1. Introduction

In recent years, the severity of climate change has expanded both in scope and intensity. It transforms the business environment in unprecedented ways. According to IPCC [

1] and TCFD [

2], climate risk exposure includes not only extreme weather events and natural disasters. It also involves operational challenges such as supply chain disruptions, rising energy costs, and stricter carbon regulations. Beyond these physical and transition risks, global initiatives such as the Paris Agreement, the European Green Deal, and China’s “dual-carbon goals” further compel firms to integrate climate considerations into strategic decision-making. Increasing investor demands for ESG disclosure and mounting stakeholder pressure also highlight that climate risk management has become not only a social responsibility but also a core element of long-term competitiveness. Therefore, it is imperative for corporations to strategically incorporate climate risk management to improve environmental resilience and maintain competitive advantages.

Strategic alliances can help firms mitigate climate-related risks by enhancing interfirm collaboration [

3], supporting green technology development [

4], and reducing information barriers [

5]. Strategic alliances have also been increasingly recognized in the context of sustainability, for instance in green supply chain management, knowledge sharing for clean technologies, and cross-industry partnerships that accelerate the transition to low-carbon economies. However, most existing studies focus on the positive effects of strategic alliances on economic performance and innovation efficiency, while insufficient attention has been paid to their potential environmental downsides.

Existing studies often assume alliances act as a buffer to distribute risks but rarely explore when they might instead amplify vulnerabilities. For example, differences in environmental capabilities and commitment across partners, coupled with complex governance structures, may weaken the effectiveness of green strategies within alliances. This gap is particularly critical because overlooking the possible negative consequences of alliances may lead firms to underestimate their true exposure to climate risks. Hence, studying the role of strategic alliances in climate risk management not only enriches the theoretical framework of environmental management and organizational collaboration, but also provides practical strategic guidance for firms in responding to climate risks.

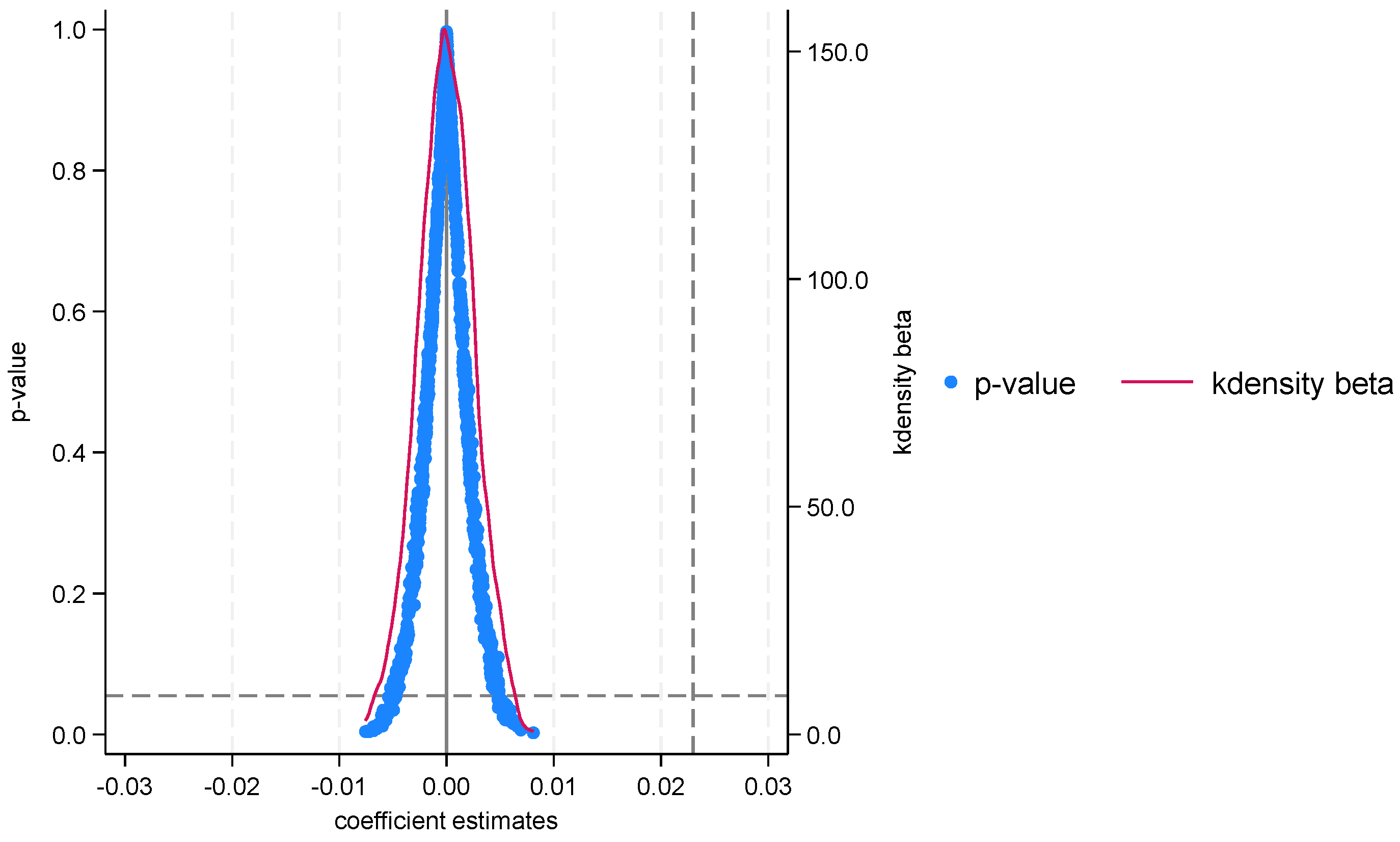

This study systematically examines the impact of strategic alliances in climate risk management. In contrast to existing literature that views alliances as a strategic response to climate risk, this paper introduces a new viewpoint: in certain contexts, strategic alliances may exacerbate rather than mitigate firms’ climate vulnerability. In summary, this study contributes to the literature in three important ways: (1) Measurement innovation: It develops a text-based index to capture corporate climate risk exposure, enriching existing approaches to climate risk assessment; (2) Mechanism analysis: It proposes and empirically tests three mediating mechanisms—executive attention diversion, sustainability capability crowding-out, and supply chain risk underestimation—through which strategic alliances influence climate risk; (3) Heterogeneity exploration: It examines how the impacts of alliances differ depending on carbon performance, firm value, and alliance structure, providing nuanced insights into when alliances mitigate versus exacerbate climate risks.

3. Theoretical Mechanisms and Research Hypotheses

With the strengthening of global climate governance, an increasing number of firms are voluntarily choosing to enhance their adaptive and mitigation capacities by participating in strategic alliances. Nevertheless, when embedding alliance decisions within firm-level practices, an individual firm may face heightened climate vulnerability due to its own organizational constraints and deficiencies in alliance mechanisms.

Initially, internal organizational constraints may be one of the key factors undermining a firm’s capacity to address climate risks. Participants in strategic alliances are typically industry leaders, which are often characterized by large scale and complex operations. As a result, they tend to adopt highly bureaucratic organizational structures. Although such organizational structures facilitate the division of responsibilities, they inevitably lead to issues such as long decision-making chains and complex approval procedures. In turn, the firm’s ability to effectively promote and implement alliance policies will be compromised. Therefore, Hoffman [

36] points out that there is a certain degree of mismatch between firms’ internal capabilities and the expectations placed on them within alliances. This kind of misalignment may prevent firms from accurately identifying the strategic focus of the alliance, clarifying resource allocation priorities, and ultimately concentrating limited resources on critical areas. At the same time, when firms are unable to consistently fulfill their alliance responsibilities due to capability misalignment, it will lead to a series of counteractive mechanisms, such as trust erosion, resource isolation, and so on. Ultimately, firms’ capacity to address climate risks will be undermined.

Second, corporate culture is a deeply rooted institutional factor that serves as a soft yet non-negligible barrier. Due to the enduring and change-resistant nature of corporate culture, employees often tend to maintain existing cognitive frameworks and operational routines [

37]. By nature, alliances often serve as vehicles for institutional transformation and strategic change. Additionally, Piderit [

38] considers that resistance to organizational changes among employees often arises from anxiety over uncertainty, possible harm to personal benefits, and limited engagement in the process. Consequently, such cultural inertia is likely to become a critical factor constraining the value realization of alliances. Simultaneously, organizational culture in many firms is typically risk-averse and short-term oriented. In contrast, alliances often aim to address issues that involve high complexity, high uncertainty, and long return cycles. Ultimately, the misalignment of values may act as a barrier to the strategic integration of alliance initiatives, preventing firms from actively developing their environmental resilience and adaptability.

Beyond firm-level factors, deficiencies in alliance mechanisms can also exacerbate the climate vulnerability of participating firms. On the one hand, information asymmetry within the alliance may lead to overly optimistic assessments of alliance progress. Such misjudgments can weaken firms’ awareness of climate risks and reduce their motivation to strengthen adaptive capacity. On the other hand, alliance members often differ significantly in their motivations for participation and in the extent to which they fulfill their commitments. This heterogeneity may undermine the alliance’s capacity for coordinated governance [

39]. It may also encourage free-riding behavior. All these factors will eventually lead to the erosion of alliance value. In conclusion, the actual effectiveness of strategic climate alliances is constrained by internal structural barriers within firms and institutional deficiencies in alliance design. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Holding other factors constant, engaging in strategic alliances may increase firms’ vulnerability for climate adaptation.

According to Upper Echelons Theory, the personal experiences and value orientations of corporate executives play a significant role in shaping their strategic decision-making paths. For example, executives with advanced education or environmental-related experience are more likely to show strategic foresight and a long-term value system [

40,

41]. Additionally, those raised in severely polluted environments may develop a deeper awareness of ecological responsibility [

42]. Moreover, female executives tend to be more proactive in promoting corporate social responsibility and environmental issues, often exhibiting a preference for consensus building in pursuit of long-term sustainability. Accordingly, the cognitive frameworks and value systems of top executives serve as a key starting point for shaping corporate green strategies.

In the context of actual alliance participation, the limited attention resources of corporate executives become increasingly fragmented due to the complexity of multi-party coordination, the expansion of responsibility scopes, and conflicting goals within the alliance members. The attention-based view suggests that what decision-makers focus on determines what actions organizations take [

43]. In practice, executive attention tends to concentrate on environmentally symbolic, operationally simple, and highly visible “window-dressing” activities, such as green slogans and promotional campaigns, boilerplate environmental disclosure, and the like. In contrast, firms tend to marginalize efforts to build environmental resilience, as such initiatives require long-term investment of significant capital and involve substantial uncertainties. This attentional shift is mainly characterized by symbolic support for environmental issues, accompanied by reduced prioritization of environmental goals in actual resource distribution and strategy execution. Unfortunately, the tendency to rely on symbolic commitments rather than real investments diminishes the strategic impact of environmental initiatives. The concealment of underinvestment in environmental matters can ultimately undermine a firm’s climate adaptability and long-term resilience. Therefore, without substantive governance and a shared value system, alliances as multi-stakeholder platforms may further weaken firms’ internal capacity to cope with climate risks.

In conclusion, the cognitive characteristics and value orientations of top executives serve as a key basis for shaping corporate green strategy. Yet, when faced with limited cognitive capacity and a complex alliance context, executives are likely to engage in opportunistic behavior. Thus, this not only weakens the effectiveness of environmental governance in practice but also undermines the organization’s long-term adaptability and sustainability in response to climate change. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1a. Strategic alliances may fragment executives’ attention to environmental issues.

Moreover, strategic alliances may further weaken firms’ sustainability capacity through the incentive misalignment within organizations. Drawing on Oliver [

44], firms may shift green responsibilities to the alliance level as a way to symbolically meet external pressures while reducing internal commitment. As a result, this may lead firms to deprioritize resource commitment to green capacity building and soften the strictness of associated performance metrics. Due to the lack of tangible incentives linked to green objectives, employees show reduced willingness and effort in building sustainability capabilities [

45]. In summary, incoherence in organizational reward structures may weaken efforts to build green competencies, thus fostering a reliance on superficial and symbolic sustainability actions. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1b. Strategic alliances may undermine their sustainability capacity.

Furthermore, sustainability capability is one of its core competencies for a firm to cope with climate-related uncertainties. This capability is reflected in the firm’s ability to effectively integrate environmental, social, and governance factors into resource allocation, technological innovation, and strategic execution [

46]. In addition, the development of sustainability capability allows firms to navigate escalating regulatory scrutiny [

44] and meet the surging demand for environmentally responsible consumption [

47].

Strategic alliances may fall short of delivering the intended improvements in sustainability capability. Alliance members typically allocate roles according to their strengths within the partnership network. This kind of division of labor can improve operational efficiency in the short run. Nonetheless, Lavie [

48] argues that over-reliance on external collaboration in the long run may erode firms’ internal learning processes and reduce their ability to embed green practices across business functions, ultimately narrowing the space for sustainability capability building. Simultaneously, firms tend to institutionalize their green positioning through structured resource deployment, employee training, and assessment frameworks. Yet, such a structured approach may lock firms into path-dependent practices, making it more costly to adapt or revise their green strategies. Thus, the potential risks and costs of reconstructing green capabilities may further reduce firms’ motivation to move beyond their current limiting structures. In the long run, the persistence of such rigid institutional routines may erode adaptability to external environmental changes.

Seemingly, strategic alliances provide firms with a platform for risk-sharing, particularly in responding to external shocks such as supply chain disruptions or market uncertainties. Barratt [

49] and Das and Teng [

50] claim that such a collaborative mechanism provides a certain buffering effect. In the short term, this mechanism appears to help firms stabilize the environment. Instead, this perceived stability may conceal deeper cognitive distortions in the long term.

Moral hazard theory suggests that individuals tend to reduce their self-protective efforts when external safeguards are in place. Correspondingly, due to reliance on support provided by alliance partners, a firm may neglect independent evaluation and proactive responses to climate risks, resulting in reduced emphasis on investment in adaptive capabilities [

51]. As risk awareness diminishes, both the organization’s adaptive capacity and its willingness to act tend to decline.

Crucially, this decline in cognitive vigilance is not limited to top management but can manifest as structural reliance embedded at the organizational level. For instance, due to concerns over knowledge leakage or competitive risks, firms may deliberately avoid sharing high-quality data or engaging in deep collaboration within the alliance, thereby limiting their ability to identify and respond dynamically to climate risks. Meanwhile, resource dependence and path-locking effects within alliances may gradually erode firms’ capabilities, making them less sensitive to external shifts [

52,

53].

Over time, such dependency from long-term cooperation may significantly undermine a firm’s own capabilities. Instead of independently strengthening their adaptive systems, firms become increasingly reliant on the support offered by their strategic allies. Though effective in boosting short-term performance, this model may lock firms into rigid risk-handling routines over the long term, giving rise to institutional path dependence and undermining organizational agility and innovation [

54].

Overall, strategic alliances may generate a false sense of security and undermine both information flow and capability development. As a result, firms may become less sensitive to supply chain risks, ultimately increasing their exposure to climate-related risks. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1c. Strategic alliances may reduce firms’ sensitivity to supply chain risks.

8. Extension Studying

In assessing the impact of strategic alliances on corporate climate risk, differences in alliance types constitute a critical dimension of heterogeneity. This is primarily because different types of alliances fundamentally differ in how they transmit risks, pursue strategic objectives, and are perceived externally.

Equity-based alliances involve equity ties, which foster closer cooperative relationships, higher levels of inter-firm coordination, and more extensive information sharing. However, they also exhibit stronger risk interdependence. Once parts of the alliance members face climate-related risks, those risks can easily spread within the alliance. Additionally, the limited flexibility of equity-based alliances often leads to delayed responses to environmental changes. Moreover, the governance mechanisms of equity-based alliances are more exposed to external regulation and public scrutiny, which makes them more vulnerable to reputation risks.

In contrast, non-equity alliances have a more loosely structured form of cooperation, with clear organizational boundaries and well-defined allocations of risk responsibilities. Their greater adaptability and flexibility enable firms to adjust their cooperative strategies in a timely manner when facing uncertain climate risk. At the same time, such strategic alliances are typically based on contractual arrangements rather than capital ties, allowing firms to explore green technology collaboration and share climate governance resources at a lower cost. This, in turn, enables them to more effectively isolate and manage climate-related risks.

According to the analysis above, this paper divides the companies into two groups. One group includes the companies that participate only in equity-based alliances in that year. The other group involves the companies that participated only in bilateral contractual alliances or those involved in both contractual and equity-based alliances. According to the regression results in columns (1) and (2) of

Table 8, Alliance is significantly positive at the 10% level, indicating that there is a positive effect of strategic alliances on climate risk in the equity-based alliance group. In contrast, the coefficient is not statistically significant in the non-equity alliance group.

Further F-tests reveal a statistically significant difference in the regression coefficients between the two types of alliances. This result indicates that the alliance structure chosen by firms plays a critical moderating role in their exposure to climate risk. In equity-based alliances, the close cooperative ties may actually exacerbate firms’ risk exposure. In contrast, the flexible cooperation and adaptive mechanisms of non-equity alliances help firms isolate shocks and enhance their resilience.

In summary, firms engaging in strategic alliances should carefully assess the characteristics of different alliance structures in terms of risk transmission and governance flexibility. Priority should be given to non-equity alliance models, which offer greater adaptability and risk isolation capacity. Such choices can enhance firms’ responsiveness and organizational robustness under conditions of climate uncertainty.

9. Conclusions and Suggestions

Strategic alliances are an important organizational strategy for resource sharing and competitive advantage. Based on panel data of Chinese A-share listed firms from 2010 to 2023, this study shows that strategic alliances can inadvertently increase firms’ exposure to climate risk by diverting managerial attention, weakening sustainability capacity, and creating a false sense of supply chain security. Heterogeneity analysis further indicates that firms with stronger carbon performance and higher firm value are less vulnerable and that non-equity alliances, due to their flexibility, provide greater resilience under climate uncertainty compared to equity-based alliances.

These findings carry clear managerial and policy implications. Firms should include explicit climate-related clauses in alliance contracts to mitigate information asymmetry and reduce risks of free-riding and greenwashing. Environmental performance metrics should be embedded into executive incentives to strengthen managerial focus on sustainability. Moreover, alliance structure matters: while non-equity alliances enhance adaptability, equity-based alliances may amplify risks through deeper interdependence. Firms with weaker carbon performance and lower firm value are particularly exposed, calling for targeted regulatory oversight and improved risk management.

Although this study does not focus on a specific industry, the identified mechanisms—such as attention diversion, weakened sustainability capacity, and underestimated supply chain risks—are broadly applicable across industries. We therefore believe the results provide useful insights for managers and policymakers in diverse sectors. Future work could explore industry-level sub-samples or case studies to generate more tailored recommendations.

This study contributes by (1) constructing a text-based climate risk index, (2) empirically testing three mediating mechanisms, and (3) analyzing heterogeneity in carbon performance, firm value, and alliance structure. These contributions enrich research on climate risk and inter-organizational collaboration while also offering actionable guidance for alliance governance.

Despite these contributions, some limitations remain. The analysis is restricted to Chinese A-share listed firms, which may limit generalizability. In addition, the study relies mainly on quantitative analysis; future research could extend to other contexts and incorporate qualitative methods for deeper insights.