Risk Aversion Mediates the Impact of Environmental Change Perceptions on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies: A PLS-SEM Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

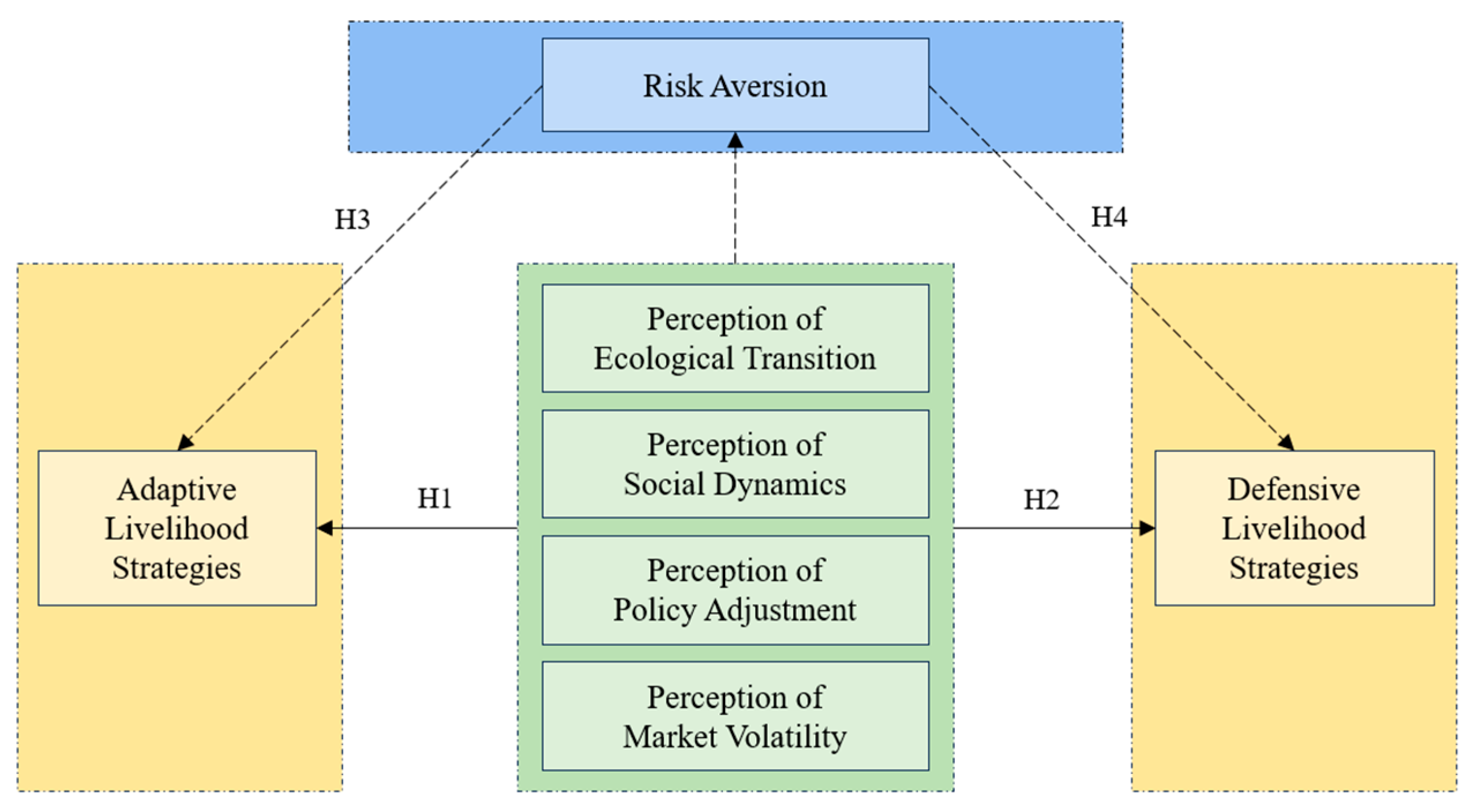

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies

2.2. Effects of Environmental Change Perception on Livelihood Strategies

2.3. Mediating Role of Risk Aversion

2.4. Theoretical Model

3. Data Sources and Methodology

3.1. Research Area

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Methodology and Measures of Variables

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

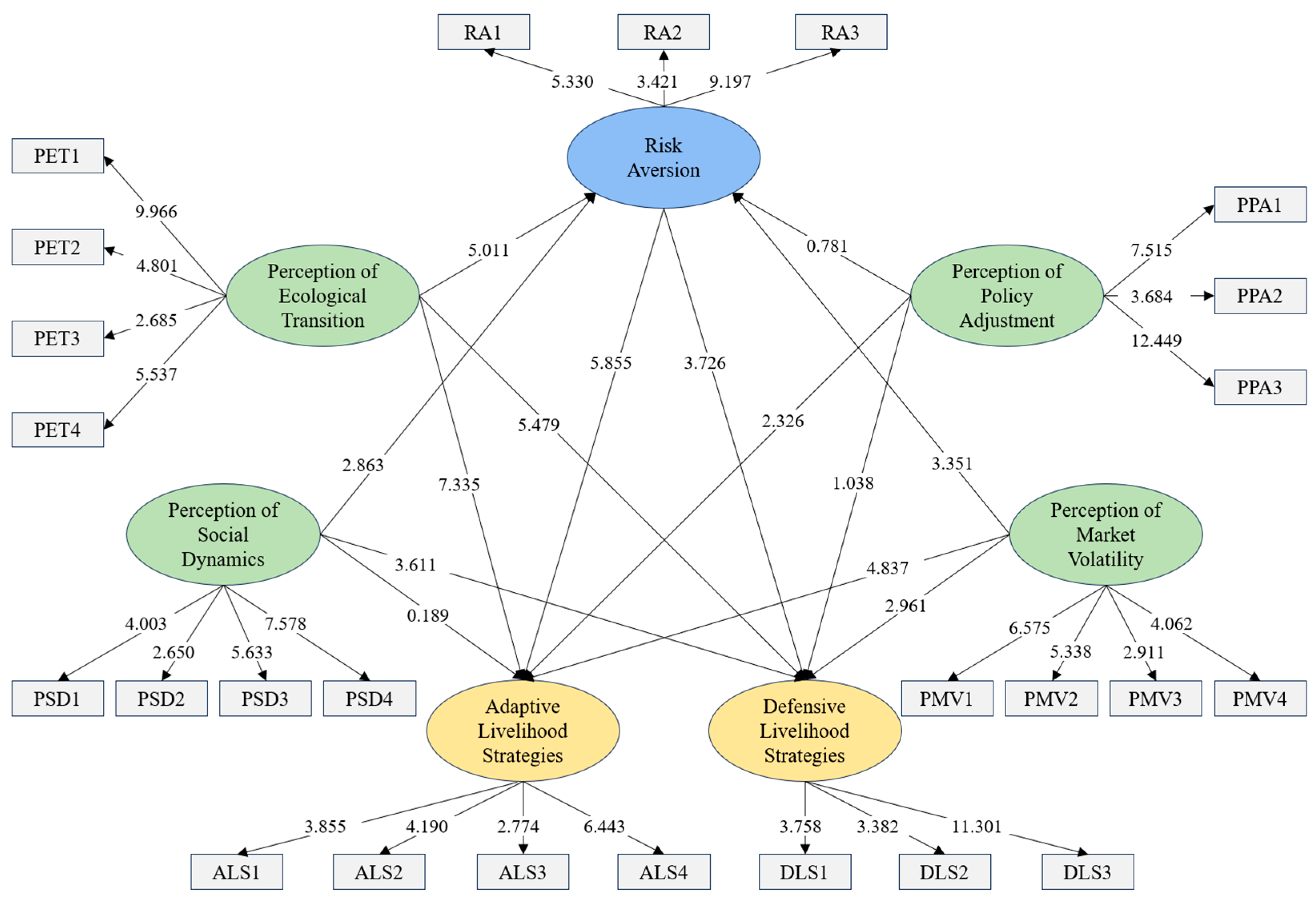

4.1. Measurement Model Assessment

4.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion

5.1. Perception of Environmental Change as a Key Driver of Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies

5.2. Risk Aversion as a Mediator in the Impact of Environmental Perception on Livelihood Strategies

5.3. Structural Differences Among Perception Dimensions Reveal Policy Bottlenecks

5.4. Coexistence of Adaptive and Defensive Livelihood Strategies: Mixed Behavioral Choices

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Policy Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Scope of Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iagăru, R.; Concioiu, N.; Șipoș, A.; Iagăru, P.; Băluță, A.D.; Vasile, A. Strategic Approaches to Sustainable Rural Development by Harnessing Endogenous Resources to Improve Residents’ Quality of Life. Land 2012, 14, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.; Muhammed, S.E.; Milne, A.E.; Todman, L.C.; Dailey, A.G.; Glendining, M.J.; Whitmore, A.P. The landscape model: A model for exploring trade-offs between agricultural production and the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 1483–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bretagnolle, V.; Berthet, E.; Gross, N.; Gauffre, B.; Plumejeaud, C.; Houte, S.; Badenhausser, I.; Monceau, K.; Allier, F.; Monestiez, P.; et al. Towards sustainable and multifunctional agriculture in farmland landscapes: Lessons from the integrative approach of a French LTSER platform. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birthal, P.S.; Hazrana, J.; Negi, D.S. Effectiveness of farmers’ risk management strategies in smallholder agriculture: Evidence from India. Clim. Change 2021, 169, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xie, M.; Xu, G. Sustainable livelihood evaluation and influencing factors of rural households: A case study of Beijing ecological conservation areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnani, T.; Gotor, E.; Caracciolo, F. Adaptive strategies enhance smallholders’ livelihood resilience in Bihar, India. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengochea, P.D.; Henderson, K.; Loreau, M. Habitat percolation transition undermines sustainability in social-ecological agricultural systems. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ahmed, T. Farmers’ livelihood capital and its impact on sustainable livelihood strategies: Evidence from the poverty-stricken areas of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Zhong, K. Driving mechanism of subjective cognition on farmers’ adoption behavior of straw returning technology: Evidence from rice and wheat producing provinces in China. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 922889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi-Khalkheili, T.; Aenis, T.; Menatizadeh, M.; Zamani, G. Farmers’ decision-making process under climate change: Developing a conceptual framework. Int. J. Agric. Manag. Dev. 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Fierros-González, I.; López-Feldman, A. Farmers’ perception of climate change: A review of the literature for Latin America. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 672399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Sustainable Development Through the Lens of Climate Change: A Diagnosis of Attitudes in Southeastern Rural Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xing, F.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Y. The impact of livelihood resilience and climate change perception on farmers’ climate change adaptation behavior decision. For. Econ. Rev. 2024, 6, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickson, R.B.; He, G. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions, adaptation constraints, and determinants of adaptive capacity to climate change in Chengdu. Sage Open 2021, 11, 21582440211032638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Nie, F. The role of social capital in the impact of multiple shocks on households’ coping strategies in underdeveloped rural areas. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manlos, A.O. Operationalizing agency in livelihoods research: Smallholder farming livelihoods in southwest Ethiopia. Ecol. Soc. 2022, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Zhou, L.; Wen, Y.; Chen, Y. Farmers’ adaptability to the policy of ecological protection in China—A case study in Yanchi County, China. Soc. Sci. J. 2018, 55, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, A.C.D.; Schmitt-Filho, A.L.; Farley, J.; Fantini, A.C.; Longo, C. Farmer perceptions, policy and reforestation in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.A. The pass-through of international commodity price shocks to producers’ welfare: Evidence from Ethiopian coffee farmers. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2022, 36, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, T.T.; Brewer, T.; Luck, J.; Zander, K. A global review of farmers’ perceptions of agricultural risks and risk management strategies. Agriculture 2019, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Montenegro, J.; Minchala-Santander, R.; Faytong-Haro, M. Risk perception and management strategies among Ecuadorian cocoa farmers: A comprehensive analysis of attitudes and decisions. Agriculture 2025, 15, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Jin, J.; Kuang, F.; Zhang, C.; Guan, T. Farmers’ risk cognition, risk preferences and climate change adaptive behavior: A structural equation modeling approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanuarti, R.; Aji, J.M.M.; Rondhi, M. Risk aversion level influence on farmer’s decision to participate in crop insurance: A review. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, D.; Afzal, M.; Rauf, A. Environmental risks among rice farmers and factors influencing their risk perceptions and attitudes in Punjab, Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 21953–21964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Alharthi, M. The association between farmers’ psychological factors and their choice to adopt risk management strategies: The case of Pakistan. Agriculture 2022, 12, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainggolan, D.; Moeis, F.R.; Termansen, M. Does risk preference influence farm level adaptation strategies?—Survey evidence from Denmark. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2023, 28, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yue, W.; Feng, S.; Cai, J. Analysis of spatial heterogeneity of ecological security based on MCR model and ecological pattern optimization in the Yuexi county of the Dabie Mountain Area. J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 34, 771–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood strategies and dynamics in rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tittonell, P. Livelihood strategies, resilience and transformability in African agroecosystems. Agric. Syst. 2014, 126, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, W.; Xu, H. Deciphering the impacts of environmental perceptions on place attachment from the perspective of place of origin: A case study of rural China. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, L. Exploring the nexus between perceived ecosystem services and well-being of rural residents in a mountainous area, China. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 164, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Ehlers, M.H. Exploring farmers’ perceptions of social sustainability. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 27, 6371–6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Min, S.; Huang, J.; Waibel, H. Falling price induced diversification strategies and rural inequality: Evidence of smallholder rubber farmers. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Luo, X.; Song, J.; Fu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, W. Can environmental risk management improve the adaptability of farmer households’ livelihood strategies?—Evidence from Hubei Province, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 908913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Wreford, A.; Blackett, P.; Hall, D.; Woodward, A.; Awatere, S.; Livingston, M.E.; Macinnis-Ng, C.; Walker, S.; Dountain, J.; et al. Climate change adaptation through an integrative lens in Aotearoa New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2024, 54, 491–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Zhao, W.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y. How environmental leadership shapes green innovation performance: A resource-based view. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.A.; Jinac, A.S.; Jain, M.; Kristjanson, P.; DeFries, R.S. Smallholder farmer cropping decisions related to climate variability across multiple regions. Glob. Environ. Change Hum. Policy Dimens. 2014, 25, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Xuhong, T.; Wan, X.; He, R.; Kuang, F.; Ning, J. Farmers’ risk aversion, loss aversion and climate change adaptation strategies in Wushen Banner, China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2593–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Zhao, X. Risk perception, risk preference, and timing of food sales: New insights into farmers’ negativity in China. Foods 2024, 13, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, N.; Chang, L.; Guo, R.; Wu, B. The effect of health on the elderly’s labor supply in rural China: Simultaneous equation models with binary, ordered, and censored variables. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 890374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.T.; Zhou, Y.D.; Cai, J.L. Effects of health status on the labor supply of older adults with different socioeconomic status. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.; O’Shea, E.; Scharf, T. Rural old-age social exclusion: A conceptual framework on mediators of exclusion across the lifecycle. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 2311–2337. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, L.; McKee, K.J. Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2018, 79, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, S.; Lu, S.; Wang, T.; Xu, X. The effect of farmers’ livelihood capital on non-agricultural income based on the regulatory effect of returning farmland to forests: A case study of Qingyuan Manchu Autonomous County in China. Small-Scale For. 2024, 23, 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hunecke, C.; Engler, A.; Jara-Rojas, R.; Poortvliet, P.M. Understanding the role of social capital in adoption decisions: An application to irrigation technology. Agric. Syst. 2017, 153, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zheng, H. How social capital affects willingness of farmers to accept low-carbon agricultural technology (LAT)? A case study of Jiangsu, China. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2021, 13, 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Y. Towards sustainable development: Understanding resilience capacity and well-being of rural households in the Dabie Mountainous Area, China. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 13673–13721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Parga-Montoya, N.; Lozano-Garcia, J.J.; Huerta-Mascotte, E. Determinants of openness activities in innovation: The mediating effect of absorptive capacity. J. Innov. Knowledg. 2023, 8, 100432. [Google Scholar]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.; Fayyad, S. Green human resources and innovative performance in small-and medium-sized tourism enterprises: A mediation model using PLS-SEM data analysis. Mathematics 2023, 11, 711. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Basak, D.; Bose, A.; Chowdhury, I.R. Citizens’ perception towards landfill exposure and its associated health effects: A PLS-SEM based modeling approach. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saari, U.A.; Damberg, S.; Frömbling, L.; Ringle, C.M. Sustainable consumption behavior of Europeans: The influence of environmental knowledge and risk perception on environmental concern and behavioral intention. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 189, 107155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahar, N.; Hossain, Z.; Mahiuddin, S. Assessment of the environmental perceptions, attitudes, and awareness of city dwellers regarding sustainable urban environmental management: A case study of Dhaka, Bangladesh. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 7503–7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Hou, C.X.; Lu, H.L. Analysis of farmer’s social capital characteristics in Tibetan area: A case study in Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2012, 22, 101–107. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Baffoe, G.; Matsuda, H. A perception based estimation of the ecological impacts of livelihood activities: The case of rural Ghana. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Pu, Y. Land property rights, social trust, and non-agricultural employment: An interactive study of formal and informal institutions in China. Land 2025, 14, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niles, M.T.; Lubell, M.; Haden, V.R. Perceptions and responses to climate policy risks among California farmers. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1752–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröner, L.; van Grinsven, H.J.M.; Erisman, J.W.; Graversgaard, M.; Immerzeel, T.; Olesen, J.E.; Rodríguez, A.; Soriano, B.; Sanz-Cobena, A.; van der Lippe, T. Climate change skepticism of European farmers and implications for effective policy actions. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menapace, L.; Colson, G.; Raffaelli, R. Risk aversion, subjective beliefs, and farmer risk management strategies. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 95, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jianjun, J.; Yiwei, G.; Xiaomin, W.; Nam, P.K. Farmers’ risk preferences and their climate change adaptation strategies in the Yongqiao District, China. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Zobeidi, T.; Warner, L.A.; Löhr, K.; Lamm, A.; Sieber, S. Shaping farmers’ beliefs, risk perception and adaptation response through Construct Level Theory in the Southwest Iran. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burnham, M.; Ma, Z. Multi-scalar pathways to smallholder adaptation. World Dev. 2018, 108, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringer, L.C.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Harris, D.; Lyon, C.; Pereira, L.; Ward, C.F.M.; Simelton, E. Adaptation and development pathways for different types of farmers. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 104, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Nayak, N.C.; Mohanty, W.K. Choices between adaptation and coping strategies as responses to cyclonic shocks and their impact on household welfare in villages on the east coast of India. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 94, 103834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Frequency (N = 322) | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 140 | 43.48 |

| Famale | 182 | 56.52 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Less than 30 | 11 | 3.42 |

| From 30 to less than 45 | 37 | 11.49 |

| From 45 to less than 60 | 166 | 51.55 |

| 60 and over | 108 | 33.54 |

| Education (years) | ||

| Less than 7 | 183 | 56.83 |

| From 7 to less than 10 | 87 | 27.02 |

| From 10 to less than 13 | 33 | 10.25 |

| 13 and over | 19 | 5.90 |

| Income (Yuan) | ||

| Less than 12,000 | 17 | 5.28 |

| From 12,000 to less than 27,000 | 192 | 59.63 |

| From 27,000 to less than 50,000 | 88 | 27.33 |

| 50,000 and over | 25 | 7.76 |

| Index | Latent Variable | Observed Indicators | Statements | Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perception of Environmental Change | Perception of Ecological Transition | PET1 | Soil fertility in your area has gradually declined. | Values 1–5, the higher the value, the higher the level of agreement with the statement |

| PET2 | The quality of rural water sources (wells, rivers, etc.) is worse than in the past. | |||

| PET3 | The variety and number of wild plants and animals have significantly decreased. | |||

| PET4 | Extreme weather events (e.g., heavy rain, droughts, strong winds) occur more frequently. | |||

| Perception of Social Dynamics | PSD1 | Communication and visits among villagers have decreased compared with the past. | ||

| PSD2 | Participation in village public affairs has declined. | |||

| PSD3 | Mutual help among villagers has decreased compared with the past. | |||

| PSD4 | Villagers are less willing to entrust private matters to their neighbors. | |||

| Perception of Policy Adjustment | PPA1 | Agricultural subsidies provide limited support for your farming activities. | ||

| PPA2 | Ecological protection policies impose more restrictions on your agricultural production than in the past. | |||

| PPA3 | The coverage of medical and pension insurance is limited. | |||

| Perception of Market Volatility | PMV1 | The price volatility of major agricultural products has increased significantly. | ||

| PMV2 | It has become more difficult to obtain reliable sales information. | |||

| PMV3 | The competition for agricultural products in local markets has become more intense. | |||

| PMV4 | The costs of agricultural inputs have increased operational pressure. | |||

| Risk Aversion | Risk Aversion | RA1 | Household income is highly uncertain and difficult to maintain consistently. | |

| RA2 | Health problems or medical expenses may weaken household labor capacity and create a heavy financial burden. | |||

| RA3 | The household is easily overlooked or marginalized in accessing resources and participating in village affairs. | |||

| Livelihood Strategies | Adaptive Livelihood Strategies | ALS1 | Have you adjusted your crop structure in recent years? | Yes = 1, No = 0 |

| ALS2 | Have you adopted new agricultural technologies? | |||

| ALS3 | Have you purchased agricultural insurance? | |||

| ALS4 | Have you engaged in livestock raising or other non-crop activities? | |||

| Defensive Livelihood Strategies | DLS1 | Have you reduced your agricultural investment? | ||

| DLS2 | Have you relocated household labor to non-farm employment or migrant work? | |||

| DLS3 | Have you relied on social support (such as assistance from relatives, government, or the village collective)? |

| Variables | Observed Indicators | Outer Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (rho_c) | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended values | >0.7 | >0.7 | >0.6 | >0.5 | <3.0 | |

| Perception of Ecological Transition | 0.875 | 0.787 | 0.649 | |||

| PET1 | 0.818 | 1.840 | ||||

| PET2 | 0.855 | 2.737 | ||||

| PET3 | 0.779 | 1.835 | ||||

| PET4 | 0.814 | 1.699 | ||||

| Perception of Social Dynamics | 0.787 | 0.684 | 0.712 | |||

| PSD1 | 0.773 | 1.805 | ||||

| PSD2 | 0.911 | 1.948 | ||||

| PSD3 | 0.883 | 1.663 | ||||

| PSD4 | 0.828 | 1.791 | ||||

| Perception of Policy Adjustment | 0.804 | 0.722 | 0.594 | |||

| PPA1 | 0.755 | 2.028 | ||||

| PPA2 | 0.797 | 1.844 | ||||

| PPA3 | 0.843 | 1.830 | ||||

| Perception of Market Volatility | 0.759 | 0.728 | 0.716 | |||

| PMV1 | 0.854 | 1.743 | ||||

| PMV2 | 0.811 | 1.679 | ||||

| PMV3 | 0.851 | 2.530 | ||||

| PMV4 | 0.795 | 1.955 | ||||

| Risk Aversion | 0.819 | 0.826 | 0.745 | |||

| RA1 | 0.833 | 1.946 | ||||

| RA2 | 0.901 | 1.849 | ||||

| RA3 | 0.874 | 1.804 | ||||

| Adaptive Livelihood Strategies | 0.796 | 0.871 | 0.694 | |||

| ALS1 | 0.853 | 2.488 | ||||

| ALS2 | 0.835 | 2.016 | ||||

| ALS3 | 0.802 | 1.768 | ||||

| ALS4 | 0.757 | 1.887 | ||||

| Defensive Livelihood Strategies | 0.866 | 0.735 | 0.661 | |||

| DLS1 | 0.766 | 1.694 | ||||

| DLS2 | 0.793 | 1.845 | ||||

| DLS3 | 0.837 | 1.837 | ||||

| PET | PSD | PPA | PMV | RA | ALS | DSL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET | |||||||

| PSD | 0.366 | ||||||

| PPA | 0.195 | 0.291 | |||||

| PMV | 0.278 | 0.296 | 0.421 | ||||

| RA | 0.428 | 0.185 | 0.358 | 0.622 | |||

| ALS | 0.365 | 0.433 | 0.644 | 0.447 | 0.370 | ||

| DLS | 0.280 | 0.377 | 0.506 | 0.288 | 0.259 | 0.588 |

| R2 | Q2 | |

|---|---|---|

| PET | 0.691 | 0.457 |

| PSD | 0.474 | 0.322 |

| PPA | 0.346 | 0.195 |

| PMV | 0.454 | 0.310 |

| RA | 0.399 | 0.202 |

| ALS | 0.423 | 0.278 |

| DLS | 0.538 | 0.325 |

| Hypothesis | Paths | Standardized Coefficient β | T Statistics | p Value | 95% Confidence Interval | f2 | VAF% | Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5 | 95% | ||||||||

| Direct effect | |||||||||

| H1a | PET→ALS | 0.422 | 7.335 | <0.001 | 0.292 | 0.517 | 0.041 | N/A | Supported |

| H1b | PSD→ALS | 0.188 | 0.189 | >0.05 | −0.106 | 0.385 | 0.028 | N/A | Not supported |

| H1c | PPA→ALS | 0.271 | 2.326 | <0.05 | 0.074 | 0.319 | 0.206 | N/A | Supported |

| H1d | PMV→ALS | 0.266 | 4.837 | <0.001 | 0.167 | 0.394 | 0.133 | N/A | Supported |

| H2a | PET→DLS | 0.257 | 5.479 | <0.001 | 0.162 | 0.381 | 0.107 | N/A | Supported |

| H2b | PSD→DLS | 0.206 | 3.611 | <0.001 | 0.007 | 0.278 | 0.119 | N/A | Supported |

| H2c | PPA→DLS | 0.112 | 1.038 | >0.05 | −0.128 | 0.326 | 0.074 | N/A | Not supported |

| H2d | PMV→DLS | 0.104 | 2.961 | <0.05 | 0.075 | 0.329 | 0.066 | N/A | Supported |

| RA→ALS | 0.506 | 5.855 | <0.001 | 0.399 | 0.553 | 0.273 | N/A | ||

| RA→DLS | 0.337 | 3.726 | <0.001 | 0.188 | 0.445 | 0.177 | N/A | ||

| PET→RA | 0.384 | 5.011 | <0.001 | 0.326 | 0.499 | 0.025 | N/A | ||

| PSD→RA | 0.264 | 2.863 | <0.001 | 0.155 | 0.372 | 0.155 | N/A | ||

| PPA→RA | 0.078 | 0.781 | >0.05 | −0.173 | 0.246 | 0.238 | N/A | ||

| PMV→RA | 0.252 | 3.531 | <0.001 | 0.112 | 0.358 | 0.113 | N/A | ||

| Indirect effect | |||||||||

| H3a | PET→RA→ALS | 0.194 | 7.635 | <0.001 | 0.028 | 0.251 | N/A | 31.494 | Supported |

| H3b | PSD→RA→ALS | 0.134 | 1.602 | >0.05 | −0.117 | 0.379 | N/A | N/A | Not supported |

| H3c | PPA→RA→ALS | 0.039 | 0.973 | >0.05 | −0.135 | 0.228 | N/A | N/A | Not supported |

| H3d | PMV→RA→ALS | 0.128 | 3.287 | <0.001 | 0.024 | 0.244 | N/A | 32.487 | Supported |

| H4a | PET→RA→DLS | 0.129 | 5.907 | <0.001 | 0.090 | 0.285 | N/A | 33.420 | Supported |

| H4b | PSD→RA→DLS | 0.089 | 3.136 | <0.05 | 0.009 | 0.205 | N/A | 30.169 | Supported |

| H4c | PPA→RA→DLS | 0.026 | 1.455 | >0.05 | −0.273 | 0.124 | N/A | N/A | Not supported |

| H4d | PMV→RA→DLS | 0.085 | 5.894 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.155 | N/A | 44.974 | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Wu, G. Risk Aversion Mediates the Impact of Environmental Change Perceptions on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies: A PLS-SEM Study. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209043

Wang G, Li Y, Wu G. Risk Aversion Mediates the Impact of Environmental Change Perceptions on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies: A PLS-SEM Study. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209043

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Guokui, Yangyang Li, and Guoqin Wu. 2025. "Risk Aversion Mediates the Impact of Environmental Change Perceptions on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies: A PLS-SEM Study" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209043

APA StyleWang, G., Li, Y., & Wu, G. (2025). Risk Aversion Mediates the Impact of Environmental Change Perceptions on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies: A PLS-SEM Study. Sustainability, 17(20), 9043. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209043