Re-Configuring Social Work, Indigenous Strategies and Sustainability in Remote Communities: Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Eco-Social Work and Intersectional Perspectives

1.2. Towards an Indigenous Eco-Social Work Practice Approach

1.3. Framing Eco-Social Work Through Indigenous Approaches

2. Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm?

3. Challenges of Implementation and Sustainability

4. Conclusions and the Way Forward

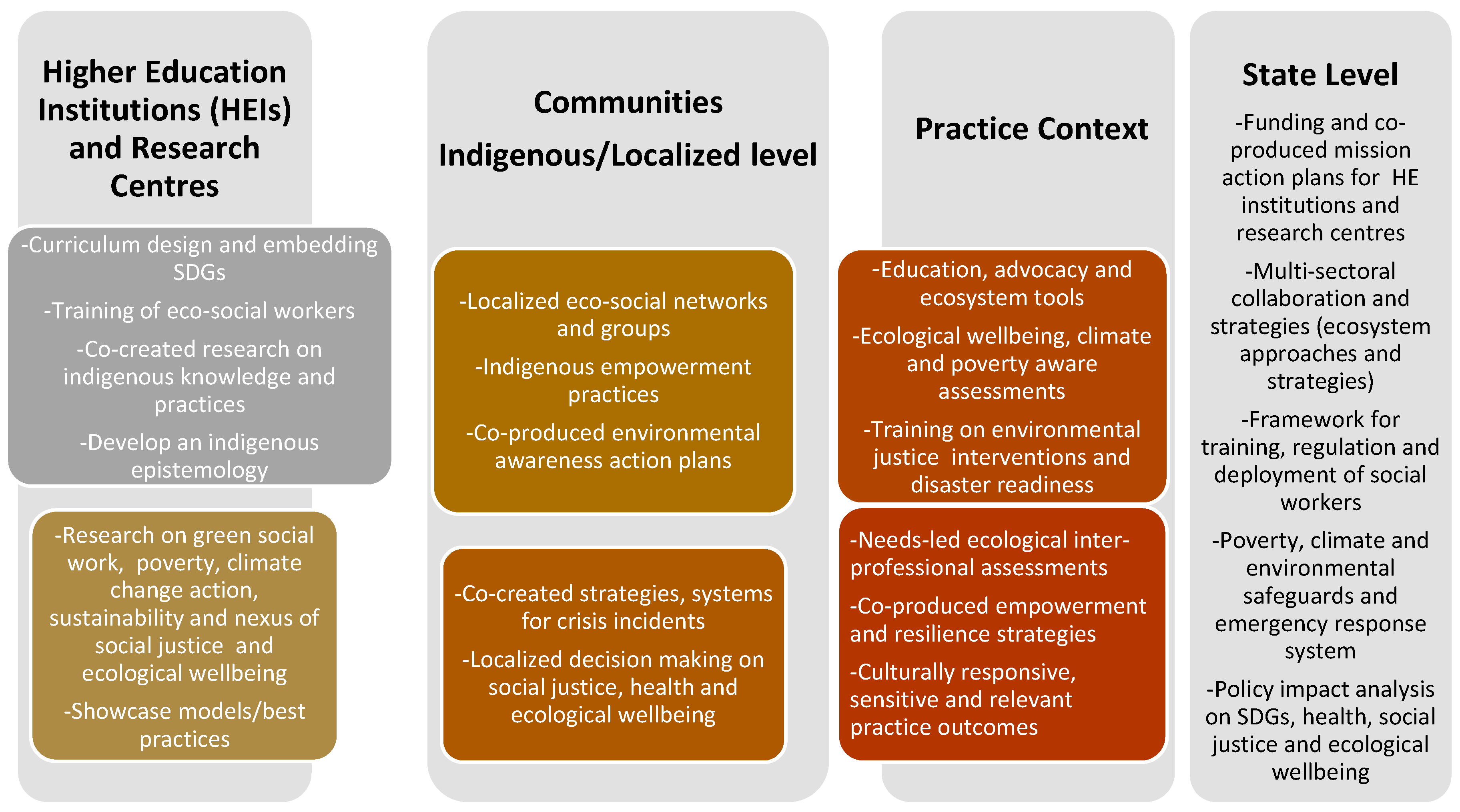

- The proposed intersectional paradigm offers a ‘scaffolded approach’ to embedding eco-social work. One of its major responsibilities is the creation of social work programmes and ability to offer greater credence for their professionalisation. Social workers and other practitioners play a critical role in unpacking the interconnections between social and ecological perspectives, with ramifications for the health and wellbeing of communities. As highlighted throughout, the effects of poverty, exacerbated by climate change and environmental degradation, are increasingly evident. An eco-social work curriculum and revamped practice contexts have implications for the livelihoods of the most vulnerable, marginalised, and impoverished communities.

- Even in regions with well-established social work programmes, social workers are increasingly challenged by the lack of continuing professional development opportunities and regulatory oversight. The state, being a major pillar, has a paramount responsibility to ensure the wellbeing of service users through the provision of relevant infrastructure. This concern is particularly acute, aggravated by the lack of an indigenously driven and engaging curricula on environmental education. As highlighted in the proposed intersectional paradigm, there is a pressing need for collaborative relationships among the state, higher education institutions, communities, social workers, allied health professionals and development practitioners in re-designing the curriculum and in the evolving practice contexts.

- This paper advocates for reconfiguration, grounded in an explicit eco-social work paradigm that considers individual wellbeing alongside ecological sustainability. The evidence suggests that climate change and environmental degradation pose an existential threat not only to community cohesion, but also to livelihoods in remote communities. Alongside the state and other practitioners, social workers have the obligatory duty, as advocates, to respond to these crises. To do this effectively, an indigenous epistemology is imperative, as envisioned in the intersectional paradigm.

- This praxis would provide a deeper understanding of indigenous knowledge, and how this can shape sustainability. Social workers are expected to be knowledgeable of the economic, political, and institutional power structures that create disparities and inequalities.

- The practice contexts are a central pillar of this, and an eco-social work paradigm shift offers a clear mandate for rural social work practice to effectively address poverty and climate change. This is essential for developing more just and sustainable futures, especially in remote communities of the global South. This conceptual paper argues that a paradigm shift is necessary to enable communities to be effectively supported in addressing their health and wellbeing challenges.

- Although valuable insights are provided, this paper is not without limitations. Further empirical research evidence and data are required to test the applicability and impact of the main pillars of the paradigm in terms of their regional representativeness and replicability. Additional research is needed for each region in SSA to determine which indigenous epistemology can be deployed based on the contextual realities and underlying principles, value base, and ethics. It would be beneficial to conduct further research on the practice context and the role of eco-social workers to better understand their role within the context of interprofessional collaboration. Globally, there is an urgent need to confront the adverse effects of ecological challenges. This intersectional paradigm offers an opportunity to formulate an ecological wellbeing policy to strengthen community-level resilience and sustainability.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fox, L.; Enari, D. As It Is Above, So It Is Below: Repositioning Indigenous Knowledge Systems within Eco-social Work. Soc. Work 2025, 70, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, H.; Twikirize, J. Social innovations in rural communities in Africa’s Great Lakes region. A social work perspective. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 99, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, S.; Okoye, U. New directions in social work education in Africa: Challenges and prospects. Soc. Work Educ. 2023, 42, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushunje, M.; Matsika, A.B. Environmental Social Work: African philosophies, frameworks and perspectives. Afr. J. Soc. Work 2023, 13, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veta, O.D.; McLaughlin, H. Social work education and practice in Africa: The problems and prospects. Soc. Work Educ. 2023, 42, 1375–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugumbate, J.R.; Mupedziswa, R.; Twikirize, J.M.; Mthethwa, E.; Desta, A.A.; Oyinlola, O. Understanding Ubuntu and its contribution to social work education in Africa and other regions of the world. Soc. Work Educ. 2024, 43, 1123–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.E.; Obeng, J.K. An eco-social work model for social work education in Africa. Afr. J. Soc. Work 2023, 13, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naami, A.; Mfoafo-M’Carthy, M. Exploring African-centred social work education: The Ghanaian experience. Soc. Work Educ. 2023, 42, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; Coates, J. Changing Gears: Shifting to an Environmental Perspective in Social Work Education. Soc. Work. Educ. 2015, 34, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, K.; Yesudian, B.J.Y. Green Social Work: Understanding the Impact of Social Work Education on the Environment. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Res. Rev. 2025, 8, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigangaidze, R.K. The environment has rights: Eco-spiritual social work through ubuntu philosophy and Pachamama: A commentary. Int. Soc. Work 2023, 66, 1059–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkert, L.; Jacobs, I. Ecological Social Work in South Africa and the Way Forward. In Practical and Political Approaches to Recontextualizing Social Work; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boetto, H. Promoting sustainable development in the Australian Murray-Darling basin: Envisioning an Eco Social work approach. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 33, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaree, K. Environmental social work: Implications for accelerating the implementation of sustainable development in social work curricula. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 557–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokane, A.L.; Masoga, M.A. African indigenous knowledge and social work practice: Towards an Afro-sensed perspective. South. Afr. J. Soc. Work Soc. Dev. 2018, 30, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonchingong Che, C.; Bang, H.N. Towards a “Social Justice Ecosystem Framework” for Enhancing Livelihoods and Sustainability in Pastoralist Communities. Societies 2024, 14, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thysell, M.; Cuadra, C.B. Imagining the ecosocial within social work. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2022, 32, 455–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Blewitt, J. Understanding Sustainable Development, 3rd ed.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boetto, H. A transformative eco-social model: Challenging modernist assumptions in social work. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFSW. The Role of Social Workers in Advancing a New Eco-Social World. 2022. Available online: https://www.ifsw.org/the-role-of-social-workers-in-advancing-a-new-eco-social-world/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Nöjd, T.; Kannasoja, S.; Niemi, P.; Ranta-Tyrkkö, S.; Närhi, K. Ecosocial work among social welfare professionals in Finland: Key learnings for future practice. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2024, 33, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, S.; Boddy, J. Environmental social work—A concept analysis. Br. J. Soc. Work 2017, 47, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaree, K.; Powers, M.C.F.; Smith, R.J. Eco social work and social change in community practice. J. Community Pract. 2019, 27, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlborg, H.; Nightingale, A. Theorizing power in political ecology: The “where” of power in resource governance projects. J. Political Ecol. 2018, 25, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; McDade, T. The Biosocial Approach to Human Development, Behaviour, and Health Across the Life Course. RSF 2018, 4, 2–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Garlington, S.B.; Collins, M.E. Addressing environmental justice: Virtue ethics, social work, and social welfare. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2021, 30, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, J.; Alston, M. (Eds.) Ecological social work. In Towards Sustainability; Palgrave: Basingstoke, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Boetto, H.; Närhi, K.; Bowles, W. Creating “communities of practice” to enhance ecosocial work: A comparison between Finland and Australia. Br. J. Soc. Work 2022, 52, 4815–4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besthorn, F.H. Ecological Social Work: Shifting Paradigms in Environmental Practice, 2nd ed.; International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besthorn, F.H.; Canda, E.R. Revisioning environment: Deep ecology for education and training in social work. J. Teach. Soc. Work 2002, 22, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Ecology and Social Work: Toward a New Paradigm; Fernwood Press: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M. Social work, climate change and global co-operation. Int. Soc. Work 2015, 58, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngunjiri, F.W. I am because we are: Exploring women’s leadership under Ubuntu worldview. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2016, 18, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maathai, M.W. Bottlenecks to Development in Africa Speech. P.2, Edited. 1995. Available online: https://africasocialwork.net/wangari-muta-maathai/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- African Union (AU). AU Sustainable Environment and Blue Economy (SEBE) Directorate; African Union: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2022; pp. 2–12. Available online: https://au.int/en/directorates/sustainable-environment (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Mbah, M.; Fonchingong, C. Curating Indigenous Knowledge and Practices for Sustainable Development: Possibilities for a Socio-Ecologically-Minded University. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiller, U. Child sexual abuse allegations: Challenges faced by social workers in child protection organizations. Practice 2017, 29, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veta, O.D. Challenges and Enhancement of Medical Social Workers in Public Health Facilities in Nigeria. Soc. Work Public Health 2022, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidlid, A.; Krøvel, R. (Eds.) Indigenous Knowledges and the Sustainable Development Agenda; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Latulippe, N.; Klenk, N. Making room and moving over: Knowledge co-production, indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, C.F.; Mbah, M. Social Solidarity Economy and Village-centric Development in North-West Cameroon. Int. J. Community Soc. Dev. 2021, 3, 126–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekudu, J. Ubuntu. In Theories for Decolonial Social Work Practice in South Africa; van Breda, A.D., Sekudu, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Metz, T. Ubuntu: The good life. In Encyclopaedia of Quality of Life and Wellbeing Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 6761–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Breda, A.D. A critical review of resilience theory and its relevance for social work. Soc. Work Maatskaplike Werk 2018, 54, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Che, C.F. Re-Configuring Social Work, Indigenous Strategies and Sustainability in Remote Communities: Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm? Sustainability 2025, 17, 9173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209173

Che CF. Re-Configuring Social Work, Indigenous Strategies and Sustainability in Remote Communities: Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm? Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209173

Chicago/Turabian StyleChe, Charles Fonchingong. 2025. "Re-Configuring Social Work, Indigenous Strategies and Sustainability in Remote Communities: Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm?" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209173

APA StyleChe, C. F. (2025). Re-Configuring Social Work, Indigenous Strategies and Sustainability in Remote Communities: Is Eco-Social Work a Workable Paradigm? Sustainability, 17(20), 9173. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209173