1. Introduction

Tourism, as one of the most dynamic industries in recent decades, faces the dual challenge of ensuring visitor safety and maintaining the long-term sustainability of destinations, with the perception of safety recognised as a key factor in tourists’ decision-making [

1,

2,

3]. At the same time, global processes such as climate change, urban growth, and increasing pressure on resources require the adoption of sustainable tourism management models. In this context, digital technologies represent a crucial driver of the transformation of tourist destinations [

4]. Their application enables more efficient management of spatial flows, timely communication with tourists, enhanced institutional transparency, and the development of innovative services that simultaneously improve both security and sustainability [

2,

5]. Smart cities and smart destinations integrate technologies such as artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (IoT), surveillance systems, and mobile applications to build interconnected and resilient tourism environments [

5,

6]. The role of digital technologies is particularly important in reducing risks and building trust between tourists and local communities [

4,

7]. The implementation of smart surveillance systems and security applications contributes to strengthening the subjective sense of safety, while improved digital infrastructure ensures greater control and more effective responses to potential crisis situations [

8]. At the same time, the digitalisation of resource management and the introduction of environmentally responsible technological solutions support long-term sustainability and reduce the negative impacts of tourism on the environment [

8,

9].

Although an increasing number of studies analyse the application of digital technologies in tourism, their effects on tourists’ behavioural intentions in the context of security and sustainability remain insufficiently explored [

10]. Furthermore, comparative research encompassing different urban tourist centres is rare, even though the comparison of diverse socio-economic and cultural contexts can reveal both universal and context-specific patterns in tourist behaviour [

10,

11]. Considering this, the present study applies the theoretical framework of the Norm Activation Model (NAM), which provides deeper insights into how awareness of consequences, ascription of responsibility, and personal norms influence tourists’ intentions [

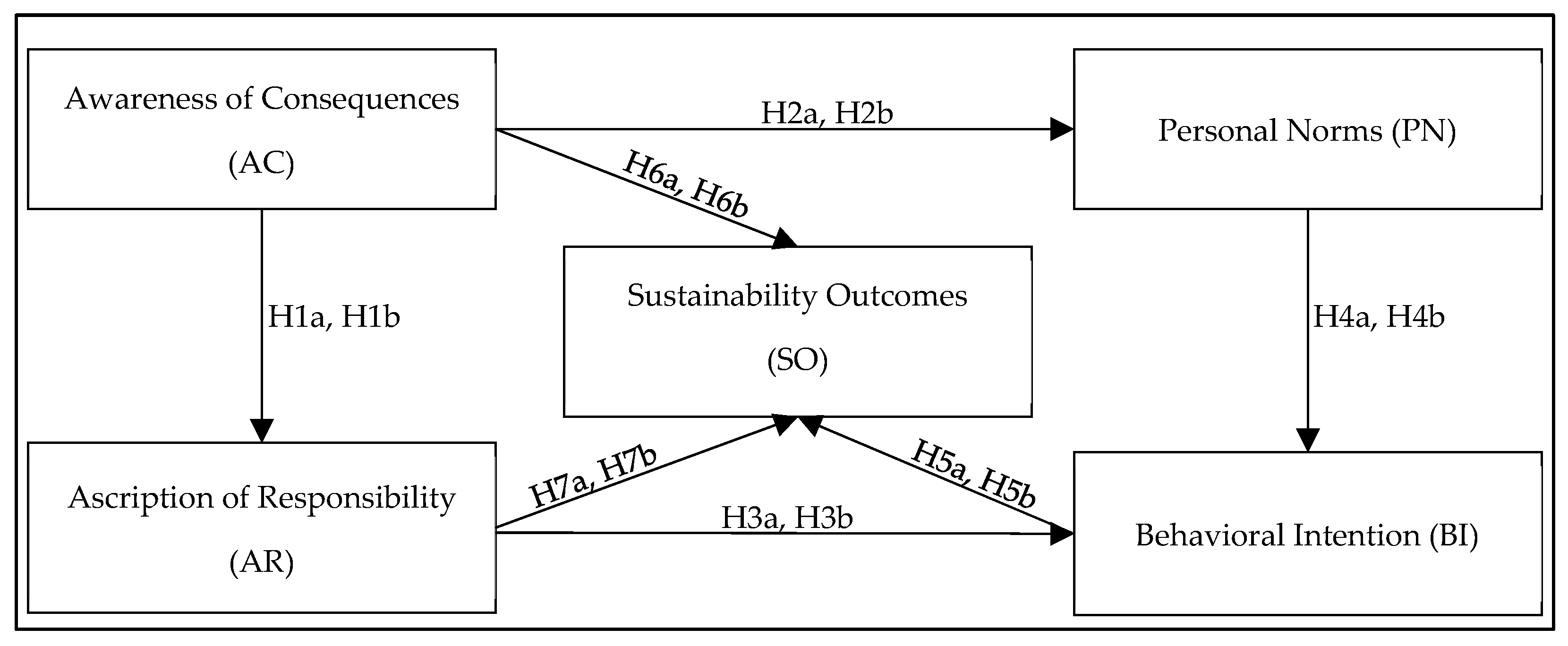

12,

13]. The model is further extended with the construct of “Sustainability Outcomes” in order to incorporate indicators linking security with the long-term sustainability of tourist destinations.

While the Norm Activation Model (NAM) has been extensively applied in environmental studies and, to some extent, in tourism research, it has not previously been extended with the construct of Sustainability Outcomes in the domain of digital security in tourism. This study therefore introduces a novel perspective by linking digital technologies for safety with long-term sustainability outcomes, thus enriching the NAM framework and addressing a significant gap in the literature. By doing so, it allows for a deeper theoretical understanding of how tourists’ awareness of consequences, responsibility, and personal norms translate into behavioural intentions within digitally enhanced, sustainable destinations.

The aim of the research is to examine how digital technologies affect perceptions of security and sustainability in tourist destinations, with particular reference to Almaty (Kazakhstan) and Belgrade (Serbia), and to determine their role in shaping tourists’ behavioural intentions. Conducting the study in two different tourist destinations is of particular importance, as it enables comparative analysis across diverse cultural, institutional, and socio-economic contexts. Almaty represents a dynamically growing destination in Central Asia with pronounced processes of digitalisation and modernisation, while Belgrade is one of the key tourist hubs in Southeast Europe with its specific historical, cultural, and infrastructural framework. Comparing these two cities allows for the identification of similarities and differences in the perception and acceptance of digital technologies, thereby contributing to a deeper understanding of the role of cultural and institutional factors in strengthening the security and sustainability of tourism. In this way, the study not only tests the applicability of the Norm Activation Model (NAM) in different settings but also offers guidance to policymakers and destination managers on adapting digital transformation strategies to specific local conditions.

3. Methodology

In this research, the Norm Activation Model (NAM), originally developed in previous research [

83] and later expanded in fields such as environmental protection, tourism, and sustainable behaviour, was applied. The NAM assumes that individual behaviour is not conditioned solely by personal interests but also by internal norms, moral obligations, and awareness of consequences. In this study, the model was further extended with the construct of Sustainability Outcomes to establish the link between tourist security, digital technologies, and the long-term sustainability of destinations. The constructs employed in the research include Awareness of Consequences (AC), referring to awareness of the consequences of an unsafe environment and the lack of digital solutions; Ascription of Responsibility (AR), denoting the attribution of responsibility to tourists and institutions for respecting and implementing safety procedures; Personal Norms (PN), representing tourists’ personal norms and moral obligations related to behaviour that supports security and sustainability; Behavioral Intention (BI), referring to tourists’ intentions to choose, revisit, or recommend a destination that employs digital technologies to strengthen security and sustainability; and Sustainability Outcomes (SO), representing the effects arising from the integration of digital technologies and security systems into sustainable development, such as a stable inflow of tourists, strengthened trust within the local community, and a positive regional image. The measurement items were developed based on established NAM literature [

75,

76,

80,

81] and were adapted to the context of digital technologies in tourism security and sustainability. The AC items were reformulated to capture the consequences of unsafe use or absence of digital solutions, while the PN items focused on tourists’ moral obligation to adopt or respect digital systems. The SO construct was newly developed, drawing on literature on digital transformation and sustainability, to reflect long-term outcomes such as destination image, community trust, and economic stability. A pilot pre-test with a small group of respondents was conducted to ensure clarity and reliability, and a back-translation procedure was applied for the multilingual versions of the questionnaire.

For the empirical part of the study, a structured questionnaire was developed, with each construct operationalised through at least five items measured on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire included items examining tourists’ perceptions of the application of digital technologies in the field of security, their willingness to cooperate with institutions, personal norms related to safety and sustainability, behavioural intentions for the future, and expected long-term effects of digitalisation on destinations.

The research was conducted as a comparative case study in two urban destinations: Almaty in Kazakhstan and Belgrade in Serbia, during the period from January 2025 to July 2025. The selection of these destinations was based on their status as regional centres with increasing tourist flows, as well as on their different socio-economic and cultural contexts, which enable a deeper comparative analysis. The sample consisted of tourists who were staying in these cities at the time of the survey, and the sampling technique applied was convenience sampling. It was planned to collect between 200 and 250 valid questionnaires in each destination, ensuring sufficient statistical power for the application of multivariate analysis methods.

The data were collected by trained interviewers at airports, railway stations, tourist information centres, and hotels. In Kazakhstan, the questionnaire was available in Kazakh, Russian, and English, while in Serbia it was available in Serbian and English, in order to cover different tourist profiles. For data processing, a combination of statistical methods was employed, including descriptive statistics to describe the sample and basic variables, partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) to test the relationships between constructs and verify hypotheses, as well as Multi-Group Analysis (MGA). This combination made it possible to analyse the results both at the descriptive level and within complex causal relationships, thus contributing to the reliability and validity of the research. The factors were adapted from the Norm Activation Model [

75,

76,

83,

84], with the addition of the construct of Sustainability Outcomes based on sustainable development goals and contemporary literature. The only conditions for the anonymous participation of respondents were that they were of legal age and that they were tourists in Almaty (KZ) or Belgrade (RS), meaning individuals without permanent residence in these cities.

4. Results

A total of 435 respondents participated in the study (

Table 1), with 207 from Almaty (KZ) and 228 from Belgrade (RS). In terms of gender, the sample structure in Almaty consisted predominantly of men (63.8%) compared to women (36.2%), while in Belgrade the situation was the opposite—women constituted the majority (61.0%), and men accounted for 39.0%. At the level of the overall sample, the gender distribution was almost balanced (men 50.8%, women 49.2%).

Regarding age distribution, the largest group in both cities belonged to the 25–34 age category (Almaty: 31.4%; Belgrade: 31.6%), representing nearly one-third of the sample (31.5%). They were followed by the groups aged 35–44 (19.5%) and 45–54 (16.1%), while the younger respondents aged 18–24 (16.8%) and the older group aged 55 and above (16.1%) were represented in nearly equal proportions. These data indicate that the sample was relatively balanced across age categories, with a dominance of younger adults.

As for the level of education, the majority of respondents had completed university studies (Almaty: 42.5%; Belgrade: 49.6%; overall: 46.2%). Secondary education was reported by 32.9% of participants, while the smallest group consisted of those with completed master’s or doctoral studies (20.9%). This demonstrates that the sample was predominantly highly educated, which is consistent with the profile of tourists who more frequently use digital technologies in their travel experience.

Table 2 presents the detailed results of descriptive statistics for all items of the research instrument for the samples in Almaty (KZ) and Belgrade (RS). Within the factor Awareness of Consequences (AC), the mean values in both cities ranged between 3.39 and 4.20. Respondents in Almaty expressed the highest level of agreement with the statement that the tourism industry suffers in the long term if the implementation of digital security solutions is neglected (M = 4.16), while in Belgrade the same statement received the strongest support (M = 4.20). The lowest mean values were recorded for item AC2 in both cities (M = 3.60 in Almaty; M = 3.39 in Belgrade), suggesting that respondents were somewhat more moderate in their views that the lack of modern security systems directly undermines the image of a destination.

For the factor Ascription of Responsibility (AR), Almaty respondents demonstrated strong agreement with personal responsibility in using digital applications and complying with safety protocols (ar1, M = 4.22), while in Belgrade the highest support was recorded for the duty to cooperate with institutions through the use of digital systems (ar2, M = 4.22). Interestingly, the values for ar3 and ar4 in Almaty were notably lower (M = 3.22; M = 3.10) compared to Belgrade (M = 4.10; M = 3.84), indicating that tourists in Serbia are more inclined to accept collective responsibility in the application of digital safety tools.

Regarding Personal Norms (PN), in Belgrade the strongest agreement was related to the moral condemnation of ignoring digital safety measures (pn2, M = 4.19), whereas in Almaty the highest value was attributed to the sense of moral obligation to support destinations applying digital systems (pn1, M = 3.85). The lowest mean value in Almaty was recorded for pn5 (M = 3.44), while in Belgrade the same indicator received significantly higher ratings (M = 4.05), reflecting a different degree of internalisation of personal responsibility between the two contexts.

For the factor Behavioral Intention (BI), mean values in Almaty were relatively consistent (3.79–3.90), whereas in Belgrade stronger variations appeared: the highest agreement referred to the willingness to revisit a destination with digital systems (bi2, M = 4.21), while the lowest value was given to the prioritisation of airports and infrastructure with digital control measures (bi4, M = 3.12). This indicates that tourists in Serbia place greater emphasis on personal experiences of security than on infrastructural aspects.

Within the factor Sustainability Outcomes (SO), respondents in Almaty showed the highest agreement with the statement that the implementation of digital security strengthens the positive image of the region (so4, M = 4.05), while in Belgrade the highest rating was recorded for the statement that digital security encourages long-term tourist loyalty (so7, M = 3.97). The lowest values in both cities referred to the economic aspect (so2, M = 3.95 in Almaty; M = 3.15 in Belgrade), which may indicate lower awareness among respondents of the long-term financial effects of digital investments in tourism.

Table 3 presents the results of descriptive statistics, as well as the indicators of reliability and convergent validity for the five constructs used in the research through factor analysis Awareness of Consequences (AC), Ascription of Responsibility (AR), Personal Norms (PN), Behavioral Intention (BI), and Sustainability Outcomes (SO)—separately for the samples in Almaty (KZ) and Belgrade (RS). The values of Cronbach’s α for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. The highest reliability was recorded for the construct AR in Almaty (α = 0.922), while the lowest value of α = 0.749 was observed for PN in Belgrade, though it still remained within acceptable limits. In addition, the Composite Reliability (CR) values ranged between 0.85 and 0.95, confirming high construct stability. All constructs also demonstrated satisfactory values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE), which exceeded the 0.50 threshold (ranging from 0.60 to 0.88), thereby confirming convergent validity.

Regarding the mean values (M), they ranged between 3.49 and 4.03, indicating a moderately high level of agreement among respondents with statements related to the application of digital technologies in the context of security and sustainability of tourist destinations. In Almaty, the construct SO recorded the highest score (M = 3.89), while in Belgrade the highest value was observed for AR (M = 4.03). The lowest mean values were recorded for BI in Belgrade (M = 3.52) and PN in Almaty (M = 3.72). The standard deviations (SD) ranged between 1.10 and 1.22, suggesting relatively consistent responses with moderate variability. These results indicate that respondents in both cities recognised the importance of digital technologies for destination security and sustainability, with practical aspects (SO) being more emphasised in Almaty, while a stronger sense of personal responsibility (AR) was highlighted in Belgrade.

Table 4 presents the indicators of reliability and convergent validity for the five constructs in the two samples through SEM analysis. The CR values were exceptionally high across all constructs (0.89–0.96), indicating stable internal consistency of the measurement scales. Particularly noteworthy are AR and PN (both = 0.96 in both cities), suggesting that the indicators uniformly and reliably reflect the latent construct. Although CR values around 0.96 may raise concerns regarding possible redundancy of some items, within the context of this study such values are acceptable given the clear theoretical coherence and the high loading levels of the indicators. The AVE values for all constructs exceeded the reference threshold of 0.50, thereby confirming convergent validity. The highest convergent validity was recorded for PN (AVE = 0.841–0.840), followed by AR (0.831–0.833) and AC (0.727–0.731), indicating that these constructs explain a substantial proportion of the variance in their indicators. BI and SO demonstrated moderate but clearly acceptable AVE values (BI: 0.651 in Almaty and 0.620 in Belgrade; SO: 0.622 and 0.619), which is common for constructs capturing behavioural intentions and broader perceptions of outcomes. Such values indicate that any slightly weaker individual items were successfully absorbed at the factor level without compromising validity.

The comparison between the two cities demonstrates strong stability of the measurement model: differences in CR and AVE were minimal (most often ≤0.03), allowing the conclusion that the psychometric properties of the scales were practically identical in both contexts. This is significant as it supports the comparability of results (cross-cultural/cross-contextual consistency) and suggests that observed differences in structural relationships (e.g., the effects of AC/AR on BI and SO) do not stem from measurement artefacts but instead reflect genuine variations in respondents’ behaviours and attitudes.

The measurement model meets the key criteria: high reliability (CR ≥ 0.89) and valid convergence (AVE ≥ 0.619) across all constructs and in both samples. These findings justify moving to the evaluation of the structural model (path coefficients, R2, f2, Q2, and bootstrapping) and the testing of the proposed hypotheses. If further evidence of validity is required, it is advisable to also present discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker and HTMT). However, based on the reported indicators, the measurement model can be considered statistically and theoretically adequate.

Table 5 presents the assessment of discriminant validity using the Fornell–Larcker criterion for both samples. The values on the diagonal represent the square root of AVE for each construct, while the off-diagonal values represent the correlations between constructs. The basic requirement of discriminant validity is that the square root of AVE for each construct must be greater than any of its correlations with other constructs. The results show that all diagonal values are greater than the corresponding inter-factor correlations, both in the Almaty sample and in the Belgrade sample.

For example, in Almaty the square root of AVE for the construct AC was 0.85, which exceeded its correlations with AR (0.65), PN (0.58), BI (0.54), and SO (0.67). A similar pattern was observed in Belgrade, where the square root of AVE for AC was 0.84, also higher than all its correlations with other constructs. All other constructs, including AR, PN, BI, and SO, demonstrated the same consistency—the diagonal values (0.90–0.92 in Almaty; 0.78–0.91 in Belgrade) exceeded all off-diagonal values. This confirms that each construct measures a unique phenomenon and that there is no overlap between different constructs.

The comparison of the two samples reveals a high degree of similarity in the correlation structure. In both contexts, the highest correlations were observed between AC and SO (0.67 in Almaty; 0.66 in Belgrade), indicating a close relationship between awareness of consequences and the perception of sustainability outcomes. On the other hand, the lowest correlations were recorded between AC and BI (0.54 in Almaty; 0.53 in Belgrade), suggesting that awareness of consequences has a relatively limited direct connection with behavioural intention, but that this relationship may be mediated by other factors.

Table 6 presents the HTMT values as an additional test of discriminant validity for both samples. In both cases, all values ranged from 0.60 to 0.72. These results are well below the reference thresholds of 0.90 (the stricter criterion) or 0.85 (the conservative criterion), indicating that discriminant validity is not compromised and that each construct measures a distinct phenomenon. In the Almaty sample, the highest HTMT value was observed between AC and SO (0.72), confirming the close association between awareness of consequences and the perception of sustainability outcomes. The lowest values were recorded for the relationships AC–BI (0.61) and PN–SO (0.66), suggesting relatively moderate connections between these constructs. In Belgrade, the pattern was similar but with slightly lower values. The strongest associations were again between AC and SO (0.70) and BI and SO (0.69), indicating that respondents in Serbia also recognised the importance of digital security for long-term sustainability and for their own behaviour in tourism. The weakest relationship was recorded between AC and BI (0.60), confirming that awareness of consequences has a more limited direct effect on behavioural intentions compared to indirect factors such as personal norms and ascription of responsibility.

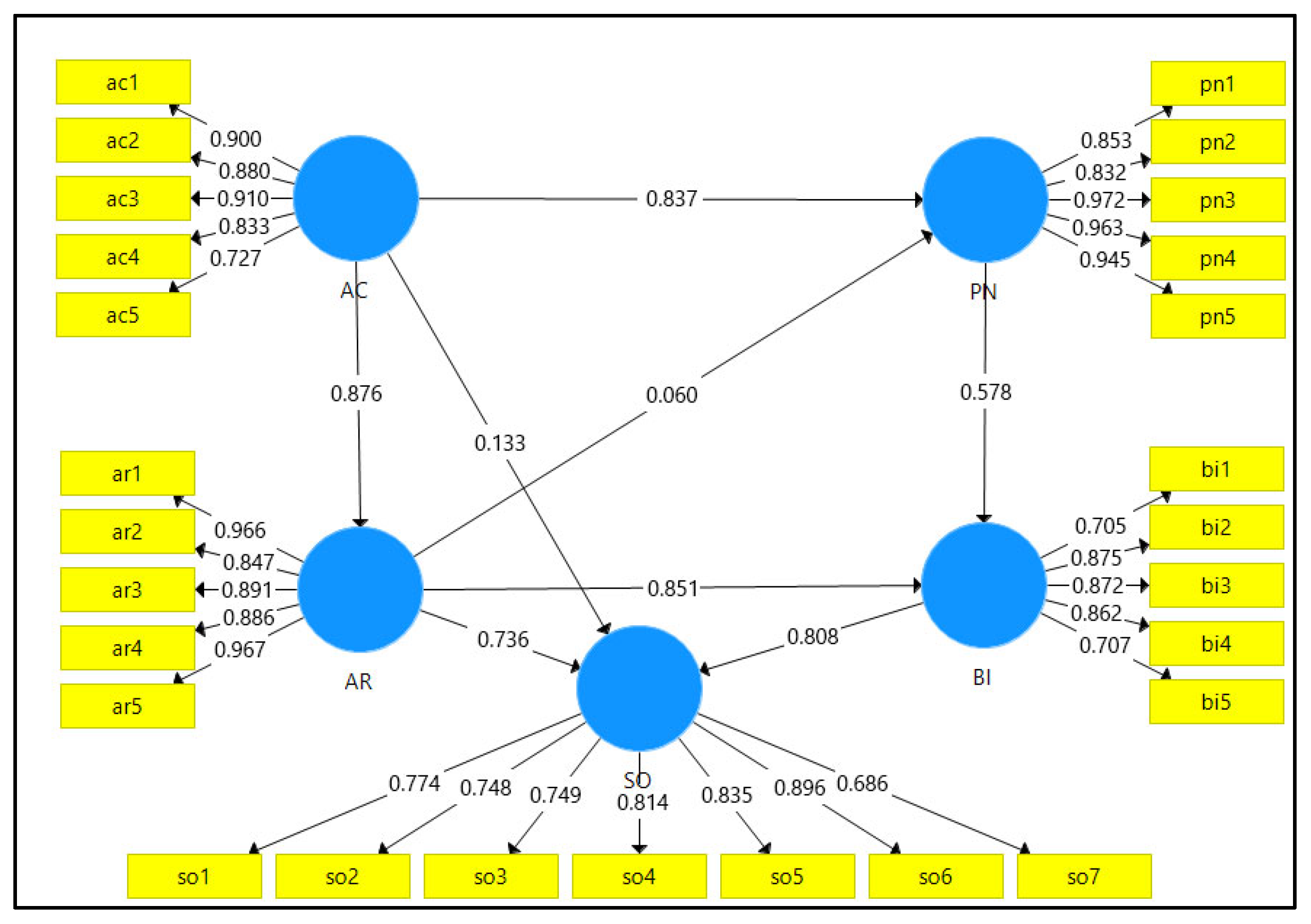

Figure 2 illustrates the structural model obtained through PLS-SEM analysis for the Almaty sample. The model presents the relationships among the five latent constructs. The values next to the indicators (ac1–ac5, ar1–ar5, pn1–pn5, bi1–bi5, so1–so7) represent the outer loadings, which indicate how well individual items reflect their respective constructs. All values exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, demonstrating high convergent validity and measurement reliability.

The arrows between latent variables display the path coefficients (β), which reflect the strength and direction of the effects between constructs. The strongest effects were observed for the relationships AC → PN (β = 0.837) and AR → SO (β = 0.736), showing that awareness of consequences strongly influences the formation of personal norms, while ascription of responsibility exerts a direct and substantial effect on sustainability outcomes. In addition, significant relationships were also found for AR → BI (β = 0.851) and SO → BI (β = 0.808), suggesting that both tourists’ sense of responsibility and their perception of sustainability strongly encourage their behavioural intentions.

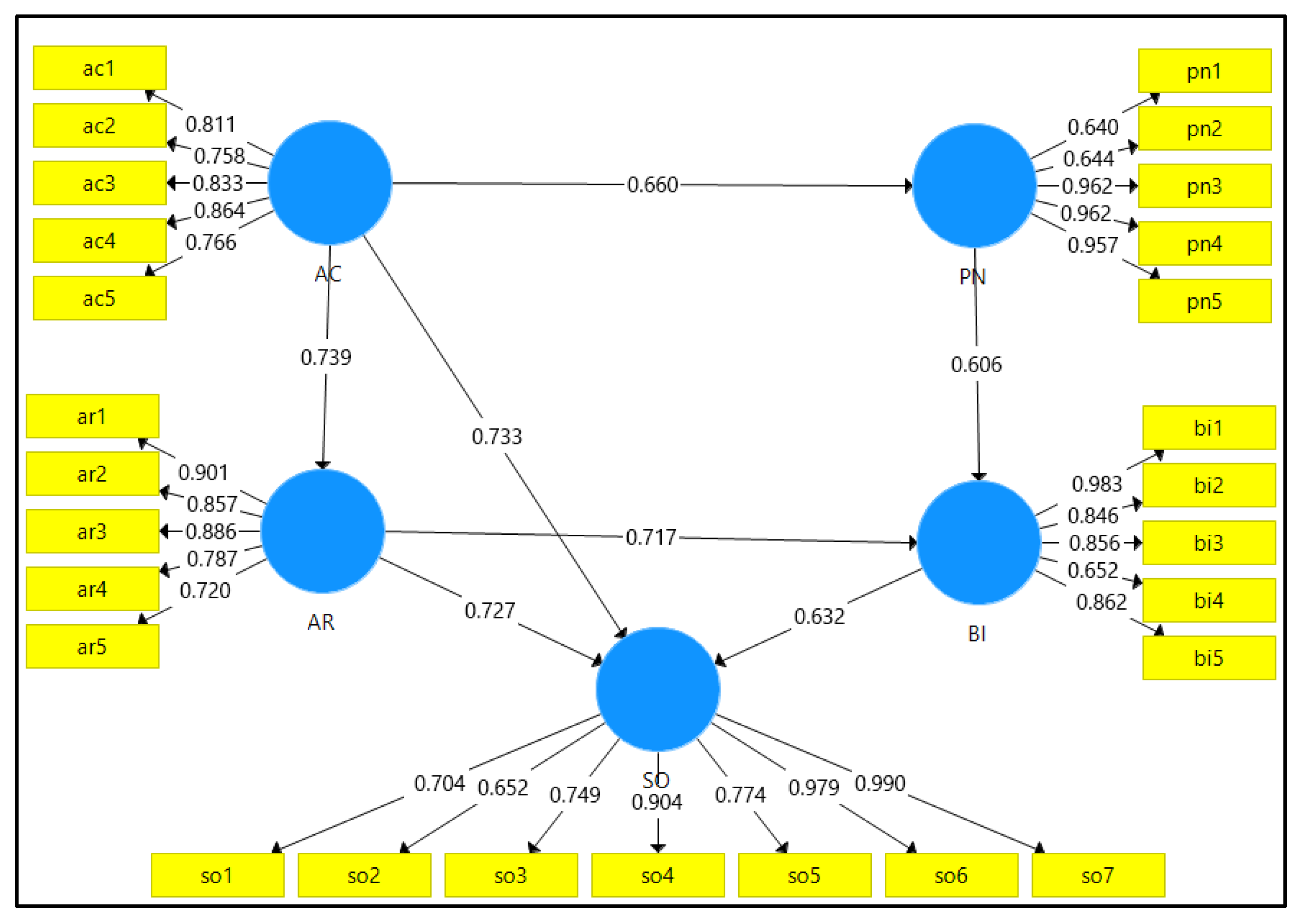

Figure 3 presents the results of the structural model obtained through PLS-SEM analysis for the Belgrade sample. The outer loadings of the indicators (ac1–ac5, ar1–ar5, pn1–pn5, bi1–bi5, so1–so7) were generally above 0.70, confirming good convergent validity and instrument reliability. Although pn1 and pn2 showed slightly lower values (~0.64), they were still acceptable, as they did not compromise the overall reliability of the construct. The key path coefficients (β) indicate strong and statistically significant relationships between the constructs. The strongest effects were observed for AR → SO (β = 0.727) and AR → BI (β = 0.717), demonstrating that ascription of responsibility is a crucial factor in shaping both sustainability outcomes and tourists’ behavioural intentions. The relationships AC → AR (β = 0.739) and AC → PN (β = 0.660) were also significant, suggesting that awareness of consequences directly strengthens both responsibility and personal norms. The relationship PN → BI (β = 0.606) shows that tourists’ moral norms significantly influence their behavioural intentions, although with somewhat lower strength compared to the direct effects of AR and SO.

The results of the bootstrapping analysis (

Table 7) confirmed that all proposed hypotheses were statistically supported (

p < 0.05) in both samples, with positive and generally medium to high path coefficients. In both contexts, awareness of consequences (AC) had a significant effect on ascription of responsibility (AR) and personal norms (PN), thereby confirming the theoretical foundations of the NAM greater perception of potential risks and negative outcomes directly strengthens tourists’ sense of duty and internalised moral obligations. Ascription of responsibility then strongly influenced personal norms, reinforcing the normative channel of influence within the model. With regard to behavioural intentions (BI), in both cities the strongest effect originated from ascription of responsibility (Almaty β = 0.717; Belgrade β = 0.766), indicating that tourists who feel personally responsible show a greater willingness to behave in line with safety and sustainability guidelines. In addition, personal norms (Almaty β = 0.606; Belgrade β = 0.716) and perceptions of sustainability outcomes (SO) (Almaty β = 0.632; Belgrade β = 0.695) had significant effects on BI. This means that tourists’ moral obligations and the perceived benefits of digital security for the destination (economic stability, community trust, positive image) strongly encourage their intentions to choose and recommend the destination.

The relationship between AR and SO (Almaty β = 0.727; Belgrade β = 0.827) was particularly significant, showing that a sense of personal responsibility directly fosters positive and sustainable outcomes, thereby strengthening the economic, social, and image dimensions of the tourism offer. In Almaty, the relationship between AC and SO (β = 0.133) was very weak and likely mediated through AR and PN, whereas in Belgrade this relationship was considerably stronger and statistically significant (β = 0.233), which may indicate a greater sensitivity among tourists in Serbia to information about the consequences of insecurity. The results for both samples confirm the strong applicability of the NAM in the context of digital technologies in tourism. Awareness of consequences activates responsibility and personal norms, which, together with perceptions of sustainability outcomes, shape tourists’ intentions. In Almaty, sustainability outcomes had the most pronounced effect on intentions, while in Belgrade the dominant effects came from personal responsibility, reflecting cultural and contextual differences in the acceptance of digital security as a factor of sustainable destination development. From a practical perspective, interventions that highlight the consequences of risks, strengthen tourists’ sense of personal responsibility, and make the positive effects of digital safety measures visible are most likely to lead to greater loyalty, destination choice, and recommendation.

The results of the Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) (

Table 8) enabled a direct comparison of path coefficients between the samples from Almaty (KZ) and Belgrade (RS), thereby providing insight into whether there are statistically significant differences in the strength and direction of relationships within the proposed model. The analysis shows that although the model as a whole functions in both contexts, there are clear differences reflecting specific cultural and institutional characteristics. Significant differences were identified in the relationships AC → AR (

p = 0.003), AC → PN (

p = 0.001), and AR → PN (

p = 0.011). These findings indicate that awareness of consequences exerts a stronger influence on ascription of responsibility and the formation of personal norms among respondents in Belgrade than in Almaty. Practically, tourists in Serbia more strongly internalise the consequences of insecurity and transform them into a sense of personal responsibility and moral obligation. In Almaty, this effect is also present but with slightly lower intensity, which may be the result of different social and institutional conditions or varying levels of development in digital security systems.

Significant differences were also observed in the paths PN → BI (p = 0.004), AR → SO (p = 0.019), and AC → SO (p = 0.002). Among respondents in Belgrade, personal norms had a stronger impact on behavioural intentions, suggesting that in the Serbian context internal moral mechanisms play a decisive role in shaping tourists’ willingness to revisit or recommend a destination. At the same time, ascription of responsibility had a stronger direct effect on sustainability outcomes in Belgrade, indicating that responsible tourist behaviour contributes to greater community trust, a stronger image, and more stable tourism development. Particularly noteworthy is the finding regarding AC → SO, where the effect in Almaty was weak (β = 0.133), while in Belgrade it was stronger and statistically significant (β = 0.233). This suggests that tourists in Serbia directly associate awareness of consequences with the perception of sustainability, whereas in Kazakhstan this effect functions mainly indirectly through other constructs.

The relationships AR → BI (p = 0.110) and SO → BI (p = 0.055) did not show statistically significant differences between Almaty and Belgrade. This means that in both contexts the pattern of influence of ascription of responsibility and sustainability outcomes on behavioural intentions is consistent and stable, indicating the universality of these relationships regardless of cultural specificities. In other words, tourists in both cities, when recognising their responsibility or perceiving positive sustainability outcomes, consistently show a greater willingness to revisit or recommend the destination.

The results of the MGA show that the NAM performs well in both samples, but with certain differences in the intensity of specific paths. In Belgrade, personal responsibility and moral norms emerged as stronger mechanisms influencing behavioural intentions and sustainability outcomes, while in Almaty these relationships were present but with lower values. Furthermore, in the Serbian sample, awareness of consequences was more directly linked to the perception of sustainability, whereas in the Kazakhstani context this relationship remained weak and mediated. These findings highlight cultural and institutional differences in the way tourists perceive and adopt digital security technologies as factors of sustainable destination development.

5. Discussion

This research aimed to examine the role of digital technologies in strengthening the security and sustainability of tourist destinations through the application of the Norm Activation Model (NAM). The results show that the NAM was fully supported in both samples, confirming its strength and applicability in the context of contemporary tourism. All constructs awareness of consequences (AC), ascription of responsibility (AR), personal norms (PN), behavioural intentions (BI), and perceptions of sustainability outcomes (SO) demonstrated significant and positive interrelationships, thereby confirming the initial assumption that digital technologies play a crucial role in creating a safe and sustainable tourism environment.

The results of the Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) provide important insights into the differences between Almaty (KZ) and Belgrade (RS). Although all hypotheses were confirmed in both samples, the analysis revealed variations in the strength of specific relationships. In Belgrade, the effects AC → AR and AC → PN were stronger, indicating that tourists in Belgrade more strongly translate risk awareness into a sense of responsibility and moral obligation. The stronger effects of AC → AR and AC → PN observed in Belgrade can be explained by the broader socio-cultural and institutional context of Serbia. As a post-socialist society with strong traditions of collectivism and solidarity, Serbia places strong emphasis on shared responsibility and moral obligations, further reinforced by public debates on sustainability and transparency driven by the country’s European integration. By contrast, in Kazakhstan, where Almaty has undergone rapid modernisation and digitalisation, responsibility is more often associated with institutional authority rather than internalised moral norms. Public awareness of digital security and sustainability is still developing, and tourists may rely more on top-down institutional assurances than on individual responsibility. These contextual differences illustrate that the explanatory power of NAM is moderated by historical, cultural, and institutional factors that shape the way individuals interpret and act upon digital security and sustainability challenges. These findings are consistent with the classical works of Stern (2000) and Han (2014) [

75,

84], which showed that the NAM consistently explains environmental and responsible behaviour. However, in this study the effect was analysed through the lens of digital technologies, representing an important extension of the existing theoretical framework.

Differences were particularly evident in the relationships AR → SO and AC → SO. In Belgrade these paths were stronger, indicating that tourists more closely link personal responsibility and awareness of consequences with broader sustainability outcomes such as a positive destination image, a stable local economy, and community trust. In Almaty these effects were present but weaker. Similar findings were reported by a previous study [

77] on tourists’ ecological behaviour in China, where cultural context strongly shaped the influence of NAM constructs. Our results contribute to this line of research by showing that in the domain of digital technologies, cultural and institutional factors also shape the strength of relationships.

These findings demonstrate that the contribution of this study extends beyond showing that differences exist between the two destinations. By integrating Sustainability Outcomes into the NAM and applying it in a comparative setting, the research reveals how cultural and institutional contexts condition the strength of key relationships between awareness, responsibility, norms, and sustainability. This advances theoretical understanding by showing that NAM is not only a universal explanatory model but one whose mechanisms vary in intensity depending on socio-cultural realities. At the same time, the results provide practical guidance for destination managers and policymakers: in contexts such as Belgrade, strategies should focus on engaging tourists through personal responsibility and co-creation of sustainable practices, while in contexts such as Almaty, stronger institutional communication and policy support are needed to raise awareness of the consequences of insecurity and promote the adoption of digital technologies.

Certain relationships did not show significant differences between Almaty and Belgrade. The links AR → BI and SO → BI were stable in both samples, pointing to the universality of these constructs. These results confirm the findings of Onwezen et al. (2013) [

76] who emphasised that personal responsibility and positive outcomes are consistent determinants of behaviour across cultural settings. In this research it was shown that this universality also applies in the field of digital tourism, which had not been empirically tested before. Comparisons with recent works on smart destinations and tourism digitalisation further reinforce these findings. Buhalis & Amaranggana (2015) [

78] emphasised that digital technologies form the foundation of the smart destination concept, as they integrate infrastructure, security, and sustainability. Xiang et al. (2017) [

79] highlighted the importance of big data analytics and mobile applications in creating safer tourism environments. Our research confirms these findings but also extends them by showing that the effects of digital technologies are not uniform across socio-cultural contexts. In Belgrade, for example, tourists more strongly associate digital security with sustainability, whereas in Almaty this link is weaker and mediated by other factors.

Moreover, the results are in line with studies from other parts of the world that analysed the NAM in tourism. Han (2014) [

75] demonstrated that NAM successfully explains tourists’ intentions to support environmental policies in the hotel industry. Zhu et al. (2022) [

80] applied NAM in the context of cultural tourism in South Korea and reached similar conclusions personal norms and responsibility remain key predictors of behaviour. Our study, however, adds a new dimension by showing that digital security and sustainability represent a domain in which NAM retains equally strong explanatory power. The findings of this research are aligned with the rich body of literature confirming NAM as a suitable model for studying environmental, socially responsible, and tourism behaviour, but they extend it by showing that the same mechanisms also operate in the domain of digital technologies. At the same time, the MGA reveals that cultural and institutional differences influence the strength of specific relationships, making this study the first attempt to test NAM in a comparative context of the digital transformation of tourism.

5.1. Limitations of the Research

Although this research has provided important insights into the role of digital technologies in strengthening the security and sustainability of tourist destinations, several limitations should be noted. First, the study was conducted on two urban samples, Almaty (KZ) and Belgrade (RS). While this offers a valuable comparative framework, it at the same time limits the generalisability of the findings to other contexts, particularly rural destinations or those at different stages of digital transformation. The cultural, institutional, and economic specificities of these two cities may significantly influence tourists’ perceptions, and the results cannot be automatically extended to all tourism environments.

The study relied on self-reported data collected through a structured questionnaire, which carries the risk of subjectivity, socially desirable responses, and potential discrepancies between declared intentions and actual behaviour. In addition, the research applied a cross-sectional methodology, meaning that the results reflect a single moment in time and do not allow for tracking dynamic changes in tourists’ attitudes and behaviours. Moreover, since the data were collected using a single instrument, the possibility of common method bias cannot be excluded, even though statistical checks indicated that collinearity remained within acceptable thresholds.

A further limitation concerns the choice of model. Although the Norm Activation Model (NAM) proved highly applicable in this context, other relevant factors such as perceived usefulness of technology, the level of digital literacy, or cultural values were not included, even though they could further explain differences in tourist behaviour. In addition, although a multi-group analysis was performed, future research should also systematically test measurement invariance (e.g., MICOM procedure) when conducting cross-cultural comparisons. Integrating additional theoretical frameworks such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) or the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) could also provide a more comprehensive picture. While this study covered two distinct geographical and cultural contexts, future research should include a larger number of destinations and adopt longitudinal as well as mixed-methods designs. Combining quantitative surveys with qualitative approaches, such as interviews or case studies, would provide deeper insights into tourists’ attitudes and experiences regarding the use of digital technologies in tourism.

Limitation relates to the demographic structure of the sample. The gender distribution varied considerably between the two destinations, with a predominance of male respondents in Almaty and female respondents in Belgrade. Moreover, the overall educational level of the participants was relatively high, with more than two-thirds holding a university degree or postgraduate qualification. These characteristics indicate that the samples may not be fully representative of the broader tourist populations in either city. Given that convenience sampling was applied at key transport hubs and tourist locations, caution is required when generalising the findings beyond the studied contexts.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This research has important theoretical implications as it extends the application of the Norm Activation Model (NAM) to the domain of digital technologies in tourism. While NAM was originally developed to explain environmental and prosocial behaviour [

83,

84] the findings of this study demonstrate that the same mechanisms operate in the context of digital security and the sustainability of tourist destinations. By confirming all proposed hypotheses in two different cultural and institutional settings, the study expands the existing body of knowledge and points to the universality of the NAM in contemporary tourism. One of the key implications is the confirmation that the constructs awareness of consequences (AC), ascription of responsibility (AR), and personal norms (PN) remain central mechanisms in shaping behavioural intentions (BI) as well as in forming perceptions of sustainability outcomes (SO). In this way, the study contributes to the literature by extending NAM from its traditional focus on environmental and socially responsible behaviour to the field of digital technologies, showing that the digital transformation of tourism can be explained by the same psychological mechanisms.

The results of the Multi-Group Analysis (MGA) reveal that although NAM is universal, its intensity varies across cultural contexts. In Belgrade, the paths AC → AR, AC → PN, and PN → BI were stronger, whereas in Almaty these relationships were more moderate. This confirms previous findings [

75,

76,

83,

84] that cultural and institutional contexts can shape the strength of relationships in NAM, but for the first time demonstrates that such variations also occur in the context of digital security technologies. The theoretical implications also include the extension of the NAM through the incorporation of the construct of sustainability outcomes (SO). While NAM in its original form was primarily focused on moral norms and behaviour, this study shows that digital technologies as a factor of security have a direct impact on the perception of sustainability. In this way, the model has been advanced with an additional dimension that links individual behaviour to broader social and economic outcomes.

5.3. Practical Implications

This research carries important practical implications for destination management and the development of digital transformation strategies. The confirmed relationships within the NAM indicate that digital technologies are not merely tools for service improvement but essential mechanisms for building security and long-term sustainability. First, the results show that awareness of consequences and personal responsibility play a central role in shaping tourist behaviour. This means that destination managers and tourism institutions must more actively inform tourists about the importance of digital security solutions. Clear communication on how smart surveillance systems, mobile applications, and IoT devices enhance safety can encourage tourists to use them actively and foster greater trust in the destination.

The comparative analysis between Almaty and Belgrade revealed that tourists in Serbia are more sensitive to moral norms and responsibility, while in Kazakhstan these links are somewhat weaker. This suggests that, in the Serbian context, it is necessary to emphasise tourists’ personal contribution to maintaining safety and sustainability, whereas in Kazakhstan institutions should invest more in raising awareness of the consequences of insecurity and more actively demonstrate the benefits of digital systems. Tailoring strategies to the specific cultural context thus proves essential for the effective implementation of digital technologies.

The results further demonstrated that tourists directly associate digital security with perceptions of sustainability. This implies that digital technologies should not be regarded merely as costs but as investments that build long-term loyalty, positive image, and stable economic development. Destinations that integrate digital tools into their strategies—from mobile applications for communication with tourists to artificial intelligence systems for real-time data analysis—are more likely to establish a competitive advantage.

For destination managers, these findings highlight the importance of designing training programmes for staff, introducing participatory applications that allow tourists to co-create safe and sustainable experiences, and strengthening transparent communication about digital safety measures. For public policymakers, the study emphasises the need to develop supportive regulatory frameworks, offer incentives for investments in digital infrastructure, and promote digital literacy through educational campaigns. By coordinating institutional support with managerial strategies, destinations can ensure that the adoption of digital technologies not only increases immediate safety but also contributes to the broader goals of sustainable tourism development.

5.4. Recommendations for Future Research

Although this research has provided valuable insights into the role of digital technologies in strengthening the security and sustainability of tourist destinations, several directions for future studies can be identified. It is recommended to extend the analysis to a larger number of destinations across different regions of the world in order to determine whether the results obtained can be generalised beyond Almaty and Belgrade. Including destinations with varying levels of digital transformation and institutional support would allow for broader comparative insights. Future research could also combine quantitative and qualitative methods. While this study was based on a survey questionnaire and statistical analysis, interviews with tourists, destination managers, and policymakers could provide deeper insights into perceptions of digital security and sustainability. Such a mixed-methods approach would allow for a better understanding of motivations, attitudes, and potential barriers in the adoption of digital solutions.

There is also room for expanding the theoretical framework. Although the Norm Activation Model (NAM) proved to be a strong explanatory tool, integration with other models such as the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) or the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the processes behind the adoption of digital technologies in tourism. This would make it possible to explore additional factors such as digital literacy, perceived usefulness, or cultural values. Finally, future research could focus on longitudinal studies that track changes in tourists’ attitudes and behaviours over time. Such studies would allow researchers to observe how technological development, institutional measures, or global events (e.g., health crises or economic instabilities) influence perceptions of security and sustainability in tourism.