Pre-Consumption Food Choice Priorities, Food Waste Concerns, and Incentive Strategies for Change—A Portuguese Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

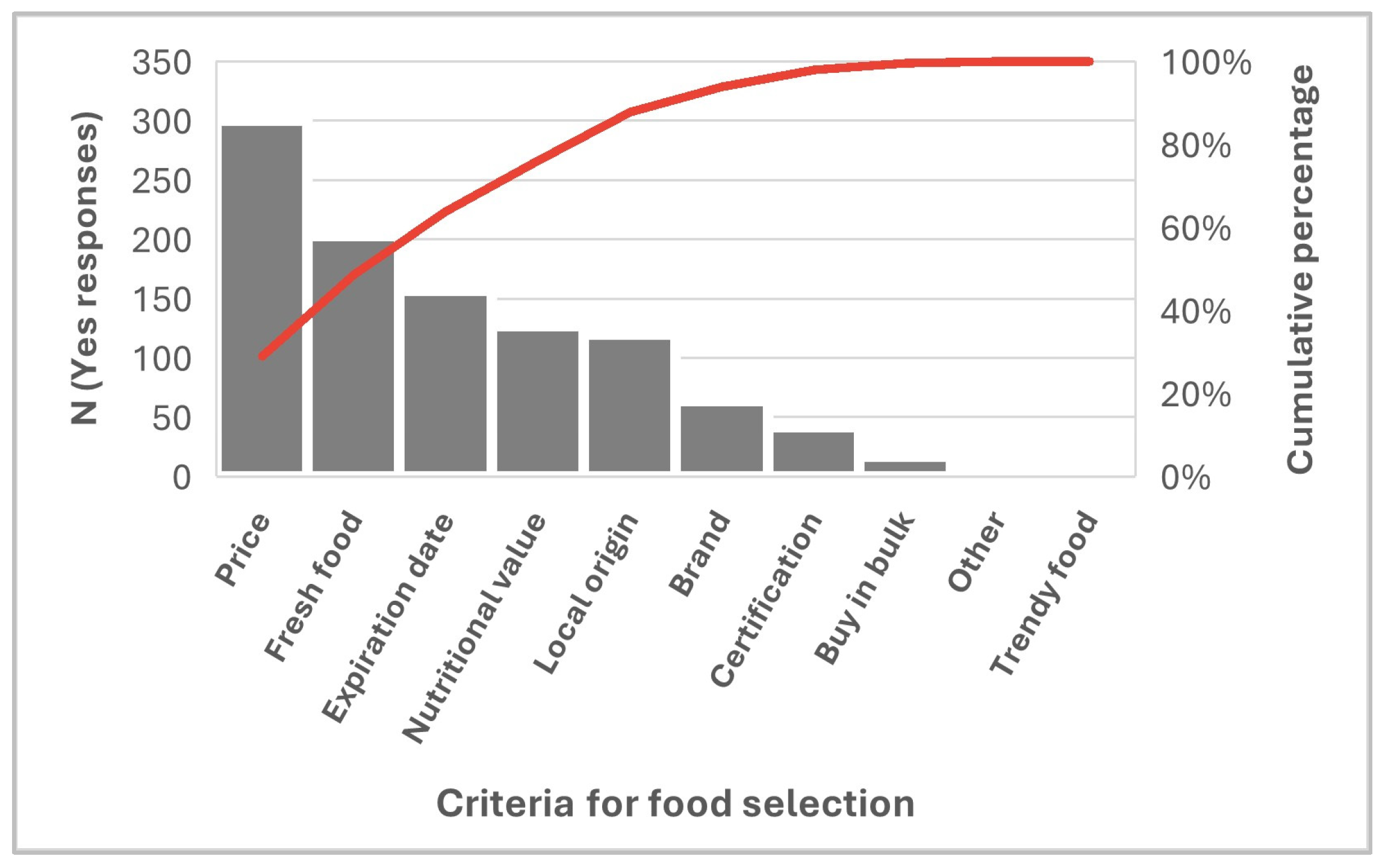

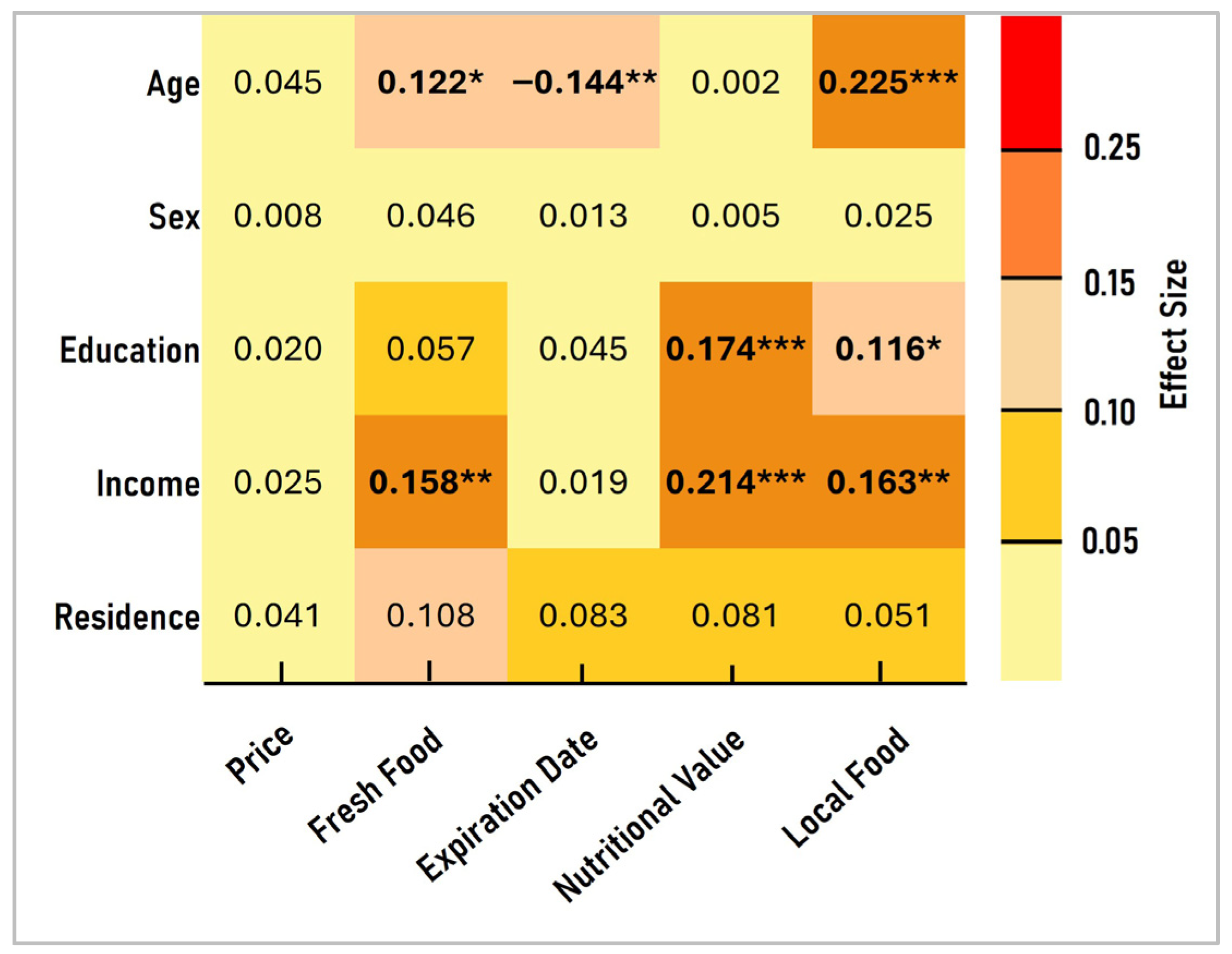

3.2. Pre-Consumption Criteria for Food Choices

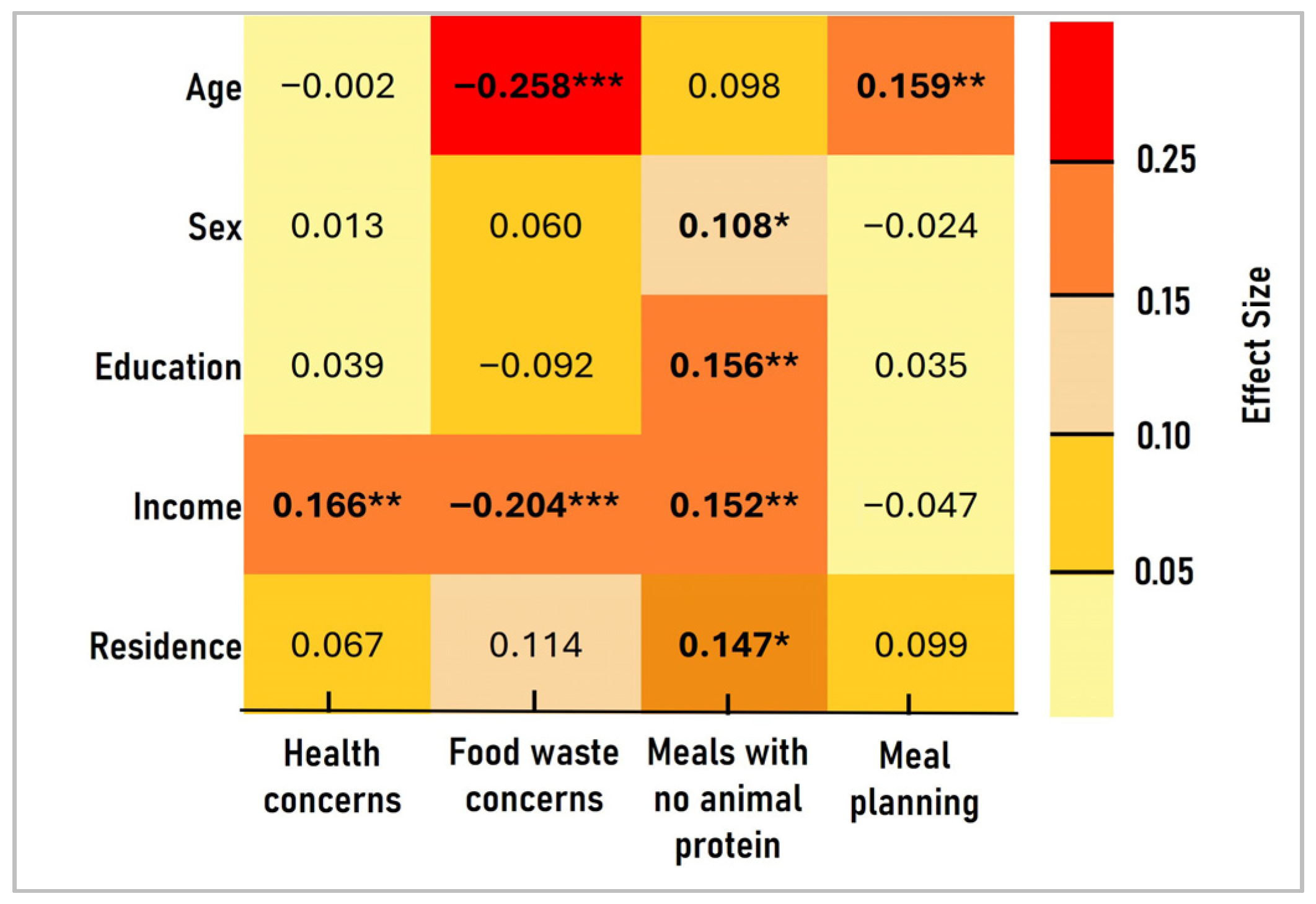

3.3. Concerns About Food Consumption

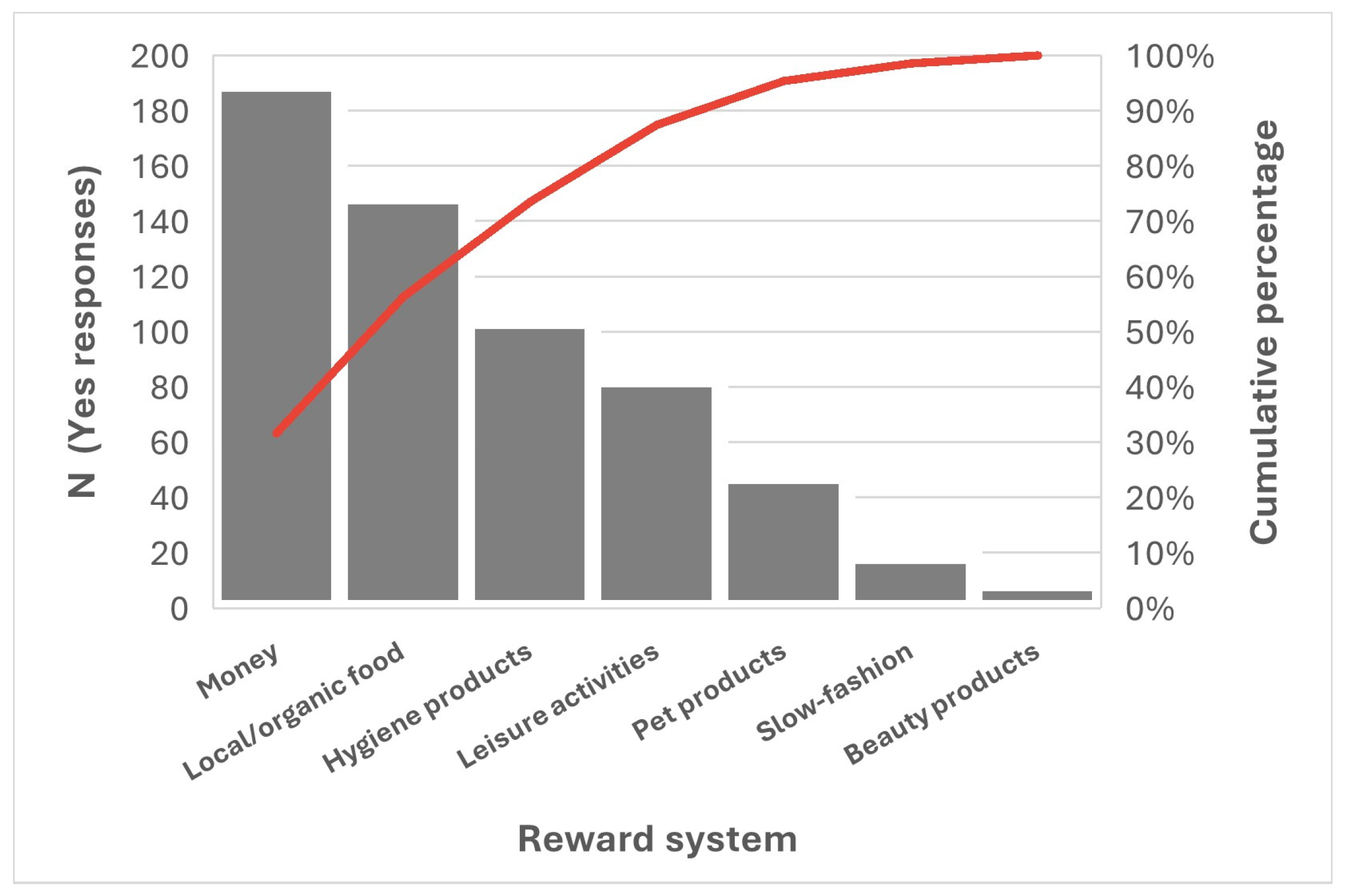

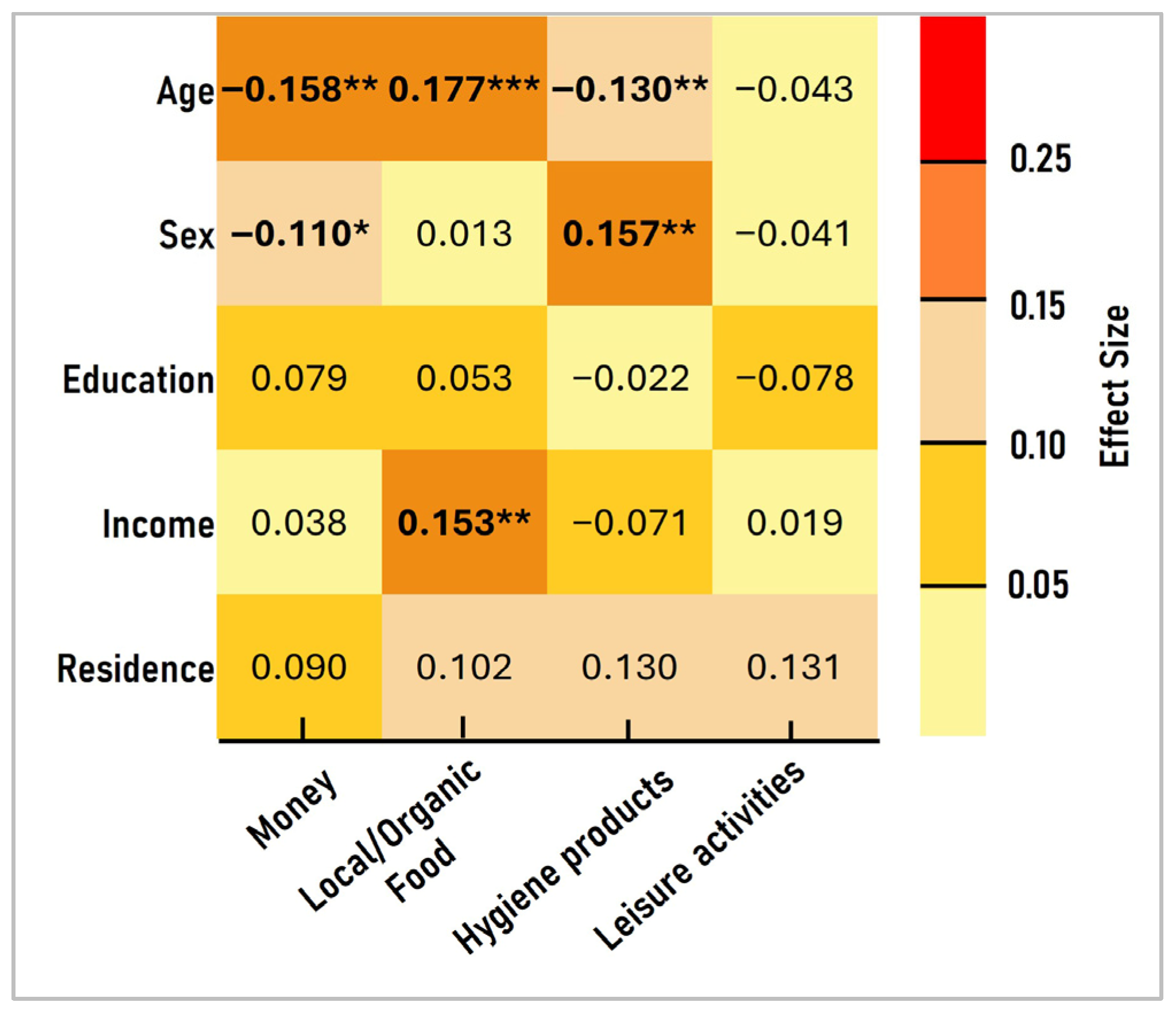

3.4. Reward Systems

3.5. Associations Between Reward Systems and Criteria for Food Choices

4. Discussion

4.1. Determinants of Criteria for Pre-Consumption Food Choices and Sustainable Behaviors

4.2. Influence of Reward Systems to Promote Sustainable Behaviors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ruggerio, C.A. Sustainability and sustainable development: A review of principles and definitions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/publications/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development-17981 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Jennings, R.; Henderson, A.D.; Phelps, A.; Janda, K.M.; van den Berg, A.E. Five U.S. Dietary Patterns and Their Relationship to Land Use, Water Use, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Implications for Future Food Security. Nutrients 2023, 15, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Rosado, P.; Roser, M. Environmental Impacts of Food Production. Our World Data. 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impacts-of-food (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Food Waste Index Report 2024. Think Eat Save: Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste; United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): Nairobi, Kenya, 2024; Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/45230 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). Food Waste Per Inhabitant (kg/inhab.) and Food Waste by Food Supply Chain Annual 2022. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_indicadores&indOcorrCod=0011469&xlang=en&contexto=bd&selTab=tab2 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Godinho, M.; Gonella, J.S.L.; Latan, H.; Ganga, G.M.D. Awareness as a Catalyst for Sustainable Behaviors: A Theoretical Exploration of Planned Behavior and Value-Belief-Norms in the Circular Economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 368, 122181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidoglio, G.A.; Schwarzmueller, F.; Kastner, T. A Global Multi-Indicator Assessment of the Environmental Impact of Livestock Products. Glob. Environ. Change 2024, 87, 102853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe-Inge, V.; Aidoo, R.; Moncada de la Fuente, M.; Kwofie, E.M. Plant-Based Dietary Shift: Current Trends, Barriers, and Carriers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresán, U.; Sabaté, J. Vegetarian Diets: Planetary Health and Its Alignment with Human Health. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10 (Suppl. 4), S380–S388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raftowicz, M.; Solarz, K.; Dradrach, A. Short Food Supply Chains as a Practical Implication of Sustainable Development Ideas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Singh, S.; Tyagi, M.; Powar, S. Avenues of Decarbonisation in the Dynamics of Processed Food Supply Chains: Towards Responsible Production Consumption. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoglu, H. User’s Guide to Correlation Coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2018, 18, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.-J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kurisu, K.; Fukushi, K. What Should Be Understood to Promote Environmentally Sustainable Diets? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 51, 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallnoefer, L.M.; Riefler, P.; Meixner, O. What Drives the Choice of Local Seasonal Food? Analysis of the Importance of Different Key Motives. Foods 2021, 10, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicka, E.; Kaczorowska, J.; Rejman, K.; Plichta, M. Investigating the Consumer Choices of Gen Z: A Sustainable Food System Perspective. Nutrients 2025, 17, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Lenthe, F.J.; Jansen, T.; Kamphuis, C.B.M. Understanding Socio-Economic Inequalities in Food Choice Behaviour: Can Maslow’s Pyramid Help? Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 113, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J. Household Meal Planning as Anticipatory Practice: The Role of Anticipation in Managing Domestic Food Consumption and Waste. Geoforum 2023, 144, 103791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K.T.; Ajai, O.; Duke, O.; Jijingi, H.E. Systematic review of factors influencing household food waste behaviour: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43, 803–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfredi, V.; Stacchini, L.; Lotti, S.; Sarno, I.; Sofi, F.; Dinu, M. Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviours towards Food Sustainability in a Group of Italian Consumers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 75, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, A.; Ma, Y.; Reza, M.N.H.; Ahmad, J.; Wan Mohd Hirwani Wan, H.; Zhai, L. Predicting attitude and intention to reduce food waste using the environmental values-beliefs-norms model and the theory of planned behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 120, 105247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bravo, P.; Chambers, E.; Noguera-Artiaga, L.; López-Lluch, D.; Chambers, E.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Sendra, E. Consumers’ attitude towards the sustainability of different food categories. Foods 2020, 9, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilone, V.; di Santo, N.; Sisto, R. Factors Affecting Food Waste: A Bibliometric Review on the Household Behaviors. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Hetherington, J.B.; O’Connor, P.J.; Malek, L. Sustainable Food Consumption: Sustainability-Conscious Consumers Do Not Reduce Food Waste but Nutrition-Conscious Consumers Do. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 219, 108296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, M.; Janssen, M. Self-Determined or Non-Self-Determined? Exploring Consumer Motivation for Sustainable Food Choices. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 45, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (responses = 366) | |

| 18–34 years | 184 (50.3%) |

| ≥35 years | 182 (49.7%) |

| Sex (responses = 366) | |

| Female | 238 (65%) |

| Male | 128 (35%) |

| Education level (responses = 348) | |

| High School | 156 (44.8%) |

| University | 192 (55.2%) |

| Residence (responses = 363) | |

| Large City/Metropolitan Area | 184 (50.7%) |

| Medium-Sized or Small City | 101 (27.8%) |

| Village or Rural area | 78 (21.5%) |

| Household Income per month (responses = 311) | |

| <1500 EUR | 139 (44.7) |

| ≥1500 EUR | 172 (55.3%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pinto, P.; Figueiredo, M.; Ferrão, I.; Narciso, R.; Ruivo, P. Pre-Consumption Food Choice Priorities, Food Waste Concerns, and Incentive Strategies for Change—A Portuguese Case Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209176

Pinto P, Figueiredo M, Ferrão I, Narciso R, Ruivo P. Pre-Consumption Food Choice Priorities, Food Waste Concerns, and Incentive Strategies for Change—A Portuguese Case Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209176

Chicago/Turabian StylePinto, Paula, Maria Figueiredo, Inês Ferrão, Renata Narciso, and Paula Ruivo. 2025. "Pre-Consumption Food Choice Priorities, Food Waste Concerns, and Incentive Strategies for Change—A Portuguese Case Study" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209176

APA StylePinto, P., Figueiredo, M., Ferrão, I., Narciso, R., & Ruivo, P. (2025). Pre-Consumption Food Choice Priorities, Food Waste Concerns, and Incentive Strategies for Change—A Portuguese Case Study. Sustainability, 17(20), 9176. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209176