Abstract

In service-intensive, compliance-driven settings such as banking, identifying how internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) fosters employees’ vitality and learning is crucial for sustainable organisational performance. Amid growing interest in employee thriving, this study explores how perceived internal corporate social responsibility (PICSR) and moral meaningfulness (MM) shape thriving at work (TaW) through organisational embeddedness (OE). Rooted in self-determination theory, the findings reveal OE as a key mediator between PICSR and TaW, shedding light on how ICSR initiatives influence employee dynamics. The study also reveals that MM alone does not significantly predict TaW directly, but does so indirectly through OE, highlighting the importance of contextual mechanisms. Additionally, it identifies a surprising negative moderating effect of risk-taking, one dimension of intrapreneurial behaviour (IB), on the relationship between OE and TaW, while innovativeness, another dimension, shows no such effect. Theoretical and practical implications underscore the importance of aligning ICSR practices with employees’ psychological needs, supporting moral alignment, and tailoring support for intrapreneurs. Organisations must achieve a balance between autonomy and security to sustain engagement and innovation, advancing human and organisational sustainability, ultimately leading to thriving.

1. Introduction

In today’s dynamic business landscape, internal corporate social responsibility (ICSR) is no longer optional but rather a strategic imperative for long term sustainability [1]. Organisations are expected to go beyond economic performance, embracing ethical, sustainable, and socially responsible values that resonate with employees’ evolving expectations. Amidst heightened competition for talent, increasing demands for employee engagement and service quality and an intensified focus on corporate ethics, organisations also face a parallel demand for meaningful work experiences that foster engagement, promote thriving, and support long-term commitment [2,3,4].

As a response, perceived internal CSR (PICSR) initiatives have gained recognition, alongside growing attention to constructs such as moral meaningfulness (MM), organisational embeddedness (OE) and intrapreneurial behaviour (IB). These constructs collectively reflect employees’ psychological connection to their workplace and their ability to thrive at work (TaW), a state of vitality and learning [5]. Yet, despite their theoretical relevance, limited empirical work has examined their joint interactions in promoting employee thriving, particularly in ICSR-driven service contexts [6,7]. TaW has emerged as a desirable outcome in organisational research, linked to enhanced performance, commitment and adaptability [5]. While prior studies have confirmed the positive impact of PICSR on employee outcomes such as TaW, and employee satisfaction [8,9], the mechanisms through which PICSR fosters TaW, particularly via OE and under varying levels of IB among service sector employees remains under-explored [10].

OE, defined as the extent in which employees feel connected to and invested in their organisations, has been identified as a key psychological mechanism that may explain how supportive environments enable TaW [11]. Similarly, MM, defined as the perceived alignment between one’s work and personal values, has been linked to engagement and well-being [12], yet its role in shaping OE and TaW, particularly under varying levels of IB in the service sector remains empirically limited [6]. In addition to these relational and moral drivers, employee behaviour also varies depending on individual-level tendencies [13]. IB, particularly the dimensions of innovativeness and risk-taking, has been shown to shape employee responses under different work conditions. Yet, only a few studies have examined its role as a boundary condition in ICSR contexts [14]. Employees who display tendencies towards innovativeness and risk-taking may respond to organisational supports such as ICSR and OE differently, depending on the degree of these tendencies, which warrants further investigation. Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [15] explains human motivation through the fulfilment of three basic psychological needs. These are autonomy, competence and relatedness. Respectively, these needs concern the senses of volition, effectiveness and belonging and they collectively enable internalisation of values and sustained energy for growth and learning.

To address these gaps, guided by SDT, this study develops and tests a multi-path model in which PICSR and MM predict TaW directly and indirectly via OE. It further examines whether the interaction between OE and TaW is moderated by IB dimensions, addressing these gaps by uniquely integrating these critical factors with a comprehensible model. This investigation offers theoretical insights by extending SDT into the ICSR mechanisms that reinforce TaW. By integrating relational, moral and behavioural drivers of TaW, this study provides a more holistic understanding of positive employee outcomes. The study highlights the value of aligning ICSR initiatives with employees’ moral values, ethical principles and behavioural tendencies to foster motivation, innovation and retention in competitive service environments. Overall, this study aims to advance prior research on ICSR and TaW by jointly modelling MM, OE and IB within a single framework focused on service organisations. Unlike hospitality and education studies in which the main focus emphasises client-care climates and professional identity, examining a service setting, specifically banking, opens up new opportunities to examine how ICSR and MM translate into TaW via OE and when this route weakens under IB. Grounded in SDT, our microfoundations stress basic needs, satisfaction and bonding mechanisms through which ICSR converted into vitality and learning [15]. Beyond routine conditions, recent crisis-CSR research shows organisations’ capabilities to reconfigure resources to quickly deliver innovative CSR practices, benefiting both external and internal stakeholders [16]. The strict regulatory controls in banking sector allows exploration into how supportive ICSR and MM may impact OE and expression of IB. Framed this way, this study specifies how and when ICSR becomes a platform for resilience and innovation while clarifying the crises-relevant, human-centred pathways that recent CSR innovation studies called for.

2. Literature Review

Understanding how PICSR contributes to TaW is essential to explore its role in strengthening OE. PICSR addresses socially responsible practices adopted by the organisation towards enhancing employee well-being, welfare, and ethical treatment [5,17]. OE, on the other hand, captures the degree of an employee’s attachment to their organisation. It is a multi-façade construct, comprising links, fits, and sacrifices, each influencing how strongly one feels embedded in their workplace [18,19]. Value alignment between personal and organisational values fosters deep attachment and commitment, which is a key component in understanding the PICSR-OE link [20,21]. Per SDT, PICSR satisfies employees’ basic psychological needs by providing autonomy through flexible policies and participatory ICSR programmes. Moreover, it enables competence through skills development while ensuring relatedness through value alignment and ethical organisational climate. Organisations with employee-centred ICSR agendas increase employee commitment and attachment by reinforcing embeddedness [22]. Organisations that actively promote inclusive and wellbeing-oriented ICSR agendas build stronger bonds between employees and leadership [23]. These agendas reinforce trust, cooperation, and mutual respect, which deepen social ties within the workplace [24,25]. Employees who perceive strong organisational support through ICSR [26], they often feel a greater sense of obligation and commitment which has direct consequences on turnover intentions [27,28,29]. These employees may resist leaving due to invested time and energy, interpersonal relationships and forfeited ethical alignment [30,31,32,33].

SDT offers further insights into the PICSR-OE relationship. ICSR practices that support personal development promote autonomy, empowerment, and motivation [20,27]. Employees who feel they have decision-making power and value-aligned work are more likely to feel embedded [34,35]. Autonomy supports meaningful engagement. ICSR initiatives foster competence by making employees feel capable, confident, and proud of their contributions [36]. It cultivates a work environment where individuals take pride in their work and also in their organisation, which reinforces their willingness to stay there, addressing the sacrifice dimension of embeddedness. For employees who feel personal and professional growth, ICSR becomes a source of meaning development which fosters relatedness by promoting inclusion and community-oriented practices, making employees feel valued and connected [27]. These social bonds bring about a plethora of benefits, such as increasing embeddedness while reducing the desire to seek alternative employment [23,37]. Consistent with SDT, PICSR signals autonomy and fairness, satisfying competence and relatedness which strengthens employees perceived fit, links and sacrifice, increasing OE [30,34,36].

H1a.

PICSR positively influences OE.

While MM has been shown to directly influence TaW, it also plays an important role in fostering employees’ embeddedness in their organisation. Humans have an inherent drive to derive meaning from their actions, which in turn gives rise to a sense of purpose and value [12]. Rosso et al. [38] explain that employees seek more than financial returns from their work; they want work that feels meaningful. This has prompted organisations to adopt policies that help employees engage more deeply with their roles. MM concerns the meaning drawn from daily work activities, especially about ethics and personal values [39,40].

A positive ethical climate fosters trust and engagement by aligning individuals’ values with organisational ones [6]. Ethical sense-making reinforces attachment and retention through OE. Employees who find moral meaning at work feel greater fit, motivation and belonging, which brings about loyalty and, attachment towards the fulfilment of obligations [41,42]. According to Deci et al. [43], intrinsic motivation is a significant result of organisational agendas that foster support for moral action. SDT posits that alignment between organisational and personal values strengthens the need for autonomy. Moral alignment boosts relatedness and competence. When work aligns with the self, employees internalise organisational value, strengthening fit and links tied to embeddedness [23,36,42]. Rosso et al. [38] argue that organisations promoting a culture of MM, tend to nurture autonomy and recognise employees’ identities, which increases attachment. Zhang et al. [44] find that employees who experience moral meaning at work tend to report greater satisfaction, commitment, and stronger social ties via robust relational links [36]. Baard et al. [45] emphasise that MM enhances competence by giving employees a sense of impact and purpose. When employees perceive their work as morally significant, they are more likely to invest in it, reinforcing their connection to the organisation.

H1b.

MM positively affects OE.

While MM addresses employees’ internal motivation, their experiences of OE play an equally crucial role in enabling TaW. TaW often exhibit conscientiousness, reflected in traits such as persistence, dedication, and goal-orientation [46]. These individuals demonstrate a strong sense of personal responsibility and commitment to their tasks [47]. Organisationally embedded employees, in particular, tend to display high levels of connectedness and alignment with the organisation’s structure and values [11]. When employees perceive a strong alignment or fit with an organisation’s vision, values, and culture, they experience a heightened sense of belonging [41]. This sense of alignment satisfies relatedness need per SDT, which supports intrinsic motivation, vitality and learning.

The psychological needs outlined by SDT, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, help explore how OE supports TaW [48]. Employees who feel emotionally and professionally invested in their workplace are less likely to leave, as the cost of quitting includes both personal and professional sacrifices. Additionally, long-term relationships developed within the organisation further strengthen embeddedness. These social bonds, built through shared goals and collaboration, become integral to an employee’s identity and work experience [30]. The human connection aspect of embeddedness inspires individuals to flourish in their job outcomes, satisfying both the competence and relatedness components of SDT. OE provides the basis that nourishes relatedness, competence and autonomy. It assists in converting day-to-day experiences into vitality and learning [30,45,46]. Highly embedded employees are more likely to thrive [49]. It has been emphasised that employees’ experiences are shaped by the social interactions at work. Positive emotions fostered through these interactions contribute to a stronger sense of OE, which in turn enhances work engagement and TaW [50].

H2.

OE positively influences TaW.

To understand how ICSR shapes employee experiences, it is essential to define PICSR and its connection to TaW. PICSR refers to employees’ perceptions of an organisation’s collective ICSR behaviour. It captures employees’ interactions of how their organisation engages in socially and ethically responsible behaviour [35]. These perceptions can significantly shape psychological experiences at work, influencing vitality and growth. TaW has been characterised as a psychological state of mind that influences one’s sense of vitality and learning at work [51,52]. Thriving is considered a key driver of organisational sustainability, with vitality described as aliveness and energy, and learning understood as growth through the acquisition of new knowledge and skills [53,54].

Building on these definitions, Spreitzer et al. [50] offer a socially embedded model of TaW grounded in SDT with a self-adaptation perspective. They argue that individuals engage in more agentic behaviour, such as heedful relating, task focus, and exploration, when supported by certain contextual factors, such as supportive work climate and trust [53]. Such contextual factors tend to affect how employees perceive TaW [46]. Furthermore, per SDT ICSR practices that support autonomy and affirm competence would directly enhance vitality and learning, hence promoting TaW [43]. Effective leadership can stimulate learning and vitality as well, which in turn leads to thriving by reinforcing knowledge accumulation from ICSR practices that harbour personal growth initiatives [49]. This, in turn, develops passion among employees to TaW [55]. ICSR initiatives such as decision-making discretion, and climates of respect and trust, create empowering environments that enhance autonomy and engagement [56,57].

The role of the organisation in enabling or hindering employee thriving has been a recurring theme in the literature. Spreitzer et al. [50] argue that these systems may fuel or deprive TaW, depending on their design and emphasis on supportive practices such as ICSR. Certain factors such as decision-making discretion, providing fair feedback, creating a diverse working environment, and preventing incivility improve one’s potential for thriving [58]. Supportive leadership and inclusive social environments, enhances both confidence and collaboration [7,56,59]. By fostering a culture of trust and respect, ICSR strengthens self-efficacy and facilitates thriving through positive social exchange [44,58]. Spreitzer et al. [50] explain that learning and vitality, the core components of TaW, are embedded in social systems. Goh et al. [9] explain that TaW is dynamically dependent on organisational practices that provide support with access to information, support, opportunities, and power. These practices stem from the ICSR agenda of organisations, eventually giving rise to greater TaW [56]. Specifically, within the SDT framework, PICSR initiatives indicate respect and support, hence satisfying the fundamental need for relatedness. Practices that invest in skill development ensures the competence dimension is fulfilled whereas the flexible and trust-based management enhances autonomy [9,15,27,43,45].

H3a.

PICSR positively influences TaW.

Beyond organisational systems and behaviours, the sense of MM that employees derive from their work also plays a critical role in enabling TaW. Kahn [60] defined meaningfulness as a psychological state in which individuals perceive themselves as valued, appreciated, worthwhile, and useful. MM refers to how one draws meaning from their work regarding their values and beliefs [61], reflecting a sense that one’s work matters for personal and organisational outcomes [62]. This sense of self-worth fosters intrinsic motivation and deeper engagement. When employees perceive their work as morally aligned with their values, they are more likely to thrive [50]. Moral meaning in work enhances psychological safety and aligns employee values with the company [38].

Within the SDT framework, Ryan and Deci [15] suggest that when work is experienced as morally meaningful, job responsibilities and personal values become more closely aligned [63]. Per SDT, this alignment establishes autonomy and authenticity, which strengthens intrinsic motivation, thus boosting employee thriving [45]. Employees who find moral meaning in their work tend to be more motivated in developing skills that would potentially aid them in excelling. These skills help employees achieve work goals and leave a positive impact, bolstered by thriving [37,64]. MM and purpose enhance social bonds which connect employees with the organisation’s missions, reinforcing loyalty and commitment [15,65], ensuring the relatedness condition of SDT. With a heightened sense of belonging and shared purpose, employees foster a morally driven motivation towards thriving [27,45].

H3b.

MM positively influences TaW.

Beyond the direct influences presented in the literature, OE may also function as a mediator, linking both PICSR and MM to TaW. From an SDT perspective, OE serves the structural mechanism that converts need satisfaction from PICSR and MM into sustained fulfilment that enables TaW. Rupp and Mallory [22] explain that ICSR initiatives, in particular those that embrace autonomy, fairness, and psychological safety, can foster strong bonds between the organisation and the employees, as well as, between the employees [34]. Likewise, employees who draw a moral meaning from their work tend to be emotionally more invested and aligned with the organisation’s values. These, in turn, strengthen their fit, links, and perceived sacrifices, further intensifying OE [38,41]. From an SDT perspective, OE greatly helps with ensuring the fulfilment of psychological needs, namely, relatedness, competence, and autonomy. This enables vitality and learning, which drive TaW. Therefore, OE may act as the mechanism through which PICSR and MM are translated into TaW.

H4a.

OE mediates the relationship between PICSR and TaW.

H4b.

OE mediates the relationship between MM and TaW.

In addition to the direct effects of PICSR and OE on TaW, IB may moderate the strength of these relationships, particularly through risk-taking and innovativeness. Pinchot [66] describes intrapreneurs as individuals who use already existing resources to develop innovative solutions. While intrapreneurship shares many crucial similarities with entrepreneurship, it diverges on the basis of innovativeness, proactiveness, and risk-taking behaviour [67]. An intrapreneur would not be willing to risk the capital by leaving the organisation should they face a problem [68]. Intrapreneurs take proactive initiatives to implement their ideas, offering innovative solutions to ongoing problems using internal resources, rather than becoming part of the problem. IB has been linked to stronger alignment between personal goals and organisational objectives, which may shape the relationship between OE and TaW [13]. Employees who are embedded and intrinsically motivated are more likely to engage in innovative practices that promote vitality and learning at work, aligning with SDT’s emphasis on autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Stam et al. [69] suggest that employees engaging in IB, experience personal development, self-appreciation, and a sense of purpose, reinforcing the competence dimension of SDT [69]. Moreover, when personal and organisational goals align, interpersonal harmony and cooperation increase [70]. IB is particularly valuable in dynamic environments, where proactive and innovative actions sustain competitive advantage [71].

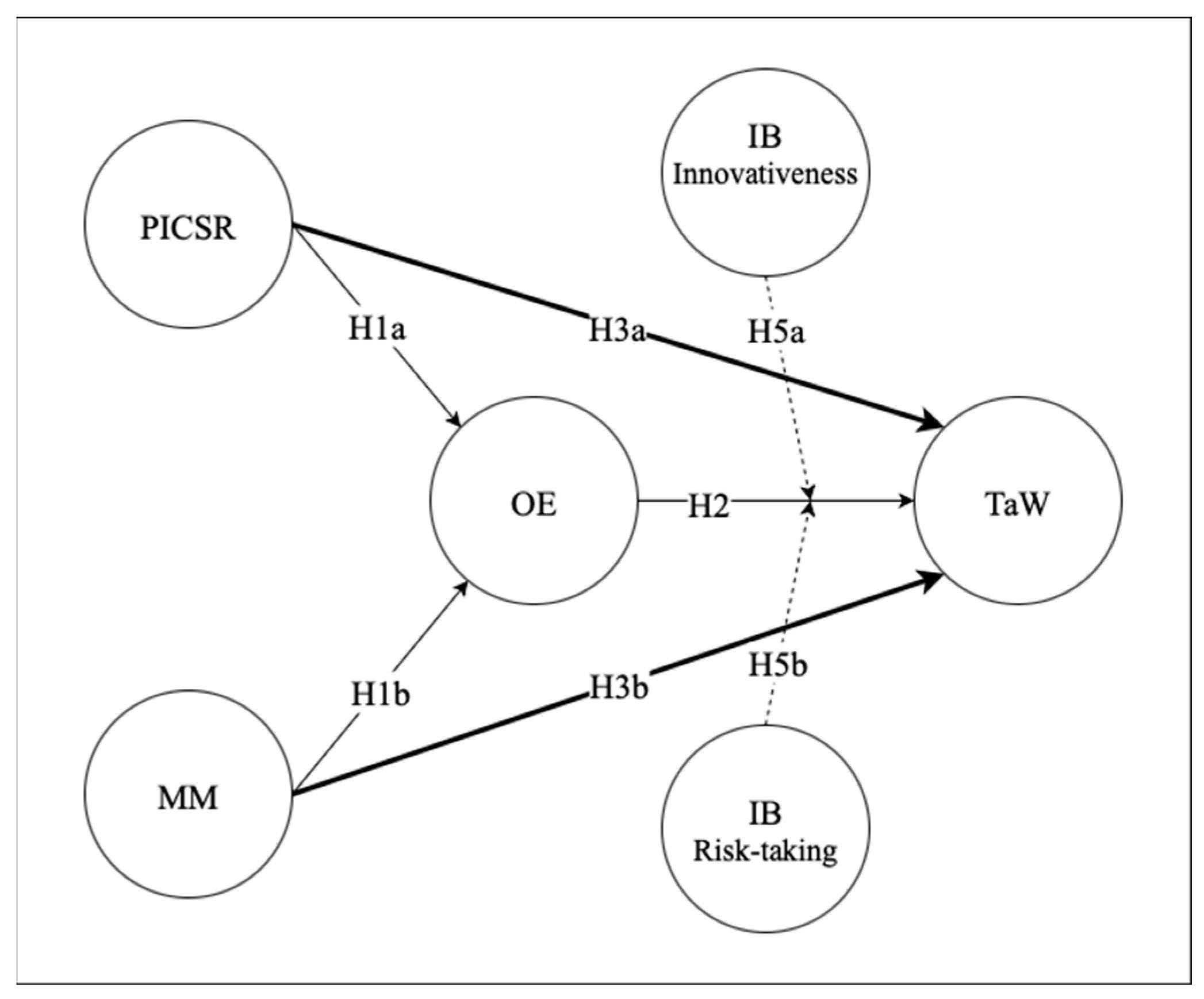

Belitski et al. [13] explain that employees engaging in IB tend to work in an environment that supports autonomy, which reinforces intrinsic motivation. Autonomy, supportive climates allow individuals to reshape their roles, pursue ideas, and feel more purposeful with outcomes that are strongly tied to TaW. Risk-taking, a core dimension of IB, is deeply linked to autonomy [70]. Genuine autonomy requires room for risk, which in turn depends on leadership that does not punish failure but encourages experimentation [72]. According to SDT, relatedness also plays a role. Deci et al. [43] explain that employees feel more confident in taking risks when their teams and leaders are supportive. Collaborative intrapreneurs rely on strong professional networks to share ideas, enhancing their sense of belonging and purpose [45]. Innovativeness, another key IB dimension, involves generating and implementing novel ideas, giving rise to better solutions and alternative approaches to ongoing problems or inefficiencies. Employees with strong innovative strive for achievement and continuous improvement by contributing to organisational evolution [69]. This further reinforces their sense of embeddedness and personal growth. As with risk-taking, innovativeness depends on autonomy. Excessive control can greatly undermine creativity and hinder risk-taking behaviour [73]. Employees, who feel competent and appreciated are more likely to innovate by showcasing their mastery, as competence and relatedness boost confidence and engagement. When leaders and colleagues value new ideas, it strengthens relatedness and encourages further innovation, empowering risk-taking employees. The study’s theoretical framework, specifying the hypothesised relationships, has been presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Conceptual Model. Note: PICSR = Perceived Internal Corporate Social Responsibility, OE = Organisational Embeddedness, TaW = Thriving at Work, MM = Moral Meaningfulness, IB = Intrapreneurial Behaviour.

H5a.

Innovativeness moderates the relationship between OE and TaW, assuming that the link will be stronger when innovativeness is higher.

H5b.

Risk-taking behaviour moderates the relationship between OE and TaW, assuming that the link will be stronger when risk-taking behaviour is higher.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

Data were collected from a sample of full-time banking sector employees, as part of the wider services industry, across North Cyprus’ public and private equity banks. The banks include local and foreign-owned institutions. A print-out format survey questionnaire was distributed to the respondents by their branch managers. The researcher had no direct contact with any respondent. The survey excluded identifying questions for anonymity and confidentiality, and solely targeted full-time employees. The inclusion criteria involved institutions offering both retail and corporate services and employed at least 50 full-time staff to ensure complete CSR infrastructure and formal human resources practices. Eligible respondents were full-time, non-probationary personnel with at least six months’ tenure.

According to the Central Bank of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus [74] employment data, the banking sector was employing 3192 individuals as of March 2024. 343 respondents were targeted to ensure a confidence level of 95% with a 5% margin of error. The surveys were distributed in batches throughout two months. Respondents were expected to return it to their managers within three weeks as response rates tend to plateau after 21 days [75]. In total, 343 surveys were distributed, of which fourteen failed to return the survey within the expected timeframe. A further three surveys were removed due to identical responses across 62 questions, suggesting a bias [76]. Therefore, in total, 326 valid responses were retained for analysis.

3.2. Measurement

Following data collection, the survey instrument was examined in detail. The survey included a total of 50 items, with 6 of them being non-identifying demographic questions. The questionnaire for OE has been adopted from Mitchell et al. [30], consisting of 7 items [30]. To measure PICSR, the 6 items were adopted from Turker [77]. For TaW, the study utilises the twelve items developed by Carmeli and Spreitzer [78]. EIB, risk-taking, and innovativeness, were measured utilising ten items from Stull and Singh [79]. All these were measured on a 5-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree. To measure MM, four items were adopted [42,80]. These were scaled on a 7-point Likert scale with 1 being strongly disagree and 7 being strongly agree. The MM questionnaire followed prior work using a different scale to other variables in the study. This was done to maximise capture of personal morals in finer detail. However, this difference in scales does not cause bias or negative effects in analysis since the indicators load on their own factors and are standardised in SEM [81]. Furthermore, according to Podsakoff et al. [82] utilising different Likert scales in a questionnaire reduces the likelihood of common method bias.

All items were adopted from studies in English. However, they were translated into Turkish for administration. A back-translation method, which ensures the accuracy of the translation, was employed. This process ensured linguistic consistency and cultural sensitivity [83].

3.3. Data Sampling and Data Analysis

For data sampling, this study adopted the convenience sampling method, which is a non-probability sampling method due to time and resource limitations [84]. This method ensures quick and efficient data collection [85]. This research received ethical approval from the relevant ethical committee before data collection. All measures were run through confirmatory factor analysis as part of the structural equation modelling (SEM). The scale items were tested for discriminant and convergent validity to ensure construct validity by making sure the measurements are capturing the intended construct. Internal reliability of all items met the 0.70 (α ≥ 0.70) threshold. The process was carried out on SmartPLS’s SEM function. In addition, Harman’s factor analysis was employed utilising exploratory factor analysis on the dataset to check for common method bias using SPSS (Version 29) which involves assessing whether a single factor accounts for the majority of the variance in the data [86].

The mediating role of TaW and the moderating role of MM were measured using bootstrapping on SmartPLS. The researcher specified the measurement and structural models, incorporating interaction terms between MM and each predictor (TaW, PICSR, and embeddedness). Bootstrapping techniques were employed to estimate the significance of path coefficients. Specifically, the interaction terms were analysed to confirm whether MM significantly altered the strength of the relationships between each predictor and intrapreneurship or not. To further clarify these findings, simple slopes analysis was conducted, calculating regression lines for low, medium, and high levels of MM. Model fit was confirmed using metrics obtained from statistical analysis, which include Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), model goodness-of-fit (GFI) index, and comparative fit index (CFI).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Out of 326 respondents, 211 were male (64.7%) and 115 female (35.3%). The majority (31.9%) fall within the 28–37 age range, with a sharp decline in respondents aged 57 and above. The data highlight a mix of new and mid-career professionals. Further details are available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographical Statistics.

4.2. Measurement Results

Confirmatory factor analysis indicated a need for the deletion of certain items since they did not contribute to the overall fit of the model. Deletion included one item from PICSR, two items from TaW. In addition, one further item from IB, specifically the one testing for innovativeness. This was done to improve the psychometric properties of the measure, in which items with low factor loadings (α < 0.70) were subjected to deletion. Removal of these items improved the internal consistency of the scale by positively influencing the Cronbach’s alpha (α). Removed items had poor factor-loading and did not correlate well within the collective item measurements. Item deletion followed a theory-constrained approach. These items were check for redundancy and reversed item behaviour, yet they persistently yielded low loadings [81,82]. One OE item (loading 0.619) was retained for its theoretical relevance and contribution to the construct reliability [81,82]. The confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated the following fit statistics: (χ2 = 1562.195, df = 17496; χ2/df = 0.088; NFI [Normed fit index] = 0.802.; dULS [Unweighted Least Squares Discrepancy] = 2.503; dG [Geodesic Distance] = 0.888; SRMR [Standardised root mean square residual] = 0.063).

Table 2 illustrates the standardised loading of individual items and the extracted t-values. It also includes Average Variance Expected (AVE) per construct. All standardised loading fulfils the 0.700 threshold. The AVE coefficients for the latent variable fall between 0.600 and 0.783. The shared variances among the latent variables were all lower than each variable’s average variance extracted. Researchers assessed the data utilising the Fornell-Larcker criterion for discriminant validity, and the square root of each construct’s AVE exceeded its inner-construct correlations [87]. Furthermore, cross-loadings were assessed in order to ensure each item’s unique association with its intended construct. These results confirm strong psychometric properties, including convergent and discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Scale items, loadings and AVE.

Table 3 further illustrates the reliability and validity overview of the variables. It showcases AVE, composite reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha (α). Upon analysis, all constructs fit within the acceptable parameters. Upon confirmation of the reliability and validity of variables, the alpha coefficients, means, and standard deviations were analysed to provide an in-depth understanding of the construct.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity overview.

Along with these data, Table 4 includes correlation statistics for the latent variables. The correlation statistics demonstrate a plethora of variety in the magnitude of individual relationships between two specific later variables. All correlations were positive, ranging from 0.054 to 0.746. To analyse the statistical significance of the mentioned correlations, the researcher carried out bootstrapping on Smart PLS 4.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, alpha coefficient and correlations.

Table 5 presents the results of the path analysis, including path coefficients (β), t-statistics, and p-values for the relationships among the latent variables in the model. The analysis provides insights into the relationship between PICSR, MM, OE, TaW, IB-RiskTaking, and IB-Innovativeness.

Table 5.

Model Path Analysis Results.

The path coefficient for the relationship between PICSR and OE is β = 0.648, which is statistically significant at the 5% significance level (t = 19.994, p < 0.01). This finding suggests a strong positive association between PICSR and OE. Hence, accepting H1a. The relationship between MM and OE has a path coefficient of β = 0.113 and it is statistically significant at a 5% significance level (t = 2.749, p < 0.01), suggesting a positive relationship between the variables. Thus, H1b is also accepted. The relationship between OE and TaW is statistically significant at the 5% level and has a path coefficient of β = 0.316 (t = 4.908, p < 0.01), proving H2. Furthermore, the analysis offers an understanding of the direct relationships between PICSR (a) and MM (b) with TaW. The former is statistically significant and has a path coefficient of β = 0.365 (t = 6.268, p < 0.01), thus the H3a is accepted, which states that there is a positive relationship between PICSR and TaW. The latter, on the other hand, is statistically insignificant at the 5% level (β = 0.017, t = 0.323, p > 0.05). Therefore, it is concluded, by rejecting H3b, that MM and TaW do not have a statistically significant direct relationship.

Upon reviewing the direct interactions of two independent variables, namely, PICSR (a), OE (b), on TaW, a further analysis of an indirect interaction between them was tested, with OE acting as a mediator term. Results are presented in Table 6. The indirect effect of PICSR on TaW via OE is β = 0.205, significant at the 1% level (t = 4.938, p < 0.01). This suggests that OE mediates and amplifies the relationship by a factor of 0.205. Similarly, OE mediates the interaction between MM and TaW (β = 0.036, t = 2.231, p < 0.05). This indicates a modest yet significant mediation effect. This analysis provides nuanced insights into the interplay between PICSR (a), MM (b), and TaW when OE acts as a mediating power.

Table 6.

The mediating Effect of Organisational Embeddedness.

The study focuses on revealing the relationship between 2 dimensions of EIB, namely risk-taking and innovativeness, on the relationship between OE and TaW. The analysis suggests no significant direct relationship between either EIB dimension and TaW. However, their moderating effects offer alternative insights. Table 7 presents a graphical overview of these relationships. When tested on the risk-taking dimension, its mediating effect on the relationship between OE and TaW is statistically significant at the 5% level and has a negative path coefficient of β = −0.158 (t = 2.089, p < 0.05). Thus, H4a is supported. By contrast, the moderating effect of the innovativeness dimension of EIB was not statistically significant (β = 0.045, t = 0.596, p > 0.05). Thus, H4b is rejected.

Table 7.

Moderating Effect of EIB.

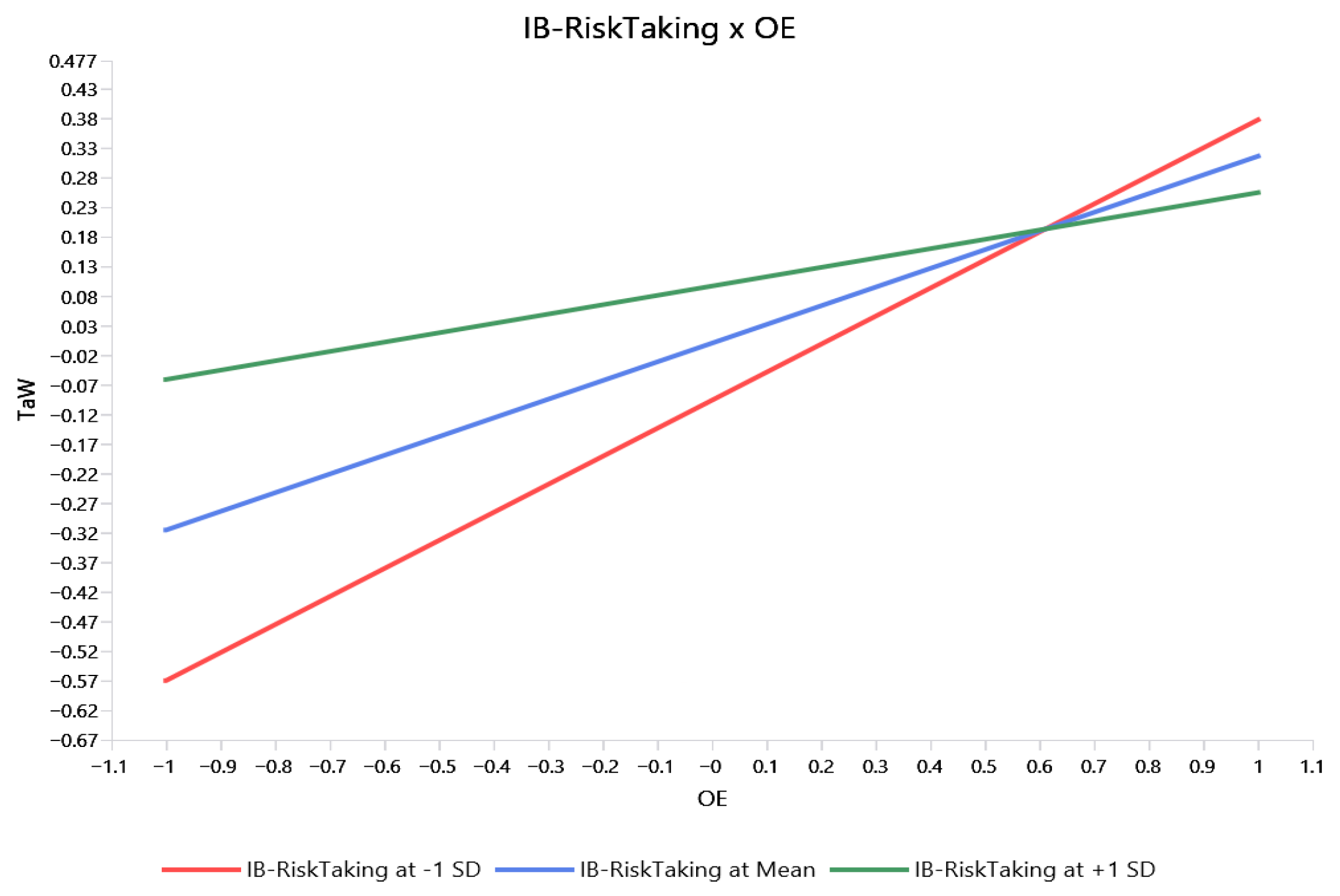

To establish a better understanding of the moderating effect of the risk-taking dimension of EIB, a slope analysis was carried out utilising SmartPLS 4. The analysis added depth to the significant moderation effect, which is illustrated in Figure 2. The slope analysis graph demonstrates the interaction of the risk-taking dimension of EIB, as a moderator, on the relationship between OE and thriving artwork.

Figure 2.

Median Slope Analysis. Note: OE = Organisational Embeddedness, TaW = Thriving at Work, IB = Intrapreneurial Behaviour.

The graph analyses the interaction between TaW and embeddedness at varying levels of risk-taking behaviour in EIB. The slope analysis reveals that at low OE, TaW declines significantly for individuals with low risk-taking behaviour (−1 SD). As OE increases, TaW rises, especially for those with higher risk-taking behaviour (+1 SD).

5. Discussion

5.1. Evaluation of Findings

This study provides empirical evidence supporting the relationships between PICSR, MM, OE, and TaW. Strong ICSR perceptions deepen OE by enhancing attachment, commitment and reinforcing sacrifice, links, and fit [30,34]. The strength of these interactions demonstrates the practical utility of ICSR in shaping workplace experiences. According to SDT, the fulfilment of basic psychological needs through ICSR, fosters motivation, well-being, and sustained engagement [15,43,88]. When ICSR aligns with SDT principles, it acts as a motivational infrastructure that enhances OE and overall employee flourishing [89].

The study also confirms that MM has a significant positive effect on OE. The hypothesis was based on the premise that MM, as intrinsic motivation, influences employees’ emotional and cognitive connection to work [38,39]. Results strongly support this relation, suggesting an interaction between these constructs, confirming it at a high significance level. The findings support SDT’s claim that when work reflects personal values, the psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy are more likely to be met [36]. MM enhances the fit component of OE by aligning employees’ internal compass with organisational missions, while also strengthening links through shared value systems and the sense of working toward a morally motivated goal [90]. The sacrifice dimension may also intensify, as employees who perceive their work as meaningful are less willing to give up such roles. Thus, MM acts as a robust internal motivator for embeddedness [44,45]. Practically, organisations aiming to build embedded workforces should not overlook the ethical and moral resonances of roles. To achieve this objective, they might align organisational objectives with ethically and socially appropriate missions, with a vision that reflects current realities. Embedding ethical narratives into organisational missions and communicating how employee roles serve a socially responsible agenda can strengthen OE. Concretising this moral alignment by updating job designs or offering reflective performance appraisals may further sustain the employee-organisation bond and reduce turnover [41,91].

The results also support a strong direct relationship between PICSR and TaW. This is consistent with prior studies, which found that ICSR practices enhance vitality and learning at work by fostering psychological safety, competence, and intrinsic motivation [34,56]. When employees view their organisation as socially and ethically responsive, they are more likely to draw motivational energy, which in turn is invested in their roles [92]. ICSR creates a work environment that validates personal and professional growth, fulfilling SDT’s core needs [36]. PICSR’s link to TaW shows how organisational values shape employee experiences.

In contrast, the direct relationship between MM and TaW was not statistically significant. MM appears to provide purpose, relatedness and competence, yet in heavily regulated roles (e.g., banking), it may not directly translate into discretion to act. In banking sector, employee roles are generally bound to unique barriers due to the strict regulations and procedures which may be perceived restrictive, lacking autonomy which is a core SDT need. Unlike other sectors (e.g., education, hospitality) where employees have latitude in how they approach tasks, banking personnel must adhere to strict procedures, thus have much less autonomous action. As a result, without autonomy-supportive leadership and organisational support, MM may not materialise into learning and vitality in banking sector. Thus, requiring OE to provide the necessary structure to convert it into thriving. In SDT terms, TaW emerges when the work setting fulfils autonomy, competence and relatedness in situ with OE acting as the conduit that enables that fulfilment. This was unexpected, as prior literature suggests a strong link between MM and TaW [38,50] and likely reflects contextual constraints in the dynamics. One explanation lies in the mediating mechanisms. MM may need OE to provide the necessary organisational support and a structure for cultural and contextual factors in the North Cyprus banking context. MM may ignite a sense of purpose and emotional investment, but without structural and contextual support, such as embeddedness, this potential may not be completely exploited. SDT explains this, as thriving depends on fulfilling autonomy, competence, and relatedness [15]. MM may partially address relatedness and competence of SDT, but autonomy may be constrained in roles where meaningfulness is present but not accompanied by freedom, growth, or support. Thus, MM appears necessary but insufficient on its own to produce thriving. It likely needs to interact with other constructs to cultivate thriving more effectively [63]. This result suggests that HR and ICSR practices must do more than simply evoke meaning. They should also provide structural and cultural supports to ensure that meaning is sustained and translated into employees’ daily work experiences.

Grounded in SDT, OE was also hypothesised to positively predict TaW. The data confirmed this with a moderate but significant relationship. OE reflects more than just emotional loyalty; it showcases an employee’s perception of fit, connectedness, and cost of departure [30] and has been shown to be critical mediator for how meaningful work impacts career outcomes. Employees who feel that they belong, are supported, and are growing professionally are more likely to exhibit vitality and learning [46,49]. OE supports competence through stable growth opportunities, relatedness through sustained interpersonal bonds, and autonomy through role clarity and security. Together, these mechanisms create a strong foundation for TaW [48,64]. These showcase the integration of SDT in this robust mechanism, which might bring about a plethora of benefits if correctly exploited.

Importantly, the results provide a clear insight into the underlying mechanism of OE between PICSR and TaW. OE mediated the relationship between PICSR and TaW. This provides evidence for a layered motivational mechanism where ICSR initiatives foster OE, which in turn cultivates TaW [34,50]. ICSR initiatives act as a reflection of organisational care, which subsequently enhances vitality and learning. OE acts as the psychological and structural channel, ensuring that employees exhibit a heightened level of TaW. The findings align with existing literature, exhibiting potential in which integration of embeddedness into the relationship of ICSR and TaW may contribute to a greater level of understanding of the mechanisms surrounding their interactions [34,41,50]. Organisations should therefore recognise OE as not just a way to keep people around, but as the point where values actually turn into action, and ethics start to become more meaningful. Additionally, the findings also demonstrate that OE mediates the effect of MM on TaW. While MM alone lacks direct significance on TaW, it shapes OE significantly, which then predicts thriving. Employees who perceive their work as morally meaningful are known to have strong alignment with organisational values, acting as a precursor of their great fit at the organisation. This alignment stems from emotional bonds and interpersonal networks that strengthen organisational links [38,93]. This supports earlier conceptualisations that OE offers both structural and psychological infrastructure for sustaining employee growth [41,94,95]. MM might create intention, but OE delivers the capacity for action. Employees who find moral significance in their work and feel embedded are more likely to stay, contribute, and flourish. OE’s full mediation of MM’s effect on TaW underscores the role of contextual mechanisms. Organisations that provide working conditions that are meaningful per one’s moral standing may resonate better with employees, fostering better alignment and building close-knit interpersonal networks. ICSR can further support this process, facilitating the translation of MM into TaW. The role of OE as a psychological channel in mediating the relationship between ICSR, MM, and TaW is through reinforcing employees’ sense of belonging, offering a greater alignment within the organisation, and elevating one’s fit at work.

Finally, the study explored how dimensions of IB moderate the relationship between OE and TaW. This study took a targeted approach to explore how individual IB dimensions affect the relationship between OE and TaW. This avoids treating IB as a whole, allowing clearer emphasis on the effects of individual dimensions. Results show that innovativeness did not significantly moderate the OE-TaW relationship, which suggests that innovative impulses alone do not alter how embeddedness fuels thriving. This could be due to the complexity of innovation, as it may need enabling conditions like psychological safety or cross-functional support to matter. Alternatively, innovativeness might only boost TaW when combined with proactiveness and risk-taking [69,70]. Interestingly, risk-taking negatively moderated the OE-TaW relationship. At higher levels of risk-taking, the positive effect of OE on thriving diminished. This result challenges conventional assumptions that IB uniformly supports thriving. It suggests a tension in which embeddedness offers stability. High risk-takers may view it as constraining or even misaligned with their hunger for risk [72]. This mismatch could undermine autonomy and limit thriving by disturbing exploration. Risk-takers may feel socially isolated or frustrated in risk-averse, conservative environments, further straining their fit [70]. In other words, high OE typically stabilises resources, but for individuals that enjoy risk-taking, this may appear as a constraint. Certain norms and social expectations may signal control, rather than support to them hence, harming TaW. Under SDT, this may be explained by the control vs. support swap narrative. Protective environments can feel constraining, weakening OE’s boost to TaW. This finding also signals that organisations should not assume embeddedness fits all employees equally. For risk-inclined individuals, greater autonomy and a culture that tolerates risk may need to be actively encouraged to fully unlock their thriving potential. From a managerial point of view, this might indicate a need for setting up protected spaces (e.g., sandboxes) for experimentation far from complex bureaucracy where risk-taking is encouraged and failure is not punished. This would eventually provide relief in preventing the risk of OE unintentionally restricting intrapreneurs to thrive [96].

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The findings contribute to organisational behaviour literature by extending the understanding of PICSR, MM, and their respective roles in fostering OE and TaW. This study highlights the mediating role of OE in the relationship between PICSR and TaW. By observing these findings within the scope of SDT, this study adds depth to the understanding of how ICSR initiatives influence employee experiences beyond immediate and external organisational gains. Our results provide a refined mechanism into the interplay of SDT in CSR-driven organisations. The effects of PICSR, whether directly on thriving or indirectly through embeddedness, indicates that autonomy, competence-supportive climates not only energise employees but also offer deeper personal bonds of fit, links and sacrifice.

The study provides new insights into the interaction between MM and TaW, suggesting that MM alone is insufficient to drive TaW. Instead, its effects may be better understood in combination with other organisational factors, such as leadership styles, autonomy, and organisational support, which aligns with the multi-dimensional nature of TaW [50]. MM’s indirect relationship with TaW suggests that moral value alignment strengthens relatedness and competence; however, it necessitates autonomy captured by OE to translate meaning into thriving.

Lastly, the study shows risk-taking negatively moderates the OE-TaW relationship. This suggests that employees with high risk-taking tendencies may perceive OE as restrictive, which limits their ability to thrive at work. This negative moderation reveals a boundary condition which suggests that risk-takers may feel OE to be an autonomy inhibitor. This contradicts the conventional assumptions that suggest IB translates directly to enhanced workplace outcomes. Thus, this brings about the need for highlighting the contextualised assessment of IB when considering it within organisational settings [97,98].

5.3. Practical Implications

From a management standpoint, the findings disclose a plethora of helpful insights. Firstly, organisations should actively focus on their ICSR practices, pushing forward an employee-focused agenda that ensures fair, ethical, and supportive organisational approaches [97]. Secondly, organisations should integrate mechanisms that reinforce the MM of work, which integrates ethical leadership practices, transparency in decision-making processes, and value-driven mission statements in conjunction with ICSR practices to echo with employees’ intrinsic motivations [99]. These, in turn, contribute to OE, gradually and actively aiding retention and engagement. And lastly, organisations must adopt a tailored approach to IB, keeping in mind the delicate balance in yielding benefits from IB, in which encouraging innovation can produce positive results, but promoting risk-taking without sufficient structural support may result in negative consequences. Managers should identify intrapreneurs with high-risk traits and offer autonomy and psychological safety to lessen the conflict that may arise between OE and risk-taking behaviour, which may harm TaW. Practically, leaders may opt out for differentiation regarding autonomy. The protected safe space option [96] for experimentation may yield great results by eliminating the risk of OE overwhelming risk-inclined individuals by restricting their agentic tendencies that enable intrapreneurs to thrive. These safe spaces would avoid excess bureaucracy, offer rapid feedback and approval processes, thus guaranteeing higher autonomy and visible ICSR value, thus directly satisfying SDT. In addition, managers may operationalise moral meaning. This signifies the need for connecting ICSR goals to individual employee targets. This would make talking about ethics and moral issues at work part of core performance, not an extra task.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The study adopted a cross-sectional design, which would infer causal relationships. Future research design may include a longitudinal approach to examine the long-term dynamics within the model. Moreover, the study is geographically restricted to North Cyprus’ banking sector, meaning that it may not be representative of other populations and sectors due to cultural, economic, and industry-related factors (see, e.g., [100]). Cultural contexts in particular vary in their approach to intrapreneurship, especially concerning risk-taking. While some cultures promote risk-taking, others tend towards risk-aversion. Consequently, these cultural divergences in values and behaviours can lead to contradictory or context-dependent outcomes. Testing these relationships, as theorised in the conceptual model, through cross-national samples (e.g., Japan, South Africa, Canada) would improve polychronicity. Moreover, the respondent profiles in banking may greatly differ from those of different sectors (e.g., hospitality, education) hence, the reported results may not be generalisable to employees of other sectors. As a result, the single country, single sector convenience sampling may constrain external validity, utilising other sampling techniques such as probability sampling. In the light of this understanding, replication studies in different service setting, preferably with larger sample sizes in banking sector in North Cyprus (and countries with similar profiles) would be beneficial, integrating cultural and contextual factor to enrich the findings.

Future research may explore these interactions across more diverse organisational settings. While the study examined two dimensions of IB, namely, risk-taking and innovativeness, other dimensions, such as proactiveness, may also play a role in moderating the relationship between embeddedness and thriving. Future studies could adopt a more holistic approach by implementing all dimensions. Lastly, while SDT provided a useful theoretical perspective, future research could integrate alternative frameworks, such as social exchange theory or conservation of resources theory, to offer a different scope to the understanding of the mechanisms between these relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E. and G.K.; methodology, A.E. and G.K.; software, A.E.; validation, A.E. and G.K.; formal analysis, A.E.; investigation, A.E. and G.K.; resources, A.E. and G.K.; data curation, A.E.; writing—original draft preparation A.E.; writing—review and editing, A.E.; visualization, A.E.; supervision, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee for Scientific Research and Publication of Cyprus International University (TBF.00.0-020-6561, 14 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at 10.6084/m9.figshare.29216510.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| ICSR | Internal Corporate Social Responsibility |

| PICSR | Perceived Internal Corporate Social Responsibility |

| MM | Moral Meaningfulness |

| OE | Organisational Embeddedness |

| IB | Intrapreneurial Behaviour |

| TaW | Thriving at Work |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

References

- Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Vázquez-Burguete, J.L.; García-Miguélez, M.P.; Lanero-Carrizo, A. Internal corporate social responsibility for sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, S.P.; Schepers, D.H. United Nations global compact: The promise-performance gap. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, G. The global compact selected experiences and reflections. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 59, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigge, D.M. Bring on the bluewash: A social constructivst argument against using Nike v. Kasky to attack the UN global compact. Int. Leg. Perspect. 2004, 6, 6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Wu, T.J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. A systematic review of thriving at work: A bibliometric analysis and organizational research agenda. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2024, 62, e12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.C.; Shin, H. Securing meaningfulness in corporate social responsibility: Exploring meaning-making mechanisms via economies of worth. Organ. Stud. 2025, 46, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tinmaz, H. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) on thriving at work in the hospitality industry. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2024, 8, 6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.W.; Skitka, L.J. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Z.; Eva, N.; Kiazad, K.; Jack, G.A.; De Cieri, H.; Spreitzer, G.M. An integrative multilevel review of thriving at work: Assessing progress and promise. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 43, 197–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampofo, E.T.; Owusu, J.; Coffie, R.B.; Asiedu-Appiah, F. Work engagement, organizational embeddedness, and life satisfaction among frontline employees of star-rated hotels in Ghana. J. Hospit. Tour. Manag. 2021, 22, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Effect of CSR activities on meaningfulness, compassion, and employee engagement: A sense-making theoretical approach. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 113, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belitski, M.; Karnaouch, I.; Desai, S. IB in organizations: Antecedents and effects on workplace outcomes. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 144, 194–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gawke, J.C.; Gorgievski, M.J.; Bakker, A.B. Measuring intrapreneurship at the individual level: Development and validation of the Employee Intrapreneurship Scale (EIS). Eur. Manag. J. 2019, 37, 806–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintah, E.O.; Elmarzouky, M. Digital-Platform-Based Ecosystems: CSR Innovations during Crises. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, M.; He, Z.; Nyame, G.; Boahen, S.; Frempong, M.F. Effects of internal CSR activities on social performance: The employee perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. An examination of the relationships between work commitment and nonwork domains. Hum. Relat. 1995, 48, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanova, P.; Bernardin, H.J.; Johnson, D.L.; Dahmus, S.A. The validity of a measure of job compatibility in the prediction of job performance and turnover of motion picture theater personnel. Pers. Psychol. 1994, 47, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.; Proença, T.; Ferreira, M.R. Insights into employee perspectives on corporate social responsibility policies and practices: Embeddedness, participation, and meaningfulness through work. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3502–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, O.; Rupp, D.E.; Farooq, M. The multiple pathways through which internal and external corporate social responsibility influence organizational identification and multifoci outcomes: The moderating role of cultural and social orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 954–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Caldwell, D.F.; Barnett, W.P. Work group demography, social integration, and turnover. Adm. Sci. Q. 1989, 34, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyensare, M.A.; Jain, P.; Asante, E.A.; Adomako, S.; Ofori, K.S.; Hayford, Y. Fostering assigned expatriates’ thriving at work through cultural intelligence and local embeddedness: The role of relational attachment. J. Int. Manag. 2025, 31, 101222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Neesham, C.; Manville, G.; Tse, H.H. Ethical climates in organizations: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abelson, M.A. Examination of avoidable and unavoidable turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1987, 72, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; Lee, T.W.; Sablynski, C.J.; Erez, M. Why people stay: Using job embeddedness to predict voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V.; Allen, D.G. Job embeddedness and voluntary turnover in the face of job insecurity. J. Organ. Behav. 2024, 45, 416–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Holtom, B.C.; McDaniel, L.; Hill, J.W. Theoretical development and extension of the unfolding model of voluntary turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 450–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Kelley, K. The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Bus. Ethics Q. 2014, 24, 165–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2024; pp. 6229–6235. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Luth, M.T.; Schwoerer, C.E. The influence of business ethics education on moral efficacy, MM, and moral courage: A quasi-experimental study. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, J. Managers and moral dissonance: Self justification as a big threat to ethical management? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C. Organizational embeddedness and occupational embeddedness across career stages. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Gilson, L.; Harter, L.M. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety, and availability, and the engagement of the human spirit at work. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ling, W.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J. Organizational embeddedness, job satisfaction, and turnover intention: The impact of psychological contract breach and fulfilment. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2015, 43, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Baard, P.P.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic need satisfaction: A motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2045–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Spreitzer, G.; Gibson, C.; Garnett, F.G. Thriving at work: Toward its measurement, construct validation, and theoretical refinement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 250–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulin, C.L. Adaptation, persistence, and commitment in organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2nd ed.; Dunnette, M.D., Hough, L.M., Eds.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 445–505. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Wu, J.; Wan, P. Linking social-related enterprise social media usage and thriving at work: The role of job autonomy and psychological detachment. Kybernetes 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwahhabi, N.; Dukhaykh, S.; Alonazi, W.B. Thriving at work as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and innovative work behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M.; Sutcliffe, K.; Dutton, J.; Sonenshein, S.; Grant, A.M. A socially embedded model of thriving at work. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.C. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and their extra-role behaviors: A psychological mechanism. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhao, S.; Xu, Y. How HR systems are implemented matters: High-performance work systems and employees’ thriving at work. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2022, 60, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinska, B.A.; Rozkwitalska, M. Psychological capital and happiness at work: The mediating role of employee thriving in a cross-cultural context. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8146. [Google Scholar]

- Okros, N.; Vîrgă, D. How to Increase Job Satisfaction and Performance? Start with Thriving: The Serial Mediation Effect of Psychological Capital and Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasradi, R.B.; Sarwar, F.; Droup, I. Authentic leadership and socially responsible behavior: Sequential mediation of psychological empowerment and psychological capital and moderating effect of perceived corporate social responsibility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzopoulou, E.-C.; Manolopoulos, D.; Agapitou, V. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: Interrelations of external and internal orientations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 179, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Jeyaraj, A.; Zhu, M. The impact of enterprise social media affordances on employees’ thriving at work: An empowerment theory perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 198, 122983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ren, S.; Chadee, D.; Chen, Y. Employee ethical silence under exploitative leadership: The roles of work meaningfulness and moral potency. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 190, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalnes, Ø. Leadership and moral neutralisation. Leadership 2014, 10, 456–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; McCauley, C.; Rozin, P.; Schwartz, B. Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. J. Res. Pers. 1997, 31, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zeng, X.; Meng, M.; Morrison, A.M. My work matters! The sequential mediators between employee-perceived CSR and job performance. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 2022, 48, 593–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Morin, A.J.; Van den Broeck, A. Need satisfaction and need frustration as distinct motivational constructs: A look at work engagement, burnout, and job satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 103, 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pinchot, G., III. Intrapreneuring: Why You Don’t Have to Leave the Corporation to Become an Entrepreneur; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Badoiu, G.A.; Segarra-Ciprés, M.; Escrig-Tena, A.B. Understanding employees’ intrapreneurial behavior: A case study. Pers. Rev. 2020, 49, 1677–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B.; Hisrich, R.D. Privatization, corporate entrepreneurship, and performance: Testing a normative model. J. Dev. Entrep. 2003, 8, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Stam, W.; Elfring, T.; De Vaan, M.; Van de Ven, A. Learning through doing: Intrapreneurial projects and the development of entrepreneurial competencies. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2023, 17, 268–290. [Google Scholar]

- Neessen, P.C.M.; Caniëls, M.C.J.; Vos, B.; De Jong, J.P. The intrapreneurial employee: Toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 545–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radebe, N.; Duh, H. Are intrapreneurs the right innovation champions in organisations? In The Implementation of Smart Technologies for Business Success and Sustainability: During COVID-19 Crises in Developing Countries; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 755–767. [Google Scholar]

- Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Covin, J.G. Diagnosing a firm’s internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Quarterly Bulletin—Q1 2024. 2014. Available online: https://www.kktcmerkezbankasi.org/sites/default/files/yayinlar/bulten/B%C3%BClten%202024%20Q1.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).

- Smith, M.G.; Witte, M.; Rocha, S.; Basner, M. Effectiveness of incentives and follow-up on increasing survey response rates and participation in field studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. Effects of impression management and self-deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Spreitzer, G.M. Trust, connectivity, and thriving: Implications for innovative behaviors at work. J. Creat. Behav. 2009, 43, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, M.; Singh, J. Intrapreneurship in nonprofit organizations: Examining the factors that facilitate entrepreneurial behavior among employees. In Proceedings of the Presented at the ARNOVA Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 17–19 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mihelič, K.K.; Culiberg, B. Reaping the benefits of corporate volunteering: The role of authenticity of pro-social behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 567–575. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A.E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, J.; Noor, S.; Tajik, O. Convenience sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 2022, 1, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C.M.; Simmering, M.J.; Atinc, G.; Atinc, Y.; Babin, B.J. Common methods of variance detection in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 3192–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Lee, S.-Y. The effects of internal CSR on employee creativity: The mediating role of work engagement. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 731–744. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Shen, Z.; Ouyang, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Ding, R.; Liao, Y.; Chen, L. Strengths use and thriving at work among nurses: A latent profile and mediation analysis. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, J.; Bluhm, D.; Gaskin, J.; Lyytinen, K. The impact of moral attentiveness on manager’s turnover intent. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2020, 15, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Citizensh. 2009, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechawatanapaisal, D. Meaningful work on career satisfaction: A moderated mediation model of job embeddedness and work-based social support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 889–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slåtten, T.; Mutonyi, B.R.; Lien, G. Why should we strive to let them thrive? Exploring the links between homecare professionals thriving at work, employee ambidexterity, and innovative behavior. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2025, 25, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzeng, E.; Wachter, R.M. Ethics in conflict: Moral distress as a root cause of burnout. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2020, 35, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva Junior, A.C.; Emmendoerfer, M.L.; Lauriano, N.G.; Silva, M.A. Innovation laboratories and barriers to intrapreneurship in governments. Cad. Gestão Pública E Cid. 2024, 29, e90107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Brake, H.; Nauta, B. Caught between is and ought: The moral dissonance model. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 906231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilgetlanguju, F.R.; Suryani, T.; Prawitowati, T. The influence of ethical leadership on organizational citizenship behavior with employee engagement and work meaningfulness as a mediator for employees PT. Bank. X Surabaya. Int. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2024, 8, 408–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, C.P.; Stevens, M.J.; Campion, M.A.; Fernandez, A. A turnover model for the Mexican maquiladoras. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).