1. Introduction

The circular economy (CE) is being adopted as a strategy by a growing number of countries to meet their climate change goals [

1]. In Europe, it is seen as a key component to foster sustainable industrial practices and reduce the Union’s dependency on critical raw materials and vulnerability to global supply-chain disruptions [

2,

3]. The transition from a linear to a CE requires the involvement of multiple stakeholders, extensive cooperation across governmental levels, territorial scales, policy areas, and economic sectors [

4,

5], representing not just an incremental shift but a radical transformation of economic structures, demanding systemic changes at all levels of production and consumption [

6]. CE can be implemented across different scales: at the micro level, encompassing products, companies, and consumer behaviors; at the meso level, involving regional initiatives such as eco-industrial parks; and at the macro level, encompassing national and global policies as well as overarching industry structures [

5,

7]. Such multi-scalar approach requires the integration and redesign of industrial, infrastructural, and social systems to facilitate a circular flow of resources [

8].

Circularity is achieved through various strategies designed to slow down the rate at which materials and products complete their life cycles [

9]. These strategies operate at different levels of material looping, as described by Potting and colleagues [

10] in the 10R framework, which prioritizes actions toward CE. Potting’s report distinguishes lifecycle stages, ranging from the conceptualization and design phase aiming at smart product use and manufacturing—Refuse (R0), Rethink (R1), Reduce (R2)—to strategies focused on extending product lifespan—Reuse (R3), Repair (R4), Refurbish (R5), Remanufacture (R6), Repurpose (R7)—with material and energy recovery (R8–R9) being the last resort.

The highest level of circularity—smart product use and manufacture—is increasingly facilitated by digitalization. This enables the dematerialization of products and services through virtualization, remote service provision, and digital marketplaces that support sharing and the second-hand economy [

11]. These innovations contribute to reducing material consumption by replacing physical goods with digital alternatives. Descending the R-ladder, product life extension encompasses activities that return a product to a functional state for continued use, preserving its embedded market value, which can be achieved through reuse, repair, refurbishment, and remanufacturing. While reuse and repair allow products to reach or slightly exceed their expected end-of-life, refurbishment and remanufacturing significantly prolong product lifespans beyond their initial design expectations [

12].

The circular strategies outlined in Potting’s work suggest a transformation in production and consumption patterns, requiring a structural shift in business models [

13]. These strategies can be practically implemented through concrete business actions or circular business models (CBM) such as those proposed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) in the ReSOLVE framework—Regenerate, Share, Optimize, Loop, Virtualize, and Exchange [

11,

14]. Among the most prevalent types of CBM are those that deliver novel product-service systems (PSS) [

15], often referred to as servitization or pay-per-use services [

16]. The PSS concept has been closely linked to the sharing economy [

17], and its varied interpretations across different research disciplines reflect its broad application and significance [

16].

An increasing number of manufacturing and service companies are emerging with CBM offering life extension services, such as repair. Currently, CBM are operational across a wide array of sectors, including plastics, construction, agribusiness, water, textiles, and metallurgy [

18]. Despite the growing role of CBM in facilitating the circular transition, businesses face several barriers that require direct policy intervention [

12].

Public policy is recognized as a relevant instrument for the implementation of the CE [

19,

20]. An adequate policy landscape is considered among the most effective ways to encourage circularity in organizations [

21], having also an important role in fostering consumers’ demand for CE products [

6]. The European Union (EU) is considered a frontrunner in the deployment of CE-supporting policies. To advance and facilitate this transition, the EU as well as Member State’s governments have been adopting a growing portfolio of CE-related policy measures, including several legislative actions [

22] which reflect the importance of this paradigm to the Union, and the crucial role of national and supranational public institutions to promote it [

6]. Despite the growing number of CE-policy initiatives, to date, global production systems remain primarily linear [

20], and most materials entering the economy are virgin, with the share of secondary materials declining from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% in 2023, according to the Global Circularity Gap Report 2024 [

23].

Current EU sustainability policy is criticized as being ineffective, outdated, complex [

24], acting as a barrier to circularity [

18,

25,

26] and still too focused on waste management [

25,

27]. In this current context, several authors emphasize the importance of gaining deeper insight into how existing regulatory frameworks may hinder the adoption of circularity, and how they might be effectively restructured [

28], since innovative policy solutions are required in support of the adoption of distinct CBM [

21,

24,

29].

An extensive body of scientific literature has previously dissertated on the whole set of barriers and incentives to the CE and its business models, which [

30] classified as “market”, “technological”, “cultural” and “regulatory”. More recently [

24] presented a broad overview of determinants for CBM adoption, encompassing both top-down and bottom-up factors. In a lesser extent, several publications focused on policy incentives for circularity, targeting either different life-cycle stages [

8,

20,

31], specific products and sectors [

32,

33,

34,

35], stakeholder collaboration [

4] or the interaction of governmental policies with distinct CBM [

11].

Considering the central role of policy in advancing circularity, and the growing number, diversity, and nature of policy instruments, a gap was identified in the literature: the absence of a dedicated framework that categorizes all relevant CBM-supporting policy instruments into major policy determinant categories. Such a framework should also encompass fundamental aspects of policy conception and implementation, namely policy agenda and policy governance. Recognizing the need to address this gap, the authors identified the necessity to conduct an investigation to capture emerging approaches and trends in CBM-supporting instruments and enabling factors driven by policy action. In light of these considerations, the main objectives of this research are: (i) to identify and categorize, based on a literature review, the key policy determinants supporting the adoption of CBMs; (ii) to develop a comprehensive analytical framework that systematically maps the relevant policy instruments and enablers to be considered for supporting CBMs; and (iii) to provide actionable insights for policymakers and researchers to assess existing policy landscapes, identify gaps, and design integrated policy mixes tailored to specific contexts.

Unlike previous reviews, which have generally explored CBM policy determinants from more fragmented or sector-specific perspectives, the originality of this work lies in the development of a comprehensive and unified analytical framework. By systematically organizing and interrelating the main policy determinants identified in the literature, this study advances the field by providing a structured basis for comparative analysis and integration across governance levels and policy domains, thereby contributing to a more holistic understanding of how policy can advance CBM. The resulting framework will be useful to both scholars and policymakers in all governance levels, to evaluate if and how current CBM-supporting policies in specific contexts span all relevant policy determinant categories, identify policy gaps, offer insights into potential supporting instruments and policy mixes, while guiding further qualitative and quantitative studies. Taking into consideration, as previously noted, the critiques on an excessive focus on waste management, this review concentrates on high circularity strategies, as defined in Potting’s work, namely smart production and consumption, and product life extension.

This paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodology and criteria followed to develop the present review.

Section 3 presents the results obtained, particularly insights from literature on CBM key policy determinants, respective instruments and enablers and the resulting analytical framework.

Section 4 discusses the results obtained and describes the theoretical and practical implications of this study. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper while also discussing the study limitations and future research avenues.

2. Methodology

To develop an analytical perspective of literature insights into the several CBM-supporting instruments and enabling factors potentially empowered through policy action, the most adequate method is a literature review. This method critically examines and synthesizes existing research on a specific topic, enabling researchers to contextualize their work within the broader academic discourse, identifying established knowledge, highlighting gaps or inconsistencies, and providing a foundation for further investigation [

36]. This review followed the methodology proposed by [

37], based on a sequential four step process namely, review design, conducting the review, analysis of selected literature and review article writing.

2.1. Designing the Review

The CE and its associated business models have been explored across a wide range of research areas and disciplines. In this context, to achieve the research objectives outlined in the previous section, a semi-systematic literature review was deemed the most appropriate methodology, as it is particularly suited to topics approached from multiple conceptual perspectives and investigated by scholars from multiple disciplinary backgrounds [

37].

Definition of search terms and strings: A first scoping search was developed to identify relevant research areas and key words, through the search of scientific publications in google scholar and analysis of their key words. Grey literature from recognized international organizations was also considered.

Publication types: The selected publication types included both scientific literature, namely peer reviewed scientific journal articles and conference proceedings, as well as hand-selected “grey literature”. This approach allowed to capture the different roles and cooperation mechanisms of different stakeholders [

4] resulting in a more balanced and robust research process, minimizing possible bias [

32]. Grey literature selection included policy reports from recognized European and international organizations such as the Ellen Macarthur Foundation, World Bank, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, Circle Economy & Deloitte, among others.

Citation databases: This review draws upon the two major multidisciplinary citation databases for peer-reviewed literature, Scopus and Web of Science (Core Collection: Citation Index). These databases are internationally recognized as the most comprehensive and authoritative sources for bibliometric and systematic reviews, providing broad coverage across the social sciences, natural sciences, engineering, and technical fields.

Selection criteria: To reach a manageable and representative sample of relevant scientific publications for the purpose of the study, both inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. These were formulated in a sufficiently broad fashion to capture as many CBM types as possible related to high circular strategies. In this sense, inclusion criteria include: (a) Published articles, reviews, conference papers and book chapters in the relevant research areas; (b) Articles targeting high circular strategies, such as servitization or PSS and product life extension, such as repair. Exclusion criteria include: (a) Papers published in languages other than English; (b) papers focused on low circular strategies, namely waste management, recycling and energy recovery; (c) papers focused on industrial symbiosis, predominantly associated with the recycling and valorization of waste and by-products.

Citation chaining: A set of 22 additional publications were added to the selected sample, allowing additional and deeper insights covering: (i) contextual analyses of specific CBM (e.g., reuse, PSS, servitization); (ii) the role of digitalization; (iii) CBM design and innovation; (iv) perspectives from companies; and (v) references substantiating key concepts in the framework, e.g., policy governance, identified as a relevant CBM determinant.

2.2. Conducting the Review

The research process, encompassing the literature search, sample selection, and detailed analysis, was conducted between January and May 2025. The following search string as applied: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Circular Economy” OR Circularity OR “Circular Business Models”) AND (Polic* OR Regulat* OR Government*) AND (driver* OR enabl* OR incentiv*) AND (barrier* OR hinder* OR gap*).

Table 1 resumes the publications’ sample selection process.

The selected sample comprises scientific articles published across a diverse range of journals. The most represented are Journal of Cleaner Production (26%), Sustainability (15%), Resources, Conservation and Recycling (6%), Ecological Economics (6%), Business Strategy and the Environment (4%), Journal of Environmental Management (4%), and Sustainable Production and Consumption (4%). The remaining 35% of the articles were published in various other journals, reflecting the interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral nature of the topic under study. The sample is strongly concentrated in the last five years, with 24% of the articles published in 2023, 20% in 2024, 14% in 2022, and 21% in 2021. This distribution shows that the review is largely informed by recent contributions, capturing the most current developments in the field.

2.3. Literature Analysis

A thematic content analysis was applied to the selected literature aiming to capture a contemporary overview of CBM policy instruments and enabling factors, converting it into an overarching framework illustrating the main CBM policy determinants. A thematic or content analysis was considered the most appropriate method to the targeted objectives since it is a widely used qualitative method for “identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns in the form of themes within a text” that address the research question [

37].

3. Results

While there is a consensus in the literature on the fact CE will not be achieved through isolated measures alone, there are different perspectives on possible systemic approaches. As in other policy fields, CE is being promoted through different policy tactics, particularly, production and consumption policies [

6], market and non-market based [

38], public and private [

39], demand-pull and supply-push [

3,

40], with governments having either an active or a passive role [

41], combining the power of law—command and control—with “soft-powers”, the latter aiming to promote a shift in current values and practices through new attitudes and preferences [

42].

Aiming to set a common transition path, the EMF proposed a set of universal policy goals focusing on circular design, resource preservation, economic incentives, innovation, skills and transversal collaboration [

43]. In turn, [

40] examined demand pull government policies in support of PSS, categorizing them into regulation, economic incentives, information and green public procurement (GPP).

Referring to an optimal functional definition for CE regulatory policy packages around the world, ref. [

44] proposed a multilevel hierarchical approach, headed by an overarching policy aim explicitly reflecting the commitment to circularity (policy agenda); policy objectives supporting CE principles at all governance levels and value-chains; and a mix of specific implementing mechanisms including legal enforcement, market-based and informational instruments, voluntary and institutional tools. Specifically referring to CE packages in Europe, ref. [

25] found that these are essentially based on economic, regulatory, R&D and information policy instruments.

Independently of the instruments selected and how they are combined into a specific policy package, coherence and complementarity between policy measures are required to meet overarching policy goals and stakeholder expectations. This fact leads to the importance of governance in the context of policy. Referring to environmental management, ref. [

45] stressed the importance of governance as a factor either enabling or undermining its effectiveness based on the capacity, functioning and performance of “institutions” (e.g., laws, policies, rules), “structures” (e.g., decision-making bodies, formal and informal organizations), and “processes” (e.g., decision-making, negotiation, conflict resolution). One of the attributes of environmental governance robustness is polycentric governance [

45], characterized by [

46] as a multiple and interdependent center of decision-making assumed to be effective at helping policymakers to tackle “complex collective action problems”, and framed by the authors into an interplay between contextual and operational arrangements, outcomes and respective feedbacks.

In the context of the crucial role of policy for CBM, it is essential to also consider the barriers posed by policy itself. Regulatory gaps, conflicting legislation, misaligned visions among government bodies, deficient or weak enforcement and inadequate support mechanisms are some of the reported barriers significantly hindering the transition to circularity [

2,

18,

24,

26,

47,

48].

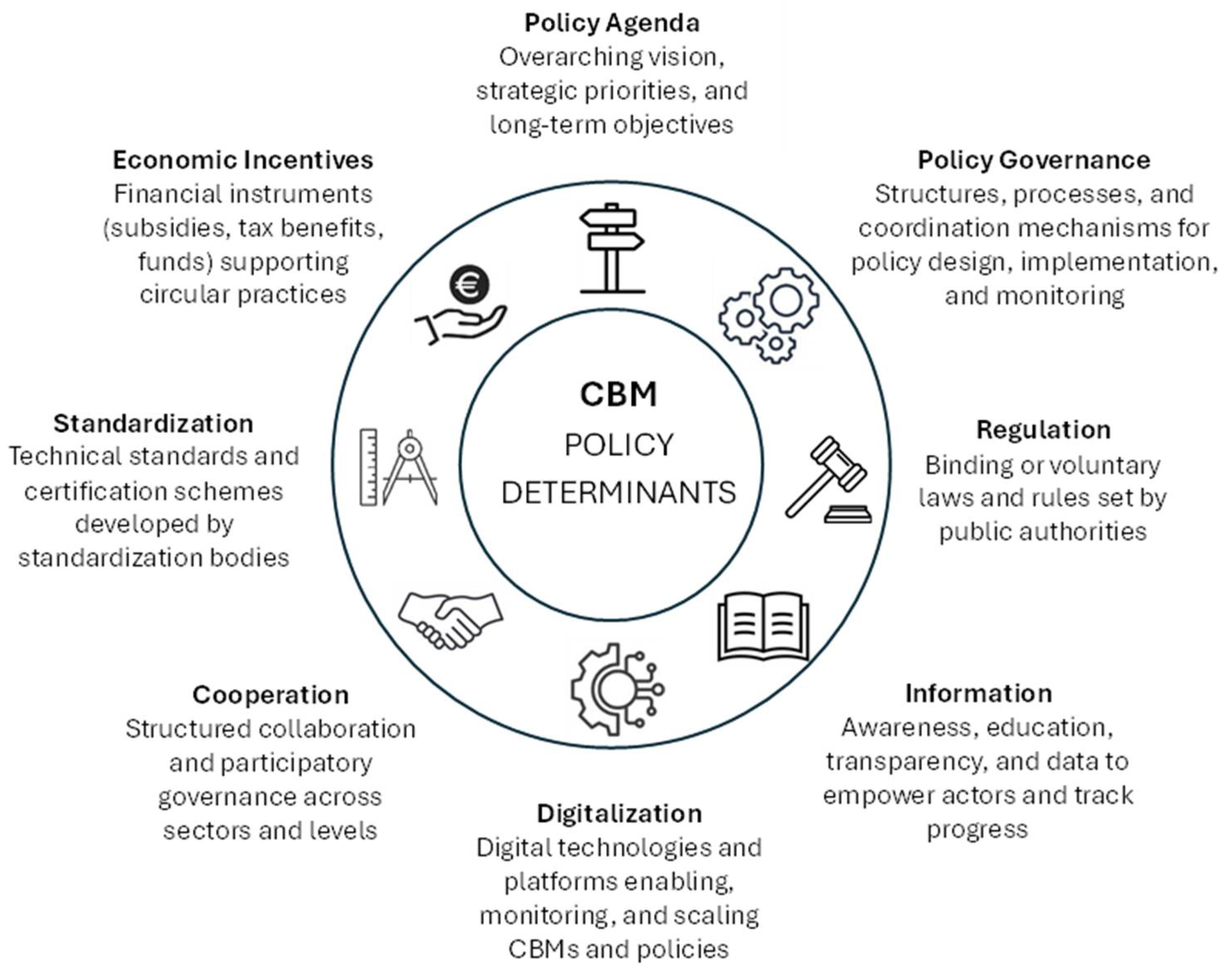

In light of the above, the literature review allowed the identification of major policy determinants—understood in this work as overarching policy-related factors that, depending on their presence, design, and implementation, can either facilitate or hinder the adoption of CBM. These include: (1) Policy Agenda, (2) Policy Governance; (3) Regulation; (4) Standardization; (5) Economic Incentives; (6) Information; (7) Cooperation and (8) Digitalization. Within each of these determinants, a variety of specific policy instruments or enablers can be deployed through a multi-level governance approach (European, national, and local) to foster CBM adoption [

32]. Such instruments and enablers are detailed in the following subsections. To ensure conceptual clarity before proceeding to the detailed discussion of each determinant,

Figure 1 provides a visual summary and the definitional boundaries of the eight key policy determinants, as derived from the literature review.

3.1. Policy Agenda

The complexity of transitioning to a CE requires a clear vision or imaginary of what it will be and the pathways to achieve it [

8]. Historical discourse analysis has revealed that circularity imaginaries evolved over time, shaping policy priorities and acting as powerful tools conditioning how circularity is conceptualized and implemented [

49,

50]. Imaginaries of circularity are shaped by both external and internal factors. External factors such as socio-economic conditions, public opinion, developments in other policy areas, influence policy agenda [

51]. Also, technological advancements are driving policy responses to emerging technology-led business models [

11]. External factors alone are insufficient to drive policy change. Internal, actor-driven factors—such as the motivations of different stakeholder groups—also shape circularity imaginaries and influence governmental agendas [

51]. In the opposite direction, policy can shape behaviors and decisions by signaling the expected evolution of market trends. Broad strategic initiatives, like the European Green Deal, clearly communicate to businesses the urgency of raising their environmental ambitions [

52].

Such a myriad of both internal and external influencing factors increases complexity which may explain the lack of a supportive policy agenda for higher R-strategies stressed by several authors. These argue that current CE policies largely consist of incremental adjustments within a predominantly linear resource system, with the existing EU policy framework primarily focused on end-of-life management, aiming to improve recycling and reduce resource loss [

39,

44,

53]. Despite the emergence of national CE legislation across several EU countries, many policies at both national and regional levels remain centered on downstream waste management [

18]. A systemic approach is widely recognized as essential for achieving CE objectives, requiring a balance between triple bottom line sustainability impacts, information flows across value chains and lifecycle stages, and interactions among several societal actors [

53], often with conflicting interests. Shifting policy focus towards the entire product lifecycle, including eco-design and circularity-driven design, is crucial [

54]. Additionally, anticipating and addressing regulatory conflicts before implementing new policy instruments is necessary to avoid unintended outcomes [

18], as those exemplified in

Section 3.2.

The social dimension of the CE remains largely overlooked in policy frameworks. According to [

55], strengthening this pillar requires setting mandatory targets for circular job creation, investing in the social and solidarity economy, and promoting circular skills development. However, as [

56] highlights, social aspects are often addressed superficially, with little systemic implementation or accountability. Furthermore, ref. [

57] argues that there is still limited debate on the ethical and social implications of CE policies, including employment shifts and unintended consequences. To address these gaps, ref. [

58] advocates embedding justice and inclusivity in CE development by promoting decent work, meaningful employment, and international guidelines on social equity. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) stressed the need to recognize and support the informal economy, given the prevalence of reuse, repair, and refurbishment activities outside formal regulatory frameworks [

54]. Additionally, ref. [

28] highlights the importance of mitigating power asymmetries between start-ups and incumbent firms to ensure a fair transition. As [

59] suggests, improving the social perception of reuse and repair activities, alongside better working conditions, requires targeted public policies and investment in SMEs. The WBCSD underscores the need to actively engage civil society in CE governance, prevent deepening inequalities, and protect worker health and safety [

60].

A key enabler of the CE is a long-term stable policy agenda. The prevalence of short political cycles and the prioritization of immediate results hinder policymakers’ commitment to long-term measures [

53]. Such instability leads to business hesitation in adopting circular strategies, particularly CBM requiring substantial investment and extended payback periods, as short-term political decisions make it difficult to anticipate future regulatory scenarios [

11,

25]. For example, in the energy sector, several authors argued that policy continuity has proven essential in ensuring the viability of sustainable business models [

61,

62,

63]. Given that the benefits of the CE tend to materialize over the long term, predictability and stability of policies are crucial for the effective implementation of CBM, allowing for mitigating transition risks and encouraging long-term investments [

40,

53].

3.2. Policy Governance

Governance structures and processes can be driven from the top or from the bottom, with various actors leading the change [

45]. Top-down governance, led by governments and public authorities through policies and regulations, contrasts with bottom-up governance, where local communities, entrepreneurs, and civil society initiate change [

64,

65,

66]. While top-down strategies are essential for ensuring large-scale impact, bottom-up initiatives, often rooted in local needs and actions, can influence policy and drive collective change [

67]. Many authors advocate for a combination of both approaches to promote the CE with bottom-up initiatives benefiting from supportive policy environments to scale up [

4,

42].

Independently of the approach, policy leadership is crucial for scaling the circular transition in all sectors [

43]. As emphasized by [

12], governmental leadership is vital in driving policy transitions aimed at increasing resource efficiency and promoting the wider adoption of life extension strategies. In the strong circularity model proposed by [

50], based on the balance between ecological, economic, and social priorities, the state takes on leadership and, as emphasized by [

18], governmental institutions must not only show initiative but also have the necessary capacity to lead the change.

Public authorities play a crucial role as major consumers in the market, granting them significant influence to drive the circular transition through the integration of circular criteria into procurement tenders, for example, prioritizing reused and remanufactured products [

8,

12]. Green Public Procurement (GPP) has been widely recognized in the literature as a direct mechanism through which policy objectives are translated into practice, reinforcing the connection between governmental purchasing decisions and CE advancement, particularly the market demand for CBM [

25,

31]. However, challenges persist, particularly concerning the limited knowledge of policymakers on circular procurement, their reliance on conventional tendering approaches as well as increased complexities associated with PSS procurement processes. Addressing these gaps requires collaboration between stakeholders particularly policymakers, academia, OEMs and reconditioners, targeting enhanced competencies among public procurers, sector-specific circular public procurement guidelines and revision of procurement frameworks [

31,

68,

69].

In the context of institutional governance, another important aspect relates with regulatory simplification, with several authors calling for reduced administrative burdens associated with circular activities, reduced bureaucracy and harmonization of regulatory complexity [

2,

70]. Simplified regulatory frameworks and direct government intervention can also enhance the scalability of CBM [

8,

11,

12,

71].

Effective CE governance requires both horizontal and vertical coordination to ensure policy alignment, which is not always a reality, leading to misaligned and conflicting policy instruments. Several authors point out, for example, restrictive product requirements hindering certain applications of feasible circular products [

72,

73]. In turn [

70] highlights the future extension of Basel Convention’s scope to all e-waste, which can potentially disrupt reverse supply chains for repair and refurbishment; or regulatory classifications treating waste oils as hazardous, thus creating obstacles for their regeneration and reuse thus hindering the development of “oil-as-a-service” business models. Effecting regulatory changes in one sector or value chain may lead to knock-on effects to other sectors and companies along circular value chains, which calls for the necessary debate and alignment between economic sectors and policy areas, given the CE’s cross-sectoral nature [

74]. Regarding vertical coordination, while EU-wide regulations provide overarching direction and prevent market fragmentation, their implementation depends on national and local authorities, which must adapt policies to their specific contexts [

17,

32,

75]. However, misalignment persists, with national, regional, and local policies often lacking coordination, leading to fragmented and conflicting approaches and inefficiencies [

18,

53,

54].

National policies are crucial for setting broad CE objectives, yet their effectiveness depends on adaptation at regional and local levels [

32,

76]. Local governments, due to their proximity to socio-economic realities, play a pivotal role in implementing CE initiatives and fostering service-based solutions [

75,

77]. Cities are key facilitators of CE transition, enabling innovation in business models and sectoral integration [

11,

69]. Despite this, their role remains underrecognized [

4], highlighting the need for greater financial, technical and regulatory support from national authorities [

77].

Scaling to the international landscape, CE policy is highly fragmented across countries, with over 75 CE action plans and thousands of evolving commitments spanning multiple sectors [

54,

58]. This fragmentation risks creating barriers, including to trade, encouraging nationalism, as governments focus on domestic goals like competitiveness and reduced dependence on imports [

58]. To address these challenges, enhanced global coordination is needed, such as through a cross-sectoral CE alliance or an international resource agency as proposed by [

58]. Without coordinated action, there is a risk of the emergence of “linear production havens” [

18] undermining sustainability goals.

3.3. Regulation

Regulation is a key driver of the CE, shaping both businesses and consumer behaviors [

6,

34]. As suggested by some authors, strong and effective regulatory measures can better reshape CBM than other policy approaches [

11]. Particularly addressing the sharing economy, ref. [

78] argued that regulation targeting the reduction in owner’s risks is expected to increase the circularity effect.

Regulatory frameworks vary in scope and enforcement. Mandatory regulation such as EU Directives impose legally binding obligations, with non-compliance leading to penalties. While ensuring uniform implementation, these measures may hinder innovation due to their rigidity [

8,

39]. In contrast, voluntary measures, such as the EU Ecolabel, allow greater flexibility but rely on industry participation, which can limit their effectiveness [

8]. A further distinction exists between mandatory regulation and self-regulation. While government-imposed laws enforce compliance, self-regulation relies on industry-led initiatives, such as environmental standards and agreements. This approach aligns with trends towards deregulation but lacks enforcement mechanisms [

39].

Regulatory policies are also classified as demand-pull or technology-push instruments. According to [

3], demand-pull measures create or expand markets through incentives such as taxes, subsidies, and public procurement, whereas technology-push policies encourage CE adoption without imposing specific technological choices. Empirical evidence from this author suggests that both types of instruments, alongside command-and-control regulation, significantly influence SMEs’ willingness to invest in CE, particularly in countries with stricter regulatory frameworks.

Other authors such as [

6] examined the dichotomy and effect of both production and consumption-side policies supporting the development of CBM; the former supporting implementation of CE in organizations, the latter, in the form of regulatory and information policies, having the potential to positively affect the demand for CE products.

Since high-level CE strategies cannot be achieved through isolated measures alone, various scholars propose different policy mixes or portfolio approaches to create a systemic and integrated response. As argued by [

8], a successful policy mix must go beyond loosely connected measures and focus on eliminating contradictions while fostering synergistic effects. This author identified three key policy areas with significant potential to advance the CE and requiring a combination of mandatory and voluntary measures, particularly: policies for reuse, repair, and remanufacturing; green public procurement (

Section 3.2) and policies supporting extended producer responsibility (EPR). EPR policies in particular are widely recognized as critical drivers for CBM and PSS, assigning responsibility to producers for all stages of a product’s lifecycle while promoting the design of durable, repairable, and recyclable products [

34,

79]. In this respect, authors call for the expansion of EPR schemes to increase circularity, in sectors such as textiles and construction [

2], as well as harmonization of EPR frameworks and their alignment with waste management and product policies to promote closed loops and maximize environmental value [

60].

Aiming to reflect the views of practical implementers of CBMs from five different economic sectors, ref. [

12] proposes as a mix of priority horizontal push and pull incentives based on circular public procurement, mandatory reuse targets and access to information promoting reuse.

Focusing PSS in the energy sector, ref. [

40] highlights that government policy alone cannot address all factors necessary for success proposing a balanced portfolio combining demand-pull policies such as regulatory and fiscal instruments and supply-push policies, e.g., information and skills (

Section 3.6). Concrete approaches for such a proposed policy mix are left for future research.

The interconnected barriers to repair activities from both supply and demand perspectives were discussed by [

9]. Factors such as consumer knowledge, throwaway culture, and the lack of attachment to products complicate repair decisions. Policy interventions should target these barriers through changes in consumption laws, such as the right to repair, while providing supporting information instruments. The author proposes a three pillar “repair society” framework based on infrastructure to ensure access, business incentives to make repair economically viable, and cultural/market changes to support repair preferences.

Particularly in the UK context, authors have identified several actions to promote the repair economy, ranging from a wide set of market-based instruments, product policies as well as standards and certification schemes. Some of the proposed measures include VAT adjustment for repair businesses, extending warranty periods, setting measurable national targets for reuse, repair, and remanufacturing, repair related regulation and certification schemes [

80].

The World Bank, focusing on the EU context, argues that a comprehensive policy mix should address both production and consumption policies, according to the specific material being targeted, and deploy different and complementary instruments, including both regulatory and fiscal measures [

18]. At global level, authors of the 2024 Circularity Gap Report advocate country-specific policy mixes based on the Human Development Index (HDI), suggesting higher-income countries should focus on reducing material consumption; middle-income nations should stabilize it, and lower-income countries should adopt circular practices to increase material consumption in a sustainable way [

23].

Looking now at the fiscal system, markets for secondary products and materials remain underdeveloped often due to fiscal frameworks favoring linear models, such as subsidies for fossil fuel industries or low tariffs, for example, in the water sector [

18,

81]. These imbalances highlight the need for a fiscal reform in favor of circular businesses. In fact, fiscal instruments are key regulatory tools for sustainability, either penalizing negative externalities (e.g., carbon taxes, PAYT systems) or incentivizing circular practices through tax benefits for renewables [

25,

31,

40]. These instruments can target consumption behaviors (e.g., taxation on single-use plastics) or business operations (e.g., subsidies for non-virgin feedstock) [

54].

A core strategy is differentiating taxation to reflect environmental costs. Tax incentives like exemptions or subsidies can support businesses in transitioning to circularity [

34]. In the EU, while taxation remains largely under Member State jurisdiction, Sweden and Denmark exemplify effective policies, such as taxation on pesticides fostering servitization models and car-sharing schemes flourishing in high car-tax environments [

17].

The extant literature on CE drivers highlights VAT policies as significantly influencing circular practices. For example, Sweden reduced VAT by 50% on repair services [

31], but the VAT Directive still excludes electronic services despite their perceived environmental benefits [

17]. Additionally, a lack of harmonized definitions for circular goods and services complicates implementation [

41].

Shifting the tax burden from labor to material use is also widely advocated, as high labor taxes hinder PSS and circular activities like reuse and remanufacturing [

25]. Ref. [

18] highlights that using CE tax revenues to reduce labor taxes could counteract economic distortions and support resource-efficient business models while promoting employment in circular activities. Ref. [

59] argue that tax incentives for labor-intensive models, such as repair and reuse, could help improve their cost competitiveness.

Addressing negative externalities through taxation, such as carbon or environmental taxes, has also been proposed to reflect real costs in linear business models [

70]. While there is no commonly agreed framework to value externalities, it has been suggested that the Global Circularity Protocol could incorporate true pricing indicators to facilitate this process and establish a standardized approach [

54].

Phasing out subsidies for linear industries, particularly fossil fuels, is essential to eliminating market distortions [

18]. Redirecting financial incentives to circular businesses can support resource-efficient practices [

76]. Policy recommendations include tax relief for service-based models [

70], fiscal support for labor-intensive circular activities [

59], and taxation schemes that promote secondary material markets while discouraging virgin material use [

2]. A tax on virgin raw materials or exemptions for recycled materials could address price disparities, though success depends on technological advancements and market support [

23,

74].

Additionally, as suggested by [

43], tax and procurement policies should promote repair, sharing, resale, and remanufacturing, while harmonizing collection and sorting systems. Additional measures, such as penalties on premature obsolescence are necessary to align regulations with circular principles. Fiscal instruments are crucial for the circular transition, but their effectiveness depends on integrating external costs, reallocating incentives, and ensuring coherence across fiscal measures to avoid distortions.

3.4. Standardization and Certification

Several authors stressed the importance of establishing harmonized concepts, requirements, boundaries and scales when considering circular models, products and systems, starting with a universally accepted taxonomy for the CE [

21,

56].

Standardization and certification are fundamental to advancing CE practices by fostering consumer confidence, facilitating trade, and ensuring regulatory compliance. The absence of standardized definitions, quality benchmarks, and key performance indicators for refurbished and remanufactured products remains, according to several authors, a barrier to CBM; hindering product quality assurance, market acceptance, and cross-border trade [

25,

69,

82]. Likewise, the lack of systemic standardization presents a governmental challenge in implementing circular supply chains [

26], reinforcing the need for harmonized methodologies to support circular product design, repairability, recyclability, and reduced resource consumption [

21,

48].

PSS companies have emphasized the need for clear quality benchmarks for refurbished products to ensure durability and functionality, reinforcing the role of standardization in enabling CBMs [

70]. However, compliance with external standards can act as both drivers and barriers to circularity since while encouraging CE adoption [

83], excessively ambitious or misaligned standards may obstruct businesses [

84]. To address this, policymakers should balance normative and regulatory pressures to ensure legislative frameworks support rather than hinder circular transitions [

76].

The role of certification schemes is also crucial in creating trust in circular products and services. Certification ensures that products meet established sustainability criteria, reducing information asymmetry and increasing consumer willingness to adopt circular alternatives. Companies that comply with recognized CE standards and certifications not only secure regulatory approval but also enhance their reputation among stakeholders, suppliers, and customers [

34]. Additionally, ref. [

40] also stresses the importance of standardization for the harmonization of contractual frameworks as a way to streamline agreements, reduce transaction costs, increase trust and lower administrative burdens.

Policymakers and industry stakeholders must work collaboratively to ensure that standards align with technological advancements and industry needs. Many experts argue that the process of standard-setting should involve consultation with relevant stakeholders to prevent conflicts between new and existing regulations [

31]. According to an interviewee in [

31] study, an inclusive approach to standardization is essential to avoid excessive regulatory burdens while fostering widespread adoption of CE principles, emphasizing that such frameworks should be developed collaboratively rather than imposed through a top-down approach.

While British Standard BS 8001:2017 became the first internationally recognized standard dedicated to CE [

7], more recent instruments came to the stage targeting some of the gaps previously identified. Notably, at EU level, the Eco-design for Sustainable Product’s Regulation, establishing harmonized eco-design criteria for a wide range of products and, at international level, the International Organization for Standardization, providing global guidance on CE principles, offering harmonized vocabulary, principles, as well as guidance for implementation (ISO 59004) [

85], business model transition (ISO 59010) [

86] and circularity performance assessment (ISO 59020) [

87].

3.5. Economic Incentives

Economic incentives play a crucial role in facilitating the transition to CE, mitigating the financial burden on companies and encouraging investment in CBM. The high costs associated with CE implementation should not be borne solely by private firms and individuals [

38], as financial constraints often limit the ambition of businesses, particularly SMEs, preventing them from exploring innovative business models such as PSS [

3].

Direct economic incentives such as grants, subsidies, funding schemes, and public–private partnerships provide essential financial support to businesses adopting CE practices [

4,

34,

39]. Empirical evidence highlights that EU and national funding programs have been pivotal in enabling circular initiatives [

4], with grants cited as the most referenced policy enabler for CE development in the electrical and electronic equipment sector [

52]. Such funding mechanisms lower initial investment costs, thus facilitating the launch and expansion of sustainable projects [

34].

Public investment in research and development is another critical economic driver, fostering technological advancements essential for the CE. Innovation in materials science towards product durability, recyclability, and energy efficiency combined with optimized manufacturing processes reduce resource consumption [

34]. Also, public funding stimulating technological innovation promotes the generation of advanced scientific knowledge that can be harnessed by private sector actors, encouraging SMEs to adopt eco-design principles [

3]. Additionally, protected market niches provide companies with innovative business models the necessary stability to mature before competing in open markets, although excessive protectionism may risk limiting alternative business offerings and delaying an equitable circular transition [

11].

Despite these financial instruments, the allocation of funds has not been equally effective across all circular strategies. In their analysis of an EU public consultation survey [

42] highlight that while resource mobilization has successfully supported resource efficiency (R2) and the useful application of materials (R8–R9), it has been less effective in enabling product life-extension strategies (R3–R7). This finding points to the need to prioritize funding for high circular strategies. Moreover, ref. [

88] illustrate how funding mechanisms often overlook an essential aspect of circularity: business model innovation. Their study reports that a company was unable to secure funding for market testing of a CBM because public environmental innovation funds were primarily allocated to clean-tech development. This case underscores the importance of expanding financial support to include the testing and implementation of new CBM.

Beyond direct financial support, sustainable finance mechanisms, such as CE-focused investment taxonomies and financial benchmarks, enable businesses to secure funding from conscious investors and financial institutions [

34]. Equity funds aligned with CE principles assess companies based on ESG criteria, risk management, and circularity potential, contributing to a more robust financial ecosystem for sustainable business practices [

54]. In this context, a global financial architecture reform, including the establishment of a Global Circular Economy Fund, has been proposed to mobilize private capital, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [

58].

Nevertheless, economic incentives alone are insufficient to ensure the long-term viability of CBMs. While they provide an initial boost, businesses must ultimately become self-sustaining, driven by profitability rather than dependency on external support [

78]. Subsidies can render CBMs temporarily viable, but in many cases, they fail to create lasting economic value, making the business models unattractive and economically unfeasible [

41]. Therefore, as already stressed in

Section 3.3, strategic policy mixes are necessary, where economic incentives are complemented by other policy instruments such as standardization (

Section 3.4) and capacity-building initiatives (

Section 3.6) to create an enabling environment.

3.6. Information

Informative policy instruments such as public information and awareness, education, skills promotion or information on product content and quality, play a crucial role in fostering the CE [

12] and must target all the involved stakeholders.

Policymakers rely on data to design, implement, and assess legislation. As argued by [

53], data-driven policymaking is fundamental for the effective implementation of CE policies, necessitating the development of indicators and monitoring systems to ensure continuous progress. However, several authors argue that policymakers lack evidence-based knowledge to act on and support in a targeted way, for example, in what relates to the sustainability of CBM [

89]. Governments must also develop a comprehensive understanding of market structures and associated challenges to implement strategic policy decisions that upscale CBM such as repair activities [

9]. Additionally, ref. [

21] highlights the importance of creating an infrastructure for information-sharing to support the adoption and monitoring of circular practices, facilitate the exchange of best practices, and align circular performance across industries.

For businesses, the availability of information is a determining factor in CE adoption. Ref. [

52] notes that many companies remain uncertain about the profitability of circular innovations; therefore, disseminating information on successful companies and their business models is key. The authors argue that the success of frontrunner companies adopting PSS and leasing models increases market acceptance of alternative business models and encourages further industry engagement. Ref. [

3] further emphasize that SMEs with access to CE information are more likely to engage in CE innovations, particularly when they are aware of available funding programs. Ref. [

34] assert that corporate social responsibility, embedded in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) frameworks, plays a pivotal role in CE transition, with mandatory performance disclosure under EU regulations such as the Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive. Ref. [

43] also stresses the necessity of transparency, supported by taxonomy and disclosure requirements, to ensure credible sustainability commitments. In this respect, several authors argue that CE reporting remains primarily focused on waste indicators rather than holistic material flows, limiting its impact on accelerating the transition [

54].

Consumers also play a crucial role in the CE transition, yet they often lack awareness and understanding of its benefits, therefore raising awareness and changing attitudes among consumers and producers is imperative [

31,

32]. As noted by [

41], public authorities perceive that circular design incentives are only effective if consumers are well-informed about CE benefits, necessitating improved communication strategies. Ref. [

34] observed that growing sustainability consciousness is pressuring firms to disclose product lifecycle information and sustainability strategies. Ref. [

90] argues that the use of performance indicators to report on CE progress enhances engagement, comparability, and accountability while mitigating greenwashing risks. Green labels such as the EU voluntary EcoLabel are valuable information tools for promoting circularity, however they are often vague or poorly understood by consumers [

41,

47]. In what relates to product-life extension strategies, ref. [

42] highlights that informing consumers about repairable components or the durability of refurbished products can enhance their attractiveness.

To address these challenges, several cross-cutting instruments can benefit all stakeholders. Ref. [

32] stresses that awareness campaigns, particularly at the local level, can effectively target specific audiences and enhance understanding; ref. [

52] highlights capacity-building instruments which can be supported at the EU or national level, such as technical assistance programs, resource efficiency tools, or technical information centers. Overall, training and skills development are recognized as fundamental enablers, contributing to knowledge dissemination and deployment of CBM. Also, research, development and innovation in key areas such as material science and sustainable design can drive new knowledge towards CE advancement [

2]. Furthermore, ref. [

52] advocates for platforms showcasing successful CE case studies and product labels with credible and measurable criteria to enhance consumer confidence in second-hand and refurbished goods. Ref. [

70] suggests that knowledge-sharing on PSS models and real-world challenges can inform both businesses and policymakers, ensuring that regulatory frameworks and incentives effectively support the CE transition.

3.7. Cooperation

Aligning diverse perspectives towards a shared CE vision remains challenging [

4]. Therefore, collaboration among stakeholders and cross-sector partnerships are fundamental as they foster innovation and systemic change while addressing common challenges and providing opportunities to integrate different perspectives [

4,

8,

42,

91]. However, this collaboration is often hindered by cultural and social barriers, such as resistance to change, business culture, and reluctance to engage with other actors [

92,

93], limiting the implementation of CBM such as PSS, which are dependent on inter-organizational collaboration.

Multi-stakeholder involvement in policymaking is crucial to ensure broad acceptance and effective implementation of CE initiatives. The lack of cooperation between policymakers and other stakeholders has led to fragmented policies that overlook the complexity of value chains and fail to support bottom-up CE initiatives [

28,

94]. Additionally, policymakers face significant difficulties in applying CE concepts and theories to real-world situations, due to practical constraints, leading to inefficiencies and missed opportunities for systemic change [

53]. By engaging in participatory decision-making processes, policymakers can incorporate insights from industry, academia, and civil society to design policies that reflect real-world constraints and opportunities [

94]. Such engagement in the early stages of policy development enables a more dynamic and adaptive regulatory environment that can respond to emerging challenges and innovations.

Policymakers at various governance levels—national, regional, and local—can act also as facilitators of cooperation by implementing regulatory frameworks that encourage businesses to cluster efforts, thereby addressing supply chain barriers [

40,

52]. Collaborative dialogue between policymakers and local CE initiatives can help design policies tailored to specific regional needs [

95]. As further argued by [

67], promoting structured dialogues with businesses, NGOs, and research institutions can ensure that policy strategies align with industry needs while addressing environmental and social goals.

The literature identifies several structured cooperation models, including communities of practice, R&DI projects, institutional partnerships, and formal associations between policymakers and civil society [

19]. Governments can play a crucial role by providing funding and technological support and facilitating networks and information-sharing platforms to enable the introduction of innovative technologies and processes across value chains [

52].

The private sector has also a role in engaging into cooperation. Structured partnerships between circular startups and established firms can support innovation ecosystems. Such partnerships can be fostered by governments through, for example, the organization and hosting of B2B network platforms, as seen in sector-specific initiatives such as CB’23 in construction [

28]. Also reporting standards (

Section 3.4), which require information sharing across the value-chain, can further incentivize deeper collaboration among businesses.

3.8. Digitalization

Digitalization has been widely recognized as a key enabler of the CE transition across various sectors. The literature highlights its decisive role in enabling dematerialization, remote service provision, product traceability, the creation of digital marketplaces connecting supply and demand, as well as predictive maintenance in PSS to extend product lifespans [

11,

69,

96,

97].

Among the main contributions of digitalization to circularity, its role in supply chain management is particularly noteworthy. Technologies such as Big Data and IoT can harmonize the complexity of circular industrial value chains and their interrelated subsystems, fostering the adoption of CE principles by individuals, industries, organizations, and society [

8]. The adoption of digital technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), facilitates inventory calculations, the Internet of Things (IoT) enables early detection of potential supply chain disruptions, while data analytics enhances material flows efficiency [

52]. Blockchain enables a more efficient, secure, and decentralized sharing economy [

78]. Additionally, these technologies enhance logistics control, stock and material flow visibility, future scenario anticipation, market dynamics monitoring, and complex systems management [

78]. Digitalization also plays a crucial role in improving supply chain traceability and transparency. The concept of the digital product passport (DPP) emerges as a solution to enhance supply chain visibility, ensuring material origin traceability, supplier sustainability, and accountability, thereby increasing trust between suppliers and customers while mitigating risks of reputational damage and greenwashing [

34].

In the realm of policy governance, digitalization is vital for data-driven policymaking. The use of big data, open data, and data analytics is instrumental across different stages of the policy cycle, from agenda setting to policy implementation and evaluation [

53]. Additionally, as argued by [

98] ICT came to facilitate greater participation, thus more inclusive deliberation in policymaking processes. In fact, e-participation initiatives such as consultation platforms, e-petitioning or one-stop participation portals have the potential to enhance the informational basis upon which public authorities make decisions, thus reinforcing democratic governance [

98]. The relevance of advanced IT technologies in driving circular transition is also emphasized by [

97], suggesting that governments play an active role in promoting appropriate digital infrastructures, such as blockchain architectures tailored for CE and digital government services that encourage repair and sharing practices. In this regard, the development of digital platforms for circular trade could be fostered by governments, facilitating more accessible and functional second-hand markets [

31]. However, the increasing proliferation of digital platforms across B2B, B2C, and C2C contexts may pose challenges related to competition and market fragmentation.

Regulations surrounding digital service provision remain nascent and must evolve to keep pace with technological advancements [

79]. As highlighted by the Ellen Macarthur Foundation, reviewing regulations related to data and digital services is necessary to support the CE transition [

43]. Additionally, digitalization can only be fully leveraged if accompanied by the development of appropriate skills [

78]. In parallel, establishing data standards and ensuring interoperability are key measures that can facilitate a digital ecosystem aligned with circular principles [

54].

4. Discussion

A significant share of the selected publications either focus explicitly on, or are situated within, the European context. This can be attributed to the pioneering role of the EU in shaping the CE agenda, marked by the publication of its first Circular Economy Action Plan in 2015—one of the earliest comprehensive policy frameworks on circularity globally. The adoption of a second, more ambitious Action Plan in 2020, which introduced a more diverse set of policy instruments, further reinforced the EU’s leadership in this domain. This institutional momentum is reflected in the temporal distribution of literature, with the majority of the reviewed studies published after 2020 and aligned with the evolving European policy landscape.

Building on the detailed analysis of the eight policy determinants presented in

Section 3, this discussion synthesizes key insights into an analytical framework (

Table 2) that captures the diversity and interdependence of policy instruments supporting CBM. The framework reveals that policy instruments rarely operate in isolation; rather, their effectiveness often depends on complementary measures across other determinants. For instance, regulatory instruments (

Section 3.3) tend to be more impactful when supported by information flows (

Section 3.6) and economic incentives (

Section 3.5). Information and cooperation (

Section 3.7) stand out as influential cross-cutting determinants. Their interplay is particularly relevant for enabling effective governance (

Section 3.2), as cooperative environments stimulate the circulation of knowledge and best practices, strengthening institutional learning, adaptability, and consensus-building. Information sharing among stakeholders not only supports coordinated action, but also underpins participatory governance processes, enabling adaptive and evidence-based decision-making. Also, technological advancements have positioned digitalization (

Section 3.8) as an additional cross-cutting enabler, capable of enhancing the effectiveness of all other determinants—from improving supply chain transparency and enabling data-driven policymaking to facilitating stakeholder engagement and service-based CBMs. Its integrative role amplifies the reach, responsiveness, and efficiency of policy instruments across the framework.

While the literature consistently acknowledges the importance of systemic approaches, the findings suggest that current policy frameworks often remain fragmented, with limited integration across governance levels and policy domains. A key insight is the central role of policy agenda and governance in shaping the effectiveness of all other determinants, with some of the most significant policy gaps and barriers originating in these domains. Two of the most prominent barriers identified are: (i) the lack of a stable, long-term policy vision combined with siloed governance structures, and (ii) the limited ambition in the design and enforcement of certain policy tools.

As highlighted in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2, the first barrier hinders the alignment of regulatory, fiscal, and informational instruments. The second is reflected in several ways. One is the uneven support for high-circularity strategies, such as product life extension and servitization. While economic incentives (

Section 3.5) and regulatory instruments (

Section 3.3) are increasingly deployed, they tend to favor lower R-strategies or focus on waste management. This bias reflects a broader issue in the policy agenda, where circularity is still predominantly framed through a linear lens. Moreover, the social dimension of circularity, including labor conditions, equity, and inclusiveness, remains underrepresented in most policy instruments, despite being critical for a just transition. Another example is GPP, which, despite its potential as a demand-side driver, remains largely voluntary and inconsistently implemented across jurisdictions. In Europe, the publication of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation establishes the first legal basis for the mandatory application of GPP criteria to certain product categories, representing a significant shift towards enforcement. However, its full implementation still depends on delegated acts yet to be published.

The fragmentation caused by siloed governance structures also manifests in the form of regulatory conflicts, which further undermine policy effectiveness. These conflicts involve multiple determinants, including agenda, governance, regulation, and cooperation. Beyond the examples previously discussed in

Section 3.2, the European context offers further illustrations: the Right to Repair Directive, hampered by weak regulation of anti-repair practices often justified by the protection of intellectual property rights [

100], and the increased circularity criteria in product design introduced by the ESPR, which contrasts with the continued waste-centric focus of the EPR scheme under the Waste Framework Directive [

13].

In response to these coordination gaps and regulatory conflicts, several authors emphasize the importance of ensuring coherence and complementarity among instruments through integrated policy mixes that combine regulatory, economic, and informational tools. This review highlights several examples proposed in the literature, involving instruments from distinct policy determinants—such as those suggested by [

6,

8,

9,

12,

40], who focused on PSS and repair activities (

Section 3.3). However, despite frequently outlined in theoretical frameworks, these policy mixes are rarely implemented in practice. Moreover, the lack of empirical evidence on their effectiveness constrains both their replicability and their scalability.

This limited implementation of integrated policy mixes suggests that addressing these challenges requires not so much the creation of new instruments, but rather the improved integration, coordination, and alignment of existing ones across policy determinants and governance levels. Cooperation and information (

Section 3.6 and

Section 3.7) emerge in the literature as critical yet underutilized levers. Participatory governance, structured cooperation models, and knowledge-sharing platforms are frequently highlighted as potential enablers, but these mechanisms are often ad hoc or confined to pilot initiatives, lacking institutionalization and long-term support.

These findings underscore the critical importance of fostering stakeholder collaboration across both horizontal and vertical governance dimensions. Horizontally, misalignments between economic, environmental, and industrial policies can compromise the systemic coherence required for effective CBM implementation. Vertically, the lack of coordination between EU-level directives and national or local execution strategies often results in inefficiencies and conflicting outcomes. Local governments, despite their proximity to socio-economic realities and their strategic position to catalyze service-based CBMs, are frequently overlooked and insufficiently empowered in terms of resources and institutional capacity. Several authors have proposed models to enhance stakeholder collaboration, particularly in addressing the complexity of multi-level governance. One such example is the “CE-centric quintuple-helix model” by [

4], which expands the traditional triad of academia, industry, and government to include civil society and the environmental dimension. This framework supports multilateral cooperation and long-term stakeholder engagement through inclusive, place-based strategies that reflect regional diversity and ecological priorities [

4].

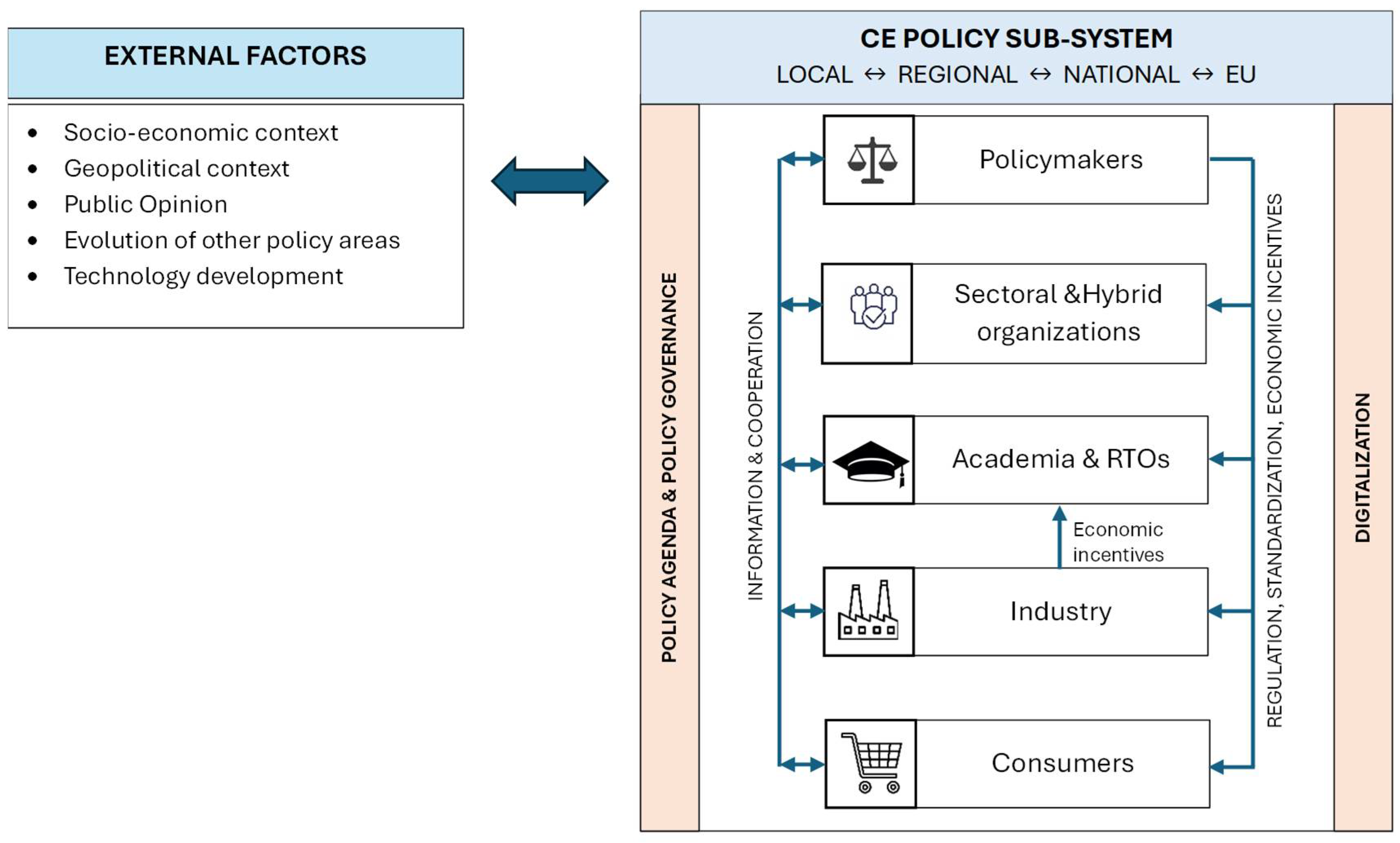

Drawing from the insights gathered in the literature review,

Figure 2 synthesizes the conceptual structure of the CE policy ecosystem, highlighting the dynamic interactions between key policy determinants and stakeholder groups. The diagram reflects the differentiated nature of policy implementation: while instruments such as regulation, standardization, and economic incentives typically follow top-down trajectories—often shaped through consultative processes with industry—determinants like information, dissemination and stakeholder cooperation require bidirectional engagement to ensure inclusivity, responsiveness, and systemic effectiveness.

Theoretical and practical implications

This review provides a structured and up-to-date understanding of the policy determinants and instruments currently supporting the implementation of CBMs. Its main theoretical contribution lies in the development of a novel analytical framework that guides scholars to assess the ambition, coherence, and interdependencies of CBM-supporting policies. By systematically organizing and interrelating instruments across eight determinants, this framework represents an added value for CBM-related literature, as it facilitates comparative analysis and helps identify systemic gaps that hinder circular transitions. In doing so, it offers a novel basis for future research to explore systemic interactions that have previously remained underexplored.

From a practical standpoint, the framework serves as a benchmarking tool to compare policy instruments across jurisdictions and governance levels. It enables policymakers to systematically assess whether all relevant determinants are addressed, identify gaps, and guide the design of integrated policy mixes. Moreover, it supports the development of statistical mapping of policy instruments, provided that a comparative base is established. In this regard, the framework offers a consistent structure for such comparisons, allowing for the quantification and visualization of policy coverage and interaction across regions.

Drawing on the literature and case examples discussed, three distinct but interconnected types of policy conflicts were identified: (i) legal conflicts, arising from contradictory or overlapping legislation; (ii) institutional conflicts, related to insufficient coordination among governance levels and involved entities; and (iii) fiscal/economic conflicts, resulting from misaligned economic incentives and disincentives. The analytical framework developed in this study provides policymakers with a structured overview of the key instruments that should be systematically addressed from the early stages of policy design to anticipate and mitigate potential conflicts, fostering more coherent and integrated CE policies.

Despite the slow progress of the circular transition reported by the Circularity Gap Report 2024, CE bottom-up initiatives are gaining momentum across diverse socio-economic and geographical contexts. It is therefore necessary to understand the success and failure factors associated with such movements. As noted by other authors, there is a need to gather empirical evidence from case studies in local contexts [

80,

101] and to define appropriate policy mixes that simultaneously target upstream and downstream factors influencing the decisions of different actors [

102]. The proposed analytical framework can support this effort in two key ways. First, it provides a structured basis to map empirical evidence on which policy instruments are most effective in specific contexts, enabling the identification of patterns and gaps across governance levels and sectors. Second, it can be enriched and refined through the integration of bottom-up insights, helping to bridge top-down policy design with local realities. By capturing both enabling and constraining factors, the framework facilitates the characterization of success and failure conditions for CBM implementation and supports the definition of tailored policy mixes aligned with particular CBMs and territorial dynamics.

Finally, the framework developed in this review explicitly addresses the need to leverage the social dimension of CE policies, as emphasized in recent literature. While the policy agenda should set the ambition to integrate social justice, decent labor conditions, and inclusivity into CBM adoption, this ambition must be operationalized across the remaining policy determinants. For example, regulatory instruments can include social clauses in public procurement and support a wider implementation of the “repair society” by facilitating the creation of jobs in repair, refurbishment, and reuse; economic incentives may prioritize funding for projects that promote reskilling and upskilling of workers affected by sectoral shifts; and information policies can support higher transparency on labor practices and social impacts. Additionally, by recognizing the role of social solidarity organizations that develop models based on repair, donation, and sharing, policymakers can draw on valuable grassroot experience to inform top-down strategies.

5. Conclusions

This review enabled a comprehensive and up-to-date analysis of the key policy determinants shaping the adoption of Circular Business Models (CBMs), organized into an analytical framework comprising eight interconnected pillars: Policy Agenda, Policy Governance, Regulation, Standardization, Economic Incentives, Information, Cooperation, and Digitalization.

Technological progress has made digitalization a foundational enabler of the circular transition. Advanced digital technologies—such as the Internet of Things (IoT), Industry 5.0, and Artificial Intelligence—are playing a central role in supporting the most ambitious circular strategies, such as refuse; in enabling CBM such as PSS; and in strengthening policy action across all determinant categories.

Despite the growing number of policy instruments supporting circularity, this study identified persistent gaps, particularly in the coordination across governance levels and in the integration of policy domains. More effective and even disruptive collaborative solutions between governments, academia, businesses, and civil society are needed to develop integrated and impactful policies that promote circularity across sectors.

This review offers several avenues for future research. Considering the influence of external factors on the design and implementation of CE policies, as well as the diversity of socio-economic and geopolitical contexts across jurisdictions and governance levels, the proposed analytical framework can serve as a structured basis for collecting empirical data. Such data can be used to assess and compare policy instruments through statistical analysis and benchmarking methodologies, enabling a clearer understanding of which policy determinants and instruments are most prevalent in specific contexts. Furthermore, future research could explore the dominant policy mixes and determinant configurations associated with different types of CBMs, contributing to more targeted and context-sensitive policy design. Future research could also apply this framework to systematically analyze the different types of policy conflicts in specific contexts and explore how different combinations of policy instruments may help prevent or resolve them in practice.

Amid the persistent policy gaps and barriers that may partly explain the slow pace of the circular transition, several successful case studies are emerging across diverse sectors and socio-economic contexts. Future research should investigate the origins of these bottom-up circular initiatives and, considering their specific characteristics—such as the type of CBM, the nature of the promoter, the stakeholders involved, and the geographical and political context—systematically identify and characterize the factors contributing to their success or failure. These insights should then be mapped onto the proposed analytical framework, with the aim of enriching it and informing both vertical and horizontal governance levels. Such an approach can offer valuable guidance for bridging top-down and bottom-up efforts, ultimately leading to more targeted, inclusive, and effective CE policies.

The authors acknowledge some limitations in this study. Firstly, there may have been bias in the selection of publications due to the use of predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. While the majority of industrial symbiosis publications focus primarily on waste management, excluding such publications may have led to overlooking some studies addressing asset or infrastructure sharing. Moreover, the review was based solely on two databases—Scopus and Web of Science—chosen for their prominence and wide coverage of indexed literature. Nonetheless, this may have led to the exclusion of relevant articles available in other databases. Therefore, this research can be further enriched in the future by comparing the results obtained with insights from additional databases and from technical or engineering studies. Additionally, while this study focused primarily on EU-centric publications and was restricted to English-language contributions, addressing these limitations and conducting similar research in other geographical contexts may produce different insights, offering a valuable avenue for future work. Despite these limitations, the diversity of sources—including reports from internationally recognized organizations—and the recency of the literature reviewed contribute to the relevance and timeliness of this analysis on policy determinants for circularity, a strategically vital paradigm for advancing climate neutrality and sustainability goals and, particularly in Europe, for reinforcing strategic autonomy in the current geopolitical context.