1. Introduction

Air pollution control at the county level in China has become a key challenge in achieving regional environmental equity and sustainable development [

1,

2]. The economic structure, characterized by a dependence on traditional energy sources and agriculture, has led to typical county-level pollution features, particularly sulfur dioxide (SO

2) and ammonia (NH

3) emissions [

3]. SO

2 primarily originates from coal combustion and industrial processes, posing direct threats to public health [

4,

5]. Additionally, it undergoes atmospheric conversion to generate sulfate, significantly contributing to acid rain and smog pollution [

6]. On the other hand, NH

3, originating from agricultural activities, reacts with acidic substances in the atmosphere to form secondary inorganic aerosols, which significantly drive the generation of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), exacerbating regional air quality fluctuations [

7,

8]. Although national policies such as the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan, the Three-Year Action Plan to Win the Battle for Blue Sky, and the Action Plan for Continuous Improvement of Air Quality have been implemented, achieving significant results at the urban level [

9,

10,

11], these efforts have encountered the challenge of “last-mile” implementation in many county-level regions. The rigidity of the industrial structure, limitations in environmental regulatory capacity, and fiscal constraints at the local level together form a bottleneck to the sustained improvement of air quality in counties. In this context, the National Intellectual Property Strong County Project (NIPSC), which is a policy tool driven by innovation incentives, offers new possibilities for controlling direct pollutants at the county level.

The NIPSC represents a significant initiative in China’s grassroots governance system, aimed at strengthening the strategic role of intellectual property in regional innovation, industrial upgrading, and environmental governance [

12]. This policy transcends the traditional top-down intellectual property governance model by granting county-level governments greater institutional autonomy to develop local intellectual property systems, promote the construction of patent alliances, and facilitate the commercialization of patent outcomes. This institutional arrangement closely integrates innovation governance with regional development, providing innovative policy tools to address the challenges of insufficient grassroots regional innovation, industrial path dependence, and environmental externalities [

13]. Through institutional incentives and capacity building, the NIPSC is expected to enhance the supply capacity of green technologies at the county level, thereby reinforcing the influence of institutional governance in steering ecological performance [

14]. Currently, few studies have examined the impact of NIPSC on direct air pollution governance at the county level. Can this policy improve air quality? What are the mechanisms involved? Is there regional variation in the effectiveness of direct air pollution control? Addressing these questions is crucial for enhancing the county-level intellectual property governance model and achieving green, sustainable development at the county level.

The literature most relevant to this paper can be categorized into two key areas: one focuses on the role of the intellectual property system in economic growth and innovation, and the other on the relationship between intellectual property and environmental governance. First, scholars generally hold two perspectives regarding the role of the intellectual property system in the economy and innovation. Existing literature generally supports the positive effects of the intellectual property system on economic growth and innovation output [

15,

16]. However, some scholars argue that reducing intellectual property protection may be more beneficial to innovation and economic growth [

17]. After analyzing the relevant literature, Neves [

18] concluded that intellectual property has an overall positive impact on innovation and economic growth, with stronger effects in developed countries than in developing countries. Using panel data from listed companies, Song [

19] found an inverted U-shaped relationship between intellectual property protection and corporate innovation performance in the Chinese market. Second, some empirical studies have increasingly examined the environmental externalities of the intellectual property system. Lv [

20] investigated the impact of intellectual property protection on air pollution using panel data from Chinese cities and found that the National Intellectual Property Demonstration City policy significantly reduced urban PM2.5 concentrations, effectively improving air quality. Nie [

21] conducted empirical analysis based on the NIPSC policy and found that intellectual property protection improved carbon emission efficiency in pilot regions. Mao [

22] examined the role of intellectual property in regional carbon reduction using provincial-level data from China and found that intellectual property protection policies are an important tool for reducing carbon emissions, with regional differences in their impact on carbon reduction.

While the relationship between intellectual property systems and environmental governance has been preliminarily explored, there are still important gaps in the current research: First, existing studies mostly focus on the urban level, while the county-level, as an important component of China’s governance system, has been largely overlooked in the evaluation of intellectual property protection policies. Counties, with limited governance resources, diverse industrial structures, and significant disparities in innovation capabilities, are ideal units for observing the “tail-end effects” of policies. Second, in terms of pollutant selection, current research tends to focus on macro-level emissions or indirect indicators, lacking dynamic tracking of direct pollutants such as SO2 and NH3, and policy identification, thus weakening the explanatory power of actual environmental improvement pathways. Third, in terms of mechanism identification, current research generally views technological innovation as an important transmission path, neglecting the potential for intellectual property protection to improve air quality through indirect mechanisms such as adjusting industrial structures and promoting economic agglomeration. Fourth, there is insufficient analysis of the heterogeneity of policy effects across different regional characteristics. Existing studies have yet to systematically examine how factors such as industrial base, degree of openness, and urban hierarchy shape the differential impacts of policy implementation.

Therefore, this paper focuses on the NIPSC, which was initiated and implemented by the former State Intellectual Property Office in 2009. It systematically evaluates the policy effects of the NIPSC on improving air quality at the county level, exploring its mechanisms and regional heterogeneity. The main contributions of this paper are as follows: First, it expands the spatial scope of environmental studies on intellectual property systems from urban areas to county-level regions, thereby filling the gap in research on the impact of grassroots institutional innovation on environmental performance. Second, current research tends to focus on macro-emission or indirect indicators when selecting pollutants, while the lack of dynamic tracking and policy identification of direct pollutant concentrations, such as SO2 and NH3, limits the ability to effectively explain the actual environmental improvement pathways. Third, regarding mechanism identification, current studies generally view technological innovation as a key transmission pathway, often overlooking the potential for intellectual property protection to improve air quality through indirect mechanisms, such as adjusting industrial structure and promoting economic agglomeration. Fourth, by identifying policy heterogeneity, this paper explores the differential impact of the NIPSC policy on county-level air quality and proposes corresponding policy recommendations.

2. Policy Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Policy Background

The evolution of the global intellectual property system can be traced back to the informal protection of crafts and technologies in ancient civilizations and was continued in the regulations of medieval European craft guilds. In modern times, the 19th century saw countries such as the United Kingdom and France taking the lead in enacting patent and trademark laws, laying the foundation for the modern intellectual property legal system. In the 20th century, with the signing of international agreements such as the Paris Convention (1883) and the Berne Convention (1886), as well as the establishment of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in 1967, global intellectual property protection was significantly strengthened. Entering the 21st century, the digital age has introduced new challenges and opportunities, and the field of intellectual property protection has expanded to include new directions such as digital rights management and open innovation.

China’s evolution of intellectual property protection has similarly evolved from its inception to systematization. In ancient times, the protection of crafts and technologies relied primarily on informal means such as apprenticeship. During the late Qing Dynasty and the Republican period, modern intellectual property ideas were introduced, and initial laws on trademarks and patents were enacted, laying the foundation for the establishment of the modern intellectual property system. Since the reform and opening-up, especially in the 1980s, China has successively enacted laws such as the Patent Law, Trademark Law, and Copyright Law, gradually developing a more comprehensive intellectual property legal system, and continuously strengthening protection through multiple revisions. After joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), China further enhanced its intellectual property protection to align with international standards, and in 2008, issued the National Intellectual Property Strategy Outline, focused on enhancing the intellectual property system, promoting the creation and utilization of intellectual property, strengthening protection, and cultivating an intellectual property culture, thereby constructing a comprehensive intellectual property system. At the same time, China established specialized institutions such as intellectual property courts and internet courts to enhance judicial protection efficiency and specialization. The implementation of the National Intellectual Property Strategy Outline marked the beginning of a new phase in China’s intellectual property development, driven by government initiatives, as China gradually transitioned from adhering to international frameworks to autonomously improving its domestic intellectual property governance. Overall, since the reform and opening-up, especially after joining the WTO, China has made significant progress in intellectual property protection through legal and institutional improvements, establishing a strong foundation for innovation-driven development.

It is worth noting that in the past, China’s intellectual property policies have traditionally followed a “top-down” model, where policies were formulated and implemented by the central government or relevant authorities. This top-down approach helped to swiftly coordinate actions, centralize resource allocation, and ensure consistency and coordination of policies nationwide. However, its drawback was that it did not fully consider the specific circumstances at the local level, which may result in inconsistencies in implementation at the grassroots level and, to some extent, restrict the space for local autonomous innovation. In response to this, the Chinese government started adopting “bottom-up” policy practices, promoting policy innovation through grassroots pilot programs. A key manifestation of this shift in the field of intellectual property is the NIPSC, which conducts pilot projects at the county level. This bottom-up policy model effectively mobilizes local enthusiasm, ensuring that policy measures are better aligned with the actual needs at the grassroots level, and improving the targeting and effectiveness of policy implementation.

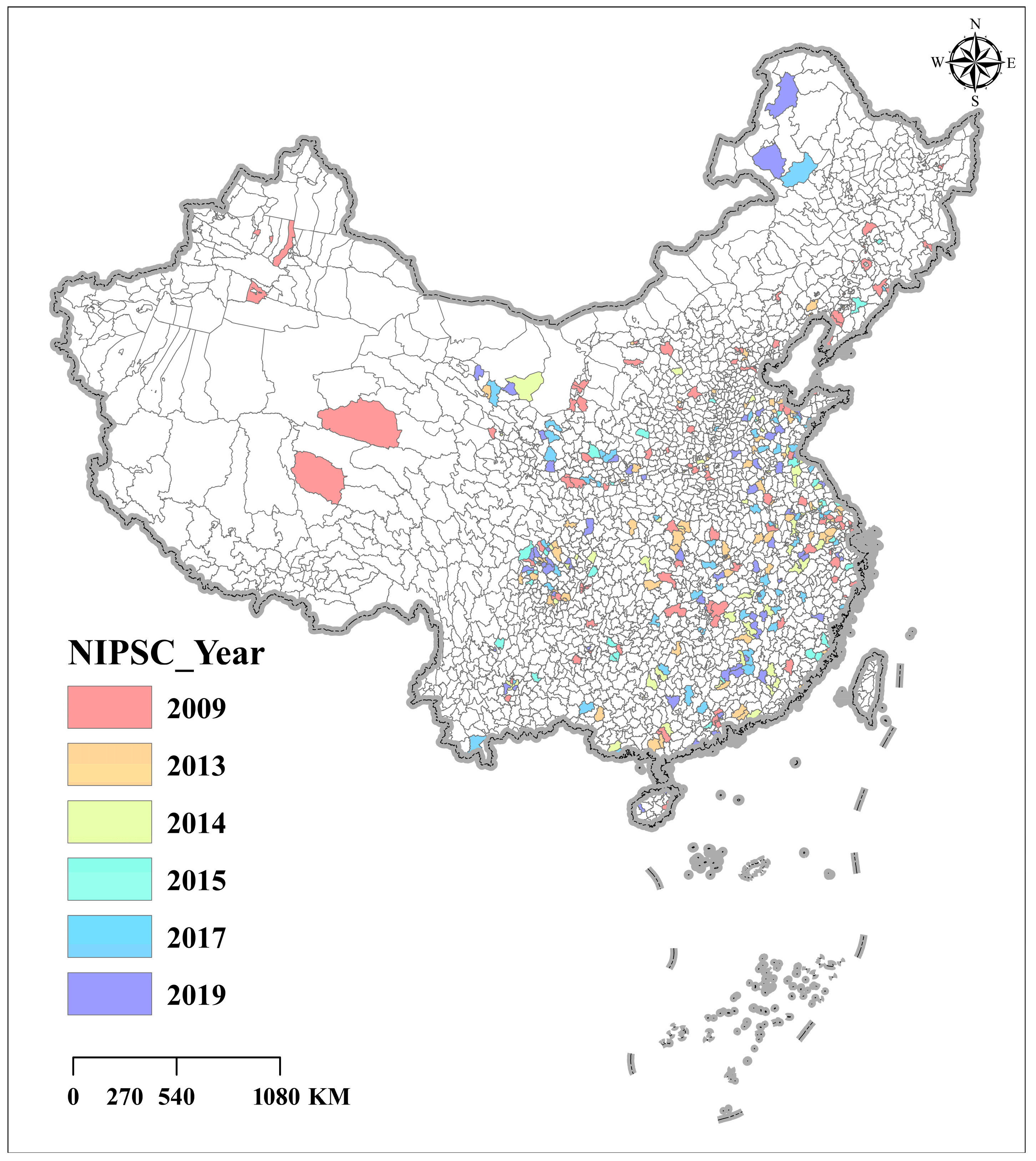

To effectively implement the National Intellectual Property Strategy and fully leverage the role of intellectual property in county-level economic development, the former State Intellectual Property Office launched the NIPSC in 2009. The Program adopts the operational principles of “voluntary application, selective recommendation, centralized evaluation, and tracking management”. County-level governments voluntarily apply, provincial intellectual property management departments selectively recommend, and the national level evaluates and determines the list of pilot or demonstration counties. The first batch of pilot counties selected as part of the first batch in 2009 included 40 counties (cities, districts) from across the country. The Program adopts a “pilot + demonstration” implementation model, granting selected counties greater institutional autonomy while encouraging continuous improvement of their intellectual property systems and management frameworks through strict construction acceptance and evaluation mechanisms. As a new practice in China’s county-level intellectual property governance reform, the key elements of the NIPSC are as follows: (1) Strengthening the construction of county-level intellectual property systems: Developing and enhancing county-level intellectual property management systems, implementing the national intellectual property strategy, and enhancing comprehensive innovation capacity. (2) Promoting industry intellectual property alliances: Guiding key industries in counties to establish intellectual property alliances, with a focus on strengthening intellectual property protection and promoting the role of both traditional and emerging intellectual property in local economic development. (3) Improving the industrialization of patented technologies: Encouraging and facilitating patent applications and authorizations and promoting the transformation and application of patented technologies to drive innovation and technological progress at the county level. Since 2009, the State Intellectual Property Office has conducted evaluations for seven batches of pilot counties under the NIPSC. By the end of 2019, 425 counties (cities, districts) across the country had been included in the list of pilot counties under the program. With the gradual nationwide implementation of this policy, the capacity for intellectual property protection and innovation at the local level has been significantly enhanced. This paper uses the mapping software ArcMap 10.8 to create

Figure 1, visually illustrating the distribution of the pilot counties.

The NIPSC encourages local governments to improve their technological innovation and industrialization support systems, facilitating the adoption of patented technologies in local key industries. This, in turn, promotes the technological transformation and upgrading of high energy-consuming and heavily polluting sectors, while also stimulating the introduction of green and low-carbon innovation projects. In the pilot counties, as intellectual property protection and commercialization mechanisms are strengthened, enterprises are more likely to adopt efficient desulfurization and ammonia removal processes and clean production technologies, thus reducing SO2 and NH3 emissions. Additionally, the demonstration effect of the Program and its performance evaluation mechanism drive local fiscal and social capital toward environmental innovation, further improving the precision of air quality management. As a result, the NIPSC effectively improves SO2 and NH3 concentrations at the county level through a synergy of technological diffusion and institutional incentives.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. Direct Effect

Within the framework of institutional economics, environmental pollution control is not solely dependent on coercive interventions; instead, it can be influenced through institutional adjustments that affect the behavior of local governments and market expectations, thereby achieving “indirect pollution control” [

23,

24]. As an embedded institutional reform practice, the NIPSC is not primarily aimed at environmental protection. However, it may indirectly improve regional air quality through pathways such as optimizing governance structures, reshaping institutional incentives, and enhancing innovation capabilities. First, NIPSC promotes the establishment of intellectual property management systems at the county level and improves patent application and commercialization systems, which helps build an innovation-oriented institutional environment and increases the marginal returns from green technology research and diffusion [

25]. Within a framework where property rights are clear and protection is in place, green innovators are more likely to expect long-term returns on investment, thus encouraging investment in environmentally friendly technologies [

16,

26,

27]. This institutional incentive not only boosts the enthusiasm for green technology development but also improves the efficiency of its cross-regional diffusion, laying the technological foundation for cross-county pollution control. Second, the improvement of the property rights system enhances enterprises’ control over their technological assets, which in turn encourages them to adopt cleaner process routes and invest in cleaner equipment [

13]. Lastly, at the local governance level, NIPSC provides pilot county governments with greater authority in intellectual property policy formulation and resource allocation. This “decentralization of autonomy” not only encourages local governments to implement targeted innovation incentives but also facilitates their ability to incorporate green development indicators into their performance evaluation logic [

28]. In counties with limited fiscal autonomy and weak pollution control capacity, the institutional support provided by NIPSC may help overcome the limitations of traditional environmental regulation and promote the coordinated progress of environmental governance and economic development. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The NIPSC can improve county-level air quality.

2.2.2. Indirect Effects

Technological innovation, particularly green technology innovation, is a crucial factor influencing air quality [

29,

30,

31]. Previous studies have shown that technological advancements can significantly contribute to achieving emission reduction targets by improving resource efficiency and reducing pollutant emissions [

32,

33]. The impact of the NIPSC on corporate innovation and air pollution control is primarily reflected in the following aspects: First, by strengthening intellectual property protection, enterprises receive stronger incentives for innovation, reducing the risk of unfair external competition, and thus lowering the risks involved in the innovation process [

34]. After obtaining intellectual property protection, enterprises are more likely to invest resources in the research and development of new products and processes, thereby reducing pollutant emissions in traditional production processes. For example, the promotion of clean energy technologies, wastewater and exhaust gas treatment technologies, and green manufacturing processes can significantly reduce pollutant emissions at the source [

35,

36]. Second, the implementation of the NIPSC contributes to improving the conversion rate of innovation outcomes at the county level and accelerates the adoption of green technologies. In this process, local governments, by strengthening intellectual property protection, facilitate the implementation of green technology innovations and environmental policies, thus enhancing the environmental protection capacity of counties. In light of the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The NIPSC can improve county-level air quality by strengthening technological innovation at the county level.

Industrial structure upgrading is a crucial path for the sustainable development of regional economies and environmental quality improvement [

37,

38,

39]. As an important policy tool for promoting county-level economic innovation and technological progress, the NIPSC can support the improvement of county-level air quality by driving the optimization of county-level industrial structures. Specifically, intellectual property protection incentivizes the development of high-tech and green industries, reducing the county’s dependence on resource-heavy and polluting industries, and providing the necessary support for the green transformation of industries [

40,

41]. First, with the support of this policy, county-level enterprises are more willing to invest in the research and development of green technologies, clean energy, and low-pollution processes, thus fostering the upgrading or elimination of traditional pollution-intensive industries. Meanwhile, advancements in environmental technologies enable various industries to gradually adopt low-carbon, green production methods, leading to a reduction in pollutant emissions at the source. Second, through policy incentives, the NIPSC facilitates the transition of county-level traditional industries with low added value and high pollution to high added value and low pollution industries. With the optimization of the industrial structure, county governments and enterprises are better able to adapt to market demand and encourage the efficient allocation of resources. This industrial transformation not only promotes the growth of high-tech industries but also brings more employment and technological development opportunities to the county, while enhancing the environmental protection capacity of the county’s governance system. As green industries and environmental protection technologies continue to grow, county governments can more effectively implement environmental protection policies and advance pollution control efforts in a more systematic and integrated manner, further reducing pollutant emissions. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: The NIPSC can improve county-level air quality by promoting industrial structure upgrading.

Economic agglomeration is a crucial driver of local economic growth, particularly in the areas of innovation and technology application [

42,

43]. The NIPSC facilitates the clustering of local innovative enterprises and research institutions by improving the intellectual property protection system, encouraging innovation investment, and enhancing technology commercialization. With the increase in innovative enterprises, the economic structure of the county is optimized, and the efficiency of capital, technology, and talent flow is improved. This process supports the sustainable growth of the local economy and the improvement of environmental quality [

44,

45]. First, the NIPSC draws numerous innovative enterprises and research institutions into counties by optimizing intellectual property protection and innovation policies. As these enterprises cluster, technology resources at the county level are more effectively shared and utilized. This optimized resource allocation not only enhances production efficiency but also promotes the adoption and application of green production methods. Second, economic agglomeration facilitates economies of scale and fosters collaborative innovation [

46,

47]. In an agglomerated economic environment, local enterprises can more effectively share innovation outcomes, reduce R&D costs, and improve the efficiency of technology commercialization and application. This agglomeration effect not only accelerates the spread of green technologies but also stimulates the innovation of the environmental protection industry, thereby promoting the application of pollution control technologies. Finally, economic agglomeration enhances the enforcement capacity of county governments in pollution control. With the concentration of technology and resources, county governments can better integrate and optimize environmental protection facilities, implement environmental policies, and enhance governance efficiency through integrated regulatory mechanisms. Therefore, the NIPSC, by fostering economic agglomeration, can improve the efficiency of resource allocation and the application of environmental protection technologies within counties, thereby indirectly improving air quality. Based on the above analysis, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: The NIPSC can improve county-level air quality by enhancing economic agglomeration.

As illustrated, this paper outlines the theoretical analysis and research framework, as shown in

Figure 2.

6. Discussion

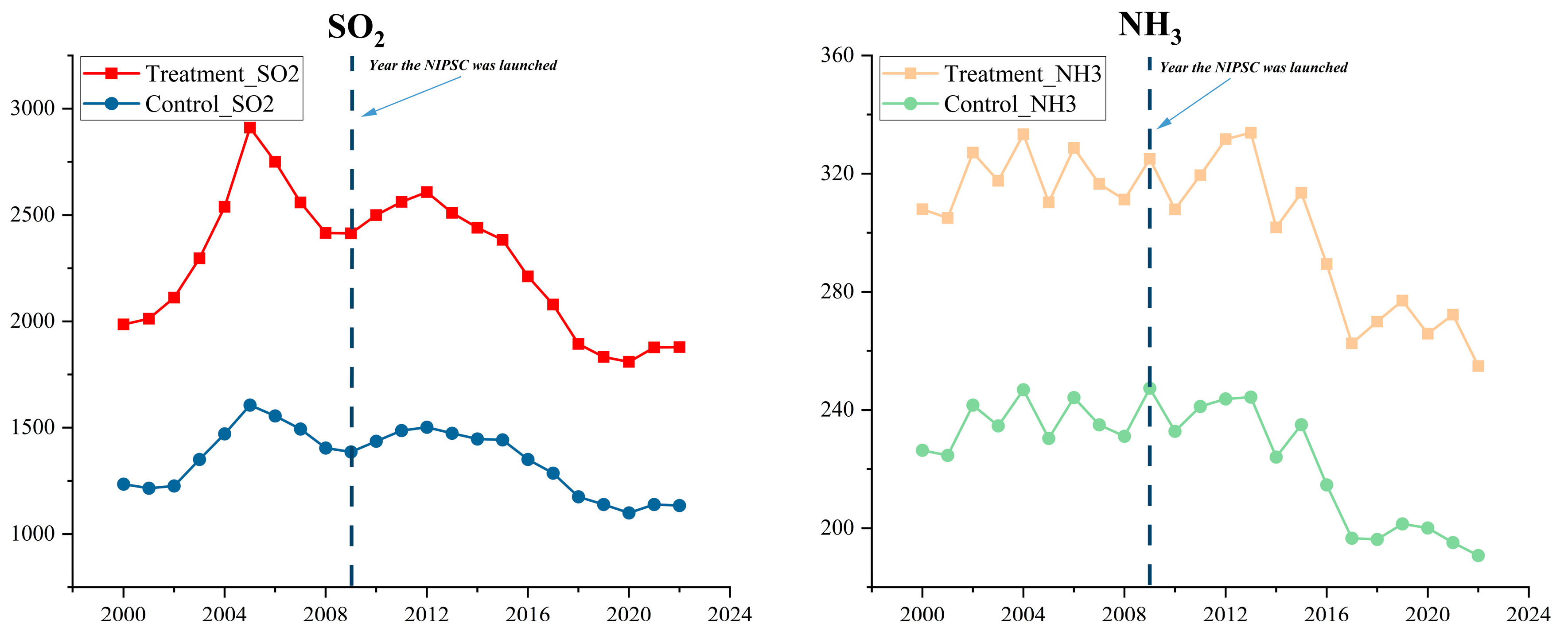

This paper empirically examines the positive impact of the NIPSC policy on reducing county-level SO

2 and NH

3 emissions by employing Chinese county-level data and a multi-period difference-in-differences model. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that the NIPSC policy enhances county-level air quality by influencing key mechanisms such as technological innovation, industrial restructuring, and economic clustering, and that its effects exhibit significant heterogeneity across counties with different industrial foundations and administrative hierarchies. Compared with the existing literature, the main theoretical contributions of this study can be summarized in three main dimensions: First, this study broadens the research scale. While most existing studies focus on cities or firms, this study extends the analysis to the county level, thereby broadening the spatial scope of research on the environmental impacts of intellectual property protection policies. Second, this study diversifies the selection of pollutants. By focusing on SO

2 and NH

3, it highlights the dual industrial–agricultural nature of county-level air pollution and provides deeper insight into the mechanisms through which the policy affects direct emissions. Third, this study deepens the identification of underlying mechanisms. Beyond the widely recognized technological innovation pathway, it substantiates the roles of industrial restructuring and economic clustering, thereby enriching the existing theoretical framework. In relation to prior research, the findings of this study align with city- and firm-level evidence, confirming the positive impact of the NIPSC policy on air quality [

20,

65]. While maintaining the consistency of the conclusions, this paper makes theoretical advancements in research scale, mechanism identification, and pollutant selection, thereby not only supplementing the existing literature but also advancing theoretical development.

Nonetheless, there are several limitations to this study. Firstly, while the policy effects were validated using the NIPSC policy and a multi-period DID model, the analysis did not sufficiently account for cross-regional effects across different areas. Specifically, in high-pollution regions, the impact of the policy may vary due to differences in resources, funding, and technological capabilities, leading to regional heterogeneity in policy effectiveness. As a result, future research could explore the spatial spillover effects of the policy, particularly the interactions between neighboring counties and cities. Secondly, this study did not distinguish the specific effects of different types of intellectual property protection measures on environmental quality. The empirical analysis treated intellectual property protection as a unified category; however, various types of patents—such as invention patents, utility model patents, and design patents—differ in their contributions to emission reduction. For example, invention patents related to green technologies may directly contribute to pollutant reduction, while patents related to energy-intensive industries may not necessarily result in environmental improvements. Additionally, the quality of patents (e.g., highly-cited versus low-quality patents) and their field-specific applications may also influence their environmental impact. Future studies could further refine the analysis by examining more detailed patent data, considering factors such as patent type, technological domain, and quality, in order to provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between intellectual property protection and air pollution control.

7. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This paper evaluates the impact of the National Intellectual Property Strong County Program on county-level air quality using a multi-period difference-in-differences model to rigorously assess the policy’s effectiveness. The results show that the NIPSC significantly improves air quality in pilot counties, most notably by lowering sulfur dioxide and ammonia concentrations. Specifically, after the policy’s implementation, SO2 levels in pilot counties fell by 2.850 units and NH3 levels dropped by 0.104 units. The result remains statistically significant after a series of robustness checks. Further mechanism analysis indicates that the NIPSC operates primarily through three channels. First, technological innovation promotes the adoption of green technologies and low-carbon production processes, thereby reducing emissions from pollution sources. Second, industrial upgrading fosters the growth of high value-added, low-pollution industries, reduces the share of traditional high-pollution sectors, and optimizes the overall economic structure. Third, economic agglomeration plays a crucial role, as the NIPSC enhances the concentration of innovation resources, improves local governance capacity, and further contributes to air quality improvement. In addition, the heterogeneity analysis indicates that policy effects vary across different locational contexts, with significantly stronger impacts observed in counties that are not part of traditional industrial bases, possess international airports, or hold higher administrative status.

Based on the above findings, this study offers the following policy recommendations. First, intellectual property protection at the county level should be further strengthened, particularly in supporting innovative enterprises and green technologies. This will help reduce legal risks during the innovation process and encourage more firms to increase R&D investment. Such measures not only foster technological innovation but also provide stronger legal safeguards for the growth of green industries. Second, efforts should be accelerated to optimize and upgrade the industrial structure, with a focus on promoting low-carbon and environmentally friendly industries, while encouraging traditional high-pollution sectors to transition toward greener production methods. By fostering the rise in high value-added, low-pollution industries, counties can effectively improve air quality and lay a solid foundation for sustainable economic development. Finally, local governments should adopt differentiated policies tailored to local conditions. In particular, resource-based cities and traditional industrial bases should be provided with greater technical support and assistance for industrial transformation.

In summary, this study provides new empirical evidence on the relationship between intellectual property protection policies and air pollution control, expands the analytical perspective on county-level ecological and environmental governance, and offers both theoretical and empirical support for the formulation and implementation of related policies.