From Social Stability to Social Sustainability: Comparing SIA and SSRA in an ADB Loan Project in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. SIA and Social Sustainability

2.1.1. Research on SIA

2.1.2. Research on Social Sustainability

2.1.3. SIA Under Social Sustainability

2.2. From SIA to SSRA

2.3. Previous Comparative Research Between SIA and SSRA

3. Research Framework

4. Material and Methodology

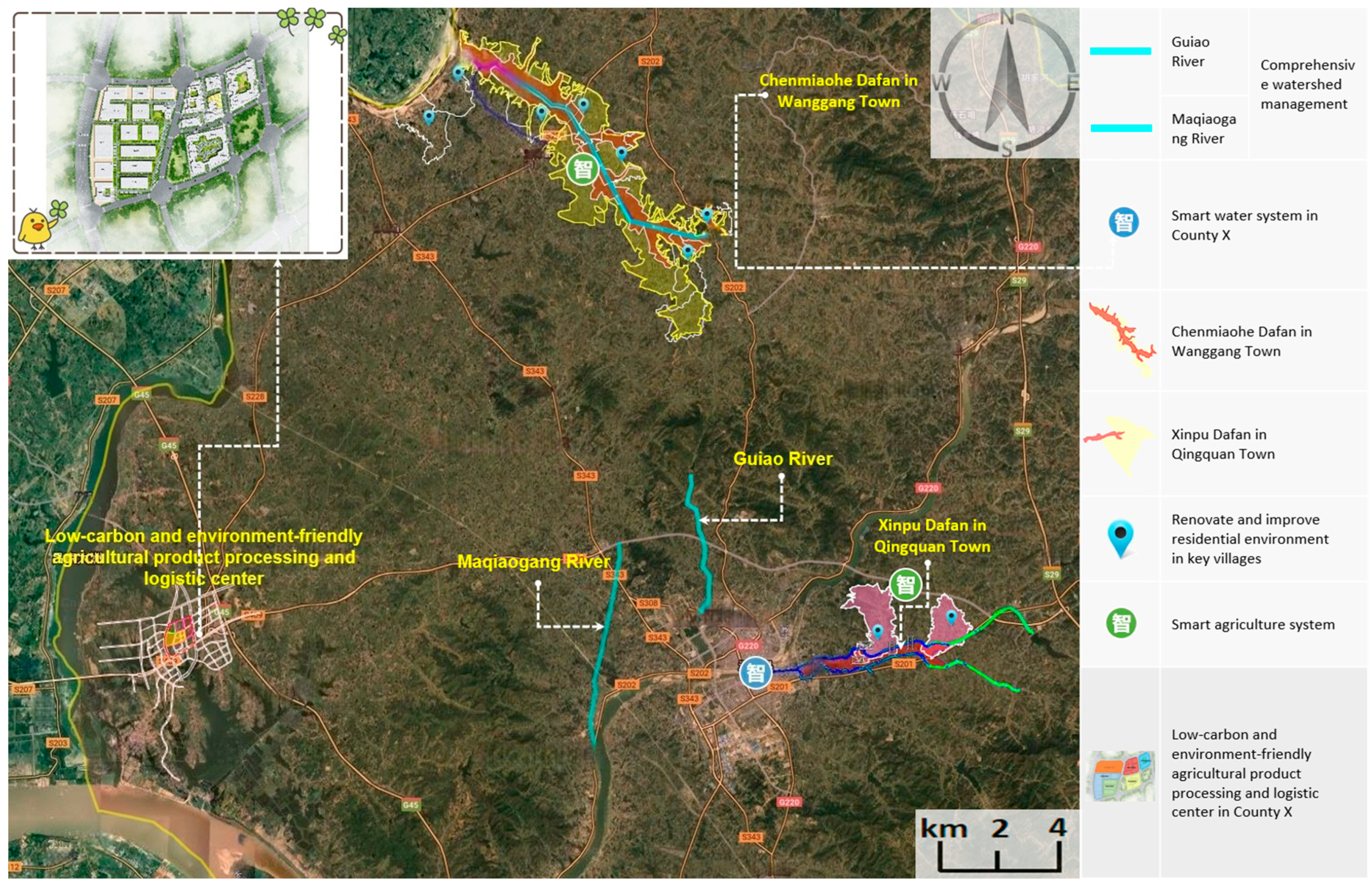

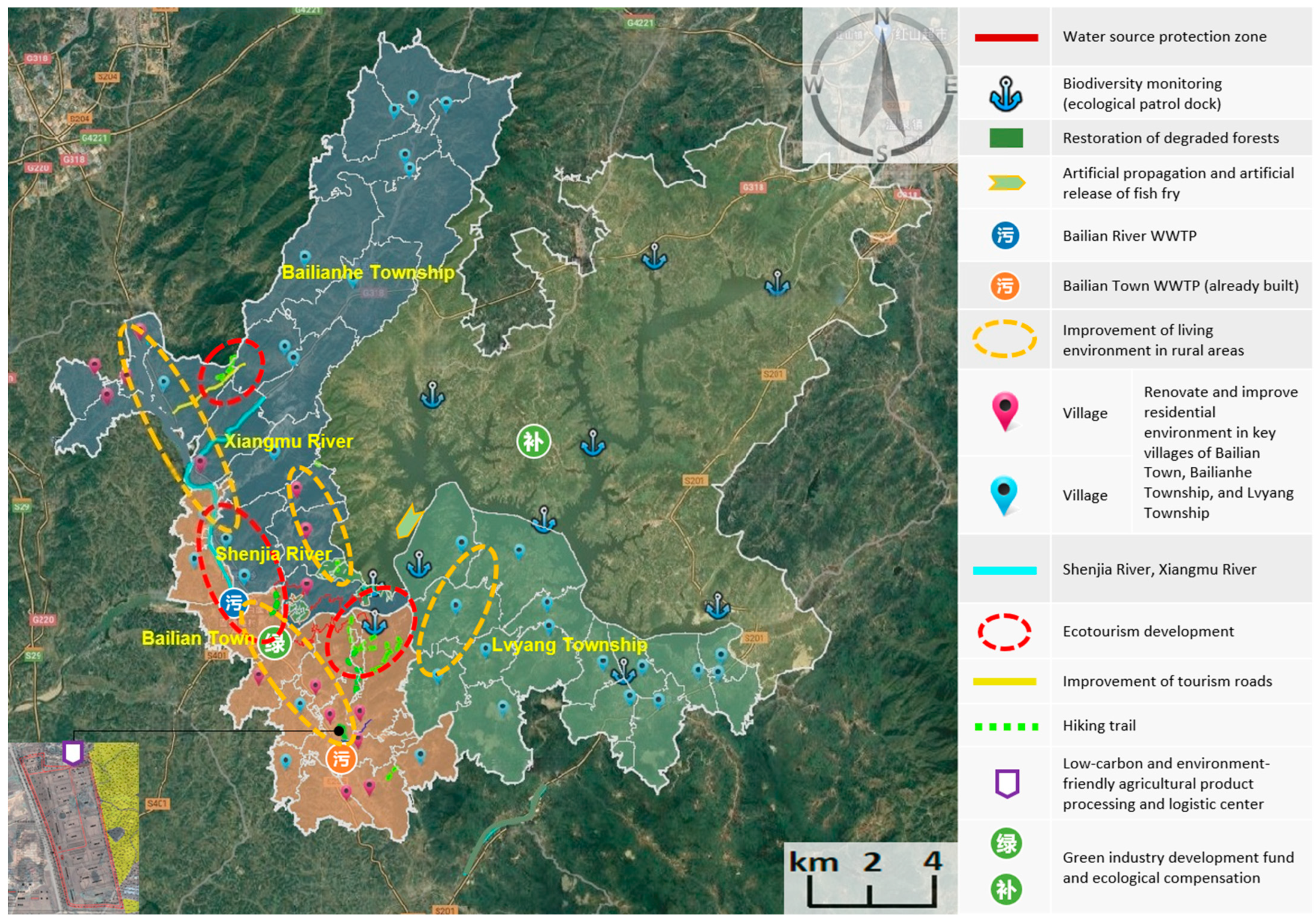

4.1. Basic Information of the Project Case

4.2. Considerations for Selecting Project Case

4.3. Considerations Regarding the Author’s Roles

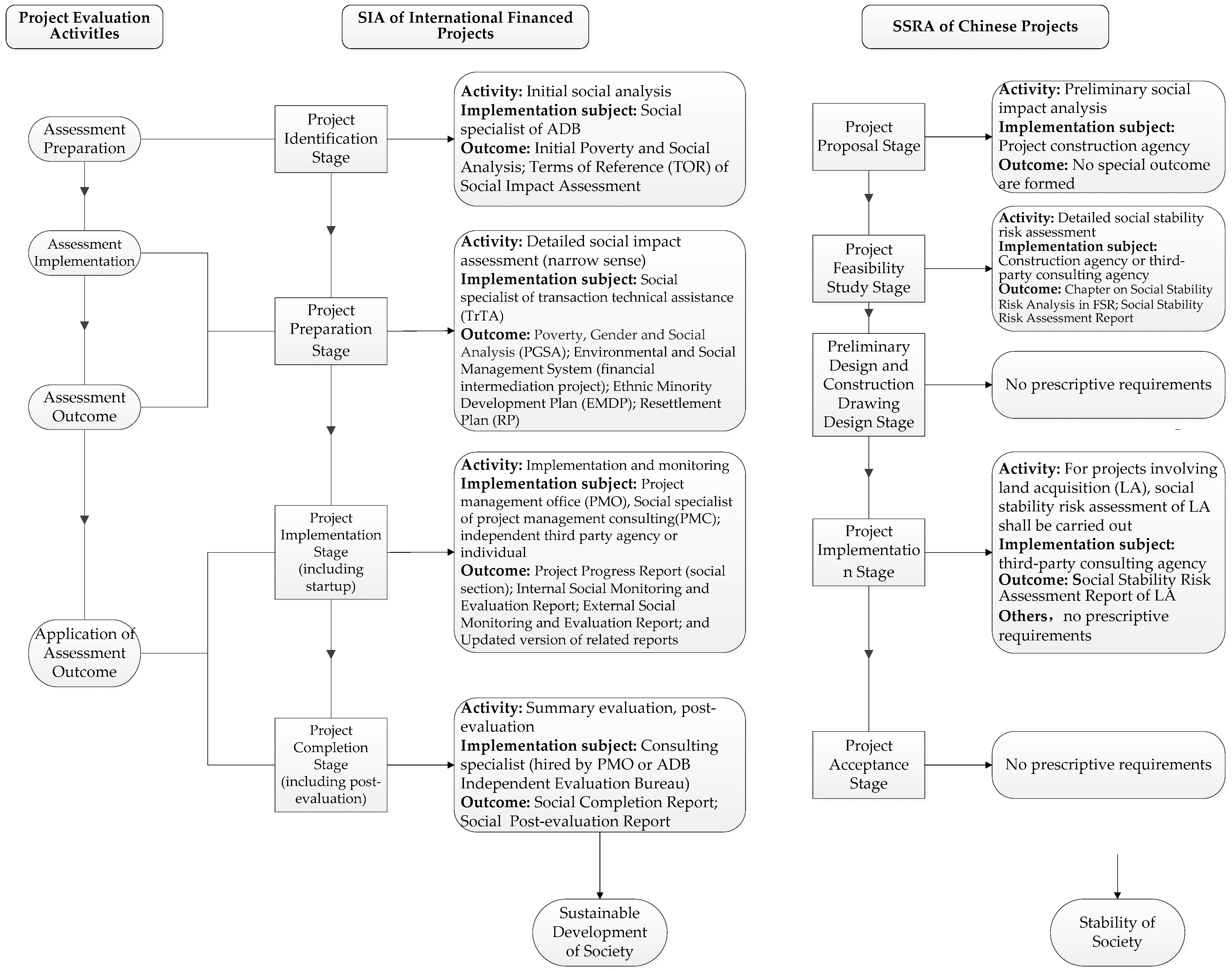

4.4. The Basic Situation of SSRA and SIA in the Project Case

5. SIA and SSRA in the Project

5.1. SIA

5.1.1. Assessment Basis

5.1.2. Assessment Content

5.1.3. Assessment Method and Conclusions

5.1.4. Application of Assessment Outcome

5.2. SSRA

5.2.1. Assessment Basis

5.2.2. Assessment Contents

5.2.3. Assessment Method and Conclusions

5.2.4. Application of Assessment Outcomes

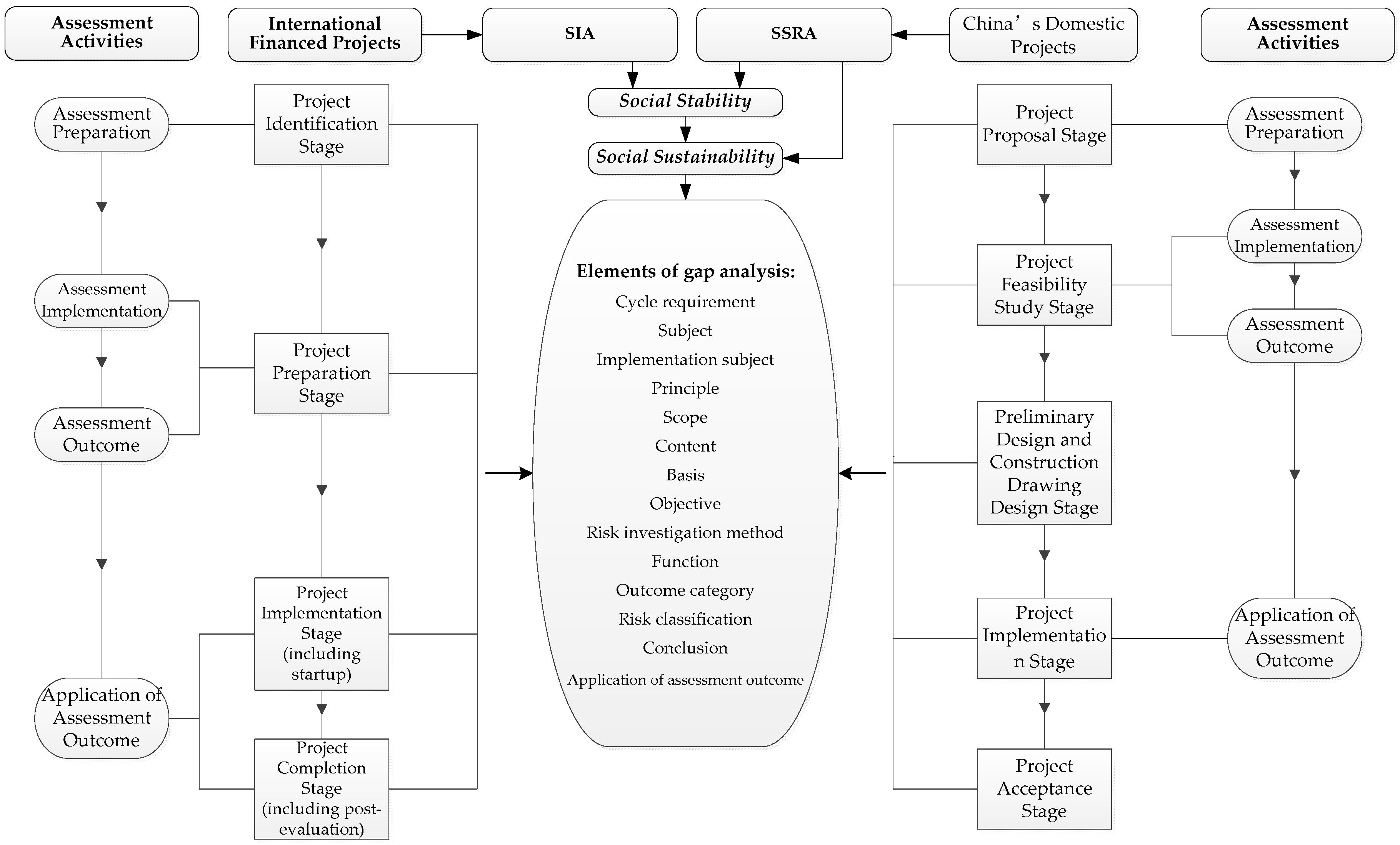

6. Discussion: Gap Analysis Between SIA and SSRA

7. Conclusions

7.1. Research Findings

7.2. Research Implications

7.3. Institutional Analysis Behind the Differences

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIA | Social impact assessment |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ADB | Asian Development Bank |

| SSRA | Social stability risk assessment |

| IAIA | International Association for Impact Assessment |

| WB | World Bank |

| RSIA | Risk and social impact assessment |

| SRA | Social risk assessment |

| S-LCA | Social life cycle assessment |

| CA | Constellation analysis |

| TOR | Terms of Reference |

| TrTA | Transaction technical assistance |

| PGSA | Poverty, Gender and Social Analysis |

| EMDP | Ethnic Minority Development Plan |

| RP | Resettlement Plan |

| PMO | Project management office |

| PMC | Project management consulting |

| LA | Land acquisition |

References

- Berkey, L.J. The Concept, Process and Method of Social Impact Assessment; Yang, Y., Translator; China Environmental Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011; p. 213. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Esteves, A.M. New Trend of Social Impact Assessment; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y., Translators; China Environment Press: Beijing, China, 2015; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Yang, Q.; Xie, D.; Xie, J.; Lu, C.; Wang, Z. Retrospection and expectation of social assessment impact of project engineering. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2007, 23, 588–593. [Google Scholar]

- Peraki, L.; Kontouli, N.; Gkika, A.; Petrakli, F.; Koumoulos, E.P. Expanding Social Impact Assessment Methodologies Within SDGs: A Case Study on Novel Wind and Tidal Turbine Blades Development. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Research on theoretical framework of social impact assessment for urban integrated transportation hubs. In Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Systems Science, Management Science & System Dynamics, Shanghai, China, 29–31 May 2009; Wang, Q., Zhang, X.D., Xu, B., Wu, B.C., Eds.; Publishing House Electronics Industry: Beijing, China; pp. 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, L.; Sun, L. Indexes framing and measurement of social impact assessment of high way based on the sustainable development. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2008, 30, 170–172, 191. [Google Scholar]

- Mottee, L.K.; Arts, J.; Vanclay, F.; Howitt, R.; Miller, F. Limitations of technical approaches to transport planning practice in two cases: Social issues as a critical component of urban projects. Plan. Theory Pract. 2020, 21, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; Hanna, K.; Noble, B.; Gergel, S.E.; Nikolakis, W. Assessing the cumulative social effects of projects: Lessons from Canadian hydroelectric development. Environ. Manag. 2022, 69, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, S.; Zhang, S. Applying Logical framework approach in hydropower construction project social impacts post-project assessment. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. 2009, 31, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Shuang, X. Entropy combination weight and grey clustering model-based assessment on social impact from river regulation project. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2017, 48, 163–167. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmayr, A.; Verhofstadt, E.; Van Ootegem, L.; Thomassen, G.; Taelman, S.E.; Dewulf, J. Exploring the global and local social sustainability of wind energy technologies: An application of a social impact assessment framework. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpe, L.; Seo, S.B. An Appraisal of Environmental and Social Impact Assessment in Ethiopia: The Case of Meta Abo Brewery. Sustainability 2022, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Sun, Z.; Tang, L.; Yu, L. Study on basic framework of disaster social impact assessment. J. Nat. Disasters. 2015, 24, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J.C.; Taylor, C.N.; Aley, J.P. Social assessment of inhabited islands for wildlife management and eradication. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 24–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S.L.; Hinchliffe, S.; McDonald, R.A. Invasive species management will benefit from social impact assessment. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colburn, L.L.; Jepson, M. Social indicators of gentrification pressure in fishing communities: A context for social impact assessment. Coast. Manag. 2012, 40, 89–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J. Principles and guidelines for social impact assessment: A critical review on the US case. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2007, 16, 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J. Social impact assessment on national development projects in Korea. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2010, 19, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, L.M.; Hanna, K.; Noble, B.; Nikolakis, W.; E Gergel, S. Capacity needs for assessing the cumulative social effects of projects. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2023, 41, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momtaz, S. Institutionalizing social impact assessment in Bangladesh resource management: Limitations and opportunities. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonie, R. Social impact assessment models. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2010, 6, 22–29. Available online: https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/wos/alldb/full-record/WOS:000274458800002 (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Delgado, A.; Motellanos, P.; Rosario, E.; Zuloaga, L. Social impact assessment on a renewable energy project: A case study in Peru. In Proceedings of the IEEE-PES Transmission & Distribution Conference and Exposition Latin America, Limassol, Peru, 18–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Alicea, R.J.; Fu, K. Systematic map of the social impact assessment field. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Renn, O.; Vanclay, F.; Hoffmann, V.; Karami, E. A framework for combining social impact assessment and risk assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2013, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, Z.; Lynch, N. Financial modelling strategies for social life cycle assessment: A project appraisal of biodiesel production and sustainability in newfoundland and labrador, Canada. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.; Russi, D.; Bala, A.; Finkbeiner, M.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P. Integration of Social Aspects in Decision Support, Based on Life Cycle Thinking. Sustainability 2011, 3, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunuwila, P.; Daigo, I.; Rodrigo, V.H.L.; Liyanage, D.J.T.S.; Gong, W.T.; Hatayama, H.; Shobatake, K.; Tahara, K.; Hoshino, T. Social Life Cycle Assessment Methodology to Capture “More-Good” and “Less-Bad” Social Impacts—Part 1: A Methodological Framework. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huesca-Pérez, M.E.; Sheinbaum-Pardo, C.; Köppel, J. From global to local: Impact assessment and social implications related to wind energy projects in Oaxaca, Mexico. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2018, 36, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Jin, W.; Shen, J.; Zhang, D.; Xia, J. Social impact assessment and social cost analysis of construction projects. China Civ. Eng. J. 2022, 55, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.N.; Mackay, M.; Perkins, H.C. Social impact assessment and (realist) evaluation: Meeting of the methods. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabre, I.; Okereke, C. Palm oil, power, and participation: The political ecology of social impact assessment. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2020, 3, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dendena, B.; Corsi, S. The environmental and social impact assessment: A further step towards an integrated assessment process. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 108, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, H.; Cho, K. A study on the improvement scheme of environmental impact assessment in social environment. J. Environ. Impact Assess. 2012, 21, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Our Common future (The Brundtland Report); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987; p. 43. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Husgafvel, R. Exploring social sustainability handprint-part 2: Sustainable development and sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.G.; Nycander, G. Sustainable neighbourhoods—A qualitative model for resource management in communities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1997, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pellegrini, P.; Wang, H. Comparative Residents’ Satisfaction Evaluation for Socially Sustainable Regeneration—The Case of Two High-Density Communities in Suzhou. Land 2022, 11, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, T.; Kraslawski, A.; Heiduschke, R.; Repke, J.U. Indicators of Social Sustainability for Wastewater Treatment Processes. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Foundations of Computer-aided Process Design, Cle Elum, WA, USA, 13–17 July 2014; Eden, M.R., Siirola, J.D., Towler, G.P., Eds.; pp. 723–728. [Google Scholar]

- Akcali, S.; Cahantimur, A. The pentagon model of urban social sustainability: An assessment of sociospatial aspects, comparing two neighborhoods. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larimian, T.; Sadeghi, A. Measuring urban social sustainability: Scale development and validation. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2021, 48, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owodunni, O. Social sustainability in technologically-supported product realisation process. In Proceedings of the 15th Global Conference on Sus-tainable Manufacturing, Technion Inst Technol, Haifa, Isreal, 25–27 September 2017; Seliger, G., Wertheim, R., Kohl, H., Shpitalni, M., Fischer, A., Eds.; Elsevier Science BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; pp. 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Opp, S.M. COVID-19 and social sustainability: The case of Mauritius. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 1521–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Anbanandam, R. Development of social sustainability index for freight transportation system. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbring, G.; Rybchinski, T. Social Sustainability and Its Indicators through a Disability Studies and an Ability Studies Lens. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4889–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, R.H.W.; Peterson, N.D.; Arora, P.; Caldwell, K. Five Approaches to Social Sustainability and an Integrated Way Forward. Sustainability 2016, 8, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, P.; Cord, L.; Cuesta, J.; Espinoza, S.A.; Larson, G.; Woolcock, M. Social Sustainability in Development; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, A.M.; Franks, D.; Vanclay, F. Social impact assessment: The state of the art. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2012, 30, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Social Report 2025: A New Policy Consensus to Accelerate Social Progress. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2025. Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/2025-04/250422%20BLS25022%20UDS%20UN%20World%20Social%20Report%20WEB.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- World Bank. Social Sustainability and Inclusion Overview. Retrieved 18 March 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/socialsustainability/overview (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- World Bank. Social Cohesion and Resilience. 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/social-cohesion-and-resilience (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Vanclay, F.; Esteves, A.M.; Aucamp, I.; Franks, D. Social Impact Assessment: Guidance for Assessing and Managing the Social Impacts of Projects; International Association for Impact Assessment: Fargo, ND, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Principles for social impact assessment: A critical comparison between the international and US documents. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 26, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, B.; Kim, P.; Boivin, M.; Thiffault, É. Socio-cultural indicators for bioenergy: A survey-based review. Can. J. For. Res. 2025, 55, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S. Theoretical infertility and transcendence path of social stability risk assessment research-based on the perspective of institutional analysis. Chin. Public Adm. 2023, 8, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A. Social evaluation: The application of sociology in projects. Acad. Bimestris. 2002, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A. Project social evaluation from a paradigm perspective. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2003, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D. Analysis on social evaluation of investment projects. China Eng. Consult. 2004, 47, 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. Concerns of social evaluation of international financed projects. China Investig. 2013, 54–55. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/nzkhtml/xmlRead/trialRead.html?dbCode=CJFD&tableName=CJFDTOTAL&fileName=ZGTZ201311022&fileSourceType=1&appId=KNS_BASIC_PSMC&invoice=iR6MYD8YGCo4DmmHwq3CmtLrSZKf6LePm4IRJkDEfUlr8LoDs5ZLkZWvAUWOUlkt9u1FyMEy9HDhPwMQO9cFY4kFY6WC7k5lF1L9hOzkAJe3a9C9+lHwR/h2SCy67b10e87WAMwhqe7vnoYrwFQqGLnHX2DM2b3tmUYjnCjMGPU= (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Chen, S.; Shen, Y. Comparative study on social impact assessment of World Bank-funded construction projects and social risk assessment of China’ s construction projects. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 44, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Shi, G.; Zhang, R. Social stability risk assessment: Status, trends and prospects —A case of land acquisition and resettlement in the hydropower sector. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2019, 39, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Shi, G. The source of social risk assessment and governance and the strategy of transformation. Nanjing Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Shi, G. Value transformation and methodological innovation in social impact assessment of public policies. Jiangsu Soc. Sci. 2024, 2, 103–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, C.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, G.; Xia, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, W. Economics Research Methodology: Theory and Practice; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2015; p. 190. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Subprojects and Activities |

|---|---|

| Output 1: Enhancement of institutional capacity for ecosystem protection and climate-smart development | |

| 1 | Huanggang Climate Change Adaptation and Carbon-Neutrality Action Plan *; |

| 2 | Bailian River gross ecological product accounting and value realization mechanism study; |

| 3 | Smart water system in County X; |

| 4 | Smart agricultural platform established in County X; |

| 5 | Smart environment management system in District B; |

| 6 | Job skills training for farmers and fishers, including but not limited to (1) skills training for better job opportunities; (2) public awareness of environmental and biodiversity protection, eco-tourism, climate-smart agriculture etc.; (3) latest supporting policies for rural development; |

| 7 | Biodiversity survey and monitoring in Bailian River Reservoir; |

| 8 | Project implementation consulting services and capacity building *. |

| Output 2: Improvement of rural environment and business opportunities in ecosystem protection | |

| 9 | Eco-compensation mechanism in Bailian River Basin |

| 10 |

Bailian River Reservoir ecological protection

|

| 11 | Comprehensive watershed management |

| A | District B

|

| B | County X

|

| 12 | Improvement of living environment in rural areas |

| A | District B

|

| B | County X

|

| 13 | Ecotourism development |

| A | District B

|

| B | County X

|

| Output 3: Demonstrate climate-smart green rural development | |

| 14 | Climate-smart agricultural production and piloting in County X

|

| 15 | Low-carbon and environment-friendly agricultural product processing and logistic center in District B; |

| 16 | Low-carbon and environment-friendly agricultural product processing and logistic center in County X. |

| Assessment Stage | Assessment Aspect | SIA | SSRA | Comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle requirement | Broadly speaking, SIA runs through the whole life cycle of a project. Take the ADB financed project as an example. (a) Identification stage: Initial social analysis; (b) Preparation stage: Detailed social assessment analysis (narrow sense); (c) Startup stage: Decide, as appropriate, whether to update reports on SIA; (d) Implementation stage: Internal monitoring and updating of social development action plan, gender action plan, resettlement plan, and ethnic minority development plan, etc., conducted by Project Management Office (PMO), and external monitoring and evaluation by independent third party; (e) Completion stage (including post-evaluation): Summary assessment and, if necessary, post-evaluation on social aspect. | SSRA is mainly carried out in the early stage of a project, that is, the feasibility study stage. There are no prescriptive or mandatory requirements for the implementation stage or the completion and acceptance stage. | Broadly speaking, SIA accompanies the whole life cycle of a project and has a longer time span, while SSRA is mainly carried out in the early stage of a project, with a shorter time span. | |

| Assessment implementation | Assessment subject | The proposed project owner | The proposed project owner | Basically consistent, and the project owner bears the ultimate responsibility for assessment conclusions. |

| Subject of assessment implementation | The subject of assessment implementation varies at different project stages. Take the ADB financed project as an example. (a) Identification stage: Social specialist in ADB; (b) Preparation stage: International and national social consulting specialists on the TrTA team. In the project preparation stage, there are two other safeguard documents closely related to SIA, namely the Ethnic Minority Development Plan (EMDP) and Resettlement Plan (RP), which need to be prepared depending on the specific impacts of the project on ethnic minority and involuntary resettlement groups. If preparation is required, it is usually carried out by a consulting team/specialist commissioned by the PMO or owner. The key elements of both reports also need to be summarized in the Poverty and Social Analysis Report. (c) Startup stage: Startup social consulting specialist hired by PMO; (d) Implementation and completion stages: Social consulting specialists from a third-party external monitoring and evaluation agency or team and from the project management consulting team hired by the PMO; (e) Post-evaluation stage: Social consulting specialist hired by the ADB Independent Evaluation Bureau. In addition to the ADB specialist, the selection of other consulting teams or specialists is based on the qualifications of specialists, who are generally scored in terms of their academic qualifications, experience in similar projects, and experience in similar locations, and the selection is highly subjective. | It can be either the project owner itself or a third-party professional assessment agency. | SIA has more staged tasks than SSRA, and the assessment implementation subjects are diverse. | |

| Assessment principle | Objectivity, scientific rigor, operability, comprehensiveness, openness and transparency, and broad participation. | Objectivity, scientific rigor, operability, comprehensiveness, openness and transparency, and broad participation. | Basically consistent; SIA more emphasizes the participation of various stakeholders, especially special groups. | |

| Assessment scope | Geographical scope: Project area, project impact area, project associated facilities/activities; Time frame: Investigation of the current situation, review of the past construction of related facilities or related activities, and prediction of the future. | Geographical scope: Focus on the project area, but also on the project impact area. Time frame: Investigation of the current situation, and prediction of the future. | SSRA has no specific requirements for past associated facility construction or related activities. | |

| Assessment contents | The social risks (including social stability risks) that may be caused by the project and the role of the project in promoting social development, with focus on the project’s social sustainable development on poverty, gender, ethnic minority, and involuntary resettlement. | Social stability risks due to project construction | SIA pays more attention to the positive benefits brought by the project and the impact on special groups than SSRA | |

| Assessment basis | SDGs, International Labour Organization Core Labour Standards, policies related to gender equality, Equator Principles, existing laws, regulations, policies, plans of borrowing countries, etc. | China’s domestic laws, regulations, policies, plans, etc. | SSRA plays a main role in identifying risk factors for social stability, and generally does not specifically benchmark international advanced concepts and standards. | |

| Risk investigation methods | Field surveys, interviews, discussions, and consultations in field research; questionnaire surveys and structured interviews in survey research; data collection and analysis; checklist method and case reference method in literature research. Emphasis is placed on the participation of various stakeholders, especially vulnerable groups, women, the elderly, and ethnic minorities. | Field surveys, interviews, discussions, and consultations in field research; questionnaire surveys and structured interviews in survey research; data collection and analysis; checklist method and case reference method in literature research. Emphasis is placed on the participation of various stakeholders. | Basically consistent. SIA pays more attention to the participation of vulnerable groups, women, the elderly, and ethnic minorities. | |

| Forecasting function | Predicting future project benefits and risks | Predicting future project social risks | Basically consistent. | |

| Assessment outcomes | Outcome categories | Take the ADB financed project as an example. (a) Identification stage: Initial Poverty and Social Analysis, Terms of Reference for Social Impact Assessment; (b) Preparation stage: Poverty, Gender and Social Analysis (PGSA), Environmental and Social Management System (ESMS, financial intermediation project), Ethnic Minority Development Plan (EMDP), Resettlement Plan (RP); (c) Startup stage: Project Progress Report (social section), Internal Social Monitoring and Evaluation Report, updated versions of relevant reports; (d) Implementation stage: Internal Social Monitoring and Evaluation Report, External Social Monitoring and Evaluation Report, updated versions of relevant reports; (e) Completion stage: Social Completion Report, Social Post-Evaluation Report | Chapter on Social Stability Risk Analysis in the Feasibility Study Report, Social Stability Risk Assessment Report, and Social Stability Risk Assessment Report on Land Acquisition (those involving land acquisition in subsequent implementation stages) | SIA has more diverse categories of outcomes. |

| Assessment conclusions—risk classification | According to the Environmental and Social Framework, the World Bank classifies all projects into four categories: high risk, moderate–high risk, moderate risk, and low risk. | The risk level is divided into three levels: high risk, moderate risk and low risk. | Overall, both approaches categorize project risk levels into three broad tiers: high, moderate, and low. (Note: institutions such as the World Bank further subdivide the moderate risk category into a “moderate–high” level) | |

| Application of assessment outcomes | The Social Development Action Plan (SDAP), Gender Action Plan (GAP), Resettlement Plan (RP), and Ethnic Minority Development Plan (EMDP) are used to manage the project’s social-related activities, including specific indicators, operational measures, and monitoring systems, such as the implementing agency, cost estimates and sources, implementation timelines, monitoring indicators, monitoring cycles, and reporting systems. | The measures and suggestions are broad and lack a monitoring system. | SIA is more directional and operable than SSRA. | |

| Assessment objective | Promotes the realization of project social benefits to achieve social sustainable development | Maintains social stability in the project area, a phased task that supports sustainable development and creates the prerequisite conditions for sustainable development. | SIA directly points to social sustainable development; while SSRA directly points to maintaining political stability and is a prerequisite for sustainable development | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pang, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Z. From Social Stability to Social Sustainability: Comparing SIA and SSRA in an ADB Loan Project in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198963

Pang Y, Chen S, He Z. From Social Stability to Social Sustainability: Comparing SIA and SSRA in an ADB Loan Project in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198963

Chicago/Turabian StylePang, Yawei, Shaojun Chen, and Zhiyang He. 2025. "From Social Stability to Social Sustainability: Comparing SIA and SSRA in an ADB Loan Project in China" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198963

APA StylePang, Y., Chen, S., & He, Z. (2025). From Social Stability to Social Sustainability: Comparing SIA and SSRA in an ADB Loan Project in China. Sustainability, 17(19), 8963. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198963