1. Introduction

Tourism accounts for roughly 10% of global GDP and remains a rapidly expanding sector. Adequate infrastructure is essential for sustaining tourism: visitors require transportation networks, accommodation, utilities, waste management, and leisure facilities. The literature distinguishes tourism (main) infrastructure—such as hotels, restaurants, and recreational facilities—from supporting infrastructure including roads, railways, airports, electricity, water, and communications [

1]. Beyond built systems, green infrastructure (GI) has gained prominence as a strategy for delivering ecosystem services and enhancing recreational experiences; it comprises interconnected parks, gardens, woodlands, natural areas, and green corridors. Empirical work documents that elements such as hiking trails, public parks, riverbanks, and greenways can catalyze sustainable tourism by raising aesthetic, ecological, and recreational value [

2]. In urban contexts, the co-location of attractions with GI has been linked to improved well-being and destination image. Together, these insights suggest that integrating hard and green infrastructure may benefit tourism, albeit in ways that are likely context-dependent.

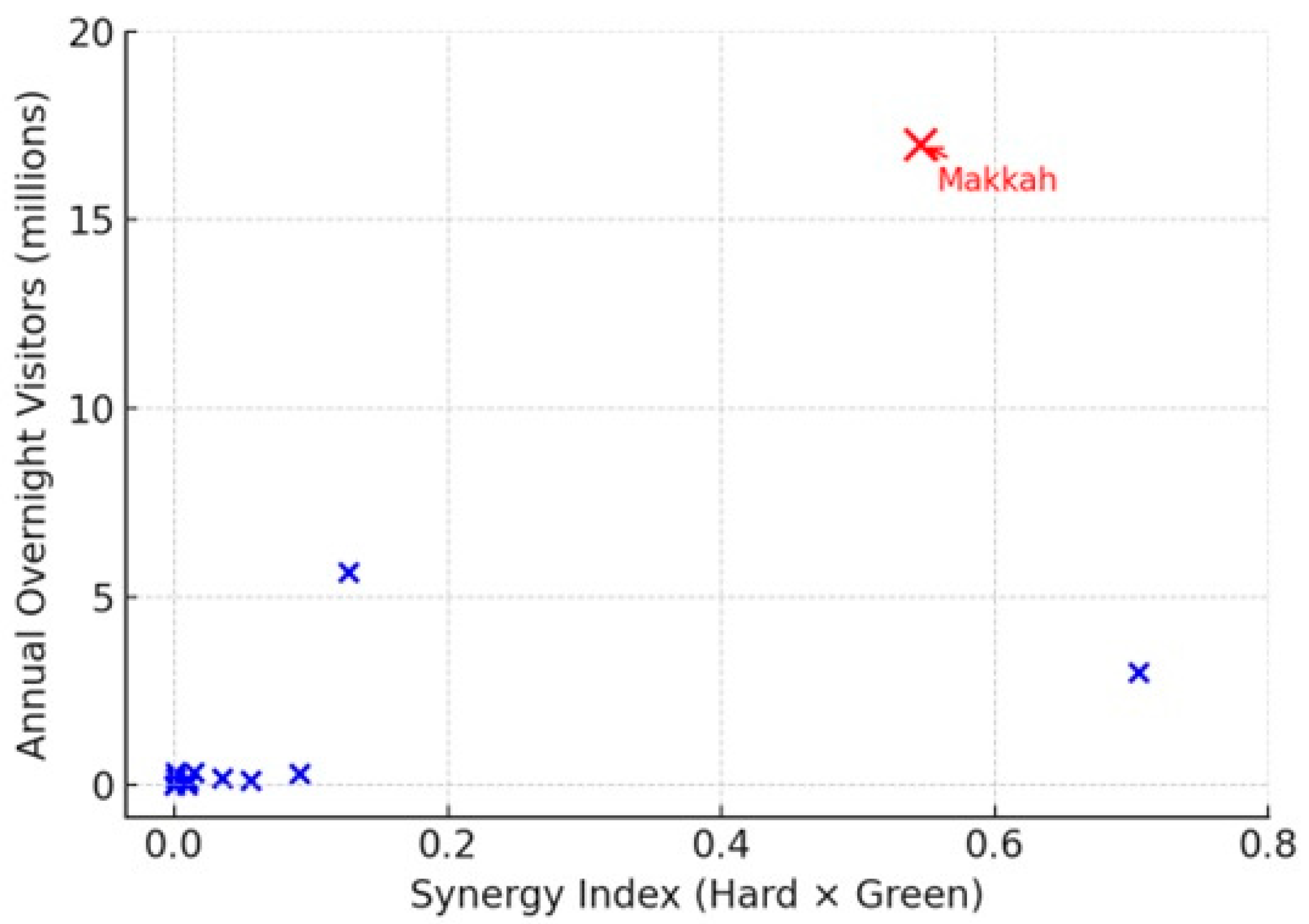

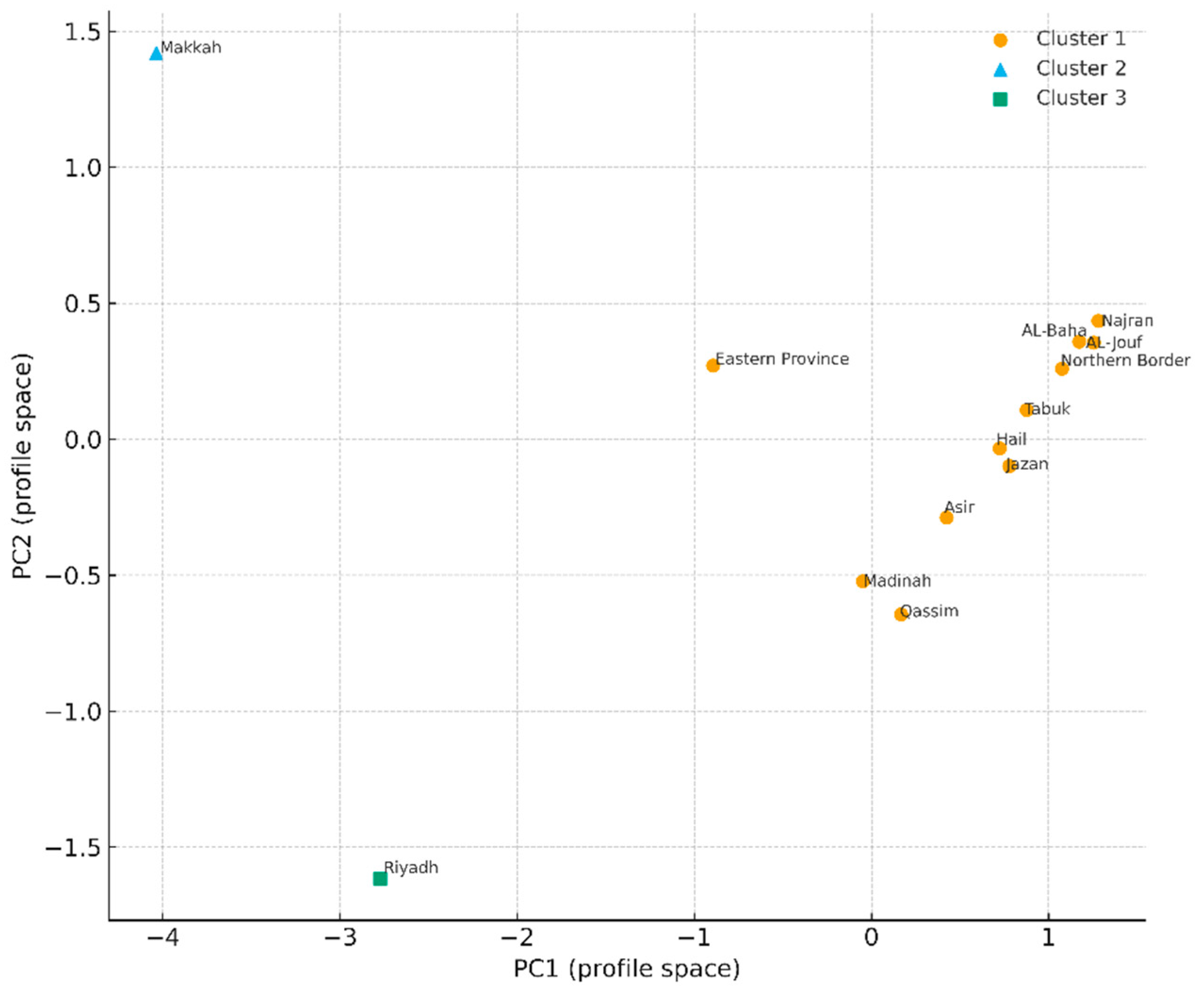

Within Saudi Arabia, pronounced regional disparities exist. Makkah annually receives more than 17 million visitors due to religious pilgrimage, whereas smaller regions such as Al-Baha host far fewer tourists (2023 statistics). Entertainment events, transport connectivity, and green-space provision also vary markedly across provinces. Yet, many prior analyses rely on national aggregates and standard, single-equation models that obscure spatial heterogeneity and potential interactions between built and green systems.

Beyond access and experience design, integrated provision has clear energy–environment linkages: compact access networks and high-quality public realm can reduce travel frictions, moderate energy use in hospitality and urban mobility, and enhance the environmental performance of destinations [

3]. From a broader sustainability perspective, cross-domain advances in energy transformation and environmental risk (e.g., reservoir energy systems and geomechanical stability) offer relevant framings for destination development and governance. In this spirit, we cite recent work on energy transformation platforms and environmental protection, as well as geomechanical sensitivity analyses related to subsurface gas production, to motivate the need for integrated, resource-efficient tourism strategies [

4,

5].

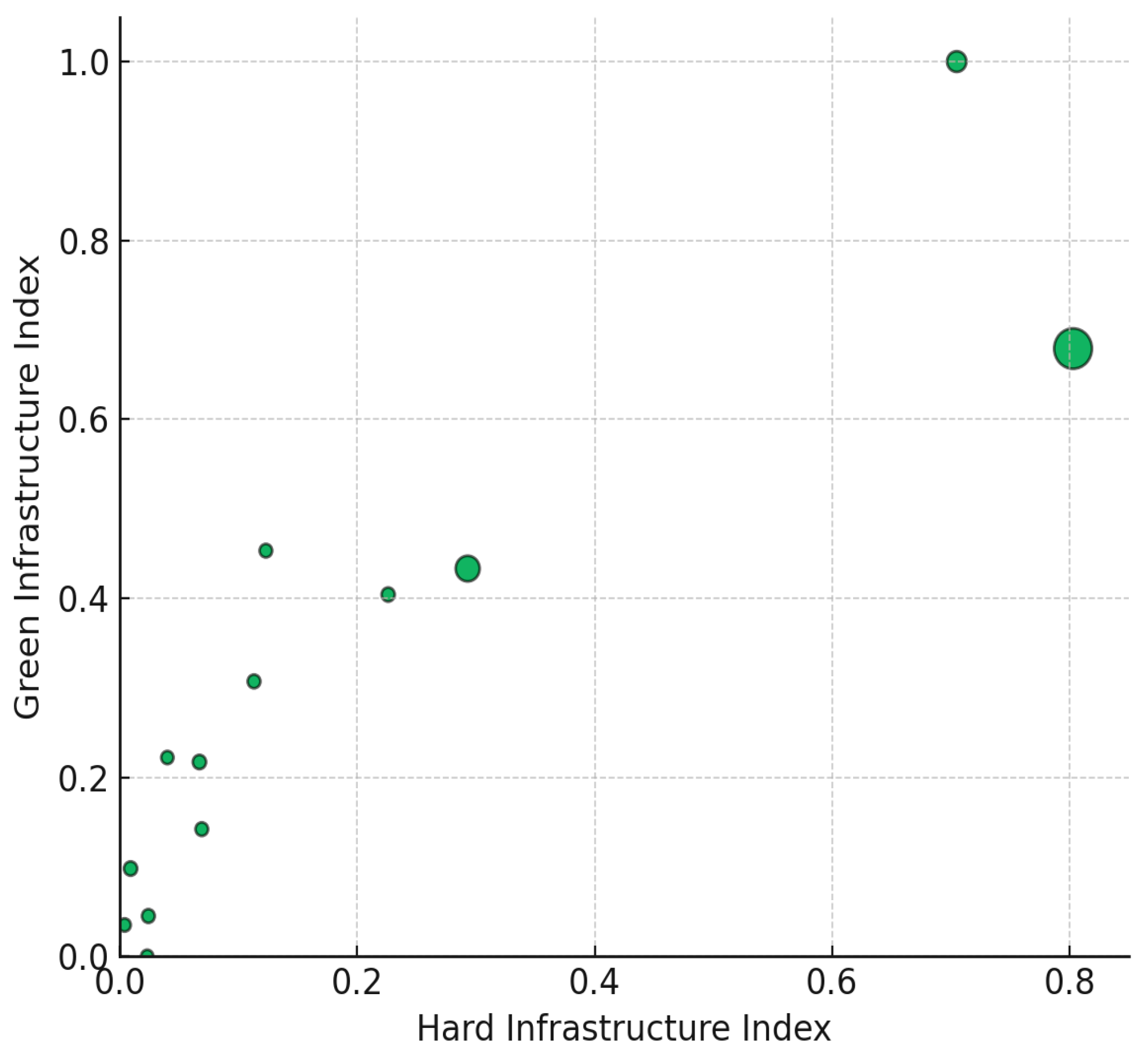

This study addresses that gap by jointly examining built (“hard”) and environmental (“green”) infrastructure across the Kingdom’s 13 regions, with a focus on whether their combined provision is additive or exhibits diminishing returns as built capacity increases. The research questions are: (i) How strongly do built and green infrastructure relate to regional tourism outcomes (overnight visitors and spending)? (ii) Does the marginal association of green infrastructure vary with built capacity (tested via a Hard × Green interaction)? (iii) Do these relationships vary spatially in ways that support actionable regional typologies.

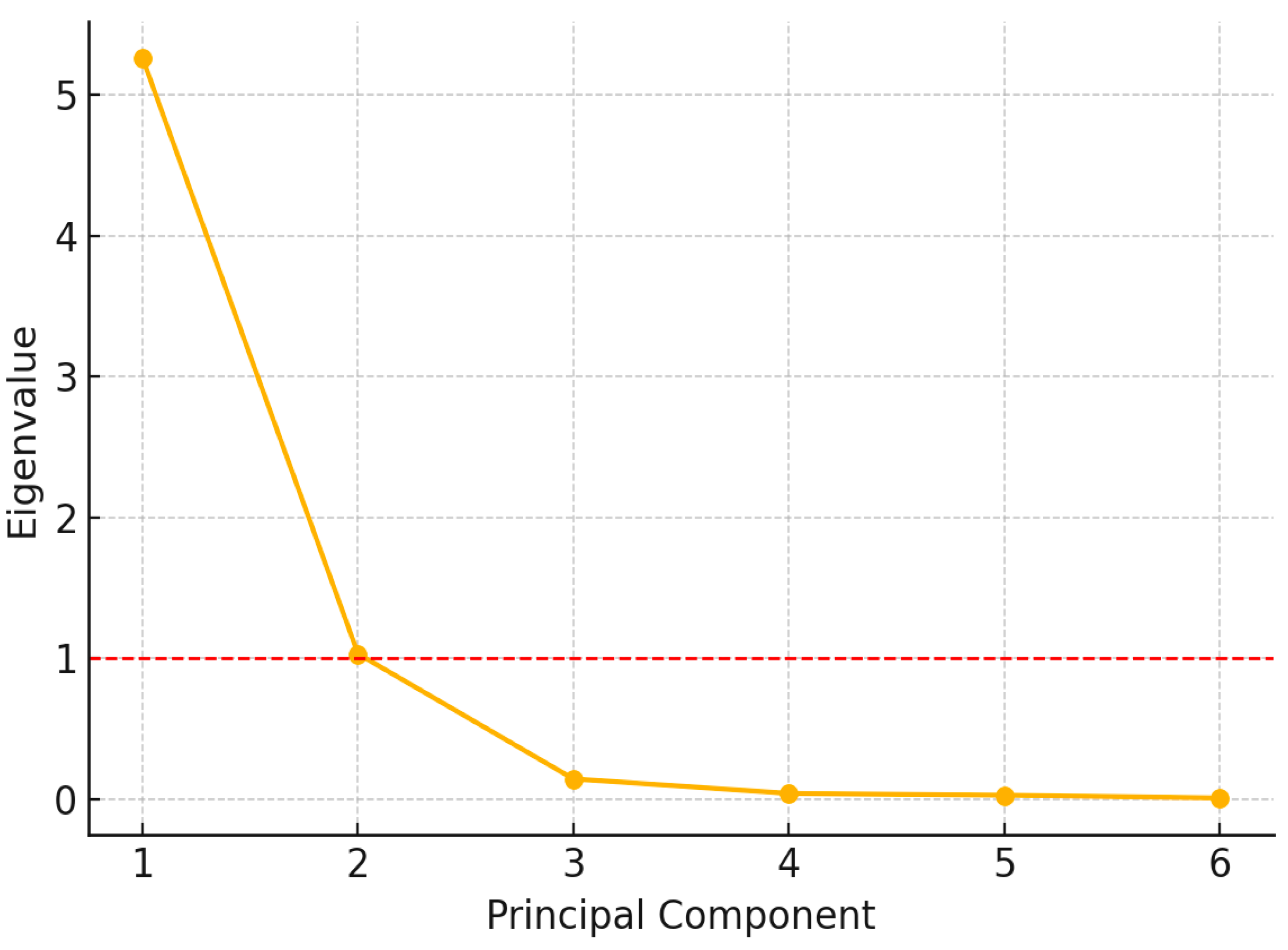

This study aims to quantify the separate and joint associations of built and green infrastructure with regional tourism performance across Saudi Arabia’s 13 regions, and to test whether their joint effect exhibits diminishing returns as built capacity increases. To this end, composite indices were constructed from official 2023–2024 data; OLS models with a Hard × Green interaction were estimated as the confirmatory backbone; geographically weighted regression was used to explore spatial heterogeneity; policy-relevant typologies were derived via clustering; and PCA was employed as a robustness check on index weighting. In doing so, the paper contributes to the growing literature on sustainability, competitiveness, and integrated tourism planning [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Literature Review

Tourism infrastructure and destination competitiveness

Infrastructure availability is widely acknowledged as a primary driver of tourism demand and destination competitiveness. Early empirical work in Turkey and Thailand demonstrated that reliable roads, water supplies, electricity and safety services strongly influence tourist arrivals. Cross-country analyses consistently show that destinations with well-developed transport systems and abundant accommodation attract more visitors and generate greater tourism receipts. Scholars have repeatedly identified accommodation and transport capacity as key predictors of tourism growth [

11,

12], while cross-sectional regressions confirm that investment in infrastructure positively influences arrivals [

13,

14]. Beyond these tangible elements, contemporary research emphasizes that infrastructure encompasses not only material assets but also intangible and digital resources. Smart tourism studies highlight how high-speed internet, mobile connectivity, big data and artificial intelligence enhance visitor experiences, improve resource efficiency and contribute to sustainability. Smart destinations leverage technologies to balance resource use and provide real-time information, enabling tourists and residents to enjoy more comfortable and resource-efficient experiences [

8,

15]. The sustainable tourism infrastructure planning (STIP) framework advocates integrated planning across attractions, services and transport facilities, embedding environmental criteria and visitor preferences [

16] and recognizing that digital infrastructure underpins modern tourism services. Notably, recent research has proposed composite indices that integrate environmental and social criteria into destination competitiveness evaluation, reflecting a shift towards a more holistic and sustainable assessment of tourism performance [

17].

Green infrastructure and sustainable tourism

Green infrastructure (GI) is conceived as an interconnected network of natural and semi-natural areas—parks, gardens, woodlands, natural areas, green streets and boulevards—that deliver ecosystem services and recreational opportunities [

2]. Research on the parallel development of green infrastructure and tourism reveals that public parks, hiking trails, riverbanks and green corridors enhance destination appeal and create opportunities for ecotourism and active tourism. GI not only increases the attractiveness of tourist destinations but also contributes to climate regulation, biodiversity conservation and social well-being [

2,

18]. In urban contexts, studies show that synergy between tourist attractions and urban green infrastructure can enhance residents’ well-being and improve destination image [

19,

20]. However, empirical evidence on such synergy remains limited, as most research focuses on individual GI elements rather than holistic networks [

2]. These insights imply that integrating green and built infrastructure within tourism planning can yield substantial benefits while promoting environmental sustainability [

21]. Moreover, emerging destinations in the MENA region face sustainability trade-offs; recent evidence from North Africa shows that tourism expansion can drive up energy consumption and carbon emissions if not accompanied by environmental safeguards [

3,

22,

23], underscoring the importance of sustainable infrastructure investment.

The concept of synergy captures how built (hard) and green (natural) infrastructure may jointly enhance tourism outcomes beyond the sum of their separate effects. Some scholars argue that complementary investment in high-quality accommodation, transport and entertainment facilities alongside parks, trails and other green spaces creates appealing environments that attract visitors and encourage longer stays. Empirical evidence is mixed. Studies from Hungary show that linear green infrastructure elements—public parks and alleys—complement tourism attractions and increase their value [

2]. A recent study across Japanese cities suggests that the synergy between urban green infrastructure and tourist attractions varies with city size and economic structure, yielding overall benefits but limited evidence of multiplicative effects [

11,

20]. These findings indicate that synergy effects are context-dependent and that additive contributions of hard and green infrastructure are more common than multiplicative ones. Understanding the mechanisms of synergy and identifying where integrated investment yields the largest returns remain important research frontiers.

Synergy between built and natural infrastructure

Recent scholarship has broadened the geographic scope of synergy research to include the Arab region and other emerging economies. For example, Idris et al. (2025) analyze how tourists, infrastructure and institutions jointly shape sustainable tourism outcomes in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, demonstrating that governance and ecological amenities significantly influence tourism performance [

9,

24]. Similarly, Yang and Homma (2025) examine the synergistic relationships between urban attractions and green infrastructure across Japanese cities using a green tourism framework, finding that synergy effects vary with city size and development patterns [

20]. These contemporary studies extend earlier work by contextualizing synergy in diverse cultural and economic settings and underscore the need to integrate built and natural assets within broader sustainability frameworks [

25,

26].

Analytical approaches in tourism research

Researchers employ diverse analytical techniques to explore tourism determinants and infrastructure effects. Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation coefficients measure the strength and direction of associations between variables. Multiple linear regression models estimate the net effect of infrastructure while controlling for socio-economic factors, assuming linearity, independence of errors and normality of residuals [

27]. Unsupervised clustering algorithms such as k-means partition destinations into homogeneous groups based on infrastructure and tourism characteristics, revealing typologies. Geographically weighted regression (GWR) addresses spatial non-stationarity by calibrating local regressions with kernel weights, allowing coefficients to vary across space [

28,

29]. Principal component analysis (PCA) summarizes correlated variables into orthogonal components, mitigating multicollinearity and enabling robustness checks [

30]. Beyond these techniques, advanced methods such as structural equation modeling (SEM) allow researchers to evaluate complex causal pathways among latent and observed variables. For example, a study of Nigerian eco-destinations used SEM to analyze relationships among ecotourism practices, tourism development agendas and socio-economic factors, finding significant positive links between ecotourism practices and tourist satisfaction. Smart tourism research also highlights the use of big data analytics, machine learning and remote sensing to monitor visitor flows, optimize resource allocation and enhance destination competitiveness. These methodological advances underscore the need for multi-method approaches that capture both global patterns and local variations in tourism systems.

4. Discussion

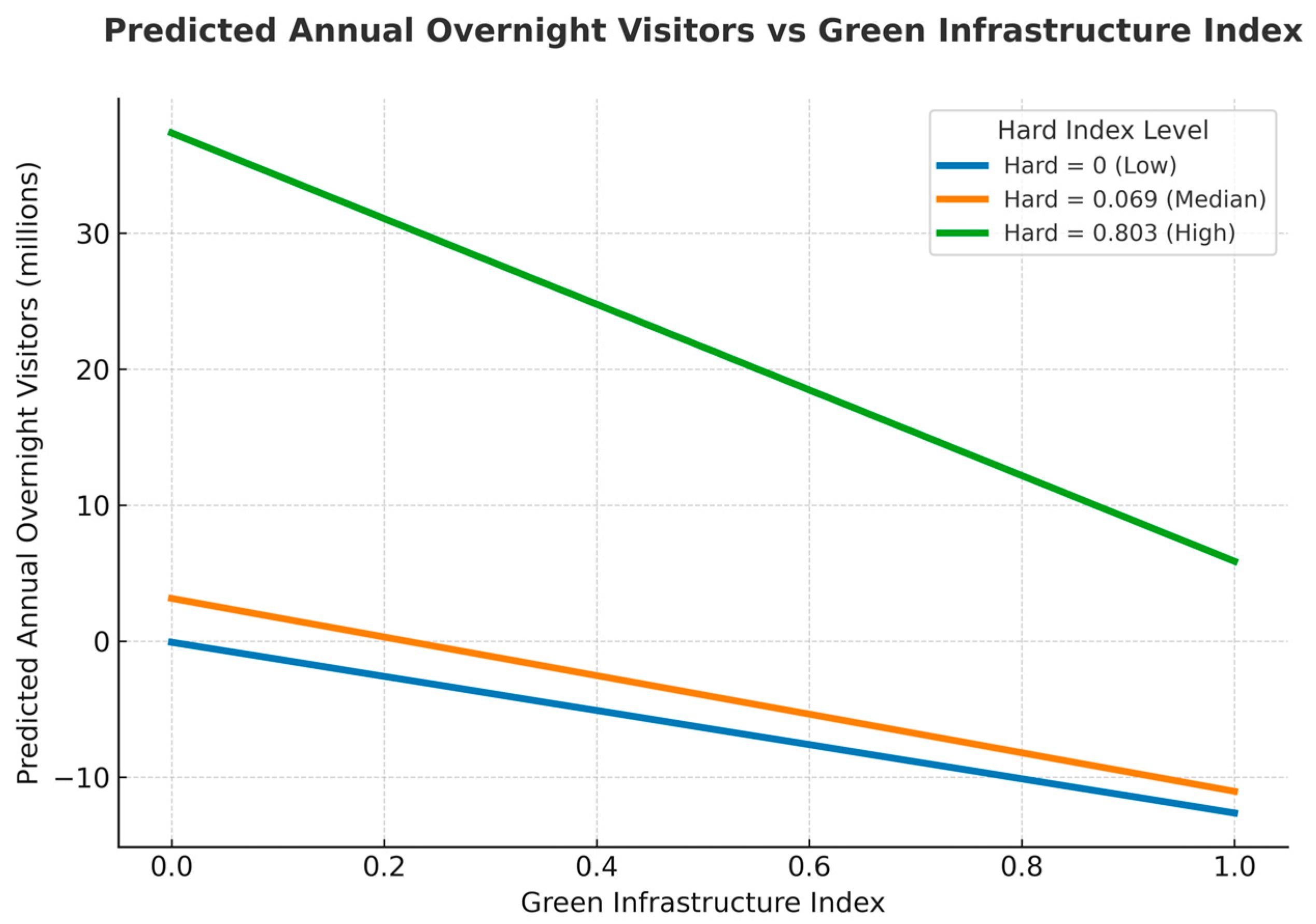

The results indicate a clear hierarchy of effects: built infrastructure shows the strongest and most consistent association with regional tourism performance, in line with destination-competitiveness research that emphasizes access and accommodation as foundational enablers [

32,

33]. Green infrastructure contributes conditionally rather than uniformly: the negative, statistically significant Hard × Green interaction in the OLS models indicates diminishing marginal returns to greening as built capacity increases—i.e., within the observed hard-capacity range, the marginal association of Green is non-positive and becomes more negative at higher hard levels. Methodologically, interpreting the interaction via mean-centering and simple-slope probes (with HC1 inference) prevents product-term misreading and clarifies that “synergy” here is bounded, context-dependent complementarity rather than a universally multiplicative effect [

31]. Exploratory spatial diagnostics further reveal non-uniform patterns across regions, reinforcing the need for place-specific policy rather than one-size-fits-all prescriptions [

28]. Taken together, the evidence supports sequencing: ensure adequate built capacity first, then deploy targeted green upgrades where they yield the greatest marginal gains.

The findings also contribute to debates on spatial heterogeneity in tourism development. Considerable spatial variation was observed in the strength of infrastructure–tourism relationships: for instance, entertainment and accommodation capacity yield the largest payoffs in metropolitan business hubs, whereas green amenities are comparatively more influential in smaller mountain regions where natural landscape value is central to destination appeal. This resonates with multi-scalar perspectives linking infrastructure effectiveness to local context—urban form, environmental endowments, and demand composition [

28,

34]—and reinforces that one-size-fits-all policies may be suboptimal; instead, tourism strategies should account for regional differences in how built and natural assets translate into outcomes.

Policy implications:

The results have practical implications for infrastructure investment and tourism planning, particularly in the context of sustainable development goals. Because built capacity is foundational, emerging regions with low infrastructure endowment must prioritize baseline investments in transport, accommodation and utilities. In high-capacity urban hubs, by contrast, the strategy should shift from sheer expansion to quality upgrades, better management and the enhancement of the public realm. For instance, congested city destinations might focus on improving transit efficiency, urban design (e.g., shaded walkways, green roofs) and event curation rather than building new hotels. In built-dominant regions that currently lack green amenities, targeted introduction of green belts, urban parks or linear green corridors connecting key attractions can help extend visitor length-of-stay and improve the overall experience. Green-rich regions with moderate built capacity (such as nature-based destinations) should invest in eco-lodging, trail networks and visitor management plans that leverage their natural assets while preserving ecological integrity. In all cases, integrated planning is crucial: the findings support the view that jointly scheduling transportation, accommodation and green-space developments is preferable to pursuing “green only” or “built only” expansion in isolation [

12,

16,

20,

32,

33]. An integrated approach can create complementary effects—ensuring that, for example, new attractions are accessible and well-serviced, or that new parks are connected to tourist circuits—thereby maximizing the sustainable competitiveness of destinations.

Limitations and future research:

This study has several limitations. The use of cross-sectional regional data limits the ability to infer dynamic effects or causal relationships over time. The small sample of regions (

N = 13) reduces statistical power and constrains the complexity of models can be reliably estimated; in particular, it limits the number of control variables and interaction terms that can be included. The composite indices used equal weights, which, while transparent, are a simplification that may not capture the true importance of each component. It was attempted to address this through alternate weighting (PCA, entropy, DEA), but future research could benefit from more sophisticated index construction or validation. Moreover, the Green Infrastructure measure is relatively coarse (focused on parks and green space area); it does not directly account for quality aspects like biodiversity, ecosystem health or maintenance level. Future studies should incorporate richer green infrastructure metrics—such as habitat connectivity, canopy cover, or water quality in natural attractions—to more fully capture the environmental dimension of tourism infrastructure. A longitudinal approach (assembling panel data over multiple years) would allow examination of lagged effects and the trajectory of development (e.g., testing for tourism area life-cycle dynamics in infrastructure impacts). Such time-series (panel) designs are essential to disentangle transitory shocks from structural trends, identify dynamic and lagged effects, and strengthen causal interpretation of infrastructure–tourism linkages under Vision 2030 timelines. With more data, researchers could also explore non-linear models to detect thresholds or tipping points (for example, identifying at what level of infrastructure investment diminishing returns set in). There is also scope to apply multi-level or multiscale spatial models: finer-grained data (e.g., at city or district level within regions) could enable hierarchical modeling or multiscale GWR to test how neighborhood-level amenities and city-level capacities interact. Such approaches, along with modern spatial analysis techniques, can provide a more nuanced understanding of how infrastructure and tourism outcomes are linked across different scales [

11,

14,

18,

19,

20]. Despite these limitations, this study provides an integrative framework and initial evidence to inform sustainable tourism infrastructure planning in Saudi Arabia and comparable contexts.

These results align with international evidence that tourism performance emerges from the joint provision of access, accommodation and high-quality public realm. In metropolitan hubs, marginal gains increasingly come from quality upgrades and place-making (e.g., shaded streets, green roofs, and urban design) rather than sheer capacity expansion. In nature-based destinations, targeted eco-lodging, trail networks and visitor-management systems can translate environmental amenities into longer stays and higher willingness-to-pay while safeguarding ecological integrity.

From a measurement perspective, using both composite indices and dimensionality-reduction techniques (e.g., PCA) helps validate constructs and mitigate multicollinearity. Robustness checks that contrast equal-weight indices with data-driven weights are especially important when indicators capture heterogeneous infrastructure domains. Complementary clustering can reveal tractable regional typologies that support differentiated policy strategies.

Policy should therefore be sequenced: baseline transport and accommodation where endowments are low; integration and experience design where networks are mature; and ecological safeguards in green-rich regions. Integrated planning timelines that coordinate transport links, event calendars and green-space connectivity maximize complementarities and reduce the risk of stranded investments.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that regional tourism performance in Saudi Arabia is anchored primarily in built infrastructure, with green infrastructure adding value in a conditional manner. Where access and accommodation remain below saturation, incremental green investments are associated with higher visitation; where built capacity is already extensive, returns to additional greening appear smaller, indicating conditional complementarity rather than universal multiplicative synergy. Exploratory spatial diagnostics and clustering further reveal meaningful heterogeneity across regions, cautioning against uniform policy prescriptions.

For policy and planning, our results support a sequenced and integrated approach: (i) prioritize foundational transport and accommodation where endowments are low; (ii) shift toward quality upgrades, visitor-flow management, and public-realm enhancement (e.g., connected green corridors, shading, and walkability) in mature urban hubs; and (iii) leverage targeted, conservation-aligned green infrastructure in nature-based destinations to extend length of stay while safeguarding ecological integrity. Methodologically, the evidence base would benefit from richer measures of environmental quality (e.g., canopy cover, habitat connectivity) and panel data to identify non-linearities and temporal thresholds in infrastructure–tourism relationships. Overall, the findings refine the synergy narrative by framing it as bounded, context-dependent complementarity and emphasize integrated, place-specific planning to advance sustainable tourism outcomes.