The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify the dimensions of how rural tourism changes villagers.

- To develop and validate a scale for measuring the impact of tourism on villagers.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Villager-Centered Theories and Scale Development

2.2. Dimensions of Tourism’s Impact on Villagers

3. Method and Results

3.1. Selection of Sample Villages

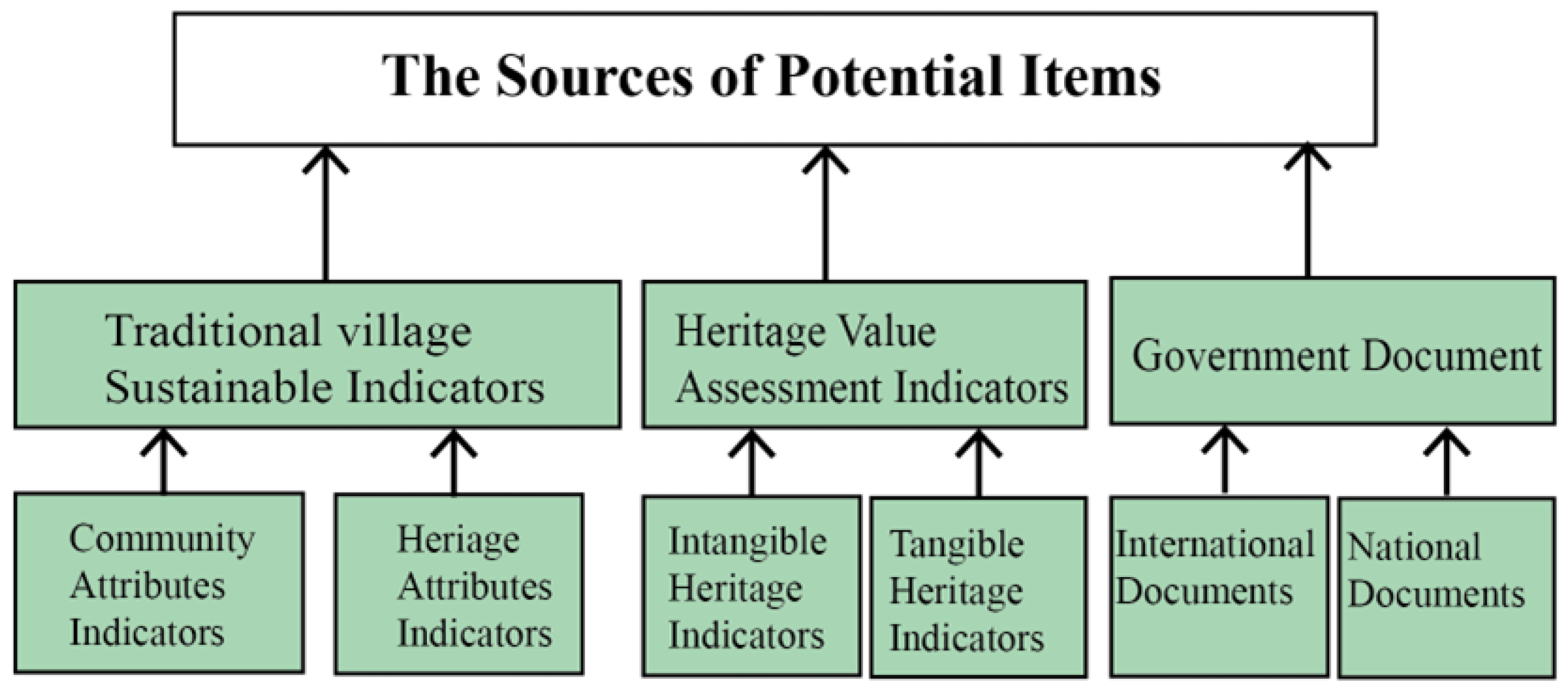

3.2. Identifying Potential Items

- Do you feel that tourism has a significant impact on you?

- What are the specific manifestations of tourism’s impact on your economy, culture, and social life?

- Beyond the points mentioned above, do you have any other opinions or views on tourism development that you would like to share?

3.3. Scale Refinement

3.3.1. Content Validity

3.3.2. Pre-Survey

3.4. Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA)

3.5. Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA)

3.6. Criterion Validity

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Jiang, J.; Xu, S.; Guo, Y. Community Participation and Residents’ Support for Tourism Development in Ancient Villages: The Mediating Role of Perceptions of Conflicts in the Tourism Community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Study on the Evaluation of World Cultural Heritage Value of Traditional Villages in China. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. 2021, 42, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.; Yue, K.; Zhang, X. Ignored Opinions: Villager-Satisfaction-Based Evaluation Method of Tourism Village Development—A Case Study of Two Villages in China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunikawati, N.A.; Istiqomah, N.; Priambodo, M.P.; Sidi, F. Can Community Based Tourism (Cbt) Support Sustainable Tourism in the Osing Traditional Village? In Proceedings of the IConARD, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–14 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of Destination Social Responsibility and Tourism Impacts on Residents’ Support for Tourism and Perceived Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, B. Revitalizing Traditional Villages through Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A. How Has Rural Tourism Influenced the Sustainable Development of Traditional Villages? A Systematic Literature Review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25627. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Lv, Q. Multi-Dimensional Hollowing Characteristics of Traditional Villages and Its Influence Mechanism Based on the Micro-Scale: A Case Study of Dongcun Village in Suzhou, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 101, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gocer, O.; Shrestha, P.; Boyacioglu, D.; Gocer, K.; Karahan, E. Rural Gentrification of the Ancient City of Assos (Behramkale) in Turkey. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 87, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Zhao, M.; Ge, Q.; Kong, Q. Changes in Land Use of a Village Driven by over 25 Years of Tourism: The Case of Gougezhuang Village, China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, C.; Wang, H.; Gao, Y. Evolution and Reconstruction of Settlement Space in Tourist Islands: A Case Study of Dachangshan Island, Changhai County. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 9777–9808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keran, C.; Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Tian, Y. Construction and Characteristic Analysis of Landscape Gene Maps of Traditional Villages Along Ancient Qin-Shu Roads, Western China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.; Sun, Y.; Min, Q.; Jiao, W. A Community Livelihood Approach to Agricultural Heritage System Conservation and Tourism Development: Xuanhua Grape Garden Urban Agricultural Heritage Site, Hebei Province of China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for Cultural Heritage Tourism. In The 2022 ICOMOS Annual General Assembly; ICOMOS: Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Cultural Tourism Charter: Managing Tourism at Places of Heritage Significance. In Proceedings of the 12th General Assembly, Mexico City, Mexico, 17–23 October 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Y.; Wang, C. Understanding the Relationship between Tourists’ Perceptions of the Authenticity of Traditional Village Cultural Landscapes and Behavioural Intentions, Mediated by Memorable Tourism Experiences and Place Attachment. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2023, 28, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.F.; Li, Z.W. Destination Authenticity, Place Attachment and Loyalty: Evaluating Tourist Experiences at Traditional Villages. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 26, 3887–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.Y.; Xi, X.S. Vernacular Landscape Leading the Way: The Holistic Protection and Revival of Hani’s Ancient Village under the Background of Yuanyang Terraced Fields’ Register on the World Heritage. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 1030–1032, 2468–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferwati, M.S.; El-Menshawy, S.; Mohamed, M.E.A.; Ferwati, S.; Al Nuami, F. Revitalising Abandoned Heritage Villages: The Case of Tinbak, Qatar. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2021, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, E.A.; Arslan, T.V.; Durak, S. Physical Changes in World Heritage Sites under the Pressure of Tourism: The Case of Cumalikizik Village in Bursa. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 8, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M. The Estonian Open-Air Museum and the Mode and Experience of the Protection of Its Vernacular Architecture. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. 2015, 51, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, J.-H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Chen, M. Development and Validation of a Tourism Fatigue Scale. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Hu, Y.; Cao, C. The Urbanization Process Should Promote the Conservation and Development of Traditional Villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 2013, 21, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. The Stripping and Integrating Study of Heritage Community–Historical and Cultural Villages: Culture Tourism Sustainable Development; Northwest University: Kirkland, WA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. Construction and Empirical Research on the Evaluation System of Sustainable Development of Chinese Traditional Villages. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2021, 76, 921–938. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Wang, S. Construction on Evaluation System of Sustainable Development Forrural Tourism Destinations Based on Rural Revitalization Strategy. Geogr. Res. 2022, 41, 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.S.; Zhang, J.; Tian, F.J. Community Leadership in Rural Tourism Development: A Tale of Two Ancient Chinese Villages. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, K.; Mao, Z.Q. Community Building Showing the Potential Value of Country: Japan’s Charming Country Construction Experience. Urban Dev. Stud 2016, 1, 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wanner, A.; Pröbstl-Haider, U. Barriers to Stakeholder Involvement in Sustainable Rural Tourism Development—Experiences from Southeast Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonwanno, S.; Laeheem, K.; Hunt, B. Takua Pa Old Town: Potential for Resource Development of Community-Based Cultural Tourism Management. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 43, 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Handler, R.; Saxton, W. Dyssimulation: Reflexivity, Narrative, and the Quest for Authenticity in “Living History”. Cult. Anthropol. 1988, 3, 242–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaryan, A. Proposals on Nomenclature, Functional Orientation and Territorial Zoning of the Armenian People’s Ethnographic Parks. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 913, 032030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.M.; Zhu, C.S.; Fong, L.H.N. Exploring Residents’ Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Sustainable Tourism Development in Traditional Villages: The Lens of Stakeholder Theory. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China (MHURDC). The Evaluation and Identification Index System of Traditional Villages (Trial); Ministry of Culture Tourism of the People’s Republic of China, National Cultural Heritage Administration, Ministry of Finance of the People’s Republic of China, Eds.; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- MHURDC. Evaluation Index System of China’s Famous Historical and Cultural Towns (Villages) (Trial); Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2005.

- Ma, J.; Shu, B. 30 Years of Rural Tourism in China: Policy Orientation, Reflection and Optimization. Mod. Econ. Res. 2020, 27, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Xu, K. Tourism-Induced Livelihood Changes at Mount Sanqingshan World Heritage Site, China. Environ. Manag. 2016, 57, 1024–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckermann, C. Trading on Tradition: Tourism, Ritual, and Capitalism in a Chinese Village. Mod. China 2016, 42, 188–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Q. A Phenomenological Explication of Guanxi in Rural Tourism Management: A Case Study of a Village in China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, G.; Yang, Q. The Spatial Production of Rural Settlements as Rural Homestays in the Context of Rural Revitalization: Evidence from a Rural Tourism Experiment in a Chinese Village. Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, W.; Alarcón, S. How Can Rural Tourism Be Sustainable? A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Wang, R.; Dai, M.L.; Ou, Y.H. The Influence of Culture on the Sustainable Livelihoods of Households in Rural Tourism Destinations. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1235–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, H. Post-Renewal Evaluation of an Urbanized Village with Cultural Resources Based on Multi Public Satisfaction: A Case Study of Nantou Ancient City in Shenzhen. Land 2023, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Martellozzo, F. Is Rural Rural Tourism-Induced Built-up Growth a Threat for the Sustainability of Rural Areas? The Case Study of Tuscany. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Feldman, M.W.; Li, S. The Status of Perceived Community Resilience in Transitional Rural Society: An Empirical Study from Central China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.X.; Li, B.H. Rethinking Cultural Creativity and Tourism Resilience in the Post-Pandemic Era in Chinese Traditional Villages. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.T. Tourism and Identity Transformation in the Oeam Folk Village in Asan, Korea. Korea J. 2012, 52, 136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Yan, Y.; Ying, Z.; Zhou, L. Measuring Villagers’ Perceptions of Changes in the Landscape Values of Traditional Villages. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rypkema, D.; Cheong, C. Measurements and Indicators of Heritage as Development. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 17th General Assembly, Paris, France, 27 November–2 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, X.P.; Yao, Y.; Li, J. Sociocultural Impacts of Tourism on Residents of World Cultural Heritage Sites in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.G.; Huang, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.F. Tourism Development and Local Borders in Ancient Villages in China. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korani, Z.; Shafiei, Z. In Search of Traces of ‘the Tourist Gaze’ on Locals: An Ethnographic Study in Garmeh Village, Iran. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2021, 19, 549–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H. Involution of Tradition and Existential Authenticity of the Resident Group in Nyuh-Kuning Village. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2022, 20, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, J.; Kozak, R.; Jin, M.; Innes, J.L. How Do Conservation and the Tourism Industry Affect Local Livelihoods? A Comparative Study of Two Nature Reserves in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S. Ten Steps in Scale Development and Reporting: A Guide for Researchers. Commun. Methods Meas. 2018, 12, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeVellis, R.F.; Thorpe, C.T. Scale Development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I.A.; Wan, Y.K.P. A Systematic Approach to Scale Development in Tourist Shopping Satisfaction: Linking Destination Attributes and Shopping Experience. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hou, S. Review on the Research of the Ancient Village Protection and Development. In Proceedings of the 2015 2nd International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Intercultural Communication, Kaifeng, China, 7–8 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.; Wang, C.; Xu, T.; Pi, H.; Wei, Y. Evaluation of the Sustainable Development of Traditional Ethnic Village Tourist Destinations: A Case Study of Jiaju Tibetan Village in Danba County, China. Land 2022, 11, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, G.M.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cui, J. Evaluation of Rural Community Based Agro-Tourism for Sustainable Agriculture and Tourism in China. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 60, 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.-F.; Chou, P.-C. Integrating Intelligent Living, Production and Disaster Prevention into a Sustainable Community Assessment System for the Rural Village Regeneration in Taiwan. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Multimedia Technology, Hangzhou, China, 26–28 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, P.; Beccaro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and Monitoring the Sustainability in Rural World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Florence Declaration on Heritage and Landscape as Human Values. In Proceedings of the 18th General Assembly of the International Council on Monuments and Sites, Florence, Italy, 9–14 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K. Research on the Basic Attributes and Contemporary Values of Chinese Traditional Villages. J. Ethn. Cult. 2017, 9, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Fu, J. The Meaning and Method of Evaluating the Value of Historical and Cultural Villages and Towns. J. Xi’an Univ. Archit. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2012, 44, 644–650+656. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 37072-2018; Evaluation for the Construction of Beautiful Villages. China National Institute of Standardisation: Beijing, China, 2018.

- China State Council. China’s National Plan on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. China State Council. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-10/13/content_5118514.htm (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Central Committee and State Council (Ed.) Rural Revitalization of Strategic Planning (2018–2022); People’s Publishing House: New Delhi, India, 2018.

- UNESCO. The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. In UNESCO World Heritage Centre; UNESCO: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Żukowska, S.; Chmiel, B.; Połom, M. The Smart Village Concept and Transport Exclusion of Rural Areas—A Case Study of a Village in Northern Poland. Land 2023, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.J.; Swerdlik, M.E.; Phillips, S.M. Psychological Testing and Assessment: An Introduction to Tests and Measurement; Mayfield Publishing Co.: Houston, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch, R.L. Factor Analysis: Classic Edition; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, A.; Zahediasl, S. Normality Tests for Statistical Analysis: A Guide for Non-Statisticians. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chua, Y.P. A Step-by-Step Guide Pls-Sem Data Analysis Using Smartpls 4; Researchtree Education: Buxton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Small, M.L.; Adler, L. The Role of Space in the Formation of Social Ties. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2019, 45, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C. Henri Lefebvre’s Theory of the Production of Space and the Critical Theory of Communication. Commun. Theory 2018, 29, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; Yu, H.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; Cui, H.Y. Livelihood Changes and Evolution of Upland Ethnic Communities Driven by Tourism: A Case Study in Guizhou Province, Southwest China. J. Mt. Sci. 2016, 13, 1313–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria for Selecting Villages |

|---|

|

| Shangzhuang Village (Village 1) | Guoyu Village (Village 2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Household Number | 360 | 420 |

| Tourism Development Stage | Mature stage (>10 Years) | Mature stage (>10 Years) |

| Dwelling Style | Grey brick courtyard | Fortress defensive Village |

| Formation Period | Yuan Dynasty | Ming Dynasty |

| Tourism Development Pattern | Government + Tourism Enterprises | Tourism Enterprises-driven |

| Step | Criteria for the Selection of Items |

|---|---|

| Step 1 | Items should reflect the economic, social, and cultural aspects of villagers. |

| Step 2 | Items should be villagers-centered, with any macro-scale indicator to be excluded. |

| Step 3 | Considering the education level and comprehension of villagers, similar items are merged, and one item is used as much as possible to measure the same area, such as deprivation versus attachment, and specialty versus industrial diversification. |

| Dimension | Items | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Dimension | Local Employment | Literature/Interview |

| Household Income | Literature/Interview | |

| Household Debt | Literature | |

| Capital Disparity | Literature/Interview | |

| Traditional Livelihood | Literature/Interview | |

| Industrial Diversity | Literature/Interview | |

| Industry Friendliness | Literature | |

| Agricultural Income | Literature | |

| Land Use | Interview | |

| Social Dimension | Social Relations | Literature/Interview |

| Management Fairness | Literature/Interview | |

| Villager Engagement | Literature | |

| Daily Activity | Literature/Interview | |

| Public Facilities | Literature/Interview | |

| Government Support | Literature/Interview | |

| Living Quality | Literature/Interview | |

| Culture Dimension | Culture Authenticity | Literature |

| Resident Happiness | Literature | |

| Sense of Relative | Literature/Interview | |

| Deprivation | Literature | |

| Village Identity | Literature/Interview | |

| Village Attachment | Literature/Interview | |

| Cultural Promotion | Literature/Interview | |

| Dwelling Richness | Literature | |

| Knowledge | Interview |

| No. | Items | Importance/ Applicability | Mean | First Quartile | Third Quartile | Standard Deviation | Coefficient Variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Local Employment | Importance | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 1.27 | 0.36 |

| Applicability | 2.6 | 2 | 3 | 0.84 | 0.32 | ||

| 2 | Household Income | Importance | 4.1 | 3.25 | 5 | 0.88 | 0.21 |

| Applicability | 4 | 3.25 | 4.75 | 0.81 | 0.20 | ||

| 3 | Household Debt | Importance | 2.8 | 2 | 3 | 0.79 | 0.28 |

| Applicability | 2.3 | 2 | 3 | 0.94 | 0.41 | ||

| 4 | Capital Disparity | Importance | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.70 | 0.19 |

| Applicability | 2.5 | 2 | 3 | 0.85 | 0.34 | ||

| 5 | Traditional Livelihood | Importance | 4.3 | 4 | 5 | 0.82 | 0.19 |

| Applicability | 4 | 3.25 | 4.75 | 0.82 | 0.20 | ||

| 6 | Industrial Diversity | Importance | 3.9 | 3.25 | 4 | 0.74 | 0.19 |

| Applicability | 3.8 | 3 | 4 | 0.79 | 0.21 | ||

| 7 | Industry Friendliness | Importance | 2 | 1.25 | 2 | 0.94 | 0.47 |

| Applicability | 1.8 | 1 | 2 | 0.79 | 0.44 | ||

| 8 | Agricultural Income | Importance | 3.3 | 3 | 4 | 0.95 | 0.29 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.85 | 0.24 | ||

| 9 | Land Use | Importance | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.53 | 0.15 |

| Applicability | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.84 | 0.23 | ||

| 10 | Social Relations | Importance | 3.8 | 3 | 4 | 0.79 | 0.21 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.85 | 0.24 | ||

| 11 | Management Fairness | Importance | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.97 | 0.28 |

| Applicability | 3.3 | 3 | 4 | 0.67 | 0.20 | ||

| 12 | Villager Engagement | Importance | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.84 | 0.23 |

| Applicability | 3.9 | 3.25 | 4 | 0.74 | 0.19 | ||

| 13 | Daily Activity | Importance | 4.1 | 4 | 4.75 | 0.74 | 0.18 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.85 | 0.24 | ||

| 14 | Public Facilities | Importance | 3.4 | 3 | 4 | 0.97 | 0.28 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.85 | 0.24 | ||

| 15 | Government Support | Importance | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.70 | 0.19 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.97 | 0.28 | ||

| 16 | Living Quality | Importance | 4.1 | 3.25 | 5 | 0.88 | 0.21 |

| Applicability | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.97 | 0.27 | ||

| 17 | Culture Authenticity | Importance | 3.7 | 3 | 4 | 0.67 | 0.18 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.71 | 0.20 | ||

| 18 | Resident Happiness | Importance | 3.2 | 3 | 4 | 1.14 | 0.35 |

| Applicability | 3.2 | 3 | 3.75 | 0.92 | 0.29 | ||

| 19 | Sense of Relative | Importance | 3.7 | 3 | 4 | 0.95 | 0.25 |

| Applicability | 3.5 | 3 | 4 | 0.84 | 0.24 | ||

| 20 | Deprivation | Importance | 3.2 | 3 | 3.6 | 0.63 | 0.20 |

| Applicability | 2.3 | 2 | 2.75 | 1.06 | 0.46 | ||

| 21 | Village Identity | Importance | 4.1 | 4 | 4.55 | 0.74 | 0.18 |

| Applicability | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.70 | 0.19 | ||

| 22 | Village Attachment | Importance | 3.9 | 3.25 | 4 | 0.74 | 0.19 |

| Applicability | 3.4 | 3 | 4 | 0.52 | 0.15 | ||

| 23 | Cultural Promotion | Importance | 3.7 | 3 | 4 | 0.67 | 0.18 |

| Applicability | 3.7 | 3 | 4 | 0.67 | 0.18 | ||

| 24 | Dwelling Richness | Importance | 2.7 | 2 | 3 | 0.67 | 0.25 |

| Applicability | 3.1 | 2.25 | 3.75 | 0.99 | 0.32 | ||

| 25 | Knowledge | Importance | 3.7 | 3.25 | 4 | 0.82 | 0.22 |

| Applicability | 3.6 | 3 | 4 | 0.70 | 0.19 |

| Item | No Change–High Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Has there been an increase in your family’s source or means of income after the development of tourism? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| A2 | To what extent has tourism development affected your household income? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| A3 | How has the share of traditional occupations changed since the development of tourism? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| A4 | What is the extent of change in household arable land that is not used for traditional cultivation and is instead invested in tourism development? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B5 | To what extent has your family’s quality of life improved after developing tourism? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B6 | To what extent are the rhythms of daily life affected by tourism? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B7 | Do you think the development of tourism has impacted the relationship with other villagers? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B8 | What is the level of government support for your family after the development of rural tourism? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| B9 | How involved are you in tourism development? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| C10 | To what extent does the cultural promotion of tourism influence you? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| C11 | To what extent do you recognize your village as unique? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| C12 | Has tourism development made you want to live in the village more? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| C13 | Has the development of tourism made you more interested in learning about the culture of your village? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Demographic Characteristic | Frequency (n) | Percentage (100%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village 1 | Village 2 | Village 1 | Village 2 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 43 | 101 | 43% | 49% |

| Male | 57 | 104 | 57% | 51% |

| Age | ||||

| 18–29 | 1 | 3 | 1% | 1.5% |

| 30–39 | 10 | 24 | 10% | 11.7% |

| 40–49 | 23 | 65 | 23% | 31.7% |

| 50–59 | 40 | 69 | 40% | 33.7% |

| Over 60 | 26 | 44 | 26% | 21.5% |

| Native or not | ||||

| Native | 87 | 161 | 87% | 78.5% |

| Migrate | 13 | 44 | 13% | 21.5% |

| Occupation | ||||

| Famer or traditional occupation | 19 | 41 | 19% | 20% |

| Village Leader | 6 | 19 | 6% | 9.3% |

| Farm family resort | 41 | 55 | 41% | 26.8% |

| Tourism Agritainment | 23 | 48 | 23% | 23.4% |

| Other | 11 | 42 | 11% | 20.5% |

| Factor/Item | Mean | Factor Loading | Eigen Values | Variance Explained | Cumulative Variance Explained | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Factor | ||||||

| A1 | 3.01 | 0.820 | 4.749 | 23.677 | 23.677 | 0.825 |

| A2 | 2.92 | 0.825 | ||||

| A3 | 3.13 | 0.816 | ||||

| A4 | 3.41 | 0.663 | ||||

| Social Factor | ||||||

| B1 | 2.9 | 0.812 | 2.273 | 20.929 | 44.606 | 0.792 |

| B2 | 2.98 | 0.818 | ||||

| B3 | 2.66 | 0.787 | ||||

| B4 | 3.01 | 0.530 | ||||

| B5 | 2.79 | 0.584 | ||||

| Culture Factor | ||||||

| C1 | 2.97 | 0.848 | 1.498 | 20.927 | 65.533 | 0.869 |

| C2 | 3.07 | 0.792 | ||||

| C3 | 3.19 | 0.808 | ||||

| C4 | 2.68 | 0.860 |

| Factor/Item | Mean | Out Loading | Composite Reliability | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Factor | ||||

| A1 | 2.85 | 0.913 | 0.873 | 0.678 |

| A2 | 2.81 | 0.885 | ||

| A3 | 2.92 | 0.875 | ||

| A4 | 2.73 | 0.574 | ||

| Social Factor | ||||

| B1 | 3.00 | 0.876 | 0.822 | 0.566 |

| B2 | 2.84 | 0.710 | ||

| B3 | 2.97 | 0.756 | ||

| B4 | 2.92 | 0.643 | ||

| B5 | 2.53 | 0.755 | ||

| Culture Factor | ||||

| C1 | 2.89 | 0.886 | 0.857 | 0.688 |

| C2 | 2.99 | 0.814 | ||

| C3 | 2.91 | 0.740 | ||

| C4 | 2.73 | 0.871 |

| Village | Tourism Impact | Spatial Environment | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holistic | Economic Factor | 0.427 | 0.000 |

| Social Factor | 0.326 | 0.000 | |

| Culture Factor | −0.376 | 0.000 | |

| Shangzhuang Village | Economic Factor | 0.461 | 0.000 |

| Social Factor | 0.370 | 0.000 | |

| Culture Factor | −0.357 | 0.000 | |

| Guoyu Village | Economic Factor | 0.325 | 0.000 |

| Social Factor | 0.314 | 0.000 | |

| Culture Factor | −0.387 | 0.000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Ismail, M.A.; Aminuddin, A.; Wang, R.; Jiang, K.; Yu, H. The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062721

Li Y, Ismail MA, Aminuddin A, Wang R, Jiang K, Yu H. The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(6):2721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062721

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yanan, Muhammad Azzam Ismail, Asrul Aminuddin, Rui Wang, Kaiyun Jiang, and Haowei Yu. 2025. "The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China" Sustainability 17, no. 6: 2721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062721

APA StyleLi, Y., Ismail, M. A., Aminuddin, A., Wang, R., Jiang, K., & Yu, H. (2025). The Lost View: Villager-Centered Scale Development and Validation Due to Rural Tourism for Traditional Villages in China. Sustainability, 17(6), 2721. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062721