Stakeholder Collaboration for Effective ESG Implementation for Forests: Applying the Resource-Based View and Delphi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Resource-Based View (RBV) as a Methodological Framework

2.2. The Delphi Method

2.2.1. Panel Composition

- At least five years of relevant professional experience, ensuring stable, practice-grounded judgments (e.g., policy and program design or implementation, research);

- Current affiliation with organizations actively engaged in practical ESG initiatives for forests in the Republic of Korea;

- Documented participation in cross-sector collaboration (e.g., public–private partnership, NGO-government project), ensuring familiarity with interdependent roles.

2.2.2. Delphi Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Content Analysis (Round 1)

2.3.2. Statistics Analysis (Round 2 and 3)

3. Results

3.1. Stakeholder Resources and Capabilities

3.2. Roles of Governments and NGOs in ESG Implementation

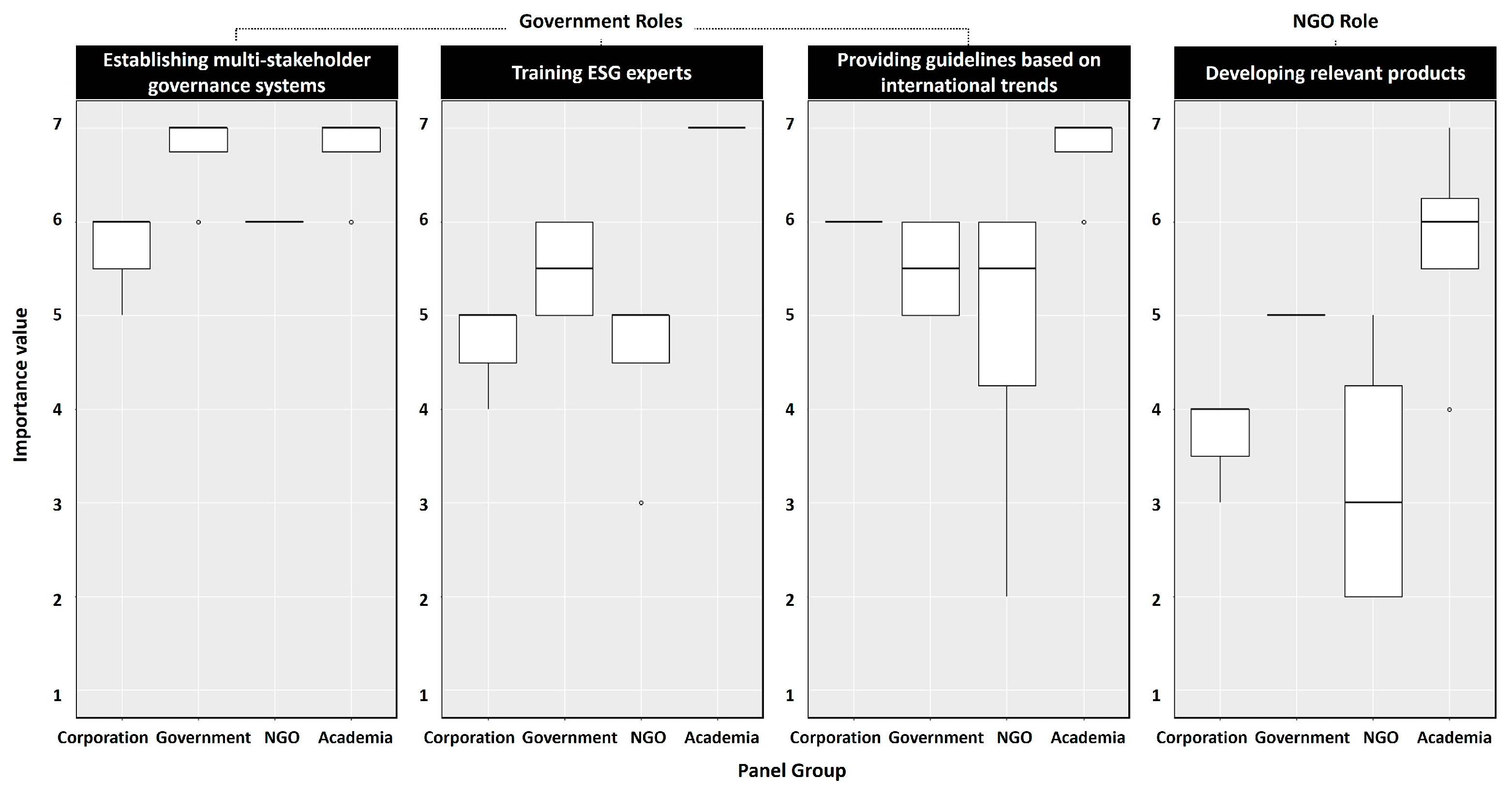

3.3. Comparative Evaluation of Role Importance Across Panel Groups

4. Discussion

4.1. Roles of Stakeholders for ESG Collaboration for Forests

4.2. Strategic Pathways for Effective Cross-Sector Collaboration

4.3. Limitations and Further Research Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, social, and governance |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| RBV | Resource-based view |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Inter-quartile range |

| SMEs | Small and medium-sized businesses |

| EU | European Union |

| US | United States of America |

| TNFD | Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures |

| IPBES | Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services |

Appendix A

| Code | Related Types of Resources/Capabilities | Roles of Governments | Mean | SD | IQR | ||||

| Corporation (n = 3) | Government (n = 4) | NGO (n = 4) | Academia (n = 4) | Overall (n = 15) | |||||

| - | - | All governments roles (aggregate across items) | 5.48 | 5.81 | 5.25 | 6.17 | 5.69 | 1.51 | 2.00 |

| G1 | Physical | Promoting public–private collaboration on available resources (e.g., equipment, seedlings) | 4.33 | 6.75 | 5.25 | 4.75 | 5.33 | 1.70 | 3.00 |

| G2 | Linking project sites | 6.33 | 6.00 | 6.25 | 5.50 | 6.00 | 1.26 | 1.00 | |

| G3 | Financial | Financial support | 2.67 | 4.50 | 4.50 | 6.50 | 4.67 | 1.89 | 3.50 |

| G4 | Technological | Establishing a forest-based ESG model through pilot projects and best-practice cases | 6.33 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 0.61 | 1.00 |

| G5 | Co-developing products | 3.00 | 5.50 | 3.50 | 5.00 | 4.33 | 1.53 | 1.50 | |

| G6 | Conducting relevant R&D | 4.67 | 5.50 | 5.25 | 6.25 | 5.47 | 1.09 | 1.00 | |

| G7 | Organizational | Establishing multi-stakeholder governance systems involving corporations, public institutions, NGOs, and local communities | 6.00 | 6.50 | 6.25 | 6.50 | 6.33 | 0.70 | 1.00 |

| G8 | Implementing and expanding performance measurement systems | 6.33 | 6.25 | 5.50 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |

| G9 | Establishing dedicated organization to increase forest-based ESG activities | 6.00 | 4.50 | 5.25 | 6.25 | 5.47 | 1.15 | 1.00 | |

| G10 | Enhancing coordination between policymaking and implementation divisions | 6.00 | 6.50 | 4.75 | 5.75 | 5.73 | 1.44 | 2.00 | |

| G11 | Human | Training ESG experts | 5.00 | 5.50 | 5.00 | 6.75 | 5.60 | 1.25 | 2.00 |

| G12 | Informational | Providing information on forest-based ESG strategies and practices | 6.33 | 6.00 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 0.73 | 1.00 |

| G13 | Providing forest-based ESG information tailored to the domestic context | 6.33 | 6.00 | 5.75 | 6.25 | 6.07 | 0.68 | 0.50 | |

| G14 | Providing guidelines based on international trends | 6.00 | 6.25 | 4.50 | 6.75 | 5.87 | 1.26 | 1.50 | |

| G15 | Collecting data | 5.67 | 5.75 | 5.75 | 6.25 | 5.87 | 1.20 | 2.00 | |

| G16 | Sharing scientific data and information for forest-based ESG activities | 5.00 | 6.25 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 5.80 | 0.98 | 0.50 | |

| G17 | Establishing a platform for information sharing | 6.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 5.47 | 1.20 | 1.00 | |

| G18 | Reputational | Expanding inter-ministerial collaboration | 5.33 | 6.00 | 5.25 | 6.75 | 5.87 | 1.26 | 2.50 |

| G19 | Providing promotion and consultancy services to corporations | 4.33 | 5.25 | 4.00 | 6.50 | 5.07 | 1.65 | 2.00 | |

| G20 | Raising public awareness to improve societal accessibility to ESG activities | 6.33 | 6.00 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 0.73 | 1.00 | |

| G21 | Institutional | Establishing legal and institutional foundations | 7.00 | 5.75 | 5.50 | 6.50 | 6.13 | 1.02 | 1.00 |

| Code | Related Types of Resources/Capabilities | Roles of NGOs | Mean | SD | IQR | ||||

| Corporation (n = 3) | Government (n = 4) | NGO (n = 4) | Academia (n = 4) | Overall | |||||

| All NGOs roles (aggregate across items) | 5.70 | 5.90 | 5.30 | 6.18 | 5.77 | 1.12 | 2.00 | ||

| N1 | Financial | Providing financial support through voluntary fundraising | 4.67 | 5.25 | 5.00 | 5.25 | 5.07 | 1.39 | 2.00 |

| N2 | Operating forest-related funds | 4.67 | 5.75 | 4.75 | 5.50 | 5.20 | 1.22 | 2.00 | |

| N3 | Technological | Utilizing field-based technologies | 5.67 | 6.25 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 5.93 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| N4 | Carrying out sustainable management | 4.33 | 5.50 | 4.00 | 5.25 | 4.80 | 1.33 | 2.00 | |

| N5 | Conducting continuous monitoring | 6.00 | 6.00 | 5.75 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 0.89 | 1.50 | |

| N6 | Conducting relevant R&D | 5.00 | 5.50 | 5.25 | 6.50 | 5.60 | 0.88 | 1.00 | |

| N7 | Enhancing capacity to implement region-specific ESG activities | 6.00 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 6.33 | 0.70 | 1.00 | |

| N8 | Developing relevant products | 4.00 | 5.75 | 3.75 | 5.50 | 4.80 | 1.38 | 2.00 | |

| N9 | Organizational | Building local community-based initiatives | 6.00 | 6.50 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 6.07 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| N10 | Acting as an intermediary between corporations and governments | 6.33 | 6.25 | 4.50 | 6.00 | 5.73 | 1.44 | 1.00 | |

| N11 | Human | Providing participatory opportunities for diverse stakeholders, including local residents | 6.67 | 5.75 | 5.50 | 6.75 | 6.13 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| N12 | Strengthening educational capacity | 6.33 | 5.50 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 5.93 | 1.00 | 0.50 | |

| N13 | Informational | Developing and proposing forest-based ESG programs that integrate environmental and social objectives | 6.67 | 6.25 | 5.75 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| N14 | Providing expert knowledge related to forest management and ESG | 5.00 | 6.00 | 5.25 | 5.75 | 5.53 | 1.02 | 1.00 | |

| N15 | Facilitating communication aligned with global ESG trends and directions | 5.67 | 5.75 | 5.75 | 5.75 | 5.73 | 0.77 | 1.00 | |

| N16 | Collecting data from field-level ESG activities | 6.67 | 6.25 | 5.75 | 6.50 | 6.27 | 0.93 | 1.00 | |

| N17 | Reputational | Raising public awareness | 6.33 | 5.75 | 5.00 | 6.00 | 5.73 | 0.85 | 0.50 |

| N18 | Participating in joint initiatives to prevent greenwashing | 6.33 | 5.75 | 5.00 | 6.75 | 5.93 | 1.00 | 1.50 | |

| N19 | Engaging in dialogue based on long-standing relationships with the public (consumers) | 5.67 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 6.13 | 1.02 | 1.00 | |

| N20 | Institutional | Proposing policies that support complementary forest-based ESG activities | 6.00 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 6.75 | 6.13 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| Code | Related Types of Resources/Capabilities | Roles of Governments | Mean | SD | IQR | ||||

| Corporation (n = 3) | Government (n = 4) | NGO (n = 4) | Academia (n = 4) | Overall (n = 15) | |||||

| All governments roles (aggregate across items) | 5.51 | 5.63 | 5.08 | 6.19 | 5.64 | 1.21 | 1.00 | ||

| G1 | Physical | Promoting public–private collaboration on available resources (e.g., equipment, seedlings) | 4.67 | 5.07 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.07 | 1.44 | 1.50 |

| G2 | Linking project sites | 6.33 | 6.00 | 5.25 | 5.75 | 5.80 | 0.98 | 0.00 | |

| G3 | Financial | Financial support | 2.33 | 4.07 | 3.75 | 5.75 | 4.07 | 1.81 | 2.00 |

| G4 | Technological | Establishing a forest-based ESG model through pilot projects and best-practice cases | 6.67 | 6.75 | 5.75 | 6.75 | 6.47 | 0.62 | 1.00 |

| G5 | Co-developing products | 3.67 | 4.33 | 3.25 | 5.00 | 4.33 | 1.30 | 1.50 | |

| G6 | Conducting relevant R&D | 5.00 | 5.53 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 5.53 | 0.88 | 1.00 | |

| G7 | Organizational | Establishing multi-stakeholder governance systems involving corporations, public institutions, NGOs, and local communities | 5.67 | 6.33 | 6.00 | 6.75 | 6.33 | 0.60 | 1.00 |

| G8 | Implementing and expanding performance measurement systems | 6.33 | 6.07 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 6.07 | 0.57 | 0.00 | |

| G9 | Establishing dedicated organization to increase forest-based ESG activities | 6.00 | 5.33 | 4.75 | 6.25 | 5.33 | 1.19 | 1.50 | |

| G10 | Enhancing coordination between policymaking and implementation divisions | 5.67 | 5.73 | 4.75 | 6.00 | 5.73 | 1.29 | 2.00 | |

| G11 | Human | Training ESG experts | 4.67 | 5.50 | 4.50 | 7.00 | 5.47 | 1.15 | 1.50 |

| G12 | Informational | Providing information on forest-based ESG strategies and practices | 6.33 | 6.20 | 5.75 | 6.50 | 6.20 | 0.65 | 1.00 |

| G13 | Providing forest-based ESG information tailored to the domestic context | 6.33 | 6.13 | 5.75 | 6.25 | 6.13 | 0.72 | 1.00 | |

| G14 | Providing guidelines based on international trends | 6.00 | 5.73 | 4.75 | 6.75 | 5.73 | 1.18 | 0.50 | |

| G15 | Collecting data | 6.00 | 5.75 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 5.87 | 0.62 | 0.50 | |

| G16 | Sharing scientific data and information for forest-based ESG activities | 5.67 | 5.93 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 5.93 | 0.57 | 0.00 | |

| G17 | Establishing a platform for information sharing | 5.67 | 5.00 | 4.50 | 6.25 | 5.33 | 1.19 | 1.00 | |

| G18 | Reputational | Expanding inter-ministerial collaboration | 5.33 | 6.00 | 5.00 | 6.75 | 5.80 | 1.28 | 2.00 |

| G19 | Providing promotion and consultancy services to corporations | 4.33 | 4.87 | 3.75 | 6.00 | 4.87 | 1.26 | 2.00 | |

| G20 | Raising public awareness to improve societal accessibility to ESG activities | 6.33 | 6.07 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 6.07 | 0.68 | 0.50 | |

| G21 | Institutional | Establishing legal and institutional foundations | 6.67 | 5.75 | 6.00 | 6.75 | 6.27 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| Code | Related Types of Resources/Capabilities | Roles of NGOs | Mean | SD | IQR | ||||

| Corporation (n = 3) | Government (n = 4) | NGO (n = 4) | Academia (n = 4) | Overall | |||||

| All NGOs roles (aggregate across items) | 5.77 | 5.73 | 5.29 | 6.05 | 5.68 | 1.14 | 1.00 | ||

| N1 | Financial | Providing financial support through voluntary fundraising | 4.67 | 4.75 | 4.75 | 4.75 | 4.73 | 1.24 | 1.50 |

| N2 | Operating forest-related funds | 4.67 | 5.00 | 4.75 | 5.25 | 5.00 | 1.10 | 1.50 | |

| N3 | Technological | Utilizing field-based technologies | 5.67 | 6.07 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 6.07 | 0.68 | 0.50 |

| N4 | Carrying out sustainable management | 4.33 | 5.00 | 3.50 | 4.00 | 4.20 | 1.42 | 2.00 | |

| N5 | Conducting continuous monitoring | 6.67 | 6.00 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 0.82 | 0.50 | |

| N6 | Conducting relevant R&D | 5.00 | 5.53 | 5.25 | 6.50 | 5.53 | 0.88 | 1.00 | |

| N7 | Enhancing capacity to implement region-specific ESG activities | 6.33 | 6.27 | 5.75 | 7.00 | 6.27 | 0.68 | 1.00 | |

| N8 | Developing relevant products | 3.67 | 4.47 | 3.25 | 5.75 | 4.47 | 1.36 | 1.00 | |

| N9 | Organizational | Building local community-based initiatives | 6.00 | 6.13 | 5.50 | 6.75 | 6.13 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| N10 | Acting as an intermediary between corporations and governments | 6.33 | 5.75 | 4.25 | 6.00 | 5.53 | 1.36 | 1.00 | |

| N11 | Human | Providing participatory opportunities for diverse stakeholders, including local residents | 6.67 | 6.13 | 5.50 | 6.75 | 6.13 | 0.88 | 1.00 |

| N12 | Strengthening educational capacity | 6.33 | 5.87 | 5.50 | 6.25 | 5.87 | 0.96 | 0.00 | |

| N13 | Informational | Developing and proposing forest-based ESG programs that integrate environmental and social objectives | 6.67 | 6.40 | 6.00 | 7.00 | 6.40 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| N14 | Providing expert knowledge related to forest management and ESG | 5.00 | 5.53 | 5.75 | 5.75 | 5.53 | 0.72 | 1.00 | |

| N15 | Facilitating communication aligned with global ESG trends and directions | 5.67 | 5.87 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 5.87 | 0.72 | 1.00 | |

| N16 | Collecting data from field-level ESG activities | 6.67 | 6.20 | 5.50 | 6.50 | 6.20 | 0.91 | 1.00 | |

| N17 | Reputational | Raising public awareness | 6.33 | 5.67 | 5.75 | 5.00 | 5.67 | 1.19 | 0.00 |

| N18 | Participating in joint initiatives to prevent greenwashing | 6.33 | 5.75 | 5.00 | 6.50 | 5.87 | 0.96 | 1.00 | |

| N19 | Engaging in dialogue based on long-standing relationships with the public (consumers) | 6.00 | 6.07 | 6.25 | 6.00 | 6.07 | 0.68 | 0.50 | |

| N20 | Institutional | Proposing policies that support complementary forest-based ESG activities | 6.33 | 6.13 | 6.00 | 6.50 | 6.13 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

References

- Adler, R.; Mansi, M.; Pandey, R. Biodiversity and threatened species reporting by the top Fortune Global companies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 787–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, T.; Wübbels, G.; Portafaix, A.; Meyer zum Felde, A.; Zielcke, S. The Biodiversity Crisis Is a Business Crisis; Boston Consulting Group: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar, R.; Ober, H.; Pinkse, J. The uncomfortable relationship between business and biodiversity: Advancing research on business strategies for biodiversity protection. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2554–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakes, E.H.; Dalin, C.; Etard, A.; Newbold, T. Impacts of the global food system on terrestrial biodiversity from land use and climate change. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Tilman, D.; Jin, Z.; Smith, P.; Barrett, C.B.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Burney, J.; D’oDorico, P.; Fantke, P.; Fargione, J.; et al. Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science 2024, 385, eadn3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.M.; Kuo, T.C.; Chen, J.L. Impacts on the ESG and financial performances of companies in the manufacturing industry based on the climate change related risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M.F.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Homayoun, S. Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R.; Gupta, S.; Tiwari, A.K. Environmental, social and governance-type investing: A multi-stakeholder machine learning analysis. Manag. Decis. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Plas, F.; Ratcliffe, S.; Ruiz-Benito, P.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Verheyen, K.; Wirth, C.; Zavala, M.A.; Ampoorter, E.; Baeten, L.; Barbaro, L.; et al. Continental mapping of forest ecosystem functions reveals a high but unrealised potential for forest multifunctionality. Ecol. Lett. 2018, 21, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teben’kOva, D.N.; Lukina, N.V.; Chumachenko, S.I.; Danilova, M.A.; Kuznetsova, A.I.; Gornov, A.V.; Shevchenko, N.E.; Kataev, A.D.; Gagarin, Y.N. Multifunctionality and biodiversity of forest ecosystems. Contemp. Probl. Ecol. 2020, 13, 709–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, W.; Molitor, D.; Raghupathi, V.; Saharia, A. Identifying Key Issues in Climate Change Litigation: A Machine Learning Text Analytic Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockerhoff, E.G.; Barbaro, L.; Castagneyrol, B.; Forrester, D.I.; Gardiner, B.; González-Olabarria, J.R.; Lyver, P.O.; Meurisse, N.; Oxbrough, A.; Taki, H.; et al. Forest biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 3005–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, S.; Bayne, K.M.; Yao, R.T.; Payn, T. Credence attributes in the forestry sector and the role of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Forests 2022, 13, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadly, M.R. Advancing Forest Accounting as a Tool for Legal Frameworks in Sustainable Resource Management: Implications for ESG Compliance in Indonesia. Lit. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 2, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ayassamy, P. The relationship between biodiversity, circular economy, and institutional investors in the sustainable transition: A mixed review. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 3171–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.B.; Bromwich, T.; Bang, A.; Bennun, L.; Bull, J.; Clark, M.; Milner-Gulland, E.; Prescott, G.W.; Starkey, M.; zu Ermgassen, S.O.; et al. The “nature-positive” journey for business: A conceptual research agenda to guide contributions to societal biodiversity goals. One Earth 2024, 7, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.M.; Roberts, L.; Atkins, J. Exploring factors relating to extinction disclosures: What motivates companies to report on biodiversity and species protection? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1419–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Chang, C.Y. Desirable Forest Futures from Stakeholders and Policy Priority. Korean For. Econ. Res. 2022, 29, 131–147. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, Y.; Lee, J.; Senadheera, S.S.; Chang, S.X.; Rinklebe, J.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Biodiversity conservation activities for nature-positive goals: Cases of Korean companies. Sustain. Environ. 2024, 10, 2426832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.K. Analysis of Forest-related Activities in the ESG Management of Korean Companies Using News Big Data. Korean For. Econ. Res. 2024, 31, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.K.; Yun, H.Y.; Kang, K.Y. Utilization and Challenges of Forest Carbon Sinks in the ESG Management of Korean Companies. Korean For. Econ. Res. 2023, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Meng, Q. Why greenwashing occurs and what happens afterwards? A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 118102–118116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneideriene, A.; Legenzova, R. Greenwashing prevention in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures: A bibliometric analysis. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainey, H.J.; Pollard, E.H.; Dutson, G.; Ekstrom, J.M.; Livingstone, S.R.; Temple, H.J.; Pilgrim, J.D. A review of corporate goals of no net loss and net positive impact on biodiversity. Oryx 2015, 49, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macellari, M.; Gusmerotti, N.M.; Frey, M.; Testa, F. Embedding biodiversity and ecosystem services in corporate sustainability: A strategy to enable sustainable development goals. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2018, 1, 244–255. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M. Business, biodiversity and ecosystem services: Evidence from large-scale survey data. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2583–2599. [Google Scholar]

- Weinhofer, G.; Hoffmann, V.H. Mitigating climate change—How do corporate strategies differ? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suneetha, M.S. Sustainability issues for biodiversity business. Sustain. Sci. 2010, 5, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S. A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, G.T.; Bunn, M.D.; Gray, B.; Xiao, Q.; Wang, S.; Wilson, E.J.; Williams, E.S. Stakeholder collaboration: Implications for stakeholder theory and practice. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96 (Suppl. S1), 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Olausson, M. Drivers and Barriers for Integrating ESG Metrics in Swedish Commercial Property Valuation: Towards a Deeper Understanding of ESG in Valuation Practice; Linköping University: Linköping, Sweden, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.S.; Bosse, D.A.; Phillips, R.A. Managing for stakeholders, stakeholder utility functions, and competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2010, 31, 58–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tantalo, C.; Priem, R.L. Value creation through stakeholder synergy. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhani, P.M. Resource based view (RBV) of competitive advantage: An overview. In Resource Based View: Concepts and Practices; Icfai University Press: Hyderabad, India, 2010; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bozeman, B.; Straussman, J. Public Management Strategies; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, R.M. The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 33, 114–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.Y.; Chen, L.W.; Shen, C.L.; Liu, C.C. Measuring the core competencies of service businesses: A resource-based view. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual SRII Global Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 29 March–2 April 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 222–231. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.Y.; Whitford, A.B. Assessing the effects of organizational resources on public agency performance: Evidence from the US federal government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2013, 23, 687–712. [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, J.H.; Singh, H. The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 660–679. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E.; Dmytriyev, S.D.; Phillips, R.A. Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korea Forest Service. Forest Area and Timber Stock by Year. Forest Statistical System. 2020. Available online: https://kfss.forest.go.kr/stat/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Choi, D.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. An economic analysis of corporate social responsibility in Korea. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Cho, J.H. The effect of ESG performance on tax avoidance—Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. A resource-based view of the firm. Strateg. Manag. J. 1984, 5, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Schoemaker, P.J. Strategic assets and Organizational rent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 13, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. (Eds.) The Delphi Method; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 1975, pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: Issues and analysis. Int. J. Forecast. 1999, 15, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Der Gracht, H.A. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2012, 79, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, D.H.; Moon, H.; Shin, H.; Ahn, Y. Critical Risk Factors of Stakeholder Collaboration Impacting BIM Implementtion in High-Rise Residential Building Projects Under the DBB System: A Delphi Survey. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2024, 2024, 9888982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilasmana, G.B.; Fadli, M.; Efani, A.; Prianti, D.D.; Putra, N. Analysis of key Factors in Collaborative Governance Models Between Navy and Maritime Industry using Delphi-Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM). J. Marit. Res. 2025, 22, 290–301. [Google Scholar]

- Skulmoski, G.J.; Hartman, F.T.; Krahn, J. The Delphi method for graduate research. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2007, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avella, J.R. Delphi panels: Research design, procedures, advantages, and challenges. Int. J. Dr. Stud. 2016, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoli, C.; Pawlowski, S.D. The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Inf. Manag. 2004, 42, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink-Hafner, D.; Dagen, T.; Doušak, M.; Novak, M.; Hafner-Fink, M. Delphi method: Strengths and weaknesses. Adv. Methodol. Stat. 2019, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Content Analysis. 2000. Available online: https://www.qualitative-resaech.net/fgs-texte/2-00/2-00mayring-e.htm (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, L.M. Cronbach’s alpha. Medsurg Nurs. 2011, 20, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, I.R.; Grant, R.C.; Feldman, B.M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Ling, S.C.; Moore, A.M.; Wales, P.W. Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKight, P.E.; Najab, J. Kruskal-wallis test. Corsini Encycl. Psychol. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Ahmadov, T.; Ulp, S.; Gerstlberger, W. Role of stakeholder engagement in sustainable development in Estonian small and medium-sized enterprises. Green Low-Carbon Econ. 2024, 2, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andréasson, H. Business & Biodiversity—How Businesses Understand and Work with Biodiversity; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Addison, P.F.; Bull, J.W.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Using conservation science to advance corporate biodiversity accountability. Conserv. Biol. 2019, 33, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffo, R.; Marshall, C.; Patalano, R. ESG investing: Environmental pillar scoring and reporting. Retrived 2020, 14, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, U.H.; Dow, K.E. Stakeholder theory: A deliberative perspective. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Song, J.-S.J.; Yin, H.; Zhu, Q. NGOs’ Network Intelligence Strategy for ESG Enhancement in SMEs. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4722937 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Wirba, A.V. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of government in promoting CSR. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 7428–7454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implica-tions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bonetti, L.; Lai, A.; Stacchezzini, R. Stakeholder engagement in the public utility sector: Evidence from Italian ESG reports. Util. Policy 2023, 84, 101649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, J.; Siu, M.; Orengo, A.; Kasiri, N. An analysis of environmental sustainability in small & medium-sized enterprises: Patterns and trends. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Bowley, T.; Hill, J.G. The global ESG stewardship ecosystem. Eur. Bus. Organ. Law Rev. 2024, 25, 229–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, T.; Ward, H.; Howard, B. Public Sector Roles in Strengthening Corporate Social Responsibility: A Baseline Study; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, N.; Scanlan, S.J.; Smith, P.; Smith, T.; Aronczyk, M.; Hill, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Montgomery, A.W.; Tubiello, F.N.; Stabinsky, D. An integrated framework to assess greenwashing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, J. Biodiversity loss as material risk: Tracking the changing meanings and materialities of biodiversity conservation. Geoforum 2013, 45, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elijido-Ten, E.O.; Clarkson, P. Going beyond climate change risk management: Insights from the world’s largest most sustainable corporations. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 1067–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, W.; Liang, F.; Wang, Z. The impact of climate change on corporate ESG performance: The role of resource misallocation in enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 445, 141263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, V.; Jonäll, K.; Paananen, M.; Bebbington, J.; Michelon, G. Biodiversity reporting: Standardization, materiality, and assurance. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2024, 68, 101435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambooy, T.E.; Maas, K.E.H.; van ‘t Foort, S.; Van Tilburg, R. Biodiversity and natural capital: Investor influence on company reporting and performance. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2018, 8, 158–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.G. Relationship Between Environmental Social Governance (ESG) Management and Performance—The Role of Collaboration in the Supply Chain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.M.; Cho, D.H.; Ryu, D.H.; Choi, J.H.; An, K.W. Domestic and foreign ESG trends and strategies for developing ESG evaluation model in forest sector. Korean J. For. Econ. 2022, 29, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V. Sustainability and stakeholder theory: A processual perspective. Kybernetes 2023, 52, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaohui, P. Exploring the synergistic effect of ESG-driven environmental policies and the cross-regional linkage mechanism. Acad. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2025, 7, 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Eden, C.; Huxham, C. The negotiation of purpose in multi-organizational collaborative groups. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Mitchell, W. Growth dynamics: The bidirectional relationship between interfirm collaboration and business sales in entrant and incumbent alliances. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 497–521. [Google Scholar]

- Nonet, G.A.H.; Gössling, T.; Van Tulder, R.; Bryson, J.M. Multi-stakeholder engagement for the sustainable development goals: Introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 180, 945–957. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Burg, S.W.K.; Bogaardt, M.J. Business and biodiversity: A frame analysis. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 8, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, R.; Bingham, L.B. Conclusion: Conflict and collaboration in networks. Int. Public Manag. J. 2007, 10, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipel, K.W.; Walker, S.B. Conflict analysis in environmental management. Environmetrics 2011, 22, 279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Von Essen, E.; Hansen, H.P. How stakeholder co-management reproduces conservation conflicts: Revealing rationality problems in Swedish wolf conservation. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Stutzman, H.; Vedoveto, M.; Delgado, D.; Rivero, R.; Dariquebe, W.Q.; Contreras, L.S.; Souto, T.; Harden, A.; Rhee, S. Collaborative governance and conflict management: Lessons learned and good practices from a case study in the Amazon Basin. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2020, 33, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. How does government support promote the relationship between ESG performance and innovation? J. Innov. Dev. 2023, 3, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Quirós, M.M.; Miralles-Quirós, J.L.; Redondo Hernández, J. ESG performance and shareholder value creation in the banking industry: International differences. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilyay-Erdogan, S. Corporate ESG engagement and information asymmetry: The moderating role of country-level institutional differences. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2022, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhania, M.; Saini, N.; Shri, C.; Bhatia, S. Cross-country comparative trend analysis in ESG regulatory framework across developed and developing nations. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024, 35, 61–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbrandsen, L.H. Overlapping public and private governance: Can forest certification fill the gaps in the global forest regime? Glob. Environ. Politics 2004, 4, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Yu, J. Striving for sustainable development: Green financial policy, institutional investors, and corporate ESG performance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1177–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cifuentes-Faura, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, L. The impact of government environmental attention on firms’ ESG performance: Evidence from China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2024, 67, 102124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lööf, H.; Sahamkhadam, M.; Stephan, A. Incorporating ESG into optimal stock portfolios for the global timber & forestry industry. J. For. Econ. 2023, 38, 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Resources/Capabilities | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Tangible | Physical | Assets that organizations own or control (e.g., land, facilities) and can be directly or indirectly utilized to advance forest-related ESG initiatives. |

| Financial | Monetary resources and financing instruments that can be allocated to implement ESG for forests. | |

| Technological | Codified knowledge and tools that enhance the effectiveness or scalability of forest-focused ESG implementation (e.g., patents, know-how, research, and process technologies). | |

| Organizational | Formal structures, routines, and cultural norms that coordinate actors and integrate resources for implementing ESG goals for forests. | |

| Intangible | Human | Organizational actors’ knowledge, skills, and experience—individually or collectively—mobilized to design and execute ESG actions for forests. |

| Informational | Databases, analytics tools, and information management processes that support evidence-based decision making for forest ESG implementation. | |

| Reputational | Legitimacy assets that strengthen credibility and facilitate collaboration for forest ESG implementation (e.g., reputation, trustworthiness, relationship). | |

| Institutional | Institutional framework that authorizes and provides access to resources for forest ESG implementation (e.g., laws, permits, policy programs). | |

| Mean | SD | IQR | Round 2 | Round 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <4.0 | - | - | Delete | Delete |

| >4.0 | ≥1.0 | >1.0 | Re-evaluate with feedback | Delete |

| >4.0 | <1.0 | >1.0 | Re-evaluate with feedback | Delete |

| >4.0 | ≥1.0 | ≤1.0 | Re-evaluate with feedback | Delete |

| >4.0 | <1.0 | ≤1.0 | Confirm inclusion | Consensus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Kim, J. Stakeholder Collaboration for Effective ESG Implementation for Forests: Applying the Resource-Based View and Delphi. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8930. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198930

Kim D, Kim J. Stakeholder Collaboration for Effective ESG Implementation for Forests: Applying the Resource-Based View and Delphi. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8930. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198930

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Donghee, and Jaehyun Kim. 2025. "Stakeholder Collaboration for Effective ESG Implementation for Forests: Applying the Resource-Based View and Delphi" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8930. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198930

APA StyleKim, D., & Kim, J. (2025). Stakeholder Collaboration for Effective ESG Implementation for Forests: Applying the Resource-Based View and Delphi. Sustainability, 17(19), 8930. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198930