1. Introduction

Despite rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI), language education continues to encounter persistent challenges. These include low student engagement, fragmented and decontextualized instructional practices, and an overreliance on static, textbook-based materials [

1,

2]. Such limitations underscore the need for more dynamic, context-sensitive, and inclusive approaches that not only foster language development but also align with the broader principles of sustainable education and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) [

3]. However, most previous studies have been theoretical or tool-centric, leaving a gap in empirical evidence on AI-supported, sustainability-focused writing instruction in middle school contexts.

One promising solution lies in the integration of AI-driven language learning models that leverage real-world contexts and multimodal inputs to provide personalized and meaningful learning experiences. Research shows that embedding language learning within authentic, everyday settings can enhance learners’ cognitive engagement, vocabulary retention, and grammatical competence [

4,

5]. The current study builds on such findings by examining an AI-supported, multimodal writing intervention that explicitly integrates sustainability themes. However, many current applications of AI in language education remain limited to static content, failing to adapt meaningfully to learners’ immediate environments [

1].

At the same time, the role of multimodality, and the integration of visual, auditory, textual, and kinesthetic elements, has gained increasing attention in language pedagogy for its ability to accommodate diverse learning styles and support deeper conceptual understanding [

6]. When enhanced with AI, multimodal instruction has the potential to become more interactive, adaptive, and socially relevant. Tools such as AI-generated prompts, digital storytelling platforms, and collaborative sustainability-themed writing tasks allow learners to simultaneously develop language proficiency and environmental and social awareness [

2,

7].

Moreover, AI-enhanced language education can foster critical reflection, intercultural communication, and ecological awareness, thus fostering globally relevant perspectives [

8]. By encouraging students to engage with sustainability-oriented topics such as environmental protection, biodiversity, and climate action, AI-generated learning environments can reinforce both linguistic and socio-ecological competencies.

Despite these promising intersections, the implementation of AI-driven, multimodal, and sustainability-focused language instruction in real classroom settings remains under-researched. Most studies in this area have been either theoretical or tool-centric, with limited empirical insight into classroom-based applications that integrate AI, multimodality, and sustainability content holistically.

To address this gap, this study explores how an eight-week, AI-supported English writing intervention centered on themes such as sustainability and ecology can enhance both language learning and environmental awareness among middle school students. By situating instruction in real-world ecological themes and leveraging AI-powered multimodal tools, this study proposes a context-specific, interdisciplinary instructional approach that explores how AI-enhanced multimodal tasks may support sustainability-focused language learning in a middle school setting. Against this backdrop, the present study directly tests an eight-week AI-supported, multimodal writing intervention with middle school learners, addressing the gap in empirical classroom-based research.

Despite these advances, empirical studies examining AI-supported, sustainability-themed writing in middle school EFL contexts remain scarce. This study addresses this gap by implementing an eight-week, AI-supported multimodal writing intervention and analyzing its effects on student engagement, writing attitudes, and sustainability awareness (see

Section 1.5). Based on the introduction and rationale, the study aims to explore the intersection of AI-driven, multimodal-based language learning and sustainability education. The following research questions guide this inquiry:

1. How does the integration of AI-supported multimodal writing tasks affect middle school students’ engagement and writing attitudes in English language education with sustainability themes?

2. In what ways do AI tools enhance students’ awareness and expression of sustainability-related concepts through English writing activities?

1.1. Theoretical Background & Literature

This study is grounded in an interdisciplinary theoretical framework that brings together three core perspectives: Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT), and multimodality in language education. Each of these perspectives contributes unique insights into the design of pedagogical practices that are linguistically enriching, ecologically responsive, and technologically enhanced.

The integration of ESD provides a foundation for embedding sustainability themes into language instruction, emphasizing the development of learners’ environmental awareness, critical thinking, and environmental and social competencies. TBLT, on the other hand, offers a learner-centered approach that supports the use of meaningful, real-world tasks, especially those aligned with sustainability topics to promote communicative competence. Finally, the lens of multimodality supports the design of inclusive and engaging learning environments that incorporate visual, auditory, and interactive digital elements, all of which are further amplified through the use of AI tools.

1.2. Education for Sustainable Language Learning

ESD promotes holistic learning experiences that empower individuals to make informed decisions and take responsible action toward environmental integrity, economic resilience, and social justice [

9]. When applied to language education, ESD offers a transformative pedagogical lens through which learners can engage with complex global issues while cultivating critical awareness, empathy, and a sense of agency [

8]. This perspective reframes English language instruction as more than just the acquisition of linguistic skills, positioning it as a platform for civic engagement and ecological consciousness.

The integration of sustainability competencies such as systems thinking, ethical reflection, and collaboration into language instruction fosters the development of globally responsible citizens [

10]. Language education, as [

11] highlight, can act as a conduit for understanding the interconnectedness of environmental, economic, and social systems. Embedding sustainability themes into English language teaching (ELT) not only enhances linguistic outcomes but also encourages learners to critically engage with real-world sustainability challenges. In this sense, sustainable language learning does not merely transmit knowledge but aims to build durable, transferable learning skills that prepare students to continue learning over a lifetime.

An emerging area within sustainable language education is the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, particularly in support of writing instruction. AI-powered tools such as Canva, Grammarly, QuillBot, and Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer (ChatGPT) provide real-time, personalized feedback on grammar, coherence, vocabulary, and stylistic choices, thereby enhancing learners’ metalinguistic awareness and autonomy [

12]. These platforms also encourage iterative writing practices through features such as paraphrasing, tone adjustments, and content expansion, which are critical for developing both language proficiency and reflective thinking skills.

AI-enhanced environments support learners across the writing process from planning to revision by fostering engagement, self-regulation, and confidence through non-judgmental feedback. When paired with sustainability-themed tasks, these tools cultivate awareness of global challenges while strengthening literacy skills. However, as scholars note, AI alone cannot ensure meaningful learning; sustained motivation, positive attitudes, adequate resources, and human interaction remain essential, alongside both technological and pedagogical innovation [

13,

14].

Despite the growing acknowledgment of sustainability in educational discourse, its integration into English language curricula remains limited. Traditional language classrooms often emphasize grammatical accuracy and standardized assessments at the expense of critical, real-world engagement [

15]. In contrast, education for sustainable language learning calls for a shift toward eco-conscious content, participatory methods, and cross-cultural dialog. As the authors of [

16] argue, integrating ecological themes with cultural awareness supports not only long-term linguistic proficiency but also learners’ identities as global citizens.

Overall, ESD has redefined language learning as a socially and environmentally responsive practice. When combined with AI technologies and multimodal strategies, it offers a powerful foundation for a new generation of English instruction, one that is inclusive, contextual, and committed to building a sustainable future.

1.3. Task-Based Language Teaching in Sustainable Language Learning

TBLT is a communicative approach that emphasizes the use of real-world tasks to promote language development through meaningful interaction and learner autonomy. The task cycle typically involves three stages: a pre-task phase to introduce the topic and relevant language, a task phase where learners collaborate to complete an assignment, and a post-task phase focused on language analysis and reflection, often with teacher feedback [

17]. TBLT integrates multiple language skills and places learners in authentic, problem-solving scenarios aligned with their interests and lived experiences. Building on prior work on communicative and task-based approaches [

18], this study extends these principles by embedding AI-supported, sustainability-themed writing tasks in a real classroom setting.

This approach is particularly well-suited to sustainability education due to its alignment with core principles such as critical thinking, ethical reasoning, and interdisciplinary inquiry [

19]. By designing tasks around sustainability-related themes such as environmental advocacy campaigns, persuasive essays on climate policy, or writing proposals for green initiatives, TBLT enables learners to engage with global issues while developing linguistic competence. These cognitively and ethically rich tasks contribute not only to language proficiency but also to learners’ ecological literacy and civic awareness [

20].

The integration of writing-focused sustainability tasks within a TBLT framework promotes multimodal, affective, and interdisciplinary engagement. For instance, digital storytelling projects, reflective journals, and collaborative reports on environmental topics allow students to process complex sustainability concepts while practicing key writing strategies [

21,

22]. These tasks foster both language accuracy and expressive depth, reinforcing sustained attention, critical engagement, and meaningful application of language. While such multimodal tasks have been theorized extensively [

22], empirical applications in middle school EFL contexts remain limited, and our study directly addresses this gap.

AI-driven technologies further expand the potential of TBLT by enabling personalized task design and immediate feedback mechanisms. Tools such as ChatGPT and automated writing evaluators can generate context-specific prompts, suggest linguistic improvements, and support learners throughout the planning, drafting, and revision stages of writing tasks [

23]. These affordances enhance learner motivation and reduce cognitive load, contributing to deeper understanding of both sustainability content and language use. By situating these AI-driven supports within an eight-week intervention, our research adds concrete classroom evidence to complement the largely tool-centric literature on AI in TBLT.

Empirical research supports the efficacy of sustainability-focused TBLT interventions. For example, ref. [

20] implemented a digital storytelling project addressing environmental issues, reporting greater learner engagement and heightened sustainability awareness. Similar outcomes were observed in studies employing persuasive writing tasks, sustainability-themed debates, and collaborative problem-solving projects [

21]. These studies highlight the value of TBLT as a student-centered and contextually relevant pedagogical model for integrating sustainability into English language education.

Nevertheless, challenges persist. In many educational contexts, traditional grammar-focused approaches continue to dominate, making it difficult to adopt task-based, sustainability-oriented instruction [

16]. Teachers may require professional development, institutional support, and access to multimodal resources to design effective tasks [

2]. Furthermore, students may initially struggle with the interdisciplinary and affective demands of sustainability-focused writing, necessitating carefully planned tasks and differentiated feedback.

In response to these challenges, the integration of AI-enhanced environments has gained attention as a means of promoting learner agency and sustainable educational practices. AI supports decentralized, peer-to-peer collaboration and intelligent feedback systems that align with the participatory spirit of TBLT [

24]. In countries such as Turkey, educational initiatives have begun to merge task-based language instruction with national sustainability goals, incorporating AI tools to enrich learners’ exposure to real-world communication and sustainability themes [

25]. This alignment reflects a growing policy interest in merging digital transformation and sustainability education, and our study contributes classroom-based data to this emerging trend.

1.4. AI and Multimodality in Sustainable Language Education

The convergence of artificial intelligence and multimodal literacy has transformed the landscape of ELT, offering innovative pathways to support both linguistic development and sustainability education. AI tools represent a major advancement in this domain, enabling dynamic, real-time support for learners and educators across a variety of platforms and modalities [

24]. AI has extended the pedagogical possibilities of TBLT by generating adaptive, personalized learning experiences that draw from learners’ real-world contexts. For instance, location-based data can be used to design sustainability-themed writing tasks grounded in learners’ immediate environments, thereby enhancing authenticity, immersion, and contextual relevance [

26]. Building on prior research on multimodality and AI-assisted task-based instruction [

24], this study extends these approaches by empirically testing an eight-week intervention with middle school EFL learners focusing on sustainability themes. AI-powered tools offer instant feedback on structure, coherence, vocabulary, and rhetorical strategies, structuring the entire writing process from planning to revision [

12].

AI tools enhance learner motivation and reduce writing anxiety by creating supportive, non-judgmental spaces for exploration. Conversational agents and AI-enhanced platforms foster engagement and autonomy, enabling sustained writing practice aligned with sustainability goals [

26]. To maximize these benefits, institutions should prioritize critical thinking and ethical awareness rather than restrictive policies [

24]. At the same time, multimodality diversifies engagement through visual, auditory, textual, and interactive media, supporting creativity, inclusivity, and varied learning preferences [

6]. In this study, a structured AI-assisted approach was applied to capture and analyze students’ writing behaviors across multimodal, sustainability-focused tasks. Similarly to how [

27] systematically analyzed large-scale vehicle trajectory data to identify and compare behavioral patterns under different conditions, our study applies a structured, AI-assisted approach to capture and analyze students’ writing behaviors across multimodal, sustainability-themed tasks.

When applied to sustainability-focused and AI-driven ELT writing tasks, multimodal strategies encourage learners to synthesize diverse forms of representation, deepening their understanding of ecological and social justice issues [

20]. For example, students might use infographics to explain the carbon cycle, develop digital narratives about climate change, or create persuasive videos advocating for environmental action [

22]. Such activities develop both linguistic proficiency and sustainability competencies, including systems thinking, ethical reflection, and global citizenship [

19]. While previous studies have largely been exploratory or tool-centered, our intervention situates these multimodal strategies within authentic classroom practice, adding concrete evidence about how students apply them to sustainability-focused writing tasks.

AI-supported platforms foster peer feedback, intercultural dialogue, and collaborative knowledge-building, which are central to sustainability-oriented pedagogy [

28,

29]. Yet, risks such as algorithmic bias, over-reliance, and ethical concerns regarding authorship, privacy, and transparency remain [

12]. To address these, students require critical digital literacy that enables them to assess AI outputs, question systemic bias, and recognize limitations. Such literacy ensures that AI use in ELT extends beyond functional support toward fostering ethical awareness and meaningful ecological engagement [

15].

Emerging research also highlights the need to contextualize AI-driven language instruction within broader technological developments. The decentralized architecture of AI fosters participatory learning, transparency, and peer-to-peer collaboration, values that align with the ethos of sustainability education [

24]. In China and Turkey, for example, national efforts have begun to align digital transformation with sustainability-oriented education policies, promoting AI-supported TBLT models that engage students in authentic communication tasks with environmental themes [

18]. Similar to how [

30] applied denoising schemes and artificial neural networks to extract patterns and improve prediction accuracy from large-scale traffic flow data, our study systematically collected and analyzed student writing data to identify engagement patterns and evaluate AI-assisted interventions.

The integration of AI and multimodality in sustainability education represents a significant pedagogical shift, enabling learners to address complex global issues while building 21st-century skills. Through adaptive technologies, multimodal resources, and sustainability-focused tasks, educators can create inclusive and transformative learning environments that prepare students to become critical and globally engaged citizens. This study contributes to filling the empirical gap on AI-supported EFL writing in classroom contexts.

1.5. Research Gap

While short-term empirical interventions have begun to emerge in the field of sustainability-oriented ELT, several important gaps remain. Although recent studies have explored the pedagogical potential of AI-enhanced and task-based instruction, there is a need for more sustained and diverse investigations that examine the long-term impact of such approaches on learners’ linguistic proficiency and ecological awareness [

20]. The existing literature is still dominated by theoretical frameworks and review insights, indicating a growing demand for classroom-based, experimental methods studies that measure the educational value of AI and multimodal integration over time [

15].

In particular, the intersection of artificial intelligence, multimodality, and sustainability education remains underexplored. While AI-powered tools offer innovative opportunities for personalizing language instruction and supporting eco-literacy, more research is needed to assess their effectiveness in cultivating critical digital literacy, reflective writing skills, and sustainable learning behaviors [

12]. Furthermore, little is known about teachers’ professional development needs when attempting to implement sustainability-oriented, AI-supported language instruction [

2].

From the learner perspective, studies examining user engagement, satisfaction, and reflective outcomes with AI-powered writing tools are also limited. While initial findings point to increased motivation and autonomy, comprehensive abilities of AI tools’ pedagogical, task-based and affective dimensions are still lacking [

31]. Research highlights the importance of understanding learner experiences with AI services in L2 contexts, particularly in relation to writing fluency, metacognitive strategies, and sustainability awareness.

This study contributes to the field in several ways:

1. It empirically examines the underexplored intersection of artificial intelligence, multimodality, and sustainability education in a middle school EFL context, documenting learners’ engagement, satisfaction, and reflective outcomes with AI-powered writing tools.

2. It demonstrates how AI-powered tools can foster language proficiency, eco-literacy, and critical digital literacy simultaneously, addressing gaps in reflective writing skills, sustainable learning behaviors, and extending the literature beyond tool-centric studies.

3. It offers a classroom-based instructional framework of AI-supported multimodal writing tasks aligned with the SDGs, providing a transferable model for future interventions and highlighting implications for teachers’ professional development.

Another under examined area involves the modalities through which learners access AI services, such as text-based interfaces, speech-to-text systems, and visual feedback mechanisms. These modalities impact user experience, learning outcomes, and the level of learner control. Studies that compare how different input/output modes (e.g., mobile, wearable, multimodal platforms) affect learner autonomy, personalization, and writing performance would be highly valuable [

24].

While narrow AI applications such as grammar checkers, machine translation, and automated writing evaluation, continue to support language teachers and learners, the increasing prevalence of general-purpose AI tools capable of generating multimodal content raises pedagogical and ethical concerns [

32]. These systems may potentially replace classical education tools such as; textbooks, pen-and-paper environments, making it crucial to evaluate their pedagogical value, limitations, and implications for sustainability education.

The present study contributes meaningfully to several of the research gaps identified above. Through an eight-week, multimodal-based intervention that integrates AI-supported, sustainability-themed writing tasks, this study offers empirical insight into the short- to mid-term impact of artificial intelligence on both linguistic development and ecological awareness in ELT. By uniting artificial intelligence, multimodality, and sustainability within the context of English writing instruction, the research addresses an underexplored intersection in the field.

Moreover, the study provides practical evidence on how AI-assisted tools can support learners’ engagement with sustainability issues. Furthermore, the intervention generates valuable multimodal-level data that can inform future studies on the sustained effects of AI-enhanced sustainability education. Additionally, the findings illuminate learners’ interaction patterns with generative AI, offering insight into user experience and task performance, areas still relatively scarce in the current literature.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the methodology, including research design, context, participants, intervention, and data collection/analysis procedures.

Section 3 reports the findings derived from the pre- and post-intervention analyses.

Section 4 discusses these findings in relation to research questions and prior literature.

Section 5 provides the conclusions and practical implications, while

Section 6 outlines the study’s limitations and future research directions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a qualitative case study design to explore how AI-supported writing instruction contributes to sustainable language education among young English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners. A case study approach was deemed appropriate due to its capacity to provide a holistic and context-sensitive understanding of multimodal dynamics, particularly students’ engagement with AI tools and sustainability-themed content [

33].

The research was, mostly, conducted in a naturalistic educational setting, a public middle school in Turkey, where the researcher also served as the classroom instructor/observer. The instructional intervention was implemented over the course of eight weeks with a single intact class of 42 seventh-grade students (4 of them were included into the research). English writing lessons were delivered once a week as a complementary part of the school’s existing curriculum.

Aligned with the principles of situated learning and ESD, the instructional design focused on authentic, socially relevant topics and task-based writing practices. Students used generative AI tools for planning, drafting, and revising, while multimodal elements (visuals, prompts, AI feedback) simulated real-world communication and fostered engagement with sustainability themes. Two sessions also included outdoor observations of local environmental issues to inform writing tasks.

The case study design integrated multiple data sources, including pre- and post-intervention reflections and classroom observations, providing insights into how learners engaged with AI-supported writing and sustainability themes. This design responds to calls for ecologically valid research that explores the links between language education, AI, and global sustainability goals.

2.2. Context and the Participants

This study was conducted at a public middle school located in the northern region of Turkey. The school is recognized for its pioneering role in integrating sustainability principles into both academic instruction and institutional practices. Notably, it is one of the first schools in the region to systematically align the SDG with its curriculum across all grade levels. The school is also well known for its strong environmental education policies and green campus initiatives, including energy-saving practices, waste reduction programs, and community-driven sustainability projects (see

Figure 1).

The school’s commitment to sustainability and digital literacy was reflected not only in its formal curriculum but also in its rich portfolio of extracurricular and project-based learning activities.

The participants in this study consisted of 42 seventh-grade students enrolled in a single English writing class. Over the course of eight weeks, English writing instruction was delivered once a week by the researchers, who also acted as the primary classroom observer. The aim of the course was to enhance students’ English writing skills while simultaneously promoting awareness of sustainability task-based themes through AI-supported and multimodal activities.

For the in-depth case study analysis, 4 focal students were purposefully selected to reflect a diverse range of classroom engagement levels. The selection strategy followed the principles of maximum variation sampling [

34], ensuring representation across high, moderate, and low participation profiles. This approach allowed the researcher to capture a broad spectrum of learner experiences and behavior patterns within the AI-mediated writing environment.

Additional selection criteria included students’ willingness to participate in follow-up interviews and their consistent attendance throughout the intervention period. The selected students also varied in their levels of digital literacy, English language performance, and responsiveness to AI-generated prompts. By taking into account both behavioral and contextual dimensions, the sampling strategy aimed to enhance the transferability of findings while ensuring depth and richness in the data collected.

As all participants were current students enrolled in a public school during the time of data collection, pseudonyms were used to protect their identities. All personally identifiable information, including student names, class numbers, and school-specific details, was anonymized or omitted in accordance with ethical research standards and institutional review board protocols.

Table 1 presents anonymized demographic and engagement-level characteristics of the 4 focal participants selected for detailed analysis.

2.3. Intervention

The intervention was designed as an 8-week instructional program aimed at integrating AI tools into multimodal English writing instruction with a strong focus on sustainability education (

Table 2). We used ChatGPT (version 4o, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA), Grammarly (version 1.0, Grammarly Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), QuillBot (version 2.1, QuillBot, Chicago, IL, USA), and Canva (version 4.0, Canva Pty Ltd., Sydney, Australia) throughout Weeks 1–8. Students were instructed to use these tools for planning, vocabulary support, and revision only. Direct generation of full texts by AI tools was explicitly prohibited. All AI interactions were supervised and logged to ensure reproducibility. To protect minors’ data and comply with platform terms of service, all sessions took place in the school’s supervised computer lab. Students used school devices without personal logins; no identifiable information was entered into AI tools. Parental consent and institutional approval were obtained before data collection. Before the intervention began, students received a short orientation session outlining acceptable and prohibited uses of AI tools. They were informed that AI tools should be used only for idea generation, vocabulary support, organization, and revision, not for generating full texts. Participation in data collection was entirely voluntary and did not affect students’ access to instruction; all students attended the same lessons, but only the data of those who provided consent were included in the analysis.

Rooted in TBLT and AI writing tools pedagogy, the program provided middle school students with opportunities to engage in real-world communicative tasks while exploring sustainability-related themes aligned with the SDG. Each weekly session lasted approximately 40–45 min and incorporated AI tools such as ChatGPT, Grammarly, QuillBot, and Canva to support various stages of the writing process, including planning, drafting, revising, and organizing. The intervention also emphasized multimodal learning by incorporating visual, textual, and auditory materials to stimulate engagement and support diverse learning styles. Notably, during Weeks 7 and 8, students participated in outdoor environmental observation activities to foster direct, experiential learning beyond the classroom. This intervention aimed not only to enhance students’ English writing skills but also to promote their critical awareness of global challenges and their ability to communicate solutions through writing.

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. Student Reflections via Semi-Structured Questions

The primary data source for this study consisted of students’ written responses to a set of semi-structured reflection questions (

Appendix A), administered both before and after the instructional period. These reflections were designed to elicit insights into students’ experiences and interaction with AI-supported English writing tasks [

33]. The questions invited students to articulate their personal perceptions of writing in English, their feelings about sustainability-themed topics, and the factors that either supported or hindered their writing processes.

The pre-intervention reflections served to establish a baseline understanding of students’ attitudes toward English writing and their anticipated challenges, particularly in relation to unfamiliar subject matter such as environmental or sustainability issues. In contrast, the post-intervention reflections aimed to explore perceived changes in writing confidence, topic engagement, and the use of AI tools. Students were provided with adequate time to respond and were assured that their answers would not be judged as right or wrong.

2.4.2. Classroom Observations

Classroom observation constituted the second major data source, offering rich contextual information about student participation, behavior, and multimodal dynamics during the eight-week instructional period. The researchers conducted naturalistic, non-participant observations while simultaneously serving as the classroom instructor. Each weekly writing lesson lasted approximately 40–45 min and centered around sustainability task-based writings with multimodality involving AI tools.

The researcher employed both wide-angle and focused observation strategies. From a broader perspective, the focus was on overall classroom engagement (2 weeks outdoor activities), student–AI collaboration, and how AI tools were integrated into group and individual writing activities. From a narrower lens, special attention was given to the four focal students, observing how they interacted with AI-generated prompts, responded to feedback, and approached the writing process during each session.

Observation notes were documented immediately after each session and included descriptions of student behavior, illustrative quotations, interaction with AI tools, and classroom arrangements. Particular attention was paid to students’ affective responses, collaborative efforts, and moments of struggle or success. These detailed field notes provided contextual depth that supported the interpretation of the written responses/reflections.

2.5. Qualitative Data Analysis

A general inductive approach was employed to analyze the qualitative data collected through student reflections and classroom observations [

35]. This method was selected for its capacity to distill large volumes of raw textual data into meaningful themes and subthemes that align with the study’s core constructs.

All qualitative data, including semi-structured student responses and observation field notes, were uploaded to MAXQDA 2020, a software program designed for qualitative data organization and analysis. The coding process was conducted collaboratively with two field experts (

Appendixe B,

Appendix C and

Appendix D), one in language education and the other in educational psychology, to ensure interrater reliability, consistency, and intersubjective agreement throughout the analysis.

The thematic analysis unfolded in two primary stages:

This phase focused on identifying students’ initial perceptions of English writing, familiarity with AI tools, and conceptual understanding of sustainability-related issues. Themes were derived both from students’ reflections and classroom observation notes. Codes were generated inductively and organized into three major themes, each comprising two to four subthemes that reflected shared patterns of meaning across student responses and classroom behavior (

Table 3).

The second stage centered on students’ reflections and observational evidence following the eight-week instructional intervention. Analysis focused on tracing changes in learner engagement with sustainability content, AI-supported writing practices, and global awareness. The same thematic structure from Stage 1 was retained to allow for comparison and identification of developmental patterns or conceptual shifts (see

Table 4).

3. Findings and Interpretation of the Case Study

3.1. Pre-Intervention Findings

To gain a baseline understanding of students’ initial perceptions, attitudes, and practices related to English writing, AI and sustainability, thematic analysis was conducted on data collected through pre-intervention reflection responses and classroom observations. Also, pre- and post-intervention writing samples of all students (number = 42) were blindly assessed by two independent raters using the CEFR [

36] based writing rubric (

Appendix E). Interrater reliability was found to be acceptable (ICC = 0.84), indicating strong agreement.

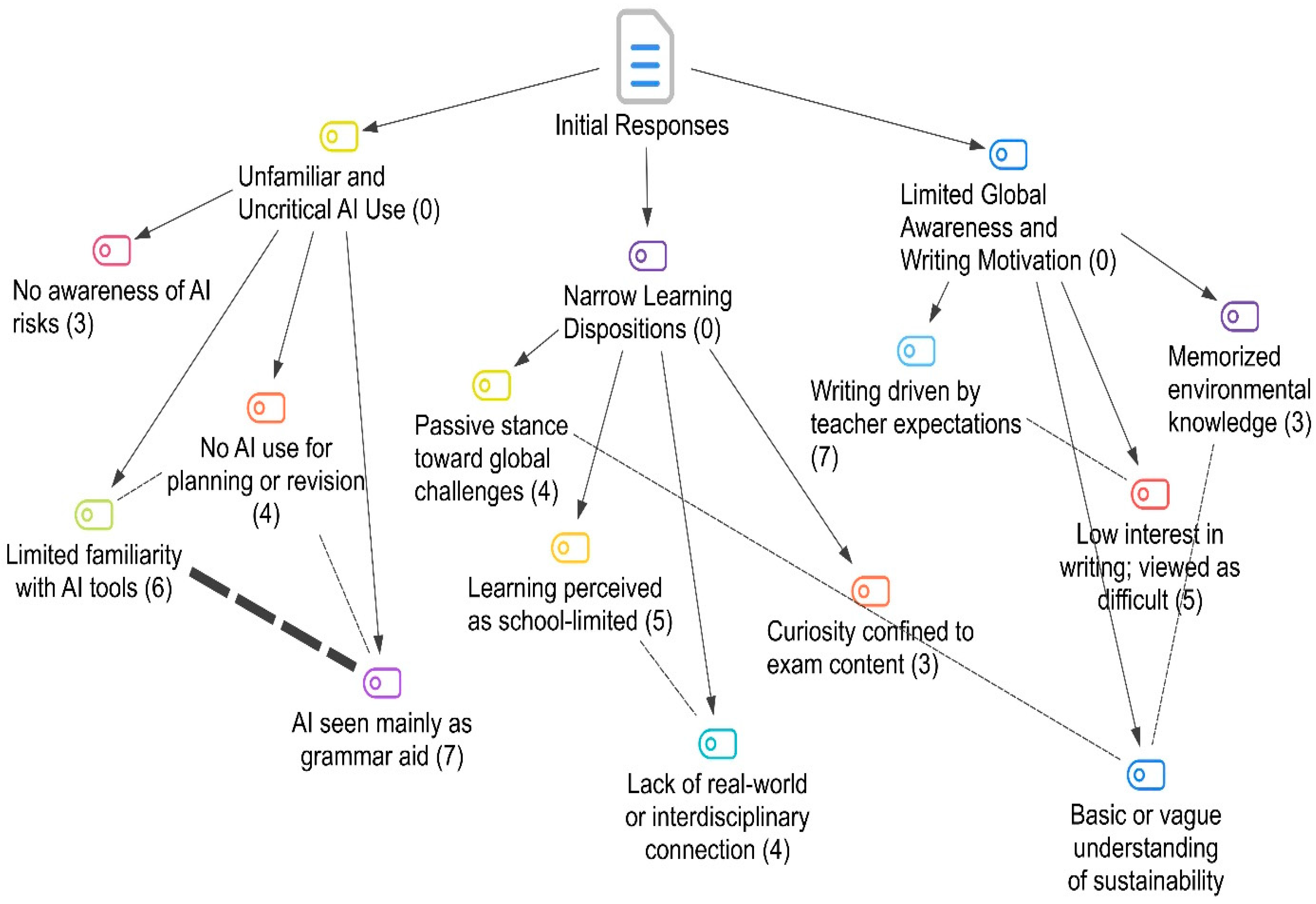

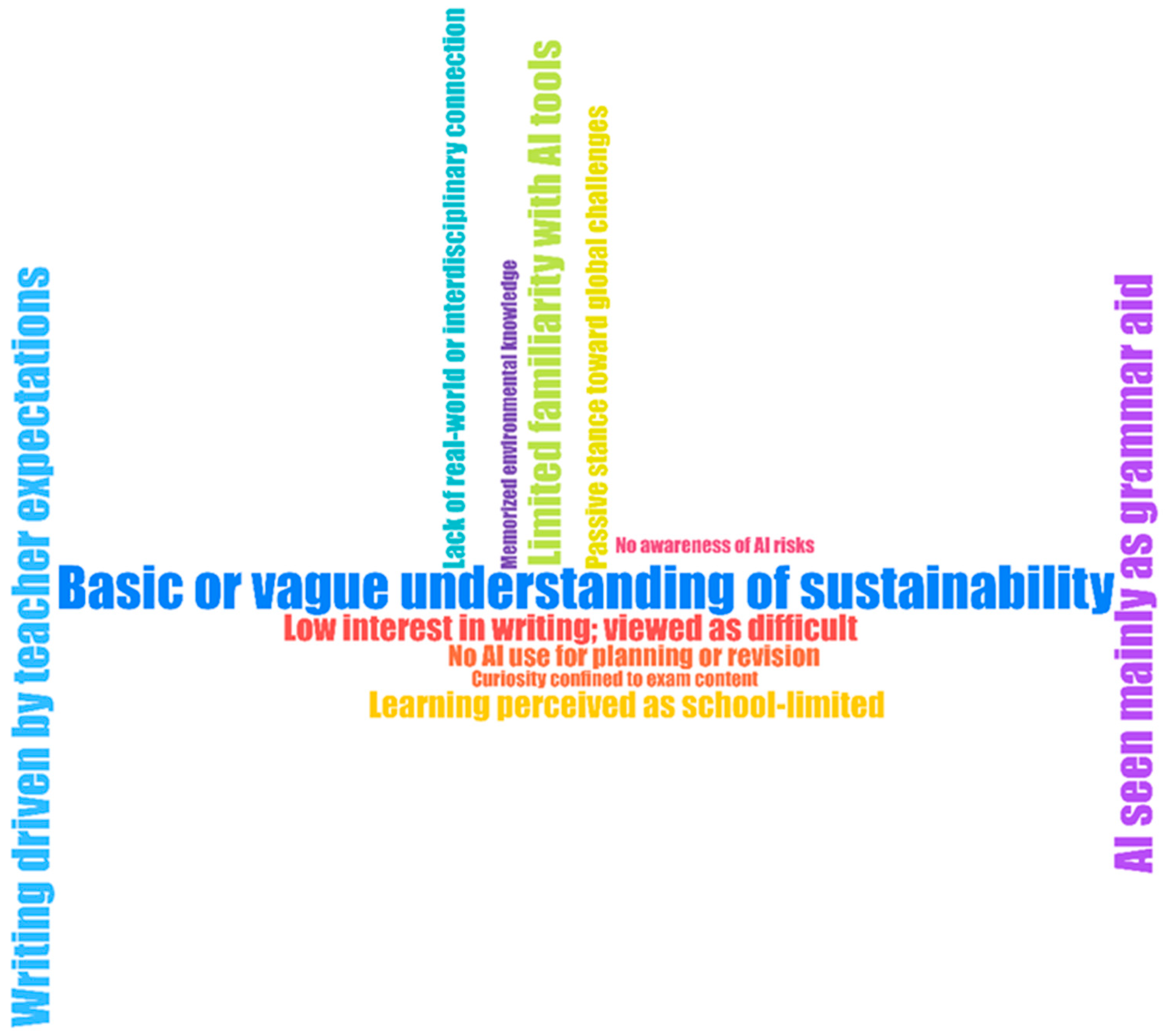

The findings revealed three major themes; Limited Global Awareness and Writing Motivation, Narrow Learning Dispositions, and Unfamiliar and Uncritical AI Use, each consisting of multiple subthemes that reflect common patterns in students’ experiences and beliefs prior to the instructional intervention.

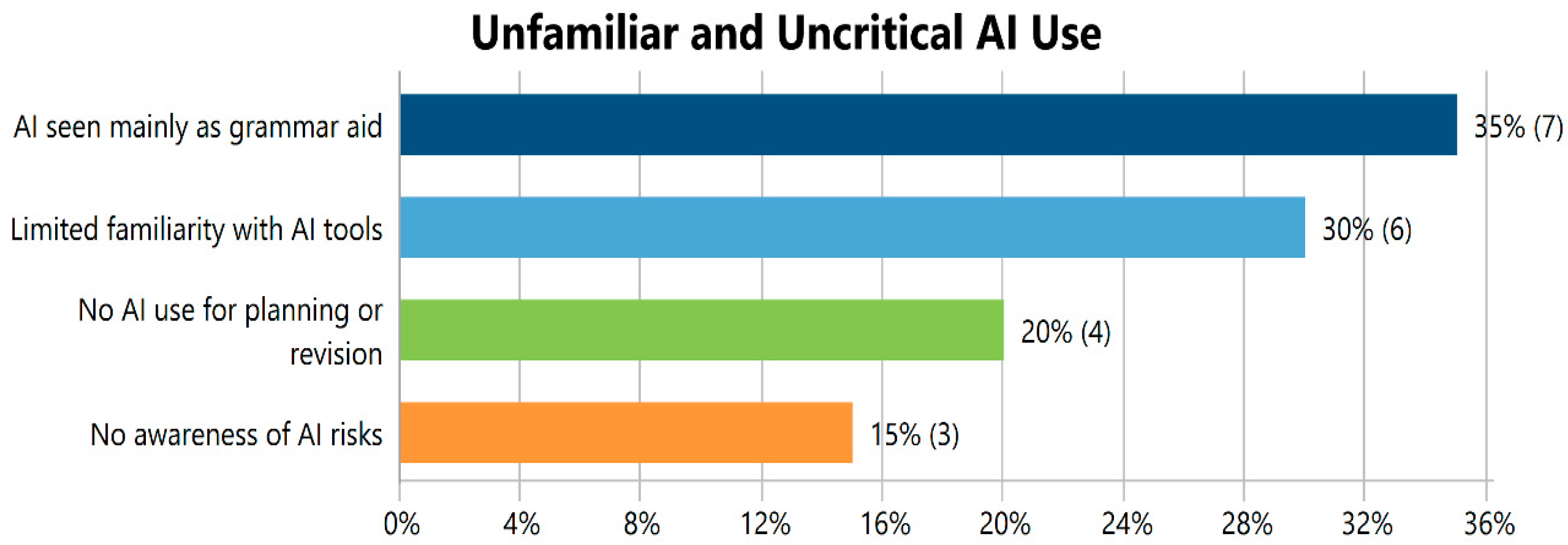

Figure 2 illustrates the frequency distribution of subthemes under the main theme Unfamiliar and Uncritical AI Use as derived from the pre-intervention open-ended responses.

The most frequently occurring subtheme was AI seen mainly as grammar aid (35%, number = 7), indicating that most students associated AI tools with simple corrective functions such as fixing spelling or grammar errors. This suggests a limited understanding of the broader potential of AI in writing, such as planning, idea generation, or content development. The second most cited subtheme was Limited familiarity with AI tools (30%, number = 6), reflecting that many students had little to no prior experience using AI technologies in their writing process. Additionally, 20% of the participants (number = 4) reported that they had never used AI for planning or revising their texts, which further reinforces the minimal integration of these tools in their writing routines. Finally, No awareness of AI risks was the least mentioned subtheme (15%, number = 3), highlighting a general lack of critical reflection on the limitations, inaccuracies, or ethical concerns associated with relying on AI for educational tasks. Overall, these findings demonstrate that prior to the intervention, students’ perceptions and use of AI were primarily superficial, focused on mechanical correction rather than strategic writing support or critical evaluation of AI outputs.

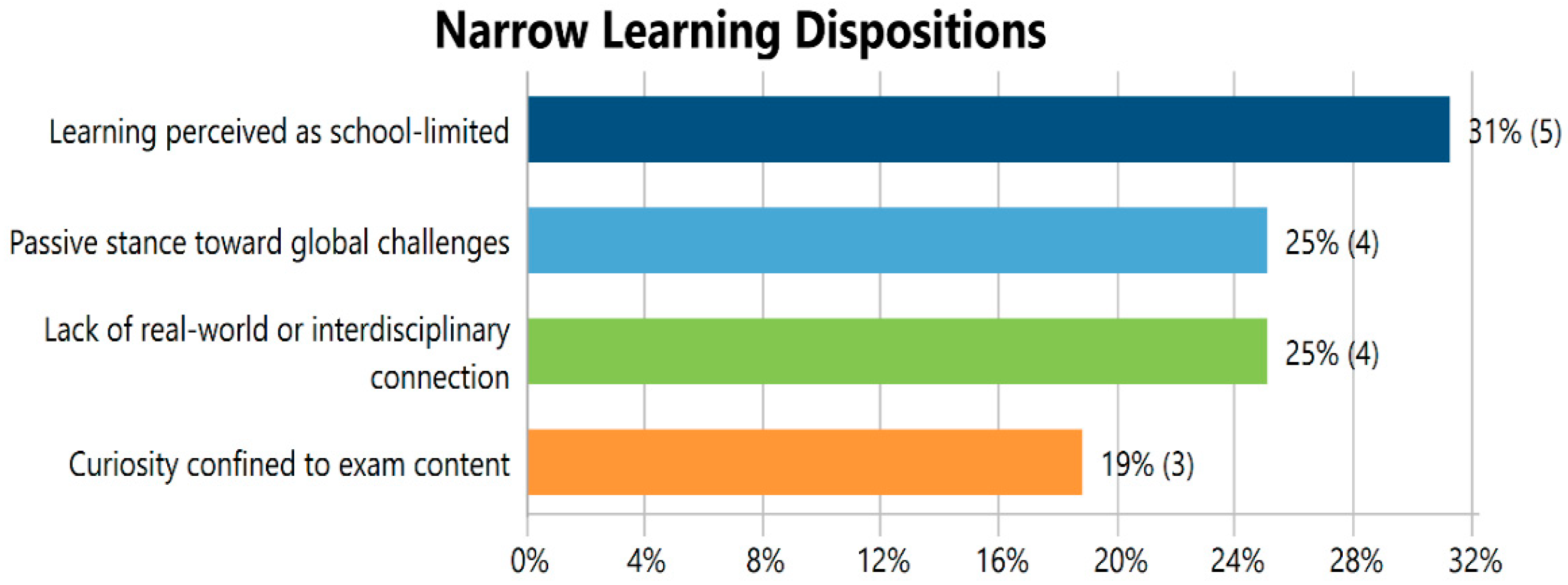

Figure 3 presents the distribution of subthemes under the theme Narrow Learning Dispositions, based on pre-intervention responses.

Among the focal group, the most prominent subtheme was Learning perceived as school-limited (31%, number = 5), revealing that students viewed learning as something confined to school hours or activities directly tied to classroom tasks. This perception reflects a limited understanding of learning as a lifelong and self-directed process. Both Passive stance toward global challenges and Lack of real-world or interdisciplinary connection were cited by 25% of participants (number = 4 each), indicating a disconnection between their classroom experiences and broader global or societal issues. These students tended to perceive subjects like English as isolated from real-world concerns such as climate change, inequality, or civic engagement. Finally, the subtheme Curiosity confined to exam content (19%, number = 3) further emphasizes the exam-oriented mindset, with students showing little motivation to explore knowledge beyond what is directly assessed.

In the network visualization, the interconnections among subthemes especially between Learning perceived as school-limited and both Lack of real-world connection and Passive stance toward global challenges, underscore how a restricted view of learning is closely tied to limited global awareness and engagement. These patterns suggest that prior to the intervention, students had not yet developed the habits of critical inquiry, interdisciplinary thinking, or long-term intellectual curiosity essential for ESD.

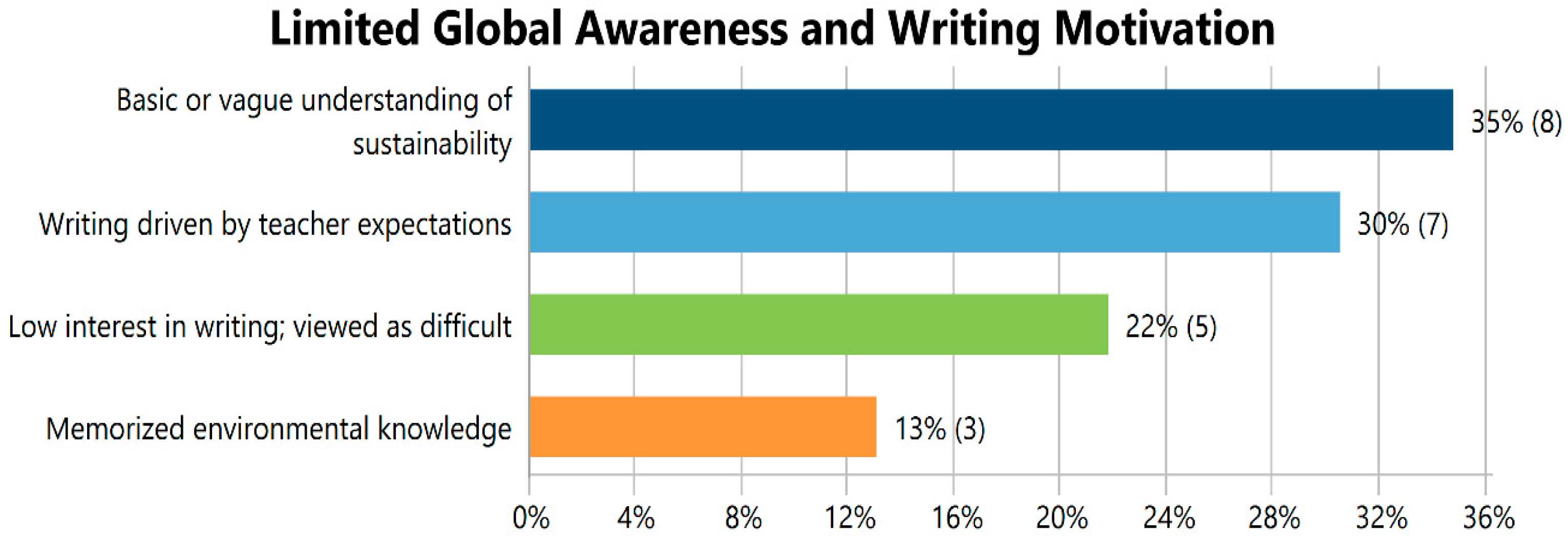

Figure 4 illustrates the frequency distribution of subthemes under the theme Limited Global Awareness and Writing Motivation based on participants’ responses prior to the intervention.

The most frequently mentioned subtheme was Basic or vague understanding of sustainability (35%, number = 8), indicating that students had only a superficial grasp of sustainability-related concepts. Their responses often reflected fragmented or textbook-based recall of environmental issues without deeper critical engagement. The second most common subtheme was Writing driven by teacher expectations (30%, number = 7), revealing a pattern in which students approached writing as a task to satisfy external requirements rather than a tool for personal or societal expression. This aligns with the finding that Low interest in writing; viewed as difficult was reported by 22% of participants (number = 5), many of whom described writing as burdensome, uninspiring, or anxiety-inducing. Lastly, Memorized environmental knowledge (13%, number = 3) reflects the students’ tendency to recall isolated facts or definitions without being able to relate them to current events, real-world challenges, or personal relevance.

The code relation map (

Figure 5) suggests strong overlaps between Writing driven by teacher expectations and Low interest in writing, suggesting that students’ lack of intrinsic motivation may stem from a perception of writing as a purely academic obligation. Similarly, Basic understanding of sustainability is linked to Memorized environmental knowledge, indicating a shallow engagement with global issues. Overall, these findings portray a learner profile that is largely disconnected from global contexts, lacking both awareness and motivation to use writing as a tool for critical reflection or social action.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 presents a visual representation of the relationships among the subthemes derived from students’ pre-intervention responses. This code co-occurrence map illustrates how frequently different subthemes appeared together within the same student reflections or observational excerpts.

The nodes (colored boxes) represent individual subthemes, while the connecting lines (edges) indicate the strength of co-occurrence between subthemes. The thickness of each line reflects the frequency of co-occurrence. Thicker lines indicate stronger or more frequent co-occurrences between two subthemes and thinner lines suggest weaker or less frequent connections. For example, the strongest co-occurrence is observed between Limited familiarity with AI tools and AI seen mainly as grammar aid, connected by a thick dashed line, suggesting that students who had limited exposure to AI also tended to perceive it narrowly as a grammar correction tool. This association reflects a pattern of superficial engagement with AI, focused on mechanical aspects of writing rather than strategic or creative support. Another notable co-occurrence is between Learning perceived as school-limited and two other subthemes as Lack of real-world or interdisciplinary connection and Passive stance toward global challenges. These connections, represented by moderate lines, highlight how students’ compartmentalized view of learning was closely tied to their disengagement with global or cross-disciplinary issues.

On the right side of the map, Writing driven by teacher expectations and Low interest in writing are also connected, indicating that students who viewed writing as a task imposed by the teacher often expressed low intrinsic motivation toward writing in general. This pairing suggests a performance-oriented mindset rather than one driven by self-expression or real-world relevance. Finally, Basic or vague understanding of sustainability is linked to Memorized environmental knowledge, illustrating how limited conceptual understanding often coincided with recall of decontextualized or rote-learned information, rather than critical engagement with sustainability themes.

Together, the structure of this network reveals clusters of conceptually related subthemes, shedding light on students’ initial perceptions before the intervention. The patterns point to a general lack of integration between writing, global awareness, and critical technology use, highlighting the need for pedagogical approaches that foster deeper connections among these domains.

3.2. Post-Intervention Findings

Following the eight-week AI-supported instructional intervention, students demonstrated notable shifts in their perceptions, writing behaviors, and engagement with sustainability-oriented content. The post-intervention data, drawn from written reflections and classroom observations, revealed notable awareness of global issues, more strategic use of AI tools during the writing process, and greater motivation to express personal and societal concerns through English writing. Compared to the pre-intervention findings, the emerging themes suggest a transition from passive and superficial engagement to more purposeful, reflective, and globally aware learning dispositions. The findings presented below are organized according to three overarching themes, each supported by relevant subthemes and visualized through frequency distributions and co-occurrence maps.

Figure 7 presents the frequency distribution of subthemes under the theme Strategic and Reflective AI Use, which emerged from participants’ post-intervention responses. The most frequently mentioned subtheme was Perceived improvement in writing quality (37%, number = 7). Participants reported that using AI tools such as ChatGPT and Grammarly helped them structure their ideas more clearly, expand vocabulary, and correct grammar, leading to higher confidence in their written output. Closely following this, both Awareness of AI’s limitations and risks and Using AI for planning, revising, organizing were cited by 32% of students (number = 6 each). These findings suggest a shift from superficial tool use to a more strategic engagement with AI throughout the writing process.

Students reflected critically on their interactions with AI, acknowledging its usefulness while also recognizing its limitations such as occasional factual inaccuracies or overdependence. This demonstrates an emerging metacognitive awareness in how they evaluate and integrate AI assistance. Furthermore, the stronger use of AI for planning, organizing, and revising indicates that learners moved beyond grammar-checking to using these tools for higher-order writing processes. Overall, this theme highlights the development of agency, self-regulation, and reflective thinking, marking a pedagogical gain achieved through the intervention.

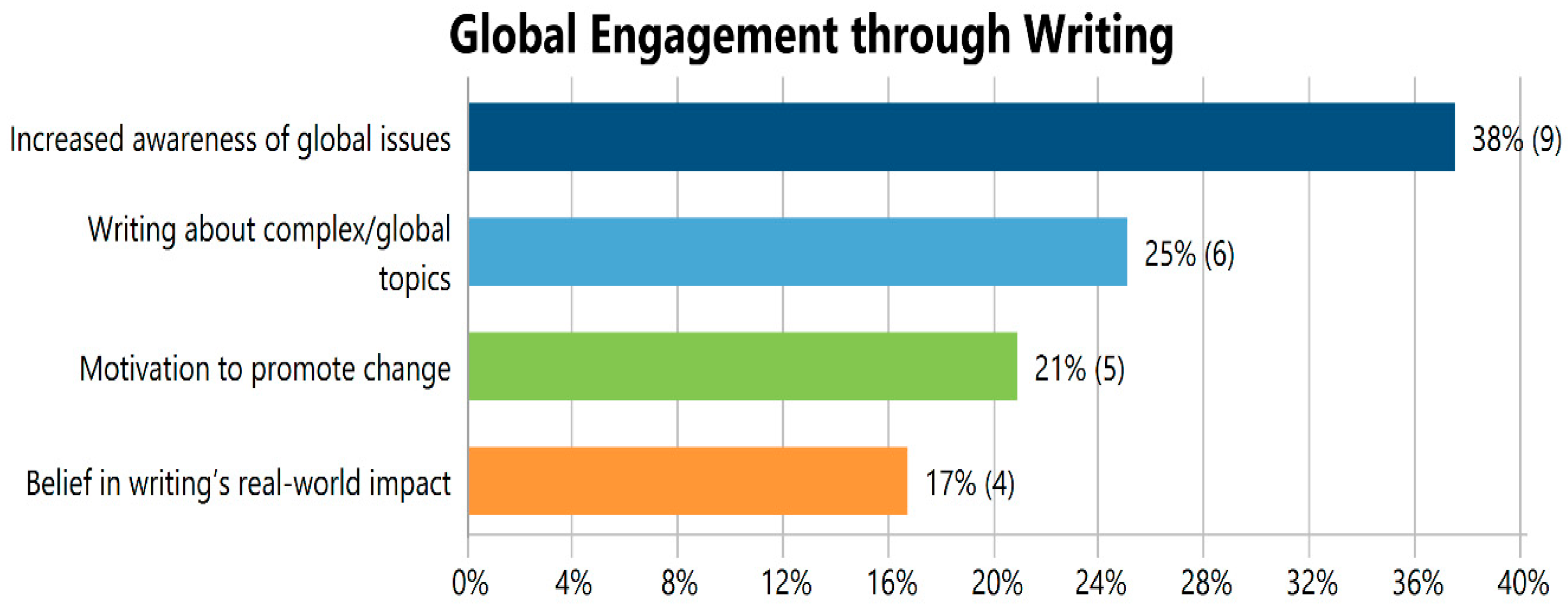

Figure 8 illustrates the distribution of participants’ post-intervention reflections under the theme Global Engagement through Writing. Among the focal group, the most prominent subtheme was Increased awareness of global issues (38%, number = 9), highlighting that students became more conscious of pressing topics such as climate change, poverty, and equality after engaging with sustainability-related writing tasks. This awareness suggests that integrating real-world content into the writing curriculum can foster global consciousness even among middle school learners.

Following this, 25% of participants (number = 6) expressed a newfound ability to write about complex/global topics, noting that they could now discuss topics beyond their immediate lives and school content. The subtheme Motivation to promote change (21%, number = 5) reflects a shift in mindset, as several students articulated a desire to use their writing to raise awareness, express personal concerns, or advocate for environmental and social justice. Lastly, Belief in writing’s real-world impact (17%, number = 4) emerged as a meaningful though less frequently stated insight, demonstrating that some participants started to see writing not just as a school activity but as a tool for influencing others and making a difference.

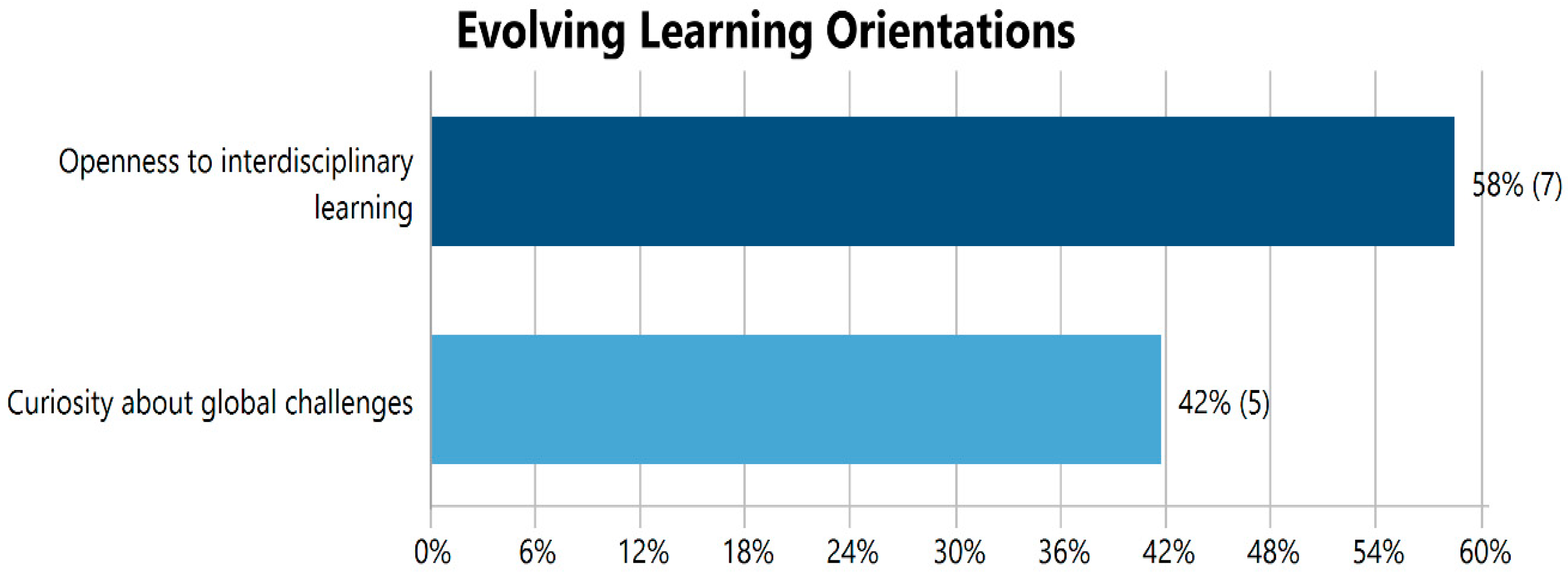

Figure 9 presents the distribution of student responses under the theme Evolving Learning Orientations following the intervention. The most frequently observed subtheme was Openness to interdisciplinary learning (58%, number = 7), suggesting that students notably recognized the value of integrating knowledge across subject areas. Many participants reported that they enjoyed combining English with science, social studies, and sustainability-related topics, indicating a shift away from seeing language learning as an isolated skill. This openness also reflects an emerging readiness to engage with complex content in a more holistic and meaningful way.

The second subtheme, Curiosity about global challenges (42%, number = 5), illustrates students’ growing interest in real-world problems such as environmental degradation, economic inequality, and technological change. Responses under this category highlighted how writing activities that included AI-supported exploration of global topics helped spark questions, personal reflection, and a desire to learn more beyond textbook boundaries.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention contributed to a broader and more future-oriented learning mindset, where students started to view English not only as a school subject but as a gateway to understanding and responding to the world around them.

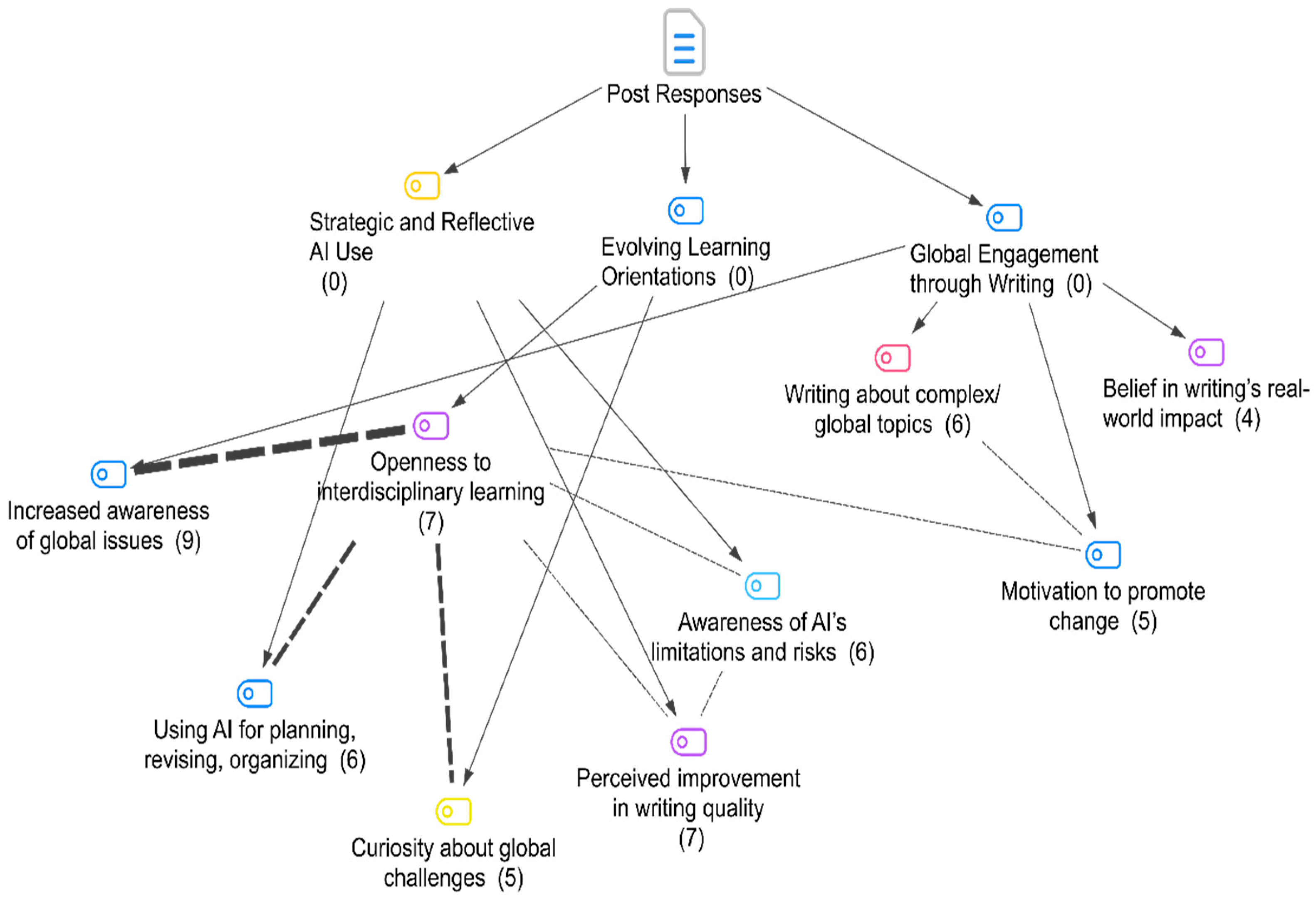

The post-intervention code co-occurrence network map (

Figure 10) and code cloud (

Figure 11) reveal important interconnections between the three major themes Strategic and Reflective AI Use Evolving Learning Orientations and Global Engagement through Writing. The most prominent overlap appears between increased awareness of global issues and multiple subthemes across all three categories. This subtheme co-occurs strongly with openness to interdisciplinary learning and using AI for planning revising organizing suggesting that students who became more globally aware also embraced interdisciplinary thinking and strategic use of AI tools. Similarly openness to interdisciplinary learning shares connections with curiosity about global challenges and perceived improvement in writing quality indicating that engaging with diverse content encouraged students to apply AI support effectively and develop interest in complex global topics. The link between awareness of AIs limitations and risks and writing about complex global topics suggests that students developed a balanced and critical perspective using AI not just for automation but for thoughtful engagement with social issues.

Overall the map demonstrates that the intervention fostered a multidimensional growth in learners where writing global awareness curiosity and strategic AI use were mutually reinforcing. These interconnections reflect a transformation from fragmented task-driven learning to integrated reflective and globally oriented engagement.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the effects of AI-supported multimodal writing tasks on students’ engagement, writing attitudes, and sustainability awareness in English language learning. Integrating AI tools into multimodal writing instruction enhanced students’ motivation and confidence, particularly when tasks were situated in real-world, sustainability-oriented contexts. Students who initially viewed writing as teacher-driven and difficult began to express more autonomy and purpose in their writing. AI tools helped them plan, revise, and structure their ideas, reducing anxiety and fostering self-regulation. The multimodal nature of the tasks, combining visuals, environmental observations, and digital feedback, further enriched their engagement with complex issues such as climate change and inequality. While AI tools supported strategic thinking, some students relied heavily on automated suggestions. This finding underscores the importance of embedding critical AI literacy to help learners evaluate AI outputs and use them responsibly and ethically.

Overall, the study contributes to the underexplored intersection of AI, multimodality, and sustainability in L2 writing by offering classroom-based evidence of how these elements can work together. Beyond its empirical insights, the study provides practical implications for teachers and curriculum designers: it demonstrates how AI-supported multimodal writing tasks can be integrated to foster both linguistic development and sustainability competencies, and it highlights key considerations for supporting student autonomy, scaffolding critical AI literacy, and designing tasks that bridge classroom learning with real-world contexts.