Innovation and Sustainability in the Value Chain of the Tourism Sector in Boyacá

Abstract

1. Introduction

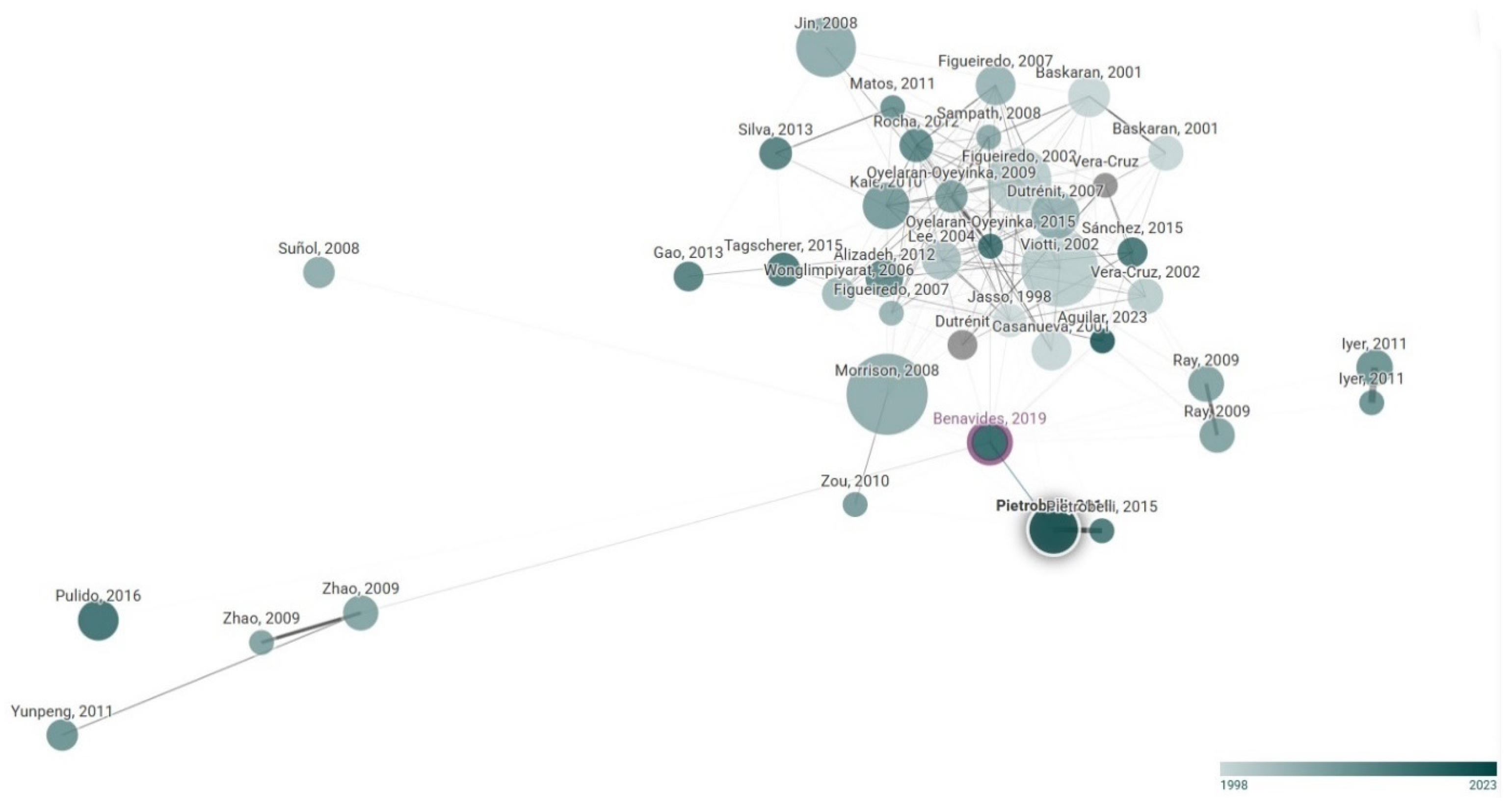

2. Literature Review

2.1. Innovation in Tourism

2.2. Tourism Value Chains and Sustainability

2.3. Innovation Models in Tourism

2.4. Research Gaps and Relevance to Boyacá

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Documentary Analysis

3.3. Semi-Structured Interviews

3.4. Validation and Triangulation

4. Results

4.1. Tourism Competitiveness

4.2. Stakeholder Collaboration

4.3. Promotional Strategies

4.4. Synthesis of Findings

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with International Experiences

5.2. Implementation Pathways for Stakeholders

- Public authorities must lead the design of governance platforms to coordinate actors, provide infrastructure investment, and promote regulatory frameworks that support sustainability.

- Entrepreneurs should invest in training and digital platforms, strengthening service quality and visibility on global booking systems.

- Communities must be actively engaged in co-designing authentic circuits that preserve cultural identity and ecological integrity.

5.3. Implications for Competitiveness and Sustainability

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UNAD | Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia |

| ECACEN | Escuela de Ciencias Administrativas, Contables, Económicas y de Negocios |

| ICTs | Information and Communication Technologies |

| CEI-UNAD | Comité de Ética de Investigación UNAD |

| CrediT | Contributor Roles Taxonomy |

| Q1/Q2 | Quartile classification of scientific journals in Scopus database |

References

- El Espectador. Boyacá Is the Department with the Most Municipalities Committed to Sustainable Tourism. El Espectador. 2023. Available online: https://www.elespectador.com (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Masuda, H.; Krizaj, D.; Sakamoto, H.; Nakamura, K. Approaches for Sustaining Cultural Resources by Adapting Diversified Contexts of Customers in Tourism: Comparison between Japanese and Slovenian Cases. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10371, pp. 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MINCIT. National Sustainable Tourism Policy; Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism of Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2021.

- World Travel Awards. South America’s Leading Destination 2025. Available online: https://www.worldtravelawards.com/award-south-americas-leading-destination-2025 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Booking.com. The Most Welcoming Regions on Earth 2025. Available online: https://www.booking.com (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Ritchie, J.R.B.; Crouch, G.I. The Competitive Destination: A Sustainable Tourism Perspective; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalager, A.M. A Review of Innovation Research in Tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey, M. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Who Owns Paradise? 2nd ed.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Morales, O.; Clarke, A. Sustainable Tourism Value Chain Analysis as a Tool to Evaluate Tourism’s Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals and Local Indigenous Communities. J. Ecotour. 2022, 21, 345–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, J.; Camargo, L. Rural Tourism and Local Development in Boyacá, Colombia. J. Reg. Urban Stud. 2020, 42, 45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in Information Technology and Tourism Management: 20 Years on and 10 Years after the Internet—The State of eTourism Research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Sigala, M.; Xiang, Z.; Koo, C. Smart Tourism: Foundations and Developments. Electron. Mark. 2015, 25, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zada, M.; Zada, S.; Dhar, B.K.; Ping, C.; Sarkar, S. Digital Leadership and Sustainable Development: Enhancing Firm Sustainability through Green Innovation and Top Management Innovativeness. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Good Practices in the Americas; World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.unwto.org (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Scheyvens, R. Tourism for Development: Empowering Communities; Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, B. The Linear Model of Innovation: The Historical Construction of an Analytical Framework. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2006, 31, 639–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, S.J.; Rosenberg, N. An Overview of Innovation. In The Positive Sum Strategy: Harnessing Technology for Economic Growth; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Leydesdorff, L. The Dynamics of Innovation: From National Systems and “Mode 2” to a Triple Helix of University–Industry–Government Relations. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, Clusters and Innovation in Tourism: A UK Experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Viruel, M.J.; Rueda-López, R. Theoretical Foundations of Social Innovation. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Públ. Soc. Coop. 2023, 108, 131–162. [Google Scholar]

- González, L. Sustainable Tourism in Boyacá: Challenges and Opportunities. J. Tour. Dev. 2020, 12, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori, A.; Teddlie, C. Mixed Methodology: Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- RAP-E Central Region. Boyacá, a Key Destination for Promoting Sustainable Tourism in Colombia. RAP-E. 2025. Available online: https://regioncentralrape.gov.co/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Hall, C.M.; Williams, A.M. Tourism and Innovation; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Barros, A.V.; Caballero-Granado, J.D.; Rolón-Rodríguez, B.M. Problems of Colombian Tourism. J. Res. Manag. 2023, 6, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- More Ferrando, A.; Ramón Rodríguez, A.B.; Aranda Cuéllar, P. The Digital Revolution in the Tourism Sector: An Opportunity for Tourism in Spain. Ekonomiaz 2020, 98, 228–251. [Google Scholar]

- Konishi, Y. Global Value Chain in Services: The Case of Tourism in Japan. J. Southeast Asian Econ. 2019, 36, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, B.B. Rural Marginalization and the Role of Social Innovation: A Turn Towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Evidence from Interviews (n = 50) | Supporting Documentary Data | Implications for Competitiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure | 64% reported poor road conditions; 52% insufficient lodging capacity | RAP-E (2025) tourism report [27] | Reduced accessibility and visitor retention |

| Service Quality | 70% cited lack of training; 42% limited foreign language skills | MINCIT (2021) plan [3] | Professionalization needed for international standards |

| Digitalization | 58% indicated minimal ICT use in promotion/booking | González (2020) [24] | Low visibility in global markets |

| Practice | Adoption Rate (n = 50) | Limitations Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Social media campaigns | 36% | Irregular, no unified branding |

| Participation in tourism fairs | 22% | Limited budgets, lack of coordination |

| Digital booking platforms | 18% | Low technological capacity of SMEs |

| Experiential marketing | 12% | Scattered, not part of destination strategy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berdugo Morantes, J.O.; Torres Zamudio, M.; Bonilla Gómez, F.A. Innovation and Sustainability in the Value Chain of the Tourism Sector in Boyacá. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209000

Berdugo Morantes JO, Torres Zamudio M, Bonilla Gómez FA. Innovation and Sustainability in the Value Chain of the Tourism Sector in Boyacá. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):9000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209000

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerdugo Morantes, Juan Orlando, Marleny Torres Zamudio, and Fabio Alonso Bonilla Gómez. 2025. "Innovation and Sustainability in the Value Chain of the Tourism Sector in Boyacá" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 9000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209000

APA StyleBerdugo Morantes, J. O., Torres Zamudio, M., & Bonilla Gómez, F. A. (2025). Innovation and Sustainability in the Value Chain of the Tourism Sector in Boyacá. Sustainability, 17(20), 9000. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17209000

_Li.png)