Abstract

China’s rapidly aging population necessitates a sustainable social care system. Although the majority of Chinese disabled older adults live in their communities, the utilization rate of home- and community-based care (HCBC) services has been low. Moreover, family members still take the main responsibility for the care of disabled older persons and generally suffer from the stress of caregiving. To increase the use of HCBC services by disabled elderly families, this study examined which individual characteristics of both elderly individuals and their primary family caregivers were related to HCBC service use among disabled urban elderly individuals in a regional sample from the 2018 to 2019 Beijing Precise Assistance Need Survey (n = 34,153). Logistic regression was used as the baseline model, and a simultaneous equation model was established to address the jointly dependent variables. The results show that the degree of disability of disabled older adults has no significant effect on their service use, whereas their worse health status played a significant role in predicting respite care service use. Working status, a longer period of caregiving, and poor health of caregivers all significantly predict a greater likelihood of service use by elderly individuals. Caregivers with burdened feelings predicted a decrease in the likelihood of elderly individuals using services. Our findings show that primary family caregivers have an important influence on disabled elderly people’s use of HCBC services, but service use is more likely to compensate for the lack of care and expertise provided by family caregivers than to reduce caregivers’ caregiving burden.

1. Introduction

In response to the rapidly aging population, the Chinese Central Government outlined a plan for a three-tiered elderly care service system in the 12th Five-Year Plan (2011–2015) for National Economic and Social Development, which emphasized home-based care as its foundation, supported by community-based services and institutional care. The 13th Five-Year Plan for Developing Elderly Service Undertakings and Establishing an Elderly Care System continued with this system and merged “home-based care” and “community-based care” into “home- and community-based care (HCBC)”. Pilots have accelerated the development of HCBC services across major cities in China since 2016. However, the usage rate of HCBC services is still very low, even in urban areas [1].

In the face of this problem, many domestic researchers have explored the regularity of elderly people’s utilization of HCBC services from the demand-side perspective. However, most studies have focused on the general elderly population, and few studies have focused specifically on disabled elderly people’s use of HCBC services. One estimate is that the number of older Chinese people (aged ≥ 60 years) with dependency in 2020 was 45.30 million, and this number is projected to increase to 59.32 million by 2030 [2]. At present, the vast majority of disabled older Chinese adults live in their communities and remain primarily cared for by family members [3,4]. Previous foreign studies have shown that family caregivers are important influences on the use of formal care services by frail and disabled older adults [5,6]. Given China’s unique social and cultural background, the regularity of Chinese disabled older adults’ use of HCBC services may be unique. On the one hand, China’s long-term care insurance system is still piloted only in some cities, which means that for most elderly people, HCBC services have to be paid for by out-of-pocket payments. On the other hand, China has a family caregiving culture that has lasted for thousands of years. Family members, especially adult children, are responsible for the care of their disabled parents, whereas primary family caregivers generally feel burdened with long-term care and have a greater demand for formal support services [7]. In this context, exploring the regularity of disabled elderly people’s use of HCBC services can provide relevant suggestions for increasing the utilization of services by disabled elderly families to better meet the care needs of disabled elderly people, support family caregivers, and make traditional family care more sustainable. This is not only in line with the Sustainable Development Goals but can also provide insights for the development of HCBC services in areas with similar backgrounds.

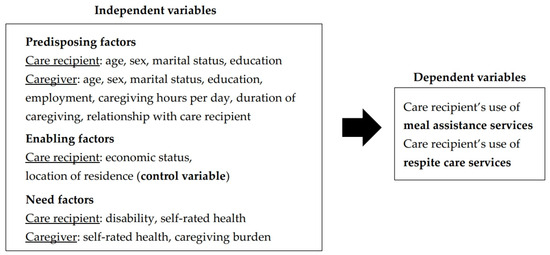

Anderson’s model has been the dominant research framework in the field of service utilization. Although this model was originally applied to the use of health services, it has been extended to care service utilization by aged individuals by many researchers [8,9]. A person’s use of health services is determined by the predisposing, enabling, and need attributes of the individual [10]. People with certain predisposing characteristics, such as age, sex, marital status, education, occupation, and attitudes towards the service, are more likely to use the service. Enabling factors are the conditions that make the service available to the individual, such as income and the amount of service resources in the community. Need factors represent the cause of service use. For elderly individuals, the main need factors for their use of care services are health conditions and disability [11].

Bass and Noelker argued that a deficiency in the Andersen model of service use is its neglect of family-related factors [12]. Family members are central to the care of disabled older adults [12], especially primary family caregivers, who have been proven to play an important role in elderly people’s use of care services [5,13]. Thus, they developed an expanded Andersen framework that includes predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of both the primary family caregiver and the elder care recipient. In the expanded model, the sociodemographic characteristics of the primary family caregiver, as well as their kinship with the elder care recipient and their perceptions of care responsibilities, were included in the predisposing factors, and the caregiver’s need attributes, such as health status and caregiving burden, were included in the need factors [12,14].

However, the empirical results from these two models’ widespread application have been inconsistent or conflicting. In summary, there are three main reasons for this. First, in most studies, various HCBC services are measured as one type of service, which may simultaneously include paid and free services, medical care, and social care services. However, some studies have reported that the factors influencing different types of service use among elderly individuals are not the same [15,16,17].

Second, as mentioned by Lee and Penning (2019), differences in results emerge with respect to the samples studied [9]. Some studies focus on determinants of service use among older adults in general [16,18], whereas others restrict their focus to those with functional limitations [12,13], and some focus only on older adults living in urban areas [17,19]. Elderly individuals with different health conditions prefer to use different kinds of elderly care services [8], and disabled elderly individuals can usually receive help from their families, which has been proven to significantly affect elderly individuals’ use of formal care services, especially in China [9,20]. In addition, domestic and foreign studies have revealed that there are differences between urban and rural areas in terms of the factors affecting elderly people’s or caregivers’ use of formal support services [21,22].

Third, the inconsistent results may be related to the different analysis methods used. Taking the caregiving burden as an example, in the expanded Anderson model, the caregiver’s burden is considered an important need factor affecting formal service use. However, at the same time, the use of formal care services can have a significant effect on the relief of the caregiver burden [23,24], which means that two variables may be jointly dependent. Miller and McFall (1991) used longitudinal data analysis and reported that a caregiver’s personal burden had a lagged effect on increased use of formal services [6]. However, in other cross-sectional studies, no specific method to solve the problem of mutual causation of the two variables was used, and the conclusions of caregiver burden on service utilization are inconsistent [21,25].

In this study, we focus on the individual-level factors of both disabled elderly individuals and their primary family caregivers influencing the use of meal assistance services and respite care services by disabled urban elderly individuals in the social and cultural context of China. Moreover, a simultaneous equation model was used to examine the impact of caregiver burden on the use of services by disabled elderly individuals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

The cross-sectional data for this study were selected from the 2018 to 2019 Beijing Precise Assistance Need Survey, which was described by Gao and Tang (2024) [23]. All seniors aged 80 years and older who were living in Beijing were investigated in this survey, and data were collected via household interviews.

Given our research target, we first selected respondents aged 80 years and older who were disabled and were primarily cared for by family members or relatives, and the selected sample size was 73,139. Owing to the low supply level of HCBC services in rural areas, we then restricted the sample to those elderly with Beijing household registration and living in the central urban area, and approximately 43.06% (n = 31,492) of the older adults were excluded from the initial sample (n = 73,139). The Beijing municipal government provides financial subsidies to elderly people from special families, such as low-income families, to support them in purchasing formal elderly care services. We removed respondents from these special families (n = 750) from the subsample (n = 41,647). Removing the missing values for key variables resulted in 16.49% (n = 6744) being excluded from the remaining sample (n = 40,897). In the end, 34,153 pairs of eligible disabled older adults and their primary family caregivers were analyzed in this study.

2.2. Analytic Framework

We draw on the expanded Anderson model of elder use of care services and combine the variables of the used data to form the analytic framework of this study, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The analytic framework of disabled older care recipients’ HCBC service use.

In our analytic framework, the use of HCBC services by disabled older adults is determined by predisposing factors, enabling factors, and need factors of the care recipients and their primary family caregivers. As our study focuses on the individual-level factors affecting the elderly’s use of services on the demand side, the variable “elderly’s location of residence”, which can reflect the quantity and quality of services in the elderly’s residential areas, is an influencing factor on the supply side; thus, it will be included in the study as a control variable.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

There are two dependent variables in this study, both of which are binary variables. Our research focuses on disabled older adults’ use of two types of HCBC services: meal assistance services and respite care services. If the older adults used meal assistance services, such as having meals or buying to take home in community elderly canteens or having meals-on-wheels, they were coded as 1 = use and 0 if they had never used this type of service. Respite care services include going to a day care center, receiving in-home respite care, or institutional respite care. If the respondent used this type of service, it was scored as 1; if not, it was scored as 0.

2.3.2. Independent Variables

In the questionnaire, the older adults’ and caregivers’ marital statuses were structured as follows: 1 = never married, 2 = married, 3 = divorced, 4 = widowed, and 5 = living with a partner. We divided marital status into two categories: 1 = married by combining the second and fifth categories and 0 = unmarried by combining the remaining categories. If caregivers were working for pay at the time of the interview, they were coded as 1 = working and 0 if they had never worked or had retired.

Since there are no personal or family income variables for the older adults in the data, we select substitute variables to reflect their economic status. In China, pensions are the main source of income for elderly individuals, especially in urban areas [26]. In addition, the size of pensions varies widely across different pensions in China, as reflected by the fact that public pensions are higher than those of employees in private companies and much higher than those of urban and rural residents [27]. Therefore, we chose the pension insurance type of the elderly to reflect their income level. Only 2.21% of the elderly respondents in this study did not have any pension insurance. We divided the pension insurance type into three categories: 1 = none or basic pension insurance for urban and rural residents (low income), 2 = basic pension insurance for urban enterprise employees (middle income), and 3 = basic pension insurance for civil servants and public sector employees (high income).

The older adults’ disability was assessed for problems in activities of daily living (ADL). ADLs were measured using the Chinese version of the Barthel Index [28], a widely used ten-item ADL scale scored from 0 to 100. We divided disability into three categories: 1 = mild disability if the score was 61–99, 2 = moderate disability if the score was 41–60, and 3 = severe disability if the score was 0–40. If caregivers felt pressured to care for the disabled relative, they were coded as 1 = bearing the caregiving burden and 0 if they did not. The specific classification and description of all the independent variables are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive of disabled older adults’ characteristics and their service utilization; n = 34,153.

Table 2.

Descriptive of primary family caregivers’ characteristics and elderly service utilization; n = 34,153.

2.4. Analysis

The percentages of the two types of HCBC service utilization—based on the characteristics of both disabled older adults and caregivers—were analyzed via Crosstabs and the chi-square test (see Table 1 and Table 2). We first used logistic regression to explore the determinant factors of the use of two types of services. We then established two simultaneous equation models to examine the impact of the caregiving burden on the use of two types of services, and iterative three-stage least squares was used to estimate the model. The simultaneous equation model (SE model) is a model that can analyze the relationship between two variables with a two-way causal relationship. In the SE model, the error terms are assumed to be serially independent and identically distributed, the model must be complete, and each equation in the model must be identified. For an equation to be identified in a system of equations, the number of variables excluded from the equation must be equal to or greater than the total number of equations of the model minus one.

In our study, a simultaneous equation model contains two equations; the two equations are as follows:

where “Utilization” is disabled older adults’ use of HCBC services: meal assistance services and respite care services, and “Burden” is the caregiver’s caregiving burden. Xu are other predisposing, enabling, and need factors, but do not include “caregiver’s relationship with care recipient”, which was not associated with elderly service use in the logistic regression models. Xc are variables from predisposing, enabling, and need factors that were confirmed by logistic regression analysis to have a significant effect on the caregiving burden of caregivers, including elderly individuals’ age, education, economic status, location of residence, disability, self-rated health, caregiver’s age, gender, marital status, relationship with care recipient, self-rated health, caregiving hours per day, and caregiving years. Each equation satisfies the criterion that the number of excluded variables is equal to or greater than the number of equations minus one.

Utilization = α0 + α1Burden + α2Xu + ε,

Burden = β0 + β1Utilization + β2Xc + η,

A significance level of 0.05 was used in this study, and STATA16 was used for all the statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive and Bivariate Analyses

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the disabled older care recipients. Most of them (79.47%) were aged 80–89 years; nearly 60% of them were women, and 54.57% of them were unmarried. Fifty-three percent of them were illiterate or had just completed primary school, and a small percentage (8.57%) of them had high incomes. More than 15% of the elderly individuals in this study reported severe dependence in the activities of daily life, and most of them (69.74%) were mildly disabled. Nearly 11% of them were self-rated as healthy, and more than 35% were in self-rated poor health status.

As shown in Table 1, 7.02% of the elderly used meal assistance services, and fewer than 4% used respite care services. Elderly people’s marital status (married), education (university or higher), disability (mild disability), and self-rated health (fair) were significantly related to a higher percentage of their meal assistance service utilization. Elderly individuals’ age (≥90), education level (illiterate/primary school), income level (high), disability status (mild disability), and self-rated health (fair) were significantly related to a higher percentage of their respite care utilization.

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the primary family caregivers. The caregivers in our study included spouses (17.22%), children (78.49%), and other relatives (4.29%). It is nearly 50/50 for males and females. More than 40% of them were aged 50–59 years, and the majority of them (93.15%) were married. Only 7.54% of the caregivers were illiterate or had just completed primary school, and 31.04% reported that they were working for pay. Nearly 45% of the caregivers spent more than 8 h in caregiving per day, and nearly 45% of them had been caring for elderly individuals for more than 10 years. Fewer than 5% of the caregivers were self-rated as having poor health status, and 58.16% of the caregivers experienced the caregiving burden.

As shown in Table 2, caregivers’ age (≥70), education (illiterate/primary school), employment (working), duration of caregiving (over 15 years), relationship with care recipient (spouses), self-rated health (fair), hours of caregiving/day (5~8 h), and caregiving burden (no) were significantly related to a higher percentage of elderly meal assistance service utilization. Caregivers’ age (≥70), sex (male), education (illiterate/primary school), employment (working), self-rated health (poor), hours of caregiving per day (5~8 h), and caregiving burden (no) were significantly related to a higher percentage of elderly respite care service utilization.

3.2. Predisposing, Enabling, and Need Factors for the Two Types of Service Use

Table 3 summarizes the results of logistic regression and the simultaneous equation model (SE model) on disabled elderly people’s use of meal assistance services. The logistic regression results are referential, and we look mainly at the results of the SE model.

Table 3.

Logistic regression and simultaneous equation results of factors influencing the elderly’s use of meal assistance services; n = 34,153.

As presented in Table 3’s SE model, among the predisposing factors, disabled elderly individuals’ sex and education level were significantly related to their meal assistance service use. Specifically, male disabled elderly individuals were less likely to use meal assistance services (β = −0.010, p < 0.01), whereas disabled elderly individuals who had higher education levels were more likely to use this type of service. The caregiver’s sex, education, employment, number of hours of caregiving per day, and number of years of caregiving were significantly associated with the elderly’s use of meal assistance services. Elderly individuals whose caregivers were male were less likely to use meal assistance services (β = −0.012, p < 0.01). The disabled care recipients whose caregivers were illiterate or had just completed primary school had the highest possibility of using meal assistance services. Compared with care recipients whose caregivers were not working, individuals whose caregivers were working were more likely to use meal assistance services (β = 0.036, p < 0.001). The disabled care recipients whose caregivers cared for 5~8 h per day (β = 0.097, p < 0.001) and who cared for more than 8 h per day (β = 0.065, p < 0.05) were more likely to use meal assistance services than were those whose caregivers cared for 0~4 h per day. Disabled care recipients whose caregivers reported longer periods of caregiving were more likely to use meal assistance services.

Of the enabling factors, disabled elderly people’s income level was not significantly related to their use of meal assistance services. Among the need factors, neither the degree of disability nor the self-rated health of the disabled care recipients had a significant influence on their use of meal assistance services, but the caregiver’s health status was significantly related to their use of meal assistance services. Disabled care recipients whose caregivers reported worse health status were more likely to use meal assistance services. Compared with disabled elderly individuals whose caregivers did not have the caregiving burden, elderly individuals whose caregivers were burdened were less likely to use meal assistance services, but the coefficient was not statistically significant (β = −0.165, p > 0.05).

Table 4 summarizes the results of the logistic regression and simultaneous equation model on disabled elderly people’s use of respite care services.

Table 4.

Logistic regression and simultaneous equation results of factors influencing the elderly’s use of respite care services; n = 34,153.

A comparison of the data in Table 4 and Table 3 reveals that there are differences between the factors affecting the use of respite care services and the factors affecting the use of meal assistance services for disabled care recipients. As shown in Table 4, among the predisposing factors in the SE model, the effects of care recipient sex, caregiver sex, and education level were not significant, and care recipients who were illiterate or had just completed primary school had the highest possibility of using respite care services. Moreover, care recipients whose caregivers were older were more likely to use respite care services. Of the enabling factors, care recipients’ income level was significantly related to their use of respite care services. Elderly individuals with high incomes and middle incomes were more likely to use respite care services than were those with low incomes (β = 0.006, p > 0.05; β = 0.008, p < 0.05). Among the need factors, the worse health status of care recipients significantly increased their likelihood of using respite care services.

4. Discussion

In the context of the global advocacy of aging in place, the development of home- and community-based care (HCBC) services is an inevitable measure to cope with population aging, and the utilization of services is the key to the sustainable development of HCBC services. On the basis of the expanded Anderson model, this study examined which predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of both disabled older care recipients and their primary family caregivers were related to meal assistance service use and respite care service use among disabled Beijing urban elderly individuals.

Consistent with some prior studies [16,17], our study also revealed that factors associated with home- and community-based care service use differ by service type. Among the predisposing factors, our findings show that higher education of disabled elderly individuals was associated with an increased likelihood of their use of meal assistance services, whereas the relationship between elderly individuals’ higher education and respite care service use was negative. Care recipient reluctance to use services is a common reason for caregivers’ service nonuse [29]. Research has shown that elderly people’s higher education can promote their service use by enhancing their awareness and acceptance of social care services [30]. However, unlike the use of meal assistance services, the use of respite care services, such as day care centers, means that older people are separated from family caregivers and receive personal care from strangers, which can be very resistant to disabled elderly individuals. One study revealed that the consumption decision of commercial elderly care services is the result of the interaction of the power relationship between Chinese elderly people and their adult children [31]. Elderly individuals with higher education levels may be more empowered in their families to refuse to use respite care services, and they may also have more resources to access alternative support services. However, these speculations need to be confirmed by further empirical research in the future.

We also found that the likelihood of using meal assistance services was lower for elderly individuals with a male caregiver, whereas elderly individuals’ use of respite care services did not differ by caregiver gender. Previous studies have not been consistent on the relationship between caregiver gender and service use [32]. Our findings may be related to the gender division of Chinese family care. In China, when disabled elderly individuals are married, spouses are most likely to become the primary caregivers, but once elderly individuals become widowed, or their spouses become unable to provide care, adult sons, daughters-in-law, and daughters usually take over as the primary caregivers [33]. Although they are all primary caregivers, gender differences exist in the specific caring tasks. One study reported that male spouse caregivers usually provide personal care, and their children, especially daughters, do most of the housework [34]. When sons mainly take care of their parents, their wives also share housework. Therefore, male caregivers are more likely to have support from other family members in the caring task of cooking, so they are less likely to use formal meal assistance services. Compared with meal assistance services, the respite care services provide more comprehensive care. The informal respite care that family caregivers receive from their families is largely dependent on the availability of other family members who can temporarily play the role of primary caregivers, which is more influenced by family structure than by the gender division of family care.

The enabling effect of disabled older persons’ income on the use of respite care services has been demonstrated, but there is no significant relationship between disabled elderly people’s income and their meal assistance service use. Beijing became one of the long-term care insurance pilot cities in 2020, so for the respondents in this study, meal assistance services and respite care services both have to be paid for by out-of-pocket payments. The cost of meal assistance services is much lower than that of respite services. Since 2010, the elderly aged 80 and above in Beijing have received a monthly subsidy of 100 yuan to purchase home- and community-based care services [35], which makes meal assistance services easily accessible to the respondents of this study, even those with low and middle incomes. Among the need factors, the worse health status of care recipients played a significant role in predicting respite care service use but not meal assistance service use. Unhealthy disabled older adults are in greater need of professional care, which makes it difficult for family caregivers to provide it themselves. Day care center services and respite care services can complement family care with professional care. However, meal assistance services in the community usually provide meals for the general elderly population and do not have a unique appeal to unhealthy disabled elderly individuals.

The two types of services also have some common influencing factors. Among the predisposing factors, a longer period of caregiving of caregivers was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of elderly individuals using two types of services. Some researchers have suggested that cultural attitudes can influence the decision to seek formal care services [36]. Filial piety is a central value in traditional Chinese culture. Using formal care services in the face of norms of filial responsibility may evoke guilt [32] and risk possible criticism against them for not honoring their parents [37]. When caregivers have cared for elderly people for many years, they may feel that they have achieved so much and are psychologically more receptive to having formal services partially replace them, so those family caregivers who have been caring for more than 10 years may be more motivated to seek support from formal services.

The working status of family caregivers was a strong predictor of elderly service utilization. Working status can be interpreted as a caregiver’s need variable here because working caregivers need formal care services to help them ease work–family conflicts. Consistent with the findings of a previous study [13], we also found that caregivers’ poor health was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of elderly individuals’ service use. However, in contrast with previous studies [13,19,25], elderly people’s disability level was not significantly related to their service use in our study. Although disabled older persons with higher levels of disability require more care, in China, family caregivers often provide more care to meet the needs of older persons, and formal support services are used only when their caring capacity is insufficient to meet the needs of elderly individuals.

Contrary to our expectations, in our study, caregivers with burdened feelings predicted a decrease in the likelihood of using services by elderly individuals, although the coefficient was not statistically significant. This finding contrasts with many existing studies [6,12,21]. On the one hand, limited social interaction and physical exhaustion are the more common types of burdens on family caregivers [38]. Caregivers with caregiving burdens have less social contact and are thus less likely to be informed about community elderly care services, and it is possible that caregivers with caregiving burdens are too busy and tired to have the time and energy to seek formal services. On the other hand, caregivers with caregiving burdens are more likely to be those with more filial piety, a sense of responsibility and dedication, who are more likely to have less desire for other sources of support for elder care [39].

In summary, the expanded Anderson model can be used to explain the use of different types of home- and community-based care services by Chinese disabled elderly people who are mainly cared for by family members, but it needs to be combined with the Chinese social and cultural background, such as family care culture, filial piety culture, and the gender division of family care. Influenced by the culture of family care and filial piety, the primary family caregiver will provide care for disabled relatives as much as possible, which leads to a less prominent impact of the care needs of disabled care recipients on the use of formal services, whereas the support needs of family caregivers have a significant impact. However, the need for formal services by caregivers stems more from their own inability to provide more professional or adequate care for their disabled relatives than from a desire to alleviate their own care burden. In the long run, this will be detrimental to the sustainable development of family care. Efforts must be made to enable families of disabled older persons to use formal services earlier rather than when the health of the family caregiver deteriorates and their capacity to care is impaired. To improve the utilization rate of home- and community-based elderly care services, first, disabled elderly people and family caregivers need to know and accept home- and community-based elderly care services. With the continuous improvement in the education level of elderly people, the acceptance of formal care services for elderly people will increase in the future. How to raise the awareness of family caregivers, especially family caregivers with caregiving burdens, to seek formal care support, reduce their caregiving burden, and allow them to have more access to relevant information and services is critical and must be strengthened.

Our study provides empirical insights into the use of home- and community-based care services by disabled elderly families in areas with sociocultural backgrounds similar to those in China. Moreover, our findings suggest several practical and policy implications. For service suppliers, disabled elderly individuals with high education levels, female caregivers, employed caregivers, unhealthy caregivers, and caregivers who have been caring for a long time are the key targets for the promotion of meal assistance services. The promotion of respite services should focus on unhealthy and high-income disabled elderly individuals, employed caregivers, unhealthy caregivers, and caregivers who have been caring for a long time. Consider tailor-made respite services for disabled older adults with high incomes and high education levels. For community workers, it is essential to have information on family caregivers of disabled older persons, especially burdened family caregivers, provide them with information support, and help link them to resources. At the same time, community activities such as lectures and peer groups should be conducted to promote the awareness of support and care for family caregivers. In our study, the degree of disability had no significant effect on disabled older adults’ service utilization. This makes us have to consider the rationality of applying for services mainly on the basis of the degree of disability of the elderly in some pilot areas of respite care services in China. When assessing the care needs of disabled older persons, it is necessary to assess the status of the primary family caregiver, such as employment, health status, and caregiving burden.

Our study has limitations. First, previous studies have shown that service availability, awareness [40], and informal care networks [11] have significant effects on the use of formal services. When it comes to meal assistance service alone, the amount of time a family spends preparing meals also influences decisions on meal service use. However, owing to data limitations, we were unable to include these variables in our model, which may influence the results. Second, our survey data cannot further identify the amount of service used by elderly individuals, but some researchers have reported that the factors affecting whether elderly individuals use services and the amount of service used by elderly individuals are not exactly the same [12].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.G. and Y.T.; methodology, X.G.; software, X.G.; formal analysis, X.G.; writing—original draft preparation, X.G. and Y.T.; writing—review and editing, X.G. and Y.T.; supervision, Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Foundation in China, grant number 21CRK002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful remarks.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, Y.; Sun, Y. A study on the benefit groups and development trend of home care service in China: An empirical study based on three-wave CLASS data. J. Fujian Prov. Comm. Party Sch. CPC 2021, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Meng, Q.; Yang, P.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Nowcasting and forecasting the care needs of the older population in China: Analysis of data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e1005–e1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Zhang, Q. Analysis of the caregiving trend and caregiving effect of children caring for the disabled elderly. Econ. Perspect. 2018, 92–105. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4d8R2eTuy_ktMIfLKC3pjC0g0ZepA2MU-_hFveCkG6t2MQQiHIbJPPXyEXyYEHoFA5rI9V_ek8FIKdD-C4Ds2cJx7HK1nebf5EWmNGqZugDReEYpDfYuAmeRRtI6I8vWmSGsLFoWDQc-R9622R2Bg7vXLpLv4tieFNwnCkT_NTbJ_BXWAYws0Y_yFLjwGoLtbwfp0yxLYWU=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Chen, N.; Deng, M.; Wang, C. Research on the main body of home-based care service providers for disabled elderly in China. Med. Soc. 2020, 33, 46–49+77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Eom, K.; Matchar, D.B.; Chong, W.F.; Chan, A.W. Community-based long-term care services: If we build it, will they come? J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.; McFall, S. The effect of caregiver’s burden on change in frail older persons’ use of formal helpers. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1991, 32, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, A.; Yue, N.; Lin, S.; Zhang, R. Caregiving burden and demands for respite services among family caregivers of disabled elderly. J. Nurs. Sci. 2022, 37, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q.; He, Z.; Zeng, Y. Study on the preference patterns of home-based care services for the older adults and its influencing factors. Northwest Popul. J. 2023, 44, 58–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Penning, M. The determinants of informal, formal, and mixed in-home care in the Canadian context. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 1692–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.; Newman, J.F. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Meml. Fund Q. Health Soc. 1973, 51, 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Song, L.; Huang, J. Determinants of long-term care services among disabled older adults in China: A quantitatitive study based on Andersen behavioral model. Popul. Res. 2017, 41, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, D.M.; Noelker, L.S. The influence of family caregivers on elder’s use of in-home services: An expanded conceptual framework. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1987, 28, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bookwala, J.; Zdaniuk, B.; Burton, L.; Lind, B.; Jackson, S.; Schulz, R. Concurrent and long-term predictors of older adults’ use of community-based long-term care services: The caregiver health effects study. J. Aging Health 2004, 16, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wu, S. Factors affecting caregivers willingness to use long-term care services. J. Popul. Stud. 2006, 32, 83–121. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, R.H.; Roberto, K.A. Location matters: Disparities in the likelihood of receiving services in late life. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2021, 93, 653–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Li, G.; Zhong, X.; Ye, X.; Qiu, H. Using status and influencing factors of home-based care services for older adults in Putian Fujian Province. Northwest Popul. J. 2019, 40, 101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lehning, A.J.; Kim, M.H.; Dunkle, R.E. Facilitators of home and community-based service use by urban African American elders. J. Aging Health 2013, 25, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddart, H.; Whitley, E.; Harvey, I.; Sharp, D. What determines the use of home care services by elderly people? Health Soc. Care Community 2002, 10, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Liang, Y. Service utilization and policy optimization of the home care services for the urban older adults: A latent class analysis based on potential category. J. Shanghai Adm. Inst. 2023, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wen, W. Complement or substitution: Family care and community home-based care services. Chin. J. Health Policy 2021, 14, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Henning-Smith, C.; Lahr, M.; Casey, M. A national examination of caregiver use of and preferences for support services: Does rurality matter? J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 1652–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wang, Y. Determinants of utilization of social care service for older persons in China. Popul. Res. 2017, 41, 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Tang, Y. Association Between Community Elderly Care Services and the Physical and Emotional Burden of Family Caregivers of Older Adults: Evidence from Beijing, China. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2024, 99, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumamoto, K.; Arai, Y.; Zarit, S.H. Use of home care services effectively reduces feelings of burden among family caregivers of disabled elderly in Japan: Preliminary results. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, W.; Park, M.S. Respite service use among dementia and nondementia caregivers: Findings from the National Caregiving in the US 2015 Survey. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2022, 41, 1557–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Wang, Y. Research on the income structure and income inequality of older adults. Soc. Sci. Beijing 2021, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Zhao, J. How to enjoy equal old age: Pension and urban-rural income gap of older adults. Popul. Econ. 2022, 74–86. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.1115.f.20211216.1122.003 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Li, K.; Tang, D.; Liu, X.; Xu, Y. Review of the application of Barthel Index and modified Barthel Index in mainland China. Chin. J. Rehabil. Med. 2009, 24, 737–740. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H.; Thomson, C.; Thompson, C.; Fine, M. Why caregivers of people with dementia and memory loss don’t use services. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. How education promotes older adults’ service utilization of social elder care: Based on the evidence of Beijing. Lanzhou Acad. J. 2018, 187–198. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4d8R2eTuy_n4bnYD7odjo6eW-z3yabGkpaZzv7tEGYERnJiHuNzvATo1YYNRvuZOnOrdbXwyhWpM2ZRxalLsagAm2Nwi7YN5c-7G3fcGIv03if6CRGNaCakUX6rzRBp6gWVwCNw3gP5U9SGd49D3rPDuekNRZFuC2a72CBIzhxbwdgs60xTLckfPPT1eMLOT0PTBXS0Dveo=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Ying, T.; Tang, J.; Wang, K.; Lü, J. Study on the consumption decision-making model of commercial senior services from the perspective of family power relationship. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2020, 50, 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Keith, P.M.; Wacker, R.; Collins, S.M. Family influence on caregiver resistance, efficacy, and use of services in family elder care. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2009, 52, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C. A role engagement model of elder care. Chin. J. Sociol. 2007, 114–141+208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Joseph, W.S. Types of family care for older persons and family relationships in caregiving: A field study of family care for older persons. Sociol. Stud. 2000, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The People’s Government of Beijing Municipality. Available online: https://www.beijing.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengcefagui/qtwj/201110/t20111015_567088.html (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Leocadie, M.-C.; Roy, M.-H.; Rothan-Tondeur, M. Barriers and enablers in the use of respite interventions by caregivers of people with dementia: An integrative review. Arch. Public Health 2018, 76, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H.; Ming, Y.; Chang, T.-H.; Yen, Y.-Y.; Lan, S.-J. The Needs and Utilization of Long-Term Care Service Resources by Dementia Family Caregivers and the Affecting Factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Tang, Y. Caregiving burden profile of the family caregivers of Beijing disabled elderly: Patterns and influencing factors. Popul. Dev. 2024, 30, 110–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.-K.; Kwan, A.Y.-H.; Ng, S.H. Impacts of filial piety on preference for kinship versus public care. J. Community Psychol. 2006, 34, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-I.; Hasche, L.; Lee, M.J. Service use barriers differentiating caregivers’ service use patterns. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 1307–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).