1. Introduction

Urban parks create significant social places where people obtain recreation, relaxation, and social contact. During nighttime, however, their accessibility and functionality heavily depend on lighting quality. Path illumination ensures visibility and orientation, most critical for a sense of security, whereas illumination of vertical elements or landmarks can add legibility of space; thus, an enhanced sense of visual comfort and security could be obtained [

1]. Above all, lighting not only enables physical movement but also organizes social life, enabling evening walking, gatherings, and activities, thereby extending communities’ presence into the evenings and contributing to city activity. However, artificial light has an environmental cost. Artificial light at night (ALAN) disrupts nocturnal wildlife, from attracting or disorienting insects to fragmenting their habitats and reorganizing ecological processes [

2]. As a case in point, LED lighting has been shown to diminish nocturnal pollination by about 62% in certain environments, slowing plant reproduction and insect richness [

3]. Night lighting also induces physiological reactions in urban vegetation: street lamps can harden leaves, rendering them inedible and significantly reducing herbivory, thus disrupting food webs [

4]. Conversely, properly designed artificial lighting can be ecologically and humanly beneficial when planned to an optimum level. Adaptive light strategies, control of intensity, spectrum, and timing, can minimize ecological destruction while maximizing human function.

Lighting in urban parks is primarily aimed at enhancing the sense of safety for users and creating an attractive landscape that encourages people to spend more time outdoors after dark [

5]. This is particularly important for pedestrians, who rely on outdoor lighting to make cities accessible for long periods, especially in areas with seasonal variations in daylight hours. Improved street lighting positively influences subjective experiences of safety in public spaces and is a frequently used strategy to reduce crime and enhance feelings of security. For instance, women’s perceptions of safety are significantly influenced by physical factors; they are more prone to personal safety concerns in public spaces than men, and often experience cities differently due to worries about violence and harassment, especially when traveling at night [

6]. Fear of crime is often disproportionate to actual victimization chances, and well-lit environments are perceived as less dangerous, helping to alleviate this fear.

Important physical factors contributing to a sense of security include visibility, cleanliness, the presence of other users, surveillance, trees, and time of day. Visibility is essential for detecting potential threats [

7]. Research based on prospect–refuge theory emphasizes that prospect (the ability to see) and entrapment (the state of being caught) are fundamental to safety perceptions [

7]. Proper lighting improves prospects and reduces opportunities for concealment and entrapment. Conversely, dense vegetation can create hidden spaces and obstruct views, inducing fear. Low visibility and isolated areas are linked to increased fear of crime [

8]. Therefore, artificial lighting supports prolonged activity and recreation within parks and allows for the upkeep of communication corridors during the nighttime. Lighting can increase the utilization of streets and pedestrian travel, encouraging casual watching and furthering community confidence and cohesion. In general, lighting renders parks unable to be “dark patches” in the urban environment, thereby encouraging their utilization.

Specifically, outdoor lighting improves neighborhood quality and has been shown to increase walking activity across various age groups, including adolescents, adults, and older adults. It is considered crucial for urban environments to be accessible to pedestrians after dark. The concept of a pedestrian’s hierarchy of needs suggests that lighting addresses fundamental needs like feasibility, accessibility, safety, comfort, and pleasurability, all of which influence the decision to walk after dark [

9,

10]. Insufficient lighting can create unsafe and less motivating urban paths, leading to considerable detours, especially in urban parks that may become barriers to walking after sunset [

11]. While safety and ecological impacts of artificial lighting in urban parks have been widely studied, much of the existing literature focuses on technical performance indicators or ecological consequences in isolation. What remains less explored is how park users themselves perceive the balance between safety, comfort, and biodiversity protection, and how these perceptions can inform design strategies. Recent studies have introduced innovative data-driven approaches to assess urban vitality, such as linking spatial accessibility with point-of-interest (POI) reviews and residential data [

12]. These approaches provide valuable insights into broader urban dynamics, yet they often overlook the experiential and perception-based dimensions that shape how people use and value green spaces.

In this study, the term urban park refers to publicly accessible green spaces located within city boundaries that provide recreational, social, and ecological functions. Such spaces usually include formal infrastructure such as pathways, benches, and lighting, which support both usability and safety. However, the meaning and role of parks can vary significantly across cultural and social contexts. In some regions, parks primarily serve as sites of leisure and family gathering, while in others they may function as ecological reserves or spaces for civic expression. Gendered experiences further influence perceptions: for example, women may associate well-lit areas with safety and accessibility, whereas insufficient or poorly designed lighting may limit their sense of comfort and restrict evening use. These differences underscore that an urban park is not a universally fixed concept but one shaped by local standards, cultural practices, and user needs. This study focuses on the Polish context, and specifically Wrocław, while acknowledging that findings should be interpreted in light of broader international diversity in green space design and use.

Environmental Impacts of Artificial Lighting in Urban Parks

While useful for people, artificial lighting in urban parks has significant environmental implications, particularly in terms of light pollution and biodiversity. As undesirable effects of artificial lighting, light pollution may manifest in the forms of sky glow, glare, and light trespass. Artificial lighting damages urban ecosystems by interrupting the circadian rhythms of animals and plants, creating microclimates, and affecting fauna and flora. The ecological approach aims to retain darkness at night and use warm color temperatures (low correlated color temperature, or CCT) to minimize such effects. For instance, a study focusing on the lighting scheme in an urban park (Grabiszyn Park of Wrocław in Poland) shows the issue of combining urban lighting with night [

5]. Initiated as a participatory budget system to promote safety for strolling and running at night, it was met with widespread protests from citizens concerned about the impact on nature (trees, night animals), cost, and the likelihood of unacceptable social behavior. Public consultation led to a reduced ambition plan, with insistence on fixtures that do not emit light upwards and a lighting curfew to maintain the dark sky. The 4000K correlated color temperature (CCT) was considered too cool, and warmer ranges of 1900–2500K were recommended for green spaces to reduce glare and insect attractants [

5]. This case demonstrates how the conflict between keeping the park natural and offering a feeling of security arises. The majority of residents support the use of turning off nighttime lighting in parks to maintain nature, as well as permit astronomical observation.

While the field accepts the need for user-centered design, the works mentioned above indicate that research is increasingly embracing elements such as participatory approaches, accessibility considerations, and user experience evaluation. Research entails methods like focus groups for questioning pedestrians’ ranking of urban design aspects in walkability to enable varied and subtle sharing of information. Research also aims at discovering people’s preferences and emotional reactions to lighted cityscapes so as to counter intuitive designer-centered thinking [

9,

13]. The example of Grabiszyn Park highlights citizens’ direct involvement through a “participatory budget project” and, afterwards, public consultations that influenced the lighting decisions. Quantitative methods are used with high precision in studies, e.g., surveys based on self-report questions are used to analyze perception in urban parks. Although this research acknowledges the ongoing need for further research and more effective methodologies, it does uncover significant efforts made in bridging the gap with the use of a range of mixed-methods. The innovation of this study lies in combining ecological assessment with participatory input, allowing lighting strategies to be shaped not only by environmental concerns but also by community priorities. This allows a greater comprehension of the part that light plays in influencing human perception and behavior within urban parks and the overall impact of the external environment. Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore perceptions of urban park lighting through a combination of workshops and surveys, linking public input to evidence-based design guidance focusing on the research questions below:

2. Materials and Methods

A mixed-methods approach was adopted to align with the study’s objectives: understanding how lighting affects biodiversity perception, user experiences, and perceptions of safety. Combining these methods allows for a more comprehensive analysis that integrates behavioral, perceptual, and ecological dimensions of urban park lighting.

2.1. Study Context and Project Link

URBIO BAUHAUS (formally “New European Bauhaus for Increasing Urban Biodiversity”) is a transnational cooperation project co-funded by the Interreg Central Europe programme. It applies New European Bauhaus principles of sustainability, aesthetics, and inclusion to protect and restore urban biodiversity through co-designed, place-based interventions. A key feature of the project is its emphasis on community participation: local hubs called BIOCENTUM (Biodiversity-Centered Urban Mindset) have been established to bring together local residents, city staff, and researchers for education, shared planning, and practical activities. The project spans four Central European cities—Kranj (Slovenia), Pula (Croatia), Wrocław (Poland), and Érd (Hungary)—each serving as a living lab for site-specific actions that enhance urban biodiversity.

In Wrocław, the URBIO BAUHAUS pilot focuses on mitigating light pollution in Langiewicz Park by co-developing smart, biodiversity-sensitive lighting solutions with community input via the local BIOCENTUM node. Comprehensive baseline studies have been conducted to inform this intervention, including a full dendrological inventory, vegetation mapping, entomological and ornithological surveys, and bioacoustic monitoring of wildlife activity in the park. These ecological assessments were paired with social research—notably field observations and a user survey carried out in collaboration with the Gajowice District Council—to ensure that the proposed lighting design responds to both environmental data and the perceptions and needs of park users. This integrated approach situates the lighting pilot within a broader strategy of evidence-based co-design for urban biodiversity.

Wrocław, the fourth largest city in Poland with a surface of 293 km

2 and located within the Silesian Lowland and partly in Lower Silesia, is characterized by a complex urban structure [

14]. Approximately 36.6% of the city’s area consists of green and open urban spaces [

15]. A significant component of the city’s spatial system is its extensive network of green areas, including 44 public parks and numerous other forms of designed and recreational greenery, which constitute an important element of both social and environmental infrastructure [

16].

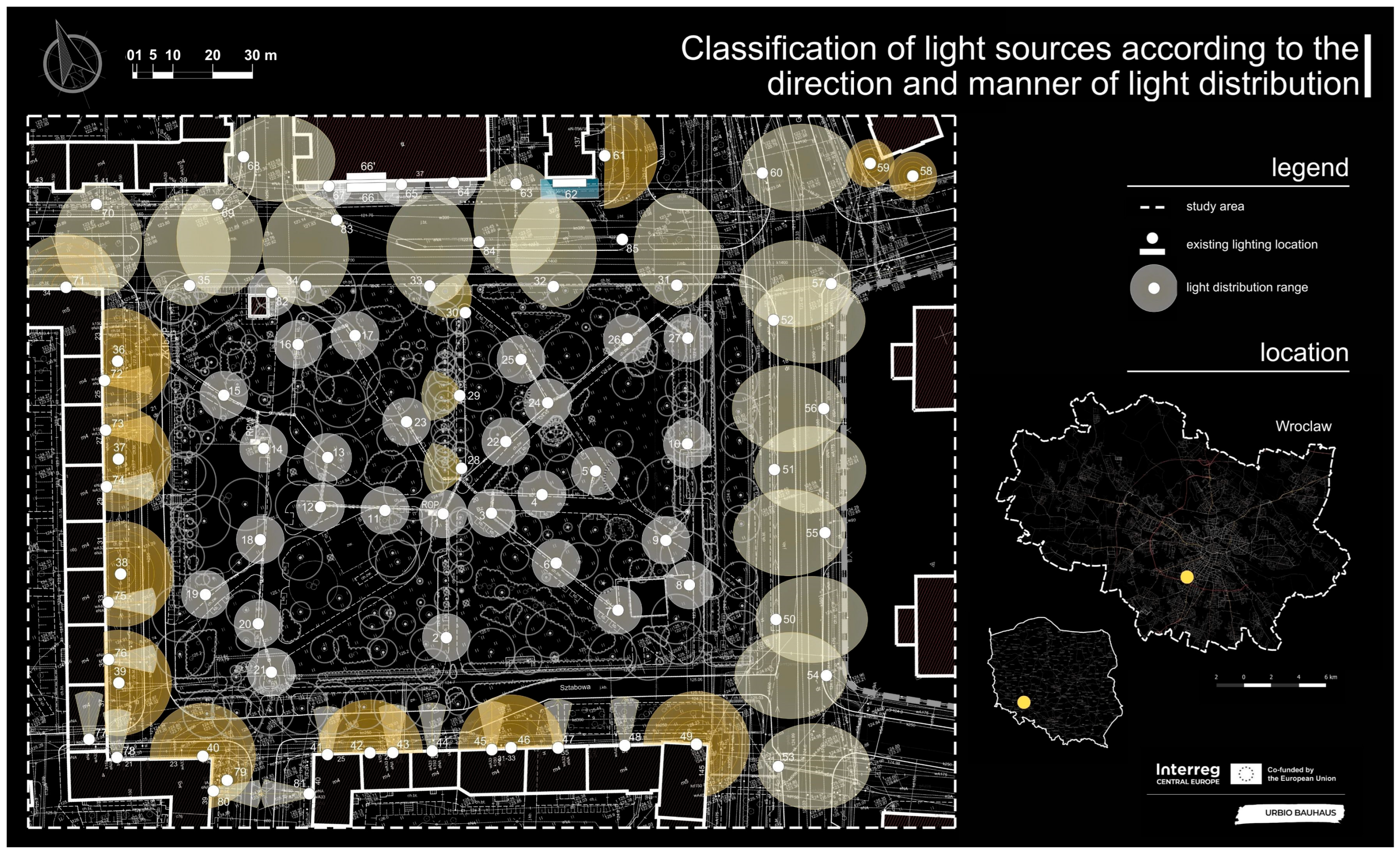

Langiewicz Park is a small urban park (approx. 1.1 ha) located in the Gajowice district of Wrocław, established in 1958 on the site of the former Gabitzer Friedhof (

Figure 1). Bounded by Gajowicka Street to the east, Bernarda Pretficza Street to the north, Wróbla Street to the west, and Sztabowa Street to the south, the park is characterized by a compact recreational layout with preserved old-growth trees. The surrounding district is subject to conservation protection as part of the city’s archaeological zone and historic urban layout [

17]. As part of a revitalization project completed in autumn 2021, new lighting was installed to improve the park’s accessibility and usability. This context makes Langiewicz Park an ideal demonstrator site for testing biodiversity-sensitive lighting strategies under the URBIO BAUHAUS framework.

2.2. Workshop Design

In an effort to actively engage citizens and local stakeholders in the process of co-creating a sustainable city and respecting biodiversity in the park, on the last day of March 2025, the Municipal Public Library, branch No. 6 in Wroclaw, hosted workshops with residents and local stakeholders on light pollution and the introduction of solutions aimed at increasing biodiversity in the city. A total of 14 participants attended the participatory workshop. The workshop was organized by representatives of the Wroclaw Municipality and the Wroclaw University of Environmental and Life Sciences, in cooperation with the Municipal Greenery Management Company and the Gajowice District Council.

As mentioned above, to mitigate excessive night lighting, the pilot project plans to introduce smart lighting in Langiewicz Park, serving as a demonstration site for the project. Therefore, the meeting addressed the topic of biodiversity and, based on examples of inappropriate lighting, explained what light pollution is, why it matters, and what effects it has on plants, animals, and human health. Alternative solutions for modernizing the lighting in Langiewicz Park were also discussed. During the workshop, participants were encouraged to share their comments on lighting in the neighborhood and to evaluate the lighting in Langiewicz Park. The conclusions from the workshop inspired and supported the Wroclaw Municipality in the design of lighting in Langiewicz Park.

Participants were recruited through a combination of direct invitations to local community members, interaction with the District Council members, announcements in neighborhood groups, and on-site recruitment in the park. The group reflected a diverse mix of demographics, including different age groups, genders, and levels of familiarity with the park, though the majority were residents who regularly used the park for recreation. The workshop followed a structured sequence designed to facilitate engagement and co-creation:

Introduction: Presentation of the study objectives and explanation of the role of lighting in urban parks, including its social and ecological implications.

Discussion: Open conversation about personal experiences of using the park at night, perceptions of safety, and observed ecological effects.

Filling the chart and open voting to map the related problems in the park activity: Participants worked individually to identify areas of the park they considered problematic or valuable in terms of lighting and biodiversity. They then suggested design solutions, including desired lighting types, locations, and intensities.

The workshop generated a range of qualitative material, including facilitator notes summarizing group discussions, participant visuals and sketches, flipcharts, and sticky notes. These materials were subsequently collated and analyzed thematically to identify recurring user priorities, concerns, and design suggestions. The workshop lasted 2 h.

2.3. Survey Design

The study employed a structured questionnaire consisting of 36 questions, combining both multiple-choice items and open-ended questions. The survey covered four main thematic blocks: (1) demographic and background information, (2) frequency and patterns of park use, (3) perceptions of safety, lighting, and ecological quality, and (4) preferences and expectations for future park lighting design. The inclusion of both closed and open-ended items allowed for a balance between quantifiable measures and richer qualitative insights. Participants were recruited using a mixed sampling approach. The survey was distributed online via Google Forms, shared through social media channels and community mailing lists, and complemented by on-site recruitment in the park to ensure representation of regular users. At the same time, a poster with a QR code to the survey link was placed in the park. Additionally, a snowball sampling strategy was applied, whereby respondents were encouraged to share the survey link within their networks. This strategy facilitated the inclusion of diverse user perspectives while remaining accessible to both frequent and occasional park visitors. Data was collected during the winter of 2025. Respondents could complete the survey either online (via Google Forms) or using a paper-based version administered on-site. This dual mode of administration minimized the potential exclusion of participants less familiar with digital tools and enhanced accessibility across age groups.

3. Results

3.1. Workshop Findings

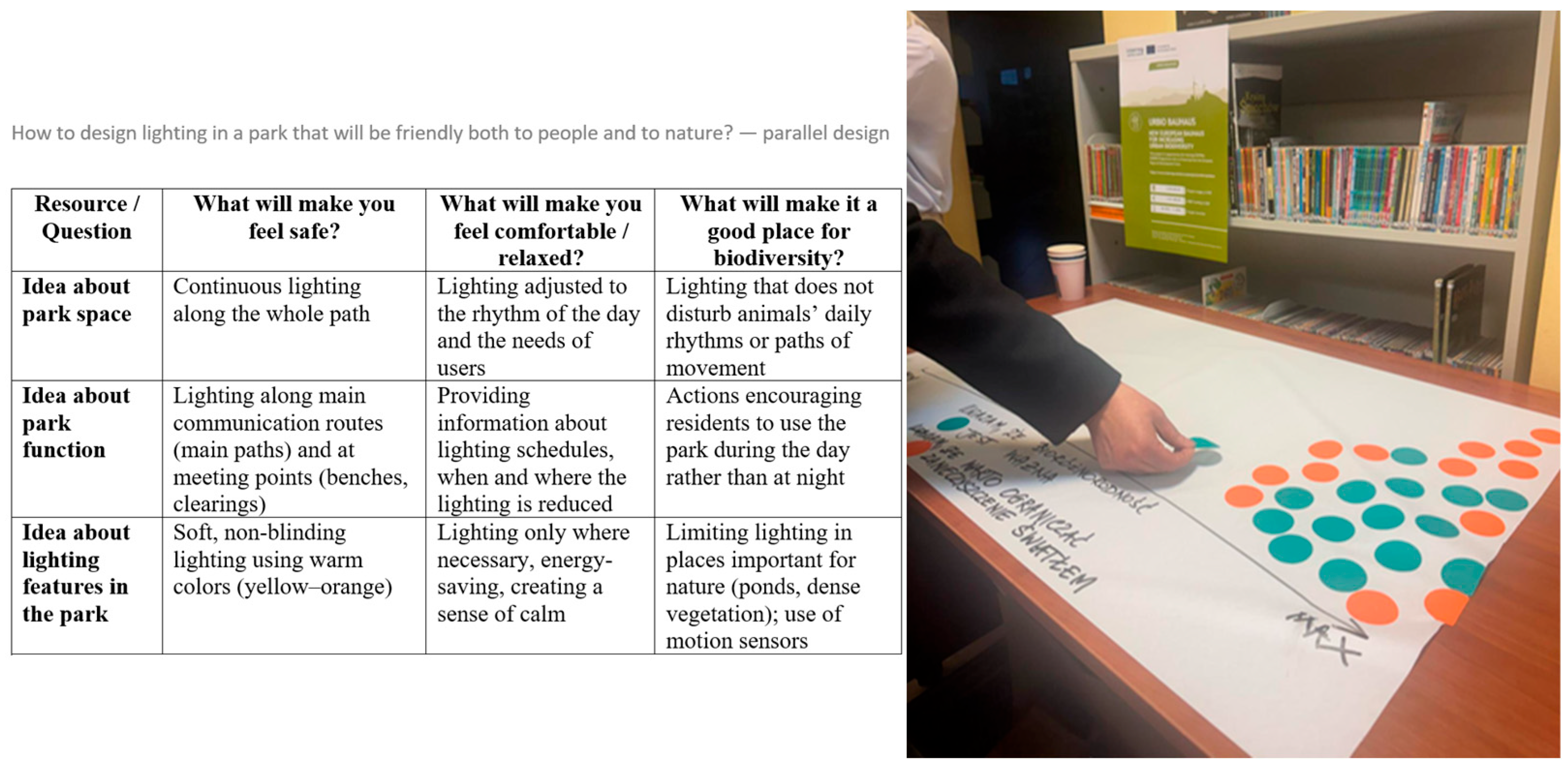

The materials collected from the workshop were systematically analyzed by the authors. Workshop discussions were transcribed and analyzed using thematic coding. Two researchers independently coded the material to ensure reliability, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Based on this analysis, three key themes emerged, reflecting user priorities and trade-offs between safety, functionality, and ecological sensitivity (

Figure 2). The emergence of these themes was validated through a triangulation method, combining facilitator notes, participant visuals, and the researchers’ independent coding. This approach enhanced the robustness of findings and ensured that interpretations reflected a convergence of multiple data sources rather than a single perspective.

Theme 1: Safety and security (lighting placement, visibility).

Lighting should focus on main communication routes (paths, thoroughfares, and gathering areas) to ensure orientation and safety.

There is an emphasis on adequate but not excessive illumination; lighting should provide visibility without creating glare or discomfort.

Lighting should also support specific functions of the park (playgrounds, sports areas, meeting spots), but not extend unnecessarily to quiet/natural zones.

Theme 2: Comfort and atmosphere (warm vs. cool light, brightness).

Lighting should reflect the functions of specific areas, e.g., higher intensity along paths and entrances, lower intensity or no lighting in natural habitat areas.

Participants stressed the value of adjustable lighting that responds to actual use (e.g., motion sensors, dimming after certain hours).

The importance of balance between safety and environmental preservation was emphasized: not all areas should be equally lit.

Brightness and uniformity should be adapted to function, enough to feel safe, but not so strong as to disturb wildlife or create harsh contrasts.

Color temperature (warmer CCT) could reduce ecological impact and create a more comfortable atmosphere.

There was recognition that poor placement or excessive lighting could create negative experiences (glare, disorientation).

Theme 3: Biodiversity and sustainability (light pollution).

Participants noted the importance of preserving dark zones where wildlife can thrive undisturbed.

Lighting should be selectively applied, only where human activity justifies it, avoiding constant illumination across the entire park.

Concerns were raised about light pollution and its negative effects on both plants and animals.

3.2. Survey Findings

As mentioned earlier in the methodology (

Section 2.3 Survey Design), among all 36 questions, this study focuses on the results of the questions related to perceptions of lighting because they directly capture how users experience safety, comfort, and ecological impacts in nighttime park environments. While demographic data provide important contextual insights, perception-based questions are central to understanding user needs and priorities, and thus most relevant for informing evidence-based design guidance. The results of the other survey questions are not included in this stage of analysis, as they will be examined in later phases of the project where broader behavioral patterns and management implications are addressed.

A total of 144 respondents participated in the survey. The majority were in the 35–44 age group (38.2%), followed by 25–34 years (22.2%), and 45–54 years (9%), with smaller shares in younger and older cohorts. Women made up the majority of participants (56.9%), compared to men (41%), with a small proportion choosing not to disclose gender. Regarding park visitation frequency, nearly half of respondents (49.3%) reported visiting the park daily, while 28.5% visited 1–2 times in a week and 13.9% 1–2 times in a month. The majority (68.8%) lived in very close proximity to the park (within 500 m), with another 22% living within 1 km, suggesting that the surveyed population largely consisted of nearby residents. Patterns of time-of-day use indicated that the park is being used mostly between 12:00–17:00 by 66.7%, which is followed by the evening visits (17:00–20:00) by 61.7% of the participants. Morning and early morning visits were less frequent (24.8% and 26.2%), and night visits after 20:00 were uncommon (13.5%). These findings highlight the importance of adequate artificial lighting for evening use, which represents peak visitation hours.

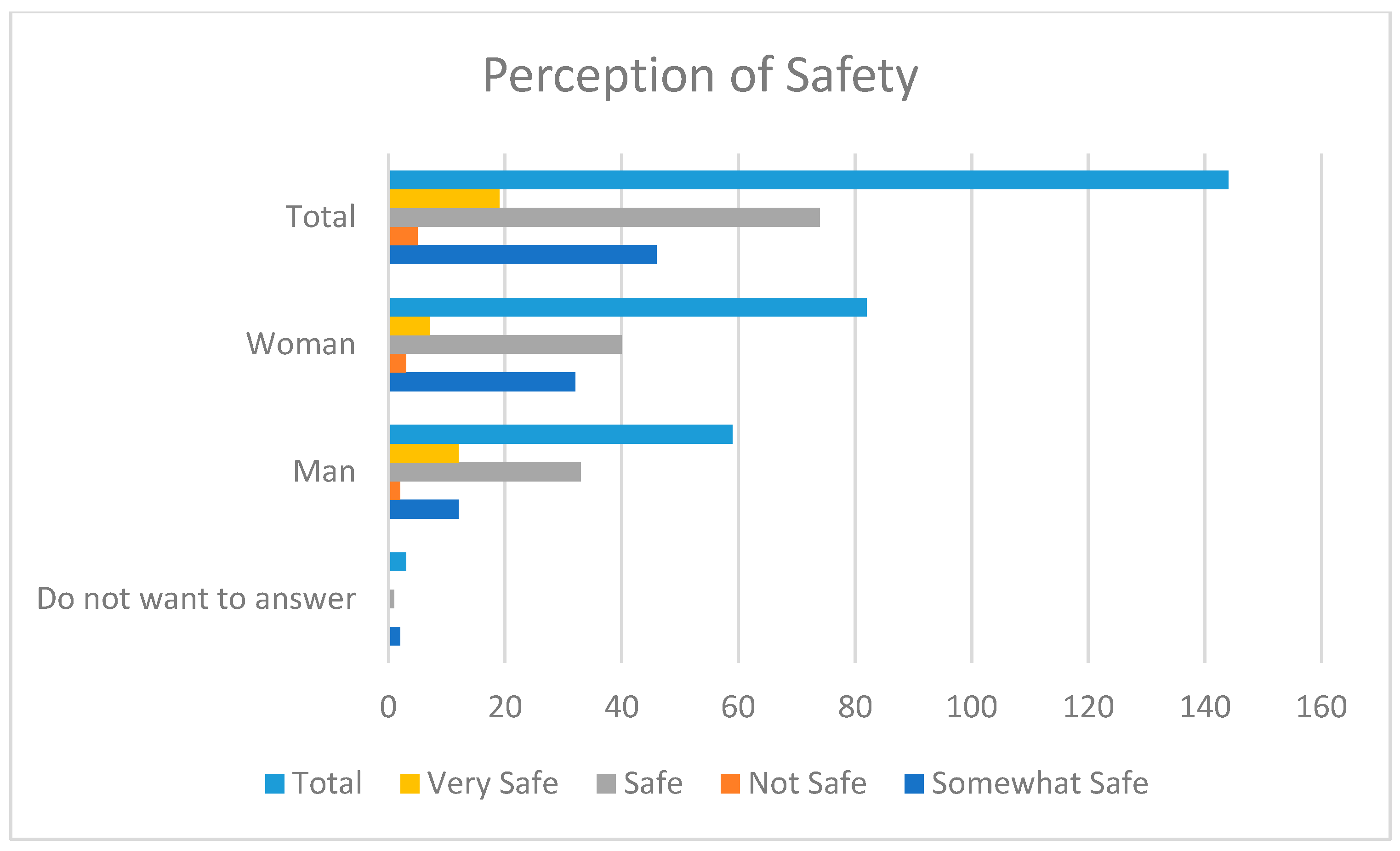

Perceptions of safety in general in the park showed mixed results: a majority described the park as either “safe” (52.5%) or “somewhat safe” (30.5%), and 13.5% reported feeling “very safe”. A cross-tabulation of gender and safety perception revealed notable differences. Women were more likely to report feeling only

moderately safe (39%) compared to men (20%), while men were more likely to report feeling

very safe (20%) than women (9%) (

Figure 3). A Chi-square test of independence indicated that this association was marginally non-significant (χ

2 = 7.73, df = 3,

p = 0.052), suggesting a trend toward gendered differences in safety perception that warrants further investigation. Perceptions of biodiversity underscored its importance for users: a strong majority (57.4%) indicated that biodiversity was “very important” for their park experience, and another 29.1% considered it important. Only a small proportion mentioned it as neutral (12.8%). This finding highlights the ecological dimension of park appreciation alongside social and recreational aspects. Perceptions of ecological management were mixed. While over half of respondents (53.2%) expressed neutrality about the satisfaction with current efforts to maintain and protect natural habitats in the park, only 5.7% were very satisfied, 27% were satisfied, and 14.1% reported dissatisfaction.

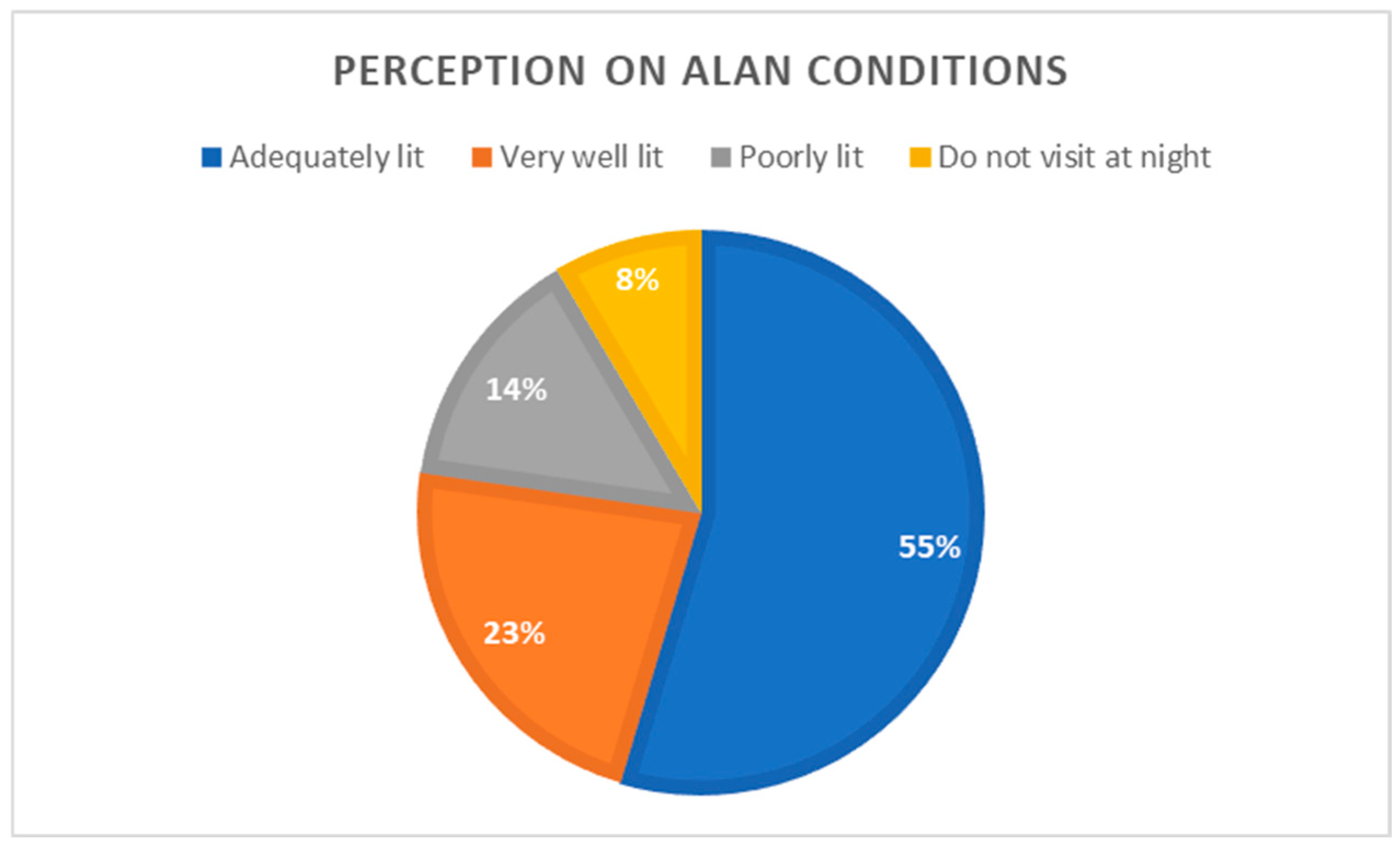

When evaluating artificial lighting conditions at night, a majority of participants (54.6%) considered the park to be adequately lit, while 22.7% found it very well lit and 14.2% described it as poorly lit (

Figure 4). This reflects a general perception of sufficient illumination during evening or nighttime hours. Perceptions of safety in illuminated conditions revealed that almost half of the respondents (48.9%) felt only moderately safe, while 9.9% reported feeling unsafe. The distribution of artificial lighting was another point of criticism: over half of the respondents (51.1%) indicated that lighting was unevenly distributed across the park (there are well-lit and dimly lit areas), with only 27% considering it evenly spread. When asked whether artificial lighting enhances the park’s appearance at night, most respondents agreed (36.9%) or strongly agreed (34.8%). Only a small minority disagreed (9.2%). This suggests that despite safety concerns, lighting is generally perceived as aesthetically beneficial.

Regarding environmental impacts, a significant proportion (44%) believed that artificial lighting has a negative effect on the natural environment, with an additional 9.2% strongly agreeing. Only a minority perceived positive impacts (1.4%) or no influence (20.6%). This reflects a need for awareness of the ecological trade-offs of artificial lighting. Finally, respondents were asked about their willingness to reduce light intensity if artificial lighting were proven to have no negative impact on nature. A large majority (64.5%) selected the option “It could be reduced by half if it would have a significant impact on nature”, while 29.1% answered “I wouldn’t choose to reduce it”. In total, 6.4% answered “It can be completely turned off”. From the open-ended question, 45 answers were collected (

Table 1).

4. Discussion

Beyond the local scale, the Langiewicz Park case is part of a larger experiment in urban biodiversity-sensitive design. This study’s participatory approach is embedded in the URBIO BAUHAUS transnational initiative, where Wrocław and three other Central European cities are testing New European Bauhaus-inspired solutions for greener urban spaces. Insights from each site—including the public preferences and ecological considerations highlighted in Wrocław—feed into a joint roadmap toward more biodiversity-rich urban environments in the region. The findings from Langiewicz Park not only inform local planning (helping city officials refine lighting strategies that balance safety with ecological sustainability) but also provide valuable lessons for other cities seeking to reconcile human needs and biodiversity in public space design.

The workshop results highlighted the dual mandate of park lighting: ensuring that people feel safe and oriented, while minimizing ecological disruption [

1,

18]. The notes suggest a preference for functionally targeted, adaptive lighting instead of even illumination. The guiding principle is “as much as necessary, as little as possible”, emphasizing lighting only where it supports essential park use. This aligns strongly with contemporary urban lighting strategies that recommend zoning approaches (separating ecological areas from social areas in terms of lighting design) and adapting smart/adaptive systems (sensors, dimming, time-based control) [

18]. Also, ecological sensitivity with dark corridors for wildlife and using warm-spectrum lighting were mentioned, which align with artificial lighting strategies [

19].

The survey results provide important insights into how urban park users perceive lighting in relation to safety, comfort, and ecological concerns. The demographic profile of respondents, predominantly adults aged 25–44, with women representing the majority, suggests that the study reflects the views of a socially active and locally engaged group. The fact that most respondents live within 1 km of the park and nearly half reported daily visits indicates that the park is an integral part of their everyday routines. Moreover, patterns of use demonstrate that afternoon and evening are peak visitation hours, highlighting the crucial role of artificial lighting in ensuring accessibility during periods of reduced natural light. Perceptions of safety reveal a nuanced picture. While most participants described the park as safe or somewhat safe, relatively few reported feeling very safe. Even when artificial lighting was present, almost half of the respondents felt only moderately safe, with some still reporting feelings of insecurity. These findings suggest that lighting is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee perceived safety. Factors such as distribution, intensity, and integration with the broader spatial context appear to influence user confidence. This is consistent with observations that uneven illumination, reported by over half of the respondents, creates zones of insecurity even in otherwise well-lit environments. Despite these shortcomings, respondents largely valued the aesthetic benefits of artificial lighting. The majority agreed that artificial lighting improves the park’s nighttime appearance, demonstrating the dual role of lighting as both a functional and experiential element of urban design. This aligns with the broader literature emphasizing the importance of legibility and ambiance in nighttime public spaces. At the same time, the study highlights a significant ecological awareness among park users. The vast majority rated biodiversity as important or very important to their park experience, underscoring the relevance of environmental qualities alongside social and recreational ones. However, satisfaction with ecological management was modest, with many respondents neutral and only a small fraction very satisfied. This may reflect limited visibility of conservation efforts, or a perceived imbalance between human-centered and ecological priorities. Importantly, more than half of the respondents recognized the negative impacts of artificial lighting on the environment, particularly on flora and fauna. The tension between ecological awareness and lighting preferences is especially evident in attitudes toward light reduction. While a large share of respondents expressed willingness to accept reduced light intensity if ecological impacts were proven significant, nearly a third opposed any reduction, and only a small minority supported the idea of a complete removal of artificial lighting. This illustrates a central dilemma: users value ecological sustainability in principle, but in practice prioritize comfort, safety, and visual quality when it comes to nighttime lighting. The findings highlight a central tension in urban park lighting: while users emphasize the need for reliable and evenly distributed illumination to ensure safety, orientation, and evening accessibility, they also express strong ecological awareness and concern over biodiversity impacts. This duality reflects the broader international debate on how to reconcile human comfort with environmental stewardship in urban design. In particular, it illustrates that safety is necessary but not sufficient for perceived well-being in public space; users value ambiance, legibility, and ecological integrity simultaneously. This resonates with emerging research that links perceptions of lighting to broader measures of urban vitality and accessibility, including innovative approaches that use POI reviews. The study contributes to the ongoing search for integrative, biodiversity-sensitive lighting practices in cities.

Overall, these findings emphasize the need for balanced, evidence-based lighting strategies in urban parks. On the one hand, users demand reliable and evenly distributed lighting to support safety and social use during peak evening hours [

11]. On the other hand, they express concern about biodiversity and ecological degradation caused by excessive artificial illumination [

20]. Addressing this duality requires integrative solutions such as adaptive lighting technologies, context-sensitive placement, and ecological light management (e.g., warm color temperatures, shielding to limit sky glow) [

9]. By aligning user preferences with biodiversity-sensitive practices, park designers and managers can enhance nighttime accessibility without compromising ecological integrity.

5. Conclusions

Lighting needs in urban parks are not uniform and depend strongly on local conditions. Factors such as climate, cultural context, and user expectations shape how lighting is designed and perceived. For instance, in regions with extended daylight hours, lighting strategies may prioritize minimizing ecological disruption, while in areas with high evening use, safety and accessibility often take precedence. These differences highlight that our findings are context-specific to Wrocław; however, the methodological framework and guiding principles proposed here can be adapted to other locations by aligning them with local environmental conditions and social needs.

The findings provide transferable lessons on balancing safety and biodiversity through lighting design, although specific recommendations should be adapted to local contexts. For urban planners and designers, the results of this study highlight the need to prioritize adaptive lighting strategies that balance safety, comfort, and environmental responsibility. They should consider technologies such as dimmable systems, motion-sensitive controls, and warm-spectrum luminaires that reduce ecological impact while maintaining visibility. For instance, zoning strategies that differentiate between high-activity areas (e.g., paths, playgrounds) and ecological zones can help balance safety with biodiversity protection. Also, adaptive lighting systems (motion sensors or time-based dimming) can ensure illumination is provided when needed without excessive energy use or ecological disturbance.

For urban policy-makers, the findings point to the importance of developing guidelines that address not only technical efficiency but also experiential quality and ecological sustainability. Policies promoting biodiversity-sensitive lighting could help cities position themselves as both livable and environmentally responsible. A key strength of this study lies in its combination of participatory workshops and surveys. Workshops provided qualitative insights into user perceptions, while the survey offered quantifiable measures that helped to generalize patterns. This mixed-methods approach captures both the subjective and collective dimensions of lighting experiences, offering richer evidence for design guidance than either method alone. On the other hand, this study has certain limitations. The sample size (144 respondents) is modest and may not fully represent all park users. The location specificity, data drawn from a single park, may limit generalizability across urban contexts with different cultural or environmental conditions. The data collection took place in winter, when patterns of park use are atypical due to shorter daylight hours, colder temperatures, and limited vegetation cover. These seasonal factors may have influenced both the frequency of visits and perceptions of lighting. Our next step extends data collection across multiple seasons to capture a more representative picture of user behaviors, biodiversity interactions, and lighting impacts throughout the year. Additionally, potential participation biases exist, especially among workshop participants, who may be more engaged or opinionated than the average user. Further research could explore experimental lighting trials, where different lighting configurations are tested in situ and evaluated by users. Longitudinal studies could capture seasonal variations, since perceptions of safety and ecological impact may change with daylight availability and biodiversity cycles. Additionally, examining cultural differences in nighttime park use could provide insights into how social norms shape lighting preferences across different contexts. Integrating ecological monitoring (e.g., impacts on insect populations or plant phenology) with social surveys would also allow for more holistic assessments of sustainable lighting design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; methodology, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; software, M.Z. and A.W.; validation, K.T.-D.; formal analysis, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; investigation, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; resources, K.T.-D.; data curation, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; writing—review and editing, R.A.; visualization, K.T.-D., R.A., K.K., A.J., M.Z., A.W. and M.B.-Z.; supervision, K.T.-D.; project administration, K.T.-D.; funding acquisition, K.T.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project NEW EUROPEAN BAUHAUS FOR INCREASING URBAN BIODIVERSITY (acronym: URBIO BAUHAUS) is co-funded by the European Union under grant agreement No. CE0200659 URBIO BAUHAUS within the Interreg Central Europe Programme. The project is co-financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under the programme “Internationally Co-Funded Projects”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences (protocol code N0N00000.0020.1.9.11.2024 and 18 November 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lis, A.; Zienowicz, M.; Kukowska, D.; Zalewska, K.; Iwankowski, P.; Shestak, V. How to Light up the Night? The Impact of City Park Lighting on Visitors’ Sense of Safety and Preferences. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 89, 128124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candolin, U. Coping with Light Pollution in Urban Environments: Patterns and Challenges. iScience 2024, 27, 109244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Dim the Lights for Pollinators and Plants at Night. 2023. Available online: https://www.fws.gov/story/2023-07/dim-lights-pollinators-and-plants-night (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ma, K.-M. Artificial Light at Night Decreases Leaf Herbivory in Typical Urban Areas. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1392262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łopuszyńska, A.; Bartyna-Zielińska, M. Lighting of Urban Green Areas—The Case of Grabiszyn Park in Wrocław. Searching for the Balance between Light and Darkness Through Social and Technical Issues. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 100, 00049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Aziz, F.A.; Ujang, N.; Hasna, M.F.; Mundher, R.; Shahidan, M.F.; Zhao, J. Pedestrian safety and security for female users in urban alleys: A systematic review. NDI 2024, 8, 674–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rijswijk, L.; Haans, A. Illuminating for Safety: Investigating the Role of Lighting Appraisals on the Perception of Safety in the Urban Environment. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 889–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portnov, B.A.; Saad, R.; Trop, T.; Kliger, D.; Svechkina, A. Linking Nighttime Outdoor Lighting Attributes to Pedestrians’ Feeling of Safety: An Interactive Survey Approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masullo, M.; Cioffi, F.; Li, J.; Maffei, L.; Scorpio, M.; Iachini, T.; Ruggiero, G.; Malferà, A.; Ruotolo, F. An Investigation of the Influence of the Night Lighting in a Urban Park on Individuals’ Emotions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Kim, M. The Relationship Between the Pedestrian Lighting Environment and Perceived Safety; Wichmann Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-87907-612-3. [Google Scholar]

- De Nadai, M.; Vieriu, R.L.; Zen, G.; Dragicevic, S.; Naik, N.; Caraviello, M.; Hidalgo, C.A.; Sebe, N.; Lepri, B. Are Safer Looking Neighborhoods More Lively? A Multimodal Investigation into Urban Life. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM international conference on Multimedia 2016, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 15–19 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, Z.; Sun, C.; Zhang, M.; Fan, C. Assessing Urban Vitality in High-Density Cities: A Spatial Accessibility Approach Using POI Reviews and Residential Data. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahm, J.; Johansson, M. Assessment of Outdoor Lighting: Methods for Capturing the Pedestrian Experience in the Field. Energies 2021, 14, 4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belčáková, I.; Świąder, M.; Bartyna-Zielińska, M. The Green Infrastructure in Cities as A Tool for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation: Slovakian and Polish Experiences. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubaszek, J.; Gubański, J.; Podolska, A. Do We Need Public Green Spaces Accessibility Standards for the Sustainable Development of Urban Settlements? The Evidence from Wrocław, Poland. IJERPH 2023, 20, 3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopij, G. Breeding densities of woodpeckers (Picinae) in the inner and outer zones of a Central European city. Sylvia 2017, 53, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Wrocław City Hall Study of Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development of Wrocław (Resolution No. L/1177/18, 11 January 2018). 2018. Available online: https://bip.um.wroc.pl/artykuly/szukaj?keyword=L%2F1177%2F18&where=none&type=all&dateFrom=&dateTo=&sort=score-desc&recaptcha_response= (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Balafoutis, T.; Skandali, C.; Niavis, S.; Doulos, L.T.; Zerefos, S.C. Light Pollution Beyond the Visible: Insights from People’s Perspectives. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Vega, C.; Zielinska-Dabkowska, K.M.; Schroer, S.; Jechow, A.; Hölker, F. A Systematic Review for Establishing Relevant Environmental Parameters for Urban Lighting: Translating Research into Practice. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosseri, R. Perceptions, Practices and Principles: Increasing Awareness of ‘Night Sky’ in Urban Landscapes. SURG 2011, 5, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).