1. Introduction

In recent years, with the rise of emerging investment concepts such as responsible investing and green finance, an increasing number of investors and firms have focused their attention on sustainability [

1]. The United Nations (UN) first introduced the concept of ESG in 2004, advocating that firms prioritize environmental protection, social responsibility, and sound firm governance in their operations and development to ultimately achieve sustainable firm growth [

2,

3]. Firm ESG disclosure serves as a critical reference for external stakeholders to assess the extent to which firms fulfill their ESG responsibilities. In China, relevant institutions have successively issued regulations to enhance the ESG disclosure framework and encourage firms to actively undertake ESG responsibilities. By 2023, the ESG disclosure rate among Chinese firms had reached 41.79%, marking a 13-percentage-point increase compared to 2019. Despite significant progress in the adoption of ESG practices among Chinese firms, the question remains whether fulfilling ESG responsibilities necessarily translates into substantial economic benefits for firms. Existing research presents mixed findings on this issue. On one hand, strong ESG performance can help firms mitigate external shocks, build stakeholder trust, and secure access to vital resources [

4,

5]. On the other hand, ESG initiatives often generate positive externalities with delayed returns; the upfront investments involved may strain resources and thus dampen firm value in the short term [

6,

7].

A primary reason for the divergent findings in existing research is that most studies broadly assume a linear relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value, neglecting the possibility of a nonlinear association. Additionally, there is a lack of in-depth examination of the underlying mechanisms linking the two. Resource dependence theory suggests that organizations must engage in resource exchanges with their external environment to survive, creating a web of power-dependence relationships among organizations [

8]. Stakeholders play a vital role in firm development, as firms rely on diverse resources to grow, and stakeholders provide essential support [

9]. For example, employees contribute intellectual capital for green innovation; institutional investors supply capital and strategic information; consumers offer guidance for improving products and services. The ESG concept advocates aligning firm development with stakeholders’ core needs, jointly fostering a community of shared development to achieve sustainable firm growth. Thus, ESG practices can be viewed as strategic actions through which firms acquire resources and legitimacy by addressing stakeholder demands [

10]. However, the extent to which this process influences firm value by safeguarding stakeholder interests remains to be systematically examined.

Among a firm’s various stakeholders, institutional investors serve as key external resource providers. Their shareholding behavior has a particularly significant impact on a firm’s strategic decisions. This influence operates through a dual mechanism that shapes the direction of strategic decision-making. First, compared to individual investors, institutional investors hold a higher proportion of shares and are more inclined to maintain long-term holdings. The shareholding proportion and long-term commitment grant institutional investors governance power in strategic decision-making. Second, institutional investors generally seek long-term returns. When their shareholding proportion is substantial, they can leverage their voting rights and informational advantages to push firms toward integrating sustainability considerations into their strategies. Consequently, to secure funding support from institutional investors, firms often align their actions with investors’ core demands, creating a dynamic “resource dependence–power feedback” relationship. From the contingency perspective of resource dependence theory, this resource dependence–power feedback network is dynamic rather than static [

8]. A firm’s reliance on external resources is conditioned by constraints on its internal resources, which vary across different stages of the firm life cycle [

11]. Firms in the growth stage face stronger resource constraints and typically focus their ESG practices on meeting explicit demands from key stakeholders—for example, prioritizing environmental disclosure to quickly secure funding. Mature firms, endowed with abundant resources, can systematically advance ESG initiatives, thereby building sustainable competitive advantages. Conversely, firms in the decline stage often experience resource depletion pressures and tend to reduce ESG investments. This variation fundamentally reflects how a firm’s internal resource endowment shapes its ESG practices and stakeholder relationship structures [

12]. Therefore, the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests is influenced not only by the proportion of institutional investor shareholding and the firm’s life cycle stage but also by the interaction between these two factors [

11]. How these factors jointly moderate the link between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests remains an important area for further investigation.

Based on the above context, this study focuses on the following questions: (1) Is there a nonlinear relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value, and do stakeholder interests serve as a mediator? (2) How does institutional investors’ shareholding moderate the relationship between ESG fulfillment and stakeholder interests? (3) Does the firm life cycle generate heterogeneous effects of ESG on stakeholder interests? (4) Is there an interaction between the firm life cycle and institutional investors’ shareholding that jointly influences these relationships? To answer these questions, we develop a theoretical framework grounded in resource dependence theory and propose corresponding hypotheses. We then use a sample of Chinese A-share listed manufacturing firms from 2015 to 2022 and employ multiple regression analysis to empirically test the hypotheses.

Compared with existing literature, this study’s innovations and contributions are reflected in several key aspects. First, grounded in resource dependence theory and focusing on the objectives of firm ESG practices, this paper investigates whether fulfilling ESG responsibilities enhances firm value, thereby providing empirical evidence on the economic consequences of ESG. Furthermore, this study theoretically and empirically elucidates how ESG enhances firm value by safeguarding the interests of stakeholders. This addresses a critical gap in the literature concerning the underlying mechanisms linking ESG and firm value.

Second, this study introduces the firm life cycle as a contingent factor, revealing that the impact of ESG on stakeholder interests varies significantly across different life cycle stages. Notably, mature firms—with abundant resources and strong governance capabilities—exhibit the strongest protective effect of ESG practices on stakeholder interests. This finding offers a dynamic perspective on the heterogeneity of ESG implementation. Third, institutional investors are incorporated into the research framework to analyze the moderating effect of their shareholding on the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests. This not only extends the application of resource dependence theory into the realm of capital market governance but also enriches understanding of how capital market participants engage in corporate governance. Fourth, from a contingency perspective within resource dependence theory, this study innovatively integrates internal resource endowment (firm life cycle) and external resource supply (institutional investors’ shareholding) to demonstrate their complementary moderating effects on the ESG–stakeholder interests relationship. Specifically, during the growth and decline stages, the governance role of institutional investors becomes particularly salient. This research deepens and expands the dynamic “dependence–power” relationship conceptualized in resource dependence theory and offers valuable timing insights for effective capital market participation in corporate ESG governance.

3. Research Hypothesis

3.1. ESG Responsibility Fulfillment and Firm Value

Existing research holds that the fulfillment of ESG responsibilities by firms is conducive to enhancing firm value. However, some scholars have put forward opposing views, arguing that fulfilling ESG responsibilities will intensify the consumption of firm resources and is not conducive to value enhancement. The main reason for the divergence in existing research conclusions is that most of the literature generally explains the linear impact of ESG responsibility fulfillment on firm value, neglecting the possibility of a nonlinear relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value. Next, this paper will systematically analyze the nonlinear relationship between the two based on the resource dependence theory. The core view of the resource dependence theory points out that the survival and development of an organization depend on the key resources provided by the external environment [

8] (Hillman et al., 2009). These external environments include various stakeholders such as the government, investors, consumers, communities, employees, suppliers, and environmental protection organizations. To reduce the environmental uncertainty and potential risks caused by resource dependence, organizations must adopt strategies to actively manage their relationships with key resource providers (i.e., stakeholders). Therefore, fulfilling ESG responsibilities can be regarded as a strategy that firms actively adopt to manage their relationships with stakeholders.

When a firm’s ESG responsibility fulfillment level is low, it signifies poor performance in environmental protection, social responsibility, and corporate governance. Examples include inadequacies in safeguarding employee rights, timely information disclosure, and reducing carbon emissions. Consequently, stakeholders perceive the firm as having weak sustainability capabilities and posing potential operational risks. Government authorities may impose stricter regulations and higher penalties on the firm. Nearby communities and environmental organizations may initiate boycotts or lawsuits against it. The resulting public opinion will negatively impact the firm’s reputation, directly damaging its social legitimacy [

34]. At this point, the firm will take internal measures to improve its ESG responsibility fulfillment. For instance, it may establish an ESG department and appoint dedicated staff and managers to drive strategy implementation [

35]. This will increase the complexity of internal management. However, due to the firm’s low governance capacity, these efforts are bound to cause friction between new strategies and old processes, increasing corporate management costs.

Second, to meet external pressures such as government environmental regulations and societal moral expectations, firms need to invest resources in areas like internal governance, green innovation, and social responsibility [

36]. These investments rarely yield immediate results but increase operational costs, ultimately exerting a negative impact on firm value. Simultaneously, firms actively seek external resource support. However, external investors are likely to adopt a skeptical or even negative stance toward the firm’s future operational performance, choosing strategies like adopting a wait-and-see approach or selling shares to maximize their returns [

37]. Major banking institutions will subject the firm’s loan eligibility to stricter scrutiny, further intensifying its financing constraints. Partners within the supply chain, seeking to avoid association with potential administrative penalties, may proactively terminate cooperation. Consumers with environmental or social responsibility awareness will reduce purchases of the firm’s products and services, leading to decreased market share and impaired sales revenue. Firms with low ESG responsibility fulfillment levels struggle to attract employees who value work environments and social purpose, resulting in difficulties in acquiring human resources and higher turnover rates [

38]. Therefore, when a firm’s ESG responsibility fulfillment level is low, it negatively affects the firm’s reputation and social legitimacy, creating a dual dilemma: intensified internal resource consumption and blocked access to critical resources. This ultimately harms firm value.

When ESG responsibility fulfillment surpasses a critical threshold, the established competitive advantages and resource acquisition capabilities begin to gradually outweigh the firm’s operational costs and translate into sustained value creation. First, the investments made by the firm in early-stage ESG practices generate economies of scale, leading to a gradual decline in marginal costs. For instance, in environmental governance, sustained investment in green innovation yields tangible results. Applying these green innovation outcomes to production effectively reduces resource consumption and environmental management costs during manufacturing [

32]. Consequently, the firm’s environmental legitimacy is enhanced, allowing it to avoid environmental penalty costs. Second, firms with high levels of ESG responsibility fulfillment exhibit enhanced capabilities for acquiring critical resources. Large investment institutions are more inclined to establish long-term strategic partnerships with the firm, providing continuous development funding [

39]. Simultaneously, the investment actions of institutional investors signal to society that the firm possesses strong growth prospects [

40]. This attracts substantial individual investors to purchase shares, thereby driving up the firm’s stock price. Furthermore, consumer demand for sustainable products and services is continuously growing. The differentiated green products launched by the firm meet consumer needs, elevating its social legitimacy. This, in turn, promotes product sales growth [

41], strengthening the firm’s competitive advantage in the market and its firm value. Therefore, as the firm’s ESG responsibility fulfillment level increases, it can transform its external dependence on critical resources into a competitive advantage for acquiring scarce and valuable resources, thereby enhancing its survival capabilities within the environment and its long-term value creation potential.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1: There is a U-shaped relationship between the fulfillment of ESG responsibilities and firm value.

3.2. The Intermediary Role of Stakeholders’ Interests

As previously outlined based on resource dependence theory, firm development relies on the support of critical resources provided by stakeholders. Fulfilling ESG responsibilities is an active strategy adopted by firms to manage relationships with stakeholders. Therefore, this paper posits that stakeholder interests serve as the mediating mechanism through which ESG responsibility fulfillment ultimately enhances firm value.

When a firm’s ESG responsibility fulfillment level is low, it harms stakeholder interests, consequently affecting firm value. In terms of environmental protection, firms have weak environmental protection awareness. The emission of harmful substances and white noise pollution during the production process affect the health interests of the surrounding residents [

32]. Resulting protests or lawsuits from the community will increase the firm’s litigation costs and penalty risks. More critically, it may cause the firm to lose eligibility for government subsidies, raising operational costs. In terms of social responsibility, the unreasonable salary system and profit distribution mechanism have seriously undermined the fairness between employees and partners [

38]. The loss of core employees and termination by key partners heighten production disruption risks and reduce production efficiency. Increased unit production costs will further erode firm profits. In terms of firm governance, the lack of ESG information disclosure increases the decision-making risks for investors and undermines their expected returns. Damaged investor confidence will prompt them to intensify scrutiny of the firm in scope and frequency, raising financing costs and restricting funding scale, ultimately increasing operational costs [

16]. Therefore, low ESG responsibility fulfillment damages stakeholder interests, leading to a loss of stakeholder trust. The resulting outflow of critical resources exerts a negative impact on firm value.

As the level of ESG responsibility fulfillment by firms improves, it can effectively safeguard the interests of stakeholders and thereby promote the enhancement of firm value. In terms of environmental protection, firms with a higher level of ESG responsibility fulfillment pay more attention to environmental governance. Firms adopt renewable energy and environmental protection technologies to effectively reduce pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions [

32]. This not only protects the health interests of local residents, but also enhances the environmental legality of firms and avoids environmental regulatory penalties. In terms of social responsibility, firms actively create a fair and competitive working environment for employees, design a reasonable salary structure and talent promotion mechanism. These measures have effectively protected the interests of employees, thereby significantly enhancing their enthusiasm and efficiency at work. The decline in employee turnover rate and the addition of more talents have enhanced the stability and diversity of the firm’s human resources [

38], contributing to the firm’s sustainable development. In terms of firm governance, firms with a high level of ESG responsibility fulfillment regularly disclose information such as the firm’s operating conditions and strategic goals [

42,

43]. Increased transparency in the firm’s operation and decision-making processes helps stakeholders keep abreast of the firm’s business conditions in a timely manner. This further enables stakeholders to reduce investment risks. In addition, the internal control systems and compliance mechanisms established by firms can prevent and reduce related illegal activities. This effectively protects the interests of stakeholders such as investors, suppliers and consumers [

44,

45], thereby enhancing the firm value.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: Firms fulfill their ESG responsibilities by enhancing the interests of stakeholders, thereby increasing the value of the firm.

3.3. The Regulatory Role of Institutional Investors’ Shareholding

Firms are highly dependent on external entities that possess scarce and key resources. Institutional investors are an important force in the capital market to serve the real economy. It has characteristics such as the ability to control capital resources, the ability to collect information resources and social influence. Generally speaking, institutional investors obtain long-term stable returns by purchasing a large amount of stocks of listed firms and holding them for a long time [

32]. Therefore, institutional investors can not only directly participate in firm governance through their shareholder status, but also indirectly influence the development direction of the firm through their position in the capital market. The ESG concept advocates enhancing firm value by safeguarding the interests of stakeholders. This concept perfectly aligns with the long-term profit demands of institutional investors. Institutional investors’ shareholdings mainly influence the relationship between the fulfillment of firms’ ESG responsibilities and the interests of stakeholders through three channels: direct oversight, exit threats, and indirect pressure.

The first mechanism involves direct oversight activities by institutional investors. Institutional investors engage in direct oversight activities, leveraging their professional expertise, financial resources, and information-gathering capabilities compared to individual investors. To achieve excess returns and long-term gains, they actively participate in firm governance, influencing strategic planning and operational decision-making. Given their substantial shareholdings and long-term investment horizons, institutional investors adopt a cautious approach to firm performance monitoring. They typically demand enhanced transparency through public disclosure of internal financial data and governance processes. When firms exhibit short-termism, institutional investors employ corrective measures such as private negotiations with management, public statements, and voting on critical resolutions. By advocating for long-term orientation, they incentivize firms to prioritize ESG responsibility fulfillment [

46]. Furthermore, institutional investors assist in establishing ESG accountability systems and continuously monitor ESG practices, steering firms toward win-win outcomes that harmonize firm value creation with stakeholder interests.

The second mechanism involves exit threats by institutional investors. Firm operations and development require sustained financial support. While the stock disposal actions of a small number of institutional investors may not severely impact a firm’s operations, collective divestment by institutional investors could amplify the deterrence effect of exit threats [

47]. To mitigate this risk, firms proactively disclose information to reduce communication barriers and potential conflicts with institutional investors. By actively fulfilling ESG responsibilities, firms aim to rebuild institutional investors’ confidence in their long-term sustainability prospects. This dynamic compels firms to align their strategies with ESG principles, ensuring continued access to critical capital while addressing stakeholder expectations.

A third mechanism involves indirect pressure tactics by institutional investors. Institutional investment behaviors and trends are often regarded as “market barometers” in capital markets. When institutional investors hold significant stakes in a firm, they signal strong confidence in its growth prospects, prompting retail investors to anticipate excess returns and follow suit. This attracts additional capital inflows, reinforcing the firm’s financial stability. However, partial divestment by institutional investors may trigger a herding effect [

33], as retail investors—assuming institutions possess superior private information—preemptively sell shares to avoid losses. Under such pressure to avert potential liquidity crises, firms are incentivized to actively fulfill ESG responsibilities. By addressing stakeholder demands and incorporating their feedback, firms further enhance stakeholder interests [

44].

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes Hypothesis 3.

Hypothesis 3: Institutional investors’ shareholding will strengthen the positive correlation between a firm’s fulfillment of ESG responsibilities and the interests of stakeholders.

3.4. The Regulatory Role of Life Cycle

The life cycle theory views firms as growing organisms. Firms at different life cycle stages possess varying resource bases and levels of demand, which consequently influence their strategic direction. Firms in the growth stage are typically small in scale, characterized by a weak internal resource base and poor risk resistance [

29] (Hasan et al., 2015). During this phase, the strategic focus is on formulating robust and feasible business plans and securing substantial, stable external resource support. Investors are key providers of funding. Employees are crucial talent driving business planning and product/service innovation. Consumer demand guides the direction of product and service iteration. While fulfilling ESG responsibilities at this stage increases resource consumption and cash flow pressure, firms can attract investors and top talent by establishing reasonable profit and compensation distribution mechanisms. Simultaneously, focusing on and meeting diverse consumer needs helps maintain competitive market advantages. This approach partially alleviates financial crises caused by resource constraints and reduces developmental risks from environmental uncertainty, promoting stable firm growth. For instance, CATL (Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd.) located in Ningde City, Fujian Province, China, implemented an employee stock ownership plan and established a green supply chain management system during its growth period.These initiatives not only attracted a large number of long-term investors but also strengthened its relationships with international clients such as Tesla, laying the foundation for subsequent market expansion.

Firms entering the maturity stage have achieved a certain scale and possess strong production capabilities [

30]. Their products and services are widely accepted by the market. A rich product portfolio and a well-developed service system help maintain a strong brand image. A stable consumer base and potential clients allow the firm to occupy a significant market share amidst fierce competition. Possessing strong resource reserves and market competitiveness, the firm’s strategic focus shifts more towards sustainable development. Ample resources enable the firm to have the capacity and focus to further strengthen ESG responsibility fulfillment. For example, Gree Electric Appliances has continued to advance green manufacturing and energy-saving emission reduction technology development during its mature stage. This not only significantly reduced costs but also effectively safeguarded stakeholder interests, earning the continued trust of both consumers and the government.

As firms enter the decline stage, their products and services struggle to meet consumers’ diversified demands [

48]. The rise in competitors erodes the firm’s existing market share. Declining profitability adversely affects its financial condition. Firms face an operational dilemma of resource misallocation, characterized by internal resource redundancy yet insufficient external resource supply. Under these circumstances, continued fulfillment of ESG responsibilities will exacerbate the firm’s operational costs. Consequently, ESG practices become a primary target for cost-cutting measures. Management may resort to selective information disclosure to conceal poor operational performance from external parties. Alternatively, the firm might invest in projects that appear to have promising development prospects to attract external investment. Though this short-term-oriented ESG practice strategy may temporarily alleviate the firm’s resource shortage, it simultaneously increases investment risks for investors. Ultimately, this adversely affects stakeholder interests.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 4: The fulfillment of ESG responsibilities by firms under different life cycles has differentiated impacts on the maintenance of stakeholders’ interests.

3.5. Dual Regulatory Effect of Life Cycle and Institutional Investor Shareholding

The preceding analysis separately examined the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests under the contexts of institutional investors’ shareholding and different life cycle stages. However, the degree to which a firm relies on external resources is partially dependent on the deficiency of its internal resources [

11]. Therefore, we integrate these two contexts. From the perspective of the interplay between the firm’s internal resource endowments and external resource supply, we investigate the dual moderating effect of the life cycle and institutional investors’ shareholding on the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests.

Firms in the growth stage possess poorer internal resource endowments and exhibit higher demand for external resources. Since the cost effects of ESG responsibility fulfillment precede its economic benefits, this diminishes the firm’s enthusiasm and persistence in fulfilling ESG responsibilities. Under these circumstances, institutional investors alleviate the firm’s financial constraints by providing a capital infusion through shareholding. Their status as shareholders enables them to directly participate in corporate governance. By correcting management’s short-sighted behaviors, they promote the firm’s long-term fulfillment of ESG responsibilities, thereby safeguarding stakeholder interests [

46].

Firms in the maturity stage possess abundant internal resources, reducing the urgency and necessity for external resources. These firms have the capacity and capability to bear the cost effects of ESG responsibility fulfillment and will proactively advance ESG practices. By safeguarding stakeholder interests, they establish stable and reliable relationship networks with stakeholders to achieve sustainable firm development. Under these circumstances, although the involvement of institutional investors can bring resources such as technology, information, and capital to the firm, the firm’s internal resource abundance and high governance standards mean that institutional investors’ shareholding exhibits no significant promoting effect on the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests. For example, Haier Smart Home, as a mature manufacturing giant, has long established a comprehensive ESG management system and a sustainability committee. Despite having numerous institutional investors holding shares, its ESG strategy is primarily internally driven, with the governance influence of external institutions being relatively limited.

Firms in the decline stage experience the coexistence of internal resource redundancy and scarcity of critical resources. They seek external resources to escape their predicament. During this period, firms might exhibit short-term deviations in ESG responsibility fulfillment to acquire external resources. Institutional investors’ shareholding not only alleviates the scarcity of critical resources but also provides information and expertise that help the firm identify operational issues and clarify its development direction. Additionally, institutional investors exert pressure on management to mandate comprehensive ESG information disclosure. For example, Baoshan Iron & Steel, under the impetus of state-owned institutional shareholders, has continuously invested in environmental protection technologies and regularly disclosed ESG information, effectively maintaining various stakeholder relationships and garnering more support for its green transformation. Therefore, when a firm is in the decline stage, institutional investors’ shareholding further strengthens the positive relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests.

Based on the above analysis, this article proposes Hypothesis 5.

Hypothesis 5: When firms are in their growth and decline stages, the modulating role of institutional investors will be strengthened, further enhancing the positive relationship between firm ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests.

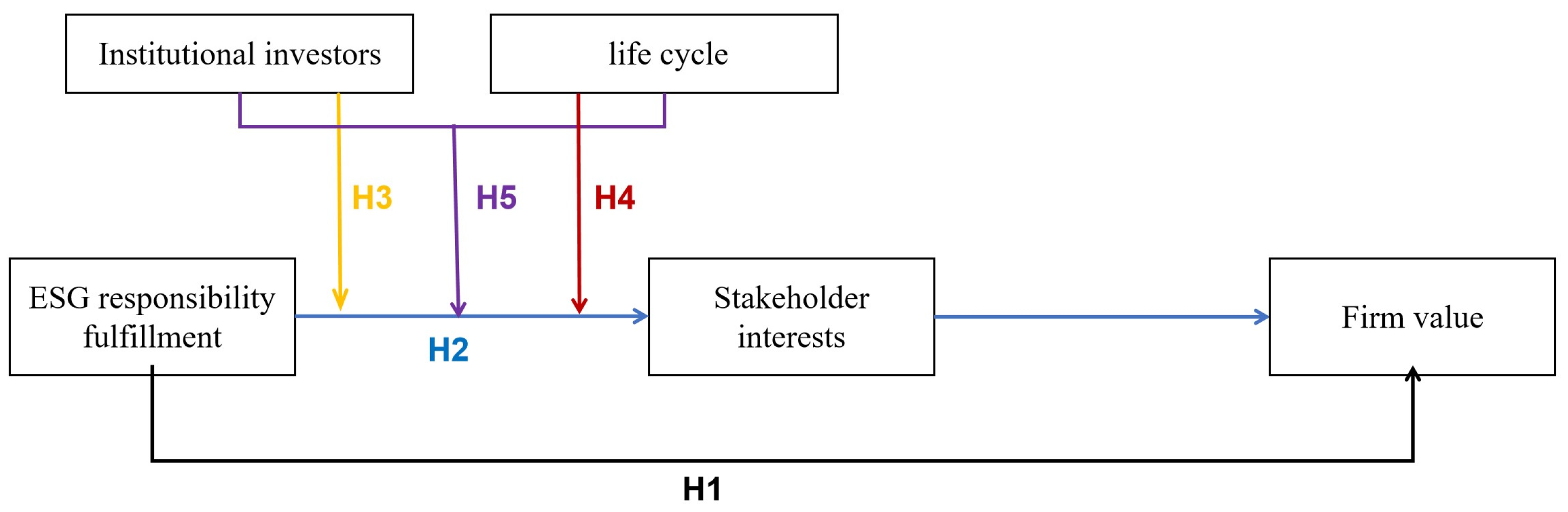

Based on the research hypotheses outlined above, this study develops the theoretical framework illustrated in

Figure 1. In this framework, H1 posits that ESG responsibility fulfillment is associated with firm value. H2 proposes that stakeholder interests serve as a mediating variable in the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value. H3 suggests that institutional investors moderate the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests. H4 posits that the firm life cycle moderates the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests. Finally, H5 suggests the moderating effect of the interaction term between institutional investors and the life cycle on ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder relationships.

6. Discussion

6.1. Research Conclusions

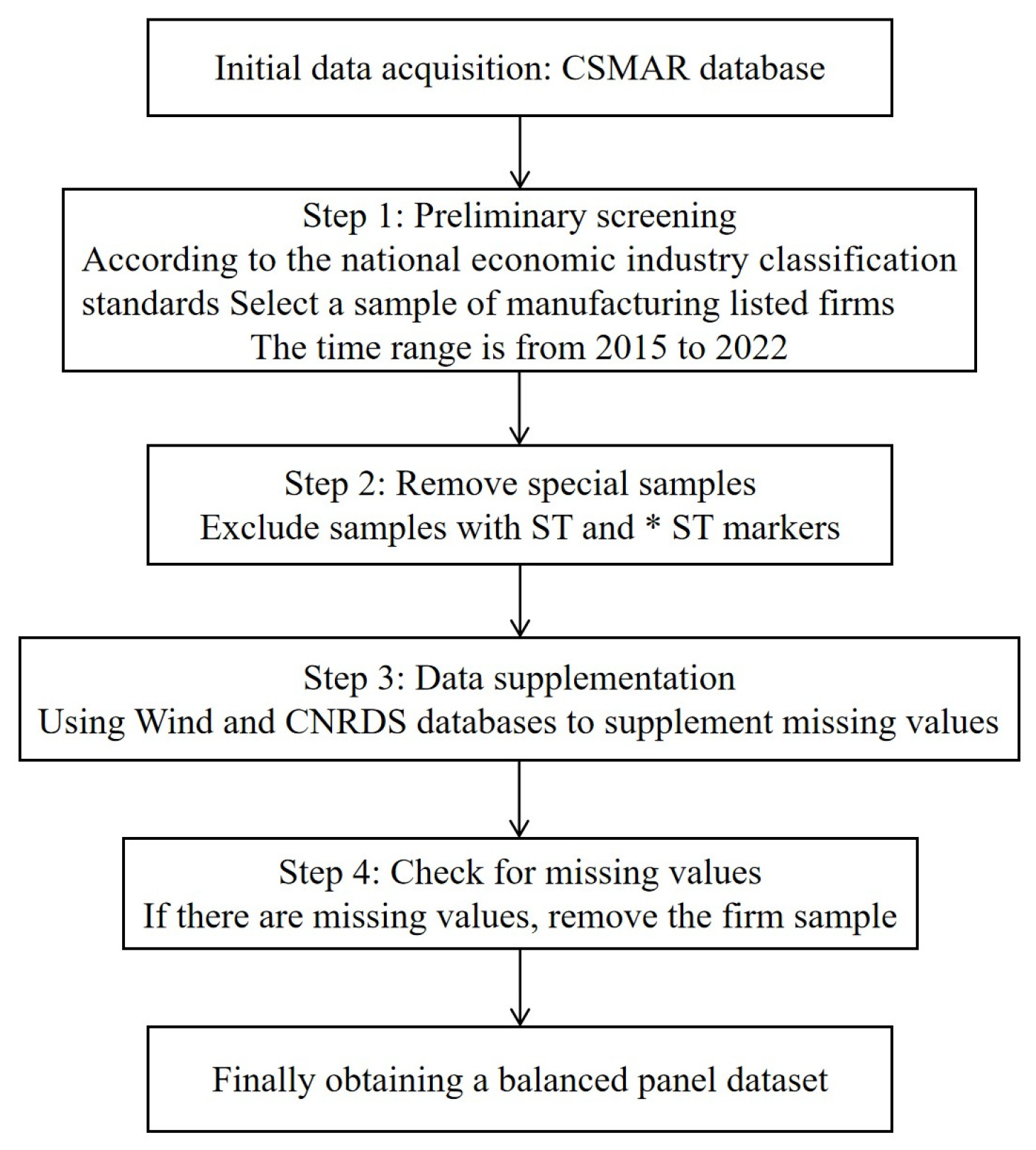

Grounded in Resource Dependence Theory, this study examines the economic returns and internal mechanisms of ESG responsibility fulfillment among Chinese listed manufacturing firms (2015–2022). Building on the contingency perspective within Resource Dependence Theory, the study considers internal resource endowments and external resource supply as contingency factors, exploring the moderating effects of the corporate life cycle and institutional investors’ shareholding on the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests.

Empirical results show the following: (1) ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value exhibit a U-shaped relationship; (2) stakeholder interests mediate the ESG–firm value link; (3) institutional investors’ shareholding positively moderates the relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests; (4) the protective effect of ESG fulfillment on stakeholder interests differs by corporate life cycle stage, being strongest in maturity; and (5) the life cycle and institutional investors ‘shareholding have a complementary effect—their interaction further strengthens the latter’s positive moderating role in the ESG–stakeholder relationship only in growth and decline stages. A series of robustness tests (high-dimensional fixed effects models, alternative core variable measurements, shortened sample period, and instrumental variable methods) verify the findings.

6.2. Theoretical Significance

This paper, grounded in Resource Dependence Theory, conceptualizes ESG practices as strategic behaviors undertaken by firms—with ESG disclosure serving as a critical bridge for firms to communicate their stakeholder-oriented efforts to external resource providers (e.g., institutional investors, governments) and secure critical resources, thereby enhancing firm value.

Firstly, this paper challenges prevailing debates that assume a linear relationship between ESG and firm value by empirically demonstrating a U-shaped relationship. Existing literature often examines the economic consequences of ESG from a static perspective [

1,

20,

23,

24], predominantly assuming a linear linkage. For example, Ademi et al. (2022) [

21] report a positive association, whereas Kim and Yoon (2024) [

24] identify a negative one. Chen (2025) further proposes an inverted U-shaped relationship [

27] with inconclusive findings. Building on Resource Dependence Theory, this study proposes and empirically tests a U-shaped relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and firm value. ESG disclosure serves as a critical basis for external stakeholders to assess a firm’s fulfillment of ESG responsibilities. The inflection point in the U-shaped relationship is closely related to whether the firm’s ESG disclosure can effectively signal its ‘ESG practices’ to external stakeholders. At low levels of ESG engagement, firms struggle to effectively exchange resources, as limited external inputs fail to offset the costs incurred by the firm, resulting in a decline in firm value. Yet, once ESG performance surpasses a critical threshold, it confers a competitive advantage, enabling firms to acquire scarce and valuable resources. This transition repositions firms from passive dependence on external key resources to actively attracting them, thereby enhancing their capacity for survival and value creation. These nonlinear findings not only deepen the application of Resource Dependence Theory in strategic management but also highlight the necessity of reconsidering ESG’s value creation within a framework that emphasizes ESG disclosure quality.

Secondly, this study elucidates the mediating role of stakeholder interests. Previous research has explored the mechanisms through which ESG responsibility fulfillment promotes value creation from perspectives such as financing constraints, social reputation, or R & D investment [

16,

17]. However, this study focuses on the stakeholder perspective, where ESG disclosure plays a pivotal role: only when firms’ ESG disclosure clearly demonstrates how ESG practices safeguard stakeholder interests (e.g., disclosing community investment outcomes, supplier ESG compliance rates) can stakeholders (e.g., institutional investors, governments) trust the firm and provide critical resources (capital, policy support), ultimately boosting firm value. This perspective aligns more closely with the objectives and implementation process of ESG, while also addressing a gap in the current literature concerning the relationship between ESG practices and stakeholder interests.

Finally, this paper introduces moderating variables—namely, the corporate life cycle and institutional investors’ shareholding—into the model to systematically examine the relationship between ESG practices and stakeholder interests. This not only extends the contingency framework of Resource Dependence Theory but also enriches the literature on the role of capital market participants in corporate governance. The results show that mature firms, characterized by abundant internal resources and more stable governance structures, are better positioned to align their ESG practices with stakeholder interests. Institutional investors, as important external resource providers, strengthen the positive relationship between ESG responsibility fulfillment and stakeholder interests when their level of shareholding is higher. Moreover, it is noteworthy that there is an interaction effect between the corporate life cycle and institutional investors’ shareholding. In firms at the growth and decline stages, the governance role of institutional investors becomes particularly crucial. This is because firms at these stages, often driven by short-term profit motives, may engage in actions that undermine stakeholder interests. Institutional investors, serving dual roles as both monitors and resource providers, exert a deterrent effect on the implementation of such strategies. However, when firms enter the maturity stage, their development stabilizes, and internal resources become more abundant. On one hand, firms reduce their dependence on external resources, thereby improving their bargaining power with various stakeholders; on the other hand, they tend to prioritize long-term sustainable development over short-term profitability. Therefore, at this stage, although institutional investors continue to play a governance role, their marginal impact becomes weaker.

6.3. Practical Value

This study provides theoretical support and practical pathways for manufacturing firms in China and other emerging markets to achieve sustainable development.

Implications for managers: (1) ESG practices should be regarded as a strategic investment with long-term returns. Managers need to acknowledge the delayed nature of these returns and avoid abandoning ESG initiatives due to short-term performance pressures. Firms should implement ESG strategies in phased, gradual steps and synchronize ESG disclosure with these steps: in the early stages, disclose low-cost, high-impact actions (e.g., governance transparency improvements, key environmental indicator data, community partnership outcomes); as ESG matures, integrate ESG into core processes (supply chain management, product design) and disclose corresponding stakeholder benefits (e.g., supplier ESG training effects, low-carbon product market share). The goal is to cross the U-shaped inflection point quickly by using transparent ESG disclosure to build stakeholder trust and attract resources. (2) Additionally, firms should establish life cycle-aligned ESG governance and disclosure mechanisms. Growth-stage firms can attract long-term institutional investors by proactively disclosing ESG development plans (e.g., future green investment targets, employee welfare improvement timelines), leveraging investors’ capital and governance capabilities to mitigate resource constraints. Declining-stage firms should use ESG transformation and targeted disclosure (e.g., disclosing restructuring-related environmental protection measures, employee retraining outcomes) to reshape stakeholder relationships and secure policy/market support. Mature firms should systemize their ESG framework and use high-quality disclosure (e.g., annual ESG reports with quantitative stakeholder impact metrics) to position themselves as industry benchmarks.

Implications for Government Agencies and Institutional Investors: (1) Government agencies should develop more targeted and stage-specific ESG policy instruments. For firms in the growth and decline stages, government bodies can support them in overcoming the low point of the U-shaped curve by establishing dedicated ESG transformation funds, such as fiscal subsidies. For mature firms, government efforts should shift toward cultivating industry benchmarks and leadership, encouraging these firms to set more stringent ESG standards and share best practices in management. Additionally, governments should accelerate the development of a unified ESG disclosure framework to reduce information asymmetry and curb “symbolic ESG” (where firms disclose minimal or misleading ESG information). (2) Institutional investors, as key capital market participants, must move beyond purely financial return goals and integrate ESG disclosure quality into pre-investment evaluation and post-investment governance—tailored to firm life cycles. For growth-stage firms, adopt a “investment + governance” approach: use ESG disclosure to assess long-term sustainability and help establish robust ESG management/disclosure systems (e.g., guiding firms to set disclosure timelines). For decline-stage firms, facilitate ESG transformation and demand enhanced ESG disclosure to rebuild competitive advantages while monitoring for short-termism or investor withdrawal during volatility. For all life cycles, institutional investors should actively participate in formulating firms’ ESG strategies and oversee disclosure implementation to ensure substantive stakeholder protection—avoiding reliance on symbolic ESG disclosure.

6.4. Research Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, due to data accessibility constraints, the analysis of the value effects of ESG responsibility fulfillment is confined to a sample of Chinese manufacturing firms. While this sample is highly representative, the generalizability of the findings may be influenced by differences in national institutions, market environments, and cultural contexts. Future research could expand the scope by incorporating data from firms in other emerging markets, as well as from the United States and the European Union, to enable cross-regional comparisons and provide more comprehensive validation of ESG value effects. Second, this paper measures stakeholder interests using secondary data, which entails certain limitations. Future studies could address this by designing surveys that capture perspectives from a broader and more diverse set of stakeholders, including employees, suppliers, and community representatives. Finally, this study employs the Hua Zheng ESG rating to assess firms’ levels of ESG responsibility fulfillment. However, it is important to acknowledge that firms may engage in “symbolic” rather than “substantive” ESG practices. To strengthen the robustness of future findings, researchers could utilize multiple ESG rating databases for cross-validation. Based on the degree of divergence among these ratings, samples could be classified into “high-divergence” and “low-divergence” groups to further test the stability of the results.