Assessment and Protection of Heritage Value of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Huaqiu Village

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can the HUL approach be adapted to rural contexts to effectively analyze the spatiotemporal evolution of traditional village landscapes?

- Based on the HUL framework’s holistic cognition of heritage value, how can you systematically assess the heritage values of traditional villages and reveal their intrinsic coupling relationships?

- What practical pathways can be constructed to implement the HUL’s core principles in rural areas, to realize the living inheritance of rural heritage?

2. Village Heritage Preservation and Historic Urban Landscape Approach

3. Materials and Methods

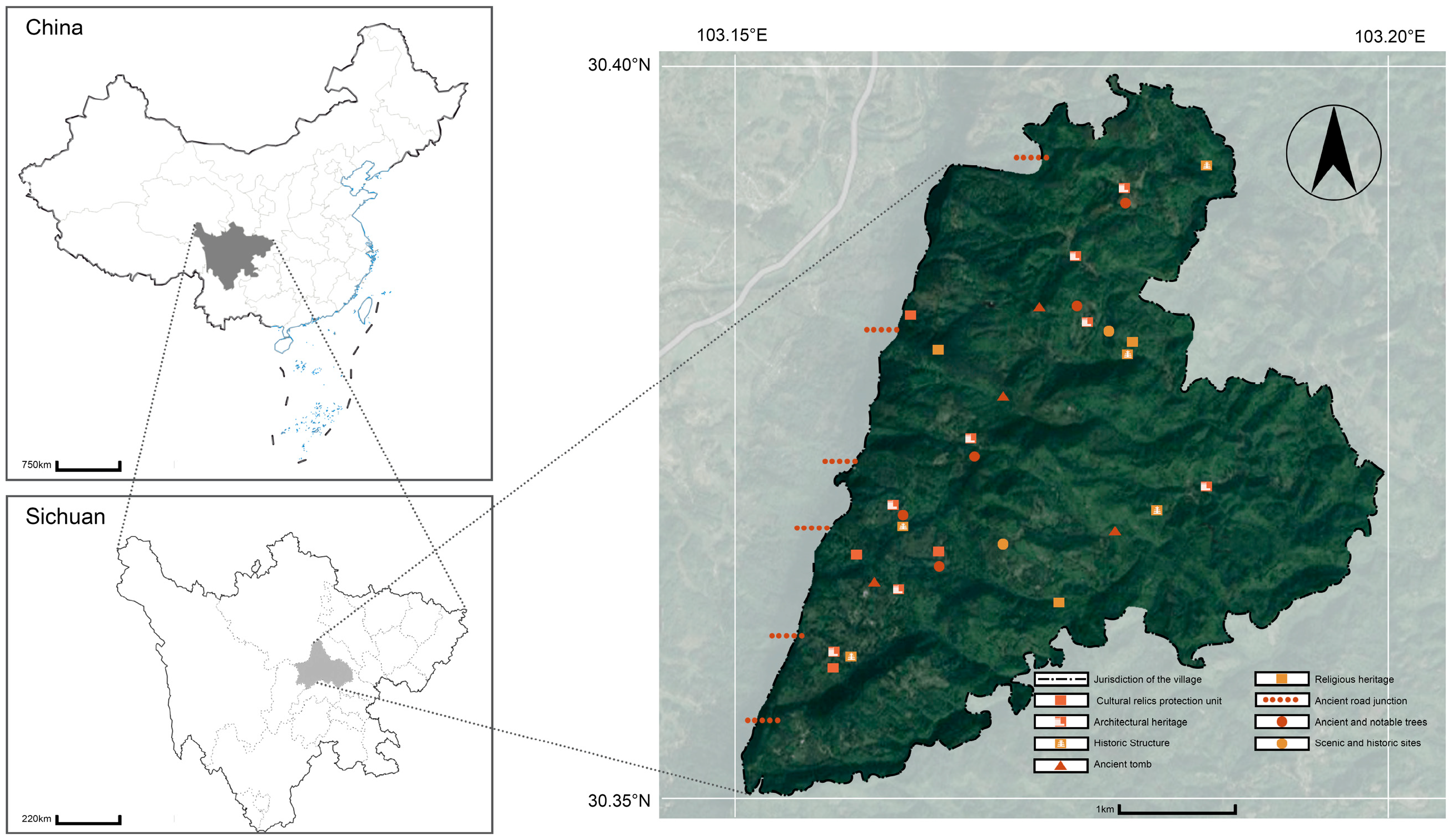

3.1. Study Location Context

3.2. Research Method

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Analysis

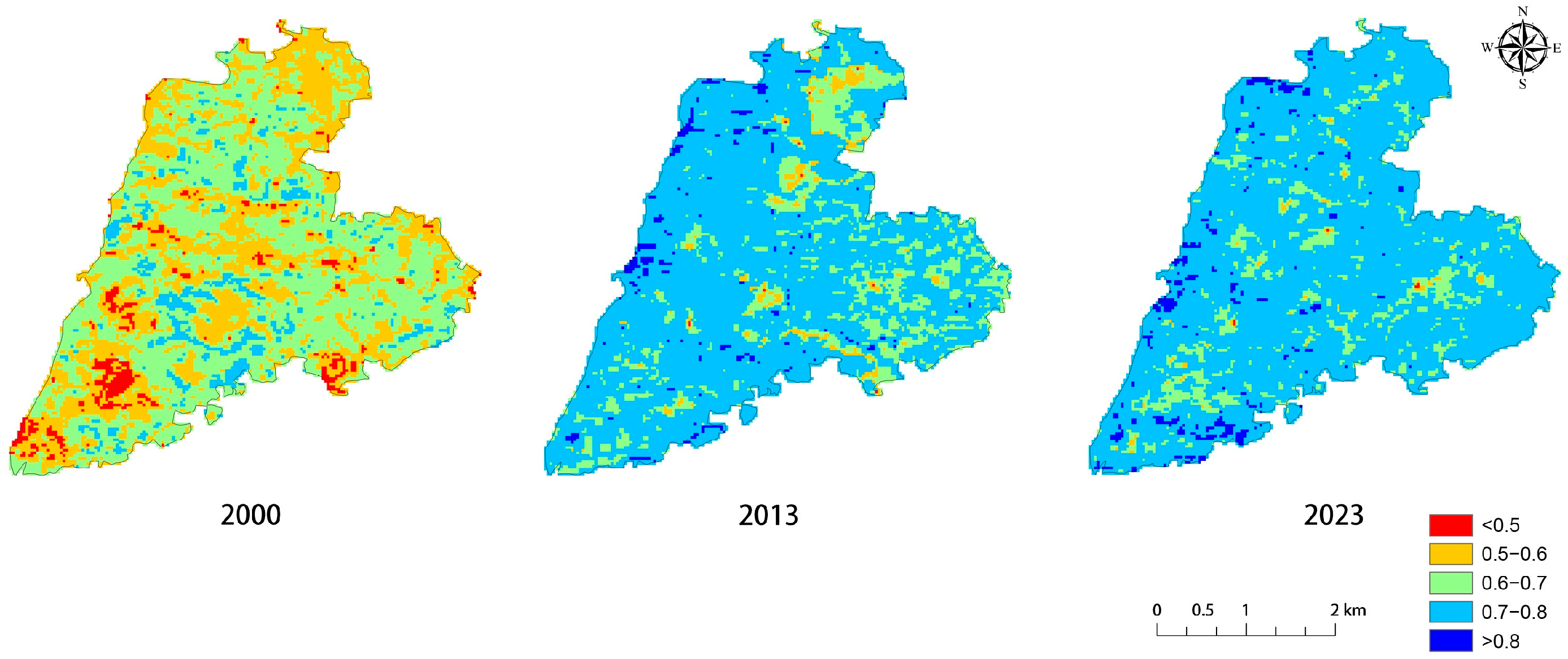

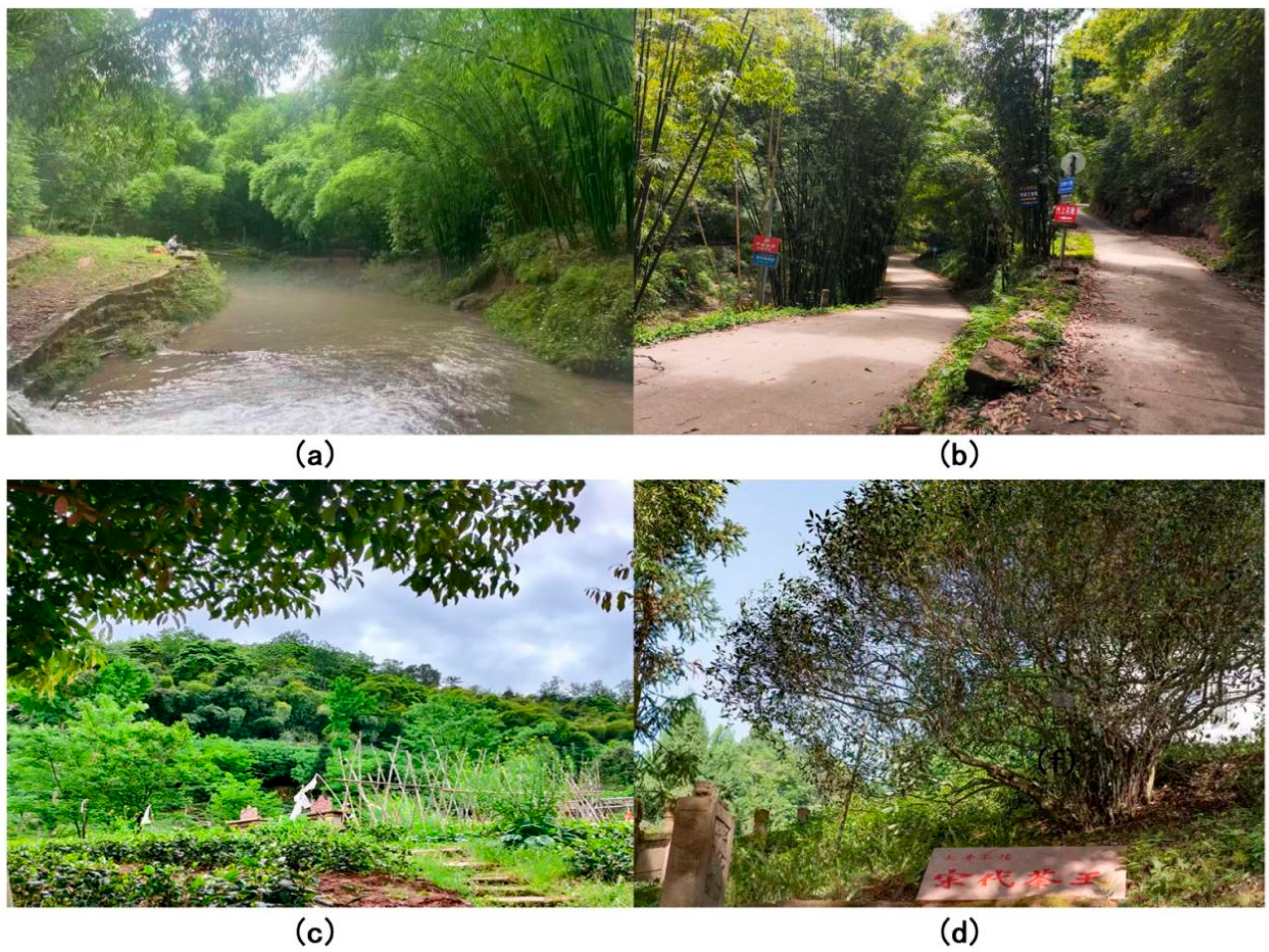

4.1.1. Green Space

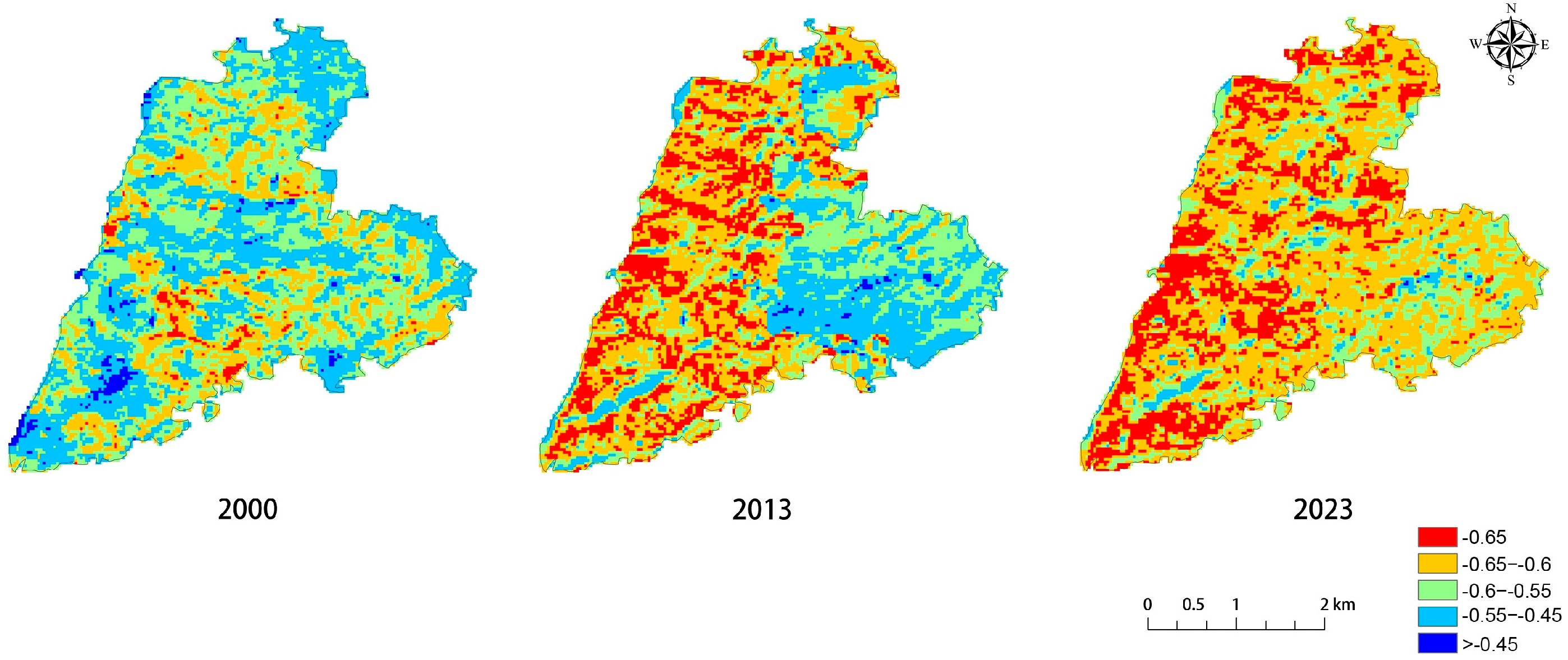

4.1.2. Water Space

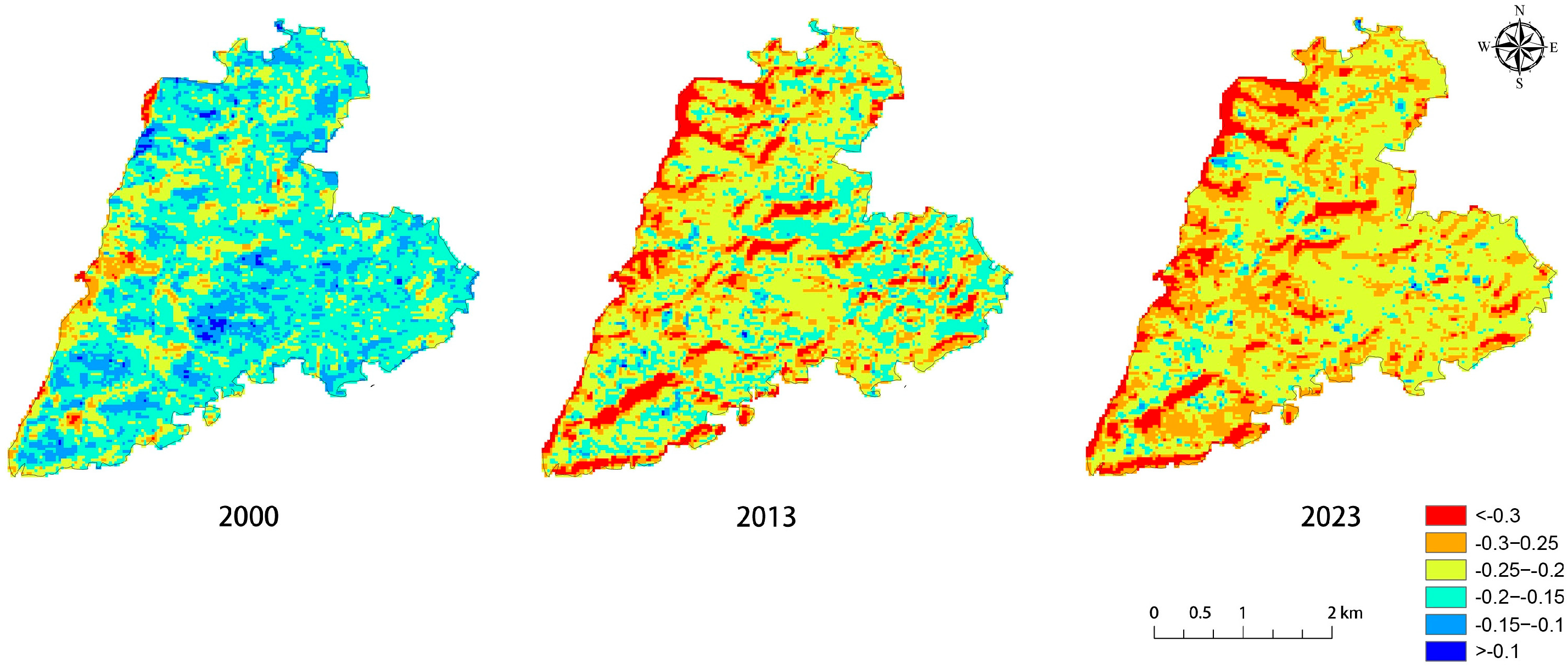

4.1.3. Building Space

4.2. Field Investigation

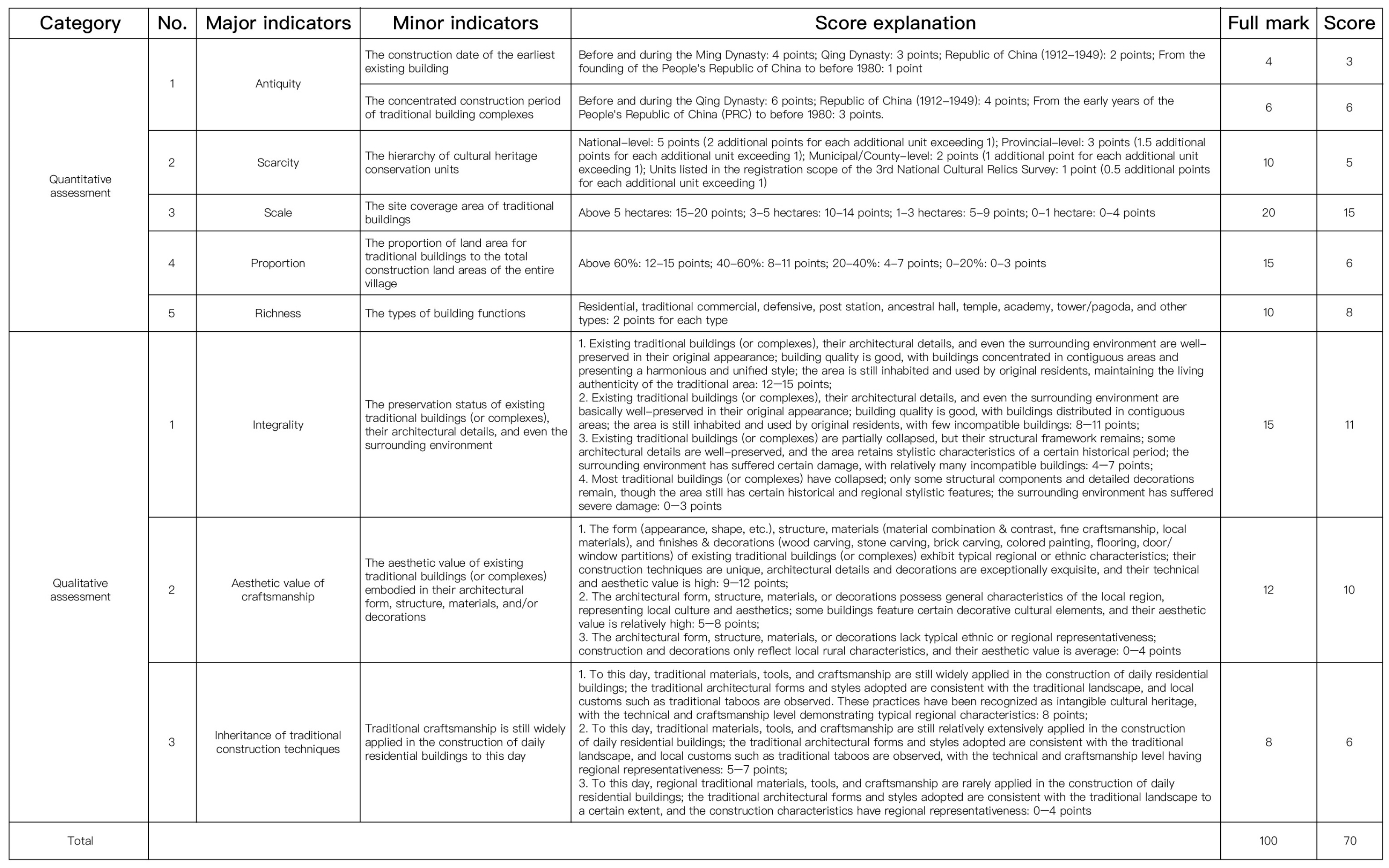

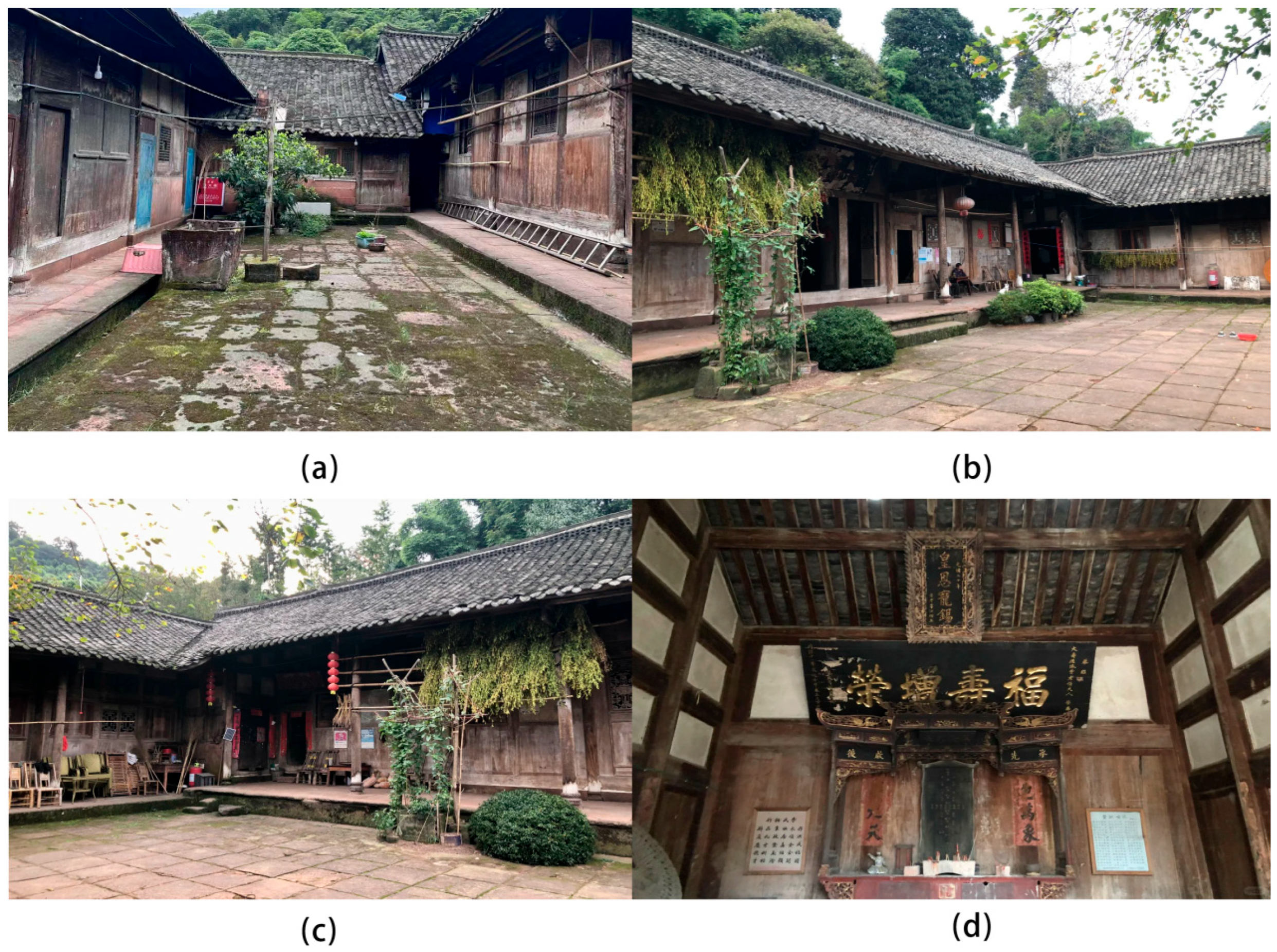

4.2.1. Traditional Buildings

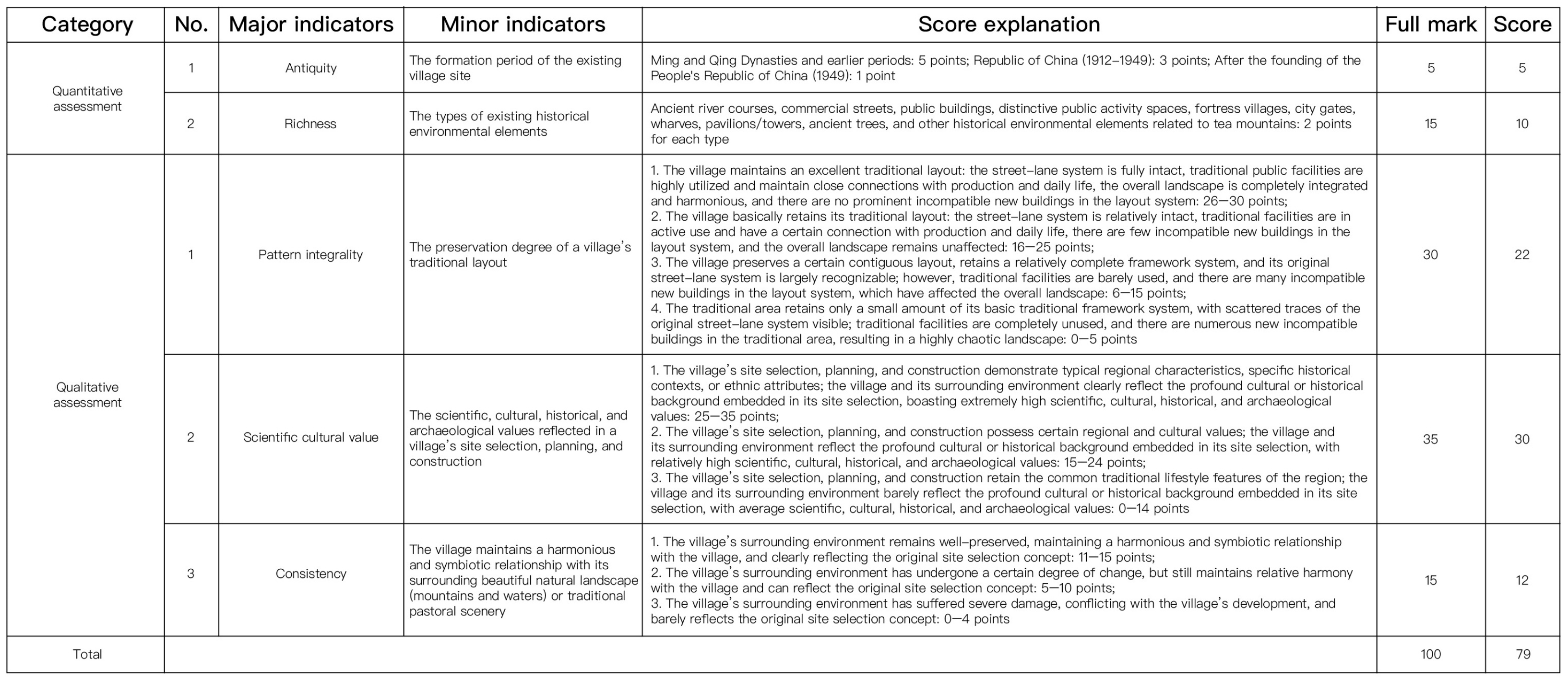

4.2.2. Village Site Selection and Layout

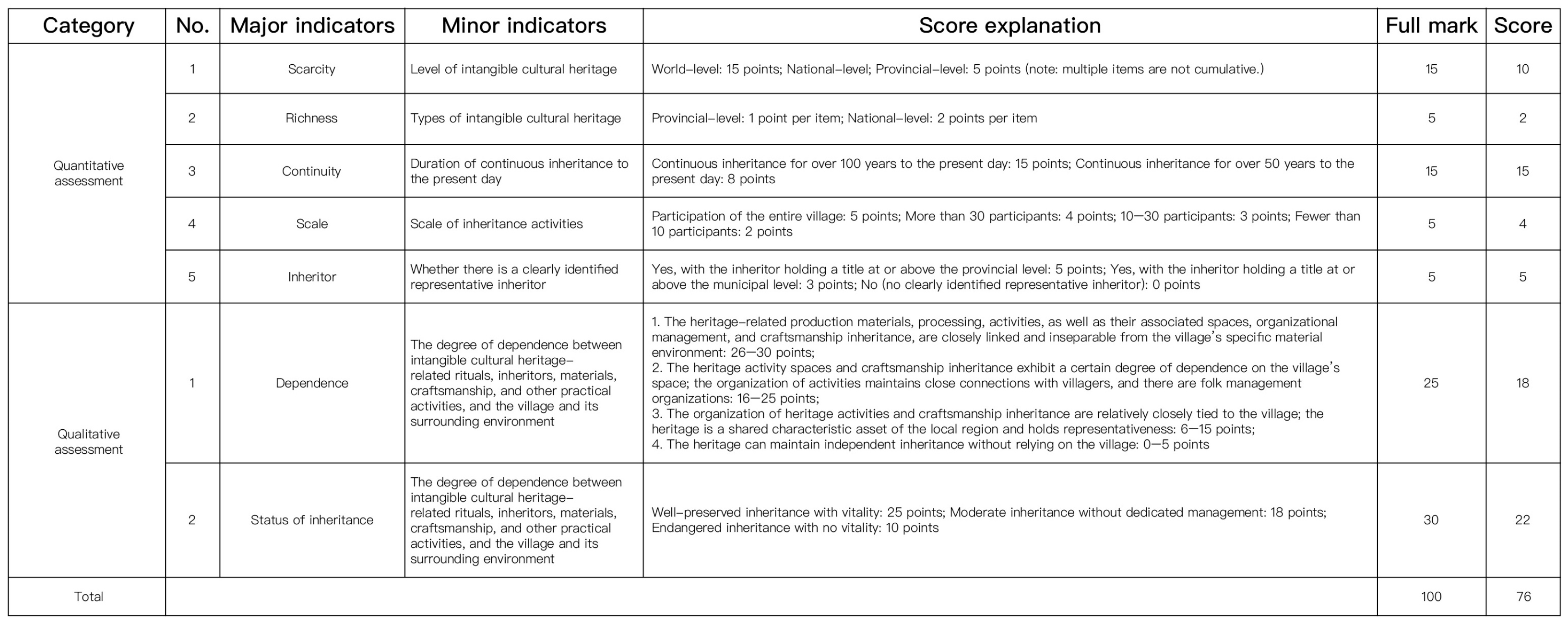

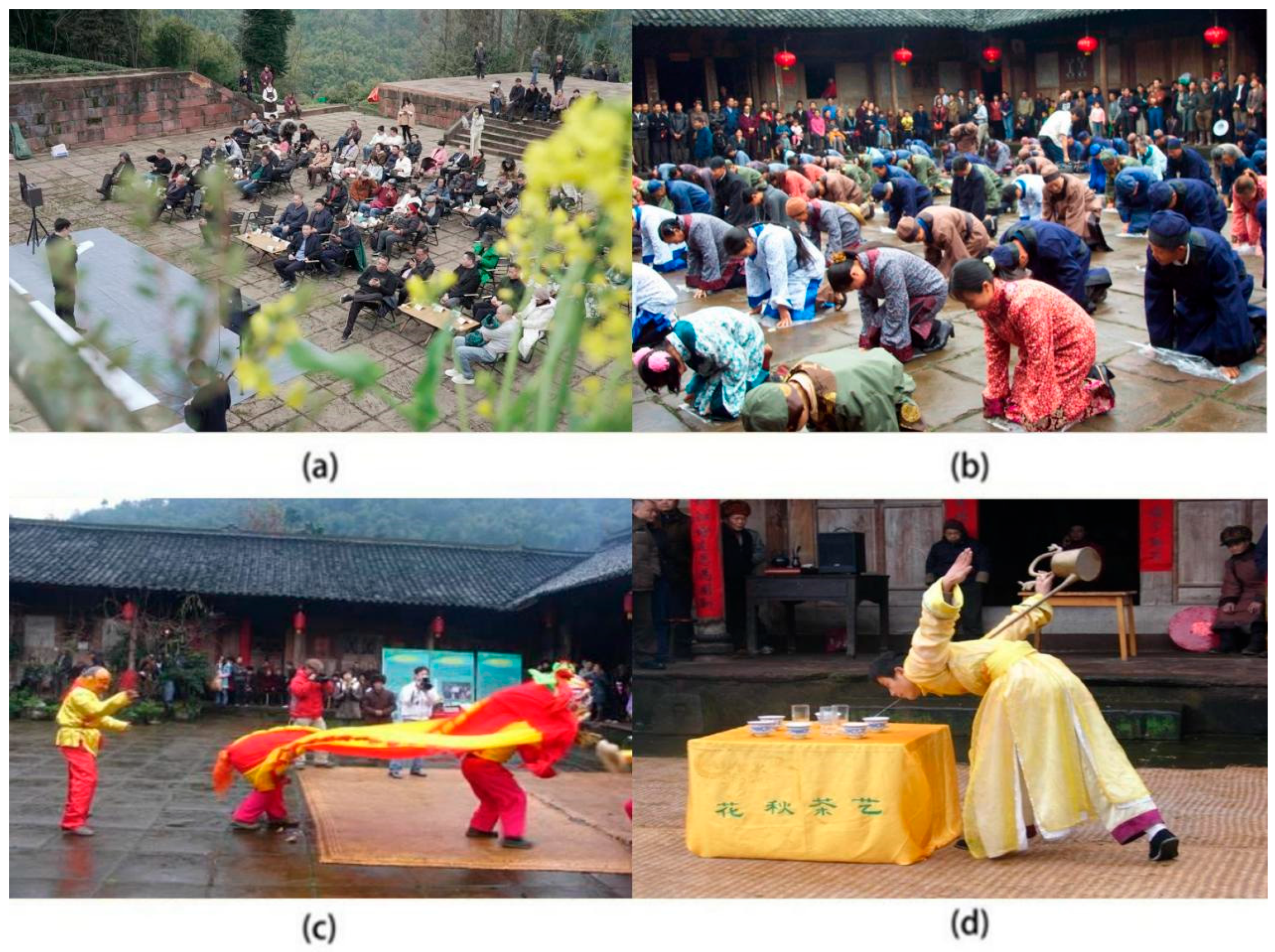

4.2.3. Intangible Cultural Heritage

4.3. Heritage Value Assessment and Analysis

4.3.1. Landscape Value

4.3.2. Functional Value

4.3.3. Spiritual Value

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary and Analysis of Key Findings

5.2. Comparison with Existing Studies: Validation of Rationality and Innovation

5.3. Theoretical Significance and Practical Application Value

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HUL | Historic urban landscape |

| NDVI | Normalized difference vegetation index |

| NDWI | Normalized difference water index |

| NDBI | Normalized difference built-up index |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| ETM+ | Enhanced Thematic Mapper |

| TIRS | Thermal Infrared Sensor |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| SWIR | Short-Wavelength Infrared |

Appendix A

References

- He, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiong, D. Evaluation on cultural value of traditional villages and differential revitalization: A case study of Jiaozuo City, Henan Province. Econ. Geogr. 2020, 40, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapidi, I. Heritage policy meets community praxis: Widening conservation approaches in the traditional villages of central Greece. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 81, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hu, J.; Chen, J. The study of spatial distribution patterns of traditional villages in China. Chin. Popul. Res. Environ. 2014, 24, 157–162. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, X. Heritage value assessment and landscape preservation of traditional Chinese villages based on the daily lives of local residents: A study of Tangfang Village in China and the UNESCO HUL Approach. Land 2024, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naheed, S.; Shooshtarian, S. The role of cultural heritage in promoting urban sustainability: A brief review. Land 2022, 11, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Beza, B.B.; Liu, C.; Wu, B.; Qiu, N. Differences in perspectives between experts and residents on living heritage: A Study of traditional Chinese villages in the Luzhong Region. Buildings 2024, 14, 4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T. Analysis of the protection and development issues of traditional villages in Mianyang, Sichuan. China Natl. Cond. Strength 2022, 9, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeayter, H.; Mansour, A.M.H. Heritage conservation ideologies analysis—Historic urban landscape approach for a Mediterranean historic city case study. HBRC J. 2018, 14, 345–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Q. Influencing Factors of traditional village protection and development from the perspective of resilience theory. Land 2022, 11, 2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsenkova, S. Sustainable housing and liveable cities: European habitat & The New Urban Agenda. Urban Res. Pract. 2016, 9, 322–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, A.; Herczeg, Á.; Ge, N.D.; Sárospataki, M. participatory landscape design and water management—A sustainable strategy for renovation of vernacular baths and landscape protection in Szeklerland, Romania. Land 2022, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, J.F. From the perspective of historical urban landscape layering, strategies for protecting ancient towns: A case study of Chikan Ancient Town in Jiangmen City. China Urban Planning Society People’s City, Planning Empowerment. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (18 Small Town Planning), Hangzhou, China, 5–8 July 2024; Guangzhou Urban Planning Survey and Design Research Institute: Guangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Weng, F.; Ding, F.; Wu, Y.; Yi, Z. Evolution of cultural landscape heritage layers and value assessment in urban countryside historic districts: The case of Jiufeng Sheshan, Shanghai, China. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y. A review of research on the perception of attachment to historical sites in traditional villages from the perspective of multiple subjects. Archit. Cult. 2024, 5, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century; Tongji University Press: Shanghai, China, 2017; pp. 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, D. The Values of Heritage: A New Paradigm for the 21st Century. In From Postwar to Postmodern—20th Century Built Cultural Heritage; The 6th Baltic Sea Region Cultural Heritage Forum; Riksantikvarieämbetet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017; p. 99. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L. Optimization of heritage management mechanisms through the prism of historic urban landscape: A case study of the Xidi and Hongcun World Heritage Sites. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIAM. The Athens Charter; CIAM: Patris, Athens, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The Venice Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites; ICOMOS: Venice, Italy, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhu, Y. Research on the paradigm of traditional villages protection based on dynamic integrity. Urban Dev. Stud. 2024, 31, 8–13+33. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, X.; Yu, Y.; Liu, R. The spatial relationship characteristics and differentiation causes between traditional villages and intangible cultural heritage in China. Buildings 2025, 15, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Cao, W.; Cao, C. The concept and cultural connotation of traditional villages. Urban Dev. Stud. 2014, 21, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Zhou, L.; Liang, X.; Wang, W. Identifying the spatiotemporal patterns of traditional villages in China: A multiscale perspective. Land 2020, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Chen, D. Extraction and analysis of the spatial morphology of a heritage village based on digital technology and weakly supervised point cloud segmentation methods: An innovative application in the case of Xisongbi Village in Jiexiu City, Shanxi Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Deng, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhang, C. A new approach to protecting historical and cultural towns and villages. Contemp. Soc. Sci. 2018, 3, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Social Sciences Network. Ethical Reflections on the Digital Preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://www.cssn.cn/zkzg/zkzg_gxzkdzyx/zkzg_gxdzyx_yc/202505/t20250519_5874570.shtml (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hu, Y.; Zheng, F. Digital memory construction in Lijiang. Digit. Transform. Soc. 2024, 3, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Han, F. A review of the theoretical and practical research on historic urban landscape. Landsc. Archit. 2017, 24, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, T.; Han, Y.; Ikebe, K. urban heritage conservation and modern urban development from the perspective of the historic urban landscape approach: A case study of Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Van Oers, R. The historic urban landscape: Managing heritage in an urban century. Urban Morphol. 2013, 17, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S. Research on the Protection Planning of Traditional Villages with Artistic Characteristics in Regong from the Perspective of Historic Townscape (HUL). Master’s Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Analysis of Landscape Imagery and Protection Strategies of Qingcheng Ancient Town, Lanzhou. Master’s Thesis, Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University, Fuzhou, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Place Attachment and Landscape Improvement of Historical Places in Hui’gang Traditional Village of Hangzhou: Based on Multiple Stakeholders’ Perspective. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sari, K.E.; Antariksa, M.; Keppi, S. The Development of HUL (Historic Urban Landscape) concept for community based conservation in Surabaya City. Evergreen 2024, 11, 1125–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macamo, S.; Raimundo, M.; Moffett, A.; Lane, P. Developing heritage preservation on Ilha de Moçambique using a historic urban landscape approach. Heritage 2024, 7, 2011–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juma, M.; Turner, M. Reshaping Urban Conservation: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 529–543. [Google Scholar]

- Lux, M.S.; Tzortzi, J.N. From thermal city to well-being landscape: A Proposal for the UNESCO Heritage Site of Pineta Park in Montecatini Terme. Heritage 2025, 8, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha Ferreira, T.; Rey-Pérez, J.; Pereira Roders, A.; Tarrafa Silva, A.; Coimbra, I.; Breda Vazquez, I. The historic urban landscape approach and the governance of world heritage in urban contexts: Reflections from Three European Cities. Land 2023, 12, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China News Network. Huaqiu Village in Qionglai City is Listed in the National List of Traditional Chinese Villages. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/cul/2015/01-27/7009561.shtml (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Z. Study on the status quo and development of traditional village protection: A case study of Huaqiu Village, Pingle Town, Qionglai City. Value Eng. 2019, 38, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niković, A.; Manić, B.; Čolić Marković, N.; Krunić, N. A contribution to the integration of international, national and local cultural heritage protection in planning methodology: A case study of the Djerdap Area. Land 2024, 13, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Hussain, B.; Hissan, R.U.; Al Aiban, K.M.; Radulescu, M.; Magazzino, C. Examining the landscape transformation and temperature dynamics in Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyango, D.O.; Opiyo, S.B. Detection of historical landscape changes in Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya, using remote sensing multi-spectral indices. Watershed Ecol. Environ. 2022, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgi, M.; Russell, E.W. Integrative methods to study landscape changes. Land Use Policy 2001, 18, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengberg, A.; Fredholm, S.; Eliasson, I.; Knez, I.; Saltzman, K.; Wetterberg, O. Cultural ecosystem services provided by landscapes: Assessment of heritage values and identity. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 2, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T. Analysis of the Effects and Problems of Converting Farmland to Forest: Taking Qionglai for an Example. Cent. South For. Inventory Plan. 2006, 3, 29–31+34. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, M.Y.; Ng, S.T. The art and science of Feng Shui—A study on architects’ perception. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Pei, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Y. Expansion of irrigation led to inland lake shrinking in semi-arid agro-pastoral region, China: A case study of Chahannur Lake. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2022, 41, 101086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, A.; Schmitt, T. Urban and tourist land use patterns and water consumption: Evidence from Mallorca, Balearic Islands. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T. Exploration on the sustainable development model of historical village tourism development based on HUL: A Case study of tourism development in Huaqiu Village. In Proceedings of the Research on Urban Renewal and Sustainable Development, Rizhao, China, 29 June 2017; Planners: Nanning, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Traditional Chinese Village Digital Museum. Evaluation and Identification Index System for Traditional Village (Trial). Available online: https://www.dmctv.cn/zcfgShow.aspx?id=14 (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Ruan, Y.S. The protection and inheritance of traditional Chinese architectural culture. Centen. Archit. 2003, 1, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Wang, P. Research on the protection and development of traditional village culture under the rural revitalization strategy: A case study of Huaqiu Village in Chengdu. Rural Sci. Technol. 2024, 15, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Yang, R.; Zhu, C.; Xue, K. Tourists’ narrative engagement and the multidimensional construction of historic urban landscapes: Exploring the role of narration in place attachment. Landsc. Res. 2024, 49, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, N. Conservation design for traditional agricultural villages: A case study of Shirakawa-go and Gokayama in Japan. Built Herit. 2019, 3, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbiankova, A.; Scherbina, E.; Budzevich, M. Exploring the significance of heritage preservation in enhancing the settlement system resilience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; ICOMOS: Nara, Japan, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- China Economic Network. Strategies for Traditional Villages to Gain a Competitive Edge in Rural Tourism Development. Available online: http://travel.ce.cn/gdtj/201503/30/t20150330_2421864.shtml (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Liu, S.; Ge, J.; Bai, M.; Yao, M.; He, L.; Chen, M. Toward classification-based sustainable revitalization: Assessing the vitality of traditional villages. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, H.; Jiang, M.; Zhao, J. An HUL assessment for small cultural heritage sites in urban areas: Framework, methodology, and empirical research. Land 2025, 14, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DPhinyoyang, A.; Ongsomwang, S. Optimizing land use and land cover allocation for flood mitigation using land use change and hydrological models with goal programming, Chaiyaphum, Thailand. Land 2021, 10, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, M.; Asadi, A.; Pukanska, K.; Zelenakova, M. An Assessment on the safety of drinking water resources in Yasouj, Iran. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K. The historic urban landscape. managing heritage in an urban century. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 326–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Walker, J.H. Forests and Farmers: GIS analysis of forest islands and large raised fields in the Bolivian Amazon. Land 2022, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L. A GIS, landscape pattern and network analysis based planning of ecological networks for Xiamen Island. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2005, 29, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Liang, X.; Wen, X.; Yun, X.; Ren, L.; Yun, Y. GIS-Based analysis of the spatial distribution and influencing factors of traditional villages in Hebei Province, China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Tong, Y. Spatial differentiation of traditional villages using ArcGIS and GeoDa: A case study of Southwest China. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 68, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Pingyao: The historic urban landscape and planning for heritage-led urban changes. Cities 2020, 97, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmizi, O.; Aykut, K. A participatory planning model in the context of historic urban landscape: The case of Kyrenia’s historic port area. Land Use Policy 2020, 102, 105130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, J. A study on modern architectural heritage listing system based on whole-process evaluation. New Archit. 2017, 6, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Acquisition Date | Satellite/Equipment | Sensor Model | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-04 | Landsat 7 | Enhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM+) | 30 m |

| 2013-04 | Landsat 8 | Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) | Same as above |

| 2023-04 | Landsat 8 | Same as above | Same as above |

| No. | Place | Original Function | Current Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Xu Family Compound | residence | culture, residence |

| 2 | Li Family Compound | residence | commerce, culture, residence |

| 3 | Tea Garden | planting | culture, commerce, planting |

| 4 | Cliff Carving of Sanyi Temple | sacrifice | culture, sacrifice |

| 5 | Papermaking Workshop Ruins | production | culture, education |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Liu, R.; Yin, T.; He, X. Assessment and Protection of Heritage Value of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Huaqiu Village. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17208981

Cai X, Chen X, Zhou W, Liu R, Yin T, He X. Assessment and Protection of Heritage Value of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Huaqiu Village. Sustainability. 2025; 17(20):8981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17208981

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Xinyang, Xinyue Chen, Weilan Zhou, Ruiyi Liu, Tong Yin, and Xiangting He. 2025. "Assessment and Protection of Heritage Value of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Huaqiu Village" Sustainability 17, no. 20: 8981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17208981

APA StyleCai, X., Chen, X., Zhou, W., Liu, R., Yin, T., & He, X. (2025). Assessment and Protection of Heritage Value of Traditional Villages from the Perspective of Historic Urban Landscape: A Case Study of Huaqiu Village. Sustainability, 17(20), 8981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17208981