Abstract

In Cameroon’s service industry, where sustainability is increasingly crucial, this study examines how workplace incivility and organizational support influence employees’ pro-environmental work behavior, applying the Conservation of Resources and Self-Determination Theories. A moderated mediation model was tested, with emotional exhaustion and mindfulness as mediators and psychological capital as a moderator. Data from 280 service industry employees were analyzed using SPSS 24 and SmartPLS 4. Workplace incivility reduces pro-environmental behavior through emotional exhaustion, but shows no significant link with mindfulness. Organizational support enhances pro-environmental behavior and reduces exhaustion, though it does not influence mindfulness. Psychological capital does not mitigate the negative impact of incivility on pro-environmental behavior and its positive impact on exhaustion. These results highlight the critical role of supportive workplaces in fostering sustainable behaviors and the buffering role of psychological capital. This study advances the theoretical understanding of employee behavior in service settings and offers practical insights for managers in banking and insurance to promote sustainability by reducing workplace incivility and enhancing support systems, particularly in emerging markets.

1. Introduction

Recent studies highlight the prevalence of workplace incivility (WI), with 66% of over 1000 US workers surveyed reporting experiencing or witnessing incivility or disrespect in the past month, and 57% in the past week [1,2]. These global trends are extremely pertinent to Cameroon’s growing service sector, as industry management and researchers emphasize the importance of putting employee development and well-being first in order to guarantee sectoral success and sustainability [3]. Despite the fact that the service sector generates a significant amount of income and creates jobs [4], it also faces challenging working conditions that raise the possibility of workplace incivility [5]. But, of all the sectors, the service sector is where incivility is most common [6]. Employees’ pro-environmental work behaviors (PEBs), like saving resources and backing green initiatives, are very important for making organizations more sustainable, especially in the service industry. Incivility can diminish discretionary behaviors by exhausting employees’ resources, whereas organizational support amplifies motivation and promotes PEB. For sustainable management, it is therefore both theoretically and practically important to examine PEB in relation to workplace rudeness and organizational support.

In the service industry, where workplace incivility is most common, organizational support (OS) and workplace incivility are important determinants of employees’ pro-environmental behavior (PEB) [6]. Incivility is defined by Andersson and Pearson [7] as “low-intensity disruptive conduct with unclear motives to hurt the target.” These actions are characterized by incivility or disdain and can nevertheless result in physical and psychological injury, even though they are not as severe as bullying [8,9]. Incivility has been connected to disengagement, low service quality, and decreased motivation, making it a global concern across industries. We contend that it has a detrimental effect on workers’ propensity to act in an environmentally friendly manner [10].

Strong organizational support, on the other hand, can empower staff members and improve their pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) [6,11,12]. In addition to offering direct support to improve performance and work–life balance, perceived organizational support through policies, resources, and a culture that promotes environmental responsibility encourages employees to participate in important activities like sustainability [13]. PEB is defined as “actions contributing to environmental conservation, or human activity aimed at protecting natural resources, or at least reducing environmental deterioration” [14]. Examining how incivility and organizational support affect PEB is essential for improving sustainability and employee well-being because the service industry depends heavily on intense employee interactions.

This study looks at how employees’ pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) are impacted by workplace incivility and organizational support. Employees experiencing incivility may disengage, reduce effort, remain silent, or neglect responsibilities, whereas organizational support encourages engagement in PEB. To investigate these connections, the study makes use of the ideas of Self-Determination and Conservation of Resources. Incivility’s detrimental consequences on burnout, turnover intention, and job performance have been the subject of much research [14,15,16,17]. But its implications on PEB have received less attention [18]. Research on incivility has been conducted in South Korea [19], China [18,20,21,22,23], and India [16], but there is a dearth of studies conducted in African contexts, especially Cameroon. The necessity to comprehend how workplace dynamics impact sustainability-oriented behaviors in this setting is underscored by Cameroon’s collectivist culture and the expansion of the service sector [24].

Employees’ voluntary efforts to conserve energy, cut waste, and encourage eco-friendly behaviors support both the organization’s sustainability goals and the larger environmental goals of society. As pro-environmental work behavior (PEWB) directly affects sustainability results and the workplace administration of resources, it has grown in significance in organizational research. Few studies have looked at how incivility and organizational support affect PEWB, especially in Cameroon’s service sector, despite a wealth of research on these topics. By concentrating on PEWB, this study can fill a theoretical knowledge gap regarding how organizational and interpersonal factors influence environmentally conscious behaviors at work, as well as a practical need for sustainable organizational practices.

However, the importance of studying workplace dynamics is highlighted by Cameroon’s expanding service sector, which grew from 44.3% to 51.9% of the GDP between 2000 and 2023 [25]. Workplace incivility can have a big impact on organizational outcomes, especially pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), because the industry depends so heavily on employee interactions. This study uses the theories of Conservation of Resources (COR) [26] and the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [27].

Therefore, this study examines the ways in which emotional tiredness and mindfulness mediate workplace incivility, organizational support, and PEB. Furthermore, psychological capital is investigated as a mediator in the connections between emotional tiredness, PEB, and rudeness. The approach describes the metrics used to operationalize constructs, data collection, and participants. The findings add to the body of literature by elucidating the relationship between PEB, organizational support, and incivility in Cameroon’s service industry. They also highlight psychological capital as a moderator and emotional weariness as a mediator. Strategies to lessen incivility and encourage sustainable practices are examples of practical consequences. Sections on the theoretical underpinnings, methods, results, discussion, limits, and future research directions make up the study’s framework.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

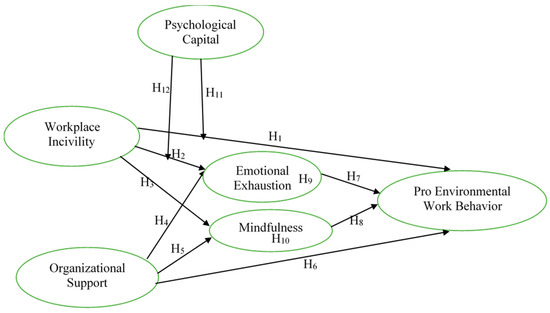

This study explores the relationship between workplace incivility (WI), organizational support (OS), and employees’ pro-environmental work behavior (PEB), mediated by emotional exhaustion (EE) and mindfulness (MF). We suggest that, as seen in Figure 1, psychological capital (PC) will moderate the association between WI and employee PEB, as well as the relationship between WI and EE. We hypothesized that people who practice mindfulness regularly could feel less worn out by incivility, but this was not supported by our results. We also hypothesized that those with a high level of PC will also be less affected by the incivility. Our model is grounded in COR and SDT.

Figure 1.

Research framework. Source: survey data (2025).

According to Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, individuals work to preserve their current resources (conservation) and acquire new resources (acquisition), which might be tangible or psychological [26]. Incivility as a stressor depletes employees’ psychological resources and increases EE, which reveals a perceived threat to individual resources [28], thereby reducing their willingness to engage in PEB.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) explains how autonomy, competence, and relatedness lead to intrinsic motivation [27]. Organizational support (OS) addresses these needs by providing connection, recognition, and empowerment, enhancing pro-environmental work behaviors (PEBs) [29,30]. Therefore, firms that address the psychological needs of their staff members help them feel linked, encouraged, and competent, all of which can boost involvement in sustainability initiatives [31]. On the other hand, an absence of OS could discourage motivation and make workers less inclined to take up ecologically friendly practices [32,33].

2.2. Workplace Incivility, Emotional Exhaustion, Mindfulness, and PEB

Workplace incivility is defined as “low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm the target, in violation of workplace norms for mutual respect” [7]. Unlike bullying, it lacks persistence, but is still harmful. They differ in terms of the desire to do damage, persistence, severity, and kind of norm violation [34]. Also, WI is defined as discourteous or disrespectful behavior that shows a lack of consideration for others and risk factors for uncivil attitudes in working environments [35,36]. Previous studies link WI to EE, poor mental health, and withdrawal behaviors [1,37,38,39].

Recent research has examined the connection between WI and employee pro-environmental behavior (PEB), emphasizing negative effects. All tasks that directly safeguard the environment or enhance organizational procedures are considered PEBs [40]. PEBs can include a variety of practices, such as separating waste for recycling, printing in two-sided mode, or shutting off the lights when leaving the office, which are proactive and task-related behaviors [41,42,43]. The second category includes voluntary actions that go above and beyond the organization’s standards for environmental sustainability and require individual initiative.

For example, Zhang et al. [44] looked at how psychological entitlement can cause workplace deviance, implying that incivility may reduce PEB. Furthermore, in a study carried out by Zahid & Nauman [45], it was shown that WI encouraged deviant behavior and interpersonal conflict, and organizational climate is an important factor in this relationship. In a nutshell, previous studies show that incivility fosters deviance, reduces dignity, and undermines discretionary behaviors such as PEB [46,47,48,49,50].

WI is a significant stressor frequently leading to EE, a central dimension of burnout [39]. For example, a study by Al-Hawari et al. [51] shows that EE mediates WI’s effects on outcomes such as job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and service quality. Parray et al. [52], in the context of higher education, revealed that WI affects job outcomes through EE. And, since mindfulness helps regulate coping, incivility may also reduce employees’ mindfulness, further amplifying its detrimental effects [53], leading to the following hypotheses.

H1.

Workplace incivility is negatively related to employee pro-environmental work behavior.

H2.

Workplace incivility is positively related to emotional exhaustion.

H3.

Workplace incivility is negatively related to employees’ mindfulness.

2.3. Organizational Support, Emotional Exhaustion, Mindfulness, and PEB

Perceived organizational support (POS) reflects employees’ belief that their organizational values and well-being are prioritized [54]. POS mitigates the adverse effects of stressors, replenishes psychological resources, and reduces EE [55,56]. Last but not least, a recent study, carried out by Anggraeni & Febrianti [57], revealed that organizational support, while directly promoting personal preparedness for change, primarily influences adaptive workplace behaviors through the mediating role of mindfulness, a key psychological process.

When employees perceive that their company is supporting them, they will be less likely to suffer from EE. A study of Chinese nurses revealed that higher levels of OS significantly reduced both emotional exhaustion and intentions to leave the organization [58,59,60]. It also promotes PEB by enhancing mindfulness (MF), strengthening organizational commitment, and encouraging voluntary behaviors [61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69]. Based on the above empirical evidence, the following hypotheses were proposed.

H4.

Organizational support is negatively related to emotional exhaustion.

H5.

Organizational support is positively related to employees’ mindfulness.

H6.

Organizational support is positively related to employees’ pro-environmental work behavior.

2.4. Workplace Incivility, Emotional Exhaustion, and PEB

It has been noted that EE reduces various forms of extra-role behavior, such as pro-environmental work behavior (PEB). Recent studies have provided concrete proof in favor of this theory. For example, Karatepe et al. [70] found that emotionally exhausted employees are less engaged in eco-friendly practices, as resource depletion reduces motivation. WI, by draining resources, indirectly reduces PEB through EE.

The COR theory states that rude interactions drain workers’ resources, frequently leading to EE. Coworker incivility drastically raises EE, which in turn results in a fall in organizational outcomes, as Hur et al. [71] showed. The above empirical findings lead to the development of the following hypotheses:

H7.

Emotional exhaustion is negatively related to employees’ pro-environmental work behavior.

H9.

The relationship between workplace incivility and employees’ pro-environmental work behavior will be mediated by emotional exhaustion.

2.5. Organizational Support, Mindfulness, and PEB

It has been demonstrated that mindfulness (MF) enhances ecological awareness and PEB [72]. OS, particularly through sustainability programs, fosters mindfulness and thereby promotes eco-friendly behaviors [73].

OS especially, through programs that support environmental sustainability, is crucial in influencing the psychological states and ensuing the behaviors of workers. According to recent research, one important psychological mechanism by which OS affects workers’ PEB is mindfulness [73]. These results support the idea that employees become more conscious and are encouraged to adopt voluntary, sustainability-focused behaviors when they believe their company strongly supports environmental values.

H8.

Mindfulness is positively related to employees’ pro-environmental work behavior.

H10.

The relationship between organizational support and employees’ pro-environmental work behavior will be mediated by mindfulness.

2.6. Moderating Effect of Psychological Capital

Psychological capital (PC), comprising resilience, optimism, hope, and self-efficacy, buffers the negative impact of WI. Employees with high PC are more capable of managing stress, maintaining engagement, and reducing EE despite incivility [74,75,76,77]. According to these results, workers who score higher on PC are better able to handle the negative consequences of incivility at work, which results in a reduction in EE. As a result, we hypothesize the following:

H11.

Psychological capital moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and employee pro-environmental work behavior such that, when PC is high, the incivility’s impact on reducing PEB is weaker.

H12.

Psychological capital moderates the relationship between workplace incivility and emotional exhaustion such that, when PC is high, the incivility’s impact on increasing emotional exhaustion is weaker.

2.7. Theoretical Contribution

This study advances the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory by showing that workplace incivility depletes employees’ emotional resources, increasing emotional weariness and decreasing pro-environmental behavior (PEB). The findings of this study contribute to COR by demonstrating how this depletion specifically impacts discretionary sustainability-related actions in organizational environments, even though previous research has demonstrated the overall association between incivility and burnout.

This provides a more sophisticated interpretation of COR, emphasizing how discretionary actions linked to sustainability are especially susceptible to resource depletion. Additionally, the moderating function of psychological capital enhances COR by demonstrating that, although not always, psychological resources at the individual level can operate as a buffer against the negative consequences of incivility, implying boundary restrictions in the way that stressors and personal resources interact.

In a similar vein, this study advances Self-Determination Theory (SDT) by showing that, contrary to what was first thought, organizational support improves PEB mainly through resource replenishment and motivational fulfillment. The findings of the study imply that not all psychological processes, such as mindfulness, transfer into pro-environmental behavior, despite SDT’s emphasis on autonomy, competence, and relatedness as sources of intrinsic motivation. This study refines the applicability of SDT to sustainable behaviors and challenges presumptions in the literature by showing that OS enhances PEB without the mediating influence of mindfulness. This suggests that resources offered by organizations might function more directly, encouraging PEB motivation without necessitating elevated states of mindfulness.

Therefore, the results of this study go beyond SDT by suggesting that contextual support might play a simpler role in promoting pro-environmental behavior than previously thought, highlighting the necessity of distinguishing between psychological processes that affect well-being and those that motivate actions focused on sustainability.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

This study included both frontline staff and back-office employees at various hierarchical levels across selected service businesses in Cameroon. Given the objective of targeting individuals with specific knowledge and experience relevant to the research questions, a judgmental (purposive) sampling method was employed. This non-probability sampling technique allowed the researchers to deliberately select participants based on their presumed ability to provide rich and relevant information. According to Malhotra [78], non-probability sampling may be necessary when a sampling frame is not readily available or when time and budget constraints make probability sampling impractical, although it may limit the generalizability of results. A total of 350 questionnaires were distributed, yielding 330 responses, of which 280 were deemed usable after excluding incomplete responses. This resulted in a response rate of 80%. Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 and SmartPLS 4.

3.2. Procedure

After explaining the objective of the study, the research team received approval from management to distribute the electronic questionnaire. Employees were then approached on a voluntary basis and assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. This assurance was communicated both via email and through a cover letter accompanying the questionnaire. The original questionnaire was drafted in English, translated into French, and then back-translated into English by bilingual scholars to ensure accuracy and consistency [79].

3.3. Measures

The scales used to operationalize the constructs were all retrieved from the existing literature. The seven-item measure of workplace incivility that Cortina et al. [11] created was used to examine the incivility employees had encountered at work over the previous year. The organizational support scale for this study is a nine-item scale adopted from Eisenberger et al. [54]. To measure emotional exhaustion, 8 items adapted from [80] were used, and the mindfulness scale (Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS)) developed by Brown & Ryan [56] was used to measure mindfulness with 15 items. A 12-item scale of the revised version of the Compound Psychological Capital (PsyCap) created by Lorenz et al. [81] was used to examine psychological capital. Pro-environmental work behavior was measured with 16 items taken from the study conducted by Kaiser et al. [82]. Workplace incivility, organizational support, emotional exhaustion, and pro-environmental work behavior were measured based on a five-point Likert scale, while mindfulness and psychological capital were measured based on a six-point Likert scale.

4. Data Analysis

To examine the proposed hypotheses, data analysis was conducted using SmartPLS 4 for measurement and structural model evaluation, while SPSS version 26 was utilized for data cleaning and descriptive statistics.

4.1. Sample Demographic Characteristics

Out of the 350 distributed questionnaires, 330 were returned, representing an initial response rate of 94.3%. After excluding responses with missing or incomplete data, 280 valid responses were retained for analysis, resulting in an effective response rate of 80%. Table 1 presents the demographic profile of the respondents. A slight majority of participants were female (55%), and the largest age group comprised respondents aged 30–39 years (35%). The majority of participants (74.3%) were employed in private sector organizations. Regarding tenure, 45% of respondents reported working with their current organization for 4 to 6 years. In terms of organizational role, 41.1% identified as non-managerial employees.

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of the demographic variables.

4.2. Measurement Model Analysis

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed as a non-parametric analytical approach, given the exploratory nature of the study and following methodological recommendations in the literature [83]. PLS-SEM was deemed appropriate due to the complexity of the proposed model and its several advantages, including flexibility, suitability for small to medium sample sizes, ability to handle non-normal data distributions, and robustness in estimating complex relationships [84]. The PLS algorithm was used to estimate both the measurement and structural models. Hypothesis testing was conducted through bootstrapping procedures. Prior to assessing the structural model, the measurement model (Figure 2) was evaluated to establish the reliability and validity of the constructs under investigation.

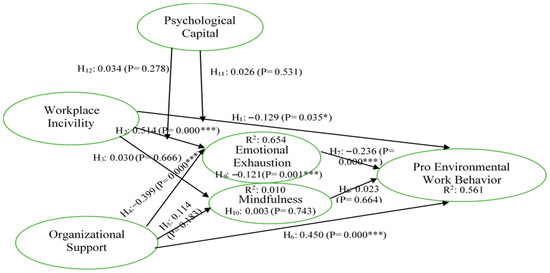

Figure 2.

Structural equation model; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001. Source: survey data (2025).

To evaluate the measurement model, we looked at convergent validity (outer loadings), average variance extracted (AVE), discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criterion), and reliability (Cronbach α, composite reliability) [83]. The findings are displayed in Table 2 and Table 3. The measurement model had high reliability because all of the latent variables’ Cronbach α values were above 0.70 [84,85], and also rho_a (average inter-item correlation) and composite reliability (rho_c) all exceeded the acceptable threshold of 0.70 [86]. Convergent validity was assessed using AVE values. The values were above the recommended threshold of 0.50, according to the results [87].

Table 2.

Construct validity and reliability test.

Table 3.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) discriminant validity result.

Table 2 shows that every indicator accurately reflects its underlying construct, with all factor loadings exceeding 0.7 [88]. On the other hand, some observed (PEB1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, and 16; EE9; MF1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15; and PC4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12) were eliminated because their outer loadings were less than 0.7, which had an impact on the average variance extracted and composite reliability [89].

According to Table 3, all of the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) values were less than 0.90 [90], indicating that the criteria from this criterion were met. In general, there was no issue with discriminant validity.

Table 4 shows the results of applying the Fornell–Larcker criterion to evaluate the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) against the correlations between the constructs [87]. The findings show that, whether analyzed vertically or horizontally in the table, the square root of AVE for each construct is greater than its correlations with other constructs. This demonstrates the discriminant validity of the study’s constructs, which means that each one is unique and does not overlap.

Table 4.

Fornell–Larcker criterion discriminant validity result.

4.3. Structural Model and Critical Findings

Up until now, the validity and dependability of the structural model had been assessed, and encouraging findings had been noted. The predicted hypotheses can therefore be examined at this time [83]. A structural model is used to depict the theoretical model’s proposed paths. Three important criteria which are path significance, R2, and Q2, will be examined in order to evaluate this model. Table 5 shows that, with the exception of mindfulness (MF), which is less than 0.1, all R2 values are above this cutoff, indicating predictions. This suggests that MF is not significantly predicted by the two independent variables, WI and OS. On the other hand, the R2 for EE is 0.654, indicating that WI and OS account for 65.4% of the variance in EE. According to Figure 2, the R2 for PEB is 0.561, meaning that EE and WI account for 56.1% of the variance in PEB.

Table 5.

Direct relationship analysis result.

Additionally, Q2 determines the dependent variables’ predictive relevance. With the exception of mindfulness (MF), which is below zero, Table 5 demonstrates that Q2 values are above zero for the majority of variables, indicating predictive significance. Both pro-environmental behavior (PEB) and emotional exhaustion (EE) exhibit predictive relevance, with Q2 values of 0.645 and 0.525, respectively. Examining the suggested hypotheses to verify relationship relevance is another step in determining the model’s goodness of fit.

The direct relationships were analyzed in Table 5. H1 and H2 were supported, where there is a significant negative relationship between workplace incivility and employee pro-environmental behavior (β = −0.129, t = 2.112, p = 0.035) and a significant positive relationship between workplace incivility and emotional exhaustion technology perceived as demand and job engagement (β = 0.514, t = 10.533, p = 0.000). H3 is not supported, as workplace incivility does not influence mindfulness negatively, with β = 0.030, t = 0.431, and p = 0.666.

In addition, the results reveal that organizational support is negatively related to emotional exhaustion (β= −0.399, t = 9.698, p = 0.000) and positively related to pro-environmental behavior (β= 0.450, t = 6.963, p = 0.000), thereby supporting H4 and H6, respectively. Similarly, the outcome shows that organizational support is not positively related to employees’ mindfulness, as the β = 0.114, t = 1.333, and p = 0.183, leading to H5 being unsupported.

Furthermore, H7 proves a negative relation between emotional exhaustion and pro-environmental behavior as β = −0.236, t = 3.490, and p = 0.000, and H8 reveals that mindfulness does not positively influence pro-environmental behavior (β = 0.023, t = 0.435, and p = 0.664); as a result, H7 is supported and H8 is not supported.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

The study employed a mediation analysis to investigate the mediating functions of emotional exhaustion (EE) and mindfulness (MF), as displayed in Table 6. H9 shows that EE mediates the relationship between incivility (WI) and pro-environmental behavior (PEB) (β = −0.121, t = 3.438, and p = 0.001). This means the negative effect of WI on PEB happens through EE. More incivility leads to exhaustion, which in turn reduces engagement in environmental friendly activities, supporting H9. Conversely, H10 reveals that mindfulness (MF) does not mediate the relationship between organizational support (OS) and pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) (β = 0.003, t = 0.328, and p = 0.743), meaning OS does not affect PEB through MF; as a result, H10 is not supported.

Table 6.

Mediation analysis result.

4.5. Moderation Analysis

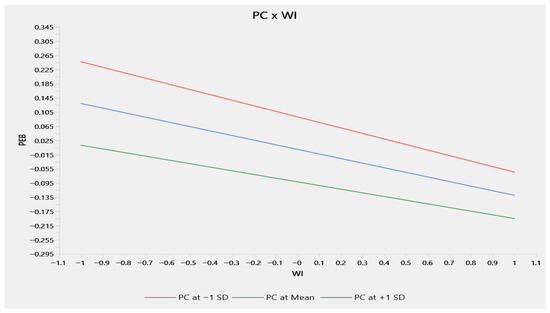

In Table 7, we test the moderating effect of psychological capital (PC) on the relationship between incivility (WI) and the outcomes of pro-environmental behavior (PEB) and emotional exhaustion (EE), respectively. The result reveals that PC does not moderate the relationship between WI and PEB (β = 0.026, t = 0.626, and p = 0.531), meaning that a worker possessing more PC attributes of optimism, resilience, hope, and self-efficacy may not mitigate the negative effect of WI on PEB (see Figure 3), thus not supporting H11.

Table 7.

Moderation analysis result.

Figure 3.

Simple slope analysis_ PC × WI → PEB. Source: survey data (2025).

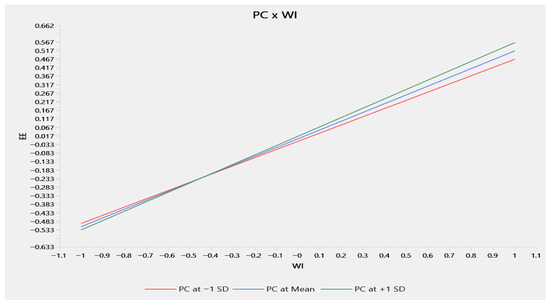

Similarly, PC does not moderate the relationship between WI and EE (β = 0.034, t = 1.084, and p = 0.278). This result means that, regardless of an employee’s PC score, incivility still causes exhaustion at the same level. This implies that a higher PC has little effect on the relationship between WI and EE (see Figure 4), thus not supporting H12.

Figure 4.

Simple slope analysis_ PC × WI → EE. Source: survey data (2025).

Figure 3 and Figure 4 match the moderation results for hypotheses 11 and 12, respectively. With regard to Figure 3, the slope shows that psychological capital does not reduce the detrimental impact of workplace incivility on pro-environmental behavior both at low and high psychological capital. And, in Figure 4, psychological capital does not guard against the positive connection between incivility and emotional exhaustion. This is because the effect stays the same no matter how much psychological capital someone has.

5. Discussion

This research focused on assessing the effects that workplace incivility and organizational support have on pro-environmental work behavior, and the roles emotional exhaustion, mindfulness, and psychological capital play in these relationships. The results of this study are examined in the paragraphs that follow within the theoretical frameworks of Conservation of Resources and Self-Determination.

WI was strongly linked to higher EE and lower PEB, indicating that it has a negative impact on both emotional well-being and long-term workplace behavior [91], thereby supporting H1 and H2. This outcome is in line with findings from earlier research by Sliter et al. [92], who suggest that incivility at work leads to emotional strain, and Kim et al. [93], who assert that incivility and other toxic workplace environments weaken organizational identification, which in turn weakens voluntary behaviors like PEB.

OS had a negative correlation with EE and a positive effect on PEB, thereby supporting H4 and H6 respectively. This suggests that job resources, such as support, can reduce stress and encourage constructive behavior. This is consistent with the results of Jawahar et al. [94], Paillé et al. [95], and Norton et al. [43].

In addition, the study discovered that EE negatively affects PEB, supporting H7. This result is in line with the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, which holds that workers are less likely to participate in environmentally friendly activities when they are exhausted because their resources are depleted. This finding is consistent with that of Karatepe et al. [96] and Yuan et al. [97], who all discovered that an increase in exhaustion will reduce involvement in environmental behaviors.

It is interesting to note that neither WI and OS influenced MF. WI did not affect MF negatively and OS did not significantly lead to MF, thereby not supporting H3 and H5, respectively. Regarding previous inconclusive results, environmental behavior might not be directly affected by mindfulness, despite its value in psychological settings [98].

Meanwhile, MF did not positively affect PEB, leading to H8 being unsupported. This is in line with Corbi et al. [99], who discovered that MF reduces involvement in environmental behavior.

Contrary to expectations, MF was not found to mediate the OS and PEB relationship, rejecting H10. This supports the findings of Good et al. [100]. Similarly, EE significantly mediates the relationship between WI and PEB, which implies that H9 was supported and is consistent with the findings of Fida et al. [1].

The adverse impact of WI on PEB is not mitigated by PC, which does not support H11. This implies that workers with a high PC may not have the willingness to participate in PEB, even when there is incivility. This outcome is not consistent with Butt & Yazdani [75].

Important questions are raised by these non-significant findings. The mediation role of psychological capital may be diminished in cultural or organizational environments when pro-environmental behavior is viewed as a shared responsibility rather than an individual reaction to stressors. As an alternative, psychological capital and mindfulness might have an impact on outcomes other than PEB in this context, such as stress reduction or interpersonal relationships, which were not the main focus of this study.

Another reason might be that workers who experience rudeness give priority to coping strategies unrelated to environmental initiatives, suggesting that pro-environmental involvement is influenced by larger contextual or motivating variables. These results underline the necessity of further studies looking into organizational environment, cultural norms, and other mediating factors that could be able to better explain the dynamics that have been seen.

Remarkably, the positive impact of WI on EE was not also mediated by PC, rejecting H12. In other words, even the most resilient worker will become exhausted due to a persistently rude work environment. This finding is consistent with that of R. P. Kumar et al. [101], who found that PC might not always mitigate the negative effects of rudeness on worker outcomes.

The results of this study make significant contributions to the theories used. According to the COR theory, incivility at work has been found to exacerbate emotional exhaustion, illustrating how unfavorable social interactions drain workers’ resources. Employees’ ability to participate in voluntary PEB is restricted by this resource depletion. Organizational support, on the other hand, restores vital resources by fostering a positive environment that lessens stress and increases resilience, allowing staff members to make investments in ecologically conscious practices at work. Based on SDT, the results demonstrate how supportive workplace policies meet workers’ fundamental psychological needs for connections, skills, and independence. Workers are more intrinsically motivated to act in ways that support both organizational and societal sustainability goals whenever such demands are met. Incivility, on the other hand, undercuts these needs, decreasing intrinsic motivation and the probability of pro-environmental involvement.

The present study makes multiple contributions to the body of knowledge. The study contributes to and extends our understanding of the Conservation of Resources (COR). The existing assumptions of the literature that mindfulness increases awareness and unavoidably results in behavioral change are called into question by the lack of predictive power of mindfulness on PEB. By demonstrating the gradual impact of resource depletion on pro-social behaviors, the confirmation that WI increases EE, which in turn lowers PEB, is consistent with the COR theory. Furthermore, the practical use of positive organizational behavior in the literature is extended by PC’s moderating role on the WI-PEB link, which implies that individual psychological resources can mitigate the detrimental effects of toxic work environments on sustainability initiatives.

As a whole, it was discovered that some anticipated relationships between the variables were not significant, while others were found significant. This is consistent with earlier research. We speculate that these discrepancies could be explained by the social viewpoints of the local population, labor market circumstances, and cultural differences. As a result, this study adds to the body of literature by emphasizing that, even after looking at these significant variables, there are still more important ones that need to be investigated in future studies.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Conclusion

The study emphasizes how employees’ PEB is influenced by WI, OS, EE, and PC. According to the Conservation of Resources theory, it was demonstrated that incivility reduced PEB by depleting resources and increasing exhaustion, whereas OS restored resources and encouraged sustainable practices. Because favorable settings increased the intrinsic motivation for pro-environmental actions, the Self-Determination Theory was also validated. Remarkably, psychological capital mitigated the detrimental effects of incivility on PEB, while mindfulness neither directly predicted nor mediated PEB, refuting widespread beliefs about its universal influence. These results broaden our theoretical knowledge by elucidating the resource-based and motivational mechanisms underlying PEB, while offering useful advice for businesses looking to create resilient, encouraging, and sustainability-focused work environments.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

The present study makes multiple contributions to the body of knowledge. Thanks to this study, the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory is developed theoretically. The literature assumption that mindfulness increases awareness, unavoidably resulting in behavioral change, is called into question by the lack of predictive power of mindfulness on PEB. By demonstrating the gradual impact of resource depletion on pro-social behaviors, the confirmation that WI increases EE, which in turn lowers PEB, is consistent with the COR theory. Furthermore, the practical use of positive organizational behavior in the literature is extended by PC’s moderating role on the WI-PEB link, which implies that individual psychological resources can mitigate the detrimental effects of toxic work environments on sustainability initiatives.

6.3. Managerial Implications

Managers may establish zero-tolerance rules against incivility and cultivate a respectful and psychologically safe environment as an outcome of this study. This can be accomplished by fostering a polite and encouraging workplace. Additionally, by prioritizing a supportive workplace, companies can create and offer concrete assistance like wellness initiatives and mental health services. Additionally, companies should provide training and development initiatives that boost workers’ self-efficacy, optimism, resilience, and hope, as these traits can act as a buffer against harmful workplace influences and encourage long-term participation in environmentally friendly practices.

6.4. Practical Policy Recommendations

Customized mindfulness programs may improve employee well-being and indirectly support sustainability goals, even though mindfulness did not directly influence pro-environmental behavior (PEB). There should be policies that encourage the hiring, educating, and rewarding of staff members according to sustainability principles, and, by incorporating environmentally friendly duties into job descriptions, organizations can embrace green human resource management. In addition, policies that encourage regular evaluations of the organizational climate, in particular the degree of EE, OS, and WI, can also aid in improving workplace regulations and directing the strategic use of resources.

Furthermore, this study has substantial ramifications for managers and policymakers in emerging countries. An employee’s behavior is greatly influenced by workplace culture, and organizational resources are frequently limited. Therefore, managers should place a high priority on creating polite and encouraging work cultures, since it has been shown that workplace incivility increases emotional weariness and decreases pro-environmental behavior.

It is imperative for managers to include the establishment of anti-incivility regulations, providing training courses on polite workplace conduct and setting up easily accessible methods for reporting problematic behavior.

Additionally, as organizational support has been identified as a major motivator for pro-environmental behavior, businesses can improve procedures including resource provision, open communication, and recognition programs that enable staff members to support environmental sustainability. Even modest interventions, like encouraging teamwork, giving flexible work schedules, or delivering symbolic prizes for green projects, can have a disproportionately favorable effect on employee participation in sustainable practices in settings with low resources.

From the standpoint of policy, the study emphasizes how important it is for industry groups and regulators in emerging countries to create standards that encourage organizational support systems and stress environmental stewardship as a component of workplace culture. Legislators could provide tax breaks, sustainability certifications, or public recognition programs as incentives to companies that exhibit a dedication to environmental performance and worker well-being.

Furthermore, the non-significant findings for psychological capital and mindfulness imply that methods depending only on individual-level interventions may not produce reliable effects. Organizations in emerging markets should instead embrace system-level strategies that include industry standards, labor practices, and cultural values within sustainability projects. By treating pro-environmental behavior as a group organizational obligation rather than an individual option, this more comprehensive approach would increase the possibility of long-term, sustainable change.

6.5. Study Limitations and Recommendations

It is important to highlight the study’s limitations. First, even with the statistical tests and procedural adjustments employed in this study, self-report measures may still result in common method variance. Secondly, our study’s cross-sectional design fails to show the causal relationship that may exist in a delayed period between incivility and exhaustion. In addition, since we only looked at the insurance and banking companies within the service industry and concentrated on a little-researched area of the literature, the study’s findings cannot be applied to the entire industry.

This study may open up a number of research directions. First, future studies that wish to duplicate this work might think about using a longitudinal research design. This can account for the causal role that time will play in this relationship and significantly lower the variance of the common method. In order to fully understand the industry and make significant contributions to the literature, future research in this area should be carried out in different regions, service industry types, and cultural contexts. Third, we suggest expanding this model to include additional predictor variables such as green organizational culture, leadership style, and job demands.

Additionally, the goal of this study was to select personnel with certain expertise and experience; therefore, the purposive (judgmental) sample technique was employed. However, it necessarily limits the findings’ generalizability. The results might not accurately reflect the experiences of workers in other industries, geographical areas, or cultural contexts because participants were specifically chosen from Cameroonian service companies. This restriction implies that care should be taken when extrapolating the findings outside of the population under study. Future research could replicate the study using probability-based sampling procedures or by using larger and more diverse samples from various sectors and nations in order to allay this concern. Such initiatives would improve external validity and offer a more thorough comprehension of the ways in which organizational support, psychological resources, and workplace incivility impact pro-environmental behavior in a variety of organizational and cultural contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, visualization, W.S.D.; supervision, C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study titled “Assessing The Impact of Workplace Incivility and Organizational Support On Employees’ Pro-Environmental Work Behavior in Service Industry: A Moderated Mediation Model”, conducted by PhD student WAMBA SYNTICHE DONGMO (Student ID: 22209536), under the supervision of Prof. Dr. Cem TANOVA, was unanimously approved by the Cyprus International University (CIU) Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee during its meeting held on 28 May 2025, with decision number EKK24-25/12/018.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| COR | Conservation of Resources Theory |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| EE | Emotional Exhaustion |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GHRM | Green Human Resource Management |

| MF | Mindfulness |

| OS | Organizational Support |

| PC | Psychological Capital |

| PEB | Pro-Environmental Behavior |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| PsyCap | Psychological Capital |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| WI | Workplace Incivility |

References

- Fida, R.; Laschinger, H.K.S.; Leiter, M.P. The protective role of self-efficacy against workplace incivility and burnout in nursing: A time-lagged study. Health Care Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, M. Workplace Emotions. In Emotional Intelligence for Students, Parents, Teachers and School Leaders; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 191–218. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-19-0324-3_9 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Rivera, M.A. The synergies between human development, economic growth, and tourism within a developing country: An empirical model for Ecuador. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alola, U.V.; Alola, A.A.; Avci, T.; Ozturen, A. Impact of Corruption and Insurgency on Tourism Performance: A Case of a Developing Country. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2021, 22, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anasori, E.; Bayighomog, S.W.; Tanova, C. Workplace bullying, psychological distress, resilience, mindfulness, and emotional exhaustion. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namin, B.H.; Øgaard, T.; Røislien, J. Workplace incivility and turnover intention in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L.M.; Pearson, C.M. Tit for Tat? The Spiraling Effect of Incivility in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.A.; Kim, K. Dealing with customer incivility: The effects of managerial support on employee psychological well-being and quality-of-life. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukis, A.; Koritos, C.; Daunt, K.L.; Papastathopoulos, A. Effects of customer incivility on frontline employees and the moderating role of supervisor leadership style. Tour. Manag. 2020, 77, 103997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhan, J.; Cheng, B.; Scott, N. Frontline employee anger in response to customer incivility: Antecedents and consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 96, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L.M.; Magley, V.J.; Williams, J.H.; Langhout, R.D. Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2001, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reio, T.G.; Ghosh, R. Antecedents and outcomes of workplace incivility: Implications for human resource development research and practice. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2009, 20, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ausat, A.M.A. The role of social media in shaping public opinion and its influence on economic decisions. Technol. Soc. Perspect. TACIT 2023, 1, 35–44. Available online: https://journal.literasisainsnusantara.com/index.php/tacit/article/view/37 (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Nájera, M.; Rivera-Martínez, J.G.; Hafkamp, W.A. An explorative socio-psychological model for determining sustainable behavior: Pilot study in German and Mexican Universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifulina, N.; Carballo-Penela, A.; Ruzo-Sanmartin, E. The antecedents of employees’ voluntary proenvironmental behavior at work in developing countries: The role of employee affective commitment and organizational support. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2021, 4, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, V.; Sreejesh, S. Co-worker and customer incivility on employee well-being: Roles of helplessness, social support at work and psychological detachment-a study among frontline hotel employees. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Mejía-Morelos, J.H. Antecedents of pro-environmental behaviours at work: The moderating influence of psychological contract breach. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ones, D.S.; Dilchert, S. Environmental sustainability at work: A call to action. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 5, 444–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. Is political skill really an antidote in the workplace incivility-emotional exhaustion and outcome relationship in the hotel industry? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, A.; Cosby, D.M. A model of workplace incivility, job burnout, turnover intentions, and job performance. J. Manag. Dev. 2016, 35, 1255–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, P.L. The relationship among faculty-to-faculty incivility and job satisfaction or intent to leave in nursing programs in the United States. J. Prof. Nurs. 2023, 47, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sguera, F.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Huy, Q.N.; Boss, R.W.; Boss, D.S. Curtailing the harmful effects of workplace incivility: The role of structural demands and organization-provided resources. J. Vocat. Behav. 2016, 95, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Mao, J.Y. Negative role modeling in hospitality organizations: A social learning perspective on supervisor and subordinate customer-targeted incivility. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 102, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsahlai, L.K.; Constantine, K.; Simon Pierre, P.N. Associating Poverty with Gender-Based Violence (GBV) Against Rural and Poor Urban Women (RPUW) in Cameroon. In Global Perspectives on Health Geography; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 257–278. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-031-41268-4_13 (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- African Union Commission. Africa’s Development Dynamics 2023 Investing in Sustainable Development: Investing in Sustainable Development; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manninen, M.; Dishman, R.; Hwang, Y.; Magrum, E.; Deng, Y.; Yli-Piipari, S. Self-determination theory based instructional interventions and motivational regulations in organized physical activity: A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2022, 62, 102248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, G.; Oades, L. Coaching with self-determination theory in mind: Using theory to advance evidence-based coaching practice. Int. J. Evid.-Based Coach. Mentor. 2011, 9, 37–55. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/articles/journal_contribution/Coaching_with_self-determination_theory_in_mind_Using_theory_to_advance_evidence-based_coaching_practice/27712887 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Baxter, D.; Pelletier, L.G. The roles of motivation and goals on sustainable behaviour in a resource dilemma: A self-determination theory perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permata, F.D.; Mangundjaya, W.L. The role of work engagement in the relationship of job autonomy and proactive work behavior for organizational sustainability. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; p. 012055. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1755-1315/716/1/012055/meta (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Sheoran, N.; Goyal, R.; Sharma, H. Do Job Autonomy Influence Employee Engagement? Examining the Mediating Role of Employee Voice in the Indian Service Sector. Metamorph. J. Manag. Res. 2022, 21, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, C.M.; Andersson, L.M.; Porath, C.L. Workplace incivility. In Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Qiu, Y.; Gan, Y. Workplace Incivility and Work Engagement: The Chain Mediating Effects of Perceived Insider Status, Affective Organizational Commitment and Organizational Identification. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 1809–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, V.Y.; Pun, P.Y. The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion and Job Satisfaction on the Relationship Between Job Demands and Instigated Workplace Incivility. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2018, 54, 187–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. Improving frontline service employees’ innovative behavior using conflict management in the hospitality industry: The mediating role of engagement. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, G.; Mancuso, S.; Fiz Perez, F.; Castiello D’Antonio, A.; Mucci, N.; Cupelli, V.; Arcangeli, G. Bullying among nurses and its relationship with burnout and organizational climate. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2016, 22, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1997-09146-011 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Boiral, O.; Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. The nature of employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. In Psychology of Green Organizations; Oxford Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 12–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cantor, D.E.; Morrow, P.C.; Blackhurst, J. An Examination of How Supervisors Influence Their Subordinates to Engage in Environmental Behaviors. Decis. Sci. 2015, 46, 697–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, B.B.; Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.A.; Zacher, H.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Organisational sustainability policies and employee green behaviour: The mediating role of work climate perceptions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 38, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Feng, T. Why good employees do bad things: The link between pro-environmental behavior and workplace deviance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, A.; Nauman, S. Does workplace incivility spur deviant behaviors: Roles of interpersonal conflict and organizational climate. Pers. Rev. 2024, 53, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welbourne, J.L.; Sariol, A.M. When does incivility lead to counterproductive work behavior? Roles of job involvement, task interdependence, and gender. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R. Workplace incivility in Asia-how do we take a socio-cultural perspective? Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. Taylor Fr. 2017, 20, 263–267. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13678868.2017.1336692 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Handoyo, S.; Samian, S.; Syarifah, D.; Suhariadi, F. The measurement of workplace incivility in Indonesia: Evidence and construct validity. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2018, 11, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, W.M.; Shin, Y.; Yingrui, S. When and why job-insecure flight attendants are reluctant to behave pro-environmentally. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B.S.; El-Sisi, S. Does workplace incivility affect travel agency performance through innovation, organizational citizenship behaviors, and organizational commitment? Tour. Rev. 2024, 79, 1474–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawari, M.A.; Bani-Melhem, S.; Quratulain, S. Do Frontline Employees Cope Effectively with Abusive Supervision and Customer Incivility? Testing the Effect of Employee Resilience. J. Bus. Psychol. 2020, 35, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parray, Z.A.; Islam, S.U.; Shah, T.A. Impact of workplace incivility and emotional exhaustion on job outcomes–a study of the higher education sector. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 1024–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynova, G.; İslamoğlu, M. Mind over matter: Mindfulness as a buffer against workplace incivility. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1409326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Huntington, R.; Hutchison, S.; Sowa, D. Perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 1986, 71, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.K.; Liu, Q.Q.; Niu, G.F.; Sun, X.J.; Fan, C.Y. Bullying victimization and depression in Chinese children: A moderated mediation model of resilience and mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. Mindful attention awareness scale. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/t04259-000 (accessed on 26 May 2025).

- Anggraeni, W.; Febrianti, A.M. Managing individual readiness for change: The role of mindfulness and perceived organizational support. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, R.; Armeli, S.; Rexwinkel, B.; Lynch, P.D.; Rhoades, L. Reciprocation of perceived organizational support. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhao, S.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, L.I.; Duan, X.; Li, G.; Lou, F.; Jia, X.; et al. Workplace violence, job satisfaction, burnout, perceived organisational support and their effects on turnover intention among Chinese nurses in tertiary hospitals: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e019525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowe, M.A.; Prapanjaroensin, A.; Bakitas, M.A.; Hites, L.; Loan, L.A.; Raju, D.; Patrician, P.A. An exploratory study of the influence of perceived organizational support, coworker social support, the nursing practice environment, and nurse demographics on burnout in palliative care nurses. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2020, 22, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitão, P.; Mouro, C.; Duarte, A.P.; Luís, S. Promoting pro-environmental behaviours at work: The role of green organizational climate and supervisor support/Fomentando las conductas proambientales en el trabajo: El papel del clima organizacional verde y el apoyo del supervisor. PsyEcology Biling. J. Env. Psychol. 2024, 15, 163–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.L.; Barling, J. The role of leadership in promoting workplace pro-environmental behaviors. In Psychology of Green Organizations; Oxford Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 164–186. [Google Scholar]

- Yuriev, A.; Boiral, O.; Francoeur, V.; Paillé, P. Overcoming the barriers to pro-environmental behaviors in the workplace: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluss, D.M.; Ashforth, B.E. How Relational and Organizational Identification Converge: Processes and Conditions. Organ. Sci. 2008, 19, 807–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. Handb. Social. Theory Res. 1969, 213, 262. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Stinglhamber, F.; Vandenberghe, C.; Sucharski, I.L.; Rhoades, L. Perceived supervisor support: Contributions to perceived organizational support and employee retention. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luís, S.; Silva, I. Humanizing sustainability in organizations: A place for workers’ perceptions and behaviors in sustainability indexes? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 18, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyankara, H.P.R.; Luo, F.; Saeed, A.; Nubuor, S.A.; Jayasuriya, M.P.F. How does leader’s support for environment promote organizational citizenship behaviour for environment? A multi-theory perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Hassannia, R.; Karatepe, T.; Enea, C.; Rezapouraghdam, H. The Effects of Job Insecurity, Emotional Exhaustion, and Met Expectations on Hotel Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behaviors: Test of a Serial Mediation Model. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 2023, 25, 287–307. Available online: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl=14623730&AN=161916485&h=CCHO%2BngSaoENVBTdsePe7e3W1Kdbc1gpjIYmOBCsqgc6k9Cx2%2B8OYjmip9NLb%2FzgMlsEgdF2IroKMjrtwr7NjQ%3D%3D&crl=c (accessed on 2 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.; Kim, B.; Park, S. The Relationship between Coworker Incivility, Emotional Exhaustion, and Organizational Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Ind. 2015, 25, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Panda, T.K.; Pandey, K.K. Mindfulness at the workplace: An approach to promote employees pro-environmental behaviour. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y. Enhancing Pro-Environmental Behavior Through Green HRM: Mediating Roles of Green Mindfulness and Knowledge Sharing for Sustainable Outcomes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, I.; Sattar, H.; Raja, U.; Azeem, M.U. Workplace Incivility and Job Performance: The Role of Anxiety and Psychological Capital. Acad. Manag. Proc 2020, 2020, 12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, S.; Yazdani, N. Influence of workplace incivility on counterproductive work behavior: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion, organizational cynicism and the moderating role of psychological capital. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. PJCSS 2021, 15, 378–404. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Ma, J.; Chen, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhou, H.; Gong, A.; Peng, F.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Xiong, X.; et al. The moderating effect of psychological capital on the relationship between nurses’ perceived workplace bullying and emotional exhaustion: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetteh, S. Incivility and engagement: The role of emotional exhaustion and psychological capital in service organizations. Learn. Organ. 2024, 31, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Prientation; Pearson: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McGorry, S.Y. Measurement in a cross-cultural environment: Survey translation issues. Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2000, 3, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, T.; Hagitte, L.; Prasath, P.R. Validation of the revised Compound PsyCap Scale (CPC-12R) and its measurement invariance across the US and Germany. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1075031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Oerke, B.; Bogner, F.X. Behavior-based environmental attitude: Development of an instrument for adolescents. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; MacGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinzi, V.E.; Chin, W.W.; Henseler, J.; Wang, H. Editorial: Perspectives on Partial Least Squares. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Esposito Vinzi, V., Chin, W.W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 1–20. Available online: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-540-32827-8_1 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Hair Jnr, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.; Pearson, C. The price of incivility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2013, 91, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sliter, M.; Sliter, K.; Jex, S. The employee as a punching bag: The effect of multiple sources of incivility on employee withdrawal behavior and sales performance. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I.M.; Stone, T.H.; Kisamore, J.L. Role conflict and burnout: The direct and moderating effects of political skill and perceived organizational support on burnout dimensions. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. Linking perceived corporate environmental policies and employees eco-initiatives: The influence of perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatepe, O.M.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Hassannia, R. Sense of calling, emotional exhaustion and their effects on hotel employees’ green and non-green work outcomes. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 3705–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Ren, S.; Haochen, J.; Tang, G. Commitment or Exhaustion? Effects of Green Human Resource Management on Employee Green Behavior. Acad. Manag. 2021, 2021, 12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reb, J.; Narayanan, J.; Ho, Z.W. Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness 2015, 6, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbi, Z.L.H.; Koch, K.; Hölzel, B.; Soutschek, A. Mindfulness Training Reduces the Preference for Sustainable Outcomes 2024. Available online: https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-3994334/latest (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Good, D.J.; Lyddy, C.J.; Glomb, T.M.; Bono, J.E.; Brown, K.W.; Duffy, M.K.; Baer, R.A.; Brewer, J.A.; Lazar, S.W. Contemplating Mindfulness at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 114–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.P.; Chandrahasa, R.; Shashidhar, R. Does Workplace Incivility Undermine the Potential of Job Resources? The Role of Psychological Capital. FIIB Bus. Rev. 2023, 23197145221137963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).