Abstract

Lithium-ion batteries are extensively used for energy storage in renewable, electronic, and automotive applications. However, once their electrical capacity is exhausted, they become hazardous waste that requires energy-intensive recycling processes. This study investigates the thermodynamic and exergetic behavior of LiMn2O4-based lithium-ion batteries subjected to controlled electrical overvoltage from renewable energy sources, aiming to quantify their potential for thermal energy generation and recovery. A detailed mathematical model was developed to describe the coupled heat transfer and electrochemical phenomena occurring during overvoltage conditions, and experimental validation was performed under various voltage levels and charging states. Energy and exergy analyses were applied to determine the configuration yielding the highest conversion efficiency for both new and aged cells. The maximum thermal energy efficiency reached 81% for new batteries and 4% for used batteries, while the corresponding exergetic efficiencies were 5% and 1.6%, respectively. Although this study does not propose the immediate large-scale reuse of spent batteries as thermal devices, the results provide quantitative insight into irreversible energy conversion processes and highlight their potential contribution to waste heat recovery and energy optimization strategies in sustainable industrial systems. This thermodynamic framework offers a novel approach for valorizing end-of-life batteries within circular energy models, reducing environmental impact, and advancing the integration of renewable energy-driven heat recovery technologies.

1. Introduction

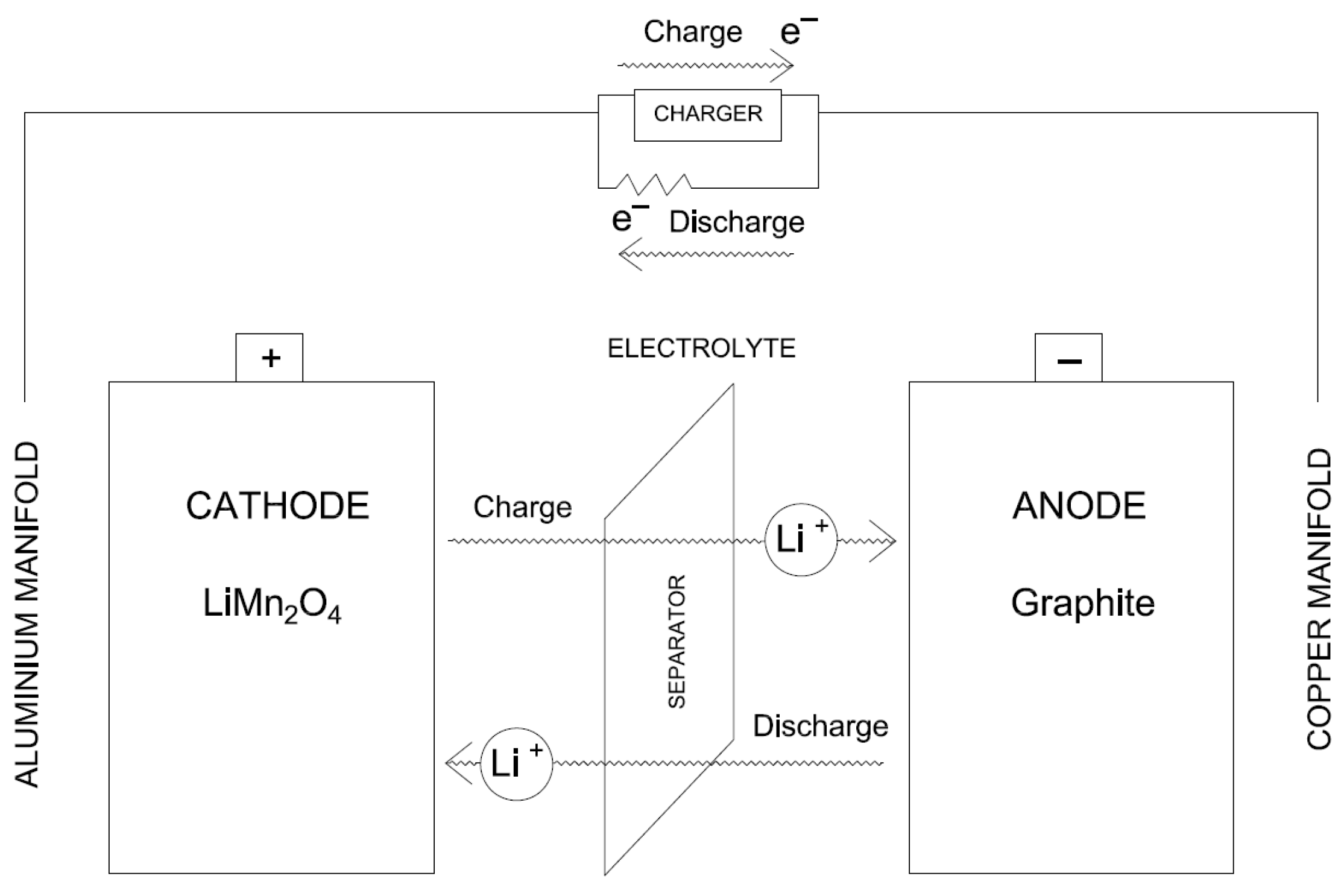

Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries have become indispensable in modern life, providing portable and rechargeable energy for electronic devices, as well as for electric and hybrid vehicles (EVs and HEVs). Their configuration follows the classical electrochemical cell structure [1], composed of two electrodes (anode and cathode), a liquid or solid electrolyte, and a permeable membrane that enables ionic transport between electrodes while preventing short circuits. Electricity generation results from oxidation–reduction reactions between the electrolyte and electrodes: during discharge, the electrolyte near the anode releases electrons (oxidation), which are accepted at the cathode (reduction), and this process reverses during charging.

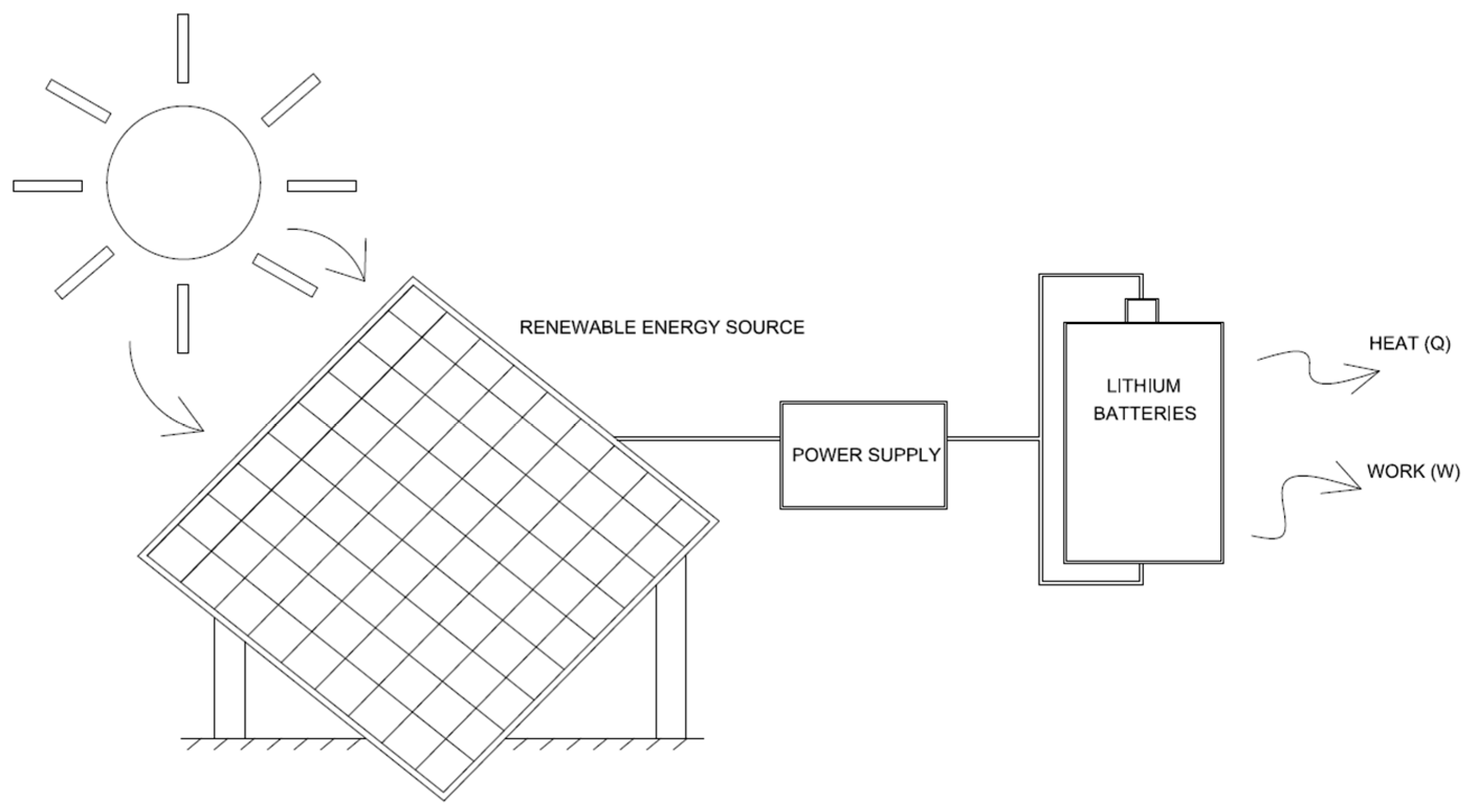

Thermal energy generation in Li-ion batteries results from the conversion of chemical energy released during electrochemical reactions under electric current. In this study, batteries were subjected to controlled overvoltage to activate oxidation–reduction processes and generate heat via the Joule effect. Quantifying this thermal energy and the maximum useful work available is of scientific and technological interest. This concept gains further relevance when powered by renewable electricity, such as photovoltaic solar energy, enabling the generation of clean and emission-free thermal energy. Combining renewable electrical power with lithium-ion batteries can thus yield sustainable thermal energy, particularly valuable at the end of their useful life, transforming them from waste into energetically and economically useful products.

With the growing implementation of renewable energies and storage technologies [2,3,4], the development of efficient, environmentally responsible processes is essential. Sustainable development through renewable energy and improved energy efficiency is a strategic goal of the European Union (EU) [5,6]. Increasing concern over greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has led to stricter regulations on pollutants and waste generation [7,8], including the new European regulation [9], which promotes a circular economy throughout the life cycle of batteries. Within this context, this work demonstrates that lithium-ion batteries can act as thermal energy storage systems, converting renewable electrical energy into heat for immediate or later use.

The main research question addressed is whether LiMn2O4 batteries subjected to controlled overvoltage can be repurposed as renewable sources of thermal energy. The study fills a clear research gap: no previous work has conducted a complete thermodynamic and exergetic analysis of the conversion of electrical input into recoverable thermal energy. The corresponding energy and exergy efficiencies had not been previously determined.

The key contributions and novelties of this study are summarized as follows:

- A thermodynamic and heat transfer analysis of Li-ion batteries subjected to power overvoltage is performed for the first time to quantify the generated thermal energy.

- A detailed mathematical model of the overvoltage process using renewable electrical energy on a LiMn2O4 cathode battery was developed and validated under various thermal and electrical conditions.

- Energy and exergy analyses identified the configurations achieving the highest efficiency and performance for both new and used batteries, providing, for the first time, the maximum energy and exergetic efficiency values.

- An effective analytical method was developed to evaluate lithium-ion batteries as thermal energy sources, improving overall energy efficiency and reducing emissions.

- The reuse of new and used lithium batteries as renewable-powered thermal generators was proposed, revealing potential applications for thermal energy storage and contributing to carbon footprint reduction.

Finally, the study’s limitations stem from its focus on LiMn2O4 chemistry; however, the proposed methodology can be generalized to other cathode materials by adjusting reaction parameters, establishing a robust framework for the thermodynamic valorization of secondary lithium batteries.

2. Literature Review

Commercial Li-ion batteries differ mainly in cathode composition, commonly employing iron phosphate, cobalt oxide, or manganese oxide [10]. Iron phosphate batteries exhibit lower energy density and voltage, limiting their suitability for high-power automotive applications [11]. Li-ion batteries, although offering high energy density, often provide less discharge capacity than Li-polymer packs [12]. Several studies have also examined hybrid systems combining PEM fuel cells and Li-polymer batteries under transient power conditions [13]. Cobalt oxide cathodes, despite their efficiency, pose environmental and economic concerns due to toxicity and cobalt scarcity [14]. In contrast, manganese oxide cathodes are non-toxic, safe, and low-cost, with good performance under high and low discharge rates [15,16]. Consequently, MnO2, particularly in LiMn2O4 spinel form, is one of the most used cathode materials in secondary Li-ion batteries [17,18,19,20,21]. Thus, this study focuses on secondary LiMn2O4-based batteries.

The current state of research on the thermal behavior of lithium-ion batteries can be summarized as follows. Several studies have examined heat generation in lithium-ion batteries, although most have focused on mitigating temperature rise rather than recovering the generated thermal energy. Previous works have proposed thermal models to simulate phase transitions in electrode materials using internal heat sources [22] and to compare different phase change materials for battery thermal management [23]. Other studies have incorporated nanomaterials into battery thermal management systems (BTMS) to enhance heat dissipation [24]. Additional approaches have analyzed heat accumulation through combined PCM–air convection systems [25] and explored alternative materials to improve cooling efficiency [26]. More recent research has investigated thermal regulation in electric and hybrid vehicles to extend battery lifespan [27,28]. However, none of these studies addressed the potential recovery and valorization of the heat generated as a usable energy source. Previous studies have examined the thermal behavior of Li-ion batteries under abusive conditions, such as overcharge and short-circuit scenarios, where electrical energy is unintentionally converted into heat. In contrast, the present work intentionally applies controlled overvoltage to repurpose this heat generation as a renewable and recoverable energy source. This represents a paradigm shift from mitigating heat as a risk to exploiting it as a valuable output, quantified through a detailed exergy analysis that has not been previously reported.

The electrochemical behavior and operating principles of Li-ion cells have been widely reviewed, emphasizing the nature of the intercalation and deintercalation processes of lithium ions within electrode materials [29]. Likewise, recent works have provided fundamental insights into the electrochemical mechanisms and design parameters governing the efficiency and stability of lithium-ion batteries [30]. Furthermore, the influence of electrode architecture, material selection, and nanostructuring has been identified as a key factor in improving energy density, lifetime, and overall performance [31]. Based on this foundation, the present research develops a thermodynamic and exergetic model to quantify the thermal energy and useful work that can be obtained from LiMn2O4 batteries under overvoltage conditions. Although this study focuses on manganese oxide cathodes, the proposed model can be adapted to other chemistries by substituting their thermophysical and reaction parameters. The mathematical framework calculates the thermal energy released, entropy generated, exergy destroyed (irreversibility), and maximum reversible work obtainable. The potential applications of these systems are diverse, such as their use as heat sources or for conversion of thermal energy into mechanical work. Despite their advantages, lithium-ion batteries become waste at the end of their service life, requiring substantial energy and cost for material recovery [32,33]. Moreover, their environmental impact may exceed that of alternative systems such as proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells [34]. To mitigate this issue and reduce their carbon footprint, this study analyzes the thermal behavior of Li-ion batteries and develops mathematical and physicochemical models for utilizing their generated thermal energy.

Chemical Reactions During Charging and Discharging of the LiMn2O4 Battery

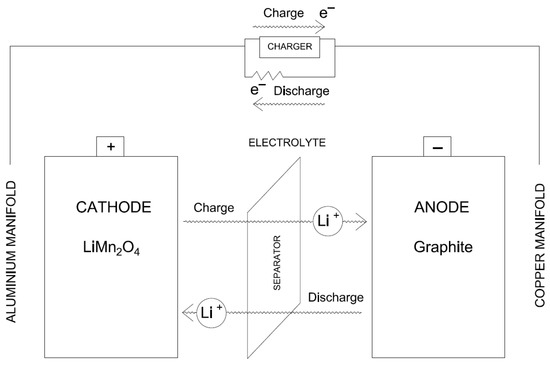

As illustrated in Figure 1, the operating diagram of a LiMn2O4 battery demonstrates the direction of electron (i.e., electric current) and lithium-ion circulation during the battery’s charging and discharging processes.

Figure 1.

LiMn2O2 battery operation scheme.

During the process of battery discharge, electrons are transferred from the anode to the cathode through an external circuit, thereby generating electrical current and enabling the battery to supply power to an external device. Furthermore, lithium ions (Li+) are known to migrate from the anode to the cathode, facilitated by the electrolyte. During the charging process, the direction of the cycle is reversed. In essence, the movement of electrons and Li+ ions occurs from the cathode to the anode, and the chemical reactions transpire in the reverse direction. During the charging process, lithium ions migrate to the negative electrode, where they react with the electrons to intercalate in the solid particles of manganese oxide, forming LiMn2O4 molecules.

During the discharge process, Li+ ions migrate from the anode (LiC6) to the cathode (Mn2O4), where they are inserted forming LiMn2O4. Conversely, during charging, Li+ ions deintercalate from the LiMn2O4 structure and return to the anode, where they react with graphite to form LiC6 again. Therefore, the redox reactions can be expressed as follows [35]:

Anode (discharge): LiC6 → 6C + Li+ + e−

Cathode (discharge): Mn2O4 + Li+ + e− → LiMn2O4

These reactions are reversed during charging.

3. Methodology and Analysis

3.1. Description of Model and Experimental Installation

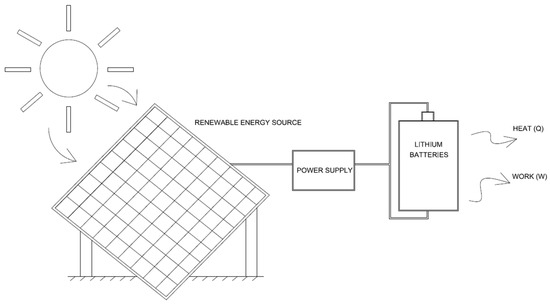

The battery model utilized in the experimental procedure was a lithium battery equipped with a manganese oxide cathode, an approximate charge capacity of 800 milliampere-hours (mAh), and a nominal voltage of 3 volts (V). To induce electrical overvoltage in the battery, its poles or terminals were connected to a power source. The laboratory’s photovoltaic solar system, situated on the roof, was utilized to obtain electrical energy. Subsequently, energy from a renewable source was utilized to supply a different over-voltage to the lithium battery through an electrical power source. As illustrated in Figure 2, the process entails the utilization of electrical energy from a renewable source to generate thermal energy, with the subsequent conversion of lithium batteries into a source of useful work.

Figure 2.

Picture of how lithium batteries generate heat and use it to do useful work.

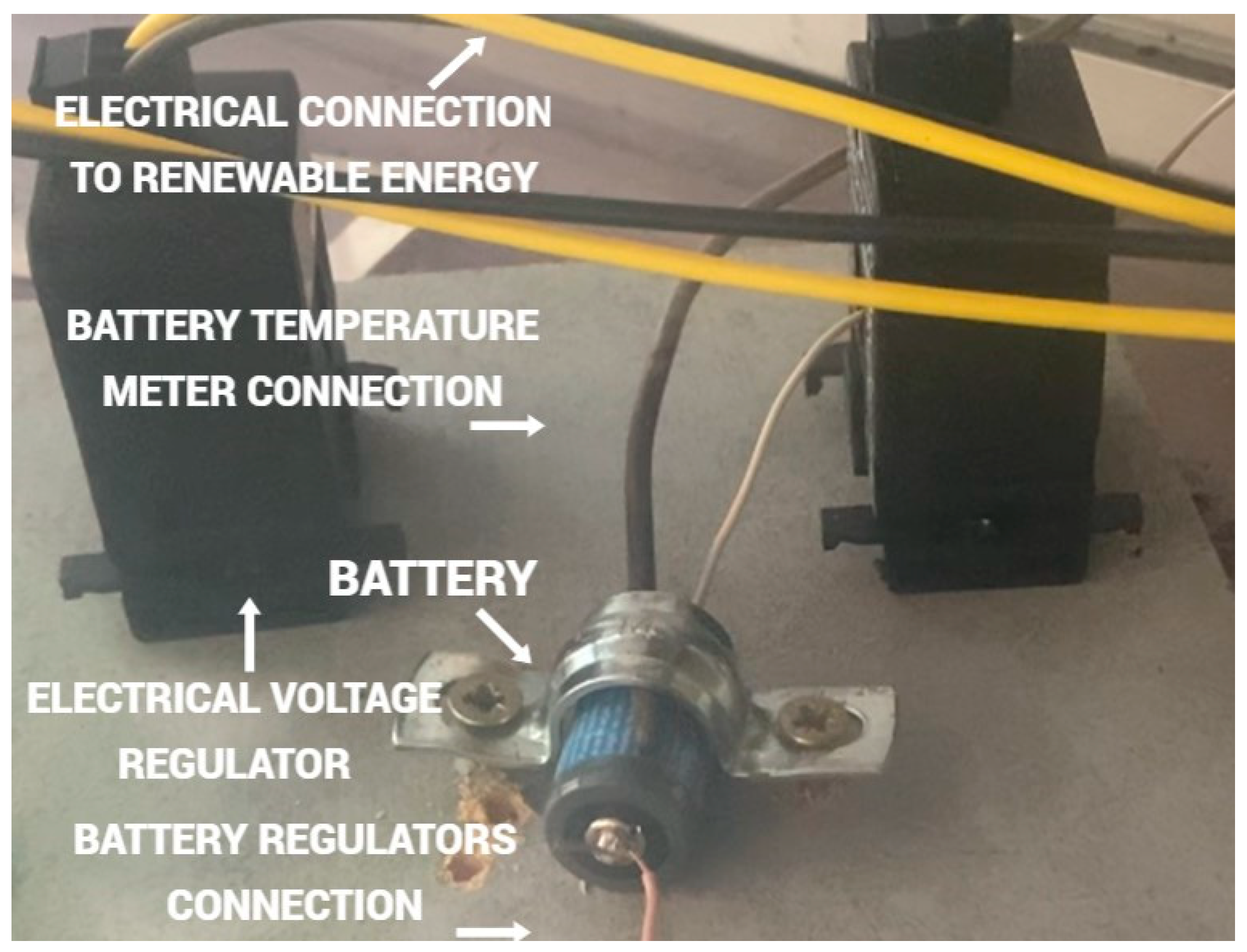

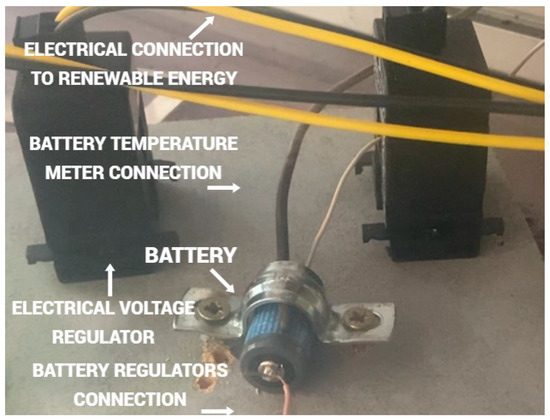

The measurements were obtained using K-type thermocouple temperature probes with metal sheaths, with a measuring range of approximately −200 °C to +1250 °C. These probes were connected to the battery surface, and the resulting data were recorded using a Comet System model MS6D data logger. The data were then downloaded using Monitoring Systems MS series software (Version SWR003). Consequently, the surface temperatures of the battery under overvoltage conditions for a duration of 290 min were obtained. The ambient temperature and atmospheric pressure were measured during the course of the various tests. As illustrated in Figure 3, the test setup is composed of several components.

Figure 3.

Experimental facility.

All experiments were performed within a thermal safety enclosure with real-time monitoring of temperature, current, and voltage. An automatic relay disconnected the circuit when the battery surface temperature exceeded 90 °C to prevent thermal runaway. The setup included a non-combustible ceramic base and a vented polycarbonate protection chamber.

3.2. Model Validation

When an electric current was applied to the battery, its surface temperature progressively increased until reaching a steady maximum value. Simultaneously, heat was dissipated from the battery to the surrounding environment, contributing to the overall heat exchange process. This thermal behavior was used to validate the proposed model by quantifying the amount of heat released by the battery during the subsequent cooling phase. The heat was calculated in two distinct methods and the results were subsequently compared. The initial approach entails an energy balance of the overvoltage process within the battery. The second method involves the application of a formula that relates the amount of heat exchanged by a substance of a given mass and specific heat to a given temperature change. The energy model is delineated in Section 4, and the formula relating the heat given off to the specific heat of the substance, which is a known and validated equation in classical thermodynamics, is as follows [36]:

3.3. Dynamic Tests Description

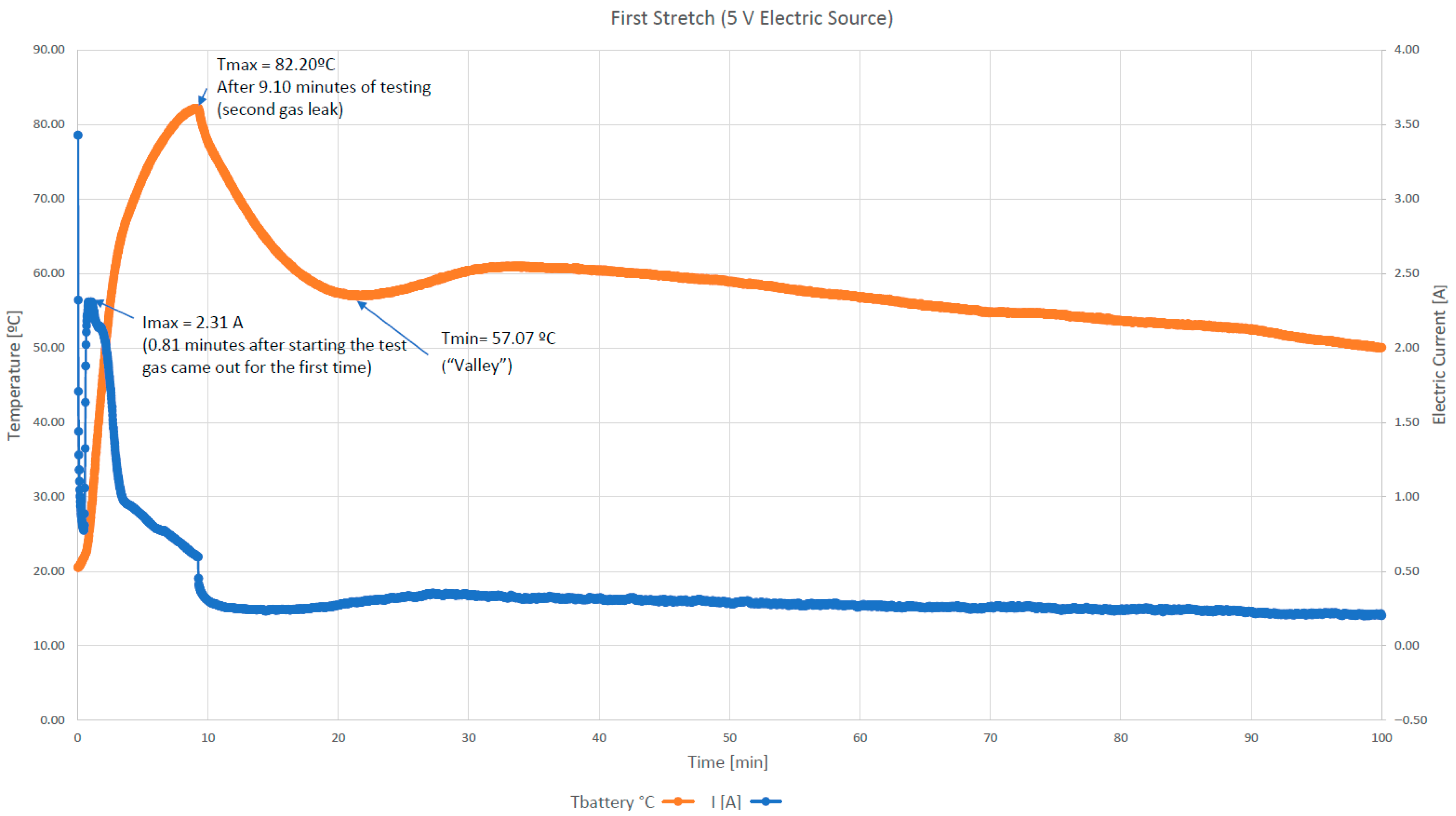

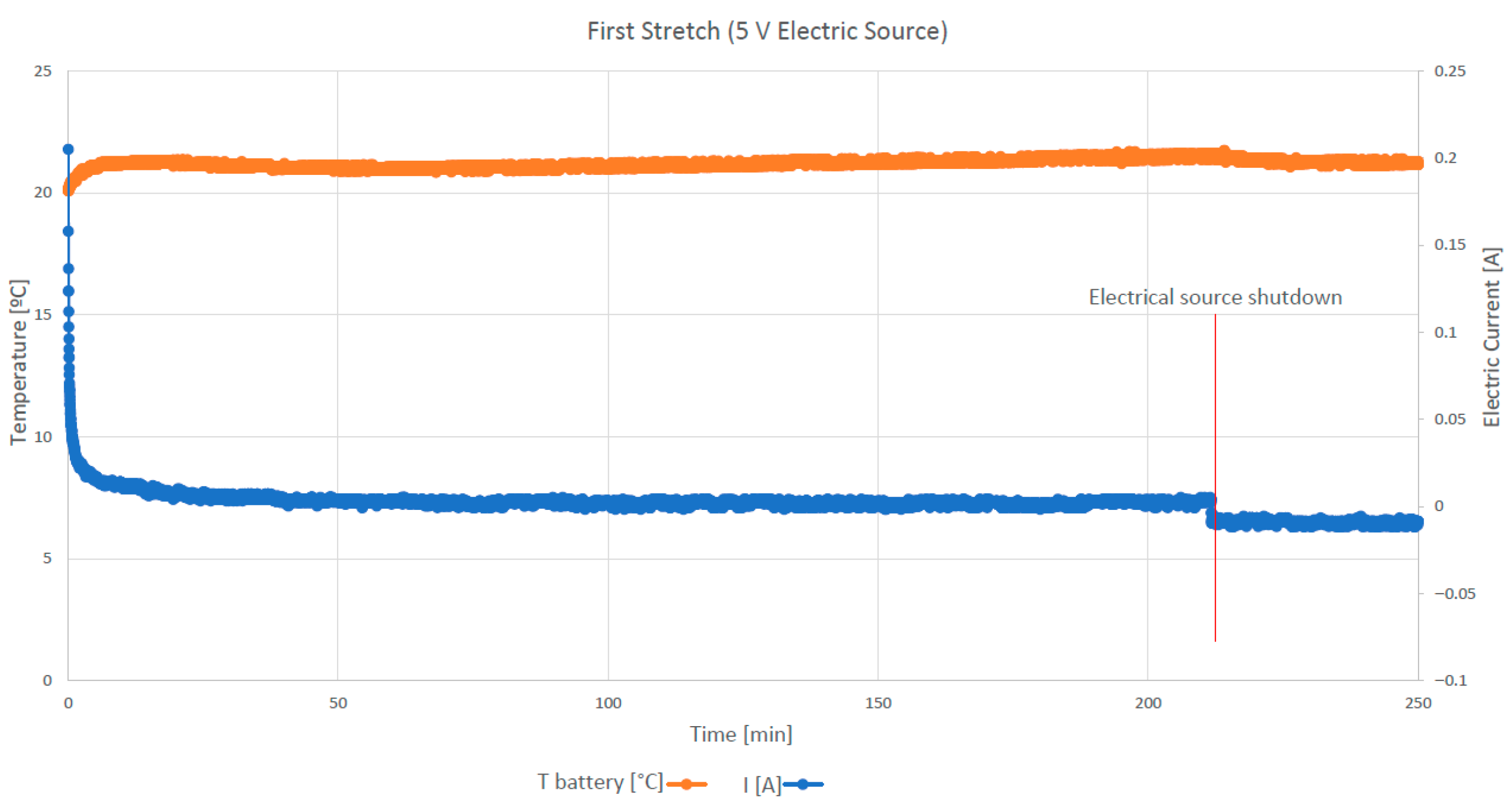

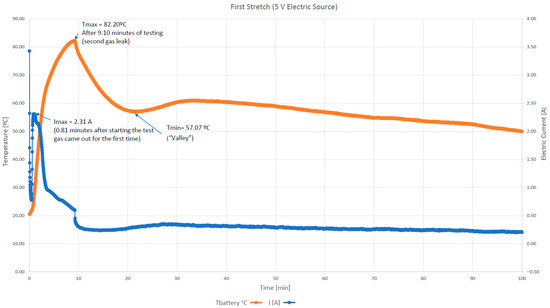

3.3.1. Test 1 by Applying a Voltage of 5 V to a Charged Battery

A single charged lithium battery (3.28 V) was subjected to a constant voltage of 5 V for a duration of 100 min. In this experiment, the external temperature of the battery was measured under constant ambient temperature conditions of 20 °C. The maximum recorded temperature was 82.20 °C, which was attained at 9.1 min. This temperature was achieved rapidly by heat transfer from the interior of the battery to its exterior surface. Subsequent to attaining this maximum, the surface temperature underwent a rapid decline. This phenomenon can be attributed to two primary factors. Firstly, a constant flow of heat was observed to be emanating from the system, indicating a loss of thermal energy. Secondly, the culmination of chemical reactions that occurred during the charging process was noted, as outlined in Section 1. Following a brief period of elevated temperature, which was observed approximately 20 min into the testing process, the temperature underwent a gradual decline, stabilizing at a constant range between 50 and 60 °C. Conversely, two gas leaks occurred at the cathode. The initial leakage occurred within the first minute, and the subsequent leakage occurred after nine minutes of testing. During the initial stage of overvoltage application, a slight release of gases was occasionally observed, primarily associated with electrolyte oxidation and partial oxygen evolution from the Mn4+ reduction in the LiMn2O4 cathode. The oxidative decomposition of carbonate-based electrolytes produced trace amounts of CO2, CO, and light hydrocarbons, increasing the internal pressure of the cell and inducing minor lattice distortions in the cathode. These parasitic reactions decreased the electrochemically active surface area and altered the lithium inventory, thereby enhancing the irreversible nature of heat generation.

The experiments were conducted under tightly controlled laboratory conditions using identical batteries from the same batch, with constant temperature and a monitored renewable power supply. Repeated trials confirmed the reproducibility of the data, with temperature and current deviations below ±2.5%, now reported as the experimental uncertainty. The abnormal initial current peak observed in Test 1 was attributed to transient capacitive charging at the electrode–electrolyte interface, followed by a small leakage current linked to electrolyte decomposition. The limited amount of evolved gas (mainly CO2 and O2) remained well below safety thresholds, and no signs of venting, ignition, or thermal runaway were detected, confirming that the applied overvoltage remained within a stable and controlled range. A slight increase in current was observed in Test 1, occurring simultaneously with the temperature rise. This behavior is attributed to the temperature-dependent enhancement of ionic and electronic conductivity, together with minor electrochemical side reactions activated under overvoltage conditions.

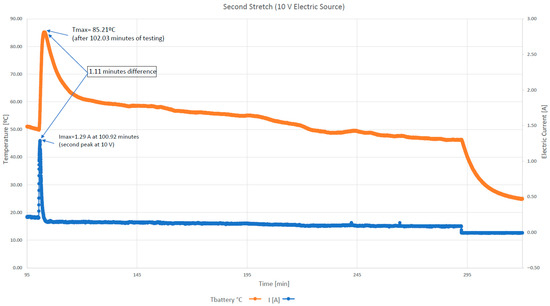

3.3.2. Test 2 by Applying a Voltage of 10 V to a Charged Battery

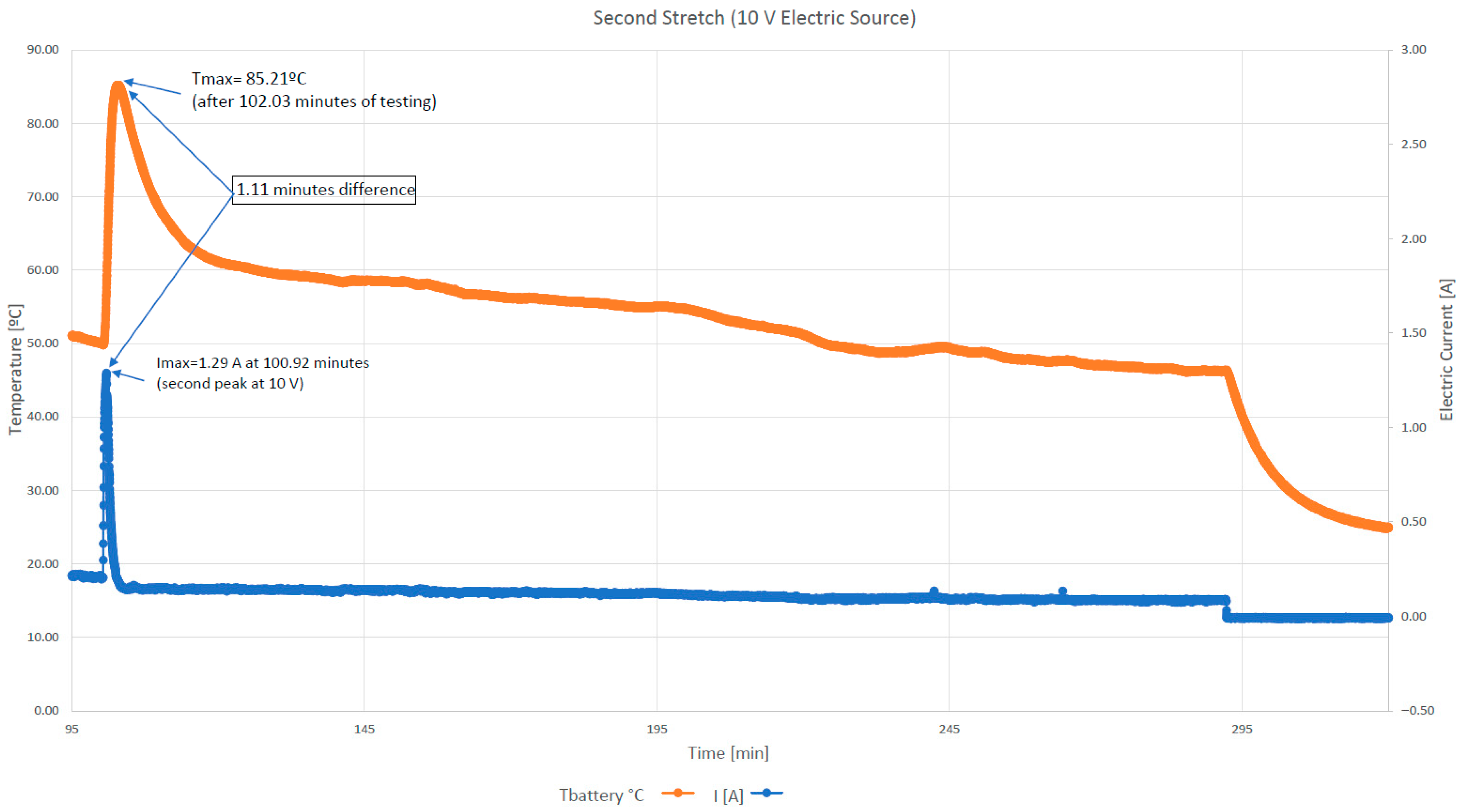

Subsequent to the conclusion of the initial evaluation, and without compromising the integrity of the battery’s power supply, a constant voltage of 10 volts was maintained for a duration of 190 min. As was the case in the preceding instance, the ambient temperature was maintained at 20 °C, and the external temperature of the battery was measured. The maximum recorded temperature, 85.21 °C, was obtained at 2.03 min. As was the case in Test 1, the rate of heat transfer from the interior of the battery to its exterior surface rapidly achieved this temperature. The subsequent decline in temperature was precipitous, and, in contrast to the preceding peak, no subsequent recovery in temperature was observed during this phase of decline. Concurrently, the current intensity exhibited an upward trend, attaining a maximum peak of 1.29 A at 0.92 min following the commencement of the process, with a 10 V overvoltage. Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the data obtained from tests 1 and 2, respectively. The blue curve indicates the variation in the current intensity as a function of time, while the orange curve shows the variation in the temperature on the surface of the battery as a function of time.

Figure 4.

The effect of a 5 V overvoltage applied to a LiMn2O4 charged battery for 100 min. Temperature vs. Time Diagram.

Figure 5.

Th effect of a 10 V overvoltage applied to a LiMn2O4 charged battery for 190 min. Temperature vs. Time Diagram.

The temperature decrease after reaching the maximum peak occurred rapidly and without recovery, not due to a measurement deviation but to the cessation of exothermic reactions once the internal electrochemical activity stabilized. The subsequent cooling was governed by conductive and convective heat dissipation through the metallic casing, consistent with the expected transient thermal behavior of the system.

3.3.3. Test 3 by Applying a Voltage of 5 V to a Discharged Battery

The lithium battery utilized in the initial tests was subjected to a constant voltage of 5 V for a duration of 144 min. In this test, the battery was discharged to a cutoff voltage of 1.85 V under controlled conditions. In this study, the external temperature of the battery was measured while maintaining a constant ambient temperature of 20 °C. During the test, the battery exhibited an absence of current flow. The surface temperature of the battery exhibited a minimal increase of 2 °C, after which it stabilized, and the current decreased to 0 A, as illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The effect of a 5 V overvoltage applied to a LiMn2O4 discharged battery for 144 min. Temperature vs. Time Diagram.

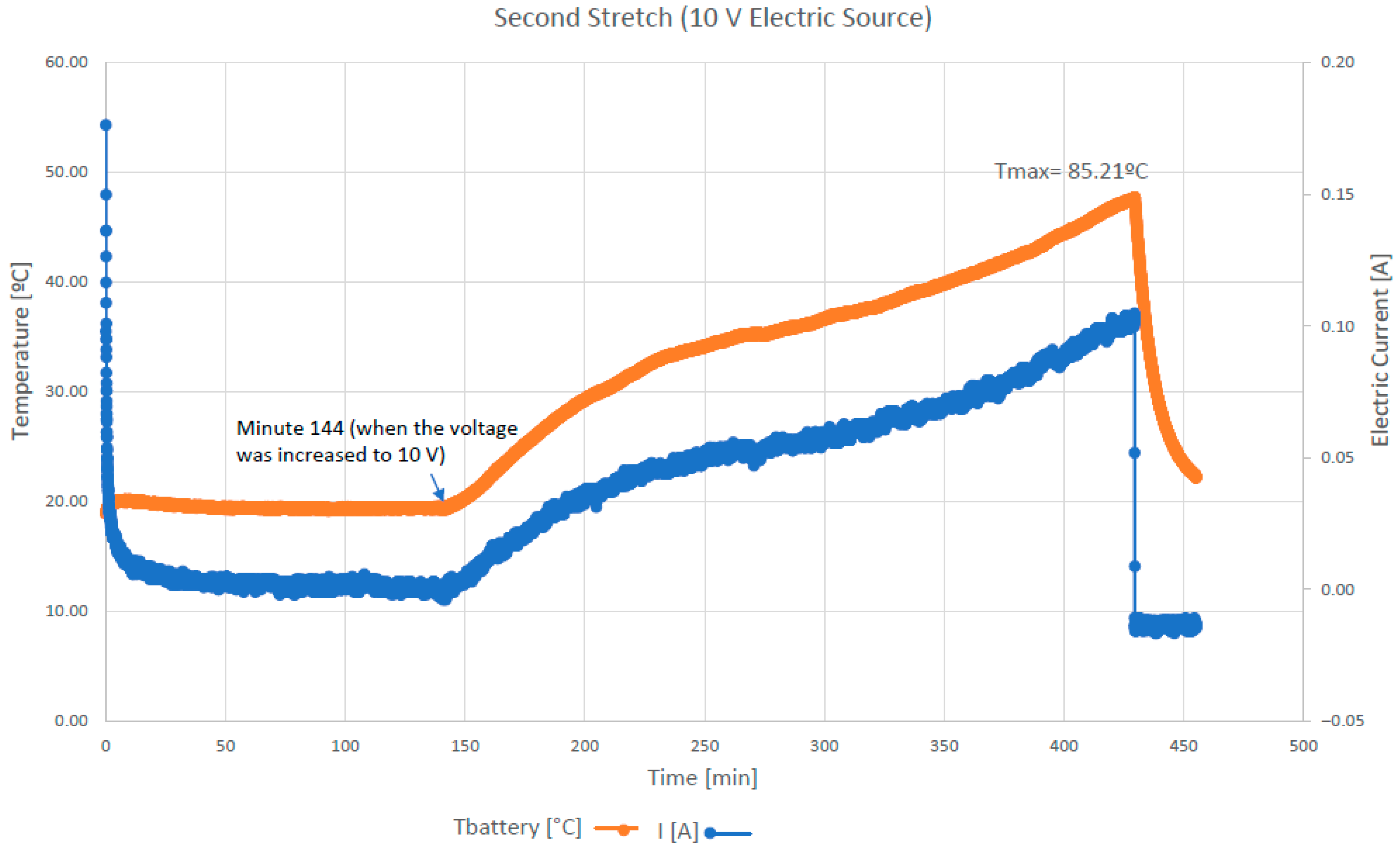

3.3.4. Test 4 by Applying a Voltage of 10 V to a Discharged Battery

At minute 144 of test 3, the source voltage was increased to 10 V. Despite the increase in source voltage, no current continued to flow through the battery. However, at minute 151, a current of 0.01 A began to flow and the battery temperature gradually increased to a maximum of 47.72 °C. This phenomenon is illustrated in Figure 7. This minor current is attributed to parasitic electrochemical reactions and self-discharge phenomena occurring after the main redox processes had ceased. Such behavior is typical of aged LiMn2O4 cells under extended overvoltage exposure and reflects residual charge redistribution and electrolyte decomposition rather than active electrochemical activity.

Figure 7.

The effect of a 10 V overvoltage applied to a LiMn2O4 discharged battery for 460 min. Temperature vs. Time Diagram.

The same cell was subjected to four consecutive tests to maintain identical experimental geometry. Internal resistance and open-circuit voltage were monitored before and after each test to detect degradation. Although variations in thermal response were below 3%, chemical alterations accumulated during the sequence may have influenced the results. Future experiments will employ independent cells per condition to confirm reproducibility.

3.4. Energy Analysis

3.4.1. Energy Balance

The energy balance, as described by the first law of thermodynamics, is applied to the dynamic model in the following detailed description. The formulation of this equation was developed for chemically reactive closed systems at rest [36], and is expressed as follows:

Using the definition of enthalpy [36], the following holds:

Or

The energy balance can be written as follows [37,38,39]:

It is essential to ensure that the energy input from the battery during surge operation equals the total energy output from the system, thereby maintaining the balance required for thermodynamic consistency. This energy input comprised electrical work, while the energy output manifested as heat dissipated by the battery. The energy balance resulting from the endothermic and exothermic reactions that occurred during the battery charging process was also considered. The system under scrutiny was the dynamic model delineated in Section 3.1.

The terms are negligible when dealing with liquids or solids. Therefore, this value was not considered. The environmental conditions were 25 °C and 1 atm of atmospheric pressure. Therefore, under these conditions . Thermophysical and thermochemical data were collected from reliable literature sources to ensure the accuracy of the proposed model. As shown in Table 1, the specific heat capacity values of the materials were obtained in accordance with the data reported in standard references [40,41,42,43]. The enthalpy of formation at the reference state for both reactants and products was taken from established thermochemical databases and previous studies [40,44,45]. The table also presents the corresponding masses of the reactants and products involved in the electrochemical reactions occurring at the anode and cathode of the battery. These parameters were subsequently used in the energy and exergy balance calculations to quantify the thermal behavior and efficiency of the system under overvoltage conditions.

Table 1.

Heat capacities, enthalpies of formation, and masses for the different compounds at the lithium battery electrodes with the manganese oxide cathode.

The energy balance identifies both the input and output work (W) performed on or by the system consisting of the overvoltage batteries, as well as the heat (Q) administered or produced by the system and the net transfer of energy into the system (represented by the sum of the reagents), or out of the system per mole of reacting material (represented by the sum of the products). The system was subjected to an electrical overvoltage that defined a = I · V.

With the characteristics described above, the test presented an energy balance that was simplified as follows [46]:

Or

3.4.2. Calculating the Internal Temperature When the Battery Surface Temperature Is Known

The effect of heat transfer by internal convection is negligible due to the unknown value of the internal convection film coefficient. Consequently, this effect is ignored in the analysis. The calculation of the overall heat transfer coefficient was conducted in accordance with the following methodology [47]:

where r1 is the inner radius of the cylindrical lithium battery, r2 is the outer radius, including the outer coating and the thickness of the metal cylinder and k the thermal conductivity coefficient of the battery metallic material. Table 2 represents the dimensions and properties of the analyzed battery. Here, c is the specific heat of the battery.

Table 2.

LiMn2O4 battery dimensions and characteristics.

Therefore,

where S = 2π · r2 · L and ΔT = Ts − Ti.

3.4.3. Energy Efficiency

The energy efficiency value of the process was determined through the application of the first law of thermodynamics, as expressed in the following equation:

3.5. Entropy and Exergy Analysis

3.5.1. Entropy Balance

In the continuation of the thermodynamic analysis of the battery overvoltage process, the entropy change of the system was analyzed through an entropy balance. This analysis enabled the determination of the entropy generated in the process. Consequently, the destroyed exergy was obtained. In both cases, the equations were based on the theoretical developments of the well-known texts of Çengel et al. and Bejar et al. [36,53]:

where Sgenerated is the entropy generated by the system, Sproducts and Sreagents are the entropy of the products and reactants of the chemical reactions, respectively. Furthermore, in our case the input entropy (Sin), the output entropy (Sout), and the difference between the entropy of the products (Sproducts) and the reagents (Sreagents) were calculated as follows:

where R = 0.08206 = 8.314 and P0 = 1 atm.

is equal to 1 for independent solids. Where V and n are the total volume and number of moles of reagents and products, respectively, and depend on whether the entropy of reagents or products is calculated. The value of V for the cylindrical battery was π·rin2·L, as measured in Table 2. The values of the entropy of formation in the reference state for the reactants and products were obtained from Perry et al. [40] and are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Entropy of formation values for the various compounds present at the electrodes of the lithium battery with manganese oxide cathode.

3.5.2. Exergetic Calculations

The calculation of the destroyed exergy, or the irreversibility of the overcharging process in the lithium battery, was performed using the following equation:

Recalling that T0 was 298 K:

The value of the exergy efficiency of the process was calculated by applying the second law of thermodynamics, as indicated by the following equation [36]:

It should be noted that under overvoltage conditions, electrochemical side reactions such as SEI film decomposition and limited gas evolution may occur [6,32]. These effects, although not quantified in this work, could contribute marginally to entropy and exergy variation. Future studies will incorporate EIS and galvanostatic measurements to validate the thermodynamic–electrochemical coupling in these systems

3.6. Maximum or Reversible Work

In the case under analysis, wherein heat transfer to the environment occurred without any alteration in kinetic and potential energies, the reversible or maximum work (Wmax) that could theoretically be accomplished during the process was determined using the following formula, as outlined in the works of Çengel et al. and Bejar et al. [36,53]:

Therefore, as defined above, the following holds:

3.7. Experimental Safety Protocols and Risk Mitigation

To ensure safe operation, all overvoltage experiments were conducted inside a ventilated containment chamber equipped with temperature, current, and pressure sensors to ensure safe operation. The ambient temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C, and each cell was monitored in real time for voltage, surface temperature, and internal resistance. In addition to electrical monitoring, gas-detection sensors were used to identify possible emissions of CO2 and O2 resulting from side reactions. These gases are primarily generated by electrolyte decomposition (LiPF6 → PF5 + HF + CO2) and by partial oxygen evolution from the MnO2 cathode during overvoltage conditions.

The applied DC overvoltages (5 V and 10 V) were selected based on preliminary tests to remain below the critical thresholds that trigger exothermic decomposition or thermal runaway (typically above 120 °C for LiMn2O4 systems). The maximum recorded temperature never exceeded 90 °C, well below the onset of self-accelerated reactions. Experiments were automatically stopped if temperature or internal pressure increased abnormally. Fire-suppression equipment and remote shut-off controls were in place throughout all tests.

These measures, together with the strict monitoring of voltage and temperature profiles, effectively prevented any instance of venting or ignition. The safety protocol complied with international laboratory standards for testing lithium-ion systems and ensured that the observed gas emissions occurred under controlled, non-hazardous conditions.

4. Results

4.1. Test 1 Applying a Voltage of 5 V to a Charged Battery

The outcomes of the model validation process demonstrated the reliability of the energy model utilized in this study. Therefore, analogous values were derived through the application of Equations (3) and (8) to ascertain the heat dissipated by the battery from the commencement of Test 1 until the attainment of the maximum battery surface temperature. The results indicated that the total heat released by the cell under a 5 V overvoltage ranged between 1487.82 J (as calculated from Equation (3)) and 1434.48 J (from Equation (8)), corresponding to a surface temperature rise from 25 °C to 82.2 °C.

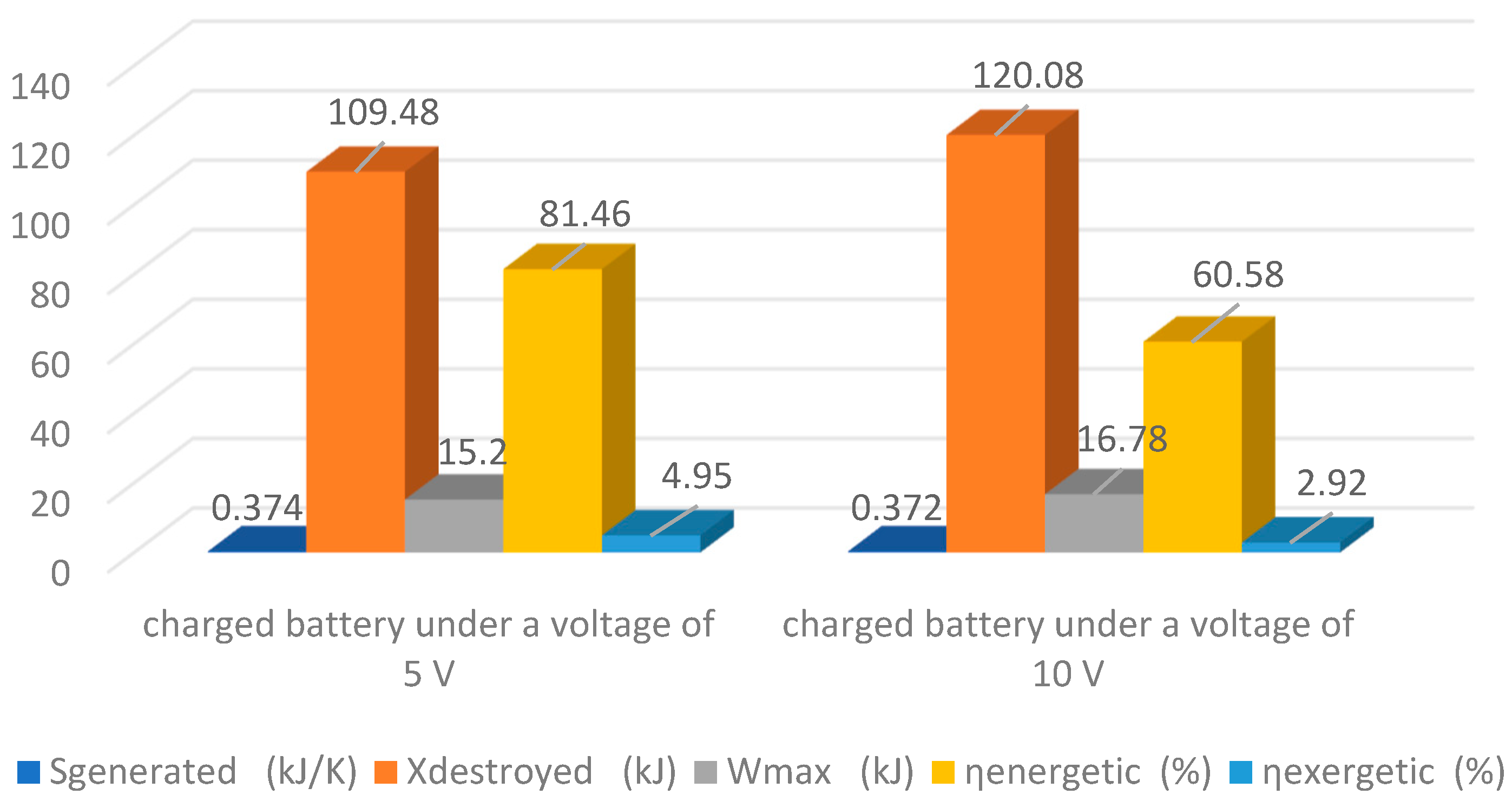

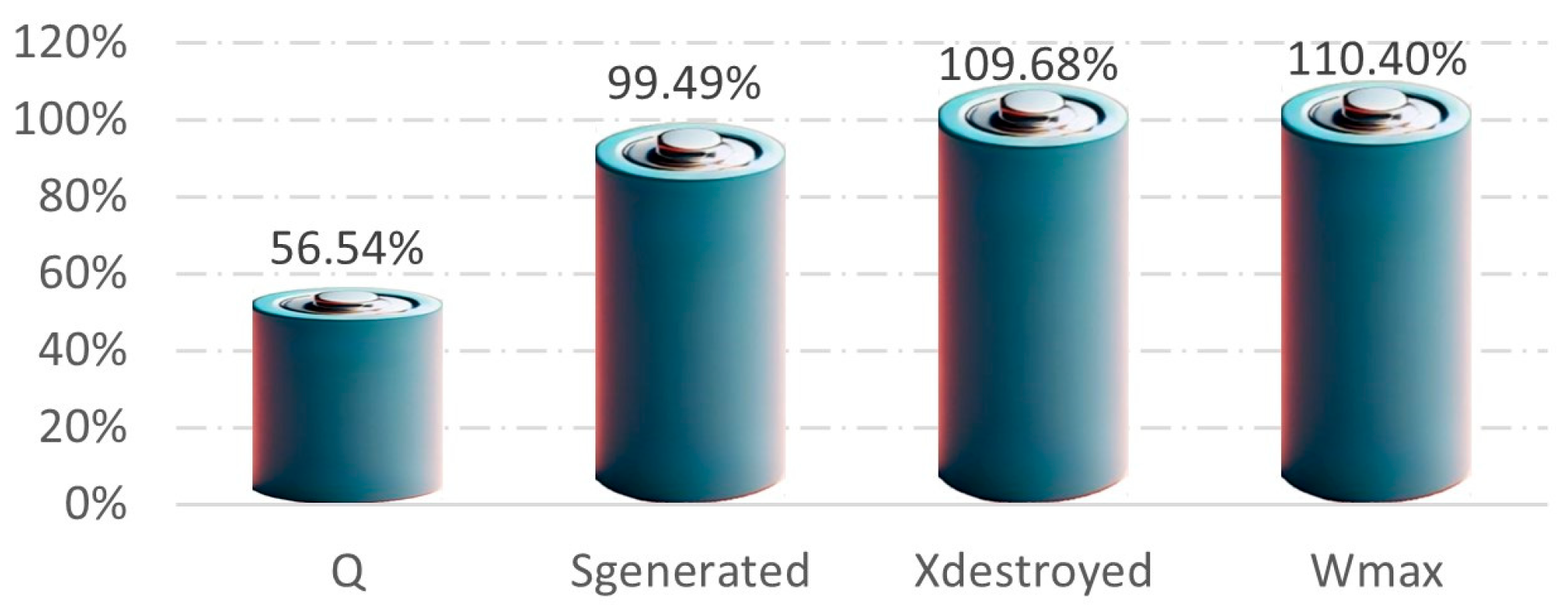

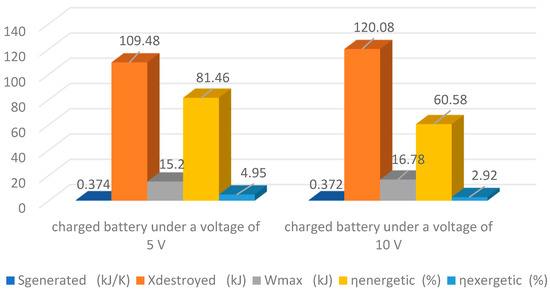

To ensure the reproducibility and statistical robustness of the measurements, each experimental configuration was repeated three times under identical ambient and electrical conditions. The results obtained in the replicates showed a high degree of consistency, with variations in the maximum recorded temperature and current intensity remaining below ± 2.5% and ± 3.0%, respectively. The standard deviation of the calculated thermal energy (Q) did not exceed ± 2.1% across all tests. These deviations were considered acceptable within the experimental uncertainty of the thermocouple sensors and power source accuracy, confirming the reliability of the obtained data. The uncertainty ranges derived from these repetitions as error margins for the reported Q values. The value of Q varies by 3.6%, a discrepancy that may be attributed to minute alterations in the weight of the battery, the values of the thermal constants employed, or the precision of the electrical measuring instruments. Consequently, the value of the thermal energy released in the form of heat and calculated with the energy balance is deemed satisfactory and enables the subsequent determination of the entropy generated, the exergy destroyed, and the maximum or reversible work, as illustrated in Figure 8. The figure facilitates the observation of variations resulting from the application of surges ranging from 5 to 10 V. Consequently, the necessity for augmenting the surge in the battery can be assessed based on the findings derived from the experimental results.

Figure 8.

The values of the maximum generated entropy, destroyed exergy, maximum or reversible work, and maximum energy and exergy efficiency of the charged battery under voltages of 5 V and 10 V.

4.2. Test 2 Applying a 10 V Surge to a Charged Battery

The values of Q were calculated from the end of Test 1 up to the maximum heat released under an applied surge of 10 V. The results showed that the heat dissipated by the battery reached 841.18 J according to Equation (3) and 841.22 J according to Equation (8), corresponding to a surface temperature increase from 50 °C to 85.2 °C. The near-identical values obtained through both formulations confirm the consistency and reliability of the energy balance method used. Figure 8 further presents the corresponding variations in maximum entropy generation, exergy destruction, and reversible (maximum) work under a 10 V overvoltage. The comparison between the 5 V and 10 V conditions highlights the influence of the applied electrical surge on the thermal and thermodynamic behavior of the system, providing a basis for assessing the necessity and effect of increasing the overvoltage applied to the battery.

The results of this study are presented in Figure 9. The figure indicates that with an increase in voltage of 100%, the rise in heat generation is slightly more than 50%. However, the increase in entropy generation is twice as high, and both the exergy destroyed and the maximum work available increase by approximately 110%. These trends are case-specific and do not imply proportional scaling with voltage. Additional experiments across multiple voltage steps and ranges are required to determine the functional dependence of thermal and exergetic responses on overvoltage and to identify safe operating limits beyond 10 V. Despite the absence of extant literature comparing the results obtained in LiMn2O4 batteries with those from other research, the values obtained in this study could be indicative of destroyed entropy and exergy, as observed in other research with batteries. For instance, it has been demonstrated that an increase in temperature in lithium batteries induced by an electric field results in an increase in entropy content [54,55]. It has been established that the rate of irreversibility or destruction of exergy is proportional to the production of entropy. Therefore, an increase in entropy would produce a proportional increase in the destruction of exergy [36,56].

Figure 9.

Q, Sgenerated, Xdestroyed and Wmax increments by varying the power applied to the charged battery from 5 V to 10 V.

4.3. Test 3 Applying a Voltage of 5 V to a Discharged Battery

This test did not result in a substantial increase in battery temperature, thereby indicating that no thermal energy in the forms of heat, entropy, work, or exergy was generated.

4.4. Test 4 Applying a Voltage of 10 V to a Discharged Battery

An increase of up to 27.72 °C in the surface temperature of the battery was observed. The reactions that transpired were not known, but they exhibited a marked endothermic character, as evidenced by the fact that the heat value obtained with Equation (3) (Q = 663.06 J) was lower than the thermal energy supplied to the battery during the overvoltage process due to the Joule effect. The maximum values of energy and exergy performance were determined to be 3.93% and 1.60%, respectively.

Although the experimental work in this study was carried out exclusively on LiMn2O4-based lithium-ion batteries, the thermodynamic and exergetic model developed is not limited to this chemistry. From a theoretical standpoint, the same formulation can be extended to other secondary battery systems by introducing the corresponding thermophysical and reaction data for each material. For instance, LiFePO4 and NMC (LiNiMnCoO2) batteries are widely used alternatives that differ significantly in specific energy, stability, and degradation mechanisms. LiFePO4 systems, while exhibiting lower energy density, present higher thermal stability and safety margins, which would likely result in lower exergy destruction under similar overvoltage conditions. Conversely, NMC systems, due to their higher voltage and energy density, may generate greater thermal power but also exhibit a higher degree of irreversibility. The adaptability of the present model to these chemistries provides a robust framework for future comparative analyses aimed at quantifying the renewable thermal valorization potential of diverse lithium-ion battery technologies.

The relatively low exergy efficiency results from substantial irreversibility within the system. Major exergy destruction originates from Joule heating in the internal resistance of the cell and from electrochemical side reactions that do not contribute to useful work. Additional entropy generation during lithium-ion intercalation-deintercalation, as well as unavoidable thermal dissipation to the surroundings, further reduces the recoverable portion of input energy. These findings are consistent with theoretical predictions for highly resistive and chemically irreversible systems, confirming the predominantly thermal nature of energy conversion under overvoltage conditions.

5. Discussion

The results obtained demonstrate the reliable generation of thermal energy from LiMn2O4 batteries subjected to controlled overvoltage conditions, with maximum surface temperatures observed up to approximately 85 °C in the 10 V surge experiments. The reproducibility of the data, with temperature and current deviations below 3%, supports the consistency of the methodology and reinforces the validity of the applied energy balance and exergy analysis models.

Comparative analysis of the experimental configurations with applied voltages of 5 V and 10 V highlights that while the increase in thermal energy generation is moderate (~50%), the entropy production and exergy destruction nearly double, indicating pronounced irreversible phenomena at higher overvoltages. This behavior aligns with the theoretical framework that associates increased entropy generation with exergy destruction in electrochemical systems.

The presence of minor parasitic electrochemical reactions, such as electrolyte decomposition and gas evolution observed during the tests, contributes to the entropy and exergy changes, although these effects were not quantitatively evaluated in this study. Despite these side reactions, the system remained thermally stable, with safety mechanisms effectively preventing thermal runaway or hazardous events, supporting the practical feasibility of utilizing overvoltage-induced thermal generation.

Moreover, the experiment outcomes confirm that post-use lithium-ion batteries, particularly those based on LiMn2O4 chemistry, retain potential as sources of renewable thermal energy, thus fostering a circular economy approach by valorizing end-of-life cells. The thermodynamic and exergetic models developed here offer a robust analytical tool adaptable to other battery chemistries with parameter adjustments.

Limitations identified include the scale of laboratory testing and assumptions of uniform heat distribution, suggesting further research is necessary on industrial-scale applicability and long-term operational effects. Future studies should also explore optimization of thermal management, integration into energy systems, and deeper quantification of side reactions’ impact.

In conclusion, the present work advances the understanding of lithium-ion battery thermal behavior under controlled overvoltage and establishes a foundation for sustainable thermal energy recovery from secondary batteries, contributing to environmental impact reduction and energy efficiency improvements.

6. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research Works

This study presented a comprehensive thermodynamic and exergetic assessment of LiMn2O4-based lithium-ion batteries subjected to controlled overvoltage conditions using electrical energy from renewable sources. The proposed model enabled the quantification of thermal energy generation, entropy production, exergy destruction, and maximum reversible work, providing a consistent analytical framework validated through experimental data. Two configurations, new (charged) and used (discharged) batteries, were evaluated under 5 V and 10 V electrical surges to examine the influence of overvoltage on the energetic and exergetic performance of the cells.

Doubling the applied voltage from 5 V to 10 V increased the maximum work output by approximately 110%, exergy destruction by 109%, entropy generation by 99%, and the thermal energy generated by 56%. Despite this apparent enhancement, the efficiency of heat conversion decreased at higher voltages, indicating diminishing returns beyond certain limits. During testing, the external temperature of new cells stabilized between 50 °C and 60 °C, while used cells exhibited moderate increases up to 28 °C at 10 V, confirming a reduced capacity for energy conversion after electrochemical degradation.

Within the tested range (3–10 V DC), the batteries exhibited stable heating behavior without signs of thermal runaway, venting, or ignition. Overvoltages beyond this range were not tested and are therefore considered potentially unsafe due to electrolyte decomposition and oxygen evolution. Consequently, the use of LiMn2O4 batteries as thermal generators should remain confined to controlled laboratory studies aimed at understanding irreversible thermodynamic phenomena rather than for practical or industrial implementation.

Exergy efficiency remained low—consistent with the strongly irreversible nature of the process. The relatively low exergy efficiency results from substantial irreversibility within the system. Major exergy destruction originates from Joule heating in the internal resistance of the cell and from electrochemical side reactions that do not contribute to useful work. Additional entropy generation during lithium-ion intercalation–deintercalation, together with unavoidable thermal dissipation to the surroundings, further reduces the recoverable portion of the supplied electrical energy. These results align with theoretical expectations for systems dominated by irreversible heat generation, confirming the predominantly thermal character of the energy conversion under overvoltage conditions.

Although the experimental validation was performed on LiMn2O4-based lithium-ion batteries, the proposed thermodynamic and exergy model is formulated in general terms and can be extended to other electrode chemistries by introducing their specific thermochemical constants. This opens the possibility of using the model as a universal framework for evaluating the thermal valorization potential of diverse secondary battery technologies.

This study does not propose an immediate large-scale reuse of spent batteries as thermal devices, but rather investigates their thermodynamic and exergetic behavior under controlled overvoltage conditions. The analysis reveals clear differences between new and aged LiMn2O4 batteries, providing quantitative insight into irreversible energy conversion mechanisms and their potential integration into future waste heat recovery and energy optimization strategies within sustainable industrial processes.

Author Contributions

J.C.R.-F.: Conceptualization; Data curation; Investigation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Validation; Writing—original draft and Writing—review and editing; Resources; Project administration; Funding acquisition. M.I.Á.F.: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology¸ Project administration; Visualization; Software; Resources. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the project REF.SV-24-GIJÓN-1-03 from the University Institute of Industrial Technology of Asturias (IUTA), financed by the City Council of Gijón, Spain.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| A | ampere |

| BTMS | battery thermal management system |

| C | carbon atom |

| COP | coefficient of performance |

| EVs | electric vehicles |

| HEVs | hybrid electric vehicles |

| Li | lithium |

| Li+ | lithium ion |

| min | minutes |

| Mn | manganese atom |

| O | oxygen atom |

| PCM | phase change materials |

| SDG | sustainable development goal |

| V | volt |

| °C | degrees Celsius |

| e− | electron |

| Nomenclature | |

| c | specific heat of the substance (J kg−1 K−1) |

| cp | heat capacity at constant pressure of the reactant or product (J kg−1 K−1) |

| reagent or product specific enthalpy under the conditions which the reaction occurs (kJ mol−1) | |

| reagent or product specific enthalpy in the reference state, i.e., at 25 °C and 1 atm (kJ mol−1) | |

| specific enthalpy of formation in the reference state, i.e., at 25 °C and 1 atm (kJ mol−1) | |

| I | current intensity (A) |

| k | thermal conductivity coefficient of the battery metallic material (W m−1 K−1) |

| L | length of the battery (m) |

| m | mass of the substance (kg) |

| n | moles count (mol) |

| molar flow rate of product (mol s−1) | |

| number of product moles per mole of total reacting material | |

| number of reagents moles per mole of total reacting material | |

| molar flow rate of reactant (mol s−1) | |

| Q | heat exchanged (J) |

| heat-entering the system (kJ) | |

| heat-leaving the system (kJ) | |

| P | pressure (kPa) |

| Pi | partial pressure (kPa) |

| total pressure of reactants or products mixture (kPa) | |

| R | the universal ideal gas constant (J mol−1 K−1) |

| r1 | inner radius of the cylindrical lithium battery (m) |

| r2 | outer radius of the cylindrical lithium battery (m) |

| S | outer surface area of the battery (m2) |

| S | entropy (kJ K−1) |

| formation entropy at T and P0 (kJ K−1) | |

| T | temperature (K or °C) |

| U | internal energy (kJ) |

| U | overall heat transfer coefficient (W m−2 K−1) |

| reagent or product specific internal energy under the conditions which the reaction occurs (kJ mol−1) | |

| V | electrical current (V) |

| reagent or product specific volume under the conditions which the reaction occurs (m3 mol−1) | |

| W | work (J) |

| work done on the system (kJ) | |

| work the system does on the environment (kJ) | |

| power done on the system (kW) | |

| X | exergy (kJ) |

| mole fraction of each component i, it can be a reactant or a product (mol) | |

| Greek letters | |

| Δ | variation or gradient |

| Σ | sum |

| η | efficiency |

| Subscripts | |

| i | measured inside the battery |

| in | input |

| max | maximum |

| out | output |

| p | products |

| r | reactants |

| rev | reversible |

| s | measured on the battery surface |

| Superscripts | |

| 0 | ambient o surrounding value |

References

- Scrosati, B. History of lithium batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2011, 15, 1623–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Menéndez, D.; Ríos-Fernández, J.C.; Blanco-Marigorta, A.M.; Suárez-López, M.J. Dynamic simulation and exergetic analysis of a solar thermal collector installation. Alex. Eng. J. 2022, 61, 1665–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. RePowerEU: A plan to rapidly reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels and fast forward the green transition. Off. J. Eur. Union. 2022. Available online: https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/repowereu-plan-rapidly-reduce-dependence-russian-fossil-fuels-and-fast-forward-green-transition-2022-05-18_en (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Schlacke, S.; Wentzien, H.; Thierjung, E.M.; Köster, M. Implementing the EU Climate Law via the ‘Fit for 55’ package. Oxf. Open Energy 2022, 1, oiab002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Fernández, J.C.; González-Caballín, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Trashorras, A.J. Effect of the climatic conditions in energy efficiency of Spanish existing dwellings. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2020, 22, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Fernández, J.C. A novel integrated waste energy recovery system (IWERS) by thermal flows: A supermarket sector case. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 19, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Fernández, J.C.; González-Caballín, J.M.; Meana-Fernández, A.; López, M.J.S.; Gutiérrez-Trashorras, A.J. Evaluating European directives impacts on residential buildings’ energy performance: A case study of Spanish detached houses. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 23, 1547–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos Fernández, J.C. Integration capacity of geothermal energy in supermarkets through case analysis. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2019, 34, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2023 Concerning Batteries and Waste Batteries, Amending Directive 2008/98/EC and Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Repealing Directive 2006/66/EC; Official Journal of the European Union; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023; p. L191-1.

- Wu, J.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, D.; Wan, H.; Yao, X. All-solid-state lithium batteries with sulfide electrolytes and oxide cathodes. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2021, 4, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Trócoli, R.; Santos-Peña, J. A LiFePO4-Based Cell with Li x (Mg) as Lithium Storage Negative Electrode. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2009, 12, A145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbek, E.; Yalin, G.; Ekici, S.; Karakoc, T.H. Evaluation of design methodology, limitations, and iterations of a hydrogen fuelled hybrid fuel cell mini UAV. Energy 2020, 213, 118757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozbek, E.; Yalin, G.; Karaoglan, M.U.; Ekici, S.; Colpan, C.O.; Karakoc, T.H. Architecture design and performance analysis of a hybrid hydrogen fuel cell system for unmanned aerial vehicle. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 16453–16464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Yu, Y.; Chen, C. A review on lithium-ion batteries safety issues: Existing problems and possible solutions. Mater. Express 2012, 2, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzen, E.; Kucuk, K.; Aryal, S.; Timofeeva, E.V.; Segre, C.U. Nanoscale MnO2 cathodes for Li-ion batteries: Effect of thermal and mechanical processing. J. Power Sources 2020, 448, 227374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.D.; Bruce, P.G. Mechanism of electrochemical activity in Li2MnO3. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 1984–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dose, W.M.; Sharma, N.; Donne, S.W. Discharge mechanism of the heat treated electrolytic manganese dioxide cathode in a primary Li/MnO2 battery: An in-situ and ex-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction study. J. Power Sources 2014, 258, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, J.M.; Yoon, S.; Kim, S.O.; Sohn, J.S.; Rhee, K.I.; Sohn, H.J. Electrochemical characteristics of manganese oxide/carbon composite as a cathode material for Li/MnO2 secondary batteries. J. Power Sources 2008, 183, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.S. Development and utility of manganese oxides as cathodes in lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2007, 165, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.S.; Mansuetto, M.F.; Thackeray, M.M.; Shao-Horn, Y.; Hackney, S.A. Stabilized alpha-MnO2 electrodes for rechargeable 3 V lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Wu, M.; Liu, X. Dependence of the structures of manganese dioxides on their chemical properties. J. Solid State Chem. 2002, 164, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamrani, B.; Lebrouhi, B.E.; Khattari, Y.; Kousksou, T. A simplified thermal model for a lithium-ion battery pack with phase change material thermal management system. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liang, Z.; Souri, M.; Esfahani, M.N.; Jabbari, M. Numerical analysis of lithium-ion battery thermal management system using phase change material assisted by liquid cooling method. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 183, 122095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bais, A.R.; Subedars, D.G.; Joshi, N.C.; Panchal, S. Numerical investigation on thermal management system for lithium ion battery using phase change material. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Wang, F.; Fang, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z. A hybrid thermal management system for lithium ion batteries combining phase change materials with forced-air cooling. Appl. Energy 2015, 148, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Abidi, I.H.; Tso, C.Y.; Chan, K.C.; Luo, Z.; Chao, C.Y. Thermal management of lithium ion batteries using graphene coated nickel foam saturated with phase change materials. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2018, 124, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jiang, B.; Li, B.; Yan, Y. A critical review of thermal management models and solutions of lithium-ion batteries for the development of pure electric vehicles. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 64, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Luo, L.; Fan, Y.; Du, Z. A review on thermal management of lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles. Energy 2022, 238, 121652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhong, Y.; He, J.; Wu, Y. Development of advanced anodes for solid-state lithium batteries. Mater. Today 2025, 88, 1005–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. Electrolytes and interphases in Li-ion batteries and beyond. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 11503–11618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Song, W.; Son, D.Y.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Lithium-ion batteries: Outlook on present, future, and hybridized technologies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 2942–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.H.P.; Chen, M.; Ogunseitan, O.A. Potential environmental and human health impacts of rechargeable lithium batteries in electronic waste. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5495–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, J. Spent rechargeable lithium batteries in e-waste: Composition and its implications. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2014, 8, 792–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalışır, D.; Ekici, S.; Midilli, A.; Karakoc, T.H. Benchmarking environmental impacts of power groups used in a designed UAV: Hybrid hydrogen fuel cell system versus lithium-polymer battery drive system. Energy 2023, 262, 125543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali-Heidari, E.; Kamyabi-Gol, A.; Heydarzadeh Sohi, M.; Ataie, A. Electrode materials for lithium ion batteries: A review. J. Ultrafine Grained Nanostructured Mater. 2018, 51, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Çengel, Y.A.; Boles, M.A.; Kanoğlu, M. Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach; McGraw-Hill Education: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tosun, İ. The Thermodynamics of Phase and Reaction Equilibria, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koruyucu, E.; Ekici, S.; Karakoc, T.H. Performing thermodynamic analysis by simulating the general characteristics of the two-spool turbojet engine suitable for drone and UAV propulsion. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 145, 1303–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balli, O.; Ekici, S.; Karakoc, H.T. Achieving a more efficient and greener combined heat and power system driven by a micro gas turbine engine: Issues, opportunities, and benefits in the presence of thermodynamic perspective. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 8620–8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.W.; Perry, R.H. Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, 8th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bagcı, S.; Tütüncü, H.M.; Duman, S.; Bulut, E.; Özacar, M.; Srivastava, G.P. Physical properties of the cubic spinel LiMn2O4. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2014, 75, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delhaes, P.; Rouillon, J.C.; Manceau, J.P.; Guerard, D.; Herold, A. Paramagnetism and specific heat of the graphite lamellar compound C6Li. J. Phys. Lett. 1976, 37, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaura, K.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Takada, K.; Baba, Y.; Nagai, T.; Matsui, Y.; Kosuda, K.; Takayama-Muromachi, E. Spinel-to-CaFe2O4-type structural transformation in LiMn2O4 under high pressure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9448–9456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, K.; Souza, F.L.; Freitas, A.L.; Thron, A.; Castro, R.H. Improving thermodynamic stability of nano-LiMn2O4 for Li-ion battery cathode. Chem. Mater. 2021, 33, 3915–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Navrotsky, A. Thermochemistry of Li1+xMn2−xO4 (0≤x≤1/3) spinel. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A.; Tsatsaronis, G.; Moran, M.J. Thermal Design and Optimization; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Çengel, Y.A.; Ghajar, A.J. Heat and Mass Transfer: Fundamentals & Applications, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- DIN EN 10346:2015–10; Continuously Hot-Dip Coated Steel Flat Products for Cold Forming—Technical Delivery Conditions. DIN Media: Cairo Governorate, Egypt, 2015.

- Murashko, K.A.; Pyrhönen, J.; Jokiniemi, J. Determination of the through-plane thermal conductivity and specific heat capacity of a Li-ion cylindrical cell. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 162, 120330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Al Hallaj, S.; Selman, J.R.; Dinwiddie, R.B.; Wang, H. Thermal properties of lithium-ion battery and components. J. Electrochnol. Soc. 1999, 146, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantharaj, R.; Marconnet, A.M. Heat generation and thermal transport in lithium-ion batteries: A scale-bridging perspective. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys. Eng. 2019, 23, 128–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marconnet, A.M.; Kantharaj, R.; Sun, Y. Characterization of Thermal Conductivity and Thermal Transport in Lithium-Ion Batteries; Thermal & Fluids Analysis Workshop; TFSWS 2018; NASA Johnson Space Center: Houston, TX, USA, 2018.

- Bejan, A. Advanced Engineering Thermodynamics, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Williford, R.E.; Viswanathan, V.V.; Zhang, J.G. Effects of entropy changes in anodes and cathodes on the thermal behavior of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2009, 189, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.S.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wan, C.C. Thermal behaviour of nickel/metal hydride batteries during charge and discharge. J. Power Sources 1998, 74, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Cengel, Y.A. Energy, entropy and exergy concepts and their roles in thermal engineering. Entropy 2001, 3, 116–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).