Governance of Protected Areas Based on Effectiveness and Justice Criteria: A Qualitative Study with Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Coding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Description

2.2. Methods

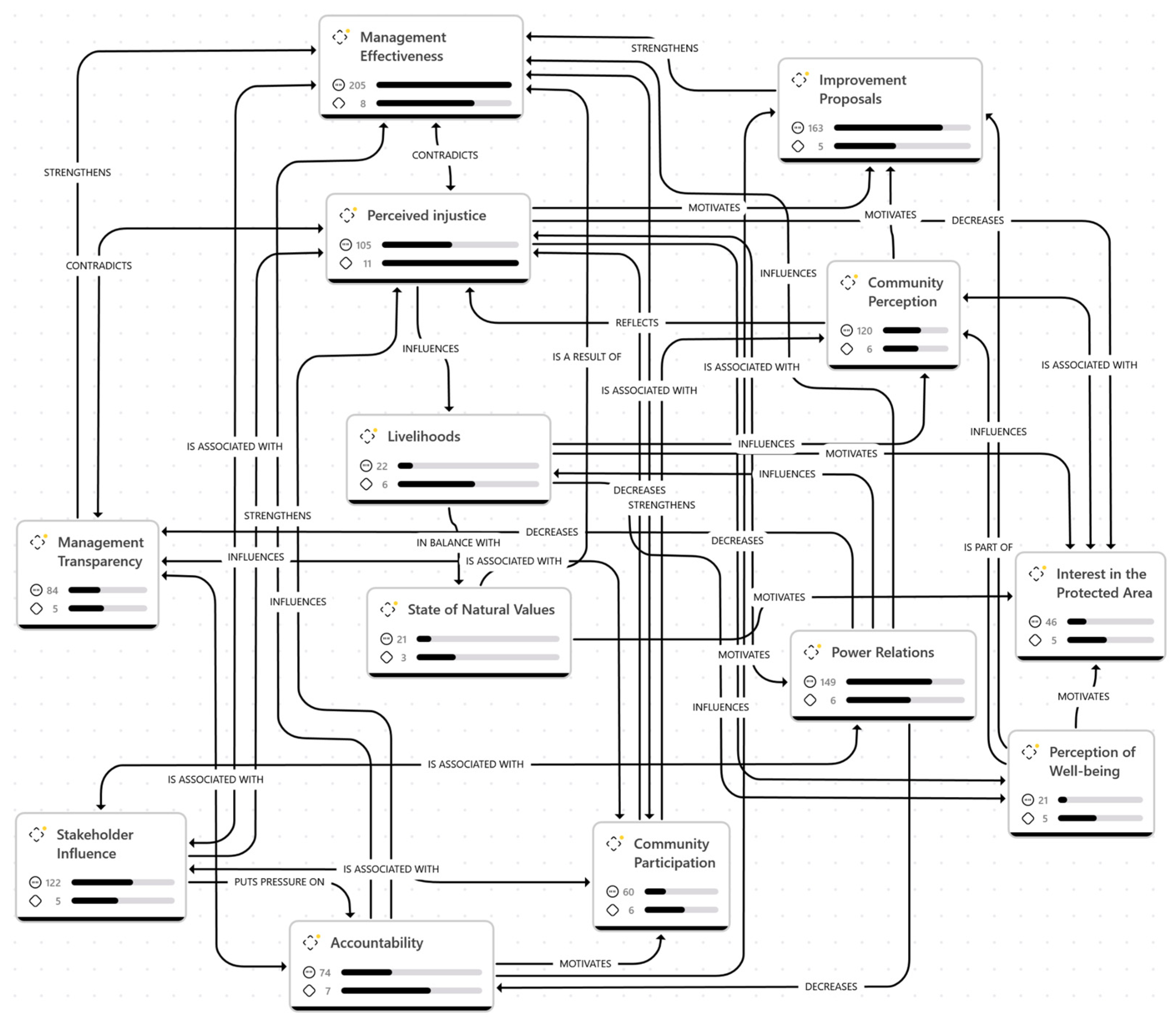

3. Results

3.1. Effectiveness and Justice According to Community Perception

3.2. Effectiveness and Justice as Perceived by Other Stakeholders

3.3. Towards a Sustainable Governance Model in the SPRNP

3.3.1. Institutional Governance Integrating Community Participation for the Sustainable Use of Biodiversity

3.3.2. Public–Private Articulation for Conservation and Sustainable Development

3.3.3. Governance Based on Inter-Institutional Coordination Through the Quadruple Helix

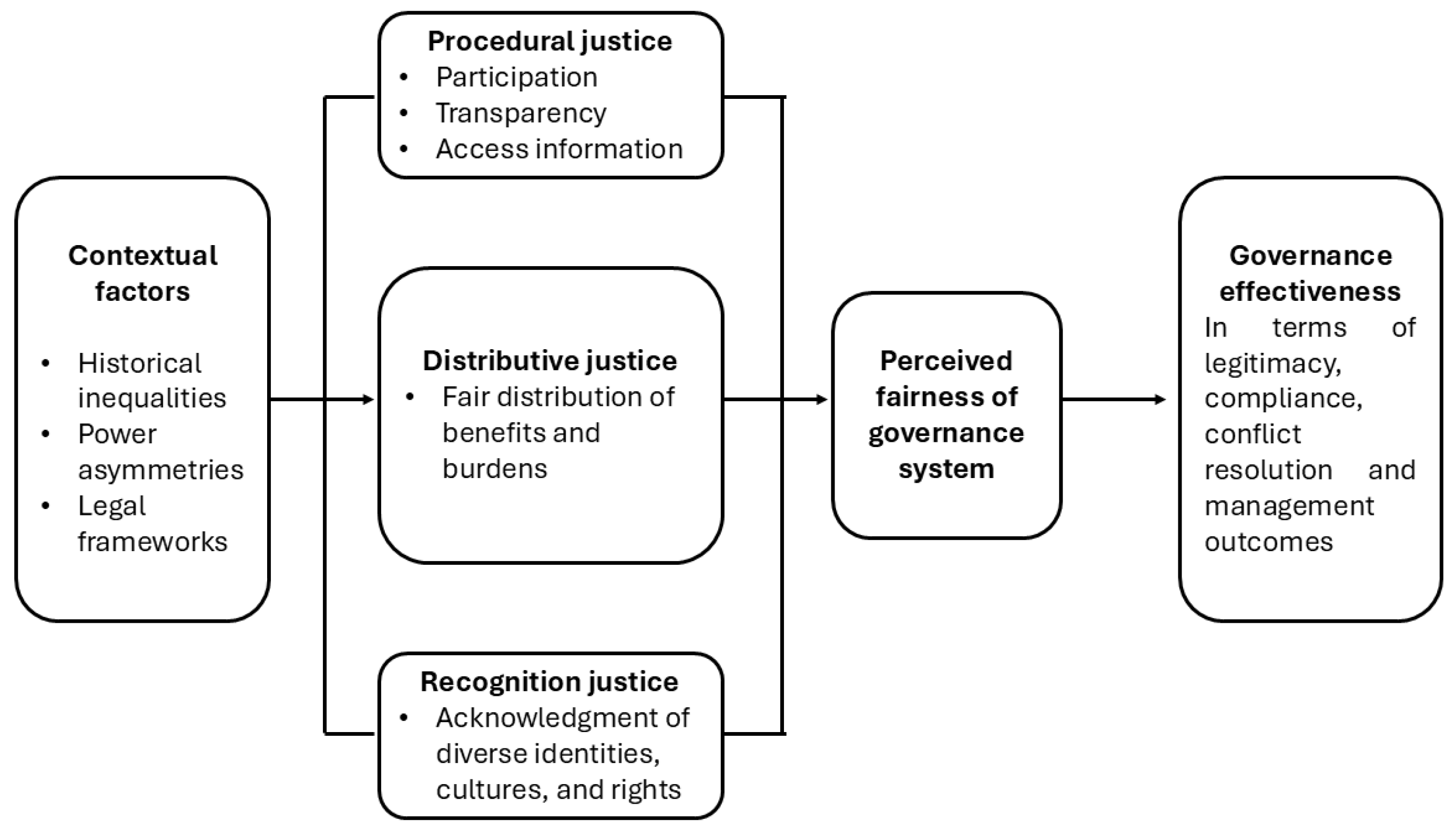

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| METT | Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool |

| NGO | Non-governmental organization |

| PA | Protected area |

| SPRNP | Serranía del Perijá Regional Natural Park |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats |

References

- Bonatti, M.; Bayer, S.; Pope, K.; Eufemia, L.; Turetta, A.P.D.; Tremblay, C.; Sieber, S. Assessing the Effectiveness and Justice of Protected Areas Governance: Issues and Situated Pathways to Environmental Policies in Río Negro National Park, Paraguay. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Zhang, B.; Cai, X.; Morrison, A.M. Do Local Residents Support the Development of a National Park? A Study from Nanling National Park Based on Social Impact Assessment (SIA). Land 2021, 10, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.M.; Newig, J.; Loos, J. Participation in protected area governance: A systematic case survey of the evidence on ecological and social outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 336, 117593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afriyie, J.O.; Opare, M.A.; Hejcmanová, P. Knowledge and perceptions of rural and urban communities towards small protected areas: Insights from Ghana. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relano, V.; Mak, T.; Ortiz, S.; Pauly, D. Stakeholder Perceptions Can Distinguish ‘Paper Parks’ from Marine Protected Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreaux, C.; Zafra-Calvo, N.; Vansteelant, N.G.; Wicander, S.; Burgess, N.D. Can existing assessment tools be used to track equity in protected area management under Aichi Target 11? Biol. Conserv. 2018, 224, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, J.W.; Strange, N.; Smith, R.J.; Gordon, A. Reconciling multiple counterfactuals when evaluating biodiversity conservation impact in social-ecological systems. Conserv. Biol. 2021, 35, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, R.; Breckwoldt, A.; Barboza, R.S.L.; Glaser, M. Local perceptions of spatial management indicate challenges and opportunities for effective zoning of sustainable-use protected areas in Brazil. Anthr. Coasts 2021, 4, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angwenyi, D.; Potgieter, M.; Gambiza, J. Community perceptions towards nature conservation in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Nat. Conserv. 2021, 43, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiaulhaq, A.; Hepp, C.M.; Adjoffoin, L.M.; Ehowe, C.; Assembe-Mvondo, S.; Wong, G.Y. Environmental justice and human well-being bundles in protected areas: An assessment in Campo Ma’an landscape, Cameroon. Policy Econ. 2024, 159, 103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, N.M.; Coolsaet, B.; Bhardwaj, A.; Booker, F.; Brown, D.; Lliso, B.; Loos, J.; Martin, A.; Oliva, M.; Pascual, U.; et al. Is it just conservation? A typology of Indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ roles in conserving biodiversity. One Earth 2024, 7, 1007–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, S.; Fang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, R.; Li, X.; Kang, Y. Generative AI for thematic analysis in a maternal health study: Coding semistructured interviews using large language models. Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2025, 17, e70038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsen, D.; Surbaugh, H.M.; Emmons, M. Using Generative AI for Qualitative Coding. Libr. Trends 2025, 73, 213–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, S.; Raidos, D.; Anderson, E.; Fleetwood, S.; Ainsworth, B.; Fox, K.; Kreppner, J.; Barker, M. Using large language models for narrative analysis: A novel application of generative AI. Methods Psychol. 2025, 12, 100183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.; van Rooyen, A.; Dry, R. In Tandem with Artificial Intelligence: A working Framework for Coding in ATLAS.tiTM. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2025, 24, 16094069251337583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ma, L. Artificial intelligence in qualitative analysis: A practical guide and reflections based on results from using GPT to analyze interview data in a substance use program. Qual. Quant. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel-Ch, J.O.; Carvajal-Cogollo, J.E.; Cortés-Duque, J.; Rivera-Díaz, O.; Rangel-Ch, J.O. Amenazas a la biota (vegetación, fauna, flora, ecosistemas) de la Serranía del Perijá. In Colombia Diversidad Biótica VIII. Media y Baja Montaña de la Serranía de Perijá; Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2009; pp. 661–676. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259977850_Amenazas_a_la_biota_vegetacion_fauna_flora_ecosistemas_de_la_Serrania_del_Perija (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Guerrero, M.C. Estudios Bióticos (Plantas, Fauna Edáfica, Anfibios y Aves) en el Complejo de Páramos Perijá. 2016. Available online: https://i2d.humboldt.org.co/ceiba/resource.do?r=rrbb_paramoperija_faunaflora_2015 (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Rangel-Ch, J.O.; Jaramillo, A.; Niño, L. La Serranía de Perijá: Un Macizo de Excepcional Biodiversidad Perijá: A Massif of Exceptional Biodiversity. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/42136120/La_serran%C3%ADa_de_Perij%C3%A1_un_macizo_de_excepcional_biodiversidad (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cesar (Corpocesar). Acuerdo 021. CORPOCESAR (Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cesar): Valledupar, Colombia, 2016; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.corpocesar.gov.co/files/acuerdo%20021%20de%20diciembre%20de%202016.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cesar—CORPOCESAR. Resolución 1430. CORPOCESAR (Corporación Autónoma Regional del Cesar): Valledupar, Colombia. 2019. Available online: https://www.corpocesar.gov.co/files/resolucion-1430-16-12-2019-DG.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Escobar, C.H.G.; Torres, J.C.G.; Rodríguez, A.O.V. A Critical Analysis of the Dynamics of Stakeholders for Bioeconomy Innovation: The Case of Caldas, Colombia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trialfhianty, T.I.; Quinn, C.H.; Beger, M. Engaging customary law to improve the effectiveness of marine protected areas in Indonesia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 261, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, C.; Nuno, A.; Broderick, A.; Curnick, D.J.; de Vos, A.; Franklin, T.; Jacoby, D.M.P.; Mees, C.; Moir-Clark, J.; Pearce, J.; et al. Understanding Persistent Non-compliance in a Remote, Large-Scale Marine Protected Area. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 650276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Harms, M.J.; Biedenweg, K.; Nahuelhual, L. Incorporating cultural ecosystem services in the measurement of human well-being indicators for transformative environmental policy. In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Ecosystem Services; Routledge: Oxford, UK; pp. 329–341.

- Menon, R.R.; Warrier, M.G. Buffer zones in Wayanad: A social constructivist exploration into farmers’ mental health. Cult. Psychol. 2025, 31, 614–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerberg, C.; Gilek, M.; Tafon, R.; Dawson, L. Governance challenges and opportunities for multifunctional marine and coastal landscapes: A comparative case study of Nämdö national park and Nämdö biosphere reserve in Sweden. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 269, 107787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niner, H.J.; Jones, P.J.S.; Milligan, B.; Styan, C. Exploring the practical implementation of marine biodiversity offsetting in Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, K.; Bonatti, M.; Sieber, S. The what, who and how of socio-ecological justice: Tailoring a new justice model for earth system law. Earth Syst. Gov. 2021, 10, 100124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkansah-Dwamena, E. Aligning conservation goals with forest livelihood needs: Using local perspectives to inform policy and practice in Ghana. Policy Econ. 2025, 177, 103532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhliwayo, I.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Local perceptions on poverty and conservation in a community-based natural resource program area: A case study of Beitbridge district, southern Zimbabwe. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2023, 4, 1232613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degele, P.E.; Chaparro, M.G.; Conforti, M.E. El estudio de las percepciones sociales en una reserva natural de la provincia de Buenos Aires. Un análisis de gestión patrimonial. Mundo Antes 2018, 12, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolton, S.; Dudley, N. METT Handbook: A Guide to Using the Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool (METT); WWF: Woking, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.-P.; Huang, H.-W.; Lu, H.-J. Fishermen’s perceptions of coastal fisheries management regulations: Key factors to rebuilding coastal fishery resources in Taiwan. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 172, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, H.M.N.; Guerreiro, Q.L.d.M.; Vieira, T.A.; da Silva, S.M.S.; Renda, A.I.d.S.A.; Oliveira-Junior, J.M.B. Alternative Tourism and Environmental Impacts: Perception of Residents of an Extractive Reserve in the Brazilian Amazonia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cintio, A.; Sulanke, E.; Di Genio, S.; Niccolini, F.; Sbragaglia, V.; Visintin, F.; Bulleri, F. Investigating artisanal fishers’ support for MPAs: Evidence from the Tuscan Archipelago (Mediterranean Sea). Mar. Policy 2024, 167, 106260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.A.; Wellborn-Watts, C.P.; Herd, T.J. Teacher Beliefs About Race, Empathy, Black Boys: S-TEAAM 2.0. AERA Open 2025, 11, 23328584251326910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brier, N.; Van Schuylenbergh, J.; Van Remoortel, H.; Bossche, D.V.D.; Fieuws, S.; Molenberghs, G.; De Buck, E.; T’sJoen, G.; Compernolle, V.; Platteau, T.; et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of HIV infections in a representative transgender and non-binary population in Flanders and Brussels (Belgium): Protocol for a community-based, cross-sectional study using time-location sampling. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjitunga, U.; Njibama, H.K.; Makuzva, W. Educational Tourism as a Strategy for Sustainable Tourism Development: Perspectives of Windhoek-Based Universities. J. Tour. Dev. 2023, 42, 191–209. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, R.; Ghaderi, Z. Rural tourism initiatives and governance: An insight from Iran. Anatolia 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón, I.S.; Soley, F.G. Investigación para la toma de decisiones de manejo en áreas marinas protegidas como la Isla del Coco, Costa Rica. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2020, 68, S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinert, E.; Milne-Ives, M.; Sawyer, J.; Boardman, L.; Mitchell, S.; Mclean, B.; Richardson, M.; Shankar, R. Subcutaneous electroencephalography monitoring for people with epilepsy and intellectual disability: Co-production workshops. BJPsych Open 2025, 11, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.L.; Madureira, L.M.C.; Diodato, M.A. Las Reservas Privadas del Patrimonio Natural de Brasil en la producción científica: Temas y aportes. Ager: Rev. De Estud. Sobre Despoblación Y Desarro. Rural.=J. Depopulation Rural. Dev. Stud. 2024, 39, 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- Esparza-Huamanchumo, R.M.; Caicedo, Y.L.; Flores, C.E.G.; Román, P.C.R.; Mougenot, B. Perceptions of stakeholders and challenges faced by ecotourism management in a natural protected area in Peru. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 20757–20780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, L. Gobernanza ambiental, actores sociales y conflictos en las Áreas Naturales Protegidas mexicanas. Rev. Mex. Sociol. 2010, 72, 283–310. [Google Scholar]

- Corte Constitucional de Colombia. Sentencia T-713 de 2017; Constitutional Court of Colombia: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017; pp. 1–37. Available online: https://www.corteconstitucional.gov.co/relatoria/2017/T-713-17.htm (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- IUCN. IUCN Green List of Protected and Conserved Areas: Standard; Version 1.1; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.W.; Ruhanen, L.; Ritchie, B.W. Tourism governance in protected areas: Investigating the application of the adaptive co-management approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1890–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neira, F.; Ribadeneira, S.; Erazo-Mera, E.; Younes, N. Adaptive co-management of biodiversity in rural socio-ecological systems of Ecuador and Latin America. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuchs, G.; Kroos, F.; Scherer, C.; Seifert, M.; Stelljes, N. Exploring marine conservation and climate adaptation synergies and strategies in European seas as an emerging nexus: A review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1542705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriollo, E.; Secco, L.; Caimo, A.; Pisani, E. Probabilistic network analysis of social-ecological relationships emerging from EU LIFE projects for nature and biodiversity: An application of ERGM models in the case study of the Veneto region (Italy). Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 148, 103550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, S.; Luzadis, V.A.; Hirsch, P.; Limburg, K.; Diemont, S.A.W. Development of a hybrid public–private natural area governance model in the Adirondack Park of New York State. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, S.L.; Fuller, R.A.; Brooks, T.M.; Watson, J.E.M. Biodiversity: The ravages of guns, nets and bulldozers. Nature 2016, 536, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreckenberg, K.; Franks, P.; Martin, A.; Lang, B. Unpacking equity for protected area conservation. Parks 2016, 22, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.V.E.; Anthony, B.P. Opportunities and Barriers to Monitoring and Evaluating Management Effectiveness in Protected Areas within the Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Region, South Africa. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachali, R.N.; Dawson, N.M.; Loos, J. Institutional rearrangements in the north Luangwa ecosystem: Implications of a shift to community based natural resource management for equity in protected area governance. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.N.; de Barros, E.L.S.F.C.; Dantas, I.F.V.; Bragagnolo, C.; Malhado, A.C.M.; Selva, V.F. Inclusion and governance in the managing Council of the Costa dos Corais Environmental Protection Area. Ambiente Soc. 2022, 25, e00741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G.; Filgueiras, F. Introduction: Looking for Governance: Latin America Governance Reforms and Challenges. Int. J. Public Adm. 2022, 45, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Múnera-Roldán, C.; Colloff, M.J.; Pittock, J.; van Kerkhoff, L. Aligning adaptation and sustainability agendas: Lessons from protected areas. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Chang. 2024, 29, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongol, Y.; Neumann, R.P. State making through conservation: The case of post-conflict Nepal. Polit. Geogr. 2021, 85, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, A.; Rose, J. Balancing tourism, conservation, and development: A political ecology of ecotourism on the Galapagos Islands. J. Ecotourism 2016, 15, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Alruiz, M.D.; Gómez-Liendo, M.J. Just conservation? Knowing Mapuche perspectives on environmental justice at Villarrica National Park, Chile. J. Political Ecol. 2025, 32, 5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orozco-Ospino, J.; Florez-Yepes, G.; Diaz-Muegue, L. Governance of Protected Areas Based on Effectiveness and Justice Criteria: A Qualitative Study with Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Coding. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8734. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198734

Orozco-Ospino J, Florez-Yepes G, Diaz-Muegue L. Governance of Protected Areas Based on Effectiveness and Justice Criteria: A Qualitative Study with Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Coding. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8734. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198734

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrozco-Ospino, Javier, Gloria Florez-Yepes, and Luis Diaz-Muegue. 2025. "Governance of Protected Areas Based on Effectiveness and Justice Criteria: A Qualitative Study with Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Coding" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8734. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198734

APA StyleOrozco-Ospino, J., Florez-Yepes, G., & Diaz-Muegue, L. (2025). Governance of Protected Areas Based on Effectiveness and Justice Criteria: A Qualitative Study with Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Coding. Sustainability, 17(19), 8734. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198734