Abstract

This study investigates the impact of servant leadership on employee performance in mobile telecommunications providers, emphasizing the mediating role of organizational trust and its implications for organizational sustainability. Leadership effectiveness is particularly critical in environments where trust is limited, as it shapes both immediate performance and long-term organizational resilience. Using survey data from 375 employees across three telecom companies in Iraq, the results indicate that servant leadership is positively related to employee performance. Mediation analysis further demonstrates that organizational trust significantly transmits the effect of servant leadership on performance. These results extend current knowledge of leadership dynamics in the telecom sector and underscore the role of trust-based leadership in fostering sustainable organizational outcomes. Based on these insights, a practical framework was developed to integrate servant leadership principles into team-building initiatives, leadership development programs, and organizational systems. This framework not only supports the training of future leaders but also strengthens employee well-being, ethical culture, and long-term sustainability in the telecommunications industry.

1. Introduction

In the contemporary business environment, particularly in telecommunications, leadership and trust are an underpinning of the balance of the organization. This underpinning is seen as being important for not only competitiveness but to support the capacity for leading sustainable development goals, such as SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth) and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions) [1,2]. Effective leadership fosters the development of an organizational culture built on trust, which in turn catalyzes collaboration, drives innovation, and enhances employee engagement [3]. Among the various leadership approaches, servant leadership (SL) has emerged as particularly relevant due to its emphasis on employee well-being, empowerment, and service to others. In contrast to conventional leadership frameworks that emphasize power and dominance, servant leadership encourages an environment grounded in confidence, teamwork, and collective goals [4,5].

Servant leaders prioritize the needs and concerns of their employees, creating a sense of inclusion and belonging that strengthens teamwork, organizational commitment, and performance outcomes. Previous studies confirm the positive impact of SL on organizational outcomes, particularly its influence on employee performance (EP) [5,6,7]. Though SL has been studied significantly, how SL impacts EP is still not fully understood because we do not yet understand the mediating role of organizational trust (OT) in dynamic and emergent contexts. This evident gap in the literature is what this study seeks to address. However, the mechanisms through which SL shapes performance remain underexplored. In particular, the mediating role of organizational trust (OT) warrants deeper examination [8,9], especially in industries characterized by rapid technological advancements, environmental uncertainty, and competitive pressures such as telecommunications.

At the same time, organizations are increasingly evaluated not only on financial metrics but also on their ability to achieve sustainable growth through socially responsible and environmentally conscious practices [8,9]. In this regard, SL and OT provide a pathway to sustainability by cultivating trust-based relationships, strengthening employee engagement, and aligning human resource practices with long-term strategic goals. By embedding servant leadership principles into leadership development, organizations can build resilient cultures that contribute to sustained competitive advantage while supporting broader social and environmental objectives. Consequently, the investigation of SL, OT, and EP must be framed in light of issues related to organizational sustainability and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) agenda, with telecom organizations expected to align their practices with the global sustainable development objectives such as SDG 8, SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 16 [1,2]. Accordingly, the main research question being examined in this research is as follows: What is the impact of SL on EP through OT in the context of the Iraqi telecommunications sector, and what are the implications for organizational sustainability? This study, therefore, investigates the impact of SL on EP within mobile telecommunications providers, emphasizing the mediating role of OT and highlighting the implications for organizational sustainability.

As previously stated, comprehensive research has demonstrated a favorable correlation between SL and multiple organizational outcomes, particularly EP [5]. However, a significant research gap remains. Few studies have examined how SL influences EP through the mediating role of OT, especially in highly volatile sectors such as telecommunications. Within emerging economies such as Iraq, this relationship has been even less explored. Trust dynamics may differ significantly in such contexts due to unique cultural, economic, and institutional challenges [5,6].

The telecommunications sector represents an industry defined by rapid technological advancements, constant innovation pressures, and relentless competition. Previous studies across multiple domains have consistently highlighted the pivotal role of OT as a mediator, significantly shaping the relationship between leadership approaches and performance outcomes [6,7]. Yet, the telecom industry’s distinctive challenges—such as accelerated service introduction and the need for continuous adaptability—necessitate specialized research into leadership approaches like SL [3]. In this regard, trust should not be perceived merely as a moral virtue, but rather as a strategic organizational resource embedded in leadership frameworks, shaping institutional processes and ensuring sustainable organizational behavior [9].

Trust-related challenges are particularly acute in telecommunications, where fast-paced technological adoption requires rapid managerial responses. Trust in leadership enables quicker decision-making, empowers employees to assume active roles in change processes, and enhances organizational adaptability. This adaptive capability is essential for sustaining competitiveness in a dynamic market environment.

Within telecommunications, where employees frequently interact with customers under rapidly shifting conditions, the supportive and empowering nature of SL is particularly relevant for sustaining high levels of performance. Servant leaders create feelings of belongingness, teamwork, and innovation by meeting employee needs, all of which aid long-term sustainability of the organization. In this regard, SL is not only a means of driving employee outcomes, but also a means of embedding sustainable values into organizational culture that can directly foster overall sustainability challenges for global targets, e.g., SDG 8 and SDG 16 [1,2]. Sustainability adds an additional dimension to this discussion. Organizations are increasingly evaluated not only on financial performance but also on their ability to pursue sustainable growth through socially responsible and environmentally conscious practices [10,11]. SL and OT provide a pathway to sustainability by fostering trust-based relationships, enhancing employee engagement, and aligning human resource practices with long-term strategic goals. By embedding SL principles into leadership development, telecom organizations can build resilient cultures that promote both competitive advantage and broader sustainability objectives.

The present study addresses these critical gaps by investigating the mediating role of OT in the relationship between SL and EP, with a focus on mobile telecommunications providers in Iraq. Beyond contributing to theoretical advancements in SL and trust research. Sustainability is viewed as an overarching objective in the study, showing how leadership practices and trust mechanisms serve immediate performance consequences and contribute positively to the global sustainable development agenda, including specifically SDG 8 and SDG 16, by linking leadership practices with trust, innovation, and performance, the research offers practical frameworks for leadership development in industries facing rapid technological change, ensuring both short-term adaptability and long-term sustainability [2,11].

2. Literature Review

2.1. Servant Leadership and Employee Performance

SL highlights open communication and engagement between leaders and employees because comprehending employee needs and addressing concerns is crucial [5]. Transparent communication promotes employee collaboration and delineates roles and responsibilities, enhancing EP. Furthermore, employee performance is affected by encouraging a positive work climate, building trust, and demonstrating genuine care for colleagues [5,12]. Employees who experience appreciation and support are more likely to show loyalty and motivation towards the organization, leading to enhanced performance and involvement. Moreover, employees are more inclined to stay connected with the organization and strive to achieve excellence when they see opportunities for development and promotion [5,13]. The available empirical evidence supports the assertion that SL benefits EP in various contexts within service-oriented environments [4,14]. One study revealed a moderate positive correlation between leadership and employee performance within the telecommunication sector [14]. Another study analyzed the SL dimensions and found that the supervisor’s provision of the accountability and independence component positively impacts EP. In contrast, the empowerment dimension of SL has the most considerable influence on EP [15].

One study involving university employees revealed that SL dimensions such as love, compassion, trust, and service significantly and positively enhanced EP. However, the study found that the empowerment factor did not influence EP [5]. The findings underscore the influence of SL on organizational outcomes and employee well-being. This study has also established that SL influences not only the immediate outcomes of employees in an organization but is also an essential factor in culture change. Developing an organization’s culture is closely related to the leadership style, necessitating professionalism, effective communication, respect, tolerance, and openness from all members.

Servant leaders who prioritize the welfare and growth of employees tend to promote the virtue of getting along well with others, producing compatible employee fraternization, dignity, and respect, thereby creating understanding and loyalty in the workforce. Instead of emphasizing power over individuals, SL encourages organizations to focus on the growth of their members and diverse communities. Research has also found that organizations that embrace the SL model tend to experience less turnover, higher job satisfaction, and improved organizational performance since employees buy into the change process and are willing to work through it instead of opposing it [3,4,9].

The far-reaching consequences of the SL style for employee empowerment are a significant topic of discussion. Empowerment under SL goes beyond job autonomy rights, entailing the development of personal, psychological, and behavioral power to determine personal actions, goal states, and the organization’s function. This empowerment stems from sharing power and authority in organizations, nurturing the growth of subordinates, and engaging them in decision-making [5,12,13]. Iqbal and Islam [16] illustrate that servant leadership and transformational leadership substantially influence employees’ innovation and teamwork in the telecommunications sector, identifying empowerment as a robust mediator. This research enhances the area by investigating the connections among servant leadership, empowerment, creativity, and advancement.

The organization aligns with the social exchange theory (SET), which posits that granting employees autonomy, support, and responsibility may transform work dynamics and foster lasting loyalty to the company [17]. According to Gašková [15], by engaging in reciprocal relationships and offering meaningful support, servant leaders contribute to a work environment characterized by mutual respect, trust, and shared goals, resulting in enhanced EP. Another study in the telecom sector showed Trust and job satisfaction mediates the relationship between servant leadership dimensions and organizational commitment [18]. Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

There is a positive relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

2.2. Servant Leadership and Organizational Trust

SL has long been associated with fostering positive employee attitudes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment. When managers exhibit servant-leader qualities—being supportive, empowering, and ethical—employees tend to feel more satisfied and engaged in their work [19]. This aligns with Greenleaf’s [3] foundational theory that SL is a prerequisite for developing both organizational and leader trust. OT, defined as the confidence that an organization will act in the best interests of its stakeholders—including employees, customers, and shareholders—has been shown to correlate positively with employee dedication, engagement, and satisfaction [9]. Research further demonstrates that practicing SL and cultivating OT yield significant organizational benefits. Employees who perceive their leaders as genuinely caring about their well-being report higher levels of job satisfaction and, consequently, greater productivity [14]. Organizations that integrate trust-building into leadership practices are also more likely to establish collaborative and innovative work environments [20,21,22,23]. Leaders can actively nurture trust by embodying SL values such as empathy, fairness, and empowerment [20,22]. From a theoretical perspective, several frameworks illuminate the mechanisms by which SL fosters trust. SET suggests that when leaders treat employees with fairness and reciprocity, employees reciprocate with higher trust and commitment [24]. Social learning theory (SLT) also provides a lens, proposing that leaders who consistently communicate openly, model ethical conduct, and treat employees fairly become role models for trustworthy behavior [24]. Conversely, breaches of trust or inconsistent leadership practices can erode this foundation, leading to disengagement and reduced performance [23].

Recent studies have reinforced these arguments by demonstrating the reciprocal relationship between SL and OT. For instance, Almutairi et al. [25] found that servant leadership enhances trust particularly when supported by a strong organizational culture. Dami et al. [26] and Rashid & Ilkhanizadeh [27] further confirmed that trust mediates the relationship between SL and job outcomes, underscoring its pivotal role in translating leader behaviors into sustainable employee performance. Similarly, Nemati et al. [28] and Khan et al. [29] emphasized that trust is not only an outcome of servant leadership but also a crucial mechanism that sustains employee motivation and job performance.

In the telecom sector, these dynamics are particularly pronounced. For example, a study by Hamyeme et al. [30] revealed that empowerment and trust significantly influenced employees’ willingness to adopt digital transformation, showing that trust is essential for organizational adaptability in technology-driven contexts. Hassan et al. [31] also emphasized that servant behaviors promote empowerment precisely through the augmentation of trust. These findings suggest that trust is a strategic enabler of organizational change and innovation, especially in volatile industries like telecommunication. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

There is a positive relationship between servant leadership and organizational trust.

2.3. Organizational Trust and Employee Performance

OT is widely recognized as a cornerstone of effective and sustainable organizational functioning. Defined as employees’ confidence that their organization will act fairly and in their best interests [32,33], OT has been shown to positively influence EP by enhancing engagement, motivation, and collaboration [32,34]. High levels of trust reduce relational friction, strengthen communication, and create an environment where employees feel safe to take risks and contribute innovative ideas—all of which are critical for both short-term efficiency and long-term sustainability [32].

From a sustainability perspective, trust functions as a social resource that supports resilient human capital systems and contributes to organizational well-being. Organizations that foster trust are more likely to retain talent, reduce turnover, and encourage proactive citizenship behaviors [8,17,25,32]. These outcomes are directly aligned with the goals of sustainable development, particularly SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions), where inclusive and fair organizational practices form the basis of long-term competitiveness.

Theoretically, OT is well explained through SET, which posits that employees reciprocate fair and transparent treatment with loyalty, commitment, and higher performance [24]. Organizational behavior research further suggests that trust enhances team cohesion and facilitates knowledge sharing, thereby improving collective performance outcomes [33,34]. Conversely, low trust undermines collaboration, increases stress, and leads to higher absenteeism and turnover, ultimately threatening organizational sustainability [33].

Empirical studies consistently validate these associations. Rahman et al. [35] demonstrated that organizational trust significantly predicted employee commitment and performance in the mobile telecommunications sector in Egypt. Similarly, Adanma [36] found that trust was a critical determinant of employee engagement and loyalty in Nigerian telecom companies. Li et al. [34] provided evidence that mutual trust within organizations enhances both individual and group-level performance. These findings underscore the notion that trust is not only an ethical imperative but also a strategic enabler of sustainable performance across diverse contexts.

Within the telecommunications sector, where employees must navigate constant technological and market changes, trust is particularly essential. Silva et al. [32] found that trust fosters communication and teamwork, enabling employees to respond flexibly to external pressures. For telecom organizations in emerging economies such as Iraq, establishing trust is especially challenging due to institutional and cultural uncertainties, yet it is precisely this condition that makes OT indispensable for sustaining performance and innovation. Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

There is a positive relationship between organizational trust and employee performance.

2.4. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Trust

OT functions not only as an outcome of SL but also as a mechanism that explains how leadership behaviors are transformed into sustainable performance outcomes. When employees perceive their managers as genuinely caring, supportive, and committed to their development, they are more likely to trust both leaders and colleagues. This trust, in turn, enhances job satisfaction, reduces turnover intentions, and promotes discretionary effort, ultimately leading to stronger performance [37]. In this way, OT serves as a crucial mediator that strengthens the impact of SL on employee performance EP [22].

By embodying SL principles such as empathy, collaboration, and empowerment, leaders cultivate high-trust environments where employees feel safe to share ideas, engage in problem-solving, and commit to organizational goals. Such conditions not only enhance immediate performance outcomes but also embed practices that support long-term organizational sustainability [14]. Prior research confirms this mediating effect. Rashid and Ilkhanizadeh [27] found that trust significantly strengthened the relationship between SL and EP, while Zhou et al. [38] demonstrated that trust mediated the association between leadership and work engagement. Similarly, Kadarusman and Bunyamin [18] showed that trust and information sharing fully mediated the SL–EP relationship, illustrating how leadership-driven trust networks foster knowledge exchange and collaboration.

From a theoretical perspective, the mediating role of OT is grounded in SET, which posits that employees reciprocate trust-based relationships with higher levels of commitment and performance. Servant leaders, by creating trustworthy and ethical organizational climates, enable employees to feel valued and respected, which motivates them to exceed role expectations [24]. Complementary evidence also shows that SL enhances employee “voice” behaviors—voluntary contributions of ideas and feedback—when mediated by trust in leaders [29].

For industries like telecommunications, where employees must constantly adapt to technological disruption and customer demands, the mediating role of OT is particularly critical. Trust allows organizations to transform leadership practices into resilient and adaptive performance systems, thereby sustaining competitiveness in volatile environments. Importantly, positioning trust as a mediator links leadership research to the social dimension of sustainability, reinforcing the role of fair, transparent, and supportive workplace practices in achieving SDG 8 (decent work and economic growth) and SDG 16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) [7,39].

Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Organizational trust mediates the relationship between servant leadership and employee performance.

2.5. Social Exchange Theory, Social Identity Theory and Social Learning Theory

This study embraces a multi-theoretical viewpoint by integrating SET, SLT, and SIT to explain how an SL relates to OT and EP. SET states that employees will reciprocate leader support and fair treatment through engagement, commitment to the organization, and performance [24]. SLT argues that the leader’s modeled or demonstrated ethical, empowering behaviors will be learned and replicated by employees with a reinforced trust and collaboration [4,5,12]. SIT posits that when an employee identifies with the organization as an extension of self, they will be engaged and motivated in their role [13,32]. Thus, SET, SLT, and SIT collaborate to explain trust-building behaviors concurrently across interpersonal, organizational, and identity levels [6,7,9,18,29] with SL achieving sustainable performance outcomes. Lastly, this multi-theoretical perspective furthers the visibility of SL as not just a leadership style, but as a process for values of trust, collaboration and inclusion to be built into organizational systems in order to help with sustainable organizational performance and socially responsible management [10,11,39].

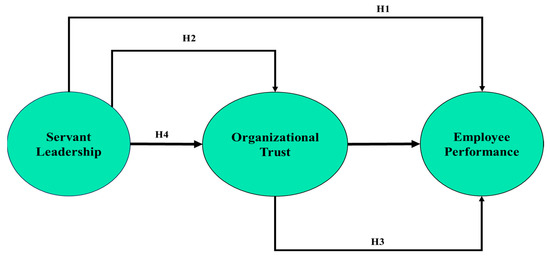

Considering the above discussion, the study variable of the research model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample

This study adopted a cross-sectional survey design targeting employees of three major Iraqi telecommunications companies: Korek Telecom, Asia Cell, and Delta Communication. The study is quantitative and deductive in nature. A convenience sampling technique was employed, given its suitability for reaching a diverse workforce under conditions of limited accessibility and security constraints. In addition, to reduce the pitfalls of a non-probability approach, the study employed a relatively large sample size, high response rate, and representation of diverse employee groups (managers, supervisors, and frontline employees) from Iraq telecommunications, which support the trustworthiness and longevity of the findings [6,40]. Questionnaires were distributed electronically to department managers, supervisors, and frontline employees, enabling the researchers to efficiently gather critical insights without the logistical burdens associated with probability-based sampling. It should be noted that using non-probability sampling may introduce potential bias in the results.

The total population across the three companies was approximately 4000 employees. Following sample size recommendations for survey research [41], a target of 400 responses was set to ensure sufficient statistical power. Of these, 375 valid responses were obtained, yielding a high response rate of 93.75%, which strengthens the reliability of the findings and minimizes non-response bias.

3.2. Data Collection

Data were collected through a standardized questionnaire. The survey link was shared via company Human Resource (HR) departments through employee email addresses. Participation was voluntary for each employee, and participants were ensured confidentiality and anonymity. Respondents were not offered any financial or material incentives. Prior to the start of the survey, the purpose of the study was explained to the potential participants. Responses were collected through Google Forms which helped minimize administrative errors and increased efficiency. Ethical Considerations: This study adhered to ethical research practices that were consistent with international ethical standards, principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and formally obtained permission from the participating companies HR department(s). Informed consent was obtained electronically prior to data collection, and responses were kept confidential.

3.3. Measures

The questionnaire consisted of four parts: demographic information, the Organizational Trust Scale, the Servant Leadership Scale, and the Employee Performance Scale. This study assessed SL utilizing the measurement scale from Liden et al. [4], comprising twenty-eight items with a Cronbach alpha of (0.978). Respondents evaluate SL on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly dissatisfied) to 5 (strongly satisfied). This study measured EP using from Yousef [42], scale, which includes four items with a Cronbach alpha of (0.917). This study asked respondents to rate their performance on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very low) to 5 (very high). This study measured OT using the 9-item scale developed by Schoorman et al. [43]. Respondents evaluate OT on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). The Cronbach alpha for the 9 items of OT was (0.917). Table 1 summarizes the Cronbach’s alpha for the study variables.

Table 1.

Cronbach alpha results.

3.4. Data Analysis Technique

The data were analyzed using SPSS v26.0 and PROCESS Macro to examine direct and mediated relations [44]. The authors performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to test the measurement model. Harman’s single-factor test indicates there is no common method bias. For multicollinearity testing all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) scores were below 2, indicating there was no serious multicollinearity. Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS version 25. Data was analyzed using exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to look at the correlation between variables. The study conducted a correlational analysis to evidence a relationship between the variables. The authors also utilized the PROCESS macro for SPSS version 4.2 to analyze the study hypotheses [45].

3.5. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Eight demographic characteristics of the respondents have been established in this study: their organization of employment, gender, age, marital status, education level, position, total work experience, and years of work experience at their present organization. Table 2 shows the demographic qualities of the respondents. The findings indicated that 36% noted Asiacell Telecom as their organization name, 52.4% were male, 33.1% were in the 35 to 40-year-old age group, 64% were married, 72% had received an undergraduate degree, 87.7% worked in the position of employee, 32.3% had work experience between the 5 to 10 range, and 38.1% had worked at the same present organization for 1 to 4 years.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the respondents.

4. Results

4.1. Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to reduce the observed variables into a more parsimonious set of factors and to examine the underlying structure of the constructs [46]. Principal component analysis (PCA) with Promax rotation and Kaiser normalization was applied, in line with established methodological recommendations for robust construct validation [45]. To ensure clarity and reliability, only items with factor loadings above 0.40 on a single construct were retained. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic was 0.967, which indicates excellent sampling adequacy, while Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at p < 0.05, confirming that the dataset was suitable for factor analysis [41]. The EFA results revealed three distinct factors that together explained 66.24% of the total variance. SL emerged as the dominant construct with twenty-eight items loading between 0.550 and 0.936, accounting for 51.67% of the variance. OT was represented by seven items with loadings ranging from 0.558 to 0.900, explaining 9.46% of the variance. Finally, EP was measured through four items with loadings between 0.816 and 0.945, contributing 5.11% of the variance. These results demonstrate that the three constructs are statistically distinct yet conceptually interrelated, which supports their use in subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Establishing such strong construct validity at this stage provides a solid foundation for hypothesis testing and enhances the credibility and sustainability of the study’s findings within organizational and leadership research. Moreover, multicollinearity was evaluated using the variance inflation factor (VIF). Estimated VIF values were 2.10 for SL, 2.51 for OT, and 1.53 for EP, all below the commonly recommended threshold of 5, indicating no serious multicollinearity among constructs [47]. The detailed results of the exploratory factor analysis are presented in Table 3, which illustrates the factor loadings, eigenvalues, and explained variance for each construct.

Table 3.

Exploratory factor analysis result.

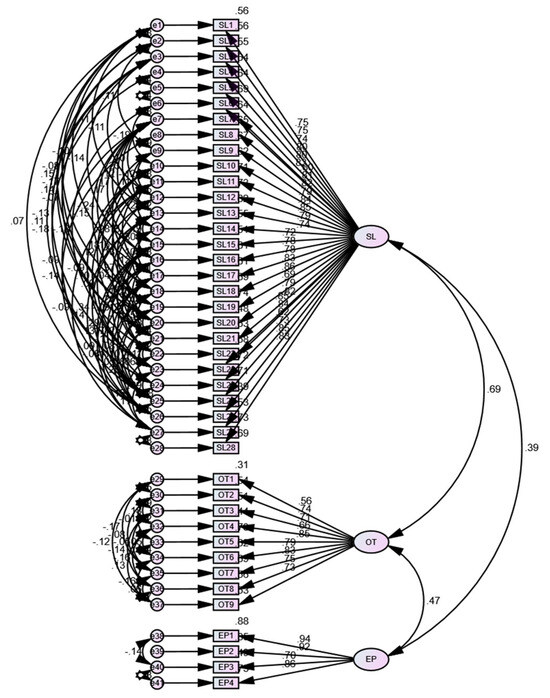

4.2. Confirmatory Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to validate the measurement model and ensure that each construct was represented by a unidimensional set of indicators. Using AMOS version 24, the analysis assessed convergent validity through standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR). Following the recommendations of Awang [48] and Hair et al. [47], convergent validity is established when factor loadings are substantial, AVE values exceed 0.50, and CR values are greater than 0.60. The results indicated that all constructs in this study satisfied these criteria, thereby confirming their reliability and validity. As shown in Figure 2, the CFA model demonstrates the relationships between the latent variables (SL), (OT), and (EP)—and their observed indicators. The figure highlights the strong standardized loadings of items on their respective constructs, visually supporting the robustness of the measurement model.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

The detailed results of the CFA are summarized in Table 4. SL was measured through 28 items with loadings ranging from 0.623 to 0.859, yielding a CR of 0.979 and an AVE of 0.63. OT was assessed using 9 items with loadings between 0.557 and 0.854, producing a CR of 0.914 and an AVE of 0.55. EP was captured with 4 items that loaded between 0.698 nand 0.940, with a CR of 0.917 and an AVE of 0.74. These values collectively demonstrate high internal consistency and strong convergent validity across the three constructs. In addition to convergent validity, model fit was examined using multiple indices.

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis result.

As reported in Table 5, the values for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), and Incremental Fit Index (IFI) were 0.942, 0.902, and 0.943, respectively, all of which approximate or exceed the 0.90 benchmark recommended by Bentler and Bonett [49], Byrne [50], and Hu and Bentler [51]. Furthermore, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.051 and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.058, both within the acceptable limits established by Browne and Cudeck [52] and Hu and Bentler [51]. The chi-square value (CMIN = 1051.451, df = 666, p < 0.001) and the relative chi-square (CMIN/DF = 2.254) also fall within acceptable ranges, providing additional evidence of model adequacy. Taken together, these findings confirm that the CFA model demonstrates a satisfactory fit with the observed data. The strong psychometric properties of the scales not only ensure the credibility of the present analysis but also enhance the replicability and sustainability of future research in servant leadership, organizational trust, and employee performance.

Table 5.

Fit indicators for the CFA model.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Moreover, the authors performed a discriminant validity test to assess construct validity. Fornell and Larcker [53] established that statistical methods evaluate discriminant validity by ascertaining whether the relational dynamics of the two constructs is statistically significantly less than one. The Fornell–Larcker criterion is among the most often utilized methods to assess measurement models’ discriminant validity. Per this criterion, the square root of the average variance extracted by a construct has to be higher than the correlation between that construct and any other [53,54,55,56]. Table 6 summarizes the discriminant validity test.

Table 6.

Discriminant validity test.

4.4. Hypothesis Testing

To analyze the study hypotheses authors used process- macro on SPSS V 4.2. Table 7 summarizes every aspect of the hypotheses. Table 7 summarizes every aspect of the hypotheses. This study’s findings show that the hypotheses achieved statistically significant results according to the criteria outlined by Preacher and Hayes [55].

Table 7.

Result of hypothesis testing.

Additional details and supporting information are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of SL on employee performance in Iraqi telecommunications companies, with OT as a mediating variable. The findings revealed both direct and indirect effects, although the magnitude of these effects was weaker than anticipated. These results offer important insights into the complex dynamics between leadership, trust, and performance in volatile and competitive contexts.

The first result demonstrated a weak positive association between SL and EP (R2 = 0.135). This finding suggests that while SL contributes to performance outcomes, its influence is limited unless reinforced by complementary factors such as job satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, or team cohesion. This aligns with previous studies that highlight the enabling role of SL in creating supportive environments rather than directly driving outcomes [4,14]. Walumbwa et al. [9] and Miao et al. [57] similarly found that SL impacts performance indirectly by shaping climates of fairness and collaboration. The current findings therefore underscore that leadership styles alone may be insufficient to sustain performance; rather, they must be integrated with organizational practices that recognize employees, provide fair compensation, and encourage innovation to achieve sustainable outcomes. The implication of the results from a sustainability perspective is that SL can advance the eighth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 8) related to decent work and economic growth by creating an environment conducive to increasing productivity and well-being, but requires the backdrop of fair labor policies and inclusive human resource practices [2]. The second result indicated a weak but significant relationship between SL and OT (R2 = 0.390). Although servant leaders are theoretically expected to inspire trust through ethical and supportive behaviors [3,5,6], in this context, the impact was limited. This may reflect cultural and institutional challenges in Iraq, where employees often face uncertainty and perceive leadership systems as inconsistent. Prior studies confirm that weak trust environments are associated with disengagement, defensive behaviors, and reduced creativity [7,8]. The present study extends these findings by highlighting that without credibility, transparency, and consistency in leader behavior, SL may not fully translate into trust-building. This echoes Eva et al. [5] who argued that contextual conditions often moderate the effectiveness of servant leadership. These findings also align with SDG 16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), emphasizing that trust is not only an interpersonal value but also an institutional requirement for building resilient and transparent organizations [1]. Third, the relationship between OT and EP was also weak (R2 = 0.212), indicating that insufficient trust undermines employees’ willingness to fully engage with organizational objectives. This is consistent with prior evidence that trust is essential for collaboration, innovation, and long-term performance [32,33,34]. When trust is fragile, employees may limit their contributions to the minimum required, thereby weakening organizational resilience. Comparable findings in Egypt and Nigeria also demonstrated that OT significantly influences performance through commitment mechanisms [35,36]. From the viewpoint of sustainability, the findings show that trust is both an interpersonal virtue and a strategic resource for achieving decent work, decreasing turnover, remaining competitive in the long run (SDG 8), and institutionalizing sustainable practices in organizations [11].

Fourth, the mediating role of OT between SL and EP (R2 = 0.2226) was confirmed but relatively weak. This indicates that while servant leaders can foster trust and, in turn, performance, fragile trust environments dilute these effects. Previous studies, such as Rashid and Ilkhanizadeh [27] and Kadarusman and Bunyamin [18], reported stronger mediating effects, suggesting that cultural or organizational barriers may explain the weaker mediation found here. SET offers an explanation: when reciprocity norms are not consistently honored by organizations, employees may be reluctant to reciprocate trust, thereby weakening the expected SL–EP linkage [24]. These findings highlight that for servant leadership to yield sustainable benefits, organizations must institutionalize transparent communication, equitable treatment, and accountability mechanisms. This informs the wider necessity of embedding sustainability into institutional infrastructures, while Manioudis & Meramveliotakis [1] claim that sustainable development should not simply be thought of as an afterthought but an embedded part of the organizational structure itself. Finally, this study contributes by proposing a leadership development framework that emphasizes trust, self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and ethical decision-making as foundations for cultivating sustainable leadership. By embedding these principles into training programs, organizations can prepare future leaders to adopt SL behaviors that empower employees, promote collaboration, and strengthen organizational adaptability. Such an approach aligns with broader sustainability objectives by supporting human capital development, fostering inclusive workplaces, and embedding long-term ethical values in leadership practices [10,11]. In this respect, SL and OT together can be seen as catalysts for developing sustainable organizational cultures that directly support SDG 8 (Decent Work), SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), and SDG 16 (Strong Institutions). Leadership education is thereby seen, when framed in service not authority, as a mechanism to alter organizational practices toward sustainability for the long term [2,11].

6. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This study draws upon SET, SLT, and social identity theory to explain how SL affects employee performance, with organizational trust serving as a mediating mechanism in the telecommunications sector. The findings provide empirical support for the argument that trust functions as a central channel through which SL exerts its influence. While the results indicated only a weak direct relationship between SL and EP, they confirm that SL indirectly shapes performance by fostering environments where trust, fairness, and reciprocity are valued [58,59]. The study contributes to theory in several ways. First, it highlights that servant leadership alone may not strongly predict performance unless accompanied by cultural and structural enablers, echoing calls in prior research for contextualized models of SL effectiveness [5,25]. Second, it extends Greenleaf’s [3] foundational theory by providing evidence from Iraq, an underrepresented emerging economy where institutional uncertainty and cultural norms shape trust dynamics differently from Western contexts. This addresses a notable gap in the literature, as most prior studies have focused on Western or East Asian economies [57]. Third, by integrating SET, SLT, and SIT, the study offers a multi-theoretical perspective showing that trust-building behaviors operate simultaneously at the interpersonal, organizational, and identity levels. Finally, the study advances the discourse on sustainable leadership by framing SL not only as a leadership style but also as a mechanism for embedding values of trust, collaboration, and inclusion into organizational systems. This strengthens theoretical links between SL and sustainable organizational performance, aligning with the broader literature on socially responsible management [10,11].

6.2. Practical Implications

From a practical perspective, the findings indicate that organizations aiming to improve performance should move beyond leadership rhetoric and actively embed servant leadership principles into daily operations. In dynamic sectors such as telecommunications, this involves institutionalizing trust through transparent communication, ethical behavior, and consistent decision-making, which are crucial for reducing uncertainty and increasing employee engagement. Leadership development programs should focus on building key servant leadership competencies—such as empathy, empowerment, and fairness—using practical methods like role-playing, case studies, and coaching to help leaders model these behaviors effectively. Furthermore, linking leadership practices to sustainability objectives by integrating trust-based management into human resource policies can support decent work, reduce turnover, and enhance employee well-being, aligning with SDG 8. Promoting employee voice and participation through empowerment initiatives further strengthens trust and improves organizational adaptability in technology-driven environments [27]. Overall, the results suggest that servant leadership not only boosts immediate employee performance but also fosters a resilient organizational culture. By cultivating trust, collaboration, and empowerment, companies can enhance both short-term results and long-term sustainability, preparing them to withstand market and environmental challenges [27].

6.3. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the findings are industry-specific and may not generalize to other sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, or education. Future research should replicate the model across different industries and cultural contexts to improve external validity. Second, the study relied on cross-sectional data, which restricts the ability to establish causality. Longitudinal research designs would provide deeper insights into how trust evolves over time and mediates leadership–performance relationships. Third, reliance on self-reported data raises the risk of common method bias, despite statistical checks. Triangulating data sources (e.g., supervisor ratings or objective performance metrics) would strengthen future studies. Finally, this research focused exclusively on OT as a mediator, whereas other factors such as job satisfaction, employee motivation, and organizational culture may also explain the SL–EP relationship. Examining multiple mediators and moderators could yield a more nuanced understanding of these dynamics.

7. Conclusions

This research explored the effect of SL on employee performance in the telecommunications industry, with organizational trust tested as a mediating variable. The findings were substantiated by social exchange theory, social identity theory, and social learning theory, and revealed a statistically significant positive relationship between SL and EP, while also exposing a mediating relationship with OT that strengthens that relationship. Although the relationships were weaker than I had expected, the study highlights that trust can remain a core mechanism by which leadership practices are translated into sustainable employee outcomes. In that sense, organizational trust can be perceived not only as a precursor for performance, but also as a pathway for embedding sustainability into institutional processes.

The study underscores that telecom companies can gain substantial benefits by embedding servant leadership principles into their organizational culture. By prioritizing employee well-being, empowerment, and fairness, servant leaders cultivate higher motivation and engagement, which in turn improve service quality and customer satisfaction. Moreover, the emphasis on organizational trust is particularly critical in the telecommunications industry, where rapid technological changes and competitive pressures demand adaptability, collaboration, and resilience. In such contexts, SL provides an effective leadership approach that not only enhances short-term performance but also embeds long-term values of transparency, inclusion, accountability, and sustainable organizational practices [11]. In this way, SL and OT both provide immediate competitiveness and also broader sustainability development aspects of leadership. Practically, the findings suggest that telecom providers should integrate SL-based training into their leadership development initiatives, ensuring that managers are equipped with the skills to foster trust-centric and sustainably oriented cultures. Initiatives such as transparent communication, regular feedback, and participatory decision-making are essential for building credibility and improving morale. Empowering employees with greater decision-making authority can further accelerate problem-solving, enhance job satisfaction, and create a sense of ownership that strengthens both individual and organizational performance. By implementing these practices, organizations are not only improving organizational efficiency but also are contributing to inclusive and sustainable growth as part of the global sustainability agenda. Ultimately, the study contributes to the broader sustainability discourse by showing that servant leadership, when combined with organizational trust, represents not only a management philosophy but also a pathway toward building resilient organizations capable of achieving sustainable competitive advantage. In addition to improving organizational performance, the findings reveal that adopting SL can enhance social responsibility, increase equity, and strengthen long-term institutional resilience. Finally, the outcomes of this study are connected to the Sustainable Development Goals by demonstrating that servant leadership and organizational trust can enable sustainable employee performance and apply to SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth and SDG 16: Strong Institutions. Moreover, while also increasing transparency and inclusion and empowerment, SL and OT contribute to both SDG 5: Gender Equality and SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities and SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production, emphasizing their importance for sustainable organizational development as strategic levers [1,2,11].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17198958/s1.

Author Contributions

The duties of writing the original draft and manuscript preparation were carried out by T.K. alongside S.Z.E., T.K. and S.Z.E. were responsible for developing the overall methodology. T.K. handled the data collection and T.K. and L.T. were in charge of the data analysis. The roles of writing the review and editing were passed to T.K., S.Z.E., and L.T. Supervision was under S.Z.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Near East University (NEU/SS/2022/1223).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work is based on the first author’s doctoral dissertation, “The Influence of Servant Leadership on Employee Performance: Building a Strong Organizational Trust, Identity, and Corporate Loyalty”. The planned submission date is June 2025. The dissertation supervisor is the second author of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Manioudis, M.; Meramveliotakis, G. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Econ. 2022, 27, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarin, T. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018, 21, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenleaf, R.K. Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness; Paulist Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Zhao, H.; Henderson, D. Servant leadership: Development of a multidimensional measure and multi-level assessment. Leadersh. Q. 2008, 19, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva, N.; Robin, M.; Sendjaya, S.; van Dierendonck, D.; Liden, R.C. Servant Leadership: A Systematic Review and Call for Future Research. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namiq, H.R.; Mustafa, H.A. The Mediating Role of Organizational Trust in the Relationship Between Effective Leadership and Organizational Reputation: Evidence from Telecom Companies in Sulaimani City. Koya Univ. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 8, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Paine, J.B.; Bachrach, D.G. Organizational citizenship behaviors: A critical review of the theoretical and empirical literature and suggestions for future research. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 513–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Hartnell, C.A.; Oke, A. Servant leadership, procedural justice climate, service climate, employee attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-level investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.C.; Tan, K.C.; Zailani, S.H.M. Strategic orientations, sustainable supply chain initiatives, and reverse logistics: Empirical evidence from an emerging market. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 171, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.Z.; Yang, Q.; Waheed, A. Investment in intangible resources and capabilities spurs sustainable competitive advantage and firm performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reslan, F.Y.B.; Garanti, Z.; Emeagwali, O.L. The Effect of Servant Leadership on Innovative Work Behavior and Knowledge Sharing in the Latvian ICT Sector. Balt. J. Manag. 2021, 16, 729–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.A. Servant Leadership and Follower Outcomes: Mediating Effects of Organizational Identification and Psychological Safety. J. Psychol. 2016, 150, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, G.; Cavaliere, L.P.L.; Ammar, K.; Afzal, F.U. The Impact of Servant Leadership on Employee Performance. Int. J. Manag. 2021, 12, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Gašková, J. Servant Leadership and Its Relation to Work Performance. Cent. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2000, 9, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Islam, A. The Empowerment Bridge: Assessing the Role of Employee Empowerment in Transmitting the Impact of Servant and Transformational Leadership on Creativity and Team Innovation. J. Bus. Manag. Res. 2023, preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Alarabiat, Y.A.; Eyupoglu, S. Is Silence Golden? The Influence of Employee Silence on the Transactional Leadership and Job Satisfaction Relationship. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadarusman, K.; Bunyamin, B. The Role of Knowledge Sharing and Trust as Mediators on Servant Leadership and Job Performance. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coun, M.J.H.; De Ruiter, M.; Peters, P. At Your Service: Supportiveness of Servant Leadership, Communication Frequency and Channel Fostering Job Satisfaction across Generations. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1183203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, Y. The Impact of Servant Leadership and Employee Commitment in Ghana’s Technical Universities. ADRRI J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2022, 19, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Setyaningrum, R.P.; Setiawan, M.; Irawanto, D.W. Servant Leadership Characteristics, Organisational Commitment, Followers’ Trust, Employees’ Performance Outcomes: A Literature Review. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2020, XXIII, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Batool, N.; Hassan, S. The Influence of Servant Leadership on Loyalty and Discretionary Behavior of Employees: Evidence from Healthcare Sector. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2019, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Althnayan, S.; Alarifi, A.; Bajaba, S.; Alsabban, A. Linking Environmental Transformational Leadership, Environmental OCB, and Organizational Sustainability Performance: A Moderated Mediation Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyle-Shapiro, J.A.M.; Diehl, M.-R. Social Exchange Theory: Where Is Trust? In The Routledge Companion to Trust; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, B.A.; Alraggad, M.A.A.; Khasawneh, M. The impact of servant leadership on organizational trust: The mediating role of organizational culture. Eur. Sci. J. June 2020, 16, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dami, Z.A.; Salleh, L.M.; Mustapha, M. Servant leadership’s values and staff’s commitment in Nigerian higher education. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2018, 19, 793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, A.; Ilkhanizadeh, S. Servant leadership and job outcomes: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2022, 30, 1417–1435. [Google Scholar]

- Nemati, A.R.; Nemati, S.A.; Firdous, R. Impact of servant leadership on employee performance, with mediating effect of trust and moderating effect of culture: Evidence from the banking sector of Pakistan. Mark. Forces 2022, 17, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.; Jianguo, D.; Golroudbary, S.R.; Chofreh, A.G. Servant leadership and performance of public hospitals: Trust in the leader and psychological empowerment of nurses. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamyeme, S.; Belagra, F.; Bouzidi, F. Effect of Implementing Servant Leadership Practices on the Adoption of Digital Transformation for Telecoms. Bus. Ethics Leadersh. 2024, 8, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, N.; Yoon, J.; Dedahanov, A.T. Servant Leadership Style and Employee Voice: Mediation via Trust in Leaders. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertürk, A. Exploring Predictors of Organizational Identification: Moderating Role of Trust. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2010, 19, 409–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, Y.; Basana, S.R.; Panjaitan, T.W.S. The Effect of Organizational Trust and OCB on Employee Performance. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 76, 01058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yan, J.; Jin, M. How Does Organizational Trust Benefit Work Performance? Front. Bus. Res. China 2007, 1, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.A.; Wahba, M.; Ragheb, M.A.S.; Ragab, A.A. Effect of Organizational Trust on Employee Performance through Organizational Commitment (Mobile Phone Companies in Egypt). OALib 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanma, J. Organizational Trust and Employee Commitment of Telecommunication Companies in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Am. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 4, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Gopinath, C.; Adeel, A. Impact of Servant Leadership on Performance: Mediating Role of Trust. Sage Open 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Gul, R.; Tufail, M. Does Servant Leadership Stimulate Work Engagement? The Moderating Role of Trust in the Leader. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 925732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. More Than Just Convenient: The Scientific Merits of Homogeneous Convenience Samples. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2017, 82, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, M.M.A.; Ting, H.; Cheah, J.-H.; Thurasamy, R.; Chuah, F.; Cham, T.H. Sample Size for Survey Research: Review and Recommendations. J. Appl. Struct. Equ. Model. 2020, 4, i–xx. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, D.A. Organizational Commitment: A Mediator of the Relationships of Leadership Behavior with Job Satisfaction and Performance in a Non-Western Country. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoorman, F.D.; Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H. An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust: Past, Present, and Future. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. An Index and Test of Linear Moderated Mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Brief Tutorial on the Development of Measures for Use in Survey Questionnaires. Organ. Res. Methods 1998, 1, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Awang, Z. SEM: Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS Graphic; Universiti Teknologi MARA Publication Centre (UPENA): Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R. Alternative Ways of Assessing Model Fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 1992, 21, 230–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based SEM. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and Resampling Strategies for Assessing and Comparing Indirect Effects in Multiple Mediator Models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dami, Z.A.; Imron, A.; Burhanuddin; Supriyanto, A. Servant Leadership and Organizational Citizenship Behavior in Indonesian Christian Higher Education: Direct and Indirect Effects. J. Res. Christ. Educ. 2024, 33, 58–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Newman, A.; Schwarz, G.; Xu, L. Servant Leadership, Trust, and Organizational Commitment of Public-Sector Employees in China. Public Adm. 2014, 92, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liden, R.C.; Wayne, S.J.; Liao, C.; Meuser, J.D. Servant Leadership and Serving Culture: Influence on Individual and Unit Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 1434–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.P.; Odom, S.F. Mindsets of Leadership Education Undergraduates: An Approach to Program Assessment. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2015, 14, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).