Comparative Analysis of Battery and Thermal Energy Storage for Residential Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems in Building Electrification

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Building Energy Transition and the “Duck Curve” Problem

1.1.2. Thermal Energy Storage for Grid-Responsive Heating and Cooling

1.1.3. Model Predictive Control for HVAC Operation

1.1.4. Comparative Storage Studies: BESS vs. TES

1.2. Research Gap, Objectives and Contribution of This Study

2. Methodology

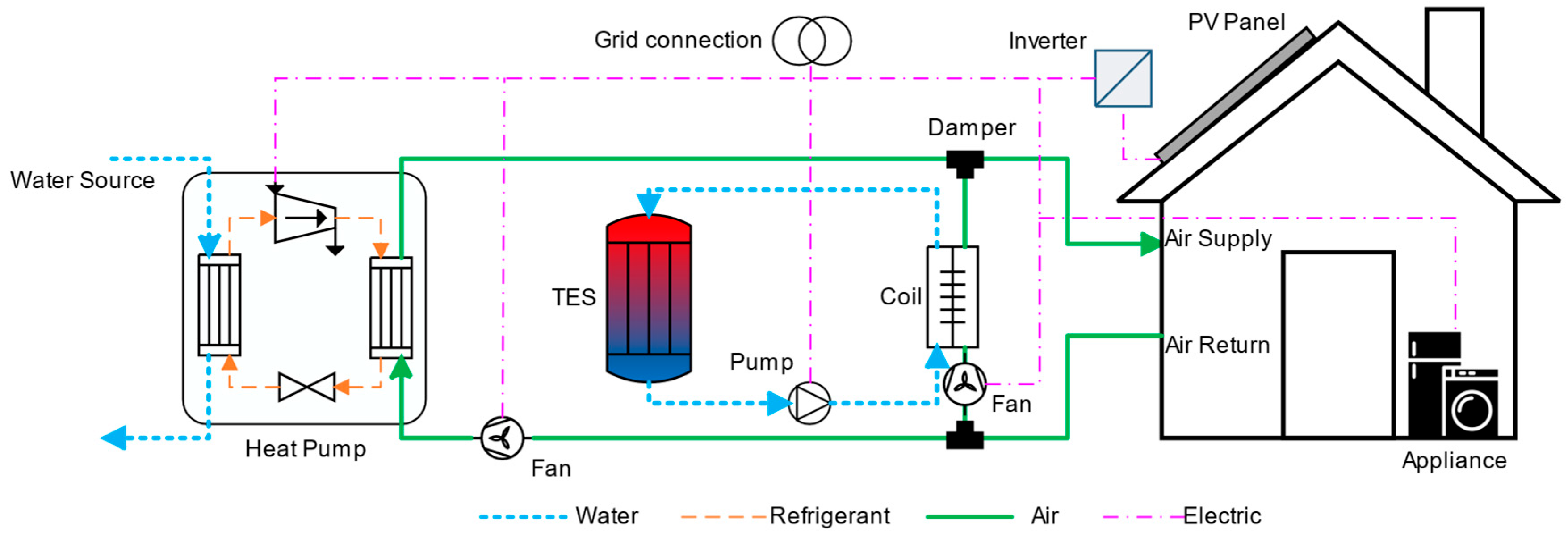

2.1. Overview of System Configurations

2.2. MPC Centered Optimization Framework

- For the TES system, constraints include the thermal storage capacity, the latent energy state (i.e., liquid fraction), and charging/discharging heat transfer rates.

- For the BESS system, constraints include the battery’s state-of-charge (SOC) limits, maximum charging/discharging power, and round-trip efficiency.

- Storage Dynamics: Instead of tracking the thermal storage’s liquid fraction, the key state variable is the battery’s State of Charge (SOC). Its dynamics are governed by charging (Pch) and discharging (Pdis) power flows and their associated efficiencies (ηch, ηdis).

- Power Balance: Consequently, the electrical power balance is more comprehensive than in the TES system. The battery itself is introduced as both an electrical load (when charging) and a source (when discharging). The constraint must therefore balance all building loads (HP, fan, and uncontrollable loads) against all available sources, including the grid, utilized PV, and power from the discharging battery.

2.3. Components Modeling for Optimization

2.4. Development of Virtual Testbed

2.5. Performance Evaluation Metrics

3. Case Study Setup

3.1. Exogenous Inputs: Building, Weather Conditions and TOU Price

3.2. System Parameters and Conditions

3.3. Baseline Configuration and Control Strategy

4. Simulation Results

5. Discussion and Comparison Across Two Systems

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHRAE | American society of heating, refrigerating and air-conditioning engineers |

| BESS | Battery energy storage systems |

| CAISO | California independent system operator |

| CVRMSE | Coefficient of Variation in the Root Mean Square Error |

| DOE | Department of Energy |

| EIR | Energy input ratio |

| HP | Heat pump |

| HVAC | Heating, ventilation, and air conditioning |

| IECC | International energy conservation code |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

| MIP | Mixed integer programming |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| PCM | Phase change material |

| PH | Prediction horizon |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SOC | State of charge |

| TES | Thermal energy storage |

| TOU | Time of use |

| UDH | Unmet degree hour |

References

- Gao, Y.; Hu, Z.; Matsunami, Y.; Qu, M.; Chen, W.-A.; Liu, M. Optimizing Renewable Energy Systems with Hybrid Action Space Reinforcement Learning: A Case Study on Achieving Net Zero Energy in Japan. Renew. Energy 2025, 256, 124493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones-Albertus, B. Confronting the Duck Curve: How to Address Over-Generation of Solar Energy. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/confronting-duck-curve-how-address-over-generation-solar-energy (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Liu, M.; Ooka, R.; Choi, W.; Ikeda, S. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of Energy Saving Potential of Centralized and Decentralized Pumping Systems. Appl. Energy 2019, 251, 113359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-A.; Lim, J.; Miyata, S.; Akashi, Y. Methodology of Evaluating the Sewage Heat Utilization Potential by Modelling the Urban Sewage State Prediction Model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Guo, M.; Fu, Y.; O’Neill, Z.; Gao, Y. Expert-Guided Imitation Learning for Energy Management: Evaluating GAIL’s Performance in Building Control Applications. Appl. Energy 2024, 372, 123753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alva, G.; Lin, Y.; Fang, G. An Overview of Thermal Energy Storage Systems. Energy 2018, 144, 341–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Tang, R. Development of Grid-Responsive Buildings: Opportunities, Challenges, Capabilities and Applications of HVAC Systems in Non-Residential Buildings in Providing Ancillary Services by Fast Demand Responses to Smart Grids. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afram, A.; Janabi-Sharifi, F. Theory and Applications of HVAC Control Systems—A Review of Model Predictive Control (MPC). Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. As Solar Capacity Grows, Duck Curves Are Getting Deeper in California—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Available online: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=56880 (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Synergy. Everything You Need to Know About the Duck Curve. Available online: https://www.synergy.net.au/Blog/2021/10/Everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-Duck-Curve (accessed on 7 August 2024).

- Ma, Z.; Gifford, J.; Wang, X.; Martinek, J. Electric-Thermal Energy Storage Using Solid Particles as Storage Media. Joule 2023, 7, 843–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Yue, H.; Wang, C. A New Kind of Phase Change Material (PCM) for Energy-Storing Wallboard. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, F.; Sunku Prasad, J.; Muthukumar, P.; Rahman, M.M. Thermochemical Energy Storage System for Cooling and Process Heating Applications: A Review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 229, 113617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteconi, A.; Hewitt, N.J.; Polonara, F. State of the Art of Thermal Storage for Demand-Side Management. Appl. Energy 2012, 93, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkeri, E.; Tynjälä, T.; Nikku, M. Numerical Modeling of Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage Integrated with Heat Pump for Domestic Hot Water Production. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 214, 118819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Oliver Gao, H.; You, F. Model Predictive Control in Phase-Change-Material-Wallboard-Enhanced Building Energy Management Considering Electricity Price Dynamics. Appl. Energy 2022, 326, 120023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawalbeh, M.; Khan, H.A.; Al-Othman, A.; Almomani, F.; Ajith, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Recent Advances in Materials for Thermal Energy Storage Applications. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 18, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, W.; Kramer, G.J.; Sun, Q. Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage: A Techno-Economic Literature Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 139, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drgoňa, J.; Arroyo, J.; Cupeiro Figueroa, I.; Blum, D.; Arendt, K.; Kim, D.; Ollé, E.P.; Oravec, J.; Wetter, M.; Vrabie, D.L.; et al. All You Need to Know about Model Predictive Control for Buildings. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 190–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serale, G.; Fiorentini, M.; Capozzoli, A.; Cooper, P.; Perino, M. Formulation of a Model Predictive Control Algorithm to Enhance the Performance of a Latent Heat Solar Thermal System. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 173, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Shekhar, D.K. State of the Art Review on Model Predictive Control (MPC) in Heating Ventilation and Air-Conditioning (HVAC) Field. Build. Environ. 2021, 200, 107952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlanze, P.; Jiang, Z.; Cai, J.; Shen, B. Model-Based Predictive Control of Multi-Stage Air-Source Heat Pumps Integrated with Phase Change Material-Embedded Ceilings. Appl. Energy 2023, 336, 120796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, M.; Ay, M.; Bergs, T.; Abel, D. Review on Model Predictive Control: An Engineering Perspective. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 1327–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, H. Flexibility Categorization, Sources, Capabilities and Technologies for Energy-Flexible and Grid-Responsive Buildings: State-of-the-Art and Future Perspective. Energy 2021, 219, 119598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebarchievici, C.; Sarbu, I. Performance of an Experimental Ground-Coupled Heat Pump System for Heating, Cooling and Domestic Hot-Water Operation. Renew. Energy 2015, 76, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitali, J.; Dhinakaran, S.; Mohamad, A.A. Energy Storage Systems: A Review. Energy Storage Sav. 2022, 1, 166–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Liu, X.; Zou, B.; Yang, K.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, M.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, W.; Tan, R.; et al. Collaborative Framework of Transformer and LSTM for Enhanced State-of-Charge Estimation in Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy 2025, 322, 135548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, G. Energy Storage on Demand: Thermal Energy Storage Development, Materials, Design, and Integration Challenges. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 46, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Kuang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T. Optimal Sizing and Techno-Economic Analysis of the Hybrid PV-Battery-Cooling Storage System for Commercial Buildings in China. Appl. Energy 2024, 355, 122231. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, B.; Lemort, V.; Cendoya, A. Control Strategy and Techno-Economic Optimization of a Small-Scale Hybrid Energy Storage System: A Reversible HP/ORC-Based Carnot Battery and an Electrical Battery. Energy 2025, 329, 136508. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, W.; Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Fu, Y.; O’Neill, Z. Model-Based Characterization of Heat Pump—Thermal Energy Storage Systems for Grid-Interactive Services. In Proceedings of the ASHRAE Transactions, Atlanta, GA, USA, 4–8 February 2023; Volume 129, pp. 840–848. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Yang, Z.; O’Neill, Z. Design And Optimization Of The Conventional Heat Pump With Thermal Energy Storage For Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings. In Proceedings of the 8th International High Performance Buildings Conference, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 15–18 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wetter, M.; Benne, K.; Tummescheit, H.; Winther, C. Spawn: Coupling Modelica Buildings Library and EnergyPlus to Enable New Energy System and Control Applications. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2024, 17, 274–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneifel, J. Prototype Residential Building Designs for Energy and Sustainability Assessment; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2012.

- Tay, N.H.S.; Bruno, F.; Belusko, M. Experimental Validation of a CFD and an ε-NTU Model for a Large Tube-in-Tank PCM System. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 55, 5931–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawley, D.B.; Lawrie, L.K.; Winkelmann, F.C.; Buhl, W.F.; Huang, Y.J.; Pedersen, C.O.; Strand, R.K.; Liesen, R.J.; Fisher, D.E.; Witte, M.J.; et al. EnergyPlus: Creating a New-Generation Building Energy Simulation Program. Energy Build. 2001, 33, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yang, Z.; Calfa, C.; O’Neill, Z. Development and Validation of a Water-to-Air Heat Pump Model Using Modelica. In Proceedings of the American Modelica Conference 2024, Storrs, CT, USA, 14–16 October 2024; pp. 119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Oliver Gao, H.; You, F. Model Predictive Control for Demand- and Market-Responsive Building Energy Management by Leveraging Active Latent Heat Storage. Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, P.A.; Haghighat, F. Modeling of Phase Change Materials for Applications in Whole Building Simulation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 5355–5362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, R.S.; Lucas, R.G.; Taylor, Z.T. Climate Classification for Building Energy Codes and Standards: Part 2-Zone Definitions, Maps, and Comparisons. Ashrae Trans. 2003, 109, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Georgia Power. Business Rates & Tariffs. Available online: https://www.georgiapower.com/business/billing-and-rates/business-rates.html (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Hendron, R.; Engebrecht, C. Building America House Simulation Protocols (Revised). Report Numbers: NREL/TP-550-49246; DOE/GO-102010-3141; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2010; p. 989422. [Google Scholar]

- Rubitherm Technologies GmbH 2025. Available online: https://www.rubitherm.eu/en/productcategory/organische-pcm-rt (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Leadbetter, J.; Swan, L. Battery Storage System for Residential Electricity Peak Demand Shaving. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mode | Heat Pump Status | Airflow Path | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Cooling | Active | Return air → Heat pump → Supply | Delivers cooling directly from heat pump |

| TES Charging | Active | Return air → Heat pump → Coil | Charges TES by transferring cold energy to TES |

| TES Discharging | Inactive | Return air → Coil → Supply | Provides cooling using stored cold energy in TES |

| Idle | Inactive | Heat pump/pump/fans off | No equipment running; minimizes electricity usage |

| System Key Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Total PCM mass [kg] | 280 |

| PCM TES tank heat storage capacity [kWh] | 18 |

| TES Tank volume [m3] | 0.68 |

| Heat pump nominal cooling capacity [W] | 5000 |

| Speed modulation range [–] | [0.31, 1] |

| Effectiveness of water-air heat exchanger [–] | 0.8 |

| Supply air flow rate [m3/s] | 0.439 |

| Water source flow rate [m3/s] | 0.00039 |

| Water source temperature [°C] | 24 |

| BESS capacity [kWh] | 25 |

| BESS maximum charging/discharging rate [kW] | 5 |

| Charging/discharging efficiency [–] | 0.95 |

| PV total panel area [m2] | 25 |

| PV inverter efficiency [–] | 0.98 |

| PV cell efficiency [–] | 0.2 |

| PV active fraction [–] | 0.95 |

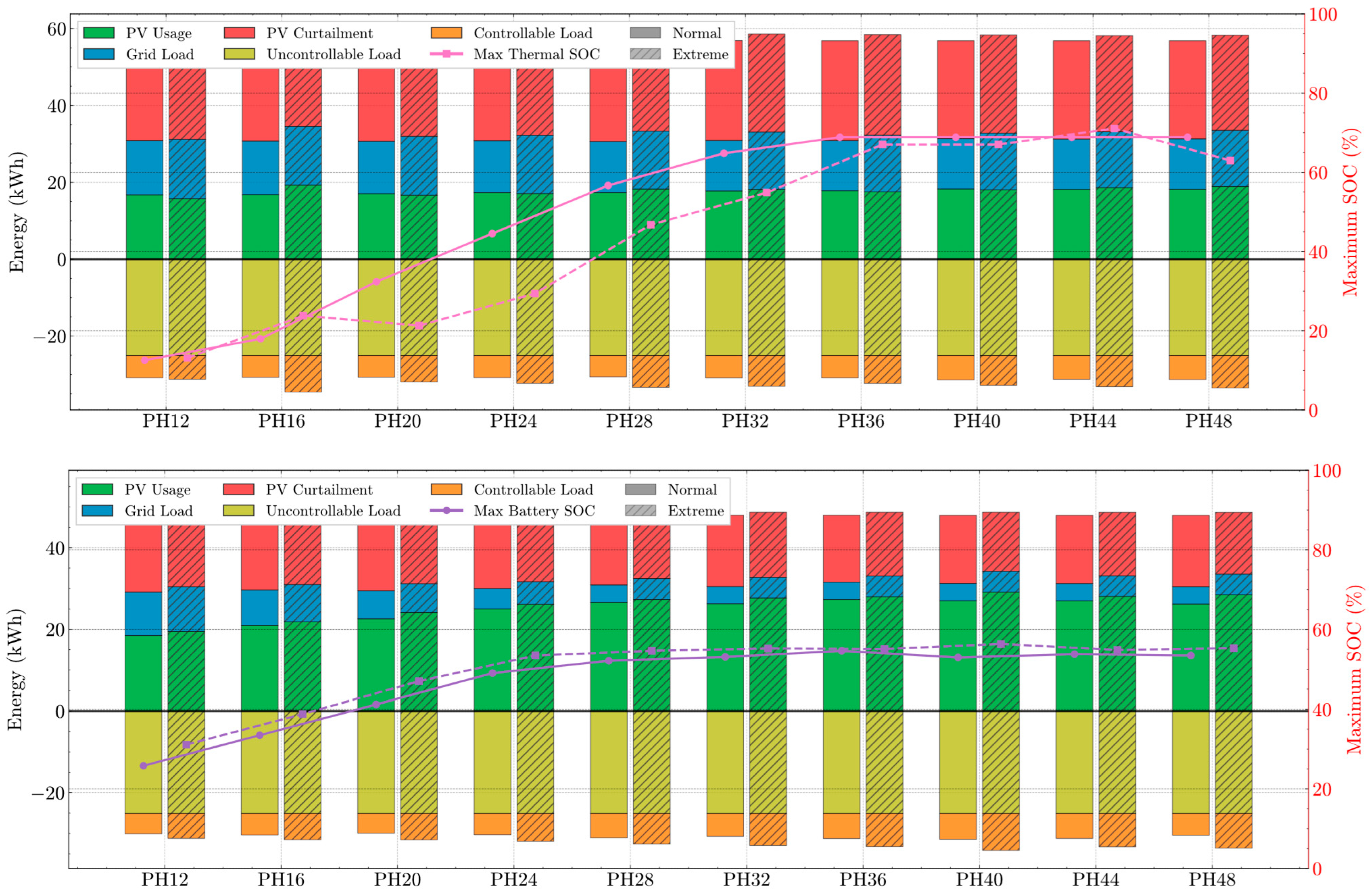

| Grid Import [kWh] | Operation Cost [$] | PV Self-Consumption [%] | Peak Energy Usage [kWh] | Thermal Discomfort [Kh] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV-HP-TES | PH12 | 14.127 | 1.025 | 38.243 | 0.621 | 1.331 |

| PH16 | 13.956 | 1.052 | 38.416 | 0.722 | 0.53 | |

| PH20 | 13.667 | 0.997 | 38.978 | 0.621 | 0.685 | |

| PH24 | 13.497 | 0.981 | 39.6 | 0.621 | 0.758 | |

| PH28 | 13.32 | 0.971 | 39.552 | 0.63 | 0.709 | |

| PH32 | 13.155 | 0.956 | 40.597 | 0.621 | 0.697 | |

| PH36 | 13.103 | 0.955 | 40.683 | 0.621 | 0.599 | |

| PH40 | 13.103 | 0.955 | 41.797 | 0.621 | 0.598 | |

| PH44 | 13.103 | 0.955 | 41.509 | 0.621 | 0.599 | |

| PH48 | 13.103 | 0.955 | 41.642 | 0.621 | 0.681 | |

| PV-HP-BESS | PH12 | 10.675 | 0.651 | 42.254 | 0 | 1.96 |

| PH16 | 8.667 | 0.463 | 47.996 | 0 | 2 | |

| PH20 | 6.844 | 0.276 | 51.617 | 0 | 1.82 | |

| PH24 | 4.972 | 0.109 | 57.224 | 0 | 1.437 | |

| PH28 | 4.247 | 0.093 | 60.858 | 0 | 0.522 | |

| PH32 | 4.247 | 0.093 | 60.008 | 0 | 0.522 | |

| PH36 | 4.247 | 0.093 | 62.431 | 0 | 0.523 | |

| PH40 | 4.226 | 0.092 | 61.746 | 0 | 0.642 | |

| PH44 | 4.226 | 0.092 | 61.698 | 0 | 0.912 | |

| PH48 | 4.228 | 0.092 | 59.888 | 0 | 0.644 |

| Grid Import [kWh] | Operation Cost [$] | PV Self-Consumption [%] | Peak Energy Usage [kWh] | Thermal Discomfort [Kh] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PV-HP-TES | PH12 | 15.502 | 1.305 | 36.008 | 1.422 | 1.874 |

| PH16 | 15.248 | 1.239 | 44.221 | 1.235 | 1.936 | |

| PH20 | 15.31 | 1.248 | 38.172 | 1.23 | 1.526 | |

| PH24 | 15.199 | 1.229 | 39.125 | 1.218 | 1.828 | |

| PH28 | 15.08 | 1.216 | 41.839 | 1.23 | 1.089 | |

| PH32 | 14.924 | 1.2 | 41.583 | 1.23 | 1.109 | |

| PH36 | 14.771 | 1.185 | 40.19 | 1.23 | 2.035 | |

| PH40 | 14.709 | 1.184 | 41.4 | 1.233 | 0.971 | |

| PH44 | 14.528 | 1.165 | 42.683 | 1.207 | 1.622 | |

| PH48 | 14.632 | 1.171 | 43.343 | 1.207 | 1.413 | |

| PV-HP-BESS | PH12 | 10.925 | 0.626 | 44.684 | 0 | 1.813 |

| PH16 | 9.158 | 0.445 | 50.009 | 0 | 2.082 | |

| PH20 | 7.039 | 0.232 | 55.315 | 0 | 1.989 | |

| PH24 | 5.527 | 0.124 | 59.931 | 0 | 1.816 | |

| PH28 | 5.147 | 0.116 | 62.526 | 0 | 1.095 | |

| PH32 | 5.078 | 0.115 | 63.447 | 0 | 0.882 | |

| PH36 | 5.078 | 0.115 | 64.139 | 0 | 0.846 | |

| PH40 | 5.078 | 0.115 | 66.796 | 0 | 0.857 | |

| PH44 | 5.066 | 0.114 | 64.315 | 0 | 0.902 | |

| PH48 | 5.066 | 0.114 | 65.196 | 0 | 0.882 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Chen, W.-A.; Gao, Y.; Hu, Z. Comparative Analysis of Battery and Thermal Energy Storage for Residential Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems in Building Electrification. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219497

Liu M, Chen W-A, Gao Y, Hu Z. Comparative Analysis of Battery and Thermal Energy Storage for Residential Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems in Building Electrification. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219497

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Mingzhe, Wei-An Chen, Yuan Gao, and Zehuan Hu. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Battery and Thermal Energy Storage for Residential Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems in Building Electrification" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219497

APA StyleLiu, M., Chen, W.-A., Gao, Y., & Hu, Z. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Battery and Thermal Energy Storage for Residential Photovoltaic Heat Pump Systems in Building Electrification. Sustainability, 17(21), 9497. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219497