A Framework for a Sustainable Archaeology Field School in South Florida

Abstract

1. Introduction

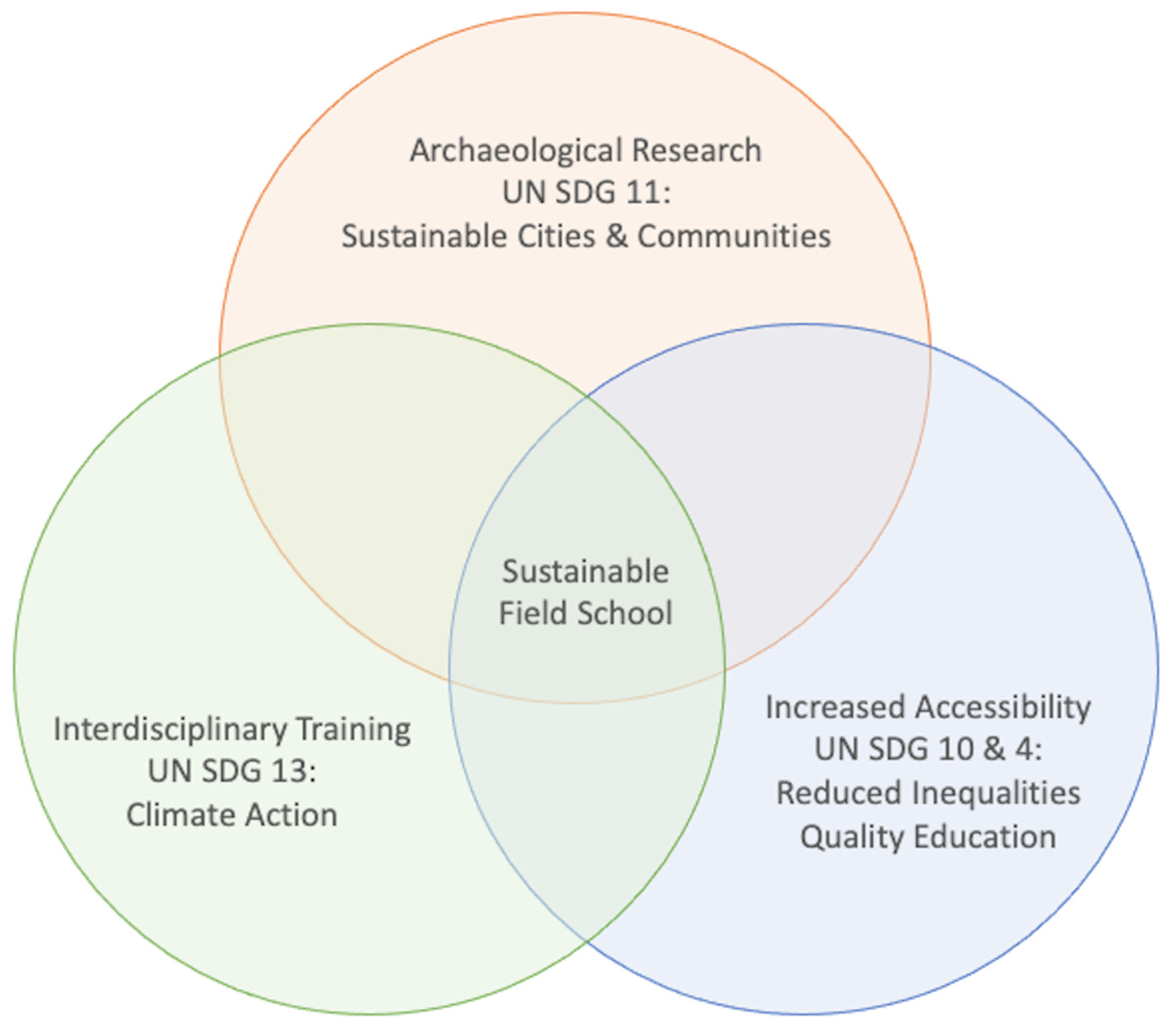

2. The Sustainable Field School

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. Archaeological Research

2.3. Interdisciplinary Training

2.4. Increased Accessibility to Students

3. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fredericksen, C. Archaeology out of the classroom: Some observations from the Fannie Bay Gaol field school, Darwin. Aust. Archaeol. 2005, 61, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.; Saitta, D.J. Teaching the craft of archaeology: Theory, practice, and the field school. Int. J. Hist. Archaeol. 2002, 6, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society for American Archaeology Archaeology as a Career. Available online: https://www.saa.org/about-archaeology/archaeology-as-a-career (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Register of Professional Archaeologists Guidelines & Standards for Field Schools. Available online: https://rpanet.org/field-school-standards (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Carson, S. Targeting critical thinking skills in a first-year undergraduate research course. J. Microbiol. Biol. Educ. 2015, 16, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, S.; Hancock, M.P.; McCullough, J. Benefits of undergraduate research experiences. Science 2007, 316, 548–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennison, L.A. Evaluation of the Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) Sites Program. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, J.A. Council on undergraduate research: A resource (and a community) for science educators. J. Chem. Educ. 1997, 74, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecher, A.L.; Eichbauer, M.; Schneider, K.; Young, L. A Regional Ecosystem that Helps Undergraduate Researchers Flourish. Eos 2023, 104, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Register of Professional Archaeologists Certified Field Schools. Available online: https://rpanet.org/certified-field-schools (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- U.S. Office of Personnel Management Archaeology Series 0193. Available online: https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/general-schedule-qualification-standards/0100/archeology-series-0193/ (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Joe, R. ShovelBums. Available online: http://www.shovelbums.org/index.php/2015-02-23-16-25-08/current-jobs (accessed on 9 July 2024).

- Heath-Stout, L.E.; Hannigan, E.M. Affording archaeology: How field school costs promote exclusivity. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2020, 8, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, J.H.; Klein, T.H. Forecast for the US CRM Industry and Job Market, 2022–2031. Adv. Archaeol. Pract. 2022, 10, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Forum: Innovations in Archaeological Field Schools. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 2012, 12, 22–40.

- Kansa, S.W.; Reifschneider, M.; Byram, S.; Gonzalez, A.; Hastorf, C.; Lightfoot, K.; Tripcevich, N.; Tung, B. A Paid Archaeological Training Program for Commuter Students. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 2024, 24, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong Minkoff, M.; Pasch, C.; McCague, E.; Reeves, M. Focusing on Accessibility and Anti-Racism in the Montpelier Field School. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 2024, 24, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Esdale, J.; Gal, R. Archaeological Investigations in Anaktuvuk Pass: Nunamiut Students Uncover their Past. Alaska Park Sci. 2006, 5, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, C. Enfulletv-Mocvse in Archaeology Field School (Muskogean)-Summer 2025. Available online: https://anthropology.uga.edu/enfulletv-mocvse-archaeology-field-school-muskogean-summer-2025 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Cipolla, C.N. Connecticut: Mohegan—Institute for Field Research. Available online: https://www.archaeological.org/fieldwork/mohegan-archaeological-field-school-connecticut-us-institute-for-field-research/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- General Assembly Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Wiek, A.; Withycombe, L.; Redman, C.L. Key competencies in sustainability: A reference framework for academic program development. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 6, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers-Rigsby, S.; Napora, K.; Lecher, A.L.; Fenn, M.; Sullivan, J.; De Witt, P. “Your Program Was the Only Field Experience I Had”: Using Partnerships to Collaborate for A Locally Accessible Field School at the Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse Outstanding Natural Area, Florida. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 2024, 24, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- The Bureau of Land Management Our Mission. Available online: https://www.blm.gov/about/our-mission#:~:text=The Bureau of Land Management%27s,of present and future generations (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Florida Network of Public Archaeology Centers; Florida Statutes, 2023; Chapter 267.145. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/florida/2023/ (accessed on 10 July 2024).

- Ayers-Rigsby, S.; Kangas, R.; Dietrich, M.; Fenn, M.; Lincoln, V.; Higgins, K.; Schneider, A. 2020 Interim Report: Jupiter Inlet Outstanding Natural Area; Florida Public Archaeology Network: Davie, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, B.; Schmitt, C.; Cole-Will, R. Third Space Pedagogy in Archaeology: Exploring Climate Change, Partnerships, and Site Stewardship in Wabanaki Homeland, Maine. SAA Archaeol. Rec. 2024, 24, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ropp, A. Cultural Intertidal and Riverine Education: Using Field Schools to Incorporate Climate Change into Historical Archaeological Research. Hist. Archaeol. 2023, 57, 532–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsen, H.; Koch Madsen, C.; Nielsen, M. Arctic Vikings Field School- Igaliku, South Greenland—Institute for Field Research. Available online: https://www.archaeological.org/fieldwork/arctic-vikings-field-school-igaliku-south-greenland-institute-for-field-research/ (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Szremski, K. Archaeology Field School in Peru. Available online: https://researchops.web.illinois.edu/opportunity/archaeology-field-school-peru (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Nagarajan, S.; Khamaru, S.; De Witt, P. UAS based 3D shoreline change detection of Jupiter Inlet Lighthouse ONA after Hurricane Irma. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 9140–9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecher, A.L.; Acevedo Montalvo, G.; Watson, A. Documenting the effects of diagenesis on bone artifacts in coastal Florida through wetting experiments. Southeast. Archaeol. 2023, 42, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecher, A.L.; Watson, A. Danger from beneath: Groundwater–sea- level interactions and implications for coastal archaeological sites in the southeast US. Southeast. Archaeol. 2021, 40, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers-Rigsby, S.; Kangas, R.; Savarese, M.; Ransom, J. Act local: Climate-change poicy at the county level in South Florida. Hist. Archaeol. 2023, 57, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecher, A.L.; Vokhshoori, N.; Watson, A. New Approaches to Using Old Artifacts: Advances in Oceanography-Archeology Research. Limnol. Oceanogr. Bull. 2024, 33, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandweiss, D.H.; Kelley, A.R. Archaeological contributions to climate change research: The archaeological record as a paleoclimatic and paleoenvironmental archive. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2012, 41, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland-Lulewicz, I.; Thompson, V.D. Calusa socioecological histories and zooarchaeological indicators of environmental change during the Little Ice Age in southwestern Florida, USA. J. Isl. Coast. Archaeol. 2021, 19, 113–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rick, T.C.; Lockwood, R. Integrating Paleobiology, Archeology, and History to Inform Biological Conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 27, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietl, G.P.; Durham, S.R.; Clark, C.; Prado, R. Better together: Building an engaged conservation paleobiology science for the future. Ecol. Solut. Evid. 2023, 4, e12246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougeon, R. UWF Terrestrial Field School. Available online: https://uwf.edu/cassh/departments/anthropology/field-schools/2024-field-schools/archaeology-field-schools/#d.en.274592 (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Cramb, J. UAF Chena Townsite Archaeological Field School; UAF: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmeyer, S.J.; Atchison, C.; Collins, T.D. Using mobile technologies to enhance accessibility and inclusion in field-based learning. GSA Today 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanauer, D.I.; Graham, M.J.; Hafull, G.F. A Measure of College Student Persistence in the Sciences (PITS). CBE Life Sci. Educ. 2016, 15, ar54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.M.; Sullivan, L.P.; Marrinan, R.A. (Eds.) Grit-Tempered: Early Women Archaeologists in the Southeastern United States; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2023; ISBN 9780813080468. [Google Scholar]

- Fulkerson, T.J.; Tushingham, S. Who dominates the discourses of the past? Gender, occupational affiliation, and multivocality in North American archaeology publishing. Am. Antiq. 2019, 84, 379–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blickenstaff, J.C. Women and science careers: Leaky pipeline or gender filter? Gend. Educ. 2005, 17, 363–386. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lecher, A.L.; Napora, K.G.; Ayers-Rigsby, S.; Fenn, M.; Lehman, M.; De Witt, P.; Sullivan, J. A Framework for a Sustainable Archaeology Field School in South Florida. Sustainability 2025, 17, 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020588

Lecher AL, Napora KG, Ayers-Rigsby S, Fenn M, Lehman M, De Witt P, Sullivan J. A Framework for a Sustainable Archaeology Field School in South Florida. Sustainability. 2025; 17(2):588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020588

Chicago/Turabian StyleLecher, Alanna L., Katharine G. Napora, Sara Ayers-Rigsby, Malachi Fenn, Melissa Lehman, Peter De Witt, and John Sullivan. 2025. "A Framework for a Sustainable Archaeology Field School in South Florida" Sustainability 17, no. 2: 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020588

APA StyleLecher, A. L., Napora, K. G., Ayers-Rigsby, S., Fenn, M., Lehman, M., De Witt, P., & Sullivan, J. (2025). A Framework for a Sustainable Archaeology Field School in South Florida. Sustainability, 17(2), 588. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17020588