Abstract

This study investigates the role of Modern Management Accounting (MMA)—which integrates Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK)—in driving Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) and Business Sustainability (BS) in Thai green hotels. Business Sustainability is conceptualized as the achievement of balanced outcomes across economic performance, social responsibility, and environmental stewardship. It addresses a theoretical debate by testing two competing SCA models: a disaggregated model (which separates SCA into Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA)) and a holistic model (which treats SCA as a unified construct). Data from 115 certified green hotels were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The results revealed a critical distinction between the models. In the disaggregated model, SMA and SCK contributed to both CEA and OEA, but only OEA directly enhanced BS and served as a partial mediator in the relationships from both SMA and SCK to BS, whereas CEA showed no significant mediating effects. Conversely, the holistic model demonstrated that overall SCA served as a partial mediator in the relationships from both SMA and SCK to BS, while also exerting a strong direct effect on BS. The study concludes that achieving business sustainability requires a holistic SCA that integrates both operational efficiency and customer experience, offering a comprehensive framework for strategic management in the hotel industry. These findings underscore the strategic imperative for hotel managers to cultivate an integrated competitive advantage, where superior customer experiences and operational excellence are synergistically managed, to ensure long-term business sustainability.

1. Introduction

The tourism sector has been identified by the United Nations as one of the key sectors driving the transition towards a Green Economy, playing a significant role in sustainable development across all dimensions: environmental, social, and economic [1]. Thailand’s tourism industry constitutes approximately 12% of the national GDP, serving as a crucial pillar driving the national economy [2]. Over the past decades, the Thai tourism industry has experienced continuous growth, establishing Thailand as one of the world’s leading tourist destinations with diverse attractions [3]. In the pre-COVID-19 period (2019), Thailand was ranked as the 8th most popular tourist destination globally, welcoming over 39.8 million international visitors [4]. According to recent data, Thailand was ranked as the 4th most popular tourist destination in 2023, with over 28 million international arrivals [5], reflecting the potential and resilience of the Thai tourism sector in recovering from the pandemic crisis.

Thailand’s hotel sector is an integral part of tourism and a vital economic component [6]. However, the hotel sector currently faces increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices due to its high resource consumption and waste generation [7,8]. In response to these challenges, sustainability certifications have emerged as key tools to verify and affirm hotels’ commitment to sustainable operations [9,10]. The Thai Hotel Association encourages the hotel sector to obtain voluntary sustainability certifications to demonstrate the industry’s commitment to sustainability. Widely recognized sustainability certifications, as listed in the Thai Hotel Directory 2022, include the Green Hotel Standard (GHS) [11]. However, these certifications predominantly focus on the environmental dimension, while the economic and social outcome dimensions remain understudied and inadequately integrated.

Modern Management Accounting (MMA) has evolved from traditional cost-control functions into a strategic tool that supports decision-making and sustainable performance [12]. Two key components of MMA—Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK)—have been identified as significant drivers for organizational innovation and performance [13]. Nevertheless, empirical evidence on the impact of MMA on sustainability within the service sector, particularly in green hotels, remains limited.

Furthermore, while Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) is widely acknowledged as a precursor to Business Sustainability (BS), a significant gap exists in the literature regarding its conceptualization and measurement. There is a lack of consensus between a disaggregated approach (e.g., distinguishing between Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA)) and a holistic approach (treating SCA as a unified construct) [14,15,16]. This theoretical ambiguity is particularly evident in the context of emerging economies like Thailand, where resource constraints and market dynamics may influence how green hotels leverage internal capabilities like MMA to achieve sustainability.

Although some research exists on sustainability certifications and green hotel practices, most studies primarily focus on the environmental dimension of sustainability, whereas the integration of economic and social dimensions remains less explored [9,11]. Specifically, the role of internal management tools, such as Modern Management Accounting (MMA)—comprising Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK)—in promoting sustainable business outcomes lacks systematic investigation in the context of green hotels. Moreover, although Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) is considered a crucial mediator, the mechanisms and appropriate measurements remain unclear.

In this study, Modern Management Accounting (MMA) is conceptualized as a strategic capability that integrates internal process management through Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and external market insights through Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK). Grounded in the Resource-Based View, we posit that this integrated MMA system serves as a valuable, rare, and non-substitutable resource. It enables hotels to build a Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) not only by enhancing operational efficiency and cost control but also by fostering innovative, customer-centric service experiences. Ultimately, it is this synergistically built SCA that drives long-term sustainable business outcomes, allowing hotels to balance economic performance with environmental and social responsibilities.

This study aims to address these research gaps within the specific context of Thailand’s green hotel industry by employing Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test and compare two competing conceptual models: one employing a disaggregated approach to SCA and another utilizing a holistic approach. By comparing these two models, this study aims to provide both theoretical clarity on the nature of SCA and practical insights into how hotel managers can best leverage management accounting practices and customer knowledge to achieve long-term business sustainability.

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, it offers empirical evidence clarifying the theoretical debate on SCA measurement by demonstrating the superior explanatory power of a holistic model over a disaggregated one in translating MMA practices into sustainability outcomes. Second, it extends the Resource-Based View by empirically validating MMA—as an integrated bundle of SMA and SCK—as a strategic resource that builds SCA. Finally, it provides actionable guidance for practitioners in the green hotel industry, highlighting that investing in holistic competitive advantage, which balances customer experience with operational efficiency, is paramount for achieving long-term business sustainability.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Modern Management Accounting

Prior to the 20th century, Traditional Management Accounting was the primary system used by managers for decision-making. Subsequently, changes in the business environment and intense competition led organizational managers to strive to improve their operational processes to ensure business continuity. A key factor in managerial decisions for operational improvement is reliable information that aligns with the changing nature of the business operating environment. However, Traditional Management Accounting primarily focused on analyzing historical financial data and emphasized budgetary control [17]. This resulted in traditional management accounting systems providing insufficient information for managers to develop strategic plans for business survival in a rapidly changing landscape [17,18,19]. This gap provided the impetus for the development of the concept of Modern Management Accounting. Modern Management Accounting (MMA), as examined in this study, focuses on the practices of management accounting adapted to an organization’s operating environment. It emphasizes providing information to support internal decision-making, enhancing operations, and enabling the execution of organizational strategy.

This study is grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV) of the firm. RBV theory posits that organizational resources which are Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Non-substitutable (VRIN) can serve as the foundation for achieving a Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) [20,21,22]. Modern Management Accounting (MMA) is characterized as such a strategic organizational resource. As an integrated system, MMA combines the forward-looking, internal process focus of Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) with the external, market-oriented intelligence of Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK). This combination creates a unique capability that is difficult for competitors to imitate. MMA prioritizes a forward-looking perspective and seeks solutions for operational issues even before standard remedies exist, enabling organizations to gather data that supports managerial decision-making in the form of Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) [23] and systematic customer knowledge through tracking, collecting, and analyzing data to understand customer needs, behavior, value, as well as experiences and expectations [24,25]. This facilitates the creation of distinctive experiences and added value for customers through efficient service, smooth operations, and service innovation [26], characterizing Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK). Therefore, RBV is employed as the overarching theoretical lens to explain the causal relationships between Modern Management Accounting (comprising SMA and SCK), Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA), and Business Sustainability (BS). The core proposition is that MMA, as a holistic system, provides the critical information and analytical foundation that allows a firm to build the dual advantages of superior customer experience and operational excellence, which together form a sustainable competitive advantage leading to business sustainability.

2.1.1. Strategic Management Accounting

Management accounting techniques in the service industry, particularly in the hotel business, necessitate a shift from traditional techniques with a short-term financial perspective to modern techniques that adopt a long-term financial and non-financial view. These modern techniques can create more favorable conditions for business sustainability. Although modern techniques offer several advantages, challenges in implementation remain [27]. Research has highlighted important contemporary practices implemented in hotel enterprises, such as activity-based costing, product life-cycle costing, target costing, and balanced scorecard [28].

Activity-based costing (ABC) is a prominent tool for accurate per-unit cost calculation through the process of allocating costs to various activities. Unlike traditional cost accounting methods, ABC provides a comprehensive view of the costs and performance of activities, both current and future. It is a key tool that supports managerial decision-making and aids in effective cost management [27]. Furthermore, ABC serves as a crucial foundation for customer profitability analysis, as it enables the accurate allocation of total costs to individual customers [29]. Consequently, ABC is recognized as one of the most widely implemented management accounting tools in the service and hotel industry [27] and plays a significant role in strategy formulation and building competitive advantage in service businesses [30]. Therefore, ABC is not merely a cost management tool but also a fundamental technique for achieving effective cost management and building long-term Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) for organizations [30].

The application of an ABC system aids in analyzing and determining the true cost of each activity within the value chain, such as the cost of providing room service, restaurant operations, and ancillary services like spas and golf courses. This leads to the ability to set appropriate service prices, identify inefficient activities, and make evidence-based strategic decisions regarding service value addition or cost reduction [31]. Understanding true costs also facilitates resource management to enhance reliability and operational efficiency. ABC thus contributes significantly to building long-term Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) for organizations [30] by directly improving operational process efficiency [32], enabling sustainable cost reduction, and strengthening the foundation for sustainable business operations [30], as well as ensuring long-term business survival [27].

Product Life Cycle (PLC) is a strategic concept used to analyze and manage the development of a product or service throughout its entire life cycle, which consists of five main stages: development, introduction, growth, maturity, and decline. The ultimate goal is to maximize long-term profit through effective cost management [32].

Applying PLC in the hotel business serves as a key tool for strategic marketing and financial planning. PLC helps hotels assess the total costs incurred throughout the life cycle of a “service package” or “room type,” from design and marketing to maintenance and continuous service improvement. This enables hotels to plan investments and manage resources efficiently [33]. Understanding each stage of the PLC allows hotels to formulate appropriate pricing strategies for each period. For example, during the introduction phase, a hotel might use promotional rates to attract customers; during growth, it might gradually increase prices as demand rises; and during maturity, it might employ stable pricing strategies to adapt to changing customer demands over time [32]. Moreover, PLC is crucial for long-term planning, helping hotels use insights to maintain standards of reliability and service quality in the long run [34]. This strategic cost and pricing management throughout a service’s life cycle is essential for driving sustainable growth.

Target Costing (TAR) is a popular strategic cost management tool based on the principle of market-driven pricing as the foundation for setting the target cost of a product or service [33]. This approach enables organizations to set prices for goods and services that align with market demands and customer affordability [35]. Target Costing has been found to promote continuous process improvement and support cost reduction through efficient product design, leading to competitiveness with reasonable costs [36]. This effective cost planning and control benefits both the organization and the customer [37]. Furthermore, Target Costing plays a significant role in promoting interdepartmental collaboration and aids in design-stage cost control [38]. It is thus a foundational practice for optimizing service costs.

From a sustainability perspective, Target Costing not only supports efficient resource use and waste reduction but also helps create economic stability for the organization [32], which aligns with the principles of sustainable development [39]. Various service sectors apply Target Costing in developing new services that meet customer needs while effectively controlling costs [40]. Particularly in the hotel industry, Target Costing is used to design new service packages and experiences by setting costs appropriate to the price customers are willing to pay, which is a crucial approach for maintaining competitiveness [33]. This practice also aligns with environmental conservation and responding to diverse customer needs [34,41]. Therefore, Target Costing is not merely a financial tool but a management strategy that helps organizations build competitive advantage through effective cost management and appropriate response to market demands.

Balanced Scorecard (BSC) is a strategic performance measurement framework that evaluates organizational performance through four balanced perspectives: the financial perspective, the customer perspective, the internal process perspective, and the learning and growth perspective [42]. The mechanism of BSC is designed to link from the internal perspectives of learning and processes to the external perspectives of customers and finance [29]. Applying BSC in the hotel industry helps managers analyze areas of inefficiency and develop strategies to effectively increase profits. Because BSC integrates both financial and non-financial indicators, organizations can assess performance comprehensively and create linkages between operations and corporate strategy, leading to competitive advantage [27].

Hotels facing high competition are more likely to implement BSC alongside benchmarking to further strengthen their strategic position [27]. Key indicators include the customer perspective (measuring satisfaction and customer retention rates), the internal process perspective (assessing service efficiency and quality standards), the learning and growth perspective (evaluating human capital development and employee training), and the financial perspective (tracking revenue and profitability). This makes BSC an essential tool for fostering a culture of continuous upskilling and driving sustainable growth by effectively linking daily operations with the organization’s long-term strategic goals [43]. It is an essential management tool for modern service organizations seeking to navigate complex market environments while maintaining strategic focus.

Total Quality Management (TQM) is another crucial tool for the service sector. Top management must prioritize adopting the TQM framework to achieve Business Sustainability [44]. Beyond using TQM to drive organizational goals, TQM also helps foster an environmentally friendly culture [45]. These environmentally friendly operations significantly enhance environmental, economic, and social outcomes [46], as TQM is a systematic approach to total quality management that emphasizes continuous improvement, employee involvement, and customer satisfaction [47]. It creates an organizational culture where everyone is quality-conscious, empowering employees to solve customer problems immediately, thereby continuously improving service processes [34]. This focus on quality and process excellence is fundamental to ensuring reliable service delivery. This helps reduce service errors, increase customer satisfaction and loyalty, and create competitive advantage through consistent service quality [31]. Originally associated with service quality development and operational efficiency, TQM is now recognized as a key tool for promoting environmental sustainability [47]. Organizations that integrate TQM with sustainability concepts show improvements in waste management and resource efficiency, leading to enhanced environmental performance. This is achieved by empowering employees to improve resource efficiency and by embedding environmentally friendly principles into organizational processes to drive environmental responsibility [48,49], creating opportunities for employee participation in promoting a sustainability culture aligned with long-term environmental goals [50].

2.1.2. Strategic Customer Knowledge

In the digital age, where competition in the hotel industry is intensifying, gaining a deep understanding of customers has become a crucial factor for survival and sustainable growth. Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) refers to the process of tracking customer data, systematically collecting information, and analyzing it to gain profound insights into customer needs, behavior, and value, and utilizing this customer information for strategic decision-making [24]. This knowledge encompasses not only basic customer information but also an understanding of customer experiences, expectations, and satisfaction with services [25]. Hotels can differentiate themselves and create added value for customers by delivering exceptional experiences, which include superior service, efficient operational management, and innovation in products or services [26]. The use of strategic customer knowledge enables hotels to understand evolving customer needs and expectations and adapt swiftly to meet them. Therefore, the process of acquiring SCK can be systematically categorized into three key activities: (1) data tracking from online channels and reviews, (2) data aggregation and systematic collection, and (3) value analytics through techniques like topic modeling (LDA) and sentiment analysis to extract actionable insights for strategic decision-making [24,51].

Regarding tracking and collecting customer data, hotels today primarily focus on utilizing online channels as a key source for understanding customers. The main method employed is text mining from customer online reviews and comments, particularly from travel platforms such as TripAdvisor, Ctrip, and Booking.com [24]. Utilizing this data can help overcome the limitations of traditional data collection methods, such as surveys, which may provide insufficient data or lack customer perspectives [52]. Extracting useful insights from these reviews is another challenging task. Currently, collected data are analyzed using various techniques. Most research related to the application of online hotel reviews falls into two main categories: Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) to identify topics customers care about, reflecting the most important service attributes for use as evaluation dimensions and to support hotel management [53,54,55], and sentiment analysis to gauge customer opinions, including emotions and feelings towards various service attributes [17,56,57]. The systematic collection and analysis of customer data helps reflect customer satisfaction, a key factor in customer decision-making, including booking intentions, loyalty, and business reputation. It enables organizations to understand what customers truly want, leading to the design of more targeted and valuable services [24] and allows for effective prioritization of service development [51]. Particularly, tracking customer feedback enables organizations to improve services promptly and create satisfaction that surpasses competitors, leading to the building of Customer Loyalty and sustainable growth [52]. This understanding and responsiveness to customer needs also increases Customer Retention rates, which is less costly than acquiring new customers, and impacts long-term business sustainability [24]. This capability is directly linked to achieving effective customer retention.

2.2. Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) is defined as an organization’s ability to maintain a sustained and difficult-to-imitate advantage over competitors [58,59]. In this study, SCA is considered in two forms: a disaggregated measurement, comprising Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA), and a holistic measurement, which integrates various dimensions into a single construct.

Multiple studies support the holistic measurement of SCA, as it reflects the complexity and dynamism of the modern competitive environment [14,15]. Furthermore, SCA is viewed as a crucial mediating variable linking internal organizational capabilities (e.g., the use of modern management accounting tools) to Business Sustainability.

2.2.1. Customer Experience Advantage

In the highly competitive business environment of the hotel industry, Service Innovation has proven to be a key mechanism for creating a Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA). Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) is not limited to the adoption of new technologies but also includes improving service processes, designing customer experiences, and developing new business ecosystems that can effectively deliver holistic value to customers.

The fundamental concept of service innovation has transitioned towards Individualized Service, which involves services designed and delivered to meet the specific, detailed, and precise needs of each individual customer, moving away from a “one-size-fits-all” approach [60,61]. The ability to tailor services based on context and customer feedback, along with a focus on creating Personalized Experiences, generates added value through attentive service. This continuous service development extends to building partnership-like relationships with customers through Value Co-creation between service providers and recipients, or even between personnel and technology [62]. In this context, customers play the role of Value Co-creators, not just passive recipients. The provision of attentive service and the capacity to surpass customer expectations culminate in perceptions of service novelty, precision, and exceptional value, thereby eliciting a pronounced ‘wow effect’. This feeling forms the foundation of competitive advantage. Since understanding consumer expectations is crucial for creating excellent service [63], hotels must engage in continuous service development by upgrading existing products and services to create new, unique value propositions. Building a Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) therefore relies on a hotel’s ability to excel in three core areas: the ability to develop and offer unique service innovations that create a ‘wow effect’, the capability for rapid service launch to responsively meet market demands, and the proficiency in delivering needs-based service recommendations through personalization and value co-creation with customers [64,65]. This leads to building a base of loyal customers (Loyalty) who return regularly and attract new customers through Word-of-Mouth, ultimately becoming service innovations that ensure business sustainability [64,65]. These new service offerings must be launched quickly and responsively to market demands [66].

Creating a competitive advantage through distinctive innovation management to outperform competitors and continuously attract tourists, or to add value for customers, relies on several components [67]. These include the knowledge, vision, and efficiency of personnel at all levels, as well as the organization’s overall capability to create and manage innovation concretely throughout the entire service process, from end to end [68]. New services created by hotels must meet customer needs and deliver value for both parties. That is, service providers or employees feel proud and involved in innovating services that can be quickly brought to market, while service recipients or customers feel satisfied with receiving good, modern, and valuable service. This strategy necessitates business processes integrated with diverse knowledge domains, under the concept of Co-creation, to design processes and present new propositions that create added value for both internal and external customers [69].

Sustainable competitive advantage in the context of CEA is defined as an advantage that is difficult to imitate or eliminate, can be sustained for a significant period, and serves as a fundamental basis for the company’s long-term superior performance compared to competitors. It was concluded that hotels capable of building a sustainable competitive advantage must possess resources and capabilities that are not easily replicated by competitors [70]. This advantage provides long-term benefits and helps hotels consistently perform better than competitors in terms of service quality [71,72] creating barriers to entry for new competitors and fostering customer loyalty, leading to sustained success in the hotel industry.

2.2.2. Operational Efficiency Advantage

Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) is a crucial factor in building a sustainable competitive advantage, especially in a rapidly changing business environment [73,74]. The literature indicates that OEA is reflected not only through cost reduction but also through continuous process improvement, increased resource productivity, and customer retention.

Cost reduction reflects operational capabilities that are the foundation of cost leadership strategy [67]. Research has found that using tools such as Activity-Based Costing and Target Costing can help reduce costs by 15–25% [75]. However, the core of operational efficiency is continuous process improvement to increase accuracy and reduce errors. Implementing Quality Management Systems helps reduce unnecessary costs and increase profits [75]. This advantage gives businesses more options, either in setting prices lower than competitors or increasing profit margins for investment in innovation. Effective cost management is therefore not just about reducing costs but about allocating resources to create maximum value [56].

In terms of increasing resource productivity, especially in service businesses, the optimal use of resources, both human resources and equipment, aligned with demand, can increase operational efficiency by 20–40% [41]. This efficient resource utilization impacts organizational performance and sustainability image. Furthermore, efficient resource management, such as energy and water management, impacts organizational performance and sustainability image. In an era where consumers increasingly value environmental sustainability [76], demonstrating a commitment to sustainable resource management contributes to building an emotional connection with customers [77]. Sharing these common values helps build long-term loyalty, making customers more likely to return and recommend the business, supporting sustainable growth [78].

The ability to retain customers is another aspect that reflects operational efficiency and is considered a sustainable competitive advantage, as it benefits both financial performance and organizational image. Delivering reliable service leads to satisfaction and customer retention, which is crucial for achieving long-term competitive advantage. It was found that a 5% increase in customer retention rate can lead to a significant increase in profits [56]. Research from Harvard Business Review states that profits can increase by 25–95%. Moreover, loyal customers tend to spend 67% more than new customers, and 80% of future profits come from just 20% of regular customers. Furthermore, operational efficiency transcends internal processes; it is ultimately reflected in outcomes such as effective customer retention. The ability to retain customers is a direct result of reliable service delivery and effective cost management that provides value, making it a key indicator of a sustainable operational advantage [56,75].

In summary, OEA is a strategic approach that integrates multiple components: cost reduction, process improvement, resource productivity enhancement, and customer retention. Developing these capabilities in an integrated manner helps build a sustainable competitive advantage in the long term.

2.3. Business Sustainability

In this study, Business Sustainability (BS) refers to the attainment of balanced and sustainable outcomes across three core dimensions: economic performance (profitability and growth), social responsibility (employee development and community impact), and environmental stewardship (resource efficiency and waste reduction). This outcome-focused conceptualization aligns with the Triple Bottom Line framework [79] and emphasizes measurable results rather than operational practices alone. This concept is not limited to maximizing profits but focuses on creating long-term value for all stakeholders, including customers, employees, partners, and the community. The goal is to ensure stable and sustainable future growth for the business, anchored in the core principle of the “Triple Bottom Line” or “3Ps” (People, Planet, and Profit) [79].

Continuous employee skill development is a key factor driving organizational sustainability [80]. Training that covers both technical skills and sustainability awareness enhances performance and fosters a sustainable organizational culture [81]. Employee training represents the People dimension, a fundamental pillar of business sustainability, especially in the hotel business, as employees play a direct role in operations and customer interactions. Sustainability-focused training equips employees with knowledge about issues such as energy conservation, waste management, and water conservation, which not only helps reduce environmental impact but also lowers operational costs, touching upon the Planet and Profit dimensions simultaneously [32]. This commitment to continuous learning is encapsulated in the practice of upskilling continuously. Furthermore, training encourages employees to develop constructive attitudes, propose new ideas for sustainable operations, and effectively communicate and explain the hotel’s environmentally friendly practices to customers [82].

Building sustainability into the supply chain is another critical aspect that cannot be overlooked. Hotels that select reliable partners and suppliers with sustainable practices aligned with their own, particularly through local sourcing of materials, not only help reduce carbon emissions from transportation (Planet dimension) but also support the local economy and create an authentic feel for the customer experience [83]. Additionally, choosing partners based on ethical considerations, such as ensuring they adhere to fair labor standards and proper health and safety guidelines (People dimension), builds strong and transparent relationships with suppliers, enabling hotels to cultivate reliable partnerships and achieve long-term sustainability goals effectively [83].

Effective cost control is the foundation of economic sustainability [84]. Efficient cost management allows hotels to increase profits and allocate resources appropriately in the long run (Profit dimension) [85]. Modern cost control extends beyond mere accounting figures to include environmentally friendly operations (Planet dimension). For example, controlling food and beverage costs through portion control and smart inventory management not only saves expenses but also reduces waste [41]. Or, controlling costs related to resource use, such as water and energy, not only reduces expenses (directly benefiting profit) but also allows hotels to use resources efficiently, reduce waste generation, and lower carbon emissions [34]. Therefore, standardized service cost control is a key strategy for optimizing service costs and balancing profitability and environmental care simultaneously, enabling sustainable long-term business growth.

Business growth and sales are indicators of the ability to survive and generate long-term profits. Hotel businesses must understand customer needs and make precise service improvements, leading to increased customer satisfaction and brand loyalty [24]. This satisfaction is a fundamental basis for economic sustainability in the service industry, as it directly influences customer booking decisions and word-of-mouth recommendations [86]. In a highly competitive business world, steady revenue and profit growth demonstrate that a hotel can effectively build a competitive advantage [87]. Applying the Product Life Cycle (PLC) concept to manage costs and set pricing strategies at different stages of a product or service’s life helps hotels maximize long-term profits and maintain a strong market position [32]. Sustainable profits provide hotels with the capital to invest further in other aspects of sustainability, such as installing energy-saving systems, using eco-friendly materials, or continuous employee training, enabling the hotel to operate fully and balance the Triple Bottom Line. Revenue growth is therefore necessary to support the long-term development of the People and Planet dimensions. Ultimately, these interconnected practices are fundamental to a hotel’s ability to drive sustainable growth.

In operational terms, achieving Business Sustainability (BS) in the hotel industry requires a multifaceted strategy: investing in people through continuous employee development (Upskill Continuously), ensuring ethical and sustainable supply chains by Cultivating Reliable Partnerships, enhancing economic and environmental performance through Optimizing Service Costs, and ultimately Driving Sustainable Growth that balances all three dimensions of the triple bottom line [79].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study aims to test the structural relationships between Modern Management Accounting (MMA)—comprising Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK)—Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA), and Business Sustainability (BS). It adopts a comparative analysis of relationship models to examine the importance of SCA as a mediating variable. The hypotheses are grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV) [58] and knowledge-based theory [88], which posit that internal capabilities and knowledge resources are fundamental to achieving sustained competitive advantage and long-term performance.

We compared two distinct conceptual models:

- Model 1 (The Disaggregated Approach): This model conceptualizes the mediating variable of SCA by disaggregating it into its key dimensions: Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA).

- Model 2 (The Holistic Approach): This model conceptualizes the mediating variable of SCA as a holistic, unified construct, integrating various dimensions into a single latent variable.

This research framework was developed based on a comprehensive review of literature related to MMA and the development of competitive advantage and organizational performance using data or techniques from modern management accounting.

- Model 1: The Disaggregated Approach

Hypothesis 1a.

Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) has a positive effect on Customer Experience Advantage (CEA).

SMA tools such as Activity-Based Costing (ABC) provide a comprehensive view of costs and performance, enabling strategic decisions that support building competitive advantage [30,31].

Hypothesis 1b.

Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) has a positive effect on Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA).

Techniques like Target Costing promote continuous process improvement and support cost reduction through efficient design, leading to competitiveness with reasonable costs [33,36].

Hypothesis 1c.

Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

Effective cost control through modern SMA tools is the foundation of economic sustainability, allowing hotels to increase profits and allocate resources appropriately in the long run [33,84].

Hypothesis 2a.

Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) has a positive effect on Customer Experience Advantage (CEA).

SCK involves tracking and analyzing data to gain profound insights into customer needs and behavior, which enables hotels to differentiate themselves by delivering exceptional experiences [24,26].

Hypothesis 2b.

Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) has a positive effect on Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA).

Understanding customer needs through data analytics allows organizations to forecast demand and allocate resources optimally, enhancing operational efficiency by 20–40% [34,41].

Hypothesis 2c.

Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

SCK increases customer retention rates, which is less costly than acquiring new customers and significantly impacts long-term business sustainability [24,56].

Hypothesis 3.

Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

Creating a ‘wow effect’ through unique service innovations and personalization builds a base of loyal customers who return regularly and attract new customers through word-of-mouth [63,65].

Hypothesis 4.

Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

OEA, reflected through cost reduction and reliable service delivery, provides businesses with more options to set competitive prices or increase profit margins for investment, which is crucial for achieving long-term competitive advantage [15,75].

Hypothesis 5a.

Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) mediates the relationship between Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is expected that the effect of SMA on BS occurs through the organization’s ability to translate management information into creating valuable customer experiences.

Hypothesis 5b.

Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) mediates the relationship between Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is hypothesized that SMA enhances BS indirectly by improving operational efficiency and reducing waste, consistent with the principles of cost leadership and resource optimization [67,75].

Hypothesis 6a.

Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) mediates the relationship between Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is expected that the effect of SCK on BS occurs through the organization’s ability to translate customer knowledge into creating experiences that exceed expectations, thereby fostering loyalty and sustainable growth.

Hypothesis 6b.

Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) mediates the relationship between Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is anticipated that SCK improves BS indirectly by enabling more efficient resource allocation and process improvements derived from customer insights [41].

- Model 2: The Holistic Approach

Hypothesis 7a.

Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) has a positive effect on holistic Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA).

SMA provides crucial information for strategic decision-making [12], which is a fundamental capability for building a sustained and difficult-to-imitate advantage over competitors [58].

Hypothesis 7b.

Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

The cost management and efficiency derived from SMA support economic stability [32], which is a pillar of the sustainability triple bottom line.

Hypothesis 8a.

Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) has a positive effect on holistic Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA).

Deep customer knowledge allows organizations to adapt swiftly to evolving market demands [24], constituting a core capability that creates a sustainable competitive advantage [70].

Hypothesis 8b.

Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

SCK enables organizations to retain valuable customer bases and develop services that align with long-term needs [24], directly impacting business survival and growth [86].

Hypothesis 9.

Holistic Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) has a positive effect on Business Sustainability (BS).

Consistent with the Resource-Based View (RBV), a holistically measured sustainable competitive advantage is a primary driver of business sustainability [14,16].

Hypothesis 10.

Holistic Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) serves as a mediator in the relationship between Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is expected that the effect of SMA on BS occurs entirely through the building of SCA, as SMA tools act as an enabler for building internal capabilities rather than directly impacting performance outcomes [14,58].

Hypothesis 11.

Holistic Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) serves as a mediator in the relationship between Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) and Business Sustainability (BS).

It is expected that the effect of SCK on BS occurs partially through the building of SCA, as customer knowledge can also be used directly in decision-making to support sustainability, beyond its role in building advantage [24].

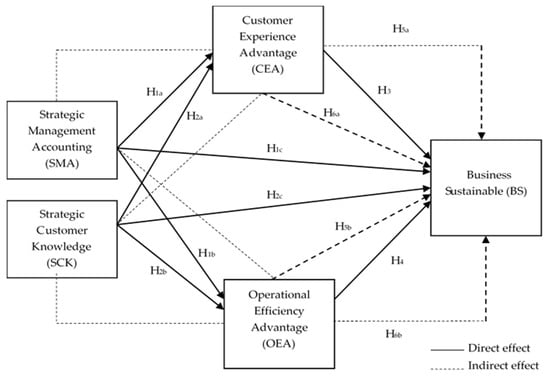

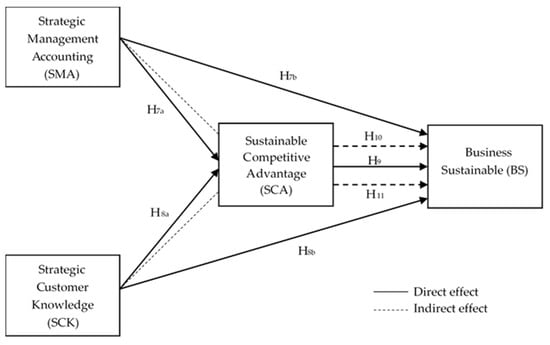

The conceptual frameworks representing the hypothesized relationships for both models are presented in Figure 1 and Figure 2. Figure 1 illustrates the disaggregated approach (Model 1), where SCA is operationalized through its two distinct dimensions: CEA and OEA. Figure 2 depicts the holistic approach (Model 2), where SCA is modeled as a unified higher-order construct. The specific paths corresponding to each hypothesis (H1a–H6b for Model 1 and H7a–H11 for Model 2) are indicated on the respective figures.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of research model 1. (Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Disaggregated Approach).

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework of research model 2. (Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Holistic Approach).

3.2. Data Collection and Potential Biases

The population for this study consists of Green Hotels in Thailand, which are lodging establishments that utilize resources and energy efficiently and effectively, manage pollution and the environment well, participate in preserving arts, culture, local wisdom, and contribute to local development (www.greenhotelthai.com). A purposive sampling method was employed. To mitigate potential Common Method Variance (CMV), several procedural remedies were implemented during the research design phase, including psychological separation of measurement scales through distinct questionnaire sections, varied instructional sets across constructs to reduce automatic responding, and explicit anonymity assurance to encourage honest responses.

The closed-ended questionnaire was developed based on established concepts, theories, and relevant research from textbooks and documents. All measurement indicators were adapted from prior studies and assessed using a seven-point Likert scale. It is important to note that the construct of Business Sustainability (BS) was measured using perceptual measures, capturing managers’ assessments of sustainability outcomes (e.g., their perception of cost optimization, growth, and partnership efficacy) rather than objective, audited metrics. This approach is consistent with the study’s focus on strategic-level perceptions and managerial decision-making. The questionnaire was distributed to hotels certified with the Green Hotel standard between 2018 and 2024 across all provinces in Thailand, totaling 378 hotels. A total of 115 completed and usable questionnaires were returned, yielding a response rate of 30.42%. This exceeds the minimum acceptable response rate of 20% [89]. Complementing these procedural measures, comprehensive statistical tests for CMV assessment were conducted, with results detailed in Section 4.2.

3.3. Data Analysis Method

This research employs Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test the relationships between Modern Management Accounting, Sustainable Competitive Advantage, and Business Sustainability. PLS-SEM is a statistical method widely used in social science and business management research. It is suitable for path analysis, which models causal relationships between exogenous and endogenous latent variables, and can analyze both direct and indirect effects between variables. Furthermore, PLS-SEM is robust for analysis with limited sample sizes and data that may not meet strict distributional assumptions, providing reliable predictive accuracy [90].

3.4. Preliminary Analysis

The preliminary analysis involved testing the content validity of the questionnaire, which was assessed and provided feedback by five experts. The Index of Item Objective Congruence (IOC) was calculated, yielding values between 0.60 and 1.00, all exceeding the threshold of 0.50. This indicates that the questionnaire items are congruent with the research objectives [91]. Subsequently, internal consistency reliability was tested through a pilot study using 30 responses. The analysis resulted in Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.807 to 0.962, all exceeding 0.70, confirming the questionnaire’s reliability for the main data collection [90].

As this is a quantitative study with a survey research design, utilizing a structured questionnaire developed from previous related research, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to confirm the consistency among the observed variables within each latent construct. This step was necessary as the questionnaire items were adapted from existing research and contextualized for the sample. The EFA assessment criteria included the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index > 0.50, Bartlett’s test of sphericity significance (p-value < 0.05) [92], and Eigenvalues ≥ 1.00 [90].

Table 1 shows the EFA results. The KMO indices range from 0.738 to 0.878 (all > 0.50), the p-values for Bartlett’s test of sphericity for all constructs are less than 0.05, and the Eigenvalues range from 1.077 to 4.476 (all ≥ 1.00). These results indicate that the observed variables for each construct are consistent and load appropriately onto their respective factors.

Table 1.

Exploratory factor analysis.

Based on the review of past literature on competitive advantage, which often distinguishes dimensions relevant to the service industry, the researchers posited two key dimensions: customer experience and operational efficiency. This theoretical distinction informed our disaggregated approach (Model 1). The EFA results confirm this distinction for Sustainable Competitive Advantage. The KMO value for SCA is 0.847 (>0.50), Bartlett’s test is significant (p < 0.05), and the Eigenvalues for Customer Experience Advantage (CEA = 4.476) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA = 1.077) are both greater than 1.00. This clear statistical separation validated our analysis of the structural relationships by examining the mediating role of competitive advantage in two forms: the disaggregated approach (Model 1) and the holistic approach (Model 2). This comparative approach allows for conclusions on how MMA influences different types of competitive advantage and which form more effectively drives sustainable business performance.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics of Green Hotels and Profile of Respondents

Among the 115 certified Green Hotels included in the study, 47.8% held the Gold level certification, 32.2% held the Silver level, and 20.0% held the Bronze level. The majority of these hotels (40.0%) had been in operation for more than 20 years, and a significant portion (39.1%) were large-scale enterprises with over 150 employees. These findings indicate that the Green Hotels in this sample are predominantly large, established operations, motivated by Green Hotel certification to attract customers and achieve operational sustainability. The key informants for this study were primarily Directors or Managers of the Accounting Department (67.80%). The majority held a Bachelor’s degree as their highest level of education (90.4%), had over 20 years of work experience (50.4%), and were involved in strategic operational planning (50.4%) as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic of green hotels and profile of respondents.

4.2. Subsection

The presentation of results begins with the assessment of the measurement model. This includes testing indicator reliability, evaluated based on loadings exceeding 0.708. For Model 1, loadings ranged from 0.644 to 0.935. Although the factor loadings for TAR (Target Costing, 0.644) and OEA4 (0.678) were slightly below the 0.708 threshold, they were retained due to their high content validity and theoretical importance to their respective constructs. For Model 2, loadings ranged from 0.627 to 0.940, with loadings for TAR and OEA4 below the threshold. However, considering the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs in Model 1 (ranging from 0.591 to 0.738) and Model 2 (ranging from 0.579 to 0.738), all values exceeded 0.50, thus meeting the criteria for convergent validity [93]. Therefore, observed variables with loadings slightly below the threshold were retained in their respective latent constructs. Furthermore, internal consistency reliability was assessed using Dijkstra–Henseler’s rho (), Jöreskog’s rho (, and Cronbach’s Alpha. For Model 1, ranged from 0.869 to 0.899, and ranged from 0.866 to 0.894. Cronbach’s Alpha for Model 1 ranged from 0.864 to 0.893. For Model 2, ranged from 0.887 to 0.909, ranged from 0.876 to 0.904, and Cronbach’s Alpha ranged from 0.879 to 0.904. All these values exceeded 0.70, indicating that the indicators for each construct are consistent and appropriate for measuring their respective latent variables. The results of the measurement model assessment are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Convergent validity.

Furthermore, multicollinearity among indicator variables was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). The VIF values for both Model 1 and Model 2 ranged from 1.431 to 6.219, all falling below the conservative threshold of 10, thereby indicating the absence of substantial multicollinearity concerns among the indicators within each construct [94].

The measurement model assessment also required evaluating discriminant validity, assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT). The HTMT values for Model 1 ranged from 0.745 to 0.837, and for Model 2, they ranged from 0.788 to 0.851. All values were below the threshold of 0.90, indicating that the latent variables for each construct are distinct and that there is no issue of multicollinearity between them [94]. The assessment results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

4.3. Results of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling Analysis

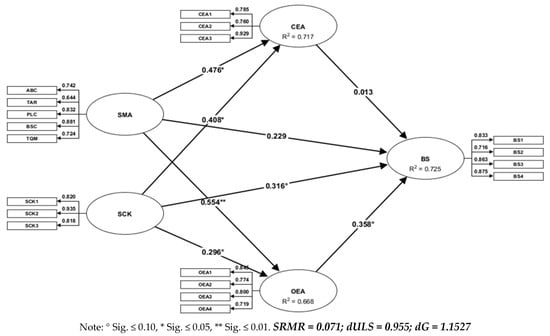

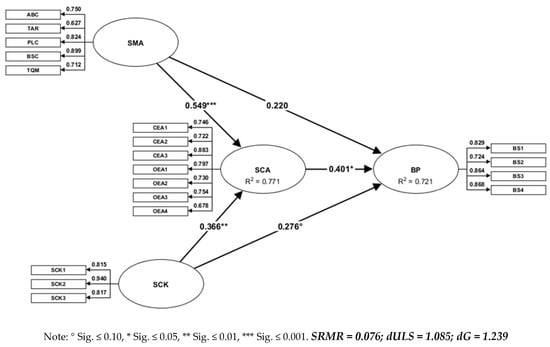

This section presents the results of the hypothesis testing, delineating the direct and indirect effects of Modern Management Accounting (MMA)—comprising Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK)—on the mediating constructs of Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA), both disaggregated (Customer Experience Advantage, CEA, and Operational Efficiency Advantage, OEA) and holistic, and the ultimate endogenous variable, Business Sustainability (BS). The path analysis results for both models clearly demonstrate the pivotal role of MMA capabilities in building a holistic SCA. The structural models with standardized path coefficients for both the disaggregated and holistic approaches are visually presented in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. The path coefficients, along with their statistical significance, effect sizes, and the models’ explanatory power, are summarized in Table 5. The mediation analysis results are presented in Table 6.

Figure 3.

Path analysis of Model 1. (Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Disaggregated Approach).

Figure 4.

Path analysis of Model 2. (Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Holistic Approach).

Table 5.

Path analysis and hypothesis testing tests.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis results.

4.3.1. Assessment of Direct Effects and Model Explanatory Power

The model fit indices for both models indicate acceptable fit. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) values for Model 1 and Model 2 are 0.071 and 0.076, respectively, both below the recommended threshold of 0.08 [96], suggesting good model-data fit.

The analysis of direct effects for Model 1 (Table 5, Panel A) reveals that Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) exerts significant positive effects on both Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) (β = 0.476, p < 0.05) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) (β = 0.554, p < 0.01), supporting H1a and H1b. The effect sizes (f2) for these paths are medium (0.243 and 0.280, respectively) [95]. Similarly, Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) significantly enhances CEA (β = 0.408, p < 0.05) and demonstrates a positive, marginally significant influence on both OEA (β = 0.296, p < 0.10) and Business Sustainability (BS) directly (β = 0.316, p < 0.10), supporting H2a, H2b, and H2c, with effect sizes ranging from small to medium. Crucially, only Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) exhibits a significant direct effect on BS (β = 0.358, p < 0.10; H4 supported), whereas the path from Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) to BS is non-significant (β = 0.013; H3 not supported). The model demonstrates substantial in-sample explanatory power, with R2 values of 0.711 for CEA, 0.667 for OEA, and 0.726 for BS [90]. According to Hair et al. [93], “The R2 measure represents the model’s in-sample explanatory power, while Q2 represents the model’s out-of-sample predictive power. Typically, models with higher R2 values also exhibit higher Q2 values, indicating both good explanatory and predictive capabilities.” Although Q2 values are not reported here, the high R2 values suggest a model with robust explanatory capability.

The path analysis results for Model 1 can be represented by the following system of structural equations, derived from the estimated coefficients:

This yields the following predictive equations for the latent constructs:

Equation (4) quantifies the effects on Business Sustainability (BS), highlighting the dominant role of Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) over Customer Experience Advantage (CEA). The substantial R2 value of 0.726 demonstrates that the disaggregated model has strong explanatory power for BS.

In Model 2 (Table 5, Panel B), which conceptualizes SCA holistically, both SMA (β = 0.549, p < 0.001) and SCK (β = 0.366, p < 0.01) are strong, significant antecedents to the overall SCA construct (H7a and H8a supported), with a large effect size for SMA (f2 = 0.398). The holistic SCA itself is a potent, significant driver of BS (β = 0.401, p < 0.05; H9 supported). The direct effects from SMA and SCK to BS remain non-significant and marginally significant, respectively (H7b not supported, H8b supported). Model 2 exhibits high explanatory power, with an R2 of 0.769 for the mediator (SCA) and 0.721 for the final endogenous variable (BS), both classified as substantial.

The structural model for Model 2 is represented as:

This simplifies to the following predictive equations:

Equation (7) clearly shows the effect of the overall Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) on Business Sustainability (BS), alongside the direct effects of the antecedents. The R2 value of 0.721 for BS indicates the holistic model effectively explains a substantial portion of the variance in the outcome variable.

4.3.2. Assessment of Mediating Effects

The mediation analysis, detailed in Table 6, provides critical insights into the mechanisms through which MMA influences BS. For the disaggregated model (Model 1), the indirect effects were tested to examine the mediating roles of CEA and OEA. Since our PLS software (ADANCO V.2.4.1) did not provide specific indirect effect CIs, we computed them manually by multiplying the bootstrap estimates of path a and path b for each of the 5000 samples, then calculated the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles to derive the bias-corrected confidence intervals (95% BCa CI) [97].

The results indicate that OEA acts as a significant partial mediator in the relationships of both SMA → BS (H5b: β = 0.198, 95% BCa CI [0.001, 0.499]) and SCK → BS (H6b: β = 0.106, 95% BCa CI [−0.043, 0.284]), with Variance Accounted For (VAF) values of 46.37% and 25.19%, respectively, confirming partial mediation. In contrast, CEA does not serve as a significant mediator in either the SMA → BS (H5a) or SCK → BS (H6a) pathways, as evidenced by their CIs encompassing zero and VAF values below 20%.

For the holistic model (Model 2), the overall SCA construct demonstrates a significant mediating role. It fully mediates the relationship between SMA and BS (H10: β = 0.220, 95% BCa CI [0.052, 0.599]; VAF = 50.00%), as the direct effect of SMA on BS (H7b) is non-significant. Furthermore, SCA partially mediates the relationship between SCK and BS (H11: β = 0.147, 95% BCa CI [0.010, 0.351]; VAF = 34.75%), indicating that SCK influences BS both directly and through the building of a holistic competitive advantage.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the role of Modern Management Accounting (MMA), comprising Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK), on Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) and Business Sustainability (BS) in the context of green hotels in Thailand. A comparative analysis of two models was employed: a model utilizing a disaggregated approach to SCA, parsing it into Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) (Model 1), and a model employing a holistic approach, treating SCA as a unified construct (Model 2). The findings reveal significant theoretical and practical insights.

5.1. Discussion of Findings for Model 1 (The Disaggregated Approach)

The analysis for Model 1 reveals a complex pattern of relationships when Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) is disaggregated into Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA). The findings indicate that both Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) serve as significant antecedents to both dimensions of competitive advantage. Specifically, SMA exerts strong positive effects on both CEA (β = 0.476, p < 0.05) and OEA (β = 0.554, p < 0.01), supporting H1a and H1b. Similarly, SCK significantly enhances CEA (β = 0.408, p < 0.05) and demonstrates a positive, marginally significant influence on OEA (β = 0.296, p < 0.10), supporting H2a and H2b. These results align with the theoretical framework proposing that SMA tools such as Activity-Based Costing and Target Costing enhance operational efficiency and cost management [30,33], while SCK enables organizations to design customer experiences that better meet customer needs [24,51].

However, when examining the pathways to Business Sustainability (BS), a critical distinction emerges between the two advantage dimensions. Only Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) demonstrates a significant positive direct effect on BS (β = 0.358, p < 0.10; H4 supported), whereas Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) shows no significant direct effect (β = 0.013, p > 0.10; H3 not supported). This finding suggests that in the context of Thai green hotels, operational efficiency—encompassing cost management, efficient resource utilization, and reliable service delivery—serves as a more immediate and crucial driver of business sustainability compared to investments in distinctive customer experiences.

The mediation analysis provides further insights into these mechanisms. Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) acts as a significant partial mediator in both the relationship between SMA and BS (H5b: β = 0.198, 95% BCa CI [0.001, 0.499]; VAF = 46.37%) and between SCK and BS (H6b: β = 0.106, 95% BCa CI [−0.043, 0.284]; VAF = 25.19%). In contrast, Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) demonstrates no significant mediating role in either the SMA → BS (H5a) or SCK → BS (H6a) pathways, as evidenced by confidence intervals encompassing zero and VAF values below 20%.

This asymmetrical mediating pattern—where OEA transmits the effects of MMA capabilities to sustainability outcomes while CEA does not—highlights a fundamental limitation of the disaggregated approach. Although MMA helps build both types of advantages, only operational efficiency effectively translates these capabilities into sustainable business performance in this model framework. The direct effect of SCK on BS (β = 0.316, p < 0.10; H2c supported) further suggests that customer knowledge contributes to sustainability through pathways beyond the competitive advantage dimensions specified in this disaggregated model.

The substantial R2 values for CEA (0.711), OEA (0.667), and BS (0.726) indicate that the disaggregated model has strong explanatory power. However, the lack of a significant mediating role for CEA and the limited direct effect of CEA on BS reveal a theoretical shortcoming: high explanatory power does not automatically imply a theoretically coherent mediating mechanism. This limitation points toward the necessity of a more integrated conceptualization of competitive advantage, where customer experience and operational efficiency function synergistically rather than as independent pathways to sustainability.

5.2. Discussion of Findings for Model 2 (The Holistic Approach)

The analysis for Model 2, which conceptualizes Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) as a unified construct, reveals a more coherent and theoretically robust pattern of relationships compared to the disaggregated approach. The findings demonstrate that both Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) are strong, significant antecedents to the holistic SCA construct. SMA exhibits a particularly powerful effect (β = 0.549, p < 0.001; H7a supported), while SCK also contributes significantly (β = 0.366, p < 0.01; H8a supported). This provides empirical confirmation that the integrated use of management accounting tools combined with deep customer knowledge constitutes a fundamental capability for building sustainable competitive advantage in green hotels [12,13].

Most importantly, the holistic SCA construct demonstrates a strong, statistically significant direct effect on Business Sustainability (BS) (β = 0.401, p < 0.05; H9 supported). This finding offers robust validation of the Resource-Based View (RBV) theory, confirming that a comprehensively measured sustainable competitive advantage serves as a primary driver of business sustainability [14,16]. The substantial R2 value of 0.769 for SCA indicates that the combination of SMA and SCK is exceptionally effective in forming this unified competitive advantage.

The mediation analysis provides critical insights into the mechanisms through which MMA influences sustainability outcomes. Holistic SCA acts as a significant partial mediator in both relationships: between SMA and BS (H10: β = 0.220, p < 0.10; VAF = 50.00%) and between SCK and BS (H11: β = 0.147, p < 0.10; VAF = 34.75%). This indicates that while both SMA and SCK contribute to BS through the building of holistic competitive advantage, they also operate through additional pathways beyond SCA.

For Strategic Management Accounting, the partial mediation (VAF = 50.00%) suggests that approximately half of SMA’s influence on sustainability occurs through the development of holistic competitive advantage, while the other half may operate through other mechanisms not captured in this model. The non-significant direct path from SMA to BS (H7b not supported) further emphasizes that management accounting practices primarily create value by building foundational capabilities that collectively form competitive advantage.

For Strategic Customer Knowledge, the partial mediation (VAF = 34.75%) combined with the significant direct effect on BS (β = 0.276, p < 0.10; H8b supported) demonstrates that customer knowledge influences business sustainability through multiple pathways: both indirectly through the building of holistic competitive advantage, and directly through its immediate application in strategic decision-making for sustainability.

The explanatory power of Model 2 further validates its theoretical superiority. The R2 value of 0.769 for the mediating construct (SCA) exceeds the substantial threshold (≥0.67), indicating that SMA and SCK collectively provide an exceptionally strong explanation for the formation of holistic competitive advantage. The holistic model provides a more theoretically meaningful explanation by demonstrating a coherent causal chain where both MMA components contribute to an integrated competitive advantage, which in turn drives business sustainability.

5.3. Synthesis and Main Takeaway

The comparative analysis yields a decisive conclusion: the holistic model (Model 2) provides a theoretically and empirically superior framework to the disaggregated model (Model 1). The disaggregated model’s failure to establish significant mediation paths reveals a critical theoretical limitation—isolated advantages (CEA or OEA alone) are insufficient drivers of sustainability. In contrast, the holistic model demonstrates that SCA is most effectively conceptualized as a synergistic Gestalt construct [14,16], where its strong, significant effect on BS and powerful mediating role provide compelling evidence that sustainable performance stems from the orchestration of customer experience and operational efficiency into a unified advantage. Therefore, this research necessitates a paradigm shift from a siloed to a systemic view, demonstrating that the primary mechanism through which MMA enables Business Sustainability is by building this holistic SCA—underscoring that strategic resources create the most value when leveraged to foster synergy, not just standalone capabilities.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

This research yields several significant theoretical contributions that advance the understanding of how internal management capabilities drive sustainability outcomes in the service industry, particularly within the context of green hotels.

6.1.1. The Superiority of the Holistic Model

The most pivotal theoretical contribution of this study lies in its empirical resolution of the conceptual debate regarding the measurement of Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA). The comparative analysis of the disaggregated (Model 1) and holistic (Model 2) models provides compelling evidence for the superiority of the holistic approach. While the disaggregated model demonstrated that Modern Management Accounting (MMA) builds both Customer Experience Advantage (CEA) and Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA), it revealed a critical theoretical flaw: CEA, on its own, did not significantly translate into Business Sustainability (BS), nor did it mediate the MMA-BS relationship. This finding challenges the assumption that distinct advantage dimensions operate as independent pathways to performance. Conversely, the holistic model demonstrated that a unified SCA construct is a potent, significant driver of BS and serves as a robust mediator. This confirms that SCA is a synergistic Gestalt construct [14,16], where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The high explanatory power (R2 = 0.769) for the holistic SCA construct empirically validates that competitive advantage is most meaningfully conceptualized and measured as an integrated capability, fundamentally clarifying a key theoretical ambiguity in the strategic management literature.

6.1.2. SCA as the Key Mediating Mechanism

This study moves beyond establishing direct relationships to delineate the precise causal mechanisms through which MMA influences sustainability. The results provide strong support for a process theory lens. Specifically, the finding that holistic SCA fully mediates the relationship between Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) and BS indicates that the primary value of SMA is not in directly impacting performance but in its role as a foundational enabler for building the integrated competitive capabilities that ultimately drive sustainability. This mediation analysis (H10) clarifies the “black box” between resource deployment and performance outcomes. For Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK), the partial mediation through SCA (H11) suggests a dual pathway: SCK contributes both by building holistic advantage and through its direct application in strategic decision-making for sustainability. This nuanced understanding of mediation mechanisms represents a significant theoretical refinement.

6.1.3. Expanding the Strategic Role of Modern Management Accounting

This study substantively expands the theoretical scope of Management Accounting by empirically linking MMA—conceptualized as an integrated system of SMA and SCK—to non-financial, higher-order strategic outcomes like Business Sustainability. It positions MMA not merely as a tool for cost control and financial reporting but as a strategic, value-creating capability. Grounded in the Resource-Based View (RBV), the study validates that the integrated bundle of SMA practices and SCK processes constitutes a valuable, rare, and difficult-to-imitate resource [20,21]. The strong, significant effects of SMA and SCK on holistic SCA demonstrate that MMA provides the critical informational foundation for building sustainable competitive advantage in the complex and dynamic hotel industry, thereby extending RBV application into a new context.

6.1.4. Empirical Validation of a Synergistic Resource-Based Framework

The study offers robust empirical validation for a synergistic RBV framework. The high R2 values for both the mediator (SCA) and the final outcome (BS) in the holistic model demonstrate a powerful and coherent causal chain: strategic resources (MMA) → core mediating capability (holistic SCA) → strategic performance (BS). This pattern of results not only confirms the model’s strong explanatory power but also empirically underscores a central tenet of strategic management: strategic resources create the most value when they are leveraged to foster synergistic, integrated capabilities rather than standalone ones. This provides a validated framework for future research seeking to understand how internal capabilities translate into sustainable performance in service industries and emerging economies.

6.2. Practical Implications

This study offers practical recommendations for managers and entrepreneurs of green hotels:

6.2.1. Investment in Strategic Management Accounting (SMA) Tools

Management should actively promote and invest in the application of various SMA tools. These include Activity-Based Costing (ABC) to understand the true cost of services, Target Costing to control costs from the design stage, and the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) to measure performance across balanced financial, customer, internal process, and learning perspectives. These tools have been empirically proven to directly build both Operational Efficiency Advantage (OEA) and Customer Experience Advantage (CEA).

6.2.2. Developing Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) Systems

Organizations should develop systematic systems for collecting, analyzing, and utilizing customer data for strategic decision-making. Investments in technologies such as Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems and training employees to effectively gather and leverage customer insights will enhance SCK, which has both direct and indirect effects on BS.

6.2.3. Focus on Building a Holistic Competitive Advantage

Organizational strategy should aim to build an overall SCA by integrating and balancing the development of distinctive customer experiences (CEA) with the enhancement of operational efficiency (OEA) simultaneously. A singular focus on either dimension should be avoided, as the results clearly indicate that only a holistic SCA can effectively translate investments in MMA into achieved sustainability.

6.2.4. Considerations for Small Businesses

For smaller green hotels with limited resources, developing Strategic Customer Knowledge (SCK) may be a more feasible and quicker-returning starting point, as SCK exerts both direct and indirect effects on BS. In contrast, the effect of SMA is fully dependent on building SCA as a mediator.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its significant findings, this study has certain limitations that present opportunities for future research:

6.3.1. Methodological Limitations

This study has several methodological considerations that present opportunities for future research. First, the sample was confined to Thai green hotels, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other cultural contexts or non-certified establishments. Second, the cross-sectional design constrains our ability to capture long-term effects or establish causal directionality between MMA, SCA, and BS. Third, while data were collected across multiple years, the analysis may not fully account for period-specific effects such as COVID-19 recovery. Future research could address these limitations through longitudinal designs, instrumental variable approaches, expanded geographical sampling, and temporal sub-group analyses (e.g., pre-/post-2022) to examine the stability of relationships across different contexts and time periods.

6.3.2. Sample Scope

This study was confined to hotels certified with the Green Hotel standard in Thailand. Future research should expand the scope to include non-certified hotels or other similar service industries (e.g., resorts, hospitals) to test the generalizability of the proposed model in broader contexts.

6.3.3. Incorporating Other Variables

To enhance the predictive power and comprehensiveness of the model, future studies should consider integrating other variables that may influence sustainability, such as business innovation, digital technology adoption, or the role of sustainable leadership.

6.3.4. Examining Moderating Effects

Future research should investigate the role of potential moderating variables on the relationships within this model. Factors such as organizational size (large vs. small), the level of environmental certification (Gold, Silver, Bronze), or the organization’s strategic orientation could be examined to better understand the boundary conditions under which this model is most effective.

By translating these findings into actionable strategies and addressing the identified limitations, future research can contribute to the development of more effective management frameworks and policies. This will ensure that the integration of strategic management accounting and customer knowledge genuinely enhances the long-term resilience and economic and environmental sustainability of green hotels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W. and S.E.; methodology, S.W. and S.E.; validation, S.W. and S.E.; formal analysis, S.W. and S.E.; investigation, S.W. and S.E.; data curation, S.W. and S.E.; writing—original draft preparation, S.W. and S.E.; writing—review and editing, S.W.; visualization, S.W. and S.E.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, S.W.; funding acquisition, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding