The adequacy of the regression models was assessed using Fisher’s test of adequacy (F), and the regression model parameters were tested for statistical significance at the 0.05 significance level [78,80,81]. Regression models are statistically significant at Significance F < 0.05, and the parameters of the regression equations are statistically substantial at p-value < 0.05 [82]. The calculations were performed using MS Excel.

4.3. Survey

The survey was conducted from 2013 to 2024 and involved 244 respondents who completed the same questionnaire. The goal is to identify changes in attitudes towards buying organic products and the dynamics of the organic product market. The food chain in Bulgaria comprises three leading players, which are defined as the target groups for this study.

The survey covered the following groups of respondents: producers, distributors, and consumers, who are segmented by place of residence, age, gender, education, and occupation. The goal is to identify changes in attitudes towards buying organic products and the dynamics of the organic product market. The food chain in Bulgaria consists of three leading players, which are defined as target groups for the study.

4.3.1. Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire was developed based on a literature review in the field of organic farming. It aims to analyze the intention to purchase organic food products [65,66,83,84]. The final questionnaire includes 20 questions. Six questions measure attitudes and purchase intentions, with two focusing on awareness and knowledge of organic products. Seven questions relate to market development and sector competitiveness, while the remaining five provide descriptive data on the respondents. The data collection method is a survey, and the information gathering techniques are personal interviews and self-completion of an electronic questionnaire.

4.3.2. Sample

In conducting the survey, a segmented nested sample was drawn. It encompasses all stakeholders involved in the food chain, including producers, distributors, and consumers. The consumer part of the sample targets respondents from major administrative centres in Bulgaria. The part of the sample covering producers and distributors is territorially segmented by planning regions in Bulgaria. The consumers surveyed were 180 respondents, distributed as follows: Sofia (18.44%), Plovdiv (13.52%), Stara Zagora (8.60%), Burgas (10.65%), Varna (11.88%), Shumen (5.32%), Pleven (3.68%), and Vratsa (1.63%). The age distribution of users is as follows: 10.24% are in the age group up to 29 years; 13.34% are respondents between 29 and 39 years; 12.29% are between 40 and 49 years; between 50 and 59 years, and over 60 years are 16.39% and 20.49%, respectively. Regarding educational qualifications, the respondents were distributed as follows: 12.29% held a high school diploma, 24.59% had a bachelor’s degree, 32.78% held a master’s degree, and 4.09% held a doctorate (Appendix A, Table A1).

The portion of the sample that represented producers was distributed territorially as follows: the Northwest region accounted for 7.89%, the North Central region accounted for 15.78%, the Northeast region accounted for 23.68%, the Southwest region accounted for 21.05%, the South Central region accounted for 18.42%, and the Southeast region accounted for 13.15% (Appendix A, Table A3). The data on the gender distribution of the producers shows that 81.57% of the sample were male. The distribution of producers by age was as follows: up to 29 years (5.26%), 30–39 years (15.79%), 40–49 years (23.68%), 50–59 years (28.95%), and 60 years and above (26.32%). The prevalence of Master’s and Bachelor’s is 36.84% and 55.26% respectively.

4.4. SWOT Analysis

In the third stage of this study, experts in the field were interviewed, and the results were analyzed and evaluated using SWOT analysis. The interaction between the two factors is assessed through a comprehensive SWOT analysis [85].

The SWOT analysis method is one of the most widely used approaches in academic literature for assessing the potential of an organization, product, or service to ensure its successful market positioning [86,87,88]. This technique requires an in-depth understanding of all specific factors that directly or indirectly influence the organization, allowing them to be analyzed in detail and enabling the business model to be effectively adapted to their requirements.

This method involves several phases: phase A, identifying strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, which is carried out through focus groups and participants discussions; phase B, developing a SWOT matrix based on the previous phase; phase C, identifying the most significant factors for the sector’s competitiveness; the factors are rated: 0—no interaction, 1—weak interaction, 2—strong interaction, 3—powerful interaction; a four-point rating scale is used with the following values; four types of interactions between the factors in the matrix are examined; phase D, the interactions between the factors in the SWOT matrix are determined.

The methodology draws upon the Quadruple Helix model, which emphasizes the integration of four sectors —academia, industry, government, and civil society—in innovation ecosystems [89]. This model aligns with participatory governance approaches, ensuring the generation of inclusive knowledge. The process also draws on principles of strategic planning and stakeholder theory, emphasizing transparency, diversity, and ethical integrity [90,91].

The sequence of the SWOT analysis involves the following stages:

- Defining the Objectives and Scope. The first step is to clarify the purpose, geographical scope, and thematic focus of the SWOT analysis. These parameters determine the necessary competencies among the experts [92].

- Identification of Expert Profiles. Expert profiles are derived from the Quadruple Helix sectors: Academia, Researchers in agroecology, agricultural economics, and organic systems; Business, Organic producers, processors, and sectoral associations; Government, Policymakers and regulatory bodies; Civil Society, NGOs, consumer groups, and certification authorities.

- Selection Criteria. Experts are evaluated based on a competency matrix, including:

- ✓

- Minimum five years of relevant experience.

- ✓

- Advanced academic qualifications.

- ✓

- Authorship of publications or strategic documents.

- ✓

- Institutional and geographical diversity.

- ✓

- Declaration of no conflict of interest.

- Identification Strategies. Candidate identification includes public calls, targeted invitations, and institutional nominations. This hybrid approach ensures both inclusivity and relevance [93].

- Evaluation Procedure. A selection committee applies a scoring rubric to assess each candidate across predefined criteria [77]. Scores determine the final composition of the expert group, which is optimized for both thematic and regional balance.

- Ethical Considerations. All selected participants must sign the following documents: Consent to Participate, Declaration of No Conflict of Interest, and Confidentiality Agreement (if applicable).

5. Results

5.1. Analysis of Key Demographic and Economic Indicators for Municipalities and the Potential for Developing Organic Farming

Bulgaria’s rural areas account for approximately 22% of the country’s territory, encompassing around 13% of the population. Agricultural land occupies 41% of Bulgaria’s territory, and the farm sector accounts for approximately 4% of the country’s gross value added, employs over 6% of the workforce, is highly export-oriented, and has a positive trade balance in agricultural trade. The two poorest regions in the EU, the North-West and the North-Central, are located in the country. According to the National Plan for Agricultural and Rural Development, under the Rural Development Programme, rural municipalities are defined as all municipalities without a settlement with a population exceeding 30,000. The development of rural areas in Bulgaria faces numerous challenges, including demographic, economic, social, and infrastructural issues.

The demographic situation in rural areas is characterized by a declining population, a high proportion of elderly individuals, low birth rates, migration to larger cities and abroad, and low population density. In the period 2014–2023, the population of about 80% of Bulgarian municipalities decreased, with growth recorded in large cities, such as Sofia, Plovdiv, and Varna, as well as in some smaller municipalities on the outskirts of large cities, due to their proximity to economic centers [52], the development of tourism and creative industries [55]. There has also been an increase in inequality, with municipalities in Northern Bulgaria lagging behind those in Southern Bulgaria in almost all indicators.

In rural areas, low-value-added industries predominate, enterprises have a low level of modernisation, agriculture has a significant share in the local economy (the share of enterprises in the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries sector of all enterprises ranges between 4% and 80%), investment is low, there is a high level of unemployment, and informal employment. Access to finance for small and medium-sized enterprises and smaller farmers can be challenging. In rural areas, transportation is underdeveloped, and the transport infrastructure is outdated and in need of improvement, making access to healthcare, education, and social services challenging. The primary challenges facing rural development include low incomes, increased migration due to a lack of suitable career opportunities for young people, limited administrative capacity at the local level, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and difficulties in effectively absorbing EU funds.

According to data extracted from the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL) for Bulgaria, retail sales of organic products have grown significantly, from €7 million in 2014 to €37.77 million in 2023. The increase for the period is 5.4 times, with an average annual increase of €3.419 million and an average annual growth rate of 20.6%. The empirical value of the first-order autocorrelation coefficient (0.91155) at a significance level of 0.05 is greater than the correct limit of the theoretical values of the first-order autocorrelation coefficient, ranging from −0.564 to +0.360, which means that the studied time series contains a trend.

The clear, steady trend toward higher sales of organic products in Bulgaria indicates significant potential for organic production to expand, as people increasingly embrace healthy, eco-friendly products. Distribution is improving, allowing them to reach the end consumer more quickly and easily, not only through farmers’ markets and specialized organic shops but also through supermarkets and retail chains with dedicated organic food sections. Over the years, organic products produced in Bulgaria have established their quality and are well accepted on the European market. Increasing exports of organic products is a potent stimulus for increasing organic production.

Although the production and market for organic products in our country have not yet reached their full potential and are still developing, the fact that most organic producers are also exporters and importers could positively impact the sector’s development. The market for organic products will continue to develop as consumers become increasingly convinced of the benefits of organic products, thanks to the control and certification system in place, as well as information and awareness-raising activities highlighting their advantages, which will increase the share of organic farming.

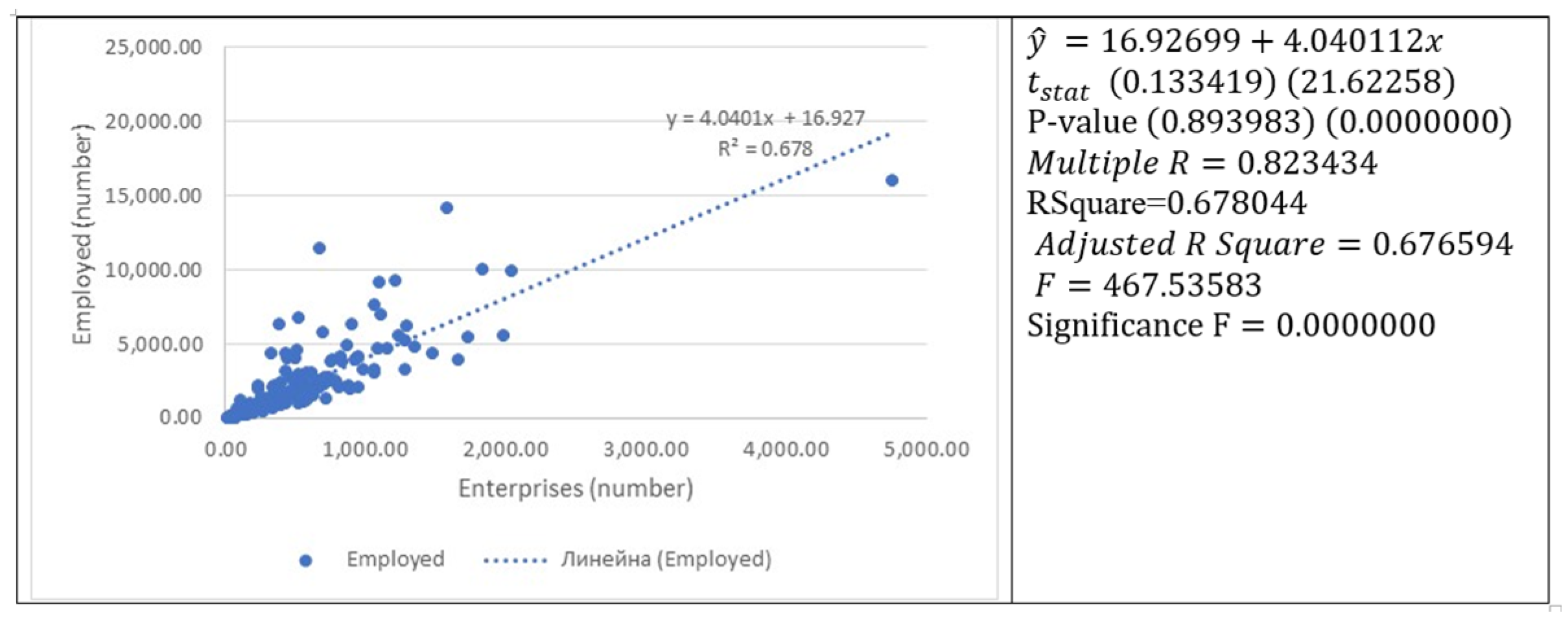

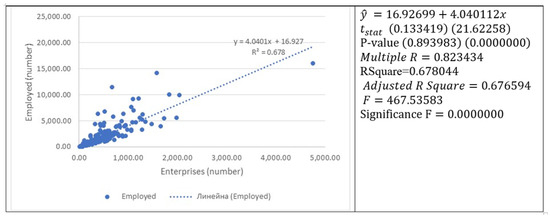

An analysis of the relationship between the number of enterprises and the number of people employed in municipalities with populations of up to 30,000 shows a strong positive correlation (r = 0.823434). The linear regression model was adequate (F > Significance F). The regression coefficient β was statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) and indicates that the number of employed persons increases by 0.167828 with each additional enterprise (Figure 4). The coefficient of determination indicates that 67.8% of the variation in the number of employed persons is explained by variation in the number of enterprises, and 32.2% by other factors not included in the model.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of the dependence between the number of enterprises and the number of employees in municipalities with a population of up to 30,000 people. Source: National Statistical Institute and the Author’s calculations.

The analysis is expanded to include a study of the correlation among indicators specific to agriculture: the number of enterprises, the number of employees, and net sales revenue. For this purpose, single-factor regression models of the relationships were constructed: the number of enterprises and the number of persons employed in agriculture, the number of enterprises and net sales revenue in agriculture, and the number of persons employed and net sales revenue in agriculture.

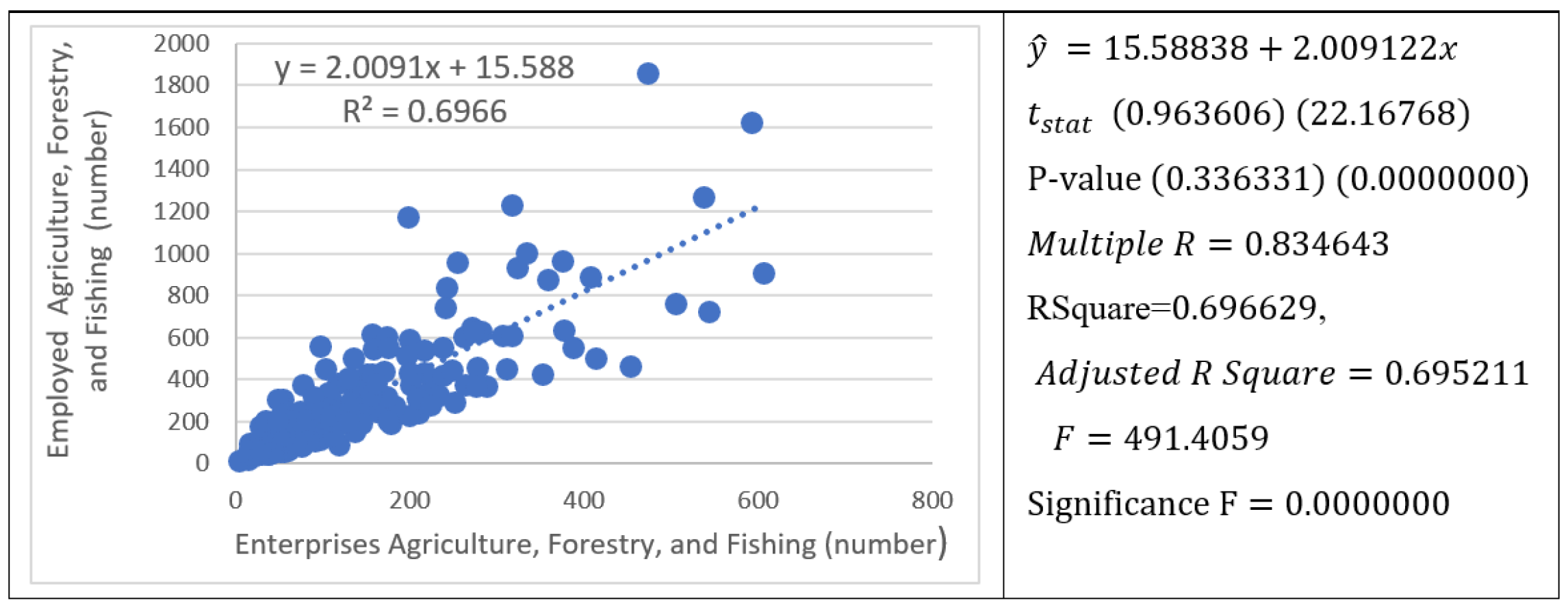

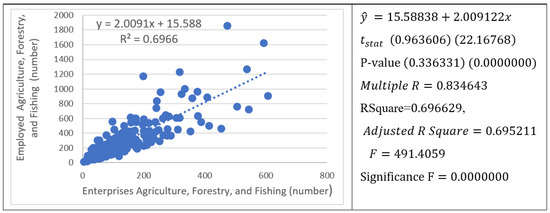

The analysis of the dependence between the number of enterprises and the number of persons employed in agriculture for municipalities with a population of up to 30,000 revealed a strong positive correlation (r = 0.834643). The linear regression model is adequate (F > Significance F), and the regression coefficient β is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). The coefficient of determination gives grounds for concluding that 69.66% of the variation in the number of persons employed in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector is caused by the variation in the number of enterprises in this sector, and 30.34% of the variation in the number of employed persons in the industry is attributed to factors not included in the model. The regression coefficient shows that the number of persons employed in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector increases by 2.0091 when the number of enterprises in the sector increases by 1 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Characteristics of the dependence between the number of enterprises and the number of employees in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector in municipalities with a population of up to 30,000 people. Source: National Statistical Institute and the Author’s calculations.

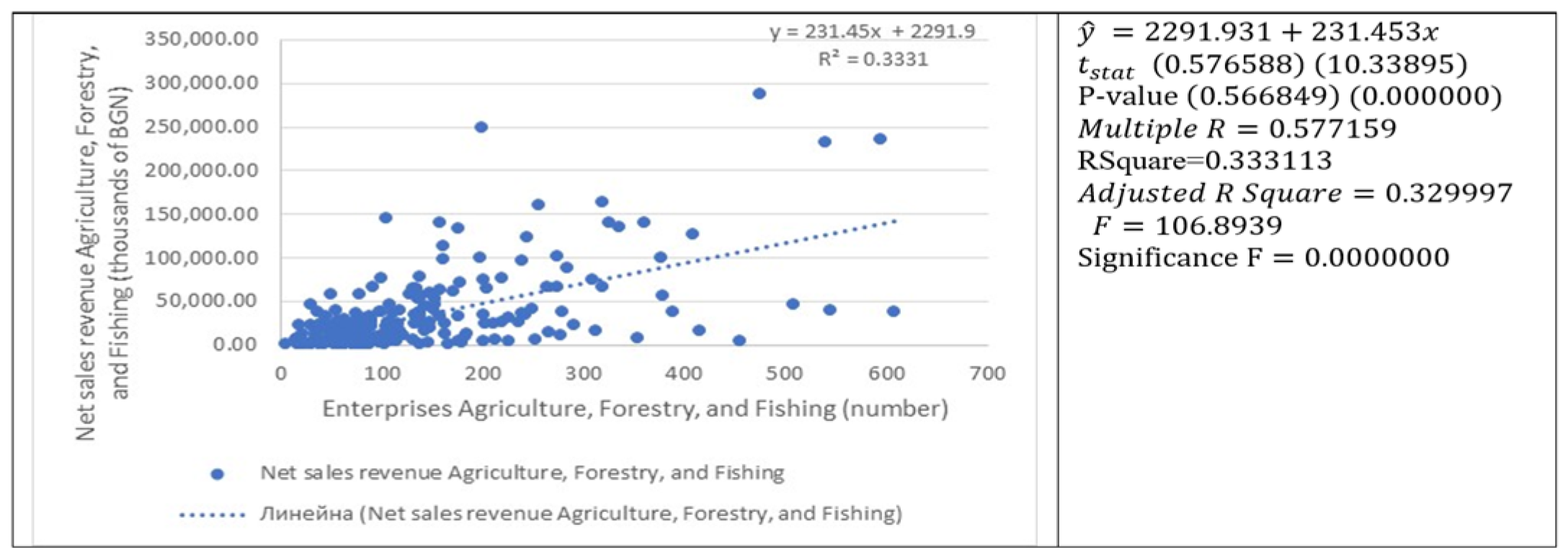

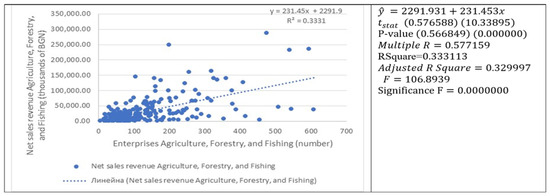

An essential aspect of the analysis, which reveals the potential for the development of organic farming and, consequently, organic food production, is the study of the relationship between the number of enterprises in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector and their net sales revenue. The analysis indicates a significant correlation between the studied indicators (r = 0.577159). The linear regression model obtained is adequate (Figure 6). The value of the coefficient of determination indicates that only 33.31% of the variation in net sales revenue in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector is attributed to the variation in the number of enterprises in this sector, and 66.69% of the variation in net sales revenue in the sector is attributed to factors not included in the model. The regression coefficient β is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05) and indicates that net sales revenue in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector increases by BGN 231.45 thousand when the number of enterprises in the sector increases by one. This is where the great potential for organic farming lies: organic products typically command higher prices, which can lead to better incomes for producers. Furthermore, the long-term development of organic agriculture ensures greater sustainability. Specifically, investment in establishing organic production reduces certain costs over time, such as those for artificial fertilizers and plant protection chemicals, while also directly impacting rural development.

Figure 6.

Characteristics of the dependence between the number of enterprises and the Net sales revenue in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector in municipalities with a population of up to 30,000 people. Source: National Statistical Institute and the Author’s calculations.

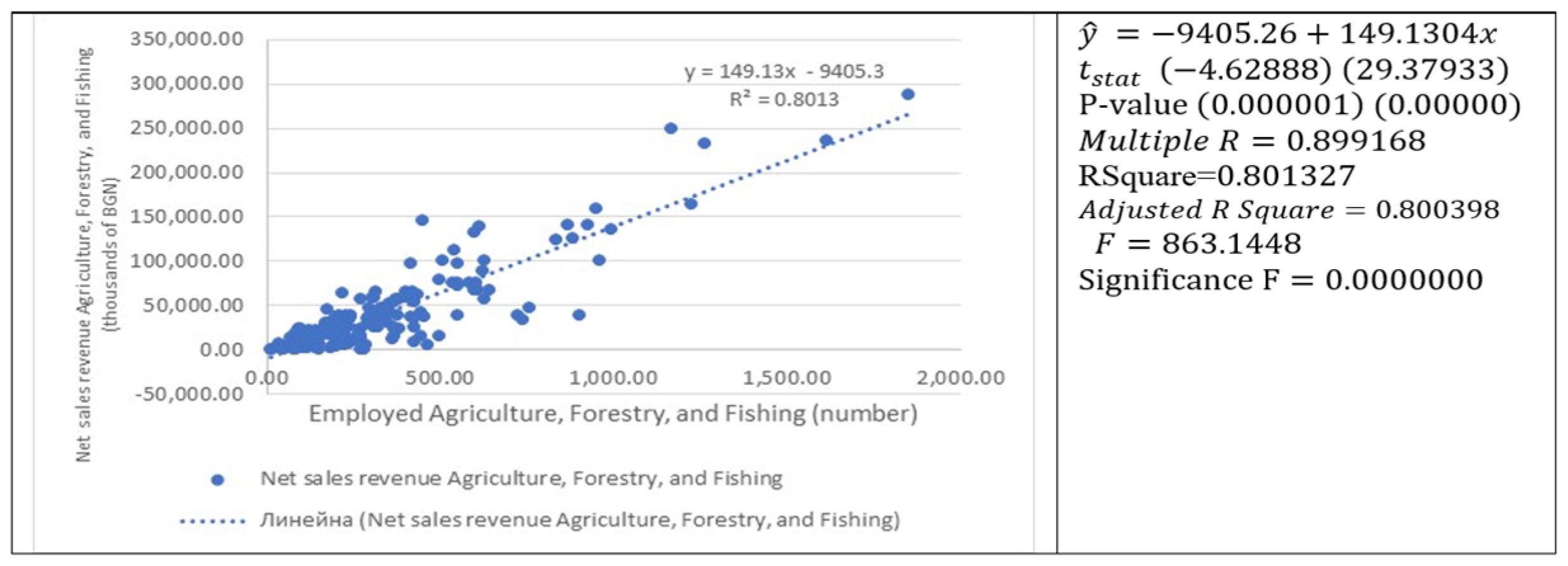

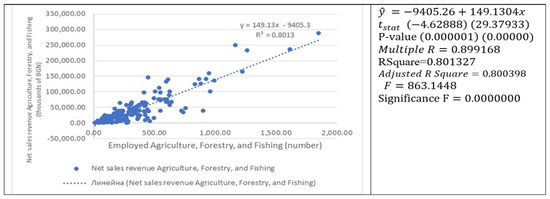

The study examining the relationship between the number of people employed in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector in rural municipalities and net sales revenue in the sector reveals a strong positive correlation, with a correlation coefficient of r = 0.899168. The linear regression model obtained is adequate. The coefficient of determination indicates that 80.13% of the variation in net sales revenue in the agricultural sector is attributed to the variation in the number of people employed in the sector, and 19.87% of the variation in net sales revenue in the sector is attributed to factors not included in the model. The regression coefficient is statistically significant and shows that net sales revenue in the agricultural sector increases by BGN 149.1304 thousand when the number of employees in the sector increases by 1 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Characteristics of the dependence between the number of employees and the Net sales revenue in the “Agriculture, Forestry, and Fishing” sector in municipalities with a population of up to 30,000 people. Source: National Statistical Institute and the Author’s calculations.

Based on the models described above, a multiple linear regression model was developed to characterize the relationship between the number of enterprises (), the number of employees (), and net sales revenue in the agriculture, forestry, and fishing sector (), in municipalities with a population of up to 30,000. The multiple linear regression model is adequate ( and the regression coefficients and are statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). The multiple correlation coefficient of 0.946876 indicates a strong joint influence of the number of enterprises and the number of employees in agriculture on the unexamined factors affecting net sales revenue in the sector. The coefficient of determination shows that 89.66% of the variation in net sales revenue in agriculture is driven by the variation in the factors under study, and only 10.4% of the variation is driven by other factors not included in the model.

p-value (0.430945) (0.000000) (0.000000)

The results clearly show that to increase organic production and net sales revenue, it is more important to expand the number of people employed in existing enterprises within the “Agriculture, forestry, and fishing” sector by registering them as organic producers. It is well known that organic production has its specific characteristics—it requires more labor, as herbicides are not used, and some activities are carried out manually or mechanically. In some crops, manual labor is difficult to replace. Labor costs are higher in organic production, but the added value of the organic output is significantly higher, which has a positive impact on rural areas. As mentioned above, the share of enterprises in the “Agriculture, forestry, and fishing” sector is between 4% and 80%, which clearly shows that the expansion of organic production in rural areas is an opportunity for their development, for increasing entrepreneurial activity, for improving the local economy, employment, income, and living conditions, and for reducing migration to larger cities and the capital. For enterprises already registered as organic operators, it is necessary to expand the area under organic crops, increase the number of organically reared animals, and increase organic food production, thereby stimulating economic activity in rural areas.

In different regions of the country, organic production is developed to varying degrees, with the South Central, Southwest, and Southeast regions being more advanced. Despite good ground conditions, development is less prevalent in the Northwest, Northeast, and North Central regions. This conclusion is confirmed by the regional structure of registered organic operators in Bulgaria—their relative share by statistical region is as follows: 8.8% for the North-Western, 17.9% for the North-Central, 16.9% for the North-Eastern, 18.5% for the South-Eastern, 17.5% for the South-Western, and 20.6% for the South-Central regions. The majority of organic production is concentrated in small settlements with suitable climatic and soil conditions for organic farming, which often face various difficulties, including a lack of skilled workers, poor transport infrastructure, challenges in establishing links with suppliers and customers, insufficient investment funds, poorly developed marketing, and others. At the same time, the development of organic production in rural areas creates conditions to attract young people to farming, generate new jobs, and establish recognizable brands for local organic products. These products can serve as the basis for themed festivals and fairs, attracting tourists for tastings and visits to organic farms and other attractions.

The production of organic products and food stands out as key to the sustainable development and management of rural areas, as it occupies an essential place in the Common Agricultural Policy, the Organic Production Development Plan, and the Rural Development Program. The development of organic food and other product production has the potential to become a significant part of the local economy, increasing employment, income, and quality of life, and reducing migration in rural areas.

As a result of the analysis, it can be summarized that rural development in Bulgaria requires a systematic and comprehensive approach that combines economic support, social policies, infrastructural renewal, and innovation [94]. Increasing the scale of organic farming in rural areas will significantly help make them vibrant, sustainable, and attractive places to live and work. Such an objective is achievable through improved absorption of EU programmes, the mobilisation of internal potential, and the activation of local community participation through the implementation of integrated regional development strategies, the introduction of successful business practices, and other measures [95].

5.2. Evaluation of the Relation Between the Bulgarian Organic Food Market and the Development of Rural Areas Development

The production of organic products and foods can contribute significantly to the development of rural communities in Bulgaria. These products create high added value, require minimal investment, and generate jobs. They have the potential to increase their market share, driven by growing domestic demand and strong international demand. In addition, they preserve natural resources and are a prerequisite for the development of sustainable rural tourism and other sustainable activities.

Based on the results of the Super Matrix and in accordance with the methodological instructions, which state that higher scores mean greater importance, an overall assessment of the SWOT matrix is presented below (Appendix A, Table A4). The analysis accounts for cumulative scores by row and column, highlighting the most critical internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as the most influential external opportunities and threats.

- Strengths assessment. The strengths with the highest overall scores, indicating their strategic importance, are:

- Growing demand for healthy foods and environmentally friendly products (total score: 190). This is the most important strength. It highlights the macro trend in consumer behaviour, driving the growth of the organic market. This is a strong pull factor that justifies increased investment and policy focus. This growth in demand is not just a passing trend but a lasting change in consumer behaviour.

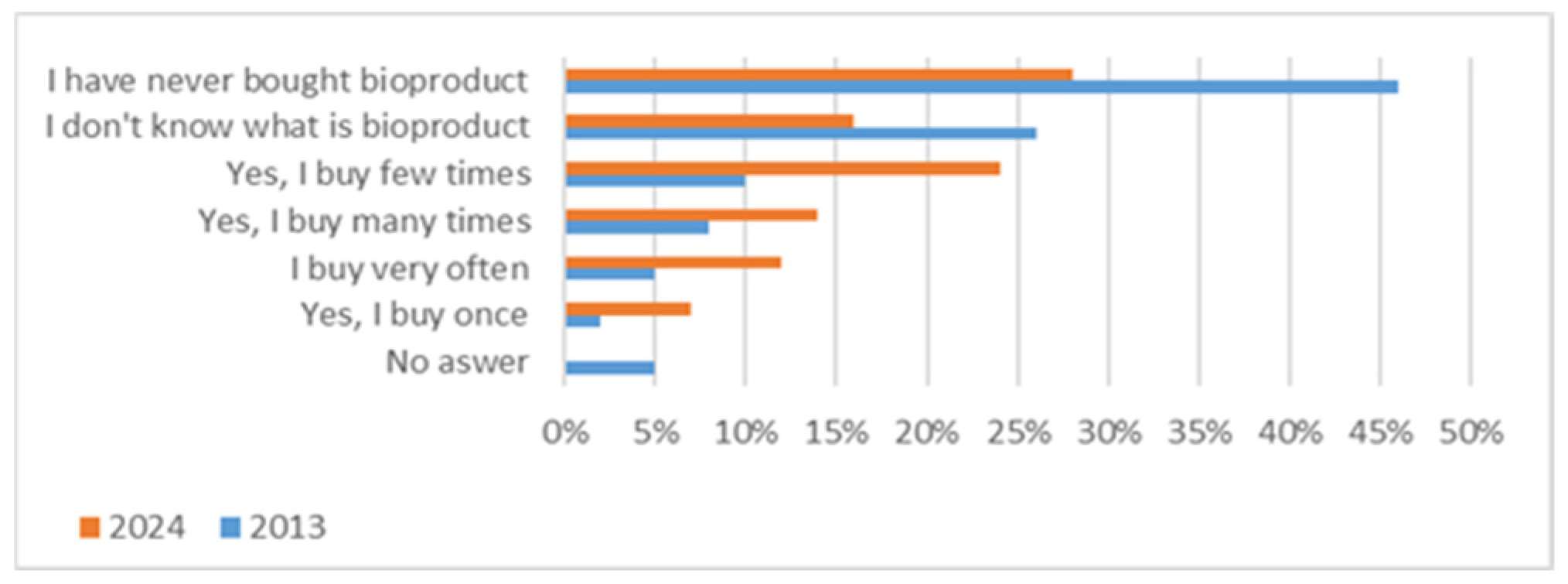

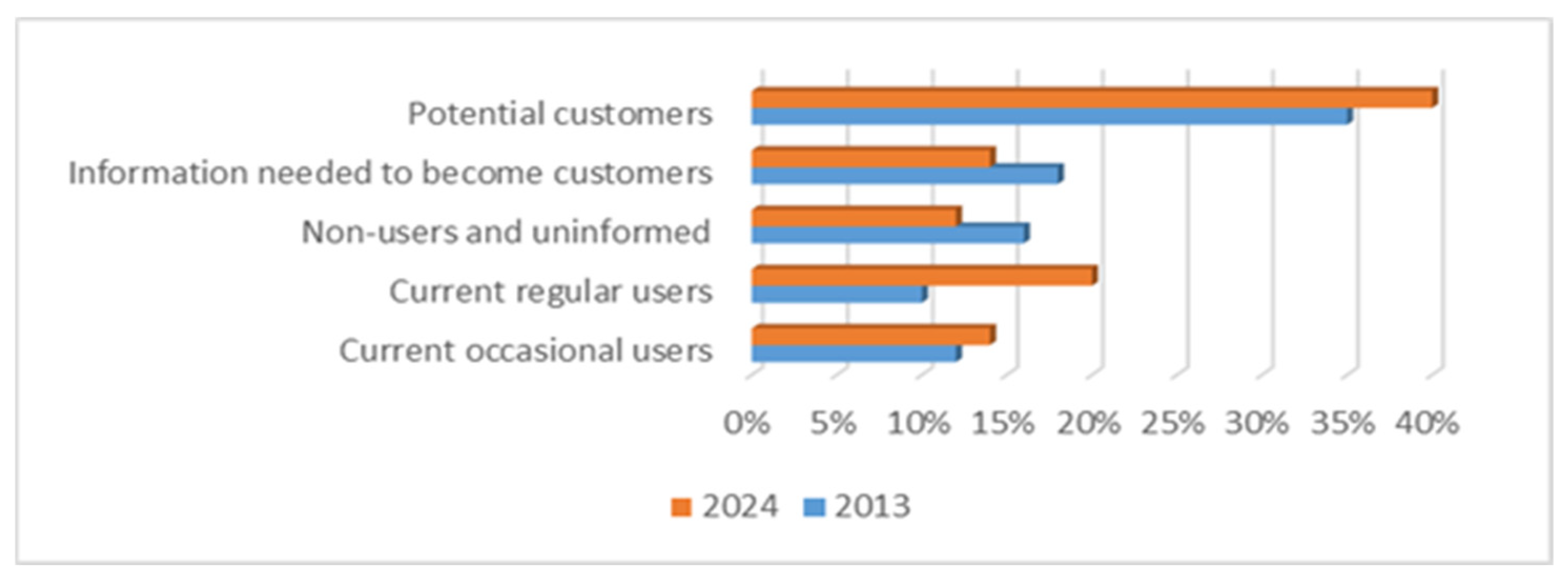

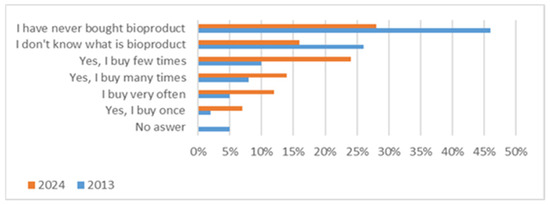

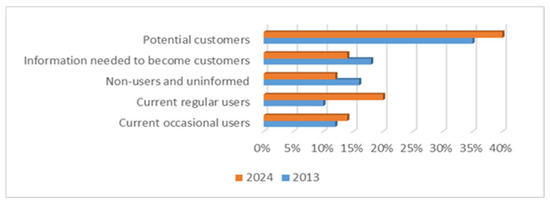

The percentage of consumers actively seeking organic food has increased dramatically from less than 5% in 2013 to just over 20% in 2024. The increased demand for products is also evident in Figure 8. The fact that the proportion of respondents who buy organic products multiple times has increased significantly—from 10% in 2013 to 24% in 2024—indicates a growing consumer interest in organic products. According to the data, demand is increasing overall. This fact provides sufficient grounds to claim that respondents are optimistic about an increase in consumer demand for organic products. The market potential for organic products is also increasing, as shown in Figure 8 (the proportion of respondents who have bought organic products and of those who are aware of their existence and characteristics is increasing).

Figure 8.

Frequency of purchases of organic products. Source. The authors’ research.

Although the country’s consumption and market for organic products are growing steadily, there remains an opportunity and potential for increased demand for such products in the future (Figure 8). This is evident from the large number of potential consumers, who represent the largest group in the population in terms of their willingness to consume organic food.

Increased consumer interest is a decisive factor for the organic sector, encouraging entrepreneurs, farmers, and investors to enter or expand into this market. It also creates a favourable environment for the development of organic value-added supply chains, innovation in sustainable agriculture, and diversification of product offerings. There is a strong link between increased confidence in organic production, increased demand for organic products, and the sector’s competitiveness.

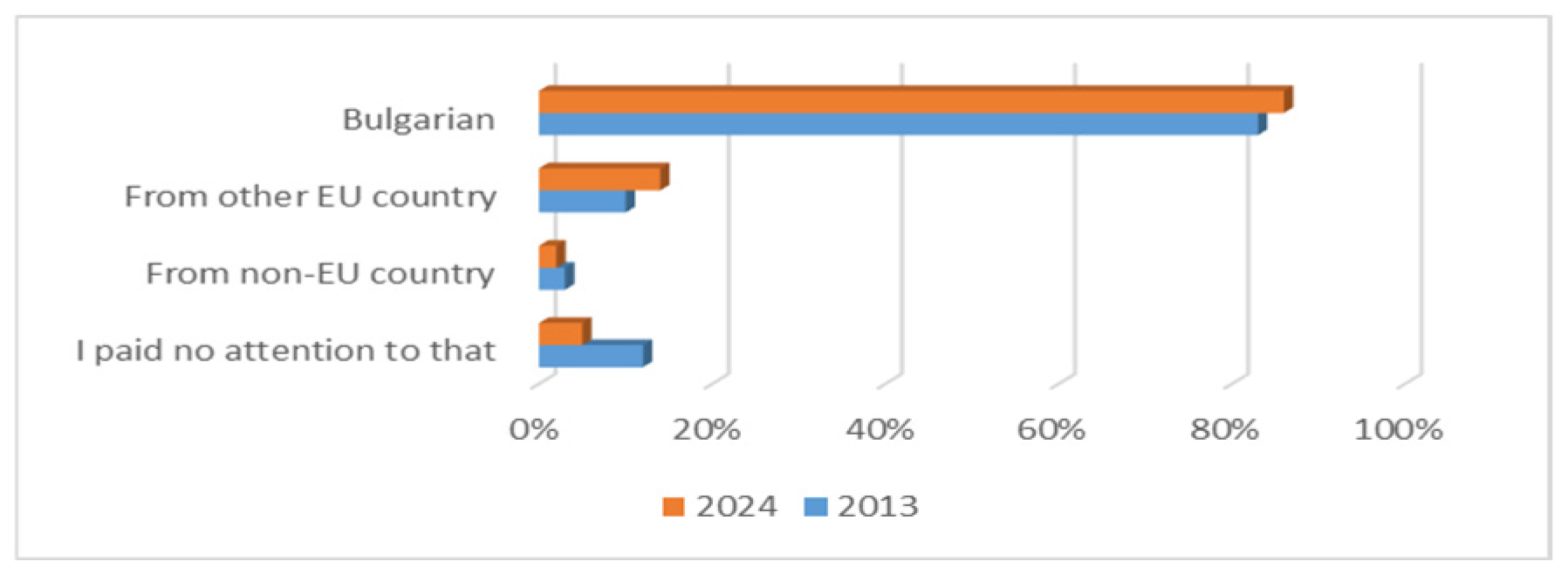

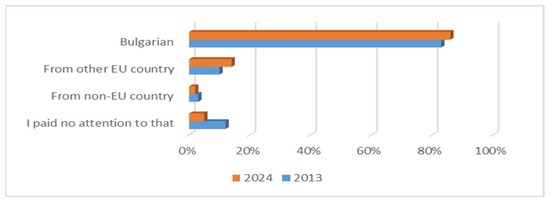

The change in attitudes is linked to an improvement in quality. This is confirmed by the results, which show that product quality is the leading factor for consumers, not origin. Hence, improving the quality of organic products should be a permanent goal for organic producers as competition between Bulgarian and foreign producers becomes increasingly fierce. According to a quarter of the business representatives, Bulgarians still prefer Bulgarian organic products, the main reasons being lower prices, the perception that they are of higher quality than imported products, general confidence in Bulgarian production, and the desire to stimulate and develop organic production in the country (Figure 9). This explains the tendency to offer more Bulgarian organic products than imported ones.

Figure 9.

Distribution of the origin of the last purchased organic product. Source. The authors’ Research.

- Favorable natural and climatic conditions (overall score: 159) and Availability of specific traditional Bulgarian products suitable for organic production (overall score: 143). This highlights Bulgaria’s natural comparative advantage in organic production, which can be leveraged to sustainably expand the sector. Additionally, organic production is a significant force for the entire sector at the national level. The combination of favorable natural and climatic conditions, along with the use of specific traditional products, is a critical structural force driving the development of the organic market in Bulgaria. Rural areas in Bulgaria are characterized by diverse agro-ecological zones, rich soils, and a temperate continental climate, which together support the cultivation of a wide variety of crops without the intensive use of synthetic fertilizers.

- 2.

- Weakness assessment. The most critical weaknesses with high overall scores include:

- Insufficient subsidies for organic production (total score: 212). This is the most significant internal barrier. Lack of adequate subsidies for organic production stands out as the most critical internal weakness. The weakness highlights a structural gap in agricultural policy and financial support mechanisms, particularly in comparison to other EU Member States. This problem is particularly acute in Bulgaria, where the majority of organic farms are small or family-run, often lacking access to capital and risk-mitigation tools. Furthermore, the lack of consistency and transparency in subsidy allocation policies further weakens the sector.

- Insufficient public awareness of organic products (overall score: 201). One of the most critical internal weaknesses identified in the SWOT analysis of the Bulgarian organic market is the low level of public awareness and understanding of organic products. Despite growing global trends towards healthy consumption and environmentally sustainable agricultural practices, a significant portion of the Bulgarian population remains poorly informed about the nature, benefits, and distinguishing characteristics of organic products compared to conventional alternatives.

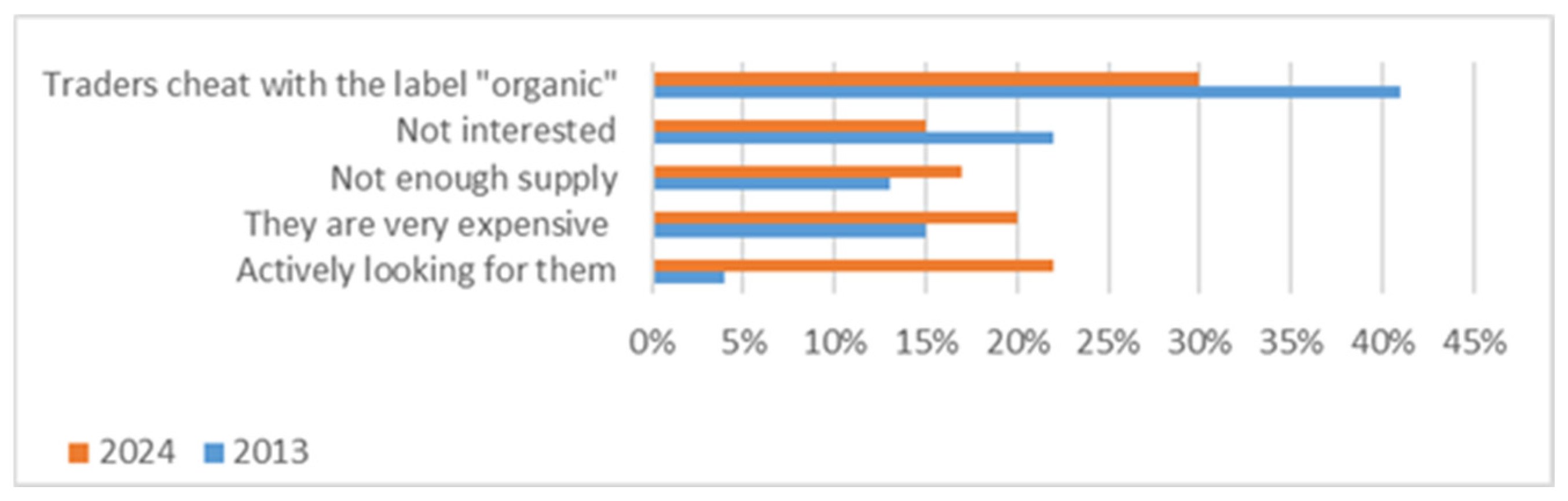

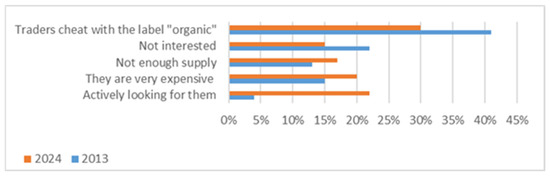

The trend of awareness about organic products is positive. This trend is highlighted by the survey results (Figure 10). As awareness of organic farming increases, so does confidence in the sector. As a result, organic production is on the rise. Competitiveness is directly linked to increased confidence in organic food.

Figure 10.

Consumer attitudes towards organic food. Source. The authors’ Research.

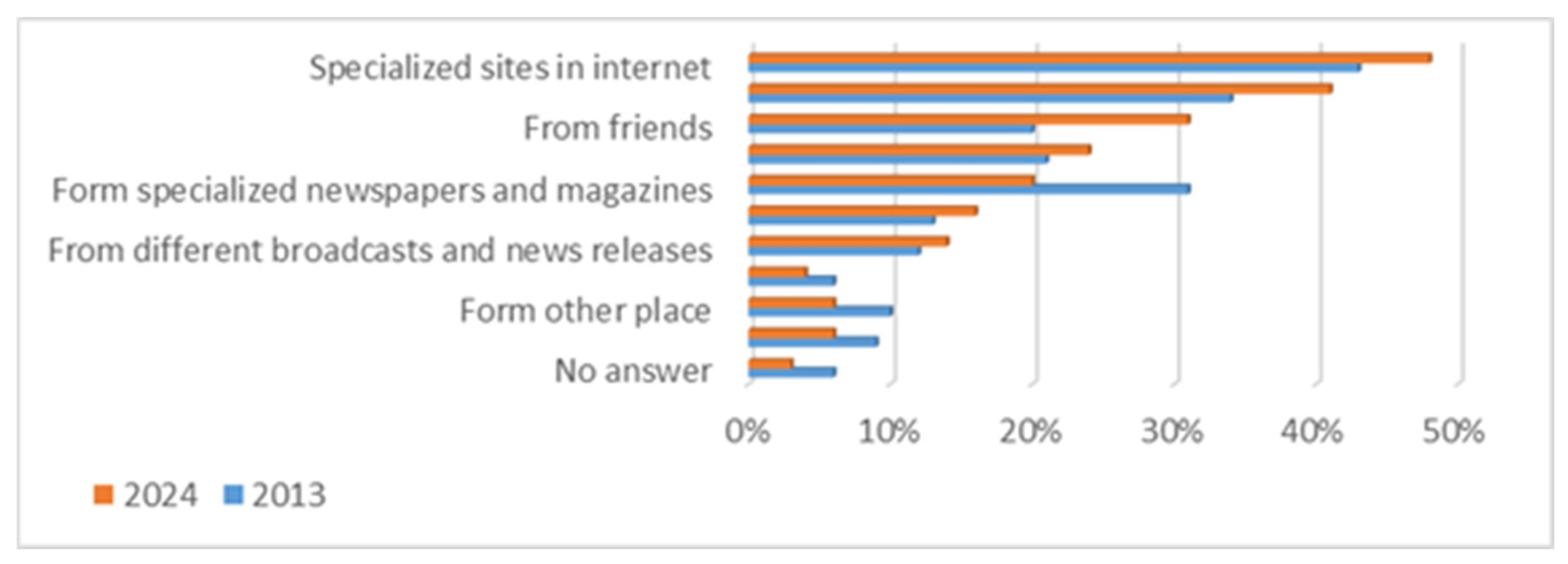

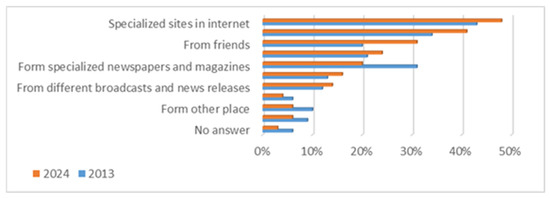

The increased interest in organic food is also closely linked to the current trend towards green living and environmental protection. The proportion of respondents obtaining information from the internet, friends, newspapers, specialised websites, and other sources is increasing, with the total share of sources exceeding 100% as respondents identified more than one source of information (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Primary sources of information on organic products. Source. The authors’ Research.

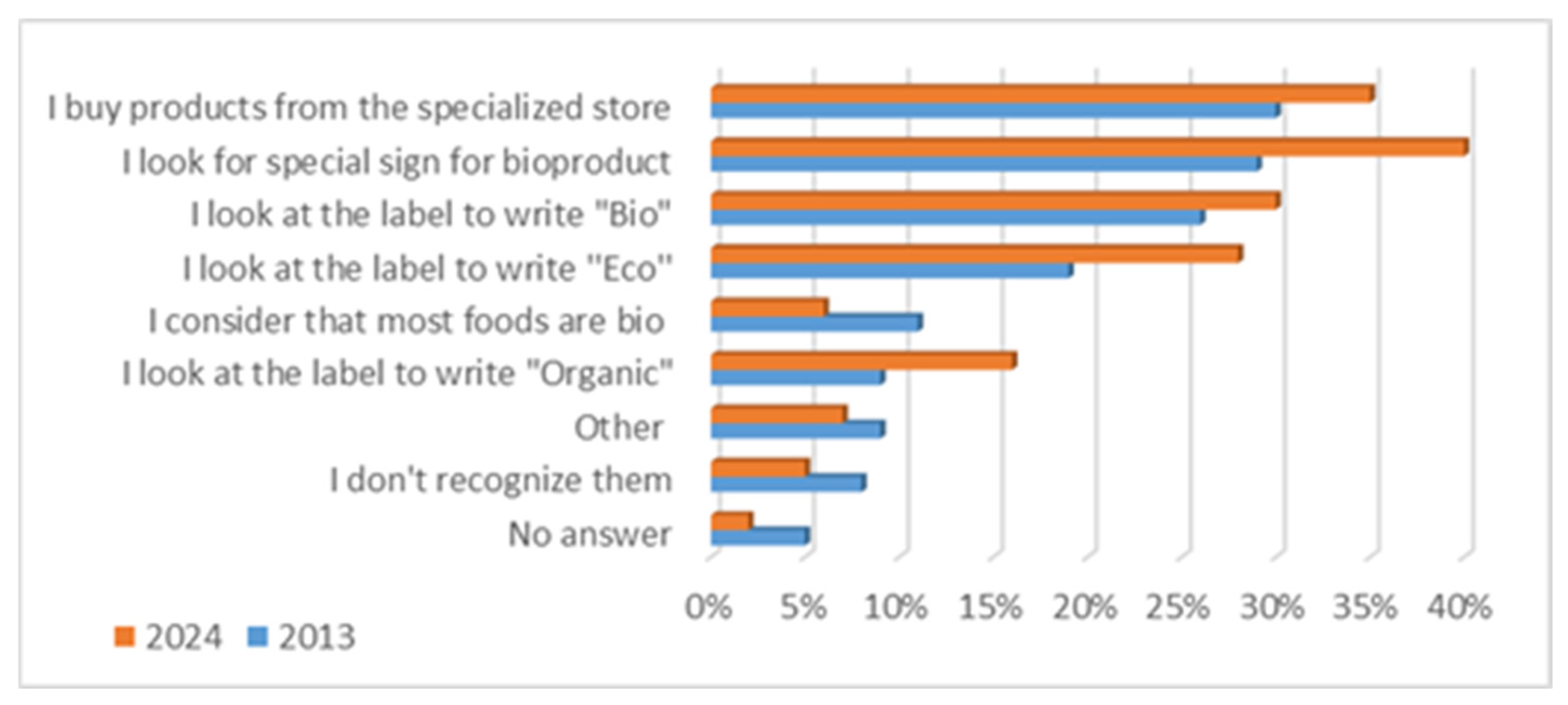

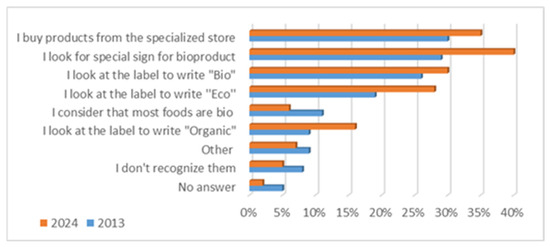

Despite these findings, the level of consumption of organic products in the country remains low, and consumers are generally not sufficiently aware of how to distinguish organic products from other products (Figure 12). The criteria for distinguishing organic products are interrelated with the identification of different categories of consumers based on their awareness (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Categorization of consumers according to their awareness and propensity to consume organic products. Source. The authors’ Research.

Figure 13.

Criteria for distinguishing organic products when shopping, according to consumers. Source: Author’s Research.

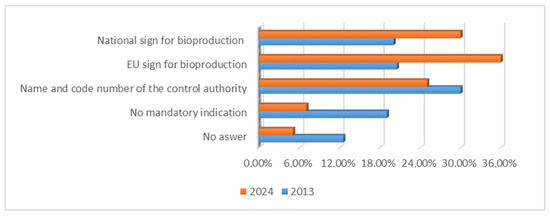

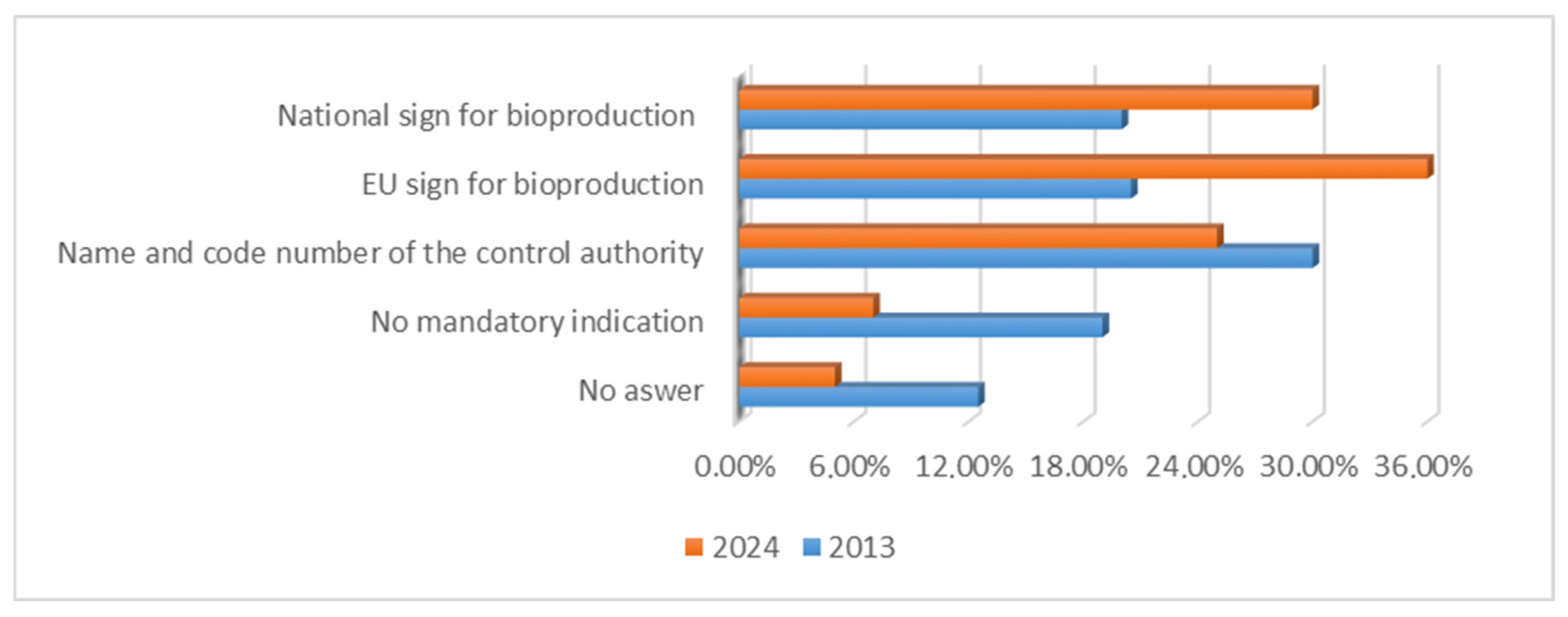

- The presence of fakes and imitations (total score: 147). This is recognised as a very significant internal weakness of the Bulgarian organic market, which is reflected in its overall score of 147 in the SWOT matrix. Despite the identified weakness, the sociological survey shows an opposite trend. Most respondents are aware that organic products should have a label on their packaging that guarantees their organic status (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

A label guaranteeing that the product is organic, as perceived by consumers. Source. The authors’ Research.

Figure 14.

A label guaranteeing that the product is organic, as perceived by consumers. Source. The authors’ Research.

They are correctly informed that this should be the name and code number of the control body that controls and certifies the product. This problem not only threatens consumer confidence in the authenticity of organic labelling but also creates distortions in the competitive environment, placing genuine producers at a significant disadvantage.

- 3.

- Opportunity assessment. Based on the overall assessment, the most attractive and significant opportunities are:

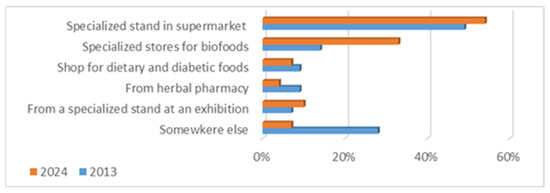

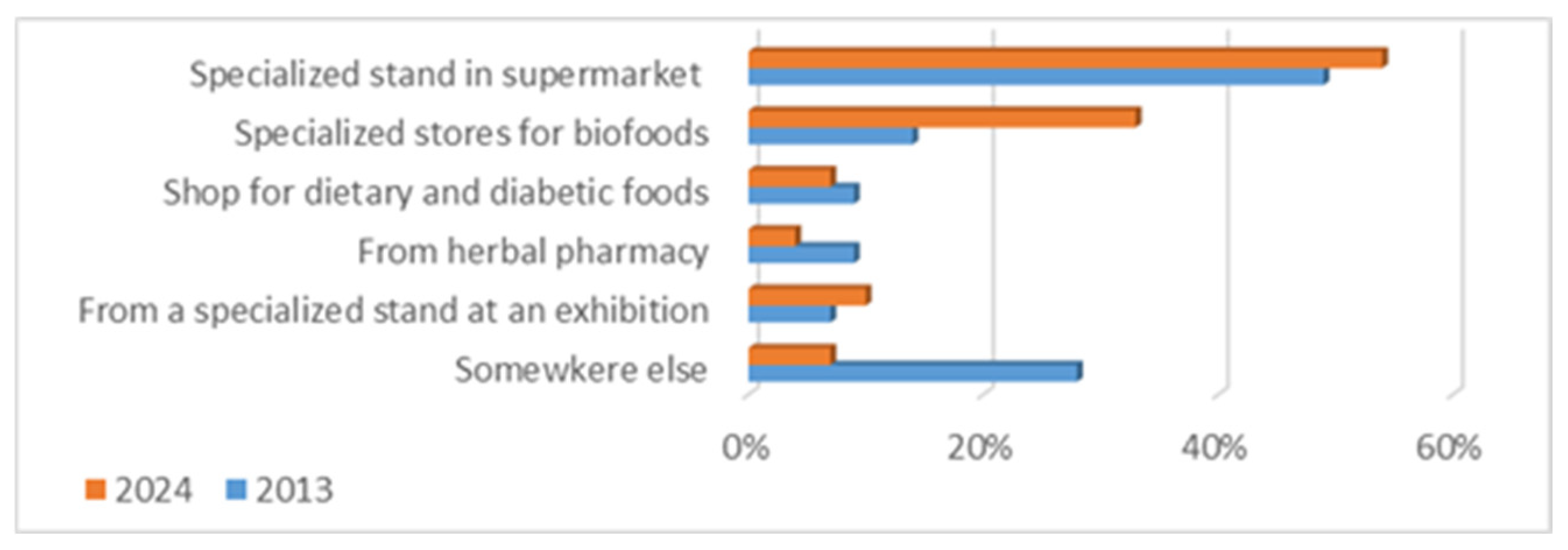

- Expanding the range of products available in the retail chain (score 289) and offering organic products in other types of outlets (score 229). The results of the survey show that organic products are most widely available in supermarket and hypermarket chains and are typically found on dedicated stands (Figure 15). The increase in the percentage of organic products purchased from specialised organic shops is striking, as these outlets offer a wider range and variety of products (13% in 2013; 32% in 2024).

Figure 15.

Preferred places to buy organic products. Source: Author’s research.

Figure 15.

Preferred places to buy organic products. Source: Author’s research.

Despite the results shown, the Bulgarian organic market is currently characterised by limited product diversity and low penetration in the main distribution channels. The range of organic products available in supermarkets, grocery stores, and specialty shops is relatively narrow, often limited to a few main categories such as dairy products, cereals, and selected fruits and vegetables. On the other hand, increasing the range is linked to diversification and stimulating supply in different outlets. This reflects the need to overcome the limited availability of organic products in specialty stores or niche markets and instead integrate them more widely into mainstream outlets (Figure 15).

- Increase organic production to diversify supply. With an overall score of 260 points, increasing organic production to diversify market supply is a strategic lever to strengthen the Bulgarian organic sector. This opportunity is supported by broader macro trends in consumer behavior, particularly the growing preference for organic, health-oriented, and environmentally sustainable products.

- 4.

- Threat assessment. The most serious external threats, according to their overall assessment, are:

- Decline in consumption due to high product prices (208), insufficient popularity of organic products (108), and decline in production due to inadequate subsidies (128). Consumption dynamics are highly dependent on both prices and insufficient popularity, as demonstrated by the results in the period 2013–2014. Demand constraints risk hampering the expansion and sustainability of the organic sector in Bulgaria. This result highlights a critical structural barrier that affects both current consumption patterns and the potential for market expansion. The two factors strongly influencing demand and consumption threaten the sector’s potential growth in Bulgaria, which will inevitably affect rural dynamics. The higher price is explained by both the specificity of the products and the more limited supply, usually caused by insufficient subsidies. This highlights the need for targeted policy interventions, supply chain optimisation, consumer awareness strategies, and public policy.

In summary, the survey results presented indicate a sustained trend of increasing awareness of organic farming, with a direct impact on lasting positive change in attitudes towards organic products. As a result of these processes, the demand for organic products is increasing and their production is growing. This, in turn, stimulates the development of rural areas. The results of interviews with experts, along with the arrangement of the answers in the SWOT matrix, also confirm these processes and trends.

6. Discussion

Based on the analysis, it has been shown that the impact of organic farming on rural development is complex, encompassing economic, demographic, social, and environmental factors. The economic impact of developing organic production is reflected in the creation of jobs, the attraction of financial resources under the Organic Production Development Plan and the Rural Development Program, and increased entrepreneurial activity in local communities. It also includes developing other activities such as rural tourism, organizing tastings, and regional product festivals. Expanding organic production in rural areas creates conditions to reduce migration to larger cities and the capital, as well as to retain young people in smaller settlements. In social terms, the development of organic food production has a profound impact, promoting further education, sustainable practices, and social cohesion, while also reviving traditional methods of growing and producing local products that are almost extinct in industrial agriculture. Ecologically, the impact of organic production on rural areas is undeniable. It contributes to the preservation of soil, water, biodiversity, and the rural landscape, making these regions more attractive for living and tourism. The advantages of organic farming and its impact on rural areas, as mentioned above, are supported primarily by empirical analysis. The main demographic and economic indicators examined are less favorable for rural municipalities, with the “agriculture, forestry, and fishing” sector accounting for a significant share of the local economy in most of them. The correlation analyses show a strong correlation between the number of enterprises and the number of people employed in the sector, as well as between the number of people employed and net sales revenue in the sector. It is known that organic production employs more people, which increases labor costs but reduces the costs of chemicals and other inputs. It also has greater added value: the products produced are priced higher, and their development can stimulate the local economy. This is why we believe there are sufficient grounds to argue that there is untapped potential for developing rural areas by increasing the share of organic farming in them.

The results of the multiple correlation show that, to increase organic production and net sales revenue, it is more important to increase the number of employees in existing enterprises in the agriculture, forestry, and fisheries sector by registering them as organic producers. From the analysis of indicators at the level of administrative-territorial regions in Bulgaria (NUTS 3), the correlation between the number of registered organic operators and the number of employed in the “Agriculture, forestry and fisheries” sector is significant (r = 0.5293) and moderate between the number of registered organic operators and the gross value added in the “Agriculture, forestry and fisheries” sector (r = 0.3765). The number of organic operators affects employment in agriculture, as some activities in organic production are manual or mechanical and cannot be automated, thereby increasing labour costs. However, since organic production commands a higher price, the value added is higher as well. All this gives us ample reason to believe that expanding organic production will have a positive impact on rural development.

The production of organic food in Bulgaria is stimulated not only by increased government funding but also by the growing demand for this type of food. Concerns about health, sustainability, and food quality stimulate consumer demand for organic and organically produced food. Studies show that consumers prefer products with EU quality labels such as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI), which reinforce trust in organic food sources [57]. Most consumers tend to look for a specific identifying or mandatory mark (logo) [57,96,97].

This study’s results indicate a correlation between the growth in organic production and the development of rural areas in Bulgaria. There is a clear trend towards expanding the area used for growing organic food. A similar trend can be observed in Serbia, Poland, Mexico, and Russia, where similar analyses have been conducted to assess the impact of the bio sector on regional development in rural areas [18,62,63,65,68,70,97,98].

As a result of this study, the authors confirm the three hypotheses formulated. Regarding Hypothesis 1, a significant difference was found in the demographic characteristics of populations residing in rural and urban municipalities, which affects their consumption and dynamics across different territorial groups [18,57,65,98]. Differences are also observed in economic indicators, which prove the interrelationship between different groups of municipalities and their demographic characteristics.

Hypothesis 2 is also proven because the demographic structure of the population affects the consumption of organic products in Bulgaria. Similar trends are observed across countries, and a shift in consumer attitudes toward organic products can be identified [64,65,66]. The increased consumption of organic products in urban areas has a significant impact on the development of the rural regions where these products are produced. This trend indicates a shift in consumer attitudes toward organic products, which in turn has a positive impact on the development of rural areas [64,65,66,67,72].

The development of organic farming has a substantial positive impact on the development of rural areas (Hypothesis 3). Despite the growing market that influences rural regions, the relatively high cost of organic and bio food remains a significant barrier. Many rural consumers and producers struggle with affordability and access, underscoring the need for government subsidies and policy interventions to increase the availability of organic food [57,91]. The promotion of organic production could be carried out in cooperation with other state institutions, such as the Ministry of Environment and Water, as organic production is an environmentally friendly agricultural activity [63,68]. Financial instability and limited access to capital hinder the growth of organic enterprises. These challenges underscore the need for supportive policies and infrastructure to sustain the development of the organic sector [49,99,100,101].

An opportunity to extend and build on the analysis carried out on the correlation between the expansion of organic food production and rural development is the study of the spatial distribution of organic production, since for many countries a correlation between the spatial distribution of organic farming and socio-economic and environmental factors has been demonstrated [60].

7. Conclusions

Based on the original methodology applied, which combined an interdisciplinary approach with statistical methods, sociological research, and SWOT analysis, the main objective of this study—namely, to analyze and assess the impact of organic production on rural development and to formulate recommendations for the implementation of targeted policies and measures—was largely achieved. The authors address the main research question: Is there a strong link between the increase in organic production and the development of rural areas, and to what extent has this sector intensified positive socio-economic development processes over the last 10 years? In conducting this study, the authors obtained interesting and significant results that fill gaps in both the Bulgarian and global scientific literature.