Abstract

In response to escalating global ecological and environmental challenges, this study examines the impact of carbon information disclosure on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance to encourage corporate transition toward pollution reduction and carbon mitigation, thereby contributing to the practical advancement of the “dual carbon” strategy. Based on a hierarchical regression analysis of manufacturing listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets from 2009 to 2023, the findings reveal that carbon information disclosure significantly enhances corporate ESG performance. Mechanism tests reveal that green technology innovation partially mediates the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance, while environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition exert positive moderating effects on this relationship. Heterogeneity analysis indicates that carbon information disclosure exerts a pronounced positive effect on ESG performance for high-tech, heavily polluting, and eastern enterprises. This research expands the understanding of the value of carbon information disclosure and provides theoretical foundations and practical insights for enterprises pursuing sustainable development.

1. Introduction

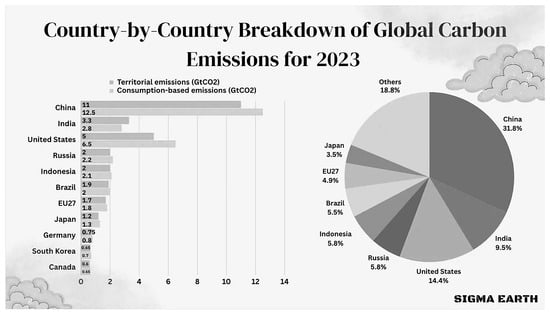

As the climate crisis progresses, global carbon emissions have increasingly become a barometer of our climate’s fate. Research indicates that the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events across regions and nations continue to rise, which is primarily driven by massive greenhouse gas emissions [1]. According to estimates by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC), global carbon emissions from fossil fuel combustion and industrial processes will reach 3.44 billion tons by 2023. China, as the world’s largest carbon dioxide emitter, accounts for 31.8% of global carbon emissions (as shown in Figure 1). Furthermore, a World Bank report indicates that over two-thirds of countries worldwide are planning to fulfill their emission reduction commitments to the Paris Agreement through carbon market mechanisms [2]. Against this backdrop of escalating global climate change and sustainability concerns, achieving “carbon peak and carbon neutrality” has become central to China’s sustainable development strategy [3]. As scholars indicate, China’s green economy is increasingly mainstreaming modern economic development [4], with most enterprises leveraging green production to stimulate new market demand and meet consumer green preferences [5], thereby enhancing corporate performance in environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance. In this process, carbon information disclosure, which is a vital means of signal transmission to the public and stakeholders, plays a critical role in enterprises’ long-term development [6]. Consequently, the quality of their carbon disclosure has increasingly drawn attention from all parties [7]. In practice, some enterprises still artificially manipulate or fabricate carbon data. Examples include Ordos High-Tech Materials Co., Ltd., which in 2021 became the first company in China that was exposed for falsifying carbon emissions data to reduce reported volumes (Note: See https://m.huxiu.com/article/458718.html?f=member\_article, accessed on 20 September 2025), and Shell’s 2023 rice cultivation carbon offset project in China, where opaque carbon information disclosure led to the creation of millions of worthless carbon credits (Note: See https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/03/28/revealed-how-shell-cashed-in-on-dubious-carbon-offsets-from-chinese-rice-paddies, accessed on 20 September 2025). This practice severely undermines companies’ long-term commitment to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance. Consequently, enhancing compliance with carbon information disclosure to elevate ESG performance returns represents a practical challenge for energy enterprises and a critical regulatory focus for governments [2].

Figure 1.

Global carbon emissions by country in 2023. (Note: Data image sourced from SIGMAEARTH website, published in “Global Carbon Emissions: Country-by-Country Overview for 2023” by Dr. Emily Greenfield on 11 November 2023).

A preliminary research framework for the socioeconomic effects of carbon information disclosure has been developed within the academic community. The existing literature primarily follows three research trajectories. Regarding the temporal scope of disclosure, companies can mitigate internal and external information asymmetries by strategically planning the functions of their carbon information disclosure over the long term, thereby avoiding future litigation and penalty losses from environmental regulatory pressures [8]. Concurrently, scholars, such as Gong Ning, have emphasized that while carbon information disclosure may erode short-term benefits amid cost and risk crises, it can substantially enhance market valuation levels in the long run [9]. From a capital market perspective, carbon information disclosure guides decisions regarding investor stock selection [7]. Research indicates that companies that voluntarily disclose carbon emissions achieve higher stock returns and lower equity financing costs than non-disclosing firms with these effects being pronounced in high-carbon industries [10]. For instance, Friske et al. observed that when companies publicly disclose their environmental impact and climate strategies, they effectively gain investor trust, thereby increasing capital inflows and improving stock performance [11]. Additionally, Bui et al. found a positive correlation between a company’s greenhouse gas emission intensity and its cost of equity; however, increased carbon disclosure mitigates this adverse effect [12]. Conversely, Huang et al. revealed that some firms exaggerate their emission reduction efforts by attempting low-cost greenwashing to gain market returns. This action ultimately misleads consumers, thus tarnishing perceptions of their products or services [13]. As scholars note, certain companies pursue greenwashing to enhance reputation and achieve competitive differentiation, thereby creating a snowballing effect of negative consequences [14]. From a regulatory perspective, incomplete laws, regulations, and oversight policies that govern carbon information disclosure may enable companies to manipulate their disclosures or engage in impression management [15]. Scholars, such as Huang Rongbing, have noted that firms may undertake symbolic gestures rather than substantive actions to cultivate a green image, thereby masking inaction on environmental protection [16]. The transparent regulation of carbon information also demonstrates positive aspects. For instance, research indicates that strengthening carbon information disclosure can shield major emitters from litigation risks [17] and prevent fines or penalties for failing to disclose such information to investors [18]. Therefore, a robust regulatory process serves as a crucial defense in enhancing corporate green governance.

Furthermore, as the core entities of economic activity, enterprises’ ESG performance has become a key benchmark for measuring their comprehensive value [19]. ESG performance not only reflects a company’s conduct in environmental responsibility, social responsibility, and corporate governance [20], but also serves as a crucial manifestation of its pursuit to unify economic and social value. Existing research has yet to thoroughly explore the mechanisms through which carbon information disclosure influences ESG performance via signal transmission and institutional legitimacy. Furthermore, the endogenous relationship between non-financial dimensions and corporate ESG development remains under-deconstructed, thus creating an innovative space for this study to establish the transmission logic between “carbon information disclosure and ESG performance.” Theoretically, numerous scholars have examined the expost effects of carbon information disclosure based on signal transmission theory [9]. However, prior discussions primarily focused on signal quality, thus notably neglecting the influence of the signaling environment. As the channel for signal transmission, the signaling environment refers to the aggregate external contextual conditions under which the sender conveys information and the receiver interprets it. It includes objective external factors, such as regulation, oversight, and market conditions, which can affect the sender’s intent and the receiver’s interpretation quality [10]. The study posits that the signaling environment can either suppress or amplify the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance. Clarifying carbon issues and enhancing signal transparency can strengthen the positive effect of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance returns. Therefore, further clarification is needed on whether the signaling transmission mechanism that incorporates external environmental factors can be applied to ESG performance analysis. Practically, carbon information disclosure promotes corporate performance [21]. However, its effects are not invariably positive. High transparency may expose firms to additional compliance costs, regulatory scrutiny, and potential competitive disadvantages [22]. Furthermore, scholars, such as Wang Guiping, have noted that China currently lacks clear, unified standards for carbon information disclosure, thus leading to divergent performance outcomes among firms [6]. Therefore, given the divergent and contradictory findings in the existing literature, the barriers between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance must be reexamined. On this basis, this study introduces signal transmission theory to elucidate how carbon information disclosure influences ESG performance by enhancing information transparency and transmitting positive signals. It also contributes empirical analysis to the limited literature on carbon accounting and proposes a theoretical framework that is tailored to China’s localized context.

Furthermore, relevant scholars have argued that carbon information disclosure is closely linked to green technology innovation [6]. However, whether ESG performance serves as a subsequent effect remains under explored. According to signal transmission theory, the systematic disclosure of carbon information makes implicit costs, such as corporate energy consumption structures and carbon emission intensity, thus increasing additional environmental governance costs for enterprises. This increase forces companies to reduce green product production costs through low-carbon technologies, such as process improvements and clean production [9]. This move achieves a closed-loop technological innovation cycle from R&D investment and patent accumulation to commercialization and ultimately contributes to enhanced ESG performance. Furthermore, scholars have emphasized the critical role of green technology innovation in the process of carbon information disclosure [6]. They argue that examining its impact and mechanisms is vital for advancing corporate ESG performance. This perspective further expands the contribution of this study.

Against the backdrop of the dual carbon goals, regulatory mechanisms for the quality of carbon information disclosure require further refinement [23]. While some scholars have conducted preliminary explorations into the effectiveness of carbon disclosure regulation from the perspectives of government subsidies and media attention [24], discussions on the various pressure types within the carbon disclosure context remain relatively narrow and fragmented. For instance, when examining the relationship between carbon disclosure and corporate economic value, scholars have focused on the roles of environmental regulations [22] and media attention [9]. This concentration inevitably hinders the accuracy of related findings. Therefore, core pressure sources within a unified framework must be reintegrated for discussion by systematically clarifying their underlying operational mechanisms. This task is yet to be fully accomplished in the existing literature. This study addresses this gap by analyzing three dimensions: government environmental regulations, social media attention, and market competition, thereby systematically enriching the research context for main effect logic. Furthermore, while some studies indicate that these pressure sources can drive corporate practices in carbon information disclosure [25], the question as to whether companies engage in impression management or expressive manipulation through carbon disclosure to alleviate legitimacy pressures and enhance ESG performance remains unexplored. In summary, this study employs environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition as key boundary conditions to address the aforementioned issues. It also responds to the strategic imperative of the “coordinated advancement of carbon reduction, pollution control, green expansion, and economic growth,” thus offering insights for policymakers designing carbon governance systems and optimizing corporate ESG practices.

This study raises several core questions. Does actual carbon information disclosure practice generate positive value for ESG performance? This issue is particularly prominent amid the momentum of the “dual-carbon” strategy. As scholars have noted, research on the impact and pathways of ESG performance under the new “dual carbon” framework represents an emerging and crucial field [3], which is precisely the focus of this study. Simultaneously, research on whether green technology innovation serves as a transmission mechanism in this process has remained unclear. Moreover, corresponding theoretical explanatory mechanisms are lacking. As regulatory systems, external oversight, and market environments continue to mature, how these external signaling environments will impact the relationship between the primary effect and secondary effects warrants further examination. This study addresses these questions by examining whether green technology innovation plays a role in the transmission mechanism of carbon disclosure and ESG performance. Furthermore, theoretical frameworks that explain this mechanism remain underdeveloped. Additionally, as regulatory frameworks, external oversight, and market environments continue to mature, how will these evolving external signaling conditions impact the primary relationship? This work answers these questions by examining China’s manufacturing sector. As the world’s largest carbon emitter, China has implemented multiple policies under its “dual-carbon” goals, including carbon trading, mandatory carbon information disclosure, and green finance. Manufacturing, which is a primary source of energy consumption and carbon emissions, faces stringent environmental regulations and low-carbon transition pressures while accumulating extensive corporate-level carbon disclosure and green technology innovation data. This scenario not only provides a unique institutional and industrial context for systematically examining the mechanisms that link carbon information disclosure, green technology innovation, and ESG performance but also lends significant theoretical and practical value to policy formulation and global low-carbon governance. In summary, this study constructs a primary framework for examining the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance. It investigates the mediating role of green technology innovation and the moderating effects of environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition by addressing the aforementioned key issues.

Finally, building upon existing scholarly research, this study further supplements and refines the field through the following contributions. First, from a signal transmission perspective, it resolves the asymmetry in bidirectional information flow between internal and external stakeholders by delving into the underlying mechanisms through which carbon information disclosure influences corporate ESG performance. This solution provides a comprehensive answer to whether carbon information disclosure by Chinese enterprises effectively enhances ESG performance. Second, this study constructs a “disclosure motivation—innovation behavior—outcome” model framework and focuses on verifying the mediating role of green technology innovation between carbon information disclosure and corporate ESG performance to clarify the specific transmission pathway from carbon disclosure to ESG performance. Third, grounded in legitimacy and signal transmission theories, this study systematically examines the heterogeneous effects of environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition. This approach brings the research process close to real-world scenarios, thus clarifying the genuine motivations behind carbon information disclosure while offering constructive insights for governments and enterprises pursuing dual carbon goals.

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Carbon Information Disclosure and ESG Performance

Signal transmission refers to the process by which enterprises convey their intrinsic characteristics to stakeholders through specific signals in information markets to reduce information asymmetry, thereby avoiding adverse selection issues [13]. For enterprises, carbon information disclosure, which is a form of non-financial information disclosure, essentially signals their environmental governance capabilities to the market by disclosing carbon emission data, reduction strategies, and environmental management practices [9]. This signal transmission serves dual functions. First, it reduces stakeholders’ perception of environmental risk and strengthens external trust in the firm’s commitment to sustainable development by enhancing information transparency. Second, it reinforces the firm’s reputational capital within the industry by constructing a narrative of legitimacy, thereby laying the groundwork for securing green financing, policy support, and market recognition. High-quality carbon information disclosure effectively bridges the signal transmission gap and counters adverse selection dilemmas, thereby mitigating perceived carbon risks for enterprises [10]. ESG performance refers to a company’s comprehensive demonstration across environmental protection, social responsibility fulfillment, and corporate governance, thus reflecting its sustainability level [19]. Environmental performance reflects achievements in resource utilization, pollution prevention, and ecological conservation, thereby focusing on environmental management efficiency and emission reduction outcomes. Social performance reflects a company’s fulfillment of responsibilities and contributions in various areas, such as consumer rights protection, stakeholder engagement, and community development. Governance performance reflects a company’s overall performance in strategic decision-making, risk management systems, and governance structures [3].

From the perspective of signal transmission theory, detailed carbon footprint disclosure not only demonstrates a company’s commitment to proactive environmental risk management but also serves as a tangible manifestation of its sustainability strategy [10]. Conversely, research indicates that ambiguous or selective disclosure may invite accusations of greenwashing, thus undermining the credibility of the signals [26] and consequently affecting stakeholders’ assessments of a company’s ESG performance. First, at the environmental protection level, carbon information disclosure conveys a company’s efforts and achievements in environmental governance by publicly sharing carbon emission data, reduction targets, and environmental management practices [6]. When such disclosures are accurate, comprehensive, and comparable, they help bridge the information gap between the company and external stakeholders, thereby reducing information gathering costs, transaction costs, and decision-making costs [13]. This advantage enables investors, consumers, and regulators to assess environmental benefits accurately [26], thus fostering positive expectations regarding the company’s environmental performance [22]. Consequently, it enhances the company’s motivation to fulfill environmental responsibilities and promotes improvements in environmental performance. Second, at the social responsibility level, disclosing actions related to reducing environmental pollution, protecting ecosystems, and supporting low-carbon community development conveys the company’s commitment to social responsibility to communities, government organizations, and other societal stakeholders [13]. It enhances the enterprise’s reputation and legitimacy, which enables access to government green financing through policy feedback mechanisms and improves social governance benefits. Finally, at the corporate governance level, carbon information disclosure represents a manifestation of senior management’s engagement with ecological issues [18]. Enterprises can embed environmental concerns into their governance systems, mechanisms, and decision-making processes by disclosing carbon data, thus fostering the development of a digital and intelligent green monitoring system within the organization [27]. This mechanism enables joint governance across multiple departments, including board oversight, management execution, and internal auditing to conduct internal environmental self-assessments and implement lean green management efficiently. It reduces operational control costs [28] and drives enterprises to integrate environmental practices into strategic top-level design. In doing so, it improves environmental management systems and enhances internal governance efficiency. Concurrently, relevant research indicates that this approach also curbs managerial short-sightedness and self-serving behavior, thus preventing senior executives from prioritizing economic gains at the expense of environmental and public welfare [27]. Consequently, it effectively elevates corporate governance performance. Therefore, carbon information disclosure contributes to enhancing corporate ESG performance. In summary, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Carbon information disclosure has a positive impact on ESG performance.

2.2. Mediating Effect of Green Technology Innovation

Green innovation refers to novel innovative activities that are implemented by enterprises or organizations in their technologies, products, services, and management systems. Its core objective is to maximize the efficient use of resources and promote sustainable development while enhancing economic benefits and minimizing negative environmental impacts [22]. Subsequent scholars have refined this concept, thus giving rise to the notion of green technology innovation. This development refers to technical innovation activities where enterprises or organizations enhance resource and energy efficiency, reduce pollutant emissions, and lower carbon footprints through the R&D and application of new technologies, processes, materials, or equipment to achieve synergistic benefits between economic and environmental outcomes [3]. According to signal transmission theory, carbon information disclosure transmits a firm’s demand for green technology upgrades to external markets by publicly sharing carbon emission data and reduction targets. It enables organizations to leverage information spillover advantages to attract external green innovation resources actively, thereby stimulating internal R&D and refinement of green technologies [13]. Furthermore, signal transmission theory indicates that carbon reduction tools and green technologies constitute high-cost signals. Given their substantial R&D investments, extended development cycles, and specialized nature [13], these innovations are difficult for competitors to replicate. This characteristic enables enterprises to reduce environmental risk exposure, enhance technological resource efficiency, and optimize production processes through supply chain collaboration and technology diffusion mechanisms. Consequently, it drives corporate energy conservation and emission reduction efforts, thereby improving ESG performance [29].

Carbon information disclosure serves as a highly transparent communication tool that clearly conveys a company’s intrinsic intentions regarding environmental governance and low-carbon strategies to external regulators, investors, and other market participants [13]. It creates a positive signal that reflects the company’s commitment to environmental responsibility [10] and its anticipated future plans for green technology upgrades. Such disclosure facilitates the development and implementation of green innovation technologies, thereby fostering efficient and verifiable technical practices. Concurrently, research indicates that carbon information disclosure can incentivize proactive green technology innovation [13]. Grounded in signal transmission theory, carbon information disclosure enhances corporate transparency and execution in green transformation by communicating the enterprises’ commitment to green transition and technological capabilities to governments, investors, and upstream-downstream partners [6]. This move attracts green credit allocation, policy subsidies, and cross-industry low-carbon technology integration. Relevant scholars indicate that green R&D subsidies are a crucial means to enhance corporate green innovation capabilities [30]. These subsidies enable enterprises to transform external resources into internal green innovation momentum, thereby triggering low-carbon technology R&D and production process restructuring. Furthermore, green technology adoption fundamentally reduces environmental resource consumption and pollution emissions [3], mitigates product-related environmental risks, lowers greenhouse gas emissions, and cuts environmental remediation costs [13]. It fosters environmentally friendly competitive advantages, thus enabling quantifiable improvements in environmental performance. Moreover, as public environmental awareness and green consumption concepts strengthen [3], enterprises are compelled to engage in green technology innovation to produce goods that are aligned with consumers’ low-carbon preferences. This solution not only reduces internal production costs but also enhances the enterprise’s external social responsibility performance, which will help the company earn positive public recognition [3]. Finally, innovative green tools facilitate the assessment of internal and external environmental risk factors, thereby preventing senior management from succumbing to the temptation of external conformity and selecting high-risk, low-return short-term green investment projects [31]. These technologies further optimize senior decision-making and internal management systems, thus enhancing corporate environmental governance capabilities and management transparency [32]. In summary, carbon information disclosure enhances corporate ESG performance by promoting green technology innovation. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Green technology innovation plays a mediating role between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance.

2.3. Moderating Effect of Environmental Regulation

Legitimacy theory posits that corporate environmental disclosure is motivated by legitimacy pressures that stem from government, public opinion, and market forces [33]. This perspective indicates that companies with poor carbon performance tend to engage in carbon information disclosure because they recognize that a major environmental pollution incident can strip them of their legitimacy and threaten their survival [9]. Companies alleviate this legitimacy pressure by disclosing additional positive information to shift the external perceptions of their actual environmental management capabilities, such as goals, strategies, and plans. This strategy aims to enhance their environmental image and reduce public concerns about their carbon performance [34]. Some studies indicate that companies may selectively engage in greenwashing to preserve their legitimacy and economic interests; these companies may disclose only relatively favorable metrics to conceal poor performance [35], thereby gaining stakeholder approval. This decision inevitably leads to frequent instances of “disconnect between words and actions.”

From the perspective of environmental regulation, this primarily refers to governments using environmental laws, policy controls, and other means to standardize and constrain corporate environmental behavior, thus compelling them to fulfill environmental responsibilities [36]. When such highly coercive regulations become embedded within an organizational environment, they profoundly influence the green practices and sustainability orientation adopted by the organization [37]. The “Porter hypothesis” also proposes that effective environmental regulation can induce an innovation compensation effect, thereby incentivizing companies to engage in innovative activities [31]. On the one hand, as the “visible hand” regulate market systems [36], governments announce incentive and penalty measures for environmental governance in low-carbon industries, such as policy support and green subsidies. Driven by profit motives and legitimacy concerns, enterprises voluntarily disclose carbon data to secure government support and green subsidies, thereby becoming increasingly willing to pursue green innovation projects and environmental practices [38]. On the other hand, environmental regulations establish mandatory compliance thresholds for corporate carbon information disclosure through institutional norms, thus guiding accurate reporting of carbon data. This requirement compels enterprises to conduct green economic activities within the “red line” of emission standards [39], thereby advancing the implementation of low-carbon practices. Furthermore, faced with strong institutionalized constraints, firms maintain consistent standards in carbon information disclosure with peers within the same institutional field to enhance market legitimacy and avoid political risks [36]. In doing so, enterprises prevent penalties. For instance, Wang Yun et al. found that when one company faces environmental administrative penalties, its peer firms increase environmental investments [40], thus effectively improving environmental performance. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Environmental regulations play a positive moderating role between carbon information disclosure and enterprises’ ESG performance.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Media Attention

From the perspective of media attention, this primarily refers to media outlets raising public awareness of corporate environmental risks through news reporting, public oversight, and online publications [41]. From a legitimacy perspective, enterprises must operate within societal norms and values to be regarded as legitimate by their stakeholders [42]. Media attention provides a public channel for social groups to convey environmental governance consensus and compliance standards, express environmental concerns, and monitor corporate carbon behavior. It serves as an effective tool for responding to stakeholders’ environmental demands and addressing legitimacy deficits [43]. High external media attention compels enterprises to declare their environmental performance through annual reports and green practices, thereby establishing a positive corporate image, mitigating potential reputational risks, and repairing legitimacy deficits caused by negative commentary to reduce trust crises [13]. It simultaneously reduces information asymmetry with external investors to enhance internal green financing levels [15]. Moreover, it facilitates increased corporate investment in green R&D and management improvements, thus amplifying positive environmental outcomes. Signal transmission theory further indicates that online media and newspapers serve as effective channels for corporate communication by helping expand the credibility of carbon information disclosure. Research indicates that the authoritative media coverage of corporate carbon information disclosure constitutes a credible “third-party endorsement” to some extent [42]. Such coverage not only conveys positive green transaction signals to the market but also prompts enterprises to strengthen their social responsibility awareness proactively in responding to public environmental expectations and coordinating with stakeholders. Consequently, companies voluntarily fulfill their social carbon reduction obligations [43], thereby achieving effective growth in ESG performance. Furthermore, Brammer and Pavelin indicated that media attention can supervise companies to improve the quality of environmental disclosure and regulate inappropriate practices in internal environmental management [44]. This scenario mitigates self-serving behavior among senior management and enhances environmental awareness [42], thereby facilitating the smooth operation of ESG environmental projects. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Media attention plays a positive moderating role between carbon information disclosure and enterprises’ ESG performance.

2.5. Moderating Effect of Market Competition

From the perspective of market competition, this primarily refers to market behaviors such as resource competition and technological competition that enterprises engage in with other industry players to maintain their market competitiveness, thereby subjecting them to heightened external competitive pressures [36]. It reflects market participants’ preference for low-carbon products and heightened environmental awareness. This competition not only requires enterprises to disclose carbon reduction data during carbon information disclosure but also sets high expectations for their fulfillment of environmental responsibilities [13]. According to legitimacy theory, enterprises meet the expectations of various market stakeholders and ensure survival in intense market competition by enhancing the transparency of carbon reduction information to lower market financing costs [22]. They actively assume environmental responsibilities to cultivate a positive “green image” in the market, thereby continuously attracting low-carbon entities to purchase their green products and maintain their legitimacy in the market [45]. Furthermore, relevant studies indicate that in intense market competition, enterprises that disclose information first often gain great market attention and investor recognition, thereby enhancing competitive advantages. Conversely, non-disclosing enterprises may face elimination risks for failing to align with market trends [46]. This scenario occurs because, under heightened market competition, enterprises proactively drive carbon information disclosure to showcase differentiated carbon reduction technology pathways, phased emission reduction achievements, and medium-to-long-term carbon neutrality goals. It transforms carbon management capabilities into green core resources that competitors cannot replicate quickly, thus enabling enterprises to gain significant differentiated “green competitive advantage” in the market [1]. Moreover, it enhances investor confidence in the company’s green development strategy [22], which encourages increased capital investment in green financing projects and alleviates funding pressures [6], thereby contributing to improved ESG performance. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Market competition plays a positive moderating role between carbon information disclosure and the ESG performance of enterprises.

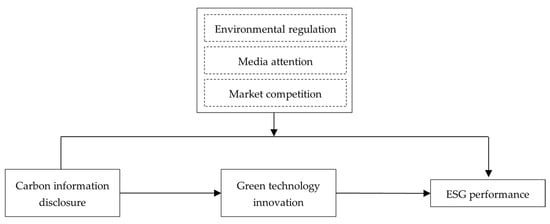

The theoretical model of the aforementioned study is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Theoretical model.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources and Variable Processing

This study employed empirical analysis using data from manufacturing-sector listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets from 2009 to 2023. The following data treatments were applied: (1) exclusion of all ST, *ST, and delisted enterprises; (2) exclusion of financial sector listed companies; (3) exclusion of all research samples with missing data; (4) mitigation of the impact of outliers, which involves continuous variables undergoing trimming at the 1% and 99% levels, thus yielding 6532 sample observations. ESG performance metrics were sourced from Bloomberg’s ESG indicators. Meanwhile, green technology innovation and media attention data originated from the CNRDS database. Environmental regulation data were derived from government work reports. In addition, carbon information disclosure, market competition, and control variables were obtained from the CSMAR database. The primary focus of missing value exclusion was on biased data during the pandemic period. This focus avoided systematic biases in the information, thereby effectively preserving the objective patterns within the data.

3.2. Variable Description

3.2.1. Explained Variable: ESG Performance of Enterprises

Referencing Wang Shuangjin et al. (2022) [47] and Xu Guanghua et al. (2025) [48], this study employed the Bloomberg ESG Composite Score to measure corporate ESG performance. This score encompasses detailed datasets across environmental (ESG_E), social (ESG_S), and governance (ESG_G) dimensions. The score ranges from 1 to 100 points, where high scores indicate superior ESG performance. The weighting criteria for environmental performance assess a company’s role as a steward of the natural environment. The weighting criteria for social performance evaluate how a company manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities in which it operates. The weighting criteria for corporate governance performance encompass leadership, executive compensation, auditing and internal controls, and shareholder rights.

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable: Carbon Information Disclosure

Following the methodology of Zhen Haoqing and Chen Ying (2025) [49], the corporate carbon information disclosure index from the Guotai An database was employed to measure the explanatory variable. This index adopts a four-element disclosure framework that comprises governance, strategy, risk and opportunity management, and metrics and targets. Each disclosure element is subdivided into several subcategories with scores assigned based on the level of detail disclosed by each company within each subcategory. The sum of all subcategory scores constitutes the enterprise’s carbon information disclosure index. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this index was 0.785, which indicated good reliability. The total score for this variable was capped at 50 points. High scores reflected high levels of carbon information disclosure. Detailed scoring criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Carbon information disclosure level assignment criteria.

3.2.3. Mediator Variable: Green Technology Innovation

Green technology innovation references included Shao Dongwei et al. (2025) [50], Yang Yongjie and Ruan Xinyan et al. (2023) [51], and Chen Lei and Zhang Jilong (2025) [52]. Based on the “Green Technology Patent Classification System” issued by the China National Intellectual Property Administration, green patents were screened. The total number of green invention patent applications and the total number of green utility model patent applications in the CNRDS database were ultimately adopted as core indicators to measure the volume of green patent applications. Then, add 1 to the number of green patent applications and take its natural logarithm to measure corporate green technological innovation.

3.2.4. Moderator Variable: Environmental Regulation, Media Attention, and Market Competition

Environmental regulation was measured using the methodology proposed by Chen Shiyi and Chen Dengke (2018) [53] and Chen et al. (2018) [54], and employing the proportion of words related to “environmental protection” (e.g., environmental protection, green, low-carbon) in government work reports relative to the total word count as a proxy variable for environmental regulation. Media attention was measured using the approach by Yan Min and Liu Xihang (2025) [55], where media attention was assessed by taking the natural logarithm of the sum of the total number of times a company was mentioned in headlines and body text across newspapers and online news sources plus 1. Market competition was measured using the approach of Zhang Yuming et al. (2021) [41], by employing the inverse of the Herfindahl Index. This index measures market or industry concentration, where high values indicate great monopoly and thus weak competition. Therefore, this study used the inverse of the Herfindahl Index as an indicator of market competition intensity. The specific calculation formula is , where is the operating income of a single enterprise, and n is the number of enterprises in the industry category to which the enterprise belongs.

3.2.5. Control Variable

Considering the impact of other factors on the ESG performance of enterprises, this study referred to previous academic research and uses firm size (Size), debt–equity ratio (DER), operating income growth rate (Growth), comprehensive leverage (CL), firm age (FirmAge), and whether the board of directors and senior management have a financial background (FinBack) as control variables. The specific definitions and measurements of the variables are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Symbols and definitions of main variables.

3.3. Model Setting

This research verified the above research hypotheses by using the three-step method described in the relevant literature to construct the following econometric model for empirical testing:

In the above equation, is the explained variable, representing the environmental, social, and governance performance of enterprise i in year t; is the explanatory variable, representing the carbon information disclosure index of enterprise i in year t; is the mediator variable, representing the level of green technology innovation of enterprise i in year t; , and represent the environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition faced by enterprise i in year t, respectively; , and are interaction terms; are test coefficients; are control variables; are individual and time fixed effects; is a random disturbance term. Despite incorporating control variables into the model, critical unobservable or unmeasured variables may still be omitted, leading to unavoidable coefficient bias.

4. Analysis Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

Based on descriptive statistics (see Table 3), the mean for carbon information disclosure was 13.660, while the median was 12.000, thus indicating that most companies pay relatively low attention to it. However, disclosure levels varied significantly across firms. The mean for green technology innovation was 1.397, which was higher than the median of 1.099. This outcome suggests that while most companies actively engage in it, their outcomes remain at a medium-to-low level, with substantial disparities in innovation effectiveness among firms. The mean ESG performance score was 30.097 with a median of 28.729, thus indicating that companies possess a certain foundation in ESG but still have room for improvement. Meanwhile, performance differences among companies are pronounced. The mean environmental regulation score was 0.007 with a median of 0.006, thereby reflecting the overall weak intensity and minimal variation in regulatory pressure faced by different companies. Media attention had a mean of 4.389, and a slightly above median of 4.060, thus indicating overall attention levels below high and significant variation in attention across firms. Market competition had a mean of −0.170, and a median of −0.136, thus reflecting overall competition at a low level.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistical Analysis.

4.2. Correlation Analysis and Multicollinearity Test

Descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for each variable were obtained through Pearson correlation analysis. The results are shown in Table 4. The relationships among key variables align with the anticipated economic and theoretical patterns. Simultaneously, multicollinearity diagnostics were performed for all variables to examine whether excessively high partial correlation coefficients might indicate multicollinearity issues. The results are shown in the values within parentheses in Table 4. The VIF values for each variable ranged between 1 and 3, which were well below the critical threshold of 5. This outcome indicates that no significant multicollinearity issues emerged among the variables, thus further supporting the robustness of the validation process.

Table 4.

Correlation Analysis and Multicollinearity Test Results.

4.3. Benchmark Regression Analysis

This study employed benchmark regression analysis to investigate the impact of carbon information disclosure on the ESG performance of manufacturing enterprises. The regression results are presented in Table 5. Column (1) excludes control variables. The results indicate that, when other factors are not controlled, the coefficient for carbon information disclosure’s effect on ESG performance is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.278, t = 27.059), thus suggesting a positive influence of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance. After incorporating control variables in Column (2), the results show that the coefficient for the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance remains significant at the 1% level (β = 0.262, t = 25.223). Compared with the R2 in Column (1) of Table 5, the R2 in Column (2) increases to 0.861, further enhancing the explanatory power of the model. This outcome indicates that carbon information disclosure can improve corporate ESG performance, thereby supporting H1. Furthermore, this study separately examined the sub-components of ESG indicators: environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance performance. As shown in columns (3) to (5) of Table 5, the impact coefficients of carbon information disclosure on environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance performance were significant at the 1%, 1%, and 5% levels, respectively (β = 0.476, t = 23.543; β = 0.261, t = 24.034; β = 0.033, t = 2.194). This outcome demonstrates that carbon information disclosure positively influences corporate environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance performance. Therefore, H1 is validated once more. This finding demonstrates that carbon information disclosure plays a significant role in enhancing the overall corporate ESG performance, with the most pronounced effect observed in the environmental dimension. This outcome may stem from the inherent environmental attributes of carbon emissions data, thus enabling a direct contribution to environmental performance improvement.

Table 5.

Results of Benchmark Regression.

4.4. Robustness Tests

We verified the reliability of the empirical results by conducting robustness tests using the following methods, which were drawn from the research of Xu Wenjing et al. (2022) [21] and Zhang Wei et al. (2025) [56]. First, we examined the robustness of the core findings by running the regression with the explanatory variables lagged by one period. As shown in Column (1) of Table 6, the coefficient for the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance remained significant at the 1% level (β = 0.204, t = 15.806), thus confirming that carbon information disclosure exerts a positive influence on ESG performance. Second, considering the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 as a major external shock that might have disrupted corporate operations, market conditions, and logical relationships among variables (e.g., supply chain disruptions, intensified policy interventions, and surging market volatility), this study employed a robust approach to exclude the potential confounding effects from the pandemic’s unique circumstances. This study incorporated it as a critical component of robustness testing. Regression analysis was re-conducted after excluding sample data from 2020. As shown in Column (2) of Table 6, the coefficient for the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance remains statistically significant at the 1% level (β = 0.247, t = 22.257), thus confirming the robustness of the aforementioned findings. Third, following the methodology of Wu Hanli and Xiong Yuxin (2025) [57], this study employed the Huazheng ESG Rating Index (ESG_1) as the dependent variable to replace the Bloomberg ESG Score for sensitivity testing. This approach re-evaluated the model and tested the significance of core variables. As shown in Column (3) of Table 6, the coefficient for the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance remained statistically significant at the 1% level (β = 0.054, t = 5.976). This test result shows no significant deviation from the core conclusions of this study, thus further demonstrating the robustness of the model.

Table 6.

Results of Robustness Tests.

4.5. Endogeneity Tests

Given the potential endogeneity between carbon information disclosure quality and corporate ESG performance because of bidirectional causality, this study adopted a two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach using the industry-average carbon information disclosure quality at the beginning of the sample period (IVCID) as an instrumental variable, which is following the methodology of Xu et al. (2022) [21]. Additionally, the results are presented in Table 7. In the first stage, the endogenous variable “carbon information disclosure” was regressed against the instrumental variable (IVCID) and control variables, simultaneously yielding the predicted variable (PCID) for the endogenous carbon information disclosure. In the second stage, the predicted variable and control variables were used to regress against corporate ESG performance. Results indicate that when applying the strength test for instrumental variables in Stage I, the test coefficient for carbon information disclosure is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.744, t = 17.194), thus confirming the selected annual industry average as a strong instrumental variable. Furthermore, the second-stage regression results reveal that the test coefficient for carbon information disclosure remains significant at the 1% level (β = 0.309, t = 6.589), thus indicating that carbon information disclosure significantly enhances corporate ESG performance. Therefore, after addressing the endogeneity issue of carbon information disclosure, the research conclusions of this study remain valid.

Table 7.

Tests via the Instrumental Variable (IV) Method.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

Given the characteristics of the current market environment, this study examines the potential impact of corporate technological capabilities, industry attributes, and regional differences on the test results.

(1) Heterogeneity test based on industry attributes. This study drew upon the research of Zhang Yongji et al. (2023) [58], Wang Yiqi et al. (2024) [59], and Li et al. (2024) [60], which categorized enterprises into high-tech and non-high-tech firms. Based on the Strategic Emerging Industries Classification Catalog and the Industry Classification Guidelines for Listed Companies (Li et al. (2024) [60], firms were classified into high-tech and non-high-tech enterprises. High-tech firm codes were determined based on relevant documents such as the “Catalogue of Strategic Emerging Industries” and the “Guidelines for Industry Classification of Listed Companies (2012 Revision).” High-tech firms were assigned the dummy variable 1, while non-high-tech firms were assigned 0. The empirical test results are shown in Column (1) of Table 8. The regression coefficient for CID × HighTech is significant at the 5% level (β = 0.035, t = 2.225), thus indicating that carbon information disclosure has a stronger positive effect on ESG performance for high-tech enterprises than non-high-tech enterprises. This finding can be explained by the resource-based view (RBV), which posits that a firm’s scarce resources and capabilities determine its competitive advantage [61]. High-tech firms typically possess abundant technological resources and R&D capabilities, thus enabling them to transform environmental risks exposed by carbon information disclosure into innovation opportunities [60]. This development facilitates enhanced ESG performance through green innovation and clean production. Conversely, non-high-tech firms lack sufficient technological reserves [59], thus causing difficulty in effectively translating disclosed information into concrete actions that improve environmental and social responsibility. Consequently, their ESG performance gains remain limited.

Table 8.

Results of Heterogeneity Analysis.

Additionally, this study drew upon the research of Zhang Yongji et al. (2023) [58] and Zhou Deliang and Li Hao (2025) [62], and classified enterprises into heavily polluting and lightly polluting categories. Following the “Catalogue of Environmental Protection Verification Industry Classification Management for Listed Companies,” which was issued by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2008, enterprises belonging to 16 industries were designated as heavily polluting enterprises and assigned a value of 1, including thermal power generation, steel, cement, and coal. Conversely, lightly polluting enterprises are assigned a value of 0. The empirical test results are shown in Column (2) of Table 8. The regression coefficient for CID × Pollute is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.076, t = 4.383), thus indicating that carbon information disclosure has a stronger positive effect on ESG performance for heavy polluting enterprises than light polluting enterprises. This result aligns with the logic of legitimacy theory, which emphasizes that enterprises need to meet societal expectations regarding environmental protection and corporate responsibility to maintain legitimacy [33]. Facing heightened policy oversight and societal scrutiny [63], heavily polluting enterprises can alleviate external pressures while reducing capital costs and reputational losses that stem from environmental risks. They can achieve this by showcasing their emission reduction and green transition achievements through carbon disclosure [62], thereby enhancing ESG performance. By contrast, lightly polluting enterprises, which are subject to low environmental externality pressures, tend to limit their carbon disclosure to compliance levels, thereby weakening the positive impact on ESG performance.

(2) Heterogeneity tests based on regional differences. Drawing upon the research of Ruan et al. (2024) [1], Huang et al. (2025) [13], and Zhang Yongji et al. (2023) [58], this study divided the overall sample into eastern enterprises and non-eastern enterprises. The eastern region encompassed the provinces and municipalities of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Shandong, Guangdong, and Hainan. All other provinces and municipalities were grouped as non-eastern enterprises. Eastern enterprises were coded as 1, whereas non-eastern enterprises were coded as 0. These values were incorporated into the regression equation for testing. The empirical results are shown in Column (3) of Table 8. The regression coefficient for CID × East is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.063, t = 3.867), thus indicating that carbon information disclosure has a stronger positive effect on ESG performance for eastern enterprises than central and western enterprises. This difference can be explained by institutional theory. Institutional theory suggests that corporate strategic decisions are often strongly influenced by the external institutional environment [64]. Eastern regions possess more mature institutional conditions, such as policy pilot programs, open capital markets, and robust financial support, than non-eastern regions. Consequently, enterprises in these areas are likely to gain policy incentives and market recognition after disclosing carbon information [63], thereby enhancing their ESG performance. By contrast, enterprises in central and western regions face disadvantages in institutional environments and resource access, which limit the promotional effect of carbon disclosure on corporate sustainability [1].

4.7. Mediator Effect Tests

The results of the mediation mechanism test are shown in Table 9. Column (1) indicates that the test coefficient for carbon information disclosure on green technology innovation is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.005, t = 3.076). This outcome suggests that carbon information disclosure positively promotes corporate green technology innovation. Column (2) of Table 9 shows that the test coefficient for green technology innovation on ESG performance is significant at the 1% level (β = 0.458, t = 5.428), thereby indicating that green technology innovation positively promotes corporate ESG performance. Furthermore, compared with the regression coefficient for carbon information disclosure in Column (2) of Table 5, the regression coefficient for carbon information disclosure in Column (3) of Table 9 decreased from 0.262 to 0.260 after incorporating the green technology innovation variable. However, the R2 value increased from 0.861 to 0.862. Additionally, comparing the test results in Columns (2) and (3) of Table 9 reveals that the regression coefficient for green technology innovation decreased from 0.458 to 0.376, while the R2 value increased from 0.847 to 0.862. Collectively, these results indicate that green technology innovation partially mediates the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance, thus confirming the validity of H2. This finding suggests that carbon information disclosure not only directly enhances corporate ESG performance but also indirectly promotes overall corporate sustainability through the mediating pathway of fostering green technology innovation.

Table 9.

Results of mediator effect Tests.

This study employed the Sobel test to examine the mediating mechanism. The results are presented in Table 10. Regarding the Sobel-Goodman mediation effect test, the p-values for the Sobel test and Goodman-1, Goodman-2 tests were all significantly less than 0.05, thus indicating a significantly indirect effect. Furthermore, the total effect size is 0.529, while the mediation effect size is 0.007. The mediation effect accounts for approximately 1.32% of the total effect. Additionally, the Sobel Z-value equals 4.378 > 1.96, thereby confirming the presence of a significant mediation effect. Although the effect size of the mediating effect is relatively small, CID influences ESG performance through a direct pathway and a significant indirect pathway via green technology innovation. This result may stem from the more immediate nature of the direct pathway from carbon information disclosure to ESG performance, whereas green technology innovation involves time costs from patent application to generating ESG outcomes, thus potentially diluting its effect.

Table 10.

Sobel Test Results.

4.8. Moderating Effect Tests

Furthermore, this study examines the moderating effects of environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition. The interaction terms were centered to avoid multicollinearity issues. The results of the moderation tests are presented in Table 11. Column (1) of Table 11 reveals that the interaction term between environmental regulation and carbon information disclosure exhibits a significantly positive regression coefficient (β = 8.482, t = 2.111). This outcome indicates that environmental regulation exerts a significantly positive moderating effect on the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance. Strong environmental regulation amplifies the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance, thereby validating H3. High levels of environmental regulation not only increase the costs and risks of non-compliance for enterprises but also compel them to enhance the quality and transparency of carbon information disclosure through policy pressure. This scenario forces enterprises to translate carbon disclosure practices into substantive green production and management actions. As shown in Column (2) of Table 11, the interaction term between media attention and carbon information disclosure exhibits a significantly positive regression coefficient (β = 0.016, t = 4.918). This outcome confirms that media attention significantly positively moderates the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance. Strong media attention amplifies the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance, thus validating H4. High levels of media attention enhance the reputational effects of corporate carbon information disclosure through public oversight and pressure, thus elevating societal expectations for corporate responsibility post-disclosure. This trend incentivizes companies to improve their ESG dimensions. As shown in Column (3) of Table 11, the interaction term between market competition and carbon information disclosure exhibits a significantly positive regression coefficient (β = 0.279, t = 3.913). It confirms that market competition significantly positively moderates the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance. Strong market competition amplifies the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance, thus validating H5. Intense market competition imposes sustained innovation pressure and differentiation demands on enterprises, thereby compelling them to leverage carbon information disclosure to gain green competitive advantages in the market and achieve high ESG performance. These findings further reveal the critical role of external environmental factors in the process where carbon information disclosure promotes ESG performance. However, it is worth reflecting that while these external moderating factors can strengthen the relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance, they may also introduce certain threshold effects. For instance, excessive environmental regulation may inflate compliance costs and squeezing innovation investment. Media attention that is biased or short-term may prompt companies to over-cater to public attention at the expense of long-term goals. Moreover, in overly intense market competition, resource-constrained SMEs may struggle to benefit from ESG transformation. Therefore, future research should further explore the nonlinear effects and threshold effects of moderating factors to provide targeted guidance for policymakers and corporate managers.

Table 11.

Results of Moderating Effect Tests.

5. Research Conclusions and Outlook

5.1. Research Conclusions

This study examines the relationship among carbon information disclosure, green technology innovation, and ESG performance based on signal transmission theory and legitimacy theory. It further analyzes the moderating effects of environmental regulation, media attention, and market competition, thus leading to the following key conclusions:

(1) Carbon information disclosure significantly enhances corporate ESG performance. From an environmental perspective, the systematic disclosure of carbon intensity, emission reduction pathways, and energy transition plans enables companies to respond to environmental demands and drive low-carbon technological innovation, thereby reducing environmental compliance risks and improving environmental performance. From a social perspective, carbon information disclosure builds stakeholder trust through data visualization and demonstrates societal benefits by showcasing community engagement and green product development, thereby co-creating social value. From a governance perspective, carbon information disclosure institutionalizes carbon management systems by embedding them into high-level strategic management. It curbs opportunistic behavior through management accountability mechanisms, thus aligning strategic decisions with environmental goals and improving the efficiency of green resource allocation. This finding aligns with existing empirical evidence that carbon information disclosure enhances corporate market value [22], primarily through alleviating financing constraints and reducing information asymmetry. However, this study further supplements the evidence chain by using ESG sub-dimensions as direct dependent variables, which bridges the gap between value relevance and ESG performance research.

(2) Green technology innovation plays a partial mediating role between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance. Enterprises can attract external resources such as policy subsidies and green financing, through carbon information disclosure. This disclosure facilitates the timely replenishment of R&D funding by alleviating financial constraints on innovation activities. Adequate financial support accelerates the iterative innovation of green technologies, thus driving enterprises toward low-carbon process transformation and clean production. It enables enterprises to overcome high-cost, long-cycle innovation bottlenecks, thereby achieving low-carbon production at an accelerated pace, reducing energy consumption, preventing environmental pollution, and ultimately enhancing ESG performance. Huang et al. also emphasized that carbon information disclosure can enhance corporate economic value through green innovation [13], which aligns closely with this study’s findings. Furthermore, scholars, such as Wang Guiping et al., have indicated that carbon information disclosure significantly promotes green technology innovation [6]. Subsequently, other scholars, such as Zheng Yuanzhen et al., have further analyzed how green technology innovation can enhance corporate ESG performance [3]. Therefore, the findings of this study align with previous scholarly research by demonstrating objective regularity and universality. In doing so, this work contributes to the expost analysis of carbon information disclosure.

(3) Environmental regulations, media attention, and market competition significantly and positively moderate the impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance. Environmental regulations compel enterprises to translate carbon information disclosure into substantive emission reduction actions through mandatory policy constraints, thereby enhancing environmental performance. Media attention amplifies the visibility of corporate carbon information disclosure through public oversight and news coverage, thus motivating enterprises to fulfill social responsibilities actively and implement environmental obligations effectively to improve social performance. Market competition incentivizes firms to build differentiated green competitive advantages via high-quality carbon disclosure through the “race to the top” effect of industry-wide low-carbon transformation, thereby elevating their ESG performance. Concurrently, prior research has indicated that environmental regulations amplify the positive effect of carbon disclosure on firm value [22], which is consistent with this study’s treatment of environmental regulations as boundary conditions. Furthermore, Gong et al. (2024) found that media attention significantly enhances the role of carbon information disclosure in boosting corporate market value [9]. Their finding aligns with this study’s conclusion that high media attention and reporting intensity are correlated with enhanced ESG performance from corporate carbon disclosure. However, the aforementioned perspectives focus solely on governmental and societal dimensions, thus neglecting the critical element of market competition. Therefore, this study introduces market competition as a boundary condition and concludes that market competition strengthens the positive relationship between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of environmental regulation, media attention, and market competition for corporate strategies for sustainable development.

(4) Heterogeneity analysis indicates that carbon information disclosure by high-tech, heavily polluting, and eastern enterprises yields strong improvements in ESG performance. Specifically, high-tech enterprises, which possess robust green innovation capabilities and resource integration advantages, can effectively translate carbon information disclosure motivations into low-carbon technology R&D and clean production practices, thereby driving ESG performance gains. High-pollution enterprises, which face heightened environmental regulation pressures and social oversight, respond to compliance demands and rebuild social trust through strict carbon information disclosure standards, thereby improving ESG performance. Eastern enterprises leverage institutional advantages to engage in carbon information disclosure, thus capturing technology spillover effects and policy resources to accelerate low-carbon transformation and enhance ESG outcomes. Conversely, for non-high-tech, low-pollution enterprises in central and western regions, constraints such as weak technological reserves, low environmental externalities pressure, and limited policy resources diminish the positive impact of carbon information disclosure on ESG performance.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study presents a meticulous validation process and offers theoretical contributions to related research fields.

(1) The existing literature often treats carbon information disclosure and ESG performance as mutually independent topics, thus resulting in fragmented theoretical connections between them. Moreover, most studies are confined to a single theoretical paradigm, thus causing difficulty in explaining the complex underlying logic between the two. Building upon prior research, this study finds that carbon information disclosure and ESG performance are not only directly related, and their transmission processes and boundary conditions correspond to two distinct theoretical explanatory mechanisms: signal transmission and legitimacy. Therefore, this study expands the theoretical framework by integrating signal transmission theory and legitimacy theory for the first time. This integration predicts the logical connection between carbon information disclosure and ESG performance, thus revealing the causal “black box” between them. Consequently, it profoundly addresses the core question of the mechanism through which carbon information disclosure influences corporate ESG performance. Therefore, this work fills the gap in theoretical explanations within related research on carbon disclosure.

(2) Existing research on carbon information disclosure focuses on economic outcomes such as corporate value and investment behavior. However, insufficient attention has been paid to the specific pathways through which it influences ESG performance. This study constructs a logical framework of “disclosure motivation—innovation behavior—outcome effects” based on signal transmission theory. It systematically reveals the intrinsic mechanism by which carbon information disclosure drives improvements in corporate ESG performance through green technology innovation. This finding not only expands the economic implications of carbon information disclosure but also provides new research perspectives and theoretical foundations for future scholars exploring the specific pathways through which carbon information disclosure translates into ESG performance.

(3) At the boundary context level, this study innovatively integrates diverse external factors into a unified theoretical framework that is grounded in legitimacy theory and signal transmission theory, including environmental regulation, media attention, and market competition. This design breaks away from previous studies’ isolated analysis of single mechanisms, thus reflecting a systematic understanding of corporate decision-making logic across multiple scenarios in real-world contexts. Furthermore, the research leverages the underlying logic of legitimacy theory. It not only clarifies the core drivers and key motivations for corporate carbon information disclosure under different external environments but also provides a comprehensive and structured theoretical perspective for explaining the complex causes of behaviors regarding carbon information disclosure.

5.3. Methodological Contributions

Methodologically, the study establishes an integrated empirical framework that encompasses the main effects, mediating effects, and moderating effects. It reveals the complete causal chain through which carbon information disclosure impacts ESG performance by incorporating the mediating role of green technology innovation and the moderating influence of multiple external contextual factors into the model. Compared with prior research that has focused solely on single effects or pathways, this framework significantly enhances the model’s explanatory power and applicability. Furthermore, the study employs several methods, such as centering interaction terms, multidimensional regression, and robustness tests, in its design. These approaches effectively mitigate the risks of multicollinearity and specification bias, thereby ensuring the scientific rigor and reliability of empirical findings. This work provides a valuable reference for constructing and testing econometric models in related fields.

5.4. Practical Implications

5.4.1. Implications for Corporate Practice

From a corporate perspective, as the core implementers of carbon information disclosure and green transformation, enterprises must establish systematic response mechanisms in strategic governance, technological innovation, and external constraint responses. This approach maximizes the utility of carbon information disclosure and advances the implementation of sustainable development goals.

First, enterprises should integrate carbon information disclosure into their strategic governance systems. They can ensure comparability and traceability across ESG dimensions by establishing standardized, verifiable environmental disclosure frameworks. This approach not only reduces the scope for “accommodative” disclosures that stem from information asymmetry, which prevents transparency losses because of selective reporting, but also helps companies accumulate “trust capital.” It enhances their legitimacy and reputational assets in capital markets and among the public, thereby creating long-term competitive advantages.

Second, enterprises should focus on strengthening the endogenous drivers of green technology innovation by concentrating on R&D for low-carbon production technologies and the iteration of green production processes. They should actively build a technology standards system and green certification mechanism that is oriented toward the dual-carbon goals. This approach not only amplifies the positive externalities of innovation through green technology spillover effects, which promote the diffusion and sharing of green technologies within the industry, but also positions green technological innovation as a key driver for corporate low-carbon transformation. It facilitates synergistic gains across ESG dimensions, thus ultimately achieving a profound restructuring of the ecological value chain and cultivating sustainable competitive advantages.

Finally, in response to external constraints, such as environmental regulations, media oversight, and market competition, enterprises must proactively leverage policy incentives, public scrutiny, and industry competitive pressures to address and transform high-pollution operations. For instance, enterprises can generate endogenous incentives for green innovation under the dual influence of external institutional pressures and internal governance improvements. They can adopt clean production processes, strengthen green supply chain management, and enhance transparent governance structures. This approach helps achieve a “synergistic effect” between clean production and low-carbon transformation, thereby elevating corporate ESG performance and sustainable development capabilities to a higher level.

5.4.2. Implications for Government Management

From the government perspective, as the core entity responsible for establishing carbon information disclosure rules and policy incentives, the government must develop a systematic top-level design that encompasses institutional frameworks, policy tool allocation, and social co-governance mechanisms. This development ensures standardized carbon information disclosure, efficient green transition, and equitable market mechanisms.

First, governments must enhance the regulatory framework and legal structure for carbon information disclosure. This process involves establishing scientific, unified standards that clarify disclosure frequency, reporting criteria, and accountability mechanisms to ensure quantifiable, verifiable, and traceable corporate disclosures. For instance, establishing rigorous audit and verification mechanisms can effectively curb greenwashing driven by profit motives, thus safeguarding the authenticity and integrity of disclosed data at its source and preventing the misallocation of green finance and environmental governance resources.

Second, governments should develop a policy toolkit that combines incentives with constraints. On the one hand, positive incentives, such as green credit, tax breaks, and carbon trading subsidies, should reduce financing costs for green innovation and low-carbon transformation, which can encourage long-term investments in environmental performance improvement. On the other hand, governments must simultaneously strengthen negative constraints by rigorously reviewing corporate financing and project development processes. This solution prevents companies from exploiting policy arbitrage or circumventing emission reduction responsibilities through superficial disclosures, thus ensuring standardized and efficient green innovation practices.