AI-Driven Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Tourism and Hospitality: Mediating Roles of Digital Culture and Skills

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

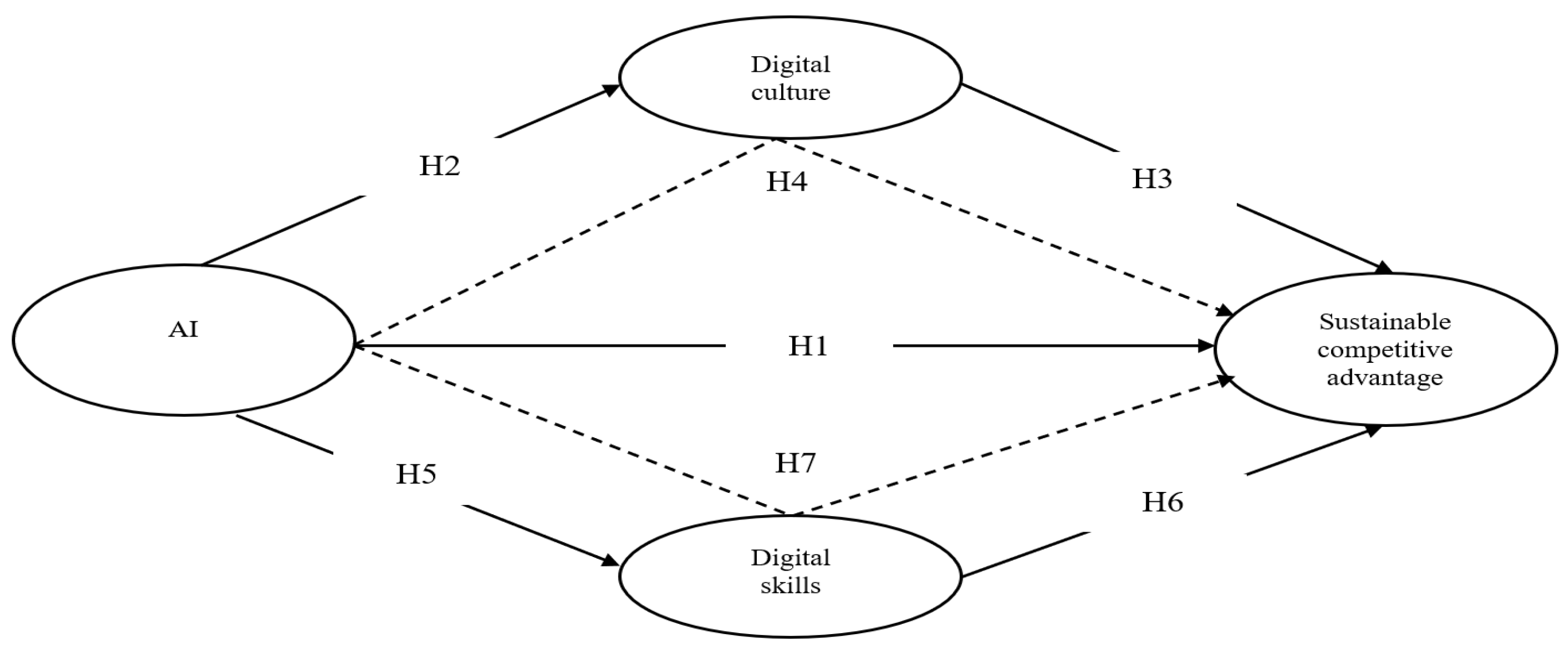

2.1. The Effect of AI on Sustainable Competitive Advantage

2.2. The Effect of AI on Digital Culture

2.3. The Effect of Digital Culture on Sustainable Competitive Advantage

2.4. The Mediating Role of Digital Culture

2.5. The Effect of AI on Digital Skills

2.6. The Effect of Digital Skills on Sustainable Competitive Advantage

2.7. The Mediating Role of Digital Skills

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Common Method Bias

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structure Model

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical Implications

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Population and Sample Distribution by Subsector and Region (N = 488)

| Region | 5★ Hotels (Institutions) | 5★ Hotels (Respondents) | Travel Agencies (Institutions) | Travel Agencies (Respondents) | DMCs (Institutions) | DMCs (Respondents) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Riyadh | 34 | 60 | 68 | 59 | 25 | 35 |

| Jeddah | 20 | 35 | 48 | 41 | 26 | 36 |

| Makkah | 21 | 37 | 34 | 29 | 13 | 18 |

| Madinah | 20 | 36 | 17 | 15 | 15 | 21 |

| Eastern Province | 16 | 28 | 39 | 34 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 111 | 196 | 206 | 178 | 82 | 114 |

References

- Ruel, H.; Njoku, E. AI redefining the hospitality industry. J. Tour. Futures 2021, 7, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wodecki, A.; Wodecki, H.; Harrison, L. Artificial Intelligence in Value Creation; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Khan, T.; Şener, İ. Transforming hospitality: The dynamics of AI integration, customer satisfaction, and organizational readiness in enhancing firm performance. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.; Dias, J. How has data-driven marketing evolved: Challenges and opportunities with emerging technologies. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2023, 3, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.; Anderie, L. Digital Business Management: Transforming to a Data-Driven Organization Using AI; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Leal-Rodríguez, A.; Sanchís-Pedregosa, C.; Moreno-Moreno, A.; Leal-Millán, A. Digitalization beyond technology: Proposing an explanatory and predictive model for digital culture in organizations. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonamah, A.; Abdelhamid, N. Managerial insights for AI/ML implementation: A playbook for successful organizational integration. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2024, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, D.; Leung, J.; Su, J.; Ng, R.; Chu, S. Teachers’ AI digital competencies and twenty-first century skills in the post-pandemic world. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 137–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, E. Applications of Artificial Intelligence as a Marketing Tool and Their Impact on the Competitiveness of the Egyptian Tourist Destination. Ph.D. Thesis, Minia University, Minya Governorate, Egypt, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Probojakti, W.; Utami, H.; Prasetya, A.; Riza, M. Driving sustainable competitive advantage in banking: The role of transformational leadership and digital transformation in organizational agility and corporate resiliency. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 670–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toros, E.; Asiksoy, G.; Sürücü, L. Refreshment students’ perceived usefulness and attitudes towards using technology: A moderated mediation model. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah Alam, S.; Ahsan, M.N.; Masukujjaman, M.; Kokash, H.; Ahmed, S. Adoption of Big Data Analytics and Artificial Intelligence Among Hospitality and Tourism Companies: Perceive Performance Perspective. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2024, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, E.; Chen, C. Artificial intelligence innovation of tourism businesses: From satisfied tourists to continued service usage intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D. Aesthetic value evaluation for digital cultural and creative products with artificial intelligence. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 1, 8318620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Zhou, E. Unpacking the Reasons Shaping Employee Acceptance and Attitudes towards AI Assistant Services in the Hotel Industry: A Behavioral Reasoning Perspective. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2024, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Massimo, D.; Berezina, K. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2023. In Proceedings of the ENTER 2023 eTourism Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa, 18–20 January 2023; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Saudi Arabia’s Governance. J. Dev. Soc. 2024, 40, 500–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, I.; Hina, K.; Malik, W.; Arslan, M. Tourism, identity, and Vision 2030: A neonationalist analysis of Red Sea Global’s impact on Saudi Arabia’s future. Migr. Lett. 2024, 21, 257–271. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B.; Alharethi, T. Unlocking sustainable competitive advantage: The catalytic role of digital talent and knowledge workers in digital leadership in tourism and hospitality industry. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 10395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, P.; Wilson, H. Human+ Machine, Updated and Expanded: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Emran, M. Beyond technology acceptance: Development and evaluation of technology-environmental, economic, and social sustainability theory. Technol. Soc. 2023, 75, 102383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikshat, V.; Kumar, S.; Patel, P.; Varma, A. Impact of organisational facilitators and perceived HR effectiveness on acceptance of AI-augmented HRM: An integrated TAM and TPB perspective. Pers. Rev. 2025, 54, 879–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Cha, M.; Yoon, S.; Lee, S. Not merely useful but also amusing: Impact of perceived usefulness and perceived enjoyment on the adoption of AI-powered coding assistant. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 6210–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Nawaz, F.; Sabir, R. To Gain Sustainable Competitive Advantages (SCA) Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) Over Competitors. Bull. Bus. Econ. (BBE) 2024, 13, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehzadeh, R.; Javani, M.; Esmailian, H. Leveraging green artificial intelligence for green competitive advantage: Testing a mediated moderation model. TQM J. 2024. ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeraati, P. The impact of organizational learning on sustainable competitive advantage about the mediating role of cultural intelligence and artificial intelligence adoption. J. Ind. Syst. Eng. 2025, 17, 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B. HRM and Digital Leadership: Exploring the Mediating Role of Digital Talent and Digital Culture in Driving Innovative Performance in Saudi Arabia’s Tourism and Hospitality Industry. In HRM, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work: Insights from the Global South; Adekoya, O.D., Mordi, C., Ajonbadi, H.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 101–123. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yu, L.; Zhang, T.; Zang, C.; Cui, P.; Song, C.; Zhu, W. Exploring the collective human behavior in cascading systems: A comprehensive framework. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2020, 62, 4599–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M.; Rana, M.; Amin, M.; Sony, M.; Rahaman, M.; Fenyves, V. Examining the Role of AI-Augmented HRM for Sustainable Performance: Key Determinants for Digital Culture and Organizational Strategy. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Lin, J.; Luo, X. The impact of human ai skills on organizational innovation: The moderating role of digital organizational culture. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévy, P. Symbolism, Digital Culture and Artificial Intelligence. Rev. De Educ. A Distancia 2025, 81, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Troisi, O.; Grimaldi, M.; Loia, F. Think human, act digital: Activating data-driven orientation in innovative start-ups. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 452–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, P. Marketing in Hospitality and Travel; Educohack Press: Delhi, India, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, E.; Pollard, C.; Wood, G. Information Technology for Management: Driving Digital Transformation to Increase Local and Global Performance, Growth and Sustainability; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B.; Alharethi, T. Reimagining Sustainability: The power of AI and intellectual capital in shaping the future of tourism and hospitality organizations. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafimova, V.; Vasilev, V. Digital Culture as A Competitive Advantage in the Sustainable Development of Organizations. AGORA Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2024, 18, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suraji, R. The impact of digital culture on the competitive advantage of SMEs. Dialogos 2022, 26, 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Velyako, V.; Musa, S. The relationship between digital organizational culture, digital capability, digital innovation, organizational resilience, and competitive advantage. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 11956–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degirmen, G.; Ozbey, D.; Sardagı, E.; Tekin, I.; Koc, D.; Erdogan, P.; Arık, E. How Does Digital Transformation Moderate Green Culture, Job Satisfaction, and Competitive Advantage in Sustainable Hotels? Sustainability 2024, 16, 8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyati, D.; Murwaningsari, E. Achieving green competitive advantage through organizational green culture, business analytics and collaborative competence: The mediating effect of eco-innovation. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 98–113. [Google Scholar]

- Padua, D. Digital Cultural Transformation; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ferdianto, R. The role of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in increasing repurchase intention in the era of the covid-19 pandemic. Res. Horiz. 2022, 2, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitellaro, F.; Schifilliti, V.; Buratti, N.; Cesaroni, F. I won’t become obsolete! exploring the acceptance and use of GenAI by marketing professionals. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biletska, I.; Paladieva, A.; Avchinnikova, H.; Kazak, Y. The use of modern technologies by foreign language teachers: Developing digital skills. Linguist. Cult. Rev. 2021, 5, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stofkova, J.; Poliakova, A.; Stofkova, K.R.; Malega, P.; Krejnus, M.; Binasova, V.; Daneshjo, N. Digital skills as a significant factor of human resources development. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghare, J.J.; Kastikar, A. Digital Literacy and Skill Development. Int. J. Sci. Adv. Res. Technol. (IJSART) 2024, 10, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulganina, S.; Prokhorova, M.; Lebedeva, T.; Shkunova, A.; Mikhailov, M. Digital skills as a response to the challenges of the modern society. Rev. Tur. Estud. E Práticas-RTEP/GEPLAT/UERN 2021, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ercik, C.; Kardaş, K. Reflections of digital technologies on human resources management in the tourism sector. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2024, 16, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Pole, A. Beyond learning management systems: Teaching digital fluency. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2023, 19, 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenakwah, E.; Watson, C. Embracing the AI/automation age: Preparing your workforce for humans and machines working together. Strategy Leadersh. 2025, 53, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulla, M. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and e-learning system use for education sustainability. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.; Nah, S.; Makady, H.; McNealy, J. Understanding user attitudes towards AI-enabled technologies: An integrated model of Self-Efficacy, TAM, and AI Ethics. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 3053–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitezić, V.; Perić, M. The role of digital skills in the acceptance of artificial intelligence. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 1546–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzal, M.; Vivarelli, M. The convergence of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Skills: A necessary space for Digital Education and Education 4.0. JLIS. it 2024, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Li, Z.; Tang, B. Can digital skill protect against job displacement risk caused by artificial intelligence? Empirical evidence from 701 detailed occupations. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0277280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogoslov, I.; Corman, S.; Lungu, A. Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence Adoption for European Union Elderly in the Context of Digital Skills Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Al-Azad, M.; Mohiuddin, M.; Reza, M. Strategic orientations, organizational ambidexterity, and sustainable competitive advantage: Mediating role of industry 4.0 readiness in emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 401, 136765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjielias, E.; Christofi, M.; Christou, P.; Drotarova, M. Digitalization, agility, and customer value in tourism. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ononiwu, M.; Onwuzulike, O.; Shitu, K. The role of digital business transformation in enhancing organizational agility. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 23, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Khan, K.; Shahzad, M. Examining the influence of technological self-efficacy, perceived trust, security, and electronic word of mouth on ICT usage in the education sector. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhiyia, Z.; Hongye, Z. Digital capability and sustainable development of enterprises: The role of long-term competitive advantage. Acad. J. Bus. Manag. 2023, 5, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.; Duy, H.; Thuy, D.; Giang, D.; Chau, V.; Ngoc, N.; Quynh, V. Digital Capabilities and Competitive Advantage in the Context of Technological Uncertainty: Evidence from Emerging Market SMEs. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2025, 29, 2550018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, A.; Paul, S. Fostering Sustainable Workforce Development in the Indian Tourism Sector: Integrating Green Skills and Digital Competencies for Competitive Advantage. In Human Capital Management and Competitive Advantage in Tourism; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 163–196. [Google Scholar]

- Tuo, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Si, X. Artificial intelligence in tourism: Insights and future research agenda. Tour. Rev. 2025, 80, 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakula, A.; Saini, V.; Ahmad, T. The Impact of AI on Organizational Change in Digital Transformation. Internet Things Edge Comput. J. 2024, 4, 75–115. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.; Granić, A. Revolution of TAM. In The Technology Acceptance Model; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 59–101. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, N.; Luo, X.; Fang, Z.; Liao, C. When and how artificial intelligence augments employee creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 2024, 67, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanein, A.; Metwally, A. Hospitality leading green for a sustainable scene: The mediating role of green organizational culture in the relationship between green servant leadership and environmental performance. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2025, 60, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, H. Transforming Tourism: Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Innovation in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 2025 4th International Conference on Computing and Information Technology (ICCIT), Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, 13–14 April 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 312–319. [Google Scholar]

- Alhajri, A.M.; Al-suwaigh, T. Unlocking the Future of Tourism in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA): The Synergy of Commercialization Activities and Sustainable Digital Transformation for Sustainable Industry Growth. Bus. Rev. Digit. Revolut. 2024, 4, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Tourism. Saudi Arabia Tops 100 Million Tourist Mark for the Second Year in a Row, Saudi Arabia. 2025. Available online: https://mt.gov.sa/about/media-center/news/218 (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- UNWTO. UN Tourism Applauds Saudi Arabia’s Historic Milestone of 100 Million Tourists. 2024. Available online: https://www.untourism.int/news/un-tourism-applauds-saudi-arabia-s-historic-milestone-of-100-million-tourist-arrivals? (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Ministry of Tourism. Services Guide—Travel & Tourism Services Regulations and Policies & Regulations Basline; Ministry of Tourism: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Hair Jr Hult, G.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Büschgens, T.; Bausch, A.; Balkin, D. Organizational culture and innovation: A meta-analytic review. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuda, A.; Kartono, R.; Hamsal, M.; Furinto, A. The Effect of Digital Talent and Digital Capability on Bank Performance: Perspective of Regional Development Bank Employees. Proc. Int. Conf. Bus. Excell. 2023, 17, 2053–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, K. Overcoming today’s digital talent gap in organizations worldwide. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2019, 33, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.; Kannan, S.; Raman Nair, S. Factors influencing sustainable competitive advantage in the hospitality industry. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 679–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. WarpPLS User Manual 8.0; ScriptWarp Systems: Laredo, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in VarianceBased SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalan, I. The impact of Artificial Intelligence on Improving Tourism Service Quality in The Egyptian Destination. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sadat City, Sadat City, Egypt, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romeedy, B. Sustainable Bytes: The Digital Literacy and Skills Revolution in Tourism. In Dimensions of Regenerative Practices in Tourism and Hospitality; Tyagi, P., Nadda, V., Kankaew, K., Dube, K., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2024; pp. 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. AI and HRM in Tourism and Hospitality in Egypt: Inevitability, Impact, and Future. In HRM, Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work; Adekoya, O.D., Mordi, C., Ajonbadi, H.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hsiao, A.; Reid, S.; Ma, E. Working with service robots? A systematic literature review of hospitality employees’ perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 113, 103523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial intelligence | 0.876 | 0.967 | 0.743 | |

| AI1 | 0.887 | |||

| AI2 | 0.903 | |||

| AI3 | 0.883 | |||

| AI4 | 0.891 | |||

| AI5 | 0.811 | |||

| AI6 | 0.856 | |||

| AI7 | 0.881 | |||

| AI8 | 0.862 | |||

| AI9 | 0.832 | |||

| AI10 | 0.808 | |||

| Digital culture | 0.791 | 0.904 | 0.701 | |

| DC1 | 0.799 | |||

| DC2 | 0.841 | |||

| DC3 | 0.829 | |||

| DC4 | 0.878 | |||

| Digital skills | 0.883 | 0.976 | 0.730 | |

| DS1 | 0.834 | |||

| DS2 | 0.871 | |||

| DS3 | 0.882 | |||

| DS4 | 0.809 | |||

| DS5 | 0.811 | |||

| DS6 | 0.845 | |||

| DS7 | 0.890 | |||

| DS8 | 0.826 | |||

| DS9 | 0.877 | |||

| DS10 | 0.817 | |||

| DS11 | 0.854 | |||

| DS12 | 0.810 | |||

| DS13 | 0.862 | |||

| DS14 | 0.922 | |||

| DS15 | 0.893 | |||

| Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.851 | 0.921 | 0.746 | |

| SCA1 | 0.889 | |||

| SCA2 | 0.861 | |||

| SCA3 | 0.837 | |||

| SCA4 | 0.866 |

| A1 | Digital Culture | Digital Skills | Sustainable Competitive Advantage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | 0.862 | |||

| Digital culture | 0.438 | 0.837 | ||

| Digital skills | 0.449 | 0.388 | 0.854 | |

| Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.601 | 0.571 | 0.502 | 0.863 |

| A1 | Digital Culture | Digital Skills | Sustainable Competitive Advantage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI | ||||

| Digital culture | 0.398 | |||

| Digital skills | 0.444 | 0.519 | ||

| Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.487 | 0.554 | 0.421 |

| Path | β | s.e | CR | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: AI → Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.527 | 0.076 | 6.934 | >0.001 | Accepted |

| H2: AI → Digital culture | 0.458 | 0.080 | 5.725 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| H3: Digital culture → Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.421 | 0.069 | 6.101 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| H5: AI → Digital skills | 0.509 | 0.082 | 6.207 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| H6: Digital skills → Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.441 | 0.075 | 5.880 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| Mediating effect | |||||

| H4: A1 → Digital culture → Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.193 | 0.050 | 3.860 | <0.001 | Accepted |

| H7: A1 → Digital skills → Sustainable competitive advantage | 0.224 | 0.047 | 4.766 | <0.001 | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alhelal, A.A.; Alshiha, A.A.; Al-Romeedy, B.S. AI-Driven Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Tourism and Hospitality: Mediating Roles of Digital Culture and Skills. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198903

Alhelal AA, Alshiha AA, Al-Romeedy BS. AI-Driven Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Tourism and Hospitality: Mediating Roles of Digital Culture and Skills. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198903

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlhelal, Abdulrahman Abdullah, Ahmed Abdulaziz Alshiha, and Bassam Samir Al-Romeedy. 2025. "AI-Driven Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Tourism and Hospitality: Mediating Roles of Digital Culture and Skills" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198903

APA StyleAlhelal, A. A., Alshiha, A. A., & Al-Romeedy, B. S. (2025). AI-Driven Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Tourism and Hospitality: Mediating Roles of Digital Culture and Skills. Sustainability, 17(19), 8903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198903

_Li.png)