1. Introduction

One of the most notable developments in recent years has been the emergence of the metaverse. The metaverse is not merely a digital innovation but also a transformative force shaping contemporary social life [

1,

2,

3]. It can be defined as an expansive virtual universe where users communicate and interact within three-dimensional digital environments [

4,

5]. These virtual spaces form an integrated ecosystem that combines various digital technologies, including augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), mixed reality (MR), as well as blockchain, artificial intelligence, digital twins, cloud computing, and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) [

6,

7]. Through these digital components, the metaverse operates as a virtual environment that supports activities in gaming, entertainment, education, and increasingly, social and economic interaction [

8,

9].

Metaverse technologies are composed of large-scale digital platforms and can be classified into several categories. Social metaverse platforms are virtual environments that allow individuals, particularly young people, to socialize, communicate, and interact, while also offering access to various types of digital content. In addition, institutional metaverse platforms have become increasingly prevalent in fields such as healthcare, policymaking, and education [

10,

11,

12]. Particularly relevant to the focus of this study is the growing use of metaverse technologies to develop and deliver educational content aligned with environmental sustainability goals [

13,

14]. For instance, the creation of virtual scenarios related to global warming and environmental issues is becoming increasingly common, especially in the formulation of environmental plans and policies. Considering these developments, metaverse technologies have evolved beyond gaming and entertainment purposes and are now being adapted for institutional use. Through virtual simulations and the outcomes they generate, these technologies are increasingly used as decision-support tools for policymakers and decision-makers [

15,

16]. However, their adoption represents a multilayered process shaped by societal and cultural norms, levels of technology acceptance, and the capacity of communities to adapt to digital transformation [

17,

18,

19].

Beyond their institutional applications, metaverse technologies hold significant potential for addressing social and environmental challenges in more practical ways. For instance, virtual platforms can facilitate community engagement in sustainable practices by simulating the environmental impacts of individual and collective behaviors [

20,

21]. They can also support environmental awareness campaigns, encourage pro-environmental behaviors through gamified experiences, and enable collaborative design of eco-friendly urban spaces. By integrating immersive learning with participatory decision-making, metaverse technologies thus act as a bridge between technological innovation and sustainable environmental action [

22,

23].

The use of these technologies to advance environmental sustainability goals has considerable potential to enhance both individual education and societal awareness [

24,

25]. Through simulations developed within virtual environments, it is possible to predict the negative impacts of individuals and society on the environment. These insights, in turn, can contribute to the formulation of preventive plans and policies [

26,

27,

28].

Today’s rapidly advancing technological developments not only offer significant conveniences across all areas of social life but also act as catalysts for the transformation of vital human activities. Digital transformation has become increasingly prevalent in key sectors such as education, the economy, and politics [

29,

30,

31]. In recent years, this transformation is expected to generate profound impacts, particularly in achieving clean and safe environmental goals within the broader framework of sustainable development. This is especially critical as leisure activities—characterized by high levels of human mobility—exert substantial pressure on natural ecosystems and pose serious risks to the protection and sustainable management of forested areas [

32].

The gap between rapid technological advancements and the integration of digital infrastructures into sustainability initiatives is increasingly widening. While developing technological infrastructures provides convenience and solutions in certain areas, environmentally friendly applications and policies face significant challenges in raising awareness, monitoring, and analyzing environmental impacts, and managing resources over the long term [

33]. Deficiencies in societal infrastructures, variations in education and technology acceptance levels, and socio-cultural differences result in meaningful disparities in the use of digital tools. Consequently, digital solutions such as the metaverse offer substantial advantages, yet they also entail notable limitations in environmental management practices. These limitations are further compounded by insufficient investment, limited budgetary resources, and gaps in political and institutional frameworks [

34,

35]. Rapid urbanization continues to intensify global climate change, while the unplanned consumption of natural resources leads to destructive consequences for the environment, particularly forest ecosystems [

36]. Considering these challenges, integrating technological transformation into the management of sustainable forest areas and utilizing it as a decision-support mechanism has become imperative.

The leisure industry, due to its intense human mobility and participation, is associated with numerous negative environmental impacts. Among the sectors most significantly affecting the natural environment are leisure activities organized in natural settings such as forested areas, where issues such as carbon emissions, waste generation, and energy consumption are particularly prominent [

37,

38,

39]. Therefore, to mitigate the environmental impacts of the leisure industry and to foster positive environmental behavior change among individuals, the adoption and implementation of digital solutions—particularly metaverse technologies—has become increasingly important. Integrating metaverse technologies into educational and awareness-raising initiatives, especially those targeting clean and safe environmental objectives in natural areas like forests, may also support decision-makers in the management process.

Environmental management in forested areas is of critical importance for the conservation of biodiversity, the sustainable utilization of carbon storage capacity, and the maintenance of ecosystem services [

40]. The sustainable governance of forest landscapes plays a vital role in maintaining ecological balance, protecting biological diversity, enhancing carbon sequestration potential, and ensuring the proper functioning of ecosystems [

41]. To achieve these objectives, the application of effective and innovative environmental management strategies is essential. This requires the adoption of participatory approaches, the widespread implementation of data monitoring systems, and the balanced and planned use of natural resources [

42]. Furthermore, integrating local communities living in forest regions into decision-making processes and utilizing data-driven knowledge systems can significantly contribute to the sustainable management of forest areas [

43].

Recent research emphasizes the importance of this situation. It reveals important contributions regarding the use and importance of metaverse technologies in the fields of environmental education, awareness promotion, and environmental sustainability. For example, it is understood that the use of virtual reality environments as an educational tool increases the understanding of climate change and environmental problems and raises awareness among individuals [

44,

45]. In this regard, it is foreseen that metaverse technologies and environments can be used to serve sustainable development goals; environmental impacts can be predicted in advance with scenarios to be created in virtual environments [

46]. At the same time, educational processes in virtual environments can also be used to change people’s environmental behaviors [

47]. When evaluated in this context, it reveals that more research is needed on the extent to which digital platforms, especially metaverse, will contribute to clean and safe environmental goals in natural environments such as forest areas. For example, environmental awareness and behavior change can be targeted through virtual educational videos and simulations. Environmentally conscious behavior among students and young people can be promoted. By integrating metaverse technologies into environmental management, potential adverse environmental impacts can be anticipated in virtual testing environments, and environmental measurements can be conducted within these virtual spaces. Furthermore, social participation can be enhanced, thereby expanding institutional and community collaborations. Through these social benefits, the positive development of the relationship between humans and the environment can be fostered [

48,

49]. Based on these rationales and expectations, it is of great importance to conduct comprehensive research on the applicability of metaverse technologies across different disciplines.

The main objective of this study is to assess the potential of metaverse technologies in contributing to clean and safe environmental goals in forest-based leisure settings, through a comparative analysis of the cases of Turkey and Lithuania. The study aims to explore and contrast the perceptions, experiences, and recommendations of different stakeholders in relation to this issue.

In this context, the study aims to explore the functions of metaverse technologies in fostering environmental awareness and supporting the sustainable management of forested areas. It also seeks to identify the institutional, social, and cultural differences between the two countries and to provide a comprehensive assessment of the key factors influencing the adoption and dissemination of these technologies. Through a comparative analysis focused on Turkey and Lithuania, the study intends to reveal the variations in how metaverse technologies are applied in pursuit of clean and safe environmental objectives within two distinct political and societal frameworks. In this regard, the study is not only grounded in theoretical perspectives but also aspires to offer practical planning and policy recommendations.

While Turkey possesses significant potential due to its rapidly expanding leisure industry and ongoing technological initiatives [

50,

51], for example, some sports facilities have implemented smart systems to monitor energy consumption and digital applications to enhance user engagement. Lithuania, on the other hand, is recognized as a leading country in digitalization within its region and maintains a swift pace of technological transformation [

52]; for instance, metaverse-based educational simulations and environmental monitoring applications are being utilized in forest recreation areas.

Accordingly, a comprehensive comparison between these two countries offers valuable insights into how metaverse technologies are adopted under varying conditions and how they can be utilized in pursuit of sustainable environmental goals. In this regard, the study aims to bring a novel perspective to the literature by evaluating digital transformation within two distinct national contexts and exploring how technological initiatives contribute to environmental sustainability objectives. Furthermore, by highlighting the relationship between sustainability goals and metaverse technologies both in theory and in practice, the research provides a foundation for cross-cultural comparisons between two diverse societies.

While existing literature increasingly explores digital and immersive technologies within the field of environmental awareness and education, empirical work specifically examining metaverse applications as a tool for sustainability-oriented behavioral change remains scarce. Most studies in this area focus either on virtual learning environments or on gamified digital interventions designed to promote eco-friendly attitudes; however, they rarely conceptualize the metaverse as a socio-technical infrastructure embedded within broader governance, policy, and participation dynamics. By approaching the metaverse not only as a technological medium but also as an institutional interface where environmental perception, policy discourse, and digital engagement intersect, this study addresses a significant gap in current academic discussions.

Theoretical Framework

This study focuses on the use and potential contributions of metaverse technologies to sustainable environmental goals within the leisure industry. Within this scope, the research questions are addressed through three fundamental theoretical approaches.

The first is the digital transformation theory. According to this approach, organizations utilize technological and digital tools not only to improve operational efficiency but also to enhance managerial and institutional processes [

53,

54]. In this regard, metaverse technologies are not merely digital platforms; rather, they function as tools that enable real-time data collection and analysis, thereby contributing to improved managerial decision-making. From this perspective, the metaverse may support the development and diffusion of data-driven management practices in the leisure sectors.

The second theoretical lens is the Diffusion of Innovations Theory, which explains how emerging technologies and digital advancements are adopted by individuals, institutions, and societies—often reflecting their responses to innovation [

55]. Within this framework, the study comparatively evaluates the acceptance, use, and dissemination of metaverse technologies in the leisure sectors of Turkey and Lithuania, two countries with distinct institutional and societal structures. The third theoretical approach is the Institutional Theory, which focuses on how organizations adapt to social, cultural, and legal structures and the pressures arising from these contexts [

56]. Given that metaverse technologies create a distinct digital environment, the study examines how actors within the relevant institutions in both countries adapt to this virtual setting. Together, these three theoretical approaches provide a comprehensive lens through which to understand how metaverse technologies are perceived, applied, and accepted in the leisure industry with respect to sustainable environmental goals. They also enable a comparative analysis between Turkey and Lithuania. In this context, the study offers insights into the role of the metaverse not only as a digital innovation but also as a socio-cultural and institutional governance tool.

Furthermore, the institutional structures of Turkey and Lithuania shape how technologies are transferred and how attitudes and behaviors toward the diffusion of these technologies for sustainable environmental goals are formed. While Lithuania, as a member of the EU, operates within a more structured legal framework concerning digitalization and environmental protection, Turkey exhibits more flexible and pragmatic approaches toward emerging technological tools.

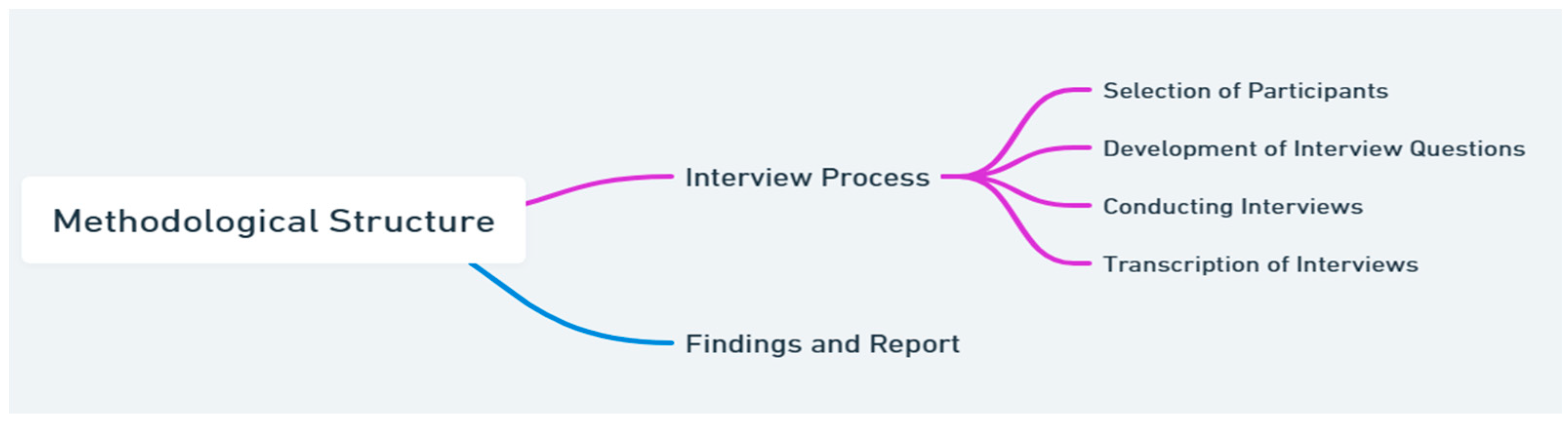

Targeting multiple disciplines such as leisure, environment, technology, and software, this research aims to produce clear, comprehensible, and objective outcomes. In line with this objective, the authors have adopted a research process that adheres to academic and scientific standards. The planning of the research process is visualized and presented to the reader in

Figure 1 below.

3. Results

This section of the study presents the findings derived from interviews conducted with experts from both countries regarding the use of metaverse technologies to achieve clean and safe environmental objectives in forested areas. The responses provided by the experts during the interviews were systematically categorized, compiled, and analyzed by the researchers. In the presentation and interpretation of the findings, principles of transparency in data sharing were adhered to, and expert opinions were directly quoted to provide readers with authentic insights.

Table 2 displays the prominent themes and sub-themes emerging from the experts’ perspectives in both countries concerning the potential of metaverse technologies to raise environmental awareness within the leisure sector. Based on the content analysis conducted, five (5) main themes and their associated sub-themes were identified, specific to each country. These themes are “Interactive Environmental Education,” “Digital Campaigns and Mass Outreach,” “Virtualization of Nature-Based Experiences,” “Reduction of Physical Impact,” and “Use as a Policy and Planning Tool.” The main themes and sub-themes that emerged are detailed in

Table 2.

The identified themes clearly reflect how experts from both countries position metaverse technologies in relation to achieving clean and safe environmental goals and enhancing awareness. In particular, the emerging thematic structure reveals that the experts perceive metaverse technologies as a comprehensive and multifaceted platform for increasing environmental awareness. To elucidate the differences in the application of these themes, a closer examination of the two countries was conducted.

Table 3 presents the distribution of the themes according to country, highlighting similarities and differences, and provides a comparative analysis.

In this context, the sub-themes support the main themes that were commonly identified for both countries, while some sub-themes arose from practices specific to a single country. For example, in Turkey, awareness themes related to the digital literacy levels of young users were more prominent, whereas in Lithuania, themes concerning the sustainable use of institutional digital infrastructure were more pronounced. These differences highlight the country-specific impacts of metaverse applications on societal awareness and digital usage.

Experts from both Turkey and Lithuania expressed converging views regarding the role of metaverse technologies in fostering awareness for environmental sustainability. However, despite these shared perspectives, significant differences emerge in the implementation processes. In both countries, the notion that metaverse technologies can be effectively utilized within environmental education programs is prominently highlighted. Particularly, through technology transfer, digital technologies are recognized as valuable educational tools. The creation of more accessible educational models via virtual experiences has the potential to advance clean environment objectives. Consequently, it is evident that metaverse technologies can contribute to enhancing environmental awareness in both contexts.

Metaverse technologies have the potential to effectively support an interactive and engagement-based educational process aimed at achieving clean and safe environmental goals. Considering that approximately 90% of the youth in the country have a high interest in and frequent use of technology, proper guidance can significantly enhance environmental awareness. The use of simulations and audiovisual educational environments increases participation, resulting in observable improvements in learning and awareness levels in about 80% of students (Academic from Turkey and Recreation Expert from Turkey). Moreover, metaverse applications present environmental issues and mitigation strategies visually and audibly, providing higher functionality compared to traditional educational methods. Similarly, in applications conducted in Lithuania, 75% of participants reported positive effects of metaverse-based education on environmental awareness and sustainable practices (Academic from Lithuania and Recreation Expert from Lithuania).

In Turkey, besides environmental education programs, it is also understood that metaverse technologies are preferred for public campaigns and mass communication methods conducted by governmental institutions, aiming at broader and more comprehensive dissemination of environmental awareness. Particularly, with a nationwide awareness strategy, metaverse technologies are increasingly viewed not only as educational tools but also as instruments for social communication. This dual role may facilitate the expansion of environmental awareness across both individual and societal levels.

It is possible for services provided by public institutions to reach a larger audience through digital platforms. Awareness campaigns focused on environmental issues can be designed visually and disseminated to broader populations. Metaverse technologies can serve as a next-generation awareness platform to enhance the reach of these campaigns (Public authority and NGO representatives from Turkey). Especially in urban areas, the simulation of nature and environmental experiences for city dwellers can facilitate their connection with the environment. Sustainability-related awareness messages can be gamified and enriched with VR-supported experiences, making the process engaging and enjoyable. This approach has significant potential to attract interest, particularly among young people (Software developer from Turkey). Interactive workshops have been increasingly utilized by municipalities in recent times. Moreover, virtual simulation islands are rapidly spreading in universities. Through specialized robotic coding courses, digital literacy and access to technology are also becoming more widespread (Software developer from Turkey).

Unlike Turkey, Lithuania demonstrates a systemic and long-term perspective in this regard. Experts from Lithuania emphasize that metaverse technologies should not be regarded solely as educational tools but also as instruments applicable in environmental planning, as well as in the preparation of plans and policies. They highlight that virtual scenarios developed at the national level can be utilized to model potential environmental impacts, support decision-making processes aimed at mitigating these impacts, and ultimately reduce the intensive human footprint on nature.

Nature-based activities conducted in virtual environments have the potential to reduce physical pressure on natural ecosystems, thereby mitigating negative environmental impacts (Recreation expert from Lithuania). Virtual scenarios can be developed within metaverse platforms to assess potential environmental effects and generate ideas and recommendations aimed at their reduction. This process can support the formulation of environmental plans and policies (Software developer from Lithuania). Visualization of environmental processes through VR technologies is expected to enhance sensitivity and awareness among especially younger populations regarding environmental issues (non-governmental organization representative from Lithuania).

In this context, in the case of Lithuania, the implementation of metaverse applications for the public ensures that the majority of the population is familiar with and trained in digital applications. Experts indicate that virtual scenarios and simulations are not only used for educational purposes but also actively applied in environmental planning and policy development processes. In this process, governmental institutions and private sector collaborations provide infrastructure and content support, enhancing the effectiveness of these applications. In Turkey, however, metaverse applications are primarily focused on education and awareness, and the population’s familiarity with the applications is limited. Due to institutional support and infrastructure constraints, the level of comprehensive benefit is lower. This comparison demonstrates that the impact and applicability of metaverse applications vary according to the institutional and societal capacities of each country.

The perspectives of experts from Turkey and Lithuania regarding metaverse technologies fundamentally align with the goal of achieving a clean environment. However, notable differences emerge between the two countries concerning priorities and strategic approaches in implementation. In Turkey, there is a stronger emphasis on education, reflecting an individual-centered approach. Conversely, in Lithuania, the focus is more on systemic development, with metaverse technologies being integrated into planning and policy-making processes. This divergence can be attributed to differing national outlooks on technology transfer, as well as socio-cultural factors that influence the use of metaverse technologies for sustainable environmental objectives. Therefore, the deployment of next-generation technological infrastructures, such as the metaverse for sustainable environmental purposes, should be considered within the context of socio-political differences, and usage priorities should be tailored accordingly.

Experts participating in the study from Turkey and Lithuania were asked the question: “How can metaverse applications contribute to clean and safe environmental goals specifically within the leisure industry?” Based on the data obtained from the interviews, the main themes and sub-sub-themes that emerged are presented in

Table 4.

Table 4 presents four main themes identified through analyses based on expert opinions. The foremost theme is the reduction in physical space usage, which is anticipated to alleviate pressure on natural environments caused by high human activity. The second theme concerns safety and hygiene within metaverse environments, with digital platforms offering alternatives such as social distancing and public health considerations. The third theme is digital environmental education, wherein metaverse applications aim to enhance environmental awareness and foster environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors among individuals. The fourth and final theme involves the virtual testing of environmental practices, highlighting the use of metaverse technologies as a tool in environmental planning and policy-making processes.

These four emergent themes collectively demonstrate the multifaceted role of metaverse technologies as instruments for achieving clean and safe environmental objectives through the creation of virtual spaces within the leisure industry. To elucidate differences in the application of these themes, a detailed examination of both countries was conducted. Metaverse applications show variability in implementation due to societal, cultural, and administrative differences between the two countries. However, despite these differences, the applications are largely consistent. In terms of infrastructure and equipment, Lithuania appears to be ahead of Turkey, whereas in Turkey, the interest in technology creates a distinguishing factor.

Table 5 displays the distribution of themes by country, identifying similarities and differences, accompanied by a comparative evaluation.

Based on the perspectives of experts from both countries, it is understood that metaverse applications can contribute to achieving the goals of a “clean” and “safe” environment at various levels and dimensions. A key point emphasized in both Turkey and Lithuania is the reduction in pressure on natural environments caused by high levels of human participation. 90% of the experts from both countries emphasize that Metaverse technologies, along with other digital applications, should be utilized to mitigate the impact of intense human pressure. Visualizations created through virtual applications and VR technologies can help mitigate the degradation of forested areas and natural environments, while also facilitating the reduction in waste generation.

Through immersive applications developed within metaverse environments, degradation of natural habitats and pollution caused by waste can be decreased, thereby contributing to the proliferation of clean environmental settings (Academic from Turkey). Digital platforms have the potential to reduce mass gatherings and limit human participation, which can significantly decrease waste production. The expansion and wider adoption of such applications is necessary (Recreation expert from Turkey). The widespread use of metaverse technologies may be essential to reducing waste generation in real and natural settings, potentially supported by certain incentives (Recreation expert from Lithuania). Human-induced pressures are evident, as intense consumption leads to increased waste, disrupting ecological balance. To prevent this, digital platforms should be utilized more frequently (Academic from Lithuania).

In Turkey, the role of metaverse technologies is prominently characterized by concerns related to hygiene, health, and controlled leisure experiences. Particularly, issues such as public health, safety, and hygiene elevate the significance of digital platforms as opportunities to advance clean and safe environmental goals. In this context, it can be argued that the environmental contributions of metaverse technologies in Turkey are greater than initially anticipated, necessitating the implementation of appropriate measures.

Public health has gained heightened importance in recent years, especially during the pandemic period. It is essential to emphasize the need for technological support, as social distancing and enabling individuals to have secure and comfortable experiences are critically meaningful. Metaverse applications have the potential to facilitate these objectives (Public authority representative and non-governmental organization representative from Turkey).

In contrast, Lithuania adopts a different perspective. The use of metaverse technologies in Lithuania is envisioned primarily within the scope of environmental strategies and the development of plans and policies aimed at clean and safe environmental goals. Notably, monitoring of technical and administrative processes through simulations is emphasized. Experts highlight the testing of eco-friendly practices in digital environments prior to their implementation in real life. Furthermore, there is a pronounced approach towards integrating decision support systems into management processes for sustainable environmental objectives.

For instance, virtual scenarios can be developed to provide predictive experiences related to real-life contexts. Through VR technology, potential environmental degradations can be identified, enabling the formulation of realistic policies for the future. The world has now entered a new dimension with the integration of artificial intelligence (Software developer from Lithuania). I refer to this as impact modeling. The degradations occurring along my virtual route are detected and can be adapted to real life (non-governmental organization representative from Lithuania).

In both countries, metaverse technologies are anticipated to serve as educational tools to enhance environmental awareness, promote environmentally friendly attitudes and behaviors, and achieve meaningful change. Awareness can be elevated through the integration of technology, facilitating development and expansion from the individual to the societal level. Consequently, while individual health and hygiene concerns predominate in Turkey, Lithuania exhibits a perspective focused on technical and administrative processes, emphasizing the integration of metaverse technologies into management systems. Thus, the two countries demonstrate partially divergent approaches in leveraging metaverse technologies.

Experts participating in the study from Turkey and Lithuania were asked the question: “What challenges or limitations do you perceive in the use of these technologies for environmental purposes in the leisure sector?” Based on the data obtained from the interviews, the main themes and sub-themes that emerged are presented in

Table 6.

Table 6 presents five main themes identified through analyses based on expert opinions regarding the challenges and limitations encountered in the use of metaverse technologies for environmental purposes within the leisure sector.

The first prominent theme is Access and Digital Inequality. In particular, the lack of adequate infrastructure for metaverse technologies becomes more pronounced as one moves from urban centers toward rural areas, thereby exacerbating inequality. While 90% of the experts from Turkey emphasized the lack of infrastructure, nearly 100% stated that this deficiency is felt most strongly in rural areas. The second theme concerns User Participation and Lack of Awareness, where insufficient engagement with content related to the environment and sustainability is recognized as a fundamental issue. Moreover, 80% of the experts indicated that adequate hardware and software are also lacking. The third theme relates to Technical and Economic Constraints, as metaverse technologies involve certain costs both in terms of infrastructure and equipment, which limit their usage. The fourth theme addresses Social and Cultural Acceptance Issues, highlighting concerns that virtual experiences may diminish the sense of reality and act as a barrier to social interaction. The fifth and final theme encompasses Ethical Concerns and Energy Consumption. While data security and user privacy raise ethical questions, the high energy demands of digital platforms are considered an additional challenge. Notably, 90% of the experts from Lithuania pointed out that ethical concerns and disruptions in technical processes are significant. Furthermore, 85% of the experts highlighted major concerns regarding data storage and processing. In this context, when evaluating the opportunities and challenges in Turkey and Lithuania, it is observed that in Turkey, the emphasis is placed more on deficiencies in technical infrastructure, hardware, and software, whereas in Lithuania, ethical concerns and anxieties are more pronounced. In Turkey, the allocation of adequate budgets and the establishment of a nationwide digital infrastructure could contribute to reducing digital inequality. In Lithuania, however, strict legal regulations are envisaged to address ethical concerns related to data processing and sharing.

To elucidate differences in the application of these themes, a detailed examination of both countries was conducted.

Table 7 displays the distribution of the themes by country, highlighting similarities and differences, and providing a comparative evaluation.

Findings derived from expert opinions in both countries indicate that significant barriers and limitations exist in the use of metaverse technologies to achieve clean and safe environmental goals in Turkey and Lithuania. However, the nature of these barriers and limitations appears to be shaped by the structural, cultural, and technological differences inherent to each country.

In Turkey, experts primarily emphasize the insufficiency of adequate infrastructure for metaverse technologies, with this deficiency being more pronounced in rural areas. Additionally, considerable challenges are reported regarding the procurement of necessary equipment and hardware. It can be asserted that while technological and digital transformation are expanding nationwide in Turkey, their distribution remains uneven. Another issue stemming from the lack of infrastructure is insufficient interest and awareness. Experts particularly highlight that infrastructural deficiencies in Turkey contribute to a lack of engagement and awareness among users.

Investment in digital technologies necessitates the strengthening of infrastructure, which is currently quite limited and insufficient. Additionally, the procurement of hardware and equipment is required. According to a non-governmental organization representative from Turkey, this constitutes the most critical issue. Technical infrastructure is notably expensive and should be prioritized in investment planning. Given that much of the equipment is indexed to foreign currency, persistent price increases are expected, making it unsurprising that the infrastructure has not yet reached the desired level (Software developer from Turkey). In fact, there is not yet a fully established demand or interest in the metaverse; limited accessibility always and locations leads to waning public engagement over time. This is a process, and capturing the interest of younger generations is especially important, as the world is increasingly functioning as a digital platform (Academic from Turkey).

In contrast to Turkey, Lithuania’s concerns emphasize systemic issues, ethical violations, and technical processes. Particularly, data security and the protection of user information are highly prioritized due to intensive platform usage. Furthermore, the widespread use of digital platforms entails high energy consumption, raising cost concerns. In addition to financial costs, high energy consumption may generate adverse environmental impacts (e.g., increased carbon footprint), potentially conflicting with clean environment objectives.

Ensuring the security of user data is a critically important issue, which also raises ethical concerns. Appropriate sensitivity must be demonstrated in this regard (Public authority representative and academic from Lithuania). If the objective is a clean environment, high energy consumption will result in both financial and environmental costs, presenting a contradiction. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider alternative energy sources (non-governmental organization representative and software developer from Lithuania). Even if the cost remains the same, clean energy sources aimed at reducing negative environmental impacts should be considered. Solar and wind energy sources can be preferred. At the same time, these energy sources are not only clean but can also provide long-term budget savings (Software developer from Lithuania).

Beyond various challenges and limitations, a shared concern for both countries is that virtual environments in the metaverse lack the authenticity of real-life experiences. This negatively affects social acceptance and satisfaction. Additionally, due to limited socialization and interaction, it can be argued that individuals occasionally choose to deliberately distance themselves from these digital platforms.

Recreational activities conducted in forested areas provide individuals with social environments where communication and interaction take place. However, digital platforms inherently restrict this communication (Recreation expert from Turkey). Particularly for young people, the need for socialization is best met through recreational activities; the benefits derived from these activities may not be fully replicable within metaverse environments (Recreation expert from Lithuania).

In conclusion, while infrastructure, equipment deficiencies, and unequal technological distribution constitute major limitations in Turkey, ethical concerns and administrative and systemic constraints are predominant in Lithuania. Nonetheless, concerns regarding the limitation of communication, socialization, and interaction emerge as a common challenge in both countries. Economic, cultural, and administrative differences further accentuate variations in how these challenges and limitations are perceived by each country.

Experts participating in the study from Turkey and Lithuania were asked the question: “Considering the cases of Turkey and Lithuania, what similarities or differences do you observe in the use of metaverse technologies?” Based on the data obtained from the interviews, the main themes and sub-themes that emerged are presented in

Table 8.

Table 8 provides a comparative summary of the areas of use and usage habits of metaverse technologies in Turkey and Lithuania. According to the content analysis results, four main themes related to differences in metaverse technology use between the two countries have been identified.

The first theme pertains to differences in usage purposes. In Turkey, metaverse technologies are predominantly employed for gaming, entertainment, and marketing, whereas in Lithuania, their use is primarily oriented toward education and environmental planning. The theme of strategic and institutional approaches reveals that Turkey has not yet reached an adequate level, with institutional processes insufficiently integrated with metaverse technologies. Conversely, in Lithuania, the use of metaverse technologies within public institutions’ management processes is increasingly widespread.

The third theme concerns digital infrastructure and preparedness, which is more established in Lithuania. Notably, there is greater digital platform literacy and usage readiness in Lithuania. In Turkey, technical and infrastructural deficiencies appear to restrict the utilization of metaverse technologies. The fourth and final theme addresses local content and production capacity. While publicly supported content production is increasingly common in Lithuania, production processes in Turkey remain limited and lack public support.

Alongside the differences observed in practice, the similarities emerging in both countries can be summarized as follows. Usage is aligned with institutional and strategic objectives. Additionally, both countries exhibit similar approaches in terms of local content preparation and production. In particular, it can be stated that the purposes related to the use of Metaverse technologies for social awareness and education are similar.

To elucidate differences in the application of these themes, a detailed examination of both countries was conducted.

Table 9 presents the distribution of themes by country, highlighting similarities and differences, and providing a comparative evaluation.

Findings based on expert opinions from both countries indicate a clear divergence in the purposes and modalities of metaverse technology use between Turkey and Lithuania. While awareness of digital platforms and metaverse technologies is increasing in both countries, significant differences emerge with respect to usage purposes, expectations, strategies, content production, and infrastructural preparedness.

Primarily, in Turkey, the use of metaverse technologies is concentrated on economic, entertainment, and promotional objectives, whereas in Lithuania, these technologies are predominantly employed for educational purposes, environmental sustainability practices, and the development of plans and policies. This divergence can be attributed to differences in national vision and policy frameworks.

In Turkey, metaverse and similar digital platforms are primarily preferred for gaming and entertainment, particularly among younger populations (Academic from Turkey). It is apparent that metaverse technologies in Turkey do not target environmental or natural issues; rather, they are utilized mainly for commercial purposes and revenue generation (non-governmental organization representative from Turkey). Although the gaming and entertainment sectors do employ metaverse technologies, their use is limited to entertainment rather than educational functions, which remain largely absent in Turkey (Recreation expert from Turkey). Conversely, Lithuania has successfully integrated metaverse technologies into education, including environmental education (Academic from Lithuania). I personally experienced this in an educational program, where a simulation was developed to demonstrate environmental degradation. It was very impactful and realistic. The use of metaverse tools for education is becoming increasingly widespread in Lithuania (Public authority representative from Lithuania).

In terms of strategic and institutional approaches, Lithuania has made considerably more significant advances compared to Turkey. For instance, 2 experts from Lithuania, corresponding to 70%, emphasized the role of public support and EU-based legal and financial advantages, whereas only 2 experts from Turkey, corresponding to 70%, highlighted public support and institutional facilitation. This indicates a 70-percentage-point difference between the two countries, reflecting Lithuania’s stronger perception of public support as a critical factor in advancing digitalization. Lithuania, particularly due to EU legal frameworks, has significant advantages based on legal and financial support.

Several public institutions in Lithuania have begun integrating various digital platforms, including the metaverse, into public policies. Particularly with the assistance of public funding, institutions have accelerated the integration process (Public authority representative from Lithuania). Supported by societal endorsement, these institutions have begun facilitating technology transfer. The existing infrastructure is also conducive to this and offers diverse opportunities (non-governmental organization representative from Lithuania). In contrast, the use of metaverse technologies at the public institution level in Turkey is virtually nonexistent. While technological equipment use is widespread in institutions, it remains below the desired level (Academic from Turkey). I have neither encountered nor observed any applications of metaverse technologies in Turkey. Although it may be considered in the long term, the current utilization of such technologies is negligible. Efforts are being made to provide support, but first, the infrastructure must be adequately developed (Recreation expert from Turkey).

When evaluated in terms of digital infrastructure, readiness, and content production capacity, Lithuania is in a significantly better position compared to Turkey, creating a noticeable gap in the utilization of metaverse technologies. Experts from Lithuania indicate that the society is both willing and inclined to use metaverse technologies, which consequently provides advantages in content creation and diversity. Conversely, experts in Turkey highlight societal reluctance and insufficient demand as factors diminishing interest in metaverse technologies, resulting in very limited content production.

In Lithuania, particularly among young people, there is strong readiness and demand for utilizing metaverse and other digital platforms, a situation attributed in part to robust infrastructure (Software developer from Lithuania). Content quantity and variety are increasing with ongoing initiatives. “I have experienced many VR applications and we possess incredible content. Public support and private sector collaboration should advance hand in hand in this regard” (Public authority representative from Lithuania). In Turkey, the primary issue is infrastructure. Due to insufficient network and connectivity, access is limited, which significantly restricts the use of metaverse technologies. “Programmers and developers should be supported, and of course, infrastructure must be strengthened” (Software developer from Turkey). “There is no demand. This is the most critical barrier. Demand and interest must be increased; without these, attracting investments becomes very difficult” (non-governmental organization representative from Turkey). Content production is limited and mostly focused on gaming and entertainment, which further restricts usage. “The entire process should be managed collectively: infrastructure, public support, and private sector. Without cooperation, progress is impossible” (Academic from Turkey).

Based on the identified themes and sub-themes, Lithuania is considerably ahead of Turkey in the use and dissemination of metaverse technologies. This is especially evident in societal acceptance and the concurrent increase and diversification of content production. In contrast, Turkey experiences limited content production due to low demand and willingness. Combined with insufficient infrastructure and public support, the development and widespread adoption of metaverse technologies in Turkey may require considerable time.

Experts participating in the study from Turkey and Lithuania were asked the question: “What steps should be taken to enhance the contribution of metaverse technologies to environmental sustainability in the leisure sector?” Based on the data obtained from the interviews, the main themes and sub-themes that emerged are presented in

Table 10.

Table 10 summarizes six (6) main themes and their sub-themes derived from the expert opinions in Turkey and Lithuania regarding the necessary steps to enhance the contribution of metaverse technologies to environmental sustainability.

The first theme, environmental education and awareness, emphasizes the need to increase educational content within metaverse technologies. The second theme, public integration, highlights institutional support and the digital integration of metaverse technologies into organizational processes. The third theme, technological investment and energy efficiency, points to the transfer of locally appropriate and clean technologies in alignment with environmental objectives specific to each country. The fourth theme, participatory design and gamification, refers to the inclusion of metaverse users in the development process and the creation of an interactive experience. The fifth theme, linking virtual and real-world behaviors, stresses the importance of translating environmentally friendly behaviors experienced in virtual environments into real-life practices.

To elucidate the differences in the practical application of the identified themes, a detailed examination of both countries was conducted.

Table 11 presents the distribution of themes by country, highlighting similarities and differences, and providing a comparative evaluation.

Table 11 presents the perspectives of experts from Turkey and Lithuania regarding the enhancement of the contribution of metaverse technologies to clean and safe environmental goals. In both countries, the themes of environmental education and awareness, public integration, and technological investment/energy efficiency emerge as common points emphasized by the experts. This consensus reflects a shared outlook that metaverse technologies can support environmental sustainability objectives through the establishment of digital platforms for education, institutional backing, technological infrastructure development, and technology transfer.

There is a recognized need to develop and expand educational content within metaverse technologies focused on environmental education and behavioral change. In Turkey, this area is considerably underdeveloped and requires focused attention (Academic from Turkey). Rising energy costs necessitate the preference for local and low-cost energy sources, along with increased use of metaverse and other digital platforms (Software developer from Turkey). Given the high energy demands of metaverse technologies, energy-efficient coding practices should be adopted (Software developer from Lithuania). Particularly in Lithuania, environmental education should be transferred to virtual environments in schools, thereby reaching a larger number of youth and students and increasing awareness among young populations (Recreation expert and Academic from Lithuania).

Alongside shared opinions and ideas, there are points of divergence between experts from the two countries. In Turkey, the theme of gamification and user participation stands out, reflecting a user-centered approach prevalent in the country. Conversely, in Lithuania, themes such as linking virtual experiences with real environmental behaviors and multi-stakeholder collaboration gain prominence. This indicates a more institutionalized and system-oriented approach toward metaverse technologies in Lithuania.

In Turkey, the widespread adoption of metaverse technologies requires greater emphasis on factors such as gaming, socialization, and communication (non-governmental organization representative from Turkey). In Lithuania, the use of metaverse and other digital platforms is already widespread. However, a key point to highlight is the need to establish a connection between virtual experiences and the real world, enabling impact assessment (non-governmental organization representative from Lithuania). Technological advancement does not progress solely through public sector support; a multi-stakeholder approach is necessary, with particular emphasis on increasing private sector incentives (Public authority representative from Lithuania).

An evaluation of the use and dissemination of metaverse technologies in Turkey and Lithuania has been attempted, considering the priorities and objectives of each country. It is apparent that technological infrastructure and investment differences distinctly separate the two nations. Additionally, social, cultural, and political approaches contribute to these distinctions. Therefore, the interpretation and assessment of the findings call for a multidimensional analysis that considers the specific characteristics of each country.

4. Discussion

Leisure activities play a significant role in the protection and enhancement of individuals’ and communities’ social and physical health. These activities also facilitate increased communication and interaction among individuals [

84,

85]. However, the growing demand for leisure activities, particularly those held in forested areas, brings with it negative environmental consequences. The use of metaverse technologies to mitigate these adverse environmental impacts may influence environmental awareness and contribute to the achievement of sustainable environmental goals.

Beyond presenting cross-country insights, the findings of this study also engage in a meaningful theoretical conversation with the three conceptual lenses used to frame the research. Interpreted through the lens of Digital Transformation Theory, the different trajectories observed in Turkey and Lithuania suggest that technology adoption is not merely a matter of innovation availability, but also of institutional preparedness and socio-technical alignment. When viewed through Diffusion of Innovations Theory, it becomes evident that perceived usefulness and institutional endorsement play a significant role in shaping the willingness to adopt metaverse-based sustainability practices. Finally, an Institutional Theory perspective reveals that regulatory expectations, legitimacy-seeking behavior, and path-dependent policy cultures shape the extent to which technological imaginaries can translate into actual environmental action. Taken together, these insights illustrate that metaverse-driven sustainability transitions should not be understood solely as a technological shift but rather as a layered institutional process negotiated through policy, governance, and cultural dynamics.

In this context, the present study focuses on evaluating the potential of metaverse technologies to achieve clean and safe environmental objectives within the leisure sector, based on the cases of Turkey and Lithuania. Furthermore, it aims to comparatively analyze the perceptions and opinions of various stakeholders and experts regarding the subject. The findings obtained from interviews with experts from both countries are discussed, considering the existing literature, and presented to the reader.

Experts from Turkey and Lithuania demonstrate a high level of general acceptance of metaverse technologies and assess their potential for environmental sustainability from a multidimensional perspective. Specialists from both countries concur with the use of metaverse technologies as an educational tool to raise societal awareness for sustainable environmental goals. In Turkey, beyond their use in education and awareness activities, metaverse technologies are also emphasized as a tool for mass communication implemented through public institutions. In contrast, experts in Lithuania foresee the use of metaverse technologies as a platform for creating scenarios during the preparation of environmental planning, plans, and policies.

Metaverse technologies can contribute to societal awareness by offering interactive educational opportunities. Through educational content created in simulation environments, individuals can directly experience negative environmental impacts and their consequences. Consequently, participants may be motivated to adopt a sustainable environmental mindset and develop environmentally friendly behaviors. In addition, promotional activities targeting sustainable environmental practices can be conducted. Interactive environments can be established to support safe and clean environmental goals, thereby contributing to the achievement of these objectives. Research indicates that environmentally focused education simulated through metaverse technologies enhances student engagement and reinforces the development of eco-friendly behaviors. This allows individuals to take an active interest in environmental sustainability and to test comprehensive experiential learning scenarios [

86].

The use of metaverse technologies, particularly in forested areas, is becoming increasingly prevalent for achieving clean and safe environmental objectives. These technologies enable the reduction in natural resource consumption through the analysis of acquired data. Furthermore, they serve as innovative tools in sustainable environmental management. In particular, the capability for real-time data collection and processing provides significant advantages for decision-makers [

87]. The technological affinity among young people can notably contribute to raising environmental awareness. Recent studies have highlighted that metaverse technologies play a critical role in enhancing environmental awareness and fostering social consciousness [

88,

89,

90,

91]. Simulations created within metaverse technologies and VR platforms have the potential to influence this awareness. Through experiences gained in virtual environments, individuals can foresee environmental degradation and pollution caused by human activities, thereby increasing awareness [

92,

93]. Moreover, the experiential nature of virtual environments may facilitate the retention of knowledge and insights related to environmental issues [

94,

95]. Through simulations and virtual environments, it is possible to develop positive attitudes toward the natural environment and foster individual behavioral change in the protection of one’s surroundings [

96].

Both countries, metaverse technologies are regarded as tools for education and awareness-raising; however, in Turkey, their use as a mass communication tool is particularly emphasized [

97]. It is suggested that metaverse and other digital platforms can be employed to disseminate information regarding environmental problems to the public. As noted earlier, these technologies are not only valuable for educational purposes but can also be preferred in mass communication processes aimed at enhancing societal awareness and information sharing [

98,

99]. The emphasis on metaverse technologies as a mass communication tool in Turkey can be associated with a societal need to inform the public about environmental degradation. In Lithuania, however, metaverse technologies are not only regarded as educational tools but are also positioned as decision-support systems in the preparation of environmental plans and policies [

100]. This position reflects a more strategy-oriented perspective. Technology is conceptualized as a support system that facilitates the consideration of multiple factors through testing various scenarios in virtual environments. It can be expressed as a support system that contributes to the consideration of multiple factors, depending on the testing of different scenarios in virtual environments. Therefore, through virtual simulations, plans and policies can be prepared for unfavorable environmental forecasts, comprehensive assessments can be made, and managers’ decision-making processes can be supported [

101]. This approach, emerging in Lithuania, can be interpreted as the integration of technology transfer into management processes and aligned with institutional vision [

102,

103].

Based on the perspectives of experts from both countries, it is understood that metaverse applications can contribute to achieving “clean” and “safe” environmental goals at various levels and dimensions. A key point emphasized in both Turkey and Lithuania is the reduction in pressure on the natural environment caused by high human participation. In Turkey, the role of metaverse technologies is notably associated with hygiene, health, and controlled leisure experiences. In contrast, Lithuania presents a different perspective. The use of metaverse technologies in Lithuania for clean and safe environmental objectives is envisioned primarily as a tool for the development of environmental strategies, plans, and policies. While individual health and hygiene concerns are more prominent in Turkey, Lithuania emphasizes a management-oriented approach that integrates metaverse technologies into technical and administrative processes. Consequently, the two countries exhibit partially distinct orientations regarding the utilization of metaverse technologies.

Table 12 below presents the primary metaverse applications in both countries, along with the challenges that hinder the widespread adoption of these applications.

Experts from Turkey and Lithuania indicate that metaverse technologies can contribute at various levels to achieving clean and safe environmental goals, particularly during recreation activities conducted in forested areas. It is emphasized in both countries that the use of digital infrastructure can reduce human pressure on the natural environment. In Turkey, the utilization of metaverse technologies is interpreted as a risk-free extension of the natural environment. The social and environmental health concerns arising especially after recent epidemics and pandemics have been instrumental in promoting this perspective [

104,

105,

106,

107]. In contrast to Turkey, Lithuania demonstrates a more institutional approach to the use of metaverse technologies, integrating them into environmental planning and policy processes. Indeed, recent studies have shown that the use of metaverse technologies to support institutional frameworks has become increasingly widespread [

108,

109,

110,

111]. It can be stated that management processes are particularly supported through long-term scenarios. Especially in Lithuania, owing to its advanced digital infrastructure, metaverse technologies and other digital platforms are preferred as institutional and administrative tools. Metaverse platforms can make significant contributions to corporate governance processes, particularly in the development of plans and policies related to the natural environment. Data sets and virtual environmental experiences can provide a valuable foundation for shaping these plans and policies [

112].

The findings derived from expert opinions in both countries indicate that significant barriers and limitations exist regarding the use of metaverse technologies to achieve clean and safe environmental goals in Turkey and Lithuania. In Turkey, the most frequently emphasized issue among experts is the lack of adequate infrastructure for metaverse technologies, with this deficiency being more pronounced in rural areas. Significant challenges are also encountered in the provision of necessary equipment and devices.

The digitalization process and the use of technologies such as the metaverse may require a strong infrastructure and homogeneous distribution. This would enable every individual to have direct access to these digital platforms. As a result, attitude and behavior change can be fostered, and environmental awareness can be enhanced [

113,

114]. These shortcomings particularly contribute to reduced utilization of metaverse technologies in rural regions, thereby widening the gap between urban and rural areas. This situation considerably constrains digital transformation and technology transfer [

115,

116]. Notably, a robust internet infrastructure, along with adequate technical equipment and devices, is critical for the use and proliferation of advanced digital platforms such as the metaverse [

117,

118,

119,

120]. The findings indicate that in Turkey, the use of metaverse technologies and other digital platforms is concentrated primarily in urban areas, and technology transfer has yet to achieve a homogeneous structure. In contrast to Turkey, Lithuania places greater emphasis on systemic concerns, ethical violations, and technical processes. Particularly due to extensive usage, both data security and the protection of users’ personal information are highlighted as critical issues. Large datasets are currently processed on digital platforms, and the safeguarding and storage of this data present significant security challenges. The most significant concern regarding the use of metaverse technologies is ethical issues and data privacy. Protecting and storing data belonging to thousands of individuals or institutions constitutes a major responsibility. This responsibility also influences the level of acceptance of metaverse technologies [

121]. Additionally, the protection of millions of users’ personal data represents the ethical dimension of this process. These factors increase the limitations on the use of metaverse technologies and fuel concerns regarding their deployment [

122,

123,

124]. The constraints on metaverse technology usage differ between the two countries. This difference can be interpreted not only in relation to technological infrastructure but also through consideration of socio-cultural and institutional variables.

The results obtained from expert opinions in both countries indicate that the purposes and forms of metaverse technology usage differ between Turkey and Lithuania. A significant difference is observed between the two countries regarding the objectives of using these technologies. In Turkey, the use of metaverse technologies primarily focuses on economic, entertainment-based, and promotional activities. The growth of the digital gaming industry and its global acceptance have contributed to its widespread popularity among young people. It is well known that the younger population frequently engages with metaverse platforms, particularly within the gaming sector. These gaming and entertainment platforms also play a key role in shaping interactions within social networks [

125]. Metaverse and other digital platforms are also preferred due to their provision of entertainment-oriented experiences. Moreover, advertising and promotional activities through digital games are extensive, attracting the interest of both youth and private sector representatives. The migration of brand awareness and advertising campaigns to digital platforms further substantiates this trend [

126,

127,

128].

In contrast to Turkey, Lithuania favors the use of metaverse technologies for education, environmental sustainability applications, and the development of plans and policies. A strong digital infrastructure enables the use of metaverse technologies across various fields. Primarily utilized in education, metaverse technologies play a significant role in raising awareness and promoting environmental education [

129]. From an institutional perspective, scenarios created within metaverse environments can facilitate management processes and support decision-makers in their decision-making. This, in turn, can accelerate digital transformation by enabling technology transfer in governance [

130,

131,

132,

133]. Especially in the preparation of policies aimed at the protection and sustainable management of forested areas, digital tools can be effectively utilized [

134].

According to experts from Turkey and Lithuania, opinions regarding the enhancement of metaverse technologies’ contributions to clean and safe environmental goals, three common themes emerge: environmental education and awareness, public integration, and technological investment/energy efficiency. Experts suggest that the use of metaverse technologies should not be limited to education alone but can also be envisaged as a tool for fostering social consciousness and awareness [

135]. Through this, the experiences acquired in virtual environments can be transformed into collective social movements [

136]. Considering the high energy demand of digital platforms, a focus on sustainable and clean energy sources aligns with the objectives of a safe and clean environment. Otherwise, excessive energy consumption may cause adverse effects on the natural environment and contribute to an increased carbon footprint [

137,

138,

139,

140]. In this context, despite structural differences, the multifaceted use of metaverse technologies is broadly accepted in both countries.

Building on the comparative insights discussed above, it is also important to critically reflect on the scope and boundaries of the present study and to situate its contributions within the broader theoretical landscape. While this research offers a valuable perspective on the potential of metaverse technologies to support environmental sustainability in the leisure sector, several limitations should be acknowledged to contextualize the findings more clearly through the lenses of Technology Adoption Theory [

53], Institutional Theory [

141] and digital transformation scholarship [

142,

143].

First, the study is limited to two national cases—Turkey and Lithuania. Although this focused comparison provides depth, it also reflects institutional and socio-technical conditions particular to these contexts. As emphasized by Institutional Theory, technology trajectories are shaped not only by innovation potential but also by policy legacies, legitimacy pressures, and governance cultures. Future studies could therefore benefit from incorporating cases with contrasting institutional logics and regulatory regimes to capture a broader spectrum of isomorphic pressures and adaptive capacities.

Second, while the qualitative design enables a rich interpretation of expert narratives, it necessarily embeds the research process within the interpretive framework of the interviewer. From the perspective of interpretivist methodology, researcher positionality may influence how innovation cues are framed and how institutional resistance or acceptance is narrated. Acknowledging these interpretive dynamics aligns with calls in digital transformation literature for reflexive engagement with socio-technical imaginaries rather than purely instrumental readings of technological adoption.

Finally, although qualitative inquiry does not seek statistical representativeness, the clustering of participants with similar institutional backgrounds may have constrained the plurality of innovation imaginaries and adoption narratives. Given that Diffusion of Innovations Theory highlights the role of heterogeneous actor networks in shaping adoption pathways, future research could strategically include community-level stakeholders, operational field actors, and end-users to better capture the distributed agency involved in metaverse-enabled environmental engagement.