The Impact of Sustainable Aesthetics: A Qualitative Analysis of the Influence of Visual Design and Materiality of Green Products on Consumer Purchase Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Approach and Rationale

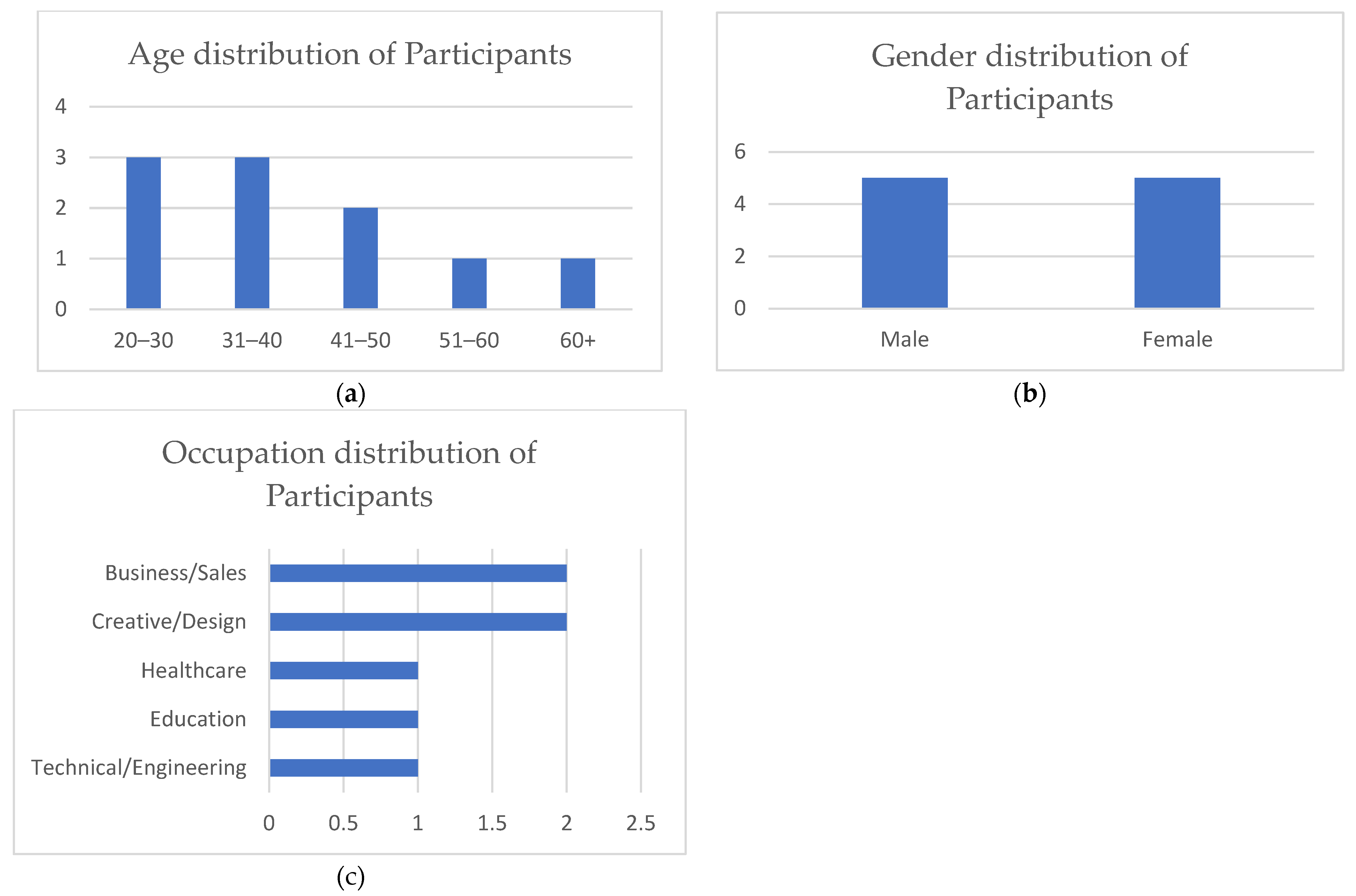

2.2. Sampling and Participant Profile

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

- Familiarization with the Data: The transcription was read and re-read multiple times by both authors to achieve a deep immersion in the content, noting initial ideas and potential patterns. This involved active reading, highlighting interesting statements, and jotting down preliminary thoughts in the margins.

- Initial Coding: In the first coding cycle, segments of the text (phrases, sentences, or paragraphs) were assigned initial codes that captured the essence of the participants’ statements. This was an open coding process, where codes were generated inductively from the data, without a pre-existing coding framework. For instance, statements like “looks primitive” or “clean, precise” were coded as ‘perception of industrial quality’, while “warm, organic” or “imperfection gives character” were coded as ‘appreciation of natural aesthetics’. These codes were noted directly on the transcripts or in separate documents.

- Generating Initial Themes: Codes were then grouped into potential themes based on their conceptual similarity and recurring patterns. This involved sorting and arranging the individual codes into broader categories. For example, codes related to ‘hygiene concerns about bamboo’, ‘preference for smooth surfaces’, and ‘association of plastic with medical standards’ began to coalesce into the broader theme of ‘Technical & Hygienic Paradigm’. Similarly, codes such as ‘aesthetic simplicity’, ‘authenticity of natural materials’, and ‘connection to nature’ grouped into the ‘Natural & Authentic Paradigm’. This was facilitated by using different colored highlighters, sticky notes, or tables to visually map relationships between codes.

- Reviewing Themes: These initial themes were then reviewed against the entire dataset to ensure they accurately reflected the meanings in the data and that no significant data was overlooked. This involved checking for internal homogeneity (data within a theme cohered meaningfully) and external heterogeneity (clear distinctions between themes). We refined the boundaries of each theme and considered whether any themes needed to be merged, split, or discarded.

- Defining and Naming Themes: Once validated, themes were refined, clearly defined, and given concise, descriptive names that captured their core essence. This led to the final three central themes presented in Section 3: “The Perceptual Dichotomy–‘Technical & Hygienic’ vs. ‘Natural & Authentic’,” “The Role of Haptic Experience as a Validation (or Invalidation) Factor,” and “The Premium Price–Justified as an ‘Ethical Tax’ or Rejected as a ‘Tax on Feelings’.”

- Producing the Report: The final stage involved selecting compelling illustrative quotes for each theme and weaving them into a coherent narrative that directly addressed the research question.

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: The Perceptual Dichotomy—“Technical & Hygienic” vs. “Natural & Authentic”

- The “Technical & Hygienic” Paradigm: A significant segment of participants, particularly those with a technical (P1-Engineer) or medical (P10-Physician) background, associated the conventional plastic product with positive values such as precision, hygiene, and safety.

“I choose the conventional toothbrush. The design is clean, precise, it looks like a medical, technological product. The other one, made of bamboo, looks... primitive.”(P1)

“The porous texture of the bamboo confirms my concern. How can it be cleaned effectively? Smooth, non-porous plastic is the standard in medicine for this exact reason.”(P10)

- The “Natural & Authentic” Paradigm: Another segment, often with a creative (P2-Architect, P5-Design Student) or ethically-oriented (P4-Teacher) profile, interpreted the same cues in the opposite way. The green product was associated with authenticity, warmth, and responsibility.

“I choose the bamboo toothbrush, without hesitation. It is elegant in its simplicity. The material is warm and has a visible texture. The other one is just a piece of plastic, visually noisy, generic.”(P2)

“I don’t care if it’s not perfectly smooth. The imperfection of the material gives it character.”(P4)

3.2. Theme 2: The Role of Haptic Experience as a Validation (Or Invalidation) Factor

- Confirmation: For participants who initially preferred the green product, the tactile sensation of the natural material amplified their preference.

“The sensation confirms my choice. The bamboo is light, warm, organic. It feels alive. The tactile connection with a natural material is much more pleasant.”(P2)

- Invalidation: For other participants, the haptic experience invalidated any initial visual curiosity.

“The plastic is solid, heavy, it feels well-made. The bamboo is too light, it seems fragile, like a toy.”(P3)

3.3. Theme 3: The Premium Price—Justified as an “Ethical Tax” or Rejected as a “Tax on Feelings”

- Acceptance as an “Ethical Tax” or “Investment in Values”: Participants oriented towards sustainability or aesthetics justified the price as a conscious payment for non-functional benefits.

“I feel like I am paying for the right choice. It’s a small price for a clearer conscience.”(P4)

“You are not just paying for the toothbrush, but to be part of an aesthetic ‘tribe’. It’s a statement piece.”(P5)

- Rejection as a “Tax on Feelings” or “Unjustified Marketing”: Participants with a pragmatic, technical, or economic worldview rejected the premium price in the absence of a demonstrable functional advantage.

“I would pay the higher price only if the producer gave me concrete data that the bamboo brush lasts 50% longer. Without such proof, it’s just a tax on feelings.”(P6)

“Why would I pay more for a product that looks cheaper and seems less durable? The value lies in the brand and the perception of a premium product.”(P3)

4. Discussion

4.1. There Is No Universal “Sustainable Aesthetic”

4.2. Positioning Against Existing Literature and Specific Contribution

4.3. Materiality as a Central Message

4.4. Beyond Visual and Haptic: The Auditory and Olfactory Signature of Sustainability

4.5. Implications for Design and Marketing

- 1.

- Segmentation based on values, not demographics: Companies should segment their audience not just by age or income, but by their value systems (e.g., “safety seekers,” “authenticity seekers,” “rational optimizers”).

- 2.

- Design as a coherent story: The visual aesthetics, materiality, packaging, and price must tell the same story. A bamboo toothbrush (authentic material) in a plastic blister pack (conventional packaging) creates a cognitive dissonance that undermines trust.

- 3.

- Educating the consumer through design: To overcome perceptual barriers (e.g., “bamboo = fragile”), design can incorporate elements that subtly communicate durability (e.g., a thicker cross-section, a metal reinforcing element) or hygiene (e.g., a protective cap, a visible certification).

4.6. Study Limitations

- Sampling Bias: While we employed purposive sampling to ensure a diversity of profiles, the recruitment process was non-random, and participants were self-selected. This means that individuals who chose to participate might have a pre-existing interest in sustainability or consumer products, potentially leading to a sample that is not entirely representative of the broader consumer base and thus potentially skewing the insights.

- Moderator Bias: Although active facilitation techniques were used to ensure balanced participation and minimize groupthink, the moderator’s presence, personality, and questioning style could subtly influence participants’ responses or guide the discussion in certain directions.

- Social Desirability Bias: Participants might have felt inclined to express more “pro-environmental” attitudes or preferences they perceived as socially acceptable, even if these did not perfectly align with their actual behaviors or privately held beliefs. The group setting of a focus group can sometimes amplify this effect, as individuals may conform to perceived group norms.

- Product Brand Influence: Another limitation is the use of products with well-known commercial brands (e.g., Colgate, Aquafresh). While our questions were formulated to focus explicitly on design attributes, we cannot completely rule out the confounding variable of brand loyalty or pre-existing perceptions associated with these brands. Future studies could benefit from using unbranded, neutral products to better isolate the pure impact of aesthetics and materiality.

5. Conclusions

- Quantitative Validation and Generalization: Future studies could quantitatively test the hypotheses generated here (e.g., the prevalence of the “Technical & Hygienic” vs. “Natural & Authentic” paradigms) on larger, statistically representative samples across different demographics, thereby assessing the generalizability of our findings.

- Cross-Cultural Comparative Studies: Since this study was conducted within a specific Romanian context, it would be crucial to investigate the perceptual dichotomy and associated value systems across diverse cultural contexts (e.g., Western Europe, Asia, North America). Such studies could determine whether these aesthetic preferences are universal or culturally specific, and how they impact purchase intention.

- Multi-Sensory Product Experience: Beyond visual and haptic cues, future research should systematically examine the role of auditory (e.g., packaging or product-use sounds) and olfactory (e.g., natural material scents, absence of artificial smell) stimuli in shaping consumer perceptions of sustainable products. Experimental designs that isolate and measure the impact of each sensory dimension would be especially valuable.

- Longitudinal Studies on Product Adoption: Exploring how initial sensory perceptions translate into long-term adoption and loyalty to sustainable alternatives would provide important insights into consumer habit formation and the sustained influence of design.

- Targeted Design Interventions: Applied research could focus on developing and testing specific design interventions (e.g., incorporating visual cues of hygiene into natural products, or tactile elements that convey durability) to bridge the perceptual gap between ethical intent and consumer acceptance, tailored to different consumer segments.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. A New Circular Economy Action Plan for a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe; COM (2020) 98 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0098 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product Design and Business Model Strategies for a Circular Economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.R.; Smith, J.S.; Andrews, D.; Cronin, J.J., Jr. Against the Green: A Multi-Method Examination of the Barriers to Green Consumption. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kim, T.-H.; Lee, M.-J. The Impact of Green Perceived Value Through Green New Products on Purchase Intention: Brand Attitudes, Brand Trust, and Digital Customer Engagement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C.; Wölfing Kast, S. Promoting Sustainable Consumption: Determinants of Green Purchases by Swiss Consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 883–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picket-Baker, J.; Ozaki, R. Pro-Environmental Products: Marketing Influence on Consumer Purchase Decision. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.S.; Dick, A.S.; Jain, A.K. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cue Effects on Perceptions of Store Brand Quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.H. Seeking the Ideal Form: Product Design and Consumer Response. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond Ecolabels: What Green Marketing Can Learn from Conventional Marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, Y. Who Is Buying Green Products? The Roles of Sustainability Awareness and Brand Trust. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Iraldo, F.; Vaccari, A.; Ferrari, E. Why Eco-Labels Can Be Effective Marketing Tools: A Case Study on the European Ecolabel. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, P. Design Aesthetics: Principles of Pleasure in Design. Psychol. Sci. 2006, 48, 157–172. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/26514491_Design_aesthetics_Principles_of_pleasure_in_design (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Karana, E.; Hekkert, P.; Kandachar, P. Material Considerations in Product Design: A Guide for Selecting Materials for Product Experience. In Materials Experience; Karana, E., Pedgley, O., Rognoli, V., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Childers, T.L. To Have and to Hold: The Influence of Haptic Information on Product Judgments. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M. Exploring the Impact of Sustainability Trade-Offs: The Role of Conditional Morality in Sustainable Consumption. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2024, 37, 702–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, M.G.; Swan, K.S.; Creusen, M.E.H. The Sustainable Product-Service System Preference Paradox: The Role of Perceived Diagnosticity of Sustainability Information. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 284–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S. Aesthetics of Sustainability: Research on the Design Strategies for Emotionally Durable Visual Communication Design. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A.; Casey, M.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://books.google.ro/books?id=tXpZDwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=ro#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Steenis, N.D.; van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.A.; Ligthart, T.N.; van Trijp, H.C.M. Consumer Response to Different Designs of Sustainable Food Packaging. Appetite 2017, 118, 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancer, E.; McShane, L.; Noseworthy, T.J. The Unfilled Promise of Sustainable Packaging. J. Assoc. Consum. Res. 2017, 2, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Wang, Q. Sensory Expectations Elicited by the Sounds of Opening the Packaging and Pouring a Beverage. Flavour 2015, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. An Integrative Review of Sensory Marketing: Engaging the Senses to Affect Perception, Judgment and Behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Code | Gender | Age | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Male | 32 | Software Engineer |

| P2 | Female | 28 | Architect |

| P3 | Male | 45 | Sales Manager |

| P4 | Female | 38 | Teacher |

| P5 | Male | 22 | Design Student |

| P6 | Male | 51 | Accountant |

| P7 | Female | 30 | Environmental Activist |

| P8 | Female | 68 | Retired |

| P9 | Male | 41 | Entrepreneur |

| P10 | Female | 44 | Doctor |

| Protocol Phase | Key Participant Activity | Main Finding Derived from Data | Representative Quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Visual Evaluation | Choosing the preferred product based solely on visual observation from a distance. | Two opposing aesthetic paradigms emerged: some preferred the “high-tech” look of plastic, others the “natural” aesthetic of bamboo. | P1 (Engineer): “I choose the conventional toothbrush. The design is clean, precise, it looks like a medical product.”/P2 (Architect): “I choose the bamboo toothbrush without hesitation. It’s elegant in its simplicity.” |

| II. Tactile (Haptic) Evaluation | Physically handling both products and describing sensations. | The tactile experience generally confirmed the initial visual preference: plastic was associated with “solidity,” bamboo with “warmth” and “authenticity.” | P3 (Sales Manager): “Plastic is solid, heavy, gives the feeling that it’s well-made. Bamboo is too light, seems fragile. My preference is reinforced.”/P2 (Architect): “The feeling confirms my choice. Bamboo feels alive. Plastic is cold, lifeless.” |

| III. Contextual Evaluation (Price) | Making a final purchase decision in a scenario where the eco product has a premium price (+50%). | Willingness to pay the premium was fragmented and dependent on individual value systems (ethical, aesthetic, functional, or safety considerations). | P4 (Teacher): “[I would pay extra because] I feel I’m making the right choice.”/P6 (Accountant): “[I would pay extra] only if I had concrete data that it lasts 50% longer. Otherwise, it feels like a tax on emotions.” |

| Observed Design Attribute | “Technical & Hygienic” Paradigm (Negative Interpretation of the Eco Product) | “Natural & Authentic” Paradigm (Positive Interpretation of the Eco Product) |

|---|---|---|

| Material (Bamboo vs. Plastic) | Interpretation: The natural material is perceived as unhygienic, fragile, and low-quality. Participant example: P10 (Doctor): “The porous texture of bamboo confirms my concern. How do you clean it properly? Smooth plastic is the medical standard.” | Interpretation: The natural material is perceived as authentic, pleasant to the senses, and responsible. Participant example: P2 (Architect): “The feeling confirms my choice. Bamboo is light, warm, organic. It feels alive. Plastic is cold, lifeless, inert.” |

| Overall Aesthetics (Minimalist vs. Complex) | Interpretation: The minimalist design of the eco product signals amateurism and lack of technology. Participant example: P1 (Engineer): “The [conventional] design is clean, precise, looks like a medical product. The bamboo one looks… primitive.” | Interpretation: The minimalist design of the eco product signals elegance, honesty, and alignment with current trends. Participant example: P5 (Design Student): “It’s much more on-trend. Minimalist aesthetics, natural material–everything communicates a modern, conscious lifestyle.” |

| Packaging (Cardboard vs. Plastic Blister) | Interpretation: Simple cardboard packaging is seen as cheap and unprotected. Participant example: P3 (Sales Manager): “In its cardboard box, it looks like something sold at a market. The sealed one seems from a big, serious company.” | Interpretation: Cardboard packaging is a strong, direct signal of the brand’s environmental responsibility. Participant example: P4 (Teacher): “The cardboard packaging immediately tells me the producer considered environmental impact. It’s a sign of respect.” |

| Finish and Weight (Imperfect vs. Perfect) | Interpretation: Low weight and small imperfections of the natural material indicate fragility and lack of quality control. Participant example: P6 (Accountant): “Bamboo is very light, which reinforces my impression that it’s not durable. I would always be careful not to break it.” | Interpretation: Low weight and imperfections are reframed as signs of uniqueness and authenticity. Participant example: P4 (Teacher): “I don’t mind if it’s not perfectly smooth. The material’s imperfection gives it character.” |

| Familiarity of Design (New vs. Known) | Interpretation: The unfamiliar design of the eco product generates skepticism and is perceived as a risk. Participant example: P8 (Retired): “This blue one (plastic). I recognize it. That’s what a toothbrush looks like. The wooden one… it’s strange. I stick with what I know.” | Interpretation: The new design of the eco product is a desirable differentiator, an escape from the banality of mass-market products. Participant example: P2 (Architect): “The other one is just a piece of plastic, visually noisy, generic.” |

| Participant Profile (Archetype) | Acceptance/Rejection of Premium Price | Main Reasoning (Illustrative Quote) | Analytical Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical Consumer (P4) | Acceptance | “I feel I’m paying for the right choice. It’s a small price for a more peaceful conscience.” | The price is a voluntary “ethical tax,” a payment for alignment with personal values. |

| Aesthetic Consumer (P2, P5) | Acceptance | “I pay for design, for the material, and for the pleasant feeling. It’s an investment in an object that brings me aesthetic joy.” | The price is a payment for a superior sensory experience and membership in an aesthetic “tribe.” |

| Pragmatic Consumer (P1, P6) | Rejection | “Why would I pay more for a product that seems less durable? I would only pay if it were proven to last longer.” | The price is accepted only if it justifies a quantifiable functional or durability advantage (return on investment). |

| Skeptical/Safety-Oriented Consumer (P10) | Conditional Rejection | “I would only pay if the manufacturer presented studies showing bamboo has superior antibacterial properties. Without evidence, it’s a risk.” | The price is accepted only if supported by scientific evidence that mitigates perceived risk (hygienic/medical). |

| Traditionalist Consumer (P8) | Rejection | “Never! Why pay more for something strange that may not even be good? It’s a scam.” | The premium price for an unfamiliar product is perceived as deceitful, lacking any trust basis. |

| Status-Oriented Consumer (P3, P9) | Rejection | “Value lies in the brand and perception of a premium product, and the bamboo toothbrush has none of that.” | The premium price is accepted only for well-known brands. For new products, it is rejected if not supported by status signals. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicolau, A.-M.; Petcu, P. The Impact of Sustainable Aesthetics: A Qualitative Analysis of the Influence of Visual Design and Materiality of Green Products on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9082. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209082

Nicolau A-M, Petcu P. The Impact of Sustainable Aesthetics: A Qualitative Analysis of the Influence of Visual Design and Materiality of Green Products on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9082. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209082

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicolau, Ana-Maria, and Petruţa Petcu. 2025. "The Impact of Sustainable Aesthetics: A Qualitative Analysis of the Influence of Visual Design and Materiality of Green Products on Consumer Purchase Intention" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9082. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209082

APA StyleNicolau, A.-M., & Petcu, P. (2025). The Impact of Sustainable Aesthetics: A Qualitative Analysis of the Influence of Visual Design and Materiality of Green Products on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability, 17(20), 9082. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209082