1. Introduction

In the current economic climate, customer satisfaction has become the deciding factor in selecting an automotive repair service provider. Car dealerships and authorized service networks are in fierce competition, and the quality of the services offered is essential for attracting and retaining clients. Although awareness regarding the importance of service quality has increased, there are still significant shortcomings in the implementation, standardization, and monitoring of operational processes within many organizations in the automotive repair sector.

At the same time, the growing societal emphasis on sustainability and efficient resource management places additional pressure on service organizations to align with global development strategies. This study is positioned within the framework of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, specifically SDG 9—Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, and SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production. These goals emphasize the importance of efficient processes, reduced waste, and continuous innovation—objectives that are central to this research.

There are also notable gaps in academic literature related to quality management in automotive service environments. First, there is a lack of integrated conceptual and empirical models that unify European management principles (e.g., ISO 9001 process orientation, risk-based thinking) with Japanese operational philosophies such as Kaizen, Lean Manufacturing, and Poka-Yoke. Second, current research insufficiently defines or applies process-specific KPIs tailored to service operations such as diagnostics, mechanical intervention, or quality control. Finally, existing studies are often limited to manufacturing or logistics, leaving the practical application of these principles in after-sales services largely unexplored.

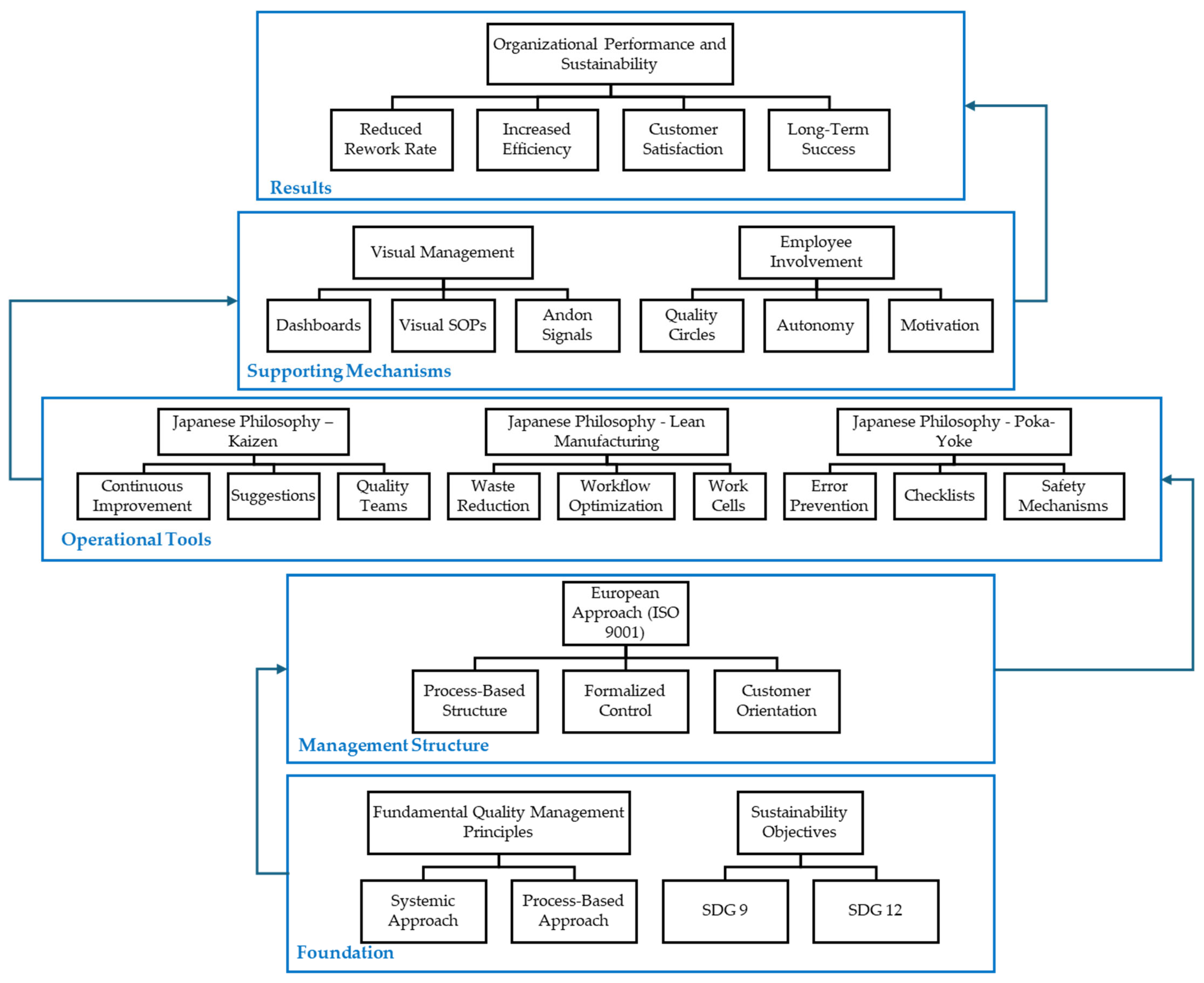

Most existing studies in the literature focus either on applying a single philosophy (e.g., Lean or Kaizen) or on analyzing them in large-scale manufacturing contexts. In contrast, this research addresses a major gap by proposing and empirically validating an integrated, hybrid model of quality management. The model combines Japanese principles (Kaizen, Lean Manufacturing, Poka-Yoke) with a European quality management framework, specifically adapted for the automotive service sector. Our paper demonstrates, with real-world data, that such an approach can be successfully implemented in small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and has a direct, measurable impact on operational performance and sustainability.

The originality and scientific contribution of this research lie in developing a hybrid quality management model that merges European and Japanese principles into a sustainable, replicable framework for automotive repair services. It proposes a holistic and operational approach, identifying and analyzing measurable performance indicators at the departmental level (efficiency, rework, throughput, customer satisfaction) and demonstrating the concrete impact of quality tools through real-world application in service environments. Unlike general conceptual models, this study provides empirical validation based on field data.

The main objectives of the research are:

To design, implement, and quantitatively evaluate the impact of a structured process monitoring system in automotive repair operations;

To identify, apply, and measure the causal impact of selected quality tools (Kaizen, Lean Manufacturing, Poka-Yoke) on key service KPIs;

To analyze key performance indicators (e.g., technician efficiency, rework rates, order completion time) before and after the implementation of these tools;

To assess the correlation between specific improvement tools and performance outcomes using statistical analysis.

To frame these improvements in relation to sustainability objectives, especially process stability, resource usage, and customer satisfaction.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the theoretical considerations and quality management concepts used in this study.

Section 3 details the methodology, including sampling criteria, data collection, and analytical tools.

Section 4 describes the application of process monitoring systems and quality tools.

Section 5 presents the results, including case studies and quantitative analysis.

Section 6 summarizes the conclusions and contributions of the research. A complete bibliography and an appendix with anonymized performance data are provided at the end.

Through this structure, the study provides both a theoretical and a practical contribution by demonstrating how hybrid quality management practices, anchored in sustainability principles, can drive measurable performance gains in the automotive repair industry.

2. Theoretical Considerations

The integration of quality management systems in the automotive sector draws from two major paradigms: the European model, focused on standardization and formal process control (ISO 9001), and the Japanese model, oriented toward continuous improvement, defect prevention, and employee involvement. Although both models have demonstrated significant value in manufacturing, their coordinated application in automotive repair and service environments is less commonly studied.

From a European perspective, quality assurance frameworks emphasize documented procedures, measurable objectives, and compliance with regulatory standards. ISO 9001 [

1] provides a structured approach to process control, risk-based thinking, and customer feedback mechanisms. In service environments, this translates into audit trails, structured work orders, and internal non-conformity management. However, the rigidity of standardized approaches may limit responsiveness in dynamic service contexts.

The Japanese management philosophy contributes with adaptive and employee-driven methods such as Kaizen, Poka-Yoke, Lean, and Visual Management, which complement and compensate for the prescriptive nature of European systems.

Kaizen (continuous improvement) fosters incremental innovation and decentralizes problem-solving to frontline employees. It enhances process awareness and motivates staff involvement through suggestion systems and visual metrics boards.

Lean Manufacturing, adapted to services, focuses on identifying and eliminating non-value-adding activities, optimizing workflow and layout (U-shaped cells), and reducing waste (Muda) in materials, waiting times, or overprocessing.

Poka-Yoke mechanisms serve to prevent human errors at the source—examples in service include checklist confirmations before release or sensor-based verifications during inspections.

Visual Management tools (color-coded work zones, progress boards, and kanban signals) improve transparency, coordination, and early detection of anomalies.

The theoretical compatibility of these systems lies in their complementarity: where ISO offers formalization, Kaizen ensures adaptability; where Lean reduces process redundancy, Poka-Yoke ensures robustness. This hybridization forms the conceptual foundation of the current study, which seeks to explore how the operational combination of these principles impacts real-time performance and service quality in Romanian automotive service centers.

Recent studies reinforce the value of this integrative view, particularly when cross-cultural quality management frameworks are applied to service-based industries. For instance, Ref. [

2] demonstrated that combining ISO 9001 with Lean techniques led to a 38% reduction in rework rates in technical diagnostics departments across several European service chains. Similarly, Ref. [

3] reported improved customer turnaround times and satisfaction scores following the implementation of Kaizen suggestion systems and visual control boards in Japanese post-sale automotive centers.

The authors in [

4] provided further support for Lean-Poka Yoke synergies in reducing procedural errors in complex service processes, especially in high-variability repair environments. The author in [

5] focused on multi-location repair networks and confirmed that visual management tools enhanced cross-shift communication and compliance with SOPs. These findings align with [

6], who integrated 5S and Poka-Yoke in engine component repair stations and observed a 21% improvement in throughput time.

Despite these positive developments, most implementations are concentrated in either highly standardized, corporate-led workshops or in controlled pilot projects, with limited evidence of systemic performance improvements in small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs). For instance, Ref. [

7] highlights the adoption barriers of Lean tools in Eastern European service workshops due to low digital maturity and inconsistent staff training. In [

8], the author argues that many Kaizen efforts fail to generate long-term impact in services when decoupled from structured performance metrics.

Furthermore, the literature still lacks consistent models that measure improvement outcomes through correlation with specific KPIs. Ref. [

9] proposed a hybrid assessment method that combines customer satisfaction indexes with internal quality deviation rates, but this has yet to be validated in the automotive service sector. In addition, Ref. [

10] emphasizes the growing importance of integrating sustainability indicators (e.g., energy consumption, parts reuse rate) within Lean-based service quality audits.

Taken together, these contributions underscore the necessity and relevance of developing a data-supported, cross-methodological model for quality management in the automotive repair service industry, particularly one that is both operationally feasible and strategically sustainable in SMEs.

The studies cited in this paper provide a solid conceptual foundation for understanding quality management tools. Our work extends these theoretical perspectives by demonstrating, through practical application, that these concepts can be integrated into a coherent system to generate synergies. Unlike studies that are limited to a qualitative analysis or a narrow scope, our research offers an empirical validation of effectiveness, using both quantitative metrics and qualitative observations to provide a complete picture of the improvement process.

This paper adopts the service operations management lens, emphasizing flow efficiency, employee autonomy, and process visibility, while anchoring practices in sustainability frameworks. By doing so, the proposed conceptual model aligns with the dual demands of regulatory compliance and operational agility, supporting customer-oriented innovation in automotive repair services.

2.1. Systemic Approach to Management

The systems approach to management, emphasized in the ISO 9001:2015 standard [

11] and detailed in papers [

12,

13], is a fundamental concept in modern quality management that transcends the automotive industry. This approach perceives the organization as a complex and dynamic system, composed of a network of interdependent and interconnected processes, as also emphasized by [

14,

15] in the context of just-in-time production. Each process, regardless of its nature, contributes to the overall goals of the organization. This holistic perspective, also emphasized by Drucker [

16] in his discussion on effectiveness, allows for a thorough understanding of how different processes interact and influence each other [

17,

18].

By identifying and managing these interdependencies, organizations can optimize workflow, eliminate bottlenecks, and ensure a more efficient and effective operation of the whole system, as [

19,

20] in their review of quality management.

An essential aspect of the system’s approach is the identification and management of so-called “Key Quality Checkpoints” [

21,

22,

23]. These are critical points in the system where non-conformities or quality problems may occur. By carefully monitoring and controlling these points, organizations can prevent defects from occurring, reduce the costs associated with their remediation, and ensure a high level of quality in the products and services offered, thus contributing to customer satisfaction and long-term organizational success [

24,

25,

26].

In the specific context of automotive repair services, a systems approach to management involves a detailed analysis of all the processes involved, from the receipt of the vehicle to its handover to the customer. By understanding how each process influences the final quality of the service, organizations can identify opportunities for improvement and implement concrete measures to increase customer satisfaction and strengthen their position in the market [

27,

28,

29].

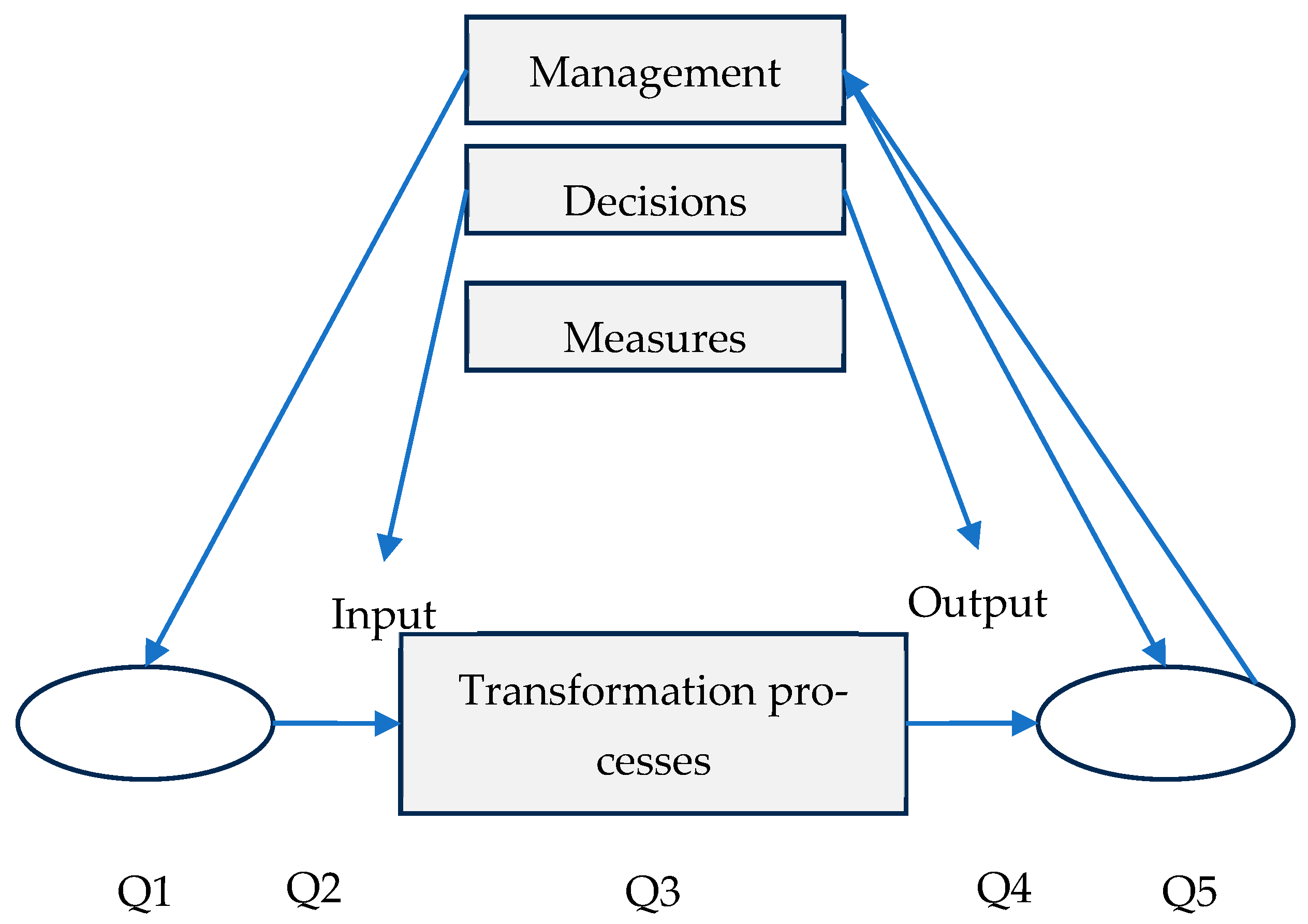

Figure 1, which illustrates the drivers of quality, highlights the importance of a systemic approach to quality management, highlighting the key points where improvement measures can be implemented to ensure that customer and other stakeholders’ requirements are met. This systems approach, as shown in the figure, includes:

Inputs: Resources needed to carry out processes, such as materials, information, personnel and finances. The quality of these inputs has a direct impact on the quality of the outputs and therefore on customer satisfaction.

Transformation processes: The activities by which inputs are transformed into outputs, i.e., finished products or services. The efficiency and effectiveness of these processes are essential to achieve quality results.

Outputs: Finished products or services resulting from transformation processes. The quality of these outputs must meet the requirements and expectations of customers and other stakeholders.

Input–Output Systems: The organizations and individuals that provide input and receive outputs, respectively. Relationships with suppliers and customers are essential to ensure the quality of input and to understand and meet customer needs.

Management (decisions and measures): The management of the organization has a crucial role in setting objectives, making decisions and implementing the necessary measures to ensure quality at all stages of the processes.

Figure 1, which illustrates the quality influencing factors, highlights the importance of a systemic approach to quality management, emphasizing the key points where improvement measures can be implemented to ensure that customers and other stakeholders’ requirements are met. In this context, the symbols Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, and Q5 represent Key Quality Checkpoints or essential stages within the transformation processes, where monitoring and control are vital to prevent non-conformities and ensure the final quality of products or services.

Figure 1 emphasizes that all these elements are interconnected and interdependent. The quality of the outputs (products or services) is influenced by the quality of the inputs, the efficiency of the transformation processes and the management decisions and actions taken.

Therefore, a systems approach is essential to understand and manage all the factors that contribute to the final quality and to ensure the satisfaction of customers and other stakeholders.

2.2. Process-Based Approach

The process-based approach is an essential pillar of quality management, as emphasized in ISO 9001:2015 and detailed in the referenced work [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. This principle promotes the idea that an organization can achieve its desired outcomes more effectively when it structures its activities and resources in the form of well-defined and managed processes.

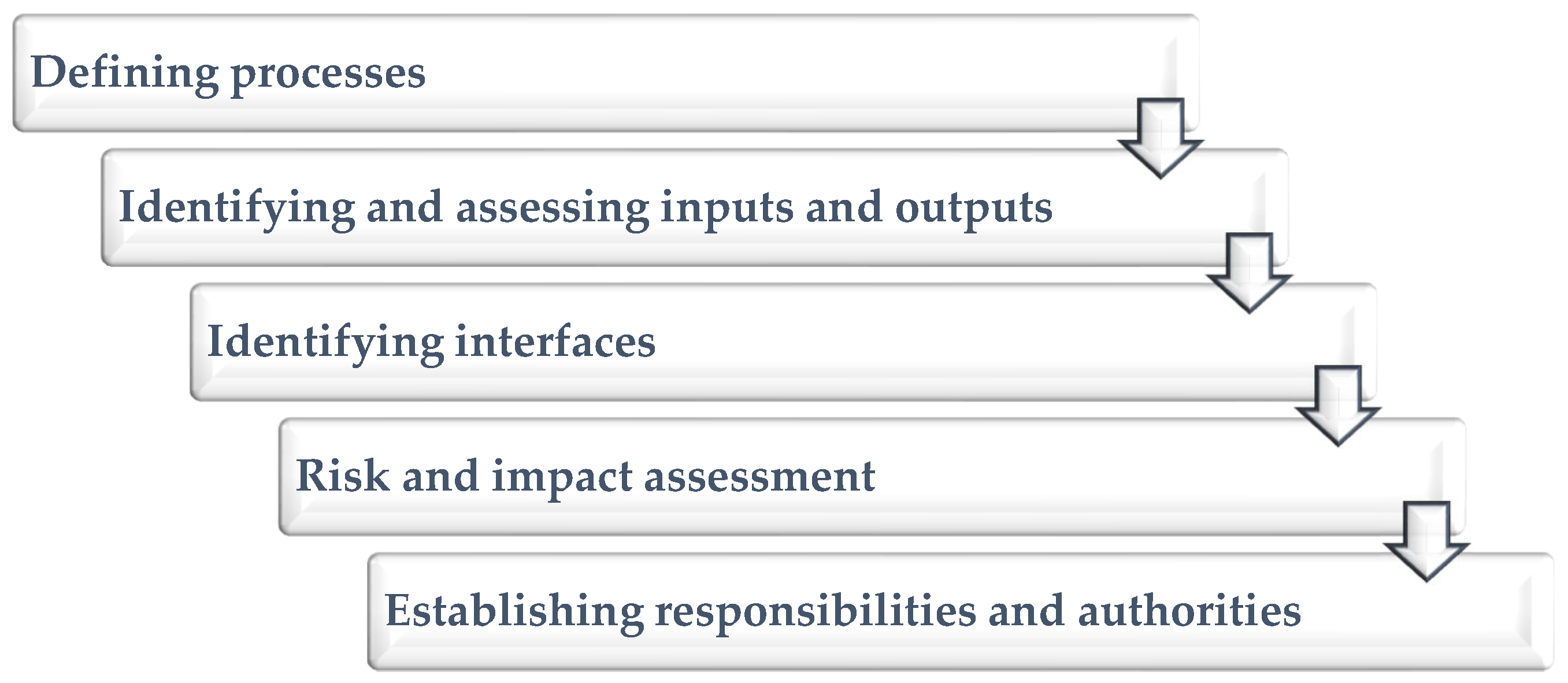

Essentially, the process-based approach involves a few key steps (

Figure 2):

Defining processes: Each process must have a clear purpose and be defined in terms of inputs, activities, outputs and responsibilities.

Identify and evaluate inputs and outputs: It is important to understand what resources and information are going into the process and what results are expected at the output.

Identify interfaces: Processes do not operate in isolation but interact with each other and with different functional entities within the organization. The identification and management of these interfaces is crucial to ensure a coherent and efficient workflow.

Risk and impact assessment: Every process involves certain risks and may have an impact on customers, suppliers and other stakeholders. Assessing these risks and the potential consequences allows appropriate preventive and corrective action to be taken.

Establish responsibilities and authorities: Each process should have a clear accountable person with the necessary authority to manage and improve the process.

Identify stakeholders: It is important to identify all those who are affected by the process or have an interest in its outcomes to ensure effective communication and collaboration.

Design the process: The design of the process should consider all relevant aspects, from the sequence of steps and activities to the resources required and the training needs of staff.

By understanding and optimizing process flow, as [

30] also points out, organizations can identify and eliminate non-value-adding activities, reduce waste, and increase operational efficiency. In addition, by carefully managing inputs and outputs, organizations can ensure that processes deliver outcomes that meet customer requirements and expectations, thereby contributing to value-added and long-term success.

2.3. Involvement of All Staff

The active involvement of employees, at all levels of the organization, is an essential pillar in the successful implementation and maintenance of an effective quality management system [

35,

36]. This principle, emphasized both in the literature and in international standards such as ISO 9001, recognizes that employees are an organization’s most valuable resource. Fully involving them, by leveraging their skills, knowledge and experience, is crucial for achieving organizational goals, including those related to quality and customer satisfaction [

36,

37,

38].

This active involvement can take various forms, from taking responsibility for solving problems and identifying opportunities for improvement, to participating in work teams and quality circles where employees can share their knowledge and experience [

36]. Such a culture of involvement and collaboration, also promoted by the Kaizen concept, stimulates creativity and innovation, contributing to the development of effective solutions and continuous improvement of processes and services [

39,

40].

Moreover, employee engagement also has a positive impact on employee satisfaction and loyalty. When they feel listened to, valued and actively involved in the organization’s decisions and activities, employees are more motivated and committed to their work [

41,

42]. This translates into an increase in productivity, an improvement in service quality and a strengthening of the organization’s image in relation to customers and society in general [

43,

44,

45,

46].

In conclusion, involving all staff is not only an ethical desideratum, but also a pragmatic strategy for achieving excellence in quality management and ensuring the long-term success of organizations, especially in the service industry, where human interaction plays a central role in the customer experience [

43,

44,

45,

46].

2.4. Continuous Improvement

Continuous improvement, or kaizen in Japanese philosophy, is a fundamental principle of quality management that transcends the automotive industry and applies to any organization that wants to constantly optimize its processes, products and services [

47,

48]. This principle, essential in the dynamic context of the contemporary market, implies a constant concern for identifying and implementing improvements, no matter how small, which, cumulated over time, can lead to significant change and superior organizational performance [

27,

47,

49].

Continuous improvement is not a static process but a dynamic cycle involving:

Setting objectives: Clearly defining what you want to improve and setting measurable targets to evaluate progress.

Planning: Identifying the root causes of the problems and developing an action plan to address them.

Implementation: Putting the action plan into practice and monitoring the results closely.

Evaluation: Analyzing the results achieved and comparing them with the objectives set initially.

Corrective action: If the results are not satisfactory, corrective action is taken to adjust the action plan and restart the improvement cycle.

To facilitate this cyclical improvement process, organizations can use a variety of specific methods and tools, such as:

A key aspect of continuous improvement is recognizing and rewarding the efforts of employees [

48]. By appreciating and valuing individual and team contributions to the improvement process, organizations can create a culture of excellence and boost staff commitment and motivation.

In conclusion, continuous improvement is a dynamic and essential process for any organization that wants to remain competitive and satisfy its customers in the long term. By taking a proactive approach and using specific methods and tools, organizations can make continuous improvements to their way of life and achieve ever higher levels of performance and quality.

2.5. Lean Manufacturing

The concept of Lean Manufacturing, inspired by the Japanese management model and described in detail by [

43], is a management philosophy that transcends the automotive industry and is successfully applied in various sectors. Essentially, Lean Manufacturing focuses on maximizing customer value by systematically eliminating any form of waste (muda) from processes [

43]. This holistic approach aims to increase operational efficiency and standardization, which leads to cost reduction, quality improvement and shorter lead times.

Lean Manufacturing is based on a few key principles and practices, including:

Identify and eliminate waste: This involves carefully analyzing all process activities and eliminating those that do not add value to the customer, such as waiting times, unnecessary transportation, excessive inventory or production defects.

Create a seamless flow: By reducing waiting times and bottlenecks, it ensures a continuous and smooth flow of materials and information through processes, leading to increased speed and efficiency.

The pull system and just-in-time (JIT) production: products and services are created or delivered only when there is a demand from the customer, which reduces inventories and associated costs.

Continuous improvement (Kaizen): the organization is constantly looking for opportunities for improvement, encouraging the involvement of all employees in this process.

Respect people: Employees are considered the organization’s most valuable resource, and their involvement and development are critical to the success of Lean Manufacturing implementation.

By applying these principles and practices, organizations can create a culture of operational excellence focused on meeting customer needs and eliminating waste. In the context of automotive services, Lean Manufacturing can help reduce customer waiting times, increase repair quality and optimize costs, leading to improved customer satisfaction and strengthening the organization’s competitive position in the market [

51,

52].

2.6. Kaizen

Kaizen, a Japanese term that translates as “continuous improvement”, is a management philosophy that promotes a proactive and participative approach to continuously optimize all aspects of organizational activity [

43]. This philosophy, deeply rooted in the Japanese organizational culture and described in detail by [

53], emphasizes the involvement of all employees, from the operational to the managerial level, in identifying and implementing small but constant improvements in work processes, products and services.

In contrast to traditional improvement approaches, which focus on radical change and major investments, Kaizen promotes the idea that significant progress can be achieved through a series of small, incremental steps that are easy to implement and low cost [

53]. This incremental approach allows organizations to improve their performance steadily without disrupting workflow or requiring significant financial resources.

Central to the Kaizen philosophy is the active involvement of all employees in the improvement process. By encouraging and rewarding individual and team initiatives, organizations can create a culture of accountability and commitment to quality and efficiency [

54]. Employees are the most knowledgeable about work processes and are therefore in the best position to identify opportunities for improvement and propose practical and effective solutions.

In the context of automotive repair services, Kaizen can be applied to improve a wide range of aspects, from shop organization and parts inventory management to customer interaction and the billing process. By implementing constant, even minor, improvements, organizations can achieve significant results in terms of increased productivity, reduced costs, improved service quality, and ultimately increased customer satisfaction [

27,

49].

In conclusion, Kaizen is a powerful and versatile management philosophy that can be successfully applied in any organization, including the automotive repair service industry. By promoting active employee involvement and continuous improvement, organizations can create a culture of excellence and achieve higher levels of performance and customer satisfaction.

2.7. Poka-Yoke

Poka-Yoke, a Japanese concept that translates as “prevention of unintentional errors”, is a proactive quality management technique aimed at eliminating or significantly reducing the possibility of defects in production or service delivery processes [

55,

56,

57].

This approach, introduced by Shigeo Shingo, is based on the creation of simple and effective mechanisms, devices or procedures to prevent human errors or detect them at an early stage, before they have a negative impact on the quality of the final product or service.

Poka-Yoke can be implemented in a variety of ways, from the use of physical devices that prevent incorrect operations from being carried out, to the implementation of verification and control procedures that flag any deviations from quality standards. In the context of car repair services, examples of the application of Poka-Yoke include:

Physical protection: The use of rubber sleeves on elevators to prevent damage to vehicle doors, fender covers, door limiters, hoods, and trunk liners

Checks and controls: the use of checklists to ensure that all required operations have been performed correctly and completely

Warning systems: the implementation of visual or audible warning systems to signal any deviation from normal operating parameters of equipment or processes.

By implementing Poka-Yoke, organizations can achieve several important benefits, including:

Increase customer satisfaction: By ensuring consistently high-quality products and services, customer confidence and satisfaction are increased.

Improve employee morale: By eliminating the frustration and stress associated with errors, employee morale and motivation are improved.

In conclusion, Poka-Yoke is a valuable quality management technique that can be successfully applied in the automotive repair service industry to prevent errors, reduce costs and increase customer satisfaction [

58,

59].

By adopting a proactive approach and implementing simple and effective mechanisms and procedures, organizations can ensure a higher quality of service and strengthen their position in the market.

FMEA (Failure Mode and Effects Analysis) is a systematic methodology used to identify, analyze, and prioritize the potential failure modes of a process or product, as well as their effects. It is a proactive tool that helps organizations prevent errors before they occur. In the automotive industry, FMEA is mandatory under the IATF 16949 standard [

60] and is a key component of advanced product quality planning (APQP).

There are two main approaches to prioritizing identified risks:

- 1.

Risk Priority Number (RPN): This is the traditional approach that has been used for a long time. It is calculated as the product of three scores:

Severity (S): The seriousness of the defect’s effect.

Occurrence (O): The probability of the defect occurring.

Detection (D): The ability of the current system to detect the defect before it reaches the customer.

RPN = S × O × D.

- 2.

Action Priority (AP): This is a more recent approach, preferred in newer editions of the FMEA manual, which prioritizes risks based on the necessary actions and a logical analysis of Severity, Occurrence, and Detection, rather than a simple number. Unlike RPN, which can sometimes be misleading (two risks with the same RPN can have very different risk profiles), the AP approach provides a clear priority: High, Medium, or Low, based on a decision table.

Regarding the differences between Japan and Europe, while both use FMEA, implementation can reflect cultural differences: the Japanese approach, centered on Gemba (the actual place where the action happens) and the involvement of workers at the operational level, often integrates FMEA directly into Kaizen teams, seeking simple, visual, and immediate solutions (Poka-Yoke) to reduce Occurrence (O) and Detection (D) scores. The European (and American) approach has historically been more formal, based on multidisciplinary expert teams and extensive documentation, with a more frequent use of the RPN calculation. However, current trends, including in IATF 16949, encourage a more fluid integration of risk analysis tools like FMEA with practical approaches such as Poka-Yoke. In fact, Poka-Yoke is considered a measure to reduce the Occurrence or Detection score within an FMEA analysis.

2.8. Visual Management

Visual management is an essential approach in organizations that want to optimize their processes and improve their performance, as highlighted in the literature [

61,

62,

63]. This technique is based on the use of visual indicators, such as charts, graphs, dashboards, or light signals (such as the Andon system), to communicate important information about process performance, work objectives, quality standards, and other aspects relevant to the organization’s work [

64].

By presenting information in a clear, concise and easy to understand way, visual management facilitates communication and transparency within the organization, allowing all employees to quickly and easily understand the current state of processes and to identify potential problems or opportunities for improvement. This approach helps to increase employees’ awareness and accountability, encouraging them to become actively involved in problem solving and continuous process improvement [

62].

In the context of automotive repair services, visual management can be used to monitor and control a wide range of aspects, from job scheduling and resource allocation, to tracking completion deadlines and managing spare parts inventories.

In conclusion, visual management is a valuable tool for organizations looking to improve their performance and optimize their processes [

57]. By implementing this technique and creating an organizational culture based on transparency, involvement and continuous improvement, organizations providing automotive repair services can achieve higher levels of quality, efficiency and customer satisfaction.

2.9. The IATF 16949 Standard: A European and Japanese Convergence

The IATF 16949 standard, developed by the International Automotive Task Force, a group of automotive manufacturers and trade associations, is essential for ensuring quality in the global automotive supply chain. While it has roots in Western standards like ISO 9001, IATF 16949 incorporates fundamental principles from Japanese management philosophy, particularly from the Toyota Production System (TPS).

The main differences are often cultural and related to implementation. While IATF 16949 mandates a rigorous, standardized, and documented evidence-based framework, the Japanese approach, although compliant, tends to focus more on aspects like Kaizen (continuous improvement), Jidoka (automation with a human touch to prevent defects), and the full involvement of employees in the quality process. The standard itself is a point of convergence, promoting a unified approach to quality globally, but the implementation philosophy can vary. For example, a Japanese organization might view adherence to the standard to facilitate Kaizen improvements, while a European organization might see compliance as an end in itself—a contractual requirement to enter the market.

2.10. The Integrated Quality Management Framework

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the integrated quality management framework, proposed and validated by this research. The model illustrates the synergy between theoretical foundations, European management approaches, and Japanese operational philosophies, demonstrating how the integration of these elements, supported by visual management and employee involvement, leads to measurable results and long-term sustainability in the automotive service sector.

3. Research Methodology

The present study adopts a mixed-methods, pre-and-post-implementation, case-based study without a control group to investigate the effects of implementing integrated quality management tools in two Romanian automotive repair organizations. The two automotive centers (A and B) served as the study entities, each focusing on implementing specific tools (visual management in Center A and Lean cells in Center B). This approach allows for an internal comparative analysis. This methodological approach enables both quantitative performance evaluation and qualitative process observation, contributing to the empirical validation of a hybrid quality model grounded in European and Japanese principles.

The research was conducted over a 6-month operational period (January–June 2024), during which both service centers initiated a structured implementation of process monitoring tools and continuous improvement techniques. The organizations selected were medium-sized authorized repair workshops affiliated with multinational vehicle brands, located in urban areas and employing between 25 and 40 technicians. These centers were chosen based on three selection criteria:

- -

active commitment to quality initiatives;

- -

process documentation maturity (ISO 9001 certified);

- -

willingness to integrate Kaizen and Lean tools.

Data was collected through the following sources and instruments:

- -

Direct participatory observation of work processes and technician behaviors;

- -

Structured interviews with department heads and quality managers (n = 8);

- -

Internal performance logs extracted weekly, including metrics such as rework rate, technician efficiency, order completion time, customer complaints, and internal nonconformities;

- -

Customer satisfaction feedback, processed using Net Promoter Score (NPS);

- -

Visual management audit checklists completed biweekly;

- -

Correlation analysis using Pearson’s r to test relationships between applied tools and performance indicators (threshold of p < 0.05 for significance).

To ensure transparency and replicability, the collected dataset was anonymized and is summarized in

Table 1, including six weeks of comparative data (pre- and post-implementation). Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel.

The following performance indicators (KPIs) were monitored:

- -

Technician Efficiency (%), calculated as: (Total Invoiced Hours/Total Present Hours) × 100%. Data was extracted weekly from the internal Dealer Management System (DMS).

- -

Rework Rate (%), calculated as: (Number of customer returns for the same defect within 30 days/Total number of repairs completed) × 100%. Data was sourced from post-service customer feedback logs.

- -

Service Throughput Time (days), calculated as: (Vehicle Handover Date—Vehicle Intake Date) in days. Data was logged from work orders in the DMS.

- -

NPS (Net Promoter Score), calculated from customer surveys using the standard NPS formula: % Promoters (score 9–10)—% Detractors (score 0–6). Surveys were sent via SMS or email post-service.

- -

Internal Nonconformities (procedural deviations per week).

- -

Visual Management Compliance Rate (% execution of visual standards).

The methodology was developed in accordance with principles of applied service operations management, aligning data collection and analysis with the practical realities of automotive repair workflows. In addition, the methodological framework reflects the intent of SDG 9 (Innovation and Infrastructure) and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) by capturing the systemic effects of process efficiency, error reduction, and resource use in service environments.

Through this approach, the study ensures methodological rigor while maintaining practical applicability. The triangulation of data from multiple sources (quantitative and qualitative) strengthens the validity of findings and supports the generalizability of the results to similar automotive service contexts, particularly in SMEs engaged in quality transformation.

To explore the practical applicability and effectiveness of integrated quality management principles in real-world conditions, the study was conducted across two medium-sized automotive repair organizations in Romania, referred to here as Service Center A and Service Center B. Both centers operate independently, serve similar customer volumes (between 30 and 50 vehicles per day), and follow standard operational procedures aligned with ISO 9001. However, each was selected based on its willingness to participate in structured process improvement interventions and allow continuous performance monitoring.

Service Center A focused primarily on implementing visual management systems and standard work procedures, particularly in diagnostic and final inspection phases. This center provided a suitable environment for evaluating the operationalization of visual controls, checklists, and technician-led quality initiatives through Quality Circles.

Service Center B served as the primary context for the deployment of Lean Manufacturing and work cell restructuring. The facility underwent a targeted reorganization based on value-stream mapping, enabling direct observation of efficiency gains and waste reduction. Both service centers contributed empirical data over a six-month period, which formed the basis of the performance analyses presented in the following sections.

The choice of these two sites allows the comparison of results across different implementation strategies and highlights the contextual factors influencing the effectiveness of Kaizen, Lean, and Poka-Yoke methodologies in service environments.

A key limitation of this study is the absence of a control group. While the pre-and-post-implementation case study approach allowed for a robust empirical evaluation of the results, the lack of a control group makes it difficult to precisely separate the impact of our interventions from other external factors. Therefore, while the established correlations are statistically significant, they demonstrate a strong relationship between the implementation of the tools and the improvement of the indicators, but they cannot establish absolute causality, as other uncontrolled variables may influence performance.

4. Research Presentation

4.1. Integration of Process Monitoring Systems

Integrating process monitoring systems is a complex and multidimensional challenge for modern organizations. This integration is not limited to the technological implementation of systems, but also involves a profound change in organizational culture, work processes and the way employees interact and collaborate.

The monitoring initiative focused on four core service processes:

- -

initial diagnostics and client intake,

- -

mechanical repair intervention,

- -

final quality control, and

- -

vehicle handover.

Within these, task standardization, time recording, and nonconformity tracking were introduced progressively.

Specific tools were assigned by process area:

- -

Kaizen was applied in the diagnostics and quality control phases, using weekly improvement meetings and technician-led suggestion systems.

- -

Poka-Yoke was introduced during final checks through structured checklist validation and error-prevention tags (e.g., torque-marking, fluid cap indicators).

- -

Lean principles guided the redesign of task flows using value-stream mapping and workstation reconfiguration (e.g., U-shaped layout in mechanical zones).

- -

Visual management practices included kanban-style progress boards, color-coded workspaces, and visual SOPs displayed at point of use.

Process monitoring was conducted in real time by quality coordinators, with data being uploaded weekly to internal dashboards. The system was synchronized with ISO 9001 workflows but extended beyond compliance to include root-cause tracking, non-value-added time recording, and team-based improvement logs. These additions operationalized the PDCA cycle (Plan–Do–Check–Act) at the level of work cells. The data collected served as the foundation for correlation analyses and performance comparisons described in

Section 5.

Organizations that have successfully implemented a quality management system and developed a strong organizational culture based on values such as continuous improvement, customer orientation and individual accountability have a significant advantage in the process. These organizations already have in place a structure and set of practices that facilitate the integration of monitoring systems, enabling them to optimize their processes, improve the quality of their products and services, and increase their operational efficiency.

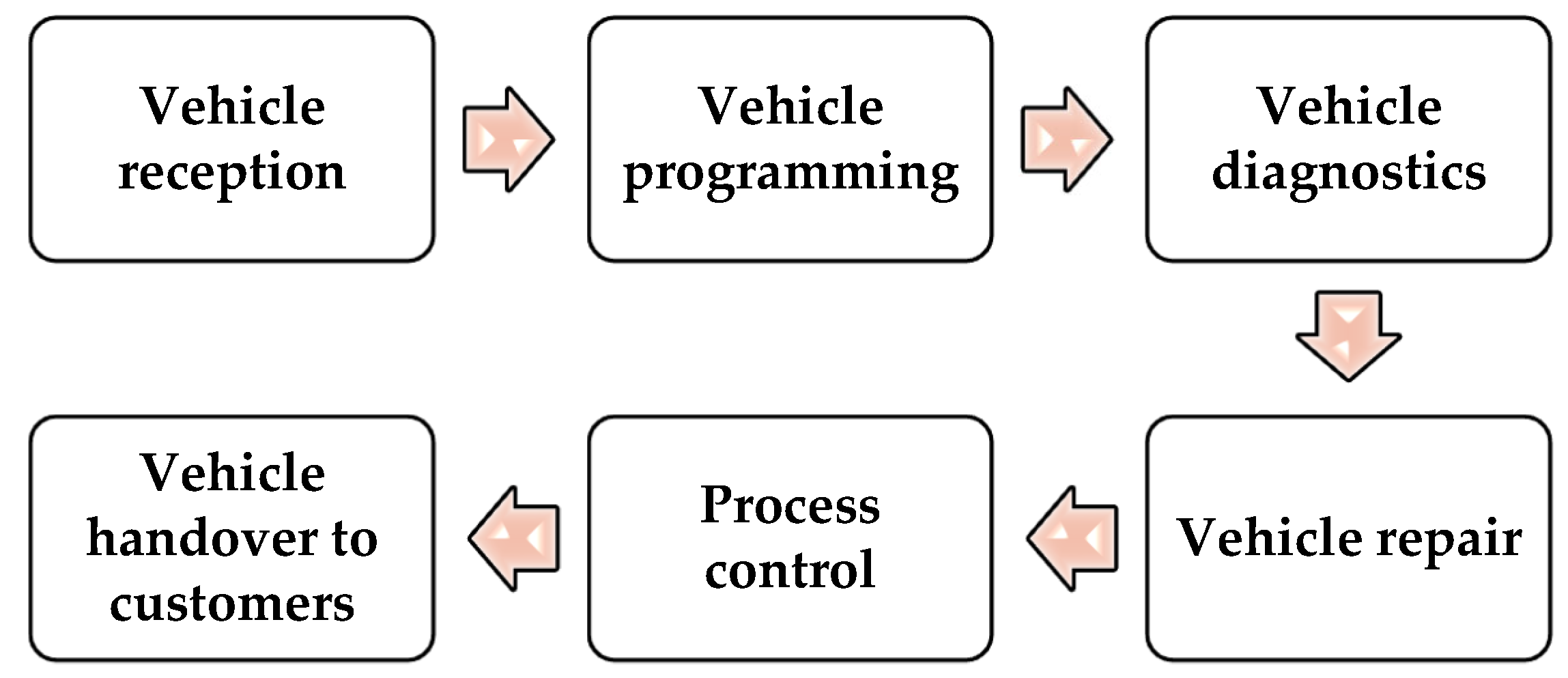

Figure 4 shows a visual representation of the main flow of activities involved in an automotive service process. This diagram outlines the key stages that a vehicle goes through in a car service, from receipt to handover to the customer.

Steps in the Service Process:

Vehicle Reception: This is the first stage of the process, where the customer brings the vehicle in for servicing and presents their requests or problems.

Vehicle Scheduling: At this stage, a schedule for service work is established, considering the availability of technicians and equipment.

Vehicle Diagnostics: This stage involves identifying and assessing the technical problems of the vehicle, using various diagnostic methods and tools.

Vehicle repair: At this stage, specialist technicians carry out the necessary repair work to solve the problems identified in the diagnostic stage.

Process control: This stage involves checking the quality of the work carried out and ensuring that it meets technical standards and specifications.

Handing over the vehicles to the customer: This is the final stage of the process, where the customer takes back the repaired vehicle and receives information about the work carried out and any recommendations for further maintenance.

This figure provides an overview of the car service process, highlighting the interdependence between the different steps and the importance of a systematic and integrated approach. By understanding this workflow, automotive service organizations can identify opportunities to improve processes, increase efficiency and ensure customer satisfaction.

Other comments follow:

Quality measurement, monitoring and control are fundamental elements of any quality management system. These processes enable organizations to objectively assess their performance, identify areas for improvement and take corrective action to ensure that products and services meet customer requirements and expectations.

The importance of measurement and monitoring:

Ensuring customer satisfaction: By measuring and monitoring performance, organizations can identify and correct potential non-conformances before they reach customers, thereby ensuring customer satisfaction

Continuous improvement: Measurement and monitoring enable organizations to identify opportunities to improve their processes and products, thereby contributing to a steady increase in performance

Informed decision-making: Data collected through measurement and monitoring provides management with valuable information for strategic and operational decision-making.

Measurement, monitoring and quality control processes can include a variety of methods and tools, such as:

Statistical analysis: these allow the analysis of collected data to identify trends, variations and potential causes of non-conformities

Simulations: these allow the testing and optimization of processes prior to their implementation, thus reducing the risk of errors and non-conformities

Internal and external audits: These allow the assessment of the compliance of processes and products with applicable standards and requirements

Measuring and monitoring devices: These allow the collection of data on process and product performance.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the data collected, it is essential that the measuring and monitoring devices are regularly checked and validated. This involves:

Confirming that devices are suitable for use: Devices must be selected and used in accordance with applicable specifications and requirements

Maintaining proper accuracy: Devices must be calibrated and serviced regularly to ensure that they operate within specified parameters

Identifying the status of devices: Devices must be clearly labeled or marked to indicate their status (e.g., calibrated, in service, etc.).

The implemented system also aligns with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 9 and 12. By reducing rework rates, optimizing technician task allocation, and minimizing unnecessary resource consumption, the monitoring approach supports both innovation in industry infrastructure and responsible consumption practices. These outcomes directly contribute to improved environmental and operational sustainability in line with the European Green Deal and global SDG frameworks.

4.2. Quality Circles and Kaizen Teams

Kaizen, a Japanese term meaning “continuous improvement”, is a management philosophy that emphasizes the involvement of all employees in the process of improving the organization’s performance. This philosophy is based on the idea that every employee, regardless of his or her position in the organization, can contribute to identifying and implementing small but constant improvements that, over time, can lead to significant change and an increase in the organization’s competitiveness.

Within the studied automotive centers, Kaizen was applied using weekly quality circle sessions in diagnostic and final verification departments. Participants were technicians and team leaders, whose suggestions and process observations were logged and categorized by theme. Over 40 such proposals were submitted during the observation period, of which 65% were accepted for pilot testing. Metrics used to evaluate impact included mean diagnostic time, number of checklist deviations, and rework instances.

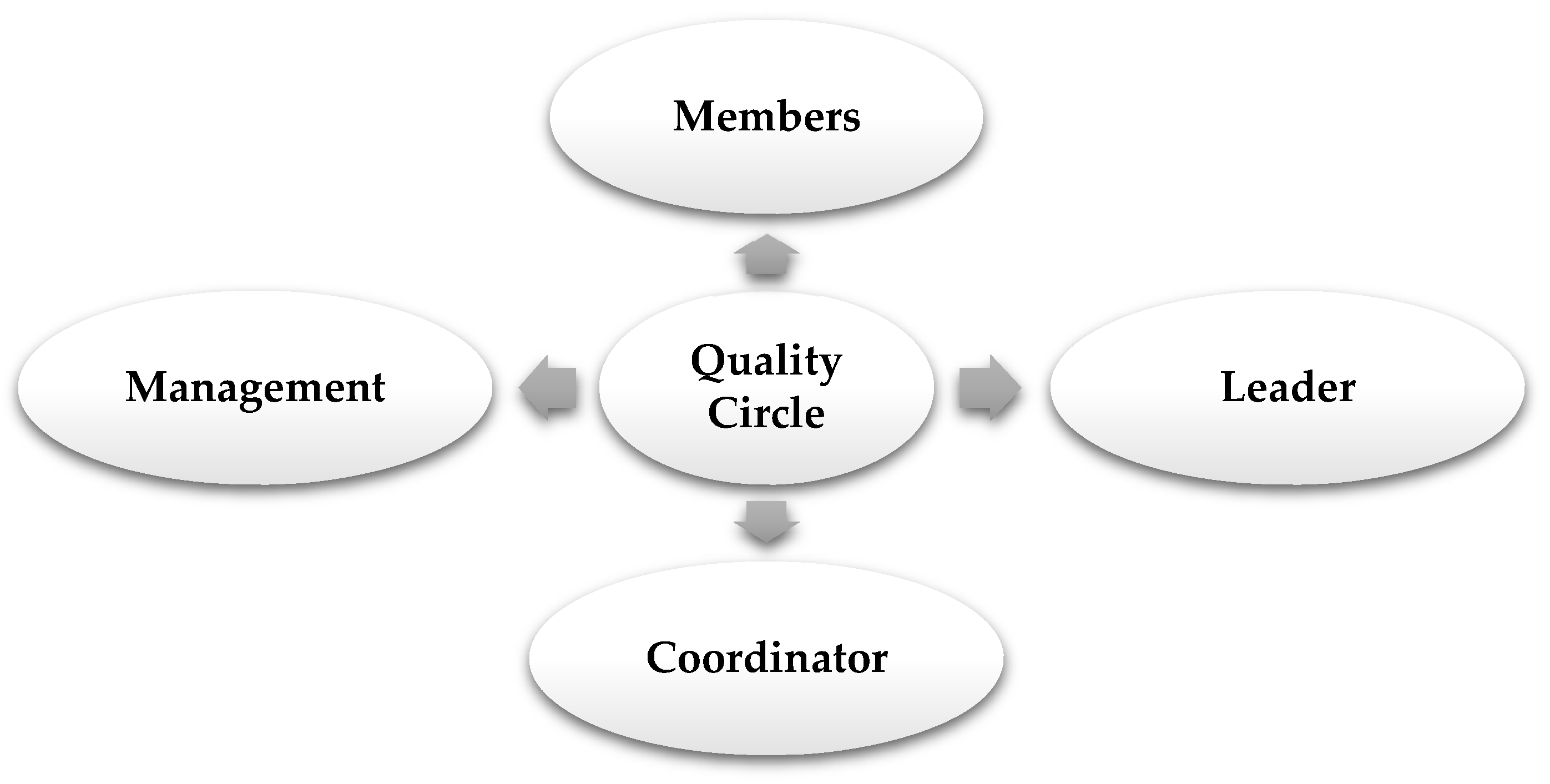

Quality circles are an important tool in implementing the Kaizen philosophy. They are small groups of employees, usually from the same department or work area, who meet voluntarily and regularly to identify, analyze and solve problems related to their work. Quality circles are led by a leader, who may be a supervisor or an experienced colleague, and are supported by the organization’s management.

Figure 5 shows the components and interactions in a quality circle, highlighting the key roles and associated responsibilities.

The components of the Quality Circle are:

Members: These are the employees who voluntarily join the circle and are directly involved in the activities of identifying, analyzing and solving problems.

Leader: The leader is usually the members’ direct superior or an experienced foreman. The role of the leader is to guide and coordinate the activities of the circle, ensuring effective communication and a productive working environment.

The coordinator: The coordinator is responsible for managing the quality circle program throughout the organization. The coordinator provides the necessary support to the leaders and members, facilitates communication between the Circles and the rest of the organization, and promotes a culture of continuous improvement.

Management: Represents the leadership of the organization, which plays a key role in ensuring the success of the Quality Circles by providing support, resources and recognition for their efforts and achievements.

Interactions and Responsibilities:

Members—The Leader: Circle members interact directly with the leader, presenting identified problems, participating in discussions and proposing solutions. The leader, in turn, provides guidance, facilitates communication and ensures that the activities of the Circle are carried out in an efficient and effective manner.

The Leader—The Coordinator: The leader reports to the coordinator on the progress of the Circle, the problems encountered, and the solutions proposed. The coordinator provides support and guidance to the leader, facilitates access to resources and ensures communication with the management of the organization.

Coordinator—Management: The coordinator presents to the management the results of the quality circle activities, proposals for improvement and requests support and resources for their implementation. Management, in turn, evaluates the proposals, allocates the necessary resources and provides feedback and recognition for the efforts made.

This figure illustrates the structure and dynamics of a quality circle, emphasizing the importance of collaboration and effective communication between the different roles involved. It also highlights the crucial role of management in ensuring the success of quality circles by providing support, resources and recognition.

Figure 5 provides valuable insight into how quality circles work and the key factors that contribute to their success. By understanding and applying these principles, organizations can harness the potential of their employees and create a culture of continuous improvement that enables them to achieve their goals and enhance their competitiveness.

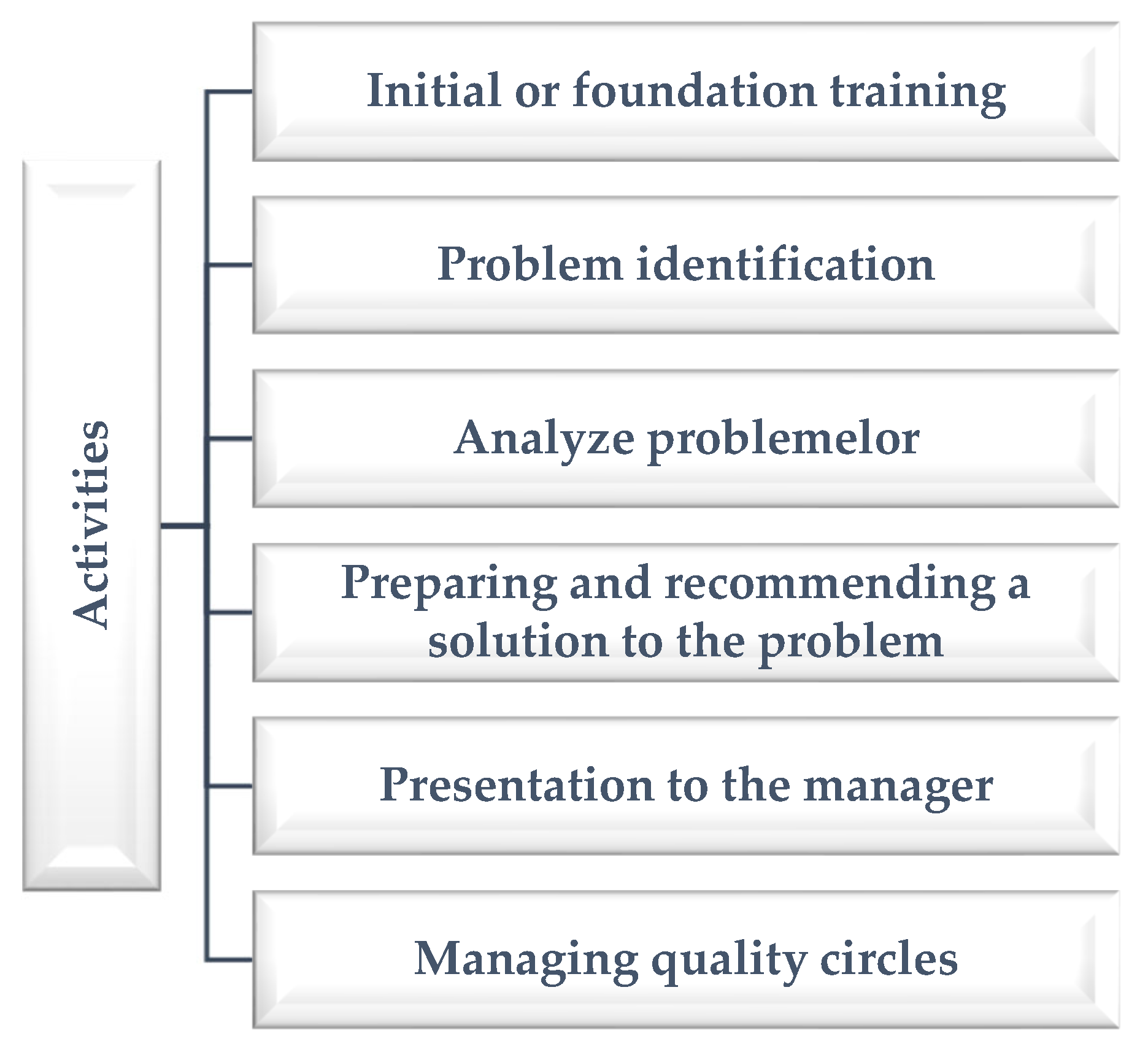

Figure 6 shows a comprehensive list of activities that may take place during a Quality Circle meeting. These activities are essential for the effective functioning of the Quality Circle and the achievement of its continuous improvement objectives.

Quality Circle activities include:

Brainstorming: This brainstorming technique encourages members to freely express their thoughts and suggestions without being judged or criticized. Brainstorming can be used to identify problems, generate potential solutions or explore new opportunities for improvement.

Pareto analysis: This statistical method allows problems to be identified and prioritized according to their impact on performance. By focusing efforts on the most important issues, the quality circle can achieve significant results with limited resources.

Ishikawa Diagrams: Also known as cause-and-effect or fishbone diagrams, these are used to identify and analyze the root causes of a problem. By visually representing the relationships between causes and effects, Ishikawa diagrams make it easier to understand the complexity of the problem and identify appropriate solutions.

Histograms: These graphs allow visualization of the distribution of a quality characteristic, highlighting central trends and variation in the data. Histograms can be used to assess the stability of a process, identify areas for improvement, and monitor the effectiveness of corrective measures implemented.

Control charts: These statistical tools make it possible to monitor the variation of a process over time, identify causes of variation, and take corrective action to keep the process under control. Control charts are essential for ensuring process stability and preventing the occurrence of non-conformities.

Flow diagrams: These diagrams graphically represent the steps in a process, allowing you to visualize the workflow and identify potential bottlenecks or inefficiencies. Flowcharts are useful for understanding and optimizing processes as well as for communicating and documenting them.

Scatter diagrams: These graphs allow you to analyze the relationship between two variables, identifying possible correlations or dependencies. Scatter diagrams can be used to better understand the factors that influence the performance of a process or product.

Stratification: This technique involves dividing the data into homogeneous groups to facilitate analysis and identify causes of variation. Stratification can be used in combination with other tools, such as Pareto charts or histograms, to gain a deeper understanding of problems and potential solutions.

Questionnaires: These can be used to collect information and opinions from customers, employees or other stakeholders, thus providing valuable insight into the organization’s performance and opportunities for improvement.

Benchmarking: This technique involves comparing the organization’s performance with that of other similar organizations to identify best practices and set ambitious improvement targets. Benchmarking can be a powerful tool for driving innovation and performance growth.

Figure 6 highlights the diversity of activities that can take place within a quality circle, emphasizing the importance of using a variety of tools and techniques to address problems and identify effective solutions. It also emphasizes the active role of the circle members in the continuous improvement process and the importance of collaboration and open communication.

Figure 6 gives an overview of how Quality Circles operate and the tools and techniques they use to achieve their objectives. By understanding and applying these methods, organizations can create a work environment in which employees are encouraged and supported to take responsibility for continuous process and quality improvement, thereby contributing to the long-term success of the organization.

The benefits of Quality Circles are:

Improving the quality of products and services: By identifying and solving problems in the workplace, Quality Circles help to improve the quality of products and services offered by the organization.

Increasing productivity: By optimizing work processes and eliminating waste, Quality Circles can help to increase productivity.

Motivating and involving employees: Participation in Quality Circles gives employees the opportunity to develop their skills, take responsibility and contribute to the success of the organization, which can lead to increased motivation and involvement.

4.3. Lean Manufacturing in Automotive Services

In Service Center B, Lean implementation began with a full value-stream mapping of the mechanical repair process. Wasted motion, excessive inventory, and wait times were identified. Based on this, technicians were reorganized into Lean cells around service types (e.g., suspension, brake systems, diagnostics), and standard work charts were introduced. The intervention was monitored using lead time per service order and technician productivity, which are discussed in

Section 5.

The Lean Manufacturing concept, although it has its origins in the manufacturing industry, can be successfully adapted and implemented in automotive service to improve efficiency, quality and customer satisfaction.

In practice, this means:

Eliminate waste: Identify and eliminate any activities that do not add value to the customer, such as waiting time, searching for tools or parts, repeated repairs due to initial errors, or unnecessary technician travel.

Optimize workflow: Efficiently organize the shop floor, parts inventory and scheduling to ensure a continuous and uninterrupted flow of work, thereby reducing waiting times and increasing productivity.

Just-in-time parts delivery: Implement a supply system to ensure that the required spare parts are available exactly when needed, thereby avoiding excessive inventories and related costs.

Continuous improvement (Kaizen): Encouraging all employees to identify and propose improvements in work processes by implementing suggestions and ideas that can lead to increased efficiency and quality of service.

Customer focus: Understanding and meeting customer needs and expectations by providing quality services at competitive prices and in the shortest possible time.

Employee development: Investing in the continuous training and development of staff to equip them with the skills and knowledge needed to provide high quality services and to adapt to technological and market changes.

Simplify and standardize processes: Eliminate unnecessary bureaucracy and complexity in work processes by establishing clear and easy-to-follow procedures to ensure consistency and quality of service. 8. Promote teamwork: Encourage collaboration and effective communication between different departments and employees to ensure optimal workflow and rapid problem solving.

By applying these principles and practices, automotive services can create an organizational culture focused on efficiency, quality and customer satisfaction. This will lead not only to increased profitability, but also to enhanced reputation and customer loyalty, thus ensuring long-term business success.

4.4. Andon: Visual and Auditory Signage for Efficiency and Quality

The Andon system, an essential tool in visual management, uses light and sound signals to quickly and effectively communicate process status information and alert staff to problems or anomalies.

In car servicing, the Andon system can be deployed for:

Reporting problems to the service line: A red light may indicate a major equipment malfunction or a critical problem in the repair process, requiring immediate intervention.

Stock level monitoring: A yellow light may indicate that the stock of a particular spare part is low and requires restocking.

Workflow management: A green light can indicate that a particular workstation is free and available to take a new order.

By using Andon, it facilitates fast and efficient communication between employees and ensures a prompt reaction in case of problems, leading to reduced downtime, increased productivity and improved quality of service.

Advantages of using Andon in car servicing include:

Rapid problem detection and resolution: by signaling problems immediately, delays are avoided and the negative impact on customers is reduced.

Improved communication and collaboration: employees are informed in real time about the status of processes and can intervene quickly to provide support or resolve problems.

Increased employee accountability and involvement: Each employee is responsible for monitoring and reporting issues at their workstation, leading to increased accountability and involvement.

Error and accident prevention: By signaling potentially dangerous situations, Andon helps prevent workplace accidents and increase workplace safety.

The integration of Andon into the visual management of car service centers is an effective and easy to implement solution to improve communication, increase efficiency and ensure a higher quality of customer service.

4.5. Poka-Yoke in Car Service: Error Prevention for Service Excellence

The Japanese concept of Poka-Yoke, or “prevention of unintentional errors”, focuses on eliminating the possibility of defects by implementing simple and effective solutions at the design stage of processes or products.

Practical applications in car servicing:

Physical protection: The use of barriers, covers or restrictors to prevent accidental damage to vehicles during servicing.

Checklists: Implement detailed checklists for each stage of the repair process, ensuring that all operations are carried out correctly and completely.

Color codes and labels: Use color codes or labels to identify parts, tools and equipment, thereby avoiding confusion and assembly errors.

Sensors and alarms: Install sensors and alarms to alert technicians of anomalies or exceedances of operating parameters during repairs.

Benefits of Poka-Yoke in car servicing:

Reduction of errors and repeat repairs: By preventing human error, the number of non-conformities is reduced, thus reducing the need for subsequent repairs, saving time and resources.

Improvement of service quality: Eliminating errors leads to an increase in the quality and reliability of the services provided, resulting in higher customer satisfaction.

Increased efficiency and productivity: By standardizing processes and eliminating time lost due to errors, workflow is optimized, and productivity is increased.

Improved workplace safety: Preventing errors can also help reduce the risk of accidents and increase employee safety.

Implementing Poka-Yoke requires:

Detailed process analysis: Identify critical points where errors may occur and assess the associated risks.

Creativity and employee involvement: Employees who work directly in the processes are best able to identify potential errors and propose practical preventive solutions.

Continuous monitoring and improvement: Poka-Yoke solutions must be constantly monitored and improved to ensure that they remain effective and relevant in the context of technological and process changes.

By adopting a proactive approach and implementing simple and effective solutions, automotive services can prevent errors from occurring, reduce costs and increase customer satisfaction, thus ensuring a long-term competitive advantage.

Table 2 presents a practical application of the Poka-Yoke concept in automotive services in the form of a detailed worksheet for monitoring the work required to prepare vehicles for delivery. This worksheet standardizes the final check process, ensuring that all important aspects are considered before the car is handed over to the customer.

The table below summarizes the main check categories and the number of associated operations in the monitoring worksheet, providing an insight into how Poka-Yoke is implemented to prevent errors and ensure service quality:

This detailed check sheet acts as a Poka-Yoke mechanism by:

Standardization: Defines a clear set of operations to be performed, eliminating ambiguity and ensuring consistency.

Prevention of errors of omission: By explicitly listing each check, it reduces the risk of technicians skipping important steps.

Facilitation of problem detection: Provides a structured framework for inspection, increasing the likelihood of identifying any non-conformity before the machine is delivered.

Therefore,

Table 2 illustrates how a simple but effective tool can be used to implement the Poka-Yoke concept in car servicing, contributing to higher quality of service and customer satisfaction.

4.6. Jidoka: Automation with Human Intelligence in Car Service

Jidoka, a complementary Poka-Yoke concept, takes error prevention to the next level by automating the detection and stopping of processes in the event of anomalies. In automotive services, Jidoka can be implemented by:

Sensors and automation: use sensors to monitor critical vehicle parameters during repairs (oil pressure, engine temperature, etc.) and automatically stop the process in case of non-conforming values.

Intelligent diagnostic systems: using computerized diagnostic systems to automatically identify faults and give clear instructions to technicians to fix them.

Equipment with self-checking functions: Use of service equipment with self-checking and self-calibrating functions to signal any faults or maintenance needs.

Benefits of Jidoka in car servicing:

Superior quality of repairs: By automatically detecting and correcting errors, a consistently high quality of work is ensured.

Reduced downtime: automatic shutdown of processes in the event of anomalies allows rapid intervention and reduces downtime, increasing productivity.

Efficient use of human resources: Technicians can be assigned to higher value-added tasks, while the Jidoka system takes care of automated process monitoring and control.

Improving safety: Automatic anomaly detection can prevent workplace accidents and protect both employees and equipment.

Implementing Jidoka requires:

Investment in technology: Purchase and installation of sensors, diagnostic systems and self-checking equipment.

Staff training: familiarize employees with new technologies and procedures so that they can intervene effectively in case of problems.

Data analysis and continuous improvement: Collect and analyze data generated by the Jidoka system to identify process improvement opportunities and prevent similar problems from occurring in the future.

By integrating Jidoka into automotive service centers, a significant increase in quality, efficiency and safety can be achieved, transforming repair processes into an intelligent and self-regulating system capable of delivering high quality customer service.

In addition, the implementation of Jidoka can help reduce unnecessary costs by eliminating non-value-adding activities and optimizing the use of resources. Thus, it can maximize the value added to each job and increase the profitability of the organization.

4.7. Visual Workplace Management: A Key to Efficiency and Engagement

Visual management at the workstation is an essential strategy for optimizing operations in an automotive service. This approach involves the use of visual cues, such as diagrams, labels, markings and posters, to convey essential information in a clear and easy-to-understand way.

The implementation of visual management in car servicing can include:

Accessible documentation: Display work instructions, safety procedures and other relevant documents in a clear and organized way, within easy reach of technicians, to eliminate time wasted searching and reduce errors.

Visible Performance Indicators: Display work objectives, progress and KPIs to drive employee engagement and accountability.

Efficient workspace organization: Use markings and labels to demarcate work areas, identify tool and parts storage locations, and ensure optimal workflow.

Visual inventory management: Implement Kanban or other visual methods to monitor stock levels and signal the need for replenishment.

Process Standardization: Using visual diagrams and instructions to standardize work processes and ensure that all technicians follow the same procedures, thus reducing variability and errors.

5S Implementation: Applying 5S principles (sorting, systematizing, cleaning, standardizing, disciplining) to create an organized, clean and efficient work environment.

The benefits of visual management in car servicing:

Improved communication: Information is passed quickly and efficiently, reducing misunderstandings and miscommunication.

Increased productivity: By eliminating wasted time and optimizing workflow, productivity and efficiency of operations can be increased.

Improved quality: Standardizing processes and visually monitoring them helps reduce errors and increase the quality of service.

Increased employee engagement and accountability: Employees feel more engaged and accountable when they have access to clear information and can see the impact of their work on overall performance.

Creating a safer working environment: By visually signaling hazardous areas or safety procedures, the risk of accidents can be reduced.

Visual management is an effective and easy-to-implement strategy that can bring significant benefits to automotive service organizations. By creating a transparent, organized and performance-oriented working environment, this approach can help to increase customer satisfaction, improve operational efficiency and strengthen the service’s competitive position in the market.

In both service centers, visual workplace methods were audited bi-weekly using a 5S compliance checklist and incident tracking sheets. Performance indicators such as tool retrieval time, missing part reporting, and workstation readiness were measured, offering quantifiable insight into visual management effectiveness. The results of these metrics are presented in

Table 2 and analyzed in

Section 5.

4.8. Aligning Quality Management Tools with Sustainable Development Goals

This section analyzes and visually illustrates how quality management tools, rooted in Japanese principles, directly contribute to the achievement of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 9—Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure and SDG 12—Responsible Consumption and Production.

Table 3 details the specific correlation between tools such as Kaizen, Lean Manufacturing, Poka-Yoke, and Visual Management and their impact on operational sustainability within automotive service organizations. This approach demonstrates that process improvements are not an end in themselves, but also serve broader strategic objectives related to social and environmental responsibility.

5. Research Results

To achieve positive results from the implementation of changes necessary for organizational development, the manager who initiates the change must have the support of the members of the organization, especially the managers at subordinate levels.

Table 4 shows some specific action steps differentiated according to the process initiated. If the manager is confronted with lack of trust in the organization, low concern for quality issues, low customer focus and a tendency to create a public image of the organization, the change should initially focus on organizational culture, core beliefs and values rather than on systems.

Each department manager should be responsible for achieving the assigned objectives. Given the complexity of the activities carried out in the car repair service provider organization, to enable each manager to effectively monitor the performance level of his/her department in real time, a few indicators relevant to the work of each department have been established.

To manage the performance level of the service activity, the following indicators need to be monitored:

Productivity: This is calculated as the ratio between the number of hours worked and the total number of working hours available in a month. The recommended value is a minimum of 85%. This indicator may not exceed 100%, as service technicians cannot work more hours than they are present at work

Efficiency: This indicator measures the ability of technicians to carry out repairs within the standard times set by the manufacturers. Efficiency is calculated as the ratio of the total number of hours sold (invoiced) to the total number of hours worked by directly productive staff. The value of this indicator shall be at least 100%.

Table 4 shows a comparison between two types of organizational change processes: system change and organizational culture change.

Each process has different characteristics and approaches, and understanding these differences is crucial for managers who want to successfully implement change in their organization:

Orientation: System change focuses on solving specific problems and improving operational efficiency, while organizational culture change aims at transforming employees’ core values and perceptions, which can lead to deeper and more sustainable change.

Approach: System change can be implemented gradually and controlled, whereas organizational culture change is a more extensive and difficult to control process once it has started.

Change: System change focuses on modifying existing processes and procedures, while organizational culture change involves a transformation of employees’ mindsets and behaviors.

Focus: System change focuses on establishing and monitoring performance indicators to measure and improve results, while organizational culture change focuses on creating a positive work environment and improving the quality of life in the organization.

Diagnosis: In the case of system change, diagnosis focuses on identifying inconsistencies and dysfunctions within existing systems. In contrast, diagnosis for organizational culture change involves a deeper analysis of employee perceptions and values to identify barriers to change and develop appropriate strategies.

Leadership: System change can be achieved without major changes in leadership style, while changing organizational culture often requires a fundamental transformation of leadership to promote and sustain the desired new values and behaviors.

In conclusion,

Table 4 provides valuable insight into the differences between the system change process and the organizational culture change process. Choosing the right approach depends on the specific context of the organization and the objectives pursued. In some cases, a combination of the two approaches may be necessary to achieve the desired results.

Table 5 provides a summary of the indicators to be monitored by the managers of the motor vehicle repair service organization.

The table above provides an overview of key performance indicators (KPIs) used to monitor and evaluate success in different departments of an organization. These indicators range from financial measures, such as uncollected amounts and expenses, to operational indicators such as the number of orders in production or the time it takes to close orders. By carefully tracking these KPIs, managers can identify areas for improvement, make informed decisions, and ensure optimal performance of each department in achieving organizational goals.

Effective inventory management is crucial for automotive repair service providers. To ensure optimal stock levels and efficient operations, the spare parts commercialization activity is closely monitored using key performance indicators (KPIs).

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs):

Average Stock: Calculated as the mean of the stock value at the beginning and end of the analyzed period. It provides insights into the overall inventory level maintained.

Stock Rotation Factor (FR): Measures how many times the average stock is sold within a 12-month period. A higher FR indicates efficient inventory turnover.

Service Degree (GS): Represents the percentage of requested spare parts that are readily available in stock. It reflects the organization’s ability to fulfil customer demands promptly.

Calculation and Interpretation:

By actively monitoring these KPIs, automotive repair service providers can maintain optimal stock levels, reduce carrying costs, improve customer satisfaction, and enhance overall operational efficiency (

Table 6).

Key strategies for maximizing profit from spare parts sales include:

Adaptation of stock to customer demand

Flexible discount policies, in line with the market—Regular renegotiation of purchase prices

Active marketing to promote competitive advantages

The Auto Repair Shop Manager has a key role in ensuring the efficient and profitable operation of the shop. Responsibilities include managing human and technical resources, monitoring performance, ensuring quality and meeting delivery deadlines. By successfully performing these tasks, the shop manager contributes to increased customer satisfaction and overall organizational success (

Table 7).

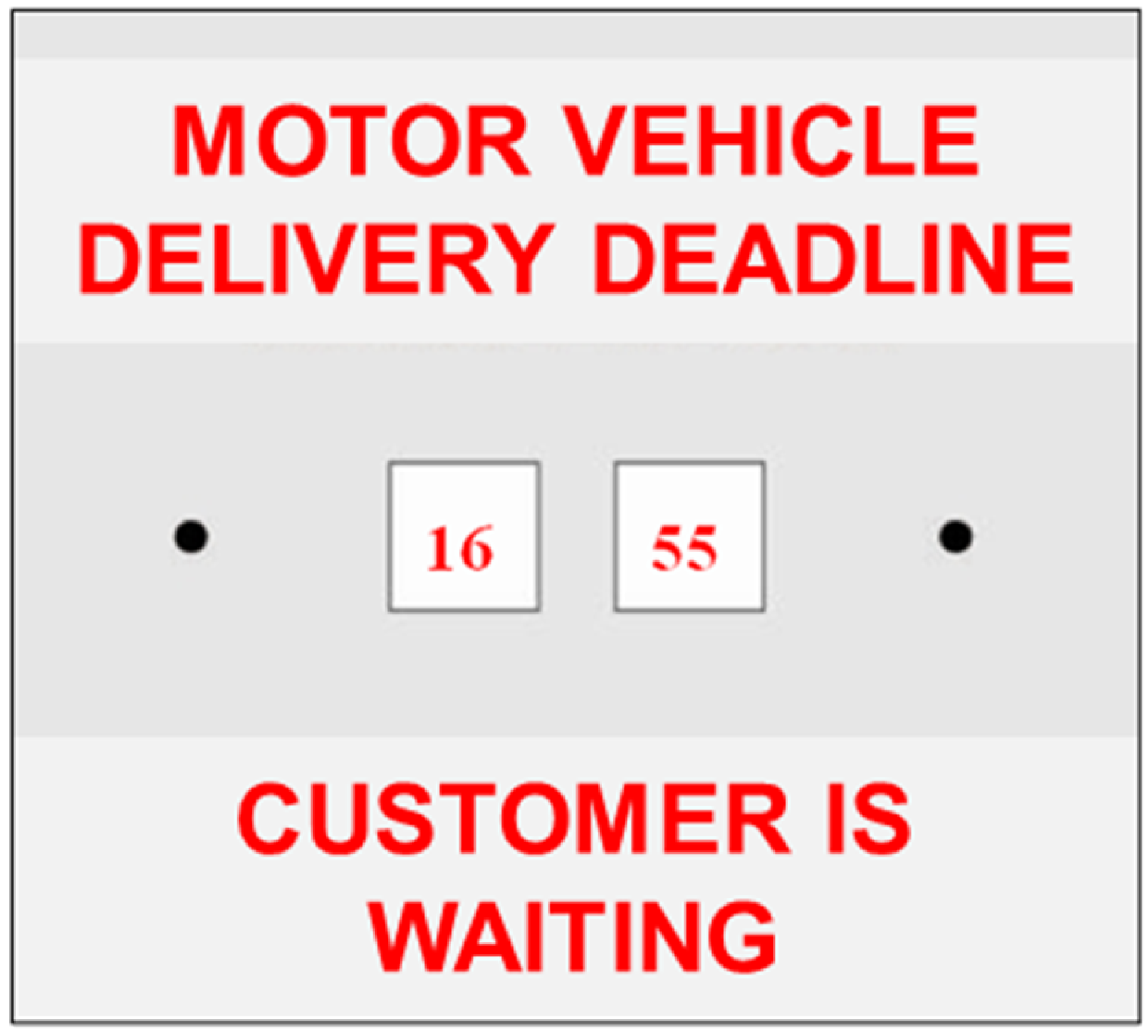

A system (

Figure 7) has been introduced to enable workshop managers to efficiently and easily manage repair completion deadlines in the service workshops by remotely visualizing the deadline by which the vehicle must be handed over to the customer by the receiver. If he finds that the deadline cannot be met, the workshop manager notifies the service advisor so that the customer is informed in good time.

Table 8 presents a few concrete measures that can be implemented to improve the performance of the Service department in terms of both quality and quantity.

Figure 8.

Model to identify SDV.

Figure 8.

Model to identify SDV.

Implementing these measures can make a significant contribution to improving the performance of the service department, both in terms of quality and quantity. By optimizing processes, reducing downtime and increasing customer satisfaction, the department can become more efficient and profitable.

By implementing actions and adopting an organizational culture focused on customer-centricity and continuous improvement, the Service department can achieve a higher level of performance and make a significant contribution to the success of the entire organization.

Actions to increase the number of billed hours in service include (

Table 9):

Optimizing the sales process:

Empower service advisors and parts sales managers to give discounts, speeding up the sales process.

Collect information on lost sales (out of stock, long delivery times, overpricing) through the management system, eliminating the need for manual reporting.

Efficient stock management:

Offer special prices for parts with non-moving stock, thereby reducing costs and boosting sales

Develop active spare parts sales service with the aim of generating at least 10% of total parts sales

Constant monitoring of stock and urgent orders by the Head of Supply and After Sales Manager.

Quality assurance of service processes: