The Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality in Chinese Cities—Based on the Government Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

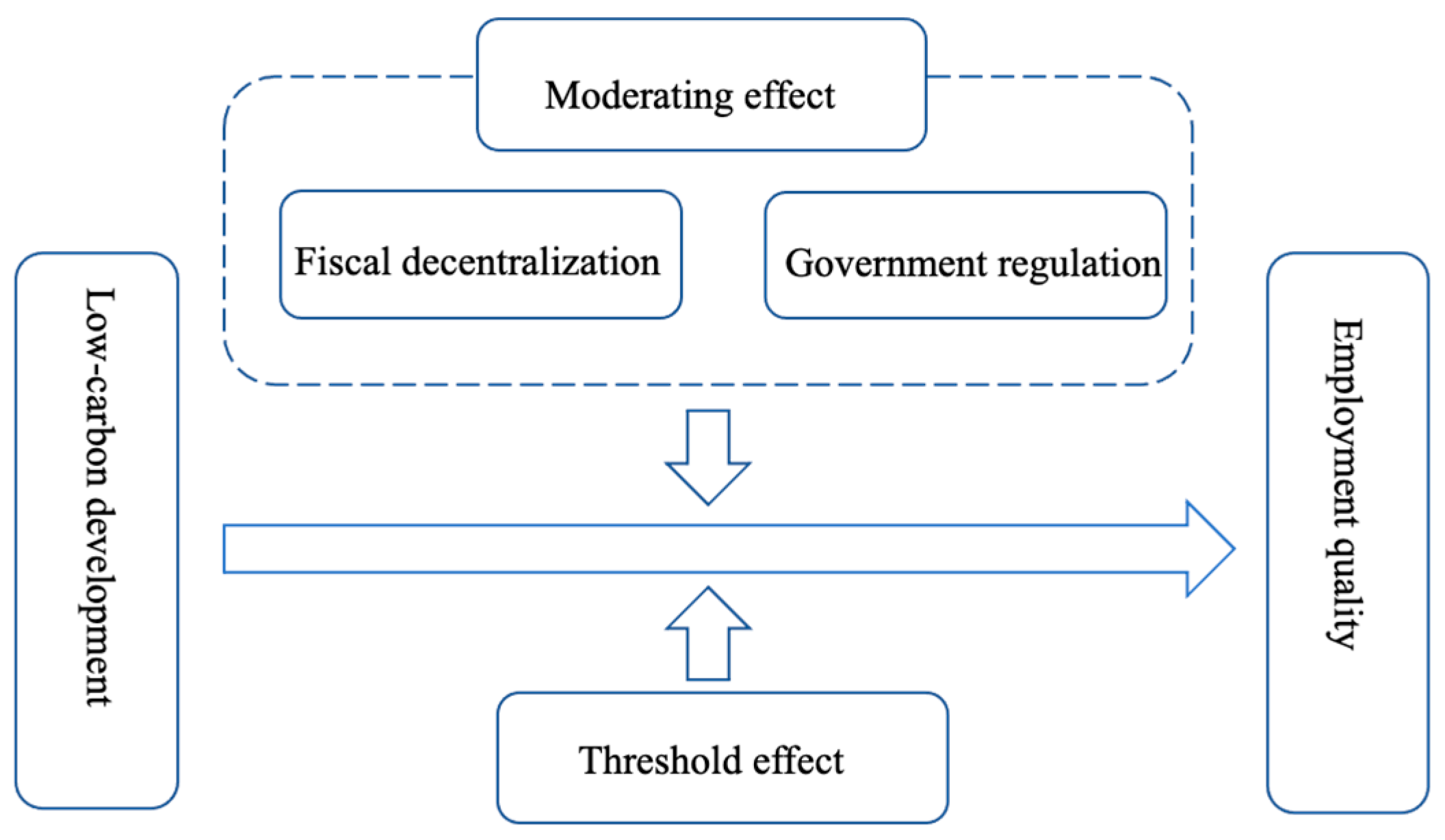

2. Theoretical Mechanism

2.1. Analysis of the Mechanism of Fiscal Decentralization

2.2. Analysis of the Mechanism of Government Regulation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Employment Quality

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable: Low-Carbon Development

3.2.3. Moderating and Threshold Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Model Setting

3.3.1. Moderating Effect Model

3.3.2. Panel Threshold Effect Model

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality

4.1.1. Government’s Moderating Effect on Employment Quality

- (1)

- There is a negative interaction between low-carbon development and fiscal decentralization, with a coefficient of −0.146, significant at the 5% level. This result indicates that fiscal decentralization, to some extent, weakens the positive effect of low-carbon development on employment quality. The underlying reason may be that, although fiscal decentralization grants local governments greater autonomy in resource allocation, it can also lead to unbalanced resource distribution or deviation from the goals of low-carbon development. Local governments, driven by short-term economic growth considerations, may allocate more resources to traditional high-energy-consuming and high-pollution industries, while neglecting the long-term development potential of low-carbon industries and employment promotion initiatives. This “race to the bottom” phenomenon results in resource misallocation, which not only slows the creation of high-quality jobs in the low-carbon sector but also exacerbates structural contradictions in the labor market, thereby weakening the overall positive impact of low-carbon development on employment quality.

- (2)

- There is a significant positive interaction effect between low-carbon development and government regulation, with a coefficient of 0.002, significant at the 1% level. This finding indicates that the government, through the implementation of strict and effective environmental regulatory policies, has not only successfully driven the green transformation of industrial structures but also significantly promoted the improvement of employment quality. Environmental regulation policies, by setting clear environmental standards and emission limits, have reduced corporate pollutant emissions and improved resource utilization efficiency. In this process, the green transformation of traditional industries has created new employment opportunities, while a range of emerging industries centered around green and low-carbon development have also emerged. These industries often require highly skilled and highly qualified labor, thereby boosting overall employment quality. Moreover, government regulation has guided the flow of social capital into the low-carbon sector, promoting the prosperity and development of the green job market.

- (3)

- Further analysis was conducted on the moderating effects of fiscal decentralization and government regulation in low-carbon pilot cities, as shown in columns (3) and (4) of Table 1. The results indicate that fiscal decentralization in low-carbon pilot cities enhances the impact of low-carbon development on employment quality, and government regulation likewise strengthens the effect of low-carbon development on employment quality.

4.1.2. Analysis of the Government’s Threshold Effects on Employment Quality

- (1)

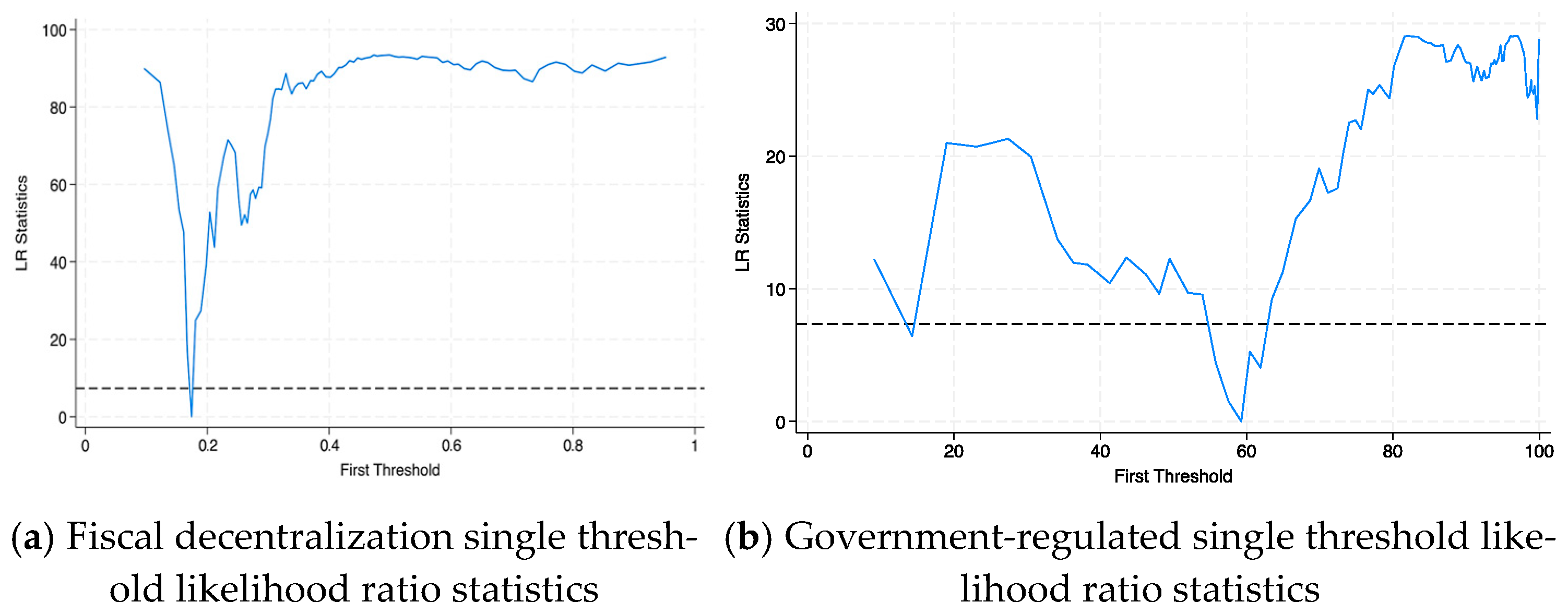

- Threshold Effect Test

- (2)

- Threshold Effect Analysis

4.2. Heterogeneity Analysis of the Mechanism

- (1)

- Non-resource-based cities

- (2)

- Growing resource-based cities

- (3)

- Mature resource-based cities

- (4)

- Regenerating resource-based cities

- (5)

- Declining resource-based cities

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Fiscal decentralization to some extent weakens the positive impact of low-carbon development on employment quality, whereas government regulation strengthens it by promoting green transformation and optimizing resource allocation. Fiscal decentralization may dilute the effect of low-carbon development on employment quality due to unbalanced resource distribution or deviations from low-carbon objectives. In contrast, government regulation enhances the positive impact by driving green transition, improving resource allocation, and creating high-quality employment opportunities.

- (2)

- There are threshold effects associated with fiscal decentralization and government regulation, with threshold values of 0.17 and 59.26, respectively. When fiscal decentralization is below the threshold of 0.17, low-carbon development inhibits improvements in employment quality; however, once fiscal decentralization surpasses the threshold, the negative effect shifts to a positive one. As for government regulation, low-carbon development promotes employment quality both below and above the threshold, but the magnitude of the positive effect decreases once the threshold is exceeded.

- (3)

- Heterogeneity analysis shows that non-resource-based cities have a lower threshold. In these cities, low-carbon development negatively impacts employment quality when fiscal decentralization is low, but promotes improvement when fiscal decentralization rises. In growing resource-based cities, the threshold is higher than that of the overall sample and employment quality improves significantly after fiscal decentralization increases. In mature resource-based cities, the threshold lies between that of non-resource-based and growing cities; although fiscal decentralization reduces the suppressive effect, its impact on employment quality remains significantly negative. In regenerating cities, the threshold is the highest, and increasing fiscal decentralization can promote employment quality. However, in declining resource-based cities, no threshold effect is observed, and due to substantial transformation pressures, improvements in employment quality are difficult even with higher fiscal decentralization.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

- (1)

- Improve the fiscal decentralization system in the process of promoting low-carbon economic transformation. Through adjustments in the fiscal relationship between the central and local governments, fiscal responsibilities related to low-carbon development should be rationally allocated. This would reduce the tendency of local governments to neglect environmental protection due to fiscal pressures, ensuring consistency and effectiveness in low-carbon development policies.

- (2)

- Strengthen government regulation by establishing stricter environmental protection standards and industrial entry thresholds. This will guide enterprises to adopt cleaner production technologies and circular economy models, reduce pollutant emissions, and improve resource utilization efficiency. Meanwhile, market mechanisms should be utilized to promote the research, development, and application of low-carbon technologies.

- (3)

- Formulate differentiated strategies according to the threshold differences across city types. Non-resource-based cities should seek higher-level fiscal support, enhance fiscal decentralization, develop diversified industries, and foster emerging low-carbon sectors. Growing resource-based cities should seize development opportunities, increase fiscal decentralization, focus on critical sectors, and improve employment quality. Mature resource-based cities should deepen fiscal decentralization, promote industrial restructuring, break structural rigidities, and strengthen the impetus for low-carbon development. Regenerating cities should leverage their advantages, enhance fiscal decentralization, support low-carbon industries, and promote coordinated progress. For declining cities, national and provincial-level support is needed; targeted transformation policies, greater transfer payments, and the guidance of social capital should be introduced to gradually improve employment quality.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carraro, C.; Galeotti, M.; Gallo, M. Environmental Taxation and Unemployment: Some Evidence on the ‘Double Dividend Hypothesis’ in Europe. J. Public Econ. 1996, 62, 141–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.N. Can the Greenization of the Production Process Promote Employment? Evidence from Clean Production Standards. J. Financ. Trade Econ. 2017, 3, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.H.; Sun, T. Environmental Regulation, Skill Premium and the International Competitiveness of the Manufacturing Industry. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 5, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, Y.W.; Yang, F. Research on the Impact of Environmental Regulation on the Skill Structure of Labor Employment. Stat. Inf. Forum 2022, 37, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.G.; Li, B. Research on the Impact and Path of Emission Trading on the Labor Demand of Enterprises—A Quasi-natural Experimental Test Based on China’s Carbon Emission Trading Pilot. West. Forum 2019, 29, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.Y.; Jiang, P.; Pan, Y. Does China’s carbon emission trading policy have an employment double dividend and a Porter effect? Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qi, Y. The Impact of Low-carbon City Pilot Policies on Employment under the “Double Carbon” Goals. East China Econ. Manag. 2024, 38, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Liu, C.K.; Wang, H. The Employment Creation Effect of Urban Green Transformation—Evidence from Low-carbon City Pilots. J. Zhongnan Univ. Econ. Law 2024, 1, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Green and Low-carbon Development and the High-quality Employment of Migrant Workers. J. South China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 22, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.Q.; Wang, J.L. How Does Green Manufacturing Balance Employment Stability? Evidence from the Evaluation of Green Factories. J. Shanxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 46, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstone, M. The Impacts of Environmental Regulations on Industrial Activity: Evidence from the 1970 and 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments and the Census of Manufactures. J. Political Econ. 2002, 110, 8484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raff, Z.; Earnhart, D. The effects of Clean Water Act enforcement on environmental employment. Resour. Energy Econ. 2019, 57, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissou, Y.; Sun, Q. GHG Mitigation Policies and Employment: A CGE Analysis with Wage Rigidity and Application to Canada. Can. Public Policy 2013, 39, S53–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Shadbegian, R.; Zhang, B. Does Environmental Regulation Affect Labor Demand in China? Evidence from the Textile Printing and Dyeing Industry. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 86, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, G.; Vona, F. The Impact of Energy Prices on Employment and Environmental Performance: Evidence from French Manufacturing Establishments. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 135, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, E.M. Who Loses under Cap-and-Trade Programs? The Labor Market Effects of the NOx Budget Trading Program. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2018, 100, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.Q.; Tao, L. Research on the Employment Effect of Environmental Regulation from the Perspective of Spatial Spillover Effects. Popul. Econ. 2021, 2, 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.W.; Zhao, J.S.; Wang, S. The Impact Mechanism and Empirical Analysis of Environmental Regulation on Employment in Resource-based Cities in China. East China Econ. Manag. 2020, 34, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.Y.; Cui, F. How Does Environmental Regulation Affect Employment? An Empirical Verification Based on Provincial Data in China. J. Xiangtan Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 45, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Q.Q.; Li, Z.X. The Impact Path and Effect of Environmental Regulation on High-quality Employment. Tax. Econ. 2023, 2, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.W.; Li, Z.R.; Cao, Y.R. Will Environmental Regulation Change the Structure of Labor Demand? Theoretical Analysis and Empirical Test Based on the “Ten Atmospheric Articles”. J. Quant. Econ. Tech. Econ. 2024, 41, 191–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Liu, L.H.; Sun, Z. Research on the Impact of Environmental Regulation on Employment—From the Perspective of Heterogeneity in China’s Industrial Sectors. Econ. Rev. 2018, 1, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, B.T.; Liu, L.; Yang, L.; Ge, L. Environmental Regulation and Employment in Resource-Based Cities in China: The Threshold Effect of Industrial Structure Transformation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 828188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. Green Policies and Employment in China: Is There a Double Dividend? Econ. Res. J. 2011, 7, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.H.; Jiang, Y.B. Research on the Impact of Environmental Protection Industry Policy Support on Labor Demand—Empirical Evidence from Listed Companies in Heavily Polluting Industries. Ind. Econ. Res. 2019, 1, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafstead, M.A.C.; Williams, R.C. Unemployment and Environmental Regulation in General Equilibrium. J. Public Econ. 2018, 160, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eq (Total) | Eq (Total) | Eq (Pilot Projects of Low-Carbon Cities) | Eq (Pilot Projects of Low-Carbon Cities) | |

| Ce | 0.055 ** | 0.078 ** | 0.034 * | 0.054 ** |

| Ce*Czfq | −0.146 ** | 0.277 *** | ||

| Ce*Zfgz | 0.002 *** | 0.001 ** | ||

| Czfq | −0.167 * | 0.596 *** | 0.293 * | 0.034 |

| Zfgz | 0.001 * | 0.002 ** | 0.001 | 0.010 * |

| _cons | −0.341 ** | −1.303 *** | −0.684 * | −0.686 * |

| adj. R2 | 0.8052 | 0.5268 | 0.634 | 0.628 |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Urban effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 4215 | 4215 | 1318 | 1318 |

| Threshold Variable | Number of Thresholds | F Value | p Value | 10% | 5% | 1% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Value Level | |||||||

| Benchmark regression | Fiscal decentralization | One | 93.68 | 0.000 | 28.455 | 35.33 | 49.549 |

| Two | 22.59 | 0.140 | 25.426 | 32.324 | 42.996 | ||

| Three | 6.58 | 0.890 | 25.65 | 31.251 | 41.847 | ||

| Government regulation | One | 39.11 | 0.090 | 28.447 | 35.123 | 55.048 | |

| Two | 19.5 | 0.157 | 23.466 | 28.279 | 40.471 | ||

| Three | 10.68 | 0.480 | 29.237 | 38.889 | 54.339 | ||

| Robustness test I | Fiscal decentralization | One | 93.94 | 0.000 | 25.975 | 30.281 | 39.244 |

| Two | 19.36 | 0.187 | 25.708 | 29.394 | 41.205 | ||

| Three | 6.54 | 0.870 | 24.576 | 29.984 | 50.343 | ||

| Government regulation | One | 5.51 | 0.060 | 12.970 | 15.418 | 21.679 | |

| Two | 8.53 | 0.197 | 11.075 | 12.635 | 16.399 | ||

| Three | 5.48 | 0.590 | 11.490 | 13.309 | 20.350 | ||

| Robustness test II | Fiscal decentralization | One | 72.24 | 0.000 | 27.307 | 36.312 | 54.577 |

| Two | 21.84 | 0.143 | 23.444 | 29.822 | 55.654 | ||

| Three | 22.51 | 0.333 | 33.347 | 39.513 | 47.460 | ||

| Government regulation | One | 7.43 | 0.047 | 12.469 | 14.874 | 21.497 | |

| Two | 14.18 | 0.363 | 11.905 | 13.927 | 19.285 | ||

| Three | 6.11 | 0.527 | 13.703 | 15.804 | 21.200 | ||

| Threshold Variable | Threshold | Threshold Value | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark regression | Fiscal decentralization | Threshold 1 | 0.174 | (0.167, 0.181) |

| Government regulation | Threshold 1 | 59.26 | (55.745, 60.44) | |

| Robustness test I | Fiscal decentralization | Threshold 1 | ||

| Government regulation | Threshold 1 | 46.39 | (37.760, 48.310) | |

| Robustness test II | Fiscal decentralization | Threshold 1 | ||

| Government regulation | Threshold 1 | 66.980 | (59.910, 68.970) |

| Variable | Benchmark Regression | Robustness Test I | Robustness Test II | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Ce(Czfq ≤ ) | −0.505 *** | −0.027 *** | −0.580 *** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > ) | 0.037 * | 0.042 * | 0.021 * | |||

| Ce(Czfq ≤ ) | 0.121 *** | 0.117 *** | 0.119 *** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > ) | 0.045 ** | 0.060 *** | 0.058 *** | |||

| Coefficient | −0.017 * | −0.672 * | −0.280 * | −0.653 *** | −0.075 * | −1.170 *** |

| adj. R2 | 0.498 | 0.489 | 0.380 | 0.474 | 0.504 | 0.598 |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Urban effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 4215 | 4215 | 4215 | 4215 | 4215 | 4215 |

| Non-Resource-Based | Growth-Oriented | Mature | Regenerative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ce(Czfq ≤ 0.155) | −0.465 ** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > 0.155) | 0.028 * | |||

| Ce(Czfq ≤ 0.209) | −0.366 ** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > 0.209) | 0.066 * | |||

| Ce(Czfq ≤ 0.191) | −0.638 ** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > 0.191) | −0.007 * | |||

| Ce(Czfq ≤ 0.267) | −1.164 *** | |||

| Ce(Czfq > 0.267) | 0.062 * | |||

| Coefficient | 0.292 * | 0.479 * | −0.735 *** | −0.429 * |

| adj. R2 | 0.521 | 0.157 | 0.256 | 0.379 |

| Control variable | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Urban effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sample size | 2535 | 210 | 900 | 225 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bo, Q.; Gao, X.; Pan, Y.; Liu, Y. The Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality in Chinese Cities—Based on the Government Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219374

Bo Q, Gao X, Pan Y, Liu Y. The Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality in Chinese Cities—Based on the Government Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(21):9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219374

Chicago/Turabian StyleBo, Qixin, Xuedong Gao, Yingxue Pan, and Yafeng Liu. 2025. "The Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality in Chinese Cities—Based on the Government Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 21: 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219374

APA StyleBo, Q., Gao, X., Pan, Y., & Liu, Y. (2025). The Mechanism of Low-Carbon Development’s Effect on Employment Quality in Chinese Cities—Based on the Government Perspective. Sustainability, 17(21), 9374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17219374