The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.2. Research Questions

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. ESG Management

2.2. ESG and Consumer Behavior

2.3. Brand Value

2.4. Perceived Quality

2.5. Corporate Trust

2.6. Purchase Intention

3. Research Design

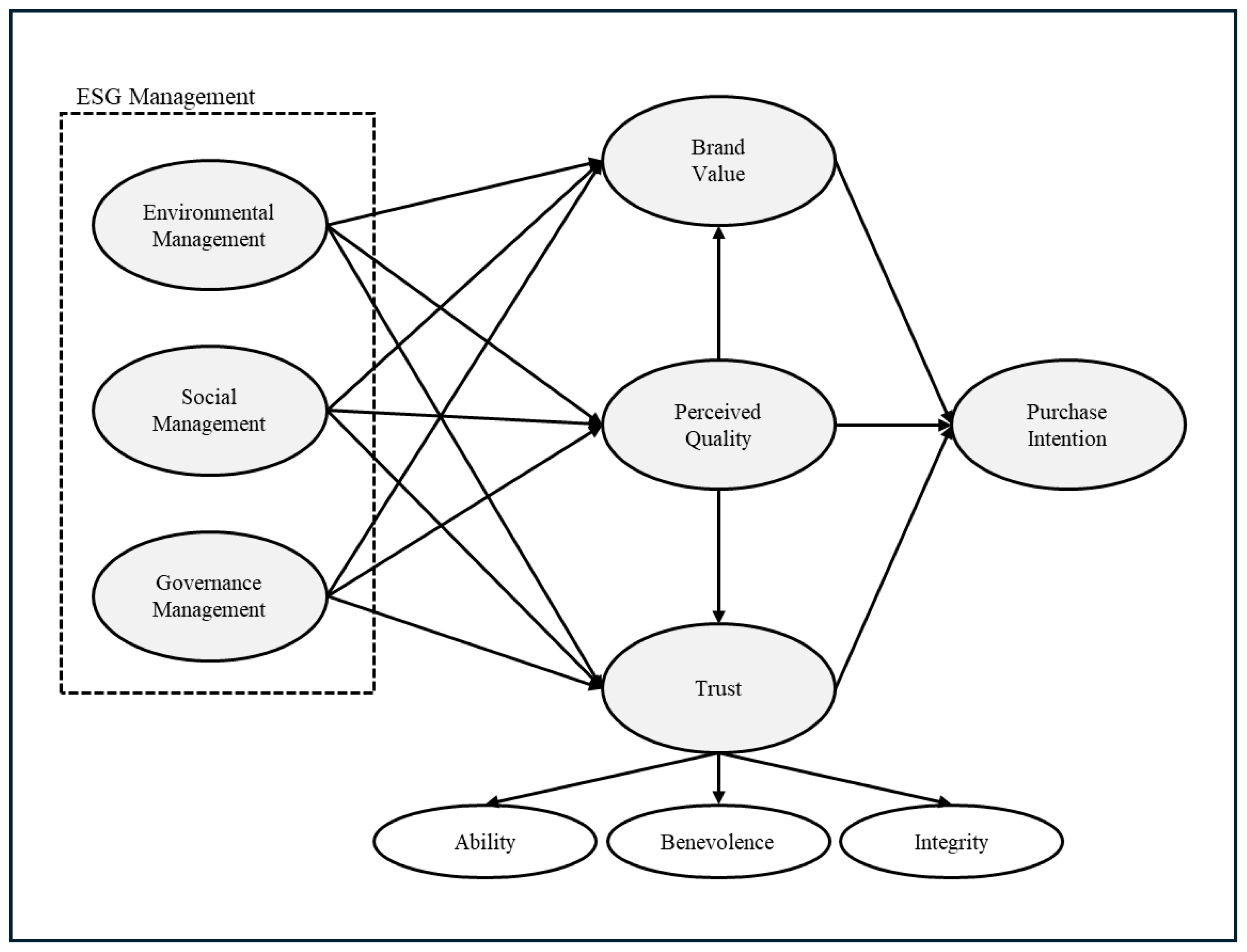

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Hypotheses Development

3.2.1. ESG Management and Brand Value

3.2.2. ESG Management and Perceived Quality

3.2.3. ESG Management and Trust

3.2.4. Perceived Quality and Brand Value

3.2.5. Perceived Quality and Trust

3.2.6. Brand Value and Purchase Intention

3.2.7. Perceived Quality and Purchase Intention

3.2.8. Trust and Purchase Intention

3.3. Operational Definitions of the Variables

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Research Design and Data Analysis

4.2. Data Collection and Sample Characteristics

4.3. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Trust Second-Order Measurement

4.4. Evaluation of the Research Model

4.5. Common Method Bias (CMB) Test in PLS

4.6. Path Analysis and Hypothesis-Testing Results

4.7. Verification of Potential Bias Between Vehicle Ownership Groups

5. Results

5.1. Research Findings

5.2. Implications

5.2.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

5.4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Survey Measurement

- Environment Management

- This company seems to plan and practice environmental protection.

- This company seems to pursue environmentally conscious management.

- This company seems to strive to minimize greenhouse gas emissions.

- This company seems to communicate with customers regarding its environmental management.

- This company seems to have established an evaluation system for its environmental management.

- This company seems to publish reports related to its environmental management.

- Social Management

- This company seems to strive for the development of the local community.

- This company seems to make efforts to support marginalized groups.

- This company seems to conduct activities to protect the human rights of its employees.

- This company seems to support training for employees to enhance their job competencies.

- This company seems to comply with fair trade standards with its partner companies.

- This company seems to strive to protect consumer rights.

- Governance Management

- This company seems to strive to protect shareholder rights.

- This company’s board of directors seems to perform the company’s decision-making and supervisory functions.

- This company’s directors seem to perform their duties based on laws and the articles of incorporation.

- This company seems to appoint an external auditor with independence and expertise.

- This company seems to strive to ensure that the rights of stakeholders are not infringed upon.

- This company seems to disclose matters that have a significant impact on decision-making.

- Brand Value

- I feel favorable toward this company’s brand.

- I have a good impression of this company’s brand.

- I would choose this company’s brand first.

- This company’s brand has distinctive characteristics.

- This company’s brand is well-known.

- Perceived Quality

- I think this company’s products are of good quality.

- I think this company’s products have excellent durability.

- I think this company’s products are convenient to use.

- I think this company’s products have good functionality.

- I think this company’s products have excellent performance.

- Trust (Ability)

- This company seems to have the ability to supply the products customers need.

- This company seems to have knowledge about the products customers need.

- This company seems to have experience in supplying the products customers need.

- This company seems to have the expertise to produce the products customers need.

- This company seems to have the technological capability to produce the products customers need.

- Trust (Benevolence)

- I believe this company is concerned with the customers’ point of view.

- I believe this company is positive about accommodating customer requests.

- I believe this company responds favorably to customer requests.

- I believe this company has a customer-centric management policy.

- This company will likely manage its business with customer value in mind.

- Trust (Integrity)

- This company will likely fulfill its promises to customers.

- The promises this company makes to customers are trustworthy.

- This company will likely not make false statements to customers.

- The information this company provides to customers will likely be honest.

- The service this company provides to customers will likely be honest.

- Purchase Intention

- I would choose this company’s products first.

- I will continuously purchase this company’s products.

- I am willing to recommend this company’s products to others.

- I will speak favorably about this company’s products to others.

- I would positively consider repurchasing this company’s products.

References

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Manag. Sci. 2014, 60, 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Farooq, U.; Alam, M.M.; Dai, J. How does environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance determine investment mix? New empirical evidence from BRICS. Borsa Istanb. Rev. 2024, 24, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.S.; Lin, S.T.; Chuang, C.J. ESG Strategies and Sustainable Performance in Multinational Enterprises. Sustainability 2025, 17, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, P.; Apaolaza-Ibáñez, V. Consumer attitude and purchase intention toward green energy brands: The roles of psychological benefits and environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do Consumers Expect Companies to be Socially Responsible? The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Buying Behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnsack, R.; Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J.; Bidmon, C.M. Driving the electric bandwagon: The dynamics of incumbents’ sustainable innovation. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 727–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; van Tulder, R. International business, corporate social responsibility and sustainable development. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, L.; Anh, L.; Duc, V. Valuing ESG: How financial markets respond to corporate sustainability. Int. Bus. Rev. 2025, 34, 102418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.B.; Verma, R.; Sharma, D.; Moghalles, S.A.; Hasan, S.A.S. The impact of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices on customer behavior towards the brand in light of digital transformation: Perceptions of university students. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2371063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, G.; Abril, C. Exploring the relationship between sustainability perceptions and brand value: How and why does perceived sustainability affect brand value? Span. J. Mark. ESIC 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Rhee, T. How Does Corporate ESG Management Affect Consumers’ Brand Choice? Sustainability 2023, 15, 6795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourin Inc. South Korea’s Automobile Sales Results in 2023. AAA Weekly—Asian Automotive Analysis. 2023. Available online: https://aaa.fourin.com/reports/d08dfbc0-f0af-11ee-8a09-190555bc3842/south-koreas-automobile-sales-results-in-2023 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Waites, S.F. Decoding ESG: Consumer Perceptions, Ethical Signals and Financial Outcomes. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2025, 18, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.K.S. Building Brands for a Sustainable Future: Integrating Strategy, Consumer Response and Ethical Communication [SSRN Scholarly Paper]. SSRN. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=5261202 (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. In Uncertainty in Economics; Diamond, P., Rothschild, M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling Theory: A Review and Assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An Integrative Model Of Organizational Trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means-End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Attitudes and the Attitude-Behavior Relation: Reasoned and Automatic Processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Barbosa, A.; da Silva, M.C.B.C.; da Silva, L.B.; Morioka, S.N.; de Souza, V.F. Integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria: Their impacts on corporate sustainability performance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C. Investigating the intersection of ESG investing, green recovery, and SME development in the OECD. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. Corporations and climate change: An overview. WIREs Clim. Change 2024, 15, e919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylżanowski, R.; Kazojć, K.; Miciuła, I. Exploring the Link between Energy Efficiency and the Environmental Dimension of Corporate Social Responsibility: A Case Study of International Companies in Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 6080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J.; Filis, G.; Mitrokostas, E. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Econ. Model. 2016, 52, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. Regulations and Enhanced Standards for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Automobiles; Ministry of Environment (MOE): Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Awa, H.O.; Etim, W.; Ogbonda, E. Stakeholders, stakeholder theory and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfajfar, G.; Shoham, A.; Małecka, A.; Zalaznik, M. Value of corporate social responsibility for multiple stakeholders and social impact—Relationship marketing perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 143, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cabarcos, M.Á.; Ziane, Y.; López-Pérez, M.L.; Piñeiro-Chousa, J. The Ethical Commitment of Business Strategy: ESG-Related Factors as Drivers of the SDGs. J. Bus. Ethics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-business-conduct_15f5f4b3-en.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Zhu, N.; Aryee, E.N.T.; Agyemang, A.O.; Wiredu, I.; Zakari, A.; Agbadzidah, S.Y. Addressing environment, social and governance (ESG) investment in China: Does board composition and financing decision matter? Heliyon 2024, 10, e30783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Van Luu, B.; Chen, C.H. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2020, 52, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J.; Olson, J.C.; Haddock, R.A. Price, brand name, and product composition characteristics as determinants of perceived quality. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand Credibility, Brand Consideration, and Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.-K.; Burnasheva, R.; Suh, Y.G. Perceived ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) and Consumers’ Responses: The Mediating Role of Brand Credibility, Brand Image, and Perceived Quality. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Cai, X. The impact of environmental, social and governance performance on brand value: The role of the digitalisation level. S. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2024, 55, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L.; Krishen, A. Signaling green! firm ESG signals in an interconnected environment that promote brand valuation. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; Simon Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J.; Chestnut, R.W. Brand Loyalty: Measurement and Management; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, T.A. The effects of corporate brand attributes on attitudinal and behavioural consumer loyalty. J. Consum. Mark. 2007, 24, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, A.; Meisterknecht, J.P.S.; Angreani, L.S.; Wicaksono, H. Advancing sustainability in the automotive sector: A critical analysis of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance indicators. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2025, 16, 100248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolek, M.; Zengin, B. ESG: The new currency of brand value. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. 2025, 2025, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Esponda-Perez, J.A.; Millones-Liza, D.Y.; Villar-Guevara, M.; Haro-Zea, K.L.; Gallardo-Canales, R. The impact of perceived value on brand image and loyalty: A study of healthy food brands in emerging markets. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1482009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.; Stylidis, K.; Söderberg, R. Cognitive Quality: An Unexplored Perceived Quality Dimension in the Automotive Industry. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Johnson, M.D.; Anderson, E.W.; Cha, J.; Bryant, B.E. The American Customer Satisfaction Index: Nature, Purpose, and Findings. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, R.T.; Oliver, R.L. (Eds.) Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Xie, X.; Huang, W.; Yu, Q. The Design of Automotive Interior for Chinese Young Consumers Based on Kansei Engineering and Eye-Tracking Technology. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovillo, G.; Rapuano, M.; Milite, A.; Ruggiero, G. Perceived Quality in the Automotive Industry: Do Car Exterior and Interior Color Combinations Have an Impact? Appl. Sci. 2024, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, P.; Joost, M.; Kuttler, T.; Lienkamp, M.; Awad, A. Enhanced socially oriented mission-based driving cycles generation and simulation framework for light electric vehicles. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ole, H.C.; Sakka, E.W.; Mandagi, D.W. Perceived Quality, Brand Trust, Image, and Loyalty as Key Drivers of Fast Food Brand Equity. Indones. J. Islam. Econ. Financ. 2025, 5, 99–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. What Trust Means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. Managing User Trust in B2C e-Services. E-Serv. J. 2003, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monfort, A.; López-Vázquez, B.; Sebastián-Morillas, A. Building trust in sustainable brands: Revisiting perceived value, satisfaction, customer service, and brand image. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2025, 4, 100105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecchi, M.; Plangger, K. Perceived brand transparency: A conceptualization and measurement scale. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 1109–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.-K.; Lee, S.-M.; Luan, B.-K. The Impact of ESG on Brand Trust and Word of Mouth in Food and Beverage Companies: Focusing on Jeju Island Tourists. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.W.; Lyon, T.P.; Barg, J. No End in Sight? A Greenwash Review and Research Agenda. Organ. Environ. 2024, 37, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, J.-C.; Cui, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, C. Perceived Greenwashing and Its Impact on the Green Image of Brands. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccarius, T.; Chen, C.-F. Examining trust as a critical factor for the adoption of electric vehicle sharing via necessary condition analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; MacInnis, D.J.; Pieters, R.; Chan, E.; Northey, G. Consumer Behaviour; Cengage AU: Southbank, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B. The effect of brand and price information on subjective product evaluations. Adv. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 87–90. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, M.; Burlig, F. Electric and gasoline vehicle total cost of ownership across US cities. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 565–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.; Bonetti, F.; Calma, A.; Martí-Parreño, J. The Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science at 50: A historical analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2023, 51, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V.G.; Steckel, J.H.; Gupta, A. When do purchase intentions predict sales? Int. J. Forecast. 2007, 23, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morwitz, V. Consumers’ Purchase Intentions and their Behavior. Found. Trends Mark. 2014, 7, 181–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, B.H.; Hartwick, J.; Warshaw, P.R. The Theory of Reasoned Action: A Meta-Analysis of Past Research with Recommendations for Modifications and Future Research. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Olsen, K.L.; Cudmore, B.A.; Hill, R.P. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafferty, B.A.; Goldsmith, R.E. Cause–brand alliances: Does the cause help the brand or does the brand help the cause? J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Xiong, L.; Peng, R. The mediating role of investor confidence on ESG performance and firm value: Evidence from Chinese listed firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 61, 104988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, R.; Ehrlich, G.; Fan, Y.; Ruzic, D.; Leard, B. Firms and Collective Reputation: A Study of the Volkswagen Emissions Scandal. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2023, 21, 484–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The Company and the Product: Corporate Associations and Consumer Product Responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Bijmolt, T.H.A.; Tribó, J.A.; Verhoef, P. Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2012, 29, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Pacheco, M. How Green Trust, Consumer Brand Engagement and Green Word-of-Mouth Mediate Purchasing Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N. Developing and validating a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A. A critical review and reconstruction of perceptual brand equity. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, M.I.; Pontes, N. What drives car buyers to accept a rejuvenated brand? the mediating effects of value and pricing in a consumer-brand relationship. J. Strateg. Mark. 2022, 32, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiville, J. Connecting the dots between brand equity and brand loyalty for retailers: The mediating roles of brand attitudes and word-of-mouth communication. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 177, 114650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.; Yin, X.; Xing, G. Impact of Perceived Product Value on Customer-Based Brand Equity: Marx’s Theory—Value-Based Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 931064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, G.; Fischer, A.R.H.; van Trijp, H.C.M. The price of sustainability: How consumers trade-off conventional packaging benefits against sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. Price fairness, satisfaction, and trust as antecedents of purchase intentions towards organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinado, J.R.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A.N.P. The Effect of Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction in an Automotive After-Sales Service. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Teoh, A.P. The Role of Trust in Predicting Behavioral Intention to Use Electric Car-sharing Services: Evidence from China. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–10 December 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1195–1199. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Whence Consumer Loyalty? J. Mark. 1999, 63 (Suppl. 1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Luis Munuera-Alemán, J. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 2001, 35, 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassar, W.; Mittal, B.; Sharma, A. Measuring customer-based brand equity. J. Consum. Mark. 1995, 12, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of Price, Brand, and Store Information on Buyers’ Product Evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulding, W.; Kalra, A.; Staelin, R.; Zeithaml, V.A. A Dynamic Process Model of Service Quality: From Expectations to Behavioral Intentions. J. Mark. Res. 1993, 30, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Jain, V.; Eastman, J.K.; Ambika, A. The components of perceived quality and their influence on online re-purchase intention. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 42, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and Validating Trust Measures for e-Commerce: An Integrative Typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajli, N. Social commerce constructs and consumer’s intention to buy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Ghuman, K. The value proposition of food delivery apps from the perspective of theory of consumption value. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albitar, K.; Hussainey, K.; Kolade, N.; Gerged, A.M. ESG disclosure and firm performance before and after IR: The moderating role of governance mechanisms. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2020, 28, 429–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-n.; Han, S.-L. The Effect of ESG Activities on Corporate Image, Perceived Price Fairness, and Consumer Responses. Korean Manag. Rev. 2021, 50, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Kwon, E.; Hong, S.; Shoenberger, H.; Stafford, M.R. Mollifying green skepticism: Effective strategies for inspiring green participation in the hospitality industry. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1176863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.-H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H. Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup Analysis in Partial Least Squares (PLS) Path Modeling: Alternative Methods and Empirical Results. In Measurement and Research Methods in International Marketing; Sarstedt, M., Schwaiger, M., Taylor, C.R., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2011; Volume 22, pp. 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, N.N.; Phuong, N.N.; Tran, T.V.; Thang, L.D. The effect of country-of-origin image on purchase intention: The mediating role of brand image and brand evaluation. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| H1-1 | Environmental management in ESG will have a positive effect on brand value. |

| H1-2 | Social responsibility activities in ESG will have a positive effect on brand value. |

| H1-3 | Transparent and ethical governance in ESG will have a positive effect on brand value. |

| H2-1 | Environmental management in ESG will have a positive effect on perceived quality. |

| H2-2 | Social responsibility activities in ESG will have a positive effect on perceived quality. |

| H2-3 | Transparent and ethical governance in ESG will have a positive effect on perceived quality. |

| H3-1 | Environmental management in ESG will have a positive effect on trust. |

| H3-2 | Social responsibility activities in ESG will have a positive effect on trust. |

| H3-3 | Transparent and ethical governance in ESG will have a positive effect on trust. |

| H4 | Perceived quality will have a positive effect on brand value. |

| H5 | Perceived quality will have a positive effect on corporate trust. |

| H6 | Brand value will have a positive effect on consumers’ purchase intention. |

| H7 | Perceived quality will have a positive effect on consumers’ purchase intention. |

| H8 | Trust will have a positive effect on consumers’ purchase intention. |

| Variable | Operational Definition | Relevant Studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV | Environment (Eco-friendly Management) | Managerial activities that consider environmental sustainability in the production and use of products and services. | Albitar et al. [101] Park, Y., & Han, S. [102] | |

| Social (Social Responsibility) | Efforts to protect workers’ rights and foster capacity development, pursue shared growth with partner companies, protect consumer rights, and carry out social contribution activities for the local community and the underprivileged. | |||

| Governance (Transparency) | Establishing governance that protects shareholders’ rights, includes a board of directors with proper management and supervisory functions, and involves appointing external auditors with expertise and independence, ensuring transparent disclosure of corporate management information. | |||

| MV | Brand Value | The comprehensive value of a brand reflected in awareness, favorability, and loyalty. | Keller [45] Chaundhuri & Holbrook [23] | |

| Perceived Quality | Customer evaluation of the excellence of a product. | Zeithaml [22] | ||

| Trust | Ability | The belief that a company has the skills or capabilities necessary to meet customer needs. | Gefen & Straub [59] Mayer et al. [20] | |

| Benevolence | The belief that the company prioritizes customers with goodwill. | |||

| Integrity | The belief that the company adheres to principles and norms and behaves ethically and morally. | |||

| DV | Purchase Intention | The psychological process reflecting the intention to purchase a product or service. | Fishbein & Ajzen [45] | |

| Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 99 | 31.4% |

| Male | 216 | 68.6% | |

| Age | 20s | 48 | 15.2% |

| 30s | 98 | 31.1% | |

| 40s | 99 | 31.4% | |

| 50 and above | 70 | 22.2% | |

| Position | Staff | 37 | 11.7% |

| Assistant Manager/Manager | 171 | 54.3% | |

| Deputy General Manager/Team Leader | 94 | 29.8% | |

| Executive | 12 | 3.8% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Education | Bachelor’s Degree | 276 | 87.6% |

| Graduate School (Enrolled) | 5 | 1.6% | |

| Graduate School (Graduated) | 34 | 10.8% | |

| Level of ESG Knowledge | Somewhat Knowledgeable | 161 | 51.1% |

| Knowledgeable | 121 | 38.4% | |

| Very Knowledgeable | 33 | 10.5% | |

| Owned Vehicle | Hyundai | 177 | 56.2% |

| Kia | 57 | 18.1% | |

| Mercedes-Benz | 23 | 7.3% | |

| BMW | 18 | 5.7% | |

| Toyota (Lexus) | 6 | 1.9% | |

| Ford | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Volvo | 9 | 2.9% | |

| Renault | 11 | 3.5% | |

| Chevrolet | 8 | 2.5% | |

| Other | 5 | 1.6% | |

| Factor | Measurement | Loading | Error | t-Value | CR | AVE | Cronbach α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second | First | |||||||

| Trust | Ability (TAIP) | ABT5 | 0.760 | 0.821 | 0.534 | 0.827 | ||

| ABT4 | 0.754 | 0.080 | 12.712 | |||||

| ABT3 | 0.725 | 0.075 | 12.221 | |||||

| ABT2 | 0.715 | 0.074 | 12.063 | |||||

| Benevolence (TBIP) | BEN4 | 0.760 | 0.838 | 0.564 | 0.849 | |||

| BEN3 | 0.754 | 0.063 | 14.318 | |||||

| BEN2 | 0.725 | 0.060 | 14.317 | |||||

| BEN1 | 0.715 | 0.054 | 14.740 | |||||

| Integrity (TIIP) | INT5 | 0.760 | 0.833 | 0.556 | 0.861 | |||

| INT4 | 0.754 | 0.061 | 15.320 | |||||

| INT3 | 0.725 | 0.065 | 14.755 | |||||

| INT1 | 0.715 | 0.052 | 15.161 | |||||

| Latent Variable | Cronbach’s α | CR (rho_a) | CR (rho_c) | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.70 | >0.70 | >0.70 | >0.50 | |

| Eco-Friendly Management | 0.786 | 0.786 | 0.875 | 0.701 |

| Social Responsibility | 0.764 | 0.768 | 0.864 | 0.679 |

| Governance | 0.772 | 0.776 | 0.868 | 0.686 |

| Brand Value | 0.865 | 0.866 | 0.908 | 0.711 |

| Perceived Quality | 0.844 | 0.845 | 0.906 | 0.762 |

| Trust | 0.862 | 0.869 | 0.916 | 0.785 |

| Purchase Intention | 0.819 | 0.819 | 0.892 | 0.734 |

| Variable | Indicator | Outer Loading | AVE | Variable | Indicator | Outer Loading | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >0.70 | >0.50 | >0.70 | >0.50 | ||||

| Environmental Management | ENV1 | 0.833 | 0.701 | Perceived Quality | QUA1 | 0.878 | 0.762 |

| ENV2 | 0.852 | QUA2 | 0.858 | ||||

| ENV5 | 0.826 | QUA5 | 0.882 | ||||

| Social Responsibility | SOC4 | 0.802 | 0.679 | Trust | TAIP | 0.829 | 0.785 |

| SOC5 | 0.815 | TBIP | 0.919 | ||||

| SOC6 | 0.855 | TIIP | 0.906 | ||||

| Governance | GOV1 | 0.824 | 0.686 | Purchase Intention | PUR2 | 0.860 | 0.734 |

| GOV2 | 0.826 | PUR3 | 0.859 | ||||

| GOV5 | 0.835 | PUR4 | 0.852 | ||||

| Brand Value | BRA1 | 0.853 | 0.711 | ||||

| BRA2 | 0.821 | ||||||

| BRA3 | 0.849 | ||||||

| BRA4 | 0.851 | ||||||

| Purchase Intention | Brand Value | Social Responsibility | Trust | Perceived Quality | Governance | Environmental Management | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase Intention | 0.857 | ||||||

| Brand Value | 0.767 | 0.843 | |||||

| Social Responsibility | 0.654 | 0.688 | 0.824 | ||||

| Trust | 0.809 | 0.774 | 0.728 | 0.886 | |||

| Perceived Quality | 0.682 | 0.789 | 0.612 | 0.764 | 0.873 | ||

| Governance | 0.619 | 0.663 | 0.692 | 0.701 | 0.592 | 0.829 | |

| Environmental Management | 0.572 | 0.630 | 0.673 | 0.611 | 0.559 | 0.649 | 0.837 |

| Category | Variable | R2 | Criterion | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Explanatory Power Evaluation | Purchase Intention | 0.704 | R2 < 0.25: Weak 0.25 ≦ R2 < 0.75: Moderate 0.75 ≦ R2: Strong | Adequate |

| Brand Value | 0.712 | Adequate | ||

| Trust | 0.719 | Adequate | ||

| Perceived Quality | 0.445 | Adequate | ||

| Model Goodness-of-Fit Evaluation | Indicator | Value | Evaluation Criteria | |

| SRMR | 0.054 | <0.080 | Adequate | |

| d_ULS | 0.728 | >0.050 | Adequate | |

| d_G | 0.466 | >0.050 | Adequate | |

| NFI | 0.817 | >0.800 | Adequate |

| Variable | R2 | VIF | Kock (>3.3) | Hair (>5.0) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust | 0.785 | 4.658 | TRUE | FALSE |

| Brand_Value | 0.750 | 3.993 | TRUE | FALSE |

| Purchase_Intention | 0.706 | 3.406 | TRUE | FALSE |

| Perceived_Quality | 0.679 | 3.111 | FALSE | FALSE |

| Social_Management | 0.645 | 2.813 | FALSE | FALSE |

| Governance_Management | 0.596 | 2.474 | FALSE | FALSE |

| Environmental_Management | 0.542 | 2.181 | FALSE | FALSE |

| Hypothesis Path | Path Coefficient | t-Value | p-Value | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | H1-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Brand Value | 0.114 | 2.431 | 0.015 * | Supported |

| H1-2 | Social Responsibility → Brand Value | 0.190 | 3.555 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H1-3 | Governance → Brand Value | 0.149 | 3.152 | 0.002 ** | Supported | |

| H2 | H2-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Perceived Quality | 0.182 | 2.738 | 0.006 ** | Supported |

| H2-2 | Social Responsibility → Perceived Quality | 0.310 | 4.766 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H2-3 | Governance → Perceived Quality | 0.259 | 3.798 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H3 | H3-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Trust | 0.026 | 0.555 | 0.579 | Rejected |

| H3-2 | Social Responsibility → Trust | 0.283 | 5.248 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H3-3 | Governance → Trust | 0.227 | 4.016 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H4 | Perceived Quality → Brand Value | 0.521 | 10.833 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H5 | Perceived Quality → Trust | 0.442 | 7.500 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H6 | Brand Value → Purchase Intention | 0.360 | 3.835 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| H7 | Perceived Quality → Purchase Intention | −0.018 | 0.236 | 0.814 | Rejected | |

| H8 | Corporate Trust → Purchase Intention | 0.545 | 5.283 | 0.000 *** | Supported | |

| Variables | Correlation Value | Permutation | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-Friendly Management | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.731 | Not Supported |

| Social Responsibility | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.525 | Not Supported |

| Governance | 0.998 | 0.999 | 0.160 | Not Supported |

| Brand Value | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.266 | Not Supported |

| Perceived Quality | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.915 | Not Supported |

| Trust | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.467 | Not Supported |

| Purchase Intention | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.717 | Not Supported |

| Hypothesis | Hypothesis Path | Group 1 Path Coefficient | Group 2 Path Coefficient | Difference | p-Value | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Brand Value | 0.099 | 0.097 | 0.002 | 0.985 | Not Supported |

| H1-2 | Social Responsibility → Brand Value | 0.154 | 0.331 | −0.177 | 0.271 | Not Supported |

| H1-3 | Governance → Brand Value | 0.078 | −0.114 | 0.192 | 0.081 | Not Supported |

| H2-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Perceived Quality | 0.189 | 0.214 | −0.025 | 0.838 | Not Supported |

| H2-2 | Social Responsibility → Perceived Quality | 0.317 | 0.315 | 0.001 | 0.994 | Not Supported |

| H2-3 | Governance → Perceived Quality | 0.285 | 0.252 | 0.033 | 0.799 | Not Supported |

| H3-1 | Eco-Friendly Management → Trust | 0.227 | 0.02 | 0.207 | 0.061 | Not Supported |

| H3-2 | Social Responsibility → Trust | 0.313 | 0.109 | 0.205 | 0.206 | Not Supported |

| H3-3 | Governance → Trust | 0.161 | 0.38 | −0.219 | 0.101 | Not Supported |

| H4 | Perceived Quality → Brand Value | 0.317 | 0.507 | −0.19 | 0.417 | Not Supported |

| H5 | Perceived Quality → Trust | 0.473 | 0.603 | −0.13 | 0.255 | Not Supported |

| H6 | Brand Value → Purchase Intention | 0.464 | 0.438 | 0.026 | 0.852 | Not Supported |

| H7 | Perceived Quality → Purchase Intention | 0.117 | −0.29 | 0.407 | 0.013 * | Supported |

| H8 | Corporate Trust → Purchase Intention | 0.481 | 0.618 | −0.137 | 0.665 | Not Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Im, E.; Gim, G. The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198733

Kim J, Im E, Gim G. The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198733

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jangwoo, Euntack Im, and Gwangyong Gim. 2025. "The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198733

APA StyleKim, J., Im, E., & Gim, G. (2025). The Impact of ESG Management by Automobile Companies on Consumer Purchase Intention. Sustainability, 17(19), 8733. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198733