Electronics Shops in Saint-Louis: A Participative Mapping of Value, Quality, and Prices Within the Market Hierarchy in a Secondary Senegalese City

Abstract

1. Introduction

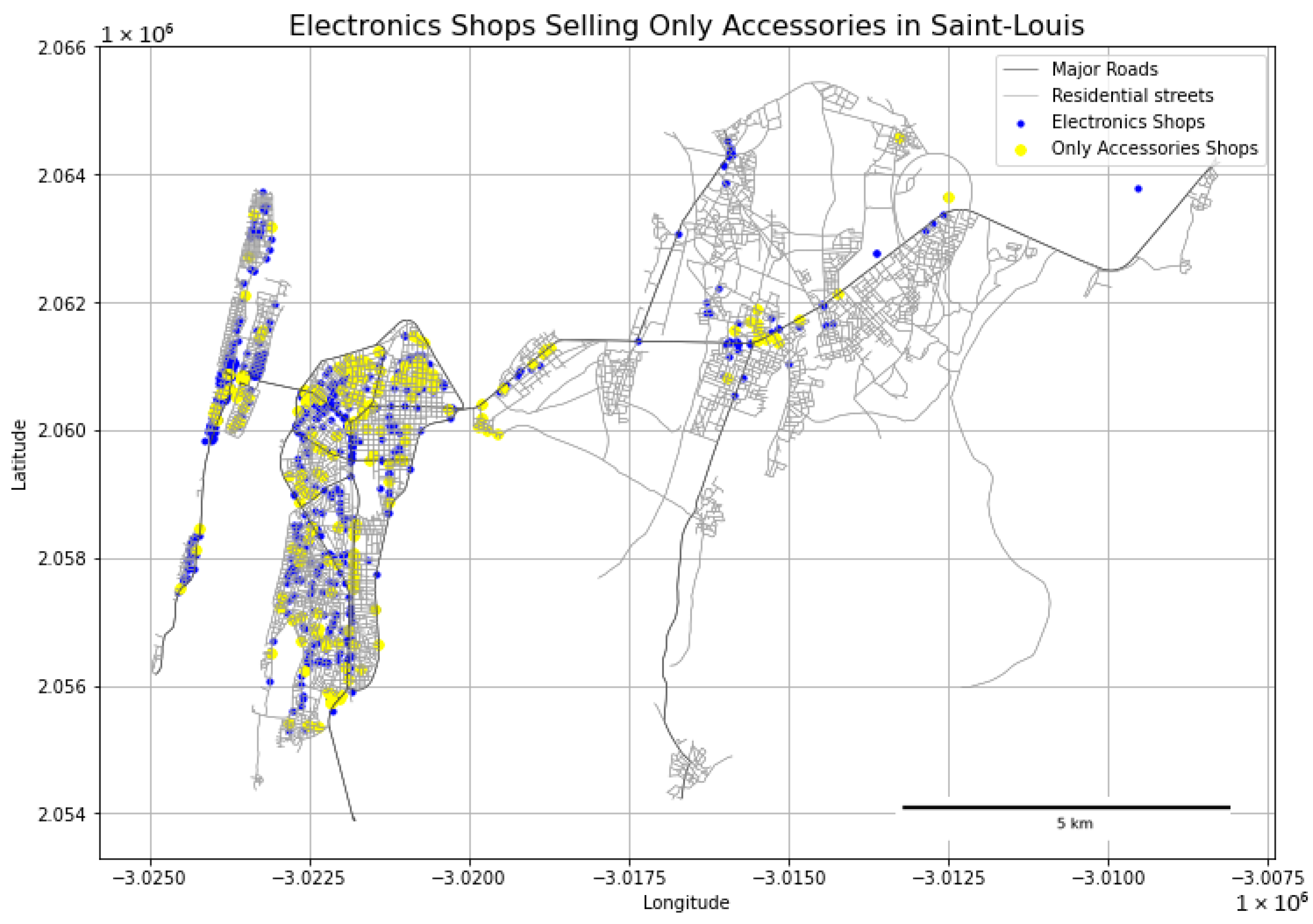

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Description

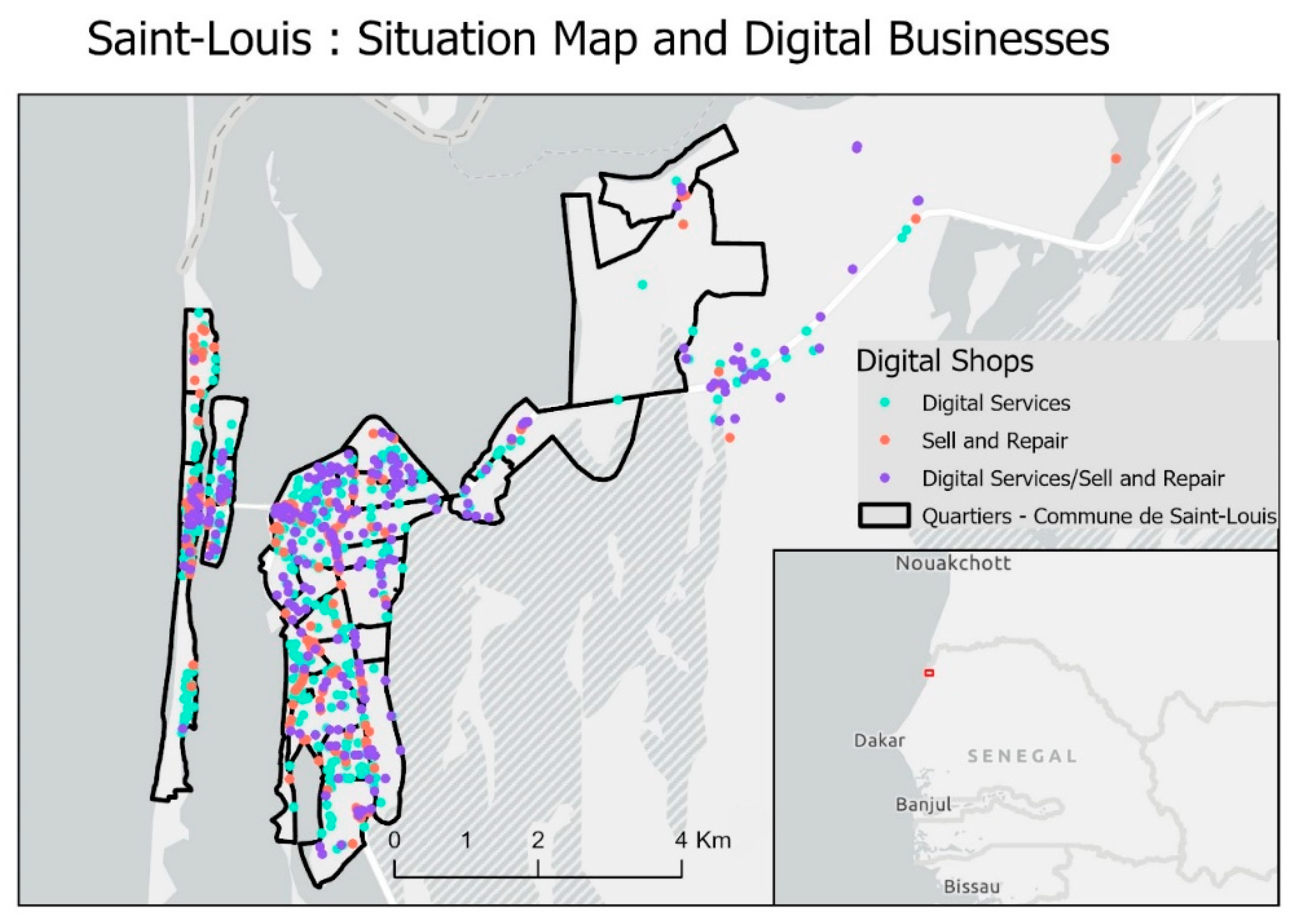

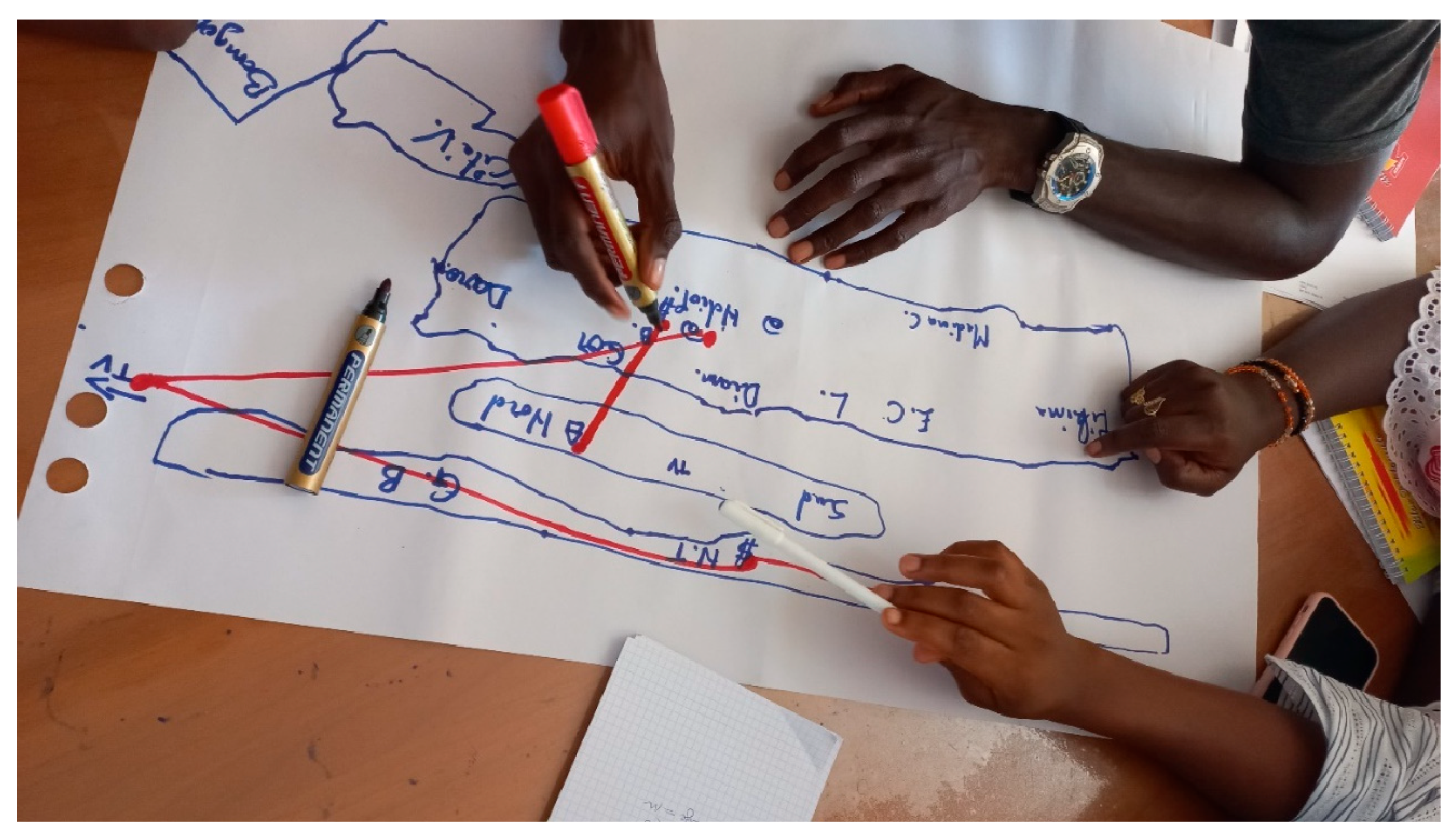

2.2. Data Collection with PGIS and Territorial Sampling Method

3. Results

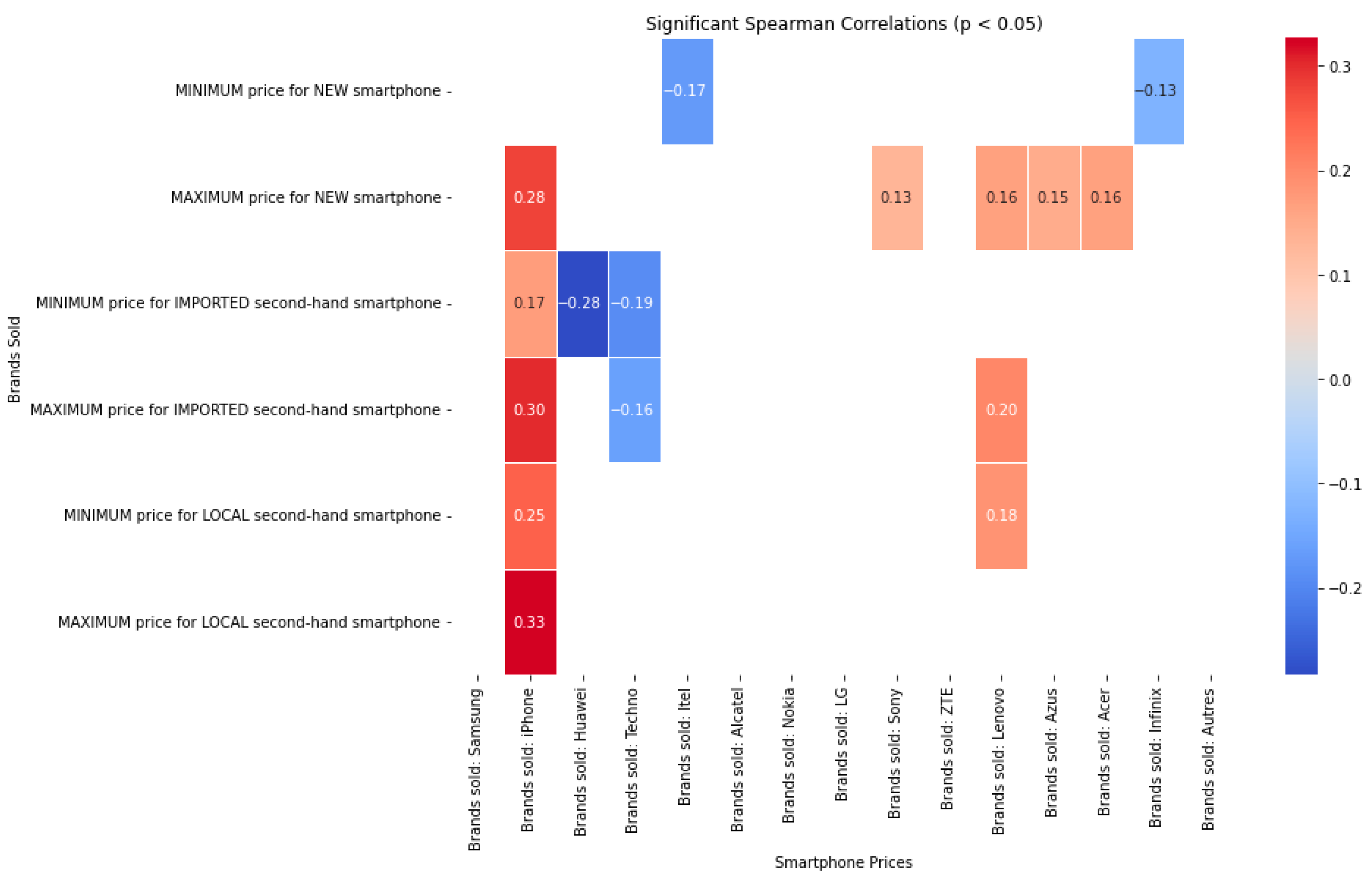

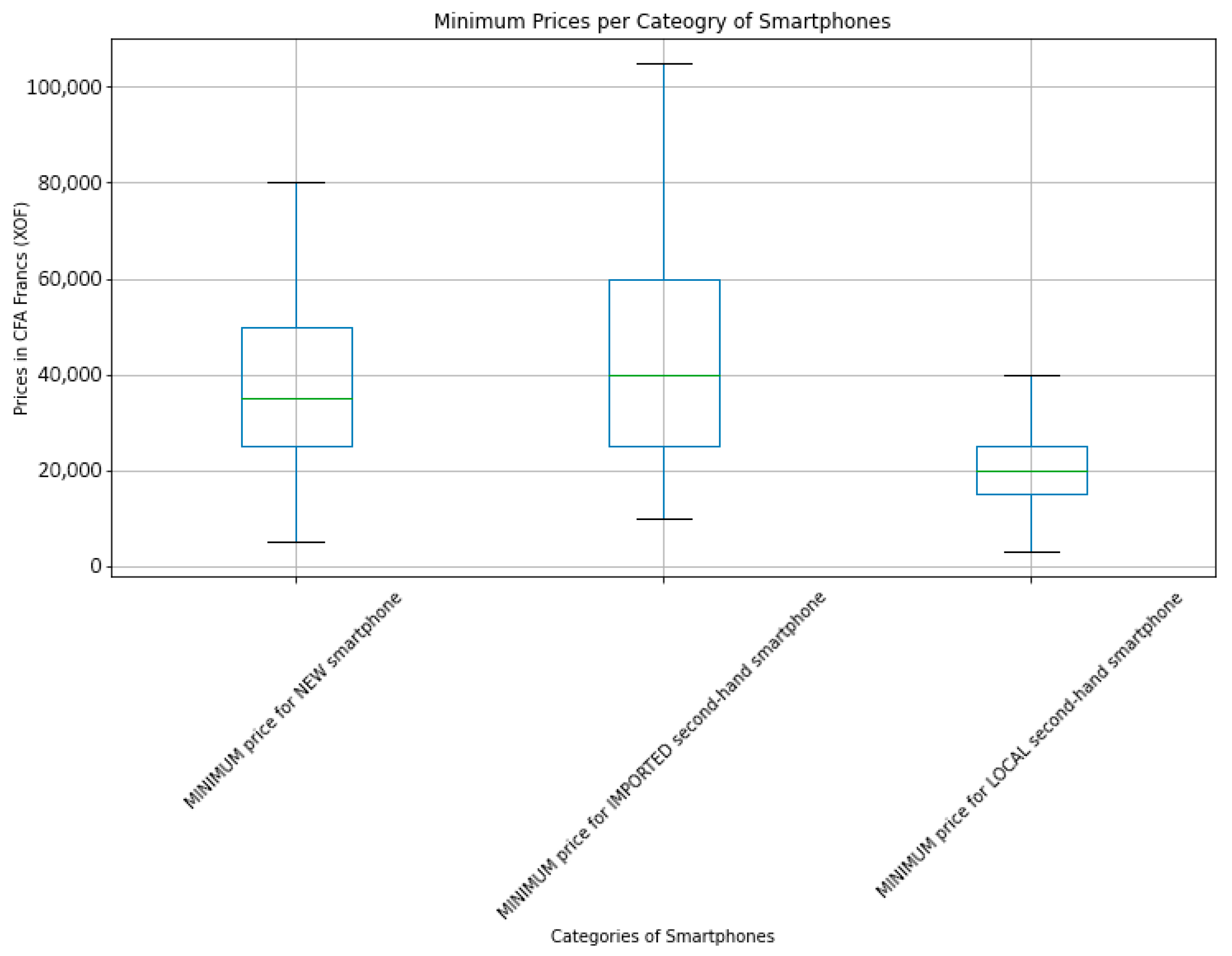

3.1. The Products Sold in Saint-Louis

3.2. Hierarchy of Markets in the City

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lepawsky, J. The Changing Geography of Global Trade in Electronic Discards: Time to Rethink the e-Waste Problem. Geogr. J. 2015, 181, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepawsky, J. Reassembling Rubbish: Worlding Electronic Waste; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-262-53533-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lubick, N. Shifting Mountains of Electronic Waste. Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 148–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Setyadi, A.; Pawirosumarto, S.; Damaris, A. Embedding Circular Operations in Manufacturing: A Conceptual Model for Operational Sustainability and Resource Efficiency. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M. The Shared Space: The Two Circuits of the Urban Economy in Underdeveloped Countries; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-10310-5. [Google Scholar]

- Adjanohoun, D.S.; Mbengue, T.P.; Sow, D.; Wade, C.S.; Seye, M.R.; Mbaye, D.; Diallo, M.; Ndiaye, M.L.; De Roulet, P.; Munyaka, J.C.B.; et al. The Digital Policies in the Face of Access and Usage Inequalities among Young People in Intermediate Cities in Senegal: The Case of Saint-Louis. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2025, 9, 10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seye, M.R.; Mbaye, D.; Diallo, M.; Ndiaye, M.L.; Sow, D.; Adjanohoun, D.S.; Mbengue, T.; Wade, C.S.; Pablo, D.R.; Munyaka, J.-C.B.; et al. A Crowdsourcing-Based Walk Test Approach to Evaluate Mobile Network Quality. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 11–14 January 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sow, D.; Adjanohoun, D.; Mbengue, T.; Wade, C.S.; Seye, M.R.; Mbaye, D.; Ndiaye, M.; Diallo, M.; De Roulet, P.; Munyagua, J.C.; et al. Jeunes et fractures numériques à Saint-Louis (Sénégal): Entre inégalités territoriales, vulnérabilités sociales et dynamiques d’adaptation. Rev. Ivoirienne Géographie Savanes 2025, 18, 677–690. [Google Scholar]

- Jakobi, Á. Space and Virtuality: New Characteristics of Inequalities in the Information Society and Economy. Rev. Appl. Socio-Econ. Res. 2013, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello, F. From Industrial to Digital Citizenship: Rethinking Social Rights in Cyberspace. Theory Soc. 2023, 52, 463–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. The Digital Reproduction of Inequality. In The Inequality Reader; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 660–670. [Google Scholar]

- Mwaura, J.; Carter, V.; Kubheka, B.Z. Social Media Health Promotion in South Africa: Opportunities and Challenges. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2020, 12, a2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoka, C. Digital Media, Popular Culture and Social Activism amongst Urban Youth in Nigeria. Crit. Afr. Stud. 2023, 15, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, E.F.; Esson, J.; Gough, K.V. Geographies of Youth, Mobile Phones, and the Urban Hustle. Geogr. J. 2020, 186, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSD. SES Régionales. Available online: https://www.ansd.sn/ses-regionales (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Gueye Aïda, N. Contribution à l’étude de La Foresterie Urbaine Dans La Commune de Saint-Louis, Sénégal. Rev. Ecosystèmes Paysages 2024, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, C. La Région de Saint-Louis Du Sénégal: Patrimoine, Tourisme et Développement. Ph.D. Thesis, Research Center in International and Atlantic History, Nantes, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Faye, D. Urbanisation et Dynamique Des Transports “Informels” et Des Mobilités Dans Les Villes Secondaires Sénégalaises: Les Cas de Touba, Thiès et Saint Louis. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Michel de Montaigne-Bordeaux III, Pessac, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, J.; McEwan, C.; Petrella, L.; Baguian, H. Climate Change, Urban Vulnerability and Development in Saint-Louis and Bobo-Dioulasso: Learning from across Two West African Cities. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grydehøj, A. Guest Editorial Introduction: Understanding Island Cities. Isl. Stud. J. 2014, 9, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Zhang, G.; Lin, T.; Hamm, N.A.S.; Li, C.; Wu, X.; Hu, K. Quantitative Evaluation of Spatial Accessibility of Various Urban Medical Services Based on Big Data of Outpatient Appointments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diop, C. Water and Sanitation in the Neighborhood of Guet Ndar-Senegal Cheikh DIOP. Int. J. Eng. Work. 2017, 4, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, C.; Davies, J.; Green, R.; Zimmer, A.; Anderson, P.; Battersby, J.; Baylis, K.; Joshi, N.; Evans, T.P. Persistence of Open-Air Markets in the Food Systems of Africa’s Secondary Cities. Cities 2022, 124, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouma, M. Commerce et gestion de l’espace urbain à Dakar: Enjeux, logiques et stratégies des acteurs. Ph.D. Thesis, Normandie Université, Caen, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zickgraf, C. Relational (Im)Mobilities: A Case Study of Senegalese Coastal Fishing Populations. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 3450–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayson, D. Community Mapping and Data Gathering for City Planning in the Philippines. Environ. Urban. 2018, 30, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roulet, P.; Chenal, J.; Munyaka, J.-C.B.; Pudasaini, U. Mapping Rural Mobility in the Global South: Case Studies of Participatory GIS Approach for Assessments of Daily Movement Needs and Practice in Nepal and Kenya. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.P.; Pessoa Colombo, V.; Heider, K.; Rodriguez-Lopez, J.M. Comparing Volunteered Data Acquisition Methods on Informal Settlements in Mexico City and São Paulo: A Citizen Participation Ladder for VGI. In Socio-Environmental Research in Latin America: Interdisciplinary Approaches Using GIS and Remote Sensing Frameworks; López, S., Ed.; The Latin American Studies Book Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 255–280. ISBN 978-3-031-22680-9. [Google Scholar]

- Sumo, P.D.; Arhin, I.; Danquah, R.; Nelson, S.K.; Achaa, L.O.; Nweze, C.N.; Cai, L.; Ji, X. An Assessment of Africa’s Second-Hand Clothing Value Chain: A Systematic Review and Research Opportunities. Text. Res. J. 2023, 93, 4701–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manieson, L.A. Castoff from the West, Pearls in Kantamanto? A Critique of Second-hand Clothes Trade. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 27, 811–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boimah, M.; Weible, D. “We Prefer Local but Consume Imported”: Results from a Qualitative Study of Dairy Consumers in Senegal. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 35, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.T. Second-Hand Clothing Encounters in Zambia: Global Discourses, Western Commodities, and Local Histories. Africa 1999, 69, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSD. Enquête Harmonisée sur les Conditions de Vie des Ménages (EHCVM II) au Sénégal: RAPPORT FINAL; Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie: Dakar, Senegal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Senegal Average Monthly Wage. Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/senegal/wages (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Esselaar, S.; Stork, C. Mobile Cellular Telephone: Fixed-Line Substitution in Sub-Saharan Africa. S. Afr. J. Inf. Commun. 2005, 2005, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. Are Main Lines and Mobile Phones Substitutes or Complements? Evidence from Africa. Telecommun. Policy 2003, 27, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arentze, T.A.; Oppewal, H.; Timmermans, H.J.P. A Multipurpose Shopping Trip Model to Assess Retail Agglomeration Effects. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 42, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. A Perceptual Approach to Retail Agglomeration. Area 1987, 19, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mushinski, D.; Weiler, S. A Note on the Geographic Interdependencies of Retail Market Areas. J. Reg. Sci. 2002, 42, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thilmany, D.; McKenney, N.; Mushinski, D.; Weiler, S. Beggar-Thy-Neighbor Economic Development: A Note on the Effect of Geographic Interdependencies in Rural Retail Markets. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2005, 39, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaschenko, A.; Stolbova, A.; Golovnin, O. Spatial Clustering Based on Analysis of Big Data in Digital Marketing. In Artificial Intelligence; Kuznetsov, S.O., Panov, A.I., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Sigué, O.; Zoma, V. Transport International de Véhicules d’occasion Entre Le Burkina Faso et Le Togo: Un Exemple de Mondialisation Par Le “Bas.”. Djiboul 2022, 1, 470–487. [Google Scholar]

- Asante, K.A.; Amoyaw-Osei, Y.; Agusa, T. E-Waste Recycling in Africa: Risks and Opportunities. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2019, 18, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoku, A.; Agbalenyo, M.; Laude, J.; Ajibola, T.F.; Attah, M.A.; Sarko, S.B. Environmental Injustice and Electronic Waste in Ghana: Challenges and Recommendations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Sekyere, K.; Aladago, D.A.; Leverenz, D.; Oteng-Ababio, M.; Kranert, M. Environmental Impacts on Soil and Groundwater of Informal E-Waste Recycling Processes in Ghana. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, K.; Uchendu, C.; Fitzpatrick, C. Quantifying Used Electrical and Electronic Equipment Exported from Ireland to West Africa in Roll-on Roll-off Vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, M.N.; Ntsala, P.G.; Schenck, C.; Crozier McCleland, J.; van Dyk, E.E.; Petersen, J. Drivers, Barriers and Enablers of a South African Circular Solar PV Module Supply Chain: A Focus on Reuse. Waste Manag. Res. 2025, 0, 0734242X251340306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Mobile Phones, Livelihoods and the Poor in Sub-Saharan Africa: Review and Prospect. Geogr. Compass 2012, 6, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G.; Hampshire, K.; Abane, A.; Munthali, A.; Robson, E.; Mashiri, M.; Tanle, A. Youth, Mobility and Mobile Phones in Africa: Findings from a Three-Country Study. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2012, 18, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. Product Use and Welfare: The Case of Mobile Phones in Africa. Telemat. Inform. 2014, 31, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Towards a Geography of Geographic Information in a Digital World. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 1997, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K. Central Places: The Theories of von Thünen, Christaller, and Lösch. In Foundations of Location Analysis; Eiselt, H.A., Marianov, V., Eds.; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 471–505. ISBN 978-1-4419-7572-0. [Google Scholar]

- Boo, G.; Darin, E.; Thomson, D.R.; Tatem, A.J. A Grid-Based Sample Design Framework for Household Surveys. Gates Open Res. 2020, 4, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.L.; Creamer, W.; Dolan, C.S.; Plattner, S.; Polier, N.; Roberts, B.D.; Rothman, M.S.; Stanford, L.; Stone, M.P.; Vargas-Cetina, G.; et al. Commodities and Globalization; Haugerud, A., Stone, P.M., Little, P.D., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8476-9943-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C.; Marmont, G. Global Commodity Circuits. In Research Handbook on the Sociology of Globalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, UK, 2023; pp. 45–59. ISBN 978-1-83910-157-1. [Google Scholar]

- Xavier, L.H.; Ottoni, M.; Lepawsky, J. Circular Economy and E-Waste Management in the Americas: Brazilian and Canadian Frameworks. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Repairs | Sales | Sales and Repairs | Grand Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Services | 408 | ||||

| Sales/Repairs | 13 | 186 | 126 | 327 | Number of shops selling digital devices = 583 |

| Sales/Repairs—Digital Services | 3 | 218 | 35 | 256 | |

| Grand Total | 16 | 404 | 161 | 991 | |

| Local Second-Hand Electronics | Imported Second-Hand Electronics | |

|---|---|---|

| Origins | Senegal (or less frequently neighboring countries, especially Mauritania). | Mainly Europe or Canada. |

| Quality and Condition | Often heavily used. Condition attributed to longer usage period, and local conditions make maintenance harder (higher temperatures and dust). | Perceived as higher quality. More trust regarding the state of the item. |

| Price | Cheaper, no transport or tax costs involved. | Generally more expensive. |

| Social Perception | Sometimes seen as less reliable or less modern. | Valued for quality and intrinsic worth. |

| Number of Shops Selling Smartphones | Selling New Smartphones | Selling Imported Smartphones | Selling Local Smartphones | Businesses That Have Indicated Their Prices |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 312 | 242 | 157 | 136 | 260 |

| Brand Sold | Number of Shops |

|---|---|

| Tecno | 273 |

| Samsung | 264 |

| Itel | 213 |

| iPhone | 207 |

| Huawei | 135 |

| Nokia | 69 |

| Alcatel | 43 |

| Sony | 28 |

| ZTE | 24 |

| MINIMUM Price for NEW Smartphone | MAXIMUM Price for NEW Smartphone | MINIMUM Price for IMPORTED Second-Hand Smartphone | MAXIMUM Price for IMPORTED Second-Hand Smartphone | MINIMUM Price for LOCAL Second-Hand Smartphone | MAXIMUM Price for LOCAL Second-Hand Smartphone | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samsung | −0.06 (p = 0.330) | −0.07 (p = 0.268) | −0.06 (p = 0.475) | −0.04 (p = 0.655) | 0.15 (p = 0.085) | 0.02 (p = 0.828) |

| iPhone | 0.02 (p = 0.798) | 0.28 (p = 0.000) | 0.17 (p = 0.032) | 0.30 (p = 0.000) | 0.25 (p = 0.004) | 0.33 (p = 0.000) |

| Huawei | −0.11 (p = 0.095) | 0.12 (p = 0.055) | −0.28 (p = 0.000) | −0.12 (p = 0.149) | 0.01 (p = 0.940) | 0.09 (p = 0.304) |

| Techno | −0.09 (p = 0.176) | −0.12 (p = 0.066) | −0.19 (p = 0.016) | −0.16 (p = 0.048) | 0.06 (p = 0.496) | −0.13 (p = 0.140) |

| Itel | −0.17 (p = 0.008) | −0.11 (p = 0.085) | −0.05 (p = 0.546) | −0.06 (p = 0.455) | −0.03 (p = 0.711) | −0.04 (p = 0.623) |

| Alcatel | −0.00 (p = 0.973) | 0.01 (p = 0.889) | −0.01 (p = 0.915) | −0.01 (p = 0.872) | −0.00 (p = 0.998) | −0.02 (p = 0.862) |

| Nokia | −0.13 (p = 0.050) | 0.02 (p = 0.717) | −0.03 (p = 0.687) | 0.07 (p = 0.379) | 0.11 (p = 0.201) | 0.06 (p = 0.464) |

| LG | 0.02 (p = 0.789) | 0.09 (p = 0.179) | −0.05 (p = 0.567) | 0.01 (p = 0.921) | 0.15 (p = 0.080) | 0.06 (p = 0.482) |

| Sony | −0.05 (p = 0.464) | 0.13 (p = 0.045) | −0.06 (p = 0.431) | 0.03 (p = 0.749) | −0.00 (p = 0.983) | 0.02 (p = 0.786) |

| ZTE | −0.09 (p = 0.166) | 0.03 (p = 0.653) | 0.00 (p = 0.966) | 0.04 (p = 0.654) | 0.12 (p = 0.161) | 0.10 (p = 0.268) |

| Lenovo | −0.01 (p = 0.845) | 0.16 (p = 0.010) | 0.10 (p = 0.196) | 0.20 (p = 0.012) | 0.18 (p = 0.033) | 0.16 (p = 0.068) |

| Azus | −0.11 (p = 0.085) | 0.15 (p = 0.023) | −0.02 (p = 0.842) | 0.14 (p = 0.074) | −0.02 (p = 0.843) | 0.14 (p = 0.110) |

| Acer | −0.11 (p = 0.093) | 0.16 (p = 0.010) | −0.04 (p = 0.638) | 0.12 (p = 0.142) | 0.02 (p = 0.776) | 0.14 (p = 0.116) |

| Infinix | −0.13 (p = 0.049) | 0.10 (p = 0.138) | −0.11 (p = 0.168) | −0.01 (p = 0.945) | 0.14 (p = 0.107) | 0.14 (p = 0.113) |

| Others | −0.02 (p = 0.748) | 0.09 (p = 0.142) | −0.02 (p = 0.799) | −0.05 (p = 0.567) | −0.01 (p = 0.924) | 0.01 (p = 0.943) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Roulet, P.; Chenal, J.; Munyaka, J.-C.B.; Diallo, M.; Mbaye, D.; Ndiaye, M.L.; Seye, M.R.; Adjanohoun, D.S.; Mbengue, T.; Sow, D.; et al. Electronics Shops in Saint-Louis: A Participative Mapping of Value, Quality, and Prices Within the Market Hierarchy in a Secondary Senegalese City. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198959

De Roulet P, Chenal J, Munyaka J-CB, Diallo M, Mbaye D, Ndiaye ML, Seye MR, Adjanohoun DS, Mbengue T, Sow D, et al. Electronics Shops in Saint-Louis: A Participative Mapping of Value, Quality, and Prices Within the Market Hierarchy in a Secondary Senegalese City. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198959

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Roulet, Pablo, Jérôme Chenal, Jean-Claude Baraka Munyaka, Moussa Diallo, Derguene Mbaye, Mamadou Lamine Ndiaye, Madoune Robert Seye, Dimitri Samuel Adjanohoun, Tatiana Mbengue, Djiby Sow, and et al. 2025. "Electronics Shops in Saint-Louis: A Participative Mapping of Value, Quality, and Prices Within the Market Hierarchy in a Secondary Senegalese City" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198959

APA StyleDe Roulet, P., Chenal, J., Munyaka, J.-C. B., Diallo, M., Mbaye, D., Ndiaye, M. L., Seye, M. R., Adjanohoun, D. S., Mbengue, T., Sow, D., & Wade, C. S. (2025). Electronics Shops in Saint-Louis: A Participative Mapping of Value, Quality, and Prices Within the Market Hierarchy in a Secondary Senegalese City. Sustainability, 17(19), 8959. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198959