1. Introduction

The construction of water conservancy and hydropower projects has caused a large number of reservoir resettlers to lose their homes and land. These people were forced to leave their original residences and, with government support, relocate to new areas to rebuild their lives. During the resettlement process, the relocation of affected populations has introduced a wide range of risks, including land loss, occupational transformation, and the disruption of social networks [

1]. The construction of water conservancy and hydropower projects, along with associated resettlement programs, must balance objectives such as energy supply, ecological protection, economic development, and social equity. Consequently, the reconstruction and sustainable development of livelihood systems have become central tasks in resettlement planning. On a global scale, most studies have centered on the reconstruction and development of the livelihoods of various types of land-lost farmers. However, due to differences in political systems and compensation policies among countries, research on involuntary resettlers—such as reservoir resettlers who are required to relocate—has found it difficult to produce universally applicable conclusions. For example, Paudel Khatiwada et al. [

2] explored the driving factors of livelihood development and poverty reduction strategies in rural Nepal; taking the Western Highlands in Guatemala as a case study, Hellin and Fisher [

3] analyzed the livelihood development risks faced by farmers in contexts of severe land scarcity, arguing that true poverty reduction through sustainable livelihoods can only be achieved by incorporating non-agricultural livelihood support; Nhamo et al. [

4] explored the interactions among various resources in South Africa’s Sakhisizwe Local Municipality to assess the livelihood sustainability of rural communities; meanwhile, studies on resettlers in flood-affected areas of Pakistan have paid particular attention to livelihood vulnerability in terms of socioeconomic conditions, community interpersonal relationships, and health and well-being [

5].

The core of sustainable livelihood development for reservoir resettlers lies in the accumulation of capital and capacity—a pattern that holds universal significance in impoverished regions worldwide [

6]. Through case studies conducted in developing countries across Africa, Coulibaly and Li [

7] emphasized that agricultural land serves as the fundamental form of livelihood capital. Most studies by Chinese scholars have concentrated on agriculture-dependent reservoir resettlers in various regions of China [

8,

9]. Currently, cultivated land resources in China are becoming increasingly scarce, and in certain regions, the environmental carrying capacity for agricultural resettlement models is severely limited. In response to this situation, it is necessary to explore rational and effective resettlement models that rely on minimal or no access to land, in order to break the cycle of “low livelihood capital resulting in limited livelihood development”. Accordingly, some regions have attempted land-constrained relocation and landless relocation instead of traditional agricultural resettlement. Landless relocation provides no new land to resettlers after their relocation, requiring them to adjust their original agricultural-based livelihood strategies. In contrast, land-constrained relocation provides resettlers with far less land than they originally owned, enabling them to retain a portion of their agricultural production activities. Therefore, under the new development context, identifying sustainable livelihood development pathways for resettlers affected by land-constrained or landless relocation represents both an urgent research need and an important intersection between China’s resettlement-focused urbanization policy and rural revitalization strategy. This study uses the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station in Guangdong Province as a case study. The livelihood development environment of these resettlers—defined by a farmland compensation model and non-agricultural employment opportunities in nearby industrial areas—differs substantially from that of traditional agriculture-dependent resettlers. Targeted research on the livelihood development mechanisms of this specific group can help bridge the existing research gap.

Currently, most research on the development of sustainable livelihoods among resettlers is based on the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach (SLA) proposed by the United Kingdom Department for International Development. This approach classifies livelihood capital into five categories: human capital, physical capital, financial capital, social capital, and natural capital. Its core aim is to reveal the sustainability of rural residents’ livelihoods through a relational analysis linking livelihood capital, livelihood strategies, and livelihood outcomes [

10]. Previous studies based on the SLA have investigated how resettlement and relocation affect resettlers’ livelihood capital and their production, as well as their living standards [

11,

12]. Research on the determinants of livelihood strategies has emphasized factors such as livelihood assets [

8], skill levels [

13], employment characteristics [

14], willingness to engage in employment [

15], and energy consumption structures [

16]. Scoones [

10] pointed out that traditional SLA has significant theoretical gaps: on the one hand, it overemphasizes the quantitative assessment of resettlers’ livelihood capital while neglecting the driving role of “behavioral intention” in the selection of livelihood strategies, and it fails to explain the differences in livelihood development paths among households with similar livelihood capital endowments; on the other hand, the traditional SLA’s research on livelihood sustainability lacks attention to long-term behaviors such as intergenerational transmission. These limitations are also reflected in the aforementioned studies: these studies have not systematically addressed the interaction between resettlers’ livelihood behaviors, their contextual environments, and their willingness to pursue development.

Moreover, limited attention has been given to the behavioral mechanisms that drive sustainable livelihood development. To address these limitations, several studies have explored improvements. Some research has considered resettlers’ intentions by integrating policy factors, rights protection, and development expectations [

17]. Li employed a composite index method to evaluate livelihood diversity and stability [

18], and other scholars have introduced livelihood capital as a contextual factor influencing resettlers’ intentions [

19]. Nevertheless, much of this work focuses on psychological elements affecting specific livelihood behaviors [

20,

21], while relatively few studies have adopted the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explore the broader dynamics of livelihood development among resettlers. According to the migration risk matrix proposed by Cernea [

1], shortages in financial capital and insufficient capabilities are identified as key drivers of poverty. In practical resettlement processes, these factors are further moderated by behavioral intentions. This perspective is further validated by Eidt et al. [

22]’s case study on smallholder farmers in the semi-arid Yatta region of Kenya: neglecting resettlers’ willingness to develop during livelihood reconstruction can lead to resource and power imbalances among vulnerable groups. Therefore, this study incorporates the dimension of behavioral intention, arguing that resettlers’ willingness to develop significantly influences their livelihood pathways. This addition provides theoretical justification for supplementing a subjective cognition dimension to the traditional SLA framework.

The TPB is a widely recognized framework in social psychology for understanding attitude–behavior relationships. This theory posits that behavioral intention is the main determinant of behavior, which in turn is shaped by three key antecedents: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. TPB has been proven to significantly enhance the explanatory power and predictive power of studies on human behavior. Existing TPB-based studies primarily examine the influence pathways of short-term, specific behavioral decisions [

21,

23], offering limited insight into mechanisms that support long-term behavioral sustainability. Additionally, these studies often lack an intergenerational perspective [

24], overlooking the strategic choices that migrant households make to achieve intergenerational mobility, particularly through educational investment. Field survey data suggest that resettlers’ subjective agency plays a pivotal role in the long-term sustainability of their livelihoods. From a temporal perspective, this study extends the behavioral intention in TPB to long-term willingness to develop, which can address the limitation of traditional TPB in insufficient attention to sustainability. From the perspective of development levels, the introduction of “investment in continuing education and children’s education” (Y3) not only reflects the emphasis on intergenerational education in the Chinese social context but also captures the intergenerational development strategies within households. Compared with the traditional SLA framework, resettlers’ cognitive appraisal of their own capital endowments and their intentions for development more accurately reflect their sustainable development capacity than do absolute capital levels. This study therefore explores the drivers of livelihood sustainability from a psychological standpoint, explicitly incorporates intergenerational development intentions expressed through investment in children’s education, and posits that integrating the TPB offers a more nuanced framework for explaining variation in resettlers’ livelihood development outcomes.

In summary, existing studies reveal several research gaps: a lack of investigation into resettlers’ livelihood development under land-constrained resettlement models; insufficiently integrated analysis of livelihood capital and behavioral intentions; and limited research perspectives addressing long-term development mechanisms and intergenerational dynamics. To bridge these gaps, this study constructs an integrated SLA–TPB framework and expands the measurement of indicators related to development willingness, using the resettlers of the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station as a case study. The main innovations and contributions are as follows:

Framework integration and methodological advancement. By combining the SLA with the TPB frameworks, this study establishes a comprehensive evaluation index system for assessing resettlers’ sustainable livelihood development capacity. This integration not only remedies the traditional SLA’s tendency to overlook subjective agency but also extends the TPB by incorporating indicators related to intergenerational educational investment and development willingness, thereby aligning the framework with the long-term perspective essential for resettlement livelihood research. The resulting analytical model enables more systematic exploration of the key factors and mechanisms shaping the sustainable development of resettlers’ livelihoods.

Empirical verification based on field data. Drawing on field surveys of 195 sample households and in-depth interviews with multiple stakeholders, the study yields robust quantitative evidence supporting its conclusions. A detailed analysis is conducted on the characteristics and disparities of livelihood capital, development willingness, and livelihood development capacity across resettlers adopting different livelihood strategies, followed by an examination of the hierarchical structure of their sustainable livelihood development capacity. These findings are consistent with the realities observed in resettlement practice.

Identification of obstacle factors and heterogeneity analysis. Through the application of the obstacle degree model, key constraints affecting resettlers’ sustainable livelihood development capacity are identified. The study further examines the heterogeneity of these obstacle degrees across different development willingness indicators and livelihood capital indicators under various livelihood types, thereby providing targeted and actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners.

Policy implications and localized contribution. Based on the evaluation outcomes and identified obstacle factors, the study proposes differentiated livelihood support pathways and development recommendations tailored to resettlers with distinct livelihood strategies in the context of the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station in Guangdong Province. In doing so, it contributes localized empirical evidence to the global body of research on resettlers’ livelihood sustainability.

Based on this research context, a research model is constructed to comprehensively assess the extent to which resettlers’ livelihood sustainability is influenced by both livelihood capital and behavioral intentions. This model examines the ability and potential of resettlers to achieve sustainable livelihoods after relocation and resettlement. This study utilizes field survey data from the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station resettlement area and introduces perceived behavioral control variables from the TPB as measurement indicators. In doing so, it extends the analytical framework of sustainable livelihood research. The analytic hierarchy process (AHP) is first adopted to calculate the weights of each indicator, which are then incorporated into the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) Method to compute the results of the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers. Based on these results, the k-means clustering method is applied for hierarchical classification, allowing for the study of the key characteristics of resettlers across different levels of sustainable livelihood capacity and their diverse range of livelihood strategies. Finally, an obstacle degree model is utilized to identify the key factors that influence the sustainable development of resettlers’ livelihoods.

By integrating resettlers’ livelihood contexts and strategies, the study explores the development pathways of sustainable livelihood capacity under the combined influence of internal and external drivers and proposes practical recommendations to support the sustained, high-quality development of resettlers’ livelihoods (

Figure 1).

2. Research Model and Methods

2.1. Research Area and Data Sources

The selected study area is Meizhou City, Guangdong Province, China, and the target population comprises resettlers from the Guangdong Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station. The choice of this site is based on the following considerations:

The planned installed capacity of the power station is 2400 MW, with primary functions including peak shaving, valley filling, frequency regulation, and emergency backup for the Guangdong power grid. As a key power source within the provincial grid, the project possesses significant research relevance and practical importance.

The project is being constructed in two phases, each with an installed capacity of 1200 MW. The first phase has been completed. A total of 2320 individuals were relocated, primarily to the Sankeng and Duanzhang’ao resettlement sites within the same county. The relocation and resettlement process was largely completed in April 2020. This study investigates the production and living standards of resettlers 3 years post-relocation (2023), thereby providing a foundation for evaluating their capacity for sustainable livelihood development in the post-resettlement period. Field surveys indicate that the resettlers have, at this stage, completed the initial processes of housing allocation, community integration, and employment adaptation. Their present livelihood conditions therefore provide an accurate reflection of the actual effectiveness of the resettlement policies.

The power station implemented a composite production resettlement model, which offers substantial research value. For the expropriated land, this approach combined one-time monetary compensation with long-term farmland compensation. Additionally, each resettled household was allocated 15 m2 of private vegetable plots per person. Land acquisition was substantially completed in 2018, and disbursement of the long-term farmland compensation began annually in 2021. Since then, significant changes have occurred in the livelihood capital of resettled households. These changes have led to variations in livelihood strategies and development intentions among households, which in turn influence the sustainability of individual household livelihoods and the broader resettlement area’s long-term development. Therefore, it is essential to investigate the key factors shaping the sustainable livelihood capacity of the resettlers.

Meizhou City possesses a strong foundation for economic and social development, with two major labor-intensive industrial clusters—textile and garment manufacturing, and electronic information—already established. These industrial clusters offer a favorable economic and welfare environment conducive to the livelihood transition of resettlers. Meanwhile, the two resettlement sites are equipped with comparable infrastructure, and resettlers uniformly benefit from supportive policies such as skills training, employment referrals, and interest-subsidized loans. Consequently, the objective environment is no longer the primary factor constraining differences in livelihood development. Using this region as a case study thus helps to underscore the differentiating role of subjective willingness in shaping resettlers’ livelihood outcomes.

The research data for this study were obtained through a field survey conducted in December 2023 at the resettlement sites of the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station in Guangdong Province. Initially, in-depth interviews were held with local officials responsible for resettlement, followed by an on-site assessment of the development environment at the resettlement sites. A stratified random sampling method was then employed to select sample households, and structured questionnaires were used to conduct one-on-one in-depth household interviews. The survey content included: basic demographic information of resettled household members as of 2023, household production and employment conditions, living standards, social adaptation, rights protection, and development intentions. A total of 195 valid questionnaires were collected.

2.2. Measurement Indicator System for the Sustainable Livelihood Capacity of Resettlers

Currently, SLA has been widely applied to the study of farmers’ livelihood capital, livelihood stability, and related topics. Some studies assess the sustainable development capacity of resettlers primarily through household income [

25], while others evaluate livelihood sustainability by comparing livelihood capital before and after relocation [

26].

Regarding specific indicators for measuring sustainable livelihood capacity, Gong [

27] estimated the development potential of resettlers’ livelihood systems using a social–ecological systems perspective; Ma [

28] constructed an evaluation indicator system based on three dimensions: livelihood capital, ecological environment, and farmers’ well-being; and Wang [

29] evaluated the coupling coordination among various livelihood capitals and developed a livelihood stability index. However, limited attention has been given to development intentions as a driving factor influencing livelihood development behaviors.

To address this gap, the present study integrates the SLA with the TPB and constructs a measurement indicator system for sustainable livelihood capacity across three dimensions: livelihood capital (R), livelihood environment (H), and development intention (Y) (

Table 1).

For livelihood capital measurement, this study builds upon the indicator system and methodology for resettlers proposed by Wu et al. [

9], while also incorporating the production and living conditions and the specific characteristics of the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station resettlers. Accordingly, four dimensions—human capital, physical capital, financial capital, and social capital—were selected for integrated evaluation. The corresponding measurement indicators and scoring criteria are presented in

Table 2. These indicators reflect the current status of the labor force, living conditions, financial resources and access to capital, and the availability of social networks and degree of organizational participation.

Regarding livelihood environment indicators, and based on previous studies [

30], Meizhou City’s development plans, and findings from the on-site survey, the assessment focuses on two aspects: infrastructure convenience (H1) and the level of participation in characteristic industries (H2). These indicators aim to reflect the external environment for resettlers’ livelihood development and employment opportunities.

In research concerning development intention, and drawing on Ajzen’s TPB, the livelihood development intention of resettlers is expanded into three dimensions: perception of and support for relevant policies (Y1), strength of development intention (Y2), and investment in continuing education and children’s education (Y3). TPB is among the most influential psychological theories addressing the relationship between attitudes and behavior. It asserts that behavioral intention is the most direct determinant of behavior, and that behavioral intention itself is shaped by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [

31]. The development intention of resettlers indirectly influences behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control by shaping beliefs related to livelihood development, and ultimately affects the selection of livelihood strategies and developmental trajectories.

Field investigations indicate that, although investment in the education of the next generation is not directly classified under human capital, it is instead driven by development intentions and perceptions—particularly recognition of educational importance—associated with perceived behavioral control. Notably, improving the educational attainment of the next generation significantly promotes labor transfer and enhances the overall livelihood level and risk resilience of resettler households. This study investigates resettlers’ investment in, and willingness to participate in, continuing education and skills training—for both themselves and their children. In doing so, it extends the perspective of short-term household human capital investment into a long-term, intergenerational framework of household development. Therefore, the Y3 indicator is innovatively introduced to capture decision-making control over long-term human capital investment, thereby addressing a recognized gap in traditional TPB applications concerning intergenerational mobility research.

The traditional SLA emphasizes the central role of natural capital; however, in resource-constrained contexts, the importance of financial and social capital increases significantly. For example, through empirical research conducted within the SLA framework, Wei et al. [

32] found that, in the context of China’s urbanization, human capital and behavioral intentions demonstrate significantly greater explanatory power for migration intention than natural capital. This suggests that livelihood capital indicators should be adjusted according to local contexts.

The various livelihood capital indicators presented in

Table 2 were selected based on findings from field surveys: for the measurement of human capital, the primary indicator is the overall quality of household labor, with basic employment status serving as the core evaluation criterion. Regarding physical capital, field survey results from 195 sample households indicate that, aside from small household vegetable plots, resettler households possess minimal surplus land. In 2023, the per capita cultivated garden area was only 20 m

2. As a result, natural capital indicators—such as cultivated land area, cultivation radius, and land utilization rate—are excluded from the analysis. Instead, per capita housing area, the decoration level of resettlement housing, and the diversity of household durable goods are adopted as the principal indicators for assessing physical capital.

Financial capital refers to the stock of immediately available financial resources and the channels through which funds can be accessed. Accordingly, per capita disposable income and the number of income sources are retained as core indicators. In addition, the number of borrowing channels is included to quantify a household’s borrowing capacity and financial flexibility in emergency situations, thereby reducing the influence of latent variables in the evaluation of livelihood strategies. Social capital is used to capture the extent of social support accessible to resettlers during the process of sustainable livelihood development.

2.3. Comprehensive Measurement Method

2.3.1. Determination of Indicator Weights Using the AHP

Given the specific context of resettlement, the AHP provides an intuitive means of representing the relative weights of various indicators and demonstrates strong applicability. Following the computational approach outlined in reference [

9], the Delphi method and the Saaty 1–9 scale were employed to perform pairwise comparisons of the relative importance among indicators within each indicator set. Upon verification of the consistency of the judgment matrices, AHP was applied to determine the weight

of each indicator at its corresponding hierarchical level.

2.3.2. Comprehensive Evaluation Using the TOPSIS Method

The TOPSIS method is a widely used multi-criteria decision-making approach that fully utilizes the original data and can effectively reflect differences in performance across resettled household samples regarding their sustainable livelihood development capacity. Based on the construction of a normalized matrix derived from the original data, TOPSIS calculates the distance between each evaluation object and both the optimal and worst solution vectors, which serve as the basis for assessing relative performance [

9].

Assume there are n sample households and m evaluation indicators. An data matrix is constructed and normalized using the min–max method to obtain a standardized matrix , where represents the standardized value of the j-th indicator for the i-th household. Let and respectively denote the optimal and worst values for the j-th indicator.

Using the indicator weights

obtained via AHP, the distance from the positive ideal solution

and the negative ideal solution

for each household is calculated as shown in Equation (1). Subsequently, the comprehensive score of sustainable livelihood capability for the

i-th sample household is obtained according to Equation (2).

2.4. Hierarchical Classification Using the K-Means Clustering Method

The K-means clustering method is a distance-based algorithm that employs distance as a measure of similarity. It effectively classifies sample data to establish grading standards and, compared with other clustering techniques, demonstrates superior clustering performance and faster convergence speed [

33].

The specific procedure is as follows: After obtaining the comprehensive measurement results of resettled households’ capacity for sustainable livelihood development, the number of K clusters is determined based on practical needs. Initial mean points m1, m2, …, mk are then selected according to the distribution of the dataset. The distance between each data point and each mean point is calculated, and each data point is assigned to the cluster associated with the nearest mean point, thereby minimizing the within-cluster sum of squared errors.

For each cluster formed, the centroid (i.e., geometric center) is recalculated and designated as the new mean point. The data are then re-clustered based on the updated centroids. This iterative process of assignment and updating continues until the convergence criterion is met, such as minimal or no further changes in the cluster centroids.

2.5. Obstacle Degree Model

The ranking of indicator obstacle degrees is employed to identify key limiting factors, and the obstacle degree model is applied to determine the bidirectional obstacle factors affecting the sustainable livelihood development of reservoir resettlers [

34].

2.5.1. Calculation of the Deviation Between a Single-Factor Indicator and the Ideal Performance Target

As shown in Equation (3), the degree of deviation between the

j-th indicator of the

i-th resettler and the ideal target value is calculated:

where

denotes the normalized value of the

j-th indicator for the

i-th resettler (using the range method), and

represents the deviation between this normalized value and the ideal target value (set as 1).

2.5.2. Calculation of the Obstacle Degree

According to Equations (4) and (5), the obstacle effect (i.e., obstacle degree) of each individual indicator is calculated both at the individual level and as an average across all sample households. A higher obstacle degree indicates a greater hindering effect on sustainable livelihood capacity, whereas a lower value suggests a weaker influence.

where

denotes the obstacle degree of the

j-th factor on the sustainable livelihood capacity of the

i-th resettler, and

represents the overall obstacle degree of the

j-th factor averaged across all resettlers.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of the Sustainable Livelihood Capacity of Resettled Households

4.1.1. Comparative Analysis of Livelihood Capital Under Different Livelihood Strategies

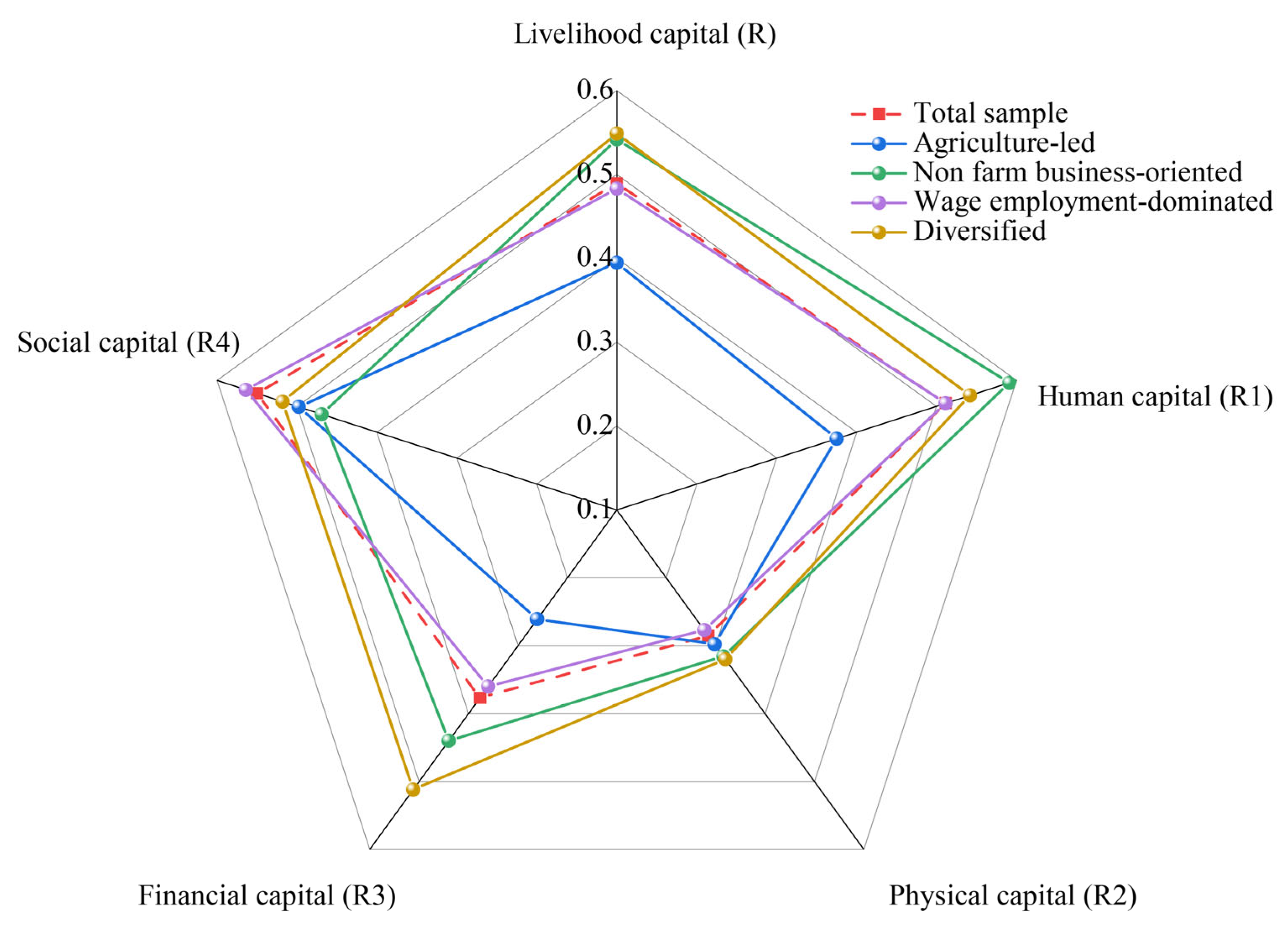

The data analyzed in this study were obtained from a field questionnaire survey conducted in 2023, involving 195 sample households resettled due to the Meizhou Pumped Storage Power Station project. First, the AHP was used to determine the indicator weights for livelihood capital, with all judgment matrices passing the consistency test. Subsequently, the TOPSIS method was applied to calculate the average livelihood capital values for households categorized under the four identified livelihood strategies. The corresponding results are presented in

Table 4 and

Figure 2.

Based on the composite scores of livelihood capital, the ranking of the four livelihood strategy types adopted by resettlers is as follows: diversified livelihoods (0.549) > non-farm business-oriented livelihoods (0.542) > wage-employment-dominated livelihoods (0.483) > agriculture-led livelihoods (0.395).

Due to land expropriation and relocation, the cultivated land area available to resettler households has significantly decreased. Currently, most households maintain only small kitchen gardens. The long-term land compensation provided by the project has helped to ensure a basic standard of living for certain vulnerable groups. Among households with sufficient livelihood capital, those previously engaged in agriculture under agriculture-led strategies have gradually transitioned toward more diversified and integrated livelihood approaches.

Households following agriculture-led strategies recorded the lowest composite score for livelihood capital. These households remain largely dependent on agriculture, transfer income, and long-term land compensation. Typically, they include a high proportion of individuals with limited or no labor capacity—such as elderly persons, individuals with disabilities, students, and infants—and the available labor force often lacks vocational skills. Consequently, such households possess relatively limited human, physical, and financial capital. However, due to their relatively low migration frequency and sustained ties with relatives and neighbors, they have developed a certain level of social capital through interpersonal relationships and neighborhood networks.

In contrast, households adopting diversified or non-farm business-oriented strategies generally exhibit strong performance across all dimensions of livelihood capital. This is attributable to the presence of household members with diverse work experience and vocational skills, and in some cases, active engagement in investment or entrepreneurial activities. Wage-employment-dominated strategies are the most prevalent among resettler households; however, they tend to underperform compared to diversified and non-farm business-oriented households in terms of physical and financial capital. This is primarily because some members of the labor force are limited to labor-intensive occupations. In particular, middle-aged and elderly resettlers are constrained by factors such as advanced age, lower levels of education, and insufficient production skills. These limitations restrict access to higher-income opportunities and contribute to relatively unstable employment conditions.

4.1.2. Analysis of the Measurement Results of Resettlers’ Sustainable Livelihood Capacity

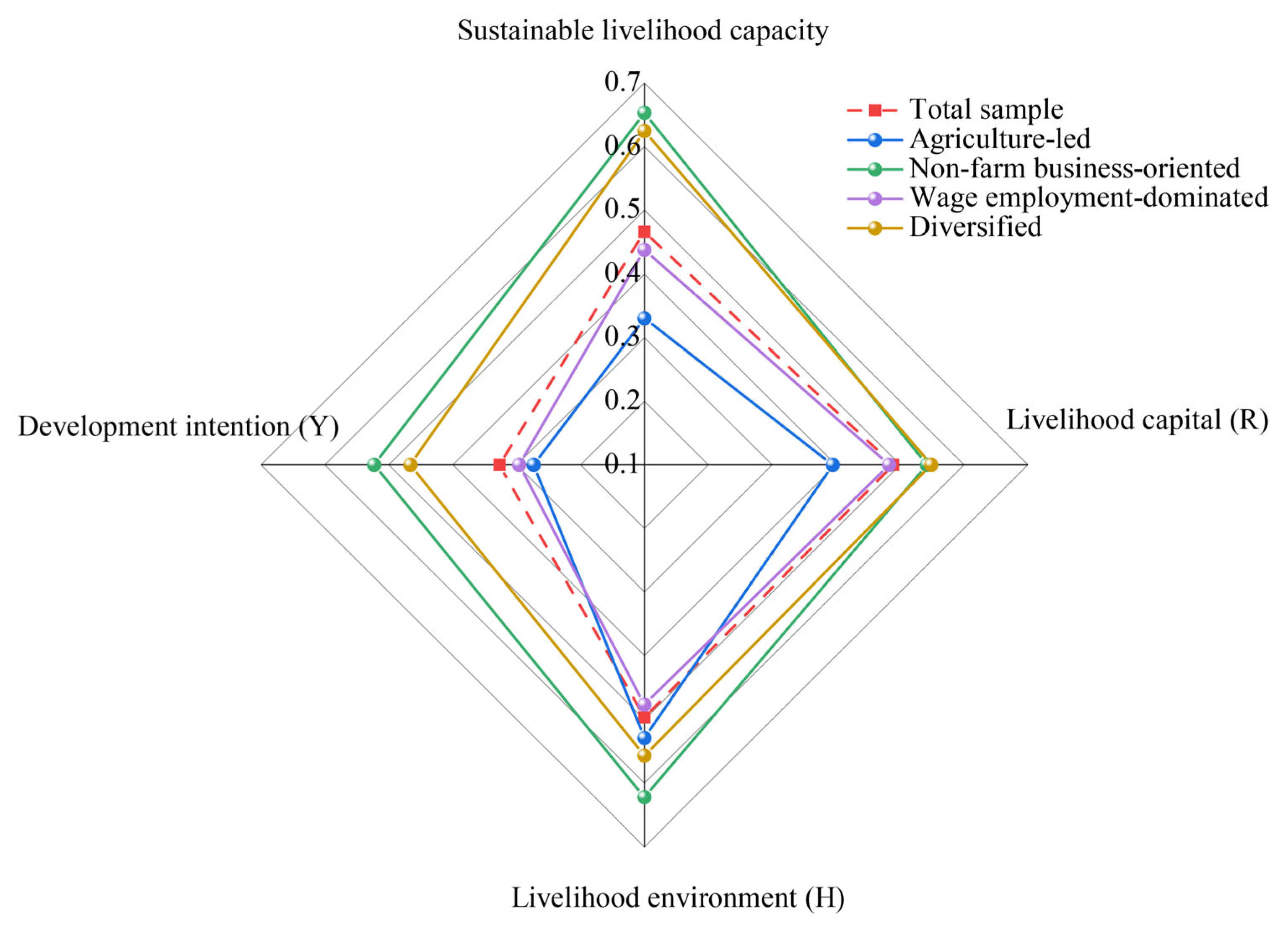

The AHP was used to assign weights to the evaluation indicators. Based on these weights, the TOPSIS method was applied to perform a comprehensive measurement of sustainable livelihood capacity among resettler households adopting different livelihood strategies. Based on field survey data from 195 resettler households, a comprehensive measurement of the sustainable livelihood development capacity of resettler sample households was conducted by category according to their livelihood strategies. The statistical results are summarized in

Table 5 and visualized in

Figure 3.

Significant differences exist among resettler households with varying livelihood strategies in terms of livelihood capital and development willingness, while variation in livelihood environmental conditions remains relatively small (standard deviation = 0.06). Field investigation results suggest that these disparities are primarily attributable to differences in participation in characteristic industries—particularly between wage-employment-dominated households and other groups. Additionally, the interaction among the three dimensions (capital, environment, and willingness) exerts varying degrees of influence on the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers.

The overall ranking of sustainable livelihood development capacity is as follows:

Non-farm business-oriented (0.653) > Diversified (0.625) > Wage-employment-dominated (0.438) > Agriculture-led (0.330).

According to resettler interviews and household survey data, households adopting non-farm business-oriented and diversified strategies exhibit significantly higher development willingness (average score: 0.523). This can be attributed primarily to the following factors:

Industrial agglomeration effects in the host area. The presence of nearby industrial parks has generated employment opportunities in sectors such as textiles and electronic assembly. In addition, some households have entered supporting service sectors—for example, operating breakfast stalls or offering ride-hailing services. Among the nine interviewed non-farm business operators, seven explicitly noted that “proximity to industrial zones makes business more stable.”

Synergistic advantages between financial and human capital. These households generally possess prior experience in wage employment or business operations, enabling them to better mobilize resources and adapt to changing livelihood conditions.

By contrast, although wage-employment-dominated households also reside near industrial zones, they often lack business capital and exhibit limited willingness to engage in entrepreneurial activities. This constrains them to low-skill employment and perpetuates a form of path dependence as “mere wage workers” [

39]. As a result, their overall development willingness is relatively weak.

Field survey results reveal a significant correlation between investment in continuing education and children’s education (Y3) and actual educational behaviors. Among the 22 households with a Y3 score above 3, 86.4% (19 households) had children enrolled in senior high school or higher education, and 72.7% (16 households) had resettlers themselves participating in skills training or enrolling their children in extracurricular programs. These behaviors align closely with the technical job requirements of industrial parks near the resettlement areas. Households demonstrating a strong willingness to develop are actively building an intergenerational development chain—pursuing income growth and long-term livelihood advancement through dual efforts: improving their own skills and investing in their children’s education. In contrast, among households with a Y3 score below 2, the average educational attainment of resettler families remains relatively low.

This discrepancy suggests that resettlers’ willingness to invest in continuing education and skills training—for both themselves and their children—has partly translated into actual behavior. This finding not only confirms the motivating role of behavioral intention in shaping actual actions, as postulated by the TPB, but also underscores the significant value of the Y3 indicator for examining the intergenerational development strategies of resettler livelihoods.

4.2. Classification Study on the Sustainable Livelihood Capacity of Resettlers

The K-means clustering method was applied to classify the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers. Based on practical classification experience and research requirements, the value of K was set to 3, corresponding to three levels of sustainable livelihood capacity: weak, medium, and strong. Following iterative convergence, the final cluster center values were 0.311, 0.470, and 0.671. The number of resettler households assigned to each cluster was 73, 68, and 54.

In addition, based on field survey data from 195 resettler households, using Equation (6), the Simpson Diversity Index (S) was calculated for each of the three livelihood capacity groups—weak, medium, and strong—as well as for resettler households adopting different livelihood strategies. The distribution and corresponding results are presented in

Table 6.

Based on the data presented in

Table 6, most agriculture-led resettler households exhibit a sustainable livelihood capacity classified as “weak,” with a livelihood strategy diversity index of 0.251—indicating a highly unbalanced income structure. According to the dimensional evaluation results in

Table 5, although engagement in nearby agricultural activities has increased this group’s participation in characteristic industries—resulting in a relatively high score for the livelihood environment dimension—these households often fall into a self-reinforcing cycle of “insufficient livelihood capital → lack of development willingness and endogenous motivation → reduced employment enthusiasm and inadequate income” during the process of sustainable development.

Wage-employment-dominated households display a relatively even distribution across the three capacity levels, though they are skewed toward the “medium” and “weak” categories. Among them, 42.7% are classified as having weak sustainable livelihood capacity, with a livelihood strategy diversity index of 0.383, reflecting a mildly unbalanced income structure. Field surveys and interviews reveal that although these households benefit from proximity to industrial parks, many resettlers are engaged in labor-intensive employment—such as textile production, food processing, basic construction services, and electrical manufacturing. However, due to limited educational attainment, these individuals often lack the capacity or motivation to respond to innovation- or entrepreneurship-oriented policies, resulting in occupational stagnation.

In contrast, non-farm business-oriented and diversified households generally demonstrate strong sustainable livelihood capacity. The livelihood strategy diversity index for non-farm business-oriented households is 0.430, suggesting a relatively balanced income composition, while that of diversified households reaches 0.639, indicating broad engagement in multiple livelihood activities and a well-distributed income structure. These two household types tend to have a high proportion of non-farm income and are able to capitalize on resettlement opportunities to innovate and optimize both their income structure and livelihood strategies. They are also more willing to invest time, labor, and financial resources in improving household quality of life, particularly in the education and development of their children. As a result, they enjoy relatively favorable production and living conditions, and exhibit strong livelihood resilience and sustained development motivation.

4.3. Analysis of Obstacle Factors Affecting the Sustainable Livelihood Capacity

To further examine the primary factors influencing sustainable livelihood capacity, the obstacle degree model was applied. Beginning with nine indicator-level variables, the obstacle degree for each indicator was calculated for the total sample as well as across the four livelihood strategy categories. Based on the magnitude of the calculated obstacle degrees, the top five indicators were identified as the key obstacle factors constraining the sustainable livelihood development of resettlers.

The obstacle degrees of these major limiting factors, disaggregated by household type, are presented in

Table 7 and illustrated in

Figure 4.

The results indicate that, among resettlers of the Meizhou pumped-storage power station, the indicator-level obstacle factor exerting the greatest influence on sustainable livelihood capacity is willingness to develop (Y2), with an average obstacle degree of 0.364. This is followed by financial capital (R3, 0.159), human capital (R1, 0.147), physical capital (R2, 0.132), and investment in continuing education and children’s education (Y3, 0.117).

A comprehensive analysis of both frequency of occurrence and average obstacle degrees confirms that, across the total sample and all four livelihood strategy categories, these five indicators consistently rank among the top five. As such, they are identified as the primary obstacle factors affecting the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers under different livelihood strategies. The average obstacle degrees for these five factors are as follows: 0.201 for Y2, 0.160 for R3, 0.156 for R1, 0.136 for R2, and 0.121 for Y3.

Among them, willingness to develop, particularly in terms of entrepreneurship, employment creation, and pursuit of stable work, emerges as the most significant constraint. This finding underscores the critical importance of fully mobilizing resettlers’ initiative and motivation as a prerequisite for advancing livelihood development. While financial capital, human capital, and physical capital serve as essential preconditions and tangible foundations for improving livelihood capacity, the investment in continuing education and children’s education functions as a long-term safeguard for human capital development and intergenerational advancement.

Therefore, enhancing the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers not only depends on their individual effort but also requires increased support and targeted interventions from the government and society. To fully stimulate enthusiasm for entrepreneurship and employment—especially among resettlers influenced by a dependency mindset characterized by passivity and reliance (“waiting for, relying on, and asking for” assistance)—grassroots resettlement personnel should intensify public outreach, strengthen policy communication, and provide clear explanations. These efforts can encourage resettlers to better harness their own capacity for self-development and self-reliance.

5. Discussion

5.1. Applicability of the Research Model

The integrated SLA–TPB framework constructed in this study comprehensively evaluates the sustainable livelihood development capacity of resettlers from three dimensions: livelihood capital (R), livelihood environment (H), and willingness to develop (Y).

The traditional SLA framework tends to focus primarily on capital stock [

29] while overlooking the mechanisms that drive behavior. In contrast, the TPB emphasizes subjective intention [

31] but is seldom integrated with livelihood capital. Matthies et al. [

40], in a study covering five European countries, argued that one-dimensional development cannot maintain long-term sustainability.

In this study, willingness to develop (Y) is incorporated into the analysis as a perceived behavioral control variable, and the indicator system is refined to align with the specific conditions of land-constrained resettlement. The empirical results are consistent with the findings from field surveys, indicating that the proposed framework possesses strong theoretical adaptability.

Applying this model to the case of resettlers from the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station demonstrates that differences in livelihood capacity scores between non-farm business-oriented households and agriculture-led households stem not only from disparities in financial capital and other objective resources but also significantly from differences in willingness to develop. This finding helps explain why households with similar livelihood capital endowments often adopt different livelihood strategies—showing the model’s strong explanatory power in practice.

From an international research perspective, the model proposed in this study further expands the analytical dimensions of Cernea’s migration risk matrix. Whereas Cernea’s framework focuses primarily on objective risks—such as land loss and occupational transition—this study reveals, through the inclusion of willingness to develop (Y), that insufficient willingness to develop represents a more deep-seated and hidden obstacle than the mere shortage of capital. This conclusion aligns with Qayum et al. [

41]’s findings on resettlers in various regions of Pakistan, thereby enriching global research on the behavioral mechanisms of reservoir resettlers.

5.2. Hierarchical Characteristics and Causes of Resettlers’ Sustainable Livelihood Development Capacity

Empirical results indicate that the sustainable livelihood development capacity of resettlers in Meizhou exhibits a distinct hierarchical pattern: Non-farm business-oriented (0.653) > Diversified (0.625) > Wage-employment-dominated (0.438) > Agriculture-led (0.330) (

Table 5,

Figure 3). This finding is consistent with the conclusion of “diversified livelihoods being optimal” in Gong [

27]’s case study. The causes of these differences are primarily reflected in the synergistic interactions among livelihood capital, livelihood environment, and willingness to develop.

Non-farm business-oriented and diversified households are characterized by the dual empowerment of livelihood capital and a favorable environment. These households maintain a livelihood portfolio combining non-farm operations, wage income, and agricultural cultivation, resulting in diversified income sources and ample financial capital. They make full use of the industrial clusters surrounding the resettlement areas to conduct business—such as operating breakfast shops or hardware repair shops, which can yield monthly profits of up to 10,000 yuan. The synergy among livelihood capital, environment, and willingness to develop gives these households significantly higher livelihood capacity than others.

Moreover, these two groups belong to the high willingness-to-develop category. Building on a foundation of stable short-term income, they enhance their long-term development potential by increasing family investment in education. This aligns with Ramilan et al. [

42], who argue that “livelihood strategies with strong resource integration capacity demonstrate higher resilience,” and corroborates theoretical prediction by Scoones [

10] that “diversified livelihoods are a core strategy for coping with vulnerability.”

As the largest group among all sampled households, wage-employment-dominated resettlers exhibit a moderate level of sustainable livelihood development capacity. Their livelihood foundation largely relies on the employment dividends generated by the industrial clusters surrounding the resettlement areas. The shared employment environment fosters frequent social interactions among resettlers, and the resulting improvement in social capital provides additional support. However, as analyzed in

Section 4.1.2, path dependence on stable wage income reduces some resettlers’ willingness to develop, as they tend to avoid risk-taking. Furthermore, shortages in human capital confine them to low-skill, low-value-added positions, making it difficult to break free from the dilemma of weak livelihood motivation.

Agriculture-led households, on the other hand, are constrained by both limited livelihood capital and low willingness to develop. The shortage of arable land and lack of labor skills—largely due to family structure deficiencies discussed in

Section 4.1.1—hinder their development. This situation parallels the challenges faced by smallholder farmers in Kenya documented by Eidt et al. [

22], where both groups struggle to transform their livelihood strategies due to limited control over critical resources.

These findings closely align with the conclusions of Zhou and Chi [

43] on Chinese rural households. Their research demonstrates that non-farm employment and wage income among resettlers significantly reduce household dependence on land, encouraging farmers to lease out farmland to release idle land costs and reinvest the resulting resources in non-farm livelihoods—thus forming a positive cycle of non-farm livelihood capital accumulation.

5.3. Characteristics of Obstacle Factors to Resettlers’ Sustainable Livelihood Development Capacity and Practical Implications

Results from the obstacle degree model (

Table 7,

Figure 4) show that the core obstacle factors affecting resettlers’ sustainable livelihood development capacity, ranked by average obstacle degree, are as follows: willingness to develop (Y2, 0.221) > financial capital (R3, 0.159) > human capital (R1, 0.147) > physical capital (R2, 0.132) > investment in continuing education and children’s education (Y3, 0.117).

This finding challenges the traditional premise of the SLA that objective capital determines livelihood capacity. The divergence arises primarily from the solid economic foundation and welfare support available in the resettlement areas, which safeguard the basic living standards of resettlers. In the current livelihood context of Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station resettlers, willingness to develop now poses a greater constraint on sustainable livelihood development than the amount of livelihood capital possessed.

As Rimmer et al. [

44] incorporated women’s labor-force participation into the human capital dimension in their research, the analysis of obstacle factors in this study must likewise be extended to non-directly productive dimensions—such as skills training—to more comprehensively reflect sustainability. Moreover, the types and degrees of obstacle factors vary among different livelihood categories, necessitating targeted policy measures in practical implementation.

The obstacle of willingness to develop (Y2) is mainly reflected in resettlers’ strong dependence on existing livelihood models and their heightened fear of transformation risks, a tendency especially apparent among wage-employment-dominated households. Interviews reveal that many of these resettlers have grown accustomed to their current work patterns, and their pursuit of stability discourages them from pursuing entrepreneurial ventures or skill upgrading—thereby inhibiting their development willingness.

The obstacle of financial capital (R3) is most pronounced among agriculture-led households. These families face both insufficient livelihood capital and low willingness to develop. Nevertheless, the per capita disposable income of all resettler households has already reached the poverty-alleviation benchmark, underscoring the positive role of policy support in mitigating capital constraints.

Regarding human capital (R1), the obstacle is concentrated in the mismatch between labor skills and industrial demand, particularly among middle-aged resettlers. Owing to limitations in age, educational background, and technical capacity, this group often possesses only basic manual labor skills that do not align with the high-tech requirements of surrounding industries. Consequently, their potential for income growth and livelihood advancement remains limited. This phenomenon resonates with the aging inheritance gap identified by Chen et al. [

45] in their case study of Japan. It also offers an important lesson for the present case: reskill and enhance the adaptability of resettlers over 50 years old to prevent livelihood stagnation caused by an aging labor force.

5.4. Research Limitations

(1) This study uses only cross-sectional data from 2023, collected three years after the resettlers’ relocation and resettlement, which results in certain limitations regarding data dimensionality. The survey incorporated household income retrospection and adaptability assessments through questionnaires and interviews. Respondents generally indicated that by this stage, their lifestyles, income sources, and community relationships had stabilized, meaning that their current livelihood conditions can effectively reflect both the actual outcomes of resettlement policies and the basic capacity for household sustainable development, thus exhibiting a degree of representativeness.

However, the absence of panel data from intermediate stages makes it impossible to fully quantify or track the dynamic evolution of resettlers’ livelihood capacities throughout the entire relocation process. Additionally, the long-term intergenerational transmission effect of the Y3 indicator—which captures investment and willingness of continuing and children’s education—has not been comprehensively quantified. This limitation will be addressed in future longitudinal follow-up surveys.

Subsequent research will therefore conduct follow-up surveys on the same group of sample households to verify the stability of the obstacle factors identified in this study and to explore the long-term evolution patterns of livelihood strategies, which will form one of the core directions of future research.

(2) The research case in this study focuses exclusively on the resettlers of the Meizhou Pumped-Storage Power Station, which restricts the regional generalizability of the findings. The case is shaped by two distinct project characteristics:

First, the presence of a mature industrial cluster around the resettlement area provides substantial non-farm employment opportunities for resettlers—unlike many resettlement sites in Western China, where such industrial foundations are absent.

Second, the land-constrained resettlement model ensures basic agricultural income security, and the implementation of long-term cultivated land compensation offers sustained income guarantees, differing from one-time compensation approaches in other regions.

Furthermore, based on the specific nature of the Meizhou resettlement project, the SLA–TPB model indicators were optimized to reflect these contextual characteristics. As a result, the comprehensive measurement model developed here has strong contextual relevance, but may not be directly generalizable to other types of resettlement projects. Future research should therefore conduct comparative studies in provinces such as Sichuan and Zhejiang to test the framework’s adaptability across different regional contexts and project types.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Conclusions

Using resettlers of the Meizhou pumped-storage power station as a case study, this paper integrates the systematic perspective of the SLA framework with perceived behavioral control variables from the TPB to examine the key factors influencing the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers across different livelihood strategies. By combining the livelihood strategy diversity index with obstacle factor identification, the underlying mechanisms of sustainable livelihood development were systematically analyzed. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers is jointly influenced by livelihood capital, livelihood environment, and willingness to develop. In terms of overall livelihood capital, the ranking is: diversified > non-farm business-oriented > wage-employment-oriented > agriculture-oriented, which aligns with the ranking based on the livelihood strategy diversity index. According to the K-means clustering results, the corresponding levels of sustainable livelihood capacity are classified as strong, medium, and weak, with the ranking being: non-farm business-oriented > diversified > wage-employment-oriented > agriculture-oriented. This consistency with field survey data suggests that the comprehensive evaluation model used in this study is effective for assessing the sustainable livelihood capacity of resettlers.

(2) Willingness to develop emerges as the most significant obstacle factor. Wage-employment-oriented resettlers demonstrate limited initiative in responding to innovation and entrepreneurship policies or in pursuing occupational transitions, which constrains their long-term development potential. Agriculture-oriented households, when lacking financial, human, and physical capital, are prone to falling into a cyclical trap of “low livelihood capital–insufficient development willingness.” In contrast, non-farm business-oriented and diversified households show clear advantages in income generation and development capacity.

(3) In light of new demands in the post-resettlement development stage, targeted policy interventions should be formulated based on the differentiated obstacle factors. For agriculture-oriented households, small-scale microcredit programs should be introduced to address financial capital shortages, alongside agricultural technical training to enhance human capital. For wage-employment-oriented households, expanding vocational intermediary services to reduce information asymmetries and increasing subsidies for children’s education can help strengthen development willingness.

At the community level, local resource advantages should be consolidated to expand collective village economies, promote characteristic industry development, and improve both financial and physical capital endowments. Multi-level, multi-channel, and diversified training programs—tailored to the industrial context and actual needs of resettlers—should be implemented to enhance skills, strengthen capacity building, and support education in innovation and entrepreneurship. Emphasis should be placed on stimulating entrepreneurial motivation, steadily improving cultural and production competencies, addressing weaknesses in employment and entrepreneurial capacity, and enhancing long-term development enthusiasm among resettlers. Ultimately, by elevating human capital, the foundation for sustainable livelihood capacity can be significantly strengthened.

6.2. Practical Proposals

To meet the new requirements of resettlers in the subsequent stages of development, targeted measures should be proposed based on the differences in obstacle factors. Drawing on the ideas of Ferraz et al. [

6], policies can be designed for resettlers with diverse livelihood types by integrating livelihood diversification with sustainable livelihood development capacity.

(1) For agriculture-led resettler households, microcredit programs should be introduced to address obstacles related to financial capital, while human capital should be strengthened through training in agricultural technologies. International experience can also inform local practice: Papageorgiou et al. [

46] found in rural India that single credit interventions have limited impact and must be combined with capacity-building programs. Similarly, Germany promoted farmers’ livelihood transitions by integrating green technology training with credit subsidies [

47]—a logic applicable to the local context.

Specifically, Meizhou’s local government should organize relevant departments to implement a “Resettler Livelihood Special Loan” program, designing credit schemes that support agricultural production needs such as tea and vegetable cultivation. The loan amount and repayment period should be calculated in alignment with local agricultural cycles, and interest rates should be set below those of ordinary agricultural loans to reduce repayment pressure. Considering that middle-aged and elderly resettlers may be reluctant to take loans, awareness campaigns showcasing successful cases and village-level collective applications can help lower psychological barriers. Meanwhile, quarterly training sessions on topics such as tea quality improvement and vegetable pest and disease control should be held at resettlement village committees to ensure effective technology adoption. These measures will help agriculture-led households break the cycle of low livelihood capital and weak development willingness.

(2) For wage-employment-dominated resettler households, efforts should focus on mitigating information asymmetry and enhancing education investment to facilitate a shift from stable employment to high-quality employment. Specifically, vocational intermediary services should be improved, and education subsidies should be expanded to support both continuing education and children’s schooling. It is recommended to establish a “Resettler Employment Service Station” within resettlement areas, linking it with key enterprises in surrounding textile and electronics industrial parks, hosting targeted job fairs, and providing resume-writing and interview training.

For resettlers aged over 45, short-term training programs—such as electronic assembly operations—should be launched based on local industrial demand to address skill shortages among middle-aged workers. In addition, intergenerational development willingness should be strengthened by offering children’s education subsidies and organizing technical field visits in industrial parks for resettlers and their children, illustrating the link between education and career mobility. Such initiatives will increase resettlers’ motivation to invest in skills training and education, helping to overcome low development willingness. This aligns with Sridhara et al. [

48], who emphasized driving overall livelihood improvement through key indicator interventions, addressing the core obstacles of both information asymmetry and insufficient willingness to develop.

(3) For diversified and non-farm business-oriented households—those already exhibiting high sustainable livelihood development capacity—policies should emphasize development-oriented support, focusing on leveraging comparative advantages and upgrading entrepreneurship. Following the “government–community–farmer” collaborative framework proposed by Chen et al. [

45], relevant departments should establish a “Resettler Livelihood Coordination Group” to design personalized livelihood portfolio plans, helping households optimize their income structure.

Based on local industrial features and the real needs of resettlers, multi-level, multi-channel, and multi-format training programs should be offered to enhance skills and cultural competencies. The focus should be on innovation and entrepreneurship incentives, aiming to improve resettlers’ overall human capital—including both technical proficiency and cultural literacy. Furthermore, these households should be encouraged to assume demonstration and leadership roles, sharing entrepreneurial experiences to inspire broader community participation in innovation and sustainable development. In essence, boosting human capital will serve as the foundation for the long-term sustainable development of resettler livelihoods.

(4) For the development of resettlement areas as a whole, resource integration and collective economic expansion should be prioritized to promote characteristic industries and strengthen both financial and physical capital of resettlers. Village collectives should establish partnerships with nearby industrial parks, developing supporting industries such as textile auxiliary processing and staff canteen operations. Profits generated by these collective ventures should be partially reinvested in skills training and resettler employment subsidies.

A multi-department coordination mechanism should be established—comprising government policy formulation, collective implementation, enterprise-based job supply, and financial institution funding—to avoid policy fragmentation. This will consolidate the development foundation of resettlement areas and create a positive, self-reinforcing development cycle for the resettler community as a whole.